#inland wetlands

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What types of water bodies can we considered as "wetlands"?

Wetlands are Land areas that are saturated or flooded with water either permanently or seasonally.

Inland wetlands:

Marshes, lakes, rivers, floodplains, peatlands and swamps

Coastal wetlands:

Saltwater marshes, estuaries, mangroves, lagoons and coral reefs

Human-made wetlands:

Fish ponds, rice paddies and salt pans

#inland wetlands#coastal wetlands#human-made wetlands#2 february#world wetlands day#wetlandrestoration#wetlands#salt pans#rice paddies#Fish ponds#Saltwater marshes#estuaries#mangroves#lagoons#swamps#coral reef#Marshes#lakes#rivers#floodplains#peatlands

0 notes

Text

Some coast striker concept doodles, mostly to showcase their weirdo double tongue + i love drawing teeth. Also whelps are see through when they hatch, most lose this quality as they grow, but a few (especially in the Deepwater) keep their translucency well into adulthood.

A small fun fact, many humans call coast strikers "grinning deaths" as their toothy snarls can look like a grin to a person. Given their amount of teeth and their two tongues, other AshWings can find them a bit unsettling

#wings of fire#wof#ashwing#dragons#art#oh yeah remember those region variation drawings i made? im dividing the coast into three regions: the deepwater (open ocean/seabed)#the saltwater (the coastal cliffs) and the freshwater (more inland in the peninsula lots of#wetlands and rivers and lakes. kinda like everglades and mangroves in some areas#however im not sure about the eggs. hmmmm#bc its like this OR regular eggs with an almost conical shape which i believe is common in cliff birds? so the eggs spin on the same place#instead of out of the nest and falling to their doom

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

That It Is (Astarion)

Pairing: Astarion x Reader [Baldur's Gate 3]

Summary: After a long day trudging through the sunlit wetlands, you discover your bedroll is waterlogged, and that Astarion has lost his in the swamp... AKA, the classic: ‘oh no, there’s one bed, whatever shall we do, darling?’ (Act 1 spoilers).

A/N This one has a tad more enemies-to-lovers vibe to it, but sweetness nonetheless.

Masterlist

Night was creeping over Faerûn.

After a day of toiling through the deep murk of the sunlit wetlands, your party had found refuge: an abandoned shack a little ways inland from the swamp. It was unassuming enough through the fog that Gale had tripped over its porch, and even Astarion’s darkvision had missed the contours of the old building tucked away.

But once scoped, you found that the place was empty. Shadowheart deemed it safe enough for you to unpack your bedrolls and dry your waterlogged boots. So you did just that—even managing to rouse a fire with an ignis and a few pieces of damp wood.

The flames took a few moments to blaze to life, but once they did, the warmth was heavenly on your skin. One by one, you started to shed your wet outer garments, laying them out by the fire.

“Oh, bloody hells!”

A voice rang out over the crackling hearth. You turned to find Astarion on his knees, rummaging through his supply pack half-deranged.

He flung the contents out onto the floor: some soggy books, a cask of water, pristinely-folded clothes. Then he promptly turned the pack upside down, seemingly devestated to find nothing else inside.

The rogue threw his hands up. “Gone,” he declared, with a dejected sort of laugh. “Be it just my luck after trudging through this gods forsaken waste—”

From the corner of the room, Shadowheart stopped wringing out her gloves. She gave you a look. Deal with him, she said through the shared connection.

With a sigh, you conceded. “What’s wrong, Astarion?” You stood over the pale elf, hand on hip, “Broken a nail?”

Irritation painted his face, but his demeanour remained playful.“Ha! Hilarious as always, my dear,” he replied, without sparing you so much as a glance. “Alas, I’m afraid my situation is a tad more dire.”

You clicked your tongue. “Go on.”

Astarion stood up, taking a moment to dust himself off. “It seems I’ve lost my bedroll somewhere in that bloody marsh,” he finally admitted.

Somewhere across the room, Shadowheart’s snort was quickly covered up by a faux cough from Gale. “Oh?” you said, “I thought elves didn’t need to sleep.”

Astarion shot you a glare. “And do you need to dry your clothes by the fire? Need to eat tonight or, gods forbid, drive us half mad with your infernal singing sometime tomorrow?”

He stalked the cabin, pointing vivaciously at your drying garments, and menial rations you’d hoped wouldn’t spoil.

You felt your brow furrow at his display. “No need to be rude,” you said shortly. “Today’s been hard on all of us.” Pushing past him, you quickly retrieved your own pack from its place near the door. “Here—just take mine.”

Fishing around the bag, you searched for your own bedroll before producing it for him. Astarion let out a sound of disgust.

“You could at least try to be grateful, Astarion,” you started. Then you felt it; your trusted bedroll squelched in your hand. It was pasted with a layer of thick algae, and some other mysteries you couldn’t discern. “Son of a—” you cursed. How had you forgotten when it rolled into the marsh earlier in the day?

A hand found your shoulder. “Thanks for the generous offer, my dear, but I think I’ll pass,” Astarion said, proudly. He then flicked a rather large leech off your bedroll, causing Gale to shriek when it landed at his feet. “I’d like to remain the only bloodsucker around here.”

You were about to quip back, when Astarion stepped closer—enough so that his breath dusted your cheek when he spoke. “And I think I spy a bed in the other room. That should do me just fine.”

It took you a moment to unravel his words. By the time you did, he’d already traipsed halfway across the cabin. “Hang on a moment,” you called after him,“I already staked my claim on that earlier!”

“Hmm?” the elf hummed, feigning ignorance.

The audacity. You shot a glance back at the wizard, who immediately threw his hands up in surrender. “Oh no, you don’t,” warned Gale, “I’m staying out of this one.”

To his left, Shadowheart looked equally unbothered by your plight. You scowled at them both.

It was going to be a long night.

—

The cabin was quiet. It had been some time since you had rested in a place with a roof and four walls. There were no beasties lurking near your camp, or dangers beyond the trees. The only threat to your person was Gale’s snores coming from the main living space. He’d taken refuge on the floor, whilst Shadowheart seized the chaise lounge.

It was a comfortable night. So in principle, you should have had no problem falling into a dreamless sleep. Especially given the feather bed at your back.

“You know, my dear,” Astarion whispered, “I might have agreed to this arrangement, but that was under the condition that you get some sleep.”

You tried not to startle, but his words sounded so close to your ear. It made your skin prickle with anticipation—despite doing your utmost not to show it.

“I think you’ll find I was the one who was forced to agree,” you countered, “and I’m trying. You just—”

Shifting in the bed, you turned around to face the elf beside you. He was leaning on one arm, gazing up at the wooden ceiling as though he were watching the stars. His eyes found yours. “I what?” he asked.

You could hear his grin; he was teasing you. But you wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of backing down now. “You make me nervous,” you answered bluntly.

He did not reply. Each second of silence that passed made you more and more uneasy. You couldn’t see him well in the dark. And as much as you tried to make out the contours of his face, you knew for sure discern every line on yours—every expression you hoped to conceal. “And why’s that?” he finally asked.

You let out a huff before falling onto your back. “You know why. Stop acting so smug—It doesn’t suit you."

Astarion’s laugh made its way to you. “Everything suits me, darling.”

A witty remark alluded you, so you opted to stay quiet. Sleep was what you needed right now. The gods only know how deprived you were of it.

So you plumped your pillow and made yourself comfortable. Then you gathered some blankets to yourself. A yawn left you, but your mind felt anything but relaxed. You readjusted again, this time your body pressing into Astarion's. He moved to accomodate you; you stiffened in response.

“Will you stop wriggling around? I can’t so much as move without you flinching."

At his words, your breath hitched. You were midway through an apology before he interrupted.

“Look at me,” he said.

Despite the darkness, his thumb perfectly traced your jaw until it found the space just under your chin. Gently, he coaxed your head up.

“You know I’ve drank from you, right?” You gasped at his candidness. “I've felt your pulse on my tongue and your blood coat my teeth,” he went on. “Hells, I have your thoughts swimming in my head far more often than you probably realise.”

He paused for a moment, and in that time you breathed twice as fast as you ought to.

“You’ve allowed me that much, so sleeping beside me like this?” he said, with a lightness to his voice, “that shouldn’t matter, now should it.”

You couldn't reply. His words were likely meant to comfort, but they had only the opposite effect. As his fingers brushed your cheek, you immediately pulled back—hoping he did not feel the way you burned for him.

“No. I guess not?” you stuttered.

“Good,” came his reply. “Now sleep. I promise I won’t bite”

He returned to his side of the bed, not overstepping the invisible boundary you'd drawn earlier that evening.

And on your side, you were left to press down whatever feelings threatened to bubble to the surface. You weren’t quite ready to let them out yet—not when you couldn’t see clearly the face he would make in response.

Right now, you just needed to sleep.

So you focused on the snores echoing from the other room, the rain pattering the windows, Astarion's breaths and your heart—which, without realising, had recently started to beat for him.

“Goodnight, Astarion,” you whispered into the dark.

“Yes, my dear," he said softly. "That it is."

#astarion#astarion x reader#astarion x mc#bg3#astarion x oc#astarion x tav#astarion x y/n#astarion x you#baldur's gate 3#bg3 fanfic#astarion fanfic#astarion acunin#astarion fanfiction#bg3 fanfiction#bg3 oneshot#bg3 x reader

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flamingos flock from Rajasthan’s Sambhar Salt Lake

The India’s largest inland saline wetlands

📸 Shoot by @meinbhiphotographer

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this Chicago Tribune story:

Thirty million acres of unprotected wetlands across the Upper Midwest, including 1 million acres in Illinois, are at risk of being destroyed largely by industrial agriculture — wetlands that provide nearly $23 billion in annual flood mitigation benefits, according to new research. In the long term, these wetlands could prevent hundreds of billions of dollars of flood damage in the region.

“Wetlands can help mitigate flooding and save our homes. They can help clean our water. They can capture and store carbon. They support hunting and recreation, and they support the commercial fishing industry by providing habitats for the majority of commercially harvested fish and shellfish,” said study author Stacy Woods, research director for the Food and Environment program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nationwide nonprofit science advocacy organization.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court stripped protections from freshwater and inland wetlands in its Sackett v. EPA ruling, allowing private property development in wetland areas that don’t have a “continuous surface connection” to permanent bodies of water.

But environmentalists say wetlands are rarely truly “isolated” from a watershed, no matter how inland they may be. Some experts worry that after President-elect Donald Trump takes office, he might roll back President Joe Biden’s effort to counter the Supreme Court ruling by expanding federal regulations of small bodies of water and wetlands under the Clean Water Act. Undoing those protections would leave control of wetlands up to the states, some of which — like Illinois — have no strong safeguards in place.

Half of the nation’s wetlands have disappeared since the 1780s, and urban development and agriculture in Illinois have destroyed as much as 90% of its original marshy, swampy land. Nowadays, its wetlands are vastly outnumbered by the 26.3 million acres of farmland that cover almost three-fourths of the state.

While urban and rural development and climate change disturbances contribute to the problem, the expansion of large-scale agriculture poses the biggest threat to wetlands, according to the study. Advocates see an opportunity in the next farm bill in Congress to support and encourage farmers to protect wetlands on their property.

A wetland is a natural sponge, said Paul Botts, president and executive director of The Wetlands Initiative, a Chicago-based nonprofit that designs, restores and creates wetlands.

By absorbing water from storms and flooding, wetlands can effectively reduce the risks and destructive effects of these disasters, which are intensifying and becoming more frequent because of a changing climate. Previous research estimated that 1 acre of lost wetland can cost $745 in annual flood damage to residential properties, an amount that taxpayers fund through local, state or federal assistance programs.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beaver-folk as ruthless empire-builders. They sail, or simply swim, up-river and build dams and crannogs from where they rule rivers, lakes and wetlands for miles into the interior. Their mass use of wood, both for construction and food, often devastates forests (especially in places where the forests are not evolved to deal with beaver habits, with slow-growing trees or those that die after barking) and they shape the course of rivers at their discretion, flooding entire areas if needed. The chiefdoms of the beaver-folk often use their dams and water supply to exhert control over the populations they rule over as tributaries, especially as they are very skilled with iron weapons; what serves for woodworking also serves as a weapon. As they eat mostly wood and hardy plants, they don't have agriculture as such, though they do cultivate gardens on their dams for several delicacies. However, they know that inlanders need water for irrigation, and as they hold whole rivers as lordships, they have power over them, extracting tribute that the most powerful clans display proudly on their crannogs. While not all beaver-folk clans are this aggressive and indeed many live in small crannogs over carefully tended wetlands, when people see countless barked trees dying and smoke rising from the river, they know things are about to change in their side of the woods.

(yes, this is partly inspired on the beavers on Tierra del Fuego)

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe I’m looking in the wrong places (I’m sure I am) but I just want to know what geography is generally like around swamps, not in them (I know that already). No matter how I phrase it I’m not getting any results though :/

Like are swamps really just like marshes with trees, in that they’re off a body of water? Is that the only distinction? Can they be fully inland? Can rivers go through them or do they spread out until they’re just wetland? I HAVE SOME DUMB QUESTIONS AND I CAN’T FIND THE ANSWER

#ugh I should be doing this when I’m less sleepy#but I wanna knowwww#I’m trying to figure out what swamp’s Hyrule looks liiiiiiiike#gah#rambles from the floor

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The marsh acts as a natural and hugely effective bulwark against flooding, absorbing and slowing tides before they can encroach inland. Even last winter — the wettest anyone in the area could remember — the village at one edge of the peninsula did not flood. Paths through the marsh remained passable. A steep bank, covered with grass and significantly higher than the old flood wall, now borders the river. The area is also a haven for wildlife. Bird-watching blinds with giant windows offer glimpses of godwits, plovers, oystercatchers, egrets and herons. A growing population of avocets — black-and-white wading birds with distinctive, curling beaks — has gathered around the pools of brackish water. And the marsh has, over time, become a source of pride to the local population. Mr. Darch, who spent much of his career as a poultry farmer, started grazing cattle there in 2019, at the invitation of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust. It is not without complications: This year, Mr. Darch found himself watching the sky nervously, wondering when the weather would be dry enough to move his cattle back onto their pastures. If the ground is too damp, he explained, it might create health problems in the cows’ hooves. “They like to have nice dry feet,” he said. But the rewards are plentiful. On the marsh, the cattle are not corralled by fences; instead, their movements are governed by digital collars, which play music to discourage them from drifting into certain areas. Their diets are varied and organic, meaning they provide high-quality, free-range meat. The meat’s traceable origin strengthens the bond between farmers and consumers, Mr. Darch said. Often, he noted, “there is a disconnect there, between our food and where it comes from.” He and two colleagues set up a company, Blue Carbon Farming, in an attempt to bridge that divide. The cows provide other benefits, too. “Cows are natural eco-engineers,” Mr. Darch said. “They eat the grass but don’t take it right down, as sheep would. That means the grass grows longer, which provides more cover for wildlife.”

22 October 2024

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Limassol Salt Lake is the largest inland body of water on the island of Cyprus, covering 4.11 square miles (10.65 sq km). Since its deepest point is only about three feet (one meter), it frequent dries and refills, causing its appearance to vary from the Overview perspective. It is considered one of the eastern Mediterranean region’s most important wetlands, providing a seasonal habitat for thousands of greater flamingos.

34.612819°, 32.964386°

Source imagery: Google Timelapse

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parc Natural del Delta de l'Ebre (Terres de l'Ebre, Catalonia). Photos by Miguel Ángel Álvarez and Ferran Aguilar in El Temps.

The river Ebro's delta is one of the biggest wetland areas in the Western Mediterranean. Since 2013, it's declared Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO.

This landscape is characterized by its flat surface covered in rice fields, reed beds, sandy beaches and lagoons formed when the sweet river water and the salty sea water meet. It's home to a rich diversity of animals, most importantly birds and fish. It's also one of the most popular stopping points for migratory birds in their routes between Africa and Europe.

A river's delta is a changing landscape, and this one doesn't fall short. It changes depending on the season: in winter, the rice fields are all covered by water, and in summer they're all green. But the biggest changes have been due to the river bringing sediment throughout the centuries. The coastline and the river's course have moved a lot, and for this reason the towns in the area have also had to move.

In addition, in recent years the delta has been threatened by extreme weather conditions derived from climate change. Mid-latitude cyclones like the Storm Gloria (2020) and Storm Filomena (2021) have greatly affected the delta because the sea has entered thousands of kilometres inland, destroying some beaches and flooding the rice fields, which effectively kills the rice plants. This was a disaster for the farmer families, especially considering that this is the poorest area of Catalonia and farmers are particularly affected by poverty.

#delta de l'ebre#parc natural del delta de l'ebre#catalunya#fotografia#natura#catalonia#landscape#delta#nature#nature photography#travel#europe#mediterranean#flamingo#wildlife#birdwatching#natural park#river#sea

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On the basis of monitored natural inland wetlands (including peatlands, marshes, swamps, lakes, rivers and pools, among others), 35% of wetland area was lost between 1970 and 2015, at a rate three times faster than that of forests.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Many Facets of Söderfjärden

More than half a billion years ago, a meteorite struck Earth near the Antarctic Circle, leaving a divot several kilometers in diameter. In the hundreds of millions of years that followed, the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates brought that cratered piece of crust far into the Northern Hemisphere.

Today, the Söderfjärden impact crater occupies a 22 square-kilometer piece of coastal real estate in western Finland near the Gulf of Bothnia, the Baltic Sea’s northern arm. The OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) on Landsat 9 acquired this image of the hexagonal-shaped crater in September 2024. The feature stretches more than 5.5 kilometers (3.4 miles) from east to west and is divided into many agricultural fields.

In its Scandinavian locale, however, Söderfjärden has not always been on dry land. During the Last Glacial Maximum, around 20,000 years ago, a thick, heavy sheet of ice covered the area and pressed the land down hundreds of meters. Now free of that weight, the land has been bouncing back with some of the highest rates of uplift, or glacial isostatic adjustment, on Earth. New ground emerges from the sea every year.

It’s only in recent centuries that the crater began to appear from beneath the water. It first manifested as a bay (Söderfjärden translates to “south bay”) where people reportedly fished for pike and perch until the 18th century. As the land continued to rise, the crater got progressively drier and eventually transitioned into a wetland area and then an inland depression.

At first, sedges and reeds thrived in the boggy ground, and people would harvest the vegetation for livestock feed. In the early 19th century, pumps were installed to drain Söderfjärden and increase its cultivatable area. Hay barns then proliferated across the crater, peaking at 3,000 in the 1940s and 1950s, according to the Söderfjärden visitor center.

Today, most of the land is used to grow cereal crops such as barley, wheat, and oats. The fields are also valuable to various bird species and famously attract thousands of common cranes during their spring and autumn migrations. Still low-lying ground, the crater continues to be pumped of water.

Söderfjärden interests planetary scientists because of its geometric shape. Some have described the Finnish crater as “the best sample of a hexagonal impact structure on Earth.” Polygonal impact craters, defined as having straight sections along their rims, are a relatively small subset of all impact structures, which tend to be circular. Nonetheless, polygonal impact craters mark the surface of planets, asteroids, and moons throughout our solar system—from Mercury to Pluto’s moon Charon. Instruments on NASA’s Voyager 2, Cassini, MESSENGER, and other spacecraft have imaged many such craters on objects in our solar system.

Scientists believe polygonal impact craters are shaped by underlying geology and that their straight segments form where structures such as faults or other fractures already exist. As a result, the shapes can provide evidence of the geologic past of planets and moons that might otherwise be hidden from view.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Photo by Timo Kyttä. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 11-Sodor Blues

Day 11-Fauna

Other Stories

Other Days

“Welcome back to Preservation and Conservation. Today we are in for a special treat, the Sodor Blue. The sheep on the island of Sodor, off the coast of Barrow in Furness, are a unique breed.”

“Screw off you wooly…”

Henry continued over the mogul’s yelling, “As cattle were rare in the island until the later half of the 18th century, the people of the island relied upon their flocks of sheep for their meat, milk, and wool. Their careful breeding resulted in the Sudrian Blue.”

“Off of the line, you worthless walking rugs!” James swore.

“With the establishment of harbors, and later rail lines on the Island beginning in the mid-1800s, the island began exporting the wool and meat to mainland Britain and Ireland.”

“Move!”

“The meat quickly became prized for its savory flavor, and the wool for its strength, but with the construction of railways and harbors,much of Sodor’s natural wetlands and marshes were drained. This provided pastures fit for cattle, and the breed began to dwindle as competition from the cattle farms threatened the traditional farmers of Sodor’s hills.”

“I assured you, there's no lack of the wooly devils!”

“Relief would come from an unexpected source. Sodor's canal network.”

“Then throw them in it! They're fat enough to float.”

“Established in the 1700s, Sodor's canal network ran through the southern reaches of the island, branching off of and connecting the rivers of Els, Reagh, Maura, Hawin Ab, Hawin Croka and the River Hoo. The main form of transportation in the Southern region of the island prior to the introduction of the railways, the Canals were, and are seen as a cornerstone of Sudrian culture and identity.”

“Did you just sneeze on my paint?! You miserable walking rag! I shoul…”

“Many Sudrians made their livings on the canals, transporting slate, wools, mutton, fish, and more from the coastal cities to the farms inland and back.”

“They’ll have more wool and mutton than they can carry if these sheep don't get out of my way!”

“In a glimpse of the future of Britain's canal network, many lived on their boats, spending their lives crossing the island slowly, taking days or weeks to complete a circuit of the network.”

“That's still a far sight faster than these…”

“They were then understandably dismayed, when large amounts of cow dung were washed into the canals with each rain, which given Sodor's placement within the British Islands, was a far too common occurrence.”

“…Ew.” James scrunched his nose in disgust.

“In 1873 the Canals approached the Sudrian Council with their complaints toward the cattle farms. And in August of that year the council convened to hear the case. The men chosen to represent the canals focused their arguments on the effects of the dung being swept into the canal and flowing downstream toward the coastal towns. Affecting the air and drinking water for not only those who lived on, but along the canals and rivers. The farm owners, largely businessmen from the mainland, argued the canals were obsolete and would soon be replaced by the railways anyway.”

“I see businessmen haven't changed since then,” James muttered, wheeshing away a sheep who was getting too close.

“Perhaps unsurprisingly, the council sided with the canals, and banned the farms from grazing their cattle within a mile of the canals and rivers of the island, restricting the cattle farms to small pockets across the island. Most of the cattlemen left the island, some abandoning their herds on the island. Some of the former sheep farmers came together, and formed dairy farms with the abandoned herds. The abandoned fields along the canals and rivers soon were filled with villages and towns as Sodor’s population boomed with the arrival of industry. The sheep farms grew once more as Sodor turned back to them for meat and wool.”

“...if you bite my buffers I will bump you.”

“Time went on and the world changed around them, leading to the sheep getting into trouble. Sheep are highly intelligent animals…”

“Are they??”

“...and are highly prone to escaping their pens. In the old days, this merely meant finding their way into the next field or forest. Today it means causing havoc for the local roads and railways.”

“You don't say.”

“Nonetheless the escapes are largely harmless, if frustrating, and life for the Sodor Blue has changed little since the inception of the breed.”

“MOVE!!”

#ttte fanfic#rws fanfic#fanfic#Traintober#Traintober24#Traintober2024#ttte james#ttte henry#Prompt-Fauna

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there anything about your new location (the terrain, the local culture, the physical sites, etc) that has given you a new perspective on regional events of the War of 1812?

This a wonderful ask, thank you! I have been mulling over how to answer it all day! This ended up getting so long I put it behind a cut (I HAVE A LOT OF FEELINGS ABOUT THIS).

The Maumee River, as seen from Fort Meigs Historic Site.

One thing new in my life is a heightened awareness of important rivers facilitating the movement of trade, supplies, and settlement. Particularly in the Old Northwest/current Midwest of the USA: regions that I grew up perceiving as a land-locked "flyover country."

Like, to give one example, I had a vague idea that there was a city called Fort Wayne, Indiana, but I thought it was just in the middle of a cornfield for no reason(?). But actually it's at the confluence of the St. Joseph, St. Marys, and Maumee Rivers, leading to the Great Lakes! The strategically important location is why General Anthony Wayne—that guy again—built the original fortification in 1794. I am downriver of all of this, connected to many inland waterways.

I also have a keen sense of living in the Great Black Swamp, despite how dramatically the land has been transformed by deforestation and drainage. There are the terrifying drainage ditches everywhere (the locals seem less perturbed by them), and many other signs of the natural state of the terrain—the swamp is just barely at bay. My coworkers have said "Black Swamp" unprompted in our conversations; I've seen it mentioned in local Facebook groups talking about the need for back-up sump pumps. The idea that people of northwest Ohio have no sense of history and are unaware of the Great Black Swamp isn't true at all.

I look at the pools of water that form in every hollow and think of the words of Alfred Lorrain, marching to Fort Meigs:

We had frequently to pass through what was called, in the provincialism of the frontiers, "swales"—standing ponds—through which the troops and packhorses which had preceded us had made a trail of shattered ice. Those swales were often a quarter of a mile long. They were, moreover, very unequal in their soundings. In common they were not more than half-leg deep; but sometimes, at a moment when we were not expecting it, we suddenly sank down to our cartridge-boxes.

Swale is a new word in my vocabulary, and now I see them everywhere!

Culturally, I think there is a great appreciation of history here: a very positive difference from the Chicagoland area. Even if the average local is probably not deeply into it, they have a consciousness of major historical events that have shaped their region and take pride in it. It's a lot more like New England that way.

Because of my focus on the War of 1812, I notice the absence of Indigenous people and voices—absent from historical accounts and from the demographics of Perrysburg and its environs today. I can't single out Ohio as being a uniquely violent settler-colonial state when this is ALL of the United States; but it hits different when I have this much greater familiarity with who was forcibly removed from this land, and how. The same US military leaders who fought in the War of 1812 were behind the (very much related) campaign for the removal of Native Americans from newly acquired territories, including the infamous Trail of Tears.

Once again, it's probably hypocritical for me to notice this so much, when I literally grew up on Wampanoag land where King Philip's War was fought, but here I am. Suddenly aware of General Wayne's name on everything, etc.

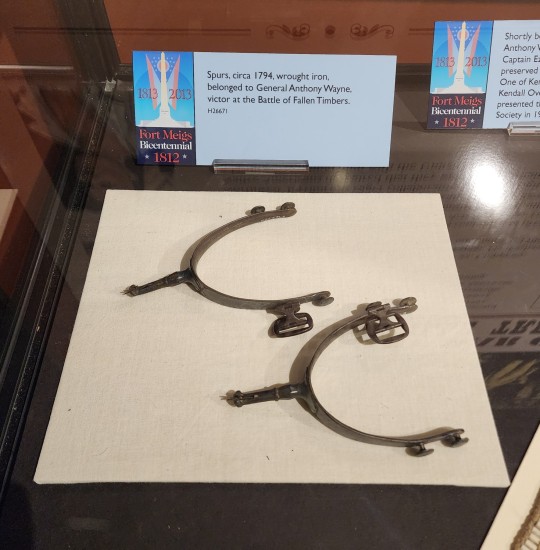

General Wayne's spurs in the Fort Meigs Museum. Not pictured: the can of Maumee Bay Brewing Co. Fallen Timbers Ale that I am currently drinking.

I haven't had the chance to explore physical sites with historical significance beyond Fort Meigs and Fallen Timbers. I know I will get to the ruins of Fort Miamis soon, and I really want to explore a lot of wetlands in local parks and nature preserves (that will double as birdwatching excursions). I am always thinking about what this place looked like 200 years ago, and what I can see today that might still look familiar to a person from that time.

I had a great trip to the National Museum of the Great Lakes today, which is closer than I thought! Local maritime museums are also on my agenda, even if they're not specifically War of 1812-related.

#asks#shaun talks#ohio posting#i could add three or four more paragraphs to any given paragraph here#you activated my trap card

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stewart Boardwalk, BC (No. 5)

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal flat ecosystems are as extensive globally as mangroves, covering at least 127,921 km2 (49,391 sq mi) of the Earth's surface. They are found in sheltered areas such as bays, bayous, lagoons, and estuaries; they are also seen in freshwater lakes and salty lakes (or inland seas) alike, wherein many rivers and creeks end. Mudflats may be viewed geologically as exposed layers of bay mud, resulting from deposition of estuarine silts, clays and aquatic animal detritus. Most of the sediment within a mudflat is within the intertidal zone, and thus the flat is submerged and exposed approximately twice daily.

Source: Wikipedia

#tidal flats#Estuary Boardwalk#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#clouds#nature#Canada#summer 2023#fir#the North#cityscape#landscape#forest#woods#flora#food#Stewart#Kitimat–Stikine#British Columbia#small town#countryside#tide flats#Stewart Boardwalk#Portland Canal#Portland Inlet#Pacific Ocean#mountains

37 notes

·

View notes

Video

Avocet- West Sussex by Adam Swaine Via Flickr: Birds of shallow coastal lagoons, estuaries and increasingly inland wetlands, you can find these unmistakeable black and white waders at any of the Wildlife Trusts sites listed below, including the UK’s first successful inland breeding avocets in land-locked Worcestershire. yYou can see avocets in West Sussex in winter, especially at Medmerry Nature Reserve: this 1 is at WWT Arundel

#avocets#Waders#RSPB#wwt#wetlands#arundel#West Sussex#sussex#walks#waterside#water birds#nature lovers#nature#nature watcher#nature reserve#england#english#english birds#uk#uk counties#counties#beautiful#wildlife#wild#WINTER#Adam Swaine#fuji#2024#british birds#british

5 notes

·

View notes