#inalienable possession

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Earlier today I was just about to start eating and thought to myself in Swedish:

det vattnas i munnen på mig.

literally: "it is being watered in the mouth on me" "my mouth is watering"

And the more I think about it the more interesting this sentence is. Literally translated to English it sounds incredibly weird.

the "body part ON owner of body part" construction to express "owner's body part" since the mouth is inalienably possessed by me. That is, "my mouth" is often expressed as "munnen på mig", while normal possession is instead expressed simlilarly as in English, eg "my horse" = "min häst". This is a distinction common in Germanic languages that English has lost.

det (= it) should probably be analysed as an expletive "dummy" subject similar to it in "it is raining"?

the -s ending of vattna (= to water) often indicates passive or impersonal constructions. Not sure how to view it here. The mouth is caused to produce water, or something impersonal is producing water in the mouth.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i alternate between more worldbuilding and more conlang heavy phases and whenever i enter back into a conlanging phase the autism just kicks into overdrive its all i can think about i already have so many ideas. i was thinking word order could start out as VSO. then S/O verb agreement evolves thru pronouns becoming suffixes. the subject now gets fronted, > SVO. one daughter language could then evolve topic marking, fronting the object when it's the topic, > OSV. now in sentences where the S is the topic the O retains its position before the verb, > SOV, the new default. maybe this change could also trigger prepositions to become postpositions. no idea how naturalistic this would be but its an idea

#and then if at an earlier stage some prepositions evolved into case prefixes#id have prefixes and postpositions.......nice#regarding case i was thinking: “at” would become accusative and locative#“to” dative and allative and alienable possession#“with” comitative and inalienable possession#and a topic marker could evolve from “for” maybe?#ramblings#oh GOD i just remembered verbs. shudder#not thinking about that yet#actually its not that bad

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is it purely pragmatic? So for example, when you want to talk about beskar’gam in general/as a collective (eg “beskar’gam is worn over a kute”), you have to use the plural beskar’game? Mando’a in general seems to be rather aggressively regular with its plurals, to the point that they have a singular word for a brain cell (mirsh), and a brain is a plural of that (mirshe). Like what language does that? Collectives seem also to be formed by pluralising, so I think that would fit.

What about syntax? Are there any grammatical differences for how Mando’a handles alienable/inalienable possessions? There are three ways to form possessives in Mando’a: Boba’s sabre could be kad be’Boba, Boba’kad, or Bobab kad. Do alienable and inalienable possessions have different patterns in regards to which constructions they use? For example, inalienable possessions (like beskar’gam) can only use one pattern, while alienable possessions can use all? Or or something else?

Are there any other words that behave differently because they’re inalienable possessions? For example, there are some Polynesian languages that have two different forms of possessives, so you’d use the inalienable form for your birth home village and the alienable form for your current home village.

It’s a real bummer that Mando’a isn’t super fleshed out with, like, different classes of nouns because it would be super neat to use the LANGUAGE to represent the ideology/concept of armor and weapons as a part of a Mandalorian. In one language (which of course reflects culture), horses are INalienable, but wives are alienable. Wives don’t need to belong to anyone, but a horse is like an arm or a leg; it will always be part of someone. I can imagine Mando’a having a similar function with armor/weapons because those are a part of a more traditionally-minded Mando’s self.

It would also be really neat to do this because then there would be not just loss/denial of culture when the New Mandalorians took over but they might try to change the language to conform to their ideology by separating armor and weapons from a Mando individual. This could create/be an aspect of a dialect (admittedly, it’s a very small change, but I could see it happening with a lot of other elements as well) between different sects of Mandalorians.

Imagine how weird it would be if someone said something like “the leg got hurt in that game.”* Most people would say “whose leg?” because legs don’t just wander around getting hurt in games on their own, and there’s no way it doesn’t belong to someone. But in this hypothetical Mando’a, Mandalorians think of their armor in the same way. Armor doesn’t exist on its own. It can’t, within their concept of language and the world. So if the New Mandalorian’s tried to change this concept, they would be disrupting cultural and linguistic assumptions. (Would they think to do this at all? I argue they might, because linguistic change has historically occurred following social change; on a small scale, think of the expansion and contraction of the usage of “they.” On a larger one, think of the movement in Spanish to use the gender-neutral marker -e.)

I don’t know, man, I’m guess I’m just bummed that Mando’a (given how many people have the ability to contribute to it) doesn’t have the linguistic complexity of, say, Quenya (WHICH YES IS A HIGH BAR THAT’S WHY I SAID GIVEN HOW MANY PEOPLE CONTRIBUTE TO IT), so that we can make extremely detailed metas and linguistic analyses of it.

*also think of how we say “I hurt my leg,” even if the injury isn’t your fault

#mando’a#meta: mandalorians#mandalorian culture#mando’a language#conlang#mandoa#beskar’gam#possessive#possession#inalienable possession#ranah talks mando’a#mando’a linguistics#mando’a syntax

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

bedtime

NOTE: stä'noli should be stolä'ni, that was a pretty rudimentary mistake and I'm not really sure what was going on in my brain when I wrote it but 😅 maybe i'll fix it on the image later but i can't be bothered right this minute, i'm already up way later than I should be as is (have an early day tomorrow)

Further language notes/rambling under the cut!

"wait, isn't Jake supposed to be spelled Tsyeyk in Na'vi?" Yes it is! And if I'd given that line to a monolingual Na'vi speaker I would've spelled it that way. BUT Neytiri is bilingual and does not pronounce it "Tsyeyk" (I mean, technically she doesn't say "Jake" either, it's more like "Zheyk" but w/e). So for her specifically I keep the j. I suppose at that point I could've just kept the English spelling completely, but leaving silent letters at the end like that makes things weird in written Na'vi given all the grammatical endings that can be applied (not that that matters in this comic because they weren't needed for the line but ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ )

Speaking of Jake, writing Na'vi dialogue for him is fun to me because he's not a native speaker which means I'm free to give him all sorts of beginner habits and/or mistakes, especially given that by his own admission he struggled learning the language. However, since I'm working within a pretty broad time frame, I had to remind myself that he wouldn't be a beginner forever.

I bring this up because there are two aspects of Jake's dialogue here that I was going to point out as...well, not wrong, but as more "English-y" habits I'd headcanoned he might hang on to...but on further reflection changed my mind because I realized that at the time of this comic he's been living with the Omatikaya for nearly ten years and would be pretty much fluent. I still left it written that way but am no longer headcanoning that that's ~just how he talks~ at this point in his life. After all, if I'm conscious of these habits after just two years of studying the language as a casual hobby, is it really believable that he'd be clinging to them after nearly a decade of full daily immersion, even with his self-admitted struggle with language learning? 😅

Anyways, for the sake of rambling about my hobby regardless, one of these aspects was using SVO word order, like English. Na'vi is a free-word-order language, so SVO is valid, but most Na'vi speakers are not going to stick to it exclusively. I think Jake, like many native-English-speaking learners, may have relied on this word order earlier on because that's just how his brain has been wired to process information, but at this point I think just by sheer exposure he'd have broken out of any strict adherence to it, intentional or otherwise.

The other thing is concerning possessive. The standard Na'vi grammatical ending for possessive is -yä. But Na'vi grammar also includes a concept called inalienable possession, which refers to things that are intrinsically yours and cannot be given away. What exactly qualifies as inalienable varies between languages that have such a concept, but with Na'vi it's most commonly seen with body parts. Inalienable possession can be marked with -yä, but there is a slight preference to mark it with the topical, -ri, instead. So, compare:

Peyä mehinam lu ngim. His legs are long. Pori mehinam lu ngim. His legs are long (lit. "concerning him, the legs are long")

Both of these are considered acceptable, but the -ri version is considered just slightly "better" (for lack of a better term).

You'll notice that Jake uses peyä instead of pori here; this was because the peyä structure is a more direct equivalent to the English construction, so it's pretty common for new learners to use it instead of -ri. And again it's not wrong, so it's not exactly a mistake per se. So it seemed like a reasonable "Englishy-but-still-technically-correct" habit for Jake to hang on to. And I do still think that may well have been in the case...in his earlier years 😅

soooo yeah. I will still probably be giving Jake some of those speaking habits in comics and such that take place only 2-3 years after A1, but once you get to around 10 years like this one...yeah I think it'll make more sense to just write his dialogue like that of any other fluent Na'vi-speaking character lol

#avatar#avatar 2#sully family#jake sully#neytiri#tuktirey#neteyam#kiri#lo'ak#comic#my art#lì'fya leNa'vi

463 notes

·

View notes

Text

To sit in the comfort and safety of the West and condemn acts of armed resistance that the Palestinians choose to carry out – always at great risk to their lives – is a deeply chauvinistic position. It must be stated plainly: it is not the place of those who choose to stand in solidarity with the Palestinians from afar to then try and dictate how they should wage the anti-colonial struggle that, as Frantz Fanon believed, is necessary to maintain their humanity and dignity, and ultimately to achieve their liberation. Those who are not under brutal military occupation or refugees from ethnic cleansing have no right to judge the manner in which those who are choose to confront their colonisers. Indeed, expressing solidarity with the Palestinian cause is ultimately meaningless if that support dissipates the moment that the Palestinians resist their oppression with anything more than rocks and can no longer be portrayed as courageous, photogenic, but ultimately powerless, victims. [...]

As a result, large swathes of the Western left express solidarity with the Palestinian cause in a generalised, abstract way, overstating the importance of their own role, and simultaneously rejecting the very groups who are currently fighting – and dying – for it. All too often, those who have refused to surrender and steadfastly resisted at great cost, are condemned by people who, in the same breath, declare solidarity with the cause. Similarly, it is common for these same people to either ignore or demonise those external forces that materially aid the Palestinian resistance more than any others – most notably Iran. If this assistance is acknowledged, which is rare, the Palestinian groups that accept it are typically infantilised as mere ‘dupes’ or ‘pawns’, for allowing themselves to be used cynically by the self-serving acts of others – a sentiment that directly contradicts Palestinian leaders’ own statements.

A specific criticism of Hamas that is frequently deployed in this context is the ‘indiscriminate’ nature of its missile launches from Gaza, actions which both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International regularly label ‘war crimes’. As observed by Perugini and Gordon, the false equivalence that this designation relies upon ‘essentially says that using homemade missiles – there isn’t much else available to people living under permanent siege – is a war crime. In other words, Palestinian armed groups are criminalised for their technological inferiority’. After the latest round of fighting in May 2021, al-Sinwar stated clearly that, unlike Israel, ‘which possesses a complete arsenal of weaponry, state-of-the-art equipment and aircraft’ and ‘bombs our children and women, on purpose’, if Hamas possessed ‘the capabilities to launch precision missiles that targeted military targets, we wouldn’t have used the rockets that we did. We are forced to defend our people with what we have, and this is what we have’.

This failure to support legitimate armed struggle is a part of a wider problem with the framing used by many supporters of the Palestinian cause in the West, that obscures its fundamental nature and how it must be resolved. Palestine is not simply a human rights issue, or even just a question of apartheid, but rather an anti-colonial fight for national liberation being waged by an indigenous resistance against the forces of an imperialist-backed settler colony. Decolonisation is a word now frequently used in the West in an abstract sense or in relation to curricula, institutions and public art, but rarely anymore in connection to what actually matters most: land. And that is the very crux of the issue: the land of Palestine must be decolonised, its Zionist colonisers deposed, their racist structures and barriers – both physical and political – dismantled, and all Palestinian refugees given the right of return.

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, “Evil” doesn’t “loves only Itself” in Tolkien lore

One quote in particular that gets thrown around a lot when discussing Sauron x Galadriel is “evil loves only itself” because Charlie Vickers mentioned it in one of his interviews. The “Rings of Power” fandom atributes this to Tolkien. But is it really?

This quote is not from Tolkien. Nor Charlie ever said it was, he refers the correct author on his interview, so I don’t know why folks keep taking his words out of context.

He [Sauron] offers to make her [Galadriel] his queen. Is that a marriage proposal?

That’s something I thought about a lot, but I don’t think so. W.H. Auden wrote an essay on Tolkien, and he said something along the lines of, “Evil loves only itself.” [“Evil, defiantly chosen, can no longer imagine anything but itself.”] So I think in his pitch to Galadriel, it cannot mean that he loves her or that there’s any kind of romantic relationship. There should be no ambiguity around the fact that Sauron is evil — he’s terrible, and he’s using Galadriel to enhance his power.

Now, what Charlie is doing here is trolling. Because he knows Tolkien letters, and has studied them as preparation for his role as Sauron. This fact is mentioned in this very interview: you once mentioned that you found useful things in Tolkien’s letters, although you didn’t specify which ones.

And so, Charlie is perfectly aware that “evil loves only itself” was written by W.H. Auden on his essay about the nature of Good and Evil, when reviewing “Return of the Ring”, in 1956. And he’s also perfectly aware that Tolkien didn’t subscribe to this way of thinking, at all.

Tolkien Letter 183 is the reply to Auden’s essay and his wild takes of “evil loves only itself”. In this letter, Tolkien not only disagrees with Auden’s views of his work, but denies them, entirely:

There are also conflicts about important things or ideas. In such cases I am more impressed by the extreme importance of being on the right side, than I am disturbed by the revelation of the jungle of confused motives, private purposes, and individual actions (noble or base) in which the right and the wrong in actual human conflicts are commonly involved. If the conflict really is about things properly called right and wrong, or good and evil, then the rightness or goodness of one side is not proved or established by the claims of either side; it must depend on values and beliefs above and independent of the particular conflict.

A judge must assign right and wrong according to principles which he holds valid in all cases. That being so, the right will remain an inalienable possession of the right side and Justify its cause throughout. (I speak of causes, not of individuals. Of course to a judge whose moral ideas have a religious or philosophical basis, or indeed to anyone not blinded by partisan fanaticism, the rightness of the cause will not justify the actions of its supporters, as individuals, that are morally wicked. But though 'propaganda' may seize on them as proofs that their cause was not in fact 'right', that is not valid. The aggressors are themselves primarily to blame for the evil deeds that proceed from their original violation of justice and the passions that their own wickedness must naturally (by their standards) have been expected to arouse. They at any rate have no right to demand that their victims when assaulted should not demand an eye for an eye or a tooth for a tooth.)

Similarly, good actions by those on the wrong side will not justify their cause. There may be deeds on the wrong side of heroic courage, or some of a higher moral level: deeds of mercy and forbearance. A judge may accord them honour and rejoice to see how some men can rise above the hate and anger of a conflict; even as he may deplore the evil deeds on the right side and be grieved to see how hatred once provoked can drag them down. But this will not alter his judgement as to which side was in the right, nor his assignment of the primary blame for all the evil that followed to the other side.

In my story I do not deal in Absolute Evil. I do not think there is such a thing, since that is Zero. I do not think that at any rate any 'rational being' is wholly evil.

This is Tolkien, very eloquently, telling Auden to f*ck off with his basic and narrow views of Good vs. Evil, because he’s misunderstanding what Tolkien actually wrote on his books. And this was a grievance Tolkien, himself, had:

Some reviewers have called the whole thing simple-minded, just a plain fight between Good and Evil, with all the good just good, and the bad just bad. Pardonable, perhaps (though at least Boromir has been overlooked) in people in a hurry, and with only a fragment to read, and, of course, without the earlier written but unpublished Elvish histories. But the Elves are not wholly good or in the right.

Tolkien Letter 154

Some critics seem determined to represent me as a simple-minded adolescent, inspired with, say, a With-a-Flag-to-Pretoria spirit, and willfully distort what I say in my tale. I have not that spirit, and it does not appear in the story.

Notes on Letter 183 (still about Auden’s essay)

Charlie is very much aware of Tolkien response, and he knows that, in Tolkien legendarium, evil can love and it doesn’t make any less evil, because Tolkien doesn’t deal with absolute evil in his world, nor is Sauron pure evil; as I already talked about in this post.

Why did Charlie say these things, then? Probably to avoid spoiling the story of the show, where Sauron is in love with Galadriel.

#charlie vickers#Sauron#tolkien legendarium#Tolkien lore#saurondriel#haladriel#sauron x galadriel#galadriel x sauron

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the Second Amendment:

“A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

The term “well-regulated” was commonly used before 1789 and continued to be for a century after. It described something being in proper working order, calibrated correctly, and functioning as expected.

The term “militia” refers to all citizens capable of military service. The National Guard did not replace the militia, as clarified by the Militia Act of 1903. The National Guard is the organized militia, while able-bodied men between 17 and 45 are part of the reserve militia. The Militia Act of 1903 repealed the requirement for men to provide their own firearm under the Militia Act of 1792.

The term “to keep and bear” is very easy to understand. “To keep” means to have or possess. “To bear” in this context means to carry and to hold. The phrase very simply means that you can have the item in your possession.

The term “shall not be infringed” means to wrongly limit or restrict. This acts on the previous phrase, “to keep and bear”. The language is clear and concise.

The Second Amendment, in more modern terms, would read like this: “A properly armed people are necessary for a state to be free and safe. American Citizens can have weapons in their possession, and you can't do anything about it.”

Understand this; The US Constitution is a limit on government, not citizens, and our rights don't end where your feelings begin. You have no right to infringe on our inalienable rights.

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

conlanging for my Ice Age Story (truly I understand the Tolkienian impulse to just tinker with the conlang forever rather than write) and having 2 emotions:

Building in an alienable-inalienable possession distinction and the moment when the clan switches from using alienable possessive forms for Kurrat (our guest, our temporary obligation) to inalienable forms (our clanmate, one of our hunters/stoneworkers/firetenders*) will be a deeply emotional one that is not possible to properly convey in English

*“firetender” in this culture is a formal title for adult member of the clan with all the rights and obligations of a full clanmember; it’s a synechdoche for all the duties expected of a member of the clan, but also the trust and responsibility extended to them. It’s basically akin to “citizen” though the concept of citizenship isn’t really a relevant one here in 28,000 BCE. This Ice Age culture places a high symbolic/spiritual/theological importance on life-giving fire, and making sure there is always someone tending the hearth-fire is an important duty to both keep the life-giving spirit live at the heart of the community (if the hearth-fire goes out it is a DIRE omen) but also to y’know make sure everyone doesn’t freeze to death in their sleep. “Firetender” is a relationship term that is obligatorily marked with a plural inalienable possession affix.

2. Current idea is that it ends with a climactic hunting scene…

Someone, maybe Dannágia, comes back to camp breathlessly reporting that he saw a herd of rúrómpazheten. This is the first big animal they’ve encountered pretty much all winter and it’s worth assembling a hunting party to try to go kill one, it could feed us all for the rest of the winter.

Everyone in the clan is clearly concerned and excited and freaking out about the idea. Okay this is a big deal. However. Kurrat has been living with these guys for maybe… two months now? He’s learned how to communicate fairly well, but still encounters vocabulary he’s never heard before. Like this. What the fuck is a rúrómpazhe and why are people reacting like this.

Pendíkhia tries to explain, “it’s an animal. It’s really big, thick hair, it has beriłímetéwan, and a buʕiba… you know.”

“That doesn’t help even slightly.”

“Ugh! You know, long teeth, long nose.” Clearly frustrated, not patient, she points at the bones making up the structure of the hut. “The animal that comes from!”

The hut. The mammoth bone hut.

“A mammoth?” Kurrat says. “You’re planning to go hunt a mammoth? Are you stupid? Do you like getting stomped to death and dying?”

Her response is, basically, are you having fun sitting around slowly starving to death, because you are welcome to keep doing that, but also. She takes time to laugh. Because the word for mammoth in his language, the word he used, was p’ûrrūmf. And Pendíkhia is like. Okay. Aside. Perfect name. Yeah that animal really is a fucking p’ûrrūmf isn’t it.

#Ice Age story#conlang#I am not married to those words for tusks and trunk. But the words for ‘mammoth’ are both deliberate

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

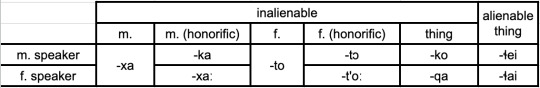

Cardassian conlang (part 1?)

Finally started making my Cardassian conlang and I'm having so much fun already. Get this:

There's a distinction between alienable and inalienable possession, something that occurs in many natural languages. An example is, like, "my nose" vs "my hat". My nose is inalienable because it will always be mine, while my hat is alienable because it can stop being mine. So in languages with this distinction, you'd use different words for "my" in those two situations.

In my Cardassian language, possession is indicated with suffixes attached to nouns and people's names. People are "possessed" in the sense that, y'know, they're your mom or your friend or your orthodontist or whatever. Generally, you'd use the alienable form for people. Your orthodontist might not always be your orthodontist, your friend might not always be your friend. The exception is that you always use the inalienable form(s) for family. Your mom will always be your mom.

So, to use the inalienable possessive for a friend would be to say that they are as close to you as family, that you trust that they will always be your friend. This is often, like, a milestone in dating. To start saying "my girlfriend (inalienable)" marks that your relationship is serious. (Traditionalists will say that you shouldn't use the inalienable form until you're properly betrothed, but kids these days have their own ideas.) In this way, it becomes a pretty straightforward term of endearment (or, rather, grammatical particle of endearment).

Since there's no equivalent in Federation Standard, the translator often renders it as "my dear."

Here's a table of the 10 different words for "my"

So, presuming that the speaker is a man, and the person they're referring to is also a man who they don't have to use the honorific form with...

/alʊk/ - "friend"

/alʊkɬei/ - "my friend"

/alʊkxa/ - "my dear friend"

/ilɨm̥xa/ - "my dear Elim"

#no I don't know what I'm doing but I'm having so much fun hehehe#disclaimer: so much respect to the awesome cardassian conlangs that already exist and the ppl who made them!!#not trying to step on any toes I just thought it'd be fun to make my own :))#these r the first words I've come up with after settling on a phonemic inventory. which was fun in and of itself#THERE R EJECTIVES !!! ISNT THAT COOL !!!!! also no voicing distinction and nasals r usually voiceless#anyways. honorifics r mostly abt age I think. but also social class and rank probably#I like how the casual forms don't distinguish the speaker's gender. reflects that gender differences r more pronounced in formal situations#cardassians#ds9#asit#star trek#elim garak#narcissus's echoes#q's cardassian conlang#lingposting

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 97: OooOooh~~ our possession episode oOooOOoohh 👻

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘OooOooh~~ our possession episode oOooOOoohh 👻'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about possession – using things like “have” and “of” and “apostrophe S” and how different languages do possession differently. But first, next month is our 8th anniversary! We’ve been making Lingthusiasm for eight years with you, and we’re still excited to keep making it.

Lauren: As part of the anniversary celebrations, we’re running the final listener survey in our trilogy of surveys. We have a new set of linguistics experiments for you to do, and we use these surveys to shape topics and ideas for the show.

Gretchen: As one example, we had a really good response to our linguistics advice bonus episode that we did last year, so you can also use this year’s survey to ask us your pressing linguistics advice questions for a potential future advice episode. You can suggest linguistically interesting books for us to read and maybe comment on. We have further refinements on the bouba-kiki experiment, and more!

Lauren: You can hear about the results of the last two years of surveys in bonus episodes that we’ll link to in the show notes. We’ll be sharing the results of the next experiments next year.

Gretchen: We have had ethics board approval from La Trobe University, which is Lauren’s university, for this survey, so we can use the results in linguistics research papers as well. But the ethics board is only for three years, so this is your last chance to be a part of the Lingthusiasm listener survey.

Lauren: If you did the survey in a previous year, first of all, thank you! And secondly, yes, you are still allowed to take it again if you want. There’re new questions.

Gretchen: To do the survey or to read more details about it, go to bit.ly/lingthusiasmsurvey24 – that’s all one word, no spaces, no capitals or anything.

Lauren: Or you can follow the links from our website and social media.

Gretchen: Our most recent bonus episode was all about communicating with aliens. We discussed how alien languages might work, how we might try and make sense of them based on how existing human and animal communication systems work, and how we would plan to pack enough batteries for xenolinguistic fieldwork.

Lauren: Go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to the xenolinguistics episode – and way more bonus episodes – and to help keep the show running ad-free.

[Music]

Lauren: On today’s episode, we’ll be discussing –

Gretchen: Ooh, can I say it in my witch voice?

Lauren: Yes, you can say this in your witch voice.

Gretchen: [Witch voice] “Eye of newt and toe of frog, / Wool of bat and tongue of dog, / Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting, / Lizard’s leg and owlet’s wing, / For a charm of powerful trouble, / Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.”

Lauren: [Laughs] Those lines come from Shakespeare’s play Macbeth, particularly the witches who feature in Macbeth. And not only is it scene-settingly spooky, but it is doing something important grammatically for this episode.

Gretchen: So, “eye of newt and lizard’s leg” are both – one of these constructions has an “of” in it, “eye OF newt,” and the other one has the “apostrophe S,” “LIZARD’S leg.” These are two constructions that are both doing a similar thing grammatically. They’re indicating this relationship between these two things – the newt and the eye, and the lizard and the leg.

Lauren: We can have different constructions doing the same thing. This thing is about a relationship between two entities. “Eye of newt” or “lizard’s leg” is a part-whole relationship where the eye is part of the newt.

Gretchen: But then there’s also “charm of powerful trouble,” which is not the same relationship as the eye of the newt. It’s not that the trouble has a charm. In this case, it’s using the same “of” to be part of the description.

Lauren: There’re a whole host of other possible relationships that can be expressed by “of” or “apostrophe S.”

Gretchen: We could talk about the “witch’s spellbook.”

Lauren: Is that the spellbook that the witch owns or is she the author of the spellbook?

Gretchen: This is one of the things about something like a book – is this my book that I wrote or my book that I just happen to be reading right now?

Lauren: One is a purchase or ownership relationship, and one is one of the ownership of the ideas rather than physical possession.

Gretchen: You can also have interpersonal relationships – the “wizard’s apprentice,” “my apprentice,” “my mentor.”

Lauren: I like that with these sometimes the interpersonal relationships are equal. If you’re my friend, then I’m your friend. And some of them have asymmetrical relationships. The mentor has an apprentice.

Gretchen: Or something like “the witch’s cat,” “the witch’s familiar,” or maybe “the cat’s witch,” depending on whether you’re taking the point of view of the cat.

Lauren: I guess when it comes to – I mean, with cats in particular it’s quite difficult, but when it comes to, say, pets, there’s a reciprocal relationship, but there is an assumption of ownership on behalf of the pet owner.

Gretchen: But sometimes, you know, people refer to themselves as being their cat’s “parents” or their cat’s “humans” and stuff as well.

Lauren: Yeah, I’m sure there’re plenty of cats that don’t feel like they are owned by anyone.

Gretchen: Particularly cats. Something like “the school of magic” – the magic isn’t even aware of owning the school. It’s just an association of a school with magic.

Lauren: Or “the colour of the toadstool” – it’s about the characteristic.

Gretchen: Or something like, “the cauldron of silver” – the cauldron is made out of silver – “a vial of poison” – the poison is contained in the vial.

Lauren: The vial is not made of poison. “The cauldron of silver” and “the vial of poison” have different relationships there.

Gretchen: One that I really like is constructions like, “tomorrow’s weather,” because it’s really clear that that’s just weather that has an association with tomorrow. It’s not that tomorrow somehow possesses the weather because these are both abstract concepts, and what would that even mean.

Lauren: Yeah, or just a kind of general relationship of proximity. Like, “the demon of the night” is not owned by the night. You can’t really say, “the night’s demon,” or “Zelda’s legend.”

Gretchen: Do you mean Legend of Zelda, like the video game?

Lauren: Yeah, I do.

Gretchen: I think “demon of the knight” works in this ownership relationship if it’s “K-N-I-G-H-T.”

Lauren: Oh, yes.

Gretchen: And they’re, like, best buds or, you know, enemies to lovers 20,000 words.

Lauren: Whole different genre.

Gretchen: A whole different genre than the “demon of the K-N-I-G-H-T,” which is a demon that goes [ghost noise] on the knight.

Lauren: Something like “the philosopher’s stone” or “Dracula’s castle” where it’s sometimes about ownership or just attribution. I mean, Dracula definitely didn’t build the castle. Maybe Dracula did build the castle himself. Maybe he’s a multi-skilled vampire.

Gretchen: I think with “the philosopher’s stone,” there’s this idea that the philosopher or the alchemist was the one who created the stone, but then people have been trying to find the philosopher’s stone and take it for themselves as well.

Lauren: And Frankenstein definitely created “Frankenstein’s monster.” That’s the whole premise of the book.

Gretchen: That’s very true, yes. And then you have these very abstract relationships – something like “the haunting of the house” or “the house’s haunting,” again, this is a relationship between these two nouns, but it’s not clear that the haunting belongs to the house, or the house belongs to the haunting – whichever way you put it.

Lauren: I also like that sometimes the thing that is being possessed can just be left in context. If you had a witch named “Griselda” who opened up a café, you could just call it “Griselda’s.”

Gretchen: And even if you did call it something more fanciful, people who know you and know that it’s your café might still call it “Griselda’s” – “Griselda’s café,” “Griselda’s house,” “Oh, I’m going over to Griselda’s this evening” – and in context you know what that means.

Lauren: Sometimes, it’s about location, so “Count von Count of Sesame Street.” He is not possessed by Sesame Street; it’s just his location.

Gretchen: “The ghost of Christmas Past” is associated with Christmas Past. I dunno really if “possessed by” or “located in” quite works.

Lauren: “Wicked Witch of the West” – another one of those.

Gretchen: Yeah. I think “located in the west.”

Lauren: We have all of these different relationships that are marked using the same grammatical form, but the relationships can be quite different. It’s not necessarily about ownership or power necessarily.

Gretchen: Yeah, in fact, there was one statistical investigation of this type of relationship to see how many times is it used to represent like, “I own something. This is my cup,” and how many times is it used to represent other types of relationships or associations between words. In this study from 1940, by someone named Fries, found that it was only about 40% that were actually something like “my cup,” where I could be argued to own the cup. Sixty percent of these uses were something like, “tomorrow’s weather,” or “the haunting of the house,” where there really isn’t straightforwardly a possessive or ownership relationship. Yet, that being said, grammatically speaking, people often still use the word “possessive” or sometimes the term “genitive” to refer to this whole category of relationships even though the majority of them don’t necessarily express possession.

Lauren: We’re talking about grammatical possession not spiritual possession, but I’m determined to see how many haunted and spooky examples we can fit into this episode.

Gretchen: They do have a common origin – the idea that maybe an evil spirit might be in possession of your body. They’re almost as old – they’re both from around the 1500s, both uses of the word.

Lauren: Huh. Fascinating. I didn’t realise that they both went back to the same point.

Gretchen: Possession is such a cool grammatical relationship. It’s such a spoooooky grammatical relationship that because this general concept of a range of meanings around the association between two or more nouns is found in a whole bunch of languages, but there’s lots of different, subtle ways that languages do this general category of relationships in different ways.

Lauren: Some languages just straight up have things that can’t be in a possession relationship. Generally, you get things like rivers or stars can’t be in one of these possession constructions, or you have things that have to be possessed. In a language, you might typically see obligatory possession on domestic animals, but you can’t use it for wild animals.

Gretchen: I mean, I think, like, I’d be pretty surprised to see someone talking about “my sun” or “my moon” – in maybe a sufficiently sci-fi context where you have people living on different planets and different solar systems to be like, “Well, our moon is like this, and your guys’s moon over there on your planet (or your three moons) are like that,” or something like that. But I think this is pragmatically a bit odd in English even if grammatically you could say it. It’s just like, what would you mean by that? One example of this which is a more formal constraint and less about the particular meaning is that in Guaraní, which is an Indigenous language of Paraguay, there are certain types of nouns including animal names where you can’t just say something like, “my chicken,” the way you can say, “my mother.” You have to add an additional word. In this case, for a word like “chicken,” it’s a word that means, basically, “pet.” Instead of saying, “my chicken,” you have something like, “my pet chicken,” to indicate that this animal now belongs to the category of things that could be possessed. It’s not so much about, like, you know, people can’t possess animals because they’re fine to say, “my pet chicken,” you just need this additional word added in to do that. People find it confusing, or it sounds strange, if you don’t put that word in.

Lauren: The flip side is that there’re languages where you will have a word that can’t be used without the possessive construction. In Seko Pedang, which is an Austronesian language spoken on the island of Sulawesi, which is part of Indonesia, there’s a really great noun that means “basketful.” It’s quite a handy noun. But it can only be used in possessive constructions. You can’t just have the noun “basketful.” It has to be something like, “my basketful,” or “his basketful.”

Gretchen: Because the idea is if the basket is full of stuff, it’s because someone put it there intentionally, and they wanna keep using it.

Lauren: It’s clearly going to be someone’s basketful. The other example they give for a noun where it’s totally fine to not have it marked – it’s not like all nouns have to do this – is a shirt because you can buy a shirt or loan someone a shirt, the ownership relationship isn’t as important to the meaning.

Gretchen: This is an example of how I could make the same argument for “shirt” that someone has clearly made this shirt – shirts don’t just grow on the bushes and come into appearance – but in this language, it’s like, “Yeah, no, a shirt doesn’t have to belong to someone, but a basketful does have to belong to someone,” which is this very language-specific aspect of that.

Lauren: Yeah, and where you draw the line between what is required to be possessed – or in a language where it’s not grammatically possible to use a possession construction – that’s something you have to figure out for the particular language.

Gretchen: Are there any other languages you know that have these things that are obligatorily possessed or not possessed?

Lauren: I remember when I was learning Nepali, there is a particular set of small things that you tend to just have with you where you can’t use a possession construction. It’s considered weird and a bit unnecessary. Instead of saying, “my pen,” or “my change,” or “my cash,” I would say, “the pen with me,” or “the cash with me,” or “the bag with me.”

Gretchen: Is this like the difference between a disposable plastic shopping bag versus a nice tote bag or a purse or a knapsack that you’ve probably put money into and invested – you’d be attached to, and you’d be sad if you lost? Whereas if I lose a plastic shopping bag, I’m like, “Oh, well, I’ll just get another one. It’s fine.”

Lauren: I think if you had a beautiful fountain pen, it would be, “my pen,” but if you just have a Biro on you, you would say, “It’s with me.” I remember one time using the “Oh, that’s my bag” for a plastic shopping bag, and people thought it was very funny that I would feel the need to exert ownership over this transient thing.

Gretchen: It’s interesting that you can have both things that are too big and important, like the moon, for one person to assert ownership over them and also things like, I dunno, a safety pin, a cheap pen, a plastic bag.

Lauren: I mean, we kind of have this in English as well. I could say, “Do you have a pen on you?” or “Have you got any money on you?”

Gretchen: Oh, and you’re trying to separate me from the concept of the pen of like, “Maybe I’ll borrow your pen, and it’s just a cheap pen, and I might not give it back.”

Lauren: I mean, I’m definitely tying to separate you from the money, that’s why I’m trying to make you feel like it’s not yours, it’s just with you.

Gretchen: Whereas to say, like, “Oh, do you have a car on you, by any chance, that I could borrow?”

Lauren: I think the important thing with these distinctions is you can come up with a meaning-based rationalisation. I definitely had to do that with Nepali to get my head around the construction. But at the end of the day, it’s about what’s grammatical and not grammatical in a language and the lengths you have to go to to try and make it feel like a grammatical thing in your head.

Gretchen: One type of grammatical distinction that a lot of languages have some version of is this idea that there are some elements that’re intrinsically always possessable or in relationship to another entity, and there are some that have this optional relationship. But this happens really differently depending on which language which things go in this category or not.

Lauren: So, something like, “your arm,” is very much attached to you. That relationship cannot be ended easily, I would like to say.

Gretchen: Body parts are a really good example. Even if some terrible circumstance or some horrific horror-movie type circumstance happens, and it does get detached from your body, you’re still feeling very attached to it in an emotional way even if it’s not physically connected to you right now.

Lauren: Physical connection isn’t the only thing because family relationships are another kind of not-ending relationship that you have.

Gretchen: Family relationships are like, you’re not just a grandmother, you’re a grandmother to someone or several someones. There’s no being a grandmother in abstraction that exists without grandchildren to be a grandparent of. In a language like Ojibwe, for example, which is an Algonquian language spoken in Canada, “ninik” is “my arm,” but there’s no context in which a person just says, “*nik,” to mean “arm” in abstract the way you can in English. Or “nookmis” is “my grandmother,” but there’s no context in which you’d just say like, “*ookmis,” that’s not a word. No one goes around saying that to just mean “a grandmother” in abstract.

Lauren: They’ve got the little ungrammatical notations there [asterisks in the written example being drawn from].

Gretchen: But sometimes languages actually do let you make this fine-grained distinction between two different types of ways of possessing a noun. We have this example from Hawaiian, where they actually use two different ways to mark possession depending on whether it is this intrinsic association or it’s this external, separable association. If you say, “nā iwi o Pua,” this means, “Pua’s bones (in Pua’s body).” “Pua” is a person’s name.

Lauren: Right. Definitely intrinsically attached. Hard to end that relationship with your bones.

Gretchen: Very much so. But “Pua” could also be eating a nice chicken dinner, and then you might have, “nā iwi a Pua,” instead of “o Pua,” and this could mean, “Pua’s bones (as in the chicken bones that Pua is eating).” It’s like, “Pua, are you done with those bones yet, or are you gonna save them to make chicken stock with?” They no longer belong to the chicken because the chicken is no more. They belong to Pua but in a separable way where Pua could be like, “Actually, I’m not hungry for all of these. Would you like to have some?”

Lauren: What a neat little pair to show that distinction.

Gretchen: Yeah, it’s this very subtle distinction between what it means to own something in two different ways.

Lauren: I think it’s fair to say English doesn’t have this as a core feature. Because if you say something like, “She has her father’s eyes,” usually we mean that as, “Ah, she has the same coloured eyes as her father.” We could also imagine a fairly horrific context in which she has acquired her father’s eyes physically in her hand.

Gretchen: Because if you were to say, “She has her father’s book,” that doesn’t necessarily mean that her book resembles her father’s book. It probably means she borrowed this book from her father. But in the context of a thing like eyes, it’s really context and our knowledge of how eyes work that enable this to happen.

Lauren: There’s nothing grammatically distinct happening between those two there.

Gretchen: I’m thinking of the children’s book series Amelia Bedelia where sometimes Amelia Bedelia takes on these very literal interpretations of what someone said. I can picture Amelia Bedelia being like, “Oh, you want me to have my father’s eyes? Okay.” [Plucking noise] Plucks the eyeballs out, and you’re like, “Amelia Bedelia, no, don’t do it!”

Lauren: Okay, yeah, we’ll save that for the Amelia Bedelia horror fanfic community. Free idea right there.

Gretchen: Body parts and kinship terms are the most common types of meanings that are expressed by this grammatically different type of possession, but other things that sometimes have a special possession marking are social relationships like a trading partner or a neighbour or a friend. You can’t just be a friend in isolation. You have to be a friend “of” someone, or you have to be a neighbour “of” someone.

Lauren: That makes sense.

Gretchen: Also, part-whole relationships, like “the tabletop” is part of the table. The top doesn’t exist without the table also existing – “the side of the table” – things that originate from someone, like your sweat or your voice, again, hard to imagine them existing without a body to put them into existence. Mental states and processes like fear or surprise, which only exist because someone gives rise to them. And also, sometimes attributes like a name or an age, which you can sometimes conceive of as “What does an age mean unless it’s an age of someone? Otherwise, it’s just a number.”

Lauren: And someone’s name is always attached to a someone, so that also makes sense.

Gretchen: I mean, sometimes you can say like, “How many people do you know named ‘John’?” or something like that, which could separate it out, but languages don’t necessarily include all of these categories. These are just some that, depending on the language, they’re gonna either group with this intrinsically possessed group or say, “No, we can conceive of these as being potentially separate.”

Lauren: I think it’s very satisfying for the theme of this episode that the technical term for this is about whether something is “inseparable” and, therefore, “inalienable,” or if something is “separate” or can be terminated in a relationship and, therefore, is “alienable.”

Gretchen: Because you could also dress up as a spooky alien!

Lauren: Yeah, that’s entirely why. Alienable possession is a great spooky linguistics costume.

Gretchen: You can imagine the spooky aliens being able to detach their heads from their bodies and move at a distance or something like this – some headless horseman or dressed up as Marie Antoinette and carry your own head around on a platter type of the costume.

Lauren: Oh, I like that. And then most of the most non-linguists will think you’re Marie Antoinette, and most of the linguists will think you are alienable possession. Very good.

Gretchen: Definitely we can save this for our linguist costume party where we dress up as our favourite linguistic examples.

Lauren: Because there’re all kinds of relationships, and they need to be navigated, languages that have this alienable / inalienable distinction can come up with really interesting ways of dealing with both of those relationships. In Navajo, you have a word like “milk” that is intrinsically related to an individual. If you were to say, “bibe',” which is “her milk,” you can also have a form that is “'abe',” which is “something’s milk.” It’s handy if you don’t need to know which particular cow or soybeans your milk came from. Then if she goes to the store and buys some milk, it’s “be'abe'.”

Gretchen: This is like, “her something’s milk.”

Lauren: Yes.

Gretchen: It’s got both this unspecified aspect of like, “Well, the milk come from some entity,” but then also, she’s brought home the carton from the store.

Lauren: If you’re in a house with feeding parents, you really wanna be clear when someone says, “Oh, that’s her milk in the fridge.” Navajo conveniently makes that distinction. If it’s her milk that she’s bought – hands off. That’s for her cup of tea. Or if it’s milk for the baby.

Gretchen: But it’s got this interesting double possession. When we were doing research for this episode and coming up with lots of fairly typical examples of possession, and I was very unsurprised to see these examples like Ojibwe and Navajo and Guaraní because this distinction between alienable and inalienable possession is very characteristic of languages of the Americas – North and South America. A lot of them have this particular distinction. Even ones that linguists don’t typically consider “related” in a historic sense, there is, I guess, enough language contact and various things that, like, lots of languages of this area have them. Then I read that French has this distinction, and I was like, “Hang on, I speak French.”

Lauren: Hang on, you speak French.

Gretchen: How have I never noticed that French has this distinction? I’m familiar with the distinction, and I’m quite familiar with French.

Lauren: This was a surprise to you.

Gretchen: It had never occurred to me that French actually has this distinction, but it’s there. I've produced it.

Lauren: Amazing. How does it work in French?

Gretchen: In French this is only with body parts. This is a really good example of languages will sometimes pick up one area of the stuff that can be intrinsically possessed. French doesn’t even do it with kinship terms, which is another area that’s super common. It’s only body parts for French. You can say something like, “Je me lave les mains,” which literally means, “I wash myself the hands,” but is the idiomatic way of saying, “I wash my hands.” But you can only do this for body parts. I can say, “Je me lave les cheveux,” “I wash myself the hair,” and other parts of the body.

Lauren: So, there’s no specific “apostrophe S” equivalent possession thing in there; it’s just because it’s a body part, and it’s myself.

Gretchen: And it’s reflexive, yeah. It’s “I wash myself the hands.” It’s not just “I wash the hands.” It’s like, “I wash myself the hands.” But if you wanna say like, “I wash the horse” – or “I wash my horse” – you would say, “Je lave mon cheval.” If you go around saying, “Je me lave le cheval” –

Lauren: “I washed myself the horse.”

Gretchen: – it really starts to imply that the horse is part of me.

Lauren: Are you a centaur?

Gretchen: Maybe I’m a centaur in this situation, and I refer to my lower half as “the horse.”

Lauren: Whereas in English, “I washed my hands” and “I washed my horse,” you’re just using the “my” construction. It doesn’t matter if it’s a body part.

Gretchen: I’m using the same construction, yeah, exactly. I can’t do this – like, if I have to give a child a bath, I can say, “Je lave l’enfant,” or “Je lave mon enfant,” if it’s my kid, but if I say, “Je me lave l’enfant” –

Lauren: “I washed myself the child.”

Gretchen: I think that – “Je me lave le bébé” – maybe if I was pregnant, and the baby was in my belly, and I was joking about washing my belly as if it was washing the kid or something.

Lauren: You’re getting into very specific contexts to make sense.

Gretchen: Very specific scenarios. I was texting some other friends who speak French because I was like, “Is this just me because I know that I sometimes have intuitions about French, and sometimes I don’t,” but I was really getting – especially with “Je me lave l’auto,” “I wash myself the car,” which really implies that I’m in some sort of transformers mech suit situation where I am the car. There’s no other meaning of that.

Lauren: Right. What about something that’s really close to being a body part but not quite, like if you had to wash your shadow?

Gretchen: Well, okay, pragmatically, I don’t think I can wash my shadow, but I can see my shadow, and that’s reflexive, too.

Lauren: Okay, yeah. I’ll be very kind and give you an example sentence that’s almost sensical, sure.

Gretchen: I think I still have to say, “Je vois mon ombre,” I can’t say, “Je me vois l’ombre,” where “I see myself the shadow,” in the way I can say, “Je me vois le visage,” “I see myself the face.” I think I can say that. I did text a few people to check this, and I also did a Google search, and there’s lots of Google results for “Je vois mon ombre,” but there are literally zero Google hits for “Je me vois l’ombre,” which is like, “I see myself the shadow” – the one that’s for body parts. There’re literally zero Google hits, although I guess there’ll be one once this episode is published because we have transcripts. But yeah, it turns out that there are actually a bunch of European languages that do something similar with specifically body part possession. German does something similar, “I wash myself the hands.” Italian does something similar, “I wash myself the hands.” It’s specifically very body part-y, which raises the question of why English doesn’t do it. To be honest, I don’t know.

Lauren: We’re missing out, English.

Gretchen: This is something that is also going on in other language families in this slightly different way where you don’t have kindship terms involved.

Lauren: English doesn’t have this, but we do have the benefit of having three completely different ways of marking possession. We have that “plural S,” we have “of,” and we have “have.”

Gretchen: “We have ‘have’.” English possesses three strategies.

Lauren: Let’s start with “apostrophe S.”

Gretchen: I like “apostrophe S” because it’s really, really old as a possessive strategy when using it in English. Old English had lots of suffixes on the ends of nouns that indicated their role in the sentence. The surviving one – the one that’s still kicking around – is this Modern English “apostrophe S.”

Lauren: It’s a relic.

Gretchen: It’s a zombie!

Lauren: Definitely the zombies are – this is part of why pronouns – so it’s possessive “mine,” “yours,” “theirs.” That’s why they also have those. “Mine” is slightly different because there used to be a whole bunch of different endings.

Gretchen: This changing in the endings of the nouns to show what their relationship is to the rest of the sentence is a phenomenon known as “case,” which we’re not gonna get into in detail. It is marking things in relationship to other things.

Lauren: Which you is a thing you can see is really handy because there’re all kinds of relationships we’re navigating all the time of, especially, family relationships. We all grow up in contexts where there are, maybe, kids or siblings or grandparents, and this all needs to be figured out in terms of like, “This is my sister,” and “That’s my mom’s daughter.”

Gretchen: I love this thing that you get with kids around age 3 or so where they’re beginning to realise that the person they might call “Mom” is not a person everyone else also calls “Mom” because other people might have their own mom or might not have a mom. Not everyone’s mom is that one person.

Lauren: Also, who everyone is to everyone else. Like, “my sister” is going to be “their aunt.”

Gretchen: Right. There’s this very fun example that I came across on Twitter where this guy says, “This kid pointed at my dog and said to his mom, ‘Nice doggie,’ and then pointed at me and went, ‘That’s his dad’.” But the guy is like, “Technically, though, as my dog used to stay with my grannie and granda, and they refer to themselves as his ‘ma’ and ‘da,’ the dog is actually my uncle.”

Lauren: Amazing. I’m glad he’s taking this relationship very seriously and triangulating it within the family space.

Gretchen: What’s interesting about this ending situation is that the Old English ending was “-es” for the possessive for a lot of the nouns, but some of the other nouns had other endings as well. By the 16th Century, this “-es” ending got generalised to all of the nouns. Then gradually the spelling “-es” remained, but in many words, the letter E was no longer being pronounced.

Lauren: Oh, so by the 16th Century, it was the way it’s pronounced now.

Gretchen: Basically, yeah. Instead of having “cat / cat-ES,” for “the cat’s tail,” you would just have “cat / cats,” much like we have now. Although, there are still some words in English – words ending in S or in another sibilant sound – that still have that “-es” ending, like “the fox’s tail.” Printers started copying the French practice of substituting this apostrophe for this letter E that wasn’t pronounced anymore.

Lauren: Ah, so that apostrophe is actually a ghost – keeping with our haunted episode theme.

Gretchen: It is a ghost of an E that once was there.

Lauren: Hmm, spooky~~~

Gretchen: Spooky. But it’s pronounced, at this point, the same way as the plural, like, “the cat’s tail” versus “I saw two cats” is pronounced the same. This apostrophe – if you get confused about apostrophe usage – you can blame these Early-Modern English printers because, honestly, this situation was not necessary, and we actually would’ve been fine with no apostrophe at all because this works fine in the spoken language.

Lauren: It even created a bit more confusion because there was some point a century after the apostrophe, and people started assuming that the S was “his” as like, the other possessive form that finished in an S. So, you found people saying things like, “Saint James-his Park” rather than “Saint James’s Park.”

Gretchen: Exactly. It’s just been the source of so much unnecessary confusion. Modern English speakers sure don’t think of it as like, “Oh, it’s just this short form of this thing that existed” because like, we don’t remember that this used to be an “-es.” That was hundreds of years ago. But once you’ve learned these very annoying rules, it does help us identify it – at least to talk about it in the possessive form – which brings us to “of.”

Lauren: Which is our second possessive construction and in Old English meant “away” or “away from.”

Gretchen: Wait, is “of” related to “off”? Because that also feels like what “off” means.

Lauren: Apparently, yeah. “Off” was an emphatic form of “of of,” and then they diverged into their own little lanes.

Gretchen: Oh, neat.

Lauren: But that “from” gives you an idea of how this locational sense of the construction works.

Gretchen: I feel like “of” gets used to translate “de” from Old French or “de” from Latin, so that often the English constructions that have an “of” in them feel maybe a little bit more Latin-y or French-y, a bit more formal maybe.

Lauren: Yeah, I can see that. Like, “The Leaning Tower of Pisa” definitely sounds fancier than “Pisa’s Leaning Tower.”

Gretchen: [Laughs] Oh, you mean we could’ve been saying “Liberty’s Statue” instead of the “Statue of Liberty” this whole time?

Lauren: Oh, that does not work for me. I think it’s partly because it’s a set phrase, but also partly because that “apostrophe S” does just sound a little bit more informal.

Gretchen: Maybe because the “of” has a little bit more of a tendency to be locational in the “from” sense, which is there etymologically rather than just associated with. But I do find it fun to just think about examples of set phrases that either have “of” or “apostrophe S” in and see how they feel when you swap them. Like, “China’s Great Wall” or “Giza’s Great Pyramid.”

Lauren: “Paradox of Zeno.”

Gretchen: “The Law of Murphy.” As we were preparing this episode, I just spent several days going around my life noticing these and flipping them in my mind, so I hope that I have now infected everybody with that.

Lauren: The distinction between “apostrophe S” and “of” constructions can also give you – as an English speaker – a little bit of an alienable / inalienable distinction sense. For these kinds of constructions, you can say something like, “the brother of Mary.”

Gretchen: Which is just as good as “Mary’s brother.” They sound the same to me.

Lauren: Which is just as good as “Mary’s brother.” But if you had something that is more alienable and less of an intrinsic relationship – something like, “the bat of Mary.”

Gretchen: Versus “Mary’s bat.” Mary could have a pet bat. But “the bat of Mary,” I’m just getting a little bit confused in the way that I wasn’t with “the brother of Mary.”

Lauren: It’s been argued that this is because kinship relationships are more intrinsic and inalienable and closer than a general possession relationship, and that’s why it sounds less natural. Our final possessive structure in English is the use of “have” as a verb.

Gretchen: In English, we can say something like, “I have some candy.” This is fine. But some languages don’t have a specific verb that indicates possession. They, instead, use a different strategy to say a full sentence that’s a possessive. The one that I’m most familiar with – and this one happens in Scottish Gaelic and also Hindi, which are two Indo-European languages spoken very far from each other, which translates as something more like, “at me is some candy.”

Lauren: That’s kind of what that Nepali “with me is a pen” construction is doing. Nepali and Hindi are very closely related languages, so that makes sense.

Gretchen: There’s other constructions like “Mine is some candy” or “Some candy is mine.” I think this is similar to what Finnish does, where you have a possessive but not in the verb. There’s an example from Tondano, which is an Austronesian language spoken in northern Sulawesi. The broad translation that you might use in English is “The man has two houses,” but it’s something more like, “As far as the man is concerned, there are two houses.”

Lauren: Right. It’s kind of like “the man,” and then you’re drawing attention to the man as the one doing the possessing, and then the thing that’s being possessed is just there.

Gretchen: “The man” is the topic of the sentence, and then “There are two houses,” and so you infer this relationship between them. You can paraphrase it in various long English ways like –

Lauren: “As far as the man is concerned.”

Gretchen: “Speaking about the man,” “with regard to the man.” I like to think of it also in e-mail style as like, “Re: me, various candy.”

Lauren: I like that. I think that’s getting much more at the grammatical structure of that.

Gretchen: Well, because these topicalising words tend to be really short because they’re used a lot in languages that have them. I just think that saying like, “as far as X is concerned,” makes it sounds really clunky, whereas if you’re just like, “Re: the man, candy,” it gets forward how concise this can also be.

Lauren: We know that candy doesn’t own the man. We know it’s the man that has the candy.

Gretchen: Well, and if you wanted to convey the inverse, you’d have to say, “Re: the candy, the man.”

Lauren: It’s another horror movie premise.

Gretchen: Exactly. Like, “Woo, spooky candy possessing people.” [Lauren laughs] You can also do things like, “I am with some candy,” “me and a candy,” “me – candy, too,” with sorts of “with” styles of possessive. And even just putting the two nouns next to each other and, again, inferring this type of relationship – maybe the ordering has some sort of effect like, “the child, candy,” and you can infer a sort of adjective-y relationship with them.

Lauren: It’s also worth noting for languages that do have a verb like English “have,” it’s usually from some kind of verb that indicates physical control or handling. In English, “have” has become our verb, but in other languages, it can be a verb that’s more like “take” or “grasp” or “hold” or “carry.” You can kind of see how all of those indicate some kind of possessing relationship that then goes on to be a general possession verb.

Gretchen: And “have” itself comes from a Proto-Indo-European root that means, “to grasp” – “*kap-” meaning “to grasp.”

Lauren: All of this is just a really nice reminder that you can start with this general idea of a relationship between two things, but languages are gonna use a whole bunch of different strategies for putting that into the grammar.

Gretchen: And “possession” is the most common word used to describe this in English even though it has this connotation of being very possessive about something or this, maybe, capitalistic possession and ownership – or being haunted. Another word that’s used to describe this in a formal grammar sense is “genitive,” which comes from a root meaning “to generate” or “progeny,” like “give birth to.”

Lauren: Okay, one of those relationships that we’ve seen a lot of – interpersonal relationships.

Gretchen: Exactly. This category of relationship is often named for one of its prototypical relationships, and then there’s a whole bunch of other things that get subsumed into that category because the same grammatical construction – you pick one of its prototypical uses, and then you extend it to a whole bunch of other types of meaning-based relationships even though the grammar-based one is the same across the whole category.

Lauren: I think it’s always good to remember that there are all of these different kinds of relationships that get caught up within this one grammatical category, and if I say, “They’re my student,” or “They’re my child,” it doesn’t mean they are my possession in a capitalistic, “ownership of” way. It’s just a way of indicating this relationship between us.

Gretchen: In fact, if someone is your student or your child, they also have a possessive relationship with you. You’re their advisor or their mentor or their professor or their parent. So, in many cases, these possessive relationships have a really important element of reciprocity that we’re each other’s friends or neighbours, or that parent-child or mentor-mentee have an element where the possession goes both ways because it situates us in some of the ways we relate to each other. Languages have lots of different ways of expressing these types of relationships between beings and elements of the world, but it’s very, very common cross-linguistically to have some way of doing this category of relationships, which suggests that it’s something that’s really important to all of us and part of our shared humanity.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including Gavagai, IPA, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like our new “Ask Me About Linguistics” stickers and “More People Have Read the Text on This Shirt Than I Have” t-shirts – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. My social media and blog is Superlinguo.

Gretchen: Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. My blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help us keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus episodes include alien languages and whether we could figure them out, a behind-the-scenes on Tom Scott’s Language Files (which we collaborated on), and why the word “do” in English is so weird. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Lauren: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Gretchen: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#podcast#podcasts#transcripts#episode 97#possession#possessive#genitive#inalienable possession#alienable possession#spooky#spoopy#halloween linguistics#possession but this time it's ghosts

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride and Prejudice xth reread liveblog:

"And my mother—How is she? How are you all?"

"My mother is tolerably well, I trust; though her spirits are greatly shaken. She is up stairs, and will have great satisfaction in seeing you all.

- Elizabeth Bennet speaking to her sister Jane in Pride and Prejudice

I noticed an interesting usage of my. They're talking about the same person, mrs Bennet, the mother to both of them. And it looks like it's the same throughout the book.

Today people would say "how's mother", or rather "how's mum" instead I suppose.

#pride and prejudice#jane austen#possessive pronouns#language nerding#linguistics#inalienable possession

0 notes

Text

Mando’a masterpost

Most of my Mando’a linguistic nerdery you should be able to find under the hashtags #mando’a linguistics and #ranah talks mando’a. Specific topics like phonology and etymology are tagged on newer posts but not necessarily on older. I also reblog lots of other people’s fantastic #mando’a stuff, which many of these posts are replies to.

I also post about #mandalorian culture, other #meta: mandalorians and #star wars meta topics, #star wars languages, #conlangs, and #linguistics. I like to reblog well-reasoned and/or interesting takes on Star Wars and Mandalorian politics, but I am not pro or contra fictional characters or organisations, only pro good storytelling. You can use the featured tags to navigate most of these topics. Not Star Wars content tag is #not star wars, although if it’s on this blog, likely it’s tangentially related or at least Mandalorian-coded.

Currently working on an expanded dictionary and an analysis of canon Mando’a. Updates under #mando’a project. Here are my thoughts on using my stuff (tldr: please do). My askbox is open & I’d love to hear which words, roots or other features you want to see dissected next.

#Phonology

Mando’a vowels

Murmured sounds in Mando’a

Ven’, ’ne and ’shya—phonology of Mando’a affixes

#Morphology

Mando’a demonyms: -ad or -ii?

Agent nouns in Mando’a

Reduplication in Mando’a

Verbal conjugation in Ancient Mando’a & derivations in Modern Mando’a

-nn

Adjectival suffixes (this one is skierunner’s theory, but dang it’s good and it’s on my post, so I’m including it)

e-, i- (prefix) “-ness”

#Syntax

Middle Mando’a creole hypothesis — Relative tenses — Tense, aspect and mood & creole languages — Copula and zero copula in creole languages — More thoughts about Mando’a TAM particles

Mando’a tense/aspect/mood (headcanons)

Mando’a has no passive

Adjectives as passive voice & other strategies

Colloquial Mando’a

Alienable/inalienable possession — more thoughts

Translating wh-words into Mando’a

#Roots, words & etymology

ad ‘child’—but also many other things

adenn, ‘wrath’

akaan & naak: war & peace

an ‘all’ + a collective suffix & plural collectives

ba’ & bah

*bir-, birikad, birgaan & again

cetar ‘kneel’

cinyc & shiny

gai’ka, ka’gaht, la’mun

jagyc, ori’jagyc & misandry

janad

*ka-, kakovidir & cardinal directions

ke’gyce ‘order, command’

*maan-, manda, gai bal manda, kir’manir, ramaan & kar’am & runi: ‘soul’ & ‘spirit’

*nor- & *she- ‘back’ (+ bonus *resh-)

projor ‘next’

riduurok, riduur, kom’rk, shuk’orok

*sak-, sakagal ‘cross’

*sen- ‘fly’

tapul

urmankalar ‘believe’

*ver- ‘earn’

*ya-, yai, yaim (& flyby mentions of eyayah, eyaytir, gayiyla, gayiylir, aliit)

Dialectal English & slang in Mando’a

#Non-canon words

Mining vocabulary

Non-canon reduplications

Many words for many Mandalorians

What’s the word for “greater mandalorian space”?

Names of Mandalorian planets

Dral’Han & derived words

besal ‘silver, steel grey’

derivhaan

hukad & hukal, ’sheath, scabbard’

*maan-, manda, kar’am & runi: ‘soul’ & ‘spirit’ & derivations

mara/maru, ‘amber-root’

*sen- ‘fly’ derivations

tarisen ‘swoop bike’

*ver- ‘earn’ derivations

#mando’a proverbs

#mando’a idioms

Pragmatics & ethnolinguistics

Middle Mando’a creole hypothesis

History of Mando’a — Loanwords in Mando’a

Mando’a timeline

Mandalorian languages

#mandalorian sign language

Kinship terms

Politeness in Mando’a: gedet’ye & ba’gedet’ye — vor entye, vor’e, n’entye — vor’e etc. again — n’eparavu takisit, ni ceta

Mandalorians and medicine, baar’ur, triage

#Mandalorian colour theory (#mandalorians and color): cin & purity, colour associations & orange, cin, ge’tal, saviin & besal, gemstone symbolism

#Mandalorian nature, Flora and fauna of Manda’yaim

starry road

Concordian dialogue retcon

A short history of the Mandalorian Empire

Mandalorian clans & government headcanons

Mando’a handwriting guide: part 1, part 2, part 3

What I would have done differently if I had constructed Mando’a

FAQ

Can you answer a question about combat medicine? May I direct you to my post about Free tactical medicine learning resources.

Can I use your words/headcanons in my own projects? Short answer: yes please.

Do you do translations? If I happen to be in the mood or your translation question is interesting. Feel free to bomb my inbox, but don’t expect quick answers.

What’s your stance on Satine Kryze and the New Mandalorians? They’re fictional and I don’t have one beyond their narrative being interesting & wishing that fandom would have civil conversations about them without calling each other names.

Why do you portray Mandalorians as multi-racial and gender-agnostic when they’re not that diverse in canon? Because that’s the power of transformative works: to create the kind of representation we want to see in a world where it’s lacking.