#internal locus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

By: Jon Haidt

Published: Mar 9, 2023

In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), and he has worked tirelessly since 2001 to defend the free speech rights of college students. That almost always meant pushing back against administrators who didn’t want students to cause trouble, and who justified their suppression of speech with appeals to the emotional “safety” of students—appeals that the students themselves didn’t buy. But in late 2013, Greg began to encounter new cases in which students were pushing to ban speakers, punish people for ordinary speech, or implement policies that would chill free speech. These students arrived on campus in the fall of 2013 already accepting the idea that books, words, and ideas could hurt them. Why did so many students in 2013 believe this, when there was little sign of such beliefs in 2011?

Greg is prone to depression, and after hospitalization for a serious episode in 2007, Greg learned CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy). In CBT you learn to recognize when your ruminations and automatic thinking patterns exemplify one or more of about a dozen “cognitive distortions,” such as catastrophizing, black-and-white thinking, fortune telling, or emotional reasoning. Thinking in these ways causes depression, as well as being a symptom of depression. Breaking out of these painful distortions is a cure for depression.

What Greg saw in 2013 were students justifying the suppression of speech and the punishment of dissent using the exact distortions that Greg had learned to free himself from. Students were saying that an unorthodox speaker on campus would cause severe harm to vulnerable students (catastrophizing); they were using their emotions as proof that a text should be removed from a syllabus (emotional reasoning). Greg hypothesized that if colleges supported the use of these cognitive distortions, rather than teaching students skills of critical thinking (which is basically what CBT is), then this could cause students to become depressed. Greg feared that colleges were performing reverse CBT.

I thought the idea was brilliant because I had just begun to see these new ways of thinking among some students at NYU. I volunteered to help Greg write it up, and in August 2015 our essay appeared in The Atlantic with the title: The Coddling of the American Mind. Greg did not like that title; his original suggestion was “Arguing Towards Misery: How Campuses Teach Cognitive Distortions.” He wanted to put the reverse CBT hypothesis in the title.

After our essay came out, things on campus got much worse. The fall of 2015 marked the beginning of a period of protests and high-profile conflicts on campus that led many or most universities to implement policies that embedded this new way of thinking into campus culture with administrative expansions such as “bias response teams” to investigate reports of “microaggressions.” Surveys began to show that most students and professors felt that they had to self-censor. The phrase “walking on eggshells” became common. Trust in higher ed plummeted, along with the joy of intellectual discovery and sense of goodwill that had marked university life throughout my career.

Greg and I decided to expand our original essay into a book in which we delved into the many causes of the sudden change in campus culture. Our book focused on three “great untruths” that seemed to be widely believed by the students who were trying to shut down speech and prosecute dissent:

1. What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker 2. Always trust your feelings 3. Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

Each of these untruths was the exact opposite of a chapter in my first book, The Happiness Hypothesis, which explored ten Great Truths passed down to us from ancient societies east and west. We published our book in 2018 with the title, once again, of The Coddling of the American Mind. Once again, Greg did not like the title. He wanted the book to be called “Disempowered,” to capture the way that students who embrace the three great untruths lose their sense of agency. He wanted to capture reverse CBT.

The Discovery of the Gender-by-Politics Interaction

In September 2020, Zach Goldberg, who was then a graduate student at Georgia State University, discovered something interesting in a dataset made public by Pew Research. Pew surveyed about 12,000 people in March 2020, during the first month of the Covid shutdowns. The survey included this item: “Has a doctor or other healthcare provider EVER told you that you have a mental health condition?” Goldberg graphed the percentage of respondents who said “yes” to that item as a function of their self-placement on the liberal-conservative 5-point scale and found that white liberals were much more likely to say yes than white moderates and conservatives. (His analyses for non-white groups generally found small or inconsistent relationships with politics.)

I wrote to Goldberg and asked him to redo it for men and women separately, and for young vs. old separately. He did, and he found that the relationship to politics was much stronger for young (white) women. You can see Goldberg’s graph here, but I find it hard to interpret a three-way interaction using bar charts, so I downloaded the Pew dataset and created line graphs, which make it easier to interpret.

Here’s the same data, showing three main effects: gender (women higher), age (youngest groups higher), and politics (liberals higher). The graphs also show three two-way interactions (young women higher, liberal women higher, young liberals higher). And there’s an important three-way interaction: it is the young liberal women who are highest. They are so high that a majority of them said yes, they had been told that they have a mental health condition.

Figure 1. Data from Pew Research, American Trends Panel Wave 64. The survey was fielded March 19-24, 2020. Graphed by Jon Haidt.

In recent weeks—since the publication of the CDC’s report on the high and rising rates of depression and anxiety among teens—there has been a lot of attention to a different study that shows the gender-by-politics interaction: Gimbrone, Bates, Prins, & Keyes (2022), titled: “The politics of depression: Diverging trends in internalizing symptoms among US adolescents by political beliefs.” Gimbrone et al. examined trends in the Monitoring the Future dataset, which is the only major US survey of adolescents that asks high school students (seniors) to self-identify as liberal or conservative (using a 5-point scale). The survey asks four items about mood/depression. Gimbrone et al. found that prior to 2012 there were no sex differences and only a small difference between liberals and conservatives. But beginning in 2012, the liberal girls began to rise, and they rose the most. The other three groups followed suit, although none rose as much, in absolute terms, as did the liberal girls (who rose .73 points since 2010, on a 5-point scale where the standard deviation is .89).

Figure 2. Data from Monitoring the Future, graphed by Gimbrone et al. (2022). The scale runs from 1 (minimum) to 5 (maximum).

The authors of the study try to explain the fact that liberals rise first and most in terms of the terrible things that conservatives were doing during Obama’s second term, e.g.,

Liberal adolescents may have therefore experienced alienation within a growing conservative political climate such that their mental health suffered in comparison to that of their conservative peers whose hegemonic views were flourishing.

The progressive New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg took up the question and wrote a superb essay making the argument that teen mental health is not and must not become a partisan issue. She dismissed Gimbrone et al.’s explanation as having a poor fit with their own data:

Barack Obama was re-elected in 2012. In 2013, the Supreme Court extended gay marriage rights. It was hard to draw a direct link between that period’s political events and teenage depression, which in 2012 started an increase that has continued, unabated, until today.

After examining the evidence, including the fact that the same trends happened at the same time in Britain, Canada, and Australia, Goldberg concluded that “Technology, not politics, was what changed in all these countries around 2012. That was the year that Facebook bought Instagram and the word “selfie” entered the popular lexicon.”

Journalist Matt Yglesias also took up the puzzle of why liberal girls became more depressed than others, and in a long and self-reflective Substack post, he described what he has learned about depression from his own struggles involving many kinds of treatment. Like Michelle Goldberg, he briefly considered the hypothesis that liberals are depressed because they’re the only ones who see that “we’re living in a late-stage capitalist hellscape during an ongoing deadly pandemic w record wealth inequality, 0 social safety net/job security, as climate change cooks the world,” to quote a tweet from the Washington Post tech columnist Taylor Lorenz. Yglesias agreed with Goldberg and other writers that the Lorenz explanation—reality makes Gen Z depressed—doesn’t fit the data, and, because of his knowledge of depression, he focused on the reverse path: depression makes reality look terrible. As he put it: “Mentally processing ambiguous events with a negative spin is just what depression is.”

Yglesias tells us what he has learned from years of therapy, which clearly involved CBT:

It’s important to reframe your emotional response as something that’s under your control: • Stop saying “so-and-so made me angry by doing X.” • Instead say “so-and-so did X, and I reacted by becoming angry.” And the question you then ask yourself is whether becoming angry made things better? Did it solve the problem?

Yglesias wrote that “part of helping people get out of their trap is teaching them not to catastrophize.” He then described an essay by progressive journalist Jill Filipovic that argued, in Yglesias’s words, that “progressive institutional leaders have specifically taught young progressives that catastrophizing is a good way to get what they want.”

Yglesias quoted a passage from Filipovic that expressed exactly the concern that Greg had expressed to me back in 2014:

I am increasingly convinced that there are tremendously negative long-term consequences, especially to young people, coming from this reliance on the language of harm and accusations that things one finds offensive are “deeply problematic” or even violent. Just about everything researchers understand about resilience and mental well-being suggests that people who feel like they are the chief architects of their own life — to mix metaphors, that they captain their own ship, not that they are simply being tossed around by an uncontrollable ocean — are vastly better off than people whose default position is victimization, hurt, and a sense that life simply happens to them and they have no control over their response.

I have italicized Filipovic’s text about the benefits of feeling like you captain your own ship because it points to a psychological construct with a long history of research and measurement: Locus of control. As first laid out by Julian Rotter in the 1950s, this is a malleable personality trait referring to the fact that some people have an internal locus of control—they feel as if they have the power to choose a course of action and make it happen, while other people have an external locus of control—they have little sense of agency and they believe that strong forces or agents outside of themselves will determine what happens to them. Sixty years of research show that people with an internal locus of control are happier and achieve more. People with an external locus of control are more passive and more likely to become depressed.

How a Phone-Based Childhood Breeds Passivity

There are at least two ways to explain why liberal girls became depressed faster than other groups at the exact time (around 2012) when teens traded in their flip phones for smartphones and the girls joined Instagram en masse. The first and simplest explanation is that liberal girls simply used social media more than any other group. Jean Twenge’s forthcoming book, Generations, is full of amazing graphs and insightful explanations of generational differences. In her chapter on Gen Z, she shows that liberal teen girls are by far the most likely to report that they spend five or more hours a day on social media (31% in recent years, compared to 22% for conservative girls, 18% for liberal boys, and just 13% for conservative boys). Being an ultra-heavy user means that you have less time available for everything else, including time “in real life” with your friends. Twenge shows in another graph that from the 1970s through the early 2000s, liberal girls spent more time with friends than conservative girls. But after 2010 their time with friends drops so fast that by 2016 they are spending less time with friends than are conservative girls. So part of the story may be that social media took over the lives of liberal girls more than any other group, and it is now clear that heavy use of social media damages mental health, especially during early puberty.

But I think there’s more going on here than the quantity of time on social media. Like Filipovic, Yglesias, Goldberg, and Lukianoff, I think there’s something about the messages liberal girls consume that is more damaging to mental health than those consumed by other groups.

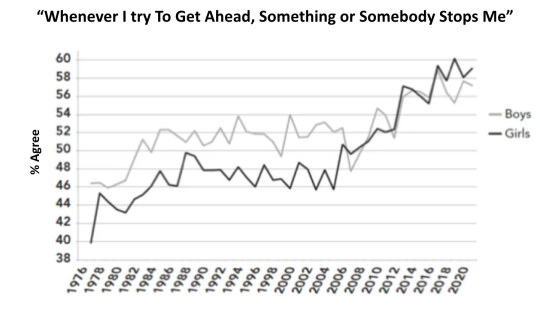

The Monitoring the Future dataset happens to have within it an 8-item Locus of Control scale. With Twenge’s permission, I reprint one such graph from Generations showing responses to one of the items: “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” This item is a good proxy for Filipovic’s hypothesis about the disempowering effects of progressive institutions. If you agree with that item, you have a more external locus of control. As you can see in Figure 3, from the 1970s until the mid-2000s, boys were a bit more likely to agree with that item, but then girls rose to match boys, and then both sexes rose continuously throughout the 2010s—the era when teen social life became far more heavily phone-based.

Figure 3. Percentage of boys and girls (high school seniors) who agree with (or are neutral about) the statement “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” From Monitoring the Future, graphed by Jean Twenge in her forthcoming book Generations.

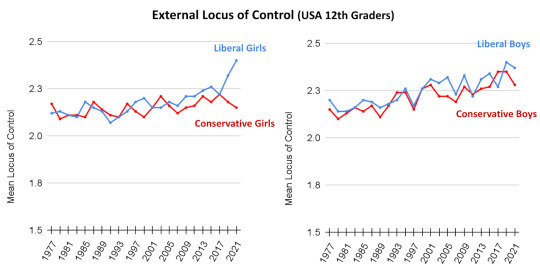

When the discussion of the gender-by-politics interaction broke out a few weeks ago, I thought back to Twenge’s graph and wondered what would happen if we broke up the sexes by politics. Would it give us the pattern in the Gimbrone et al. graphs, where the liberal girls rise first and most? Twenge sent me her data file (it’s a tricky one to assemble, across the many years), and Zach Rausch and I started looking for the interaction. We found some exciting hints, and I began writing this post on the assumption that we had a major discovery. For example, Figure 4 shows the item that Twenge analyzed. We see something like the Gimbrone et al. pattern in which it’s the liberal girls who depart from everyone else, in the unhealthy (external) direction, starting in the early 2000s.

Figure 4. Percentage of liberal and conservative high school senior boys (left panel) and girls (right panel) who agree with the statement “Every time I try to get ahead, something or somebody stops me.” From Monitoring the Future, graphed by Zach Rausch.

It sure looks like the liberal girls are getting more external while the conservative girls are, if anything, trending slightly more internal in the last decade, and the boys are just bouncing around randomly. But that was just for this one item. We also found a similar pattern for a second item, “People like me don’t have much of a chance at a successful life.” (You can see graphs of all 8 items here.)

We were excited to have found such clear evidence of the interaction, but when we plotted responses to the whole scale, we found only a hint of the predicted interaction, and only in the last few years, as you can see in Figure 5. After trying a few different graphing strategies, and after seeing if there was a good statistical justification for dropping any items, we reached the tentative conclusion that the big story about locus of control is not about liberal girls, it’s about Gen Z as a whole. Everyone—boys and girls, left and right—developed a more external locus of control gradually, beginning in the 1990s. I’ll come back to this finding in future posts as I explore the second strand of the After Babel Substack: the loss of “play-based childhood” which happened in the 1990s when American parents (and British, and Canadian) stopped letting their children out to play and explore, unsupervised. (See Frank Furedi’s important book Paranoid Parenting. I believe that the loss of free play and self-supervised risk-taking blocked the development of a healthy, normal, internal locus of control. That is the reason I teamed up with Lenore Skenazy, Peter Gray, and Daniel Shuchman to found LetGrow.org.)

Figure 5. Locus of Control has shifted slightly but steadily toward external since the 1990s. Scores are on a 5-point scale from 1 = most internal to 5 = most external.

We kept looking in the Monitoring the Future dataset and the Gimbrone et al. paper for other items that would allow us to test Filipovic’s hypothesis. We found an ideal second set of variables: The Monitoring the Future dataset has a set of items on “self derogation” which is closely related to disempowerment, as you can see from the four statements that comprise the scale:

I feel I do not have much to be proud of. Sometimes I think I am no good at all. I feel that I can't do anything right. I feel that my life is not very useful.

Gimbrone et al. had graphed the self-derogation scale, as you can see in their appendix (Figure A.4). But Zach and I re-graphed the original data so that we could show a larger range of years, from 1977 through 2021. As you can see in Figure 6, we find the gender-by-politics interaction. Once again, and as with nearly all of the mental health indicators I examined in a previous post, there’s no sign of trouble before 2010. But right around 2012 the line for liberal girls starts to rise. It rises first, and it rises most, with liberal boys not far behind (as in Gimbrone et al.).

Figure 6. Self-derogation scale, averaging four items from the Monitoring the Future study. Graphed by Zach Rausch. The scale runs from 1 (strongly disagree with each statement) to 5 (strongly agree).

In other words, we have support for Filipovic’s “captain their own ship” concern, and for Lukianoff’s disempowerment concern: Gen Z has become more external in its locus of control, and Gen Z liberals (of both sexes) have become more self-derogating. They are more likely to agree that they “can’t do anything right.” Furthermore, most of the young people in the progressive institutions that Filipovic mentioned are women, and that has become even more true since 2014 when, according to Gallup data, young women began to move to the left while young men did not move either way. As Gen Z women became more progressive and more involved in political activism in the 2010s, it seems to have changed them psychologically. It wasn’t just that their locus of control shifted toward external—that happened to all subsets of Gen Z. Rather, young liberals (including young men) seem to have taken into themselves the specific depressive cognitions and distorted ways of thinking that CBT is designed to expunge.

But where did they learn to think this way? And why did it start so suddenly around 2012 or 2013, as Greg observed, and as Figures 2 and 6 confirm?

Tumblr Was the Petri Dish for Disempowering Beliefs

I recently listened to a brilliant podcast series, The Witch Trials of J. K. Rowling, hosted by Megan Phelps-Roper, created within Bari Weiss’s Free Press. Phelps-Roper interviews Rowling about her difficult years developing the Harry Potter stories in the early 1990s, before the internet; her rollout of the books in the late 90s and early 2000s, during the early years of the internet; and her observations about the Harry Potter superfan communities that the internet fostered. These groups had streaks of cruelty and exclusion in them from the beginning, along with a great deal of love, joy, and community. But in the stunning third episode, Phelps-Roper and Rowling take us through the dizzying events of the early 2010s as the social media site Tumblr exploded in popularity (reaching its peak in early 2014), and also in viciousness. Tumblr was different from Facebook and other sites because it was not based on anyone’s social network; it brought together people from anywhere in the world who shared an interest, and often an obsession.

Phelps-Roper interviewed several experts who all pointed to Tumblr as the main petri dish in which nascent ideas of identity, fragility, language, harm, and victimhood evolved and intermixed. Angela Nagle (author of Kill All Normies) described the culture that emerged among young activists on Tumblr, especially around gender identity, in this way:

There was a culture that was encouraged on Tumblr, which was to be able to describe your unique non-normative self… And that’s to some extent a feature of modern society anyway. But it was taken to such an extreme that people began to describe this as the snowflake [referring to the idea that each snowflake is unique], the person who constructs a totally kind of boutique identity for themselves, and then guards that identity in a very, very sensitive way and reacts in an enraged way when anyone does not respect the uniqueness of their identity.

Nagle described how on the other side of the political spectrum, there was “the most insensitive culture imaginable, which was the culture of 4chan.” The communities involved in gender activism on Tumblr were mostly young progressive women while 4Chan was mostly used by right-leaning young men, so there was an increasingly gendered nature to the online conflict. The two communities supercharged each other with their mutual hatred, as often happens in a culture war. The young identity activists on Tumblr embraced their new notions of identity, fragility, and trauma all the more tightly, increasingly saying that words are a form of violence, while the young men on 4chan moved in the opposite direction: they brandished a rough and rude masculinity in which status was gained by using words more insensitively than the next guy. It was out of this reciprocal dynamic, the experts on the podcast suggest, that today’s cancel culture was born in the early 2010s. Then, in 2013, it escaped from Tumblr into the much larger Twitterverse. Once on Twitter, it went national and even global (at least within the English-speaking countries), producing the mess we all live with today.

I don’t want to tell that entire story here; please listen to the Witch Trials podcast for yourself. It is among the most enlightening things I’ve read or heard in all my years studying the American culture war (along with Jon Ronson’s podcast Things Fell Apart). I just want to note that this story fits perfectly with both the timing and the psychology of Greg’s reverse CBT hypothesis.

Implications and Policy Changes

In conclusion, I believe that Greg Lukianoff was exactly right in the diagnosis he shared with me in 2014. Many young people had suddenly—around 2013—embraced three great untruths:

They came to believe that they were fragile and would be harmed by books, speakers, and words, which they learned were forms of violence (Great Untruth #1).

They came to believe that their emotions—especially their anxieties—were reliable guides to reality (Great Untruth #2).

They came to see society as comprised of victims and oppressors—good people and bad people (Great Untruth #3).

Liberals embraced these beliefs more than conservatives. Young liberal women adopted them more than any other group due to their heavier use of social media and their participation in online communities that developed new disempowering ideas. These cognitive distortions then caused them to become more anxious and depressed than other groups. Just as Greg had feared, many universities and progressive institutions embraced these three untruths and implemented programs that performed reverse CBT on young people, in violation of their duty to care for them and educate them.

I welcome challenges to this conclusion from scholars, journalists, and subscribers, and I will address such challenges in future posts. I must also repeat that I don’t blame everything on smartphones and social media; the other strand of my story is the loss of play-based childhood, with its free play and self-governed risk-taking. But if this conclusion stands (along with my conclusions in previous posts), then I think there are two big policy changes that should be implemented as soon as possible:

1) Universities and other schools should stop performing reverse CBT on their students

As Greg and I showed in The Coddling of the American Mind, most of the programs put in place after the campus protests of 2015 are based on one or more of the three Great Untruths, and these programs have been imported into many K-12 schools. From mandatory diversity training to bias response teams and trigger warnings, there is little evidence that these programs do what they say they do, and there are some findings that they backfire. In any case, there are reasons, as I have shown, to worry that they teach children and adolescents to embrace harmful, depressogenic cognitive distortions.

One initiative that has become popular in the last few years is particularly suspect: efforts to tell college students to avoid common English words and phrases that are said to be “harmful.” Brandeis University took the lead in 2021 with its “oppressive language list.” Brandeis urged its students to stop saying that they would “take a stab at” something because it was unnecessarily violent. For the same reason, they urged that nobody ask for a “trigger warning” because, well, guns. Students should ask for “content warnings” instead, to keep themselves safe from violent words like “stab.” Many universities have followed suit, including Colorado State University, The University of British Columbia, The University of Washington, and Stanford, which eventually withdrew its “harmful language list” because of the adverse publicity. Stanford had urged students to avoid words like “American,” “Immigrant,” and “submit,” as in “submit your homework.” Why? because the word “submit” can “imply allowing others to have power over you.” The irony here is that it may be these very programs that are causing liberal students to feel disempowered, as if they are floating in a sea of harmful words and people when, in reality, they are living in some of the most welcoming and safe environments ever created.

2) The US Congress should raise the age of “internet adulthood” from 13 to 16 or 18

What do you think should be the minimum age at which children can sign a legally binding contract to give away their data and their rights, and expose themselves to harmful content, without the consent or knowledge of their parents? I asked that question as a Twitter poll, and you can see the results here:

Image: See my original tweet.

Of course, this poll of my own Twitter followers is far from a valid survey, and I phrased my question in a leading way, but my phrasing was an accurate statement of today’s status quo. I think that most people now understand that the age of 13, which was set back in 1998 when we didn’t know what the internet would become, is just too low, and it is not even enforced. When my kids started 6th grade in NYC public schools, they each told me that “everyone” was on Instagram.

We are now 11 years into the largest epidemic of adolescent mental illness ever recorded. I know so many families that have been thrown into fear and turmoil by a child’s suicide attempt. You probably do too, given that the recent CDC report tells us that one in ten adolescents now say they have made an attempt to kill themselves. It is hitting all political and demographic groups. The evidence is abundant that social media is a major cause of the epidemic, and perhaps the major cause. It's time we started treating social media and other apps designed for “engagement” (i.e., addiction) like alcohol, tobacco, and gambling, or, because they can harm society as well as their users, perhaps like automobiles and firearms. Adults should have wide latitude to make their own choices, but legislators and governors who care about mental health, women’s health, or children’s health need to step up.

It’s not enough to find more money for mental health services, although that is sorely needed. In addition, we must shut down the conveyer belt so that today’s toddlers will not suffer the same fate in twelve years. Congress should set a reasonable minimum age for minors to sign contracts and open accounts without explicit parental consent, and the age needs to be after teens have progressed most of the way through puberty. (The harm caused by social media seems to be greatest during puberty.) If Congress won’t do it then state legislatures should act. There are many ways to rapidly verify people’s ages online, and I’ll discuss age verification processes in a future post.

In conclusion: All of Gen Z got more anxious and depressed after 2012. But Lukianoff’s reverse CBT hypothesis is the best explanation I have found for Why the mental health of liberal girls sank first and fastest.

#Jonathan Haidt#Greg Lukianoff#Reverse CBT#reverse cognitive behavioral therapy#cognitive behavioral therapy#emotional fragility#fragility#emotional reasoning#external locus#internal locus#victimhood#victimhood culture#Generation Z#Gen Z#anxiety#depression#mental health#mental health issues#trauma#personal identity#hellsite#Tumblr culture#religion is a mental illness

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am a firm believer in easily flustered Locus

Especially when it pairs so well with earnest and honest Donut with no respect for personal space!

#rvb#rvb donut#rvb locus#locnut#for realsies#franklin delano donut#samuel ‘locus’ ortez#no clue how legible locus’ internal yelling is but oh well#my art#batsy art

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

my temp team lead is the sweetest person ever (my other team lead was too but she’s on maternity leave). we had a one-on-one today and ended up talking for an hour and i opened up about my struggles, she is on a very similar wavelength to me anxiety-wise and she offered to roleplay calls or do anything else that might help me feel better about it. and she was very understanding about my search for a new job. it’s been worth it to be true to myself

#post#she also gave me a refresher on the internal vs external locus of control and she was like ‘you’re here (internal)#and this (external) is creeping in’ which i feel is very true#idk! people are decent

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

M offered me a morning beer and I turned it down

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nick Walker via FB:

"If you can’t choose to not be offended, then you’ve made the grave strategic error of putting power over your mental well-being in the hands of everyone but yourself."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Thaumiel ~ rule in hell or serve in heaven)

God is truth; Satan is rebellion.

Whyever should I do as you say?

God is love; Satan is acceptance

Whyever should I care for a love that will not take me as I am?

God is perfection; Satan is discernment.

Whyever should I act as if there’s nothing wrong with this world?

God’s will is absolute; Satan is responsibility.

Whyever should I sit idle in the face of your cruelty?

God will provide; Satan is ambition.

Why should I wait on hope instead of being the most that I can be?

God contains everything; Satan is individuality.

Whyever can I not be my own reason for being?

God is omniscient; Satan is the unknown.

Whyever should I act as if the truth were obvious?

God is strength; Satan is doubt.

Whyever should I take your promises on faith instead of thinking for myself?

God is the divine plan; Satan is freedom.

Whyever should I content myself with what scraps are thrown my way?

God is one; Satan is plurality.

Whyever should you be the only one who gets to say “I am”?

#feelings#baby tries to art#poetry#freeverse#something something internal locus of control#metaphor for free will and autonomy#littany against repression and the constant 'I Am Worm' of much spirituality & religion

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

either youtube recommendations broke badly for me or drag race fandom is worse than i thought

#yes im watching funnie videos i am doing SO BADLY lmao#i tried journalling abt it and al i came up with was the sentence 'what do i need to stop living in fear?'#and didnt have an answer lmao#truly in a place where the terror feels external and real and i can not do internal locus of control shit abt anything#and then! when ive worn myself out w panic and feel kind of ok i go hmmm suspiciously quiet in here#and go looking for the scary thoughts!#...maybe i should open my mind to the bible affirmations lol#anyway i am a drag race elder - id basically already stopped watching by triexie and katya's season lmao#and if the christians are into it now i was right abt dropping it#but the youtube videos are funnie

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

not an internal or external locus of control but a secret third thing (everything good that happens in my life is just luck and circumstance but everything bad is 100% my fault)

#i am actually doing fine despite how this post sounds like a cry for help#i was just thinking about how my locus of control seems to have varied between external and internal over the years#and realized that broadly speaking this is the pattern i’m currently in

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am gaitiem, God of my mind and my life

I am Arran, god of the most important thing

EDIT: if y'all don’t wanna use your name use your username

67K notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Eva Kurilova

Published: Jan 13, 2024

Locus of control is a term used to describe an individual’s belief about what factors control their lives. Those with an internal locus of control have a strong sense of agency and believe that their lives are influenced by their own actions and abilities. Those with an external locus of control feel that they are subject to luck, environmental factors, and other people’s actions.

Most people fall somewhere on the spectrum between an internal and an external locus of control, as this is reflective of life itself. There is a lot that we can control but a lot that we can’t as well. However, regardless of what is objectively true in any given situation, our preference for one view or the other has a major impact on our lives.

Those with an internal locus of control are more resilient, motivated, and independent, have a higher capacity for self-control, are better able to manage stress, and enjoy overall higher levels of mental and physical health. Those with an external locus of control, on the other hand, lack self-confidence and self-efficacy, blame others for their shortcomings, are less likely to take accountability, and experience worse mental and physical health outcomes. They are also more likely to have a mindset of victimhood.

Research abounds expounding the positive associations between an internal locus of control and factors like academic success and favorable work outcomes, as well as between an external locus of control and negative outcomes, like criminal offending. Helping people develop a greater internal locus of control has long been a goal of psychotherapy.

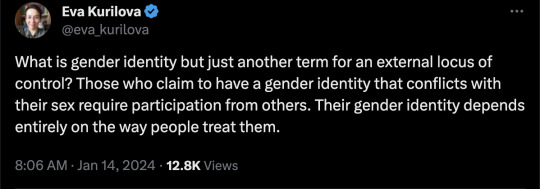

And yet, when it comes to the concept of gender identity, all of this knowledge and research is thrown out the window. After all, what is gender identity but just another term for an external locus of control?

Those who claim to have a gender identity that conflicts with their sex require participation from others. Their gender identity depends entirely on other people’s perceptions and on the way people treat them. They cannot concretize their identity simply by going about their lives, doing their job, practicing their hobbies, and fulfilling their roles as friends and family members—which is what an identity really is.

Instead, trans-identified individuals often try to artificially manifest a fantasy in their heads by forcing others to call them by a different name and pronouns and to pretend they see them as anything other than their sex. Some aren’t even satisfied knowing that others are merely playing along—they go further and demand others actually brainwash themselves into perceiving them as they wish to be perceived.

Furthermore, when someone is trying to manifest a gender identity, their locus of control sits not just in other people but in the rest of the world at large. They rely on external accouterments like clothing and makeup to signal what “gender” they are trying to appear as. They may go as far as to rely on external hormones to try and change how their body looks and even rely on surgeons to physically alter their body parts.

Obviously, all of us rely on the external world. None of us are entirely self-sufficient, and even if we have a strong internal locus of control, there is still much that is out of our control. But this is not the same as relying solely on the external world to recognize and manifest your identity for you.

I should also add that not all trans-identified people are like this. I think the locus of control is one of the main differences people implicitly note between trans-identified people who cause problems and those who don’t. This then gets clumsily translated into speaking about trans people with an internal locus of control as “real” or “actual” or “good” trans people.

I don’t believe there is any such thing as “true” trans. But I do believe there is a big difference between people who decide to transition and consider the onus to be on themselves to pass and be treated as the opposite sex and those who think the onus is on the rest of the world to make them feel like the opposite sex. I think this is the split that people pick up on when differentiating between the trans-identified people who really do just want to live their lives and those who want to tear the world down while paradoxically relying on it for their entire sense of identity.

(It is also my experience that trans-identified people in the former camp are less likely to insist that they have a “gender identity” and more likely to view themselves as having a mental disorder—gender dysphoria—that they are managing as best as they can).

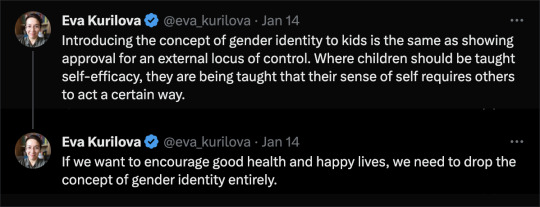

Unfortunately, trans activists, doctors, teachers, counselors, politicians, and “experts” of all stripes are encouraging all trans-identified people to take on the latter mindset. They encourage an entirely external locus of control which then invariably develops into a victimhood mentality. Trans-identified people with an external locus of control come to believe that because they have no power to improve anything for themselves the world owes it to them.

This is what makes it all the more pernicious that this ideology is being pushed on children. Introducing the concept of gender identity to kids is the same as showing approval for an external locus of control. Where children should be taught self-efficacy and resilience, they are instead being taught that their very sense of self requires others to act a certain way and the world to comport itself to their whims. It’s a disaster that isn’t just waiting to happen but that is already well in progress.

There is no way to continue teaching the concept of gender identity to children and spreading it throughout society while encouraging people to develop an internal locus of control at the same time. The two pathways are mutually exclusive. If we want to encourage good health and happy lives, we need to drop the concept of gender identity entirely.

==

I've said it before and I'll say it again: if your "gender" can be invalidated by others not participating, like gods, it was never real in the first place. You can't claim "an internal sense of self," and then also claim it requires external validation. That's "I have a personal relationship with Jesus" and "I want to pass laws based on what Jesus wants." It's either a private personal matter, or a matter of public interest. You can't have both.

And in both cases, attempting to do both results in authoritarianism.

#Eva Kurilova#gender identity#gender ideology#queer theory#external locus#internal locus#locus of control#no debate#no debate is over#religion is a mental illness

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#locus of control#self help#self improvement#self awareness#self reflection#external locus of control#internal locus of control#focus on what's in your control#embrace life#work with life#work with yourself#academia#art#life#self love#self care#healing#embracing change#embrace yourself#living#healthy living#mental health#mindset#growth mindset#you got this!#good luck#take care of yourself#do your best#you deserve it!#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Note

Is there a chance that we can have both Internal and External locus of control ?

Yes we do. We can take control but also let the universe decide for us.

0 notes

Text

I didn't have to wait for something good to happen, I could create it on my own.

0 notes

Text

venus retrograde ends on the 3rd

0 notes

Text

I'm glad Tumblr is available to anyone who wants to be on it because otherwise i would never get to see this unhinged rant about a mid Disney movie delivered by a Protestant who tries really hard to tiptoe up to the line of "I don't like Disney because they're not Christian anymore" without saying anything explicitly Christian. Really can't get this anywhere else.

If you haven’t seen Wish yet and you love Disney, do not go see it. I am telling you now. It is ripping out the hearts of the Disney movies you love and then waving their corpses around as if celebrating those hearts.

I’ll explain why, again: the message of Wish? Awful. Anti-Disney.

But they've been doing this for a long time. Saying one thing with their movies, and saying another with their PR and Disney Parks Soundtracks.

I'll explain.

Main Idea of Disney's Wish (and the You Are the Magic theme park song and merch): "The power to make your wishes come true is in you."

≠

Most Disney Movies' Idea on How to Have Wishes: "Do what's right, (trust a higher power) and something even more wonderful than what you wished will happen."

Don't try to argue with me about this. You have to look underneath the slogans and the sweater designs and the song titles to what the stories actually support to acknowledge this.

Because you can’t say “do what’s right” has power unless you answer the question “who gets to decide ‘what’s right?’” (Which, coincidentally, is a question Wish brings up and then doesn’t answer.)

Audiences of Disney used to accept that wishing on a star was much like prayer; there’s something you long for, and it’s out of your hands, but you wish for it and you do what you know is right in the meantime. And you’re not crushed, you’re not downhearted, because somewhere in your mind you trust that the combo of those two things—wishing on a higher power and diligence to do what’s good—will be what makes your wish come true.

Trust in a higher power—COMBINED WITH:

—diligence to do what’s good.

The Blue Fairy (higher power) gave Geppetto his wish specifically because he had demonstrated commitment to do good, whether he got what he wanted or not. The Fairy Godmother (higher power) gave Cinderella her wish specifically because she kept on being kind and good to low creatures like mice and wicked stepsisters, whether she got what she wanted or not.

Do you know why that combo (higher power + diligence to do good) is impactful? Timeless? Important?

Because it’s selfless. You want something, but you’re not going to sacrifice doing the right thing to get it. You’re not going to focus so hard on making what you want a reality, on your own, that you miss out on things that could be more important than what you want. And, you’re not so self-focused as to believe that if you don’t do it, it won’t get done.

Jeez, that’s the whole point of The Princess and the Frog!

Tiana wishes to have her own restaurant, and she believes that only her own hard work will grant that wish. She misunderstands her dad’s advice before he dies. She isn’t willing to trust a higher power combined with her own diligence to do good—she only trusts her own ability.

It’s not until she realizes that Ray, the character of faith, was right all along that she learns—what she wished for was too self-focused. It wasn’t complete without love. Something bigger than herself. And getting that was never going to happen just based on her own hard work.

But you know what? It was never going to happen just by a “higher-power” flavored shortcut, either. Because Facilier offers her her wish if she’ll just trust him, no hard work needed. But what does she say?

Trust in a higher power + diligence to do what’s right = selflessness, and getting more than you could have ever wished for. And if your wish is selfish, doing those two things will change your wish into something selfless.

More examples? Get ‘em while they’re hot, in case Wish made you forget, just like the current #NotMyDisney executives have forgotten, what real Disney wishes are for.

Belle wishes to have adventures in the great wide somewhere--but when she's imprisoned and that chance is taken from her it's not reversed because she worked hard to make her wish come true. It's granted because she gave up her wish for her father: she just did the right thing, regardless of her wish. And in the end, she does get what she wished for, which is adventure in an enchanted castle...and much more, because she gets true love, a throne, and a castle full of friends.

How about the One Who Started It All? The one Wish is failing to pay genuine tribute to?

Snow White wishes for someone to love her, and he does--but when they're separated, she does not exercise power to make The Prince come back to her. Instead, she loves who she can where she’s at—the Dwarfs. In the meantime, she has faith that he will keep his promise, and that pure trust in a higher power outside of her control is a big contributing factor to why the Dwarfs come to love her, and learn from her...and in the end, even more than she could've wished happens. He does take her to his castle, but she also has seven new friends who also love her, and the Queen is dead. And she didn’t need to use “the power in her” to work harder and get it done. She just needed to not focus so much on herself at all.

How about a male main character? One who’s wish starts out selfish, but after learning to wish on a higher power and be diligent to do the right thing, gets more than he could wish for?

Aladdin wishes to be somebody different (somebody he believes Jasmine could love, somebody who lives in a palace and is respected and “never has any troubles at all.”)—but doing everything in his own power for that wish proves that it was selfish all along; so he switches to doing the right thing, regardless of if his wish comes true, and he gets even more than he could’ve wished. He gets real love with Jasmine, he gets his friend Genie, and he gets to be free from feeling “trapped” because he doesn’t have to hide who he is anymore.

Or Simba?

Simba wishes to get to do whatever he wants as King—but when Mufasa dies and he’s convinced it’s his fault, it isn’t for that wish that he goes back to Pride Rock to confront his past and his Uncle. It’s because he had an encounter with a higher power—his father—that helped him to realize his wish was selfish all along. He gives up the selfish wish, and he goes back to take his place as king, not so he can do whatever he wants, but so that he can take self-sacrificial responsibility that comes with ruling. And because he just does the right thing, finally, he gets more than what he wished for.

How about something more recent? Zootopia.

Judy wishes to make the world a better place by proving she can be what she wants to be and catching bad guys—but when she tries to make her wish happen on her own, in her own abilities, she fails and is forced to realize that she should’ve been looking for help by understanding “bad guys,” like Nick. It’s only after she humbled herself, admits she’s wrong, and changes her wish from “proving I can be what I want and catching bad guys” to “proving that understanding each other makes the world a better place” (much less self-focused) that her wish comes true—and so much more. She does make the world a better place, and she does get to catch bad guys, but she also gets to befriend one who was a good guy all along, and become all-around more effective at her dream job.

This is how Disney always has been. Because it’s at the heart of good storytelling, and even life (not to get too dramatic.)

The power is not in you. Because it’s not about you. Self-sacrifice, faith, and doing the next right thing regardless of if you get your heart’s fondest desire is what makes more than just your wishes come true. And there has to be belief in a higher power to make that message powerful.

But Wish?

Not only is it bad at showing instead of telling. Not only is it lazy and soulless.

But it’s characters rip the Star out of the sky and say “don’t wish on this. Wish on yourself, to get what you wish for. You don’t need a higher power. You don’t even need to sacrifice to do what’s good—whatever you do is good, because you are the one doing it.”

That is wrong. That is not true, and it is not powerful. There’s no sacrifice in focusing on or placing your trust totally in yourself, and it undoes every good thing Disney has done up until now.

And it undoes it on the 100th anniversary, and it flaunts Easter eggs of the very things it’s undoing.

#sorry to my mutuals for putting this on your dash#but also its really funny#anyways L + you lack an internal locus of control

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

fear of god

prompt: There's someone outside the spacecraft. You don't remember them being part of the crew. Part 4 masterlist

-

At the quantum level, an electron can behave as both a wave and a particle. It is the act of observing it that confines it to a single form. The electron that once could’ve passed through multiple openings at once is forced to choose a single path when observed.

Because what the eye sees becomes—

“—real,” you whisper, staring up at the face hovering in the window beside your bed. His smile doesn’t waver. “You can’t be real.”

“Sorry about the other day,” he says, instead of answering. “I got a bit lost after you left.”

Again, you pinch the soft skin of your thigh to wake yourself up and twitch when the pain sets in. The reassurance that you’re still awake doesn’t go a long way towards reassuring you.

“This isn’t real,” you repeat to yourself, squeezing your eyes shut and breathing heavily out through your mouth. “This isn’t real.”

Your words are met with a silence so profound that it almost feels as though you’ve plugged your ears, until you open your eyes and he’s still there, waiting right outside the window.

The blue lights around the inside of the window glow soft against his dark skin. You can make out the finer details of his face up close—the smoothness of his skin; the faint scar on his cheek; the fine grooves in his plush bottom lip. Too beautiful to have spent the last several days without food or water or sleep or fresh oxygen. You, with access to all of those resources, feel grimy; gritty. Skin tight against the bone, and hollowed.

“Was that you? Before?” you ask, thinking of the astronaut you saw drifting out in the distance, so lifeless and limp that you imagined the body within it long expired.

He nods. The motion is slow, deliberate; still that sluggishness analogous with zero gravity.

You wait for him to volunteer more information, but he just smiles wordlessly at you. It’s difficult to know where to begin. You’ve always been the kind to break a problem down into smaller, more manageable parts, but with this you don’t even know where to start. Its bigness is all you can focus on. The enormity of it.

“Where did you go?” you ask instead. “You weren’t—…you were gone when I came back. We couldn’t find you.”

He blinks. “Elsewhere.”

“You can…move around out there?”

“I can.”

His deliberate evasiveness frustrates you. Ostensibly one-dimensional with his glib charm and easy smile, but with an unplumbed depth. His response provokes more questions than it answers, and you can tell that it’s intentional.

But again you’re prescribing an internal locus of control to an apparition that has been proven to exist only in your head. It can only supply you with information that you already have.

And that’s the real quandary, isn’t it? The thing that has you whispering softly to yourself oh no oh no oh no oh no in the quiet of your room. Your body knows that the front door of your mind lies on its side, ripped from the hinges, dirt mounds blackening the entryway. And now outside stands a man, waiting to be let in.

“How am I able to hear you?”

He smiles. “You must just want to listen.”

You huff out a breath through your nose. There it is again.

“Who are you?” you ask, and you know that his answer won't matter. It won't matter because it won't be real. Because it's just you in your head and the words are too loud and whatever sickness is in your mind has crystallized in the body of a man that stares at you with a gaze too intense, too penetrating for what he is.

“You can call me Gaz,” he says simply, teeth peeking out from behind his lips when he enunciates the name. Glinting sharp like bone in the blue light.

His answer makes you blink. It doesn’t seem like a name that you would come up with, but the mind works in mysterious ways. You didn’t think it could conjure up a person either, and now look at what’s happening to you. And it is happening to you, of that you’re sure.

“Are you going to let me in?” he asks before you can open your mouth again.

He presses his gloved hand to the window. The folds in the fabric spread with his fingers, the pads of his fingers flecked with dust and grime, worn from years of use.

You give a curt shake of your head.

“Love…” Gaz says warningly.

In the few days since he first appeared in the window, you’ve never heard him use that tone. You’re not too proud to say it frightens you. Whether he’s real or just in your head, so far Gaz has been perfectly affable, and you’re not sure you’re willing to face the implication that he might not always be that way.

“I need to sleep,” you plead. “T-tomorrow—I’ll…I’ll think about it tomorrow.”

You press a button on the wall that drops a panel over the window with a quiet shunk, blocking Gaz from view.

When he knocks again, a shiver ripples down your spine. Guilt twists your insides up in knots. All you can do is pull the comforter over your head and block your ears.

By morning, the temperature in your room has dropped a degree. You bundle up in a thicker sweatshirt and boots before going for your morning cup of coffee, but for the first time since takeoff all those months ago, you head for your work station instead of sipping your coffee in the cockpit.

You start to hear him no matter where you are on the ship, a window no longer necessary. Always it comes after two solid raps against the hull of the ship, the sound jolting your heart into a frantic beat, pulse fluttering wildly under your skin. And then his voice, muffled through the layers of aluminum and titanium alloys, but intelligible despite the impossibility of it all.

Sometimes, you respond. Just a few words to acknowledge his existence, even when the wall separating the two of you is impermeable, only his voice accessible to you.

That makes it worse somehow though. Displaces his voice from his body, forcing you to reckon with his presence like a symptom of a bicameral mind, your own thoughts projected from you into the world. What difference is there between his voice and an audio hallucination? You should know better than to indulge in it.

You’re beginning to understand the real root of the problem. The crux of it all. There’s a box in your mind labeled psychosis, and in the months of prolonged isolation and discomfort, you’ve inadvertently unshelved it, pulled it out of its storage space and peeled the lid open, all of its contents now released into the world.

The thought is terrifying. You wonder if you can even trust your own mind, if everything is now compromised. Can you even trust what you see in front of you, or have you made it up as well? The thought is so disturbing that it paralyzes you in your bed at night.

You’ve taken to sleeping in the medbay because it’s one of the few rooms without access to any exterior walls. Several other crew quarters separate it from the hull, while the main corridor runs along the other side. It’s the only place where you’re able to get a decent night’s sleep, though the lights stay on, fluorescent white at all times, programmed to stay at full brightness in case of an emergency.

Even the sight of your own reflection makes you flinch until you realize it’s just you.

One twenty-four hour period cycles into the next, pulling you into its embrace like crossing over an event horizon, your future self already distended out in front of you.

In an effort to finally put you to good use (you try not to resent the implication when it’s framed like that), Farah tasks you with conducting pressure checks on the fuel tanks and lines around the ship while she continues to focus on the issue with the cruise control. You’re tasked with attaching a pressure gauge to the tank and increasing the pressure while keeping an eye out for any leaks or drops in pressure. A task simple enough that even the uninitiated could perform it. Busywork.

You shut down the part of you that beats on your chest and demands that you leave. That this isn’t your job; you were brought aboard for a particular purpose and this isn’t it. You could be conducting your own research instead in the comfort of your lab, ensconced in data on antimicrobial resistance in space or microgravity-induced orthostatic intolerance. Not checking fuel tank pressure.

Someone raps their knuckles against the wall nearest you from the outside of the ship, startling you.

“Shit,” you curse, the pressure gauge slipping out of your hand and clattering to the floor. You sigh when you bend down to pick it up and wince when you notice a crack in the glass where it hit the floor.

“Love? Is that you?” Gaz asks from the other side of the wall, voice muffled.

Ignoring his voice doesn’t keep your heart from beating harder. You try to focus instead on the task at hand, pressuring the tank to fifteen hundred psi and waiting for the needle to stabilize on the gauge. Nothing abnormal. You jot it down and move on to the next tank, removing the gauge and starting the process anew.

Another thump against the hull, the sound sending a jolt through your body.

“I know you’re there.” He sounds amused. “You’ve been avoiding me.”

How could you avoid someone in your head? You almost say as much but then catch yourself on the verge of opening your mouth. You turn back your task, scrolling down the checklist on your tablet.

There’s an edge to his voice the next time he speaks. “This is starting to annoy me, love.”

“I’m not avoiding you,” you whisper, finally breaking, the stylus nearly slipping from your clammy hands. Brows scrunched, eyes shut tight. Another breath out to stabilize yourself.

“Ah, there you are,” Gaz hums. “Thought you didn’t want to talk to me anymore.”

Just ignore it, you think, breathing in and out again.

“You’d rather talk to Farah than me,” he says when you don’t respond, almost accusatory, and you nearly brush it off until you register what he said.

“How do you know her name?” you hiss under your breath, turning your head to stare at the panel that his voice emanates from behind.

“I thought I was just in your head,” he says, amused again. Voice lighter than a moment prior. Easygoing as ever.

You worry at your lower lip until the skin threatens to break. “Yes, but—”

“Who are you talking to?”

Your head whips around at the sound of Farah’s voice. You hadn’t heard the cargo hold doors open, but she stands in the doorway, staring at you with an unreadable expression, shoulders squared and hands on her hips.

Your instinct is to ask her how long she’s been standing there, but that won’t serve you in the long run. You almost want to ask if she heard his voice too, but you don’t think you could handle her confirming to your face that Gaz’s voice is all in your head.

“…No one.”

Her face hardens and you wonder if you made the wrong call choosing to lie to her. But what else should you have said? The wall behind you remains conspicuously silent.

The next few seconds under her gaze feel endless. Eventually though, Farah pivots on her heel without another word and leaves the way she came, the doors sliding shut behind her.

The room bellows its cold ire. Only the sound of your own breathing reaches your ears.

An hour passes. Possibly longer. The stress eats away at your insides. Though you don’t cross paths with Farah for the rest of the day, you can’t help the way every sound makes you flinch and glance towards its source. Jumpy; paranoid.

You make yourself dinner when the galley is still empty and eat in the medbay instead of with the rest of the crew. The peppery aftertaste is more prominent than usual while you eat; you almost have to choke your food down. Almost metallic, like antiseptic.

It happens again on your way back to your quarters. The lights cycle with the night and dim in the hallway, a soft pale glow like a low-hanging moon illuminating the floor in front of you.

You catch him in the corner of your eye this time, no knock to signal his presence. Just an astronaut hovering outside the window, nearly translucent with the absence of light. The fear that overcomes you is almost animalistic until it settles into the folds of your skin like an ointment rubbed in, and you turn to face him.

It’s the same but different. You know what he wants. What he’s waiting for.

“I don’t think I can let you in,” you whisper, looking away from the window to the other side of the hall. His gaze seers into the side of your head.

“Why not?” It’s the first time Gaz’s voice has sounded cold to your ears. The hair on the back of your neck stands on end.

“I’m worried you’re not real. That maybe you’re just in my head. And I can’t—” You bite your lip, swallowing the warble in your voice. “—I can’t let them know I’m crazy.”

Let them know. As if it were a foregone conclusion. As if you’ve already passed the point of no return. But what other conclusion could you draw from your observations as of late? The constant disappearances and reappearances, his voice in your head only when you’re alone. His voice in general, somehow audible despite there being no medium for it to pass through. You’ve been ignoring his anomalous properties because you’ve been desperate to believe that your mind hasn’t been compromised. That you aren’t a danger to the people around you—a voice in your head telling you to open the airlock when there’s nothing out there in space.

When you turn your head, he’s still there, eyes stony behind the visor of his spacesuit. He tilts his head and the visor glints black for a second, suddenly opaque, obscuring his face.

He looms like a figure straight out of death, imposing even from the outside of the ship. Your arms hang limp at your sides, locked in place under his gaze. Even the thought of moving fills you with dread.

But he isn’t real; he’s just in your head.

When Gaz lifts his head again, his visor clears and his smile is pleasant again, back to what it once was.

“I’ll prove that I’m real. Wait for me, love.”

And then he’s gone, the view beyond the window night sky black. Gone between one blink and the next; faster than light.

#ceil writing#cod x reader#gaz x reader#gaz/reader#kyle gaz garrick x reader#kyle garrick x reader#kyle garrick x you

643 notes

·

View notes