#herbivory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

TSRNOSS, p 541.

#cold water fish#zinc deficiency#acetone#starvation#ketoacidosis#McCay Effect#lipofuscin#parenteral nutrition#potassium deficiency#manganese content of tea#superoxide dismutase#herbivory#ascorbic acid synthesis#oxidative stress#human height#Italy#Eskimoes#Atkins diet#Trobriand Islanders#electron charge#hibernator#beta radiation#diving mammals#methane#silicosis#deserts#horse latitudes#Keshan disease#emaciation#hyperlipidemia

0 notes

Text

The issue of corallivory or similar behavior - for example, biting the mantles of clams - among the tangs and their cousins, is an old one, and one subject to armchair speculation by aquarists, when confronted with the behavior. Interestingly I have found some ichthyologists in the past, to be dismissive of reports, and observations, of such behavior by tangs. Doubtless this is motivated by the knowledge that tangs are, on the whole, very herbivorous fishes, and represent such niches par excellence. Nonetheless myself and many other people, have ourselves witnessed incidents of acanthurids and siganids, biting anthozoan tissues. Either tissue was ingested deliberately, or it was not, but in any case, polyps or colonies were observably scarred in the incidents.

Over many years, aquarists have oft speculated that these feeding activities are a form of substitute behavior, for natural grazing and browsing opportunities, that are usually lacking in our aquaria; or that such algivorous fishes instinctively recognize coral holobionts as an appropriate fallback food, should their preferred diet become unavailable during lean times. It has even been suggested that it is instead a playful behavior, or an expression of frustration, rather than a feeding behavior at all. Before we can answer the question of what makes an algivores turn corallivore, we might well ask, are tangs and their kin - henceforth, the 'tang-likes' - strictly algivorous in the first place?

Tangs or acanthurids and their kin, of which the siganids are most relevant to aquarists, are a natural clade of fishes sharing similarities through common descent. The basal division of the clade is between the siganids, or genus Siganus, and the other genera. These include Zanclus, the famed Moorish idols; Luvarus, the pelagic member of the group; and the acanthurids proper. These latter include Naso, diverging at the base; Prionurus a node later; the clade containing Zebrasoma and Paracanthurus, a node after that; and then the acanthurin nexus of species assigned to the semi-natural genus Acanthurus, and the subclade of bristletooth or combtooth tangs, Ctenochaetus, which possess mobile, flexible teeth paralleling those of grazing blennies.

Despite the well observed role of acanthurids as grazers, not all of the species are. Within the genus Naso, the most protomorohic species are herbivorous, with a secondary shift to zooplankton feeding as a derived condition. Prionurus, Zebrasoma, and the acanthurins, are all basically herbivorous, as are most of the siganids. Paracanthurus is another zooplanktivore, but using a similar reasoning - called phylogenetic bracketing - Paracanthurus, too, had herbivorous ancestors. Among the acanthurins, two species have also, independently of one another, crossed into carnivorous planktivory, these are 'Acanthurus' mata and 'A'. thompsoni.

Even considering the evolution, at least four times, of plankton feeding among the acanthurids; and the faculative consumption of gelatinous plankton by siganids; it still feels strange that Luvarus is basically a jellyfish eating, pelagic sort-of tang, growing to 150 kilograms. Again, the fascinating Luvarus is divergent from an ancestral, benthivorous habit. Though feeding on similar items happens also to be a specialty of N. hexacanthus, and A. thompsoni. Zooplankton eating members of this clade tend to evolve a more slender form, and weaker teeth and jaws, because they are no longer used in strenuous grazing behaviors. Also planktivorous tang-likes become short faced, lacking the need of their grazing relatives for a primitively lengthened face, similar to those of many herbivorous mammals on land.

Zooplankton feeding is a form of carnivory, but it is very different from rasping or nipping corals, or clam mantles, which belong to the category of carnivorous benthivory. The latter tendency does exist among the tang-like fishes, and is epitomized by Zanclus, the sponge specialist of the group. Zanclus does consume algae still, and will also eat certain anthozoans. But the animal component of its diet, is predominantly composed of sponges. At least some of the Siganus species, especially S. puellus, are now known to extensively consume spongal life, and other benthic fauna. S. puellus is atypical in the extent of its spongivory, and seems thusly to parallel Zanclus. Therefore it is clear that the tang-like diet, can easily shift to foraging, benthic carnivory from an ancestrally 'herbivorous' ancestral niche. And that the ancestral tang-like diet, was more omnivorous than simple algivory, which was nonetheless the primary source of food for these hypothetical ancestors.

Zanclus and Luvarus each remind us of the evolutionary potential of tangs and their kin; deviating as they do, from their acanthurid and siganids relatives - and it may be inferred, their last ancestors - but following such different evolutionary paths. At least a species of siganid, S. rivulatus, opportunistically preys upon jellyfishes and ctenophores, accompanied by a zebrasomin species, Z. desjardinii. But it is the behaviors of grazing and browsing carnivory in this clade, that most indicate their potential riskiness around ornamental corals and clams. Foraging Siganus sp. are well documented to consume sponges and tunicates, with reports of their feeding on brain corals, and even a toxic alcyoniid, Sarcophyton. Conversely, at least S. argenteus, S. canaliculatus, and S. javus, are all pure herbivores, and S. javus has been determined not to eat the antipatharian corals it bites at. Some other siganid species - S. vulpinus, S. spinus, S. doliatus, S. corallinus - ingest such small mass of sessile animals tissues, it's unclear if they ingest it purposefully. S. lineatus, S. punctatus, and S. punctatissimus, are all confirmed to consume sessile animals in the wild.

A certain paper recently investigated the dietary scopes of a number of siganids and acanthurids. For example, Zebrasoma scopas consumes some benthic invertebrate material, but very little of it; whereas Z. veliferum apparently does not. In a similar vein, Naso lituratus was not feeding on benthic animals, though N. unicornis was a slight consumer. (Incidentally this paper identifies no animal materials in the diet of S. spinus either.) A true Acanthurus species, A. lineatus, consumes some benthic faunal material, whilst A. nigrofuscus and A. nigrioris, which are also truly Acanthurus species, were estimated as strictly herbivorous. The species 'A'. leucopterus supposedly consumes some benthic animal material, although its relative, 'A'. nigricans supposedly does not. Whereas the convict tang, 'A'. triostegus, appears to be a strict vegetarian. (Properly the genus Acanthurus may only include fishes that are closer to its type species, A. sohal, than that of its sister genus, Ctenochaetus strigosus.)

The derived acanthurin Ctenochaetus strigosus, foes not forage foods of animal origins, whereas C. striatus does consume them, as a part of indiscriminate feeding behaviors. Ctenochaetus belong to a group of supposed Acanthurus fishes that have muscular stomachs, which have been compared to the gizzards of birds. Among such species, 'A'. nigricauda, olivaceous, and pyroferus are regarded as vegetarians, and blochii as almost so; but more interesting are the outright omnivorous 'A'. dussumerieri and xanthopterus, both of which extensively consume foods of benthic animal origins. Tangs of this guild will even eat carrion, because they take fish flesh when it is used as angling bait. It is as though the apomorphic stomach of this clade, has allowed new trophic niches, towards increased carnivory, and also towards the specialized grazing of biofilms, in the craniofacially specialized genus Ctenochaetus.

I'm not entirely sure how reliable the information actually is. Not least because all such studies, by their nature, need to depend upon a sample size. Fish can also shift through dietary niches with maturity, or in tune with the natural seasons. There is too close a kinship between some of the tangs that are supposedly the strictest vegetarians, and those that are confirmed to sample benthic animals in the wild. Yet subtle dietary niche partitioning, can allow related species to exist in the same environment. Placed into an unfamiliar environment, and often in the absence of their natural food preferences, it's no wonder that tangs and siganids can begin to taste corals as a substitute for natural behaviors, not least because coral holobionts are often rich in photosynthetic symbionts. My intuition is that those species which nip fronds of fleshy macroalgae, are predisposed to bite fleshy polyps and wavy clam mantles; and those of grazing habits, to try biting down on massive, encrusting, and laminar growth forms.

There is some public fascination upon seeing footage of deer consume birds, or even chickens - by no means strict vegetarians! - catching mice and sparrows. In real life animal feeding behaviors are subject to personal and situational variation, and animals do learn what is or isn't food, by way of experimentation. Some of the images and videos of herbivores eating other vertebrates, are statistical tail end effects, and not highly probable events. One fine example might include a hippopotamus, killing and eating an impala Other instances are just low key but widespread natural behaviors, that many people are unaware of. My informed intuition, based upon the evolution and ecology of the tangs and siganids, is that both phenomena are variously in play.

#siganids#acanthurids#tangs#corallivory#coral eating#reef safe#surgeonfishes#spinefoots#rabbitfishes#foxfaces#herbivory#omnivory#behavioral problems

1 note

·

View note

Text

Subterranean Wonders: The Fascinating Resilience of African Geoxyles

Geoxyles, a distinctive feature of Afrotropical savannas and grasslands, are a type of tree that survives recurrent disturbances by resprouting from large belowground woody structures. A new study by Anya Courtenay and colleagues, published in Annals of Botany, found that underground trees inhabit significantly distinct and extreme environments relative to their taller, woody tree/shrub…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

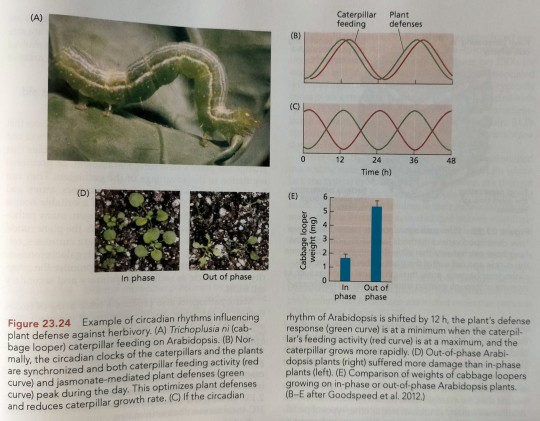

This hypothesis was recently confirmed by a study of the interactions between Arabidopsis and cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni), a generalist lepidopteran herbivore (Figure 23.24A). (...) To test whether the plant circadian clock enhances defense against insect pests, herbivory was compared in Arabidopsis plants whose jasmonate-mediated defense responses were either in phase (Figure 23.24B) or out of phase (Figure 23.24C) with the circadian rhythm of cabbage looper feeding activity. After allowing cabbage loopers to feed freely on the plants for 72 h, plants whose defense responses were in phase with the loopers had visibly less tissue damage than plants whose circadian rhythm was out of phase with that of the insects (Figure 23.24D). As a result, cabbage loopers that fed on the phase-shifted Arabidopsis plants gained three times as much weight over the same period as the synchronized control plants did (Figure 23.24E).

"Plant Physiology and Development" int'l 6e - Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Møller, I.M., Murphy, A.

#book quotes#plant physiology and development#nonfiction#textbook#arabidopsis#cabbage looper#caterpillar#trichoplusia ni#circadian clock#herbivory#jasmonate#circadian rhythm#insects#in phase#out of phase#synchronized#phase shift

0 notes

Text

I wanna make a Therian themed cookbook so bad some day. Would that even be doable as a community project. Yes it's so I can ramble about ways to eat raw meat and bugs again.

#probably not including fictionkin bc that'd be a bit harder#my idea is more... based on carnivory herbivory scavenging etc#how to replicate diets human can't quite follow#otherkin#therian

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbivorial: A gender that is itself herbivory / herbivore.

[ Tag List: @ophelia-thimgs, @liom-archive, @hoardicboy-main, @radiomogai, @acidicwolf16 ]

#draedons arsenal : coining post#mogai#mogai identity#mogai label#mogai blog#mogai coining#mogai term#liom#liom term#liom label#liom coining#coining post#flag coining#identity coining#mogai gender#gender coining#liom gender#xenogender#neogender#herbivorial

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

also, all whales are carnivores

rorquals like blue whales and minke whales eat krill, which is meat, and some also eat fish, which is also meat

right whales eat pelagic copepods, which are meat

grey whales eat benthic copepods and other invertebrates living in the seafloor substrate, which are also meat

sperm whales and beaked whales eat squid, which are meat

orcas eat seals, salmon, porpoises, sharks, penguins, moose, all of those too are meat

river dolphins, oceanic dolphins, and porpoises eat fish

all cetaceans

all of them

Sperm whale mimics a spinning diver.

276K notes

·

View notes

Text

A rare species of tree cactus has gone extinct in Florida, in what is believed to be the first species lost to sea level rise in the United States, researchers said Tuesday. The Key Largo tree cactus (Pilosocereus millspaughii) was restricted to a single small population in the Florida Keys, an archipelago off the southern tip of the state, first discovered in 1992 and monitored intermittently since then. But salt water intrusion caused by rising seas, soil erosion from storms and high tides, and herbivory by mammals placed significant pressure on the last population.

Continue Reading.

#Science#Plants#Environment#Climate Change#Extinction#Pilosocereus Millspaughii#Key Largo Tree Cactus

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The only science news that matters: today I met an NB new professor who specializes in grassland herbivory and fire

Back in the day I could just tweet them from my reasonably successful account “HELLO FELLOW PRAIRIE QUEER” but how do I let them know we are friends now other than politely asking questions about their research in person?

What are the chances they’re on tumblr 🤔🤔🤔

499 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new Carboniferous edaphosaurid and the origin of herbivory in mammal forerunners

Abstract

Herbivory evolved independently in several tetrapod lineages during the Late Carboniferous and became more widespread throughout the Permian Period, eventually leading to the basic structure of modern terrestrial ecosystems. Here we report a new taxon of edaphosaurid synapsid based on two fossils recovered from the Moscovian-age cannel coal of Linton, Ohio, which we interpret as an omnivore–low-fibre herbivore. Melanedaphodon hovaneci gen. et sp. nov. provides the earliest record of an edaphosaurid to date and is one of the oldest known synapsids. Using high-resolution X-ray micro-computed tomography, we provide a comprehensive description of the new taxon that reveals similarities between Late Carboniferous and early Permian (Cisuralian) members of Edaphosauridae. The presence of large bulbous, cusped, marginal teeth alongside a moderately-developed palatal battery, distinguishes Melanedaphodon from all other known species of Edaphosauridae and suggests adaptations for processing tough plant material already appeared among the earliest synapsids. Furthermore, we propose that durophagy may have provided an early pathway to exploit plant resources in terrestrial ecosystems.

Read the paper:

A new Carboniferous edaphosaurid and the origin of herbivory in mammal forerunners | Scientific Reports (nature.com)

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Cotylorhynchus, a tiny-headed reptile, asks "Where do you work out?". Erythrosuchus, a huge-headed reptile, answers "At the library".]

Every time I see cotylorhynchus reconstructions the size of their head makes me so insane Like we have to be missing a piece of the puzzle or something there's no way it's head was so fucking tiny it can't be true

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

TSRNOSS, p402.

#impactors#nasal passages#breathing rate#sea lions#bends#buoyancy of enzymes#mutational load#Fechner's Law#plant toxins#herbivory#heterozygosity#function of fever#satyendra sunkavally#theoretical biology#cursive handwriting#manuscript#diairies

0 notes

Text

Growing Paw Paws from seed: 2024

Some of y'all may recall last year I made a Plant Profile post after finding my first Paw Paw (they don't really grow this far north in NJ so this was exciting). Well after eating the fruit I decided to see if I could propagate the seeds and I was very successful!

Below I'll describe my process and some tips, this was unconventional towards how I usually grow saplings but I was in my final year of a masters program, needed to be as cheap as possible, and this is probably easier for those of you in apartments

So you want to propagate paw paws? It's not hard it just requires a bit of understanding.

When I found my first Paw Paw I was on the University of Pennsylvania campus, I saw a tree in front of a multi-faith church and immediately recognized the fruit. My friends and I climbed up the branches to get some bigger fruits and then we basically ate them on a nearby bench.

Once I had the seeds (I started with 14, only 4 viable) I walked home and washed off any debris then I wrapped the seeds in a damp paper towel (wring out excess water) and placed them in a plastic bag in the fridge for 3ish months

Around February I decided to grow them, I had some extra cardboard pots I was starting oaks in (image 3: ps I hate these pots) and knew I could use this to to start the seeds, at the same time I asked a friend to grow paw paws so we had a diverse gene pool to produce fruit. Paw paws need deep pots because they develop a taproot that can easily reach 12" the first year, instead of buying multiple deep pots you can place disposable pots in a bigger container with soil. If you find like long/narrow containers those are your best option.

I used left over peatmoss (but loamy potting soil will be better) and placed them 1" deep each. I then cut off the bottoms of my small cardboard containers and placed those together in a deeper pot I had (image 4). You want to retain moisture, so also cover the pots in plastic wrap. Of course water enough to keep the soil moist that goes without saying.

Paw paws take about a month to germinate above the soil but still need the increased light levels. Keep an LED light on above it (these are very cheap to operate) They will start growing a taproot soon after you plant them and occasionally will break the surface, just try to keep it covered in dirt.

Once they appear above the surface (this was march-april for me), let them grow till they develop like 4-5 leaves before planting out. I kept them in my Frankenstein pots until about June when I had time to exchange with my friend (he grew like 18 with seeds from an online seller but stunted their taproots a bit).

Paw paws have a natural insecticide in their leaves, I didn't encounter any herbivory from both deer and insects but I left my best specimens in a sapling cage. I planted about 8 in my yard, all around 4 inches tall (image 5), in partial shade conditions. When you plant the sapling dig a little deeper than the taproot and leave soil around the taproot itself, it helps to have a deep trowel. For amendments, I mixed in richer compost soil with the native soil, but for a few I gave no amendment (I wanted to test if it made a big difference). Ultimately those which grew the most were in brighter conditions but they all did okay, my largest ended up being 15" (image 6) which is the same development as some nursery stock I've encountered for $165...

On a side note you're not supposed to move them once planted but I ended up having to do this with one. I did break the taproot in half, however this sapling still survived so these trees are a bit hardier than others have implied.

So, is this the best way to grow paw paws? No absolutely not. Is it cheap and basically using just garbage...yes! Try to grow your own :)

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

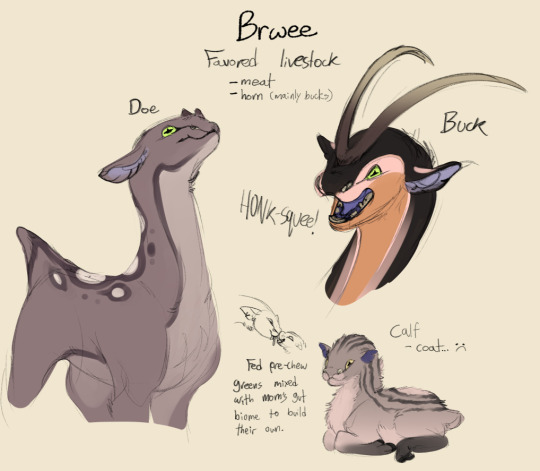

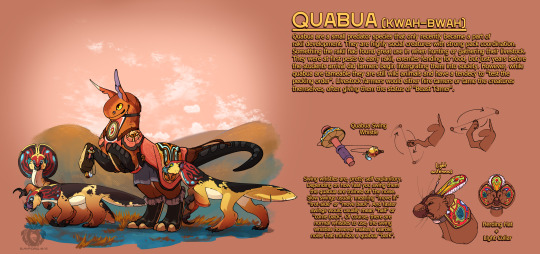

The relationship between rakii and animals is fairly utilitarian. If it's not useful, it's not worth the care, making having pets vastly unpopular. Some favored livestock mainly among the temperate regions are Bwree.

They are domesticated herbivories the rakii range for meat and the horn as they were useful for tool material and decoration. The brwee does are for meat and calves, which they can have up to three or four of. Brwee calves are born with a fluffy stripe patterned coat, which is useful for leather linings and insulation for boots and coats. And of course, meat. While Bwree may protect their young, the does are pretty r-selective as they will only feed and care for the strongest calves in her group. The average ditching 1 or 2 of their litter, which the rakii make use of.

And for the many they have, they use the help of tamed quabuas to herd them. Their hunting tactics and pack bonds became useful for the rakii around 15,000 years ago, so it's a fairly new development. However, wild quabua will often try to "test the pecking order" and tend to challenge the pack lead. Making them difficult as pets.

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

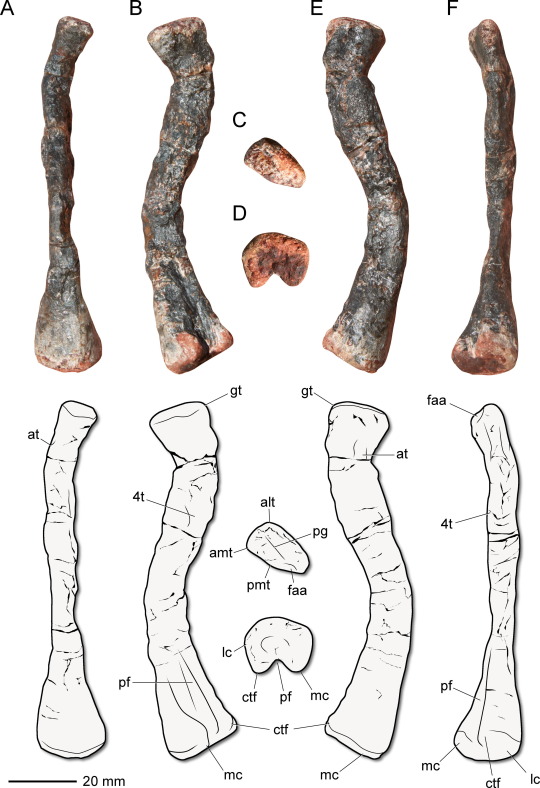

Gondwanax paraisensis Müller, 2024 (new genus and species)

(Type femur [thigh bone] of Gondwanax paraisensis, from Müller, 2024)

Meaning of name: Gondwanax = Gondwana king [in Greek]; paraisensis = from Paraíso do Sul

Age: Middle–Late Triassic (Ladinian–Carnian)

Where found: Santa Maria Formation, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

How much is known: A right femur (thigh bone), along with several vertebrae and a partial pelvis from the same site. It is unknown whether the other bones belonged to the same individual as the femur.

Notes: Gondwanax was a silesaurid, a group of probably quadrupedal Triassic reptiles that often had adaptations for herbivory (though there is evidence that they also ate insects). Until recently, silesaurids were generally considered to be close relatives of dinosaurs instead of dinosaurs themselves, and I previously excluded them from coverage on this blog. However, multiple recent analyses have suggested that they might in fact be true dinosaurs, specifically early members of Ornithischia ("bird-hipped" dinosaurs), so from here on out I will tentatively include them within this blog's purview. In fact, some of those studies have found that most "silesaurids" may not have formed a unique evolutionary group, but instead a series of lineages with some being more closely related to later ornithischians than others.

Regardless of whether it is a true dinosaur, Gondwanax is one of the oldest known dinosauromorphs (the group containing dinosaurs and their closest relatives). Compared to other dinosauromorphs of similar age, Gondwanax more closely resembles later dinosaurs in having three hip vertebrae (whereas dinosaurs ancestrally appear to have had only two). It is unusual among dinosauromorphs in having a very small fourth trochanter, a attachment point on the femur for muscles that pull the hindlimb backward.

(Schematic skeletal of Gondwanax paraisensis, with preserved bones in orange, from Müller, 2024)

Reference: Müller, R.T. 2024. A new "silesaurid" from the oldest dinosauromorph-bearing beds of South America provides insights into the early evolution of bird-line archosaurs. Gondwana Research advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2024.09.007

#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#Gondwanax#Middle Triassic#Late Triassic#South America#Ornithischia#2024#Extinct

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember/Spectober 2023 #11: A Large Spider

An anonymous submission requested a "spider the size of a coconut crab":

Ceratohispidus aspectus is a distant descendant of jumping spiders living on an Aotearoa-like landmass, isolated with no mammalian predators.

This particular lineage is notable for both their extreme gigantism (with their larger size and weight causing them to lose the ability to jump) and for having taken up herbivory in a similar manner to one modern species. Most of these big plant-eating spiders are around the size of wētāpunga, and occupy a similar ecological niche, but Ceratohispidus is the largest of them by far – rivalling the modern coconut crab with a body length of up to 40cm (~1'4") and a legspan of almost 1m (~3'3").

After reaching sexual maturity at 5-10 years old, adults grow very slowly, molting only once every year or two and taking several decades to actually get anywhere close to their maximum size.

Ceratohispidus' thick legs end in hoof-like claws, and it selectively browses on vegetation by snipping off pieces with its pincer-like palps. A gizzard-like structure in its digestive system helps to grind up fibrous plant material with small gastroliths, and its wide abdomen houses both large book lungs and a tracheal system with air sacs that can contract and expand to provide a small amount of active ventilation.

While the "horns" and spikes ornamenting its body may provide some defense from the few avian and reptilian predators in its habitat, they're mainly used as part of highly elaborate visual displays between individuals.

#spectember#spectober#spectember 2023#speculative evolution#arachnophobia tw#jumping spider#spider#arachnid#arthropod#invertebrate#art#science illustration#happy halloween#have a little hint of carcinization. as a treat

369 notes

·

View notes