#judaic new year

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

trying to put all my jewish feelings into something sweet

1 month until Rosh Hashanah, one of my favorite holidays

#the jewish experience tag#jews being jews#linocut#block printing#relief print#art#rosh hashanah#judaic new year

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yk the more I read about the cultural roots of the New Age, the more I associate it with the Greco-Egyptian-Judaic milieu of the early roman period. Solid 200 years of people just trying new shit and seeing what happens. Modern communication technology is our very own Mediterranean exchange.

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Torah scroll that survived desecration by British troops during the American Revolution is now on display at the New-York Historical Society, part of an exhibit connected to the society’s three-year, $65 million reopening.

The scroll from the Shearith Israel synagogue, the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States and New York’s only Judaic house of worship for nearly a century, still has burn marks on it from the British ransacking of the city in 1776.

In August of that year, shortly after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, George Washington and his troops retreated to Manhattan Island after being routed by the British on Long Island.

Washington wanted desperately to hold onto whatever small scrap of New York he could, but by November his army had been booted from Manhattan. The British would occupy the area for the remainder of the war, according to The Jewish Week.

During the occupation, thousands of rebel sympathizers fled the city as British troops looted and pillaged, setting fire to homes, bridges and even Congregation Shearith Israel, which was built in 1729.

The synagogue had bought two Torah scrolls when it was built, one Sephardic and one Ashkenazi, since the community was split.

And during the Revolution, the British attacked both scrolls, though it is the Ashkenazi one that is now on display, according to The Jewish Week.

“They set one on fire, and they slashed the other with a sword,” said Rabbi Hayyim Angel, the current rabbi at Temple Shearith Israel.

Jewish law requires that desecrated holy texts be buried, but Angel and other scholars speculate that the community realized the historic value of the damaged scrolls and kept them instead, according to the publication.

It’s not clear where the scrolls were kept during the seven years of the British occupation. Most of the Shearith Israel congregants fled the city, since they were rebel sympathizers and some believe they may have taken the scrolls with them.

Another possibility is that the British forces protected them. The British employed Hessian soldiers, troops hired out by German rulers to the British to help fight the war, and at least one of them in the city was Jewish, said Debra Schmidt Bach, a curator at the society.

Whatever the case, the attack on the scrolls was probably not an anti-Semitic attack, according to Bach.

“It was part and parcel of the vandalism that was going on throughout the city,” she said.

Moreover, British commanders harshly punished the two British soldiers who attacked the synagogue. “One was lashed so severely he died from his wounds,” Bach added.

Other items on display during the exhibition include features Sabbath candle holders and a Chanukah menorah by famed Colonial silversmith Myer Myers; two portraits of Jews who fought in the War of 1812; and a book of poems by Emma Lazarus, a congregation member whose poem, “The New Colossus,” adorns the Statue of Liberty.

The exhibition opened Nov. 11 at the New-York Historical Society, and will be on view for about four months. The museum is located at 170 Central Park West.

(Above: The Shearith Israel Torah scroll that was burned by British troops in 1776. Photo by The Jewish Week.)

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

"My father was born in 1905 in Bethlehem as an Ottoman citizen with Ottoman identification papers. As a teenager he witnessed the Ottomans being replaced by the British, and suddenly, almost overnight, he became a citizen of Mandate Palestine with a Palestinian passport issued by the British Mandate government. In 1949, when Bethlehem became part of Jordan, he became suddenly a citizen of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. And when he died in 1975, he died under Israeli occupation with an ID card issued by Israel. But he was the same person throughout those geo-political vicissitudes and had no choice but to adjust to changing political and imperial realities.

Throughout Palestinian history empires have occupied the land for a certain number of years but were then forced to leave. Most of the time an empire departed only to make space for another empire. The majority of the native people of the land seldom left. Throughout history and starting with the Assyrian Exile, only a small minority was deported, and only a small percentage decided to leave. The vast majority of the native people remained in the land of their forefathers (2 Kgs 25:11). They remained the Am Haaretz, the native 'People of the Land,' in spite of the diverse empires controlling that land. This is why in this book I choose the people of the land as the description for the native inhabitants throughout history, for it is they who are the enduring continuum.

Their identity, however, was forced to change and develop according to the new realities and empires in which they found themselves. They changed their language from Aramaic to Greek to Arabic, while their identity shifted from Canaanite, to Hittite, to Hivite, to Perizzite, to Girgashite, to Amorite, to Jebusite, to Philistine, Israelite, Judaic/Samaritan, to Hasmonaic, to Jewish, to Byzantine, to Arab, to Ottoman, and to Palestinian, to mention some. The name of the country also changed from Canaan to Philistia, to Israel, to Samaria and Juda, to Palestine. ... And yet they stayed, throughout the centuries, and remained the people of the land with a dynamic identity. In this sense Palestinians today stand in historic continuity with biblical Israel. The native people of the land are the Palestinians. The Palestinian people (Muslims, Christians, and Palestinian Jews) are a critical and dynamic continuum from Canaan to biblical times, from Greek, Roman, Arab, and Turkish eras up to the present day. They are the native peoples, who survived those empires and occupations, and they are also the remnant of those invading armies and settlers who decided to remain in the land to integrate rather than to return to their original homelands. The Palestinians are the accumulated outcome of this incredible dynamic history and these massive geo-political developments."

Mitri Raheb, Faith in the Face of Empire: The Bible Through Palestinian Eyes (2012)

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

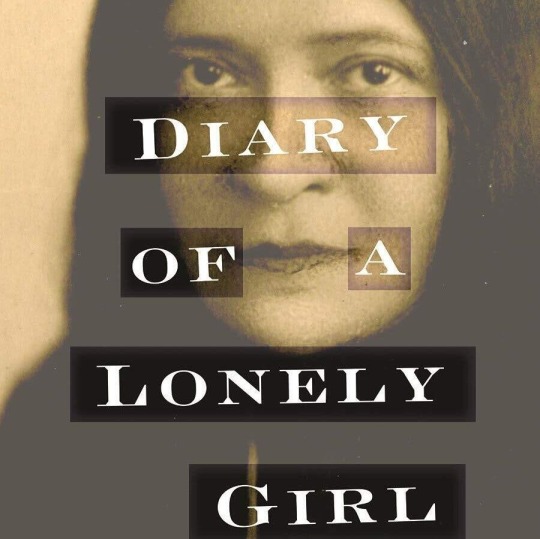

Works written decades ago, often by female Jewish immigrants, were dismissed as insignificant or unmarketable. But in the past several years, translators devoted to the literature are making it available to a wider readership. -

By Joseph Berger

Feb. 6, 2022

In “Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love,” a sendup of the socialists, anarchists and intellectuals who populated New York’s Lower East Side in the early 20th century, Miriam Karpilove writes from the perspective of a sardonic young woman frustrated by the men’s advocacy of unrestrained sexuality and their lack of concern about the consequences for her.

When one young radical tells the narrator that the role of a woman in his life is to “help me achieve happiness,” she observes in an aside to the reader: “I did not feel like helping him achieve happiness. I felt that I’d feel a lot better if he were on the other side of the door.”

In a review for Tablet magazine, Dara Horn compared the book to “Sex and the City,” “Friends” and “Pride and Prejudice.” Though it was published by Syracuse University Press in English in 2020, Karpilove, who immigrated to New York from Minsk in 1905, wrote it about a century ago, and it was published serially in a Yiddish newspaper starting in 1916.

Jessica Kirzane, an assistant instructional professor of Yiddish at the University of Chicago who translated the novel, said that her students are drawn to its contemporary echoes of men using their power for sexual advantage. “The students are often surprised that this is someone whose experiences are so relatable even though the writing was so long ago,” she said in an interview.

Yiddish novels written by women have remained largely unknown because they were never translated into English or never published as books. Unlike works translated from the language by such male writers as Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade, Yiddish fiction by women was long dismissed by publishers as insignificant or unmarketable to a wider audience.

But in the past several years, there has been a surge of translations of female writers by Yiddish scholars devoted to keeping the literature alive.

Madeleine Cohen, the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass., said that counting translations published or under contract, there will have been eight Yiddish titles by women — including novels and story collections — translated into English over seven years, more than the number of translations in the previous two decades.

Yiddish professors like Kirzane and Anita Norich, who translated “A Jewish Refugee in New York,” by Kadya Molodovsky, have discovered works by scrolling through microfilms of long-extinct Yiddish newspapers and periodicals that serialized the novels. They have combed through yellowed card catalogs at archives like the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, searching for the names of women known for their poetry and diaries to see if they also wrote novels.

“This literature has been hiding in plain sight, but we all assumed it wasn’t there,” said Norich, a professor emeritus of English and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. “Novels were written by men while women wrote poetry or memoirs and diaries but didn’t have access to the broad worldview that men did. If you’ve always heard that women didn’t write novels in Yiddish, why go looking for it?”

But look for it Norich did. It has been painstaking, often tedious work but exciting as well, allowing Norich to feel, she said, “like a combination of sleuth, explorer, archaeologist and obsessive.”

“A Jewish Refugee in New York,” serialized in a Yiddish newspaper in 1941, centers on a 20-year-old from Nazi-occupied Poland, who escapes to America to live with her aunt and cousins on the Lower East Side. Instead of offering sympathy, the relatives mock her clothing and English malapropisms, pay scant attention to her fears about her European relatives’ fate and try to sabotage her budding romances.

Until Norich’s translation was published by Indiana University Press in 2019, there had been only one book of Yiddish fiction by an American woman — Blume Lempel — translated into English, Norich said. (Two non-American writers had been translated: Esther Singer Kreitman, the sister of Isaac Bashevis Singer, who settled in Britain, and Chava Rosenfarb, a Canadian who translated herself.)

The new translations are stirring a smidgen of optimism among Yiddish scholars and experts for a language whose extinction has long been fretted over but has never come to pass. Yiddish is the lingua franca of many Hasidic communities, but their adherents rarely read secular works. And it has faded away in everyday conversation among the descendants of the hundreds of thousands of East European immigrants who brought the language to the United States in the late 19th century.

The new translations are being read by people interested in everyday life in East European shtetls and immigrant ghettos in the United States as told from a woman’s perspective. They are also being read by students at the nation’s two dozen campuses with Yiddish programs. “Students were often surprised by how unsentimental these female novelists are, how wide-ranging are their themes, and how frank they are about female desire,” Norich said.

With a grant from the Yiddish Book Center, a 42-year-old nonprofit that seeks to revitalize Yiddish literature and culture, Norich is now translating a second novel: “Two Feelings,” by Celia Dropkin (1887-1956), a Russian immigrant who was admired for her erotically charged poems but never known as a novelist.

“Two Feelings” had been serialized in The Yiddish Forward in 1934 and then forgotten. It tells the story of a married woman who struggles to reconcile her feelings for, as Norich put it, a “husband she loves because he is a good man, and a lover she loves because he is a good lover though not a good man.”

One recent volume, “Oedipus in Brooklyn,” is a collection of stories by Blume Lempel (1907-99), the daughter of a Ukrainian kosher butcher. After spending a decade in Paris, she, her husband and their two children immigrated to New York in 1939, where she began writing for Yiddish newspapers.

In an introduction, her translators, Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, describe Lempel as “drawn to subjects seldom explored by other Yiddish writers in her time: abortion, prostitution, women’s erotic imaginings, incest.” Her sentences, they add, “often evoke an unsettling blend of splendor and menace.”

In promotional copy for the book, Cynthia Ozick called it “a splendid surprise” and asked: “Why should Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade monopolize this rich literary lode?”

The recent books have mostly been published by academic presses in small runs, many of them financed by fellowships and stipends from the Yiddish Book Center. Despite the books’ contemporary themes, said Cohen, the center’s academic director, it has been an uphill battle to persuade mainstream trade publishers to acquire titles by women writers who are generally unknown and previously untranslated.

The scholars work independently, though they occasionally meet at conferences and panel discussions. Their life stories offer a window into the evolution of Yiddish.

Kirzane learned the language not in her childhood home but at the University of Virginia and in a doctoral program at Columbia University. Norich, the daughter of Yiddish-speaking Holocaust survivors from Poland, was born after the war in a displaced persons camp in Bavaria and was raised in the Bronx, continuing to speak Yiddish with her parents and brother.

When her daughter Sara was born, she made an effort to speak only Yiddish to her but gave up when Sara was 5. “You need a community to have a language grow,” she said.

These translators believe that the newly translated novels by women will enrich the teaching of Yiddish. Yiddish is, after all, called the mamaloshen — mother’s tongue — and a woman’s perspective, they said, has long been missing.

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine for a second, a group of Jews cooking a slightly different version of challah for Shabbat, matzah for Passover, and donuts for Hanukkah. A group of people whose ancestors were forced to convert to Catholicism against their will, yet continued to practice Jewish customs underground, even at the risk of being ostracized and tortured for doing so. Meet The Silent Jews.

Sometimes referred to as Crypto-Jews, anusim (Hebrew for coerced ones), or conversos, Silent Jews are descendants of Spanish Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492. Most left medieval Iberian territories for the Ottoman Empire or North Africa; others fled persecution and settled in new frontiers in the New World, where many found refuge.

I come from one of those persecuted families who came to South America around 1532 and discreetly practiced Jewish rituals, living in fear of being hunted down by the Inquisition. I only found out that my family was actually Jewish as a teenager, that all our colorful, fragrant, crunchy dishes were deeply rooted in Judaic culinary traditions from 16th-century Spain. That the ingredients and aromas of my mom’s kitchen resembled dishes from the Sephardic gastronomy repertoire.

When the pandemic struck, the combination of lockdown, curiosity, and melancholy led me to knead, mix, and eat plates from my mom’s Jewish inheritance passed on through several generations of women in our family. The kitchen was the right place to honor their sacrifices, bravery, and perseverance to maintain tradition, despite centuries of fear and persecution.

My locked-down days soon began to be filled with ingredients such as eggplants, spinach, leeks, and turnips, which mingled with the scents of cinnamon, anise, cardamom, and nutmeg, coming together with dried fruits and legumes.

Arroz con garbanzos (chickpea rice) was one of those dishes. With its characteristic aroma of bay leaf, caramelized onions, and raisins, it’s cooked with turmeric to give it its signature yellow color. As a kid, it was often mixed with a fried egg, with parsley sprinkled on top. In my search for Sephardic recipes, I became aware that this dish is very similar to pilaf with saffron, a Mediterranean spice my ancestors did not have access to since it didn’t grow in their new home.

Another delicious dish that also appears in the kitchens of Sephardic Jews from Turkey, Greece, and Morocco is estofado de berenjenas (eggplant stew). Made by sautéing eggplants in olive oil with garlic, onion, and cumin, this quick stew is served with smoked cheese or feta and an abundance of cilantro. My family pair it with homemade bread or corn arepas, an example of incorporating local ingredients.

On the most stressful days of the past year, comfort food became a necessity. A hearty dish of huevos con tomate (eggs with tomato) afforded me a sense of tranquility and a break from the chaos and uncertainty that surrounded me. This dish, which closely resembles shakshuka, was cooked at my house with ají dulce —the Caribbean’s colorful semi-spicy pepper— chili flakes, and smoked paprika. It’s so piquant and fragrant, I usually pair it with plain white rice or bread. However, my mother served it as a second course to complement her traditional pescado mermao, a hake fish stew cooked over a slow fire in an iron skillet with a mixture of garlic, peas, and eggplant, smothered in a sauce of chilies and tomatoes. The last touch included a bunch of fresh cilantro leaves and a hint of sour lime juice. It filled our entire house with a thick, citrusy aroma.

And the desserts! Buñuelos, small balls of fried dough with a sweet or salty filling; mine are usually made with raw cane sugar syrup, cloves, and nutmeg. There was always cake — plantain cake with cinnamon and smoked cheese, or traditional bizcochuelo, a sponge cake that was ever-present in my school lunchbox. Similar to pan d’Espana, which Sephardim took with them to the Diaspora, my mother put her own spin on this soft, light cake, using cornmeal instead of ground almonds, substituting orange blossom water with a few drops of rum, and swapping grated orange peel for the peel of a lemon, instead.

Reconnecting with my roots through food during these difficult times has helped me to cope with stress, anxiety, and loneliness. There’s still so much to cook, eat, and share; I’ll continue paying homage to each and every one of the dishes that my family preserved with such dedication and courage. This is the only way I can celebrate — and always carry with me — their everlasting legacy.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is this New Moon & Eclipse so powerful??

The Moon & Sun conjunction in Libra happened in conjunction with both the South Node and Black Moon Lilith. Additionally, it is the last eclipse that will happen in the sign of Libra for another 10 years.

(See my previous post for more detail on the Libra energy of this New Moon)

Black Moon Lilith

The Eclipse happens with both sun and moon in conjunction with Black Moon Lilith.

The Moon is in the part of it's orbit that has it farthest from the earth - a "Micro Moon" that would appear smaller if we could see it, and it moves slower when it is close to BML. This is a Shadow Work point of the chart, relating to the part of the moon's orbit when it is smaller, distant, less bright. Rejected, Cast out of the Garden, or ostracized.

In Hebrew-Judaic lore, Lilith was created equal to Adam - a man and woman created together as equal partners. Lilith knew her personal power, but Adam wanted Lilith to be subservient to him. He did not see her as his equal - but as lesser than him. His desire for power blinded him to the power of having an equal partner, and Lilith experienced deep rejection. The denial of equality.

How painful this must have been for her - to be told that the very essence of what she was - was somehow "less than" her partner's. Lilith argued, stood up for herself, demanding equality - and she was kicked out of the garden. Rejected, ostracized, demonized.

When have you had your own Lilith experiences? How many times have you experienced rejection, or been ostracized? Have you ever been painted as a villain after standing your ground? Have you been kicked out of certain circles or groups simply because of being your true authentic self?

How did you respond to those situations? How did you deal with the emotions that those situations brought up in you - the shame, the rage, the pain, the spitefulness? Would you respond differently now?

Lilith was demonized for centuries, but within the last few decades, she has been seen as a liberator. Her story gives so many people hope - and empowerment to fight against oppression.

Her story shows us that sometimes rage and anger are justified, and that it is within our right to stand up for ourselves and ask for equality. It is powerful to know your worth, and worthwhile to ask others to see your worth as well. In the end - you could say that Lilith being kicked out of the garden was the best thing to happen to her.... why would she want to stay with Adam and be a "lesser partner" when she could go out, forge her own path, and eventually be known as a GODDESS?

This Eclipse is the ideal time to connect with Lilith in your own way. See her story reflected in your own life. Acknowledge the pain of rejection that you have experienced, let yourself FEEL all the feelings that come with it.

Decide which of those feelings can be released, and which ones can be used to fuel your forward motion in positive ways with the new moon. Pull the weeds of the feelings that block you from growth, and take the feelings that can empower you and turn them into seeds to plant with the New Moon. You know your power and worth.... let the story of Lilith remind you that rejection often has less to do with YOU and more to do with the other person's insecurities. And that if you must leave a person or group behind - you can forge your own path and will find others who resonate with your power and choose to uplift you rather than oppress you.

Acknowledge the pain or anger within yourself - resist the urge to label it as negative or bad. Feelings are just feelings. It is what we do with them that can create positive or negative results.

#black moon lilith#equality#eclipse#astrology#astrologyupdate#astrologyalert#astrologer#astrology blog#astro blog#astrology transits#meditate#libra#libra season#witchblr#wicca#witchcraft community#witchcraft#witchy#feminism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Throughout the long scrapbook of humanity’s past, there is well documented evidence of Abrahamic Angels (Islamic, Judaic, Christian) coming down to earth and mingling with us.

This goes back as far as when we started to emerge, with new evidence now showing cave paintings that depict these bewinged and fanciful creatures. However, their notoriety peaked in the middle ages, when their accidental power, over both state and peasant, was absolute.

It was at that point, that these simple messengers transcended to true holiness.

That fact crossed my mind as I saw a 2005 Porsche Carrera GT ram an angel that had been crossing the street, and it stayed comfortably in the doorway as the creature readily spilled onto the asphalt, its wings barely even twitching, as if it had been expecting this and braced.

I watched from my window as the driver and passenger exited the car, and both are limp at the joints with disinterest.

Royally blue ichor sinks into the pavement as they hover there, it digging in like desperate fingertips, useless against the ungiving stone.

“I am here,” it says.

The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife will send someone to clean it up an hour after the inevitable call, and they will use a power hose to wash away the blood, and bag the body of the angel, now thoroughly mangled.

I’ve been seeing less and less of them each year, but maybe I’m just unlucky.

Less are dying on my road though, less are eating my trash, less are coming to try to tear down my bird feeders, to sneak into my chicken pen, to eat the eggs hidden there, brimming with honied yolk.

I live on the edge of suburbia, where I know they are most common, and they are becoming almost elusive.

I live in fear that He is sending less.

When I was in first grade, an angel came to see my rabbi in the middle of our Shabbat services.

It was glowing, and though it was not brighter than headlights, it was impossible to ignore its entrance.

Its body slowly reaching forward from the back, lead by the head into the posture of a sprawling lion, with its face and mane having been substituted for light. And after coming to the bimah at the front of the room, it climbed the two steps not even the rowdiest children dared to, heeling like a dog, before its mouth fell open, its tongue readily rolling out, long and yellowed as it was, and something was written on it, but in Hebrew I still can’t read.

Even I watched as our rabbi bent his head to do so for us, his lips barely twitching as he silently tasted and swallowed each word.

When he was done, he simply turned away and continued our services, and everyone pretended not to watch as the angel left, walking close enough by me to almost touch.

We moved away the year after, and now I live faraway on an edge of suburbia, and I used to see angels all the time.

I don’t known my neighbors, I haven’t for eight years yet, but if any of them care, they do nothing.

I’m getting increasingly worried He is sending less each year.

I’m getting increasingly worried that maybe I should do something.

I’m getting increasingly worried that one day He will send one for me, and while it is eating out of my trashcan down by the road, I will back up at full speed in my 2013 Subaru Forester and hit it,

killing it instantly.

#poetry#poems on tumblr#poem#original poem#I wrote this in 2022. Cleaned up the formatting a bit but eh#Itd not my best work but whatevs#Mack.poems

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julius Lester (January 27, 1939 - January 18, 2018) was born in St. Louis, the son of a Methodist minister. He spent much of his childhood in Missouri. He graduated from Fisk University with a BA in English.

He became active in the Civil Rights movement, going to Mississippi in 1964 as part of the movement called the Mississippi Summer Project.

He began working full-time for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as head of its photography department in Atlanta.

His writing career began in 1967 when a publisher read his essay “The Angry Children of Malcolm X,” and offered him a contract to develop it into a book. The book, titled Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gonna’ Get Your Mama, would be the first book to explain the term Black power and place it in the context of African American history.

He has published more than forty books, including non-fiction, children’s books, poetry, and novels. Among the awards these books have received are the Newbery Honor Medal, the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award, the National Book Award Finalist, the Boston Globe/Horn Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Honor Book, and the New York Times Outstanding Book. His books have been translated into eight languages.

He joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst as a professor of African American Studies. He joined the Judaic and Near Eastern Studies Department and taught courses there and in the English and History departments until his retirement (2004). He became the only faculty member to be awarded all three of the University’s most prestigious faculty awards: The Distinguished Teacher’s Award, the Faculty Fellowship Award for Distinguished Research and Scholarship, and the Chancellor’s Medal, the University’s highest honor. The Council for Advancement and Support of Education selected him as the Massachusetts State Professor of the Year.

He served as lay religious leader of Beth El Synagogue in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion: I was the most senior Islamic leader to visit Auschwitz. Here’s what I know about peace

Sheikh Mohammed Al-Issa

Ours was the most senior Islamic delegation to visit the site during its sorrowful history.

Passing through the infamous gates was a visceral, emotionally-arresting experience that managed to both transport me back in time and sharpen my mind on the future. For it was here that 1.1 million people, the vast majority of them Jews, were murdered during the Holocaust. And it was here that I reaffirmed my commitment to fight intolerance and hate in all its forms.

This visit was our moral obligation and an overdue sign of solidarity with our Jewish brothers and sisters, with whom we must tackle the many injustices and enmities there are in the world.

Indeed, all the world’s major faiths — Christian, Judaic, Hindu, Buddhist and Hindu — have at their core a commitment to peace and justice that starts with recognition of the struggles of our fellow travelers.

Now, on the cusp of the 78-year anniversary of the liberation of Majdanek (22-23 July, 1944), which was the first of the Nazi camps to be freed by the Allies, we must ask ourselves: does the truth of the Holocaust continue to set hearts and minds, once blinded by ignorance, fear and prejudice, free?

The honest answer is that while Muslim understanding of the Holocaust is important to bringing lasting peace to the Holy Lands, Holocaust ignorance and denial remains a worrisome trend that only worsens with the passage of time.

Trivializing the Holocaust, we know too well, opens pathways to denial and to antisemitism, which still persists in the world, for sure. But it is a cross-cultural, cross-ethnic, cross-national, cross-religion phenomena.

One poll, conducted earlier this year by the American Jewish Committee, found that only 53% of Americans over the age of 18 answered correctly that approximately six million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, while 20% explicitly said they were not sure. In the poll, 2% said that less than one million were killed, 13% chose approximately three million, and 11% said more than 12 million.

The truth can set us free. And the truth of the Holocaust must continue to open our eyes to the horrors humankind is capable of inflicting — and help guide us to the truth of our common humanity and our shared destiny.

But we must live, practice, and teach this truth every day, to keep the shadow of lies and ignorance from again overtaking our world.

We can do this primarily through education and interfaith dialogue. There are ever more interfaith clubs and organizations sprouting across communities and college campuses, including the new Interfaith Research Lab at Columbia University, which I helped inaugurate with Cardinal Timothy Dolan and Rabbi Arthur Schneier.

We can also work to build bridges of peace between the diverse peoples of the world, and be a force for a new, faith-driven diplomacy that compliments the traditional efforts of governments to achieve peace.

This idea is already bearing fruit. Last year, The Muslim World League, together with Christian, Jewish, Shinto and other partners, took part in the G20 Summit of Nations in Bali, Indonesia as the “R20” (the Religion 20), an engagement group aiming to leverage the power of world religions to tackle pressing global challenges.

And just last month, we hosted a high-level interfaith summit of religious leaders and diplomats at United Nations Headquarters in New York, aimed at soothing over growing tensions between east and west.

These are not naïve exercises. Two historical facts are worth remembering. First, it was the Soviet Red Army – which was then allied with America and the West – that liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau, as well as Majdanek, in the 1940s.

Second, while the overwhelming number of victims of Nazi barbarity were Jews, among the murdered at Auschwitz were dozens of Muslims. The lessons here are clear. The clash of peoples is not inevitable. Good can defeat evil. And hate is an all-consuming pyre.

We all rise or fall together. And as we remember the liberation of Majdanek, that is the truth that shall set us free.

Opinion by Dr. Sheikh Mohammed Al-Issa

H/T Imam of Peace

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Let's be fair, right off the bat: Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer," based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book "American Prometheus" by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, is a remarkably accurate look into the life of American scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy). It explores both his experiences working as the director of the Manhattan Project, fighting to build an atomic weapon before the Germans could manufacture their own, as well as the character assassination he endured at the hands of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) as a result of the left-wing ties he cultivated in his youth. Christopher Nolan brings his reliably detail-oriented vision to the project, endeavoring to get as close to the real version of history as possible.

But even with a three-hour runtime, it's inevitable that some historical facts are left by the wayside, whether timelines are consolidated to account for narrative flow, the roles of certain characters are shifted slightly, or elements of the overarching story are neglected. We expect this from most biopics because, at the end of the day, a movie is its own take on the story. But today, we're putting on our pedantic hats and taking a look at the spots where "Oppenheimer" and history diverge.

1. The J in J. Robert Oppenheimer

Early in the film, one of Oppenheimer's colleagues makes a comment about how the "J" in "J. Robert Oppenheimer" doesn't stand for anything. (This would not be particularly unusual for the time — famously, the "S" in "Harry S. Truman" doesn't stand for anything either.) But according to "American Prometheus," Oppenheimer's birth certificate confirms that the J stands for Julius, which was the name of his German Jewish immigrant father. It is perhaps likely that he never went by Julius or any derivative of that name because it's an uncommon practice in most Jewish communities to name babies after living relatives, at least in the Ashkenazi tradition, as it's considered to be bad luck.

That Oppenheimer's family didn't follow this particular superstition demonstrates their somewhat fractured relationship with Judaism. Raised by parents of a generation and class in which the primary goal was to assimilate to American culture, Robert Oppenheimer was Jewish by birth, but observed few religious practices. He was in fact educated primarily within the Ethical Cultural Society, a non-religious group founded by Jewish-born Felix Adler, who wanted to incorporate the elements of humanitarianism he considered cornerstones to Jewish culture without necessarily embracing Judaic faith.

2. The infamous apple incident

It's no secret to anyone familiar with Robert Oppenheimer's life that he had a hard time when he first left home for Cambridge to study physics in the prestigious Cavendish lab. He was considered by many contemporaries to be a little emotionally stunted and not quite mature enough for life on his own. Adding to these difficulties were the fact that he was training in a lab that focused on experimentation rather than theory, an environment in which the notoriously clumsy Oppenheimer did not thrive. Struggling to cope with stress and mental health issues, Oppenheimer impulsively poisoned an apple on the desk of his supervisor, Patrick Blackett.

In the film, he manages to discard the apple and it appears that no one is any the wiser, but in real life (although no one was actually hurt by his stunt) the school found out about what could be interpreted as attempted murder, and it was only with the swift intervention of Oppenheimer's parents that he avoided being expelled or even arrested. He was allowed to stay at Cambridge only under the condition that he met with a London psychiatrist on a regular basis.

3. The ranch in New Mexico

Ever since his teen years, Oppenheimer had a special affinity for New Mexico, a place where he felt more at home than anywhere else in the world. In the film, he mentions to his European colleagues that he misses New Mexico, and that he and his brother have a ranch there. But actually, although Oppenheimer had visited New Mexico several times before attending university in Germany, he and his brother did not own property there until much later.

Robert and Frank — with the financial support of their father — began leasing a ranch there in 1928, the year after Robert returned to the United States upon receiving his PhD, and Robert didn't actually purchase their small western estate, affectionately referred to as "Perro Caliente," until 1947. Still, the Oppenheimer brothers spent many happy months there, and it was Robert's knowledge of New Mexico that led him to suggest Los Alamos as the eventual site of the Manhattan Project.

4. Oppenheimer's teaching skills

Oppenheimer was by all accounts a unique personality in that social skills did not necessarily come easily to him, but like everything else in his life, he was a quick learner. After receiving his PhD and several offers to teach at various universities, he landed at Berkeley as an extremely green professor with little experience in teaching. "Oppenheimer" shows him connecting with students pretty much immediately, standing at the center of an engaged group of young physicists hanging on his every word. But that wasn't quite the experience that his very first advisees remember.

In "American Prometheus," Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin describe his teaching style as "largely incomprehensible to most students" and "more like a liturgy than a physics lecture." Even Oppenheimer admitted how much he had yet to learn about the art of lecturing. After describing some kindly advice given to him from a fellow professor at the time, he wryly said, "So you can see how bad it must have been."

Nevertheless, Oppenheimer eventually developed an ability to support and educate his students, which made the members of his physics department incredibly loyal to him, a skill that naturally complemented his role as director of the Manhattan Project. It was the strong relationships that he had cultivated as a faculty advisor that helped him recruit so many promising scientists to Los Alamos.

5. Running Los Alamos

Similarly, although Oppenheimer was a good choice to lead Los Alamos as a scientist — he intuitively understood how to assess problems in research and help his colleagues find new paths forward — he had little experience as an administrator. When Colonel Groves (Matt Damon) discusses the potential role with Oppenheimer, they mention the fact that none of his former associates considered him adept at the kind of logistical support such a massive project would require. (According to The Harvard Gazette, one commented that "he couldn't run a hamburger stand."). Still, in the movie Oppenheimer seems to have an innate grasp of how to compartmentalize the research in a way that would expedite the process and keep them ahead of the Germans, who had already embarked upon a similar project.

In reality, Oppenheimer had no clue how to run Los Alamos. John Manley, who worked under Oppenheimer on the Manhattan Project, remembered that he "bugged Oppie for I don't know how many months about an organization chart — who was going to be responsible for this and who was going to be responsible for that," a request that was dodged seemingly until Oppenheimer could avoid it no longer (via Science Madness). But again, the physicist proved to be endlessly adaptable, acquiring the skills and temperament required to head one of the most ambitious scientific endeavors in American history.

6. Opinions on Kitty Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer's wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) is represented as a complicated woman in "Oppenheimer." She drinks too much, has trouble connecting with her children, and has a turbulent yet committed relationship with her husband (no small wonder, considering his affairs). But the film doesn't really address how Kitty was viewed within the Oppenheimer circle, which is that ... well, she wasn't very well-liked.

Their romance came about suddenly, when most of Oppenheimer's friends were still quite attached to Jean Tatlock, with whom he had been in a long-term on-again, off-again relationship. Upon learning that Oppenheimer was engaged to be married, his long-time friend and colleague Bob Serber reportedly wasn't sure if he had proposed to Kitty, or to Jean.

Robert's sister-in-law Jackie did not mince words about her feelings towards his new wife. She allegedly called her "one of the few really evil people I've ever known in my life" (per The Decadent Review). While most of his other friends and family members likely wouldn't have gone that far, many in their circle found her difficult, and were open with their opinion that Robert likely wouldn't have married her if she hadn't become pregnant with their son, Peter.

7. Do you want to adopt him?

In "Oppenheimer," Kitty makes a joke to their family friends, asking if they want to adopt Peter to take him off her hands. (This is after already relying upon the Chevaliers to watch him for a month or two when he was just a toddler.) Kitty's lack of attachment to her two children was well-documented, and the throwaway quip depicted in this scene actually had a much more serious grounding in reality. The only difference is that it wasn't Peter who the Oppenheimers offered up to another family, but his younger sister Toni.

Toni was born in the midst of Robert's work on the Manhattan Project, when he barely had time to sleep, let alone be a father. When Kitty suffered from what was likely postpartum depression and left Los Alamos to spend some time away to recuperate, she had one of her friends, Pat Sherr, take care of her infant daughter. "American Prometheus" recounts a moment when, upon visiting Toni at the Sherrs' home, Robert was struck by the feeling that he could not provide the same amount of love and attention as they could, and Sherr remembers him asking, "Would you like to adopt her?" Although the Oppenheimers maintained custody of both of their children, their home was not particularly emotionally warm, although friends and acquaintances spoke of memories in which both Kitty and Robert expressed great affection for Peter and Toni.

8. Einstein and Oppenheimer's relationship

Although Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer were two of the most important scientific minds of the early 20th century, they weren't necessarily the best of friends. Oppenheimer considered Einstein's contributions, though valuable, entirely of the past by the time he was making his name in physics, and Einstein went on the record as being extremely skeptical about the entire field of quantum physics. Despite this, when they worked together at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, they developed a cordial rapport that was based largely on mutual admiration for each other as men and not as physicists.

The scenes in the film that depict Einstein and Oppenheimer conversing at the Institute largely reflect what their actual relationship probably looked like. However, there's little evidence to suggest that Oppenheimer would have approached Einstein during his work on the Manhattan Project to double-check his math on the probability of the atomic bomb accidentally exploding the world. This is partially because they hadn't gotten a chance to get to know each other as individuals at this point — still several years away from working together at the Institute — and also because they were fairly open with the fact that they considered themselves on very different pages when it came to physics.

9. Wire-tapping Oppenheimer A significant portion of "Oppenheimer" takes place during the closed-door hearing in which Robert Oppenheimer appeals the denial of his top-secret security clearance that would allow him to continue working as a government advisor. During this time, we learn that despite efforts to maintain high levels of security at Los Alamos, there was a German-born scientist employed on the Manhattan Project, Klaus Fuchs, who was reporting directly to the Soviets on their research. The film implies that Oppenheimer's inability to have identified espionage within his ranks was the precipitating factor in his being placed under increased scrutiny from the FBI, with surveillance that included wiretaps on all his phones.

But Oppenheimer ran in a very left-wing crowd before the war, and had been under strict surveillance since he was in his late 20s. The film makes reference to thousands of pages of documents on his past and various audio recordings of his conversations, which is why it seems odd that they choose to focus on this moment with Fuchs as a turning point in the government surveillance of Oppenheimer.

10. Oppenheimer's influence in Washington

The part of "Oppenheimer" that takes place after World War II emphasizes Robert Oppenheimer's inability to get the United States government to deal more openly with atomic energy, sharing their research with other countries and engaging in disarmament talks. It also casts him as a naive victim of Lewis Strauss' political machinations to discredit him, through confidential meetings that drag his name through the mud and prevented him from playing a more active role in the atomic conversation throughout the Cold War. And of course, it features the disastrous real-life interaction between Oppenheimer and Harry S. Truman, with the president of the United States calling the scientist a crybaby. None of this is necessarily untrue: In fact, that's pretty much what happened to Oppenheimer.

But by focusing on these elements of his post-WWII career, the film doesn't do credit to the influence that Oppenheimer actually wielded in Washington after the war. A greatly respected physicist, he had the ear of the most important men in government, even if he wasn't always able to convince them to act in ways counter to their fears about the Soviet Union's nuclear capabilities. He was an invaluable government advisor and was on a first-name basis with the U.S. Secretary of State — that's not nothing.

11. Strauss' nomination hearing

When we see Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss in the framing story of "Oppenheimer," he might look like he's on trial, but he's cool as a cucumber. The generally accepted wisdom during these scenes, in which Strauss is taking part in a nomination hearing to become the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, is that he's got the cabinet job in the bag. A Senate aide played by Alden Ehrenreich expresses no doubt that this is all just routine, that they have to go through the motions of a hearing, but that he'll eventually be granted the position is never in doubt. It's only when David Hill testifies against Strauss that the Senate reconsiders, narrowly preventing him from being awarded the prestigious role.

In fact, there was a contingent in the Senate that was determined to see him voted down. Strauss had an enemy in Senator Clint Anderson, and their relationship was so acrimonious that it was described in a 1959 Time article as a "blood feud." The result was a prolonged political battle that saw Eisenhower become just the fifth president to suffer the embarrassment of having a cabinet nomination rejected. And although Strauss' treatment of Oppenheimer was one reason why he wasn't confirmed, it was far from the lynchpin in the case.

12. David Hill's testimony

Towards the end of "Oppenheimer," it begins to feel like Lewis Strauss is a Scooby-Doo villain who's just gotten away with his dastardly deeds. His confirmation as U.S. Secretary of Commerce seems all but assured, granting him greater power and prestige in Washington. But then David Hill (Rami Malek) gives a damning character testimonial, accusing him of destroying Robert Oppenheimer's career for personal reasons and therefore lacking the temperament required for such a privileged role. The effect is immediate: Senators, including a young John F. Kennedy, switch their vote, delivering Strauss the comeuppance he desperately deserves.

David Hill did in fact speak out against Strauss during his cabinet hearing, saying that there was "a kind of madness and irrationality which went through the whole case" in Strauss' efforts to have Oppenheimer's security clearance revoked (per CQ Almanac). But Hill was not actually the only scientist who testified against Strauss at this hearing, railing dramatically against his treatment of Oppenheimer. There was another Los Alamos scientist, David R. Inglis, who was then the chairman of the Federation of American Scientists. Inglis spoke critically of Strauss a week earlier at the hearings, referring to his "substantial defects of character" and the "personal vindictiveness" with which he conducted his dealings with Oppenheimer. This stirred senators to doubt Strauss' fitness for the role long before Hill joined the hearing.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Emily Blunt#Kitty#Lewis Strauss#Robert Downey Jr.#Jean Tatlock#David Hill#Rami Malek

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Lady Lilith”

Painter: Dante Gabriel Rossetti Style: Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Aestheticism, Oil Year: 1866-73 Themes: Beauty, Youth, Mythology Notes: Lady Lilith is an oil painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti first painted in 1866–1868 using his mistress Fanny-Cornforth as the model, then altered in 1872–73 to show the face of Alexa Wilding. The subject is Lilith, who was, according to ancient Judaic myth, "the first wife of Adam" and is associated with the seduction of men and the murder of children. She is shown as a "powerful and evil temptress" and as "an iconic, Amazon-like female with long, flowing hair."

Rossetti overpainted Cornforth's face, perhaps at the suggestion of his client, shipping magnate Frederick Richards Leyland, who displayed the painting in his drawing room with five other Rossetti "stunners." After Leyland's death, the painting was purchased by Samuel Bancroft and Bancroft's estate donated it in 1935 to the Delaware Art Museum where it is now displayed.

The painting forms a pair with Sibylla Palmifera, painted 1866–1870, also with Wilding as the model. Lady Lilithrepresents the body's beauty, according to Rossetti's sonnet inscribed on the frame. Sibylla Palmifera represents the soul's beauty, according to the Rossetti sonnet on its frame.

A large 1867 replica of Lady Lilith, painted by Rossetti in watercolor, which shows the face of Cornforth, is now owned by New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has a verse from Goethe’s Faust as translated by Shelley on a label attached by Rossetti to its frame:

"Beware of her fair hair, for she excells All women in the magic of her locks, And when she twines them round a young man's neck she will not ever set him free again."

More: Lady Lilith

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know. I'm just. tired. I'm tired of seeing how there are so many snakes in the grass of the western Judaic community. People I know who would normally be screaming about genocide, now picking and choosing the news they follow in hopes that all the fake news will be correct, and they'll really get to go live in the magical manufactured world of Israel for free. Islamophobia and racism from people who should understand what hate leads us to. It's already led us to a senseless slaughter over land and natural gas. I and thousands of other activists have spent YEARS trying to disprove claims that Israel represents us or is in ANY way our "home base", and yet, so many of my people - or, those I thought were my people - have let their fear curdle into a victim complex that has thoroughly convinced them that our lives and personal comfort are worth more than the mere existence of Palestinian people.

The moment Israel stops benefiting the US/UK - likely sometime after as many Judaic peoples immigrate there - the US/UK will turn on Israel. They've already given Israel more than enough means to commit condemnable atrocities, and they'll push the blame off themselves and onto the entire Israeli population. Maybe this Israel will get invaded, too. Maybe they'll have weapons tested weapons on them. Who knows anymore? This slaughter is being fostered by boardrooms full of shortsighted oligarchs (of a wide range of nationalities and creeds, might I add) who have no long term planning skills, and they will continue to not care about the worlds they're destroying for fun and profit. I hope all the traitorous Jews of the world really appreciate their stolen vacation homes, because they've only gotten them by completely incinerating the goyische respect and dignity we've fought so hard for.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Rhett’s tattoo and deconstruction update

To the Rhett!tattoo Anon, I had not forgotten my promise to write about it but I intentionally waited for his deconstruction update because it was clear those two would be correlated and together provide more information. Besides, Rhett sort of explained the symbolism behind the tattoo pretty thoroughly and honestly.

The update episode confirmed what has always been clear and even more emphasized by the new tattoo; Rhett has always remained spiritual. I would take it a notch further and consider that he also remains religious in the sense that he actively seeks for a religion, dogma or belief that appears solid enough for him to believe in. In any case, it was a joy to listen to him. We are in a very similar place regarding spirituality, even though the way we landed there couldn’t be more different.

The tattoo is a reminder of where he’s been and where he is going. It has this Judaic / Biblical interpretation of the world as well as heaven and hell, things he factually knows are wrong. He reminds to himself that he started from a wrong place. However, where heaven is supposed to be is the little open door 👀 The little door can take so many meanings but ultimately, like he implied, it is the realisation that all those years of his youth, even when he was wrong, all the circumstances led to his life as it is now, to the changes and choices he has done now. Most things in his life, including his family and his relationship with Link and its evolution to whatever it is now exist because of all this time he was being wrong. Rhett realised the irony that this very religious system he was part of led him to paths and situations and choices and feelings that it itself condemns and ostracises. That religious world opened to him a little door to the unknown, which Rhett implied very cautiously that it might be his own paradise or an opportunity to explore further the ultimate truth.

The deconstruction update was thus not surprising. It wasn’t the main core that I found intriguing (although all the content was interesting) but rather the small details, the hints. Here are some notes:

* Rhett explained how he realised after leaving the faith that he had not changed. He still wanted to love his wife, his kids, his friends. I watched this twice and to be totally honest the second time it didn’t seem to me as strong as the first but I will mention it nonetheless; Link was a little frozen when Rhett said this and responded with a weak “yes” specifically when Rhett said “the loving his friends” part. He remained pensive throughout, I almost thought he was fighting to not look bored or tired but at the same time there was something in his dead / droopy expression that made me feel like he was trying to not get emotional, sad.

* Rhett implied that he was the target of disbelief from his immediate circle when he decided to leave the faith, specifically saying that those close or relatively close people to him that are still Christians accused him that he did not leave the church for the intellectual reasons he has mentioned but for actually ulterior “selfish desires he had” and that “deep inside they always knew Rhett was never genuinely following the spirit of the doctrine, he never belonged”. Now, that’s heavy and prior to that I think Rhett had never made such implications, he only talked about his scepticism. It’s interesting that “some people” said this when at the same time Rhett explains how earnestly absorbed he was by the doctrine. It makes you wonder (not really) what it is those people saw in young Rhett that made them question that Rhett could be a “true Christian” at heart and what “selfish desires” they are talking about. This kind of unpleasant exchanges he may have had with close people could be after all what inspired the song “I think I am supposed to like this”.

* Rhett created a thorough analogy in order to explain his experience leaving the faith and what he encountered in and out of the church, which was not all that different. But the way he phrases everything in this analogy is interesting, including that he equates leaving the faith as “getting out of a house”. And be in the open and free. To accept and love others. And to seek the truth still but without his former conviction that he is the right one.

PS. Link said his deconstruction update will be shorter and that he has found the answer to all of Rhett’s concerns and it’s very easy. I am willing to bet that his answer is love, unconditional love and living in the moment. And that this is the only truth that matters, to him. Link hasn’t healed from the trauma he gradually realised the church left to him and he is still uncomfortable in these discussions.

#rhett and link#randl#rhink#rhett McLaughlin#r&l#ear biscuits#Rhett’s deconstruction update#mythical

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Days of Awe

Rabbi James Prosnit

Jewish Chaplain and Religious Studies Lecturer

The Jewish High Holy Days begin this year on Friday evening, September 15th with the observance of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. At that time Jews around the world enter into a ten-day period of introspection leading up to Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement on Monday September 25th.

We call this period the Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe.

While reflection and repentance are encouraged at all times, it is during this period that the urging is greatest. The shofar blasts serve as an alarm clock awakening us to the possibilities that await. This is a time of reverie not revelry.

A central teaching is that on Rosh Hashanah the “Gates of Heaven” open, only to close on Yom Kippur. During these ten days we have the chance to consider the fabric of our lives. We assess the past year and consider the gap between who we are, and what in our higher moments we know we can be.

Human frailty is a given. But during these days if we are committed to an honest appraisal, in Hebrew we call that chesbon hanefesh, (literally an “accounting of the soul”), God will accept our prayers and grant forgiveness.

One of my favorite teachings is that even before the first human being was created, God established Yom Kippur as a day of repentance. In other words, God knew that these earthlings would have flaws, so God saw the need to create a day and time when we could reflect on our behaviors, seek forgiveness and be granted a fresh start. Of course, we are also taught that these days provide forgiveness for transgressions in our relationship with God. If we’ve wronged someone specifically, we’d better take that up with that person, before we turn our attention to the Divine.

The wish during this season is Shanah tovah u'metukah; not necessarily a Happy New Year, but a good and sweet year filled with blessings, wholeness and peace.

The Fairfield community is invited to attend a Rosh Hashanah reception and celebration on September 24 at 4:45 in front of Egan Chapel, sponsored by Campus Ministry and the Bennett Center for Judaic Studies. It’s a chance to hear the sounding of the shofar (ram’s horn), learn a little more about the festival and taste some of the sweetness of this time of year.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jews of Early America and the Wild West: Bringing the Forgotten from the Grave and Rethinking Their Lives

Back in 1660, the Puritan Minister Thomas Thorowgood speculated that certain Native Americans and Mexican Indigenous Groups, because they practised circumcision, cannibalism (as mentioned in Ezekiel) at times, used certain literary devices (parables) to communicate ideas and some seemingly Judaic rights, descended from Jewish stock(9). How did Jews find themselves in the Americas? It’s supposedly the fulfillment of Ezekiel 5.10, where as punishment for idol worship, the tribes of Israel were to be “scattered to the wind.” It’s all hokum based on conjecture and aspects of culture that are shared across the human experience, except circumcision and cannibalism of course.

Jewish Voices from the Past

Unsurprisingly, many years later, Jews were among those who settled America and the Wild West as well as peopled Ferdinand II’s expeditions to the New World. The West represented a land of hope and new beginnings for many disenfranchised Jews. This experiment in the birth of a new country based on equality was a place “where everything was just beginning and in the process of becoming and, to a certain extent, still is in that condition, where it is still possible to plant the seed of civilization in virgin soil, where the foundation of the structure of the new state of necessity implied the acknowledgment of the common origin of all men and their common right to equality (Israel Joseph Benjamin, My Year in California and the West (6)).” The New World had an allure, despite the potential dangers, it beckoned to those who were Zionists and those who sought a simpler life or merely freedom from persecution alike. In fact, In the earliest days of the American experiment, Isaac Isaacs can be found in Virginia’s public records. By the late 1800’s, Jews could be found as far west as California.

At the offset of the American experiment, conditions looked favorable for Jewish immigrants. In fact, Jews voted if no one challenged them to take a Christian oath and conducted public worship. And, in 1718 Jews won the privilege of naturalization through special acts of the Assembly, a privilege that enabled them to own land (3). However, life on this new frontier wasn’t easy for anyone, especially those Jews who came to the New World in pursuit of religious and economic freedoms. For instance, to obtain the same rights that other immigrants enjoyed, in 1706, Jews of New York City resorted to writing a kind of constitution for their own regulation (3). The years between 1906 and 1718 were hard for even those Jews living in metropolitan centers, business disregarded the rights that were granted by special assembly. In rural areas, the situation was even worse.

Rights aside, there’s a certain pain to becoming American, a loss of identity that only the immigrant understands. In less populated regions hardships were worsened by the lack of a Jewish community and antisemitic ideals forcing those who newly arrived in the New World to take on Gentile customs. For instance, Rebecca Samuels, a polish immigrant living in Petersburg Virginia, a small and isolated town, wrote this in a letter to her family during 1791:

Dear Parents,

I know quite well you will not want me to bring up my children like Gentiles. Here they cannot become anything else. Jewishness is pushed aside here. There are here [in Petersburg] ten or twelve Jews, and they are not worthy of being called Jews. We have a shochet here who goes to market and buys trefah [nonkosher] meat and then brings it home. On Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur the people worshipped here without one sefer torah and not one of them wore the talit or abra kanfot [the small fringes worn on the body], except Hyman and my Sammy’s godfather. The latter is an old man of sixty, a man from Holland. He has been in America for thirty years already, for twenty years he was in Charleston, and he has been living here for four years. He does not want to remain here any longer and will go with us to Charleston. In that place there is a blessed community of three hundred Jews.

You can believe me that I crave to see a synagogue to which I can go. The way we live now is no life at all. We do not know what the Sabbath and holidays are. On the Sabbath all the Jewish shops are open, and they do business on that day as they do throughout the week. But ours we do not allow to open. With us there is still some Sabbath. You must believe me that in our house we all live as Jews as much as we can.

All the people who hear that we are leaving give us their blessings. They say that it is sinful that such blessed children should be brought up here in Petersburg. My children cannot learn anything here, nothing Jewish, nothing of general culture. My Schoene [my daughter], God bless her, is already three years old, I think it is time that she should learn something, and she has a good head to learn. I have taught her the bedtime prayers and grace after meals…(5)

As early as 1759, Newport Rhode Island had a vibrant Jewish community and synagogue, but places like Richmond Virginia didn’t get a place of worship until 1789, Temple Beth Shalom (5).Despite writing the letter in 1791 and the Thomas Jefferson have written the Bill to Establish Religious Freedom in 1779 church and state hadn’t been fully pulled. Besides, Rebecca would’ve still been pressured to live and raise her children like a Gentile.

In contrast, Abigail Minis is, in my opinion, one of the most heart warming biographies herein, she was the embodiment of the spirit of the western frontier. She was a 70 year old widow at the time of the Revolutionary War who made kosher meals for the revolutionary army and fled British occupied Savannah for Charleston. She wrote this to Mordacai Sheftall Esquire, the highest ranking Jewish officer in the colonial forces:

Dear Sir,

Enclosed I have sent you a copy of certificates given me for sundry Articles provision, [?] delivered the Allied Army When before the lines of Savannah in September 1779 immediately after the Surrender of this Town to the British I gave the Original Certificate to General Lincoln. Who promised to have settled and paid, but the communication between Philadelphia [the US capital at the time] and this place being totally stopt [I] have not heard from him(5).

If Jews had few rights at the time, even in metropolitan centers rights were granted and revoked or granted and dismissed by businessmen (3) Jewish women of the Frontier had even fewer rights and freedoms. Most women of this period made a name for themselves by proxy, Betsy Ross, for example, only became the seamstress of the flag through marriage. Early American women lived through their husband’s accomplishments. Yet, Abigail Minis bumped elbow’s with the elite and even ran her own inn. She broke the rules, where Rebecca lived the life of the Jew who was broken by Gentile society, Abigail made her own rules. Minis is the embodiment of the American experiment and the westward expansion.

It wasn’t just Abigail and Rebecca who had to buck the system and carve their own path. Michael Allen was a chaplain for Northern Jewish soldiers during the Civil War. “Although Allen had never been ordained, he was allowed to act in place of an ordained Rabbi because there were so many Jewish soldiers in the Cameron Dragoons, who were mounted soldiers with heavy arms.” Interestingly, a special act of Congress had to be passed in order for Allen to perform his duties, because he wasn’t a Christian(4). This incident occurred well past it was declared that the “free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be.” In New York, Jews had won the right to bury their dead within city limits(5), but on the battlefields, where the dangers of both being scalped and killed by the Confederate Army prevailed, a special act was required for a Rabbi to say the Kaddish with mourners.

Between 1848 and 1888 the Gold Rush drew people from all walks of life out west. The promise of financial freedom and overall freedom was alluring to Jewish pioneers. You may be surprised to find that Jews “constituted on of the more prominent ethnic groups of the California Gold Rush (10).” A modern, hands-on approach was used to determine if individuals of the Gold Rush era or any period in American history were Jews. To find the forgotten Jews of the Gold Rush the writers of The Jews in the California Gold Rush used the inscriptions of gravestones, public documents in county courthouses, probate records, newspaper and Jewish organizations. It’s said that “the Gold Rush was a significant event in Jewish history because it placed Jews side by side with a large and diverse group of races, religions, and nationalities. At first, the Jews were strangers who made their homes among strangers, but they became friendly with their Gentile neighbours and were soon important figures in the communities in which they lived. They established themselves in business, and they also remained true to their ancestral faith by forming benevolent societies, establishing separate cemeteries, and conducting worship services (10).” Too bad these histories were largely forgotten until recently, not to mention, this is a somewhat optimistic notion of living among less than accepting Gentiles.

Why were early American Jewish contributions to the Wild West and Frontier left out of history books? This is because, the chronicles of Jews in America had always focused on “the metropolitan centers of the East and Middle West(6).” Accounts of Jews in the American West had long been considered “peripheral to mainstream Jewish America, at best and tributary and derivative and of no serious interest(6).” But there were Jewish pioneers wearing kippah under their ten gallon hats. It just took 100 years to discover this. In the 1960’s, among Social Scientists, methods of research became more hands-on, as earlier noted, and historians and the like scoured dusty genealogies left to rot in old west courthouses and microfiche to unearth the forgotten, or never known, legacies of Jews of early America and the Wild West(6). Most Jews of this American era disguised themselves as Gentiles to escape persecution and fit into the society at large. Jewish rights in the old west were tentative at best, granted and revoked or just ignored. For example, during the election of 1737 Jews were disallowed to vote for assemblymen or give testimony in a court of law(3). Those rights that were granted in 1718 suddenly evaporated. In the end, those rights that the Jews of New York made a “constitution of their own ‘’ to protect had been taken away again. It was best to fiend the life of a Gentile on the new Frontier.

Despite the tentative status of Jewish rights in the New World, Jewish communities in America were established in New York as early as 1654, followed by communities in

A few small communities in the original colonies withstanding, Jews didn’t begin to see America as a possible place to recreate Zion, a new land to prosper without persecution until much later. In fact, the first attempts to create communes didn’t happen until in the 1820’s in Florida. Later, in 1881 Jews attempted to make a colony on Sicily Island Louisiana. In 1882 there were several attempts to establish Jewish colonies in S. Dakota but all 6 colonies failed due to crops and malaria. And, in 1904 a colony was established in Colorado but it too failed. Some of the most notable examples of the American Kibbutz are the New Odessa and Clarion colonies. To make forge this community, JACA and The Jewish Agricultural Aid Society purchased 6,085 acres of public land in Sanpete County, Utah. The initial plan was to settle roughly 200 families on the colony, with the number eventually growing to 1,000 families(6). The New Odessa Community was a land where Russians could escape persecution from the Russian Czar.

Biographies of Early American Jews

To Carvalho’s dismay, the expedition already had a photographer, a man who I can only find his last name, Bomar. Bomar used the wax method but Carvalho championed the daguerreotype method for processing film. Fremont held a contest between the two men, speed was the deciding factor. In the end, Bomar’s wax process required more time and would have caused delays(4).

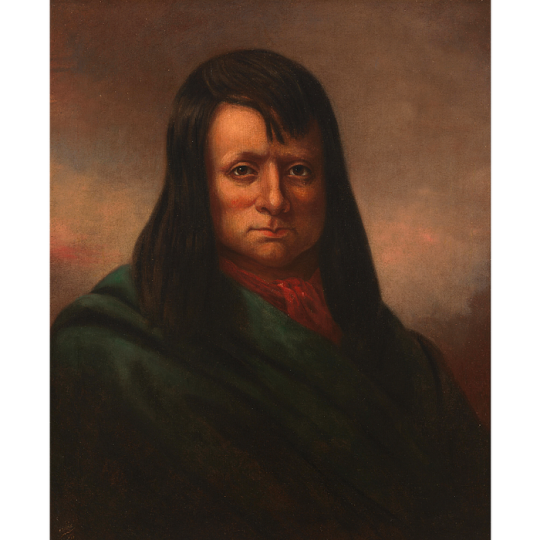

So, Carvalho became the expedition’s official photographer. Along this voyage, Carvalho met Brigham Young, the founder of the Church of Latter Day Saints and Governor. It was in Utah, in the midst of a massacre, with Brigham Young that Carvalho met the Ute Chief, Wakara. He said of the Ute Indians:

“The first principle among them was life for life; it made no difference whether, in their wrath they massacred an innocent, or an unoffending man; a white man slew my brother, my duty is to avenge his death, by killing a white man. Their first Open demonstration was the massacre of Gunnison; and the allied troops of Utahs, Pahutes, Parvains, and Payedes determined to continue in open hostility, both to the Mormons, and Americans(1).”

When Young’s cavalcade arrived at the Ute camp he sent the message that he was ready to meet with Wakara. Wakara responded with “If Gov. Young wanted to see him, he must come to him at his camp, as he did not intend to leave it to see any body.” When this message was delivered to Young, he gave orders for the whole cavalcade to proceed to [the] camp. If the mountain will not come to Muhomet, Muhomet must go to the mountain(1).” When the cavalcade entered the camp, they found Wakara surrounded by 15 old chiefs.

Carvalho noted that “[Wakara] stood upon the dignity of his position, and feeling himself the representative of an aggrieved and much injured people, acted as though a cessation of hostilities by the Indians was to be solicited on the part of the Whites, and he felt great indifference about the result.” Negations for a peace treaty went on and Carvalho remained in camp, near Wakara’s Village until next day, he was able to get Wakara agree to sit for his portrait as well as Chief Squaeh-head, Baptiste, Grosepine, Petetnit and Kanoehe, the Chief of the Parvain Indians(1). Of Carvalho’s work, portrait of an Ute Chief, 1854, is the most striking.

Later, accompanied by two interpreters and several other gentlemen, “we proceeded to the Indian’s camp, to see their celebrated Chieftain, Kanoshe, whose portrait I was anxious to obtain. I found him well armed with a rifle and pistols, and mounted on a noble horse. He immediately consented to my request that he would sit for his portrait; and on the spot, after an hour’s labor, I produced a strong likeness of him, which he was very curious to see. I opened my portfolio and displayed the portraits of a number of other Ute chiefs, among which he selected Wakara, the celebrated Terror of Travellers, anglicised Walker, (since dead). He took hold of it and wanted to retain it(1).” Throughout this article, I’ve given my interpretation of the scene, but this needs none. I don’t know if one might say that Carvalho found the best of all possible worlds in Utah, living among Indians and in constant danger, or if life would’ve been better for him in the relative safety of New York. The painting now resides in the Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Rather than give a single biography of a Gold Rush era Jew, I believe that the reader is aware of life during the period, if was wrought with hardship, it was a time of physical labor and a time of feast and famine for the average panhandler, I’d rather include excerpts from newspapers that describe the general attitude towards those who ventured to California to unearth what lay beneath the ground.

A Jew of our acquaintance came in to his neighbor’s place of business, yesterday morning, bringing an intolerable smell with him, and, “fast as a little wagon,” made the announcement that he had killed a “vesel [weasel],” in his “schicken house.” He said the animal was “black, mit a vite tail, and schtinks like de tuyvel [with a little tale and stinks like a turtle].” A wicked wag, next door, persuaded the victor to bring in his trophy, as he wanted to buy the skin. The Jew soon appeared and drew from his pocket a half grown pole cat(10).”

The Wild West wasn’t Zion, nor a land of dignity where “acknowledgment of the common origin of all men and their common right to equality” existed. In fact, The Grass Valley Union posted this:

Dead at Last… We had almost forgotten to say that it undertook to run all the disloyal Irish and Jews out of the State…. It is now thoroughly dead, we are assured — dead beyond the power of resurrection — and the general opinion is that it lived too long. Sorrowers over its death are found only among the poor printers who were swindled out of their wages(10).

Gold Rush California was yet another land of antisemitism. On the few occasions when local Jews battled Gentiles, the newspaper editor was likely to report the event in as much detail and as humorously as he was able.