#it's from a book by martin le franc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

witches + art

#it's from a book by martin le franc#artist is frans francken the younger#artist john william waterhouse#artist is francisco goya#artist is remedios varo#artist is benjamin west#artist is alexandre-gabriel decamps#artist is john william waterhouse-#artist is william blake#artist is frederick sandys#artist is salvator rosa#artist is frans francken the younger-#artist is francisco goya-#artist is frederick sandys-#artist is john william waterhouse--#-artist is john william waterhouse#artist is evelyn de morgan#artist is hans baldung#artist is david teniers the younger#artist is luis ricardo falero#artist is edward henry corbould#witches#art history#art#arthistoryedit#artedit#general mythology

651 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello !! do u have any recommendations for books that demystify intelligence ? and/or historical analyses that pertain to its scientific construction ? I'm actually not picky at all, an extended reading list if you already have one available would be perfectly fine. I hope I'm being clear in my request bc English isn't my 1st language... if not, sorry

<3 bisou

for sure -- there's lots of writing about the historical context of IQ in particular, as well as other measures of 'intelligence' (binet-simon, galton, etc); there's also a lot of writing that's on specific national and regional contexts. so i'm not pulling anything close to an exhaustive list here lol but these are some i found at least somewhat helpful. im presuming you're a french speaker but if not just disregard the ones in french lol

The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould -- this is probably the no. 1 recommendation you will receive in english on this topic. it's not necessarily crucial if you've read other historical literature critiquing psychometry, but if not, it's a very solid text and is intended to be an easy entry point into the topic, so it can be a convenient place to start if you just need a leading-off point

‘The Intelligent and the Rest’: British Mensa and the Contested Status of High Intelligence (2020). Schregel, Susanne. History of the Human Sciences 33.5, 12-36. DOI: 10.1177/0952695120970029

Child prodigies in Paris in the belle époque: Between child stars and psychological subjects (2021). Graus, Andrea. History of Psychology 24.3, 255-274. DOI: 10.1037/hop0000192

Searching for South Asian Intelligence: Psychometry in British India, 1919--1940 (2014). Setlur, Shivrang. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 50.4, 359-375. DOI: 10.1002/jhbs.21692

La mesure de l'intelligence: Jeux des forces vitales et réductionnisme cérébral selon les anthropologues français (1860-1880) (1994). Blanckaert, Claude. Ludus Vitalis: Revista de Filosofía de las Ciencias de la Vida 2.3, 35-68

The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750--1940 (2007). Carson, John S. Princeton University Press, ISBN: 0691017158

Ambiguities of Racial Science in Colonial Africa: The African Research Survey and the Fields of Eugenics, Social Anthropology, and Biomedicine, 1920--1940 (2005). Tilley, Helen. In Science across the European Empires, 1800--1950 (ed. Stuchtey, Benedikt. Oxford University Press, ISBN: 0199276292), pp. 245–287

Ribot, Binet, and the Emergence from the Anthropological Shadow (2007). Staum, Martin S. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 43, 1-18

La mesure en psychologie de Binet à Thurstone (1997). Martin, Olivier. Revue de Synthèse 118, 457-493

W. E. B. DuBois, Anthropometric Science, and the Limits of Racial Uplift (2006). Farland, Maria. American Quarterly 58, 1017-1044

The Mismeasure of Minds: Debating Race and Intelligence between Brown and The Bell Curve (2018). Staub, Michael E. University of North Carolina Press, ISBN: 9781469643595

After Binet: French intelligence testing, 1900-1950 (1992). Schneider, William H. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 28, 111-132

Woman's Brain, Man's Brain: Feminism and Anthropology in Late Nineteenth-Century France (2003). Sowerwinea, Charles. Women's History Review 12, 289-308

#book recs#there may also be a list of a few articles (like journalism not academic articles) tagged as either 'academia' or 'lit and literacy'

224 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do we know the favorite books that the French revolution figures liked to read? (It could be anyone, Robespierre or Saint just or Louis xvi it doesn't matter).

Much like this old ask about revolutionaries’ favorite dishes, I can’t say I know of any instance of someone exclaiming: ”this is 100% my favorite book,” but at tops people mentioning books that they thought were good or bad:

In his memoirs, Brissot writes he’s picking up Rousseau’s Confessions for the sixth time, so I guess that could qualify as a favorite book? send help

We have this list of books seized at Robespierre’s place after his death.

According to the memoirs of Élisabeth Duplay, Robespierre would read ”the works of Corneille, Voltaire and Rousseau” for her family in the evenings.

In a short biography over Desmoulins written in 1834, Marcellin Matton claims his favorite book was René Aubert de Vertot’s Histoire des révolutions arrivées dans le gouvernement de la République romaine (1719), of which he always carried a copy. Matton is an infamous romanticizer it’s from him we have the stupid leaf myth for example, but I’m willing to give him some leeway here since he could have obtained the information from Camille’s mother-in-law and sister-in-law, who were his friends:

In one of his first classes, he received Vertot's Révolutions romaines as a prize. Reading this work transported him with admiration; in the future, he always had a volume in his pocket. It was for him an indispensable companion, it was his vade mecum. He used or lost at least twenty volumes. It is perhaps to this excellent work and to the particular work that he did on the discourses of Cicero and especially on his Philippics, that we owe the lively and sharp style which distinguishes all the writings coming from the pen of Camille .

Desmoulins was however less fond of Rousseau’s Confessions, in number 55 (December 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant he admits that he abandoned the book after getting infuriated by it:

Not that I idolize J.J. as I did in the past, since I saw in his Confessions that he had become an aristocrat in his old age. How far he was from looking at an Alexander with the pride of this Cynic, to whom he is compared, and how painfully I saw that he united the opposite faults of Diogenes and Arisippus! It is a pleasant thing to hear the author of the Social Contract protest in his Confessions about the simplicity of the commerce of such great lords (M. and Madame de Luxembourg) he cries with joy, he wants to kiss the feet of this good marshal, because he wanted to accompany one of his friends, an office clerk, for a walk. Is there anything smaller, more ridiculous? I received, he says elsewhere, the greatest honor that a man can receive, the visit of the Prince de Conti, (an honor that Rousseau shared with all the girls of the Palais-Royal.) At this point I tossed away the book out of spite, and I admit, that I had to reread the speech on equality of conditions, and Julie's novel, in order to not hate the philosopher of Geneva, like Durosoy and Mallet du Pan; for the same principles, in the mouth of such a great man, are more condemnable and worthy of aversion than in the mouths of our two gazetteers, whom God created poor in spirit, and predestined as such to the kingdom of heaven.

In a diary kept over the summer of 1788, Lucile Desmoulins mentions reading L’Âge d’Or (1782) by Sylvain Maréchal (of which she also copied two verses, Le Trésor and Le contrat de mariage devant la nature, in a notebook the year earlier), Les Idylles et poèmes champêtres (1762) by Salomon Gessner, L’Hymne au soleil, suivi de plusieurs morceaux du même genre qui n’ont point encore paru (1782) by Abbé de Reyrac (where she wrote down the verse La Gelée d’avril), Nouvelles lettres anglaises, ou Histoire du Chevalier Grandisson (1754) by Samuel Richardson and Les Noces patriarchales, poëme en prose en cinq chants (1777) by Robert Martin Lesuire.

In his memoirs, Buzot mentions enjoying the works of Rousseau and Plutarch:

With what charms I still remember this happy period of my life which can no longer return, when, during the day, I silently roamed the mountains and woods of the city where I was born, reading with delight some works of Plutarch or of Rousseau, or recalling to my memory the most precious features of their morality and their philosophy. Sometimes, sitting on the flowering grass, in the shade of some thick trees, I indulged, in a sweet melancholy, in the memories of the sorrows and the pleasures which had in turn agitated the first days of my life. Often the cherished works of these two good men had occupied or maintained my vigils with a friend of my age whom death took from me at thirty, and whose memory, always dear and respected, has preserved from many errors!

Wow any chance you can sound even more like an 18th century man stereotype, Buzot?

…and that’s basically all I can come up with for the moment. But add on if you know anything more! @louis-antoine-leon-saint-just @lazarecarnot maybe you would like to share your favorite books with us if you have any?

#frev#ask#robespierre#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#buzot#brissot#camille actually being the only sane person

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources on Louisiana Voodoo

door in New Orleans by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques

For better or worse, (almost always downright wrong,) Louisiana Voodoo and Hoodoo are likely to come up in any depiction of the state of Louisiana. I’ve created a list of works on contemporary and historical Voodoo/Hoodoo for anyone who’d like to learn more about what this tradition is and is not (hint: it developed separately from Haitian Vodou which now is the most visible form of Voodoo present in NOLA) or would like to depict it in a non-stereotypical way. I’ve listed them in chronological order, and bolder those works I consider the best, many of which are primary sources. Please keep a few things in mind. Almost all sources presented unfortunately have their biases. As ethnographies Hurston’s work no longer represent best practices in Anthropology, and has been suspected of embellishment and sensationalism on this topic. Additionally, her portrayal is of the religion as it was nearly 100 years ago- all traditions change over time. Likewise, Teish is extremely valuable for providing an inside view into the practice, but certain views, as on Ancient Egypt, may be offensive now. I have chosen to include the non-academic works by Alvarado and Filan for the research on historical Voodoo they did with regards to the Federal Writer’s Project that is not readily accessible, HOWEVER, this is NOT a guide to teach you to practice this closed tradition, and again some of the opinions are suspect- DO NOT use sage, which is part of Native practice and destroys local environments. I do not support every view expressed, but think even when wrong these sources present something to be learned about the way we treat culture.

*To compare Louisiana Voodoo with other traditions see the chapter on Haitian Vodou in Creole Religions of the Caribbean by Olmos and Paravinsi-Gebert. Additionally, many songs and chants were originally in Louisiana Creole (different from the Louisiana French dialect), which is now severely endangered. You can study the language in Ti Liv Kreyol by Guillery-Chatman et. Al.

Le Petit Albert by Albertus Parvus Lucius (1706) grimoire widely circulated in France in the 18th century, brought to the colony & significantly impacted Hoodoo

Mules and Men by Zora Neale Hurston (1935)

Spirit World-Photographs & Journal: Pattern in the Expressive Folk Culture of Afro-American New Orleans by Michael P. Smith (1984)

Jambalaya: The Natural Woman's Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish (1985)

Eve’s Bayou (1997), film

Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce by Carolyn Morrow Long (2001)

A New Orleans Voodoo Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau by Carolyn Morrow Long (2006)

“Yoruba Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo” by Ina J. Fandrich (2007)

The New Orleans Voodoo Handbook by Kenaz Filan (2011)

“Why We Can’t Talk To You About Voodoo” by Brenda Marie Osbey (2011)

Mojo Workin': The Old African American Hoodoo System by Katrina Hazzard-Donald (2013)

The Tomb of Marie Laveau In St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 by Carolyn Morrow Long (2016)

Lemonade, visual album by Beyonce (2016)

How to Make Lemonade, book by Beyonce (2016)

“Work the Root: Black Feminism, Hoodoo Love Rituals, and Practices of Freedom” by Lyndsey Stewart (2017)

The Lemonade Reader edited by Kinitra D. Brooks and Kameelah L. Martin (2019)

The Magic of Marie Laveau by Denise Alvarado (2020)

In Our Mother’s Gardens (2021), documentary on Netflix, around 1 hour mark traditional offering to the ancestors by Dr. Zauditu-Selassie

“Playing the Bamboula” rhythm for honoring ancestors associated with historical Voodoo

Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans 1880-1940 by Kodi A. Roberts (2023)

The Marie Laveau Grimoire by Denise Alvarado (2024)

Voodoo: An African American Religion by Jeffrey E. Anderson (2024)

#I’ll continue to update as I find more sources#Please be respectful of other people’s religion#Louisiana Voodoo#In the case of authors behind a paywall or whom you do not wish to support I highly recommend your local library#Voodoo#some consider voodoo/hoodoo diff today but this may not always have been the case historically so they have been presented together here

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few months ago, I had an anon request for Averyjameson headcanons about them spending time at True North for the holidays so here we are.

They arrive earlier than everyone else so they have a few days to themselves.

Jameson continues Avery's skiing lessons, teaching her a few tricks and some riskier ones when no bodyguards are around. Avery notices that he likes holding her waist a lot when he's teaching her a maneuver, sometimes longer than needed but she pretends she doesn't and secretly likes it when he does.

One day, they sneak out out of the lodge for an early morning game of Drop. Surprisingly, for her first time, Avery wins and manages to come back with barely a few scrapes compared to a certain someone. Jameson is all too happy, even if he's lost, but spends the rest of the day in bed or out in the hot tub with Avery tending to his wounds and giving him a kiss to the cheek.

When they're out on the trails, Jamie will sometimes sneak behind a tree, tug Avery along with him and have a quick make out sesh.

Before they come back in, both their faces are flushed red from the cold but Avery gets especially flushed, Jameson likes to pepper kisses along her cheeks and finish with a peck on her bright red nose. He calls her his Red-Nosed Reindear (cue eyerolling from his girlfriend).

They love to spend their evenings in front of the hearth wearing matching pjs and watching cheesy Hallmark movies. Jameson is actually a big sucker for them; it's his trash comfort.

Jameson makes hot chocolate and it's pretty amazing. It's his favorite holiday drink, as basic as it is. Avery doesn't judge him one bit for it but she prefers eggnog a little more.

Although they use the hot tub together, Avery has reverted to one piece bathing suits, she still isn't that comfortable in bikinis unless she has a pair of swim shorts on. Jameson is completely miffed by this as he really wants to see her in one again and even went so far as to sneak a red pair in her suitcase when she wasn't looking. She still hadn't put it on and he thinks maybe she hadn't found it (she has and knows that she didn't pack it but knows who did).

Throughout the holidays, he puts up a bunch of mistletoe and tries to catch her under it but ends up having to remove it because turns out, Libby is allergic.

For Christmas, Avery sets up a scavenger hunt for him to complete in order to find his present from her. It proves to be a bit difficult since they spend so much time together but when he's out on a solo ski, she takes a chance to hide another clue.

Jameson is ecstatic and pulls Avery along while he goes hunting, she merrily laughing at his antics. With every clue he finds, her smile gets bigger and bigger.

His gift from her is a card, the keys to the Chiron and tickets to the 24 Hours of Le Mans race in France for the following year. She also secured a personal day with the Aston Martin F1 team for him to participate with in training.

Her gift from him is a locket and bracelet set and a month of pottery classes since she's been wanting to actually try something new but keeps forgetting and because she's been very busy with work. He also got her a signed book series she'd been eyeing.

For New Year's, he surprises her with a visit from Toby.

At midnight, when they're about to drink spirits, she gifts him with a bottle of Jameson, laughing. He simply rolls his eyes.

They also do something similar to the Countdown Party in TFG, except, after midnight. For the first hour, they celebrate the New Year but after, they're a flurry doing all the most craziest things around the lodge; snowboarding at 1:00, drop challenge into the hot tub at 2:00, karaoke battle at 3:00, snowball fight in swimsuits at 4:00, reindeer sleighride at 5:00, etc.

Both of them get sick the following week and Nash is playing nurse because he was the only sensible one to not participate in Hour 4.

I hope you had fun reading. Stay tuned for a Christmas party fanfic with our favorite duo and fake dating Averyjameson au featuring a hot tub during the winter break story.

#avery kylie grambs#avery grambs#jameson winchester hawthorne#jameson hawthorne#averyjameson#true north#hawthorne shenanigans#hawthorne headcanons#the inheritance games#the hawthorne legacy#the final gambit#tig#thl#tfg

68 notes

·

View notes

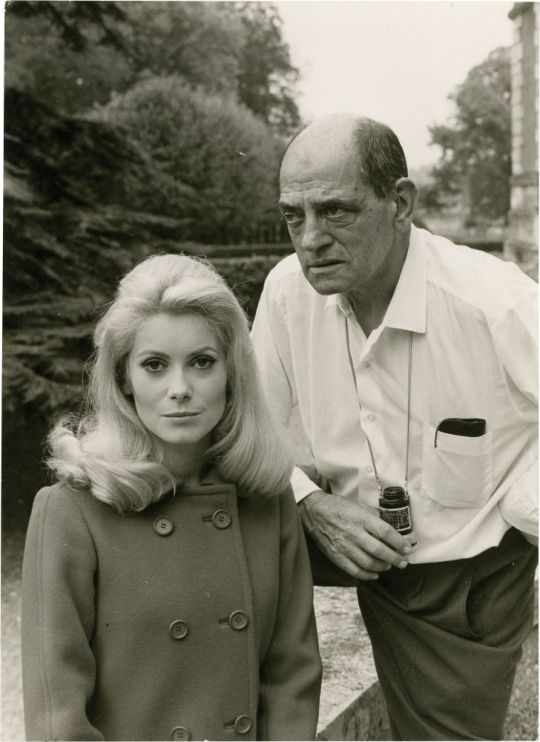

Photo

C'est fou comme les gens ont de moi cette image de femme sophistiquée, glaciale. C'est une telle erreur, c'est tellement mal me connaître.

- Catherine Deneuve on herself in Belle de Jour (1967)

In anticipation of a new film this summer by Catherine Deneuve called ‘Bernadette’ where she plays Bernadette Chirac, the wife of French Jacques Chirac, I’ve been re-watching some her back catalogue of films. She’s done over 64 films and at almost 80 years old she’s still going strong. And yet out of her many films I’ve always been drawn back to one film which has become a cult classic. Watching it and re-watching it and even gorging on books on its making, new intriguing details reveal themselves about this landmark French art house classic - Belle de Jour (1967).

I once had the privilege of having dinner with her - or rather sat around the same table - through a Parisian host and his lovely wife who had gathered an eclectic group of friends across generations together. I was too self-conscious to talk about her film career directly. I was on surer ground when we indulged in small talk where she was perfectly down to earth and very pleasant. I felt it would be rude to go all fan girl on her and pepper her with questions about Belle de Jour in particular as she’s known to be very ambivalent about her experience of the film - a film that really defined her in the eyes of many people.

But it didn’t mean she didn’t recognise its cultural importance though as she was quite happy to amuse us with a funny story about Belle de Jour. A newly restored 35mm version was funded by the fashion house Saint Laurent back in 2018. Deneuve always had a close relationship with Yves Saint Laurent and also the fashion house. She was the one to introduce Buñuel to Saint Laurent. So the fashion house had a glitzy premiere in New York. But they didn’t count on many of their guests being late. Most of the guests were stuck in the New York traffic and the rain. However Martin Scorsese was the only one to get out of cab and run like a mad man through the pelting rain and huge traffic. A true cinephile, he was so desperate to see the film restored to its former glory that he would go to any lengths to see it.

In Belle de Jour, Catherine Deneuve, whose limpid beauty is capable of sustaining any interpretation, is a perfect Severine and demonstrates a remarkable control in progressing, with enormous economy of gesture and movement, from frigidity to physical warmth as the bored housewife who indulges in part time sex work.

“I felt they showed more of me than they’d said they were going to,” Catherine Deneuve remarked to Pascal Bonitzer in 2004, about the making of Luis Buñuel’s 1967 Belle de jour. “There were moments when I felt totally used. I was very unhappy.”

The story of Séverine, a deeply disenchanted haute bourgeois Paris housewife who finds erotic liberation through byzantine psycho-sexual fantasies and part-time work at an upscale brothel, Belle de jour certainly made extreme demands of Deneuve: her character is flogged, raped, and pelted with muck, among other assaults. But despite her objections to the way she was treated and her difficulties with Buñuel, Deneuve’s performance in Belle de jour turned out to be one of her most iconic.

Deneuve, who had become a star only three years earlier, as the melancholy jeune fille in Jacques Demy’s 1964 all-sung musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, was just twenty-three when Belle de jour came out; notably, Buñuel’s film was released in France less than three months after Demy’s radiant, MGM-inspired musical The Young Girls of Rochefort, starring Deneuve and her real-life sister Françoise Dorléac.

But Belle de jour, more than any other film from the first decade of her career, defined what would become one of the actress’s most notorious personae: the exquisite blank slate lost in her own masochistic fantasies and onto whom all sorts of perversions could be projected. (Deneuve as deviant tabula rasa was first seen in Roman Polanski’s 1965 Repulsion, in which she plays a damaged beauty plummeting into psychosis; but Belle de jour doesn’t portray its heroine as mad, instead remaining deliberately ambiguous about the origins of her unconventional desires - and presaging the bizarre libertines she would later play in such films as Marco Ferreri’s Liza, 1972, and Tony Scott’s The Hunger, 1983.)

Buñuel was at a very different stage of his career from his young star, but Belle de jour represented a peak for him as well, the greatest - and most successful - film of his extremely rich late period. These works, bookended by 1964’s Diary of a Chambermaid and 1977’s That Obscure Object of Desire (his final film), were made mostly in France - where Buñuel had begun his filmmaking career with the incendiary, surrealist Un chien andalou (1929) - following the exiled Spanish director’s two decades in Mexico.

Many of these late projects were cowritten with Jean-Claude Carrière and focus intensely on sexual perversion (a theme that recurs throughout Buñuel’s work). Belle de jour certainly falls into that category, and also, typically, skewers the entitled classes. Yet it stands out as the director’s most intricate character study—but of a protagonist who resists definition; the heroine, frequently trussed up and mussed up, retains an odd, opaque dignity in her debauchery.

In that same interview with Bonitzer, Deneuve was judicious enough to distinguish her experience of making Belle de jour from the final product, calling it a “wonderful film.” But her first meetings with Buñuel hinted at the duress that was to follow. According to John Baxter’s 1994 biography, Buñuel, it took time for the director to “warm to” his star: “He felt, with some justice, that she had been foisted on him, first by the Hakims [Belle de jour’s producers], then by her lover of the time, François Truffaut.” After dining with Buñuel at his house, the book recounts, Deneuve “left with little more than an impression that he disliked actors in general and was reserving his decision about her. The only advice he offered was the advice he had always given actors: ‘Don’t do anything. And above all, don’t . . . perform.’”

Though Deneuve deferred to her director, she was no puppet; Belle de jour is as much hers as Buñuel’s. The filmmaker, famously resistant to “psychological” interpretations of his work, stuffs Belle de jour with his trademarks, confounding any attempt to parse meaning: the surrealist blurring of fantasy and reality, fetishism, sexual perversion, blasphemy.

But as Séverine, Deneuve, despite operating in the nebulous realm between dream and waking, imbues the film with irresistible and very real lust - and luster. Sporting the chicest Yves Saint Laurent finery, Deneuve revels in the peculiar desires of her character while always inviting our own. As Buñuel himself acknowledges in his 1984 autobiography, My Last Sigh (published a year after his death), Belle de jour “was my biggest commercial success, which I attribute more to the marvelous whores than to my direction.” (Per Baxter, after the filming of Belle de jour, he would finally admit of his star, “She’s really a very good actress.”) Deneuve’s gift was to update the world’s oldest profession for her still-expanding résumé.

The director had some modifying to do as well. Buñuel, who adapted Joseph Kessel’s 1928 novel with Carrière, assessed the source material dryly in My Last Sigh: “The novel is very melodramatic, but well constructed, and it offered me the chance to translate Séverine’s fantasies into pictorial images as well as to draw a serious portrait of a young female bourgeois masochist. I was also able to indulge myself in the faithful description of some interesting sexual perversions.”

He wastes no time in establishing those bizarre erotic proclivities. In Belle de jour’s opening scene, Séverine and her doting husband of one year, Pierre Serizy (Jean Sorel), a handsome, dutiful surgeon, are snuggled close in a horse-drawn carriage; he interrupts the tender moment with the lament “If only you weren’t so cold.” She pulls away, defensive. The sound of horse bells, which has been increasing in volume from the film’s first shot - and will indicate Séverine’s dreams or fantasies throughout - stops. Pierre orders his wife out of the cab; when she refuses, he and the two drivers remove her by force. She is gagged, bound to a tree, and whipped by the coachmen, who are then instructed by Pierre to rape her. When one begins to ravish her, Séverine appears to be in ecstasy.

This carnal reverie is soon interrupted by the Serizys at home, preparing for their usual chaste bedtime ritual. Pierre, in white pajamas, asks his pale-pink-nightie-clad wife, under the covers in a separate bed, what she’s thinking about: “I was thinking about you . . . and us. We were out for a ride in a carriage”—a scenario Pierre has heard before.

The fantasy clearly belongs to Séverine alone; she finds erotic thrills in her secret thoughts of debasement and humiliation, her florid imagination compensating for her sterile, sexless existence. Her most private desires will soon be realized at 11, cité Jean de Saumur, the address of the boutique bordello run by Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page), given to Séverine by Pierre’s louche friend Husson (Michel Piccoli).

At Madame Anaïs’s, Séverine - now going by the nom de pute Belle de jour, a reference to her two-to-five shift (she insists on being home when Pierre returns from his workday at the hospital) - is horrified at first but proves to be a quick study. A burly Asian client scares off her two seasoned colleagues with his mysterious, buzzing lacquered box, but she is absolutely transfixed; after the john leaves, she, lying prone on the bed, lifts her head, her luxuriant mane of blonde hair disheveled, to reveal a woman still drunk on orgasmic pleasure.

The contents of the box are one of the film’s many mysteries (when asked what is inside, Buñuel would reply, “Whatever you want there to be”). Yet the greatest enigma is Séverine herself: why does she recoil from the slightest sexual advance from her husband yet lose herself, both in fantasy and in her new line of work, in elaborate masochistic tableaux? “Pierre, it’s your fault too. I can explain everything,” Séverine insists to her husband in the opening fantasy sequence, as she’s being forcibly removed from the landau. But of course, she can’t - and won’t.

As in Repulsion, there are flashbacks to possible childhood trauma in Belle de jour. In one, a man appears to touch a young Séverine inappropriately; in another, she stubbornly refuses the Blessed Sacrament. But unlike in Repulsion, whose final, prolonged shot of a menacing family photo is offered as the root of Carole’s pathology, these scenes in Buñuel’s film are almost non sequiturs, presented not as psychological explanation but as blips in a baroque sexual surrealism.

As Séverine’s reveries and job demands become stranger and more mysterious - in one daydream, she is pelted with thick black mud by Pierre and Husson, who call her “tramp” and “slut”; a ducal client solicits her in the bois de Boulogne to perform in a necrophilic rite - Deneuve retains her porcelain, celestial inscrutability, while simultaneously transforming into an earthbound debauchee, delighting in her own defilement. Madame Anaïs (whose early, shameless flirtation with Séverine - who eventually reciprocates - is the first of the many moments in Deneuve’s filmography that would cement her status as a lesbian icon) touts her new employee’s regal bearing to prospective customers: “[She’s] a little shy, perhaps, but a real aristocrat.”

Séverine’s coworkers, Charlotte (Françoise Fabian) and Mathilde (Maria Latour), are constantly remarking on the impeccable cut and style of her ensembles. Yet what this seemingly untouchable goddess craves most is the brutality of her latest john, the thug Marcel (Pierre Clémenti), a rough with metal teeth, a walking stick that doubles as a shiv, and fetishwear (shiny boots of leather with matching overcoat) that could have been dreamed up in an atelier overseen by Kenneth Anger and Pierre Cardin.

Séverine’s relationship with Marcel will lead to Pierre’s ruin - or does it? The ambiguous ending of Belle de jour suggests that everything that preceded it may have existed only in the heroine’s cracked dreamscape. Like the buzzing box, the film’s final scene is whatever you want it to be.

Yet one thing is certain: Deneuve transcends kink. And despite her misery during the Belle de jour shoot, she would return for even more bizarre treatment three years later in Buñuel’s Tristana, losing both her virtue and a leg.

Almost 55 years after it was made Belle de Jour continues to be a compelling film. It takes on greater curiosity for me as I live in Paris and there are Séverines aplenty that I come across. But the film also speaks to a non-French audience even today as it remains a shrewd commentary on the hypocrisy of social relations and sexual politics. Buñuel invites us to ponder the transgression of a socially respectable woman secretly being a prostitute in the afternoons, but I don’t think he bothered to pose the question why a socially respectable gentleman should be secretly visiting a prostitute in the afternoons - which happens more than one might think and that behaviour is normalised. Something to think about.

#deneuve#catherine deneuve#quote#french#film#movie#cinema#belle de jour#actress#luis bunuel#bunuel#film making#arts#culture#france#scorsese#personal#paris

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

les mis and Ninety-Three are connected and this totally influences the fate of the characters!

Guys, please read this entire theory! EVERY detail is important! First of all, you need to know that Ninety-Three was Victor Hugo's last book, so he already had access to ALL the references present in the previous books! the character Gauvain has similarities with the character Enjolras, Michelle has similarities with Fantine and Cimourdain has similarities with Javert!

the book Ninety-Three was CREATED TO BE PART OF A TRILOGY THAT INCLUDED THE MAN WHO LAUGHED AND ANOTHER BOOK that was never written! The preface of The Man Who Laughs announces the future release of Ninety-Three!

L’HOMME QUI RIT

De l’Angleterre tout est grand, même ce qui n’est pas bon, même l’oligarchie. Le patriciat anglais, c’est le patriciat dans le sens absolu du mot. Pas de féodalité plus illustre, plus terrible et plus vivace. Disons-le, cette féodalité a été utile à ses heures. C’est en Angleterre que ce phénomène, la Seigneurie, veut être étudié, de même que c’est en France qu’il faut étudier ce phénomène, la Royauté. Le vrai titre de ce livre serait l’Aristocratie. Un autre livre, qui suivra, pourra être intitulé la Monarchie. Et ces deux livres, s’il est donné à l’auteur d’achever ce travail, en précéderont et en amèneront un autre qui sera intitulé: Quatrevingt-treize. Hauteville-House, 1869.

it is necessary to know Victor Hugo's lover: Julienne Josephine GAUVAIN, also known as Juliette Drouet! YES, she inspired the name of the noble family featured in the book Ninety-Three!

Now check this out! I'M SURE you'll be impressed

Les miserables vol 2 cosette book sixth - Le petit picpus chapter VII- some silhouettes of this darkness

The most esteemed among the vocal mothers were Mother Sainte-Honorine; the treasurer, Mother Sainte-Gertrude, the chief mistress of the novices; Mother-Saint-Ange, the assistant mistress; Mother Annonciation, the sacristan; Mother Saint-Augustin, the nurse, the only one in the convent who was malicious; then Mother Sainte-Mechtilde (Mademoiselle GAUVAIN), very young and with a beautiful voice; Mother des Anges (Mademoiselle Drouet), who had been in the convent of the Filles-Dieu, and in the convent du Trésor, between Gisors and Magny; Mother Saint-Joseph (Mademoiselle de Cogolludo), Mother Sainte-Adélaide (Mademoiselle d’Auverney), Mother Miséricorde (Mademoiselle de Cifuentes, who could not resist austerities), Mother Compassion (Mademoiselle de la Miltière, received at the age of sixty in defiance of the rule, and very wealthy); Mother Providence (Mademoiselle de Laudinière), Mother Présentation (Mademoiselle de Siguenza), who was prioress in 1847; and finally, Mother Sainte-Céligne (sister of the sculptor Ceracchi), who went mad; Mother Sainte-Chantal (Mademoiselle de Suzon), who went mad.

This nun with the surname Gauvain will be mentioned again! (did you notice that she has a small highlight?)

les miserables volume iv Saint Denis book fourth succor from below may turn out to be succor from on high chapter i A wound without, healing within

Sister Sainte-Mechtilde had taught Cosette music in the convent; Cosette had the voice of a linnet with a soul, and sometimes, in the evening, in the wounded man’s humble abode, she warbled melancholy songs which delighted Jean Valjean.

You might think it was just a tribute from Victor Hugo to his beloved, but what if I told you that it makes sense that this nun is related to two characters present in Victor Hugo's last book!

Les miserables volume ii cosette book sixth— le petit-picpus chapter III— austerities

One is a postulant for two years at least, often for four; a novice for four. It is rare that the definitive vows can be pronounced earlier than the age of twenty-three or twenty-four years. The Bernardines-Benedictines of Martin Verga do not admit widows to their order.

This shows that she is not a Gauvain through marriage but rather a Gauvain by birth! To be a Gauvain by birth she needs a Gauvain father! So her father is either the Viscount Gauvain or the Marquis de Lantenac!

Gauvain était-il amoureux ? Oui. De miséricorde. Faire grâce était son idéal. Pas de femme. Il semblait qu’il n’eût qu’une pensée dans ces temps terribles : attendrir la guerre civile

This deleted scene shows that Gauvain could only have married due to social pressure!

Being Gauvain's daughter, the nun could be at least 30 years old during the events of Les Misérables, it turns out that Victor Hugo describes her as very young, “her father” Gauvain is also described as young at that age…

In this part of the book Ninety-Three! we see that Lantenac has several candidates for his wife!

C’était un homme à femmes avant d’être un homme de guerre.

Remember that men can be fathers at any age! Check out the list of the oldest fathers in history! remember that Lantenac needed an heir after what happened to Gauvain!

Whether he was a father or not, Lantenac knew this girl! AND HE LIVED AT PETIT PICPUS! Yes! I'll show you how sure I am of that!

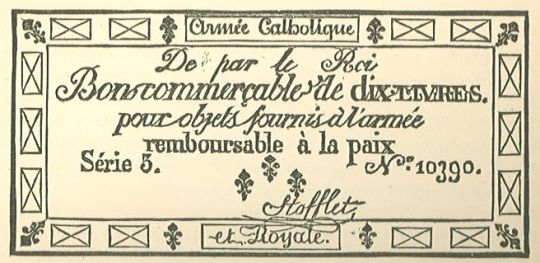

Les miserables volume ii Cosette book eighth— cemeteries take that which is committed them chapter IX—CLOISTERED

The walls of this chamber had for ornament, in addition to the two nails whereon to hang the knee-cap and the basket, a Royalist bank-note of ’93, applied to the wall over the chimney-piece, and of which the following is an exact facsimile:—

This specimen of Vendean paper money had been nailed to the wall by the preceding gardener, an old Chouan, who had died in the convent, and whose place Fauchelevent had taken.

Yes, the nuns know about Lantenac's past… and did you know that they paid homage to him when choosing Mademoiselle Gauvain's name as a nun? Saint Mechtilde was a saint known for her musical talents and her relationship with the Sacred Heart and Jesus (Chouan symbol)

I'm reading an excellent book by a Pullitzer Prize winner: The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo! I LOVE Alexandre Dumas and I think everyone should read his books and get to know his works! I think these excerpts from the book justify the nuns' view

I started researching the Vendee War and both books after reading this biography about Alexandre Dumas' father!

In your opinion, who is this nun's father?

so there are two options: she is the daughter of the Marquis de Lantenac and second cousin of Gauvain or she is the daughter of Gauvain and the Marquis is her arrière-grand-oncle (I don't speak French so correct me if I'm wrong!)

#Les mis#cosette#jean valjean#Ninety-Three#Fauchelevent#Les miserables#Quatrevingt-treize#Lantenac#Gauvain#Ninety Three#Quatrevingt treize#Les Misérables#victor hugo#The brick#cosette fauchelevent#Cosette les mis

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART - BIOGRAPHY -

Discouraged by the parsimony of the Emperor, failing to become teacher to Princess Elizabeth, and feeling unappreciated, Mozart decided to leave Vienna for France and England. At that time, he was known in Vienna primarily as a pianoforte player; only after the appearance of the "Magic Flute" was he recognized as a great operatic composer—but by then it was too late. Leopold opposed his son's plans and even wrote to the Baroness von Waldstädten to reason with him, adding, "What is there to prevent his having a prosperous career in Vienna if he only has a little patience?" Mozart thus stayed, giving lessons, concerts in the Augarten, and performances in the theatre and various halls, where his concertos and playing were highly successful. His old love Aloysia sang, and Gluck applauded from a box.

Mozart's subscription concerts were crowded, and he earned well. Yet, despite these successes, he struggled financially. Lacking business sense, he was often short on money and regularly borrowed small sums to pay off debts. Attempts at reform, such as keeping an account book from March 1784 to February 1785, proved ineffective. Constanze was not an efficient housewife, and financial troubles persisted.

In 1783, a son was born and died the same year; that summer, they visited Salzburg, where Mozart fulfilled a vow by performing a mass and wrote duets to aid Michael Haydn, who was ill. The visit, however, disappointed Mozart, as his family showed little fondness for Constanze, and trinkets from his youth weren’t offered to his wife. In 1785, Leopold visited Vienna, where he wept with joy at Wolfgang’s performance and heard Haydn proclaim Mozart as "the greatest composer I have ever heard."

Mozart became a Freemason, influenced by the era’s secret societies promoting liberty of conscience and independence of thought. With his humanitarian ideals, Mozart entered eagerly into masonic ties, contemplating his own secret society and writing for his lodge, Zur gekrönten Hoffnung. His masonic "Trauermusik" remains celebrated for its beauty and originality.

In 1784, the German opera in Vienna was almost extinct. For her benefit, Aloysia Lange chose Mozart's "Escape from the Seraglio" and the composer directed it; productions like Gluck's "Pilgrimme von Mekka" and Benda's melodramas followed. By 1785, there was an attempt to revive German opera to compete with Italian opera, but the performances did not match the Italian standard. Unfortunately, Mozart was not pitted against Salieri by the Emperor, who favored foreign talent.

In 1786, German and Italian dramatic performances were ordered for a festival; Mozart wrote the music for "Der Schauspieldirector" (The Theatre Director), while Salieri received a better text. The Italian operas continued to thrive among court and public alike, drawing many of the best singers.

Mozart’s prospects in opera looked bleak until he met Lorenzo da Ponte in 1785. Da Ponte, an abbé and theatrical poet, had a falling out with Salieri and sought a new composer to rival his benefactor. Mozart desired an adaptation of Beaumarchais' comedy, "Le Mariage de Figaro", then popular on the French stage, though the comedy itself was banned in Vienna. Da Ponte used his influence to confide the plan to Emperor Joseph, who, though he questioned Mozart's operatic skill, agreed to hear parts of the work and ordered its rehearsal.

The entire opera was reportedly completed in six weeks despite a cabal led by Salieri against its success. Yet on May 1, "Figaro" premiered to overwhelming acclaim. Michael Kelly, who played Basilio and Don Curzio, recorded that "Never was anything more complete than the triumph of Mozart." During subsequent performances, several pieces were repeated multiple times, with some performed as many as three times in a single night. However, in November, Martin's "Cosa Rara" captivated the public’s shifting interests, and "Figaro" saw reduced performances by 1787. The opera later gained fame across Europe and inspired Mozart's next masterpiece, "Don Giovanni," after an immediate success in Prague.

The success of "Figaro" did not bring material benefits to Mozart in Vienna. Frustrated by teaching and with few prospects, he considered going to England until he received a letter from Prague’s orchestra, inviting him to witness "Figaro's" enormous success there. In January 1787, Mozart arrived in Prague with Constanze, welcomed warmly by Count Thun. He saw Prague’s enthusiasm for "Figaro" everywhere—in streets and concert halls alike, where even chamber arrangements of the opera were played and sung. After two successful concerts, Mozart’s happiness was capped by a contract for a new opera with Bondini.

Mozart immediately thought of Da Ponte for a libretto, and Da Ponte suggested "Don Giovanni"—a tale already adapted by writers like Molière and composers such as Gluck and Righini. Working between stories and with Mozart’s libretto in sixty-three days, Da Ponte’s productivity was matched only by Mozart’s own dedication to the score. Though Mozart’s father had died in May, causing him grief, he poured his efforts into "Don Giovanni" while in Prague. Stories about his methods and behavior—including the overture, reportedly unwritten until the evening before the premiere—paint a vibrant, though speculative, picture of his time there.

The Prague premiere on October 29, 1787, was a triumph. Shortly after returning to Vienna, Mozart was appointed Chamber Musician by Emperor Joseph following Gluck's death. Yet "Don Giovanni" initially struggled in Vienna; the Emperor said it would be a challenge for his Viennese. Mozart, undeterred, remarked, “We will give them time to chew it.” Eventually, the opera’s influence grew across Berlin, Paris, and London, and by 1825, it even reached New York through the efforts of Garcia and Da Ponte. In time, "Don Giovanni" was seen as Mozart’s masterpiece, with the composer reportedly admitting he wrote it “not at all for Vienna, a little for Prague, but mostly for myself and friends.”

Thank you FB @ Alex Rosas Navarro

NOTE: Here in this biographical account we see Salieri in active opposition to Mozart on more than one occasion, which would lead one to conclude that where there is smoke, there is fire, as far as the antagonism that existed between Mozart and Salieri.

#mozart#a classical life#classical music#art#18th century#classic#classical history#classical art#classical musician#classical composer#classical#biography#mozart and salieri

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Mother Goose's fairytales switched from adults to children

I have frequently talked about how printed fairy tales were always originally meant for adults, not children.

The fairytales of Charles Perrault and madame d'Aulnoy in France were for an adult audience and adult in tone and content (with illusions of "childishness" as a narrative convention), and only later became stories for children due to a mass-spreading, an access to popular culture and a misinformation about their purpose. Before them, the first "fairytale collections" of Basile and Straparola, the "Pentamerone" and "The Facetious Nights" are very obviously for adults due to their nature as NSFW dark comedy filled with sex, rape, gore, scatophilia and Punch-and-Judy humor. Even in the case of the brothers Grimm! The first edition of the brothers' fairytale collection was for a purely scientific, cultural, folkloric purpose - it was meant to be read for scholars and folklorists and other adults. It was only as they realized that their book turned out to be a huge best-sellers for families, and that it was most often used as a way to entertain children, that they decided to make their stories more "kid-friendly". Hence why each re-edition of their collection became more "SFW" and more edited (they even made a side-book, a mini-collection of fifty edited fairytales specifically selected for children!)

This is the long history of fairytales. Each time prepared by adults, for adults, and yet ending up in the hands of children and being treated as for kids... And since the cosmos loes balance, now that the fairytales are throoughly ingrained and defined as "for children", they always end up being reimagined and renvented for an adult audience... Anyway.

The reason I bring back this entire topic is because I recently stumbled upon an article about Martine Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère, about the adaptations of Perrault's "Les Fées" (The Fairies, better known today as "Toads and Diamonds") for England. It was quite an interesting read so I will share some of its content below, rearranged a bit with additional info (such as the one above).

First off, it should be noted that, from the get go, when fairytales of France were first translated in England, the idea that they were for adults was still around. For example the very first literary fairytale of France, L'île de la félicité, by madame d'Aulnoy, was translated as early as 1691 - because the novel which contained it was translated, "The History of Adolphus", and since it stayed within its original context, it stayed an "adult read" (since the novel was a story for adults). [For more information about it, check M.D. Palmer's text "The History of Adolphus, the first French Conte de fée in English")

This doesn't come from the article I talked about, but in another paper about the European fame of madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales in the 18th and 19th centuries, there was this precision that the same way in England Charles Perrault's name was overshadowed by the one of the fictional "Mother Goose", madame d'Aulnoy's own name was erased for a nickname seemingly coming out of nowhere: "Mother Bunch". Just a desire to match the other famous "fairytale mother"? Not quite... Because the name "Mother Bunch" was associated in England with a specific type of woman - the type of woman who knew more private, romantic, erotic secrets, the kind of woman teenagers would go to to ask advice on how to seduce other people, and young couples would question about how things were meant to go in bed. A kind of Nanny Ogg, if you know your Discworld. A saucier "Mother Goose". It was probably not because the English audience perceived the subversive, erotic and bawdy elements within madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales, unfortunately ; but it was mostly due to England being aware of the various scandals and extravagant adventures madame d'Aulnoy lived, which gave her a reputation of a quite unconventional woman.

The real "turn", the true switch within a general perception of these fairytales was probably the first real translation in English of Charles Perrault's fairytales: Robert Samber published in 1729 "Histories, or Tales of Past Times... with Morals by M. Perrault". This was the original sin, so to speak. Because you see... Robert Samber meant this book to be for children and he did not hide it.

As I repeatedly said before, Charles Perrault's fairytales were not meant for children. He did imitate a simplistic story-style associated with children stories ; he did include morals at the end of each of his tales... But his intended audience (and test audience, and those he dedicated the stories to) was made of adults, his morals were all ironic and subversive, and his stories were filled with puns and references only an adult person (and more so an adult person of a certain social condition living by or near the royal court) would understand. But Robert Samber? He made a huge effort to highlight how Perrault's fairytales were moral - like, literaly, he took every Moral of Perrault at first-degree, as praising virtue and denouncing vice, completely missing the jokes and incoherences within it - and were "educational". And perfect for children. In fact, Robert Samber dedicated his translation to the children of a certain lord Carteret. Bear this in mind, it will come back later.

A clear and obvious proof of Samber literaly falsifying the text to fit his personal perception is the preface of his translation. He did translate most of Perrault's own preface for his fairy tales... But he included in it extracts from another preface. The preface of Jean de la Fontaine's Fables. An extract about how Plato praised the fables of Aesop when it came to teaching children about wisdom and virtue, and how he advised people to prefer them to the "poetry of Homer" (the Iliad, the Odyssey, etc). Not only did Samber literaly took the words of a different author for a different work and grafted them here... But when you are aware of the context, it becomes even more extravagant.

I spoke regularly about this, but the fairytales of France took place within a cultural battle known as "La Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes". On one side, the "Ancients", people then in charge of the dominating cultural institutes, and who held the long tradition that any cultural piece worth anything had to come from the classical and "perfect" era of the Greek and the Romans. On the other side, the "Modern", a new generation of culture-makers who claimed that other sources and other influences could be used rather than Antiquity - more "modern" resources such as the various romances and epics of the Middle-Ages. La Fontaine and Perrault were not bitter enemies at all - in fact, Perrault greatly admired La Fontaine and references his Fables within his own fairytales... But they stood on opposite sides of the schism. La Fontaine was part of the Ancients - hence why his most famous work was the Fables, a French adaptation of Aesop's own fables and other Antique stories "recreated" for Renaissance France. Perrault, meanwhile, was the unofficial leader of the Moderns - hence why he created his fairytales, inspired by French folklore rather than any Greek epic or Roman tragedy. As such, to confuse the explanation-texts of these two authors isn't just falsifying a translation - it is literaly fusing and reinventing two conflicting and contradicting opinions about the use and format of culture. And it completely falsifies Perrault's own initial project and intentions. (Plus it perpetuates a confusion between "fables" and "fairy tales")

Not only that, but Samber also removed several key sentences from Perrault's preface. Including those that explicitely said that his fairy tales could be read differently depending on the age and the level of experience of the reader... A subtle way to point out the obvious: under an apparently simplistic and childish folk-story was hidden an adult literary work. But again, for a Samber taking literaly every one of Perrault's Morals and aiming a book for children and only children, such sentences had to be removed.

Another fascinating element... In his preface, Robert Sambre points out that the fairytales within his book are organized in a pedagogical way, from the most childish to the most mature. Another "proof", according to him, of why this book was made for children. Problem... Robert Sambre used a Dutch print of the fairytales, a 1721 Amsterdam edition which completely changed the order of the fairytales. Perrault's original order, in the 1697 edition, was: Sleeping Beauty - Little Red Riding Hood - Bluebeard - Puss in Boots - Toads and Diamonds - Cinderella - Riquet with the tuft - Little Thumbling. But in Samber's edition? Little Red Riding Hood - Diamonds and Toads - Bluebard - Sleeping Beauty - Puss in Boots - Cinderella - Riquet with the tuft - Little Thumbling. And... one more fairytale. "L'adroite princesse, ou les aventures de Finette" (translated as "The Discreet Princess"). This fairytale was actually not part of Perrault's texts - it was written by Perrault's niece, and one of the famous French fairytale authors, mademoiselle Lhéritier. But ever since this Dutch printing (and then its English translation, and then ever before since the first mistake was made in 1716), there is a common habit of identifying this fairytale as being Perrault's... a mistake which still appears sometimes today. But all of that to say, Samber's edition was complete randomness.

A few more reads disponible in English: "The Authentic Mother Goose Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes", 1960, by Barchilon and Petit + Jones' "Mother Goose's French Birth and British Afterlife" (this article is disponible on publicdomainreview.com)

Dutheil de la Rochère highlighted several key differences between Perrault's original French text, and Samber's translations, about the "Diamonds and Toads" fairytale. First, Samber's translation of the title as "The Fairy" - which isn't what Perrault wrote (he titled his stories "The Fairies", for subtle reasons since there is only one fairy in his story but who poses as two different women ; Samber probably meant to "correct" the title). Then there is the fact that Samber removed a certain "rustic", "peasant" tone and vocabulary within the dialogues, which Perrault precisely included to make the reader feel like in the French countryside and among common folks. There is also Samber's "moral" removing of a specific sentence - Perrault wrote that if the mother prefered one sister over the next, it was because she looked more like her and "people like more what is like them". It was part of Perrault's satire of human nature - Samber simply removed it all together. Finally, there is a distinctive "childish" selection of words to make the story seem more... "kiddy" let's say. Where Perrault wrote "a beautiful girl", Samber writes "a pretty little girl". Where Perrault wrote "my mother", Samber writes "mamma".

Random trivia: The nasty sister's name is translated as Fanny, a name derived from Frances and quite common in England at the time, soon to be associated with John Cleveland's scandalous "Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure". Perrault's name was merely "Fanchon", which is a rural diminutive of "Françoise" and was one of those stereotypical names for a young peasant girl.

Mind you, the "infantilization" of fairytales was not all due to England. It happened within France itself. Perrault, d'Aulnoy, Lhéritier and others were the first wave of fairytales, end of the 17th century. id 18th century there was a revival of the traditional French literary fairytale, a "second generation" so to speak - and a part of this generation grew the idea of writing fairytales for children. Chief in this school of thought was madame Leprince de Beaumont, the woman behind the most famous version of "Beauty and the Beast". She was a governess for the aristocracy, and part of what was then a progressive movement: teaching girls! Arg! The progress! As such, she personaly read fairytales as the perfect tool to teach children in a pleasant and educative way, and she was one of the first fairytale authors in France to have like straightforward manichean, moral and religious Morals at the end of her tales. Heck, her fairytale collection is called "Le magasin des enfants, "The children store", precisely because it was a children book.

But where am I going with this? Remember when I said Samber dedicated his work to the children of Lord Carteret? Well, Leprince de Beaumont also dedicated her work to children... To one child specifically. Sophia Carteret, youngest daughter of Lord Carteret (a character in the book was even based upon her). Indeed, while Madame Leprince de Beaumont was French and wrote in French, she had emigrated to London in 1748 and had worked there for British aristocracy. Given she created her own fairytales after Samber did his translation of Perrault's, and she herself described in her texts Perrault's story as "puerile but perfect for children" (*cough cough*), it is very likely she was influenced in her fairytale writing by Samber's complete reinterpretation and flasification of Perrault's tales. And since Leprince de Beaumont's work came to be spread and known throughout Western Europe... Began the misconception that fairytales had been written for kids.

Trivia: Madame Leprince de Beaumont wrote her own variant of "Toads and Diamonds" - but she wrote it as a fable. "The fable of the widow and her two daughters", in the line of other French fables for children such as those of Fénelon.

Last reading recs: Shefrin's "Governess to their Children: Royal and Aristocratic Mothers Educating Daughters in the reign of George III" (in "Childhood and Children's Books in Early Modern Europe" by Immel and Witmore) + Seifert's "Madame Leprince de Beaumont and the Infantilization of the Fairy Tale" (in "The Child in French and Francophone Literature".

#fairytales#fairy tales#french fairytales#english fairytales#charles perrault#perrault fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#diamonds and toads#robert samber#madame leprince de beaumont#fairytales history#mother goose#mother goose's fairy tales

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Mists of Avalon is a 1983 historical fantasy novel by American writer Marion Zimmer Bradley, in which the author relates the Arthurian legends from the perspective of the female characters. The book follows the trajectory of Morgaine (Morgan le Fay), a priestess fighting to save her Celtic religion in a country where Christianity threatens to destroy the pagan way of life. The epic is focused on the lives of Morgaine, Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere), Viviane, Morgause, Igraine and other women of the Arthurian legend."

"The Devil in the White City is a 2003 historical non-fiction book by Erik Larson presented in a novelistic style. Set in Chicago during the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, it tells the story of World’s Fair architect Daniel Burnham and of H. H. Holmes, a criminal figure widely considered the first serial killer in the United States."

"The Nightingale is a historical fiction novel by American author Kristin Hannah published by St. Martin's Press in 2015. The book tells the story of two sisters in France during World War II and their struggle to survive and resist the German occupation of France. The book was inspired by the story of a Belgian woman, Andrée de Jongh, who helped downed Allied pilots escape Nazi territory."

"Moby-Dick; or, The Whale is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the maniacal quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship Pequod, for vengeance against Moby Dick, the giant white sperm whale that bit off his leg on the ship's previous voyage."

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Musketeers (2023) - Part 1: d'Artagnan

Directed: Martin Bourboulon

Starring: Vincent Cassel, Eva Green, François Civil

First of all, you do not know the struggle we had to go through to even get our eyeballs on this movie! Only die hard Dumas idiots like me would have even bothered 🤦🏻♀️. Finally, we had to buy it from AppleTV. Anywho, below is my live blog of the latest French nonsense! I make a point of tutoring myself watching as many 3 Musketeers adaptations as possible, regardless of the psychological damage, and I kind of have high hopes for this one despite the fact that I can already tell they cast more for 20 Years After than for The 3 Musketeers. But I'm willing to pretend there are no good, young actors in France (because there's no other way to explain these casting choices) for the sake of my own sanity. The rest of my babbling and movie spoilers will be below the cut!

I see we start the movie in 1627, which already makes me laugh 🤣. The book famously starts in 1625 and then they time skip a year and a half into the future because I guess Dumas remembered that the war starts in 1627. Alex was the king of inexplicable time skips and I see the movie has chosen to stick to history rather than literary canon 👌🏻.

Everything is cold, dark, and wet. I have no idea what's going on, or who this blond woman is, or why d'Artagnan is coming back from the dead. But I'm always in favor of immortal abominations 😈.

It does entertain me that Eric Ruf, who played Aramis in an earlier French adaptation, plays Richelieu in this one. Nice touch.

LOL d'Artagnan gate crashing the musketeer headquarters all "I'm not Soviet, the French do not stand in line!" Anyways, he's authentically obnoxious, which I like, although clearly also 20 years too old.

I feel like this is an AU that takes place before they invented soap and also dyes, which is hilarious because if they're going for historical accuracy, this is just what the plebs think looks "authentic". Why are these men all so dirty and old? At least they make fun of Athos being a thousand years old in the movie, but why is Jussac also so ancient? And still serving in the guards? Life expectancy back then was like 25, but surely no one would be serving in the army past the age of 50, which was like Ancient for the 1600s, even among nobility.

I must laugh at the fact that Athos straight up introduces himself to d'Artagnan as Athos de Sillegue, le comte de La Fère. So, I see we are just going to go there 🤭🤭🤭. This changes his story arc completely though, stay tuned for my whinging. 🤦🏻♀️

Absolutely incredible, legendary , A++, 11000/10: bisexual Porthos waking up in bed with a lady and a dude after a night of debauchery! Chef's fucking kiss! I forgive the fact that there are no young people in France.

Aramis, so far is very Murder Kitten. I do wish he'd wash his face more and do something about his guyliner (I feel like he should have just committed to MORE MAKEUP frankly because the guyliner alone is odd), but c'est la vie, I guess.

Plus one point for Athos getting wrongly arrested, minus twenty points for making Athos a Protestant WTF? And in what world would a nobleman of Athos' lineage get sentenced to death for stabbing an unknown woman? This is all so silly! (I do have to give Milady points for just like fucking with him so fantastically. Plus one revenge point to Milady.)

Aramis torturing a guy to save Athos is honestly 👌🏻👌🏻👌🏻👌🏻 11/10 Murder Kitten, automatic plus one point.

This is all incredibly Dramatique, as much as it strains credulity. I love it when modern directors decide that they can write better "action" than Dumas himself. I'm just sitting here screaming "Why would you have that conversation where anyone can hear you!" Minus one point.

I must say Constance and d'Artagnan have a much more believable romance here than in the book. Plus 5 non-creeper points.

(Please I can't stop looking at how old all these Musketeers are 😅😅😅)

Okay so they've also given Athos a BROTHER. Who is part of a Protestant conspiracy. This is all so fucking crazy, I don't even know what to say. Am I watching the musketeers or La Reine Margot? 🤔

Incidentally, the King also gets a brother! Everyone gets a brother! J/K at least the King really did have a historical brother. Athos just gets fucked with in this movie a lot. Automatic minus one point for unnecessary siblings.

WHY must you all insist on having these super SECRET conversations in the middle of a public square where literally anyone can hear you? Minus one dumbass point.

And now d'Artagnan must go to England.... Alone? Because it's more heroic this way? Ambushed by ghost squirrels in the woods? Oh no, that's just Athos, lurking in the woods, as one does. "All misery comes from love." Thanks, Old Man Lush.

This revisionist tale of Milady's past is all very convenient but I FUCKING HATE IT every single time they try to do this in modern adaptations. Let Milady Be Evil 2023! But I see that you will not. Listen, it's not "feminist" to turn the villain into the victim. I'm so tired. 🤦🏻♀️ These misguided attempts at feminism really do not do her any favors, she has a lot more agency as simply the Really Bad Girl who just wanted money and power. Minus 5 points for not letting Milady have any fun and minus another 10 points for giving her an abusive ex-husband!

As for Athos, IMO it's always much more compelling to let him be the guy who tried to kill his beloved wife for betraying him, than to make him the spineless man who turns her over to the authorities for Handwavium. Yes, it's pretty fucked up. But it's much more humanizing and makes him a darker, more interesting character. And I will always maintain that.

(This movie is so fucking dark, all the scenes take place at night or in some cthonic tunnels or prisons ffs have mercy on my eyes!)

Oh dear, here we go again. Milady taking a Dramatique - and completely unnecessary - dive off a cliff. Only this time, we know she doesn't die because.... She can swim? And definitely will not have all her bones broken by that 1000 ft fall. Minus 20 points for lazy writing.

(My God, everyone is so dirty, you would think they never did their laundry in France 🤦🏻♀️)

Ironically, the only well lit scene takes place in what looks like the Notre Dame which is just very silly as that place is a sepulcher.

(Once again, we are advancing the plot by having super secret conversations conducted in the middle of the palace with an open door where anyone can see and hear you plotting 🤦🏻♀️ Minus one petty point.)

Okay, so poor Constance has been kidnapped, and our young hero (who is already a Lieutenant because he and his pals conveniently saved the King's life in a plot twist that was very necessary in other to return Athos to favor in this version) lies unconscious in the streets. They probably didn't even try to kill him this time because they know he's immortal. And speaking of people who just won't die, in a mid-credits scene, it is confirmed that Milady is indeed, very much Not Dead Yet. Surprise! The scene is now set for war in The Three Musketeers: Part 2: Milady.

In summary:

I tallied up my totally random points and ended up with a score of -51, which is Not Good, my friends.

Okay, so I've seen much worse? It's better than Atrocity in 3D, for example, which was just barely watchable as a film and as an adaptation. But they changed so much about the plot and some of the main characters, that it doesn't really feel true to the spirit of the book at this point, which is my main criteria for measuring whether an adaptation is successful. And the main reasons for that are because it's much darker and grittier and less fun than the novel. Which - Quelle domage!

I know that as an unrepentant Athos fangirl, I tend to be biased, so I was trying to be on guard (heheh get it?) for my own biases while watching this. But it's really difficult when Ya Boy is such an integral part of the novel as well as this particular adaptation. And so I must regrettably come back to what a shame it is that they've cast a 60 year old Athos (Vincent Cassel is 57 and he's a fabulous actor whom I've loved in many of his worlks), and I feel like they had to rewrite his character to be more age appropriate and less of the drunken asshole he is in Dumas' first d'Artagnan book. But that's the asshole I fell in love with, and will stan forever. Without him going around beating his servant, indulging his gambling addiction, and being a sarcastic pain in everyone's ass, it's just a completely different story.

Pros:

Hot Eva Green!

bisexual Porthos!

d'Artagnan is given a much less creepy love story with Constance (and I assume he will also not be nonconning Milady in this adaptation)

The King and Queen are much more humanized and sympathetic here.

Cons:

Visually really drab, everything is brown, everyone is dirty.

Very little humor unlike in the novel and some other adaptations.

EVERYONE IS WAY TOO OLD, which changes the feeling of the story significantly, and IMO for the worse, because these people are just not allowed to have fun, and subsequently, neither is the audience.

I will still absolutely be here for Part 2 because I am a masochist!

Grade: B- as a piece of art, but a C as an adaptation of the Dumas classic.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Feuilles Mortes lyrics and English translation

“Les Feuilles Mortes” (“The Dead Leaves”) was composed in 1945 by Joseph Kosma with lyrics by poet Jacques Prévert for the 1946 French film Les Portes de la Nuit. Yves Montand was the first to perform the tune in the film, which was set in World War II Paris and was part of the “poetic realism” movement.

In 1945, Prévert wrote the film script "Les Portes de la Nuit" (a film of Marcel Carné - 1946), from a ballet "Le Rendez-Vous" created by Roland Petit in 1945. The two first verses of a song give the title : "Les enfants qui s'aiment s'embrassent debout/contre les Portes de la Nuit". Jean Gabin and Marlene Dietrich had acepted to play the two characters, but at last, they changed for another movie : "Martin Roumagnac".

A young french singer presented by Edith Piaf : Yves Montand plays this very pessimist film and sung "Les Feuilles Mortes". The music was created, before, by Joseph Kosma for the ballet "Le Rendez-Vous" in 1945, and Prévert wrote, after, the words for the movie.

The poem was published, after the death of Jacques Prévert, in the book "Soleil de Nuit" in 1980

“Les Feuilles Mortes”

Oh, je voudais tant que tu te souviennes

Des jours heureux où nous étions amis

En ce temps-là la vie était plus belle

Et le soleil plus brûlant qu'aujourd'hui.

Les feuilles mortes se ramassent à la pelle

Tu vois, je n'ai pas oublié

Les feuilles mortes se ramassent à la pelle

Les souvenirs et les regrets aussi.

Et le vent du Nord les emporte,

Dans la nuit froide de l'oubli.

Tu vois je n'ai pas oublié,

La chanson que tu me chantais...

Les feuilles mortes se ramassent à la pelle

Les souvenirs et les regrets aussi,

Mais mon amour silencieux et fidèle

Sourit toujours et remercie la vie.

Je t'aimais tant, tu étais si jolie,

Comment veux-tu que je t'oublie?

En ce temps-là la vie était plus belle

Et le soleil plus brûlant qu'aujourd'hui.

Tu étais ma plus douce amie

Mais je n'ai que faire des regrets.

Et la chanson que tu chantais,

Toujours, toujours je l'entendrai.

C'est une chanson qui nous ressemble,

Toi tu m'aimais, moi je t'aimais

Et nous vivions, tous deux ensemble,

Toi qui m'aimais, moi qui t'aimais.

Mais la vie sépare ceux qui s'aiment,

Tout doucement, sans faire de bruit

Et la mer efface sur le sable

Les pas des amants désunis.

C'est une chanson qui nous ressemble,

Toi tu m'aimais et je t'aimais

Et nous vivions tous deux ensemble,

Toi qui m'aimais, moi qui t'aimais.

Mais la vie sépare ceux qui s'aiment,

Tout doucement, sans faire de bruit

Et la mer efface sur le sable

Les pas des amants désunis

———-

Oh! I would like as much as you remember

The happy days where we were friends.

In this time the life was more beautiful,

And the sun more burning than today.

The dead leaves collected with the shovel.

You see, I did not forget...

The dead leaves collected with the shovel,

The memories and the regrets also

And the wind of North carries them

In the cold night of the lapse of memory.

You see, I did not forget

The song that you sang me.

[ Refrain: ]

This is a song which resembles to us.

You, you loved me and I loved you

And we lived both together,

You who loved me, me who loved you.

But the life separate those which love themselves,

All softly, without making noise

And the sea erases on the sand

The Steps of divided lovers.

The dead leaves collected with the shovel,

The memories and the regrets also

But my quiet and faithful love

Smiles always and thanks the life

I loved you so much, you was so pretty.

Why do you want that I forget you ?

In this time, the life was more beautiful

And the sun more burning than today.

You were my softer friend

But I don't have only to make regrets

And the song than you sang,

Always, always I will hear it !

The penultimate day of the 2024 Olympics in Paris brings not only medals but memories from the Legends of France French music 🇫🇷

youtube

#chanteur #scene #chanson #musique #yvesmontand #varietefrancaise #variete #chansonfrancaise #chansonamour

Posted 10th August 2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My meager contribution

My meager contribution this year will be

A. My expository essay on the June Rebellion

B. My new Eponine drawing when I find it (I lost it lmao)

Essay under the cut (ignore any typos, I was exhausted when I finished this a few months ago

The June Rebellion of 1832.

Many people believe that Victor Hugo’s famous book and stage musical, “Les Misérables” took place during the famous and successful French Revolution. When in reality, it took place during the June Rebellion of 1832. The June Rebellion of 1832 originated in an attempt to combat the corrupt establishment of the July Monarchy of King Louis Philippe and alleviate the poor living conditions of the people of Paris. Although it may have failed, the June Rebellion of 1832 may have set the stage for more successful revolutions.

The June Rebellion of 1832 was an attempt to reverse the establishment of the monarchy of Louis Philippe. The June Rebellion was caused when Louis Phillipe rose to power, and living conditions worsened for the poorer people of France. According to The Collector, Louis Philippe ascended to the throne after the July Revolution in 1830 after Charles X fled France for London, England. Louise Philippe proceeded to raise the cost of living, even though most of the population was already living in poverty. The living conditions only got worse when an outbreak of cholera occurred claiming the lives of nearly 19,000 people (The Collector). One of the most important lives lost was that of General Jean Maximilien Lamarque on June 1st, 1832. These factors and statistics helped to set the stage for the upcoming rebellion of the people of France.

On June 5th, 1832, General Lamarque’s funeral was held, many Parisians were present since funerals were held in a huge political regard then. Over 100,000 Parisians began a mass protest; they felt that Louis Philippe had favored the rich and worsened the living conditions of those in poverty. Many of those involved in the protest were refugees from Poland, Portugal, Germany, and Italy. Lamarque had been opposed to France’s foreign policies at the time. The protest only went sideways when a red flag labeled “Liberty or Death” was raised and shots were fired at Government soldiers. The rioters took control of the parade and directed the procession through Place De La Bastille, where the French Revolution occurred. Around Rue Saint Martin and Rue Saint-Denis, barricades were erected. The Cloitre Saint-Merri was the scene of the decisive battle, it lasted into the early hours of June 6th and claimed a total of 800 lives. 93 insurgents were killed, and 291 were wounded, 73 soldiers were killed 344 were wounded. (The Collector) While this rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, it continued the tradition of uprisings in France that would go on to change the entire structure of the country.

At this point, King Louis Philippe decided to appear publicly and demonstrate he was still in power, the rioters were put on trial and punished. Ultimately the June Rebellion did not achieve its aims and failed to threaten the monarchy. However, it did serve as a catalyst and prerequisite for the French Society to resist and eventually overthrow King Louis Phillipe in 1848. Victor Hugo was inspired by the story of the June Rebellion, and his novel, Les Misérables, has been a source of artistic expression for nearly two centuries. Louis Philippe’s rise to power and the several tragedies that followed it are the main events causing this rebellion. With the far-reaching impacts of this fateful day, can we call it an unsuccessful revolution?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text