#henry i of castile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Ferdinand III of Castile (1199/1201 – 1252), son of Alfonso IX of Leon and his wife Berenguela I of Castile

2) Alfonso IX of Leon (1171 – 1230), son of Ferdinand II of Leon and his wife Urraca of Portugal; with Berenguela I of Castile (1179/ 1180 – 1246), daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Eleanor of England

3) Blanche of Castile (1188 – 1252), daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Eleanor of England

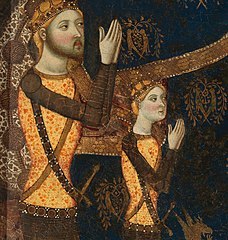

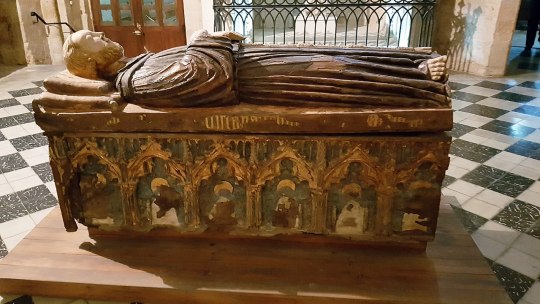

4) Henry I of Castile (1204– 6 June 1217), son of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Eleanor of England

5) Urraca of Castile (1186/ 1187 – 1220), daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Eleanor of England

6) Ferdinand of Leon (ca. 1192 – 1214), son of Alfonso IX of Leon and his wife Theresa of Portugal

7) Elisabeth of Swabia (1205 – 1235), daughter of Philip of Swabia and Irene Angelina

8) Alfonso X of Castile (1221 – 1284), son of Ferdinand III of Castile and his wife Elisabeth of Swabia

9) Philip of Castile (1231- 1274), son of Ferdinand III of Castile and his wife Elisabeth of Swabia

10) Eleanor of Castile (1241- 1290) daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and his wife Joan of Ponthieu: with Edward I of England ( 1239 – 1307), son of Henry III of England and his wife Eleanor of Provence

Note: The marriage of Alfonso IX's parents got also annulled/declared void due to consanguinity, but I didn't include him on the list because this example is already present in Ferdinand III & IV

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#canonjonsnow#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medival bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#ferdinand iii of castile#alfonso ix of leon#berenguela i of castile#blanche of castile#henry i of castile#ferdinand of leon#urraca of castile#alfonso x of castile#philip of castile#eleanor of castile#edward i of england

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the blossoms in my garden 🪴

An Angevin-Plantagenets family tree I made for my medieval art collection zine, “If All The World Were Mine!” The physical edition is now available, so check it out if you can :D

#the plantagenets#plantagenets#medieval#12th century#geoffrey of anjou#geoffrey plantagenet#Matilda of england#matilda lady of the english#henry ii of england#eleanor of aquitaine#henry the young king#matilda duchess of saxony#richard the lionheart#geoffrey duke of brittany#eleanor of castile#joanna of sicily#john lackland#john i of england#richard i of england#louis vii of france#philip ii of france#philip augustus#whew thats a lotta names#melusine#my art#family tree

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not all her contemporaries considered Joanna 'mad'. In 1505 a Venetian ambassador to Spain, Vincenzo Quirini, noted that Maximilian spent several weeks in the Netherlands 'mostly with the queen [Joanna], keeping her entertained almost constantly with fetes' and trying to reconcile her with her husband before they left for Spain. He 'has tried everything he can to make her happy, because he knows that all her problems have arisen because she is depressed.' In Quirini's opinion, Maximilian succeeded. Henry VII, who met Joanna a few weeks later when storms diverted her ship to England on her way to Spain, agreed: 'When I saw her,' he later told the Spanish ambassador, 'she seemed fine and she spoke in a restrained and gracious manner, never compromising her authority.' Moreover, 'although her husband [Philip] and those with him made her out to be mad, to me she seemed sane; and that is what I believe now.' Ferdinand too, apparently harboured some doubts. At their meeting one month after declaring Joanna incapable of governing, the king urged Philip to tolerate Joanna's behaviour 'just as he had tolerated the behaviour of Queen Isabella, her mother, who in her youth was driven by jealousy to far worse extremes than those of his daughter right now; and with his support she regained her senses and became the queen that everyone knew.'

Emperor: A New Life of Charles V, Geoffrey Parker

#take 1 of 'coa did not confront henry over his affairs bcus she had a dignified royal maternal example' ...#sincerely that seems like a narrative that just does not hold up under scrutiny#joanna of castile#geoffrey parker#i read a novel from her pov that included her visit to england#it took some liberties (mainly in the matter of an alternate love interest) but it remains one of my favorites#gaslight (1496)#also: ferdinand...you good?#'i fixed the problems that i created' damn; get this dude a medal.......tjaksfsdhfgiuoifj

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche II, Titular Queen of Navarre and Princess of Asturias

Contemporary paintings of Blanche II of Navarre (right) and her sister Leonor In doing some research in Spanish history, Blanche II, Queen of Navarre, appeared with her intriguing and sad life. Her story reminded me of another Iberian queen, a relative of Blanche’s, who came a bit later, creating one of those captivating historical connections. Family discord played a large role in Blanche’s…

#Blanche I#Blanche II#Ferdinand II#Gaston IV of Foix#Henry IV#John II#Juan II#Juana I#King of Aragon#King of Castile#Medieval History#Queen of Castile#Queen of Navarre#Spanish history

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know that Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York's wife Isabella is likely to have an affair with a man from the Howard family and gave birth to the Earl of Cambridge, Richard? Isabella's will was made with Edmund's consent, which may indicate that although Edmund did not want his property to go to Richard, he did not hate their mother and son. Perhaps they were just colleagues who had to have children together

I'm not quite sure I'm following your ask. I think you're asking about Isabel (or Isabella) of Castile, Duchess of York and the assertion that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was a son born from her adulterous liaison? However, the man she was accused of having an affair with was not a member of the Howard family but John Holland (or Holand), Earl of Huntington. Huntington was the son of Joan of Kent and Thomas Holland and thus half-brother to Richard II. Huntington was married to Elizabeth of Lancaster who was the sister of Henry IV, which would have been made things awkward (to say the least) when Richard II was deposed. Huntington was killed during the Epiphany Rising which aimed to restore Richard to the throne. .

Jenny Stratford recently published work arguing that the affair did not take place and that Cambridge was legitimate, as far as we can tell. I'll talk you through the evidence and her arguments against it below the cut.

Thomas Walsingham's commentary on Isabel

Thomas Walsingham wrote that Isabel was:

A lady of sensual and self-indulgent disposition, she had been worldly and lustful; yet in the end by the grace of Christ, she repented and was converted. By the command of the king she was buried at his manor of Langley with the friars, where, so it is said, the bodies of many traitors had been placed together.

Stratford points out that Walsingham got the date of her death wrong, placing it two years after her death occurred, which suggests he was probably not well-informed about his life. She suggests that the image of emerges from Isabel's will contrasts sharply against the image Walsingham provides:

The duchess herself emerges in a favourable light. In face of her husband’s debts, the arrangement to provide an income for the seven-year-old Richard by transferring to Richard II most of her jewels and plate, her personal chattels, was eminently practical. It limited the possibility of claims by the duke’s creditors, while grants previously made to Isabel were subsequently reassigned to fund the annuity. These provisions seem very unlikely to indicate that young Richard was illegitimate, any more than a gap of twelve years between the age of the oldest and youngest of the duchess’s three living children was necessarily significant. The duke’s will drawn up a decade after Isabel’s death speaks of his devotion to her.

It's also worth noting that Walsingham has something of a reputation for misogyny and for being unreliable - we now know that some of his assertions about Alice Perrers's background are groundless and serve to make her appear worse than she was, while Anna Duch argued that he effectively erased Anne of Bohemia from his account of Richard II's reign. He is also full of vitriol for Agnes Launcekrona and Katherine Swynford so it seems to me that we should treat his claims on women with great scepticism.

John Shirley's comments on Chaucer's Complaint of Mars

Forty years after Isabel's death, a scribe named John Shirley wrote an afterword on Geoffrey Chaucer's Complaint of Mars that linked it to a scandal involving "the lady of York" and John Holland. Connected with Walsingham's commentary, it's generally been taken as evidence that they had an affair.

Stratford argues that the Shirley's commentary is likely a garbled reference to the affair between Constance of York (Isabel's daughter) and Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent (John Holland's nephew) which the resulted in the birth of an illegitimate daughter, Eleanor. Following Kent's death, Eleanor claimed claimed her parents had married clandestinely before Kent married Lucia Visconti and that she was his rightful heir but her claims were rejected. Historians have suggested that Kent might have considering marrying Constance before the revelation that she had been involved in a plot against Henry IV meant he distanced himself from her.

Additionally, J. D. North argued that the astronomical framework contained within Complaint of Mars could have only applied to the year 1385 and aligns it with the beginning of the affair between Elizabeth of Lancaster and Huntington. Elizabeth had been married to John Hastings, heir to the earldom of Pembroke, in 1380 when she was 16 and Hastings was 8. However, the marriage was annulled in 1386 and Elizabeth soon after married Huntington on 24 June 1386. It is frequently asserted that Huntington and Elizabeth had embarked on an affair that resulted in a pregnancy, leading to the hasty annulment of Elizabeth's first marriage and her second marriage to Huntington though it isn't clear when their first child was born, though it was in 1386 or 1387. It may be that John Shirley's reference to the affair between "the lady of York" and Huntington may actually be referring to Huntington's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster.

It may even be that the reference represents a garbled combination of the two affairs - Constance of York and Edmund Holland, Elizabeth of Lancaster and John Holland - recorded decades later. It might be noteworthy in this regard that Elizabeth and Huntington's first child was also named Constance (both Constances were named after Isabel's sister, Constanza or Constance of Castile), which would add to the confusion).

The wills of Cambridge's father and older brother.

The argument that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was illegitimate is based around the lack of reference to Cambridge in the wills of his father and older brother, where it is assumed that this represents that Cambridge was effectively, though not legally, disowned.

His brother, Edward 2nd Duke of York's will was written after Cambridge had been executed as a traitor for his role in the Southampton Plot. His lack of reference to Cambridge may simply be because Cambridge was dead and could not be a beneficiary. There may have also been concern that any reference to Cambridge, such a request for prayers for his brother's soul, could result in suspicion of Edward's own loyalties. From the surviving evidence, Edward also seems to have had a close relationship with Henry V so Cambridge's treason may well have driven a wedge between the brothers. In short: there are a lot of reasons why Edward might have avoided referencing Cambridge explicitly that were far more relevant to the circumstances his will was written in.

Stratford notes that "a testator may not include all his bequests in his will", which would apply to both Dukes of York. Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York left "nothing in the will to any of his three children" (my emphasis). He did, however, ask to be buried "near his beloved Isabel, formerly his companion". In short, there is no reason to presume Cambridge's exclusion was due to his being informally disowned by his father due to the adultery of his mother. York's will provides no support to the idea that he had a fraught relationship with Isabel, either.

Isabel's will makes special provision for Richard, Earl of Cambridge.

Isabel's will asked Richard II for provide an annuity of 500 marks for Cambridge against the surrender of her jewels and plate until appropriate lands could be found to furnish him with an income. This has led to the belief that Cambridge would not be supported by his father and brother and, in combination with the above, that this was because he was illegitimate.

Most of this is based on the transcript of her will published in Testamenta vetusta, which is a shortened extract of the full document which didn't include Isabel's many bequests to her husband (if you read something that claims Isabel left York nothing, the author is working from the abridged will, not the full text). Stratford's study is on the original will in its full form. As noted in your ask, Isabel required and received the permission of her husband to make this will. Stratford also notes that some of those mentioned in the will are Edmund, Duke of York's officers who also appear in his will, "strongly suggesting that the duke and the leading members of his familia were in full agreement with its provisions". In short, the idea that York was refusing to acknowledge or provide for Cambridge seems somewhat illogical given his involvement and the involvement of his officers in Isabel's will which was primarily concerned with providing for Cambridge.

Stratford argues that what the will represents is an effort by Isabel and York to provide for Cambridge "while protecting as far as possible the incomes of her husband and his heir."

The principal purpose of Isabel’s will was to provide for their youngest child, Richard, then aged seven. Edmund gave his wife full powers to dispose of her horses, jewels, robes, the furnishings of her chamber, and her other chattels. She made a number of bequests, notably including books, but offered the majority of her valuables to Richard II if he would agree to provide her younger son, his godson (filiol), with an income of 500 marks per year for life. If the king did not so wish, Isabel’s oldest son, then earl of Rutland, was invited to do so on the same terms.

At the time Isabel was drawing up her will, York was heavily in debt following his Portuguese expedition, had difficulty obtaining money due to him from the Crown, and didn't have lands commensurate with his status. York's executors were still struggling to pay his debts eight years after his death and when his eldest son died in 1415, the duchy of York remained bankrupt for twenty years. Stratford notes that the money raised by Isabel's jewels and plate would "circumvent claims on the duke by his creditors".

John Holland gave Isabel a gift.

Isabel's will mentions a "sapphire and diamond brooch" given to her by John Holland, Earl of Huntington which has been taken as evidence of their affair. Sometimes she is also said to have been given a gold cup and a chaplet of white flowers by Huntington, though Stratford points out the brooch is the only item actually said to have been given to her by Huntington and is one of three gifts from named donors (the others was a "little" gold tablet given to her by John of Gaunt and a gaming board of jasper from Leo of Armenia).

Firstly, while gifts of jewels to us seem to be strictly or largely romantic gestures, this very much wasn't the case within the Middle Ages, where the exchange of jewels was a normal part of aristocratic life, albeit serving an important function. We know that medieval nobles frequently exchanged gifts, including items they had been given by others, and it is a pure speculation to assume that Isabel "treasured" the brooch or even that she kept it because it was Huntington who had given to her. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that it was identified through the designation as a gift given to her by Huntington.

Secondly, if this is evidence of their affair which produced Cambridge, it's very odd that she didn't leave Huntington's gift to Cambridge but to her eldest son, Edward, who was York's acknowledged son and heir whose legitimacy has never been doubted.

Isabel left bequests to Holland.

Isabel left her Bibles and "the best fillet I have" to John Holland. Some have argued that this is unusual enough because Holland was the only person she gave gifts to who wasn't a "close member" of her family.

Outside of her husband and three children, Isabel also left bequests to Richard II, Anne of Bohemia, John of Gaunt and Eleanor de Bohun, Duchess of Gloucester, and Stratford groups with Eleanor as a member of Isabel's "wider family" and says it is credible they were friends, not lovers. The extent that Holland isn't a "close" member of her family can be debated: he was married to her niece (Elizabeth of Lancaster) and the half-brother of her nephew (Richard II).

Stratford says that Isabel may have made the bequest to Huntington in hope that that he would influence Richard II and John of Gaunt (who was Huntington's father-in-law and and close ally in the 1380s and named as an executor in Isabel's will) to ensure that the annuity she sought for Cambridge would become a reality.

Furthermore, Stratford suggests that the "best fillet" (which was probably a collar) may have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, Huntington's wife. If so, this would rather point away from it being a memento from their affair.

There were a ten-year gap between Cambridge and his siblings.

The other main piece of evidence put forward is the large gap between Constance of York (b. c. 1375) and Cambridge (b. c. 1385). The supposition usually goes that having had two children (Edward, 2nd Duke of York was born c. 1373), Isabel and York had grown tired of each other's company and didn't have sex again, Isabel then embarked on an affair with Huntington that, some ten years after Constance's birth, left her pregnant and York allowed the child to be brought up as his son but refused to provide for him.

The problem with this scenario is that it is effectively a complete invention. The idea that York and Isabel were at odds is based around the idea of the affair and the speculation Cambridge was illegitimate. York never repudiated Isabel nor officially disowned Cambridge as a bastard. There are many possible reasons why there was such a large gap - fertility issues, miscarriages, bad luck, personal decisions, religious reasons (i.e. choosing to adopt a chaste marriage). Constance's birth may have been particularly difficult and York and Isabel decided not to chance sexual intercourse or to use the contraceptive methods available to them only to slip up. It's also possible that they may had other children who died too young to leave evidence behind and that the large gap between children wasn't that large in reality. After all, it seems we know very little about the births of their children, even the years are uncertain.

I know this is all speculative but so is the argument that they fell out. The point is that we don't have evidence to explain why beyond speculation.

Conclusion

A lot of the arguments for the affair based on tenuous links and are often based on the assumption that the affair was a historical fact and that Walsingham's comments on Isabel are an objective and reasonable account of her character. So the evidence that shows us a connection between Isabel and Huntington is often assumed to be evidence of a sexual relationship.

Take the brooch. It seems to be read as the equivalent of a man buying his lover an emerald necklace or diamond earrings. Except we know that the exchange of valuable jewels as gifts was a common aspect of medieval noble life that performed a vital function that very frequently had nothing to do with romantic or sexual feelings. We know, for example, that Henry VI gave Eleanor Cobham a brooch - it does not follow that they were therefore having an affair or that Henry harboured romantic feelings for his aunt.

That the brooch was mentioned in Isabel's will also tells us nothing. We don't know how she felt about it, only that she singled it out to be passed onto her eldest son (not Cambridge). It may be that she wanted him to have it because of he had admired it and, if it was a feminine piece, may have intended to give it onto his wife when he married. It's quite unremarkable that a medieval individual would identify a piece through noting who had given it to them and is not proof of romantic attachment. Isabel also mentioned gifts given to her by John of Gaunt and Leo of Armenia - should we assume she had affairs with them too?

On a similar note: that Isabel left items to Huntington is taken as proof of their romantic liaison. The bequest? Her best fillet (probably a collar, according to Stratford), which may well have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, and her Bibles. They were likely valuable items but hardly proof of romantic involvement - such bequests were very common and would be utterly remarkable without the context of Shirley's commentary on their relationship.

It seems to me that there is good good reason to believe that John Shirley's commentary on Complaint of Mars, written decades after Isabel's death, may not have been about Isabel at all. She isn't named in the commentary and we have no clear, explicit evidence of this affair outside of the commentary itself. I think it was a garbled recollection of either Isabel's daughter, Constance of York's affair with Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent or of John Holland's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster. We have clear, contemporary evidence of both these affairs - the existence of Constance's and Kent's daughter and this daughter's attempt to inherit Kent's estates, the annulment of Elizabeth's marriage to Hastings and her marriage to Huntington.

The evidence cited as "proof" of their affair is really nothing of the sort. Isabel's will attempted to provide for Cambridge in the face of York's (comparatively) small income and large debts. Huntington was a beneficiary but hardly the only one and not a particularly unusual choice. He gave Isabel a gift that was in keeping with the social custom of their class and time. York's will mentioned none of his children and he did not officially disown Cambridge. The lack of reference to Cambridge in his brother's will is easy to understand given it was written after Cambridge had been executed for treason. We have no real evidence of discontent between Isabel and York - he was obviously involved in the writing of her will and he requested burial with her in his own. Nor is there any account that records discord between them or separation, like we do for John of Gaunt and Constanza of Castile. York was buried with Isabel, as he had requested, and on their joint tomb-monument are Huntington's coat of arms (amongst many others). It seems very strange to me that York was so utterly furious about Isabel's adultery that he refused to provide for Cambridge, forcing Isabel to beg the king to provide for him, yet he chose to be buried with her, he chose as his second bride Huntington's niece, Joan Holland, and he chose to add the coat-of-arms with the man she had betrayed him with on their tomb monument (which was probably constructed sometime between 1393 and 1399). I don't think this picture holds up.

Walsingham did criticise Isabel for being "worldly and lustful" but Walsingham calling a woman a slut is pretty par for the course for him and he got facts of her life wrong. Nor does he report anything she actually did to deserve such a reputation. In others: scepticism is clearly needed. None of this adds up to very much. It isn't until Shirley wrote his commentary, decades later, that we find any reference to their affair. The rest are things that would be entirely unremarkable without Shirley's commentary directing us to see it as a romantic gesture.

Of course, the fact is that we can't prove she didn't have an affair and that Shirley was really referring to a more evidenced scandal. Proving a negative is hard. Even if we located, exhumed and DNA-tested the bodies of Cambridge, York and Huntington, we might confirm that Cambridge was really York's son (or Huntington's or the son of an unknown man) but we wouldn't be able to prove that Isabel didn't have sex with Huntington at some point in her life. We don't have evidence for every single time a medieval individual had sex and so we can't definitively rule out the possibility that an affair did occur. All we can say is the actual surviving evidence doesn't support the narrative that Isabel had an affair.

It's probably worth noting that Kathryn Warner also read Isabel's full will and still accepts the narrative of Isabel's infidelity, though she argues Cambridge should be given the benefit of the doubt where his illegitimacy is concerned. Personally, I find Stratford's reading of the will more credible than Warner's. I don't think the evidence cited as proof of Shirley's claim is actually evidence of an affair but the existence of a typical relationship between medieval nobles working as normal. Warner seems to contradict herself at times* and she doesn't seem to have been interested in questioning whether Isabel did or did not have an affair. I also think Stratford's extensive work on medieval manuscripts and the inventories of John, Duke of Bedford and Richard II lends credence to her claims.

Works Referenced

Jenny Stratford, "The Bequests of Isabel of Castile, 1st Duchess of York, and Chaucer’s ‘Complaint of Mars’", Creativity, Contradictions and Commemoration in the Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of Nigel Saul, eds. Jessica A. Lutkin and J. S. Hamilton (The Boydell Press 2022)

Jenny Stratford, "Isabel [Isabella] of Castile, duchess of Yorkunlocked (1355–1392)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (published 2022, updated 2023)

J. D. North, Chaucer's Universe (Oxford University Press 1988)

James P. Toomey (ed.), "A Household Account of Edward, Duke of York at Hanley Castle, 1409-10", Noble Household Management and Spiritual Discipline in Fifteenth-Century Worcestershire (Worcestershire Historical Society 2013).

John Evans, "XIV. Edmund of Langley and his Tomb", Archaeologia, vol. 46, no. 2, 1881

Kathryn Warner, John of Gaunt: Son of One King, Father of Another (Amberley 2022)

(also looked at the ODNB entries for York, Cambridge, Huntington and Elizabeth of Lancaster).

* After mentioning the brooch given to Isabel by Huntington, Warner states: "Isabel did not not mention other gifts she had received from anyone else". In an earlier chapter, Warner says "The 1392 will of Isabel of Castile, duchess of York and countess of Cambridge, reveals that Levon [Leo of Armenia] gave her a ‘tablet of jasper’ during this visit, which she bequeathed to John of Gaunt". Warner also repeats this within the chapter dealing with Isabel's will: "and ‘a tablet of jasper which the king of Armonie [King Levon of Armenia] gave me’ to John of Gaunt". How can Huntington's brooch be the only gift from anyone mentioned in her will when we've been told (twice) that Isabel's will includes a reference to a tablet of jasper gifted to her by Leo of Armenia? Additionally, Warner's arguments seems to be drawn from the preconceived notion that Isabel did have an affair so any evidence connecting her to Huntington must be evidence of the affair, regardless of how limited the evidence is - this is quite surprising, since it goes against one of her arguments against reading Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer's relationship as a love affair.

#ask#anon#isabel of castile duchess of york#john holland earl of huntington#edmund duke of york#richard earl of cambridge#i did just have the revelation cambridge was only a year and a bit older than henry v#god this is long

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

guys im becoming so obsessed with knights and knighthood…….

#i just spent like 20min spitting tudor era facts at kara#and ranking henry viiis wives from favorite to least favorite#and then we started yelling about isabella and ferdinand and i nearly explode#RRRRAAAAAA ISABELLA OF CASTILLE…..!!!!!!#AND NOW I NEED TO LEARN EVERYTHING THERE IS ABOUT KNIGHTHOOD…..#kara sent me some recs mwah <3#if anyone has litterature recs or like podcasts or genuinely whatever i would be Most Thankful .#my tudor era hyperfixation lasted for months and this feels so similar ………..

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history we learn in school has often written out the women that helped shape it, or perhaps simply influenced its players. @MadamHerStory seeks to shed light on their lives and breathe life into their stories. These women might have played either pivotal or simple roles but their lives were no less important than their male counterparts and contemporaries.

It’s true that we can’t do Henry VIII’s story justice without telling that of his better halves, just as there can be no end to the Hundred Years War without Joan of Arc and the French King’s formidable mother-in-law, no papal preeminence over the Holy Roman Empire without the Countess who defeated the imperial army and had its Emperor on bended knee, Christopher Columbus might never have “discovered” the ‘New World’ without the support of the Queen of Spain, and the Mongol Empire wasn’t likely to have reached such heights without the trust Genghis Khan had in his daughters. And on and on it goes.

These women were pivotal to the eras in which they lived but there were also those that may not have played on the world stage but deserve their time in the limelight nonetheless. Women relegated to the background who still found ways to pull (or at lest tug on) the invisible threads of influence, like the Italian princess known as “The First Lady of the Renaissance“ and the royal mistress who reigned as “the Lady of the Sun”. Their stories merit recounting, not just for the marks they left on history but to share anecdotes of the colourful lives they led. The laughs and the cries, the comedies and the tragedies, the real and the rumoured.

But I’m not the only one with this goal in mind, far from it, and I hope to later make a post on all the great historians and history nerds that sparked my love of history (or, really, HERstory) through their own portrayals of theses historical women and their wondrous tales. But this particular post is just to serve as an introduction to what I seek to share with you: my love for the great women of distant times, how they found power in a world that sought to deprive them of it (sound familiar?), and how they influenced the world in which they lived (whether it be slightly or majorly, positively or negatively).

If you wish to join me on this voyage to the past, hop on board but, if not, then I hope you safe travels on your journey, may your star guide you on the adventure of your dreams. For me personally? That’s in a land before skyscrapers and penicillin (and me, unfortunately).

The painting is The Virgin and Child with Saints Barbara, Catherine, Cecilia and Ursula by an anonymous as artist (active between 1475 and 1505) known as the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend (more on that: wikipedia, Everyone’s Museum, Museo Nacional del Prado [EN], Sarah Riskind on Saint Donatian Mass, Painting Before 1800, and an abstract of Ann Roberts’ 1982 critical essay). “Ann Roberts identified this painter as Jan de Hervy, who died before 1512.”

The HerStory Encyclopaedia

• Women on the World Stage

– The Ladies’ Peace (featuring Margaret of Austria and Louise of Savoy)

• Portraits and Profiles

– Margaret of Austria (in progress)

#women’s history month#women in history#european history#english history#henry viii#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#queen of england#royal mistress#the hundred years war#french history#joan of arc#yolande of aragon#holy roman empire#pope#matilda of tuscany#spanish history#isabella i of castile#queen of spain#asian history#genghis khan#italian history#italian renaissance#renaissance#isabella d’este#alice perrers#medieval history#medieval women#history blog#madam herstory

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did henry vii had a tensed relationship with the trastamara couple from the very beginning ?

No, I don’t think so. Well, he wanted a really big dowry, but they were willing to pay at first.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested. Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pretty in Pink

Ambessa Medarda x Reader

Part One of: Pretty in Pink

Synopsis: Your father’s kingdom had been at war with Noxus for no more than a month or two—and yet his people were already suffering. With the loss of countless soldiers and citizens, he decided to form a peace treaty with the formidable warlord—Ambessa Medarda. In exchange for peace between the two nations, he would give up his one and only daughter. You.

cw; afab!reader; angst; mentions of death, war, and possible rape; alcohol consumption; not proofread; you’re being given away; men and minors dni

Special thanks to @hell0-ki55y for the prompt. Hope you enjoy 🎀

Taglist: @fruitfulfashion

…….

Blood. Death. Sorrow. Poverty.

That’s all you’d been hearing about for the past month or so. The war between Noxus put a major dent in your father’s kingdom, and now we were on the brink of a depression. It drained us of soldiers, riches, and innocent citizens— who didn’t even know there was a war until the warriors were knocking on their front door.

Your kingdom was fairly small. There was just a few hundred citizens and a small army to protect yourselves with. You all didn’t bother anyone. Didn’t engage in conflicts overseas. Barely even traded with nearby kingdoms. The few allies you did have were strained and undocumented.

It was the perfect target for Noxus.

They didn’t waste much time taking action. They sent a flurry of soldiers by surprise, and with the pressure from his council—your father was forced to declare war. Big mistake.

You were now kept coddled up in your room with a ridiculous amount of guards stationed outside your door. Your late night escapades into town were no more as you longingly gazed out the window for hours on end.

Sometimes your ladies in waiting—Amara, Evelyn, and Felicity—would visit you for tea. The once bubbly conversations about relationships and the latest fashion were no more. Now all you ever discussed was the war. There was never any good news.

The three of them had been sent from nearby kingdoms even smaller than yours when you were much younger. Ever since then, you’d been attached at the hip. You practically shared everything with them—and vice versa.

You smiled at the thought of your friends. They’d been one of the few joys you had ever since your mother died.

You were snapped from your thoughts at your chambers doors were open. One of your guards—Henry—greeted you, but you could tell his usual hard facade was shaken.

“You are requested in the throne room, Princess.”

You looked at him in confusion. “The throne room? Me? Why?”.

He kept his frigid body still, “I will escort you down, Princess.”

You cautiously rose from your seat and approached the guard with hesitant steps. Before you would fully step out of the room, he spoke in a faint voice, “I know this is not my place, but I suggest you bring a small bag of belongings with you. Anything that you’ll want to keep.”

Your confusion turned into slight anger, but you didn’t question his word. He had been loyal to you since the day you were born and crowned princess. You looked down to find him holding a small brown satchel. You took it from his shaky hands.

“Hurry, princess. She won’t wait long.”

You continued to pack the few things you could—wondering who exactly she was.

……

The two of you finally made it to the throne room with haste. However, as you walked—well, jogged—the castle was….eerily silent. The usual hustle and bustle of the court was no where to be seen. Servants that once greeted you as you passed now looked down at their feet at they practically ran past you.

Something was wrong. And everyone knew expect you. You had a feeling that wouldn’t last long, though.

The two of you finally entered the court room, and one of the guards announced your entrance. “Princess Y/N Y/LN. Princess of Castile and daughter of King Arthur.”

As soon as you entered, you could feel the tense energy throughout your being. You noticed the council standing off to the left of the throne with indifferent gazes towards you. Your father sat perched on his throne with a grim expression as he slumped in his seat. His right leg was shaking—a clear sign of his nervousness.

What surprised you the most, however, was what stood to the right of the throne.

There stood a tall, burly woman. She was adorned in crimson, gold, and silver armor as her sword sat on her waist. Her free grey coils complemented her rich brown skin—which was heavy with scars. Her physique rivaled even your father’s as sun stood at an impressive height. There was a handful of guards accompanying her—all wearing the symbol of Noxus. Your nervousness grew tenfold.

The silence in the room did nothing to lessen the tension as everyone turned to look at you. You shrunk under their gazes—all possessing mixed emotions.

The scarred woman was the first to speak, “It’s about time you came down, princess. I thought we would be waiting here all day.”

Your father visibly tensed at her taunt, but ultimately said nothing.

“Perhaps your father could tell us why you’re here.”

His jaw clenched as looked down at his feet. He hesitantly straightened up in his seat as he took a shaky breath. Fear was evident in his voice as he spoke, “For the past month or so, Castile has been at war with Noxus. It has cost us the lives of many, and our supplies have lowered to practically none. As a result of this, the council and I have come to the conclusion to stand down to protect our people and resources. In exchange for peace between us…”

His breath hitched as he paused. He looked up at the woman, then you, “I will give my daughter, Princess Y/N, to General Ambessa Medarda.”

Your heart dropped at his words, and you nearly fell to your knees. The councilmen shook their head as they continued to look at you in pity. Your father merely avoided your gaze as his fists clenched. Tears clouded your vision as your nails dug into your palms.

The woman, who you now knew as Ambessa, waves toward her guards, “Escort her to the ship. Be gentle with her, will you?”

You froze up as her guards strode towards you. The cold steel that covered their hands met your arms and they started to pull you towards the door. Almost as if a light switched in you, you started to kick and scream, trying to get the guards off you. You struggled in their hold, and they hesitantly looked towards Ambessa—seemingly asking for help.

You continued to struggle as they tightened their grip, and your father winced at your cries. You turned towards your sworn protecter, “Henry, help me! Get them off of me! Listen to me!”

He simply continued to stare straight forward, ignoring your pleas. He closed his eyes as he turned away and his stoic expression faltered.

The guards lifted you up as they carried you out the throne room—yet you struggled even harder. You caught a glimpse of Ambessa, who looked seemingly amused at the whole exchange.

The sound of your struggles faded into the distance. Your father, the councilmen, and Ambessa were now left alone in the throne room.

Ambessa turned to your father in one, smooth motion, “Don’t worry too much, I’ll take very good care of her.”

And with that, she turned on her heel and follows you out the throne room.

……..

You looked longingly out the small window into the vast ocean. The ship was bigger than any one you had ever seen. Though, you didn’t get much time to admire it as the guards thrusted you onto it and locked you in a small room.

You had been on water for days, and you knew you didn’t have long before you arrived in Noxus. The pink dress you wore made you look pretty—yet you felt anything but.

There was a small bed with white linens and wooden furniture attached to the ground so it wouldn’t move. You didn’t mind it though. How could you?

Tears welled up in your eyes as you clutched your small brown satchel tighter. You cried for what had seemed like the hundredth time that day.

Everything you had ever known—gone at the snap of a woman’s fingers. You couldn’t think of a worse situation than now. A princess who once had a life of tranquility and peace—was now being shipped off to the enemy in exchange for the lives of your people.

The fear of the unknown weight heavy in your mind. This woman��Ambessa—could do anything with you. She could make you a servant in her estate—condemned to scrubbing stains out and mopping floors for the rest of your life. She could make you work in the fields—bending over until your back ached as you cooked alive in the relentless heat and picked crops from the ground. She could make you a pleasure woman for her soldiers—giving you to them when they were done with their duties, waving absently as she said ‘Have a go at her’.

The prospect of being a servant didn’t seem so bad compared to the other ones—especially the last one.

You were pulled from your thoughts as you heard the lock on your door being undone. You jumped from your seat and backed away from the door—knowing none of the servants should be here at this time.

You stayed as silent as a mouse—as if whoever was outside didn’t already know you were in there.

Your breath hitched as the door creaked open. In walked in your ladies in waiting—Amara, Emily, and Felicity.

The initial surprise you felt was forgotten as relief crossed your features. The ladies ran over to you as they gave you a big hug. It brought you warmth and joy like no other.

While you were happy, you couldn’t help but ask, “What are you doing here?”

Amara was the first to speak up, “We were escorted onto the ship by soldiers. They told us we were to accompany you to Noxus. We didn’t even hesitate.”

Felicity spoke, “They didn’t even give us time to pack. They said ‘everything we needed would be in Noxus.’”

Emily held up your bag, “This is all they let you take?”

You shrugged, “Henry told me I might want to pack a small bag of things I wanted to keep before I was taken to the throne room. It’s all I have left.”

Emily shook her head. “Oh, Henry….”.

You sighed at the mention of the man who was once your sworn protector. He’d probably be dead the next time you see him, given his old age. Before you could dwell on the thought long enough to cry, Amara started to pull something from behind her back.

You motioned towards it in curiosity, “What’s that?”

Amara smiled mischievously, “It’s liquor. Noxian liquor. We snagged it from the top deck, went right under their noses.”

You stared at the bottle in disbelief as you studied it, “Liquor?! What if we get caught with it? We’re dead women walking.”

Felicity shrugged as she pulled out her own bottle, and Emily followed soon after. “They’ll never notice. They had enough bottles to get an army drunk.”

Your disbelief grew tenfold as you stared at the women. They stole not one—but three bottle of Noxian liquor.

You couldn’t wrap your head around why they would possibly do that. “Why’d you get this? I mean…I’m not turning it down but, this doesn’t seem like the best time to get drunk off of your ass.”

Felicity looked at you as she held her bottle. “Y/N, we’re celebrating. After we get off this ship, our lives will change—if it already hasn’t. We don’t now for sure what’s gonna happen. This could be our last night together, and I’d be damned if I spent it without you all by my side.”

Tears welled up in your eyes as the reality of the situation came to you. She was right. How could you know if you were going to see each other again? You couldn’t. The thought of you losing your sisters—all you really had left—was too much to bear. The ladies share your tears as the revelation was made. Soft sniffles filled the room as they leaned on each other.

You grabbed the chilled bottle from Felicity’s hands as you spoke. “You’re right. Things will change when we get off this ship. But I have known you ladies for as long as I can remember, and I’d be damned if some Noxian scum tried to tear us apart.”

The ladies were visibly surprised at the determination in your voice as they looked up at you. You popped open the liquor and help up the bottle.

“A toast, to us. We are sisters, and nothing will change that.”

Emily and Amara held up their own bottles, while Felicity simply held up a fist to the sky. “Cheers!”

You held back your head and opened your mouth as you took a generous shot. The burning sensation punched you in the back of the throat—but the feeling was quickly replaced by warmth and relaxation.

The bottle was passed around and finished quickly, and the three of you sat in a comfortable silence—enjoying each other’s presence while already feeling tipsy.

You leaned on Emily’s shoulder as you silently prayed. For your sisters. For your people. For your father. For yourself. And for the Noxian woman to have mercy on you. Lots of it.

The sound of a second bottle being opened broke the silence, and you hoped your prayers would be answered.

Little did you know—they would be.

…….

Part 2 on the way…..

Reply for Taglist 🎀

492 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Henry II of Castile ( 1334 – 1379), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán; and his son with Juana Manuel de Villena, John I of Castile (1358 – 1390)

2) His wife, Juana Manuel de Villena (1339 – 1381), daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena and his wife Blanca de la Cerda y Lara; with their daughter, Eleanor of Castile (1363 – 1415/1416)

3) His father, Alfonso XI of Castile (1311 – 1350), son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal

4) His mother, Leonor de Guzmán y Ponce de León (1310–1351), daughter of Pedro Núñez de Guzmán and his wife Beatriz Ponce de León

5) His brother, Tello Alfonso of Castile (1337–1370), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

6) His brother, Sancho Alfonso of Castile (1343–1375), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

7) Daughters in law:

I. Eleonor of Aragon (20 February 1358 – 13 August 1382), daughter of Peter IV of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Sicily; John I of Castile's first wife

II. Beatrice of Portugal (1373 – c. 1420) daughter of Ferdinand I of Portugal and his wife Leonor Teles de Meneses; John I of Castile's second wife

Son in law:

III. Charles III of Navarre (1361 –1425), son of Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois; Eleanor of Castile's huband

8) His brother, Peter I of Castile (1334 – 1369), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Mary of Portugal

9) His niece, Isabella of Castile (1355 – 1392), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

10) His niece, Constance of Castile (1354 – 1394), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#henry ii of castile#john i of castile#juana manuel de villena#eleanor of castile#alfonso xi of castile#leonor de guzmán#tello alfonso of castile#sancho alfonso of castile#peter i of castile#constance of castile#isabella of castile#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#eleanor of aragon#beatrice of portugal#charles iii of navarre#canonjonsnow

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The attraction of Eleanor of Aquitaine to post-medieval historians, novelists and artists is obvious. Heiress in her own right to Aquitaine, one of the wealthiest fiefs in Europe, she became in turn queen of France by marriage to Louis VII (1137–52) and of England by marriage to Henry II (1154–89). She was the mother of two of England’s most celebrated (or notorious) kings, Richard I and John, and played an important role in the politics of both their reigns. She was a powerful woman in an age assumed (not entirely correctly) to be dominated by men. She was associated with some of the great events and movements of her age: the crusades (she participated in the Second Crusade, and organized the ransom payments to free Richard I from the imprisonment that he suffered returning from the Third); the development of vernacular literature and the idea of courtly love (as granddaughter of the ‘first troubadour’ William IX of Aquitaine, she was also a patron of some of the earliest Arthurian literature in French, and featured in one of the foundational works on courtly love); and the Plantagenet–Capetian conflict that foreshadowed centuries of struggle between England and France (her divorce from Louis VII and marriage to Henry II took Aquitaine out of the Capetian orbit, and created the ‘Angevin Empire’). She enjoyed a long life (she was about eighty years old at the time of her death in 1204) and produced nine children who lived to adulthood. The marriages of her off spring linked her (and the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties) to the royal houses of Castile, Sicily and Navarre, and to the great noble lines of Brittany and Blois-Champagne in France and the Welfs in Germany. A sense of both the geographical and temporal extent of Eleanor’s world can be appreciated when we consider an example from the crusades. Eleanor accompanied her husband Louis VII on the Second Crusade in 1147–9; when Louis IX went on crusade over a hundred years later, he left France in the care of Blanche of Castile, a Spanish princess and Eleanor’s granddaughter, whose marriage to Louis’s father had been arranged by Eleanor. Just this single example shows her direct influence spanning a century, two crusades and three kingdoms.

— Michael R. Evans, Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine

#slay#eleanor of aquitaine#historicwomendaily#english history#french history#12th century#women in history#richard I#king John#Henry II#angevins#my post

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

why it is a dumb argument by the greens to say the velaryan boys cannot inherit even in the time period

jace , luce , and joff were rumoured bastard they were not proclaimed as bastards or were first proclaimed illigitamate and later legitimized ,now lets take some historical example for example john of gaunt 1st duke of lancaster and his third wife Katherine swynford who was his mistress during his second marriage with Constance of castile , they had four children together who were proclaimed illigitamate since they were born before the couple was married when john married his third wife Katherine the Beaufords were legitamized by John of gaunt with the help of pope Boniface IX in september 1396 , who issued a bull recognizing and declaring them " wholly legitamate by doing this the Beaufords were allowed to have noble tittles and lands , but they were not allowed to have a claim to the English throne by their half brother king Henry iv of lancaster . By the above example the Beauford children were first recognised as illigitamate and later legitamized while jace , luce , and joff were never even proclaimed as bastard they were known as Leanor son , if we take bastard romours as an example king Edward iv of york was romoured to be a bastard and not the son of Richard of york which was spread by his brother George , duke of clarence who wanted to overthrow him and spread this roumour to weaken his claim to the throne , heck even queen Elizabeth i of England was also roumoured to be a bastard and not the daughter of king Henry viii which was also spread by Henry viii to furthur ruin Anne boleyn reputation , by the above these monarchs were also rumoured bastards but were not proven to be true it is the same case for the velaryon boys they were roumered bastards but their bastardry was not proven . and I with all my heart believe this were roumours spread were by green maesters to ruin Rhaenyra reputation , for example Lucrezia borgia who was the illigitamate daughter of pope Alexander vi and Vannozza dei cattanei and known to be the most beautiful woman of italy at that time who was a renaissance duchess , a patron of the arts , and a skilled administrater , to ruin her reputation the enemy of the pope started to spread vile roumers about her like her sharing a bed with her father and brother , her poisoning people and having a bastard before marriage just like Lucrezia, Rhaenyra's enemies the greens spread these roumours to attack her . so the argument that '' the velaryon boys cannot inherit '' by the greens is completely wrong

#a song of ice and fire#house of the dragon#anti team green#anti alicent hightower#anti aegon ii targaryen#anti aemond targaryen#anti otto hightower#anti criston cole#anti team green stans#pro jacaerys velaryon#pro team black#pro rhaenyra targaryen#pro lucerys velaryon#pro joffery velaryon#hotd#house targaryen#rhaenyra targaryen#queen rhaenyra#lucerys velaryon#jacaerys velaryon#joffrey velaryon

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margaret of Austria is Shipwrecked and King Henry VII of England Writes to Her at Southampton – 1497

Probably by Pieter van Coninxloo Diptych: Philip the Handsome and Margaret of Austria about 1493-5 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/GROUP20 When King Charles VIII of France put into motion his plans to extend his power basis into Italy, he attacked Naples which belonged to the sphere of influence of King Ferdinand of Aragon. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I concluded an anti-French…

View On WordPress

#Burgundian history#Charles V#Duke of Burgundy#Ferdinand#Henry VII#Holy Roman Emperor#Isabella#Juan Prince of Asturias#Juana of Castile#King of Aragon#King of England#Margaret of Austria#Maximilian I#medieval history#Philip the Handsome#Queen of Castile#Spanish history#Women’s history

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)

Son of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (b. 21 Apr 1926)

First pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE FORTUNE OF THREE

Angelina of Greece

Angelina was a slave in the harem of Sultan Bayezid I who would be recaptured by the Timurids to be later sent to the King of Castile as a “gift”.

It is speculated that she was born around 1380 as she was described as still being young in 1402, however, no exact date is proven to be correct.

Early Life

Nothing is known about the early life of this lady. However, she was likely of Greek origin, given that in Castille, she was referred to as “Angelina de Grecia,” and most historians agree that she was of Greek origin.

Some historians propose that she was the daughter of John V Paleologus and married Bayezid in 1372. However, since she is not mentioned in any Byzantine documents of that time and was sent to Spain where she remained permanently without any connection to the Royal Byzantine family, it is highly unlikely that she is the daughter of John.

Other accounts, and Angelina herself (through her tomb), claim that she is the daughter of a certain Count John/Ivan of Hungary, Duke of Slavonia/Dalmatia, the alleged illegitimate son of an unnamed King of Hungary. However, the lack of information about Count John/Ivan, if he ever existed, suggests that this might have been a plot created by the King of Castille to find noblemen for her to marry, a plot in which Angelina herself participated.

There was no Count/Duke of Slavonia by that name at the time that one can find information on. He was likely invented for higher chances of matchmaking purposes, as likely, Angelina was of humble origin before becoming a slave, and nobility typically preferred to marry within their own class.

First Capture

Some speculate that she was captured in the aftermath of the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, in case it is true she would have been around 16 years old. This speculation is linked to the belief that she was Hungarian, though it is more probable that she was not.

Other sources believe she was captured around 1391 in Thessalonica. In that case, she would have been around 11 years old, slightly older than the preferred age for girls to be educated as potential concubines but not uncommon.

Life In The Harem

Despite being sold as a slave in the imperial palace of Sultan Bayezid I, Angelina seems to have been one of the few Christian slaves in the palace. Timur later sent her as a “gift” to Henry III of Castille, and as we know Muslim women are not permitted to engage with men of other faiths.

Another indication of her faith is found in a past edition of Clavijo’s work.

“Argote de Molina (the editor of Clavijo) in the Discurso, which he prefixed to the Edition Princeps of 1582, states that with the presents of jewels, Timur sent to King Henry two Christian maidens.” - Embassy to Tamerlane/ 1403-1406 (Broadway Travellers) Volume 24, pg 178. (Angelina was one of the mentioned maidens.)

Considering her religion, it is safe to assume she was never considered a potential concubine for Bayezid, as all concubines of the Sultan had to be Muslims. She was more likely working as a servant under a higher-ranking slave or one of Bayezid’s Christian wives (Macedonian Princess, Byzantine princess, or Olivera Lazarevic).

Despina Hatun (Olivera Lazarevic) was captured alongside her daughters and Christian servants.

“When he was in Kütahya, Timur sent for Olivera Despina, her daughters, and her household, alongside the daughter of the ruler of Karaman [Jalayirid Sultanate], whom Beyazid was planning to marry off to his son Mustafa. They were brought to his camp with many servants, musicians, and dancers. He suggested that the Princess and other members of her household, who were still Christian, should embrace Islam. Despite her daughters being Muslim, Olivera declined this offer.” - Buxton, Anna. The European Sultanas of the Ottoman Empire - color edition. Kindle Edition.

If she was one of Olivera’s Christian servants, that would explain why she remained a Christian despite serving in the Imperial palace. Christian wives of early Ottoman Sultans are speculated to have freed slaves or, at the very least prevented forced Islamization.

Second Capture

In the aftermath of the Battle of Ankara in 1402, Timur sent his soldiers to plunder Bursa, resulting in the capture of the imperial treasure and slaves. It is conceivable that Angelina was among those captured.

Alternatively, she may not have been taken from Bursa but in a residence in Yenisehir where Olivera Lazarevic, her daughters, and servants resided.

After her capture, she was sent to Emir Timur's camp, where she remained for a period before being presented as a "gift" to King Henry III of Castile. At that time, Timur had received an embassy from the King of Castile, led by Don Payo Gonzalez de Sotomayor and Don Hernan Sanchez de Palazuelos, and upon their departure, he decided to send them off with Christian maidens to be given to Henry III of Castile. Both of these noblemen eventually married the other maidens who accompanied Angelina.

Arrival In Castile

Upon her arrival in Castile in 1403, while passing through Seville, Angelina caught the attention of a Genoese poet named Francisco Imperial, who was residing in the same city at the time. He composed a poem dedicated to her, which has survived to this day. From his poem, it can be inferred that Angelina was a woman of great beauty who captivated those around her as she traveled through Castile.

Upon reaching the Alcazar of Segovia, where King Henry was residing, the king, moved by pity for her and her entourage, took them under his protection.

Marriage To Don Diego González de Contreras

Around 1403, she married Don Diego González de Contreras, a knight and nobleman in the court of Henry. It is believed that the marriage was arranged by Henry, who likely sponsored the maidens' stay at court and their dowries.

Angelina, renowned for her beauty, likely had several suitors vying for her hand, but Don Diego, Lord of the house of Contreras, was ultimately chosen as the most suitable candidate by the King.

Diego is thought to have been well in his 70s at the time of his death in 1437, making him around 36 to 45 years old at the time of his marriage to the 22/23 years old Angelina.

The noble couple later took up residence in the Contreras’ ancestral home in the parish of San Juan de los Caballeros, Segovia, where Diego held the position of perpetual Regidor of Segovia, a hereditary title that would later pass to his son.

The couple welcomed two sons together, Fernán Gronzález de Contreras, who would later succeed his father as Regidor of Segovia, Juan González de Contreras, and possibly a daughter, Doña Isabel González de Contreras.

Later Life

Angelina likely led a noble and tranquil life as the wife of a nobleman in her husband’s ancestral home, where she also cared for her children.

It is believed that she passed away sometime after her husband died in 1437. However, historians have not been able to conclusively prove this theory. What is known is that she was certainly laid to rest in Segovia, where her body was buried in the church of San Juan.

The inscription on her tomb read as follows:

"Here lies the honored Dona Angelina of Greece, daughter of Count Ivan and granddaughter of the King of Hungary, wife of Diego González de Contreras."