#interstates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

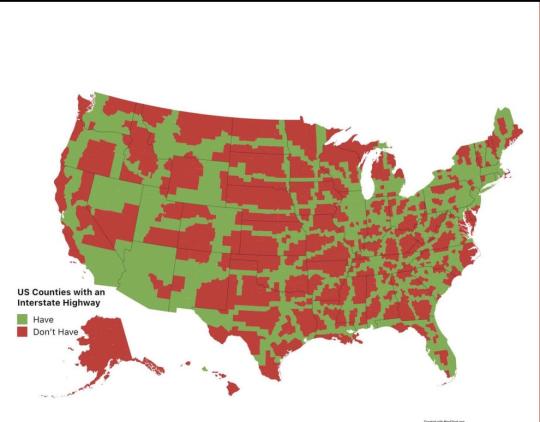

US counties with/without an interstate

859 notes

·

View notes

Text

interstate gothic

The car speedometer says you are going 80mph, but the dotted white lines at the edges of your lane are crawling by. The scenery around you is as distinguishable as if you were standing still. And the music on the radio is garbled, as if you were listening to it at half speed. The mountains in the distance have not gotten any closer.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

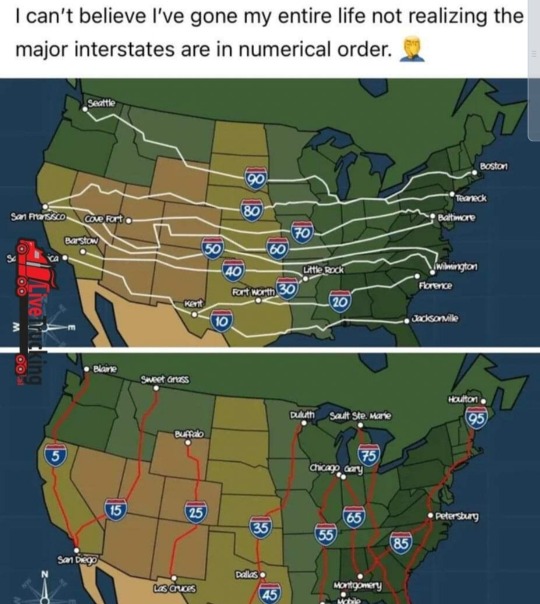

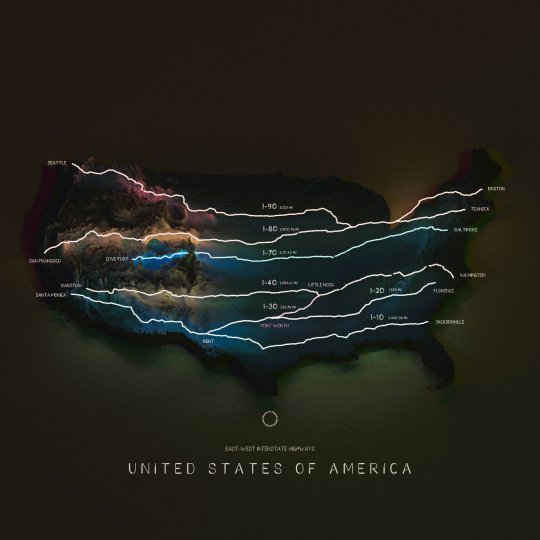

The interstates are in numerical order.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

🤯

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the interstate is a funeral procession

car after car after car

marching on forever

we all march towards death

i speed towards mine at 70 miles per hour

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the best example of being stuck in a bad traffic jam with the worst drivers outside of a metropolitan American city, it’s always an interstate with three numbers. I-295 Baltimore/Washington Parkway, I-495 DC beltway, I-695 Baltimore beltway. The gps can provide the travel time but it will always add an extra hour because traffic on any of these interstates is always unpredictable.

Writing fanfic as a non-US citizen like

64K notes

·

View notes

Text

Seamless transitions meet affordability! Our interstate removals redefine moving excellence, offering the best service at budget-friendly rates. Trust us for a stress-free relocation that ensures your belongings arrive safely. Elevate your move with our reliable and cost-effective solution. Your journey begins with us! 🚚🌐

#interstatesmovers#bestmovers#interstates#transport#interstatemovers#interstateremovalists#movingout#officemoving#home#realestate#moversandpackers#moverslife#transportationservices#movingcompany#bestmovingcompany#movingservices

0 notes

Text

Commercial Galaxies

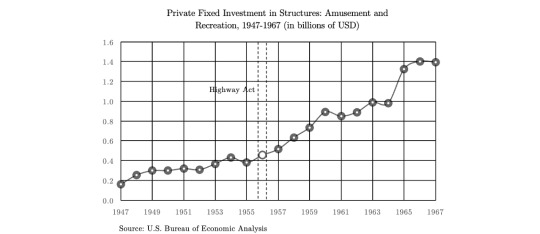

Not only were highways a simulacrum for America’s consumerism awash with billboard galore but they also emblematized an ambassador of tourism. Amongst tertiary industries the amusement park most notable for its flirtation with physics and lovable mascots featured prominently in family destinations after the 1956 Highway Act. Such escapism drew an influx of park goers so much that visits could be deemed a national pastime as crowds flocked to the cacophony of fun and laughter within the grounds. Out-of-state visitors in their enthusiasm for the roads began to perceive these excursions as seasonal if not weekend staples rather than exotic pilgrimages in virtue of how distance was trivialized. In an ex-post examination day trips were far more manageable whilst the industry’s exponential growth largely owed itself to the accessibility provided by the infrastructure. Attractions of great scale and scope were otherwise illogical if their topology was tantamount to a remote island that denied ingress like the protracted commutes from before. Any project of this species would be deemed as nothing short of a white elephant were it to anesthetize the frequency of attendees. On the other hand when freed from the preserve of locals the expansion of markets that actively sought consumers from faraway made such ventures viable.

Triumph over spatial barriers that once hobbled the industry when travel might have been too onerous did bring forth a tectonic shift even for the nation’s identity. These monuments to leisure were now just a hop, skip and a jump away as Walt Disney who founded the eponymous Disneyland a year shy of the Highway Act would find out. The location of this icon for the Western seaboard was not at all arbitrary since its perimeter sat on the footsteps of the Interstate within sight of a hundred yards. Market studies had shown that this spot situated a mere stone throw’s away from the Interstate 5 segment known as the Santa Ana Freeway would promise to capture the migratory patterns of vacationing families (Adams 1991: 109). The location invited parents with children in tow to the curated world and the genius was how proximity funnelled consumers straight into the park with convenience. The choice to be nestled next to the Interstate informed at least partially why Disneyland became the darling of American culture as attendance evolved into a rite of passage. The impetus of new infrastructure elevated the park to the status of national treasure because together they stood for the ‘soft power’ of postwar idealism against the grey utilitarianism of the Soviets. America’s identity in a bipolar world would thus be forged against the spectre of the Cold War.

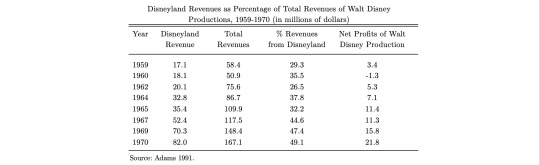

Disneyland’s market grew as a concomitant of the Interstate whereby 40 percent of attendance issued from out-of-state visitors in the first three years alone. This measure inexorably went up in the ratio vis-à-vis Californians who partook in the same entertainment hence vindicating just how much business was a function of highways. The efficacy of these roads to dispatch consumers towards this citadel of childhood dreams was instrumental in the company’s success (Marling 1991: 174). The scenic journey itself in the iconic station wagons of those days proved to be just as much a part of the charm. Walt Disney’s prescience in his calculated gambit therefore paid off handsomely. Bereft of this diversification in geography via thoroughfares a large share of the company’s foot traffic would have remained elusive to the detriment of profits. Speaking of which these said highways subtly filtered the most bourgeois of tourists who hailed from some of the highest quartiles of the income bracket. A 1958 survey revealed that in the profile of visitors 74 percent of families were owners of vehicles manufactured in 1955 or later as another 70 percent boasted proprietorship of a house (Findlay 1993: 90). Before long in its second year the park’s patronage of 4m visitors would eclipse the combined tourism of the Grand Canyon, Yosemite and Yellowstone (Goldberg 2016).

Admissions that grew by a factor of two in 1970 gave way to an ecosystem burgeoning around this commercial lodestar whose allure prompted an armada of companies to neighbour its terra firma. The seeds of infrastructure in the guise of highways reaped a concentration of business that was later a kinetic node for the hospitality and entertainment industries in Anaheim. From an orange grove to a thriving metropolis the city’s rapid evolution in its economic destiny resulted from the influx of consumers and the attendant intensity of commercial activity to service the former. A premium of revenue from the economies of agglomeration was to be had for companies which situated themselves within a five-mile radius that perpetuated even more appeal as a coveted utopia for leisure. Prior to the arrival of Disneyland the region was a sleepy outpost of fifteen thousand residents with less than thirty-four restaurants and eighty-seven motel rooms. By 1970 a gold rush had manifested with over four hundred restaurants and twelve-thousand rooms to accommodate the throngs of revellers (Findlay 1993). Anaheim’s fortunes in commercial real estate were intimately identified with Disney’s interests that spoke to the city ceding its autonomy in preference of the park’s hegemony. The juggernaut guaranteed a hotbed of industry in reciprocating the magnanimous gesture.

Less than a decade after the park’s founding the Major League baseball team known as the Los Angeles Angels were rehoused to within two miles inside of a $21m stadium. Yet again less than a year upon this fortuitous news did America’s leisure capital welcome a new $15m convention centre in its midst that would see a troika of industries amalgamating business with pleasure (Findlay 1993). The domino effect wrought by the Interstate changed the entire parameters of development in Anaheim. Between the satellites of Disney, a sports franchise and a rental hall which in concert formed America’s quintessential tourist destination the city shed its prosaic roots in its maturity towards a cosmopolitan hub. Disneyland itself became a flagship for its parent company whose operations generated half of total revenue by 1970. So successful was the Highway Act at precipitating the economic infusion into the tertiary sector that in 1971 the humid marshlands of Florida would also see the fanfare of a hard opening for a Disney World adjacent to Orlando’s I-4. The canon for immunizing operations against any logistical shortcomings was replicated on the other side of the country only this time the business catered to consumers on the Eastern seaboard. The gravitational pull of the Interstate was too great to be unheeded by serious entrepreneurs.

In the prelude of transplanting Mickey Mouse into Central Florida the city of Orlando was a sedate community that bordered the state’s artery of I-4 which had been completed in 1965. In prospecting for a second home Walt Disney finally set upon a landmass twice the size of Manhattan not too far away from America’s gateway into space known as Cape Canaveral (Bright 1987). A land acquisition of twenty-seven thousand acres was subsumed under the company’s property assets to commence development on Disney’s most grandiose project hitherto (Holy and Who 2018). The unique selling proposition for the site was the junction of the I-4 and I-95 that Walt Disney had surveyed by plane in 1963 which was the provenance for the epiphany of his new Eldorado. With the banner years of success on the West coast the brain trust had reached the consensus that the new market was already primed for Disney’s legacy project. The committee on the development’s feasibility concluded that 95 percent of visitors would arrive by the I-4 which abrogated any need for investment in infrastructure (Goldberg 2021). Upon construction a cottage-industry of eateries and lodgings proliferated as a denouement of Disney’s halo effect. Orlando subsequently would grow faster than any other city at an average annual rate of 8.2 percent (Callaghan 1990).

These lofty statistics are a commentary on why the region’s geographical endowments wooed the company as a tantalizing prospect over the thirteen other venues considered. Florida was an irresistible suitor with its sun-kissed landscape amiable to year-round operations and the factoid that three-fourths of the American population resided on the Eastern seaboard. The profitability of Disney’s dreamscape was therefore more or less assured within the Sunbelt. In preceding years a paltry 3.5m tourists would vacation annually in Central Florida but upon the park’s inaugural year that number soared to 10m. Foreseeing such value creation from afar in 1967 the Florida legislature conceded full autonomy to Disney World which bore similarities to the Vatican as it was the beneficiary of a derogation from state rules. The universe that would be created in Florida’s hinterland would then be prosecuted over forty-seven transactions to secure twenty-seven thousand acres at a cost of $5m or $48m when adjusted for inflation. This bargain-basement price in the real estate market materialized by the subterfuge of shell companies procuring properties in secret lest prices inflate due to land speculation upon news of Disney’s interests. By sidestepping the mistakes in Anaheim the average price per acre came to be $180 (Foglesong 2003).

The 1970s emblematized the honeymoon of Disney’s incursion into Orlando that transcended the previous years of inertia as a phalanx of tourists descended upon Florida. The marquee asset which was ten times larger than its sister park in California generated much curiosity and such interest was well deserved since $400m was ploughed into the project. A budget of this proportion which would approximate north of $3b in today’s currency set a watermark so high that other attractions were simply mediocre by comparison. The barometer of success from such a financial commitment was measured by attendance and the park did not disappoint. Patronage reached over 50m after a mere five years of operation (Kurtti 1996). The park’s ethos of nostalgia wedded to futurism sold a cornucopia of tickets despite the period’s stagflation which was a testament to Disney’s recession-proof business model. The degree to which the company diversified earnings was the sine quo non of its hegemony over competitors whose revenue streams were more linear between their ticketing and in-park sales. In contrast Disney captured guests within its ecosystem of intellectual property that monetized a mosaic of memories from media to merchandise. Ergo the branding wizardry quickly transformed Central Florida into a magnet for tourism.

The Highway Act of 1956 so became a seminal piece of statecraft that provided for America’s ascendency. Dynamic changes borne from the legislation altered industries in indelible ways and rightly so as the fiscal stimulus exceeded even Europe’s Marshall Plan. That was not a misreading nor misprint since postwar reconstruction for the most battered precincts were dwarfed by appropriations made under the Interstate System. Perhaps the former may approximate industrial policy as exporters matched European demand after it was laid to waste by war but the infrastructure marathon had greater spillovers pregnant with downstream effect. Whereas a plethora of goods made their way across the Atlantic from factories unscathed by conflict the expressways at home fundamentally restructured the American economy. The executive decision to import Germany’s prodigy of the Autobahn would affect a kaleidoscope of industries and herald the genesis of consumerism. New roads and bridges realigned overland supply-chains insofar as nothing would escape the productivity reforms of this substantial investment from manufacturers to real estate markets. The breakneck advancement in less than a decade post-Act came to fruition on the heels of modernizing mobility.

Often lawmakers exercise a great deal of discretion when electing to subsidize policy objectives lest it crowd-out private investment and redound to deadweight loss due to market distortions. However in the case of highway politics the value created was overwhelmingly positive in terms of logistics and development. Between assembly lines in Detroit galloping away and the wholesale creation of a domestic tourism industry the Interstate System ushered an era of postwar affluence into the American consciousness. Mid-century exceptionalism was again on display since its wartime heroics of recent past with the country now embarking upon the largest public works project in history. The industrial machine was stirred from its dormant state after a supply glut from the war had arrested production in a peacetime economy. Industries therefore set upon a warpath only with the proviso that this time they would be retooled and poised to indulge the essential and non-essential needs of consumers. Those local roads and railways which once bore the brunt of transporting goods would be substituted for the alacrity of superhighways. Free enterprise was then reinvigorated as the production-possibility frontier was pushed beyond the status quo whereby the boost in the cadence of industry would telegraph America’s modernization.

0 notes

Text

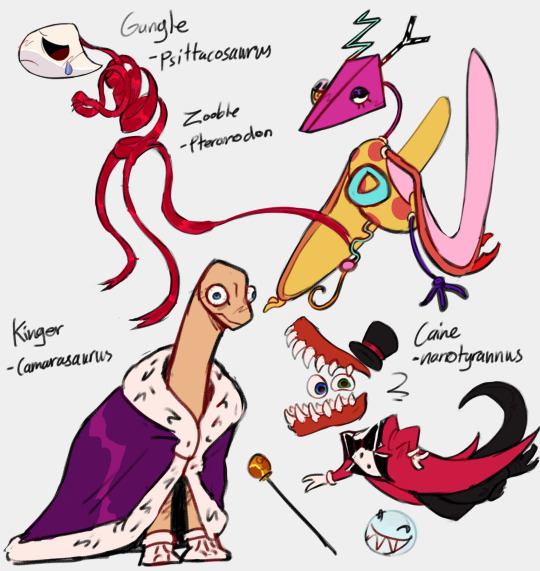

Tadc..... dinosaurs.... tadc dinosaurs

#returning to my roots with this one#proud of the fact that i was able to draw anthro dinos w out fucking it up somehow#finallyyyy#my art#pomnis a dryo cuz theyre smaller and have round features w out being too weak hahhha#jax is a galli cuz theyre tall and are extremely annoying in this one game i play just like him<3 /pos#rags a mai cuz theyre so motherly#i mean the name literally means “good mother lizard”#gangles a psitt cuz they have an intersting face shape for a mask and are small#zoobles a pteranodon cuz they dont fit in not being dinos and everything#like how zooble doesnt fit in much cuz theyre a pile of parts rlly#kingers a camara cuz tall and silly looking /pos#caines a nanotyrannus cuz i wanted him to be a rex of sorts but not biiig#tadc#tadc art#dinosaurs#tadc dinos#the amazing digital circus#tadc fanart#tadc pomni#tadc jax#tadc ragatha#tadc zooble#tadc gangle#tadc kinger#tadc caine

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

I Barely Survived on the Road to My Florida Vacation!

0 notes

Photo

East-west interstate (I) highways ending in zero.

by researchremora

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let us take the hassle out of your long-distance move! Call us today and discover how our interstate moving service in Melbourne can make your move a breeze.

#interstatesmovers#bestmovers#interstates#transport#goodservice#service#movingout#officemoving#home#realestate#moversandpackers#moverslife#transportationservices#movingcompany#movingservices#professionalmovers#movingandstorage#melbourne#relocation

0 notes

Text

space sweepers but they're delivery people and are at no point on screen through the entire movie

#fantasy high#riz gukgak#kristen applebees#gorgug thistlespring#adaine abernant#fabian seacaster#figueroth faeth#the bad kids#half tempted to say these names are forum handles they use so much it pretty much became their professional names lol#I keep them teenagers bc its funnier that way#no real lore I just like drawing this. but I do think abt how theyre all weirdos too also bc thats funny to me#riz is a huge conspiracyhead who does everything by hands. he has a casio fx-570 in mint condition. nobody knows how he's maintaining it#he is nonetheless Really Good at his job. which somewhat tracks bc it's a job that requires keeping up with interstation conflicts#and new policies and an obsessive amount of planning. but he is Too Good at it. and also he dresses like that#kristen has the atomic engine that theoretically lets her unmake and remake matters with her mind. but it consumes a huge amount#of energy so it's mostly useless. she's still a cult survivor also#gorgug lives his entire life on a ship with his parents who quit a cushy deal maintaining a space station bc he wouldn't be allowed on#the low gravity let him grow very tall but also his oxygen saturation is pretty bad so he's got breathing support#fig is a robot who just found out she's a robot like two months ago. she's been assuming everyone's a robot like her and she's been feeling#very betrayed by her mom lying about that part. she's on a body mod spree which is rough bc system-specific parts are expensive#and so is adapting random parts to her system#fabian's still a pirate captain's son. can't say anything that'd be able to get the vibes across clearer than that#adaine went to tech/business school. she put her monthly allowance towards an ecoterrorist group in her academy which turned out to be an o#and she's currently wanted by UTS. more than fabian. which makes him slightly mad#she's also acquired a passion for low-tech weaponry on the way. she likes ice picks and cleavers#I think up all of this for no reason except that once again the idea of all these people being 1/teens and 2/on the same ship to be posties#is hilarious to me. esp. if they were in a forum group chat beforehand

554 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If I want to speak a bit more and have fun, would be Carlos or Pierre but Carlos or Pierre would be a mess like after a day I will just want to sleep and with them it would be very difficult because they are messy."

#what do you mean charles please elaborate#he tried to elaborate but he couldn't really#honestly how can this Not be about sex#also a whole day and then he wants to sleep hmm intersting#charles leclerc#f1#carlos sainz#pierre gasly#beyond the grid#formula 1#mypost

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surveillance pricing

THIS WEEKEND (June 7–9), I'm in AMHERST, NEW YORK to keynote the 25th Annual Media Ecology Association Convention and accept the Neil Postman Award for Career Achievement in Public Intellectual Activity.

Correction, 7 June 2024: The initial version of this article erroneously described Jeffrey Roper as the founder of ATPCO. He benefited from ATPCO, but did not co-found it. The initial version of this article called ATPCO "an illegal airline price-fixing service"; while ATPCO provides information that the airlines use to set prices, it does not set prices itself, and while the DOJ investigated the company, they did not pursue a judgment declaring the service to be illegal. I regret the error.

Noted anti-capitalist agitator Adam Smith had it right: "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

Despite being a raving commie loon, Smith's observation was so undeniably true that regulators, policymakers, and economists couldn't help but acknowledge that it was true. The trustbusting era was defined by this idea: if we let the number of companies in a sector get too small, or if we let one or a few companies get too big, they'll eventually start to rig prices.

What's more, once an industry contracts corporate gigantism, it will become too big to jail, able to outspend and overpower the regulators charged with reining in its cheating. Anyone who believes Smith's self-evident maxim had to accept its conclusion: that companies had to be kept smaller than the state that regulated them. This wasn't about "punishing bigness" – it was the necessary precondition for a functioning market economy.

We kept companies small for the same reason that we limited the height of skyscrapers: not because we opposed height, or failed to appreciate the value of a really good penthouse view – rather, to keep the building from falling over and wrecking all the adjacent buildings and the lives of the people inside them.

Starting in the neoliberal era – Carter, then Reagan – we changed our tune. We liked big business. A business that got big was doing something right. It was perverse to shut down our best companies. Instead, we'd simply ban big companies from rigging prices. This was called the "consumer welfare" theory of antitrust. It was a total failure.

40 years later, nearly every industry is dominated by a handful of companies, and these companies price-gouge us with abandon. Worse, they use their gigantic ripoff winnings to fill war-chests that fund the corruption of democracy, capturing regulators so that they can rip us off even more, while ignoring labor, privacy and environmental law and ducking taxes.

It turns out that keeping gigantic, opaque, complex corporations honest is really hard. They have so many ways to shuffle money around that it's nearly impossible to figure out what they're doing. Digitalization makes things a million times worse, because computers allow businesses to alter their processes so they operate differently for every customer, and even for every interaction.

This is Dieselgate times a billion: VW rigged its cars to detect when they were undergoing emissions testing and switch to a less polluting, more compliant mode. But when they were on the open road, they spewed lethal quantities of toxic gas, killing people by the thousands. Computers don't make corporate leaders more evil, but they let evil corporate leaders execute far more complex and nefarious plans. Digitalization is a corporate moral hazard, making it just too easy and tempting to rig the game.

That's why Toyota, the largest car-maker in the world, just did Dieselgate again, more than a decade later. Digitalization is a temptation no giant company can resist:

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1wwj1p2wdyo

For forty years, pro-monopoly cheerleaders insisted that we could allow companies to grow to unimaginable scale and still prevent cheating. They passed rules banning companies from explicitly forming agreements to rig prices. About ten seconds later, new middlemen popped up offering "information brokerages" that helped companies rig prices without talking to one another.

Take Agri Stats: the country's hyperconcentrated meatpacking industry pays Agri Stats to "consult on prices." They provide Agri Stats with a list of their prices, and then Agri Stats suggests changes based on its analysis. What does that analysis consist of? Comparing the company's prices to its competitors, who are also Agri Stats customers:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/04/dont-let-your-meat-loaf/#meaty-beaty-big-and-bouncy

In other words, Agri Stats finds the highest price for each product in the sector, then "advises" all the companies with lower prices to raise their prices to the "competitive" level, creating a one-way ratchet that sends the price of food higher and higher.

More and more sectors have an Agri Stats, and digitalization has made this price-gouging system faster, more efficient, and accessible to sectors with less concentration. Landlords, for example, have tapped into Realpage, a "data broker" that the same thing to your rent that Agri Stats does to meat prices. Realpage requires the landlords who sign up for its service to accept its "recommendations" on minimum rents, ensuring that prices only go up:

https://popular.info/p/feds-raid-corporate-landlord-escalating

Writing for The American Prospect, Luke Goldstein lays out the many ways in which these digital intermediaries have supercharged the business of price-rigging:

https://prospect.org/economy/2024-06-05-three-algorithms-in-a-room/

Goldstein identifies a kind of patient zero for this ripoff epidemic: Jeffrey Roper, a former Alaska Air exec who benefited from a service that helps airlines set prices. ATPCO was investigated by the DOJ in the 1990s, but the enforcers lost their nerve and settled with the company, which agreed to apply some ornamental fig-leafs to its collusion-machine. Even those cosmetic changes were seemingly a bridge too far Roper, who left the US.

But he came back to serve as Realpage's "principal scientist" – the architect of a nationwide scheme to make rental housing vastly more expensive. For Roper, the barrier to low rents was empathy: landlords felt stirrings of shame when they made shelter unaffordable to working people. Roper called these people "idiots" who sentimentality "costs the whole system."

Sticking a rent-gouging computer between landlords and the people whose lives they ruin is a classic "accountability sink," as described in Dan Davies' new book "The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions – and How The World Lost its Mind":

https://profilebooks.com/work/the-unaccountability-machine/

It's a form of "empiricism washing": if computers are working in the abstract realm of pure numbers, they're just moving the objective facts of the quantitative realm into the squishy, imperfect qualitative world. Davies' interview on Trashfuture is excellent:

https://trashfuturepodcast.podbean.com/e/fire-sale-at-the-accountability-store-feat-dan-davies/

To rig prices, an industry has to solve three problems: the problem of coming to an agreement to fix prices (economists call this "the collective action problem"); the problem of coming up with a price; and the problem of actually changing prices from moment to moment. This is the ripoff triangle, and like a triangle, it has many stable configurations.

The more concentrated an industry is, the easier it is to decide to rig prices. But if the industry has the benefit of digitalization, it can swap the flexibility and speed of computers for the low collective action costs from concentration. For example, grocers that switch to e-ink shelf tags can make instantaneous price-changes, meaning that every price change is less consequential – if sales fall off after a price-hike, the company can lower them again at the press of a button. That means they can collude less explicitly but still raise prices:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/26/glitchbread/#electronic-shelf-tags

My name for this digital flexibility is "twiddling." Businesses with digital back-ends can alter their "business logic" from second to second, and present different prices, payouts, rankings and other key parts of the deal to every supplier or customer they interact with:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/19/twiddler/

Not only does twiddling make it easier to rip off suppliers, workers and customers, it also makes these crimes harder to detect. Twiddling made Dieselgate possible, and it also underpinned "Greyball," Uber's secret strategy of refusing to send cars to pick up transportation regulators who would then be able to see firsthand how many laws the company was violating:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/03/technology/uber-greyball-program-evade-authorities.html

Twiddling is so easy that it has brought price-fixing to smaller companies and less concentrated sectors, though the biggest companies still commit crimes on a scale that put these bit-players to shame. In The Prospect, David Dayen investigates the "personalized pricing" ripoff that has turned every transaction into a potential crime-scene:

https://prospect.org/economy/2024-06-04-one-person-one-price/

"Personalized pricing" is the idea that everything you buy should be priced based on analysis of commercial surveillance data that predicts the maximum amount you are willing to pay.

Proponents of this idea – like Harvard's Pricing Lab with its "Billion Prices Project" – insist that this isn't a way to rip you off. Instead, it lets companies lower prices for people who have less ability to pay:

https://thebillionpricesproject.com/

This kind of weaponized credulity is totally on-brand for the pro-monopoly revolution. It's the same wishful thinking that led regulators to encourage monopolies while insisting that it would be possible to prevent "bad" monopolies from raising prices. And, as with monopolies, "personalized pricing" leads to an overall increase in prices. In econspeak, it is a "transfer of wealth from consumer to the seller."

"Personalized pricing" is one of those cuddly euphemisms that should make the hair on the back of your neck stand up. A more apt name for this practice is surveillance pricing, because the "personalization" depends on the vast underground empire of nonconsensual data-harvesting, a gnarly hairball of ad-tech companies, data-brokers, and digital devices with built-in surveillance, from smart speakers to cars:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/12/market-failure/#car-wars

Much of this surveillance would be impractical, because no one wants their car, printer, speaker, watch, phone, or insulin-pump to spy on them. The flexibility of digital computers means that users always have the technical ability to change how these gadgets work, so they no longer spy on their users. But an explosion of IP law has made this kind of modification illegal:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

This is why apps are ground zero for surveillance pricing. The web is an open platform, and web-browsers are legal to modify. The majority of web users have installed ad-blockers that interfere with the surveillance that makes surveillance pricing possible:

https://doc.searls.com/2023/11/11/how-is-the-worlds-biggest-boycott-doing/

But apps are a closed platform, and reverse-engineering and modifying an app is a literal felony – several felonies, in fact. An app is just a web-page skinned with enough IP to make it a felony to modify it to protect your consumer, privacy or labor rights:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/07/treacherous-computing/#rewilding-the-internet

(Google is leading a charge to turn the web into the kind of enshittifier's paradise that apps represent, blocking the use of privacy plugins and proposing changes to browser architecture that would allow them to felonize modifying a browser without permission:)

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/02/self-incrimination/#wei-bai-bai

Apps are a twiddler's playground. Not only can they "customize" every interaction you have with them, but they can block you (or researchers seeking to help you) from recording and analyzing the app's activities. Worse: digital transactions are intimate, contained to the palm of your hand. The grocer whose e-ink shelf-tags flicker and reprice their offerings every few seconds can be collectively observed by people who are in the same place and can start a conversation about, say, whether to come back that night a throw a brick through the store's window to express their displeasure. A digital transaction is a lonely thing, atomized and intrinsically shielded from a public response.

That shielding is hugely important. The public hates surveillance pricing. Time and again, through all of American history, there have been massive and consequential revolts against the idea that every price should be different for every buyer. The Interstate Commerce Commission was founded after Grangers rose up against the rail companies' use of "personalized pricing" to gouge farmers.

Companies know this, which is why surveillance pricing happens in secret. Over and over, every day, you are being gouged through surveillance pricing. The sellers you interact with won't tell you about it, so to root out this practice, we have to look at the B2B sales-pitches from the companies that sell twiddling tools.

One of these companies is Plexure, partly owned by McDonald's, which provides the surveillance-pricing back-ends for McD's, Ikea, 7-Eleven, White Castle and others – basically, any time a company gives you a hard-sell to order via its apps rather than its storefronts or its website, you should assume you're getting twiddled, hard.

These companies use the enshittification playbook to trap you into using their apps. First, they offer discounts to customers who order through their apps – then, once the customers are fully committed to shopping via app, they introduce surveillance pricing and start to jack up the prices.

For example, Plexure boasts that it can predict what day a given customer is getting paid on and use that information to raise prices on all the goods the customer shops for on that day, on the assumption that you're willing to pay more when you've got a healthy bank balance.

The surveillance pricing industry represents another reason for everything you use to spy on you – any data your "smart" TV or Nest thermostat or Ring doorbell can steal from you can be readily monetized – just sell it to a surveillance pricing company, which will use it to figure out how to charge you more for everything you buy, from rent to Happy Meals.

But the vast market for surveillance data is also a potential weakness for the industry. Put frankly: the commercial surveillance industry has a lot of enemies. The only thing it has going for it is that so many of these enemies don't know that what's they're really upset about is surveillance.

Some people are upset because they think Facebook made Grampy into a Qanon. Others, because they think Insta gave their kid anorexia. Some think Tiktok is brainwashing millennials into quoting Osama bin Laden. Some are upset because the cops use Google location data to round up Black Lives Matter protesters, or Jan 6 insurrectionists. Some are angry about deepfake porn. Some are angry because Black people are targeted with ads for overpriced loans or colleges:

https://www.theregister.com/2024/06/04/meta_ad_algorithm_discrimination/

And some people are angry because surveillance feeds surveillance pricing. The thing is, whatever else all these people are angry about, they're all angry about surveillance. Are you angry that ad-tech is stealing a 51% share of news revenue? You're actually angry about surveillance. Are you angry that "AI" is being used to automatically reject resumes on racial, age or gender grounds? You're actually angry about surveillance.

There's a very useful analogy here to the history of the ecology movement. As James Boyle has long said, before the term "ecology" came along, there were people who cared about a lot of issues that seemed unconnected. You care about owls, I care about the ozone layer. What's the connection between charismatic nocturnal avians and the gaseous composition of the upper atmosphere? The term ecology took a thousand issues and welded them together into one movement.

That's what's on the horizon for privacy. The US hasn't had a new federal consumer privacy law since 1988, when Congress acted to ban video-store clerks from telling the newspapers what VHS cassettes you were renting:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Video_Privacy_Protection_Act

We are desperately overdue for a new consumer privacy law, but every time this comes up, the pro-surveillance coalition defeats the effort. but as people who care about conspiratorialism, kids' mental health, spying by foreign adversaries, phishing and fraud, and surveillance pricing all come together, they will be an unbeatable coalition:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/12/06/privacy-first/#but-not-just-privacy

Meanwhile, the US government is actually starting to take on these ripoff artists. The FTC is working to shut down data-brokers:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/16/the-second-best-time-is-now/#the-point-of-a-system-is-what-it-does

The FBI is raiding landlords to build a case against Frontpage and other rent price-fixers:

https://popular.info/p/feds-raid-corporate-landlord-escalating

Agri Stats is facing a DoJ lawsuit:

https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/market-news/agri-stats-loses-motions-to-transfer-dismiss-in-doj-antitrust-case

Not every federal agency has gotten the message, though. Trump's Fed Chairman, Jerome Powell – whom Biden kept on the job – has been hiking interest rates in a bid to reduce our purchasing power by making millions of Americans poorer and/or unemployed. He's doing this to fight inflation, on the theory that inflation is being cause by us being too well-off, and therefore trying to buy more goods than are for sale.

But of course, interest rates are inflationary: when interest rates go up, it gets more expensive to pay your credit card bills, lease your car, and pay a mortgage. And where we see the price of goods shooting up, there's abundant evidence that this is the result of greedflation – companies jacking up their prices and blaming inflation. Interest rate hawks say that greedflation is impossible: if one company raises its prices, its competitors will swoop in and steal their customers with lower prices.

Maybe they would do that – if they didn't have a toolbox full of algorithmic twiddling options and a deep trove of surveillance data that let them all raise prices together:

https://prospect.org/blogs-and-newsletters/tap/2024-06-05-time-for-fed-to-meet-ftc/

Someone needs to read some Adam Smith to Chairman Powell: "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/05/your-price-named/#privacy-first-again

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#david dayen#the american prospect#surveillance advertising#commercial surveillance#predictive pricing#monopolism#monopolies#antitrust#unfair and deceptive method of competition#ftc act Section 5#ftca5#ripoffs#surveillance#twiddling#ip#apps#apps are shit#ziprecruiter#personalized pricing#price gouging#just and reasonable#interstate commerce act#one person one price#surveillance pricing#privacy first#billion prices project#ecommerce#ninetailed#cortado group

423 notes

·

View notes