#helpmeet literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

summary of the Titus 2 movement

from Saving Sex: Sexuality and Salvation in American Evangelicalism by Amy DeRogatis (2015) pp.97-102

transcript under the cut

[…] families. Pro-natalists use this argument to define themselves against culture and other evangelicals.

Open Embrace, and other books like it, circulate among conservative Protestant women in loosely affiliated groups that identify with the labels Titus 2 or “Biblical Womanhood.” There is no one specific denomination or umbrella group that coordinates groups within this movement. The individuals who blog, write books, run workshops and seminars promoting Biblical Womanhood, or who identify as Titus 2 women, may hold differing theological views and practices. Some tend toward Reform Protestantism; others are more charismatic. Titus 2 writers are united around the belief in the inerrancy of Scripture and the effort to define the meaning of biblical womanhood—the view that men are the head of the household and obedience to a husband is ultimately obedience to God’s will—in their everyday lives.

There is a spectrum among Titus 2 ministries but the majority affirms that married women should fulfill their biblical role through homemaking skills, childrearing, and following their husbands’ leadership. This goal typically is portrayed as a countercultural position that is challenging for young wives who have grown up in country that supports feminism. Typically in the Titus 2movement, men are not characterized as brutes who force women to stay in the home and serve them. Women choose this role. Itisthe job of older women to teach younger women that true liberation comes from fulfilling their proper biblical roles.

Some—but not all—of these groups also oppose contraception. Whether they allow for family planning or not, biblical women position themselves against feminism, which they believe destroys godly families, ruins the lives of women with false promises, sanctions unbiblical sexuality, and promotes a pagan religion.

THE EXCELLENT WIFE

Biblical womanhood is defined by the most visible leaders of Titus 2 as an effort to reclaim women’s proper scriptural role of “helpmeet.” According to Nancy Leigh DeMoss, older women must teach younger women to serve their husbands and God before all others, and together they will change the world. In her words, it will be “a revolution” (unlike feminism) “that will take place on our knees.”

Writers like DeMoss find biblical authority and definitions for female submission throughout Scripture. For specifics, however, they focus on Titus 2:3- 5. In this letter from the Apostle Paul to Titus, his colleague living in Crete, Paul provides rules for organizing new churches, including the proper roles for Christian men and women. The specific verses state:

“Likewise, teach the older women to be reverent in the way they live, not to be slanderers or addicted to much wine, but to teach what is good. Then they can urge the younger women to love their husbands and children, to be self-controlled and pure, to be busy at home, to be kind, and to be subject to their husbands, so that no one will malign the word of God.”

Besides detailing the qualities of a “good” woman (modest, loves her children, etc.), proponents of biblical womanhood emphasize wifely submission to support the word of God. A Christian wife’s willing submission to her husband, they explain, is a unique, daily way of witnessing to Christ.

There are a range of views regarding the meaning and practice of wifely submission based on Titus 2:3-5. Some glorify the Christian homemaker and her ability to provide hospitality. Others instruct women to stay with physically and emotionally abusive husbands— abused women should look to Christ, the divine model for suffering. Still others present an expansive vision of biblical womanhood, explaining that women are created by God to excel at multi-tasking in all areas of life, not simply in homemaking. Monique Mack, the founder of Titus 2 Women’s Network, praises a woman’s God-given abilities but does not specifically state that women work only in the home.

Women, Wife, Mother, wherever you find yourself in the following pages, you are unique. God masterfully created you with enormous ability. As women we have the ability to effectively function in nearly any arena that we enter. As mothers we have a tremendous ability to multi-task in the greatest sense of the word. As wives, He called us “helper” and enabled us as such to bring a greater capacity to the human relational experience. We are uniquely fashioned to bring a level of fulfillment to those we are connected to. God has duly equipped and enabled us to be triumphant in multiple roles.

Biblical womanhood is a fluid category that can include single, married, and widowed women who may or may not be mothers or homemakers.

Still, the majority of Titus 2 writers believe that women can best fulfill their biblical roles from within the home. Homemaking is a sacred calling. Here again there is a range of opinions regarding women’s roles and authority within the household. Some Titus 2 writers affirm that women are in charge of the domestic sphere. A few writers believe that husbands should be in control of all matters in the family, including household management.

In her 2009 book Quiverfull, Kathleen Joyce notes that “among some purists, it means submitting a list of daily activities to one’s husband for approval and following his directions regarding work, going to church, clothing, head covering, and makeup choices, as well as what a wife does with the remainder of her time. Sexually, it means being available at all times for all activities (barring a very limited number of ‘ungodly, ‘homosexual’ acts).”

Despite these range of opinions, all Titus 2 women agree that God created them as distinct from men. Women have unique roles, talents, and obligations to their husbands, children, extended family, other women, as well as to the church. These roles and obligations are given by God and found in Scripture.

Biblical womanhood, according to Titus 2 proponents, offers women a role in Christian missions without leaving the home. Authors such as Martha Peace consider a Christian woman’s cheerful submission to her husband’s authority as a form of ministry to him and to others. Peace looks to examples of celebrated Christian wives such as Edith Schaeffer, author and wife of Francis Schaeffer, who created a hospitable household and supported her husband even when he made poor decisions for the family. This, according to Peace, was Edith Schaeffer’s “accidental” contribution to her husband’s ministry.

Creating a beautiful home with dutiful children and a happy husband, Peace believes, presents a compelling witness to non-believers. Homemaking becomes a form of missionary work. Lonely and unsaved men need look no further than the honored Christian husband, admired by his wife and children, living in a peaceful, charming home, to find compelling non-theological reasons to accept Christ.

Peace and many other writers make clear that this complementarian understanding of spousal roles does not define wives as lesser than husbands. Each simply has distinct roles and obligations within marriage. The husband’s is to provide for and guide the family; the wife’s to support the husband in all of his endeavors and nurture the children.

Many of the leaders of the Titus 2 movement turn to the life and writings of Edith Schaeffer for inspiration. Edith and Francis Schaeffer were missionaries to Switzerland sent by the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions. In 1955 they started L’Abri (meaning “shelter”) in their home.

Over time the community grew and by the 1970s L’Abri became known as a place for evangelical youth to stay for a few months. There, they engaged in heated discussions about philosophy, theology, art, music, culture, and literature. Francis Schaeffer presided at the center of the community, a charismatic preacher and teacher who desired to meld conservative Protestant doctrine with the history and intellectual concerns of Western culture.

Edith Schaeffer developed a reputation in evangelical circles as an extraordinary hostess who cheerfully cooked and cleaned for countless young adults who backpacked to her house and dropped in for a few months. Schaeffer wrote over a dozen books but the most important for Titus 2 women is her 1971 Hidden Art, later retitled The Hidden Art of Homemaking.

Hidden Art provides artistic inspiration for home design using natural and readily available resources (such a pinecones or scraps of material). In her slim book Schaeffer makes a case for the power of beauty and art to enrich a family’s life even in small and homespun ways. In her view, the home provided daily opportunities for a woman to express her creativity and love for her family.

Martha Peace is not the only conservative Protestant woman who valorized Edith Schaeffer. In the 1970s and 1980s her thrifty ideas and focus on the beauty of homemaking caught the attention of many Titus 2 women, who have gone on to enthusiastically recommend and cite her book over the years. In his 2011 memoir, her son Frank who left his family’s faith writes:

“An Edith Schaeffer cult (made up mostly of born-again middle-class white American women) grew up around Mom’s books after she began to be published in the late 1960s. I’ve met countless women who say that they raised their children ‘according to Edith Schaeffer.’ Of course what they mean is that they raised their children according to the ‘Edith Schaeffer’ fantasies they encountered in her books.”

Whether fantasy or reality, Edith Schaeffer’s life and writings provide a model of the quintessential Titus 2 woman who is a husband’s “helpmeet.”

Martha Peace’s portrait of a godly wife represents a fairly mainstream evangelical view on gender roles. The theological stance that men and women have distinct roles that “complement” each other in marriage was codified at the Southern Baptist Convention’s annual meeting in 1998. The preferred language for the wife’s God-given role in Titus 2 literature is “helpmeet.”

Peace explains, “Basically, we have said that the wife’s role is to glorify and submit to her husband. She was created to fulfill her role as ‘helper’ for her husband. It’s easy to see Eve’s role, but what about you? How, practically, can you carry out your God-given role?” The key to success and happiness in Christian marriage is for each person to fulfill his or her specific role and respect the unique qualities and distinctions between husband and wife. Trouble begins when either spouse acts outside of their God-given gender role.

On the margins of the Titus 2 spectrum are authors like Debi Pearl. In Created to Be His Help Meet, Pearl suggests that even in abusive situations women are called by God to remain with their husbands. She believes that this type of submission is a visible and important testimony to faith. According to Pearl, even the most loathsome husband should be respected and supported. Submission to an awful husband is godly because it is ultimately service to Christ.

“If you look at your husband and can’t find any reason to want to help him—and I know some of you are married to men like that—then look to Christ and know that it is He who made you to be a help meet. You serve Christ by serving your husband, whether your husband deserves it or not.”

Pearl urges women to look to all areas—including the tiny details of their lives—to find a reason that they may be the cause of their husband’s discontent or failures. “Always remember that the day you stop smiling is the day you stop trying to make your marriage heavenly, and it is the first day leading to your divorce proceedings.”

Some husbands will act in despicable ways toward their wives. This, however, is not a reason for divorce. A wife should always find ways to improve herself in her husband’s eyes and that effort will save her marriage. Marriage always requires sacrifice.

It is tempting to cast Debi Pearl as a radical outlier. For example, the blogger Mary Kassian of “Girls Gone Wise,” a blog dedicated to promoting biblical womanhood, characterized Debi Pearl as “fringe and extremist. She certainly is not representative of the modern complementarian movement.”

But her position is not as far-flung as some proponents of biblical womanhood have argued. John Piper, one of the founders of the Biblical Council on Manhood and Womanhood, author, and Chancellor of Bethlehem College and Seminary, stated in 2009 that women should be able to endure some physical abuse in marriage.

“If it’s not requiring her to sin but simply hurting her, then I think she endures verbal abuse for a season, and she endures perhaps being smacked one night, and then she seeks help from the church.”

Piper is clear that simply being hurt does not warrant a woman’s refusal to submit to her husband’s authority. Women are sometimes called to sacrifice themselves for the sake of their marriage. A wife who finds herself in this situation should call the church, not the police.

#evangelical#exvangelical#biblical womanhood#christian patriarchy#titus 2#titus 2 ministries#complementarianism#john piper#debi pearl#mary kassian#nancy leigh demoss#monique mack#martha peace#edith schaeffer#francis schaeffer#L’Abri#frank schaeffer#helpmeet#helpmeet literature#quotes#amy derogatis#mac’s bookshelf#image described#intimate partner violence#domestic violence#abuse#patriarchy#misogyny#❌ian patriarchy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A word can have such force, and a name is an entire incantation.

– Naben Ruthnum, Helpmeet

#helpmeet#nabenruthnum#spilled quotes#horror fiction#poets on tumblr#booklr#quoteoftheday#writers on tumblr#readers on tumblr#spilled ink#quoteblr#literary quotes#literati#horror literature#book recommendations

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Helpmeet by Naben Ruthnum

Warning: This book review will contain spoilers. I have tried several times to re-format my analysis in a way that doesn’t give away too much of the content, but with the depth at which I prefer to discuss what I’ve read, it is simply not possible for any of my reviews to be completely spoiler-free. If you do wish to read this book, I encourage you to purchase it for yourself. Keep in mind that I do not claim to be any sort of real literary critic. I am simply one of many people online who enjoys publicly stating their opinions.

Title: Helpmeet

Author: Naben Ruthnum

Publication Year: 2022

Genre: Horror Fiction, Historical Fiction, Gothic Fiction

Average Goodreads Rating: 3.4/5

My Personal Rating: 4.5/5

Pages: 69

Date Started: December 25th, 2024

Date Finished: December 28th, 2024

Synopsis: It's 1900, and Louise Wilk is taking her dying husband from Manhattan to the upstate orchard estate where he grew up. Dr. Edward Wilk is wasting away from a mysterious affliction acquired in a strange encounter: but Louise soon realizes that her husband's worsening condition may not be a disease at all, but a transformative phase of existence that will draw her in as much more than a witness.

Going into this book, all I knew was that this story involved some type of body horror, which for me, was a major selling point. As someone who has been religiously watching horror movies since before my developing mind began to form retrievable memories, there is very little that still makes my skin crawl and my heart race. One of those such things just so happens to be body horror. We, as humans, can run from knife-wielding maniacs and hide under the covers until the monsters go away, but what we cannot run from is our own bodies. We are confined to these vessels, and when there is a flaw in the system, it arouses a primal type of dread; the feeling of “god, I hope that never happens to me”. In the story of a wife and her gradually rotting husband, there is no role that seems ideal to be played.

While I was confident that I would find, at least, a moderate level of enjoyment in this book, what truly surprised me was just how engaged I was. For years, reading has felt more like a chore than an activity to be cherished, and thus, I found myself taking a step back from literature. Even now, with my renewed motivation, I often still find myself dreading that time of night when it’s time to pick up my book and settle down without a screen. This story, however, had me coming back at every opportunity. I read in favor of sleeping, I read to put off countless writing projects–when I say that I was itching for each new chapter, I truly mean it. The descriptions of Edward’s deterioration were vivid enough to leave me feeling uneasy, and I found myself begging for some sort of levity, grasping at straws for answers regarding exactly what was causing his body to decay. While I did enjoy the ending overall, I will confess that upon the revelation of the sinister antagonist, I was rather underwhelmed. Cosmic horror and the likes simply doesn’t appeal to me at most times, and for me, it was difficult to comprehend exactly what the creature itself may have looked like. Having said that, I was pleased when it was clarified that the creature was something that has been here for a long time, rather than something from space or an alternate dimension; new to this world and eager for a host.

Perhaps this is a common opinion, but personally, my favorite character in this narrative was the final version of Louise Wilk. Despite the strife Edward put Louise through in life, there is still something so inherently romantic about finding a life literally inside the body of your deceased spouse. The concept of two becoming one, of two souls and two minds speaking to one another internally until they become so deeply fused that they cannot tell where one ends and the other begins, is something that I can only hope to mimic someday–metaphorically, of course!

Favorite Quotes:

“But she never tended to anyone who mattered, until she married someone who did.” (pg 20)

“Isn’t the earth better off after a burning?” (pg 35)

“I cannot explain to you how it feels because I am too cowardly to feel it.” (pg 40)

“A word can have such force, and a name is an entire incantation.” (pg 41)

“They could feel, in the drifting moment just before or just after sleep, a flower between and behind their lungs. Its roots wrapped around their joined vertebrae, and it grew slowly, careful not to exceed their body until they died.” (pg 67)

#text post#lambkin reviews#book review#booklr#helpmeet#naben ruthnum#horror fiction#historical fiction#gothic fiction#literature quotes#literature reviews#horror literature

0 notes

Note

1 and 24 for the book ask!! :D

Thank you! I track these things obsessively. I've read 28 full length books! And I've DNF'd 12 books.

thanks for asking!

Here's a list of both:

Read (bold = favorite)

Patricia Wants to Cuddle - Samantha Allen

Negative Space - BR Yeager

The House in Abigail Lane - Kealan Patrick Burke

Crying in H Mart - Michelle Zauner

Different Seasons - Stephen King

The Fall of the House of Usher - Edgar Allan Poe

Sorrowland - Rivers Solomon

Found: An Anthology of Found Footage

Scanlines - Todd Keisling

This is Where We Talk Things Out - Caitlin Marceau

The World Cannot Give - Tara Isabella Burton

Sharp Objects - Gillian Flynn

Fluids - May Leitz

The Elementals - Michael McDowell

Educated - Tara Westover

Say Nothing: A True Story of Memory and Murder in Northern Ireland - Patrick Radden Keefe

Little Fires Everywhere - Celeste Ng

Psychic Teenage Bloodbath - Carl John Lee

Good Omens - Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman (reread)

Mister Magic - Kiersten White

The Last Days of Jack Sparks - Jason Arnopp

The Bayou - Arden Powell

The Iliad - Homer

Helpmeet - Naben Ruthnum

The Weight of Blood - Tiffany D. Jackson

A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier - Ishmael Beah

Suffer the Children - Craig DiLouie

Intercepts - TJ Payne

and i'm hoping to finish at least 5 more books, but we shall see! (Les Mis, The Once Yellow House, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Penance, and Pet Sematary)

as for DNFs;

Ghost Wall - Sarah Moss: Too tedious even for me

Bad Feminist by Roxane Gay: I feel there's more up to date feminist literature to read

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes - Catherine Lacey: as a Mexican, the way she talked about death and corpses left a bad taste in my mouth.

Kentukis - Samanta Schwelbin (Little Eyes in the translation): Gave up on this author, the stories went nowhere at all.

Heaven - Mieko Kawakami: I felt this book was going to leave me with nothing

Sleeping Giants - Sylvain Neuvel: This is just the set up for something very NGE and I didn't wanna commit to a saga

Anybody Home? by Michael J Seidlinger: Tries too hard

Ugly Girls - Lindsay Hunter: Wouldn't give me what i was craving atm

The Children of Red Peak - Craig DiLouie: Too infodumpy

Brutes - Dizz Tate: Wasn't providing what I needed

A Certain Hunger by Chelsea G. Summers: cringe

Stolen Tongues - Felix Blackwell: A creepypasta turned book that extends too much, weird treatment of Native American characters.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

E

stee Williams faced her TikTok followers and detractors head-on with full makeup, coiffed blonde waves, and a floral-printed puff sleeve peasant top cinched at the center with a tidy bow. She felt obligated to clarify a few things about what it really meant to be a “tradwife”—a portmanteau denoting “traditional wife”: “So the man goes outside the house, works, provides for the family. The woman stays home, and she’s the homemaker. She takes care of the home and the children if there are any.”

But Williams’ definition moved beyond the idyllic character of June Cleaver or even the Victorian-era presumptions of separate spheres. “Tradwives also believe,” she insisted, “that they should submit to their husbands and serve their husbands and family.” Williams was quick to defend her position against potential critics, noting that she did not believe women were inferior to men, but that they had an equally important but different role.

Tradwives have not escaped the notice of journalists and social commentators who track their popular rise on various social media platforms. Some analyses of the tradwife trend reference the 1950s, while other commentators focus on influencers like Hannah Neeleman of Ballerina Farm fame, who perform the role of 19th-century homesteaders (despite Neeleman’s occlusion of her husband’s inherited wealth). But the ideology behind the fad has much deeper—and more insidious—roots in American history.

Although the use of social media and the power of tradwife “influencers” may be new, the use of media to reinforce conservative social norms is not. Women in 18th-century Anglo-America, for example, were inundated by “conduct literature”: writing in magazines, newspapers, and novels that dictated how they ought to behave, especially in their marriages.

Conduct literature provided women and men with pointed guidance about how to choose a spouse.

Women were ostensibly imbued with a significant choice in this regard, yet this choice was highly circumscribed. Once she wed, she had little choice remaining within this marital union. The “good wife,” for example, was to be “strictly and conscientiously virtuous...chaste, pure and unblemished in every thought, word and deed.” More prescriptions followed: “she is humble and modest from reason and conviction; submissive from choice, and obedient from inclination.” She was the helpmeet of her husband, “always” making it “her business to serve and oblige” him. Her happiness was contingent upon his own.

Social expectations for wives likewise filled the pages of novels like The Coquette (1797) and Pamela (1740) which extolled the virtues of white femininity. These popular books were entertaining for readers, much like contemporary tradwives’ social media posts, but also didactic in their demonstrations of what would become of “fallen” women who had chosen their partners poorly. For instance, Eliza Wharton, The Coquette’s protagonist, died giving birth to a stillborn, illegitimate child after eschewing a pious suitor in favor of an attractive cad.

Eighteenth and early 19th century American women’s submission was not merely suggested in prescriptive literature; it also had the force of law. Married women lived under the legal doctrine of coverture, in which their individual, legal identities were subsumed under those of their husbands. The oft-cited legal commentator, Sir William Blackstone—foreshadowing the refrain of tradwives today—asserted that wives’ submission to their husbands was “for her protection and benefit,” making her “a favourite” under the law.

In reality, coverture erased wives’ independent legal identities under the guise of protection and care from husbands. This legal framework dictated that a married woman owned no property in her own name; any wages she earned belonged to her husband.

Under coverture, wives had no clearly defined parental rights, and their bodies were not their own. Marital rape, for example, was not considered a crime in the 18th century (and did not become a crime in all 50 states until 1993). In certain circumstances, domestic abuse was condoned as a corrective measure to the submissive wife; Blackstone’s Commentaries indicate that “moderate correction” was permissible if it fell within “reasonable bounds.”

Women’s access to divorce in early American history was likewise limited. Some colonies, and later states, permitted divorce under certain circumstances (and the number of states providing for access to marital separation would expand over time), though relatively few women availed themselves of this legal mechanism. Given the other stringencies of coverture, life as a single woman and a single mother likely proved a greater trial for many.

Eighteenth- and 19th-century women did not possess rights as full citizens in the United States. Historically, citizenship rights have been linked to gender, wherein the obligations and thus the benefits of citizenship depended on sex. Tradwives who claim that women are “naturally” suited for submission to male authority and thus deserving of “protection” from men are implicitly condoning women’s second-class citizenship.

Coverture thus cast a long shadow over women’s rights in American history. Each generation of American women seemingly needed to be reminded—through the law, economic constraints, and even now in social media—of the “naturalness” of her submissive role. These constant reminders, however, suggest equally constant remonstrations from women, albeit with mixed results.

In the 19th century, for example, women’s organizations sought to change the law at the state level to allow married women to own property in certain circumstances, finding some success. But it was not until the 1970s that married women had the right to obtain credit cards separate from their husbands.

The 19th Amendment’s passage in 1920—nearly a century and a half after this nation’s founding—granted some women suffrage, though it would be decades before all women could vote. Women could not serve on juries until the 1870s, although even the recent history of their inclusion has been mixed. Tradwives often insist, as Williams puts it, that their choices “[don’t] mean that we are trying to take away from what woman [sic] fought for.” In her video, she adds that she and other tradwives do not have an agenda: “It’s not really a movement. Nobody’s pushing it. People are typically just living it and maybe showcasing their lifestyle like me.”

But their glorification of these views obscures the reality of the consequences of women’s submission and subordination to men, whether it is a “choice” or not.

Some do not want it to be a choice at all. Speaker Mike Johnson called for a return to “18th-century values” more than a decade ago. An Alabama State Supreme Court justice’s recent concurring opinion in the case which ruled that embryos were persons under the law invoked the Seven Mountains Mandate, which seeks to impose Christian nationalism over many realms of American life, including government. There is even a growing movement to outlaw “no fault” divorce in favor of promoting “covenant marriages.”

Tradwives figure importantly in this movement. In many ways, they are exploited as pawns of the right, laundering extremist views and transforming them into ostensibly more palatable packaging. This was perhaps the intent behind Senator Katie Britt’s ill-received response to President Biden’s State of the Union address in early March; Senator Tommy Tuberville indicated as much. Yet her performance of womanhood—her breathy vocalization dubbed “fundie baby voice” by critics—appeared as empty as her kitchen and did nothing to soften the blow of her party’s apocalyptic interpretation of current events.

Yet tradwives also entice their followers with soothing videos of sourdough bread baking and #OOTDs evoking prairie chic or Donna Reed, with dangerous consequences. Their advocacy for the ideology and principles of so-called “traditional” gender roles in marriage ultimately have the effect of promoting a return to the days of coverture and an erasure of the hard-fought (if incomplete) gains of women’s rights activists throughout American history.

Jacqueline Beatty, Ph.D. is Assistant professor of history at York College of Pennsylvania and author of In Dependence: Women, Power, and the Patriarchal State in Revolutionary America.

1 note

·

View note

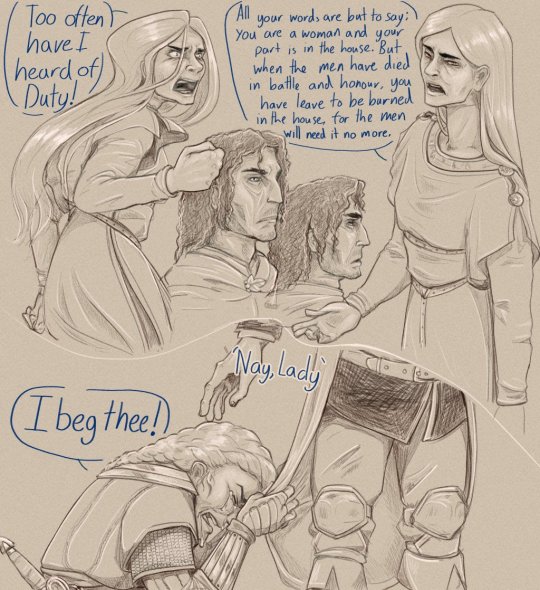

Photo

The letter he sends to Michael in 1941 full of advice about relationships with women is generally the source I go too whenever I have these questions. Although, as I've always said, we don't really need to worry about what Tolkien's thinking anymore in regards to what his books 'mean', they should speak for themselves. But either way, we still might as well hear what he has to say about his own beliefs, like;

In this fallen world the 'friendship' that should be possible between all human beings, is virtually impossible between man and woman.

[-]

The sexual impulse makes women (naturally when unspoiled more unselfish) very sympathetic and understanding, or specially desirous of being so (or seeming so), and very ready to enter into all the interests, as far as they can, from ties to religion, of the young man they are attracted to. No intent necessarily to deceive: sheer instinct: the servient, helpmeet instinct, generously warmed by desire and young blood. Under this impulse they can in fact often achieve very remarkable insight and understanding, even of things otherwise outside their natural range: for it is their gift to be receptive, stimulated, fertilized (in many other matters than the physical) by the male. Every teacher knows that. How quickly an intelligent woman can be taught, grasp his ideas, see his point – and how (with rare exceptions) they can go no further, when they leave his hand, or when they cease to take a personal interest in him.

[-]

You may meet in life (as in literature* ) women who are flighty, or even plain wanton — I don't refer to mere flirtatiousness, the sparring practice for the real combat, but to women who are too silly to take even love seriously, or are actually so depraved as to enjoy 'conquests', or even enjoy the giving of pain – but these are abnormalities, even though false teaching, bad upbringing, and corrupt fashions may encourage them. Much though modern conditions have changed feminine circumstances, and the detail of what is considered propriety, they have not changed natural instinct. A man has a life-work, a career, (and male friends), all of which could (and do where he has any guts) survive the shipwreck of 'love'. A young woman, even one 'economically independent', as they say now (it usually really means economic subservience to male commercial employers instead of to a father or a family), begins to think of the 'bottom drawer' and dream of a home, almost at once.

The letter itself is actually pretty interesting and I've cut out only the clearest misogyny sections but it goes into his opinions in far more detail. I kind of enjoy reading it, it gives this nuanced examination of precisely how at least A man of the time and with such misogynistic views percieves the women around him and his relationship with them without any like... hold back or sense of trying to defend himself. So it comes across with a lot more candour and so within that a kind of less clinical more understandable tone, like I can get how a human man might believe these things.

But with that being said, I don't think there's really a mystery to solve here right? Aragorn tells everyone including the reader what Eowyn's deal was over her sickbed in Minas Tirith. We are actually meant to percieve Eowyn as lying when she explains her desires and motives in this scene, her true secret object was always to follow Aragorn (whom she fancies herself in love with), and in being rebuffed by him she is sent into literal suicidal despair. Like I am fairly convinced that was Tolkien's entire intent. I ignore it with prejudice, I will never ever be convinced that is what this Eowyn's story is about, but I still think that's what Tolkien believed he wrote. Even Faramir declares this to be the case by the end, to Eowyn's face, during their so called love confesssion, and she does not correct him. It's truly grim honestly, Eowyn should get a divorce and change her pronouns.

Got real exercised about Peter Jackson’s defanged Eowyn and needed to draw my girl going slowly out of her mind as Aragorn’s apathy makes her more and more desperate until she finally breaks free of the chains that bind her and decides that if she is to die, she would choose how.

576 notes

·

View notes

Note

1/2 On a darker note, a reason Jo could have found Friedrich desirable as a husband and not Laurie (outside her mad attraction to Fritz and her lack of attraction to Laurie) is because she knew what Victorian Wifehood was, and knew she'd much rather be the helpmeet of a poor schoolteacher (as she loved children) than of a wealthy partyboy/socialite (considering she hated the culture of conspicuous consumption that she'd have to build her life around).

2/2 True, they ended up with a more egalitarian marriage than that, (they ended up with one of the most egalitarian marriages in C19 literature!) but her choice of Fritz vs Laurie is very much related to the question of, "What do I want to do with my life?

--------------------------------------

Is it just me, or do I get some real confusing asks? On a darker note? How is wanting a partner who would be more of an equal, treat her like a partner rather than a mother a darker note? I think it’s pretty normal for anyone who is seeking a romantic partner to pick someone who is going to be an equal partner and love them as they want to be loved. You are right in the fact that Jo and Friedrich do have one of the most egalitarian marriages from 19th century literature, but the question “what do I want to do with my life?” isn’t related exactly to Friedrich. She was given the house before she married him, she knew that she wanted to do, making Plumfield a school as well as continuing to farm the land. And we see in the sequel that Jo gets to write, and all this regardless of who she would have married. True, Laurie would have stifled her writings while Friedrich supported her, but she would have just done as she pleased, and I am sure that even if she got Plumfield before Friedrich, she would have done just the same thing.

Jo never relied on anyone’s opinion of her life in order to live it, so why should that have changed even when there were two men who vied for her love?

“Her choice of Fritz vs Laurie “ Choice? You think Laurie was even an option for marriage? She made it very clear she was not interested in marrying him. When he proposed, she made it very clear that she would rather be an old maid then ever marry Laurie, because she didn’t love him.

“I don’t know why I can’t love you as you want me to. I’ve tried, but I can’t change the feeling, and it would be a lie to say I do when I don’t.”

That’s pretty clear isn’t it?

“I wish you wouldn’t take it so hard, I can’t help it. You know it’s impossible for people to make themselves love other people if they don’t,” cried Jo inelegantly but remorsefully, as she softly patted his shoulder, remembering the time when he had comforted her so long ago.

“They do sometimes,” said a muffled voice from the post. “I don’t believe it’s the right sort of love, and I’d rather not try it,” was the decided answer.

If that isn’t clear enough, how about this?

“I shall always be fond of you, very fond indeed, as a friend, but I’ll never marry you, and the sooner you believe it the better for both of us—so now!”

Jo never thought of Laurie as an option, even when she was lonely, she wouldn’t have married him because she loved him any different. Here in the conversation she has with Marmee, in Chapter 42.

“I knew you were sincere then, Jo, but lately I have thought that if he came back, and asked again, you might perhaps, feel like giving another answer. Forgive me, dear, I can’t help seeing that you are very lonely, and sometimes there is a hungry look in your eyes that goes to my heart. So I fancied that your boy might fill the empty place if he tried now.”

“No, Mother, it is better as it is, and I’m glad Amy has learned to love him. But you are right in one thing. I am lonely, and perhaps if Teddy had tried again, I might have said ‘Yes’, not because I love him any more, but because I care more to be loved than when he went away.”

Overall, Jo would have done just as she pleased, regardless of who she ended up with.

#answered asks#little women#Jo March#friedrich bhaer#theodore laurence#jo and friedrich#jo x friedrich#anti jo x laurie#anti jo and laurie

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intelligence may be located in the brain, but it affects other parts of the anatomy. Consider the pelvis as a secret theater where thinking and walking meet and, according to some anatomists, conflict. One of the most elegant and complicated parts of the skeleton, it is also one of the hardest to perceive, shrouded as it is in flesh, orifices and preoccupations. The pelvis of all other primates is a long vertical structure that rises nearly to the ribcage and is flattish from back to front. The hip joints are close together, the birth canal opens backwards, and the whole bony slab faces down when the ape is in its usual posture, as do the pelvises of most quadrupeds. The human pelvis has tilted up to cradle the viscera and support the weight of the upright body, becoming a shallow vase from which the stem of the waist rises. It is comparatively short and broad, with wide-set hipjoints. This width and the abductor muscles that extend from the iliac crests--the bone on each side that sweeps around towards the front of the body just below the navel--steady the body as it walks. The birth canal points downward, and the whole pelvis is, from the obstetrical point of view, a kind of funnel through which babies fall--though this fall is one of the most difficult of human falls. If there is a part of anatomical evolution that recalls Genesis, it is the pelvis and the curse "in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children."

Giving birth for apes, as for most mammals, is a relatively simple process, but for humans it is difficult and occasionally fatal for mother and child. As hominids evolved, their birth canals became smaller, but as humans have evolved, their brains have grown larger and larger. At birth the human infant's head, already containing a brain as big as that of an adult chimpanzee, strains the capacity of this bony theater. To exit, it must corkscrew down the birth canal, now facing forward, now sideways, now backwards. The pregnant woman's body has already increased pelvic capacity by manufacturing hormones that soften the ligaments binding the pelvis together, and toward the end of pregnancy the cartilege of the pubic bone separates. Often these transformations make walking more difficult during and after giving birth.

It has been argued that the limitation on our intelligence is the capacity of the pelvis to accomodate the infant's head, or contrarily that the limitations on our mobility is the need for the pelvis to accomodate birth. Some go further to say that the adaptation of the female pelvis to large-headed babies makes women worse walkers than men, or makes all of us worse walkers than our small-brained ancestors. The belief that women walk worse is widespread throughout the literature of human evolution. It seems to be another hangover from Genesis, the idea that women brought a fatal curse to the species, or that they were mere helpmeets along the evolutionary route, or that if walking is related to both thinking and freedom they have or deserve less of each. If learning to walk freed the species--to travel to new places, to take up new practices, to think--then the freedom of women has often been associated with sexuality, a sexuality that needs to be controlled and contained. But this is morality, not physiology.

I got so annoyed by the ambiguous record on gender and walking that early one fine morning in Joshua Tree, while the cottontails were hopping in the yard, I called up Owen Lovejoy. He pointed to some differences between male and female anatomy that, he said, ought to make women's pelvises less well adapted to walking. "Mechanically," he said, "women are less advantaged." Well, I pressed, do these differences actually make a practical difference? No, he conceded, "it has no effect on their walking ability at all," and I walked back out into the sunshine to admire a huge desert tortoise munching on the prickly pear in the driveway.

Stern and Sussman had laughed when I asked them whether women were indeed worse walkers and said that as far as they knew, no one had ever done the scientific experiments that would back up this assertion. Great runners tend to converge in certain body types, whichever gender they are, they ruminated, but walking is not running, and the question of what constitutes greatness there is more ambiguous. What, they asked, does better mean? Faster? More efficiently? Humans are slow animals, they said, and what we excel at is distance, sustaining a pace for hours or days.

— Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Rebecca Solnit

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Jung perpetually links woman with nature as the terrifying wildness men must conquer and tame in order to incorporate into the self. Thus woman must struggle in a culture that considers her a minority. Woman often considers her needs inessential because women's identity is perceived and defined by men. To woman, struggling to define the Self, centuries of literature and symbolism that consider her man's helpmeet and support undermine her journey. As Simone de Beauvoir notes, "What peculiarly signalizes the situation of woman is that she - a free and autonomous being like all the human creatures - nevertheless finds herself living in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other.""

-- Valerie Estelle Frankel, 'From Girl to Goddess: the Heroine's Journey through Myth and Legend'

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

** Disclaimer: This particular bit of literature is from a little over 100 years ago ! This text is merely a fun glimpse into the past and is in no way claiming factual validity or otherwise today in 2022. Don’t shoot the messenger essentially - if there is misinformation here. I am simply transcribing it here for historical reference. Feel free to reblog and add further commentary if you’d like ! **

Here is an excerpt from ‘ The Book of Knowledge ‘ - A Children’s Encyclopedia from 1918. ( Page 5,923 to be exact ! ) This best serves as a reference when writing historical characters, as I will be transcribing verbatim the selected passages that I find interesting: The Meaning of Halloween || Things To Do On Halloween circa 1918 can be found under the cut!

• The Meaning of Halloween •

‘ Hallowe’en which brings to most of us visions of fun and jollity, is an old, old festival. The old Romans held it about the the first of November in honor of Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees. In Britain, the Druids celebrated a festival at the same time in honor of the sun god, and in thanksgiving for the harvest, and the two festivals seem to have become one in the mind of the Britons. When the people became Christians the early Church Fathers wisely let them keep their old feast, but gave it a new association by holding it in commemoration of all departed souls. The eve of the festival came to be called All Hallow E’en. The name comes from the old English word ‘ halwe ’, or as we now say ‘ Holy ‘. Many beliefs grew up about this feast, such as the belief that on this one night of all the year, the spirits of the departed were allowed to visit their old homes. In many parts of the old countries food was left, hearths were carefully swept, and chairs were set in order before the inhabitants of the villages went to rest. Many of the old superstitions, some of them going back as far as Pagan times, came to this country with our Puritan ancestors, and though they lost the meaning years ago, we still keep some of the quaint old customs.

• Things To Do On Halloween •

- Ducking For Apples -

Get ready two tubs, each half filled with water, one for the boys, one for the girls. Put in each a number of apples with long stems, each stem having a name very securely attached to it on a slip of paper. The fun consists in trying to catch one of the bobbing apples with the teeth; the apple must not be caught by the stem. The name attached to the apple is supposed to be the name of the future helpmeet of the youth or maiden who contrives to fish it out of the water. The hands must be fastened behind the back for this trick.

- Burning Nuts -

Name two nuts and place them on a shovel held over an open fire -- a gas log will do. Repeat this charm: ‘ Nuts I place upon the fire, and to each nut I give a sweetheart’s name. ‘ If either of the nuts hisses or steams, it shows that the owner of the name has a cranky temper. If the nuts pop together, and towards each other the friendship between the two persons will probably increase and grow warmer. If, however, one does not pop at all, or they fall away from each other, the feeling will grow cooler and the friends will be divided.

- Apple And Candle Trick -

Hang by the stout cord, attached to a hook in the ceiling, a short stick -- about eighteen inches long. The stick must be fastened so that it will balance horizontally. At one end of the stick fasten a short piece of lighted candle, at the other end fix an apple. Set the stick revolving rapidly, and let the players try to snatch the apple from it with their teeth.

- Apple Paring -

Peel an apple without breaking the skin, swing the paring round your head three times and let it fall to the floor over the left shoulder. The letter formed as it falls to the floor will give the initial of your future spouse.

- Combing Hair Before Mirror -

Comb your hair at midnight standing alone before a mirror by the light of a candle. If a face appears, in the glass , looking over your shoulder, it will be that of your future partner.

- Winnowing Grain -

Steal out into the garden or barn alone near midnight and go three times through the motion of throwing grain against the wind. The third time your future spouse will appear in some mysterious way, or you may gain some intimation of his or her station in life.

- Prophecy By Feathers -

Take three small, fluffy feathers. On three small pieces of paper write the words “ Blonde “, “ Brunette “, and “ Medium “ and attach these pieces of paper to the ends of the little quills. To make the test hold up the feathers by their tops, and with a puff of breath send them flying towards the table. The one that falls nearest to you tells the complexion of your true love. The test should be made three times to make the prophecy quite sure.

- Ghost Writing -

With a perfectly new pen, dipped in pure lemon juice, write a number of charms, or prophecies on small pieces of paper, and let them dry, when the writing disappears. Fold the slips of paper , and place them in a basket, from which each player draws one. When the pieces of paper are held over the flame of a lamp or candle, the heat causes the writing to reappear, and the prophecy can be read. This trick may be made quite mystical by appropriate ceremonies, such as reading the prophecies in a room dimly lighted by a small colored lamp over which the slips must be held. One person should read the slips one by one, and can add to the effect by reading very slowly or solemnly. The reader can be one of the players who has slipped out and assumed a long cloak, witch’s hat, and a small black velvet mask. ‘

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I took a Jewish women's literature class in college, and as I learned, there's unfortunately a reason why feminists tend to be so hypocritical about the Jews (like the Women's March thing): the reason is because Judaism was the first "Abrahamic" religion (before Christianity and Islam), so feminists blame Judaism for the rise of patriarchal social systems, since the Old Testament has Eve created as "helpmeet" for Adam. So feminists actually WANT Judaism gone, because they think it caused sexism.

I have never heard such a thing and to be honest, it sounds a bit dubious to me.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forest of a Thousand Daemons

By Geoff Wisner

Forest of a Thousand Daemons was written in 1938 in response to a literary contest sponsored by the Nigerian ministry of education. It is considered the first novel to be written in Yoruba and one of the first to be written in any of Africa's indigenous languages.

The book begins with a simple frame story. One beautiful morning, the narrator says, he was seated in his favorite chair, “settled into it with voluptuous contentment, enjoying my very existence,” when an old man came up to greet him, sighed, and told him to take down the story he was about to tell.

The old man explains that he was once a mighty hunter known as Akara-ogun or Compound-of-Spells. Over the next 140 pages or so, he describes his adventures in the forest and his clashes with a variety of supernatural beings.

The literal meaning of the book's title is “The Brave Hunter in the Forest of 400 Deities,” but the translator — none other than Wole Soyinka — explains that “four hundred” has a similar meaning in Yoruba to what we mean by “a thousand,” and that daemon is “closer in essence” to the Yoruba imale than gods, deities, or demons.

Much like Nabokov translating Eugene Onegin, Soyinka deploys obscure English words to convey shades of meaning and sort out the many types of creature in this tale. After an unsettling encounter with a warrior named Agbako, whose sixteen eyes are “arranged around the base of his head,” the hero is greeted by a beautiful woman who spells things out for him:

‘Akara-ogun, you are aware that even as dewilds exist on this earth, so do spirits exist also; even as spirits exist so also do kobolds; as kobolds on this earth, so are gnoms; as gnoms so also exist the dead. These ghommids and trolls together make up the entire thousand and one daemons who exist upon earth. I am one of them, and Helpmeet is my name...’

Like the better-known novel The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola, Forest of a Thousand Daemons is based in Yoruba folk tales, but although it came earlier than Tutuola’s book (which was written in English), it is less grotesque and more “traditional” in tone. One reason is that it is told not in the odd but powerful “broken English” of Tutuola but in the sophisticated, sometimes antique language of its translator.

The hunter’s meeting with Helpmeet suggests Pilgrim’s Progress, and the impression is reinforced a page later when he arrives at a city called Filth, “a place of suffering and contempt, a city of greed and contumely, a city of envy and of thievery...”

Elsewhere we seem to be in the world of Paradise Lost, since Christian and Yoruba myths coexist in the tale. On page 63, a ghommid with two heads and two horns tells the hunter, “I was one of the original angels who were much beloved of God, but I rejected the laws of God and His ways and engineered chaos in heaven. God saw that I was intractable, and that my genius was an evil one. He handed me to Satan to inflict agonies on me for seven years, and even so did it come about that I lived in Hell for seven clear years.”

Forest of a Thousand Daemons is said to have been a strong influence on The Palm-Wine Drinkard. Some of its grotesque creatures may also have helped inspire those in Ben Okri’s story collection Stars of the New Curfew. And on page 11 a smoke monster boils up from the ground that is startlingly similar to the one in the TV series Lost.

The language of Forest of a Thousand Daemons is sometimes odd or awkward, and Soyinka seems to have preserved its flavor. Recounting the third day of his journey, the hunter says, "I ate, filled up properly so that my belly protuberated most roundly.”

Yet peculiar as it sometimes is, the book has life, and helps bridge the gap between oral tradition and the modern literature of Nigeria — one of the most fertile on the continent.

Published May 21, 2010

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lost Stories, Waiting to be found

Recently, I attended a lecture about the migration of the Ojibwe from the Atlantic Coast to the Upper Great Lakes sometime over the past thousand years. The presenter was of the Anishinaabek, the true people of the Ojibwe, and her all-white audience was spellbound by her story of the epic migration, which had played out over centuries.

After her talk came many questions, one of which was what movies did she enjoy? She answered “Smoke Signals,” of course, and then “The Last of the Mohicans” and “Dances With Wolves.” After that, she was stumped.

What a loss, I thought, because only “Smoke Signals” is a film entirely about Native peoples. In every other film, from “Black Robe” to “Mohicans,” “Dances With Wolves” and “Little Big Man,” the protagonists are all white men and the Indians tend to be helpmeets or victims.

This extends to television, with Tonto serving the Lone Ranger and Mingo serving Daniel Boone in the ‘60s. In “Hell on Wheels,” the Indians have a sense of dignity, but inevitably they, too, aid in their own destruction at the hands of a transcontinental railroad, or serve as its victims. Only recently in “The Revenant” did a band of the Arikara get their due as being independent and dangerous adversaries of white trappers, demanding and receiving justice for a stolen daughter.

INDIANS IN LITERATURE

The image of the Indian as a helpmeet or a victim extends to literature. I’m eager to be corrected if I’m wrong, but as far as I know, the only major work of fiction about the Anishinaabek as they existed prior to the European invasion of North America is The Song of Hiawatha, published in 1855 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. This, despite the fact that Native peoples have occupied the Upper Great Lakes for up to 11,000 years and the Ojibwe are the second largest tribal unit in North America.

Based on a Christlike statesman of the Iroquois, Hiawatha was one of the bestsellers of the 19th century. It has long been derided as a poem which promoted the ideal of the “noble savage,” meaning nostalgia by white intellectuals for the Native peoples their forefathers murdered or transplanted in a genocidal sweep.

Yet, other than Hiawatha, one is hard-pressed to find works of fiction which deal with the Ojibwe before the advent of white invaders. There are many novels which deal with the post-Columbian epoch, including those by Louise Erdrich, Sherman Alexie and Tony Hillerman, but many are about Native peoples trying to get a leg up on their oppressors or survive the aftermath of ethnic cleansing. Other than Hanta Yo, the bestselling 1979 novel of the Sioux by Ruth Beebe Hill and a series of Hopewell-era novels by W. Michael Gear and Katherine O’Neal Gear there seem to be few, if any, major works of fiction which depict Native peoples in their absolutely free state of being before the white invasion.

ARROWHEADS & SPEAR POINTS

I find this strange because the prehistory of Native America is as rich with story material as anything found in Harry Potter, Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings.

I have a particular interest in this regard because my forthcoming book, Windigo Moon - A Novel of Native America, is set more than 400 years ago on the Upper Great Lakes, beginning in 1588, the so-called “Lost Century,” which was a devastating time for Native peoples. Spanning 31 years, Windigo Moon is a love story which ends in 1619, two years before the Anishinaabek met the first white man at present-day Sault Ste. Marie. This was the French explorer Etienne Brulé, who was reportedly later boiled and eaten by the Hurons for being too eager with their women.

It’s my hope that my novel will be a clarion call to Native writers to dig deeper into their own history, which is rich with opportunities for story-telling. It’s worth noting that story-tellers were among the most valued members of Anishinaabek society for thousands of years because they entertained their clan-mates through endless long winter nights with tales of animals, heroes, monsters, spirits and wayward humans.

Native American lore is well suited to historical fiction and magical realism. In Windigo Moon I take Anishinaabek myths and spirits at face value. My characters deal with ghosts, manitos and supernatural monsters in addition to the everyday challenges of survival, tribal politics, marital problems and human folly.

COMPARE & CONTRAST

So consider Harry Potter or The Lord of the Rings with their wizards and magical wands or rings. Ojibwe lore is filled with corollaries, including shamans with wizard-like powers and weapons or places imbued with spiritual energy. There are also mermen, pukwudgie fairies, manito spirits, talking animals, frost giants, windigo monsters, animal tricksters and more in Ojibwe legends.

Consider Game of Thrones with its dragons and feuding kingdoms. Ojibwe lore has mishepezhu, the lynx-head dragon of the Great Lakes, also, animiki, the thunderbird who wages eternal war with the monsters of the underworld. And even after the arrival of white invaders, Native peoples fought with neighboring tribes as they had for centuries with the same ferocity and political fervor as the kingdoms of Game of Thrones. There are an infinite range of story opportunities in those conflicts that might rival the best of anything on the New York Times bestseller list.

Consider Samson, Hercules or Achilles in Western mythology; Ojibwe mythology has Manabozho and Aayash to offer, shape-shifting demigods who walk among mortals performing good deeds. Manabozho figures in my own novel as the “great uncle” of the Ojibwe. I also have a character, Animi-ma’lingan, He Who Outruns the Wolves, a club-footed shaman who serves as the eyes and ears the Ojibwe Mide-wi-win Society of Shamans; he’s literally a spy traveling in the guise of a trader throughout the tribes of North America.

Moving on, consider the Greek gods of Mt. Olympus or the Norse gods of Asgard who are always poking their noses into popular fiction (we’re talking about you, Thor). Native American cosmology has hundreds of gods who might bend their will to literary service.

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about the lack of historical depth in Native American fiction is that this incredible trove of material has been hidden in plain sight while the reading public has gone gaga over the fantasy novels of writers from England or middle class white America. Surely, there is a Native version of Stephen King or George R. R. Martin awaiting discovery.

Native storytelling material has a close-to-the-bone authenticity that nothing like The Hobbit, The Dark Tower, The Wizard of Oz or One Hundred Years of Solitude can match in that Indians actually lived through the experience of their stories only a few lifetimes ago. Like the rough gems of emeralds, rubies and sapphires glittering in a stream, the myths and legends of Native America await any author willing to shape them into treasures of the imagination.

Robert Downes’ novel, Windigo Moon - A Novel of Native America, will be published September 5 by Blank Slate Press, a division of Amphorae Publishing.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Wife

D: Bjorn Runge

Before it is anything else, “The Wife” is the story of a woman’s face. Glenn Close plays Joan Castleman whose novelist husband Joe (Jonathan Pryce) wins the Nobel Prize for literature, and as she navigates the chaos of the days leading up to the ceremony, her face is a study of self-effacing placidity, of a woman who defines “helpmeet” to the point of requesting he not thank her in his acceptance speech. (“I don’t want to be that cliché.”). Later, while engaging in barbed repartee with a would-be biographer (Christian Slater, charming and sly) we see that her face is a mask and a shield, used to hide certain bitter truths from both without and within. And it’s cracking.

Runge’s film, based on a novel by Meg Worlitzer is a slick melodrama given life by its performances. Joe Castleman is his own type of cliché – a pompous and egocentric philanderer – but Pryce brings some depth to a man painfully aware of his limitations, especially after a plot reveal that’s not so much a twist as a slow rollout. And Joan is one of Close’s best and most mysterious performances. Even after the movie has resolved itself with a pat (if tragic) conclusion she still wears a face that tells us we’ve barely scratched the surface. She’s a sphinx.

0 notes

Photo

The Guardian – The £30m bookshelf: Pierre Bergé and the greatest stories ever sold

With Impressionists on their walls and priceless books on their shelves, Pierre Bergé and his former partner Yves Saint Laurent were the ultimate collectors. But now the art and YSL have gone, Bergé says it’s time ‘to attend the funeral’ of his library.

On an evening when Anonymous were berating the 1% in Trafalgar Square, I was in a book-lined salon a short distance away with a man who has spent a lifetime dressing the wives of le premier cru. Pierre Bergé never actually had pins in his mouth himself, you understand – that was his lover and partner, Yves Saint Laurent. But Bergé was the cool maitre d’ who kept La Maison YSL running on castors while the maestro was in the back, agonising over his sketchpad.

“Fashion is not an art,” says Bergé, “but it takes an artist to make fashion.” The 84-year-old unburdens himself of this apothegm with the foxy charm of the late French actor Charles Boyer. He is wearing a dark brown suit by Anderson & Sheppard, the Savile Row cutters where he has been going for 30 years, with the discreet blazon of the Légion d’honneur in his bespoke lapel. As for the book-lined salon, we are surrounded by his “jardin secret”, he exhales raptly: the most priceless and exquisite library in private hands, grown from 1,600 vanishingly rare and hysterically hard-to-find books and manuscripts.

Bergé has decided to part with his beautiful specimens and the auctioneers handling the sale have put an estimate of almost £30 million on them, making this perhaps the most valuable collection ever to come to market. It includes early editions of books which are cornerstones of western civilisation: a first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions printed in Strasbourg in 1470 and estimated at up to £140,000; Dante’s Divine Comedy from 1487; Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies printed in London in 1664. Coddled by gloved flunkies in dehumidified rooms, these volumes have been cherished with the same hushed attention that Saint Laurent and Bergé once lavished on Parisian ladies of a certain age.

Together, Bergé and I admire a heavily worked manuscript of The Sentimental Education by his favourite, Flaubert, published in 1870 and valued at up to £420,000. Naturally, he also has a copy of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary: it has the author’s handwritten dedication to Victor Hugo on the flyleaf. He adores connections like these. He has a volume by Baudelaire dedicated to Flaubert, and his copy of Treasure Island (1883) is not only a first edition, but a present from Robert Louis Stevenson to a friend who suggested the character of Long John Silver.

The eminence grise of the rag trade shows me an illustrated copy of The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe. “I don’t like Poe so much, but this was translated (into French) by the great Mallarmé and the art is by Manet,” he says. Briefly released from a vitrine for our delectation are the fragile, handwritten notes for the Marquis de Sade’s last erotic novel (all that survived the fastidious bonfire lit by the Marquis’s scandalised son). These provocative jottings, composed on paper as dry as the leaves of an old cigar, could set you back £280,000. In addition, la Bibliothèque de Pierre Bergé boasts super-rare early copies of classics by Cervantes, Joyce, Bronte, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and more. They were acquired by Bergé himself and “his agents”, to a strict formula that only books by authors he admired were admitted.

It was literature that gave the young Bergé his lucky break, although this good fortune was at first well disguised. On his first day in Paris, as he was strolling the Champs-Elysées, a Surrealist poet called Jacques Prévert fell from a window and landed on top of him. A winded Bergé chose to see this defenestration as an augury that the French capital had been waiting for him. He embarked on a career in antique books, truffling for overlooked treasures among the bouquinistes, the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine. In the brilliant young tailor Yves Saint Laurent, he recognised another man with an eye for a silver lining. “Christian Dior fired him, and on the same day, he told me we will set up our own business, the house of Yves Saint Laurent.”

Before long, the pair were dressing the screen goddess Catherine Deneuve. The spouses, and mistresses, of the rulers of the Fifth Republic soon followed. Twice a year, in readiness for YSL collections, the designer and his major domo repaired to their villa in Marrakech. They had another home redecorated to a theme of Proust’s À la recherché du temps perdu, the one literary interest they had in common. “It was the only book he ever read,” says Bergé. “Of course, it is a very long book.”

The couple amassed an art collection to excite the salivary glands of gallery directors and oligarchs, including works by Matisse, Cezanne and Klimt. The anguished genius and his suave helpmeet, walled in by Old Masters and first folios – it recalls A Rebours, Joris-Karl Huysmans’s great novel of decadence, of which Bergé naturally owns a highly covetable first edition. The pictures were sold after Saint Laurent’s death in 2008, fetching more than £240m. When asked if he would miss them, Bergé replied, “Everyone dreams of attending their own funeral. I am going to attend the funeral of my collection.” “It must have been an exquisite life,” I suggest. But Bergé hasn’t devoted himself to the luxe, calme et volupté [luxury, peace and pleasure: Baudelaire] of the super-rich without developing a keen nose for how fashions change, swiftly and fatally. “I don’t care to look back,” he says insouciantly.

Bergé claims that Saint Laurent’s great insight was to remove couture from chic restaurants and fashionable apartments and take it “to the street”. The fashion house “empowered” women by putting them in men’s tailoring, in the broad-shouldered shape of the marvellously franglais le smoking. The stress of bringing YSL’s creations before the public and the fashion press took its toll. The couple’s intimate relationship ended in 1976, though they remained friends and business partners.

Today, haute couture is finished, snorts Bergé at his most gallic, no more than a licence to flog scent and handbags, and a pastime for bored supermodels and cashiered pop stars. Only in France, perhaps, could a man with his profile have been a fundraiser for those well-groomed socialists, François Mitterand and Ségolène Royal. I invite Bergé to run a couturier’s tape measure over our own ruling elite. He approves of David Cameron’s holiday wardrobe, but he is not an admirer of the prime minister. He says of Jeremy Corbyn: “I like him. He is a dreamer – and without dreams you have nothing.” But as he claps eyes on a picture of the Labour leader in shorts and dark ankle socks, he shudders almost imperceptibly, like a sequin shaken by a distant Métro.

Our tête-à-tête at an end, Bergé musters his entourage of stubbled younger men who are dressed in autumnal tones. They’re going on to a party. “On y va!” he instructs, leaning dapperly on a cane. La Bibliothèque de Pierre Bergé auctioned at Sotheby’s, Paris, on 11 December 2015. His interview with Stephen Smith appears on BBC Newsnight on a following post.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Independent Working Woman as Deviant in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1867