#irish times

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“I actually made half of a record for him,” he says. Tomlinson’s team “had a lot of songs but maybe not a lot that he was as into as he wanted to be. I think they were maybe looking for a weirdo. So they reached out to me. I love him. He’s a fascinating human being. I absolutely loved making that album.”

- James Vincent McMorrow: ‘I’ve been building back a version of me that made me happy rather than crying every night’ The Irish Times [30.11.2024]

#james vincent mcmorrow#louis update#louis press#irish times#30.11.2024#Louis songwriting#faith in the future#louis tomlinson

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#st patrick's day#st paddy's day#st patrick's cathedral#st pattys day#irish music#irish mythology#notre dame fighting irish#irish history#irish#ireland#dublin#belfast#irish american#conor mcgregor#irish memes#irish politics#irish pub#irish folk music#irish folklore#irish women#irish girl#irish songs#irish news#irish culture#irish studies#irish sea#irish times#irish reunification#irish rock#irish whiskey

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the tracks they wrote together, The Greatest, would serve as the opener to Tomlinson’s second LP, Faith in the Future. As is often the way with the music industry, the rest are in a vault somewhere. Still, for McMorrow the opportunity to work with a pop star was about more than simply putting his craft in front of a wider audience. The call from Tomlinson’s team had come at a low point for the Irishman, who had become mired in confusion and doubt after signing to a major label for the first time in his career.

— Irish Times

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Global ecosystem breakdown and soaring temperatures require us to think outside – and against – the framework of our current political system. If we want the children of today to have a future on this planet, we cannot keep obediently colouring inside the lines." - Sally Rooney

CLICK HERE to read the full article over on The Irish TImes.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

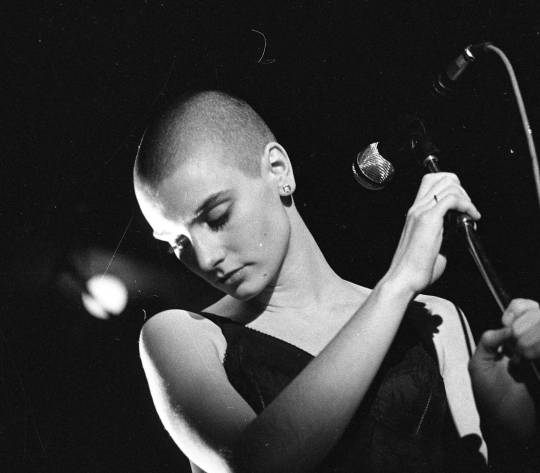

(via Sinéad O’Connor, acclaimed Dublin singer, dies aged 56 – The Irish Times)

The acclaimed Dublin performer released 10 studio albums, while her song Nothing Compares 2 U was named the number one world single in 1990 by the Billboard Music Awards.

Ms O’Connor is survived by her three children. Her son, Shane, died last year aged 17.

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…freshly baked sourdough loaves”

I’m dying here 😂🤣

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture from Charlene's interview in The Irish Times 🥂

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the trans activists fooled Ireland - UnHerd

Ireland is the trans activists’s trump card. Whenever debate flares up about self-identification or the Gender Recognition Act or transgender rights, campaigners can say “There has never been any trouble in Ireland.” And governments believe them.

The Irish “success story” has been trotted out and swallowed down whole. Ireland was an early adopter of “self-ID”: since 2015 the state has allowed individuals to change their “gender” — their legal sex, effectively — just because they want to. There are no background checks and no medical reports.

Let’s be clear, that is an affront to safeguarding. But that has not stopped activists claiming Ireland to be an example of “international best practice”, and framing it as a great model for Westminster and Holyrood. But while politicians may still be lapping up whatever activists tell them, recent polling suggests that the Irish public is not convinced.

It does not take a legal expert to see the dangers. If biological males can access women’s single-sex spaces including hospital wards and prisons simply by making a statutory declaration, it was only a matter of time before there was an outrage. In fact, there have been at least two in one prison.

Barbie Kardashian is a troubled teenager who was “born a male but identifies as female”, and has a history of particularly nasty physical and sexual violence towards women. Having previously torn the eyelids from a female care worker, Kardashian was jailed last year in the women’s wing of Limerick prison following threats of violence against two individuals. According to the court report, Kardashian was “very anxious she be detained in a prison facility for females, as she identifies as a female”.

Already there was a “pre-operative, pre-hormone therapy”, male-to-female transgender prisoner who had been convicted of ten counts of sexual assault and one count of cruelty against a child.

Whatever Irish politicians had been thinking when they waved through the 2015 Gender Recognition Act, there had not been any proper public debate to inform the new legislation. But that is not surprising; the law was changed swiftly and quietly, just the way the activists like it.

“Nobody spoke about the GRA,” says the Irish writer Stella O’Malley. It wasn’t even mentioned in the media: “We were all about the gay marriage referendum and the GRA just didn’t come up. I’ve always been interested in trans issues and I would have noticed if it had.”

This strategy is straight from an activists’ handbook, or to be precise the “Denton’s Document”. This guidance – officially titled, Only adults? Good practices in legal gender recognition for youth – was published two years ago. Backed by an unlikely triumvirate of Dentons (the world’s largest law firm by number of lawyers), Thomson Reuters Foundation and IGLYO – the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Youth & Student Organisation – it was an instruction manual for lobbying groups who wanted to extend gender recognition to young people with or without their parents’ permission.

The tactics are detailed in full within the handbook, including the instruction to “avoid excessive press coverage and exposure.” And specific reference was made to Ireland where, “activists have directly lobbied individual politicians and tried to keep press coverage to a minimum.”

O’Malley was right: the events of 2015 had been carefully managed.

“In Ireland, Denmark and Norway, changes to the law on legal gender recognition were put through at the same time as other more popular reforms such as marriage equality legislation. This provided a veil of protection, particularly in Ireland, where marriage equality was strongly supported, but gender identity remained a more difficult issue to win public support for.”

It’s only now, six years on from the Irish Gender Recognition Act, that the public has been consulted. Not by the government, even now, but by The Countess, an Irish campaign to restore the privacy, dignity and safety of women and children in schools, workplaces, sport, changing rooms, toilets, hospitals, prisons and refuges. Opinion polling carried out for them by Red C – found that respondents were not impressed.

Only 17% agreed with the 2015 law that allows someone to change their birth certificate as soon as they self-identify as the opposite sex. Rather more (34%) thought it should be permitted once a trans person has partially or fully transitioned through hormone treatment and/or genital surgery. But 28% felt that individuals should not be allowed to change the sex on their birth certificates at all.

Even younger people (aged 18-34) favoured no changes to birth certificates, as opposed to the laissez-faire approach that was pushed through parliament. Overall, men were more cautious than women — perhaps because they better understand what men can be like.

Birth certificates are the last line of defence for service providers trying to maintain single-sex provision for women. If these can be changed on demand, then the safeguards become worthless. We can probably safely assume that few men would ever seek a Gender Recognition Certificate but mixed in with those suffering from gender dysphoria — a diagnosable medical condition — would be those who women need to worry about most. There’s little point of locking a door if a potential abuser can cut his own key.

As the polls show, while Irish politicians were captured by the transgender activist lobbying, the Irish public understands the dangers. When asked about transgender people who had not been through gender reassignment surgery, more people than not opposed their inclusion in changing rooms, sports, refuges and prisons. Clearly, the naïve government policy that led to the outrage in Limerick women’s prison is not supported by the electorate.

Laoise Uí Aodha de Brún, founder of The Countess said, “This is the first time the public has been given a say on gender self-identification. When the government passed the Gender Recognition Act in 2015 it did so with little thought of the effect it would have on the wider community, let alone consultation with groups that would be most affected, particularly women.”

This does not mean that The Countess and the Irish public are transphobic. Rather they are pro-science, and supportive of the rights of women to defend their own boundaries. As a transgender person myself, I know transphobia when I see it and this is not it. It is not hateful to make factual claims such as “transwomen are not female and therefore not women”, nor is it transphobic to apply safeguarding procedures appropriate to an individual’s biological sex. That is necessary to protect everyone’s welfare. Accusations of transphobia are thrown around far too easily and they deflect attention from genuine hate.

Unfortunately, though, the Irish self-identification “success story” has been misrepresented and disseminated by activists who are desperate to extend it far and wide. On this side of the Irish sea, the Westminster government has, to their credit, thrown out self-identification, despite the howls of protest from some quarters — but gender recognition is a devolved matter. North of the border, Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP government seems determined to make the same mistakes as the Irish one, despite the furore surrounding the debate. Scotland has already cited alignment with “international best practice” as a rationale for introducing self-identification, using Ireland as an example.

All these leaders have been hoodwinked by a narrow group of self-interested activists who have seized the agenda and are loath to let go. I’m a teacher and my pupils are taught to think critically. Some of our politicians need to learn a similar lesson. Instead of following blindly, then need to start asking themselves some hard questions. I suggest they kick off with “Who told us that self-ID was international best practice and why did we believe them?” Because this polling suggests that their electorates would like some answers.

#Transgender Movement#Ireland#Women's Rights#Cillian Murphy#Andrew Scott#Barry Keoghan#Colin Farrell#The New Masculinity#Irish Times#Irish Independent#Trans Identified Males#Child Safety#McGuinness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“With Louis it was like boot camp. I had a very limited time with him. I had to wake up every morning, go for a run, write a song in my head, go to the studio. We made songs all day long. It lit a fire in my head again. I loved the process. I like sitting and talking to someone like Louis, who’s had this unbelievably fascinating lifestyle – so much tragedy in his life,” he says. Tomlinson’s mother and sister died within three years of each other, and his 1D bandmate Liam Payne died in October. “So many things have happened to him. I chatted to him and then write constantly. That was a lovely process.”

- James Vincent McMorrow: ‘I’ve been building back a version of me that made me happy rather than crying every night’ The Irish Times [30.11.2024]

#james vincent mcmorrow#louis update#louis press#louis tomlinson#30.11.2024#irish times#Louis songwriting#faith in the future

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Harries don’t give much of a sh*te, to be quite honest. And why should they?" 😄

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

During the pandemic the songwriter and producer James Vincent McMorrow would rise early, go for a run and write songs for Louis Tomlinson, of One Direction.

“I actually made half of a record for him,” he says. Tomlinson’s team “had a lot of songs but maybe not a lot that he was as into as he wanted to be. I think they were maybe looking for a weirdo. So they reached out to me. I love him. He’s a fascinating human being. I absolutely loved making that album,” adds McMorrow, who is about to start a tour of Ireland.

When it comes to potential collaborators with a boy band megastar, McMorrow’s name is not the first that springs to mind. He’s an indie songwriter whose open-veined, falsetto-driven pop has been compared to that of folkies such as Bon Iver and Sufjan Stevens. But Tomlinson was a fan of the Dubliner’s beautifully wrought music. He wasn’t alone: Drake famously sampled McMorrow on his 2016 track Hype.

One of the tracks they wrote together, The Greatest, would serve as the opener to Tomlinson’s second LP, Faith in the Future. As is often the way with the music industry, the rest are in a vault somewhere. Still, for McMorrow the opportunity to work with a pop star was about more than simply putting his craft in front of a wider audience. The call from Tomlinson’s team had come at a low point for the Irishman, who had become mired in confusion and doubt after signing to a major label for the first time in his career.

Executives at Columbia Records had recognised potential in McMorrow as an artist who bridged the divide between folk and pop. The fruits of that get-together would see daylight in September 2021 as the excellent Grapefruit Season LP, on which McMorrow teamed up with Paul Epworth, who has also produced Adele and Florence Welch.

The album was a beautifully gauzy rumination on the birth of his daughter and the muggy roller coaster of first-time parenthood. It went top 10 in Ireland and breached the top 100 in the UK. Yet the experience of working within the major-label system was strange for McMorrow, who at that point had been performing and recording for more than a decade. He didn’t hate it. But he knew he didn’t ever want to do it again.

“It was a weird time. I stopped touring in 2017. My daughter was born in 2018. I signed with Columbia Records at the same time and made a record that ... There were moments within it I was proud of. But fundamentally, I think if I was being very honest, I would say that I definitely got lost in the weeds of what the music industry wanted for me rather than what I wanted for myself.”

Finding his way out of the weeds involved putting out The Less I Knew, a mixtape of tracks, in 2022, and, in June 2024, Wide Open, Horses, the official follow-up to Grapefruit Season. It’s a fantastic reboot from an artist who has found his way into the light once again. The album showcases McMorrow’s propulsive voice – imagine a goth Bee Gees – and his ability to turn a diaristic observation about a tough day into musical quicksilver, as he does on White Out, a blistering ballad that draws on his experience of suffering a panic attack while out at the shops (“white out on the city street ... pain comes from strangest places”).

He workshopped the project with two concerts at the National Concert Hall in Dublin in March 2023, performing the as-yet-unfinished record all the way through. The risk of something going amiss was significant – which was why he did it in the first place.

“Those shows, that process was me very much back on my bullshit,” he says, meaning that, having tried to fit into a corporate structure, he was embracing his old idiosyncratic methods once again.

“I’m the worst sort of career musician in a lot of ways. I do the weird thing. I like doing things that make me interested selfishly. ‘I’m engaged with this process.’ ‘The stress of this is making me feel the way that I want to feel.’ And I’d lost that. Doing those two shows was me doing something where I was, like, ‘There’s stakes to this’ ... ‘If I f**k this up, people are going to see it.’ That brings out the best in me.”

McMorrow grew up in Malahide, the well-to-do town in north Co Dublin; as a secondary-school student he suffered debilitating shyness. In 2021 he revealed that he had struggled with an eating disorder at school, ending up in hospital (“Anorexia that progressed into bulimia”). He was naturally retiring, not the sort to crave the spotlight. But he was drawn to music. “It was definitely a difficult journey,” he says. He wasn’t alone in that. “The musicians that tend to cut through and make it ... A lot of my friends, musicians that are successful, they’re not desperate for the stage.”

The Tomlinson collaboration was part of his strange relationship with the mainstream music industry. It went back to McMorrow’s third LP, Rising Water, from 2016. A move away from his earlier folk-pop, the project had featured engineering from Ben Ash, aka Two Inch Punch, a producer who had worked with chart artists such as Jessie Ware, Sia and Wiz Khalifa.

That was followed by the Drake sample in 2016 and by McMorrow writing the song Gone, which was at one point set to be recorded by a huge pop star whom he’d rather not identify.

“Gone is the red herring of red herrings in my entire career. I wrote that song for other people. I didn’t write it for myself. The whole reason I signed to Columbia Records and I had all these deals was because of Gone. I was very happy tipping away in my weird little world. And then I wrote that song, and a lot of bigger artists came in to try to take it,” he says.

“I won’t name names. There were recordings of it done. It got very close to being a single for someone else. I would go in these meetings with all these labels, and I would play it for them – just to play. Not with any sense of ‘This is my song.’ And they were, like, ‘You’re out of your mind if you don’t take this song. This is the song that will make you the thing that is the thing.’ And I was, like, ‘You’re wrong.’ For a year I basically was, like, ‘I disagree.’ And if you go in a room with enough people enough times and they tell you that you’re crazy ... I loved the song, but I did not love it for me. I never felt I fit. There was a little part of me that wanted to believe.”

As he had predicted, Gone wasn’t a hit. He received a lot of other strange advice, including that he cash in on the mercifully short-lived craze for NFTs by putting out an LP as a watermarked internet file. All of that was swirling in his brain when Tomlinson got in touch. To be able to step outside his own career was exactly what McMorrow needed.

“With Louis it was like boot camp. I had a very limited time with him. I had to wake up every morning, go for a run, write a song in my head, go to the studio. We made songs all day long. It lit a fire in my head again. I loved the process. I like sitting and talking to someone like Louis, who’s had this unbelievably fascinating lifestyle – so much tragedy in his life,” he says. Tomlinson’s mother and sister died within three years of each other, and his 1D bandmate Liam Payne died in October. “So many things have happened to him. I chatted to him and then write constantly. That was a lovely process.”

Because life is strange and full of contrasts McMorrow ended up working with Tomlinson around the same time that he was producing the Dublin postpunk “folk-metal” band The Scratch, on their LP Mind Yourself. “Totally different animals,” he says. “The Scratch album was an intense period in the studio of that real old-school nature of making music. A lot of fights. A lot of pushing back against ideas. A lot of different opinions. And you have to respect everybody’s opinions and find the route through.”

During his brief time on a major label, McMorrow was reminded of the music industry’s weakness for short-term thinking. In 2019, the business was obsessed with streaming numbers and hot-wiring the Spotify algorithm so that your music posted the highest possible number of plays.

“Everyone was driven by stats. ‘This song has 200 million streams.’ ‘That song has 400 million streams.’ I went into my meetings with Columbia Records ... the day I had my first big marketing meeting was the day my catalogue passed a billion streams, which, for someone like me, who started where I started, was a day where I should be popping champagne corks. Instead they immediately started talking about how they have artists that have one song that has two billion streams. So by their rule of thumb I was half as successful as one song by one artist on their label.”

Five years later he believes things have changed. He points to Lankum, a group who will never set Spotify alight yet who have carved a career by doing their own thing and not chasing the short-term goal of a place on the playlist. They are an example to other musicians, McMorrow says.

“I was in Brooklyn, doing two nights, a week and a half ago. In the venue across the road from where we were, pretty much, Lankum were doing two nights and had [the Dublin folk artist] John Francis Flynn opening for them. Those are two artists that, if you were to look at their stats, you wouldn’t be, like, ‘These are world-beating musicians.’ You start aggregating to this stat-based norm and you miss bands like Lankum, bands like The Mary Wallopers, people like John Francis Flynn.”

McMorrow is looking forward to his forthcoming Irish tour, which he sees as another leg of his journey to be his best possible self.

“The last two, three years have been a process of building it back to a version of me that actually made me happy rather than making me cry at night-time – a version that was making music because I liked it. Within this industry there’s so much outside noise. It’s quite overwhelming. I was overwhelmed. It’s been nice to reset the clock.”

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in The Irish Times, by cartoonist Martyn Turner.

(Copyright of the artist is acknowledged)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nuala Holloway delves into the history of Ireland's Leaving Certificate, the final Secondary School/ High School exams which helps determine a place for students in Third Level education and explores its relevance in today's world.

0 notes

Text

Kindness of Strangers on Goodreads

When I read about a recent book scandal, I was reminded of the line, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” Blanche Debois says it in the Tennessee Williams play, Streetcar Named Desire. It’s a curious line because Blanche is not great at assessing strangers, and the only kindness she’s received was that in exchange for sex. Still, that line came to mind, when I thought of how…

View On WordPress

#A Cry From The Deep#Cait Corrain#Diana Stevan#Goodreads#Irish Times#kindness of strangers#Lilacs in the Dust Bowl#Paper Roses on Stony Mountain#Publishers Weekly#Tennesee Williams#The Miramichi Reader

0 notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes