#john erasmus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

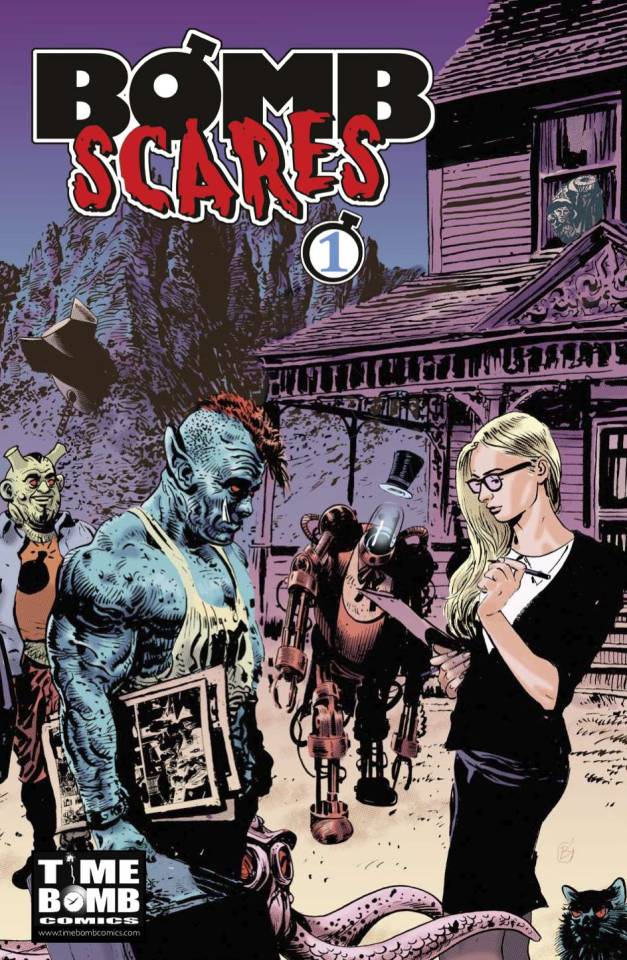

Crowdfunding Corner: Bomb Scares #1

Crowdfunding Corner: Bomb Scares #1. Fans of EC horror will want to check this out! #comics #comicbooks

Backer Beware: Crowdfunding projects are not guaranteed to be delivered and/or delivered when promised. We always recommend to do your research before backing.Disclosure: Graphic Policy’s founder Brett is a member of the Zoop team. Tick-tock, tick-tock…It’s time to stop the clock! Time Bomb Comics’ Bomb Scares #1 is crowdfunding on Zoop! The concept of this series is a simple one: Inspired by…

View On WordPress

#alex nino#bomb scares#david windett#horror#hunt emerson#jimmy broxton#john erasmus#liam sharp#time bomb comics#trevor von eeden#zoop

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another great product from the folks at Time Bomb Comics (funded thro Kickstarter) over here in the UK - Bomb Scares Vol 2 with a cover by John Erasmus!

This volume came with 6 prints due to the extra money generated on Kickstarter!

#comic books#british comics#kickstarter#bomb scares#uk indie#john erasmus#steve tanner#horror#time bomb comics

0 notes

Text

Crowdfunding Spotlight: Time Bomb Comics Bomb Scares is back (and more Quantum, too)

Bomb Scares from Time Bomb Comics, the horror anthology, is waiting to greet you once more!

View On WordPress

#Alex Nino#Bomb Scares#David M. Windett#downthetubes News#Horror Comics#Hunt Emerson#Jimmy Broxton#John Erasmus#Liam Sharp#Time Bomb Comics#Trevor von Eeden

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Willoughby Family Album: Volume IV

Louisa's platonic friendship with next-door neighbour Marmaduke is still going strong.

And despite a bit of a false start with schoolmate Erasmus, who didn't seem to appreciate their ribald sense of humour...

they soon establish a rapport.

But it's Sally that has caught their attention, and although she seemed reluctant to begin with, she readily agrees to a date.

Romance Sim Louisa of course makes the first move.

But to be honest, Sally seems just as keen.

They're completely stuck on each other.

Despite achieving a huge personal milestone, Caroline doesn't look happy.

And she's apparently oblivious to her teenage offspring making out very enthusiastically in the living room with a girl she's never met before.

Perhaps the continuing rift with husband John is weighing on her more than she'd like to let on?

And in the end, she opts for a reconciliation, but entirely on her terms of course.

#sims 2#gameplay#merybury#john willoughby#caroline bingley#louisa willoughby#louie willoughby#marmaduke elton#erasmus collins#sally fairfax#willoughby family

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In modern times, views have ranged back and forth about the benefits of breastfeeding as opposed to those of formula milk. Today, though, twenty-first century mothers are assured by medical practitioners that 'breast is best'. Hundreds of years before the development of formula milk, it was not so much a debate about whether breast was best for Tudor babies, as whose breast was best.

Most writers on the subject considered breastfeeding to be the mother's duty. 'It were fit, that every mother should nurse her own child,' asserted the author of The Nursing of Children. There was nothing so good to nourish a child, agreed the influential physician Dr John Jones, than its mother's own milk. For other scholars breastfeeding created an unbreakable bond between mother and child, with Erasmus going so far as to liken wetnursing to 'a kind of exposure'. It was a mothers' duty, said Thomas More, and only 'death, or sickness' should prevent it. Elizabeth Clinton, Countess of Lincoln, put it more forcefully in the early seventeenth century, when she wrote a tract – ostensibly addressed to her daughter-in-law – on the godly duty of 'every mother' (as she declared) 'to nurse her own children'.

The countess acknowledged, among other common objections, 'that it is troublesome; that it is noisome to one's clothes: that it makes one look old'. But she pooh-poohed these, since 'all such reasons are uncomely, and unchristian to be objected', as 'they argue unmotherly affection, idleness, desire to have liberty to gad from home, pride, foolish finesse, lust, wantonness, and the like evils'. In any event, she assured her reader, 'behold most nursing mothers, and they be as clean and sweet in their clothes, and hold their beauty, as well as those that suckle not'.

It was the greatest regret of the countess, who had been a Tudor mother herself, that she had been discouraged from breastfeeding. 'I should have done it', she candidly told her reader, but had been overruled by another's authority. She had also not considered properly 'my duty in this motherly office'. Now she knew the correct path, but lamented that 'it was too late for me to put it in execution'. It was unnatural to send a child to be nursed, she declared, both for the mother's own child and also that of the nurse, and she warned: 'be not accessory to that disorder of causing a poorer woman to banish her own infant, for the entertainment of a richer woman's child, as it were, bidding her unlove her own to love yours'.

Yet, while poorer Tudor women had little choice but to feed their children for themselves, most upper-class women did not nurse their own babies. All but a few mothers of Lady Clinton's class employed wet-nurses. Elizabeth of York would certainly have been aware of the debate surrounding maternal breastfeeding, but social pressures – to cede the daily care of the infant and to quickly return to fertility – were the more powerful drivers. There was no question of her, or a great many other Tudor mothers, nursing their own child.

— The Lives of Tudor Women (Elizabeth Norton)

#book quotes#elizabeth norton#the lives of tudor women#history#poverty#classism#employment#tudor period#britain#england#family#babies#parenting#mothers#motherhood#food and drink#breastfeeding#wetnursing#john jones#erasmus#thomas moore#elizabeth clinton countess of lincoln

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tapestry of History, 10 – The Rise of the West, 5 – The Reformation, 1

(Image – Desiderius Erasmus around the time of the publication of In Praise of Folly) The Reformation began as a protest movement. It gave birth to the third great branch of Christianity, Protestantism. Its founders did not at first intend to separate from the Roman Catholic Church, but to inspire reform from within it. Although a handful of individuals are usually credited with founding the…

#Albigensians#Brethren of the COmmon Life#Cathars#Erasmus#Holy Roman Empire#Husites#In Praise of Folly#John Hus#John Wycliffe#Lollards#Saint Francis of Assisi#The Imitation of Christ#Waldensians

0 notes

Note

do you have any reading recs (books, ~scholarly articles, whatever) in the same vein as this post? (doesn't need to be a super long list, i'm content to branch off with the works cited of whatever you come up with...) as always, love your blog!! :-)

yes :3 split roughly by subtopic, bolded some favs

Evolution in England prior to (Charles) Darwin

Cooter, Roger. The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organisation of Consent in Nineteenth Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1985).

Desmond, Adrian. The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1989).

Elliott, Paul. “Erasmus Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and the Origin of the Evolutionary Worldview in British Provincial Scientific Culture, 1770–1850.” Isis 94 (1): 1–29 (2003).

Finchman, Martin. “Biology and Politics: Defining the Boundaries.” In: Lightman, Bernard (Ed.). Victorian Science in Context. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1997), 94–118.

Fyfe, Aileen. Steam-Powered Knowledge: William Chambers and the Business of Publishing, 1820–1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2012).

Harrison, James. “Erasmus Darwin’s View of Evolution.” Journal of the History of Ideas 32 (2): 247–64 (1971).

McNeil, Maureen. Under the Banner of Science: Erasmus Darwin and his Age. Manchester: Manchester University Press (1987).

Ospovat, Dov. “The Influence of Karl Ernst von Baer’s Embryology 1828–1859: A Reappraisal in Light of Richard Owen’s and William Benjamin Carpenter’s ‘Palaeontological Application of Von Baer’s Law.’” Journal of the History of Biology 9 (1): 1–28 (1976).

Rehbock, Philip F. The Philosophical Naturalists: Themes in Early Nineteenth-Century British Biology. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press (1983).

Richards, Robert J. Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behaviour. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1987).

Rupke, Nicolaas. Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2009 [ 1994]).

Secord, James. Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2001).

van Wyhe, John. Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism. London: Ashgate (2004).

Winter, Alison. “The Construction of Orthodoxies and Heterodoxies in the Early Life Sciences.” In: Lightman, Bernard (Ed.). Victorian Science in Context. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1997), 24–50.

Yeo, Richard. “Science and Intellectual Authority in Mid-Nineteenth Century Britain: Robert Chambers and Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.” Victorian Studies 28 (1): 5–31 (1984).

Edinburgh Lamarckians and Scottish transmutationism

Desmond, Adrian. “Robert E. Grant: The Social Predicament of a Pre-Darwinian Transmutationist.” Journal of the History of Biology 17 (2): 189–223 (1984).

Jenkins, Bill. Evolution Before Darwin. Theories of the Transmutation of Species in Edinburgh, 1804–1834. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (2019).

Secord, James. “The Edinburgh Lamarckians: Robert Jameson and Robert E. Grant.” Journal of the History of Biology 24 (1): 1–18 (1991).

Corsi, Pietro. ‘Edinburgh Lamarckians? The Authorship of Three Anonymous Papers (1826–1829)’, Journal of the History of Biology 54 (2021), pp. 345–374.

Darwin and Darwinism

Desmond, Adrian and James Moore. Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist. New York: W. W. Norton & Company (1994).

van Wyhe, John. “Mind the Gap. Did Darwin Avoid Publishing his Theory for many years?” Notes & Records of the Royal Society 61 (2007), 177–205.

Sloan, Philip R. “Darwin, Vital Matter, and the Transformation of Species.” Journal of the History of Biology 19 (3): 369–445 (1986).

Phillip R. Sloan, “The Making of a Philosophical Naturalist.” In: Hodge, Jonathan and Gregory Radick (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Darwin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2009), 17–39.

Sponsel, Alistair. Darwin’s Evolving Identity: Adventure, Ambition, and the Sin of Speculation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2018).

Young, Robert M. “Malthus and the Evolutionists: The Common Context of Biological and Social Theory.” Past & Present 43 (1969): 109–45.

Young, Robert M. “Darwin’s Metaphor: Does Nature Select?” The Monist 55 (3): 442–503 (1971).

Bowler, Peter J. The Non-Darwinian Revolution: Reinterpreting a Historical Myth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (1988).

Bowler, Peter J. The Eclipse of Darwinism: Anti-Darwinian Evolution Theories in the Decades Around 1900. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (1983).

Hale, Piers J. “Rejecting the Myth of the Non-Darwinian Revolution.” Victorian Review 41 (2): 13–18 (Fall 2015).

Lightman, Bernard. “Darwin and the popularisation of evolution.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society 64: 5–24 (2010).

Richards, Robert J. The Meaning of Evolution: The Morphological Construction and Ideological Reconstruction of Darwin’s Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1992).

Ruse, Michael. The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1979).

Lamarck and Lamarckism

Barthélemy-Madaule, Madeleine. 1982. Lamarck, the Mythical Precursor: A Study of the Relations between Science and Ideology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Burkhardt, Richard. 1970. Lamarck, Evolution, and the Politics of Science. Journal of the History of Biology 3 (2): 275–298.

Burkhardt, Richard. 1977. The Spirit of System: Lamarck and Evolutionary Biology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Corsi, Pietro. 1988. The Age of Lamarck: Evolutionary Theories in France, 1790–1830. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Corsi, Pietro. 2005. Before Darwin: Transformist Concepts in European Natural History. Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1): 67-83.

Corsi, Pietro. 2011. The Revolutions of Evolution: Geoffroy and Lamarck, 1825–1840. Bulletin du Musée D’Anthropologie Préhistorique de Monaco 51: 113–134.

Jordanova, Ludmilla. 1984. Lamarck. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spary, Emma C. 2000. Utopia’s Garden: French Natural History from Old Regime to Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like the way the theme of myth and story wove itself through the previous episode, this week's episode features the idea of loyalty, what it means, and what it costs.

John Blackthorne's loyalty is split between the men of the Erasmus, long held in Edo, and Toranaga, the lord who has made him his vassal and bannerman. Both still bind him at the beginning of the episode — he accompanies Toranaga's limping army to Edo, despite his bitter proclamation at the end of the previous episode that they're "all dead" — but by the mid-point those ties have begun to fray. Toranaga keeps him at arm's length, not offering him residence inside the castle, and his men, so long sought-after, have spent the past months drinking and whoring, and despise him for his ambition in sailing them to Japan. (Here Blackthorne claims loyalty once more; "we had orders" to cross the ocean, he tells his crewmate, although with less conviction than he normally offers.) With both recipients of his loyalty indicating that they care little for it, his sense of duty turns inward, as he thinks about how he might best serve himself.

That attempt leads him to Yabushige, who at times during their audience seems tempted by Blackthorne's offer of alliance. But the presence of Omi and Mariko are sufficient to remind him that to agree would be a betrayal of his oath to Toranaga. Mariko is offended enough to censure Blackthorne. "You see, once loyalty begins, it does not have an end. Otherwise it would not be loyalty," she tells him. "But loyal turns senseless very quickly when the order is suicide," he replies, which she takes as a personal rebuke.

In a way, he's right. Mariko's loyalty is blind; she will follow Toranaga's will, even if it means her own death. Perhaps maintaining that loyalty is easier for her, given that she already wants to die. (That desire, of course, comes from a sense of loyalty to her own father, a self-sacrificial duty she has carried for nearly fourteen years.) But her uncompromising loyalty does not extend universally: she is dutiful to Buntaro as a husband, keeping away from Blackthorne's bed and remaining silent when he asks if she is "still under the Anjin's spell," but disdainful of him as a man, rejecting his plan for the two of them to die together. Once broken, some ties can never be remade.

Other examples of loyalty appear throughout the episode. Ishido asks for Lady Ochiba's hand in marriage, but she hesitates, knowing that loyalty to him as a husband would mean something far weightier than loyalty to him as a political ally. Out of lordly duty, Toranaga keeps his promises to Gin and Father Alvito, granting them both land in his city of Edo. (Although, with a dash of brilliant irony, the plots are adjoining, putting the brothel next door to the church.)

But undoubtedly the greatest act of loyalty — one that is neither blind nor opportunistic — belongs to Hiromatsu. The only one who Toranaga trusts with the outline of his plan, Hiromatsu must playact at protest in front of the assembled retainers, but the sacrifice he makes to convince them of Toranaga's determination to surrender is viscerally real. The words they volley back and forth speak of loyalty and duty ("Lord! Your vassal dies in vain!"), but it is the last thing Hiromatsu says to his friend — "Then this is farewell" — that is spoken without a hint of artifice. The retainers' initial frustration — how do you remain loyal to someone who has seemingly abandoned their responsibility to you and to themselves? — soon turns to horror in the face of what is being acted out in front of them, all part of Toranaga's larger plan. And Toranaga can only watch as Hiromatsu disembowels himself, even as he understands the necessity of the act. As he tells Mariko later, "Hiromatsu, my old friend, knew his duty well."

As for Toranaga, his true loyalties — like his secret, third heart — have not always been easy to discern. But by the end of this episode, it is clear that he remains loyal to the memories of his son and his friend. Their sacrifices, like their continued belief in him, will not have been in vain.

#shōgun#shogun#shogun 2024#shogun fx#fx shogun#shogun spoilers#1x08#john blackthorne#kashigi yabushige#toda mariko#toda hiromatsu#yoshii toranaga#meta

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

list (alphabetical) under the cut

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Dante and Virgil (1850) [5]

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601) [18]

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (attributed to), Judith and Holofernes (1607) [11]

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Tooth Puller (1609) [22]

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (1610) [13]

Jan de Baen, The Corpses of the De Witt Brothers (1672-75) [25]

Valentin de Boulogne, Martyrdom of Saint Processus and Martinian (1629) [6]

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross/ The Gross Clinic (1875) [30]

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes (Florence, 1614-21) [10]

Théodore Géricault, Arms and Legs: Anatomical Study (1818) [9]

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of Medusa (1818-19) [8]

Théodore Géricault, Anatomical Pieces (1819) [27]

Genoese School, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (17th century) [15]

Francisco de Goya, The Third of May 1808 (1814) [24]

Francisco de Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son (1819-23) [4]

Simon Marmion, Christ of Pity (1480) [17]

Caspar Netscher (attributed to), Slaughtered Pig (1660-62) [26]

Nicolas Poussin, Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus (1628) [7]

Nicolas Régnier, Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene (1625) [20]

Ilya Repin, Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1883-85) [23]

Salvator Rosa, The Torture of Prometheus (1646-48) [2]

Pieter Paul Rubens, Prometheus Bound (1611-12) [1]

Pieter Paul Rubens, The Entombment (1612) [16]

Pieter Paul Rubens, Head of Medusa (1617-18) [29]

Pieter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring His Son (1636) [3]

Francesco Rustici, Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene (1610-25) [21]

Chaim Soutine, Beef Carcass (1923) [28]

Eugène Trigoulet, The Precursor (1894) [14]

Rembrandt Van Rijn, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) [31]

Rembrandt Van Rijn, Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist (1640-45) [12]

Rembrandt Van Rijn, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Dejman (1656) [32]

François-André Vincent, Saint Sebastian (1789) [19]

494 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, y’all, it’s Weird Wednesday! Where on some Wednesdays, I blog about weird stuff and give writing prompts.

Today: The Greenbrier Ghost: Testimony from Beyond the Grave

In October 1896, Elva Zona Heaster (called Zona) married Erasmus (or Edward) Stribbling Trout Shue after a brief courtship. Zona was found dead in their home the following January. The family doctor recorded “childbirth” (presumably meaning miscarriage) as the cause of death. However, Zona’s mother, Mary Jane Heaster, was sure her daughter had been murdered by her new husband. Her proof? Zona told her so. After she died.

To be fair, the whole thing was a bit suspicious. A whirlwind romance and marriage to a near stranger, then a death within months. It turned out Shue had an ex-wife who accused him of abuse and a second wife who also died suddenly after marriage in an accident. Oh, and Shue was quite protective of Zona’s body, and would let no one examine her, especially the neck.

After Zona’s burial, Mrs. Heaster claimed she was visited four times by her daughter’s ghost, who said her husband had broken her neck in a rage over dinner being delayed.

It is, of course, possible that Mrs. Heaster made up the story to put pressure on the law to act. But even without the ghost’s account, prosecutor John Alfred Preston agreed there was enough reason to exhume the body and perform an autopsy.

Check out the blog post for the whole story and some ghostly writing prompts, such as:

Liar, liar. So let's say your ghost character appears and names their murderer, but the person they talk to purposefully misreports it for their own reasons. What recourse would a ghost have in this case? They might try appearing to someone else. Or they might try forcing the witness to tell the truth—maybe scaring them into it, or enlisting the help of Something Awful from beyond the grave.

DannyeChase.com ~ AO3 ~ Linktree ~ Weird Wednesday writing prompts blog ~ Resources for Writers

Image credit

#Dannye writes#Weird Wednesday blog#writing prompts#writing inspiration#horror prompt#scifi prompt#fantasy prompt#writing#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writeblogging#writing community#blogging#horror#scifi#fantasy#ghosts#haunting#greenbrier ghost#mystery#courtroom drama

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

frankly the idea that putting services into english was for "the good of the people" and that medieval people did not understand religion due to the use of latin feels rather insulting; it seems to suggest that the christianity of the (protestant) educated elite was the correct form of worship and that a more popular [in the sense of 'of the people'] form of (at least in medieval and tudor england) catholicism was a wrong of the uneducated that needed to be righted - despite the fact that the average medieval/tudor person would not exactly have been unaware of the religion that pervaded their life. there were other ways to reinforce the messages of christ to an illiterate or monolingual populace beyond translating scripture into english: mystery plays; paintings; preaching; parables; holy days; literature; pilgrimage; and, of course, more. particularly in england this tends to be an aspect of a protestant narrative of history - that protestantism's return to scripture and vernacular bibles would encourage a better, personal understanding of faith, and that being able to understand the bible and communion was for the good of the people. yet if the western rising was anything to go by, many people actually objected to the intrusion of english worship on latin as the liturgical language of the church - part of this may have been due to cornish being the native of language of many of the rebels and therefore making english an incomprehensible intrusion as much as if not more so than latin, but the fact remains that plenty of ostensibly uneducated and illiterate people saw the possibility of worship in a language they understood (the rebellion was centred in cornwall and devon, so many rebels would have spoken english) and rejected it.

the idea of translation and returning to scripture was also not the sole property of protestants - renaissance humanism was the domain of many catholics as well, including the famous erasmus and thomas more, who also saw the virtues of returning to the latin and original greek! the new testament was even translated into english by catholics in 1582 - less than fifty years after the first complete bible in english was published in england, itself hardly renowned for being protestant despite being heavily influenced by william tyndale's translations. one of the problems lies in the fact that henry viii's faith was largely idiosyncratic and doctrinally conservative despite his genuine interest in reform; the second lies in the fact that before the second half of the sixteenth century, catholic and protestant were not coherently defined ideologies or positions, and in fact the words catholic and protestant did not exist. the history of vernacular translations and its relationship with the catholic church and heresy is complicated, but there exist translations of the four gospels as early back as the tenth century; alfred the great ordered the translation of the ten commandments and the laws from exodus; richard rolle translated the psalms into english in the 1340s. the suggestion that the catholic church forbade vernacular translation throughout its history first of all rather misses the point - at the point that the vulgate bible was written, latin was a vernacular language. this is why the latin bible is known as the vulgate - vulgate comes from latin vulgātus, and literally means 'broadcast, published, having been made known among the people[/common]'. it also ties into the idea that the medieval catholic church was a backwards institute which wished to repress... every form of learning? which is obviously false - the catholic church wished to condemn and repress heresy, as it indeed did when john wycliffe produced the wycliffe bible, notorious both for being an early translation of the bible into english and for wycliffe's association with 'proto-protestant' ideas. medieval and catholic are not synoymous with backwards!

insert conclusion here about how patronising it is to assume that all working class english catholics were simply ignorant to the truth and discovering protestantism would instantly make sense to them and how frustrating it is when people conflate commonly held protestant ideals with Things Catholics Never Do. the end

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A clay pipe with silver rim, mounted on a rough piece of wood, originally from the 1845 Northwest Passage expedition led by Sir John Franklin. The bowl of the pipe still contains tobacco and is covered with a glass lid. On the front of the wooden bowl is a plaque with the inscription "First traces of Franklin's Expedition found at Cape Riley 23rd Augt 1850".

The pipe was found, along with other relics, by Captain Erasmus Ommanney and his party when he landed HMS Assistance at Cape Riley on the Isle of Devon on 23 August 1850. These were the first tracks found by the Franklin expedition. The note he left in a cairn at the site states that he "found traces of a camp and collected the remains of materials which evidently prove that a party belonging to Her Majesty's ships were examined in detail at this place. Sherard Osborn recalled: "Numerous traces of English seamen who had visited this place were discovered in various pieces of rags, ropes, broken bottles, and a long-handled instrument designed to rake things up from the bottom of the sea; traces of a campsite were also visible…" Ommanney kept some of these items and after his death his widow donated them to the Museum of the Royal United Services Institution in 1905.

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535 CE) was a lawyer, scholar, statesman, and Lord Chancellor to Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) who was executed in July 1535 CE for his refusal to endorse Henry's break of the Church in England from the Catholic Church in Rome.

The highly principled More also disagreed with the king's divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536 CE) and especially Henry's promotion of himself as head of the Church of England instead of the Pope. Prior to his time in politics, Thomas More was a celebrated author and scholar, his most famous work today being Utopia which includes a philosophical description of an ideal society set on an island. Thomas More was made a saint in 1935 CE by the Catholic Church.

Early Career & Writings

Thomas More was born in London in 1478 CE, his father being the lawyer Sir John More. The young Thomas was educated at Saint Anthony's school in the capital while as a teenager he worked as a page at the house of Archbishop John Morton. He graduated from Oxford University in 1496 CE and went on to study law at Lincoln's Inn. More spent four years in a Carthusian monastery but decided not to take his vows and fully join the priesthood.

In 1504 CE More began his 30-year political career and entered Parliament. The next year he met the famed scholar Desiderius Erasmus whose humanist philosophy would influence Thomas' own work. More became the under-sheriff of London in 1510 CE, but he suffered the tragedy of his first wife's death during childbirth in 1511 CE. His career continued apace, though, with his appointment as Master of Requests in 1514 CE and his participation in a royal trade delegation to Flanders in 1515 CE.

Continue reading...

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rugby player and commentator Gordon Lamont Brown was born on the 1st November 1947.

Known quite simply as Broon fae Troon, Brown was from a sporting family, his elder brother Peter also played for and captained the Scottish side. His father, John played goalkeeper for the Scottish football side and also appeared in the Scottish Open at Royal Troon alongside golfing greats such as Arnold Palmer. He is also the nephew of footballers Tom and Jim Brown.

Broon was a legendary Scotland second row and a fully-paid up component of the Mean Machine; a triple Lion and fierce competitor in the Battle of Boet Erasmus; a ruthless assassin on the pitch and a true gentleman off the field of play.

early interest was in the round rather than the oval ball. His conversion was reportedly the result of a particularly heated football tie, after which he reckoned ‘rugby would be safer’! He emerged on to the international stage in December 1969, from West of Scotland, having just turned 22.

After a winning debut against South Africa, he retained his place for the Five Nations opener against France. Dropped for the subsequent Wales match, he was replaced by brother Peter who revelled in breaking the news to Gordon. Peter was then injured in the match – and replaced at half-time by his younger sibling; the first occasion where a brother had replaced a brother in an international. When the Browns joined forces against England in 1970, it was the first time brothers had played together for Scotland since Angus and Donald Cameron in 1902.

Immovable in the scrum yet dynamic in the loose, Gordon went onto cement his place in Scotland’s front five of the early 1970s, the formidable Mean Machine that also featured Ian McLauchlan, Frank Laidlaw, Sandy Carmichael and Alastair McHarg. Between 1971 and 1976, Scotland lost just once at home, a narrow defeat to the All Blacks.

A giant of a man, both physically and figuratively, he formed a key partnership in the blue jersey with McHarg, winning 30 caps; in a Lions shirt, he was one of the world’s most ruthless competitors. Not only could he move but his outstanding handling skills resulted in eight tries on the Lions’ 1974 venture – including the brutal Battle of Boet Erasmus – a record for a forward. He played in eight Lions’ Tests between 1971 and 1977, playing a major part in the 1971 and 1974 victories. A string of injuries ended his career, but not before an infamous incident in a match between Glasgow and the North-Midlands, he was suspended for three months after getting into a fight with Allan Hardie, in which Brown chased Hardie, threw him to the ground and kicked him. Prior to this, Hardie had kneed Brown in the face and proceed to stamp on the open wound on Brown's brow after the initial attack went unnoticed by the referee. The suspension meant that he missed three internationals and was banned from training at any rugby club.

The hardest battle came two decades later, with the diagnosis of non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A battler to the end, he died in 2001, aged just 53.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

haste away

“How can there be a cherry without a stone?” John sang, letting the melody strengthen the words, memories of singing on the ship when they’d left harbor, of singing courting Mary with a nosegay of pink blossoms, of singing when his mother and grandam spun wool after the evening meal had been cleared, rising up with each note. The sand in front of his feet had been raked an hour earlier, each grain mimicking some perfection the Japans sought in the littlest things.

“How can there be a chicken without a bone?” he went on, John again and not Anjin, not barbarian or stinking dog, the slurs they’d thought him too stupid to learn.

They bathed overmuch and he’d never met a dog who wasn’t a canny beast, most loyal, a true companion.

He wasn’t offended.

“You have a fine voice,” Mariko-sama said. She’d come into the courtyard without his notice, her gait silent, her grace making her one with the air. She had the ease of water, the subtlety of shadow.

“I don’t deserve such praise,” he said. William Blunt, that great ruddy ox of a man, had sung them all half-way round the world, and young Hal Moody had lifted such a voice as would make a man weep and fall to his knees in prayer. Both had died during the Erasmus’s voyage. His own voice was full and deep, but of no particularly notable timbre, a baritone that might dip into bass, capable of carrying the tune but of no other talent.

“I’ve never heard a hatamoto sing,” she said.

“I beg pardon if I’ve brought dishonor to my lord Toranaga,” he said. It was so easy to be found in error. He consoled himself even the Queen’s most accomplished courtier could not do better and would likely have had his head lopped off much sooner, too prideful to admit any mistake.

“It is not condemnation I offer,” she said. “Among your people, this is common?”

“Yes. Man and woman, boy and girl, servant and lord. As you may surmise, we amuse ourselves with simple songs and the best musicians entertain the Queen. Many demonstrate their devotion in hymns offered to God’s glory,” he said.

“And what you were singing, that was a hymn?” she said. He’d sung in English, so she would not have understood the words. He smiled instead of laughing.

“No, it’s only an old song, from the countryside,” he said. “I learnt it as a child.”

“Will you tell me what the words are?” she asked.

“It’s a riddle song,” he said.

“A riddle?”

“Mayhap I’ve chosen the wrong word in Portuguese. It plays with words, some trickery…It asks, how can there be a cherry without a stone and the answer is when the cherry is in flower,” he said, taking his time and trying to think how she would hear what he said. Her gaze was steady on him but there was a slight furrow on her brow and she pursed her lips fleetingly, an unremarkable shift for any woman John could think of in England; for Mariko, it suggested she grappled with a tremendous conundrum, yet one that intrigued rather than distressed her. He shoved aside the sudden urge to kiss that sweet mouth, a desire unworthy of her though he could not scold himself overmuch for the impulse.

“Are all the answers similar?” she said.

“Yes,” he replied, recalling the lyrics, how he’d struggled as a boy to construe them. How the wind had taken them from his lips as the ship’s bow leaned into the waves’ crest. He’d been dreaming less of England but the dreams that came were more vivid. His life in the Japans seemed like the only real one except for moments when he was John Blackthorne of London, the taste of a roasted chestnut burning his tongue, the sharp cry of his son in his cradle, wanting his mother’s breast. That was the riddle now, what was real, where he belonged if he was not going back out onto the sea’s billow.

“They are about time, then. About how the past lurks and the future beckons. How we may be deceived by the present,” she said.

“I hadn’t thought of it so before,” he said.

“Another revelation for you,” she said, her tone very tranquil but still he heard the faint hint of mirth.

“You find me the greatest fool,” he said, shrugging, feeling the smooth weave of the robe he wore against his shoulders. He hadn’t had a garment made of such exquisite material before he’d been cast up on these shores. It was a riddle how he had come up and down in the world all at once, one that would make his head ache if he tried to solve it.

“That is not how I would put it, Anjin,” she said.

“A fool can be wise. Can speak truly when other men must hold their tongues or lie to save their necks,” he said.

“Not here,” she said. It was a warning, one he hadn’t needed.

“I hadn’t thought so. I haven’t seen much proof any lord would find a jest to their liking,” he said.

“You are the most curious man I’ve ever met,” she said. She dropped her eyes, focused not on some distant point as she withdrew within herself, but looked to her feet, peeping out from her silk skirts. It was a shy gesture, as if she had found herself coquetting within meaning to, younger than he’d ever believed possible.

“Do you sing, Mariko-sama?” he asked.

“Only to my son when he was small,” she said. She knew he’d seen the boy when they left, a stripling, soon to sprout his first beard. It had been years, then, since she had sung.

“I won’t ask you to sing for me,” John said. “But you may ask me. Or tell me to be quiet.”

“This is your household,” she said. “You are allowed more eccentricity within its walls.”

“I’ll bear that in mind,” he said.

“I play the koto. Not as beautifully as I should,” she said.

“I should like to hear you one day,” he replied, inclining his head, glancing at her to gauge her reaction. She accepted what he’d said, liked that he’d made the gesture. He could live a dozen lifetimes and still count himself barely cognizant of her mysteries.

“Perhaps. Perhaps when the cherries bloom again. You might sing your song then, with the petals falling,” she said, offering up the vision to him. She would be sitting nearby and the rosy petals would drift around her, only one daring to land on her black hair. Another springtime, the yearning he felt for her would be transformed into a longing that was like the tide’s need for the shore, his affection encompassing as the delicate fragrance of the flowering trees, around, drawn deep within, sustaining. He would sing and hear his voice as the Lord might, all dross cast away, time and Mariko’s eyes his crucible. He would sing and when he finished, she would smile in welcome.

He would take that one petal from her hair.

She would not play her koto for him.

He would not be disappointed.

#shogun 2024#john x mariko#john blackthorne#toda mariko#John POV#singing#romance#parents#cultural differences#pining#lost in translation#john blackthorne sings#decided against a sea shanty

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This link was if anything confirmed, when on 1 April 1534 William Marshall wrote to tell Thomas Cromwell that Erasmus had just completed a new work on the Creed and the Ten Commandments, dedicated to Anne Boleyn's father, Thomas, earl of Wiltshire. Marshall noted that he would have the text from the printers 'as soon as God sends me money', and would send two bound copies to Cromwell. 'I hope you like the translation,' he added, 'it cost me labour and money.' The following year, the prior of Haversfordwest, William Barlow, in whose appointment Anne Boleyn herself had had a direct hand, wrote to Cromwell complaining about the abuse he had received at the hands of 'Antichrist and his confederate adherents' in attempting to 'sincerely preach the Gospel of Christ'. 'Antichrist' was personified in this particular instance by the aged and ailing Bishop of St David's, Richard Rawlins, whose agents confiscated from Barlow 'an English testament, the exposition of the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth chapters of Matthew, the Ten Commandments, and the Epistle of St John, with clamorous exclamations against heretics—as if to have the Testament in English were horrible heresy.'

The Reformation of the Decalogue, Dr Jonathan Willis

8 notes

·

View notes