#joan leigh fermor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

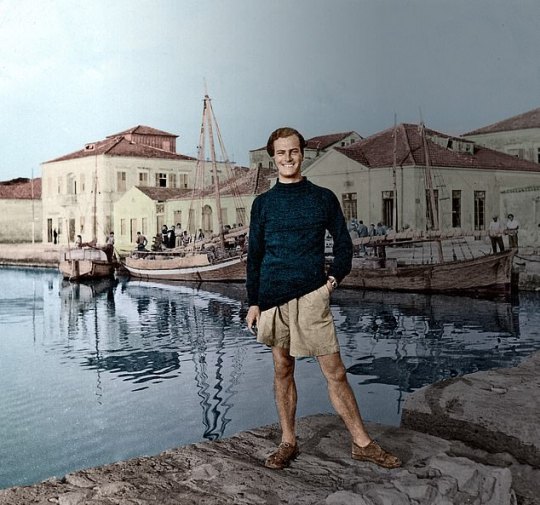

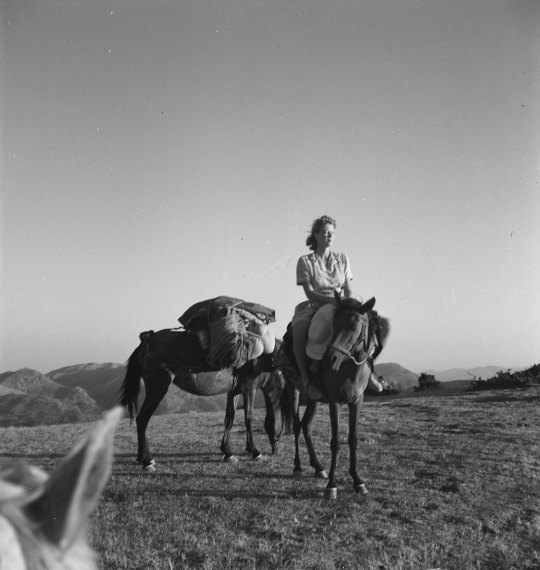

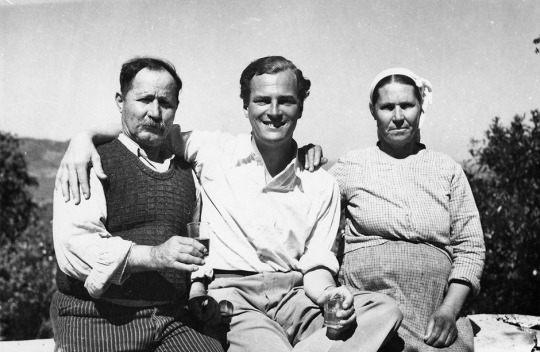

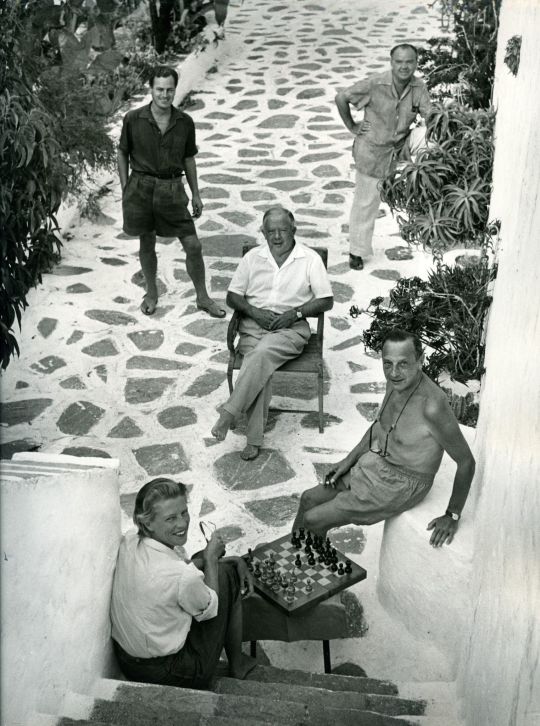

Geroliménas, Máni, Peloponnese, Greece, 1940's - by Joan Leigh Fermor (1912 - 2003), English

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Pimpernel of the Hellenes’, ‘Major Paddy’, ‘Enchanted maniac’: Will the real Paddy Leigh Fermor please stand up?

Paradox reconciles all contradictions. - Patrick Leigh Fermor

So one evening I was baby sitting my nephews and nieces here in our family chalet in Verbier, high up in the Swiss Alps. It was my turn to baby sit as the rest of my family enjoyed the fantastic classical music concerts and events showcased at the two week long Verbier 30th Festival. The little scamps had gone to bed and my father and I watched an old British war movie on DVD, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957). It was filmed by the legendary team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on the 1950 book ‘Ill Met by Moonlight: The Abduction of General Kreipe’ by W. Stanley Moss.

I’ve seen the film a couple of times before, but until now never really paid attention to where the title came from. My father said it was from Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream’ And so it was. In the play, Oberon, the king of the fairies and the Queen are having a fairly bitter drawn-out fight over custody of a changeling Indian child, and this is how the pissed off king greets the queen when they run into each other, “Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania”. Oberon is basically saying "Oh Lord, it's you..." and Titania's response is basically a flippant middle finger. One of the best modern reasons to read Shakespeare: to throw playful erudite shade at others.

Anyway, the historical background of the film is the German invasion of Crete in May 1941. After an intense ten-day battle, Allied troops were driven back across the island, and many were evacuated from beaches along the southern coast. Some Cretans and British officers took to the mountains to organise resistance against the occupying forces. The German occupation that followed was especially brutal. Dreadful reprisals followed every act of resistance. The German commander, General Müller, insisted on taking 50 Cretan lives for every German soldier killed; he became known as ‘The Butcher of Crete’.

As a Classicist side note, there had been a close association between Britain and Crete since the early 20th century, when archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans had uncovered the sensational remains of a Minoan palace at Knossos. The headquarters of the British archaeological school in Crete was a large villa alongside the site, known as Villa Ariadne. Several archaeologists, who knew the island and its people well, went underground after the German occupation to aid the Cretan resistance. Continuing in this tradition, scholar and travel-writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, who had got to know Greece in the 1930s, joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

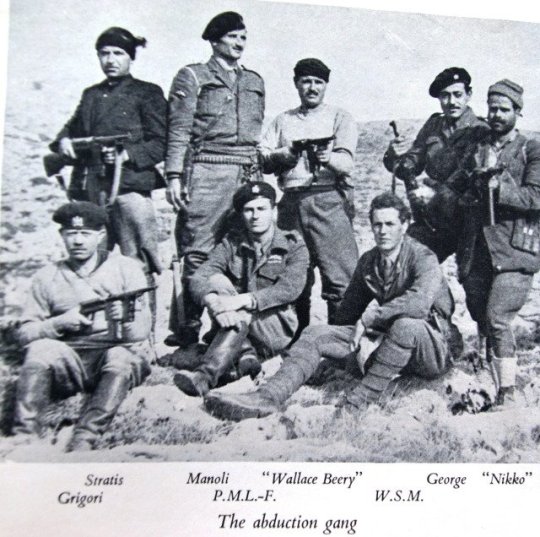

During the German occupation, Major Paddy Leigh Fermor travelled to Crete three times to help organise local resistance against the hated German occupation. On the third occasion, in February 1944, he was parachuted in with a specific mission to kidnap German commander General Müller, to boost morale on Crete along with his erstwhile SOE comrade Capt. W. Stanley Moss MC (aka Billy Moss) of the Coldstream Guards. However, just after they parachute in, General Müller was replaced by General Heinrich Kreipe, who transferred from the Russian Front. Thinking that capturing one general was as good as another, Fermor merrily go ahead with the daring kidnap operation.

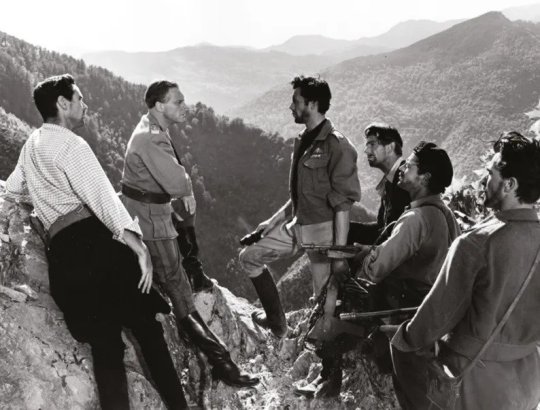

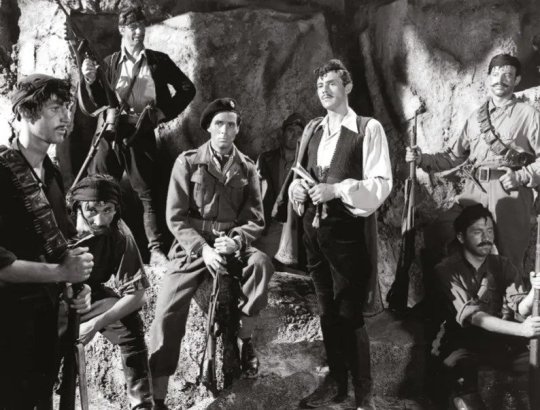

It’s at this point that the narrative of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ (1957) picks up. Dirk Bogarde plays Paddy Leigh Fermor, David Oxley plays Moss, and Marius Goring plays the taciturn German paratroop general. Blink and you’ll miss the late great Christopher Lee making a cameo appearance as a German officer in the dentist’s room scene.

The film naturally takes some liberty with the facts but it’s a cracking yarn of high adventure and drama. Xan Fielding, a close friend of Leigh Fermor from the SOE in Cairo, was taken on as technical adviser. The fact the film was shot in in the Alpes-Maritimes in France and Italy, and on the Côte d'Azur in France, far away from the craggy valleys and mountains of Crete itself. The director Michael Powell spent some time walking in Crete to get to know the island, but decided that, with the confused and volatile state of Greek politics, it was not suitable to film there.

Looking back years after he had directed it Powell didn’t think much of his own film. By contrast, Paddy Leigh Fermor, who was on set throughout the film shoot, was very happy with Bogarde’s portrayal of him with Byronic glamour. Watching the movie again ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ remains a classic and stands out from many British war films of the 1950s because of its realism. The British SOE men and the Cretan guerrillas look absolutely right for their parts. It is dramatic and full of suspense while filled with much boyish humour.

I was disappointed with one notable omission in the film that did happen in real life. According to Patrick Leigh Fermor, at dawn one day during the journey across the mountains, General Kreipe was looking at the mist rising from Mount Ida and began to recite, in Latin, the opening lines of Horace’s ninth ode:

Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte nec iam sustineant onus silvae laborantes geluque flumina constiterint acuto?

Behold yon Mountains hoary height, Made higher with new Mounts of Snow; Again behold the Winters weight Oppress the lab’ring Woods below: And Streams, with Icy fetters bound, Benum’d and crampt to solid Ground

(John Dryden 1685)

Leigh Fermor picked up on the General, and recited the remaining stanzas of the Ode. ‘Ach so, Herr Major,’ said Kreipe when Leigh Fermor had finished. Both men were amazed to realise they shared a classical education and a love of ancient Latin poetry.

Leigh Fermor later wrote that it was as though the war had ceased to exist for a moment, as ‘We had both drunk from the same fountains before.’ It brought captor and captive together with a strange bond. The scene was not reproduced in the film, as Powell and Pressburger probably thought it would make the men sound too academic for a popular cinema audience.

Leigh Fermor and Kreipe met again in the early 1970s, on a Greek television show, and got on famously together. The General said Leigh Fermor had treated him chivalrously as a captive. They remained friends until Kreipe’s death.

After sharing a late night drink with my father after the film, I began to muse on the figure of Paddy Leigh Fermor, a family friend and someone I met along with his wife, Joan, as a little girl. My grandparents, and especially my grandmother, knew Paddy briefly from their days during and after the Second World War.

My father shared a few stories about him when he and my mother visited his beautiful home in Greece, where even at his advanced age he remained the most generous of hosts and the most outrageous flirt.

One of my memories was getting into his battered old Peugeot in the drive way and trying to drive it when my feet could barely touch the pedals. It wouldn’t have mattered in any case as the brakes didn’t work as he cheerfully said later as we careened around a dirt road to go around the mountains for a drive.

Many years later in April 2022, I tried to visit the home of the late Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor - a sort of pristine shrine to their memory that one can also stay in any of the rooms as a vacation rental - in the coastal fishing village of Kadarmyli in the Peloponnese, as part of a hiking and mountaineering sojourn around Greece with ex-Army friends. We couldn’t stay there as it was already rented out to other guests, and so we stayed higher up the mountain in a villa, but we swam in front of the Fermor’s home which was on the water’s edge.

You could never put your finger on Paddy Leigh Fermor. He hid behind his gift for telling yarns, and pulling Ancient Greek verses out of the thin air, as well as boisterously singing local Greek songs with a drink in his hand.

Even after his death in 2011, the question keeps nagging as to who was Paddy Leigh Fermor?

The Dirk Bogarde film too seems to ask, who exactly is the ‘real’ Patrick Leigh Fermor - or the real anyone? Taking its title from a Shakespearian play concerned with dreams and disguises, magic and power, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ is all about questions of identity.

Under the film credits, we see Dirk Bogarde in uniform; then, unexpectedly, we see him in the flamboyant outfit of a Cretan hill-bandit. A title informs us that Major Leigh Fermor was also known by the Greek code-name “Philidem.” In other words, there are two of him (at least), and on one level the adventure the film is about to unfold reflects a conflict in his personality. It’s a conflict shared, unknowingly, by his Nazi opposite number, the fierce, arrogant General Kreipe (an unlikely “proud Titania,” but it’s true that he “with a monster is in love” – the monster of Nazism). Kreipe’s human side is so rigorously repressed by the demands of war and “glory” that he is genuinely unaware of it; ironically, this humanness, which constitutes the true manhood of this Teuton warrior, is revealed by a boy (equivalent to Shakespeare’s Indian Prince?) - who, in turn, is the most grown up person in the movie.

If “Philidem” appears under the credits, caped and open-shirted, a romantic dream-figure out of an operetta or a storybook, he is first seen in the film proper as a coarser, more down-to-earth version of the same thing – an ordinary Cretan peasant in a shabby suit, waiting for a bus. When he makes contact with the Resistance, his personality fragments further.

To some, he is the mystical Philidem, Pimpernel of the Hellenes and righter of wrongs. To others he is “Major Paddy,” the happy-go-lucky Englishman of popular movie myth conducting war as if it were a branch of amateur theatricals, a gentleman adventurer relying on breeding to get him through and making fun of the whole business. To Bill Moss (David Oxley), the newly arrived junior officer sent to assist him, he is the cool, fast-thinking professional soldier. And to himself? In his quietly passionate defence of Cretan life and culture, he seems someone else again: a scholar and aesthete outraged by the barbarism and folly of war, and by the moronic arrogance shown by his captive toward the Cretan people.

Whatever his persona, Leigh Fermor is a chameleon who never seems to change very radically in himself. Perhaps because he has this quality of seeming all things to all men – and being those things - he remains unfazed by the monolithic might of the German military machine. Fluent in Greek, he can also speak German like a German and is easily able to assume another disguise, that of a faceless Nazi officer. Although he and Moss make fun of themselves - “If only I had a monocle!” muses Moss when Leigh Fermor tells him he “looks like an Englishman dressed like a German, leaning against the Ritz bar” - they are able to effect the kidnapping with an ease that seems appropriately Puckish. General Kreipe is ignominiously thrust onto the floor of his own limousine, gagged, and sat upon by a couple of the peasants he so despises. Kreipe’s rage is compounded by his firm conviction that he has been snatched by “amateurs” - a belief Leigh Fermor and Moss slyly make no objection to, knowing how it will gnaw at his already shaky Master Race self-confidence.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, aka Major Paddy, aka Philidem, in the film’s closing moments, is far from being self-assured intellectual or dashing amateur adventurer or legendary outlaw of the hills. He’s just a tired man who wants to go home and rest up. “How do you feel?” asks Moss. “Flat” is the reply. “You look flat!” says Moss. “I know how I’d like to look …” murmurs Leigh-Fermor wistfully. Moss knows what he’s going to say, and joins in the litany: “Like an Englishman dressed like an Englishman – and leaning against the Ritz bar!” It’s easy to imagine them ordering drinks at that renowned watering-hole with all the suavity required by this little fantasy.

Still, the film’s last images of Crete receding in the distance, until all we can see is the sea, suggests that maybe Major Paddy’s heart is really back in those hills in the “fair and fertile” land that has become as much a Powellian landscape of the mind for us as the studio-built Himalayan convent of ‘Black Narcissus’ or the monochrome Heaven of ‘A Matter of Life and Death’. And, as the film POV closing shots departs both Crete and this film, I began to think that being “dressed like an Englishman and leaning against the Ritz bar” would, for Patrick Leigh Fermor constitute yet another disguise. After all, he said he was of Irish aristocratic stock.

Traveller and writer Paddy Leigh Fermor is best known for two events. He’s known for leading the commando group in occupied Crete to kidnap General Kreipe. But he is also known for the boy who, at a mere 18 years old, set off with little money and a lot of nerve in 1933 to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was, in the words of one of his obituaries, a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene. Self-reliance and derring-do were lessons learnt from the cradle. When Fermor’s geologist father was posted to India, he and his wife left the infant with family in Northamptonshire and did not return until his fourth birthday. In retrospect, he took great delight in being sent to a school for difficult children and getting himself expelled from the King’s School, Canterbury, when he was caught holding hands with a greengrocer’s daughter eight years his senior. His school report infamously judged him ‘a dangerous mix of sophistication and recklessness’.

Sharing a flat in Shepherd’s Market, one of Mayfair’s seedier corners, Leigh Fermor schooled himself in literature, history, Latin and Greek.

He honed his character with the company of extraordinary people and the words of great writers - he had a prodigious memory for prose as well as poetry. He befriended literary lions such as Sacheverell Sitwell, Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford. His travels began aged ‘eighteen-and-three-quarters’ when he rejected Sandhurst Royal Military College in order to walk the length of Europe from Hook of Holland to Constantinople. He took with him Horace’s Odes and the Oxford Book of Verse though Leigh Fermor could recite Shakespeare soliloquies, Marlowe speeches, Keats’s Odes and as he modestly put it ‘the usual pieces of Tennyson, Browning and Coleridge’ from memory.

Leigh Fermor was then a self-made man in the most literal sense.

Setting off from England in 1933, Fermor resolved to traverse Europe living like a hermit; sleeping in bars and begging for food. But his manly charms and boyish good looks found him being passed like a favourite godson from Schloss to palace by European nobility and he developed a lifelong penchant for aristocratic company. I his own words, ‘In Hungary, I borrowed a horse, then plunged into Transylvania; from Romania on into Bulgaria’. Having reached Constantinople in January 1935, Fermor continued to explore Greece where he fought on the royalist side in Macedonia quelling a republican revolution. In Athens Leigh Fermor met Balasha Cantacuzene, a Romanian countess with whom he fell in love. They were living together in a Moldovan castle when World War Two was declared.

Fluent in Greek, Leigh Fermor was posted as a liaison officer in Albania. Recruited as a Special Operations Executive (SOE), he was shipped from Cairo to German-occupied Crete where he lived disguised as a shepherd in the mountains for two years. On his third expedition to Crete in 1944, Leigh Fermor was parachuted alone onto the island and made connections in the Cretan resistance movement. While waiting for his compatriot Captain Bill Stanley Moss to land by water from Cairo, Leigh Fermor hatched a plot to kidnap German Commander General Heinrich Krieple. He liaised comfortably with Cretan partisans and bandits to pull off one of the war’s greatest coups de théâtre.

Disguised as German soldiers, Leigh Fermor and Moss stopped Krieple’s car at an improvised check point en route back to Nazi HQ in Knossos. Abandoning the General’s car after a two-hour drive, Leigh Fermor left a note indicating that the kidnappers were British so that there wouldn’t be reprisals against Cretan nationals. When the abduction of the unpopular commander was discovered, a German officer in Heraklion allegedly said ‘well, gentlemen, I think this calls for champagne’. It turns out that General Kreipe was despised by his own soldiers because, amongst other things, he objected to the stopping of his own vehicle for checking in compliance with his commands concerning approved travel orders. It’s why for instance the German troops, both in the film and in real life, dare not stop the General’s car as it drove through the check points at Heraklion.

Krieple was evacuated and taken to Cairo and Leigh Fermor entered the annals of World War Two’s most devil-may-care heroes. With characteristic panache, when he was demobbed Leigh Fermor moved into an attic room at the Ritz paying half a guinea a night. But his first travel book, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’, was not about the European odyssey or the Cretan escapades and centred on Leigh Fermor’s adventures in the Carribbean. Published in 1950, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’ was an inspiration for Ian Fleming’s second James Bond novel ‘Live and Let Die’ (1954).

As a host and house guest, Paddy Leigh Fermor was much sought-after. At one of his parties in Cairo, he counted nine crowned heads. He was a confirmed two-gin-and-tonics before lunch man and smoked eighty to 100 cigarettes a day. His party pieces included singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ in Hindustani and reciting ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ backwards. In Cyprus while staying with Laurence Durrell, Leigh Fermor apparently stunned crowds in Bella Pais into silence by singing folk songs in perfect Cretan dialect. As Durrell wrote in ‘Bitter Lemons’ (1957), ‘it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes’.

He struck up a partiuclar friendship with the famous Mitford sisters, especially Deborah Mitford, later ‘Debo’, the Duchess of Devonshire. It was at the Devonshires’ Irish estate Lismore Castle that ‘Darling Debo’ and ‘Darling Pad’ met and began to correspond. A characteristic letter from the Duchess in 1962 reads ‘The dear old President (JFK) phoned the other day. First question was ‘Who’ve you got with you, Paddy?” He’s got you on the brain’ to which Fermor replies of a broken wrist ‘Balinese dancing’s out, for a start; so, should I ever succeed to a throne, is holding an orb. The other drawbacks will surface with time’.

After the war he travelled widely but was always drawn back to Greece. He built a house on the Mani peninsula - which had been, significantly, the only part of Magna Graecia to resist Ottoman colonisation since the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Before his death in 2011 at the age of 96, he wrote some of the most acclaimed travel books of the 20th century.

His books contain some of the finest prose writing of the past century and disprove Wilde's maxim that "it is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating".

Charm, self-taught knowledge and enthusiasm made up for the lack of a university degree or a private income. His teenage walk across Europe and subsequent romantic sojourn in Baleni, Romania, with Princess Balasha Cantacuzene are proof enough of that. But the difficulty of capturing such an unconventional and glamorous life is made harder by the certainty that Fermor was an unreliable narrator.

He was also an infuriatingly slow writer. Driven by a life-long passion for words yet hampered by anxiety about his abilities, Leigh Fermor published eight books over 41 years.

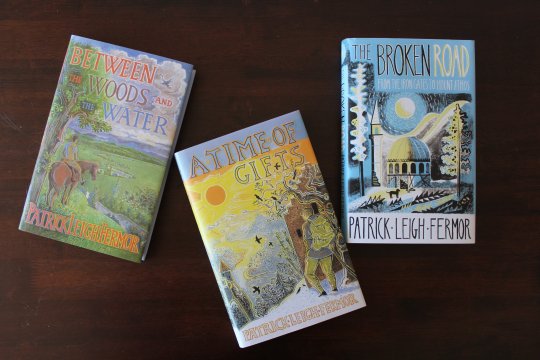

‘The Traveller's Tree’ describes his postwar journey through the Caribbean; ‘Mani‘ and ‘Roumeli’ (1958 and 1966) draw on his experiences in Greece, where he would live for much of the latter part of his life. But it is the books that came out of his trans-Europe walk that reveal both the brilliance and the flaws. ‘A Time of Gifts’ was published in 1977, 44 years after he set out on the journey. ‘Between the Woods and the Water’ appeared nine years later. Both describe a world of privilege and poverty, communism and the rising tide of Nazism, and end with the unequivocal words, "To be continued". Yet the third volume hung like an albatross around the author's neck. As the years passed, Fermor found it impossible to shape the last part of his story in the way he wanted.

Leigh Fermor was that rarest of men: a man determined to live on his own terms, if not his own means, and who mostly - and mostly magnificently - succeeded. Always popping off on a journey when he should have been writing about the last one, always ready to party, he was forever chasing beautiful, fascinating or powerful women, even when with his wife, Joan Raynor. She was the great facilitator who funded his passion for travel and writing, as well as women, from her trust fund. His love affairs were discreet but legendary.

Leigh Fermor was happiest among the rogues. Over a lifetime on the road, he sought them, and in turn they responded to his charm, nose for adventure, and his famous wit. He was a keenly-anticipated dinner guest - once outshining Richard Burton at a London society soirée, who he cut-off midway through a recital of ‘Hamlet’. As Richard Burton stormed out, the pleading society hostess said, “But Paddy’s a war hero!” to which Burton grouchily replied, “I don’t give a damn who he is!”

His partnership with and then marriage to Joan Raynor was an open relationship, at least on Leigh Fermor’s side. Paddy saw in Joan his kindred spirit. Like him, she spent much of her youth travelling to where she pleased; largely in France, where the photographer and literary critic Cyril Connolly became besotted by her. Joan was the daughter of Sir Bolton and Lady Eyres Monsell of Dumbleton Hall, Worcestershire. She was not only stunningly pretty but also 'a beautiful ideal, with the perfect bathing dress, the most lovely face, the most elaborate evening dress', as the Eton educated Connolly described her. Joan also stood out from the upper-class beauties of her day in that she supplemented her mean rich father's allowance by earning her living as a decent photographer.

In 1946, she met Leigh Fermor in Athens, while he was deputy director of the British Institute. Joan met him at a time when he was then in a relationship with a French woman called Denise, who was pregnant with his child, which she aborted. The pair would travel to the Caribbean together under the invitation of Greek photographer Costas, falling madly in love.

She was the only woman that - after decades of sexual scandals - matched his own erratic behaviour. Stories of how they dined fully-clothed in the Mediterranean, dragging a table into the sea, as well as their myriad cats and olive groves, paint a restless couple, who, when not out articulating the peoples of their adopted homeland, kept themselves very busy.

The attraction between Paddy and Joan was instant. So many love affairs that Paddy indulged in seemed about as brief as the flame from a burning envelope and you expected this one with Joan to be too. But somehow, miraculously, it lasts.

The two were apart a great deal, but in their case, absence did make the heart grow fonder. While Paddy was staying in a monastery in Normandy, supposed to be thinking monk-like thoughts that he would eventually put into his masterpiece A Time To Keep Silence, he was also writing sexy letters to Joan: 'At this distance you seem about as nearly perfect a human being as can be, my darling little wretch, so it's about time I was brought to my senses.' And: 'Don't run away with anyone or I'll come and cut your bloody throat.'

She tantalised him with descriptions of Cyril Connolly making passes at her; but she, like Denise, sounded a rather desperate note when she wrote: 'I got the curse so late this month I began to hope I was having a baby and that you would have to make it a legitimate little Fermor. All hopes ruined this morning.'

Fiercely independent - a trait that must have enamoured Paddy - they were best imagined as two pillars of a Greek temple, beside one-another but capable of holding up the roof of the world that they had built for themselves through the lens of ancient history and Hellenic culture. Indeed, it was said that they had a special ‘pact of liberty’. It is this unconquerable aura that led poet laureate John Betjeman to declare his love for her (he called her ‘Dotty’ and remarked that her eyes were as large as tennis balls). For Cyril Connolly, the photographer she shadowed, and with whom she had a scandalised affair during her first marriage, she was a “lovely boy-girl” and Laurence Durrell named her the ‘Corn Goddess’ because of her slender figure and short hair. But of all of these worthy candidates, it was the warrior-poet Patrick Leigh Fermor who finally won her heart.

To Joan, who described herself as a ‘lifelong loner’ in her diaries, her companionship with the uncomplicated Paddy was a relief. They had no children, nor did they want any - or so Paddy claimed. But those who knew Joan suspected she did want children but it never came to pass; and so she became a devoted aunt or dotted on other friends’ children. For both of them their dozens of cats gave them the next best thing to paternal satisfaction. Still, her morbid fascination with photographing cemeteries painted a much darker side.

Joan Raynor’s inheritance subsidised his peripatetic life at least until the enormous success of ‘A Time of Gifts’ in the late 1970s, which in turn created a new market for his previous volumes about Greece, ‘Mani’ and ‘Roumeli’.

With Joan’s tacit consent, Paddy enjoyed amorous flings, discrete sexual affairs with high society women and sampled the low delights of the brothel. This activity rarely made it into his private letters, but the exceptions could be piquant. Writing in 1958 from Cameroon, where he was on the set of a John Huston movie, he told a (male) friend: “ Errol Flynn and I . . . sally forth into dark lanes of the town together on guilty excursions that remind me rather of old Greek days with you.” In a 1961 letter to the film director John Huston’s wife, Ricki, with whom Leigh Fermor had been having sex with (and would die in a car crash in 1969). “I say,” the passage begins, “what gloomy tidings about the CRABS! Could it be me?” Riffing on pubic lice and their crafty ways, he conjectures that, during a recent romp with an “old pal” in Paris, a force “must have landed” on him “and then lain up, seeing me merely as a stepping stone or a springboard to better things” - to Mrs. Huston, that is. As comic apologies for venereal infection go, the passage is surely a classic.

Like most high flying lives, it was far from blameless. Wounded women were littered in his wake. Some British visitors to Athens were less than impressed by this Englishman who posed as “more Greek than the Greeks”.

Some Greeks shared their disdain. Revisionist historians criticised his role in wartime Crete, and warned their fellow Hellenes that for all his fluency and charm, Leigh Fermor was no latter day Byron. His unoccupied car was blown up outside his Mani house, probably by members of the Greek Communist Party which he had vocally opposed. The accidental fatal shooting of a partisan in Crete led to a long blood feud which made it difficult for Leigh Fermor to re-enter the island until the 1970s, and possibly explains why he chose to settle in the Peloponnese rather than among the hills and harbours of his dreams.

His own books had already eclipsed those incidents, not only among readers of English but also in Greece, where in 2007 the government of his adopted land made him a Commander of the Order of the Phoenix for services to literature.

Travel writers such as the great Jan Morris have described Leigh Fermor as the master of their trade and its greatest exponent in the 20th century.

When ‘A Time of Gifts’ was published in 1977, Frederick Raphael wrote: “One feels he could not cross Oxford Street in less than two volumes; but then what volumes they would be!”

They are not for everyone. Leigh Fermor wrote that written English is a language whose Latinates need pegging down with simple Anglo-Saxonisms, and some feel that he personally could have made more and better use of the mallet. His exuberance is either captivating or florid. It is certainly unique among English prose styles.

Artemis Cooper, his patient and careful biographer wrote that “Paddy had found a way of writing that could deploy a lifetime’s reading and experience, while never losing sight of his ebullient, well-meaning and occasionally clumsy 18-year-old self … this was a wonderful way of disarming his readers, who would then be willing to follow him into the wildest fantasies and digressions”.

Those fantasies and digressions took decades to express. ‘A Time of Gifts’ had arguably been 40 years in the making when it was published in 1977. Its sequel, ‘Between the Woods and the Water’, did not appear until 1986. The third and final volume has been awaited ever since. Following Leigh Fermor’s death, a foot-high manuscript was apparently found on his desk.

Once he knuckled down to it, Leigh Fermor loved playing around with words. He was one of our greatest stylists and he was devoted to producing un-improvable books. But writing did not come easily to him, at least partly because it was something of a distraction from the main event, which was living an un-improvable life of unrepentant gaiety and fun.

For forty odd years, a legion of friends and admirers would beat a path to Paddy and Joan’s door. Artists, poets, royalty and writers came, all taking inspiration from their erudite hosts. A visit was an act of communion, a sharing of ideas and stories.

Leigh Fermor influenced a generation of British travel writers, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane, Rory Stewart, and William Dalrymple. Indeed when Bruce Chatwin died, it was Paddy who scattered Chatwin’s ashes near a church in the mountains in Kardamyli.

When I was there in April 2022, I went to that same church to pay my respects.

But some of Paddy’s life energy was sucked out of him when Joan died in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. It was related that Joan said to her friend Olivia Stewart, who was visiting: 'I really would like to die but who'd look after Paddy?' Olivia said that she would. A few minutes later, Joan fell, hit her head - and died instantly of a brain haemorrhage. Joan had often quoted Rilke: 'The good marriage is one in which each appoints the other as guardian of his solitude.' Now Paddy Leigh Fermor was all alone.

Leigh Fermor was knighted in 2004, the day of his birthday which he delighted in like a giggling schoolboy. But he missed Joan terribly.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to bid goodbye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife, Joan, in Dumbleton, Gloucestershire. He stayed on at Kardamyli until the 9th June 2011, when he left Greece for the last time. He died in England the following day, 10th June 2011, aged 96. It was reported that he had dined in full black tie on the evening of his death. Paddy had style even unto the end.

A Guard of Honour was formed by the Intelligence Corps and a bugler from his former regiment, the Irish Guards, delivered the ‘Last Post’ at Paddy’s funeral. As had been his wish, he was buried beside Joan. On his gravestone in Dumbleton cemetery is an inscription in Greek, a quote from Constantine Cavafy: “In addition, he was that best of all things, Hellenic.”

Although Joan had passed away at the age of ninety-one, after suffering a fall in the Mani. Her body was repatriated to Dumbleton, the place of her birth - ironic that her dream was to be as far as she could possibly go from the rolling humdrum Worcestershire hills. But perhaps she intended to return all along. When Paddy was buried beside her it seemed that the ‘pact of liberty’ that these two lonely souls had forged themselves could be tested in the great elsewhere. Joan was more than his muse (as many of her obituaries were at pains to declare) but his greatest adventure.

To come around full circle from the movie ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957) that I saw that night in Verbier, my father told me that rather poignantly, General Kreipe, the German commander Leigh Fermor had captured - once an enemy, and later a friend - left behind notes and photographs from across his life. On one of those notes, it was discovered, the following was scribbled from a brief visit to Greece: “Somewhere, amidst all the disarray, was the story of Joan and Paddy, and” it concluded, “…of their lives together.”

His life with Joan and all that she meant to him was one part of the mosaic of who Paddy Leigh Fermor was. But it’s incomplete.

Paddy didn’t like the idea of a biography, and neither did Joan when she was alive. But friends had persuaded them that unless Paddy appointed someone to write his life, he might find himself the subject of a book whether he liked it or not. In Artemis Cooper they couldn’t have chosen a better writer to chronicle Paddy’s life as a man of action and letters. Cooper, was the daughter of another accomplished diplomat and historian, John Julius Norwich, and grand-daughter of Duff and Diana Cooper. As the wife of the historian Antony Beevor, she became a trusted friend of the Leigh Fermors. Cooper was too good of a historian to let her friendship lead her astray from being a faithful but serious biographer. Knowing this, she was told she could go ahead, but she had to promise not to publish anything until after they were both dead.

Paddy did not like being interviewed, and would keep her questions at bay with a torrent of dazzling conversation. He was the master at deflecting discussions away from himself.

He was also very unwilling to let Cooper see many of his papers, though the refusal always couched in excuses. ‘Oh dear, the Diary…’ It was the only surviving one from his great walk across Europe, and I was aching to read it. ‘Well it’s in constant use, you see, as I plug away at Vol III,’ he would say. Or, ‘My mother’s letters? Ah yes, why not. But it’s too awful, I simply cannot remember where they’ve got to…’ It was quite obvious that he and Joan, while being unfailingly generous, welcoming and hospitable, were determined to reveal as little as possible of their private lives.

While they were more than happy to talk about books, travels, friends, Crete, Greece, the war, anything - they would not tell her any more than they would have told the average journalist. But she persisted and got closer than most. He showed particularly gallantry in not talking about his romantic entanglements. But she soon twigged that anytime he described a woman as ‘an old pal’ it was a sure bet that he had an affair with her.

Intriguingly, Paddy liked to claim he was descended from Counts of the Holy Roman Empire, who came to Austria from Sligo. Paddy could recite ‘The Dead at Clomacnoise’ (in translation) and perhaps did so during a handful of flying visits to Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s, partying hard at Luggala House or Lismore Castle, or making friends with Patrick Kavanagh and Sean O’Faolain in Dublin pubs. He once provoked a massive brawl at the Kildare Hunt Ball, and was rescued from a true pounding by Ricki Huston, a beautiful Italian-American dancer, John Huston’s fourth wife and Paddy’s lover not long afterwards.

And yet, a note of caution about Paddy’s Irish roots is sounded by his biographer, Artemis Cooper, who also co-edited ‘The Broken Road’, the final, posthumously published instalment of the trilogy. “I’m not a great believer in his Irish roots,” she said of Leigh Fermor in an interview, “His mother, who was a compulsive fantasist, liked to think that her family was related to the Viscount Taaffes, of Ballymote. Her father was apparently born in County Cork. But she was never what you might call a reliable witness. She was an extraordinary person, though. Imaginative, impulsive, impossible - just the way the Irish are supposed to be, come to think of it. She was also one of those sad women, who grew up at the turn of the last century, who never found an outlet for their talents and energies, nor the right man, come to that. All she had was Paddy, and she didn’t get much of him.”

And I think that’s the point, no one really got much of Paddy Leigh Fermor even as he only gave a crumb of himself to others but still most felt grateful that it was enough to fill one’s belly and still feel overfed by him.

Paddy never tried to get to the bottom of his Irish ancestry, afraid, no doubt, of disturbing the bloom that had grown on history and his past, a recurring trait. “His memory was extraordinary,” Artemis Cooper noted, “but it lay dangerously close to his imagination and it was a very porous border.”

Within the Greek imagination many Greeks saw in Paddy Leigh Fermor as the second coming of Lord Byron. It’s not a bad comparison.

Lord Byron claimed that swimming the Hellespont was his greatest achievement. 174 years or so later, another English writer, Patrick Leigh Fermor - also, like Byron, revered by many Greeks for his part in a war of liberation - repeated the feat. Leigh Fermor, however, was 69 when he did it and continued to do it into his 80s. Byron was a mere 22 years old lad. The Hellespont swim, with its mix of literature, adventure, travel, bravery, eccentricity and romance, is an apt metaphor for Leigh Fermor’s life. Paddy Leigh Fermor was the Byron of his time. Both men had an idealised vision of Greece, were scholars and men of action, could endure harsh conditions, fought for Greek freedom, were recklessly courageous, liked to dress up and displayed a panache that impressed their Greek comrades. Like a good magician it was also a way to misdirect and conceal one’s true self.

What or who was the true Paddy Leigh Fermor?

Like Byron, Leigh Fermor appeared as a charismatic and assured figure. He was a sightseer, consuming travel, culture, and history for pleasure. He was an aristocrat moving in the social circles of his time. He was a gifted amateur scholar, speculating on literary and historical sources. Leigh Fermor, Byron’s own identity, is subject to textual distortion; it emerges from a piece of occasional prose in his books and is shaped by the claims of correspondence on a peculiarly fluid consciousness.

There is no hard and fast distinction to be drawn here between real and imagined, only a continuity of relative fictions that lie between memory and imagination as his biographer asserted. If there is a will to assert identity here, to disentangle fact and fiction, to give things as they really are and nail down the real Leigh Fermor then it is somewhere between the two. This is where we will find Paddy.

For many his death marked the passing of an extraordinary man: soldier, writer, adventurer, a charmer, a gallant romantic. As a writer he discovered a knack for drawing people out and for stringing history, language, and observation into narrative, and his timing was perfect. Paddy often indulged in florid displays of classical erudition. His learned digressions and serpentine style, his mannered mandarin gestures, even baroque prose, which Lawrence Durrell called truffled and dense with plumage, were influenced by the work of Charles Doughty and T.E. Lawrence. But one can’t compare him. I agree with the acclaimed writer Colin Thurbon who said, “There is, in the end, nobody like him. A famous raconteur and polymath. Generous, life-loving and good-hearted to a fault. Enormously good company, but touched by well-camouflaged insecurities. I would rank him very highly. ‘The finest travel writer of his generation’ is a fair assessment.”

As a child I didn’t really know who Paddy Leigh Fermor was other than this very cheerful and charismatic old man was kind, attentive, and took a boyish delight in everything you were doing. Only later on in adulthood was it clear to that Paddy was not only among the outstanding writers of his time but one of its most remarkable characters, a perfect hybrid of the man of action and the man of letters. Equally comfortable with princes and peasants, in caves or châteaux, he had amassed an enviable rich experience of places and people. “Quite the most enchanting maniac I’ve ever met,” pronounced Lawrence Durrell, and nearly everyone who’d crossed paths with him had, it seemed, come away similarly dazzled.

I am equally dazzled - more smitten in retrospect - for alas they don’t make men like Paddy any more. But every time I dip back into his books I think I discover a little bit more of who Paddy Leigh Fermor was because I find him some where between my memory and my imagination.

#essay#paddy leigh fermor#leigh fermor#joan raynor#joan leigh fermor#greece#crete#second world war#SOE#war#british army#history#general kreipe#stanley moss#literature#author#writer#travel#explorer#wanderlust#travel writing#europe#mani#peloponnese#kardamlyi#lord byron#ill met by moonmight#film#movie#personal

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Leigh Fermor. Geroliménas, Máni, Peloponnese, Greece, 1940’s.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geroliménas, Máni, Peloponnese, Greece, 1940’s - Photo by Joan Leigh Fermor

#1940s#greece#Vintage Photo#old photo#sealed in time#historical photo#history photo#photos#history#photography#black and white photography#vintage photography#black and white#black and white photo#history lovers#history in pictures#antique photo#timeless photo

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

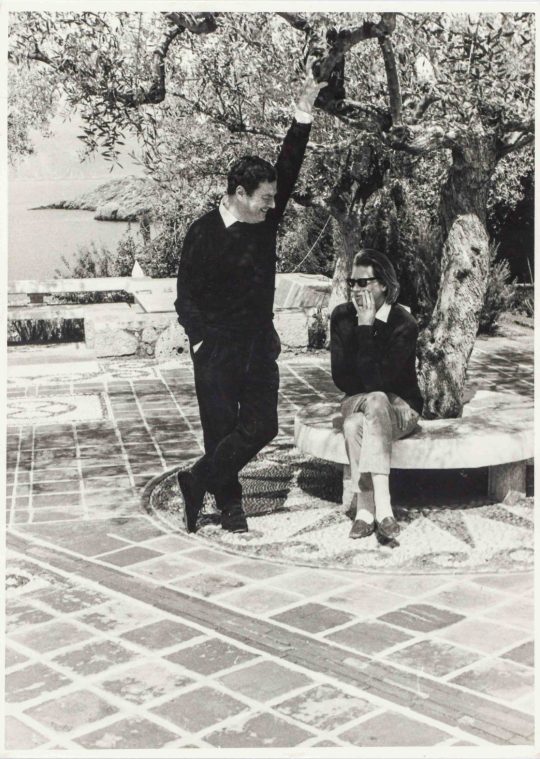

Margot Fonteyn & Frederic Ashton

Photographer Joan Leigh Fermor

0 notes

Text

3 Issues I Love About This Dwelling

The images of this home caught my eye the second I noticed them. There’s a heat to this residence that makes it really feel actually inviting. After I learn extra concerning the historical past of the home and its former homeowners—author Patrick Leigh Fermor and photographer Joan Eyres Monsell—I used to be much more captivated. This home was featured within the not too long ago launched e-book…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

From Joan by Simon Fenwick

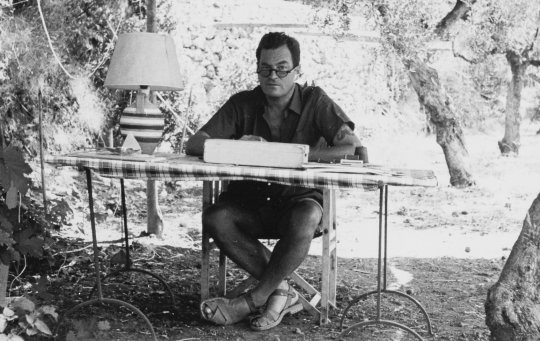

Picture of Patrick Leigh Fermor and writing extract from Paddy’s journal giving insight into marriage and life with Joan during the sixties living in Xanthi, Greece - the ordinariness perhaps strikes a hum drum chord...

“Terrible row with Joan, like a storm breaking after an oppressive day. Now I’m alone int he square, she in tears in her room both utterly miserable”

#patrick leigh fermor#joan leigh fermor#joan#marriage#writing on marriage#simon fenwick#writers#sixties

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

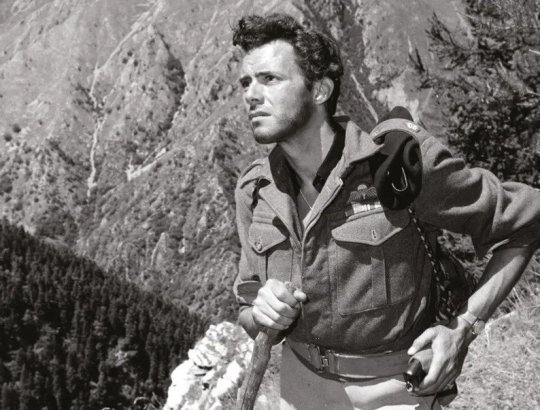

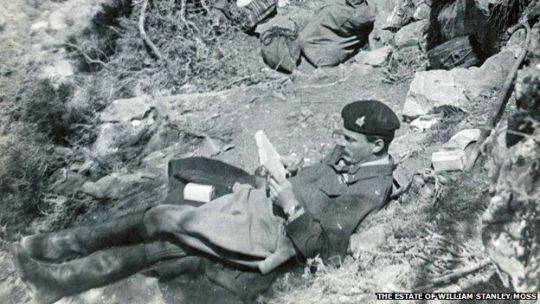

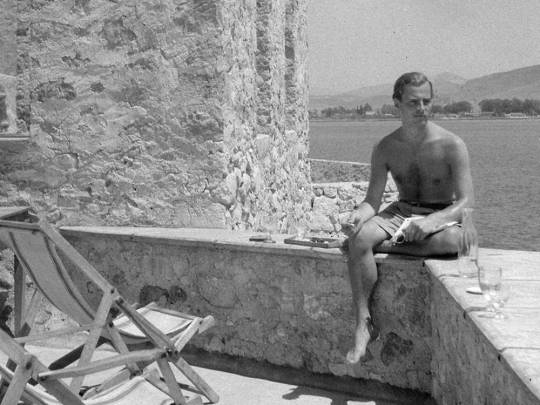

Patrick Leigh Fermor, Lixouri, Cephalonia, 1946, by Joan Leigh Fermor (© Joan Leigh Fermor Estate / National Library of Scotland, Joan Leigh Fermor Photographic Collection, Edinburgh).

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On the coast of Terra Fermoor, when the wind is on the lea, And the paddy-fields are sprouting round a morning cup of tea, Sits a lovely girl a-dreaming, and she never thinks of me. No, she never thinks of me At her morning cup of tea, Lovely girl with moon-struck eyes, Juno fallen from the skies, At the paddy-fields she looks Musing on Tibetan books, On the Coast of Terra Fermoor high above the Cretan Sea.

Melting rainbows dance around her – what a tale she has to tell, How Carmichael, the Archangel, caught her in the asphodel, And coquetting choirs of Cherubs loudly sang the first Joel, Loudly sang the first Joel To their Blessed Damozel. Ah, she’s doomed to wane and wilt Underneath her load of guilt; She will never, never say What the Cherubs sang that day, When the Wise Men came to greet her and a star from heaven fell.

Ah, her memory is troubled by a stirring of dead bones, Bodies that a poisoned poppy froze into a heap of stones; When the midnight voices call her, how she mews and mopes and moans. Oh the stirring of the bones And their rumble-tumble tones, How they rattle in her ears Over the exhausted years; Lovely bones she used to know Where the tall pink pansies blow And her heart is sad because she never saw the risen Jones.

Cruel gods will tease and taunt her: she must always ask for more, Have her battlecock and beat it, slam the open shuttledore, Till the Rayners17 cease from reigning in the stews of Singapore. She will always ask for more, Waiting for her Minotaur; Peering through the murky maze For the sudden stroke that slays, Till some spirit made of fire Burns her up in his desire And her sighs and smiles go floating skyward to the starry shore.

- Maurice Bowra, On the Coast of Terra Fermoor (10 June 1950)

The controversial Oxford scholar, poet, wit and acquaintance of Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor, Sir Cecil Maurice Bowra, wrote two poems (in 1950) that poked fun at Paddy’s relationships with Balasha Cantacuzene - his first great love - and Joan Leigh Fermor - his life long lover and eventual wife.

The poems remained hidden from public view until Henry Hardy (also know as Robert Dugdale) published Maurice Bowra’s scabrous satires on his contemporaries, New Bats in Old Belfries, in 2005, as one of Bowra’s literary executors. At the time Hardy had to leave blank spaces where two of them should have appeared. This was because their subject, Patrick Leigh Fermor, was still alive, and was unwilling to give his approval for their inclusion in his lifetime - Paddy died in June 2011, aged 96. One can only speculate why Bowra, who had a decent friendship with Fermor, would want to target Paddy Fermor in this way. Fermor after all was a celebrated writer, traveller - and Cretan war hero as a result of his activities while serving in the Special Operations Executive during the second world war.

In an extended correspondence with Hardy in his capacity as one of the editors of Bowra’s poems, PLF showed that he was much put out by the ones on himself, especially ‘The Wounded Gigolo’, which he felt was ‘a bit cracked’. He vacillated about the other poem, ‘On the Coast of Terra Fermoor’ (why did Bowra misspell ‘Fermor’?), but in the end voted against, no doubt partly influenced by the opinion of his late wife, Joan, who ‘thought that all the people mentioned in the collection would have been cut to the quick, however much they put on non-spoilsport faces.’ When James Morwood of Wadham visited him later in his Greek home to ask about his friendship with Maurice Bowra (on behalf of Leslie Mitchell, Bowra’s biographer), he found that the hurt of reading the poems was still smarting. Paddy Fermor would write to Henry Hardy to say: ‘Could Maurice’s shade ponder all this now, I think I might emerge as more of a saviour than a spoilsport.’ Paddy would express how deeply wounded he was by Bowra in his correspondence with the Duchess of Devonshire.

In April 2022, I visited the home of Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor in Kadarmyli in the Peloponnese as part of hiking and mountaineering sojourn around Greece with friends. Afterwards, back in London, I was having a family dinner which included some of my grandparents’ circle of friends in which they recalled Lord Noel Annan (he died back in 2000), the great doyenne of British academia and chronicler of his age, that Maurice Bowra was madly in love with Joan Leigh Fermor - which went unrequited.

For Bowra, Joan Eyres Monsell (1912–2003), daughter of the 1st Viscount Monsell, was his greatest love. He was devastated when she took Paddy Leigh Fermor as her second husband in 1968 after a long time living together unmarried. And he was probably more put out because the Fermors had an open relationship - or more truthfully one sided as Joan let Paddy indulge in his amorous dalliances with other women always knowing he would come back to her. Bowra described her as his ‘beautiful friend’, and Alan Pryce-Jones, her former fiancé, recalled her as ‘very fair, with huge myopic blue eyes’. Cyril Connolly, another admirer, attributed to the fictional Jane Sotheran (in his story ‘Happy Deathbeds’) Joan’s alluring physical qualities, including ‘enormous eyes of clouded violet-blue’.

In my own view is that these poems are tawdry and in bad taste. It captures perfectly - from what I’ve read or heard from others - the mean spiritedness of Maurice Bowra if you got on his bad side.

Bowra, classical scholar, warden of Wadham College, Oxford, for more than 30 years, and vice-chancellor of the university from 1951 to 1954, was the quintessential don. His learning across several languages and literatures puts most modern academics to shame. Yet this expansive erudition contrasts with the tightly knit provincial world in which he lived. Oxford was everything to Bowra. Bowra had a commanding, narcissistic personality that, within the narrow horizons of Oxford, resulted in much distasteful social and professional manoeuvring.

I think many of his peers would agree that Bowra's writings never matched the brio of his conversation. His epigrammatic wit is frequently compared with Oscar Wilde's, but Bowra's one-liners, for all their cleverness, lack the warmth and wisdom of a Wildean paradox. His most famous is a riposte to one who queried the plainness of a prospective wife: "Buggers can't be choosers." Other famous adages include his self-description as "more dined against than dining" and his claim that Noel Annan's feelings ran "only sin deep". Ultimately, this wordplay amounts to little more than high-brow camp: a sort of Carry On Common Room.

For the record Hardy outlines that Bowra’s literary models with this poem here are Kipling’s ‘Mandalay’ (1892) and Edward Lear’s ‘The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo’ (1877). Other allusions may be glossed as follows. ‘Carmichael’: members of the Cretan Resistance used ‘Kyr Michali’ (‘Mr Michael’) as a code-name for Paddy Leigh Fermor. ‘Joel’: perhaps a fusion of ‘Joan’ and ‘Noel’. ‘Damozel’: from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s eponymous poem. ‘Poppy’: a reference to Thérèse (‘Poppy’) Fould-Springer (1908–53), who suffered from sporadic mental and physical illness, and married Alan Pryce-Jones after his engagement to Joan Eyres Monsell had been ended by her parents’ opposition (he had no clear prospects). ‘Rayners’: John Rayner (1908–90), features editor of the Daily Express during the 1930s, had been Joan Eyres Monsell’s first husband.

Photo: Patrick Leigh Fermor (far left), Cyril Connolly (far right), Maurice Bowra (centre), Ernst Kantorowitz (bottom right) and Joan Leigh Fermor, 1955.

#bowra maurice bowra#quote#poem#patrick leigh fermor#joan leigh fermor#leigh fermor#friendship#society#british#oxford#university#love#history#greece#family#personal

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was midsummer in that glaring white town, and the heat was explosive. Some public holiday was in progress––could it have been the feast of St. John the Baptist which marks the summer solstice?––and the waterfront was crowded with celebrating citizens in liquefaction. The excitement of a holiday and the madness of a heat wave hung in the air. The stone flags of the water's edge, where Joan and Xan Fielding and I sat down to dinner, flung back the heat like a casserole with the lid off. On a sudden, silent, decision we stepped down fully dressed into the sea carrying the iron table a few years out and then our three chairs, on which, up to our waists in cool water, we sat round the neatly laid table-top, which now seemed by magic to be levitated three inches above the water. The waiter, arriving a moment later, gazed with surprise at the empty space on the quay; then, observing us with a quickly-masked flicker of pleasure, he stepped unhesitatingly into the sea, advanced waist deep with a butler's gravity, and, saying nothing more than "Dinner-time," placed our meal before us––three beautifully grilled kephali, piping hot, and with their golden brown scales sparkling. To enjoy their marine flavour to the utmost, we dipped each by its tail for a second into the sea at our elbow... Diverted by this spectacle, the diners on the quay sent us can upon can of retsina until the table was crowded. A dozen boats soon gathered there, the craft radiating from the table's circumference like the petals of a marguerite. Leaning from their gently rocking boats, the fisherman helped us out with this sudden flux of wine, and by the time the moon and the Dog-Star rose over this odd symposium, a mandoline had appeared and manga songs in praise of hashish rose into the swooning night [...]

from mani: travels in the southern peloponnese, patrick leigh fermor

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor, DSO, OBE (also known as Paddy Fermor) was born on February 11, 1915. He was a British author, scholar, soldier and polyglot who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during the Second World War. He was widely regarded as Britain's greatest living travel writer during his lifetime, based on books such as A Time of Gifts (1977). A BBC journalist once described him as "a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene".

In 1950 Leigh Fermor published his first book, The Traveller's Tree, about his post-war travels in the Caribbean. The book won the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature and established his career. The reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement wrote: "Mr Leigh Fermor never loses sight of the fact, not always grasped by superficial visitors, that most of the problems of the West Indies are the direct legacy of the slave trade." It was quoted extensively in Live and Let Die, by Ian Fleming. He went on to write several further books of his journeys, including Mani and Roumeli, of his travels on mule and foot around remote parts of Greece.

Leigh Fermor translated the manuscript The Cretan Runner written by George Psychoundakis, a dispatch runner on Crete during the war, and helped Psychoundakis get his work published. Leigh Fermor also wrote a novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques, which was adapted as an opera by Malcolm Williamson. His friend Lawrence Durrell recounts in his book Bitter Lemons (1957) how, during the Cypriot insurgency against continued British rule in 1955, Leigh Fermor visited Durrell's villa in Bellapais, Cyprus:

After a splendid dinner by the fire he starts singing, songs of Crete, Athens, Macedonia. When I go out to refill the ouzo bottle...I find the street completely filled with people listening in utter silence and darkness. Everyone seems struck dumb. 'What is it?' I say, catching sight of Frangos. 'Never have I heard of Englishmen singing Greek songs like this!' Their reverent amazement is touching; it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes.

After living with her for many years, Leigh Fermor was married in 1968 to the Honourable Joan Elizabeth Rayner (née Eyres Monsell), daughter of Bolton Eyres-Monsell, 1st Viscount Monsell. She accompanied him on many of his travels until her death in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. They had no children. They lived part of the year in their house in an olive grove near Kardamyli in the Mani Peninsula, southern Peloponnese, and part of the year in Gloucestershire.

In 2007, he said that, for the first time, he had decided to work using a typewriter, having written all his books longhand until then.

He opened his home in Kardamyli to the local villagers on his name day. New Zealand writer Maggie Rainey-Smith (who was staying in the area while researching for her next book) joined in with his name day celebration in November 2007, and, after his death, posted some of the photographs taken that day. The house at Kardamyli was featured in the 2013 film Before Midnight.

Leigh Fermor influenced a generation of British travel writers, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart.

Works

Books

The Traveller's Tree. (1950)

The Violins of Saint-Jacques. (1953)

A Time to Keep Silence (1957), with photographs by Joan Eyres Monsell. This was an early publication from the Queen Anne Press, a company managed by Leigh Fermor's friend Ian Fleming. In this book he describes his experiences in several monasteries, and the profound effect the time spent in them had on him.

Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese (1958)

Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece (1966)

A Time of Gifts – On Foot to Constantinople: From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube (1977, published by John Murray)

Between the Woods and the Water – On Foot to Constantinople from the Hook of Holland: the Middle Danube to the Iron Gates (1986)

Three Letters from the Andes (1991)

Words of Mercury (2003), edited by Artemis Cooper

Introduction to Into Colditz by Lt Colonel Miles Reid (Michael Russell Publishing Ltd, Wilton, 1983). The story of Reid's captivity in Colditz and eventual escape by faking illness so as to qualify for repatriation. Reid had served with Leigh Fermor in Greece and was captured there trying to defend the Corinth Canal bridge in 1941.

Foreword of Albanian Assignment by Colonel David Smiley (Chatto & Windus, London, 1984). The story of SOE in Albania, by a brother in arms of Leigh Fermor, who was later a MI6 agent.

In Tearing Haste: Letters Between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (2008), edited by Charlotte Mosley. (Deborah Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, the youngest of the six Mitford sisters, was the wife of the 11th Duke of Devonshire).

The Broken Road – Travels from Bulgaria to Mount Athos (2013), edited by Artemis Cooper and Colin Thubron from PLF's unfinished manuscript of the third volume of his account of his walk across Europe in the 1930s.

Abducting A General – The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete (2014)

Dashing for the Post: the Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor (2017), edited by Adam Sisman

More Dashing: Further Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor (2018), edited by Adam Sisman

Translations

No Innocent Abroad (published in United States as Forever Ulysses) by C. P. Rodocanachi (1938)

Julie de Carneilhan and Chance Acquaintances by Colette (1952)

The Cretan Runner: His Story of the German Occupation by George Psychoundakis (1955)

Screenplay

The Roots of Heaven (1958) adventure film, directed by John Huston

Periodicals

"A Monastery", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 979, Summer, 1949.

"From Solesmes to La Grande Trappe", in The Cornhill Magazine, John Murray, London, no. 982, Spring 1950.

"Voodoo Rites in Haiti", in World Review, London, October 1950.

"The Rock-Monasteries of Cappadocia", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 986, Spring 1951.

"The Monasteries of the Air", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 987, Summer 1951.

"The Entrance to Hades", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 1011, Spring 1957.

Books about Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor

Artemis Cooper: Patrick Leigh Fermor. An Adventure (2012)

Helias Doundoulakis, Gabriella Gafni: My Unique Lifetime Association with Patrick Leigh Ferrmor (2015)

Simon Fenwick: Joan. The Remarkable Life of Joan Leigh Fermor (2017)

Michael O'Sullivan: Patrick Leigh Fermor, Noble Encounters between Budapest and Transylvania (2018)

Leigh Fermor was noted for his strong physical constitution, even though he smoked 80 to 100 cigarettes a day. Although in his last years he suffered from tunnel vision and wore hearing aids, he remained physically fit up to his death and dined at table on the last evening of his life.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to say good-bye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife.

Leigh Fermor died in England, aged 96, on 10 June 2011, the day after his return. His funeral took place at St Peter's Church, Dumbleton, Gloucestershire, on 16 June 2011. A Guard of Honour was provided by serving and former members of the Intelligence Corps, and a bugler from the Irish Guards sounded the Last Post and reveille. Leigh Fermor is buried next to his wife in the churchyard at Dumbleton.

The Greek inscription is a quotation from Konstantinos Kavafis that can be translated as "In addition, he was that best of all things, Hellenic".

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

30 notes

·

View notes