#jan assmann

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Antisémitisme

Rudolf Kreis a été membre des jeunesses hitlériennes, puis il a servi comme officier dans les Panzer-divisions des Waffen SSi. Vers la fin de sa vie, en 2009, il a publié un ouvrage, Die Toten sind immer die anderen (« Les morts ce sont toujours les autres »), décrivant sa « jeunesse entre les deux guerres »ii. Peu après cette publication, Jan Assmanniii, un célèbre égyptologue allemand…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

CENNI SUL PENSIERO FILOSOFICO DEGLI ANTICHI EGIZI

CENNI SUL PENSIERO FILOSOFICO DEGLI ANTICHI EGIZI “Soldati, dall'alto di queste piramidi, quaranta secoli vi guardano.” E' la storica frase che Napoleone I rivolse la mattina del 21 luglio 1789 ai soldati dell'armata di Egitto prima della famosa Battaglia delle Piramidi e, nonostante, le immense ricchezze archeologiche, storiche e artistiche che ci sono state tramandate, anche gli Egizi mettevano in discussione il mondo e quindi producevano un loro...

“Soldati, dall’alto di queste piramidi, quaranta secoli vi guardano.” E’ la storica frase che Napoleone I rivolse la mattina del 21 luglio 1789 ai soldati dell’armata di Egitto prima della famosa Battaglia delle Piramidi e, nonostante, le immense ricchezze archeologiche, storiche e artistiche che ci sono state tramandate, anche gli Egizi mettevano in discussione il mondo e quindi producevano un…

0 notes

Text

Mehr oder weniger gespalten

Wo stehen wir nach all den Krisen der vergangenen Jahre als Gesellschaft? Gibt es noch einen gemeinschaftlichen Konsens? Was ist überhaupt diese so umkämpfte Mitte der Gesellschaft? Einige aktuelle Bücher gehen diesen Fragen auf den Grund.

Wo stehen wir nach all den Krisen der vergangenen Jahre als Gesellschaft? Gibt es noch einen gemeinschaftlichen Konsens? Was ist überhaupt diese so umkämpfte Mitte der Gesellschaft? Wer darf in dieser Platz nehmen und welche Themen werden dort verhandelt? Und was ist eigentlich mit dieser digitalen Welt, in die alles strebt? Einige aktuelle Bücher gehen diesen Fragen auf den Grund. Continue…

View On WordPress

#Aleida Assmann#Bernd Stegemann#Bernhard Pörksen#Carolin Amlinger#Donald Trump#featured#Friedenspreis des deutschen Buchhandels#Jan Assmann#Jonathan Crary#Julia Ebner#Linus Westheuser#Oliver Nachtwey#Peter R. Neumann#Preis der Leipziger Buchmesse#Sascha Lobo#Steffen Mau#Stephan Anpalagan#Thomas Lux#Wladimir Putin#Xi Jinping

0 notes

Text

KLAUS BERGDOLT IST LETZTES JAHR GESTORBEN???

#sorry that's a historian#i am. i didn't know?#oh this is so sad. like. for me personally worse than jan assmann.#I cited this man several times. he had really good source-related points on the plague of 1352.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually we ALL need to be thinking more abt the roman empire bc if I have to read One More Take in my studies abt how monotheism is the reason christianity is so violent im gonna start hitting people in the knees

#like 😭😭😭😭😭#they adopted christianity and used it as a tool to continue to expand their empire#they were already incredibly violent and exclusionary they just found a new means to an end#and it spiraled into The Bullshit#like I could scream w every take on ✨the mosaic distinction✨#hitting jan assmann w the girl baseball bat as we speak#sorry none of you know what I'm talking about this is so niche#(meaning jan assmann and the mosaic distinction I hope you do all know abt the holy roman empire)#religious studies rambling

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

they're like parents to me

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yes. She is sorely missed.

I miss fedon so much!

She's ver missed.

#I miss her insight#I miss our conversations#where we bonded over our shared love of the work of jan assmann#nerding out over this German egyptologist

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystic Egyptian Polytheism Resource List

Because I wanted to do a little more digging into the philosophy elements explored in Mahmoud's book, I took the time tonight to pull together the recommended reading he listed toward the end of each chapter. The notes included are his own.

MEP discusses Pharaonic Egypt and Hellenistic Egypt, and thus some of these sources are relevant to Hellenic polytheists (hence me intruding in those tags)!

Note: extremely long text post under this read more.

What Are The Gods And The Myths?

ψ Jeremy Naydler’s Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It dives deep into how the ancients envisioned the gods and proposes how the various Egyptian cosmologies can be reconciled. ψ Jan Assmann’s Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism focuses on New Kingdom theology by analyzing and comparing religious literature. Assmann fleshes out a kind of “monistic polytheism,” as well as a robust culture of personal piety that is reflected most prominently in the religious literature of this period. He shows how New Kingdom religious thought was an antecedent to concepts in Hermeticism and Neoplatonism. ψ Moustafa Gadalla’s Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are The One provides a modern Egyptian analysis of the gods, including reviews of the most significant deities. Although Gadalla is not an academic, his insights and contributions as a native Egyptian Muslim with sympathies towards the ancient religion are valuable.

How to Think like an Egyptian

ψ Jan Assmann’s The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It illuminates Egyptian theology by exploring their ideals, values, mentalities, belief systems, and aspirations from the Old Kingdom period to the Ptolemaic period. ψ Garth Fowden’s The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind identifies the Egyptian character of religion and wisdom in late antiquity and provides a cultural and historical context to the Hermetica, a collection of Greco-Egyptian religious texts. ψ Christian Bull’s The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom provides a rich assessment of the Egyptian religious landscape at the end of widespread polytheism in Egypt and how it came to interact with and be codified in Greek schools of thought and their writings.

How To Think Like A Neoplatonist

Radek Chlup’s Proclus: An Introduction is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It addresses the Neoplatonic system of Proclus but gives an excellent overview of Neoplatonism generally. It contains many valuable graphics and charts that help illustrate the main ideas within Neoplatonism. ψ John Opsopaus’ The Secret Texts of Hellenic Polytheism: A Practical Guide to the Restored Pagan Religion of George Gemistos Plethon succinctly addresses several concepts in Neoplatonism from the point of view of Gemistos Plethon, a crypto-polytheist who lived during the final years of the Byzantine Empire. It provides insight into the practical application of Neoplatonism to ritual and religion. ψ Algis Uzdavinys’ Philosophy as a Rite of Rebirth: From Ancient Egypt to Neoplatonism draws connections between theological concepts and practices in Ancient Egypt to those represented in the writings and practices of the Neoplatonists.

What Is “Theurgy,” And How Do You Make A Prayer “Theurgical?”

ψ Jeffrey Kupperman’s Living Theurgy: A Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology and Theurgy is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It is a practical guide on theurgy, complete with straightforward explanations of theurgical concepts and contemplative exercises for practice. ψ Gregory Shaw’s Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus demonstrates how Iamblichus used religious ritual as the primary tool of the soul’s ascent towards God. He lays out how Iamblichus proposed using rites to achieve henosis. ψ Algis Uzdavinys’ Philosophy and Theurgy in Late Antiquity explores the various ways theurgy operated in the prime of its widespread usage. He focuses mainly on temple rites and how theurgy helped translate them into personal piety rituals.

What Is “Demiurgy,” And How Do I Do Devotional, “Demiurgical” Acts?

ψ Shannon Grimes’ Becoming Gold: Zosimos of Panopolis and the Alchemical Arts in Roman Egypt is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It constitutes an in-depth look at Zosimos—an Egyptian Hermetic priest, scribe, metallurgist, and alchemist. It explores alchemy (ancient chemistry and metallurgy) as material rites of the soul’s ascent. She shows how Zosimos believed that partaking in these practical arts produced divine realities and spiritual advancements. ψ Alison M. Robert’s Hathor’s Alchemy: The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art delves deep temple inscriptions and corresponding religious literature from the Pharaonic period and demonstrates them as premises for alchemy. These texts “alchemize” the “body” of the temple, offering a model for the “alchemizing” of the self. ψ A.J. Arberry’s translation of Farid al-Din Attar’s Muslim Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat al-Auliya contains a chapter on the Egyptian Sufi saint Dhul-Nun al-Misri (sometimes rendered as Dho‘l-Nun al-Mesri). He is regarded as an alchemist, thaumaturge, and master of Egyptian hieroglyphics. It contains apocryphal stories of his ascetic and mystic life as a way of “living demiurgically.” It is an insightful glimpse into how the Ancient Egyptian arts continued into new religious paradigms long after polytheism was no longer widespread in Egypt.

Further Reading

Contemporary Works Assmann, Jan. 1995. Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism. Translated by Anthony Alcock. Kegan Paul International. Assmann, Jan. 2003. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. Bull, Christian H. 2019. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Brill. Chlup, Radek. 2012. Proclus: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. Escolano-Poveda, Marina. 2008. The Egyptian Priests of the Graeco-Roman Period. Brill. Fowden, Garth. 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Cambridge University Press. Freke, Tim, and Peter Gandy. 2008. The Hermetica: The Lost Wisdom of the Pharaohs. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin. Gadalla, Moustafa. 2001. Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are The One. Tehuti Research Foundation. Grimes, Shannon. 2019. Becoming Gold: Zosimos of Panopolis and the Alchemical Arts in Roman Egypt. Princeton University Press. Jackson, Howard. 2017. “A New Proposal for the Origin of the Hermetic God Poimandres.” Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 17 (2): 193-212. Kupperman, Jeffrey. 2014. Living Theurgy: A Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology and Theurgy. Avalonia. Mierzwicki, Tony. 2011. Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment. Llewellyn Publications. Naydler, Jeremy. 1996. Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred. Inner Traditions. Opsopaus, J. 2006. The Secret Texts of Hellenic Polytheism: A Practical Guide to the Restored Pagan Religion of George Gemistos Plethon. New York: Llewellyn Publications. Roberts, Alison M. 2019. Hathor’s Alchemy: The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art. Northgate Publishers. Shaw, Gregory. 1995. Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus. 2nd ed. Angelico Press. Snape, Steven. 2014. The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. Uzdavinys, Algis. 1995. Philosophy and Theurgy in Late Antiquity. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books. Uzdavinys, Algis. 2008. Philosophy as a Rite of Rebirth: From Ancient Egypt to Neoplatonism. Lindisfarne Books. Wilkinson, Richard H. 2000. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

Ancient Sources in Translation Attar, Farid al-Din. 1966. Muslim Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat alAuliya. Translated by A.J. Arberry. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Betz, Hans Dieter. 1992. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Copenhaver, Brian P. 1995. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Guthrie, Kenneth. 1988. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press. Iamblichus. 1988. The Theology of Arithmetic. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press. Iamblichus. 2003. Iamblichus: On the Mysteries. Translated by Clarke, E., Dillon, J. M., & Hershbell, J. P. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. Iamblichus. 2008. The Life of Pythagoras (Abridged). Translated by Thomas Taylor. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. Lichtheim, Miriam. 1973-1980. Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volumes I-III. Berkeley: University of California Press. Litwa, M. David. 2018. Hermetica II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Majercik, Ruth. 1989. The Chaldean Oracles: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Leiden: Brill. Plato. 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper and D. S. Hutchinson. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. Plotinus. 1984-1988. The Enneads. Volumes 1-7. Translated by A.H. Armstrong. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Van der Horst, Pieter Willem. 1984. The Fragments of Chaeremon, Egyptian Priest and Stoic Philosopher. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

#mystic egyptian polytheism#resource list#philosophy#neoplatonism#egyptian polytheism#hellenic polytheism#hermeticism

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

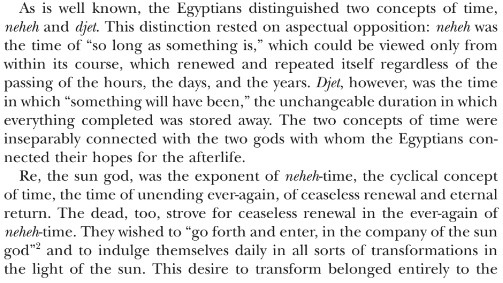

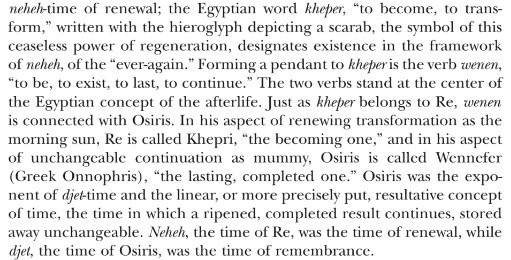

Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt by Jan Assmann, 2011 (pages 371-372)

This is all a very interesting perspective on pagan apotheosis and self-deification. Becoming-divine here means to be endlessly renewed in the cyclical time embodied by Ra, divine sun, and indulge every transformation you desire in the power of the sun god. The ancient Egyptian soul desired to achieve this state after death, and for them that meant joining the company of Ra. Assmann doesn't say as such but I like to think that means joining Ra on the solar barque and thus participating in the struggle against Apep. There are many interesting implications to consider and derive from here, especially in regards to "dying to yourself" - there is a sense in which you would be enacting the self-regenerating immortality of the sun.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Seth is the god of blasphemous and scandalous curiosity. This is also the theme of a myth told by Ovid and several other ancient authors that provides an explanation of animal worship in ancient Egypt. The gods, it is revealed, so feared the reckless curiosity of Seth-Typhon that they decided to disguise themselves in the shapes of animals. Later they declared these animals sacred out of gratitude to them. Diodorus of Sicily, who calls the cult of the animals an aporrhêton dogma (unspeakable secret) replaces “Seth” with “humankind” in his rendering of the story, which is how he claims to have heard it in Egypt. It seems possible that this very strong and conspicuous condemnation of curiosity reflects an Egyptian reaction to the scientific and investigative mind of the Greeks, who subjected the Egyptians to a veritable program of “Egyptological” research. It strangely foreshadows Saint Augustine’s verdict on curiosity, which dominated the occidental attitude toward the world and nature until the end of the sixteenth century. Another work in which the theme of curiosity plays a central role is The Golden Ass, by Apuleius of Madauros. Lucius, the hero, dabbles in magic out of an insatiable curiosity and is punished by being transformed into an ass, the animal of Seth, whose principal vice he practiced."

Jan Assmann, Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Previous Book' Bingo # 1

A Nightmare on Elm Drive

Early Indians - Tony Joseph

Diatessaron - Tatian (Religious)

Moses and Monotheism (1939)

And then there were none [12]

The Price of Monotheism - Jan Assmann

Moses the Egyptian - Jan Assmann

Muhammad [France]

Trial of Joan of Arc (4.2)

Tuzak i Jahangiri [Biography]

The Jatakas (India)

32 Throne Tales of Vikramaditya [Orange]

Vivekachudamani (INR 550)

Delhi 1857 Voices from Siege

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Motifs of death were omnipresent in Giger's work since his early days. [...] the important role of ancient Egyptian culture in this context goes back to Giger's early youth: “As a kid, for a while every Sunday morning I walked alone to the Rhaetian Museum in Chur. The mummy of an Egyptian princess was displayed in the basement vault. This mysterious black body attracted me tremendously, but it also scared me. Primordial life processes have always fascinated me.” Just staring at the approximately 2,700-year-old mummy of Ta-di-Isis from Thebes created that familiar mixture of horror and fascination that would fuel his further exploration of fears and spiritual abysses. The close connection between themes is directly related to the role of death in ancient Egypt: it was, as the Egyptologist Jan Assmann explains, “a center of cultural consciousness, one that radiated out into many—we might almost say, into all—other areas of ancient Egyptian culture.” Assmann also uses the findings to make a more generalized statement: “Death is the Origin and center of culture. Death—that means the experience of death, the knowledge of the finite nature of life... the symbolic exchange between the worlds of the living and the dead, the pursuit of immortality, of continuation in any form, of any lasting traces and effects, of more world and more time.”

— Andreas J. Hirsch, HR Giger 40th Anniversary Edition

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

list of people that hate me and want to make my life as hard as possible by hiding the meanings of their sentences behind complex and impossible to understand word choices:

Juri Lotman when he was writing his papers about memory in a culturological light

Jan Assmann when he was writing his papers about the different characteristics of cultural memory

And most likely every old white man whose papers i will read on this topic

#vent post#but like#academic#AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been reading a couple books on Ancient Egyptian history (Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs by Barbara Mertz and The Mind of Egypt by Jan Assmann), and I’m struck by two things:

For being a Bronze Age kingdom ruled by literal god-kings, Ancient Egypt looks surprisingly nice. Sure, they had their share of dispotism, chauvinism, and imperial warfare, but I haven’t found anything like Assyrian brutality on prisoners, Roman blood sports, Greek slave economy and rampant misogyny, or Aztec mass human sacrifices. For the standards of antiquity (which are very low to us), it seems an actually pretty decent place to have lived as a commoner.

The development of culture and worldview looks so strangely like a coherent arc. First there’s Ancient Kingdom pharaohs, who look so aloof and self-sufficient in their divinity. Then the kingdom collapses in rebellion and civil war, teaching the rulers of Egypt that they have responsibilities towards their people; Middle Kingdom pharaohs care a lot more about justifying their position with philosophy and theology. That era collapses too, with an invasion and occupation that teaches them that the rest of the world exists, too; and the New Kingdom is defined by imperial engagement with the great powers of Asia. Eventually the state model of the Bronze Age becomes unsustainable and Egypt fades into a province of distant empires, ruled by fatalism and detachment. This honestly sounds like the kind of satisfying storytelling that one should be most skeptical about in history; I wonder how much this understanding is due to scarcity of records, pareidolia, and my own ignorance, and in what proportion.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

6 for the book ask!

6.Was there anything you meant to read, but never got to?

ooh that's a very long list lmao.

I was like let's read the ones that I have a physical copy of first but then I didn't do that

I got Reason and Revolution by Herbert Marcuse from that free library but I don't know when I'll start that one

I also got two books, Libertalia, Free pirate communities - The first democratic constitutions of the new age (that's the Hungarian title translated to English by me btw), and Jan Assmann: Cultural memory for my birthday back in April that I want to read at some point..

I've been also meaning to read Anti-Oedipus by Deleuze and Guattari but I'm stuck on reading a reader's guide for Anti-Oedipus since last year lmao

there are many other books I'm planning on reading but I thought I would at least get halfway through these this year

#and I know _will_ continue adding more books to my reading list#for next year I'm planning on reading some anarchist books& Guy Debord's The society of the spectacle & Chernyshevsky's What is to be done#.. and finishing those that I started..

1 note

·

View note

Note

any recs for intro/base level jewish study texts? np if they’re academic ones I can use my uni’s library :-)

oooo okay. fair warning my minor is history so a lot of this is history focused but there are a lot of modern Jewish studies as well! like intersections w queerness and feminism etc. it is just not my wheelhouse.

starting w some comparative religion is always a solid base when it comes to academics bc some of the first classes are like world religions etc. it has been so long that i do Not remember which one i used but really any "intro to world religions" textbook that your uni's library has is good! and if you want to just focus on the section about Judaism go for it. looking at Christianity and Islam might also be helpful though to put it into some context.

A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood by Raymond P. Scheindlin is excellent. here if you want to dig deeper whenever it mentions a Jewish thinker/scholar, try and find some primary resources of their writings! like Moses Maimonides, possibly the most influential Jewish philosopher, or Moses Mendelssohn (another philosopher and theologin).

Genesis, Exodus, and Deuteronomy. if you wanna go the extra mile go for the whole Torah (so Leviticus and Numbers as well), but these three do a solid job of giving a good idea of the more non-historical aspect of Jewish religious history and will give you a good idea of where a lot of customs, laws, etc came from. of particular note are gonna be the two accounts of the Sinai event in both Exodus and Deuteronomy and ask yourself: why do they differ? why do you think that is? what could this tell you about Judaism and the ancient Israelites when each account was written?

I have not read it but Wanderings by Chaim Potok is a highly recommended one outside of academia and one that I know some goyim have read as well to better understand Jewish history. however I haven't read it so I don't know if there's any issues with it as it is an older work.

another one i see around a lot outside of academics is The Jewish Book of Why by Alfred J. Kolatch. this one is less history and more, as the title says, a book about Why and ritual/custom/etc.

more intermediate/deeper dives

this is my own personal niche so if you do not care about this you can ignore this section but I find it so interesting and useful/helpful to look at just How Judaism evolved and some good ones for that are The Origins of Biblical Monotheism by Mark S. Smith and as much as I have some beef w the man Jan Assmann is going to crop up a Lot in these types of discussions so giving him a read is useful, particularly Moses the Egyptian and The Price of Monotheism. give it a critical read though, I personally disagree w a lot of his conclusions but I find his work and history he gives to be of note & worthwhile. you might find you do totally agree and that's fine too.

continuing off of That i personally think the Ugaritic texts are incredibly important in understanding the context of the ancient Israelite religion that came before Judaism and thus Judaism itself and so if you're interested more in that type of ancient history when it comes to Jewish studies giving them a read is really eye-opening bc it gives you an idea of what sort of cultural knowledge was assumed by the writers of the Tanakh. like they were writing it with the assumption that their readers would Know these stories that were shared in this region so reading them is super helpful with putting certain customs/belief into context. but that's more of a lil deep dive so if you don't wanna do that you absolutely do not have to. rn i'm reading Stories From Ancient Canaan by Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith

#long post#religious studies rambling#ignore my plurality typo there for a minute i changed a few words and forgot to change the conjugation <3

9 notes

·

View notes