#i just. what is it with american textbooks and metaphors that not only make no sense but are unnecessary too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

There's a specific type of stupidity that can only be found in American textbooks.

#yes i know pearson is uk based but campbell was american and so are many of the other people working on this book#i just. what is it with american textbooks and metaphors that not only make no sense but are unnecessary too#they always gotta compare straight-forward concepts to random everyday encounters and it never clarifies anything

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No but listen. Abed sees Britta as "Britta Bot" while everyone else describes him as cold and robotic. People assume that his problem is being distant and lacking empathy, but that's Britta! We see it every time that Abed has a breakdown, she stops treating him as an individual and instead defaults to what she thinks is the appropriate response. It's all therapy talk with no understanding of who Abed is as a person or what would actually help him, because as soon as he starts displaying symptoms he stops being her friend and becomes a person she must help by picking the correct responses out of her psych textbook.

I am not saying this out of hate for Britta! I love Britta! I just think it's really interesting that one of the things she struggles with most throughout the series is her inability to be empathetic, and no one sees it but Abed. Her focus on political correctness and activism seems emotional, but it's more often about her wanting to do The Right Thing (which she sees as a monolith) than her actually feeling invested in helping individual people.

What's especially interesting is that Abed characterizes her weakness as "no faith in herself or friends," which implies that one reason she's so focused on doing the correct thing is that she doesn't trust her genuine responses to help anybody. She's afraid of making things worse, so she goes with what she's been told she should do in high stakes situations (like her friend hallucinating stop motion dolls or lava floors). In season one especially she always baby-talks to Abed, because her brother works with autistic kids so that's how she thinks you talk to autistic people. She's trying so hard to be accommodating, but it's from a perspective of "I know The Correct Way To Talk To Autistic People" rather than "let me learn how to best connect with this person." It could be called robotic, following her memorized paths for interactions even when they're clearly hurting people she cares about.

Then there's Abed, who does have some troubles with empathy which often show up when he manipulates people around him in order to achieve his goals, (ex: "Introduction to Film," "Contemporary American Poultry," "Anthropology 101"), and is always seen as cold and distant, safely removed from thr situation. He leans into that intentionally, acting as though he's "not in this scene" or giving logical trope-based reasons to avoid facing his fears (like when Troy wants to move in with him and Abed calls it "jumping the shark"), but deep down he's incredibly emotional. He's the one who willingly risks his life in "Epidemiology," he and Troy give up their bedroom for Annie, he lets his friends matchmake for him because he knows it's important to them.

Even when he is being all supposedly logical, it's often because he doesn't want to acknowledge his own feelings and feels safer acting as though sitcom tropes are the only thing making him act that way. In the argument about living together, Troy was right that they could just not put a line of tape down their floor, Abed knows that real life is different from TV and doesn't always escalate to the most dramatic possible conflict, but he doesn't want to say that he's afraid of Troy getting sick of him so it's easier to use shark jumping as an excuse.

They're such interesting foils; Britta who flaunts how much she cares to conceal how insecure she is about not caring, and Abed who puts up his lack of investment as a shield to protect him from how deep his emotions run. I don't think it's accurate to describe either of them as robots, but that metaphor really does ping off both of their insecurities about not performing humanity correctly. They both just want to do the right thing and help people, even if they get it wrong sometimes.

#yeah rewatching abed's uncontrollable christmas made me even more normal can't you tell#i <3 britta being afraid of showing care wrong and abed being afraid of getting caught caring#community#nbc community#community tv#britta perry#abed nadir#my analysis

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

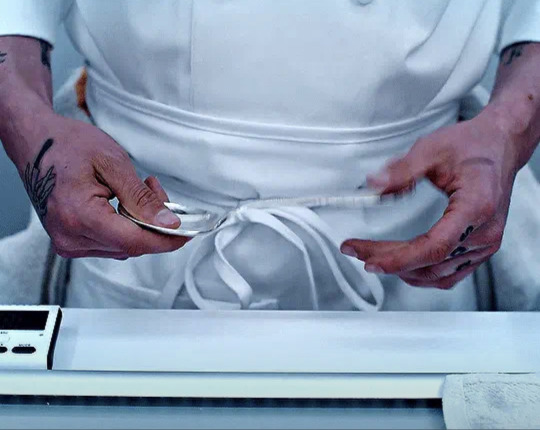

Storer

I've been diving deep into Storer's body of work pre-The Bear during the last few weeks. It's been exhilarating. He's sooo good that I'm still clueless in some aspects, TBH, which I love and drives me crazy in equal measure, of course. His scriptwriting style is more on the journalism side, that's why there's not much suspense but rather rawness in his lines, no regular plot twists, but twists in the layout of the plot, not in the plot itself.

He lets you in on what's gonna happen if you pay attention to the facts and details he presents, but he will definitely pull a twist as to how to go about it and make you reconsider the whole point he made earlier. He loves symbology and metaphors yet also uses those resources to divert, not just to tell the story, but to take the viewer off course and distract them, telling them a story that is not the real story he's telling, sneaky and clever, always. He's in the details and in the big picture at the same time, he writes boldly about the characters and lets you figure out the story by yourself, doesn't hold your hand, just shows it to you for you to make what you want or can out of it. I'm all for it.

As a director, he’s more conventional, which aligns with what he said about the movies he likes. It’s all there, clearly, he’s into “classic” movie-making. It’s easier to figure him out as a director than to figure out his narrative as a writer because he’s a shapeshifter yet a logical thinker. And I think that also has a lot to do with Joanna Calo, they are a great team when it comes to writing. She brings out his more subtle side. The journalism bouquet disappears and the deeper layers, psychology textbooks, etc show up. Fishes is a great example of that, the storyline is still raw (Storer) but it’s also in the layers, the softer ones (Calo) and then there’s the common ground they probably wrote together, which is what we perceive on screen as intensity to the point of being in a constant rollercoaster:

That’s not all Storer, that’s Stalo. And then there’s the cinematic style, which is more along the lines of the American indie style that was popular (and award-winning) in the 90s. I'm no expert on that, or on any of this... quite frankly... But I find it amazing, really, because that style is gone in the movies and Storer brought it back to TV and in this day and age, it’s a total game changer. I think we’ll start seeing more shows with The Bear’s aesthetic moving forward.

Anyway, so back to this passion project I have been working on for weeks now: I haven’t figured out what he’s gonna do with a 💯 level of certainty yet, which drives me crazy but I love it, of course. However, what I did figure out by now is all the potential plot twists he won’t be going for. All I can safely rule out because he would never do (I will be going over my notes on that in future posts). As a result, I'm now more confident than ever before about Sydcarmy being endgame. Not only it is a potential closure of the entire arc, with very solid chances of materializing, which we have all been thinking about all along, in my case since Braciole. It’s actually a total and utter certainty by now. My thesis on his work is very much still a WIP, can't wait for S3 to add it to the material I'm studying, but I will go about it more relaxed from now on because I already figured out what he will never do with Carmy.

There’s no version of The Bear in which he will put that character he created and that represents himself loves so much, through what he will put him through this upcoming season, without giving him whom he wants at the end.

Bonus track: let's pay close attention to spoons from now on.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! would you like to tell us about your research?

thank you anon, this means a lot to me.

The lab I'm working in this summer studies a type of virus called reovirus. It's an RNA virus like HIV or Covid, but unlike those viruses reovirus doesn't cause disease in humans. This brings us to the first and second uses of reovirus in virology: it's a good first virus for undergrads like me because it isn't dangerous, and it's a way to study the basics of more dangerous viruses without putting people at risk. Reovirus is a common model for rotavirus, which also has a double-stranded RNA genome but does cause disease in humans (it's a common cause of diarrhea in kids).

The third reason we study reovirus is because of how it interacts with our immune system. Much of what we think of as being sick is actually our immune system trying to kill off a pathogen- inflammation, runny noses, and other fun reasons to skip work are all signs of the immune system functioning as intended. Reovirus triggers immune responses that don't cause physical symptoms, however.

Which leads us to cancer.

Fundamentally, cancer is a failure of the immune system. Cells and the organisms they are a part of have a lot of failsafes to stop cancer from happening, and tumors need to avoid getting caught in them. This typically looks like accumulating mutations to cause unrestricted growth and then suppressing the immune system to allow that growth to continue (more on this). This has led to the idea that we could treat cancer by reactivating the immune system when cancer shuts it off. There are a wide range of therapies in this vein that are currently being developed, with intentional infection with reovirus being one that's currently in human clinical trials. The idea, metaphorically, is to have reovirus move into a tumor and have a housewarming party so wild that the cops get called, even though this is a neighborhood that the cops usually turn a blind eye to.

What makes reovirus particularly promising is that it prefers to infect cancer cells over healthy cells! To quote the American Cancer Society on why this is important:

Cancer cells tend to form new cells more quickly than normal cells and this makes them a better target for chemotherapy drugs. However, chemo drugs can’t tell the difference between healthy cells and cancer cells. This means normal cells are damaged along with the cancer cells, and this causes side effects. Each time chemo is given, it means trying to find a balance between killing the cancer cells (in order to cure or control the disease) and sparing the normal cells (to lessen side effects).

This means that one of the main issues of treatments like chemo, that they target quick-dividing cells rather than tumor cells only, could possibly be a nonissue with reovirus treatment.

What my labmates and I are looking at this summer (besides getting the lab back up and running, but that's a whole different story) is how reovirus specifically pulls in a part of the immune system called the interferon response, which is basically an SOS signal that causes cells to turn a bunch of genes on or off. We're also looking at whether cells with different metabolism profiles react to infection differently, and whether this can be used to specifically target certain cancers. My lab is just getting started right now (see: above parenthetical), but the work that's already been done is so exciting and I love talking about it!

Here's a chapter on reovirus from an ancient textbook, and here's a review of work on interferons, if you want to know more!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wizard of Oz and Populism

For folks in the USA side of things, you've probably had a unit or section of your history textbook or lecture talk about Populism (the political movement) and its origins/effects on Westward Expansion.

The history teacher I'm working with had a small assignment where students took the characters/motifs from the book and connected them to the things going on during the Glided Age.

TedED that the teacher showed us prior to the assignment:

youtube

SO. MANY. THOUGHTS.

So here are my thoughts on the metaphors and representation in Wizard of Oz.

So you have the yellow brick road being the representative of the gold standard for the value of the American dollar. The road is already established in the world of Oz and Dorothy must travel down it to find someone to help her get home.

In the books, the slippers that Dorothy wears are Silver, not Ruby (an adaption to show off the feats of Technicolor Photography and film). The silver slippers she wears are the Populism's want for a silver standard for the American dollar. The thought was, "If we can make currency based off of silver, we'd have more money in circulation and farmers would be able to pay off their debts sooner." In the story, the slippers do not change the road from 'gold' to 'silver'. Just like how the US did not change the dollar from Gold to silver.

Dorothy herself represents the American citizen wanting a place of belonging (immigrant? poor or the homeless? take your pick). She has been ripped away from her home by forces she can not control into the Land of Oz. Her constant desire is to "go home." She is set on her journey to ask the Wizard (the US government) to (give her) take her home, but the Wizard- all illusions and empty grandeur can not help her or her friends, beyond showing them what they already possess. Ultimately to "go home" (to find a home or land of her own) she must defeat the Wicked Witch of the West.

The Wicked Witch of the West represents the Wild West Frontier. She is a force of nature, who has ruled for far too long in her area of the land, that has to be tamed (defeated), and has minions (the flying monkeys who I strongly suspect represent the Native Americans that were defending their way of life against the white settlers) that do her bidding.

Dorothy (the Poor American trying to find a home) is sent to defeat the West. The WW of the West is defeated by water- which may be a metaphor itself about the harsh prairie droughts that were to come for those on the homesteads.

(Gee I wonder if Munckin Town was the border of the Established settlements prior to the Westward expansion?)

Glinda, the Good Witch of the North- Is the Homestead Act of 1862. Glinda, in the book sends Dorothy on her way to talk to Oz about going home and tells Dorothy to be wary of the Wicked Witch of the West.

But if they are enemies- why does Glinda do nothing to The Wicked Witch of the West?

Because the Homestead Act is only a piece of paper. And Paper, no matter how official or pretty or legal has NO POWER over the forces of the Wild West. Glinda uses her words to send Dorothy out to kill the Witch of the West (to tame the wild West into a settlement and cultivate it).

Also the whole "if you wish hard enough and do a little ritual you will be back home" sounds a lot like "If you work hard enough and do this one little (but really huge) task- you too can own land of your own"

And that's the end of my thoughts. Figured I'd vent it out here Pretty sure my students thought I looked like this:

#wizard of oz#be lucky you weren't in 1st period US history to hear my thought process#Its a good argument that Baum totally meant it to be more than a fairy tale#and I thought the tumblr peeps would appreciate it#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a really long and pointless ramble on one of the most boring books i've ever read, and how a danmei (TGCF) is deeper than it: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian

God. I fucking hate this book. For context, I was recently assigned this book in my English class. I was assuming it would share a lot of themes with To Kill a Mockingbird but with a different perspective. And let me tell you, I appreciate that book WAY more after this

Plot

True Diary is about a Native American teenager who lives on a reservation and struggles with poverty. After having a talk with his teacher after throwing a book at him (I'll touch on that later), he decides to move to a school in a farm town mostly populated by white kids.

This Book is Extremely Oversexualized for NO Reason

There are multiple points throughout the novel that just- really shouldn't be there. Here are some quotes:

"Naked women + right hand = happy happy joy joy. Yep, that's right, I admit that I masturbate. I'm proud of it. I'm good at it. I'm ambidextrous. If there was a Professional Masterbators League, I'd get drafted number one and make millions of dollars. And maybe you're thinking, "Well, you really shouldn't be talking about masturbation in public." Well, tough, I'm going to talk about it because EVERYBODY does it and EVERYBODY likes it."

"Have you ever watched a beautiful woman play volleyball? Yesterday, during a game, Penelope was serving and I watched her like she was a work of art. She was wearing a white shirt and white shorts, and I could see the outlines of her white bra and white panties. Her skin was pale white. Milky white. Cloud white. She she was all white on white on white, like the most perfect kind of vanilla dessert cake you've ever seen. I wanted to be her chocolate topping."

"The score was like 12-0. But I didn't care. I just wanted to watch the sweaty Penelope sweat her perfect swear on that perfectly sweaty day."

Gross right? There are more scenes like this, but I don't have the quotes on hand. At one point a kid said he got a "metaphorical boner" from reading, and the main character almost kissed a book once (more on that later!!)

The Unnecessary Derogatory Language

In the prologue, the r-word is prominently used, and the word Indian is used to replace Native American to describe the main character (from the main character's perspective). That is excusable, as the author based the main character off himself. He is a Native American and has excess spinal fluid. However, there are two examples of this book using genuine slurs. Of course, the main character hadn't said it, but my point still stands. The thing is? Take these out and NOTHING changes. Removing this language in a book like To Kill a Mockingbird actually has an excuse for this language since, ya know, it was made in the 1920s. This book? No reason. Just kinda throws in the f-slur and the n-word in there once.

The Plot is BORING

When it says "diary" IT MEANS A DAIRY. Take Diary of a Whimpy kid and strip it of the plot, add some horniness, and there. That's the book. The very inciting incident doesn't even make sense. Basically, our MC is about to make out with his textbook, until he realizes it has his mom's name on it. He's mad that the textbook is old. That's it. So he throws it at his teacher! This breaks his teacher's nose, but you know what happens? The teacher says that the kid got mad cuz. . . poverty??? It read like our MC was just mad they had an old book. But apparently, that means that they have a fighting spirit or something. SO THAT'S HOW HE ENDS UP GOING TO THE OTHER SCHOOL. His parents don't disagree, there's no argument, nothing. The only thing that comes from it is that his best friend (who is low-key a dick) is mad that he's leaving the reservation school for an all-white person school.

Okay. The title. How does Tian Guan Ci Fu act better as a book than this?

You see, here's the thing. In True Diary, there is ZERO takeaway. There really is nothing to learn from it. There's no lesson to learn, no challenge to overcome, nothing to think about. It's DEVOID OF LIFE! Yet, look at TGCF. so many people have taken away meaningful messaging from it. I've personally taken a liking to Hua Cheng, and especially the idea that he doesn't care about all the extravagant things he owns, but instead just his beloved. I relate to that a lot, and it speaks to me. And then look at True Diary? What does this serve? What can I learn? What can I think about?

okay that's it bye bye this was really long and dumb :)

#writing#books#tgcf#book critique#book criticism#writeblr#bookblr#tian guan ci fu#me when the bl is written better than the assigned book#this book sucks#i hate this book#augh

0 notes

Note

could you (or any of your followers perhaps) point me in the direction of... good reads about 19th century russian literary criticism / intellectual history? currently cramming for a term paper. i am thankful

don't you have, like, a teacher? what are you paying them for, if you still need to deputize crazy internet trannies for help? well, i'll do my best! also, use anki to memorize stuff! it's the memory machine!!

[900 words, mostly quotes]

anyway, when you talk about early Russian literary theory most people think about formalism, which didn't come around until the 1910s. from my textbook:

The most prominent members of the group were Victor Shklovsky, Boris Tomashevsky, and Boris Eichenbaum, whose work can be sampled in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, edited by Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (University of Nebraska Press, 1965). Their ideas included the need for close formal analysis of literature (hence the name), the belief that the language of literature has its own characteristic procedures and effects, and is not just a version of ordinary language, and Shklovsky's idea of 'defamiliarisation' or 'making strange' (expounded in the essay 'Art as Technique', which Lemon and Reis reprint) (Barry, 2002, Beginning Theory, pg 109; all page numbres correspond to the pdf)

and their rivals, "the Formalists' intellectually strongest opponents, the circle of Mikhail Bakhtin" (from that book, Lemon & Reis eds., 1965). i wanted to look at this to see if the editors or the formalists themselves grounded any of the discussion in 19th century precedents. thankfully they did! from the introduction:

The Russian Formalists, like the New Critics, learned much from the teachers whose works they were forced to attack. Historical scholarship had made extensive and precise information easily available; indeed, the Formalists’ work depended upon the availability of a huge reservoir of historical data. The moral-social critics like Vissarion Belinsky, Nicholas Chernyshevsky, Nicholas Dobroliubov, and Dmitry Pisarev contributed indirectly and negatively. [...]

But the Formalists learned most from the philologists—from Alexander Potebnya (1835–1891) and Alexander Veselovsky (1838–1906). Each in his own way worked toward a distinctly literary study of literature; each contributed to the discovery of an approach to literature that would prevent its subservience to any and all other disciplines. Potebnya’s insight was one of those simple discoveries that, when proclaimed, inevitably lead to a revolution in thought. Following Wilhelm von Humboldt, Potebnya saw poetry and prose (aesthetic and nonaesthetic language) as distinct, as separate approaches to the understanding of reality linked by their dependence upon language. Like many British and American critics of the following century, he drew two basic conclusions from this insight: that the study of literature as literature must be primarily a study of language, and that the preliminary problem in such a study is to define the peculiarities of poetic language as opposed to prose or practical-scientific language.

and:

Potebnya [...] made metaphor the basis of all poetry. But as Victor Shklovsky points out in “Art as Technique” (see pp. 5–6), Potebnya’s metaphors work in only one direction: they work only by presenting the unknown in terms of the known. Thus for Potebnya metaphor is essentially an aid to understanding, and poetry, the particular example of a general truth. Potebnya’s work was much more subtle than this; but the course of Russian poetry and criticism in the first two decades of the twentieth century led to the simplification, and it was the simplification that the Formalists felt they had to attack.

as for Valesovsky, he

arrived by a long and difficult process at the conclusion that the study of literature had to be self-contained—that it could not legitimately overlap into other disciplines—he argued that the motif and its uses were the proper subjects of literary study.

and he leaned a lot on folklore. this is a lot like what i know about 19th and early 20th century philology and folkloristics in general; that it began with something moral, nationalsitic and evaluative, and evolved into something formal, historical-linguistic, sociological, universalist, and sometimes excessively scientistic and prone to overgeneralization. this overall tendency is covered well by Peter Barry in the first chapter of the book i mentioned earlier (pg 16, titled Theory before 'theory'—liberal humanism) as well as by Michael Lapidge in the first chapter of Reading Old English Texts (1997, pg 32).

another secondary text that might help you make the garden path is International Folkloristics: Classic Contributions by the Founders of Folklore, ed. Alan Dundes, 1999, particularly chapter 10, In Search of Folktales and Folksongs, on the Russian folklorists Boris and Yuri Sokolov, who lived in the late 19th and early 20th century. in a later chapter on Vladimir Propp (an influential formalist) there is a book cited called Precursors of Propp: Formalist Theories of Narrative in Early Russian Ethnopoetics by Heda Jason, 1977, which might be helpful if you can access it (i couldn't find it).

oh yeah, and one right angle you might find interesting is Tolstoy's interest in Daoist texts. Tolstoy was extremely influential in the 19th century as an anarchist thinker, promoting a kind of pacifist, nonviolent moralizing anarchism which is not popular anymore. he was also interested in Daoism and talked about it a lot. he produced a Russian translation of the Daode Jing despite not speaking any Chinese, instead translating a French translation (which he had been warned was an awful translation and ignored this advice). i think i read about that in that one article about translations of the DDJ by people who don't speak Chinese lol (see). there's also an article about Tolstoy's use of daoism here.

hopefully those things help you some. if any of my followers can help out please do!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the Clone problem in Star Wars animated media is also a Mandalorian problem, and why we have to talk about it (PART 2)

Hi! I finally finished wrapping this up, so here’s part 2 of what has already become a mini article (you can find Part 1 here, if you like!)

And for this part, it won’t be as much as a critic as part 1 was, but instead I’d like to focus more on what I consider to be a wasted potential regarding the representation of the Clones in the Star Wars animated media, from the first season of The Clone Wars till now, and why I believe it to be an extension of the Mandalorian problem I discussed in part 1 — the good old colonialism.

Sources used, as always, will be linked at the end of this post!

PART 2: THE CLONES

Cody will never know peace

So I’d like to state that I won’t focus as much on the blatantly whitewashing aspect, for I believe it to be very clear by now. If you aren’t familiar with it, I highly recommend you search around tumblr and the internet, there are a lot of interesting articles and posts about it that explain things very didactically and in detail. The only thing you need to know to get this started is that even at the first seasons of Clone Wars (when the troopers still had this somewhat darker skin complexion and all) they were still a whitewashed version of Temuera Morrison (Jango’s actor). And from then, as we all know, they only got whiter and whiter till we get where we are now, in rage.

Look at this very ambiguously non-white but still westernized men fiercely guarding their pin-up space poster

Now look at this still westernized but slightly (sarcasm) whiter men who for some reason now have different tanning levels among them (See how Rex now has a lighter skin tone? WHEN THE HELL DID THAT HAPPEN KKKKKKK) Anyway you got the idea. So without further ado...

2.1 THE FANTASY METAPHOR

As I mentioned before in Part 1, one thing that has to be very clear if you want to follow my train of thought is that it’s impossible to consume something without attributing cultural meanings to it, or without making cultural associations. This things will naturally happen and it often can improve our connection to certain narratives, especially fantastic ones. Even if a story takes place in a fantastic/sci fi universe, with all fictional species and people and worlds and cultures, they never come from nowhere, and almost always they have some or a lot of basing in real people and cultures. And when done properly, this can help making these stories resonate in a very beautifull, meaningfull way. I actually believe this intrisic cultural associations are the things that make these stories work at all. As the brilliant american speculative/science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin says in the introduction (added in 1976) of her novel The Left Hand of Darkness, and that I was not able to chopp much because it’s absolutely genious and i’ll be leaving the link to the full text right here,

“The purpose of a thought-experiment, as the term was used by Schrodinger and other physicists, is not to predict the future — indeed Schrodinger's most famous thought-experiment goes to show that the ‘future,’ on the quantum level, cannot be predicted — but to describe reality, the present world.

Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.”

[...] “Fiction writers, at least in their braver moments, do desire the truth: to know it, speak it, serve it. But they go about it in a peculiar and devious way, which consists in inventing persons, places, and events which never did and never will exist or occur, and telling about these fictions in detail and at length and with a great deal of emotion, and then when they are done writing down this pack of lies, they say, There! That's the truth!

They may use all kinds of facts to support their tissue of lies. They may describe the Marshalsea Prison, which was a real place, or the battle of Borodino, which really was fought, or the process of cloning, which really takes place in laboratories, or the deterioration of a personality, which is described in real textbooks of psychology; and so on. This weight of verifiable place-event-phenomenon-behavior makes the reader forget that he is reading a pure invention, a history that never took place anywhere but in that unlocalisable region, the author's mind. In fact, while we read a novel, we are insane —bonkers. We believe in the existence of people who aren't there, we hear their voices, we watch the battle of Borodino with them, we may even become Napoleon. Sanity returns (in most cases) when the book is closed.”

[...] “ In reading a novel, any novel, we have to know perfectly well that the whole thing is nonsense, and then, while reading, believe every word of it. Finally, when we're done with it, we may find — if it's a good novel — that we're a bit different from what we were before we read it, that we have been changed a little, as if by having met a new face, crossed a street we never crossed before. But it's very hard to say just what we learned, how we were changed.

The artist deals with what cannot be said in words.

The artist whose medium is fiction does this within words. The novelist says in words what cannot be said in words. Words can be used thus paradoxically because they have, along with a semiotic usage, a symbolic or metaphoric usage. [...] All fiction is metaphor. Science fiction is metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors, drawn from certain great dominants of our contemporary life — science, all the sciences, and technology, and the relativistic and the historical outlook, among them. Space travel is one of these metaphors; so is an alternative society, an alternative biology; the future is another. The future, in fiction, is a metaphor.

A metaphor for what?” [1]

A metaphor for what indeed. I won’t be going into what Star Wars as a whole is a metaphor for, because I am certain that it varies from person to person, and everyone can and has the total right to take whatever they want from this story, and understand it as they see fit. That’s why it’s called the modern myth. And therefore, all I’ll be saying here is playinly my take not only on what I understand the Clones to be, but what I believe they could have meant.

2.2 SO, BOBA IS A CLONE

I don’t want to get too repetitive, but I wanted to adress it because even though I by no means intend to put Boba and the Clones in the same bag, there is one aspect about them that I find very similar and interesting, that is the persue of individuality. While the Clones have this very intrinsically connected to their narratives, in Boba’s case this appears more in his concept design. As I mentioned in Part 1, one of the things the CW staff had in mind while designing the mandalorians is that they wanted to make Boba seem unique and distinguishable from them, and honestly even in the original trilogy he stands out a lot. He is unique and memorable and that’s one of the things that draws us to him.

And as we all know, both Boba and Jango and the Clones are played by Temuera Morrison — and occasionally by the wonderful Bodie Taylor and Daniel Logan. And Temuera Morrison comes from the Maori people. And differently from the mandalorian case, where we were talking about a whole planet, in this situation we’re talking about portraying one single person, so there’s nowhere to go around his appearance and phenotypes, right? I mean, you are literally representing an actual individual, so there’s no way you could alter their looks, right?

(hahahaha wrong)

And besides that, I think that is in situations like that (when we are talking about individuals) that the actor’s perspective could really have a place to shine (just the same as how Lea was mostly written by Carrie Fisher). In this very heart-warming interview for The New York Times (which you can read full signing up for their 5-free-articles-per-month policy), Temuera Morrison talks a little bit about how he incorporated his cultural background to Boba Fett in The Mandalorian:

“I come from the Maori nation of New Zealand, the Indigenous people — we’re the Down Under Polynesians — and I wanted to bring that kind of spirit and energy, which we call wairua. I’ve been trained in my cultural dance, which we call the haka. I’ve also been trained in some of our weapons, so that’s how I was able to manipulate some of the weapons in my fight scenes and work with the gaffi stick, which my character has.” [2]

The Gaffi stick (or Gaderffii), btw, is the weapon used by the Tusken Raiders on Tatooine, and according to oceanic art expert Bruno Claessens it’s design was inspired by wooden Fijian war clubs called totokia. [3]

And I think is very clear how this background can influence one’s performance and approach to a character, and majorly how much more alive this character will feel like. Beyond that, having an actor from your culture to play and add elements to a character will higly improve your sense of connection with them (besides all the impact of seeying yourself on screen, and seeying yourself portrayed with respect). It would only make sense if the cultural elements that the actor brought when giving life to a fictional individual would’ve been kept and even deepened while expanding this role. And if you’re familiar with Star Wars Legends you’ll probably rememeber that in Legends Jango would train and raise all Clone troopers in the Mandalorian culture, so that the Clones would sing traditional war chants before battles, be fluent in Mando’a (Mandalore’s language) and some would proudly take mandalorian names for themselves. So why didn’t Filoni Inc. take that into account when they went to delve into the clones in The Clone Wars?

2.3 THE WHITE MINORITY

First of all I’d like to state that all this is 100% me conjecturing, and by no means at all I’m saying that this is what really happened. But while I was re-watching CW before The Bad Batch premiere, something came to my mind regarding the whitewashing of the Clones, and I’d like to leave that on the table.

So, you know this kind of recent movies and series that depicted like, fairies in this fictional world where fairies were very opressed, but there would be a lot of fairies played by white actors? Just like Bright and Carnival Row. If you’ve watched some of these and have some racial conscience, you’ll probably know where I’m going here. And the issue with it is that often this medias will portray real situations of racism and opression and prejudice, but all applied to white people. Like in Carnival Row, when going to work as a maid in a rich human house, our girl Cara Delevingne had to fight not to have her braids (which held a lot of significance in her culture) cut by her intolerant human mistress, because the braids were not “appropriate”. Got it? hahahaha what a joy

Look at her ethnic braids!!!

One of the reasons this happens might be to relieve a white audience of the burden of watching these stories and feeling what I like to call “white guilt”. Because, as we all know, white people were never very oppressed. Historically speaking, white people have always been in privileged social positions, and in an exploitative relationship between two ethnic groups, white people very usually would be the exploiters — the opressors. So while watching situations (that every minority would know to be very real) of opression in fiction, if these situations were lived by a white actor, there would be no real-life associations, because we have no historical parameter to associate this situation with anything in real life — if you are white. Thus, there is less chance that, when consuming one of these narratives, whoever is watching will question the "truthfulness" of these situations (because it's not "real racism", see, "they're just fairies"). It's easier for a person to watch without having to step out of their comfort zone, or confront the reality of real people who actually go through things like that. There's even a chance that this might diminish empathy for these people.

Once again, not saying this is specifically the case of the Clones, majorly because one of the main feelings you have when watching CW is exactly empathy for the troopers (at least for me, honestly, the galaxy could explode, I just wanted those poor men to be happy for God’s sake). But I’ll talk more about it later.

The thing is, the whole thing with the Clones, if you think about it, it’s not pretty. If you step on little tiny bit outside the bubble of “fictional fantasy”, the concept is very outrageous. They are kept in conditions analogous to slavery, to say the least. To say the more, they were literally made in an on-demand lab to serve a purpose they are personally not a part of, for which they will neither receive any reward nor share any part of the gains. On the contrary, as we saw in The Bad Batch, as soon as the war was over and the clones were no longer useful as cannonballs, they were discarded. In the (wonderful) episode 6 of the third season of (the almost flawless) Rebels, “The Last Battle”, we're even personally introduced to the analogy that there really wasn't much difference in value between clones and droids, something that was pretty clear in Clone Wars but hadn't been said explicitly yet.

In fact, technically the Separatists can be considered to be more human than the Republic. But that's just my opinion.

So, you had this whole army of pretty much slaves. I know this is a heavy term, but these were people who were originally stripped of any sense of humanity or individuality, made literally to go to war and die in it, doing so purely in exchange for food and lodging, under the false pretense that they belonged to a glorious purpose (yes, Loki me taught that term, that was the only thing I absorbed from this series). Doing all this under extremely precarious conditions from which they had no chance of getting out, actually, getting out was tantamount to the death penalty. They were slaves. In milder terms, an oppressed minority. And again, I don't know if that was the case, but I can understand why Filoni Inc would be apprehensive about representing phenotically indigenous people in this situation. Especially since we in theory should see Anakin and Obi-Wan as the good guys.

(and here I’d like to leave a little disclaimer that I believe the whole Anakin-was-a-slave-once plot was HUGELY misused (and honestly just badly done) both in the prequels and in the animeted series — maybe for the best, since he was, you know, white and all that, and I don’t know how the writers would have handled it, but ANYWAY — I believe this could have been further explored, particularly regarding his relationship with the Clones, and how it could have influenced his revolt against the Jedi, and manipulated to add to his anger and all that. I mean, we already HAD the fact that Anakin shared a deeper conection with his troopers than usual)

Yes, Rex, you have common trauma experiences to share. But anyway, backing to my track

As I was saying, we are to see them as good guys, and maybe that could’ve been tricky if we saw them hooping up on slavery practices. Like, idk, a “nice” sugar plantation owner? (I don’t know the correct word for it in english, but in portuguese they were called senhores de engenho) Like this guy from 12 Years a Slave?

You know, the slave owner who was “nice”. IDK, anyway

No one will ever watch Clone Wars and make this association (I believe not, at least), of course not. But if we were to see how CW deepened the clone arcs, and see them as phenotypically indigenous, subjected to certain situations that occur in CW (yes, like Umbara), maybe some kind of association would’ve been easier to make.

I mean, come onnnn I can’t be the only one seeing it

You see, maybe not the whole 12 Years a Slave association one, but I don’t think it’s hard to see there was something there. And maybe this could’ve been even more evident if they looked non-white. Because historically, both black peoples and indigenous peoples went through processes of slavery, from which we as a society are still impacted today. And to slave a people, the first thing you have to do is strip them from their humanity. So it might be easier to see this situation and apply it to real life. And maybe that could lead to a whole lot of other questions regarding the Clones, the Republic, the Jedi, and even how chill Obi-Wan was about all this. We might come out of it, as lady Ursula Le Guin stated in the fragment above, a bit different from what we were before we watch it.

Maybe even unconsciously, Filoni Inc thought we would be more confortable watching if they just looked white (and because of colonialism and all that, but I’m adding thoughts here).

And of course I don’t like the idea of, idk, looking at Obi-Wan and thinking about Benedict Cumberbatch in 12 Years a Slave or something like that. Of course that, if the Clones were to play the same role as they did in the prequels, to obediently serve the Jedi and quietly die for them, that would have been bad, and hurtfull, and pejorative if added to all that I said here. But the thing is that Clone Wars, consciously or not, already solved that. At least to my point of view, they already managed to approach this situation in an incredible competent way, that is giving them agency.

2.4 AGENCY AND INDIVIDUALITY

So, one of the things I love most in Clone Wars is how it really feels like it’s about the Clones. Like, we have the bigger scene of Palpatine taking over, Ahsoka’s growth arc, Anakin’s turn to The Dark Side, the dawn of the Jedi and rise of the Empire and all that, but it also has this idk, vibe, of there’s actually something going on that no one in scene is talking about? And this something is the Clones. We have these episodes spread throughout the seasons, even out of chronological order, which when watched together tell a parallel story to the war, to everything I mentioned. Which is a story about individuals. Clone Wars manages to, in a (at least to me) very touching way, make the Clones be the heros.

Can you really look me in the eye and say that Five’s story didn’t CRASH you like a full-speed train???? He may not have the same amount of screen-time as the protagonists, but his story is just as important as theirs (and to me, it might be the most meaningful one). Because he is the first to break free from the opression cicle all the Clones were trapped into.

His story can be divided into 6 phases.

1 - First, the construction of his individuality, in other words, the reclaiming of his humanity.

2 - Then the assimilation of understanding yourself as an individual of value, and then extending this to all his brothers, not as a unit, but as a set of individuals collectively having this same newly discovered value.

3 - This makes him realize that in the situation they find themselves in, they are not being recognized as such. This makes him question the reality of their situation.

4 - Freed from the illusion of his state, he seeks the truth about it.

5 - This then leads him to seek liberation not just for himself, but for all the Clones (it's basically Plato's Cave, and I'm not exaggerating here).

6 - And finally, precisely because he has assimilated his individuality and sought freedom for himself and his brothers, he is punished for it.

His story is all about agency. Agency, according to the Wikipedia page that is the first to appear if you type “agency” on Google, is that agency is “the abstract principle that autonomous beings, agents, are capable of acting by themselves” [4], and this abstract principle can be dissected in 7 segments:

Law - a person acting on behalf of another person

Religious - "the privilege of choice... introduced by God"

Moral - capacity for making moral judgments

Philosophical - the capacity of an autonomous agent to act, relating to action theory in philosophy

Psychological - the ability to recognize or attribute agency in humans and non-human animals

Sociological - the ability of social actors to make independent choices, relating to action theory in sociology

Structural - ability of an individual to organize future situations and resource distribution

All of them apply here. And this is just the story of one Clone. We know there are many others throughout the series.

Agency is what can make the world of a difference when you are telling a story about an opressed minority. Because opressed minorities do exist, and opression exists, and if you are insecure about consuming a fictional media about opressed minorities, see if they have agency might be a good place to start. So that’s why I think that everything I said before in 2.3 falls short. Because the solution already existed, and was indeed done. Honestly, making the non-agency representation of the Clones (the one we see in the prequels) to be the one played by Temuera Morrison, and then giving them agency in the version where they appear to be white, just leaves a bitter taste in my mouth.

And honestly, if they were to make the Clones look like Temuera Morrison, and by that mean, take more inspiration in the Māori culture, maybe they wouldn’t even have to change much of their representation besides their facial features. As I said in part 1, I am not by any means an expert in polynesian cultures, but there was something that really got me while I was researching about it. And is the facial tattoos. More precisely, the tā moko.

2.5 TĀ MOKO

Once again I’ll be using the Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand as source, and you can find the articles used linked at the end of this post.

Etymologically speaking,

“The term moko traditionally applied to male facial tattooing, while kauae referred to moko on the chins of women. There were other specific terms for tattooing on other parts of the body. Eventually ‘moko’ came to be used for Māori tattooing in general.” [5]

So moko is the correct name for the characteristic tattoos we often see when we look for Māori culture.

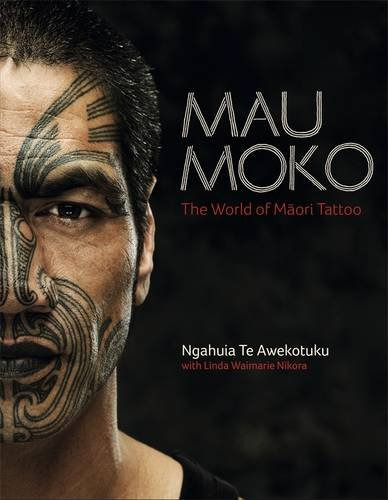

These ones ^. Please also look this book up, it’s beautiful. It’s written by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, a New Zealand academic specialising in Māori cultural issues and a lesbian activist. She’s wonderful.

According to the Tourism NewZealand website,

“In Māori culture, it [moko] reflects the individual's whakapapa (ancestry) and personal history. In earlier times it was an important signifier of social rank, knowledge, skill and eligibility to marry.”

“Traditionally men received moko on their faces, buttocks and thighs. Māori face tattoos are the ultimate expression of Māori identity. Māori believe the head is the most sacred part of the body, so facial tattoos have special significance.”

[...] “The main lines in a Māori tattoo are called manawa, which is the Māori word for heart.” [6]

Therefore, in the Māori culture, there’s this incredibly deep meaning attributed to the (specific of their culture) tattooing of the face. The act of tattooing the body, any part of the body, is incredibly powerful in many cultures around the globe. The adornment of the body can have different meanings for these different cultures, but all of which I've come into contact with do mean a lot. It’s one of the oldest and most beautiful human expressions of individuality and identity.

And in the Star Wars universe, the Clones are the group that has the deeper connection to, and the best narrative regarding, tattoos. In fact, besides Hera’s father, Cham Syndulla, the Clones are the only individuals to have tattooed skin, at least that I can recall of. And they do share a deep connection to it.

For the Clones, the tattoos (added to hairstyles) are the most meaningful way in which they can express themselves. Is what makes them distinguishable from each other to other people. Tattoos are one of the things that represent them as individuals.

And I’m not BY ANY MEANS sayin that the Clones facial tattoos = Moko. That’s not my point. But that’s one of the things I meant when I said earlier about the wasted potential of the representation of the Clones (in my point of view). Because maybe if it were their intention to base the culture of the clones after the polynesian culture, maybe if it were their intention to make the Clones actually look like Temuera Morrison, this could have meant a whole deal. More than it’d appear looking to it from outside this culture. Maybe if there were actual polynesian people in the team that designed the Clones and wrote them (or at least indigenous people, something), who knows what we could’ve had.

Even in Hunter’s design, I noticed that if you take for example this frame of Temuera from the movie River Queen (2005), where we can have a closer look at the design of his tā moko

Speaking purely plastically (because I don’t want to get into the movie itself, just using it as example because then I can use Temuera himself as a comparison), see the lines around the contours of his mouth? Now look at Hunter’s.

I find it interesting that they choose to design this lines coming from around his nose like that. But at this point I am stretching A LOT into plastic and semiotics, so this comparison is just a little thing that got my attention. I know that his tattoo is a skull and etc etc, I’m just poiting this out. And it even makes me a little frustrated, because they could have taken so many interesting paths in the Bad Batch designs. But instead they choose to pay homage to Rambo. And I mean, I like Rambo, I think he’s cool and all that.

Look at him doing Filipino martial arts

But then, as we say in Brasil, they had the knife and the cheese in their hands (all they had to do was cut the cheese, but they didn’t). Istead, it seems like in order to make Hunter look like Rambo, they made him even whiter???

2.6 SO...

Look, I love The Clone Wars. I’m crazy about it. I love the Clones, I love their stories and plots. They are great characters and one of the greatest addings ever made in the Star Wars universe. They even have, in my opinion, the best soundtrack piece to feature in a Star Wars media since John Williams’ wonderful score. It just feels to me as if their narrative core is full of bagage, and meanings, and associations that were just wiped under the carpet when they suddenly became white. It just feels to me as if, once again, they were trying to erase the person behing the trooper mask, and the people they were to represent, and the history they should evoke.

I don’t know why they were whitewashed. Maybe it was just the old due racism and colonialism. Maybe it was meant for us to not question the Jedi, or our good guys, or the real morality of this fictional universe where we were immersed. But then, was it meant for what?

The Clones were a metaphor for what?

(spoiler: the answer still contains colonialism)

Thank you so much for reading !!!! (and congratulations for getting this far, you are a true hero)

SOURCES USED IN THIS:

[1] Ursulla K. Le Guin, 'The Left Hand of Darkness', 14th ACE print run of June, 1977

[2] Dave Itzkoff, 'Being Boba Fett: Temuera Morrison Discusses ‘The Mandalorian’', The New York Times, published Dec. 7, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/07/arts/television/the-mandalorian-boba-fett-temuera-morrison.html (accessed 15 September 2021)

[3] Bruno Claessens, 'George Lucas' "Star Wars" and Oceanic art' , Archived from the original on December 5, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20201205114353/http://brunoclaessens.com/2015/07/george-lucas-star-wars-and-oceanic-art/#.YEiJ-p37RhF (accessed 15 September 2021)

[4] Wikipedia contributors, "Agency," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Agency&oldid=1037924611 (accessed September 17, 2021)

[5] Rawinia Higgins, 'Tā moko – Māori tattooing - Origins of tā moko', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/ta-moko-maori-tattooing/page-1 (accessed 17 September 2021)

[6] Tourism New Zealand, ‘The meaning of tā moko, traditional Māori tattoos’, The Tourism New Zealand website, https://www.newzealand.com/us/feature/ta-moko-maori-tattoo/ (accessed 17 September 2021)

#THE CLONES DESERVED BETTER WE ALL KNOW IT#star wars#star wars animated series#the bad batch#clone troopers#tbb#mandalorian#colonialism#whitewashing#UnwhitewashTBB#semiotics#visual culture#cw#the clone wars#star wars the clone wars#rex#hunter#the bad batch hunter#dave filoni#temuera morrison#maori culture#moko#anakin skywalker#star wars rebels#obi wan#capitan rex#cody

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever headcanon your favorite character's "bedroom activities"? 😏

Oh absolutely

Ok I put a readmore just to be safe

Gwen knows the textbook stuff about sex that you learn in health class, like the stages of neonatal development etc, but Kevin knows more about the practical stuff that they don’t teach in school, and he’s thrilled that he knows more than her about something for once! To be more specific I think he knows how to please a lady and I get the feeling Gwen went to a catholic school at one point and she doesn’t really masturbate ever, so Kevin kinda showed her a whole new world lol. I also think Gwen’s not really good at giving head but she tries and Kevin’s supportive but Gwen doesn’t watch porn so she has no idea what she’s doing.

Kevin definitely lost his virginity way before he started dating Gwen and that’s part of why he’s nervous she doesn’t like him- you know, that chewed gum metaphor that was probably the only thing he remembers from his public school sex ed before leaving earth.

So Argit fucks by the way. You can’t tell me he doesn’t. You ever have pet rats? They’re horny little bastards and Argit is no different.

I also think Argit’s done sex work, and while he prefers to make money through illegal weapons dealing, every once in a while he does what he can to pay rent.

Rhomboid fucks because he’s always saying dumb shit like “nice tits can I see them” and sometimes it works out. He’s confident I guess.

Octagon also fucks occasionally but he’s more repressed because, you see, in Ben 10 galactic racing he and boid mention they went to at least elementary school and I bet the public school system they went to is analogous to the schooling in the American south that tells kids that all gay sex leads to aids, so that’s what he was taught. He’s gay but super in the closet and tries to make things work with women.

For all her previous kids ma vreedle tried to teach them that masturbation will give them hairy palms or whatever but whenever pretty boy, like, touches a waitress’s ass or something she’s like “awww my little angel is growing up how sweet!” And if the waitress gets mad she yells at the manager for “disrupting her little angel’s development” or something.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interpreting History

“There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it.”

This quote can be interpreted in many different ways, but there’s no denying that it emphasizes the importance of preserving history and spreading the lessons that history teaches us.

One of the most significant quotes I pulled from the textbook is

“Any interpretation must be presented with the utmost attention to personal and professional integrity to assure that the recipients (clients and customers) of the interpretive effort are presented with the truth." (Beck et al, Chaper 15, Inerpreting History)

In summary, this quote emphasizes the importance of keeping history intact and authentic. One of the most important aspects of history is that it allows us to come to our own conclusions. You are presented with a story, and each person has the ability to interpret it in their own ways. From the telling of the same story, each person in the room can take a totally different message. This is why it’s important to keep story is as close to the original event as possible. Throughout time, details of stories get changed especially when there’s little to no records and the bulk of communication happens through oral history. It’s also important to note that you will get a different story depending on the perspective you are being told from. For example, when we look at World War II, Americans will tell a very different story than Germans. But as interpreters we have a responsibility to tell things from an unbiased perspective.

“We use history as a tool for reflection and comprehension. When we listen to stories of the past we seek a better future.” (Beck et al, Chaper 15, Inerpreting History)

This is where the true value of history lies. When we hear stories of the horrors or triumphs of the past generally, we apply what we learned from that to our lives. Most of this comes from the feelings that these stories evoke. For example, when we hear of something horrible such as the Rawandan genocide we sit with the way these horrors make us feel. From that feeling we learn whether or not we’d be okay with that happening again.

My favourite part of this quote is the train metaphor, it sums up the quote so beautifully and greatly helps the reader understand the message. It took me a couple times to fully understand what the author was saying by this. I believe that they simply mean that even though history happened in the past we carry it within all of us in the present. The lessons learned through history can be applied to the present and future to guide us all to a better life.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., & Knudson. D.M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore-Venture.

1 note

·

View note

Link

It is appropriate to begin to understand yourself as a combatant in a war that you may only be dimly aware is being waged. You are in fact operating in the battlespace at this very moment. Consider the implications. Consider that you are marked.

Your self-identification as a combatant, or not, is irrelevant. You have been declared an adversary of the True and Just cause of Democracy. The adversary in this war is a floating signifier anyway, purposefully undefined. Don’t go searching for your name in any database (though you may find it there). The adversary can be anyone, at any time. He is a cipher. The territory under contestation is perhaps even less well-demarcated. As a matter of physical geography, it may be said to not exist at all. And yet we are in it. We are fighting it. The war is on.

…

The proclamations of those declaring this war leave vanishingly little room for uncertainty. Their rhetoric is becoming more explicit every day. No one can deny this. Even the soberest mind must acknowledge their increasing belligerence.

“In the aftermath of the insurrection on January 6th…” This is by now a common refrain. Oliver Stone also said — or maybe it was Homer — that every war must start with an event. No doubt they have been waiting a long time to declare their intentions, but now they have finally found their casus belli. When they say that January 6th is their 9/11, this is what they mean. It may seem that the incoherent, spontaneous nature of what happened at the Capitol might vitiate such lofty comparisons. But for the regime, all the better. The ambiguity allows for the widest possible net to be cast over their enemy, as John Brennan would have it, the “unholy alliance” of “religious extremists, authoritarians, fascists, bigots, racists, nativists, even libertarians.”

Tag yourself. Not that any of these terms matter. Again, they are floating signifiers. They mean everything and nothing. Importantly, they mean you. They mean me.

Brennan of course is not alone. Just days after he delivered his ominous remarks, his CIA colleague Robert Grenier wrote an op-ed for the New York Times declaring the forces responsible for January 6th — again, never clearly defined — to be regarded in the same terms as ISIS and Al-Qaeda. He spoke of an ongoing “domestic insurgency” and the need to put it down with the same degree of force as his own Counterrorism division applied to jihadists in Afghanistan and Iraq. Stanley McChrystal echoed nearly identical sentiments within the week. Javed Ali, whose bio reads less like a human being’s than the formless node of the Foreign Policy blob that he is, writing for the Security State rag the Cipher Brief, in an article indicative of the borg-like mass to which he belongs, suggested the “New Right,” which includes the usual litany of conservative bogeymen all the way up to those with such alarming views as, for example, being “pro-2nd amendment,” warrants the creation of Domestic Terrorism laws that would include a domestic surveillance program mirroring the British Security Service to monitor online speech and circumvent Constitutional protections against prior restraint.

…

But beyond the morality play, and the heady drama of the fate of Western man, it’s Lind’s attention to the form and processes of war that are most relevant here. In the 4th Generation war everything is muddled and inexact. Military and civilian life merge into a fluid, indivisible state of mind and being. Everywhere is a potential target. There is a kind of atemporality to it, too. Individual battles never clearly begin or end. Much of it is fought in the digital ether. Fixed points of planning and operation become obsolete, too easily identified and subverted. There are questions about the status of the war itself, and it is often an advantage of the stronger side to plausibly deny there is any war at all.

In the end, Lind resolves these ambiguities in no uncertain terms. His 4th Generation civil war, however abstract and indistinct, eventually reverts to the classic mode. Its wages are measured in lives lost and territory gained. His heroes shoulder their rifles and vanquish their enemies in pools of their own blood. A Christian nation of local, artisanal economies blooms in a Jeffersonian spirit of revitalization. It’s a chilling read, the Minecraft meme brought to life.

But it is in this latter reversion to classic military confrontation where Lind’s map loses touch with the territory we are actually living in. We are not in a war that accommodates armed conflict, nor should we want it to. Let me repeat that for the minders reading this: violence, kids, is not the answer to our current problems.

Rather, some have speculated that what we are living through now is better described as 5th Generation war. A fifth-generation war is one where the ambiguity stands, even more so, but is never quite so manifestly resolved. (This Twitter thread from last October by anon user Reality Gamer provides a useful summary of the concept.)

This war, if we are to adopt the model, which I believe we should — and for which there is much compelling evidence — is fought almost exclusively over ideas. As in Lind’s concept, everything is indistinct, everything is abstracted right up to the point of nonexistence. War and peace, civilian and combatant, battlefield and neutral territory all collapse in a morass of ever-present meta-conflict. The conceptual boundaries between debate, activism, and terrorism are themselves the site of primary engagement. What matters is not who controls the streets in the wake of a clash of forces, but he who decides that the clashes are “mostly peaceful” and their own soldiers just an “idea.”

That is, it is a war over narrative control. Instead of armed battalions, it’s a loose affiliation of entrenched interests — deep-state operatives, media conglomerates, NGOs, lawfare apparatchiks, academics, the many-sided face of globohomo — controlling information networks to shore up their resources and guard against whoever they identify as a threat. These threats and the methods to neutralize them never have to be explicitly stated or shared across the network. In fact, it is better if they aren’t. It obviates the problem of what Edward Luttwack calls the “paradoxical logic of strategy.” Instead, the system, like a black box AI, manages its agenda according to its own hidden processes.

And what is this agenda exactly? To enforce the conditions of consent.

…

What we are experiencing now is something quite different, the regime on war-footing, no longer confident enough in its own legitimacy to dare put that legitimacy to test. And as is the case for all regimes in such a weakened, sclerotic state, though the strategies and tactics are more diffuse and perhaps less blunt than in eras past, we are treated to the same predictable response: crush dissent, flatten and homogenize the culture, divide and alienate the population from one another, declare a monopoly not just on knowledge and belief, but on the asking of questions themselves. Vaclav Havel, writing on the withering Communist regime of his native Czechoslovakia, described this final desperate effort to coerce the population into consent as the “nihilization of life.”

…

When vast swaths of non-compliant Americans are declared domestic insurgents, it behooves us to conduct ourselves accordingly. This is not to say that whatever might broadly be called the ‘Dissident Right’ ought to assume a defensive crouch, or retreat into passive quietism until the regime exhausts itself. Though we may be in the midst of a 5th Generation war, some of the old rules still apply, and the insurgent, however diminished, however outgunned — metaphorically, of course — has certain advantages he can make use of.

Another war historian, David Gallula, describing the Cold War spasms breaking apart and reforming the global map after World War II, wrote in 1965 what has become the textbook on the nature of insurgencies. Gallula was a man of his time, and most of his examples are superficially outdated, Communist rebels from Greece to North Africa to Southeast Asia asserting themselves with greater and lesser effectiveness throughout the Third World. We are not Communists, and this is not the Cold War, no matter how much our State Department might wish it were so. Nonetheless, Gallula provides a few key insights that broadly apply to our fight, and that we ought to keep in mind as we ask the question of what comes next.

To begin, the site of contestation in the 5th Generation war against our decrepit regime is not firstly the halls of power, certainly not the Capitol building, and not even really the formal political arena at all. Borrowing from Yarvin, I’d echo that Republican electoral victories are not sufficient for breaking the regime until the Republican candidate sees himself as an outsider prepared to tell the regime that it must submit. Still, contra Yarvin, winning political fights is good, where we can get them, and there are ways of engaging in local politics, especially, that may achieve certain desired effects. But ultimately, political victories are downstream of a more fundamental fight, which is winning the support of what Gullala coarsely calls “the population.”

…

That is, the normie must be given a cause. This cause must exist outside the political paradigm within which he has been accustomed to understanding these conflicts. Scott Alexander is not entirely wrong to propose that Republicans wage a “class conflict” against the strata of elite sense-makers who despise them. It is indeed a righteous cause, and an effective message. He is wrong however that Republicans, as such, ought to do this. No. This is not a partisan conflict against Democrats, though there is much overlap. This is a conflict of insurgents against a failing regime. That is the way it must be framed and its campaigns prosecuted.

I am cautiously optimistic that Americans understand this cause and the nature of their enemy instinctively. There is no denying the rot at the heart of American life, of Western life. There is no denying the ever-presence of the bugman and his sickly designs for us. The energy leaking out against this is everywhere in sight. However misdirected, however frenetic and decoupled from meaningful objectives, a spirit of disobedience obtains. They feel the quickening incursion of the public life into the private, no doubt accelerated by Zoom World and the bright eye of our screens watching and recording our every thought. Americans can feel caught in a straightjacket of preference falsification and coercive moral decrees, the stiltifying HRization of their inner universe. What a bleak and limited existence!

…

Finally, as Gullala observes, an insurgent movement in its infancy is necessarily small. It is necessarily weak. It needs time to build. It cannot on day one confront the regime on its turf and presume to use the regime’s own weapons against it. Again, this is not to advocate for quietism, but rather to recognize the limited usefulness of operating within the domains of social and political activity the regime already controls. You are not going to take back the universities or Hollywood or the news desk. Infiltrate these places and expose them for what they are, but to destroy them rather than to save them.

Before anything else, we must build a culture of our own. Any meaningful insurgency will be downstream from its capacity to imagine. Direct action politics will flail and follow, rather than lead, if it is not tethered to the kind of self-understanding that can only be achieved through art. The regime understands this, if only intuitively, and the ban waves and censorship are an attempt to tear apart the communities where this art can be cultivated and shared. But they are not yet omnipresent. They have not yet, as in Havel’s Czechoslovakia, managed to altogether “nihilize life.” There are cracks still to penetrate. There is, deep in the American soul, a resilience that is not yet extinguished. Build the communities, forge the relationships, online and off, where this resilience can manifest and triumph over the enemy and its machines.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Questions Tag Game

Got tagged by @outcastcommander :DDDDD Thank!!!!!

Rules: Answer 30 questions and tag 5 blogs you are contractually obligated to know better. HI I’M ACTUALLY REALLY SHY SO I’M NOT DOING THAT LOL I’m just gonna say, if u wanna do Intro and see this, go for it, and also bonus if u r Friend, absolutely feel free and also say i tagged u bc Yes Friendship.

Name/nickname: Elaphae, Ela is most common (and great!! i love it fjdklajs), some people on the swtor art server called me ‘inquis’ a couple times ljfdklas.

Gender: Nonbinary :DDD

Star sign: Virgo-Libra cusp :3

Height: 5’4 WOOP i am Short

Birthday: September 21

Time: 12:48 pm >:3

Favorite bands: Green Day, Volbeat, The Longest Johns, Alestorm… a lot more.�� I’m a nerd lol.

Favorite solo artists: uh h hhhhh o-O there are Many. Aurelio Voltaire is pretty solid lol. Good for the heart. Also, I can’t listen to too much of his stuff bc it gives me a Crisis, but Bo Burnham. Shit’s a Bop.

Song stuck in my head: The theme for the uruk-hai from lotr lol

Last movie: Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers

Last show: fjdklasj i don’t watch tv lol, i can’t make my brain sit still for it. Gotta be Interactive.

When did I create this blog: uh, shit, when WAS that?? WOW 2014. 3 more years and I’ll have spent a decade on tumblr. Which is WILD.

What do I post: things that make me happy ;v; mostly star wars and dragon age, and Assorted Random Shit i think jfdlkfjd. I don’t actually know what my blog makeup is but it Sure Is Something.

Last thing googled: ‘the song from lord of the rings when saruman shows off the uruk-hai’ lmfaoooo, i couldn’t remember the name of it so i went looking.

Other blogs: HOO BUDDY okiedoke: @haospart (art blog), @swtorcompanionsgoofin (swtor blog), @lyriumdisaster (dragon age blog, which i’ll get back to once i’m done on the swtor end of this bioware pingpong table of interests, and then i’ll be hopping BACK to swtor bc it IS a pingpong table), i have studyblr that I Never Fuckin Use and have only posted on in the past 2 years to go ‘what the fuck why do u people keep following me’ bc I LITERALLY HAVE NOT TOUCHED IT IN LIKE 2 YEARS why does it keep gaining followers, and then a few like, ‘no don’t look me i’m Embarassed’ repositories jfdklsjaf.

Do I get asks: Very rarely, but yes!! Lmfao usually when i go ‘GIVE ASK PLS I LOVE ASK’ and people are reminded that i am, in fact, a very friendly marshmallow who does not mind interaction and also Definitely Craves people asking questions about my stuff fjdla.

Why I chose my url: This is kind of a convoluted thing, but like, the easy version is that it’s the name of my trooper on the leviathan server (now called Aea out of the game bc they were supposed to be my self-insert but then they escaped into the woods and developed a storyline for themself). The LONG thing is that I have an oc named Regia Elaphae, who I modeled after pnigophobia, the fear of choking or being smothered, and I made her snake-themed. Rex is the latin word for king--for king snakes--which i swapped to regina and then took out the n bc ‘Regina’ didn’t fit her, and Elaphe is the genus for rat snakes, but i found two ways of spelling it so i spelled it Elaphae, and when I got into swtor I decided to use Elaphae in reference to myself. I replaced my old url with this one after i started playing that trooper of the same name, bc my old one was :I . I was into hetalia in middle school, and homestuck, and when I got on tumblr that followed me into my url. I’m not into hetalia anymore, or anime at all, and homestuck fell off my radar into the ‘i’ll go “hey i know that” if i see it, but i’m not in the fandom anymore’ pile. For the longest time my blog description was ‘it’s been 5 years and i still haven’t changed my url’, but it was time for change fjdklasfaj. It’s better this way.

Following: 953 (it was over 1300 but i did some clearing out of my follow list a month or so ago lol, mostly of people who haven’t been online in 6 years)

Followers: 616

Average hours of sleep: 7 and a half hours, if i want to be Functional

Lucky number: 19 :D I love 19, it’s always been my lucky number, always will be.

Instruments: I don’t play much, but I can sing and also I can play beladi on the doumbek.

What am I wearing: Fox onesie lol. I wear basically nothing else at this point in my life.

Dream job: i mean, ideally i could just Not and vibe fjdkla. But i mean like, i guess something working with my hands. I’m in college to get a degree in french, and my next step after that is to go to trade school, to get smth that’ll make me money so i can keep doing Nerd Junk and also learning bc i like, actually really like school lol.

Dream trip: I want to go back to Rennes. I miss it. It was awesome, and, hilariously, I miss being able to get a burger that isn’t Drowning in its own grease. America doesn’t know how to do healthy burger that tastes good. Europe knows what’s up tho. I also miss being able to like, have just a pitcher of room temperature water next to a cute little glass and have it not be weird. The cups are too big in america, i drink so much less water bc it’s just too daunting. I’m dehydrated constantly. Also i miss the METRO. I loved the metro, loved nyooming along in the trains, wandering around the central part of the city, it was cool.

Favorite food: Eel!! Eel’s tasty as fuck. I love it.

Nationality: American

Favorite song: o-o uhhhhhhhhhhh, i have no idea lol. I listen to so much random shit. lol according to my spotify 2020 rewind it’s Starlight Brigade, from TWRP and Dan Avidan.