#is this a sociolinguistic variable

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’ve observed something interesting. I’m not sure why that’s the case, but each of these terms seem to have a slightly different connotation.

If you’re a Genshin Impact fan, which of the following would you rather be referred to as?

Does your enjoyment of the game/story influence your choice? Or whether you play the game or not? How about the way you perceive the English fandom? Is it the same if anyone calls you that, or is it restricted to those in the fandom, or maybe close friends?

#is this a sociolinguistic variable#it’s just I’ve seen this phenomenon when it comes to En.stars too. as an outsider#poll#Genshin impact#Genshin#dusk rambles#linguistics#sociolinguistics#genshin fandom#genshin polls

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Käärijä Research Project

aka: käärijä style-shifting project

as a preface, here are my (non) qualifications for this project and the circumstances under which it happened:

I am a linguistics student, and this past semester I took a course on sociolinguistics. the goal of this project was to become familiar with the concept of and analyze style-shifting (it's more commonly known as code-switching online but theres a difference and this is style-shifting), specifically by analyzing the speech of one person. We had the option to study oprah or to have someone else approved by my prof, so you know I had to ask my prof if I could study jere. This project is solely my intellectual property; even though I had a tutor help me a lot, everything written in this paper and on this post was my work alone.

now, on to the actual findings! the full paper and transcripts will be linked at the end :D

the actual variables (words or sounds) that I studied were the pronunciation of r, and use of the word "the".

to make things a lot easier from the get-go, i'm going to introduce you all to one of my favorite websites, ipachart.com (the international phonetic alphabet [ipa] chart is a big chart with an entry for every sound that exists in a language. this handy dandy website has an audio recording for each one of those sounds).

go to this website, and then scroll down to the table. go to the column labeled "post alveolar" and then click on ɾ and ɹ. those are the sounds i studied in this paper! ɾ is the finnish r and ɹ is the american r :)

so basically what i did to find instances of my variable was i just looked up a bunch of esc interviews and listened out for use of the different r sounds. i also transcribed the entire dinner date live because i love torture apparently :) the specific interviews and lives/stories are in the bibliography of the paper :p

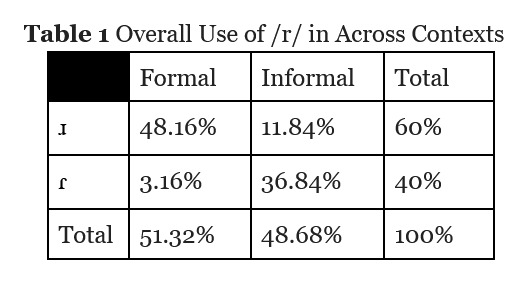

after i transcribed all the interviews and lives/stories i went through and highlighted every instance of the r sound. then i calculated the ratios of ɾ to ɹ based on the context they were spoken in. the two contexts i looked for were formal contexts (sit-down interviews) and informal contexts (literally anything else).

i found that jere uses ɹ WAY more often in formal contexts than he does in informal contexts, and the same in reverse with ɾ.

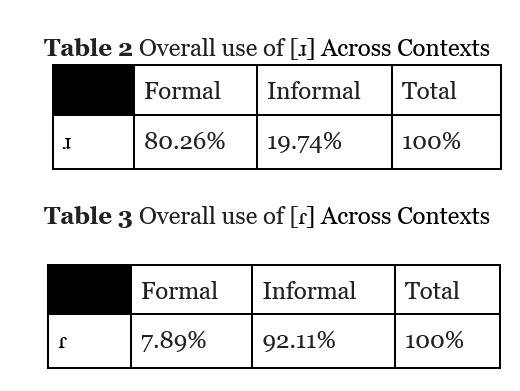

i then went back to the transcripts and looked for all instances of the word "the". i also looked for instances where i thought it should be present, but was omitted. i calculated the ratio of present vs omitted "the"s in formal vs informal contexts and made some charts.

the graph with the smaller black section is "use of 'the' in formal settings" and the one with the smaller green section is "use of 'the' in informal settings" (the images are transparent, sorry)

i found that jere uses "the" WAY more often when in formal settings! there were also some instances where he added a "the" where it was unnecessary, which is studied at length in this wonderful paper by @alien-girl-21

something i also noticed that i elected not to study because this paper took enough energy on its own was that in formal contexts, whenever the "or" sound came in the middle or at the end of a word, jere wouldn't pronounce the r. it stuck out to me mostly because i heard words like "performance" turning into "perfomance", which i thought was an interesting quirk.

unfortunately i was somewhat limited by both my brainpower and capacity to do more work on this paper in the relatively short timeframe i was given (2 weeks) and the fact that i was given a 5 page MAX for this paper (not including a bibliography). i had a lot of fun doing this though and am definitely planning on studying jere for for academic credit again in the future if given the chance!

also i would like it to be known that i spent an hour searching for that 5 second clip of the urheilucast where jere said that he used to sell kitchens and understands english better than he can speak it.

link to a google drive folder with the actual paper i wrote and the transcripts of the interviews with notation:

please feel free to send me asks and dms with questions or comments about this paper! i absolutely love rambling about linguistics :3!!

#i think this is everything!#it always feels so much shorter than i think its going to be#both because of how much effort i put in#and also because i was constantly comparing myself to cyns paper 😅#my irls kept reminding me that i didnt have to and in fact wasnt allowed to write 43 pages analyzing jeres speech#but i kinda wanted to#i also wrote this paper on april 2nd#i remember that because the previous day i spent all day booping#and then i literally worked all day from 9.30 until 23.30 on stuff for my linguistics class#because i had this paper due on friday or saturday and i had a research summary due on that thursday (the 4th)#it was so much work that made some things worse but god was it worth it#linguistics my beloved <3#käärijä#into the tag you go#i reserve the right to edit this post if i realize there are any problems#linguistics

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The trap–bath split is a vowel split that occurs mainly in Southern England English (including Received Pronunciation), Australian English, New Zealand English, Indian English, South African English and to a lesser extent in some Welsh English as well as older Northeastern New England English by which the Early Modern English phoneme /æ/ was lengthened in certain environments and ultimately merged with the long /ɑː/ of palm. In that context, the lengthened vowel in words such as bath, laugh, grass and chance in accents affected by the split is referred to as a broad A (also called in Britain long A). Phonetically, the vowel is [ɑː] ⓘ in Received Pronunciation (RP), Cockney and Estuary English; in some other accents, including Australian and New Zealand accents, it is a more fronted vowel ([ɐː] ⓘ or [aː] ⓘ) and tends to be a rounded and shortened [ɒ~ɔ] in Broad South African English. A trap–bath split also occurs in the accents of the Middle Atlantic United States (New York City, Baltimore, and Philadelphia accents), but it results in very different vowel qualities to the aforementioned British-type split. To avoid confusion, the Middle Atlantic American split is usually referred to in American linguistics as a 'short-a split'.

In accents unaffected by the split, words like bath and laugh usually have the same vowel as words like cat, trap and man: the short A or flat A. Similar changes took place in words with ⟨o⟩ in the lot–cloth split.

The sound change originally occurred in Southern England and ultimately changed the sound of /æ/ ⓘ to /ɑː/ ⓘ in some words in which the former sound appeared before /f, s, θ, ns, nt, ntʃ, mpəl/. That led to RP /pɑːθ/ for path, /ˈsɑːmpəl/ for sample etc. The sound change did not occur before other consonants and so accents affected by the split preserve /æ/ in words like cat. (See the section below for more details on the words affected.) The lengthening of the bath vowel began in the 17th century but was "stigmatised as a Cockneyism until well into the 19th century". However, since the late 19th century, it has been embraced as a feature of upper-class Received Pronunciation.

Like all accents, RP has changed with time. For example, sound recordings and films from the first half of the 20th century demonstrate that it was usual for speakers of RP to pronounce the /æ/ sound, as in land, with a vowel close to [ɛ], so that land would sound similar to a present-day pronunciation of lend. RP is sometimes known as the Queen's English, but recordings show that even Queen Elizabeth II shifted her pronunciation over the course of her reign, ceasing to use an [ɛ]-like vowel in words like land. The change in RP may be observed in the home of "BBC English". The BBC accent of the 1950s is distinctly different from today's: a news report from the 1950s is recognisable as such, and a mock-1950s BBC voice is used for comic effect in programmes wishing to satirise 1950s social attitudes such as the Harry Enfield Show and its "Mr. Cholmondley-Warner" sketches

Gupta's study of students at the University of Leeds found that (on splitting the country in two halves) 93% of northerners used [a] in the word bath and 96% of southerners used [ɑː] However, there are areas of the Midlands where the two variants co-exist and, once these are excluded, there were very few individuals in the north who had a trap–bath split (or in the south who did not have the split). Gupta writes, 'There is no justification for the claims by Wells and Mugglestone that this is a sociolinguistic variable in the north, though it is a sociolinguistic variable on the areas on the border [the isogloss between north and south]'.

In some West Country accents of English English in which the vowel in trap is realised as [a] rather than [æ], the vowel in the bath words was lengthened to [aː] and did not merge with the /ɑː/ of father. In those accents, trap, bath, and father all have distinct vowels /a/, /aː/, and /ɑː/.

In Cornwall, Bristol and its nearby towns, and many forms of Scottish English, there is no distinction corresponding to the RP distinction between /æ/ and /ɑː/.

In Multicultural London English, /θ/ sometimes merges with /t/ but the preceding vowel remains unchanged. That leads to the homophony between bath and path on the one hand and Bart and part on the other. Both pairs are thus pronounced [ˈbɑːt] and [ˈpɑːt], respectively, which is not common in other non-rhotic accents of English that differentiate /ɑː/ from /æ/. That is not categorical, and th-fronting may occur instead and so bath and path can be [ˈbɑːf] and [ˈpɑːf] instead, as in Cockney.

Silvio Pasqualini Bolzano inglese ripetizioni English

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey friendo, also linguistics and fictional universes nerd!

I heard that you're game to share your wisdom with us mere mortals (aka authors) so here goes.

I'm writing a cyberpunk novel. Everyone speaks english cause writing a new language is FAR beyond my skill set, but I want to play with grammar as a way to show the reader class differences. (This is what happens when you let a socialist write a novel.)

In this futuristic dystopia, only the very rich can afford unlimited data (aka Canada in 2023). My thought is the working class have adopted speech patterns to minimize unnecessary words--dropped their article (goodbye 'the'), drop context markers unless necessary (goodbye 'that'), that kinda thing. The rich, being rich, speak in sentences the reader will recognize as grammatically 'correct.'

Two questions for Your Lingistic Eminance:

What do the middle class do? How do they sound?

2. Are there any great grammatical patterns I could include that I haven't thought of yet?

Thanks so much! I am VERY EXCITED to hear.

This is a great question! The short answer to part 1 is that they’ll mimic the upper class/upper middle class aspirationally, as least in situations where the UC/UMC will notice them, in what we call hypercorrection. A couple ideas for part 2 are dropping the subject of the verb if it’s obvious (which we already do in English - “love you” as a sign-off in a text message, or diary-style “went to the store. Didn’t find avocados.”) or deciding that even the limited verbal inflection that remains in English is unnecessary, so no more 3rd-person-singular s. (This is already present in several varieties of English, including African American English.)

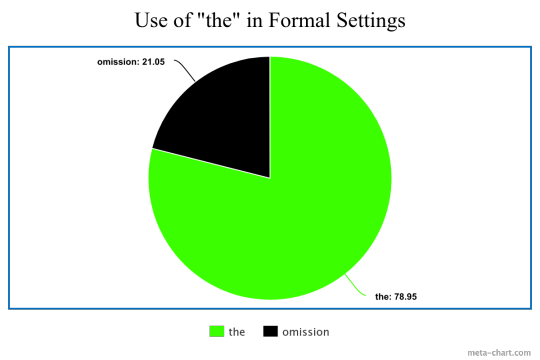

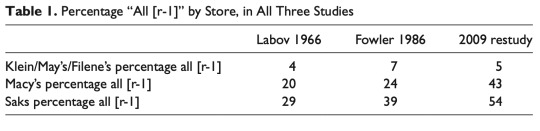

The long answer for part 1 is really cool and relies on one of the foundational studies of sociolinguistics, published by Bill Labov in 1966. A 2012 paper by Mather replicates Labov’s study and points out some methodological problems caused by increased movement within the US and from outside the US (more on that in a minute), but it finds essentially the same stratification of this particular phoneme by social class.

For his original study, Labov wanted to see if socioeconomic class affected the way people spoke. He lived in New York City, and one of the distinctive features of a New Yorker accent is the absence of /r/ sounds (New Yawk). (As I wrote a little bit ago, rhotics aren’t real, but their presence or absence (or the ghosts of their presence) is a key feature of accents.) But Mainstream American English does have /r/ sounds, and this variety has what we call prestige.

Prestige varieties are typically spoken by the group with the most social (political, economic, etc) power – and, crucially, there is nothing inherent to the variety that makes it “better” than another variety. It’s just the one that the powerful use, and thus the one “correctness” is measured against.

So. New York English typically does not contain /r/ sounds, but the prestigious (standard) variety of US English does, and various social factors lead to the upper & upper middle classes preferring the more standard variety, while the lower and lower middle classes will prefer the non-standard variety. (Some of this has to do with group identity and using the non-standard variety to showcase group membership, but that’s an entirely different question.)

When Labov designed his study, he wanted to look at /r/ immediately after a vowel, because that’s where you notice its presence or absence most readily, so he used the phrase “fourth floor.” In fourth, you have a vowel followed by an /r/ which is followed by an obstruent /th/, which is phonotactically a different beast from floor, where the post-vocalic /r/ is the end of the word. And in the most typical New York English of 1962 (when he gathered his data), both of these /r/s were absent. But he wanted to study the effects of social stratification on the presence of /r/, so he devised a study based on proxy variables (aka markers).

The marker he used for socioeconomic class was department stores, assuming that employees would come from a similar class to the store they worked in (i.e. someone from the upper middle class isn’t going to work at TJ Maxx). He picked a low-cost one (S. Klein, now defunct) to represent the lower class, Macy’s to represent the middle class, and Saks Fifth Avenue to represent the upper middle class. (All stores are on the Lower East Side.)

To gather his data, he approached an employee of the store and asked where he could find a department that he knew was on the fourth floor. When they answered, he pretended he didn’t understand, and the employee repeated themself. This gave him proxy data for casual (first ask) and careful (repeated) speech.

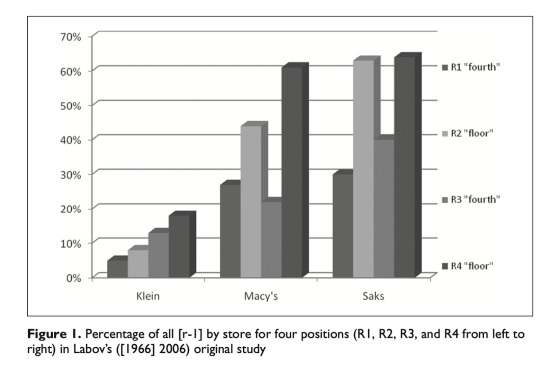

What did he find? As expected, the employees of the lower-class store used /r/ far less often than in the other stores – in fact, barely 10% of the time. The charts in Labov 1972* are confusing, so I’ll use ones from Mather 2012, because I think they’re clearer.

The working-class proxy store had, and still has, very few employees who pronounce the /r/ in fouRth flooR 100% of the time, while the middle- and upper-middle-class proxy stores have higher and increasing rates of 100% /r/ pronunciation. (This indicates that /r/ pronunciation is probably a prestige variation, and increasing use indicates that the middle class and higher is adopting this variation.)

This graph confused me for about 5 minutes, because all [r-1] isn’t the same as “all [r-1],” so what it shows is the percentage of /r/-pronunciation in total. If someone said, for example, “fou’th flooR,” they would get an [r-1] for the category R2 and an [r-0] for R1. (The study may be foundational, but his coding of variables leaves something to be desired.) So, you can see that Klein, representing the working class, has between 5% and 18% of people pronouncing an /r/ at least once, while Macy’s and Saks are all 20% or higher. (The drop in /r/-pronunciation in R3 at Macy’s is interesting, but it’s not explained in the papers I read.)

*I have a scan of one chapter of something labelled “Labov 1972,” but not the 1966 book or the 2006 2nd edition.

I can’t find the paper I’m looking for that shows the crossover effect, where upper middle class speakers use /r/ less than middle class speakers (it may have been on paper, not a pdf, so it’s lost to the recycling bin of time), but fortunately it’s summarized in Allan Bell’s textbook (The Guidebook to Sociolinguistics, 2014). This didn’t come from the “fourth floor” study, but one where he had people read word lists or phrases, as well as elicit them in regular speech. Most interesting is the line “class 6-8” (lower middle class), where it spikes between C (reading) and D (word lists) and crosses over the line “class 9” (upper middle class). I don’t think I can improve on Bell’s wording, so I’ll quote him. The lower middle class hypercorrects: “in pursuit of prestige, the class that is just below the most prestigious actually overshoots their model. This became known as the lower-middle-class crossover effect” (168).

So, 1000 words later, we have evidence for the existence of social stratification of a particular variable, and the theoretical methodology has been applied again and again in different situations and with different variables in the last nearly 60 years, and it seems pretty robust (with caveats and methodological improvements and so on, of course). You can, in fact, stratify linguistic variables by categories that include race, gender, and class. The aspirational class (the one just below the most prestigious class) wants to sound like the prestige class, so they imitate what they think the prestige class sounds like, and in so doing frequently overshoot and use the variable in question more than the prestige class, while the lower classes are far less likely to use the prestige variety. (And I haven’t even mentioned covert prestige yet, which is when a non-prestige variant is preferred in certain groups, because it symbolizes membership in the non-prestige group.)

If you think this is interesting, consider backing my Kickstarter, where I’ll be writing a book about how to use linguistics in your worldbuilding process. Or if tumblr ever sorts out tipping for my account, leave me a tip.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jobs: English; Anthropological Linguistics, Computational Linguistics, Phonetics, Sociolinguistics, Text/Corpus Linguistics: Research Associate Position, University of Chicago

Description: The Department of Linguistics at the University of Chicago invites applications for a Research Associate position. The Research Associate will join a dynamic research group focusing on projects investigating the construction of social meanings across various contexts (including, but not limited to legal contexts) and linguistic variables using a range of experimental, sociophonetic, and/or computational techniques. The Research Associate’s primary responsibilities include setting http://dlvr.it/TK0qdF

0 notes

Text

La pronunciación esdrújula de diabetes

I recently worked with a young man from Honduras who pronounced the Spanish word for 'diabetes' with the stress on the antipenultimate syllable--that is, as an esdrújula word, diábetes, instead of the common, llana, pronunciation, diabetes. That was not the only example I've come across, as I had heard it in two different ocasions in the past, from speakers from Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

That is obviously a very rare pronunciation, as evidenced by the fact that I've only encountered a handful of examples among the thousands of interactions I've had as Spanish interpreter during the past decade or so. Since the speakers belonged to different nationalities and age groups, it's hard to pinpoint a dialectal or sociolinguistic motivation. The esdrújula form is mentioned by the Diccionario de la Real Academia: "Es voz llana: [diabétes], aunque en algunos países de América se oiga a menudo como esdrújula: ⊗[diábetes]."

Although there are several well documented cases of words with variable pronunciations, both of them accepted as correct--like cardíaco vs. cardiaco, or vídeo vs. video--, diábetes seems to be discouraged by the Academia. Its rare use may be due to individual idiosyncrasies and hypercorrection, but I would love to learn of additional examples.

0 notes

Text

21.10.20

jwoejej I forgot to come back to a question for my linguistics midsem exam.

#the question was like 'how would you determine the factor that caused the sociolinguistic variable be specific'#my short answer was 'ask their background' thinking that I'll expand later#but i didn't ksjsjjs

0 notes

Text

research mentor: And What Might Your Dependent Variable Be For Your Research Project :-)

me: [NOT going to say "well it could have been phonetic/phonological or sociolinguistic differences between different groups of darija speakers but YOUUUU don't like phonology or sociolinguistics for mysterious reasons so i guess not those]

#i am not going to do lexical semantics. im not#wugs and co#so anyway. i am planning for my research project.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Media Influence on Implicit and Explicit Language Attitudes

Sociolinguists often assume that media influences language attitudes, but that assumption has not been tested using a methodology that can attribute cause. This dissertation examines implicit and explicit attitudes about American Southern English (ASE) and the influence television has upon them. Adapting methodologies and constructs from sociolinguistics, social psychology, and communications studies, I test listener attitudes before and after exposure to stereotypically unintelligent and counterstereotypically intelligent representations of Southern-accented speakers in scripted fictional television. The first attitudes experiment tests implicit attitudes through an Implicit Association Test (IAT). This experiment also serves to test sociolinguistic use of the IAT with a more holistic accent as opposed to single linguistic features. The second attitudes experiment tests the effect of television exposure on explicit attitudes towards an ASE-accented research assistant (RA). The experiments also investigate the influence of listener knowledge of regional origin of actors (speaker information), listener perception of how closely television represents the world around them (perceived realism), listener exposure to the South, and listener identity. The hypothesis is that those who hear counterstereotypically intelligent Southern characters will rate a Southern-accented research assistant higher in intelligence than those who hear stereotypically unintelligent Southern characters. The same pattern will hold in the auditory-based IAT. Accents in both the implicit and explicit attitudes experiments are viewed holistically, including multiple features rather than focusing on the most salient features. To clarify results related to the speaker information and perceived realism variables, a separate experiment tests how successful listeners are at differentiating natives from performers of regionally accented American English.

Results indicate that televised representations of Southern accents affect explicit, but not implicit attitudes. Participants who heard intelligent Southern characters rated an ASE-accented RA higher in competence than those who heard unintelligent Southern characters. Several demographic variables influenced results regardless of the stereotypicality of the speakers that the listener heard in the television clips, including self-identified race and exposure to Southern television. While implicit attitudes were not affected by television in this case, the IAT was successfully adapted for use with a holistic accent rather than a single feature and also captures associations between an L1 regional accent and a specific stereotype of that accent. I discuss these results in regard to language attitudes at large as well as their implications for an indirect language change model, the Associative-Propositional Evaluation (APE) model of attitudes, and cultivation theory. The dissertation argues that scripted television does influence language attitudes, but in more complex ways than a simple cause-and-effect relationship. While television can affect explicit attitudes towards individual speakers, implicit attitude shift is more difficult and may need more time and/or need a direct cause for a shift to occur. Regardless of media influence, language attitudes are affected by identity and demographic features listeners bring into the interaction with speakers.

Heaton, H. E. (2018). Media influence on implicit and explicit language attitudes (Order No. 11006885). Available from Linguistics Database. (2166299268). Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/media-influence-on-implicit-explicit-language/docview/2166299268/se-2?accountid=9900

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

it's not so much folk wisdom vs. academic 'knowledge'... the point is for the vanguard party to introduce sophisticated academic concepts to the working class by way of policy, agitation and organization. notions like surplus value are so deeply rooted in economic and political theory that 'folk' explanations of them obviously wouldn't be sufficient

the post recognizes only that there will always be a contextual divide between academics and non-academics (if the structure of academia necessarily distances itself from non-academia of course). its within the nature of academia to produce concepts using a great deal of background knowledge, or intellectual concepts. commonly-educated citizens will not hold this background knowledge naturally, unless for some reason they spend their free time being academic -- at which point id say they’ve transgressed the boundary into academia. what counts as “being academic” is also not the scope of this post lol, i dont mean to socratic dialogue this; just assume there is a difference between being so and not being so. anyway, the capacity for understanding these terms is limited by one’s background knowledge. common folk will not have that capacity and will (generally) not completely comprehend the scope of a given concept, as they essentially are not able to completely understand it without the given background knowledge. even if the concept is successfully transmitted there exist sociolinguistic processes that can also transform the meaning and application of the term over time, turning it into slang and eventually a codified term altogether different in usage from its past. the process of reducing the complexity of and popularizing concepts specifically precedes the formation of “folk understandings of terms”. so long as there exists an academic sphere separate from folk pools of knowledge, there will always be a trickling down of technically-reduced terminology, and thus a disconnect in how the two spheres operate the terms in communication. this is a generic overarching process, though, and like basically every system the more individual you go the more chaotic and broken down the system is. the “atom” of this system is a person; therefore, interest, education, critical thinking skills, and tons of other personal variables will decide what informational bits stick and how creatively or restrictively you use the bits.

despite all this my actual opinion is that both academic and folk spheres aren’t doing anything incorrect. i believe that to understand a word’s definition you must understand all the different contexts and meanings which might apply to that word. that post just means to highlight that the process of transmission from academic to folk spheres is essentially a game of telephone with specific reductive properties but i just worded it really badly.

whether vanguard parties may or may not successfully preserve the full integrity of scientific terms when translating them to the working class is not really the point of the post, as you can see, because it depends on how they would do it. the success of that depends on how successful it is lol

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suggerimenti di lettura - 1

Swearing in English uses the spoken section of the British National Corpus to establish how swearing is used, and to explore the associations between bad language and gender, social class and age. The book goes on to consider why bad language is a major locus of variation in English and investigates the historical origins of modern attitudes to bad language. The effects that centuries of censorious attitudes to swearing have had on bad language are examined, as are the social processes that have brought about the associations between swearing and a number of sociolinguistic variables. Drawing on a variety of methodologies, including historical research and corpus linguistics, and a range of data such as corpora, dramatic texts, early modern newsbooks and television programmes, Tony McEnery takes a sociohistorical approach to discourses about bad language in English. [...] Tony McEnery is Professor of English Language and Linguistics at Lancaster University, UK, and has published widely in the area of corpus linguistics.

T. McEnery, Swearing in English (Imprecare in inglese) [2006], London-New York, Routledge

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A social dance between culture and spoken language

In a social construct, language is used to categorize people based on their dialects, accents, and mannerism. Social identities and social groups are many and varied among people. For example, there may be 'teachers', ‘engineers', 'Parisians', and so on. Being able to speak the language, a variety, or use of a particular jargon gives a sense of belonging to the group. That is why it is often said, an individual's sense of belonging to a national group is often closely linked to their spoken language. The remainder of this piece will look at a few of the external factors that influence the adoption of certain spoken languages by a group of people along with how they shape personal identity.

Language and identity in Sociolinguistics Sociolinguistics is the study of how social parameters such as age and gender, influence language use. In practice, this considers how someone communicates and is able to come to their own judgment based on external variables. Geographic location, gender, employment, class, and ethnicity constitute a few of the social elements that might influence a person's language and identity. As a general rule, individuals from higher social classes are more likely to speak with Received Pronunciation (RP); this is because RP has historically been the accent used and taught in educational institutions.

As previously mentioned, the use of certain linguistic elements can convey a sense of belonging to various social groupings. These group-specific characteristics are utilized to convey to society as a whole a distinctive identity that has been recognized as belonging to a certain group's sociolect. Today, an example would be a teenager using the term "GOAT," which is just slang for "greatest of all time." Other phrases that are frequently encountered include 'lit' (to imply amazing/brilliant) and 'V' (very). The use of such jargon and particular slang phases allows individuals in distinguishing themselves from earlier generations, such as their parents or grandparents, and portray their age as a focal point of their identity.

Linguist Michael Nelson, conducted a study in the year 2000 on the use of jargon in the corporate field. He arrived at the conclusion that people at work employ language in a semantic field of business, such as business, firms, money, technology, and so on. Nelson's theory illustrates the idea of identity and how a person may acquire a workplace language, therefore he pointed out how certain phrases or topics were deliberately not used in business communication. Lexis such as weekend activities, difficulties at home, or family. This demonstrates how an external factor, such as a profession, can influence spoken language. When at work, speakers may use Nelson's business lexis to create a professional identity while keeping their home identity private, or they may deviate from Nelson's business lexis and use more of their idiolect features to create a more personable and approachable identity. This addresses the inclusion vs exclusion hypothesis, which examines how jargon might shape a group's sociolect among individuals who use it.

Immigrants and their self-identity Immigrants who settle in a place where a foreign language is spoken have distinct hurdles, which are often disregarded. Adults tend to assimilate the issue and have to cope with issues related to personal and cultural identity. When the dominant culture in the host country overlooks the immigrant's native language, the challenge becomes even harder. In her thesis on "The relationship between language and identity," Lourdes C. Rovira uses her own identity and experiences as an exiled Cuban, a teacher, and an administrator by profession, to address concerns about immigrant identification abroad. 'Our name, our national origin, and our citizenship constitute the most intimate parts of our being and identity,' says Rovira. People have fixed beliefs and presumptions, which are often not accurate, which determine whether we are embraced or neglected, accepted or rejected. However, who you are as a person and your distinctive characteristics are at the heart of self-identity.

Rovira emphasizes aspects of identity that pertain to the self as a member of a specific group, such as the identity of being an immigrant. The use of language and specific social experiences influence one's self-image. It is worth mentioning how culture plays a key role in developing a person's identity - shared values, conventions, and histories that are distinctive to an ethnic group have a great influence on the way a person behaves, thinks, and perceives the world. This is consistent with behaviorism theory, which holds that the development of a sense of self occurs parallel with the acquisition of language. Cultural identity, as defined by Rovira, comprises everything related to self, belonging, ideologies, as well as sensations of self-worth. Language is inextricably linked to cultural expression; it is the way by which we pass on the essence of ourselves from generation to generation. Rovira closes her ideas by saying, “Language – both code and content – is a complicated dance between internal and external interpretations of our identity.”

Language and social equality Language has left an influence on policy, research agendas, and society as a whole. Further, language reflects and sustains societal ideals and prejudices, and it is a potent tool for perpetuating inequities. For instance, websites, social media platforms as well and programmers on television.

It is typical for people to use improper or derogatory words to express their feelings toward other social groupings. For example, in 2017, Dany Cotton, the leader of the London Brigade, experienced severe outrage and online abuse when she advocated for personnel to refer to themselves as "firefighters" rather than "firemen." These are still indicators of inequity. Furthermore, while constructive steps have been taken to address blatantly biased language in which maleness is the standard ("mankind"), terminology such as gendered jobs and cultural attitudes remains difficult to dispute and alter. To address disparities in society, we must include individuals who are experiencing them and express concerns through our use of language; recent advancements in social media platforms have helped make this achievable.

In a nutshell, language plays a significant part in creating our self-image, altering our judgments, and, most crucially, establishing interpersonal connections with one another. In an instantaneous society like ours, it is essential to take the time to truly understand how the language that we use on a daily basis contributes to both our personal and societal identities.

0 notes

Text

Role Of Language And Culture In Today’s Society

Their teaching techniques and facilities are consistent with their objective of developing global understanding via high-quality education. SIFIL offers the finest classes for people interested in learning French, Spanish, or even Sanskrit language courses. SIFIL can help you break down linguistic barriers and expose your heart to a new culture!

People frequently begin their search for a French, German, Spanish, or Russian language course without realising its significance in culture and society. Language is both an individual and a social communication system.

The area of language and society - sociolinguistics - aims to illustrate how variables such as class, gender, race, and so on impact our use of language. Ethnicity, gender, geographic region, religion, language, and many other characteristics contribute to cultural identity.

Culture is often described as a "historically transmitted system of symbols, meanings, and standards." Knowing a language allows someone to immediately identify with people who speak the same language. This relationship is a critical component of cultural exchange. Languages and language differences have a role in both unifying and diversifying human civilization.

Language is a component of culture, but culture is a complex totality comprised of many disparate parts. The boundaries between cultural traits are not obvious, nor do they all coincide. Language is culturally transmitted, which means that it is learned.

If language is conveyed as a component of culture, it is equally valid that language shares culture as a whole. Language is entirely responsible for humans having a history in the same manner that animals do. Language may be used to transmit abilities, processes, items, social control methods, etc.

The end outputs of anybody's creativity can be made available to anyone with the intellectual capacity to grasp what is being said. Many people have accurately seen language as a barrier to gaining cultural knowledge. Even the most ardent supporters cannot comprehend the culture due to a linguistic barrier.

Language, on the other hand, may be utilized to immerse oneself in a new culture. You will be able to participate and engage with that group of individuals if you try to learn a new language. For any type of language instruction, professional courses from institutes with experience in such fields are required.

It will reduce your study tension, and you may also come across an institute that offers novel learning approaches, facilities, and skilled professors. SIFIL, or the Symbiosis Institute of Foreign and Indian Languages, is one of these well-known institutes.

SIFIL, a Symbiosis University sister company, was created in 2000 and provided certificate courses and programmes at the Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced levels in various foreign and Indian languages.

Their campus is a modern, well-equipped construction that covers an area of 2500 square metres. A library, three digital language laboratories, a 100-seat auditorium, two audio-visual conference rooms, a café, an ATM, and a primary health care centre are all available.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Calls: Journal of Arabic Sociolinguistics

The Journal of Arabic Sociolinguistics welcomes research which applies new theories and methodologies to Arabic data. We are particularly interested in articles that address the relation between linguistic variation and identity, variation and sociolinguistic variables (including but not limited to location, social class, education, age, gender and urbanization) and variation and political contexts . We also encourage submissions on code switching in the Arab world, language policy and the impac http://dlvr.it/T75H5J

0 notes

Text

Transcript 10: Down in the Holler

MEGAN: Welcome to the Vocal Fries Podcast, the podcast about linguistic discrimination.

CARRIE: I’m Carrie Gillon

MEGAN: And I’m Megan Figueroa. We have one housekeeping item: another email. It’s our third email. We’re just gonna keep counting. That’s how exciting that is. And it’s from the Ivory Coast. “Hello Carrie and Megan, I was listening to your Freaky Friday episode today and you gave a shout out to the Ivory Coast. So I figured I’d say “hi” and introduce myself as your listener in the Ivory Coast.” Wait. We have more than one, right?

CARRIE: Unless she’s downloading 50 copies of each episode or something, yeah, no, she’s not the only one.

MEGAN: To each their own. If that’s what she’s doing. Back to the email. “You probably looked at your stats and thought ‘huh, that’s weird’.”

CARRIE: Yeah, I did! That’s why I said it!

MEGAN: Yeah. That’s what Carrie did. Ok. “Anyways, I’ve listened to all but your most recent episode now, and I really enjoy them. I found out about you through Lingthusiasm.” Thank you, Lingthusiasm!

CARRIE: Thank you!

MEGAN: “And I’m really glad you have a show about this topic since it’s once I’m passionate about too. Although I usually come at it from a different angle. I’m an English teacher and teacher trainer and linguicism - the term I usually use for linguistic discrimination, although I usually have to include a gloss, since it’s unfortunately not in common use yet - is one of the areas I’m passionate about. Especially how it intersects with race and gender. Within TESOL, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, there are a lot of linguistic discrimination issues that come up, both in the discrimination that English learners face, but also in hiring practices that favor native speakers over non-native English speaking teachers. If you’re looking for new areas to cover for future episodes, the linguicism faced by language learners and language teachers and the role that native speakerism plays in perpetuating standard language ideology seems very much connected to the type of things you talk about on the show. Earlier this year, I actually wrote an article about this. If you’re interested, it’s online here.” And we’ll link to it. “Anyways, I thought I’d say “hi” and let you know I appreciate what you’re doing and enjoying listening from here in the Ivory Coast.” Thank you very much, Riah!

CARRIE: I like how she adds the pronunciation for us.

MEGAN: Yes, like rye bread, I love it.

CARRIE: I love it too. Thank you so much for that.

MEGAN: Yeah, I have to do that with my dog. My dog’s name is Rilo [rye-lo]. But it’s spelled like “real-o”.

CARRIE: Yeah. It could be pronounced either way.

MEGAN: Especially if you’re a Spanish speaker, right? Cuz there’s no ‘I’ sound in Spanish.

CARRIE: Or basically any other European language.

MEGAN: True.

CARRIE: English is the odd one out.

MEGAN: Always.

CARRIE: I also want to point out that Riah’s suggestion was also given to me by one of my former students, Edward. So this is clearly a topic that needs to be discussed. And it’s not just about native vs. non-native, it’s also about which varieties are acceptable and which are not. So you could be, say, an English speaker from India and that would not be the kind of dialect that schools would want probably.

MEGAN: Right.

CARRIE: So: yeah! I do think we should talk about it. It’s on the list!

MEGAN: Isn’t the British accent favorable?

CARRIE: English, North American.

MEGAN: Oh it is?

CARRIE: It depends on the school, depends on location, but there definitely - a lot of schools want American or Canadian teachers over some other varieties.

MEGAN: Well this is definitely something we should talk about, since _I_ have a lot of questions about it. I’m sure other people do too! Cuz I think from Twitter, from what I can tell, we do have a lot of TESOL English teacher-type listeners.

CARRIE: Yeah.

MEGAN: Very exciting. Alright!

CARRIE: And today we’re gonna talk about Appalachian /æpəlɑʧn̩/ or Appalachian /æpəleɪʧn̩/ English and we’re gonna ask our guest how it’s actually pronounced.

MEGAN: Yes. He’s from Appalaycha-lahcha.

CARRIE: This kind of reminds me also of Copenhaygen-hahgen /koʊpn̩heɪgn̩hɑgn̩/ [CG: Copenhagen]. Apparently, everybody pronounces it incorrectly. The way that they mock us for pronouncing it incorrectly is saying Copenhaygen-hahgen /koʊpn̩heɪgn̩hɑgn̩/.

MEGAN: Ohhhh. That’s fun. It’s also like - thinking about Arizona - if you say Prescott /pɹɛskət/ vs. Press-cott /pɹɛskɑt/.

CARRIE: Yes.

MEGAN: If someone says Press-cott /pɹɛskɑt/, you’re like, “oh, where are you from? It’s not Arizona.”

CARRIE: Speaking of that, there was an episode of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend where there was supposed to be a character from Prescott, and he pronounced it like Press-cott /pɹɛskɑt/!

MEGAN: No.

CARRIE: And I was like, “nope! Nope.”

MEGAN: See. Ya gotta get an Arizonan in the room. That’s what that means.

CARRIE: Yeah. Or even just ask.

MEGAN: Yeah!

CARRIE: If it’s just one word, one name, you don’t have to have someone in the room.

MEGAN: That’s true.

CARRIE: But maybe you should make sure that you really know how to pronounce the place names. Cuz place names are the most variable, I would say.

MEGAN: Yes. Don’t think that the easy obvious spelling is actually how you pronounce it. Cuz Prescott is like pretty obvio- it looks like “Scott”. I got you. Alright. I’m going to introduce our guest. Dr. Paul Reed is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communicative Disorders at the University of Alabama. He researches phonetics and sociophonetics, sociolinguistics, speech perception and language processing and other aspects of Southern and Appalachian /æpəlɑʧn̩/ or Appalachian /æpəleɪʧn̩/ Englishes. We want to ask you, Paul, how do you say that?

PAUL: For us, it’s always Appalachian /æpəlɑʧn̩/.

MEGAN: It’s always Appalachian /æpəlɑʧn̩/.

PAUL: Yeah. Now granted, if you go a little further north, if you go past West Virginia, then you may get some /leʃn̩/ and stuff like that, but it’s a bit of those that - so, growing up, the reason it’s always /lɑʧn̩/ for us - so, during the war on poverty, the Appalachian Volunteers, the AVs, they came into our region and they wanted to help. And so this was usually college students, but they also came with a bit of a “we know how to fix you”. And so a lot of them had /leʃə/. So growing up, it was always a marker of an outsider, usually with a particular view of our region that said /leʃə/. So it’s kinda one of those shibboleths for certain areas of the region, especially in southern Appalachia, where it’s a little bit more - it’s more rural and the poverty was more widespread. It didn’t get so much of the effects of the war on poverty until much later.

MEGAN: Ok so. Appa-lachia /æpəlɑʧə/.

PAUL: Yes.

MEGAN: Ok.

PAUL: We won’t kick you out or anything.

MEGAN: No, I mean I know. I’m sure it’s - I just do not want to signal that I think any less of anyone. But we’re so grateful for you to be talking with us today.

CARRIE: Yeah, thank you.

MEGAN: Thank you for being here.

PAUL: I’m thrilled to be here, thank you so much.

MEGAN: First off, I can put the two together and figure out what it is, but tell us what sociophonetics is.

PAUL: Sure. Sociophonetics is a branch of sociolinguistics. Sociolinguistics is looking at the intersection of language and social groupings, or language and society. Sociophonetics takes that and it brings it down to a phonetic level. It looks at how different groups of people, people with different identities, people from different areas, how they phonetically manipulate their production. Something as finely grained as how do your vowels change, the slight differences in consonant articulations, and things like that. It’s sort of this same kind of idea, but it’s done in a phonetic level. The only thing that makes it a little harder is - so, sometimes we want to exercise as much control over the stimuli or the recording as someone in a phonetics lab. But we also want the most natural speech possible. You try to use as much control as possible, in a way to - but at the same time, trying to get as natural. You try to move someone to the quietest room in their house, preferably with lots of curtains and carpets, and get away from things like fridges and air conditioners and stuff like that. And you might come up, and you hope for the best. I did have one recording - it’s funny, it’s a 94-year-old participant and she was great. But she was on an oxygen machine. We talked for a long time, but certain things I couldn’t do with her recording because - obviously I can’t ask her to turn that off. But I was able to use the qualitative stuff. It was one of those where I was like, “aw! So close!”

MEGAN: Isn’t it that the problem - well, I mean, not a problem - just like something to overcome a bit for all sociolinguists? The natural vs. are they - what is it called? speaker - when you’re there with them?

PAUL: Observer effect.

MEGAN: Yes. Yes, that.

PAUL: Yeah. That’s sort of an issue for everyone, but if someone - you could just unobtrusively set a recorder down, and people can forget about it. If you’ve miked them up and even if you - some people even put a mic connected to with the little over the ear thing, it’s harder to get them to forget about that, because they’re literally connected to. Although, the one thing - so, in my work, I was able to go back home. I was sitting across from people that knew me, that knew my parents, knew my grandparents. There was a bit of time where people just sort of forgot. Because they were sitting with someone they knew. They were sitting with Little Paul Reed, which, if you guys have ever seen me, that’s kinda a funny misnomer, cuz I’m about 6’8”. So it’s sort of - it’s kinda funny. Cuz everyone from my hometown calls me that, because my dad is Paul too, and he was Big Paul and I’m Little Paul. Even though I haven’t really been little for 20 years.

MEGAN: I’m guessing he’s shorter than you, too, at this point.

PAUL: Yes. He was about 6’4”.

MEGAN: Ok!

PAUL: So he was big, he just didn’t wind up as big as his son did.

CARRIE: You’re like Little John.

PAUL: Exactly. Exactly, yes.

MEGAN: So then would you say then that you speak Appalachian English?

PAUL: Yes. Yeah, I would say that I’m definitely a native speaker.

MEGAN: Ok.

CARRIE: One of the questions I have is: what are the boundaries for Appalachia vs. the rest of the South? And connected to that also is how is the language different from this region vs. the rest?

PAUL: That’s a great question. It’s always one of those that - so there’s the official designation of Appalachia, which is set forth by the Appalachia Regional Commission, a division of the federal government. There’s 410 counties over 13 states, stretching literally from about Jackson, Mississippi all the way up into western New York. People hear that and they’re like, “that’s huge!” But of course when most people think Appalachia, they don’t think all the way from Mississippi to New York. They think usually about - and we call it the core region. The whole state of West Virginia, southwest Virginia, eastern Kentucky, east Tennessee, western North Carolina, and a little bit, a smidge of the other states connecting. Northeast Alabama, north Georgia, maybe a little cut of South Carolina. That’s the core region and where people - that’s where the features are, there are more of them, that’s sort of the core region where people inside and outside the region would say, “that’s definitely Appalachia”. And as far as what differentiates it from the rest of the South, it’s really, honestly, most times, a quantitative rather than qualitative difference. Things like the Southern Vowel Shift, where you have the monophthongization of /i/. So in words like “price”, “pry” and “prize”, you’ll have monophthongization in all of those contexts at a much higher rate than in other areas. In large parts of the South, you’ll only get it in prevoiced and open syllables, so “prize”, “pry”. But in Appalachia, you’ll also get it in prevoiceless conditions, so “price”. And you’ll have it approaching categorical. There’s a lot of individual variation, which is what my work looked at. So that’s one of the features. But also, you have a few grammatical structures that occur more often or in more contexts. Things like double modals. That’s combinations like “might could” and “might should” “may can”.

MEGAN: Love that.

PAUL: You have those all over. “Might could” is pretty widespread. You get that from almost to Arizona all the way to-

MEGAN: I have it yeah.

PAUL: Yeah, all the way to the East Coast. But in Appalachia you have more of them in more conditions. I personally have “might could” “might can” “may can” “may could” “might should” “may should” “will can” “used to could” “used to would” “should oughta” “oughta should” “might should oughta”. And then I can also make questions. Things where - and this is where some of the work I’ve done starts to tease apart the difference between the core area and the periphery. When you make a question, usually you’ll take the second modal and move it. It’ll be like, “mmmm… should you might do this?” That’s the sort of typical way. Some people are just like, “no. That’s terrible. What are you doing, you’ve just butchered the language.” That’s sort of one of the things - being able to - all of the different combinations in a lot of different contexts. In more of them. And able to do things like form questions. Or where you put the negation, cuz you can say “might not should” or “might should not”. “Might couldn’t.” So how much contraction you allow and where you allow the negation to appear is sort of one of the features that starts to distinguish the region. Along with, of course, a lot of lexical items. This is where it gets fun. Because it’s a region with a lot creativity. People do a lot of things that aren’t necessarily completely unusual, but it’s very creative. I remember growing up, people would say things like, “man, he’s he workingest man I ever saw.” And you’ve basically added a superlative to “working”, which is interesting. And of course people can immediately parse what you mean. But it’s not necessarily something you’re gonna produce. And some other lexical items, there’s all sorts of terms for things. I was teaching this a couple of weeks ago to my students. Most of them are from the South, cuz we’re at the University of Alabama. Lot of people are from the South. One of my students is from northeast Alabama. In Appalachia. She said, “Dr. Reed, do you know all the words for ‘moonshine’?” I know some of them. So we started comparing the words we have for “moonshine”. So of course you’ve got “shine”, “moonshine”. This is my personal favorite: “Oh Be Joyful”.

CARRIE: That is great. I’ve never heard that before.

PAUL: So people will say, “you got any Oh Be Joyful?” That’s another one. One other - and this one I didn’t even realize until I was in graduate school. That not everyone uses this. It’s called the “alternative one”. It’s very common to say something like, “yeah, you know, we should probably do that Monday or Tuesday one.” In the sense of “one or the other”, but you put both options and then “one” after it and the interlocutor would understand “oh, you’re giving me a choice here.” But not everybody does that. I remember saying that to a friend of mine and got this blank look of “I don’t think I know what you mean.” There are some features that are not necessarily unique but they’re quantitatively different. There are some that are probably on the border of being qualitatively different, but it’s kinda hard to say because the borders are definitely sort of fuzzy. And the closer you get to the core, that core area that I was talking about, people will have more of them and in more contexts.

MEGAN: So then would you say that non-linguists, or people just listening to a Southern American English speaker and then an Appalachian English speaker, would they be able to tell the difference? Or you have to be more of a trained ear.

PAUL: You can tell the difference, but what you often get is somebody’ll say, “you sound REALLY Southern.” Or “you sound REALLY country.” Or for whatever reason people will also think you’re from Texas. So you get, “are you from Texas?” No. We Tennesseans, we saved Texas. The only reason that they’re - we saved them. When I lived in Texas, I made sure I brought that up as much as possible. Which was probably a faux pas, but it’s alright.

MEGAN: Ok. So their dialect is gonna be different from yours.

PAUL: There’s some - in east Texas, cuz there were a lot of people from the mid-South that went to Texas. East Texas, in and around Houston and a little further north, there were a lot of Tennesseans and eastern Kentuckians and those that went. So there are some similarities. It’s not completely off the wall, but it’s definitely something that’s shifted and morphed, cuz we’re talking about the 1830s and 1840s. There’s been a lot of change. But people will say things like, “you sound REALLY Southern.” That’s usually what you get. It’s not necessarily that they don’t recognize - they recognize there’s a difference, but they don’t really know what that difference is. Sometimes within the South, you may get the “country”. Somebody sounds really country. And that’s what you get a lot. Because in the South as a whole, there’s a big urban/rural divide. A lot of the cities have really grown in the last 50 years. The distinction between urban/rural has grown. You get a lot of that, “you sound really country, are you from the sticks?” or “Are you from the boonies?” That kind of stuff. There’s some notion that it’s not necessarily associated with urban areas. Very rarely does somebody say, “are you from Appalachia?” Usually you’ll get “are you country?” In a lot of people’s minds, it’s kind of the same thing.

CARRIE: Also, mountain folk, right?

PAUL: Yes. You’ll get some mountain folk, but that’s usually from people very close to the region that live and they’ve been able to see that distinction. Even though, for example, where I went to college in Knoxville, Tennessee is considered part of Appalachia, very close by, people would know that “oh you’re from the mountains.” Knoxville’s in the valley, and within Appalachia, the valley and mountain or valley and ridge distinction is pretty salient. As Appalachia was settled, people settled in the valleys first. That was where there was better land, and you had people of a certain means, you could get some land in the bottom land along the rivers and valleys. If you came a little bit later, or if you didn’t have as many resources, you had to get higher and higher, cuz the land was cheaper. And so there’s a distinction. Even to this day, there’s a little bit between the valley and the ridge. My wife is from they valley and she’s not - we grew up maybe 50-60 miles apart. Not very far. But there are certain things that I say that she doesn’t say. Certain idioms and sayings, and sometimes the way that we say things is a little distinct. Which is kinda funny, cuz again, we’re both from east Tennessee, we’re not from that far apart. But there’s definitely some distinctions.

CARRIE: Cool!

PAUL: I mean like anywhere, anywhere has distinctions. But in people’s minds, people are like, “oh, you’re both from east Tennessee, you’re both gonna sound the same.” No, not really.

MEGAN: Do you think people are picking up on the phonology, the lexical items, what is it that they’re picking up on when they say “are you from the boonies?” What is it that they’re picking up on?

PAUL: I think, the times it’s happened to me, it’s usually been a combination. When I’ve said something with my phonology, but it’s a saying or a grammatical structure that they’re not familiar with. Another time when I was in college, one of my teammates, he was - I played basketball - so he needed a ride to the airport. And I said, “sure man, I don’t care at all to take you.” He’s like, “ok, I’ll go with somebody else.” I’m like, “why would you do that? I just told you I’d take you.” “No you didn’t, you said you don’t care to take me.” And I said, “exactly. I don’t care at all. I’d love to take you.” He just gave me this blank look, that doesn’t compute, man. It was one of those - we had sort of a misunderstanding. I thought, with my intonation and facial expression, that he knew that I was gonna take him. Things like that. That’s when he was like, “you country people.” Which was a joke. My teammates would call me the mountain man, or Paul Bunyan. That’s sort of part of that, is it’s literally a joke. But there was something like that. I think a combination of the phonology and something that took a minute, there was a little bit of a miscommunication.

CARRIE: Yeah, I would have interpreted it the same way he did.

MEGAN: Yeah, me too.

PAUL: So if someone is from Appalachia, potentially other parts of the South, “I don’t care to” is not always negative. Especially with a “I don’t care to take you at all!”

CARRIE: That’s interesting. One of the things - one of the reasons we wanted to talk to you is because - whatshisname - JD Vance was back in the news.

PAUL: Yes.

CARRIE: Do you have any feelings towards his work?

PAUL: I have lots of feelings about JD Vance. Some of them will probably need to be edited slightly. No, I'm just kidding.

CARRIE: You can swear if you want. We swear on this.

MEGAN: We have an explicit rating.

PAUL: JD Vance is, he’s full of what makes the grass grow green in lots of ways. Because the main thing is is that if his autobiography were his own story, the story of a child from a broken home that got access to education, had some people that mentored him, and made good. He was able to attend some fine colleges and he did well for himself. If that were his book, then it would be great. But the fact that first and foremost, a 30 year old is writing an autobiography - and not an autobiography. He’s writing an elegy for an entire region. And a region, he didn’t grow up in. He’s from Ohio. He grew up in Ohio. He spent summers and he spent time back in Kentucky, but he did not grow up in the region. And trying to put his experiences, and the experiences of his mother, with all of her demons and all of her issues, as somehow indicative of an entire region - even if you’re looking at just the core region, you’re talking about 6 states. Millions of people. And basically saying, “hey, this is what they’re all like. They’re all fighting, and they’re all violent, and they’re all drug addicts.” That part is infuriating. Because that is the same trope that’s been going on for 150 years. In the period after the civil war, there was this kind of literature called Local Color. It was journalists from urban areas, like Baltimore and DC and other places, and they wanted to write about interesting places around the country. And because Appalachia wasn’t that far away, they would go, and they would seek out the people who were the most different. And so of course, it’s looking at people who were impoverished, people that were barely scraping by. They would write stories about them. And those stories would be very the same thing, how some people make good, some people are able to escape. But it’s the culture of poverty, it’s the culture of deprivation, it’s the culture of this. And that’s painting this brush. And even though people just up the holler from them are completely different, their reality is completely different, they paint everyone with the same brush. Some of these stories sold like wildfire. Because they were in Harper’s, they were in the Atlantic, and other things, so these magazines that we still have to this day, but they sold. It’s literally the exact same trope of it wasn’t drugs, it wasn’t opioids back then, but it was the moonshiners, and the impoverishment. Because they were Scotch-Irish, they liked to fight, cuz they were all clannish. And it’s stuff of just like - this is like a zombie trope. We just need to slay it and let it die. But it just won’t. That’s my biggest issue. Again, his story is incredible. What he faced and the way he was able to overcome it was very inspiring. But when you try to say that the way that you grew up is the way that everyone grows up and the demons that your parents, and his mother faced, are the same demons that everyone faces, that’s where it gets annoying. And then also the fact that he footnoted his own autobiography. You don’t footnote an autobiography. You’re not pointing out research when it’s about your own life. That’s the thing that’s irritating. And then the fact that he’s somehow become the voice of the region. And there are scholars that have been working in the region and are from the region that have been writing for 50 years, people like Dwight Billings at Kentucky, and people like Anita Puckett at Virginia Tech, Mimi Pickering at Appalshop. There’s just so many people that have written and told a story and a nuanced story and a complicated and complex story. But that doesn’t sell as much. And it’s - no one likes to hear “hey, it’s so difficult because you’ve got extractive industries, you’ve got poverty, you’ve got rampant capitalism.” And then you’ve got other things that - frankly the fact that JD Vance has become our voice just pisses most of us off. In a way that is - so I’m a member of the Appalachian Studies Association and I think he’s been invited at least twice now and has yet to appear. I don’t know if it’s just that he - if it’s one of those - he just can’t fit it into his busy schedule. Strangely enough he’s still able to be on other networks and stuff. But anyway. JD Vance is - he’s not - he’s irritating.

MEGAN: These tropes that he’s reinforcing, it wasn’t just - they were persisting before him. If feels just kinda like - he’s bringing it into a national spotlight even more. Is that true?

PAUL: Yeah.

MEGEAN: Ok.

CARRIE: And it’s keeping it - it’s still perpetuating now. Everyone goes and interviews all these Trump supporters from the particular region and it’s all the same kind of - or at least intersecting tropes. It just keeps happening.

PAUL: Yes.

MEGAN: Right.

PAUL: And again, people in certain parts of Appalachia, their lives haven’t changed in 50 years. They’re worse off than their grandparents were. Or on par. Because of stagnant wages and with the decline of coal and the decline of timbering and things like that, certain industries are dying. And it IS sad. But at the same time, that’s not everybody. Some of the stories and the way that they’re written are so patronizing. That’s the thing that’s irritating. It’s like, “oh, we’re gonna go find some of the towns in West Virginia that have been decimated.” Because once the coalmines closed, people had to leave. If they didn’t have a way to make any more income. So they did leave. So some of these towns are hurting, and hurting badly. But, that’s not everybody. You don't see anyone rolling into Knoxville or to Chattanooga or to Asheville or to Lexington or other places that are thriving - Greenville, South Carolina, which is technically part - those cities are doing very well. And not just the cities, their suburbs, and you don’t get the stories from there of the successes that are going on. Or the thriving small towns that are making a difference. That’s the story that’s not told. And that part is sad and frustrating, because the region has been exploited for 300 years, particularly the last 150 years, and so much of its wealth and its beauty have left because of absentee ownership and other things that - it was almost - some writers have described it as an internal colony. Because so many of the resources were taken away and the riches produced weren’t reinvested back in the region. And there’s lots of reasons for that. The natural resources were taken but the people were not - they didn’t reap the benefits of that.

MEGAN: So do you think that that’s the biggest stereotype or misconception about people from the region is the impoverished kind of trope that’s -

PAUL: I think so. Normally - there’s kinda two big tropes. They’re sort of flip sides of each other, but you’ve got the degenerate hillbilly, poor, no shoes, no teeth. Shiftless, lazy. All of those. Then you also, on the flip side, sometimes when you say “Appalachia” people think tradition, it’s almost a positive thing, like “ooh, it’s pretty, traditional values” in some ways. So you get - sometimes there is some positive thing. They are obviously outweighed by the negative, but you can get this yin and this yang or this Janus idea of two sides. But if you were ever to google search “Appalachia”, and look at the images, for every 10 hillbillies there’s one “ooh, look how pretty”. Or you get these obviously all of the caricatures and stereotypes. So I think that that’s - the impoverished and the hillbilly, kinda go hand in hand. You do get some positive things, and those are - even in Vance’s book, he talked about the family togetherness and the independence. Some of those, even though as is portrayed in his book are negative, you can pull positive things from that. I guess I should - my small caveat, it’s not all negative in his book. Just mostly.

CARRIE: One of the words that you used in that discussion was “holler” which I definitely associate with Appalachia.

PAUL: Yes! Yes! I think it can be called a “hollow”, but if you say “hollow”, no one knows what you’re talking about. So it’s a “holler”. And it’s a - I don’t exactly know the strict definition of what a “holler” is. I can point some out to you but I don’t know.

CARRIE: I always interpret them as small valleys. But maybe I’m wrong.

PAUL: It’s a small, long valley that - usually there’s one way in but there’s land that’s arable and useable and people can live close or far. And usually as you’re going in, you’re going up too. So if you’re deep in a holler, you’re probably moving up the ridge.

CARRIE: Oh! That’s interesting.

MEGAN: It’s good that that was cleared up because I heard it and I was like “I don’t know what’s happening!”

CARRIE: The first time I ever heard the word was in - not Longmire. What’s that tv show about the federal agent. From Kentucky? Right? Tennessee?

PAUL: Justified?

CARRIE: Justified! The first time I ever heard that word, I think, was Justified. And I had to look it up.

PAUL: Yup. Now Justified is actually decent. I will say that’s a show that I can watch and reasonably enjoy. Obviously some of the bad guys are so over the top and it’s almost like, really? But for the most part it’s a reasonable display of the region. It’s obviously not perfect, but it’s pretty good. As far as-

MEGAN: What about the dialect?

PAUL: It’s decent. They did get a lot of extras from the region itself and so a lot of those are fairly good. Obviously, some of the stars aren’t necessarily from the region, so theirs is - most of the time, any time you get an actor and try to teach them, certain things’ll be really good. And then other things will be “meh”. It’s oftentimes like - the Southern accent just as a whole is hard, just because there’s a lot of nuance there. A really good version is Jude Law in Cold Mountain. A really terrible version is Jake Gyllenhaal in October Sky. I almost had to stop watching the movie. I’m like, “this is terrible.” Oh man. It was - he was giving it a decent try, but it’s like man. As linguists, we gotta do some more work. We gotta some work. Cuz it was not good. Not good at all.

CARRIE: What do you think people are judging when they judge you or other Appalachian speakers for their dialect?

PAUL: I think it’s two things. Obviously, first and foremost, you’re - we’re all raised in this culture, we’re all presented with these stereotypes, we’re presented with these ideas - because not everyone has experience with the region. And so just like most human things, we try to categorize. Based on what we’ve been told. If you are inundated with this idea of hillbilly and poor and backwards and Trump country to the nth degree, with a little sprinkling of very pretty and traditional and things like that. Which, some of those are even reinforced. I think that’s what we do, the same way that those of us who grew up in the region that may not have had any experience with New York or Boston or the Midwest, what do you have to default to, what have we absorbed from our culture. Some of that is positive about certain areas and some of it is also negative. Sadly for Appalachia, a lot of it is negative. We’re inundated with a lot of negativity, sprinkled with some positivity. But that’s what we default to cuz that’s the only thing we have. And of course we like black and white answers. We like good or not so good. But when something is complex and nuanced and there’s lots of gray and not just black and white that’s what people - so for example, people hear me sometimes, and they hear that I’m a PhD and I wear my shoes and I have my teeth, there’s some cognitive dissonance there, like, “what happened? Wait a minute, you’re not a blatant racist, or misogynist, or things like that. What do we do with that? And you’re not poor.” Not that I’m rich, but “you’re not dirt poor, living on a dirt floor.” It’s weird. I was on an athletic visit to New York City, and I was there and one of the guys was like, “hey man, so you’re from Tennessee!” And it was like, “yeah.” And he looked at me and said, “do you guys have phones there?”

CARRIE: HA!

PAUL: And I just kinda look at him and I said, “nope! We got two cans and a big long string.” But it was - granted, this is a guy that grew up in - I think he may have been from the Bronx - he had no notion. So the only thing that he had was the caricatures. And so he asked somebody literally in the year 2000 if they had phones. Which is obviously an absurd question. But it’s indicative of what did he - I was the first person from Tennessee that he knew that he had met. So what is he gonna do? He’s gonna default to what he’s been presented. And sadly that picture from a lot of pop culture and the cultural milieu is negative, and so that’s what he did. And of course back then I didn’t have any notion of how to answer this so I also proceeded to insult him about New York and thoity-thoid street and things like that. Again that was my first trip to New York so I had to default to my stereotypes too. That’s not my proudest moment, but that's just being transparent.

CARRIE: Well sometimes when you’re put in these situations, you just don't know how to respond.

PAUL: Exactly.

CARRIE: I wouldn’t have known.

PAUL: I was 17 so I really didn’t have a lot of world experience in how to navigate something like that. Although I will say I do have one funny story about a guy, a good friend of mine. He’s probably the smartest guy I know. He’s an agricultural engineer and he’s basically figured out ways for us to feed to the whole world, this is what he does. We were at this McDonald’s, we were on a trip and we were coming back from Saint Louis. I don’t really remember where we were. But we weren’t very close to home. My friend has a pretty pronounced Appalachian accent. He just lets it fly cuz that’s who he is and that’s who he wants to be. He ordered his food. And this guy behind him starts laughing. Then my friend turns around and says, “can I help you?” And the guy said, “what rock did you crawl out from under?”

CARRIE: Oh my god.

PAUL: And my buddy - he’s so funny, he’s so quick with this - I don’t know how - but he’s like, “let me ask you something. Do you know what an algorithm is?” And the guy’s like, “uh, no.” He said, “can you tell me what a derivative is?” And he’s like, “no.” He said, “I didn’t think so.” He said, “just cuz my mouth move slow, doesn’t mean my mind does. But apparently yours does.” And then he walked off. And it was kinda like - that was-

CARRIE: Wow.

PAUL: Terrible and amazing at the same time. Both really insulted and then I’m like, “dude, that’s like the best comeback I’ve ever heard and how did you think of that?” And he just walks with his tray and sits down. He’s like, “*sigh* we get all kinds.” And it was funny cuz he was not really upset after that, and I was like, “wow.” But what did that guy - what was his stereotype. It was, if you hear someone talking like that, they’re from so far country, so deep in the country that they live under a rock. That’s what he defaulted to. It was a really just eye opening - it’s kinda like - I wanted to be his yes man but I didn’t really know what to say so I’m like, “YEAH.”

CARRIE: TAKE THAT.

PAUL: That’s my friend!

CARRIE: Yeah. One of the things that I hear a lot is that people from the South and Appalachia, they talk lazy.

PAUL: Oh yes.

CARRIE: Can you explain why it’s not lazy.