#j. alvarez

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I have been watching oitnb for probably 10 years now which is the longest I have ever taken for a show (and I still have 1 season to go). and the weirdest thing is, it's not bc I dislike the show in any way, I actually really enjoy it, but it's somehow one of the most exhausting things to watch, mostly bc there is so much plot condensed into a time frame of like a few days to a few months at max. I personally am not a fan of this bc I like 1 season = 1 year, but me watching this show so slowly is mostly due to the fact that I have to be in a very specific mood to handle it. I don't quite know why, but it's similar for me with got (even though I'm clearly more often in the mood for that than oitnb).

anyway, very long prologue for wanting to say that season 6 was great, probably my favorite so far, next to season 2 I think. I only didn't enjoy the one with vee (was that season 3?) too much, but I generally liked all of them for different reasons. and season 7 is said to be one of the best overall tv show seasons, so I'm excited for that.

I particularly liked 6 bc the plot was very organized in the sense that we had a premise from about episode 2 onwards and there was a conclusion at the end (even though it was different than expected and I loved that it was for once an almost happy ending). I personally loved carol and barb, it was such wonderful dark humor, and the little 80s flashbacks were a treat. the other minor characters like the new (esp alvarez giving autistism rep) and the old guards (esp the mormon one) were great as well (not as in nice people neccessarily, but they made a great backdrop) and generally none of the new characters felt forced and I'm glad they will all return next season. and who thought caputo and fig would be the cutest couple of the season?? I also liked alex and piper, but I was so certain piper was gonna do something stupid again and mess up her early release. but yay she did it!

it's also worth mentioning that there were some really sad and dark things again that were really well done, like daya's abuse, the trial around taystee, and flores' deportation at the end. oitnb is just one of the few shows that ace dramedy so perfectly by balancing hilarious and devastating scenes.

#orange is the new black#season 6#game of thrones#carol denning#barbara denning#j. alvarez#ryder blake#joe caputo#natalie figueroa#alex vause#piper chapman#dayanara diaz#tasha jefferson#blanca flores

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

AUGUST MUSIC WRAP-UP

These is the new music I listened to in August! ARTIST: Emily Mei SONG: Mania ARTIST: Within Temptation SONG: Bleed Out ARTIST: Written by Wolves SONG: Altar ARTIST: Bludnymph SONG: Lights Out ARTIST: Bludnymph SONG: Watch Me (these are songs that are not new to me but I’ve been in the mood to play them often recently) ARTIST: Shadow Age SONG: Silaluk ARTIST: J. Alvarez SONG: Dos…

View On WordPress

#bludnymph#emily mai#j. alvarez#music#pacho y cirilo#shadow age#the rasmus#within temptation#written by wolves

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

part 6!! < pt.5 pt.7 >

tag panopticon for @andrewsleftarmband <3

more brewing but i fear they’re close to generating an actual plot so this may go on for some time

#adler seth gordon princessita agenda unfortunately working at full strength and j am having to separate seth tweets to avoid spam#aftg socmed au#aftg#neil josten#andrew minyard#tsc#jean moreau#cat alvarez#jeremy knox#nicky hemmick#laila dermott#dan wilds#seth gordon#allison reynolds#renee walker

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jonathan on the Vulture Festival red carpet discussing his three most emotional performances.

#jonathan groff#looking hbo#Michael Lannan#john hoffman#Frankie j Alvarez#appearance#vulture festival#merrily we roll along

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Brian J. Alvarez#Socks#Gray and Black Socks#Polka Dot Socks#Jonathan Groff#Multi Colored Socks#Novelty Socks

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

POV: You’re old and technology is hard

#hollywood undead#danny murillo#jorel decker#j dog#funny man#dylan alvarez#johnny 3 tears#George ragan#song was sick

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

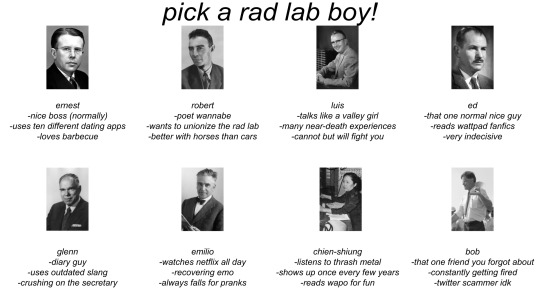

pick a best friend

You know that meme where they show you different outfits and you think of names of the people who would wear them and talk about their personalities?

I have no idea how true this is but pick a Rad Lab "boy"

#manhattan project#rad lab#uc berkeley#ernest lawrence#j robert oppenheimer#luis alvarez#edwin mcmillan#glenn seaborg#emilio segre#chien shiung wu#robert wilson#pick a best friend

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random post

#hollywood undead#hollywoodundead#j dog#jorel decker#charlie scene#jordon terrell#funny man#dylan alvarez#johnny 3 tears#george ragan

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Various Instagram photos from Alexis Forte (Raul Castililo’s partner)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

#tv shows#tv series#polls#looking hbo#jonathan groff#frankie j alvarez#2010s series#us american series#have you seen this series poll

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#posting it here bc on twitter nobody cares#looking hbo#jonathan groff#frankie j alvarez#murray bartlett#raul castillo

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How accurate am I? (spoiler; I am very accurate) @diilyduzit @cringyedge

#hollywood undead#jorel decker#j dog#hu#danny murillo#j3t#johnny 3 tears#funny man#dylan alvarez#george ragan#charlie scene#jordon terrell#danny rose murillo#danny rose

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

First day for these boys!

#New York Mets#mets#baseball#new york#new york city#mlb#major league baseball#Sean Maneaea#David Peterson#Francisco Alvarez#A J Minter

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A video of the full panel is available at the link, including an edited transcript. Some quotes:

A decade ago, in a very different San Francisco and a very different television landscape, Patrick Murray and his friends first stumbled onto HBO — literally, the pilot starts with Jonathan Groff ineptly cruising in a public park. Looking was a low-key, intentionally under-glamorous depiction of the lives of a few gay male friends played by Groff, future White Lotus employee Murray Bartlett, and Frankie J. Alvarez, as well as their token straight-woman-friend Doris (Lauren Weedman) and Patrick’s pair of love interests, played by Raúl Castillo and Russell Tovey. Created by Michael Lannan with the close involvement of director Andrew Haigh (of All of Us Strangers), Looking intentionally tacked away from the soap-operatics of gay dramas like the American Queer As Folk while still wrestling with the hot topics of gay life during the second Obama administration: PrEP, Grindr, marriage equality. In its two-season run plus a wrap-up film, the show was never a ratings smash — its time slot, right next to Girls, may have led some audiences to expect satire where Looking bent toward sweet earnestness — though it became the subject of furious discussion on social media, perhaps also a novel dynamic at the time. Looking lives on as a cult favorite, discovered and revisited by new fans online, and it remains a beloved project for its cast and crew.

Jonathan Groff: I auditioned in L.A. I had seen Weekend, and I was a puddle after that movie was over. I was so blown away and had never seen a gay movie or show that felt so relatable. And then when I heard the director of that was directing this pilot, I got really excited. It was the scene with Richie when he’s hitting on Patrick on the train in the pilot. I remember blushing for real, because until that moment in that room, I had never actually played “gay” in that way before, and it was such a confronting, scary, exciting experience. I was like, Whoa. I felt actually hot.

Frankie Alvarez: That’s because you weren’t playing, you were revealing.

J.G.: Yeah, exactly! I kind of left on a high from that audition. It felt a little scary to … It’s one thing to be out, but then it’s another thing to, like, douche on-camera. [Laughs] And it’s like, “Wow, I guess if I do this show, it’s really like G-A-Y across my forehead.” At that time, there was this notion that if you were gay and you played gay, that was all that you were going to be able to do. But I felt it so deeply that I ended up not caring as much about that and wanting to play the role.

F.A.: That reminds me of a story. When you came out to your parents, you told your mom, “I’m never gonna be the grand marshal at the Gay Pride Parade.”

J.G.: And then we were in the Pride Parade together! I came out in 2009, and by 2013, we were at the front of the parade!

John Hoffman: …That whole first season was magic. Michael and Andrew were so open and kind and generous. And then I made Jonathan douche! I wanted everyone to get naked more! I was the one in the room going, “Guys, we need more people watching, so everybody has to be naked a lot more and having more sex!”

Lauren Weedman: If you’ve got an ass, get a fork! We’re eating!

Michael Lannan: Well, when I was rewatching it recently, I was like, “Man, there’s a lot of desire and kissing and sex!” I was like, “Oh my God, we did that!”

J.H.: Everywhere I could! Although, I later became friends with Shirley MacLaine, who’s now 90-something. I got her to watch Looking, and she said, “That is quite a show. I really enjoyed it. One note — too much kissing.” [Laughs]

L.W.: No kissing, just fucking. Is that the show’s point?

F.A.: Straight to the bottom-ing!

In an oral history about the show, one of the things that came up, alongside John being the one who really wanted douching onscreen, was how much the characters started to mold around the actors. I think one of you said, “We didn’t want to tell too much to Michael and Andrew because it might just appear onscreen.” Did you feel the sense of these characters becoming expressions of yourselves?

J.G.: To me, almost to an embarrassing point. I was figuring it out as I went along and offering up vulnerable truths. I remember being in a diner with Andrew, and he was like, “Tell me about your last breakup” and then writing down in the notes for the fight for me and Kevin at the end of the season, where we’re moving in with each other. And then I got to act that out! And the boyfriend who it was kind of about was like, “Wow, okay, so … did you tell them about it?” It was a great gift. For the actors to offer up tidbits and whatever, and then to have the writers and the directors make it artfully a part of the story, it was incredible. It was like actual therapy.

L.W.: I remember we were at the Paley Center and people were getting up and going, “I don’t see myself represented!” I thought it was beautiful, because it mattered! There’s one little morsel out there of some show that maybe you have a chance to see yourself, and people are like, “I want to be seen on this!” Of course, I’m not the writer. Much worse to be the writer. [Laughs] The reaction — it felt like it really mattered.

J.G.: I was shocked to see our gentleness attacked in such an aggressive way by what people were typing. It made me, what you were saying, Lauren, feel like, Wow, I guess this is way more meaningful than I ever anticipated. That people are actually upset and angry and furious and bored, or whatever it was they were feeling that they felt they had to kind of shout it from the rooftops. It’s a testament to the point of view of Michael and Andrew that they held fast to what they wanted to do. They heard criticism and they applied it, but they didn’t change what the core of the show was. And I think that’s why we’re here, because you had such a specific point of view. It’s such a lesson in digging in and connecting to your truth, and not letting negative noise affect that. But it was so hard for you guys! I remember it was coming from every angle.

Do you have memories of favorite places you got to film in San Francisco? Especially in that moment in time, because that city has changed so much.

M.L.: We filmed Patrick and Richie dancing at the Stud, and they kiss at the exact spot where I had my first kiss. It was crazy and beautiful. When that happened, I was like, “Wow, this really is a simulation.”

J.G.: That’s the one that came to my mind, too, because I remember you being there, and I remember us dancing. It was so hot, by the way. Super-hot.

M.L.: Temperature-wise?

J.G.: No, sexual tension! [Laughs] It was in this cool gay bar in San Francisco, and I remember you saying to the director of that episode, “Please push the camera in,” because it was a faraway shot. It was like your heart and your soul knew that we gotta go in on this. I remember feeling that and feeling you and really feeling like, “Oh, wow, I’m inside of somebody’s brain and heart right now, and I’m with this guy.” It felt like an artistic, transcendent moment. It was such a special thing to be inside of your memory of your first kiss. You were channeling something. The storytelling thing was happening.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking

TV Shows/Dramas watched in 2025

Looking (2014-16, USA)

Creator: Michael Lannan (based on his own short film)

Directors: Andrew Haigh, Ryan Fleck, Joe Swanberg, Jamie Babbit & Craig Johnson

Mini-review:

Why in the world did I take so freaking long to watch this? It's so damn good! Although, in a way, I'm glad I waited till now, cause it perfectly captures the moment me and my friend group are going through right now. And the show just has so much interesting stuff to say about relationships, modern love and growing up when you don't feel you're ready. I saw a lot of me in the main character, which at times made for an awkward watch, but it also made me feel understood. By the time I was done with the movie finale, I couldn't help but think that I would have loved to spend way more time with these characters. Also, Looking definitely joins the list of shows and movies that make me want to pack up my things and move to San Francisco.

#looking#looking hbo#michael lannan#andrew haigh#ryan fleck#joe swanberg#jamie babbit#craig johnson#jonathan groff#frank j alvarez#murray bartlett#lauren weedman#russel tovey#raúl castillo#scott bakula#o t fagbenle#andrew law#ptolemy slocum#joseph williamson#daniel franzese#chris perfetti#bashir salahuddin#dramedy#queer characters#queer comedy#gay comedy#gay characters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

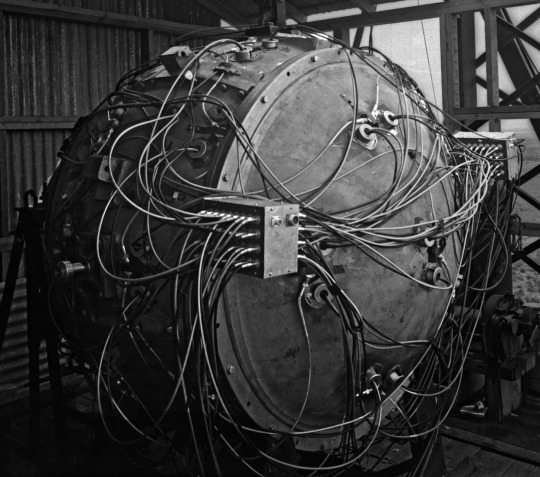

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

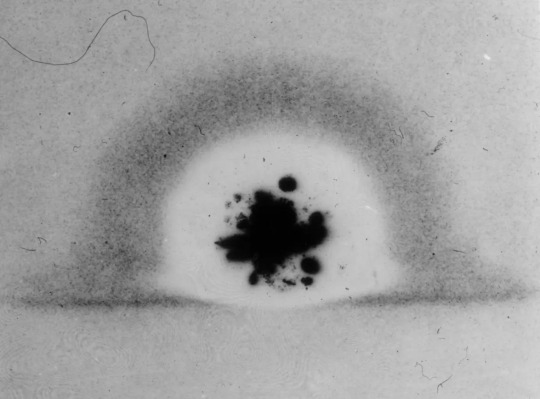

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

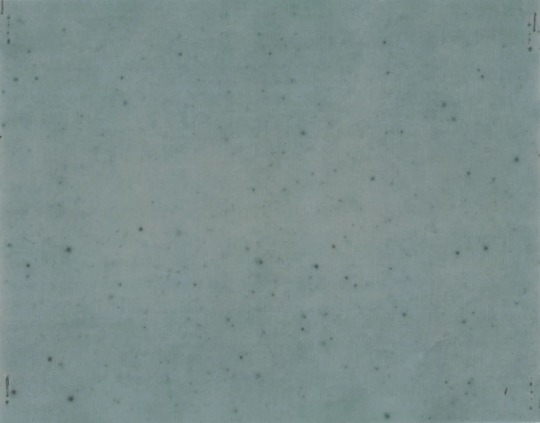

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes