#historia brittonum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

so i've been reading (that's new) about origin myths of the british isles (because i can) and i have had a revelation

HEAR ME OUT

so

a sequel to the Paris musical from 1990

but about Brutus of Troy

aka Medieval Britain's OC do not steal

ITS GENIUS I PROMISE

ASK ME ABOUT BRUTUS, I WILL HAPPILY YAP

#brutus of troy#imagine virgil's aeneid but take it to the next level#GIANTS#it has GIANTS#tagamemnon#kind of#trojan war#jon english#paris the musical#mythology stuff#albion#corineus#aeneas#historia brittonum#historia regum britanniae#geoffrey of monmouth#mop#the history of the kings of britain

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix A in Faletra's translation of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain

I wanted to cover these too, but they're mostly excerpts so I don't want to cover them individually.

Part of the reason I got Michael Faletra's translation of the History of the Kings of Britain was its appendices. (I believe it's also one of the more recent translations, from 2008, and that was the othe reason.)

I already posted about Vita Merlini, because that's included in its entirety. Everything else is excerpts. Appendix A is focused on historical sources that Geoffrey of Monmouth drew on for his History.

Gildas, the Ruin of Britain (De Exicidio Britanniae)

The intro description of the Isle of Britain, which Faletra included it to illustrate how Geoffrey pulled almost verbatim from Gildas for parts of the History. The excerpt continues on with a lot of deriding Britain (and I believe this is mostly Breton specifically, aka Wales and southern England, but I'm not sure): "Since the days of its earliest settlement, Britain has been over-proud in mind and spirit, rebellious against God, against its own citizens, and even occasionally against kings and peoples from across the sea." Gildas focuses on the history of Britain from the days of the Roman emperors, "describing the evils that Britain has infliced upon others."

He writes from a very Christian perspective, and mostly focuses on Christian martyrs and various saints. This is one of the more lengthier excerpts that Faletra includes in the appendices,covering a significant chunk of time that Geoffrey also covers and pulled from Gildas very directly, minus most of the moralizing. (Weirdly. You'd think Geoffrey would do more moralizing, but I suppose he was only kind of a priest, having been given a bishop position eight days after a quick ordination as a priest, probably as a reward because the Normans liked his History.)

Pseudo-Nennius, The History of the Britons (Historia Brittonum)

Faletra writes that pseudo-Nennius "seems to have been doing recovery work, wanting to get the facts and stories that he knew on the historical record before his source materials, whether oral or written, were lost forever." It has less rhetorical polish and often offers multiple accounts or versions of an event, and pseudo-Nennius tries to organize the disparate sources. Geoffrey pulls heavily from the History of the Britons for his own Historia, namely for the founding of Britain and the stories of Merlin/Ambrosius and Vortigern, and then expands upon it.

This one is clunkier to read, and more dry. It's a lot of very quick summaries, no poetic turns of phrase. Like Gildas, pseudo-Nennius also desn't seem to have a very high opinion of the Bretons and talks a lot about them being sinful.

I'll cover Appendix B (focused on Merlin) in a separate post.

#michael faletra#geoffrey of monmouth#pseudo-nennius#nennius#merlin#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian newbie#gildas#historia brittonum#de excidio britanniae

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

merlin Ambrose getting kidnapped during a backyard basketball tournament and getting promoted into a powerful mayor then to Prime Minister is so funny to me

#arthuriana#historia brittonum#heli blobbing#dont let your dreams stay as dreams#sometimes you are just the son of the roman consul

1 note

·

View note

Text

Historia Brittonum

A period film ostensibly about a Welsh monk named Nennius writing the history of the Britons, but much of it is about the scholarship of medieval monks attempting to record mostly oral records of a history which was rarely if ever recorded, and whether or not to include certain people, acts, or battles, largely centering around one King Arthur.

#bad idea#movie pitch#pitch and moan#king arthur#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthur pendragon#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#welsh#wales#england#britain#english history#british history#historia brittonum#nennius#welsh monk#history#mythology#period film

0 notes

Text

🧐

2024 - 1454 = 571 570 (excuse my previous math, however 571 is 2024 - 1453 so my point still stands, merlin stans don’t get math degrees)

according to wikipedia the historia brittonum is dated to like 828, 300 years before that puts you in the 500s, 571 could be the canon date everything takes place in, ignoring all anachronisms (lol there’s a word i’d never thought i’d use outside of english class)

you know, if i really was a clotpole i’d even say you’re onto something.

Guys. Guys.

Something happened. Something that I'm sure they thought no one would notice, but they don't know they have someone who stalks their page.

They deleted a post. They had 1454 posts yesterday.

At first I was CONVINCED they deleted yesterday's clip because of all the people commenting on the homoerotic undertones... BUT NO. It's still up. So I'll investigate and let you know which one it is.

Either a post or an answer... I have everything documented and cataloged. They can't escape me

#my only source is wikipedia#i sound insane don't i#bbc merlin#merlin#bbc merthur#merlin twitter#camelotgate#merthur#other#merlin bbc#arthur pendragon#look up the annales cambriae and the historia brittonum#we know geoffrey of monmouth liked to play around with his history#so why not his dates#571 or 573 who really knows when arthur lived#arent we all just clowns#in the end

145 notes

·

View notes

Note

PLEASE TELL US ABOUT Y DDRAIG TRAWS!

Certainly! I'm more than happy to oblige.

First though I'm gonna need to tldr: the history of Y Ddraig Goch before we get onto the (accidentally) canonically trans part.

A brief history of Y Ddraig Goch:

(The modern Welsh flag)

Y Ddraig Goch first appears in the tales of the Mabinogi (Charlotte Guest version) in the tale of Lludd and Llefelys where it is fighting a white dragon. The fight is also described/expanded upon in the c. 829 AD text Historia Brittonum (attributed to Nennius) - where the red dragon represents Wales and the white dragon represents the Anglo-Saxons. In the story the red dragon triumphs over the white. Of course, Geoffrey of Monmouth also covers the story c. 1136 in Historia Regnum Brittaniae in which he introduces the concept of the red dragon heralding the arrival of King Arthur.

Geoffrey of Monmouth claims Arthur used a banner featuring a golden dragon. But we also know the accuracy of Monmouth can be questionable at times. Owain Glyndŵr did use a banner with a golden dragon called Y Ddraig Aur - raised in 1401 at Caernarfon - Glyndŵr chose this banner as a nod to the supposed banner of Arthur and his father.

Later on the Tudor monarchs (being a Welsh family) adopted a red dragon on a white and green background in their heraldry. Eventually Y Ddraig Goch on a white and green background became the official badge of Wales in 1800. The design became the official flag of Wales in 1959.

Y Ddraig Traws:

Now for the thing you're all here for -

So, as outlined, the history of the dragon as a national symbol of Wales goes back a long way. If we're just talking post-1959, there's some interesting implications for Y Ddraig Goch's depiction.

This is what the Welsh flag (and Y Ddraig Goch) looked like in 1959 when it was officially adopted as the flag of Wales. It looks broadly the same as the first flag and has some common features - such as not having a penis (or, as in the correct heraldic terminology - a pizzle). Meanwhile, in the arms of the Tudors (specifically Henry VII)

(Tudor dragon with pizzle) vs (dragon on the flag of Cardiff - pizzleless)

the penis is almost always included. So much to the point that the present royal family still includes the penis. While pretty much 0 depictions of the dragon in Wales include a penis. So you could interpret this as the dragon is seen as male only by the British royal family and as female everywhere else (which kinda implies that at some point the Tudor dragon had an mtf transition in Wales and she keeps getting misgendered by the royal family every time she is depicted in (mostly) England).

So much to the point that in 1995 this pound coin was made by the Royal Mint featuring the pizzle on the dragon with all four feet touching the ground as opposed to standing up (passant rather than rampant).

But in Wales you'd be hard pressed to see a pizzled dragon anywhere. Ergo, we can only conclude Y Ddraig Goch is trans and she transitioned in Wales and keeps getting misgendered in England.

[note: This is mostly tongue in cheek - but I do think it's fun to extrapolate that the Welsh dragon is trans because of the differences in depiction between Wales and England. Like many things Welsh, it is misrepresented by England and the idea of the Welsh dragon being misgendered only in England is, I think, a good metaphor for a whole lot of English treatment of Wales.]

Unrelatedly, there is a gay Welsh flag held at the National Museum of Wales which has a very wonky dragon which I find very endearing.

(cleaned up version I made)

So much so I made it an emoji in my Welsh bilingual LGBTQIA+ Discord (requirements for joining are - be 16+, either speak or are learning Welsh and identify as LGBTQIA+ in some way. Dm for link!).

(triaist ti 'you tried' emoji)

~ Completely unrelatedly ~ never forget the time someone was trying to homophobic to me by suggesting that I was disrespecting all the soldiers who died 'for the Welsh flag' by making it rainbow colours and not red - arguing that any change of colour of the dragon was disrespectful. Reader, my bus pass at the time for Mid Wales Travel had a purple dragon on it.

#cymraeg#welsh#cymblr#cwiar#trawsryweddol#traws#trans#trans dragon#y ddraig goch#welsh dragon#welsh history#dragons#wyverns#last tag because technically Owain's golden dragon is technically a wyvern

708 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Superhuman Feats of the Knights of the Round Table (And it's not even all of their feats!)

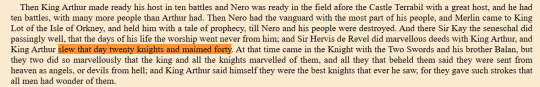

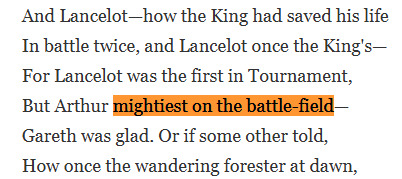

Arthur: (The Overall Strongest)

Historia Brittonum

Culwch and Olwen

Historia Regum Britannia (Geoffrey nerfs Arthur)

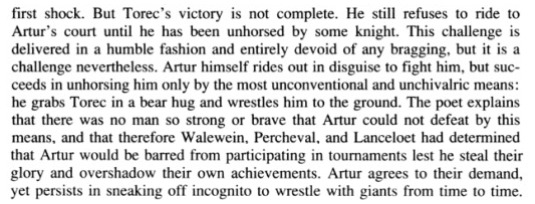

Torec (From King Arthur in the Medieval Low Countries)

Le Morte D'Arthur (Arthur nerfed again)

Idylls of the King

Kay and Bedivere (Both from Pa Gur)

[...[

[...]

Kay (Note: this doesn't take into account his superpowers)

[...]

Bedivere

Lancelot (focusing mostly on Vulgate, as Lance has a TON of feats everywhere that it would take an entire post)

Vulgate Cycle - Lancelot in Val Sans Retour, killing Morgan's Dragons

Vulgate Cycle - Lancelot fighting for Bagdemagus

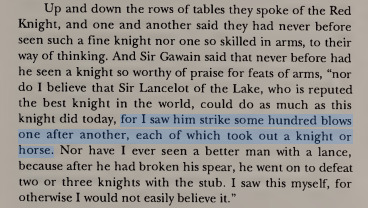

Vulgate Cycle - A knight's POV of Lancelot fighting for Bagdemagus

Vulgate Cycle - Lancelot as the Red Knight

Vulgate Cycle - Gawain's POV on Lancelot disguised as The Red Knight

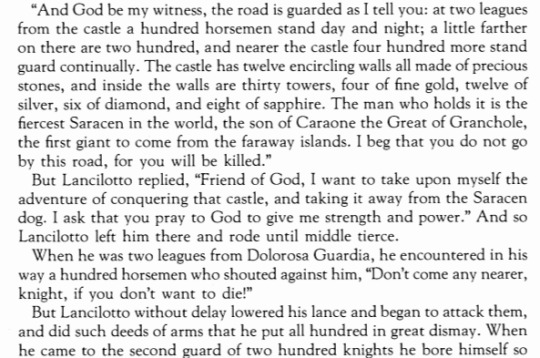

Tavola Ritonda

Gawain (not accounting for his Solar-based strength)

[...]

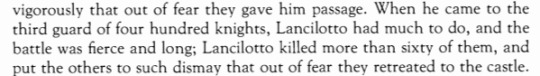

De Ortuu Waluuanii

Diu Crone

Tristan (Another character with superpowers and magic, but we'll keep it short)

Tavola Ritonda Bonus: Tristan can JUMP really, really high while injured:

I

Le Morte D'Arthur

#the superhuman feats of the knights of the round table#if any of you are wondering why morgan le fay can't just takeover camelot#modern arthuriana take notes#except fate#fate franchise is sort of lore accurate#king arthur#sir lancelot#sir gawain#sir tristan#sir kay#sir bedivere#pa gur#vulgate cycle#tavola ritonda#le morte d'arthur#welsh mythology#de ortu waluuanii#diu crone#nennius#historia regum britanniae#idylls of the king#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian legends

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So let’s say one of your listeners’ whole knowledge about Arthurian legends is that there was King Arthur, knights, Round Table and Grail. And they were like: fine, doesn’t matter, I will certainly enjoy Camlann anyway. And let’s say that after two episodes they did realise that it matter to them and they do have a deep personal need to actually know something more. What would you recommend them to read to learn more (or like anything) about Arthurian legends?

HI!!!!! Well, in this hypothetical situation, first of all I would say thank you very much to this listener for caring enough to ask.

Second, my big recommendations would be Le Morte d'Arthur by Thomas Mallory (maybe the most famous Norman version of the stories) and The Mabinogion, translated by Sioned Davies (the most Welsh version of the stories!). In particular I'd recommend this listener read up on Culhwch ac Olwen and Peredur, which have been referenced so far. I'd also strongly recommend this person read Gawain and the Green Knight (I like Simon Armitage's version, which is also available as an audiobook).

If this person wanted to go further, they could also read translations of Chretien de Troyes' chivalric romances, Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Brittonum, and medieval Welsh poetry found in the Red Book of Hergest and the Black Book of Carmarthen.

I will say Camlann is (very much on purpose) a chaotic mish-mash of Arthurian legends and British folklore. In some places we run very close to 'the canon', and in other places we throw it away completely. Sometimes I'll be referencing pretty obscure bits of Arthurian canon, sometimes we'll be bringing up fairly commonly accepted stuff.

I hope this hypothetical listener has fun!

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do I spy an Arthurian reference?

they can't do a best world flag bracket because Bhutan would destroy every other country and it would be too embarrassing

#okay not entirely arthurian the Mabinogion & Historia Brittonum did it before Geoffrey of Monmouth#Sorry.Sorry!#anyway in that case red dragon wins#i love them all however#whoops my childhood dragon phase is showing#here be dragons

31K notes

·

View notes

Photo

As of this week, I'm back from the Welsh mountains of Snowdonia, where my family and I went three weeks ago for a harp festival in which my daughter was participating. We spent most of our time in the castle city of Caernarfon, where the festival took place, and stayed across the street from a really big, really lovely old church at the base of Twthill, “Wales’s smallest mountain,” site of a Yorkist victory during the War of the Roses.

One of the days that we were there, I took a bus to nearby Bedgellert, ostensibly named for a noble but unjustly murdered 13th century dog, and set out to reach the top of Dinas Emrys, which lay outside the town and near a defunct Victorian copper mine (which I also crawled around in).

(outside the mines, before I started walking)

I wandered through a lot of countryside, woods, and sheep farms. The standard Welsh joke is "Don't like the weather? Wait five minutes," and that was the case - ten minutes heavy wind and rain, ten minutes sunshine, off and on for about four hours.

In the next pic, you can see the hillock of Dinas Emrys from before it crests upwards...

...and here it is from the top. The tree sits just outside the tower ruins (the pit to its immediate left).

I've never had such a beautiful walk to such a satisfying end. Not only was the peak gorgeous, but it also had the bonus of being a historical/mythical destination right up my alley.

The top of Dinas Emrys is where the oldest English/British histories (the 9th century Historia Brittonum and Geoffrey of Monmouth's famous History of British Kings* place the tower of Vortigern (and subsequently Ambrosius, in many versions the older brother and predecessor of Uther Pendragon), which in the legends had to be rebuilt numerous times because of the red and white Dragons that fought at the pool below it and which were taken by a (then young) Merlin as an omen for Welsh/Briton victory over eastern invaders.

*My pal Benito Cereno is currently translating Geoffrey's book from Latin, with some commentary, on his Patreon, and you can read his translation of the story here.

The sun was finally (consistently) shining by the time I got to the top, so I took off my shoes and socks to dry them, lit my pipe, set up my easel, and did some sketches of both the tower ruins and, once I climbed down to it, the hidden pool below.

I was quite happy with the travel easel I'd built and carried for the last eight or nine miles, until the heavy wind took it off the side of the mountain and broke it. It's fixable, but not without tools that I didn't have in the mountains, so that was that.

I haven't finished most of the Dinas Emrys sketches - like a lot of my travel stuff, I pencil (and sometimes ink), throw a couple of spots of color, and take photos to use as reference, so that I can do more pieces on a limited traveling schedule. But I'm looking forward to finishing the drawings of the pool especially - it felt like I was in a fairy tale down there, and I hope I can convey it (although the leafless, windswept [I think] hawthorn trees, reaching toward the pool like hands, aren't like any trees I've ever tried to draw before this trip, and trying to get them right is part of the reason I ain't yet done).

The trip back down was less idyllic, partially because going down over wet rocks is, while less strenuous than going up, more demanding of care and attention, so I had to watch my feet more than the surroundings, especially having taken a fall up by the ruins. But I'd count the trek as one of the genuine high points of my life. I was elated and in awe for hours at a stretch, and absolutely overcome with the beauty of it. And, while the rain might've been unpleasant and chilly at times, it meant that the sun fought through water and clouds to create the most incredible vistas, and the rain meant that the colors of the mosses and grasses were at their most vivid.

I'll have castle drawings down the line, too, and some others from around the harbor town, and I can't stress how much we enjoyed our time in Wales.

I did take a few days to go up to Leeds, do a signing at Traveling Man, and visit the Royal Armouries a few times to do drawings. One of the folks who came to the signing, Dr. Tzouriadis, is a currator at the armouries and was kind enough to give me a tour on my last day in Leeds, including getting to see the research library, which I now know to make an appointment for visiting the next time I'm there (I likewise learned about the British Library reading rooms and research collection, and got a card for it for the next time I'm in London).

Dr. Tzouriadis was incredibly generous with his expertise, and I learned or clarified a lot of really neat things that'll influence how I draw swords and armor in the future. And I've had some practice this trip thanks to the incredible collections with which I had a chance to spend some time.

Each day over the month of May, I'll be posting one drawing of a sword (or other edged weapon) from either the Royal Armouries, the Tower armory, or the British Museum. It's jumping the gun a bit, but here's a sneak preview of the first one:

They're toned with a single color (indigo) so that I can collect them into a book in black and white and make both its manufacture and selling cost a bit less than I could were I to do color - it also cuts down on the time spent making them. I'll likely put them up for sale each day as I post them, likely for the same price (50 plus shipping?), as a means by which to recoup some of the (substantial) cost of the trip.

While in Leeds I also got to meet cartoonist James Lawrence, have dinner with cartoonist John Allison, and briefly stop by OK COMICS in the arcade, which was an incredible store with an amazing selection of books.

After Wales we went to London (Penny's first time), and Penny was unfortunately ill for a couple of days, so I spent time at the museum doing sketches, and visiting the library treasures gallery. We saw a couple of musicals that Penny was keen on seeing, went to Charles Dickens's house, visited the Tower, ate some cheap meat pie with jellied eels in Greenwich, toured Westminster and St Pauls (I went to a Eucharist service at the latter, as well as one in Wales in a lovely little church built into the castle wall more than seven hundred years ago), and a handful of other things, including seeing the Tempest at the Globe Theater - my first time seeing a play at the Globe, and my first time seeing the Tempest performed.

I also got to visit a whole store devoted to Tove Jansson's MOOMIN, where I got a mug and a biography of Jansson, and it was next door to the Benjamin Pollock's Paper Theater shop. I went to London disappointed that the Pollock paper theater museum had closed only months before after decades of operation, and didn't know that there was an (unaffiliated since the 80s) shop, so stumbling upon it was a real treat (stumbling is how I like to do cities - I walked crisscrossed the town between the Euston and the river and found some great shops, including a lot of bookstores).

Now that I'm home, I'm very keen to get back to work. I'll be doing Patreon commissions, coloring a book for my friend and frequent collaborator Kyle Starks, and just settling back into being able to work, which I missed an awful lot despite the wonderful trip.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Start of a running list of my opinions on things I have read/watched/listened to for Arthur Project research (or for “research” read: entertainment)

Le Mort D' Arthur (15th century): Alternates between boring as hell and unintentionally looney toones. Sometimes both at the same time (entire page thats just a sequence of knights getting knocked off their horses and then getting new horses and then getting knocked off their horses again) I'm still only 30 pages in despite my best efforts so this will probably reappear later in the list.

Historia Brittonum (8th century): Only one relevant paragraph. Extremely informative in very few words. fucking superb.

OSP’s King Arthur and Arthur’s Knights (YouTube videos, 2018): Not very in-depth, obviously, but enjoyable and helpful for listing a bunch of the more popular sources

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

op i think you should read annales cambriae, the mabinogion, nennius "historia brittonum", geoffrey of monmouth's "historia regum britanniae" and vita merlini robert de boron's "prose merlin", the black book of carmarthen and the vulgate lancelot-grail cycles and then thomas malory's "le morte d'arthur"

there is no balinor, medieval!merlin's father was a either a demon, a succubus or a roman consul that impregnated some local noble or rich merchant's daughter

merlin is uther and his king brother's main advisor and biggest ally and therefore of the same generation as them. therefore he has more experience being an advisor and is more respected in the realm. So if you go ahead and make another story about merlin and arthur of the same age, you'll just end up remaking what uther-merlin have always looked like in the earliest stories.

le morte d'arthur barely deals with merlin's origins. you have to go to the earliest ones if you want better more badass and more nuanced merlin personas

truly yours, a concerned medieval!merlin fan.

yep i know the balinor bit ofc, i was talking about using his character from bbc merlin for plot reasons.

i know that the merlin from bbc show and traditional merlin in the legends have barely anything in common. in the post you likely saw i was talking more about writing a story that would follow a more classic version of events of arthur's life while using characters from the bbc show and their characterisations

also, thank you for your list of recommendations, it has been in my plans for a long time to get some of those texts but it's kinda hard to find them where i live sadly

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

merlin becomes the lebron james of east wales

0 notes

Note

I apologise if I'm way off for assuming you'd know about this but

what's the origin of the whole "Arthur is gonna come back at the darkest hour and fuck shit up" thing? I went Googling to try and find the original/earliest version of the prophecy (in the hope that it's in Latin haha) but I couldn't find anything that matched my impression of the modern interpretation anywhere

is there a definitive source/sources or is it more of a folk legend that formed over hundreds of years?

or is the popular culture interpretation just way off, cus that wouldn't surprise me, like with Greek myths etc.

I enjoy questions like these, so don't worry! I wouldn't call myself an expert, but I have read into this a good bit as a personal thing.

Firstly, this comes Y Mab Darogan/ Y Gŵr Darogan/ Y Daroganwr, which is mostly what you speak of, a "destined" Son/Figure who "reclaims" Britain/Prydain for the Celts. While now a days people think of King Arthur (and I think it was originally attributed to being him, in Armes Prydein Vawr by the Bard Taliesin(?)) THOUGH this title has been applied and given to multiple other figures since then, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, and I believe Henry the seventh? In wales, However, the actual most famous one would undoubtedly be Owain Glyndŵr, who everyone who was born in Wales should (as in i'd be surprised if they didn't) know about.

Sorry for the ramble, moving on the real part of the question, what's the origin? Well, it could be Armes Prydein, but Arthur doens't actually appear in this early book, or apparently any others. His association with it is, assumedly, based off Historia Brittonum as he fought the Saxons, according to it. The earliest I can find right now in relation to King Arthur specifically coming back at all is from the 12th century, or claims of this sicne I can't find a copy of the book online right now. It's first mentioned at all by William of Malmesbury in 1125 and then Hériman of Tournai in De miraculis sanctae Mariae Laudunensis.

Besides that, there was William of Newburgh (1136–1198) who said, "most of the Britons are thought to be so dull that even now they are said to be awaiting the coming of Arthur." 1 2

Hope that answers the question well enough. If not, let me know and I'll try again haha.

#wales#cymru#mythology#welsh mythology#mytholeg#mytholeg Cymru#ask#volumina-vetustiora#i had to do this on my phone because desktop threw a fit whenever i tried to submit lol

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you've been doing some background research on Arthurian content, did you know that a lot of the mythos involving the Round Table, chivalric romances, & the Holy Grail was developed by 12th century French poet Chrétien de Troyes; 400 years after the core Arthurian elements were first recorded in the Historia Brittonum?

Yeah, one of the first things I did when I started researching for the fic was to get a comprehensive look at the origins of the mythos! I found an ebook in the library that had a super digestible summary of the timeline, covering Historia Brittonum and Malory of course, but ALSO going into the Welsh and Celtic influences that predated Christian influence, which was SUPER COOL. Unfortunately the book only focused on the King Arthur character, and didn’t go into much depth about the other knights, ladies, faeries, etc.

The book didn’t go too in depth about Chrétien de Troyes other than to mention the titles of his contributions, so that’s another area for further reading I want to get into. I know him best for the story of Sir Yvain and the Lion, which was one of the first stories I stumbled across that just screamed HTTYD.

Like. Yvain meets the Lion by cutting its tail off??? (albeit it was to save it from a dragon where Hiccup was trying to kill Toothless at first alsjdfkalsdjf) and then the Lion becomes his best bud???? AND IT’S THROUGH THIS FRIENDSHIP THAT YVAIN IS REDEEMED??? AAAHHHH

At one point the Lion gets injured after defending Yvain, and Yvain makes a bed of grass on the back of his shield and literally drags the Lion to a town, then cuddles up next to him while he’s healing up, even though everyone’s hella scared of this wild animal BAWWWW

Other than that, I haven’t looked to deeply into his work! I made a bunch of notes on what early influences pre-dating Malory and Geoffrey of Monmouth that I wanted to use in combo with modern retellings that most people are familiar with!

#ask#theepsizet#the lights of avalon#tloa#I haven’t watched merlin so any similarities are accidental alsdjkflasdkjf#alka reads arthuriana

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking about the original folkloric Arthur

Not a king, not a knight, but a great hunter and a humble soldier.

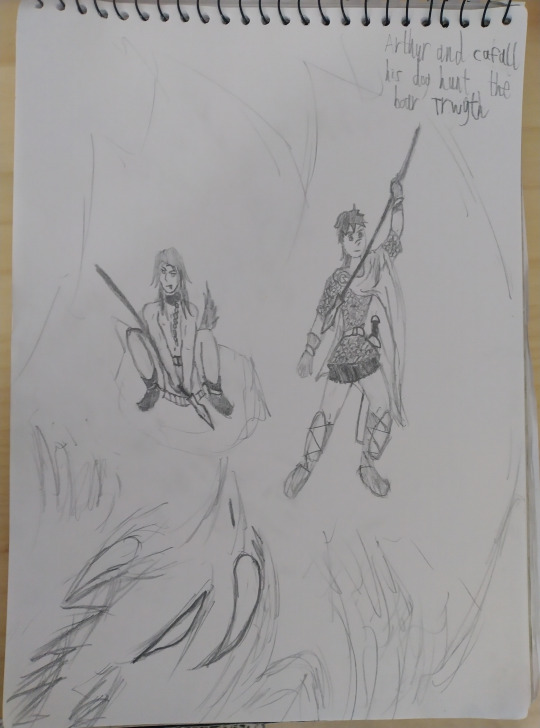

I'm not really an artist but I spent all yesterday filled with the urge to draw this version of the character, so here's a post that's 50/50 doodles and historiographical rambles about him.

I wanted to do scenes depicting the feats this earliest 9th-century Welsh folklore describes him doing, so first I needed a design for the guy.

Notes on my choices and historicity:

-These earliest local Arthur legends are recorded in an appendix to the Historia Brittonum (c. 830), where he is referred to as simply "Arthur miles" ("the soldier"), a protector-figure in south Wales. The name Arthur is thought to derive from the Latin "Artorius", so I've just written it here to create a consistent Latin version of the name and title. That doesn't mean it was his "real name"; there probably wasn't a specific real guy. Some have floated a 2nd-century Roman general named Lucius Artorius Castus as the "real king Arthur", but there's a 600-year gap between his life and any mention of Arthur, so that's extremely unlikely.

-The visuals are a mix of historic (he wears a tunic, a mail shirt and a cloak with an early medieval brooch) and the kind of anime boy that appeals to me personally. I can't tell you why I was so sure he had to be black-haired, it just felt right. I tried to avoid depicting him as too elite a warrior; I imagine the necklace was obtained as plunder from a raid. For his build, I wanted him to have some mass but not to look like a modern gym bro, and that crashed headfirst into my predilection for messy twinks, and I ended up drawing him (and the other characters here) with kinda "curvy anime babe" proportions, I guess, lmao

-The 10th-century Annales Cambriae say that at the battle of Badon, "Arthur carried the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and three nights on his shoulders and the Britons were the victors". This is probably referring to to a shield design, but I thought it'd be fun to interpret it as a back tattoo. The practice is attested as being practiced in the north of Britain from a 786 synod in Northumbria. The English clergy weren't fond of it and actually tattooing a cross isn't attested until the crusading era, plus from a modern perspective the vibes of a guy with just a big Christian tattoo are a bit questionable, so I decided to pair it with something else. Earlier Roman accounts of Briton tattoos mention animal shapes, and Welsh legends often depict people or their souls becoming birds (early modern Cornish folklore even held that Arthur survived in the form of a bird), so I went with a wing-pattern.

-The precursor to Excalibur, Arthur's sword Caledfwlch ("hard-cleaver", Caliburnus in Latin, Calesvol in Cornish) isn't magic yet, and his spear and dagger are given equal prominence, so I depicted it as the kind of straight sword common at the time, derived from the Roman spatha design.

-One of the two prior stories recorded in the HB is Arthur's fighting and killing his son Amr ("fab Arthur", "son of Arthur", is my translation into Welsh); I drew Amr in a half-tunic/half-dress because, again, I just kinda wanted to

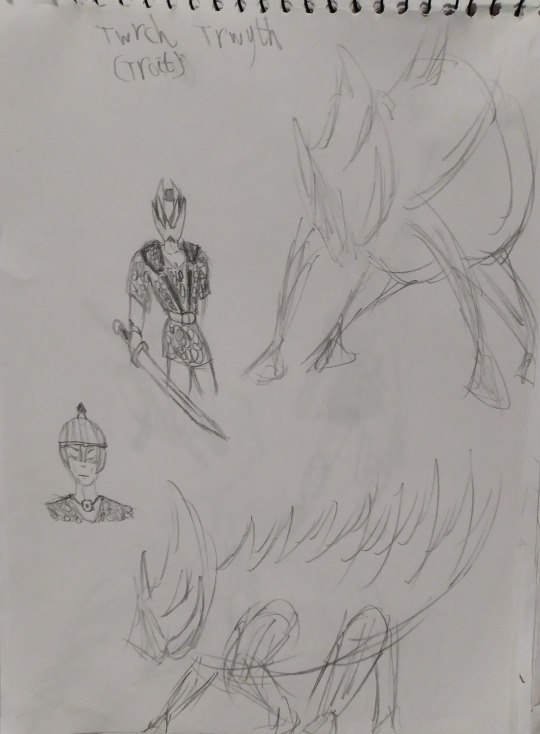

The other story involves Arthur hunting the great boar Twrch Trwyth (Troit/Troynt), so that was the next thing to design:

This is very cool to see referred to this early, because the hunt of the Trwyth is the climactic set-piece of Culhwch ac Olwen (c. 1100), the most complete Arthurian tale we have from the period after the Historia Brittonum transformed him from a minor local figure into a magical warrior-hero for all the Britons and centrepiece of Welsh legend, but before Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae further began his transformation into the chivalric king popular in France and across Europe.

In Culhwch, Trwyth is a king who was turned into a boar by God as punishment for his sins, so I came up with a human design as well as a big pig design. The king in question was probably intended as a Briton, but I thought it would be fun to depict him as a Saxon, Arthur's enemies in the HB, especially as Saxon warriors often wore boar-crests on their helmets. I did one take with a mostly historic boar-helmet, and one more fantastical, almost like a boar-themed Kamen Rider helmet, as if rather than becoming an actual boar he became this more fearsome but still humanoid warrior.

I also made his sword slightly asymmetrical, to mirror the seax knives that gave the Saxons their name. Their actual main battle swords were straight, but I thought it was a fun touch for this magical tyrant.

As for the boar-form design, I like depicting monsters with sketchy outlines, like they aren't fully solid creatures of this world.

And that's how we get our first scene proper!

The legend recorded in HB says that when Cabal (Latinisation of Welsh "Cafall"), Arthur's dog, was hunting Troynt (Trwyth), he left a paw-print in a stone, which Arthur then assembled a cairn under, and if the paw-print stone is ever removed, within 24 hours it returns to the mound. (Cafall is also featured in the version of the hunt in Culhwch!)

Anyway, I can't really draw animals that aren't big scary creatures, so I didn't want to draw an actual dog. So since I'd already turned Trwyth into a guy, I figured why not just turn Cafall into a guy too? Plus, I get to draw a guy in a collar with a dog-tail and a little fangy. So win-win, really.

I also wanted to draw a version with the human Trwyth, and I figured I'd combine that with the story of Amr, and just do a page of swordfights:

"...on fatal field / we fended our lives, as the ranks clashed in battle / and the boar-crests rang..." -Beowulf

The Amr (or Amhar) story relates that Arthur built a tomb for his son, and that every time it is measured it comes up as a different length.

The fact this is such an early story is also very interesting, because one of the most famous parts of post-HRB chivalric Arthur is the killing of his son Mordred. Early Welsh references to Mordred (Medraut or Medrawd) portray him entirely positively. I do wonder if when Mordred became the more famous son of Arthur the story of Amr got folded into his, but we don't have evidence to do more than speculate.

I also now realise that my human Trwyth looks a lot like a Ringwraith, and honestly the more medieval lit I delve through the more moments of "oh that's why that bit of Tolkien is like that" I have.

Those were what I originally wanted to depict, but in doing them two more ideas occurred to me. One was depicting the Arthur of the Historia Brittonum itself (not just the pre-existing folklore it recorded), this local hero plucked into a much grander stage, cast as a pseudohistorical general leading his people against the Saxons.

This one came out very "edgy teenager on Deviantart", but fuck it, kill the part of you that cringes and be free, right:

The title comes from one of the medieval Welsh "triad" texts, each one a short line listing the "three great X of the Isle of Britain" to help bards remember. Arthur is referred to in many of them, here as one of the "Three Red Reapers of the Isle of Britain". I thought that was a good fit for his war-hero portrayal here. Also I tried moving the cross-tattoo lower down to make it sluttier.

HB's Arthur is an interesting middle ground. He's leading the Britons as a whole, but he still has one foot in his humble origins. He's named as Dux Bellorum, "battle-leader", and it's specified that the kings of the Britons were under his leadership although he was less noble than them. It's only somewhere between the grander Welsh legends that sprung up after this and the HRB that he would get upgraded to king.

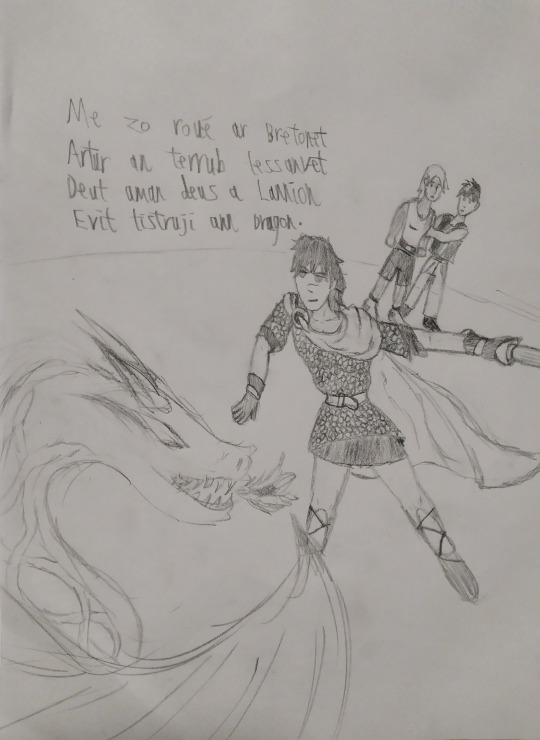

For the final picture, I was inspired by a much more recent piece of Breton verse, a 19th-century gwerz (ballad) telling of Arthur arriving in Brittany (on account of being king of all Britons) to slay a dragon and getting help from Saint Efflam. The core story, though, is remarkably consistently preserved from the Vita Euflami, the original saint's life written around 1100. I was captivated in particular by the verse in the gwerz where Arthur announces himself:

Me zo roué ar Bretonet Artur an terrub lessanvet Deut aman deus a Lannion Evit tistruji ann Dragon.

I am the king of the Britons/Bretons Arthur, known as the terrible Come here from Lannion To destroy the dragon.

For one, the way the lyrics flow in the Breton just kinda goes hard, but the bombastic tone and the length of time the story was transmitted across brought a scene vividly to my mind, inspired by the persistent story of Arthur's prophesised return: Modern travellers in the Breton countryside being set upon by a dragon, only for Arthur to miraculously appear with this declaration, defeat the beast and vanish, his original task as hunter and protector fulfilled once more.

So I drew that! Once again, I like sketchy impressionistic monsters. Also, I think the people in the back are lesbians, but that's less of a conscious decision and more just what happens when you ask me to draw two people.

And that's what's been occupying my mind for the past few days! There's a couple more things I could do. Cai and Gwenhwyfar (precusors to Sir Kay and Guinivere) are characters I'd love to whip up designs for, and there's a bunch of really wild scenes in Culhwch. But that'll only be if I'm still feeling this specific creative energy.

Thanks for reading!

12 notes

·

View notes