#i could write an entire book on how unfamiliar french people in medias seem to actual french people

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

question for alpha:

what do you make of the stereotype that the french are cowards?

do you believe that people are straying away from this stereotype?

ive been getting into fandoms where french people are written like this and i would like to hear some perspective.

thanks

oh boy, *cracks knuckles*

so. i will be honest with you. i do not know where this stereotype comes from. or well i have a very vague guess but im not sure. i asked people around and they too just went big shrug. my only source of confirmation has been wikipedia.

see my closest guess here is that americans consider our surrender against the nazis in WWII to have been a cowardly thing or something, i dunno. weird takes on europe going on here and they seem to think we didn't fight before said surrender just cos only 46 days or sth bc apparently, blizkrieg who ? never heard of her or the absolute devastation they laid on my people. it also strikes me as a not particularly international take bc i genuinely never had heard it before being on socmedias used by americans. hell, the wikipedia page on french stereotypes lists it as exclusively american. this would match up with americans' tendency to equate cowardice and bravery as something the domain of war, which they care a lot about, whereas we just simply have other concerns, no offense.

anyways, see the stereotype we french people have about ourselves (and that actually is kinda relevant about reality), and a lot of people too, including americans, is closer to this-

thats french for we yell all the fuckin time and make a ruckus about everything ever. les gueuleurs quoi.

although support of unions is lessening due to the current political crisis we have been stuck in for god only knows how long, the french has a large culture about revolution, unionizing, human rights, left wings politics and shit like this. it may or may not be war every fuckin day at my home actually because of the union stuff (not shitting on unions shitting on my dad's terrible work homelife separation and his tendency to yell at the TV every night, bc apparently the TV is a conversation partner but your kid asking you to stop screaming isnt).

we just are known to protest a lot and backtalk to politicians and shit like that. and it seems that the cowardly stereotype is lessening because people on social medias are starting to point out, hey ! this isnt being lazy actually. the french is actively fuckin. blocking roads and burning shit and all that and being cunts to their politicians, and they have universal healthcare and a decent retirement system which we are realizing we fuckin wish we had in this dystopia of a life. maybe theyre doing sth right. (and well theyre right unfortunately the french itself is slowly forgetting that.) this aside yeah recognizing that making a fuss about your rights is a good thing the french do is kind of incompatible with the idea that the french are cowards, especially with the recent crisis of the gilets jaunes where people protested tirelessly despite actively getting wounded and arrested and disabled for life and killed by cops. and it really has been like this for a good while too, since industrialization or so, when capitalism became widespread.

so in other words. subjectively ? i do think the stereotype is unbased/pretty darn recent and mostly a cultural difference, and nor can i really explain it besides blaming Capitalist Propaganda. i also do not know if objectively such stereotype is getting less support, but subjectively, from what ive read around and so on, people seem to be a bit catching up, and seem to be accepting that unionizing and strikes are NOT a laziness thing but genuine bravery when facing a system that is strikingly inegalitarian and running well oiled with the blood of the people.

take this as you want. i have to admit this is a bit personal because americans' agressiveness towards the french have genuinely made me feel like i was unwelcome online, ive seen people wish that france would sink under the sea or specifically would get nuked, with no single hint of irony whatsoever. and among the animosity found here, ive always keenly felt the difference between what was considered hardworking and invested for the french, and what was considered lazy and cowardly for americans and the faint smell of capitalist propaganda hiding behind it all

Addendum: So yeah that stereotype about the french being cowards who surrender immediately, of course it exists in Germany too. And it's also most likely due to WW2 and propaganda related to that.

- Aschen

True to the post-Soviet world as well.

- Ray.

#langage language#pardon my french; i am verbose#i could write an entire book on how unfamiliar french people in medias seem to actual french people#spy is an odd case; ask me about him#one day ill also rant about fake french accents; including spys#anyways hatred of the french online is weird and strikingly frequent and i basically dread going online every time sth big happens#i wont mention anything bc if i do people might go Actually You Deserved It#and i dont wanna get that#hope i somewhat. answered sth satisfying to you#not tf2#The Council has spoken

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

the teen show genre is back. that it had announced it’s grand return at such a time of deep uncertainty and unimaginable loss, especially for an entire generation of teenagers, is relief, respite, and a necessary and urgent gain. there is nothing but gratitude for this...for its intended audience and for those of us who will live vicariously through the lives of the kids, for those of us who will watch, and walk with the kids. for someone like me who longs to feel strongly about a story enough to write again.

despite my ‘desperate begging’ for the return of the youth oriented show. i did not picture this. in my defense, i did not know about this story at all. now, when i did learn the gist of the story, i did not expect much. it is, after all, a trope we’ve repeatedly seen in practically every language. in my defense, again, i would have found this show, and watched it anyway, in support of the network, probably be mildly entertained, slightly amused, and successfully distracted. and that would have been enough. i was bound to find this show, though during a deep dive into the youtube rabbit hole, chancing upon a japanese doll and an american cutie, realizing the creative team for this show is that creative team. my favorite creative team. i was sold.

i knew i was going to love this show enough to write. the question is, how? do i live tweet, take notes, and write a post for every episode, or do i live tweet take notes, listen, take notes and write one big post at the end of the series? judging by how much detail i know this team puts into a story in the form of metaphors, seeds, pay offs, connection and clues, clearly obvious in this first episode alone, this calls for an episodic post, for the peace of my own nerdy, detailed obsessed mind.

it is worth repeating that i haven’t read the book. this focuses on the series alone. no references, no comparison to its source material.

and it begins. oddly so.

first, a note on the casting: my attachment to a show is dependent on my attachment to the cast of the show. i spent the weeks and months leading up the pilot episode learning as much as i can about this refreshing cast of newbies. i’d been watching rise since it began, and so it wasn’t difficult to develop a soft spot for the five rise kids who are part of the show. as for the rest of the cast, their interviews and streams are all surprisingly impressive. i always like to say ‘walang patapon sa mga batang ito.’ none at all. they are all so special that i am in awe of how many gifted children are in one batch at one time, in time for a show like this. the teen show slot was vacant because it was waiting for these specific kids.

everyone who was given moments on this episode made the most of their moments. episode one’s surprises were criza, who is a natural. i am just grateful naih was able to use all of criza’s kulit energy. gelo, i’ve known is funny, but it wasn’t until i saw him in character that i realized just how hysterical he is. i enjoyed his interaction with ysay, i am wondering if there is more of that. v no longer surprises. i find that she is incredibly underrated still. i love that girl. fictional life sometimes clouds my judgement, ever so slightly, but these mean girls, are the mean girls i would cheer for. i’ve just been enjoying the girls’ junket interviews so much that it is also a joy to watch them in character. aimee is spunky, sophie is incredibly poised. khloe is a joy to watch, and ash just fits in, dalia...i have never seen a girl with such strong presence and beauty since hopie. i have never enjoyed watching a local queen bee as much as i feel i would enjoy, and hate to watch kim. dalia is amusing to watch too, so there’s that. joao, you know i have always found reliable and competent. limer, i am just happy an actor like him is in a show as big as this. kaorys is my in on this show. they are favorites. i adore them. she registers well on camera, and rhys is music to my ears, and has such an animated, expressive face. i cannot wait to watch their subplot and write about them in detail. i am attached to these kids. i know they are going to be a joy to watch.

melizza, melizza deserves her own paragraph. i first paid attention to when she was answering those miss universe questions on rise, and my jaw literally dripped at how intelligent she is. that intelligence shines through in her portrayal of elle. she is self-aware, and aware of her co-stars in a scene. she is conscious of where she is in a scene. she does she is a realiable actress in that there is no fear that she will break character it doesn’t have to be her scene, but i cannot help but watch her. she isn’t a scene stealer, but she is always acting, always reacting. she gets the assignment: from speaking french to playing a nuanced mean girl whose meanness, is as she understands and plays elle, stems from fear, from being threatened. i actually love that. there is no real villain in this story, just kids navigating unfamiliar, ugly, strange feelings, with limited ways to express these feelings. melizza gets it. i said i am a melizza fan now. i mean it.

donny and belle individually: i had known of donny, watched him long enough to know him, and who his family is. since he started mostly on social media, this ate didn’t quite get the appeal. no offense, it’s just a generational thing. haha! when he started acting, he was like most greenhorns to me, appeal understandable, charming to an extent, but with still so much to learn. i missed his last acting stint before this show. i did not watch jpd.

belle is a going bulilit alum. that’s all i really need to know to trust the casting. i wasn’t a fan yet. i had no clue about the story so i did not know just how much weight the character carried, but by virtue of the fact that she’s been acting the longest out of the ensemble, i knew she knew what she would be doing. i knew the management knew what they were doing when they casted her. belle as the focal point of the story lends such an air of confidence that the story will be told well and that the necessary intimacies will be handled with care. belle’s ability to transform would make max’s arc effective. i did not watch jpd. i had heard about it.i had heard it was surprise. ‘the ending part...’ it was all too familiar: lizquen, circa 2012, must be love: ‘the ending...’

it was completely blind, complete trust.

their casting made me momentarily forget that there were multiple rounds of auditions, from which the each of the cast were carefully picked. it just seemed so random, that is, in context of say, kaori and rhys that could count kuya’s house as part of their shared history. so much of my acceptance of this new pairing depended on how much i trusted the team, and how i knew they worked. i then consumed any and all donbelle content i could find, which, at that time was painfully lacking. imagine the excitement when that first general assembly officially kicked off the hih junket, from then on, they started to grow on me.

these are two calm, cool, collected kids, with a kulit side for sure, but they both take their sweet time. there is a formality and wide open space that was begging to be bridged with these two. there were times i would will myself to see it. theirs isn’t an instant explosion of chemistry, but a sustained afterglow. once that was clear, the goal of sustaining this partnership for however long, how many other stories they can tell together, also became clearer.

it was the tv patrol interview by the lockers that had me sold. it was him joking that they were already married with three kids. it was the way he looked at her in that interview, the way he still does, with donbelle, it’s all the little, quiet things. i don’t know how to explain it, but if they were to jump into the emotional deep end together, i have no fear.

now, back to the beginning which i thought was strange. a recap of what i imagine is the entire first season, artistic as it may be, is one huge spoiler. i realized, this is based on a book. those who’ve read it obviously know what’s going to happen. such opening is meant to set the mood. it’s an invitation to emotionally invest. it’s safe to say, it accomplished those two goals, but i feel as though there is more to that opening. as someone who is clueless about the source material, it reassures that it doesn’t matter what we know, or don’t know, because this is less a story of ‘what?’ and more a story of ‘whys?’ and ‘hows?’this takes me back to the first general assembly when comparisons to the meteor garden, boys over flowers were brought up. i understand the comparisons, but now that the first episode has aired, i feel so strongly against it.

this introductory montage is proof that it is not about the pieces of the story, but how the pieces are moved around to tell a story, to give us a fresh new perspective of a trope, starring stereotypical characters. the story is told in retrospect, with our lead looking back, taking all the pieces of the whole apart, rather than building the story as she goes along (which is incidentally how i like to take in stories).

the introductory montage is a device that allows a more expanded storytelling. the story is told from max’s point of view. it’s a story of how she sees things, this makes her an unreliable narrator due to her blind spots and clouded judgement. as the story goes along, the audience sees that it is not only max’s story, it is deib’s as well, and the rest of the characters’ stories, max only sees the bigger picture in retrospect. because i am such a nerd, imagine my kilig when i realize why that choice for an opening was made? i may have screamed.

notes, questions, favorite moments.

belle’s ‘sigurado,’ the first 4-5 notes of the hooked sprinkled throughout the episode.

on the road: the transition from max on the trike and deib, in his car rushing through a countryside road, if that was clean editing, i’d celebrate it...that the two people were on the same road at the same time travelling different directions is the most clever storytelling moment thus far. i love when seeds are planted and pay offs are grand. it was hardly a meet cute, but it was some intense head on collision. okay, i got it just then, the accident was a literal representation of their metaphorical colliding. it was a lot of things for her: irritation, wonder, disturbance, fascination, disruption. it was a complicated mix for him too, except clouded by the rush of having to be somewhere else other than that moment. charged. electric. spark. lightning that escaped him. (yup. more on that later).

this encounter begs the question: what was deib doing there? why was he in a rush?

the airport scene: ‘hinihintay ka na ng kapalaran mo.’ a beautiful verbal sign of things to come.

meeting daddy: it’s what uncertainty does to max that i find so disarming her fidgeting the heart shaped pendant close to her chest, summoning said heart for strength, and grace, counting on the assurance of its familiarity.

the car conversation with dad: still disarming. charming. curious. that the necklace from which hangs her heart shaped confidante was actually her dad’s gift to her mom. how heartwarming is the thought that the one thing that makes her feel close to her mom is actually from her dad who she is meeting for what i assume is the first time? i think it’s a beautiful irony.

the dinner table scene. the family dynamic it established. elle’s french, max wrestling with the chopsticks on the side.

sleepless max. her hidden vulnerability, and with whom that vulnerability finds comfort. who is babu?

max’s fist at the school entrance, and elle calling her out on it.

the cafeteria scene, and how that whole moment is the selling point of the story - brave max who does not care for the social rules of her new school standing up to the bully who happens to look the way he does. i won’t say she’s unaffected, but at that point her view is clouded with the injustice she just witnessed, that is until they recognize each other. as a side note: ysay and lorde’s interaction made me smile.

the aftermath. max has now caught the attention of the whole school, she has caught the attention of the mean girls so much so that walking down the halls is social suicide. when aimee confronted her, (sophie did so well!) my eyes looked for elle’s eyes. there were layers upon layers of emotion there: shame, hesitation, confusion, fear, maybe anger, there was a flash of her wanting to connect too, or did i just imagine it?

the gym scene with all the boys. it’s probably my favorite...not really, but it’s the scene that gave me so much, the scene that proved to me that this is more than just a simple, one dimensional teen show. this one moment spawned so many fan theories online that i have yet to read. it’s interesting when we cross that bridge, but to me for now, it is from this point up to the debate that kind of turned the tables, and gave the story a sudden depth that’s unexpected. it made the audience pay attention to deib as well, that this is as much his story too. and on the aspect of change, in one interview (i can’t remember which one), i remember belle describing max as someone who wants to change the people around her, and through that, she is changed as well. i did not understand what she meant at that time, until this. and the debate.

the debate: i just love the debate, simply because i love words, but long-winded dialogue like that is risky especially on a show like this. i loved it. i loved the rhythm, poetry, and point of it. i love how layered it is. i loved how comfortable was delivering his lines. i did not cringe, which just means he has gotten better at this whole acting thing, and it’s always a joy to watch someone breakthrough. this moment was necessary as a springboard to the next scene, to show that the rivalry isn’t just a physical one, but a rivalry of the minds too. (i enjoyed that that was pointed out in one of the kumu lives) this is also one of the scenes that proved what the introductory montage was trying to establish: that max is an unreliable narrator, that there are things she doesn’t see. i would say the tables have turned, and it has, but we also discovered that deib has always been the romantic, and max the realist. at that moment we know that max will be changed irrevocably. that ending took the wind out of me. that hurt, but it was thrilling too, made me excited for things to come.

‘love is like lightning.’ poor deib doesn’t know he has been struck by lightning, and is prone to the electricity of one. he doesn’t know it yet because of the gray sky gloom of his shattered heart.

the kiss is everything, it was shocking, kilig and all that, but in context of the story, it is more appealing more kilig to think of all the interactions that lead up to that accidental kiss, all the pent up tension in those interactions that is channeled into that meeting of lips. oh gosh! it just occurred to me, this kiss was predicated by such a verbose exchange just to prove a point, to win. it only took this kiss to shut both max and deib up. i would say there are no winners here. they are both losers to love. except. it’s still to early to call it, right?

in terms of the team up: implied as it is, this is what i mean when i say, i am unafraid for these two to go there, when necessary. there is such a safety i sense between donny and belle, in the way they care for each other. it’s beautiful.

to say that this show only promotes bullying to its young, impressionable target demographic, could not be more wrong. this show matters because it gives its characters (who are representative of today’s teen generation), complete arcs, and safe spaces for feelings no matter how ugly they are. it’s a show that allows teens to be teens, allows them to figure things out for themselves, a show that allows them to relate with one another, as they should. and the usual byproduct of emotional teens relating with one another is bullying. it’s not the best thing ever, but it is what it is. see, we can only pray and hope that the kids turn out to be good ones, but to expect kids to be perfect is out of the question. this is a work of fiction, of course there is a tinge of exaggeration. now, if you all are that bothered by the bullying, i hope there are adults watching with you. be kilig. have fun with the show, but always look deeper.

why do you think i needed three re-watches and few days for a post this long?

i am excited for the next episodes.

__

(if i think to add more, this will be edited).

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

you’re not taking language classes, you don’t have a native target language speaking best friend who also excels in explaining obscure grammar points, and you have zero idea where to begin without a textbook, so what do you do? the following tips are a hodgepodge of techniques i’ve used over my last five years of self-studying various languages...maybe they’ll be somewhat helpful for you as well!

The Beginning aka “Taking a Peek”

find exciting media: do you like to read? watch movies? listen to music? chances are that free ebooks in [X] language will give you the reading material you want [if your local library doesn’t], kanopy is a fantastic Netflix-like site that works with public libraries and universities to bring indie films [with captions] to you for free [and not just in the United States; New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Canada are some of the other countries supported], and Youtube has...nearly everything else. It’s the only place I can satisfy my need for japanese 80s pop...

pronunciation guides / syllabaries / alphabets: go ahead and hunt these down as well. the last thing you want to do [mainly non-Latin system languages here] is rely on romanization, especially non-standardized versions of what a word ‘might’ sound like. don’t do that yourself! take the time to learn the proper writing system. for pronunciation, find videos explaining the sounds as well. don’t rely only on transcriptions [unless they are in IPA, they could be inaccurate]. if you come across sounds that are unfamiliar, there are likely videos of comparisons from native speakers that will help you. obviously, there are exceptions, but as long as you do the best you can, that’s all you can ask.

start!: read that book, watch that horror film, and repeat that song 100 times. enjoy the content, and also start to pay attention to what is being said. are you noticing certain words being repeated over and over, and catching on to the pronunciation? have you looked up an interesting phrase in the dictionary? or maybe the chorus of that song is super catchy, and you want to take a look at the lyrics? do so! the more you engage with the material, the more you learn.

The Other Beginning aka “Should I Study Now?”

I ‘took a peek’ at Korean for two years before I thought of studying it ‘officially’. Same for Japanese. I’ve been peeking at French for four years [I think I forgot to take the next step!]. There’s no minimum or maximum in language learning. If you have a goal in mind, do what you need to!

grammar: full disclaimer here in that I love grammar, have loved grammar for the past five years, and I will always advocate for learning grammatical terms, and preparing yourself to actually study how things work in another language. language learning became a lot easier for me when I was able to compartmentalize a language into building blocks. there are so many resources that go into detail, but because they use terminology beyond many people’s school knowledge, they go untouched. it could definitely be worth it to spend time learning what an adjectival phrase, or conjunctivizer-something is [thanks Korean]. you don’t have to start out with an ‘Advanced X Language Grammar’ book, but there are websites that will explain enough that you aren’t wandering in the dark about the difference between des and du and de l’.

vocabulary: another disclaimer here, but I'm not the best with vocabulary. even in my spanish class, my professor commended my use of grammar, but asked whether or not I could switch my vocabulary up, and try something different. I think I’m more interested in how something is said, versus what is actually being said, and that’s a flaw I’m happy with, haha! I know most vocabulary because I would find myself missing a word, and search for it. At the very least, I use what I normally say in my native language, and find those words in other languages, and generally avoid massive vocabulary lists. Memrise and Anki are particularly good for plugging away at new words, and if anything, you can certainly start with the 625 most common words in a language, or 100 most common verbs, etc. Those lists work well for me.

The Middle of Forever

Use it, use it, use it. That’s my best advice [and what I tell my students every week]. Book studying will always pale in comparison to actually using the language, whether you are writing it or speaking it. But, what if you’re doing all of this alone?

Record yourself: My voice memos are still full of my ramblings in Spanish. Until I felt confident with my cadence and speed, I would listen to myself [gives me shivers still]. I don’t have too many people in my day to day life who speak the languages I study now, so talking to myself is most helpful. If you don’t want to record yourself, you can still speak, or think in your target language. I find myself narrating my actions, and sometimes my thoughts will switch over to a target language without me consciously doing so. Get used to existing in that language. Your mind will take over soon enough.

Write: I’ve always been an on and off journaling queen, but journaling in another language is an entirely different experience. I’ve always been dismayed to learn that I can’t really write much of anything, because my thoughts reach past my vocabulary. This exercise forces me to think IN the language I’m learning, and only speak about what I can conjure without using my native language. Sometimes, I do pick up a dictionary and search for words, because I know it’s something I should probably know, but other than that, thinking simply, and not pressuring myself, is the best way to go. There are apps like HiNative and Slowly that allow you to write with others and ask questions, and they can be really helpful. Joining a Discord to practice with like-minded learners was one of the best things I did for my studies last year.

Anything else?: Not really! Language learning seems much more magical from the outside than it really is. There aren’t any secret paths to building your self-discipline, and no potions for waking up fluent in your target language. It’s a lot of work. And, it’s only when you look back that you can actually see how far you have gone. You may not notice your progress every day, but when you re-watch that film after two months and pick up on familiar words, or read that book again and notice complex grammar, you can feel proud of yourself. Don’t give up because you can’t see anything yet; you can’t see the view from the bottom of the hill!

#pooh stuff#language learning#language tips#gloomstudy#heypat#saylorlook#rivkahlook#heydel#cyclicstudies#einstetic#vocative#lookasta#studyblr#langblr#lingblr#language studying#athenastudying#stxdii#boldlystudy#thekingsstudy#adelinestudiess#etudias#jyolook#problematicprocrastinator#stressfulsemantics#therobotstudies#lunalook

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEYOND LYRIC SHAME: BEN LERNER ON CLAUDIA RANKINE AND MAGGIE NELSON TWO FRESH INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROSE POEM

Language poetry—and to my mind the best Language poetry was written in prose—was a machine that ran on difficulty. Reading a prose poem deploying what Ron Silliman called “the new sentence” was intended to be an exercise in frustration: the reader attempts to combine the sentences—which are grammatical—into meaningful paragraphs. The sentences are vague enough (“Sentence structure is altered for torque, or increased polysemy/ambiguity”) that a logical relation between sentences will always almost seem possible. But the reader discovers as she goes that many successive sentences cannot be assimilated to a coherent paragraph, that paragraphs are organized arbitrarily (“quantitatively,” as opposed to around an idea), that no stable voice unifies the text, that her “will to integration”—her desire to produce higher orders of meaning that lead away from the words on the page into the realm of the signified (“a dematerializing motion”)—is repeatedly defeated.

The solicitation and then tactical frustration of the reader’s will to linguistic integration had an explicitly political object: it was advanced as a kind of deprogramming of bourgeois readerly assumptions. Such difficult prose would teach us that meaning is actively produced, never naturally given; that language is manipulable material, not a transparent window onto reality; that the “speaker” is a unifying fiction more than a stable subject; and so on. These deconstructive strategies were conceived not only as a critique of other writers—for example, lyric, “confessional” poets with their privileging of subjective experience and inwardness; mainstream novelists with their “optical realism”—but as an attack on existing social and political orders that depended upon the smooth functioning of dominant linguistic conventions.

Many of us learned something from the Language poets’ taking up of a constructivist vision of the self and its literature: their insistence on language as material, their combination of Russian formalism and various strains of French theory into a compelling reading of experimental modernism. (And many of us learned to appreciate certain texts associated with Language poetry in terms other than and often opposed to those provided by essays like Silliman’s “The New Sentence,” with its anti-expressive and anti-aesthetic bent). But who among us still believes, if any of us ever really did, that writing disjunctive prose poems counts as a legitimately subversive political practice?

Indeed, for many ambitious contemporary writers, disjunction has lost any obvious left political valence. Does the language of advertising and politicians, for instance, really depend on seamless integration? Transcripts of speeches by Bush or Palin or Trump would have been at home in In the American Tree. When aggressive ungrammaticality and non sequitur are fundamental to mainstream capitalist media (and to the rhetoric of an ascendant radical right), the new sentence appears more mimetic than defamiliarizing. In this context, “difficulty” as a valorized attribute of a textual strategy gives way to the difficulty of recovering the capacity for some mode of communication, of intersubjectivity, in light of the insistence of Language poets (and others) on the social constructedness of self and the irreducible conventional representation.

Language poetry’s notion of textual difficulty as a weapon in class warfare hasn’t aged well, but the force of its critique of what is typically referred to as “the lyric I” has endured in what Gillian White has recently called a diffuse and lingering “lyric shame”—a sense, now often uncritically assumed, that modes of writing and reading identified as lyric are embarrassingly egotistical and politically backward. White’s work seeks, among other things, to explore how “the ‘lyric’ tradition against which an avant-garde anti-lyricism has posited itself . . . never existed in the first place” and to reevaluate poems and poets often dismissed cursorily as instances of a bad lyric expressivity. She also seeks to refocus our attention on lyric as a reading practice, as a way of “projecting subjectivity onto poems,” emphasizing how debates about the status of lyric poetry are in fact organized around a “missing lyric object”: an ideal—that is, unreal—poem posited by the readerly assumptions of both defenders and detractors of lyric confessionalism.

“Who among us still believes, if any of us ever really did, that writing disjunctive prose poems counts as a legitimately subversive political practice?”

It’s against the backdrop that I’m describing that I read important early 21st-century works by poets such as Juliana Spahr (This Connection of Everyone with Lungs), Claudia Rankine (Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric and, very recently, Citizen: An American Lyric), and Maggie Nelson (Bluets). I mean that these very different writers have difficulty with the kind of difficulty celebrated by Language poets in particular and the historical avant-garde in general. Their books are purposefully accessible works that nevertheless seek to acknowledge the status of language as medium and the self as socially enmeshed. I read Rankine and Nelson’s works of prose poetry in particular as occupying the space where the no-longer-new sentence was; they are instances of a consciously post-avant-garde writing that refuses—without in any sense being simple—to advance formal difficulty as a mode of resistance, revolution, or pedagogy. I will also try to suggest how they operate knowingly within—but without succumbing to—a post–Language poetry environment of lyric shame or at the very least suspicion.

I call Rankine and Nelson’s books works of “prose poetry,” and they are certainly often taken up as such, but their generic status is by no means settled. Both writers—as with many Language poets—invite us to read prose as a form of poetry even as they trouble such distinctions. Rankine’s books are indexed as “Essay/Poetry” and Bluets is indexed as “Essay/Literature.” Bluets is published, however, by Wave Books, a publisher devoted entirely to poetry. Rankine’s two recent books are both subtitled “An American Lyric,” begging the question of how a generic marker traditionally understood as denoting short, musical, and expressive verse can be transposed into long, often tonally flat books written largely in prose. On an obvious but important level, I think the deployment of the sentence and paragraph under the sign of poetry, the book-length nature of the works in question, and the acknowledgment of the lyric as a problem (and central problematic) help situate these works in relation to the new sentence, even if that’s by no means the only way to read them.

Both Bluets and Don’t Let Me Be Lonely open with a mixture of detachment and emotional intensity that simultaneously evokes and complicates the status of the “lyric I.” In the first numbered paragraph of Bluets, quoted above, a language of impersonal philosophical skepticism—the “suppose,” the Tractatus-like numbering, the subjunctive—interacts with an emotional vocabulary and experiential detail. The italics also introduce the possibility of multiple voices, or at least two distinct temporalities of writing, undermining the assumption of univocality and spokenness conventionally associated with the lyric. “As though it were a confession”; “it became somehow personal”: two terms associated with lyric and its shame are both “spoken” and qualified at the outset of the book—a book that will go on to be powerfully confessional and personal indeed. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely opens with a related if distinct method of lyric evocation and complication, flatly describing what we might call the missing object of elegy:

There was a time I could say no one I knew well had died. This is not to suggest no one died. When I was eight my mother became pregnant. She went to the hospital to give birth and returned without the baby. Where’s the baby? We asked. Did she shrug? She was the kind of woman who liked to shrug; deep within her was an everlasting shrug. That didn’t seem like a death. The years went by and people only died on television—if they weren’t Black, they were wearing black or were terminally ill. Then I returned home from school one day and saw my father sitting on the steps of our home. He had a look that was unfamiliar; it was flooded, so leaking. I climbed the steps as far away from him as I could get. He was breaking or broken. Or, to be more precise, he looked to me like someone understanding his aloneness. Loneliness. His mother was dead. I’d never met her. It meant a trip back home for him. When he returned he spoke neither about the airplane nor the funeral.

Throughout Don’t Let Me Lonely the traditional lyric attributes of emotional immediacy and intensity are replaced with the problem of a kind of contemporary anesthesia—the repression of the reality of death, the leveling of tragedy into another kind of infotainment in a culture of spectacle, the mediation of experience by technologies ranging from television to pharmaceuticals. The problem of the deadening of feeling—the negative image of traditional lyric content—finds its formal correlative in a flat prose in which verse can appear only in citation or paratext, for example, quotations from Celan embedded in the prose, a Dickinson poem reproduced in the notes. Instead of imagining difficult prose as a technology for deconstructing the self, a highly linear and plainspoken account of the problem of the “I” is offered as Rankine attempts to work her way out of social despair: “If I am present in a subject position what responsibility do I have to the content, to the truth value, of the words themselves? Is ‘I’ even me or am ‘I’ a gear-shift to get from one sentence to the next? Should I say we? Is the voice not various if I take responsibility for it? What does my subject mean to me?”

Rankine forgoes difficulty as a strategy for disrupting subjectivity in order to acknowledge the difficulty of calibrating a responsible self socially. We could say that the anti-lyricism of Language poetry is gestured toward in the banishment of the traditional trappings of the lyric—verse itself, musicality, intense personal expression (what Rankine often confesses is a sense of inward emptiness)—but here these lyric strategies are less willfully rejected than made to feel unavailable. And the felt unavailability of the lyric is a result of Rankine’s explicit invitation to read her markedly nonlyric materials (essayistic and often flat prose) as lyric—to invite us to think of lyric as a reading practice as much as a writing practice in which the ostensibly “shameful” attributes of the mode (e.g., an egotistical, asocial inwardness) are replaced by a collaborative effort on the part of reader and writer to overcome “loneliness.”

Bluets explores many of these concerns with related if ultimately distinct means:

70. Am I trying, with these “propositions,” to build some kind of bower?—But surely this would be a mistake. For starters, words do not look like the things they designate (Maurice Merleau-Ponty).

71. I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do.

72. It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude. Loneliness is solitude with a problem. Can blue solve the problem, or can it at least keep me company within it?—No, not exactly. It cannot love me that way; it has no arms. But sometimes I do feel its presence to be a sort of wink—Here you are again, it says, and so am I.

Nelson’s “blue bower” evokes not only the actual bird, renowned for how the males construct and decorate “bowers” to attract mates, but also the traditional association of lyric with a metaphorics of birds and birdsong. It further evokes the Dante Gabriel Rossetti (a shamelessly lyric poet if there ever was one) painting of that name, as well as his poem with the received title “The Song of the Bower.” To build a “blue bower” out of “propositions” is to cross a lyric and anti-lyric project in the space of prose, implicating and complicating both. It is hard to find dignity in the privacy of the aestheticized bower—indeed, one might be ashamed of such inwardness—and one of the goals of Bluets will be to test what part of experience is sharable as a way out of isolation and despair.

The color blue functions as the organizing metaphor for both the possibility of intersubjectivity (“15. I think of these people as my blue correspondents, whose job it is to send me blue reports from the field.”) and its limits (“105. There are no instruments for measuring color; there are no ‘color thermometers.’ How could there be, as ‘color knowledge’ always remains contingent upon an individual perceiver.”). Nelson’s accumulating “propositions” do not integrate into a “bower,” but the relation between sentences and sections has little in common with new-sentence disjunction. As in Rankine’s prose poetry, difficulty here is not deployed as a political/poetical tactic irrupting within the norms of prose; instead, the difficulty of finding a defensible, dignified ground for intersubjectivity is narrated explicitly.

“One of the goals of Bluets will be to test what part of experience is sharable as a way out of isolation and despair.”

The shift from the tactical deconstruction of ostensibly natural narrative or lyric unities to the effort to reconstruct them with a difference is legible in part because Bluets foregrounds its relation to avant-garde prose poetry. Nelson’s use of Wittgenstein as muse and model, for instance, invites us to position her work relative to new sentence experiments. Silliman not only cited the Philosophical Investigations in “The New Sentence” as an important precedent, but Silliman’s own The Chinese Notebook models the tone and structure of Wittgenstein’s philosophical writing. More generally, the work of Marjorie Perloff (Wittgenstein’s Ladder) and others has made clear how the philosopher’s inquiries into language as a form of social practice—and his own peculiar linguistic operations—have been central to scores of experimental (“difficult”) writers. If Nelson weren’t also the author of volumes of verse, and if Wave weren’t the publisher of Bluets, my experience of context and thus text would be different: those facts function as a quieter version of Rankine’s subtitle, inviting—or at the very least enabling—us to think of poetry as a reading practice as much as a writing practice, and to experience verse techniques as withheld or unavailable in Bluets instead of as merely forgone or forsworn.

As in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, in Bluets, actual verse is exiled to the space of citation: William Carlos Williams, Lorine Neideker, and Lord Byron, among many others, are quoted; line breaks are replaced with slashes. Indeed, Nelson doesn’t have much faith in the effects of actual poems: “12. And please don’t talk to me about ‘things as they are’ being changed upon any ‘blue guitar.’ What can be changed upon a blue guitar is not of interest here.” Or: “For better or worse, I do not think that writing changes things very much, if at all” (proposition 183). And yet, the relegation of verse to the virtual space of citation lends it a certain power, displaying it while also insisting that it’s nearly out of reach. This allows Nelson’s prose to be haunted by the abstract possibility of a poetry it can’t actualize, somewhat like the Mallarméan fantasy she at one point describes: “For Mallarmé, the perfect book was one whose pages have never been cut, their mystery forever preserved, like a bird’s folded wing, or a fan never opened.” Moreover, Bluets—taking its cue (and lifting many of its locutions) from Wittgenstein’s attacks on Goethe’s Theory of Colors—often refers to outmoded regimes of knowledge or technologies (e.g., the 18th-century “cyanometer,” which sought to measure the blue of the sky). One begins to wonder if verse—lyric poetry in particular—is another set of defunct measures, outmoded conventions for communicating experience.

Perhaps there is a sense for Nelson (and Rankine) in which poetry isn’t difficult—it’s impossible. There is faith neither in poetry’s power of imaginative redescription (the blue guitar) nor in its practical effects as a technology of intervening in history (“I do not think that writing changes very much”). The subject isn’t a dominant bourgeois fiction of inwardness and univocality in need of deconstruction via new sentence difficulty but an avowedly social and linguistic entity deployed over time in the space of writing; expression itself must be constructed, and that process is narrated clearly in a prose that, when read as poetry, makes actual verse present as a loss. Although I believe these authors use the prose poem and the felt absence of verse in fresh and specific ways, I am not suggesting that the logic I’m describing is exactly new. Stephen Fredman and others have suggested that the prose poem arises as a form during periods in which there is a crisis of confidence in verse strategies, and the notion of the lyric being felt as a loss as it becomes prose is at least as old as Walter Benjamin. Here my limited goal is to indicate a few specific ways the new sentence valorization of difficulty can become a frame for a specific kind of accessibility for two important contemporary poets who write primarily in prose.

One can’t pretend to contextualize these books without stating explicitly that part of the contemporary dissatisfaction with attacks on narrative and voice as political strategies is that they can serve to mask what is essentially a white male universalism. The rejection of linguistic integration and anti-expressionist attacks on the lyric subject have recently been described by Cathy Park Hong as a symptom of the avant-garde’s “delusion of whiteness,”

its specious belief that renouncing subject and voice is anti-authoritarian, when in fact such wholesale pronouncements are clueless that the disenfranchised need such bourgeois niceties like voice to alter conditions forged in history. The avant-garde’s “delusion of whiteness” is the luxurious opinion that anyone can be “post-identity” and can casually slip in and out of identities like a video game avatar, when there are those who are consistently harassed, surveilled, profiled, or deported for whom they are.

In a related vein, Nelson’s own work as a critic has been attuned to how “the male Language writers’ occasionally monomaniacal focus on warring economic systems” was both challenged and expanded by women writers inside and outside of the Language movement itself. In ways I haven’t had the space to explore here, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and Bluets are engaged with demonstrating how the uncritical acceptance of voice and narrative conventions as well as their “wholesale” disavowal by certain avant-garde writers can preserve racist and sexist ideologies. This is by now an old difficulty, echoing the even older modernism/realism debate—how the emancipatory potential of poststructuralist strategies quickly cools into a conservatism (or worse) like the one Cathy Park Hong describes. Out of this abiding difficulty more complex, accessible prose poetry is likely to arise. How might verse return? And when and why?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Birth of Japan Game: Episode 2: The Backstory

The Birth of Japan Game is a chronicle in ten parts, recounting the early years of Dorian Gray’s journey along the path. The narrative begins some time in 2006 and concludes in early 2012. Names have been changed to protect the guilty and innocent alike. Previous episode here.

Let’s flash back to two years before I met Momoka, when I was a tall, lanky eighteen year old with a forgettable face and dreamy disposition. When I wasn’t working deadening rock bottom jobs such as cleaning hotel rooms, I had my head buried in a book. I’d had girlfriends before and the occasional one night stand – okay, “drunken hook-up” is more accurate; I don’t believe teenagers can actually have a “one night stand,” which sounds like something a heavily sweating, hard-driven lawyer might do with an aging beautician after meeting in a hotel bar – but I was prone to depression and easily became discouraged; my identity did not allow for the active, much less aggressive, pursuit of women.

I first encountered Japanese people while wandering the campus of my university in Australia as a first year student. I’d moved to the city from a small town and had few friends, so instead of sitting in my room all day I decided to walk about and see if anything interesting was happening. I was awkward and naive but desperate to live; my high school years had been burdened by my failure to connect with the right crowd and the girls I wanted most. Now it was time for a new beginning. I’d even started visiting bars and clubs in the city, though I was usually too nervous to do much but stand around like a spectator.

It was the start of the first semester. The weather was sunny and clear, and students filled every corner of the campus’s open lawn. There were food stalls from other countries – Singapore, Malaysia, India – and hundreds of girls, both domestic and foreign: bronzed Australians in mini shorts, tall African goddesses, severe-looking European blondes with high cheek bones, and all manner of Asians. While walking across the grass I noticed a small group of the latter sitting in a circle and enjoying chicken kebabs from one of the stalls. On impulse I sat down and introduced myself to a young man with a mop of shiny black hair. His English was halting at first, but he seemed eager to talk and introduced himself as Hayato, an exchange student from Kyoto. He’d arrived in Australia two months earlier. Soon we were deep in conversation, drawing amused stares from the other Japanese students. I confessed to an almost total ignorance of his culture, and he promised to explain it to me if I’d help him with his English.

The part about my ignorance wasn’t strictly true. Like many my age, I’d grown up on Nintendo, and I enjoyed the occasional anime or Japanese film – the works of Takashi Miike and Takeshi Kitano being particular favorites. But my image of Japan had been formed entirely by the motley assortment of cultural products that had made it through to the West; I saw it as a land of flashing lights and flying ninjas, a garish mixture of the rigidly traditional and surreally post-modern. It was a land of raw fish and flashing arcades, unreadable glyphs and gleaming perversions. I hadn’t given any thought to the everyday lives of the Japanese; hadn’t, in fact, seen them as people at all. There had been no Japanese or other Asians in my small hometown, so I’d never had to test my preconceptions against reality. On a whim I’d joined the campus Anime Club, but had found it full of social misfits with doubtful hygiene – not the best place to make friends. Most of the members were bitter cosplaying lesbians and obese shut-ins unable to make eye contact. I stopped going after the second meeting.

Later in the week Hayato invited me to a party at his flat with the other exchange students, and our friendship developed quickly. I helped him with his English, often completing entire assignments for him, while he introduced me to his culture – and more importantly, his psychology. Hayato (who is now the editor of a major Japanese newspaper) was a clever and sometimes cruel young man who enjoyed amusing himself with his wide-eyed Australian friend. He taught me all kinds of obscenities which he claimed were common greetings, and I dutifully repeated them to the female exchange students, earning some truly shocked and withering looks. But he was right about Japanese food, which I quickly came to love: the subtle flavors and tart simplicity, how I could eat as much as I wanted without feeling full. I learned the names of all different kinds of sushi – toro, maguro, ikura, uni, buri, engawa – fish whose names I barely knew in English.

But Hayato’s greatest gift, and one of the most decisive influences on my life, was his encouragement to learn Japanese. The first time he brought it up I smiled and nodded but dismissed him immediately: how could anyone really memorize thousands of kanji characters and the fiendish intricacies of that alien, arcane grammar? I’d picked up remedial French and Spanish in high school, but at least those used the Roman alphabet. Japanese was uncharted territory, and nothing I knew would be of any use.

“You’ll pick it up quickly,” Hayato assured me. “Don’t worry – we’ll all help you. Once you get a Japanese girlfriend it’ll be easy!”

I was just naive enough to believe him, and the next semester I enrolled in an introductory language class. My motivation was as much practical as idealistic; my Media Studies degree was looking increasingly useless, and I wanted a certifiable skill I could write on my resume. The prospect of a future translation job seemed incentive enough to continue. Speaking a bit of French and Spanish seemed trivial in comparison with reading a Japanese newspaper or watching a Kurosawa film without subtitles, and the fluent Australian students in the classes above me struck me as incredibly worldly and sophisticated. Many of them showed me pictures of their Japanese girlfriends, some of whom showed up to meet them after class. I was certain that at last I was on the right path.

Learning Japanese proved to be an adventure beyond the scope of this book – those interested are advised to consult the numerous websites on the theme. The language was demanding but curiously logical – more so, in fact, than English, with its numerous irregular verbs and irrational spellings. As expected, the kanji writing system was the biggest challenge, but even it yielded unexpected felicities. Once I cleared the initial hurdles, I discovered that a pictorial rather than phonetic writing system made sense in ways I hadn’t imagined. I gained a feel for the character combinations and learned to figure out the readings of unfamiliar words. The language, which had once been forbidding and inaccessible, became practical, even poetic.

More importantly, learning Japanese was my key to understanding Japanese culture. I was suddenly introduced to an unsuspected world of music and film, art and fashion. Why had I never heard of Ayumi Hamasaki and Shiina Ringo? Or read FRUiTS magazine, with its cavalcade of front-line Harajuku fashions? What about the Shibuya-kei music scene of the 1990s with its links to French pop and American indie? Japan was no longer a cliched planet of craziness, it was an entire world with its own codes and jokes, clothes and trends and thousands of years of history. I took another language class, and another, and then ones on culture and economics. Before I knew it I’d taken on a whole new major: Japanese Studies.

While all this was happening, I maintained my close association with Hayato and the other exchange students. Most of them were a few years older than me, and looking back I can see that they thought of me as a little brother, pardoning whatever ridiculous cultural faux pas I made and indulging my fumbling attempts at speaking their language. All of us lived in the university’s student housing, so it was always easy to meet up for drinks and study sessions. Sometimes they invited me over for massive fry-ups of Japanese dishes I’d never heard of, like okonomiyaki and takoyaki – or in other words, savory cabbage pancakes and deep-fried chunks of battered octopus. They’re both much better than they sound.

The student housing was filled with young people from countless different countries, and in addition to my Japanese friends, I picked up all kinds of knowledge from Ethiopians, Mongolians, Indians, Malaysians, and a variety of Europeans. And of course, there were other Australians. One of them, Daryl, was a slick character with a salesman’s smile and natural Aussie charm. He had no interest in Japanese language or culture but still hung around the exchange students, often showing up at parties and dinners. I was a bit suspicious of him at first, but he seemed harmless enough.

Before long my thoughts returned to what Hayato had said about getting a Japanese girlfriend. Obviously a personal language partner would be helpful, but I already had several competent teachers, and now I wanted a cool girl I could connect with. And so I considered the female exchange students. One of them, Tomomi, was more attractive than the rest. The others were short, squat and a bit chubby, and they didn’t seem to bother with makeup or suggestive clothing. Only Tomomi commanded attention. She was tall, with a curvy figure and a mischievous face that suggested a preference for partying rather than studying in her room. I decided that I had to make her mine, even though I had no idea how. She was in my social circle, if that term could be applied to the loose crowd cohering around the student flats, but it never occurred to me that I could simply knock on her door and invite her to dinner. My earlier overtures to girls had been either laughably grandiose – I once sent a girl an enormous, needlessly expensive bouquet of flowers, and wrote poems to others – or so subtle that they never registered at all. I was about as far from a natural as anyone could be. Still, I felt certain that if I remained in Tomomi’s orbit, the right chance would come for us to connect.

So I was taken aback, as you might imagine, when Daryl started fucking her.

His tactic had been everything mine wasn’t: casual but fearlessly direct. He’d gone around to her apartment with some drinks, and before long they’d started making out. Within a few days they were inseparable.

I’d been beaten to the punch, and I wasn’t happy. Predictably, I became depressed and moped around for days.

“Don’t feel so bad,” Hayato reassured me. “There are lots more like her.”

He wasn’t wrong, and the next year, when he returned to Japan, Hayato made good on his word. A new exchange student would be arriving from his university, he told me, and he wanted me to show her around campus and help her settle in. His meaning was clear: this girl was for me. Her name was Maya.

If the implication that Hayato could simply give her to me like a gift seems demeaning, it’s important to remember that these kinds of introductions are common in Japan, where women often meet their boyfriends through a mutual acquaintance. The hierarchical system of sempai (senior) and kouhai (junior) means that these acquaintances are usually older students at their high school or university, or a boss or manager at their company. The culture is gradually changing, but it’s still common and considered normal. Looked at this way, Maya and I were both Hayato’s kouhai, and as such it was natural that he should introduce us. Maya later told me that he had written her a long email praising my character and encouraging her to go on a date with me if she were so inclined. In other words, I was a gift for her as much as she was for me.

(Daryl, incidentally, tired of Tomomi within two months and moved on to seducing other foreign students. Even to this day I can’t think of him without feeling a twinge of jealousy, but now it’s leavened with amusement).

When I heard that Maya had arrived, I went around to her flat and left a message for her. We met up the next day in the university cafeteria. She was a tall girl, very thin, with an angular body, elfin features and slightly crooked teeth that actually enhanced her smile. Talking to her, I saw that she was a genuinely good-natured person without a trace of negativity. I showed her around campus and later took her around the city, all the while planning how to make my move. I eventually decided to invite her to Zero Hour, a bar on campus. It had a balcony and lots of dark recesses for private conversations, and the music, though loud, usually wasn’t deafening.

Maya accepted the invitation, and we met in front of the bar on the night I’d specified. Soon we were inside and sharing a pitcher of beer. True to my calculating nature, I’d gotten some Australian friends to “accidentally” wander by and talk me up, which they dutifully did. I’m sure a more cynical girl would have been suspicious, but Maya didn’t seem to suspect anything and acted duly impressed. An hour or two passed, the bar filled up and the music got louder. Both of us relaxed and moved onto the dance floor. I reached over and took her hand as Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People” came on over the speakers. The ridiculous camp atmosphere perfectly matched my overblown emotions. With no destination in mind, I led Maya off the dance floor and out of the bar. It was a warm night and the stars were out; a crowd of students milled around the entrance. My heart was racing as I led her along the path leading back to the student flats. We eventually stopped in an out-of-the-way area between buildings, where we sat on a disused office table that was waiting to be placed in storage. We were both drunk enough that our trivial conversation seemed momentous, and before long we were making out. Then I pulled a kokuhaku, or confession, formally asking her to be my girlfriend. She accepted, and more kissing ensued. Not long after, a random drunk Australian wandered by on his way home.

“You guys are a good couple,” he said.

I could have led Maya back to my room right then – our flats were not far from each other’s, and she was clearly willing. In fact, she later asked me why I hadn’t immediately taken her back to my place. I honestly didn’t know. Perhaps I still had some nonsense idea of how a gentleman was supposed to behave or, more likely, I simply hadn’t thought of it.

The next day I went to her flat and an all-day sex session commenced. She was as eager as I was, and seemed surprised that I was interested in her.

“I wasn’t sure last night really happened,” she said. “I thought you’d wake up today and not want to see me again.”

I reassured her that she was all I wanted. Soon we were a serious couple, sleeping over at each other’s flats most nights and travelling around Australia together during our vacation time. Our groups of friends merged and I ended up staying with her for nearly two years, even after she returned to Japan, as I continued my education in her language and culture. I was hopeless at first, and we almost always spoke in English, with her encouraging my fledgling attempts at coherent Japanese sentences.

This was one of the happiest periods of my life, and for a while it seemed that all my dreams had come true. Maya had a sunny disposition and no sexual hang ups; in fact she was open to experimenting with costumes, role playing and other things which I’d been too shy to suggest to my previous girlfriends. I confessed all kinds of fantasies, and she embraced every one of them with naive enthusiasm. Our mutual foreignness made us bold with each other, and our erotic life quickly became colorful.

The year passed quickly in relative bliss. By now I’d set my sights on studying in Japan and perhaps even living there for good. At the time I imagined this as the next step in my relationship with Maya – or at least that’s what I told myself, and looking back, I think I believed it. But I was gradually changing, becoming more confident, looking ahead to new experiences. And somewhere in the back of my mind, the hunger for more girls was already growing.

The post The Birth of Japan Game: Episode 2: The Backstory appeared first on Attraction Japan.

from Attraction Japan http://attractionjapan.com/birth-japan-game-episode-2-backstory/

0 notes

Note

So how is Spy a special case?

*is excited*

(for context, in a previous post, i added the tags " i could write an entire book on how unfamiliar french people in medias seem to actual french people, spy is an odd case; ask me about him")

aiight, you know what you signed up for, get ready for one hell of a presentation, ft terminal verbosis frenchosis ! this will be in three parts, of course, because three is a good number and the mere concept of having 3 parts should give you all a headache (look ray i didnt add a n this time)

wait shit im not even sure mistral is a spy, hold on,

aw fck thats for real ones

anyways femme fatale trope, next question

HA gotcha, you didnt think id let yall go with just one sentence huh ? so. our fella is french. our fella is a spy. our fella is a huge piece of shit. extremely common, alright ? outright overused archetype. eeeexcept that the combo's execution here REALLY stands out. how so ?

well, let me ask you a quick question. do you think the fact that he is french, and the fact that he is an evil bastard, and the fact that he is a spy are linked ?

well ill answer that for you. nope. valve treated these three traits remarkably separately. the way he speaks french in game is relatively polite, and the insults he throws around are, i checked, exclusively in english. he is surprisingly free of the usual way medias make "being evil" and "being french" be a hand in hand thing, and similarly free of the one that seems to indicate that Because you are french Of Course you are a spy. in other words, rather than being a walking glamour stereotype of sorts or an obnoxious asshole the likes of which we have seen hundreds of, this is a godawful guy that also happens to be a french snob, and that also happens to be a spy.

compare with, say, our lady mistral above who has a shitton of taunts in french, who embraces that whole sexy lady deal, deliberately plays on it and so on. difference is miles.

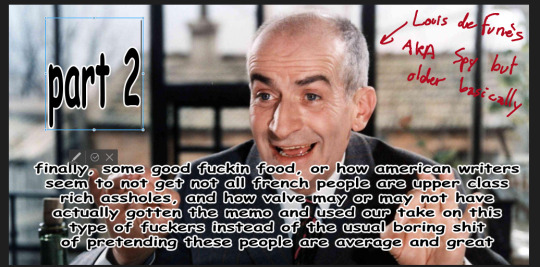

and now if you followed you did catch i said french snob rather than just french, there is a reason behind this, so allow me to get on part 2, which i promise will be WAY more verbose-

so

im not sure why but american medias love to have peppy rich french fashionistas in their shit. theyre cute, hyper, sheltered as fuck, and the entire deal is weird bc these people seem like aliens to actual french people who tend to care about fashion in pretty normal amounts and definitely do not have that many grands to bust into it. *yes* we pride ourselves in having a pretty neat fashion industry, but in a similar way as the american and the german boast about their cars. we are NOT obsessed with it okay. anyways, sometimes writers have the decency of making these characters cunts, but not always. but what doesnt vary is the trope seems to play out like ah yes, your average french- which is fucking baffling. and is the part taking us aback.

see, we HAVE the evil breed of those characters too in our shit. comedic shit, to be precise. a rundown of our humor is it often is situational humor - stupid outlandish situations with equally stupid archetypal characters, their personality equally pushed into the absurd, all of that more often than not thinly veiling some pretty heavy social commentary. in other words, you often laugh at the evil cop/rich factory/big restaurant owner/politician/etc getting karma'd in mind boggingly bizzare and hilarious ways, while clearly showing them as evil for mistreating subordinates (and often getting shit for it sooner or later) and as simpering cowards towards literally anyone who has any kind of superior position to them whatsoever.

in other words, context matters. where in american shit they are often allies or friends or comedic relief of sorts through being french/annoying or just villains, in french shit they more often than not are *targets* of some kind of events and shown to be ridiculous through other means than their obsession for fashion or whatever.

am i saying that valve did this ?

...yeah. thats a very bold statement, but yes. i mean, cmon,

see, i am overall basing this on the fact that ingame spy is so fucking similar to many, many, many of Louis de Funès' roles, and even his face, it outright had me searching around the wiki for some kind, any kind of claim of inspiration from valve-

he reads exactly as one of them ! rich cunt obsessed with money, constantly mocking people, constantly complaining about everything ever, fakely polite, not opposed to doing vile acts to have his way, extremely menacing face, *the same fucking laugh*, and the fact that characters played by this guy have remarkably often have what we call a couillon de fils, a dumbfuck of a loser ass son, if you will.

the only differences really are from comic spy, who reads far less like this. he's still well executed mind you, but he (especially @miss pauling) reads as far kinder than this dude's characters usually are, and he is a bit more... stretched, both physically and in behaviour, than the actor's goblin build and attitude, as game spy seems to be unable to stand straight whereas the comic one seems to have no difficulty with this, and the similar range of expressiveness that also ports 1:1 is game exclusive as well. and finally, comic spy also was not given the occasion to cuss people out, so.

anyways my point mostly amounts to, if you manage to make french people think of an emblematic actor beloved by many, rather than just make us go through the usual whiplash of "how is that a normal french person to american people ???", you are probably doing something right.

youtube

in addition to this wall of text, i am begging you all to watch this, it should help understand what i meant by our breed of humor, and what i mean by "spy could have been played by this dude no problem"

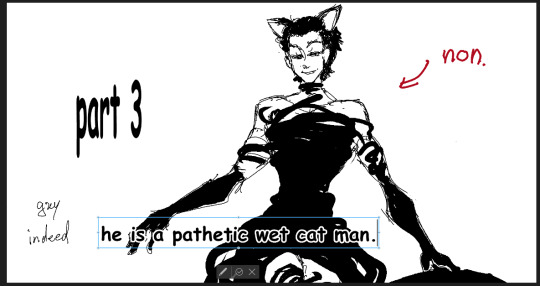

now, onto part 3,

well once you said he is a pathetic wet cat man you summed it up really.

for all the class he has, for all the money he has, for all the. everything ? he still is pathetic. he still is simply seen as a mean as fuck loser either trying to drown his failures as a father with expensive tastes, or simply amoral and unsympathetic because of his concerns being about money rather than about humans. he still is headcanoned as stinking by most of the fandom. nobody respects the fucken spy. he comes across as haughty and it only makes people want to shit on him some more.

really, it is pretty much everything I explained in the two points above. the patheticness helps with making it so he is not a stereotype, and it helps making it clear he is supposed to be representative of rich pretentious cunts rather than of french people.

so, he is a huge bitch, and ironically, this makes him a blorbo to us, bc who doesnt love a good ole flawed character ?

his whole french deal is not shown as eccentric or what makes him a loser but just a coincidence, in a sense. and you'd be surprised by how much of a breath of fresh air this is to french people. shitty in a realistic way rather than a made up clown, and in a way we can recognize in our own medias. it also is neat from the, err, fandom pov ? because you get to develop his frenchness and assholeness and spyness separately, since they are elements implemented for the sake of themselves rather than as a stereotypical whole. you get to have *fun* with him.

SO i think i ran out of things to blabber about. hope it makes sense tho. but i guess it really is about. not *quite* representation because we do not see ourselves in spy, of course, but way more about our culture not being bastardized and being turned into a joke about eccentrics at best, or hatred about seductive women and effeminate/homosexual men at worst, + having a fresh execution on tropes that else usually would get our eyes rolling.

alpha, over and out

#tf2 spy#langage language#tf2#The Council has spoken#god my tags are a mess#hope yall can bear with how im basically the messiest member of the council#comes with being the frenchman i suppose

39 notes

·

View notes