#heian jidai

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Small sketches of Japanese kimono spanning from the Nara period to the Sengoku period. References come from the Kyoto Costume Museum.

Kimono history is something I love, so this was fun to make and study.

(2024)

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moshimo Tokugawa Ieyasu ga Sori Daijin ni Nattara (2024)

The Covid outbreak in 2020 caused the death of Japan's Prime Minister and the greatest leaders from Japan's past are brought back to life through AI holograms to form a new cabinet to run the country.

Chaos ensues as the key historical figures from Heian Period to Sengoki Jidai like Tokugawa Ieyasu, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Oda Nobunaga till Boshin War once again fight for control.

youtube

A comedy with a lineup of interesting characters and casts. Always been a fan of time travel genre so I am looking forward to this!

#Moshimo Tokugawa Ieyasu ga Sori Daijin ni Nattara#moshi toku#minami hamabe#hamabe minami#tokugawa ieyasu#toyotomi hideyoshi#oda nobunaga#japanese movie#j movie#jmovie#japan#sengoku jidai#heian period#boshin war

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is there big good x big bad yaoi in the new kny opening

#i love the evil guy btw he just decided to be a c slur back in heian jidai and has been picking fights with children ever since#all while looking severely constipated. awesome dude#but i can't stand the sasuke guy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

❝You want me to be a Goddess? Mmm, no. I refuse. Sorry. I don't care about destiny.❞

*with verses in Genshin Impact, InuYasha, Spirited Away, Fire Emblem Fates, YYH

Fandomless RP* OC Kitsune beloved by Jess. Carrd. personals/minors do not reblog. Minors/personals do not interact.

#『sp.』a shy、bouncy、curious kitsune.#『ooc』speaks the tired human.#inuyasha rp#spirited away rp#sengoku jidai rp#bakumatsu rp#heian era rp#anime rp#fire emblem rp#fandomless oc rp#fantasy rp#magic rp

0 notes

Photo

Período Sengoku

El período Sengoku (Sengoku Jidai, 1467-1568), también conocido como el “período de los Estados en guerra”, fue una época violenta y turbulenta de la historia japonesa en la que señores feudales, también llamados daimio (daimyo), luchaban enconadamente por el dominio de Japón. Esta época se encuadra en el período Muromachi (Muromachi Jidai, 1333-1573) de la historia medieval japonesa, cuando la capital del shogunato Ashikaga se encontraba en el distrito de Muromachi, en Heian-kyo (Kioto). Los orígenes del periodo Sengoku se remontan a la guerra de Onin (1467-1477), que destruyó Heian-kyo. Los enfrentamientos que se produjeron a lo largo del próximo siglo acabarían reduciendo el número de daimios a solamente unos cientos mientras Japón se dividía en numerosos señoríos. Al final, uno de estos señores de la guerra se alzaría por encima de todos sus enemigos y sentó las bases para la unificación de Japón a partir de 1568: Oda Nobunaga.

Sigue leyendo...

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aoi Matsuri 葵祭

This festival is one of the 3 Great Festivals of Kyoto. I was quite lucky as the year I visited was the first time in 3 years since COVID that they'd held the event.

The name refers to the Hollyhock plant. The origins are that back in the 500s there were a series of plagues and other natural disasters that struck the city. An oracle was done that linked them to the wrath of the kami at the Kamo Shrines (Kamigamo & Shimogamo). In order to pacify the kami, the emperor partook in several acts, including sending horses and elaborately decorated things to the shrines.

It's essentially been repeated ever since.

According to Wikipedia:

"The procession is led by the Imperial Messenger. Following the imperial messenger are: two oxcarts, four cows, thirty-six horses, and six hundred people. The six hundred people are all wearing traditional dress of Heian nobles (ōmiyabito), while the oxcart (gissha) is adorned with artificial wisteria flowers"

The center focus of the festival is the Saiō (斎王) who historically was a female member of the imperial household, sent to represent the Emperor. Nowadays she is played by an unmarried woman. The other key player is the imperial messenger.

Interestingly enough the plants used during the festival are rarely Hollyhock, and instead Katsura leaves and other plants act as stand ins. Both this festival and the Jidai Matsuri festival involve people dressing up in period clothes which was quite entertaining to watch.

One of the fun things about the festival is that it falls on my birthday, so it was really fun to be able to celebrate it during that day :D

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Demon Slayer Timeline, part 01

[Lots of spoilers for obvious reasons] The Demon Slayer Timeline is actually, a really long one. While it does not follow the totality of the Japanese history, it follows closely the beginning and falling of the Samurai era. While the main plot takes place in the Taisho Era [1912-1924], Sumiyoshi Kamado and Yoriichi Tsugikuni take us to the Sengoku Jidai [1467-1563], and Muzan to the Heian Era [794-1192] ( Muzan drop that skincare routine). But let us start from the beginning.

Muzan says that he was turned into a demon by a doctor in the Heian Era.

The Heian Era [c.794-1192] is today regarded as one of the times of highest culture, even though it was one of the [many] times of political and military conflicts. After conflits between the imperial court and the Buddhist sects that were starting to have way too much power the capital was moved from Nara to Heian-kyo - today known as Kyoto - to be safely way. That said, it also started a religious reform with the introduction of new kinds of Buddhism. [with less interest in power obviously, but still kept at a safe distance of the court] Tendai Buddhism and the Pure land Buddhism would start gain attention during this times and the temples would open their doors to every one of every type of social class [as we can see with Gyomei Himejima, the Rock Hashira that was a blind man that took care of orphan children in a Buddhist temple]. The temples stop having political power, but they also stop having financial aid. So, to survive they had to start exploring the natural resources of their territories. It's not going to take long before the temples start to argue about say territories, and to protect them, they will start to train the farmers that inhabited it, creating what would become a military class. In 'other hand, in the capital we see a court that is way to centred on herself. The Fujiwara clan was the family with the biggest amount of power. Fujiwara women would marry into the Imperial family in a what could be called genetic colonialization. In the 10th century the Imperial household could not function without the Fujiwara one, starting the tradition were until they reached adulthood the emperor had a Fujiwara regent, so basically it was the Fujiwara that ruled not the Imperial family. But, after 170 years, in 1068 an emperor without a Fujiwara mother sits on the chrysanthemum throne. Go-Sanjo would start to eradicate the Fujiwara by abdicating, leaving the throne to his already adult son. And the same would happen for the next 2 emperors. But by starting to cut ties with the Fujiwara, the imperial family cut off his right arm, and the arm that had the military power, nonetheless. Japanese had a natural border against enemies, that also meant that they did not have to where to expand their natural territory. So, without new territories to be conquered, the only solution was to start fighting each other for the lands that existed. The families that lived far from the capital were old families that knew their territories like the palm of their hands. With the crescent responsibilities of safeguarding their territories, like with the temples, this Shoen [local provinces] start to train their inhabitants [just like the temples]. We start to see the conquest of territories, and when a clan was defeated, the warriors would start to serve the winning clan. It's the birth of the Samurai Code. In the 12th century we start to have clans that are ready to go against the imperial court. In 1160 we have the Heiji war, were the Minamoto and Taiga clans are confronting each-other at the capital, and the Taiga family wins, and with entering the court life would become an exact copy of the Fujiwara. The only heir and survivor of the Minamoto clan starts to see the military machine of the Taiga to transform into an aristocratic one wand waits until 1180 to strike back. In 1185 the Minamoto would win the Genpei war staring the 1st ever Shogunate rule.

When Tanjiro goes to the Swordsmith, village, he encounters the mechanical doll made by Kotatsu’s ancestors called “Yoruichii Type Zero” where he goes on saying that that face is familiar to him and Kotatsu says that that technology is from the Sengoku Era.

Then after that we start to see Tanjiro’s flash backs of his ancestor Sumiyoshi Kamado and his encounter with Yoriichi Tsugikuni and all of that is confirmed with the backstory of Upper Moon 01 - Kokushibo.

Now, what was the Sengoku Era? Also known as the “warring states era”, the Sengoku-Jidai [c.1467-1573] was the time where the Japanese archipelago was buried on the total anarchy that was the civil war. So, we have a circa 275 years jump. After the failed rule of the Ashikaga Shogun [Yes because history spoilers, after the Minamoto Shogunate there was more was, more war, and another Shogun], the daimyo [local governors] continue to train their locals to defend their territory. Thanks to the fidelity bonds, the commoners responded to their daimyo, while the daimyo had to respond to the Shogun. Since the Shogun [we don’t even talk about the emperor since he was basically a poppet] no longer protected the daimyos they started to rebel against him saying that he was the first that broke the fidelity law. The commoners, started to learn specific combat techniques - the Kenjutsu, art of the sword - and would develop to what we know call samurai. The word samurai comes from the word “saburau” which means “to serve”, the rising of the samurai class marks the beginning of the feudal era in Japan. At the beginning, these warriors could have two jobs - be warriors and farmers as an example. When Hideyoshi (we will soon talk about him) came to power he required that they choose one or the other, but as long as a samurai remained loyal they were guaranteed a good life. The samurai's weapon of choice was a 2-sword combination. The 1st one, was the combat sword, a long one called (surprise) Katana. The 2nd one was a small curved one called Wakizaki that served to cut one’s stomach (note: important I tell you). Now, while everyone was fighting each other for territory, a man in the middle of the territory started what would soon become the union of Japan. Oda Nobunaga [織田 信長 1534-1582], as the eldest son that everyone thought would not do much. Turns out he collaborated with his uncle to kill his brother, to then kill said uncle. At 25 years old no one was bad mouthing him in Owari anymore. He started then to expand his territories were battle after battle he seemed unstoppable. Then Nobunaga’s troops were defeated for the 1st time, and Akeshi Mitsuhide [明智光秀 1528-1582] would profit this momentarily loss of confidence on Nobunaga to obligate him to commit suicide. But Mitsuhide's victory was short lived since Toyotomi Hideyoshi [豊臣 秀吉 1527-1598], learning what had succeeded rushed to confront Mitsuhide, ending up defeating him. (Man, I love telling everyone this part cause this is what I call plot twist after plot twist! And we aren't finished yet!) Hideyoshi would be de one finishing what Nobunaga started and re-uniting wall the territory under one ruler. But, after Hideyoshi's dead, his son was still a minor (literally a baby). He would go on naming 5 daimyos as regents in case 1 rebelled the other 4 would protect the heir. Still that did not stop Tokugawa Ieyasu [徳川家康 1543-1616] from rebelling. At 1600 Tokugawa would win the legendary Sekigahara battle, and in 1603 he would (not so kindly) ask the emperor for the Shogun title. He would go on to establish the longest Shogunate in Japanese history. So as the saying goes: “Nobunaga oiled the national rice cake, Hideyoshi kneaded the dough and, in the end, Ieyasu at down and gobbled it up”.

Bibliography: CHAPLIN, Danny. 2018- Sengoku Jidai: Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu: the three unifiers of Japan. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Ebook; CLEMENTS, Jonathan. 2017 - A Brief History of Japan: Samurai, Shogun and Zen. The extraordinary story of the land of the rising sun. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing.Ebook; HILLSBOROUGH, Romulus. 2017 - Samurai Assassins: "Dark Murder" and the Meiji restoration, 1853-1868. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. Ebook; MANSON, R.H.P ; CAIGER, J.G. 1997 - A History of Japan. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 1997. Ebook;

#demon slayer#demon slayer history#demonslayerfromhistorytofantasy#demon slayer from history to fantasy#japanese history#history#research#history research#kimetsu no yaiba#kamado tanjiro#muzan kibutsuji#sumiyoshi kamado#yoriichi tsugikuni

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Époque Sengoku

L'époque Sengoku (Sengoku Jidai, 1467-1568), également connue sous le nom de période des États combattants, fut une période turbulente et violente de l'histoire japonaise au cours de laquelle des seigneurs de guerre ou daimyo rivaux se livrèrent une lutte acharnée pour le contrôle du Japon. Cette période s'inscrit dans la période Muromachi (Muromachi Jidai, 1333-1573) de l'histoire médiévale japonaise, lorsque la capitale du shogun Ashikaga était située dans la région Muromachi de Heian-kyō (Kyoto). Le début de l'époque Sengoku fut marqué par la guerre d'Ōnin (1467-1477) qui détruisit Heian-kyō. Les combats qui suivirent au cours du siècle suivant finirent par réduire le nombre de seigneurs de la guerre à quelques centaines, car le pays fut découpé en princes. Finalement, un seigneur de guerre s'éleva au-dessus de tous ses rivaux: Oda Nobunaga, qui mit le Japon sur la voie de l'unification à partir de 1568.

Lire la suite...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Origen y evolución de los samuráis en Japón El surgimiento de los samuráis en el período Heian El origen de los samuráis en Japón se remonta al período Heian (794-1185). Durante este tiempo, el sistema de gobierno se estaba desarrollando y los clanes guerreros comenzaron a tomar un papel más importante en la protección de la nobleza y sus tierras. Los samuráis inicialmente eran guerreros a caballo que servían a los nobles feudales llamados daimyos. La palabra samurái significa "aquellos que sirven", reflejando su función como protectores leales. La consolidación en el período Kamakura Durante el período Kamakura (1185-1333), los samuráis empezaron a consolidarse como una clase social distinta. Bajo el liderazgo del shogunato Kamakura, emergió un gobierno militar que dependía del poder y la lealtad de los samuráis. En esta época, se formalizaron muchos de los códigos éticos y de comportamiento conocidos como el Bushidō, o "Camino del Guerrero". Ascenso y prominencia en el período Muromachi En el período Muromachi (1336-1573), los samuráis se convirtieron en los principales actores políticos y militares. Durante este tiempo, el país experimentó guerras internas conocidas como las Guerras de los Estados Combatientes (Sengoku Jidai), que incrementaron la influencia y el poder de los samuráis. Se destacaron líderes militares como Oda Nobunaga y Toyotomi Hideyoshi, quienes eran de origen samurái. El período Edo: El samurái como burócrata El período Edo (1603-1868) marcó el inicio de un largo período de paz bajo la dinastía Tokugawa. Durante estos años, muchos samuráis adoptaron roles administrativos y se convirtieron en burócratas, mientras que sus habilidades marciales pasaron a un segundo plano. A pesar de la paz, la clase samurái mantuvo una significativa influencia cultural y social en Japón, y los principios del Bushidō seguían siendo altamente valorados. Transformaciones durante la Restauración Meiji La Restauración Meiji en 1868 trajo consigo grandes cambios sociales y políticos. El nuevo gobierno centralizado buscó modernizar Japón siguiendo modelos occidentales, lo que llevó a la disolución del sistema de clases y, en consecuencia, a la desaparición oficial de los samuráis como entidad social. Sin embargo, muchos ex-samuráis encontraron nuevas funciones dentro del aparente sistema militar y gubernamental emergente. Impacto cultural y legado de los samuráis A pesar de su desaparición como clase, el legado de los samuráis ha perdurado en la cultura japonesa. Los valores del Bushidō, como el honor, la lealtad y el sacrificio, continúan siendo ideales importantes en la sociedad japonesa moderna. Además, la literatura, el cine y otros medios de comunicación han perpetuado la imagen de los samuráis, asegurando que su influencia histórica no sea olvidada. Período Heian: Surgimiento inicial de los samuráis como protectores de la nobleza. Período Kamakura: Consolidación y formalización del Bushidō. Período Muromachi: Expansión del poder samurái durante las Guerras de los Estados Combatientes. Período Edo: Los samuráis se convierten en burócratas bajo la dinastía Tokugawa. Restauración Meiji: Modernización y disolución de la clase samurái. La clase samurái: Quiénes eran y su rol en la sociedad Origen y definición de los samuráis Los samuráis fueron una clase militar aristocrática que surgió en Japón durante la Edad Media. Originalmente, la palabra "samurái" significaba "el que sirve", refiriéndose a los guerreros que servían a los nobles y a los poderosos señores feudales conocidos como daimyos. Con el tiempo, la clase samurái se convirtió en una casta guerrera respetada y reconocida en todo el país. Entrenamiento y habilidades de los samuráis El entrenamiento de un samurái comenzaba desde una edad temprana e incluía rigurosas disciplinas tanto físicas como mentales. Dominaban diversas artes marciales, entre ellas el kendo (esgrima), el jiu-jitsu (combate cuerpo a cuerpo) y el kyudo (arquería). Además de sus habilidades marciales,

los samuráis también eran instruidos en aspectos culturales y filosóficos, incluyendo la poesía, la caligrafía y el código de conducta conocido como bushido. El código de honor: Bushido El bushido, que significa "el camino del guerrero", era el código ético que regía la vida de los samuráis. Este código enfatizaba valores como la lealtad, el honor y la valentía. El bushido no solo dictaba cómo debían comportarse en la batalla, sino también cómo debían vivir sus vidas cotidianas, poniendo un alto valor en la integridad y el respeto. Influencia en la sociedad feudal La influencia de los samuráis en la sociedad feudal japonesa fue significativa. Actuaron como la columna vertebral militar del sistema feudal, protegiendo las tierras y sirviendo a los daimyos. Además, su estricto código de honor y ética influenció profundamente la cultura y las prácticas sociales de la época, estableciendo estándares altos de conducta que fueron seguidos por otras clases sociales. La evolución del rol samurái Durante el período Edo (1603-1868), el rol de los samuráis empezó a cambiar. Con la unificación de Japón y la relativa paz bajo el shogunato Tokugawa, muchos samuráis encontraron que sus habilidades militares eran menos necesarias. Así, se convirtieron en burócratas y administradores, aplicando su riguroso entrenamiento y disciplina a la gestión civil y gubernamental. Impacto cultural y legado El legado de los samuráis perdura en la cultura japonesa moderna. Sus valores de disciplina, honor y lealtad continúan siendo venerados y se reflejan en prácticas empresariales, artes marciales y otras áreas de la vida japonesa. Los samuráis no solo fueron guerreros hábiles, sino también figuras que ayudaron a moldear la identidad cultural y social del Japón. Código de honor: El Bushido y su significado para los samuráis El Bushido es, en esencia, el código de honor y ética que regía la vida de los samuráis en el Japón feudal. Este término, que se traduce como "el camino del guerrero", comprende una serie de principios que guiaban tanto la conducta en la batalla como en la vida cotidiana de estos guerreros. Los samuráis, lejos de ser simplemente soldados, eran considerados la élite de la sociedad japonesa. El Bushido no solo les exigía habilidades en combate, sino también un comportamiento ético que abarcaba la lealtad, el honor y la justicia. El deshonor podría llevar a un samurái a cometer seppuku, un suicidio ritual, para preservar su nombre y el de su familia. Principios del Bushido Gi (Justicia): Un samurái debía ser recto en su actuar, tomando decisiones justas sin desviarse por intereses personales. Yu (Valor): El coraje era fundamental. No se trataba solo de valentía en la batalla, sino de enfrentar las dificultades de la vida con una actitud fuerte y decidida. Jin (Compasión): A pesar de ser guerreros, los samuráis debían mostrar compasión y ser generosos, utilizando su poder para proteger a los débiles. Rei (Respeto): El respeto y la cortesía eran esenciales. Los samuráis debían tratar con dignidad a todas las personas, sin importar su estatus social. Makoto (Honestidad y Sinceridad): La palabra de un samurái era su vínculo. Mentir o engañar iba en contra de su naturaleza. Meiyo (Honor): El honor personal y familiar era de suma importancia. Mantener una reputación honorable era crucial para un samurái. Chugi (Lealtad): La lealtad hacia su señor y compañeros era fundamental. Un samurái era conocido por su fidelidad inquebrantable. El Bushido también influía en aspectos más mundanos de la vida de un samurái, como su dedicación al estudio, la poesía y el arte. La educación era muy valorada, y los samuráis aprendían no solo sobre tácticas militares, sino también sobre filosofía y cultura para ser líderes completos y equilibrados. A través de este código de honor, los samuráis mantenían una disciplina estricta y un sentido profundo del deber. A menudo, se les veía como el ejemplo perfecto del hombre ideal en la sociedad japonesa, combinando la fuerza física con una fuerte moralidad.

El impacto del Bushido fue tan profundo que su influencia se siente incluso en la sociedad japonesa moderna. Los principios de honor, lealtad y dedicación siguen siendo valores fundamentales en la cultura y ética del Japón contemporáneo. El entrenamiento y las habilidades de los samuráis Disciplina y Código de Honor El entrenamiento de los samuráis estaba profundamente arraigado en un estricto código de honor, conocido como Bushido. Este código dictaba no solo el comportamiento en el campo de batalla, sino también en la vida diaria. Los samuráis debían demostrar una disciplina excepcional y un compromiso inquebrantable con los principios de lealtad, coraje y respeto. Artes Marciales y Dominio de la Espada Una de las habilidades más reconocibles de los samuráis era su destreza en las artes marciales. El dominio de la espada, específicamente la katana, era una parte fundamental de su entrenamiento. A lo largo de años de práctica rigurosa, los samuráis desarrollaban técnicas sofisticadas de esgrima y combatían en duelos para perfeccionar su habilidad. Entrenamiento Mental y Espiritual El entrenamiento de los samuráis no se limitaba a lo físico. El desarrollo mental y espiritual era igualmente importante. Practicaban la meditación Zen para lograr un estado de equilibrio y calma interior, lo cual era crucial para mantener la compostura y la toma de decisiones en situaciones de alta tensión. Estrategia y Tácticas Militares Además de sus habilidades físicas y espirituales, los samuráis eran conocidos por su conocimiento en estrategia y tácticas militares. Estudiaban textos clásicos sobre guerra y filosofía, desarrollando la capacidad de pensar críticamente y planificar detalladamente sus movimientos en el campo de batalla. Manejo de Armas Diversas Si bien la katana es el arma más emblemática de los samuráis, su entrenamiento incluía el manejo de una variedad de armas. Esto incluía lanzas (yari), arcos (yumi) y armas de fuego cuando estas llegaron a Japón. Esta versatilidad les permitía adaptarse a diferentes escenarios de combate. Equitación y Artes Ecuestres La equitación era una habilidad esencial para los samuráis. El manejo hábil de caballos les permitía moverse rápidamente en el campo de batalla, facilitando tácticas de ataque y retirada. Además, desarrollaban técnicas avanzadas de combate a caballo, haciendo uso del arco y la lanza mientras cabalgaban. La vestimenta samurái: Armadura y armas tradicionales Armadura samurái: Protección y simbolismo La armadura samurái era mucho más que una simple protección en combate. Conocida como Yoroi, esta pieza de equipamiento estaba diseñada para proporcionar una combinación de movilidad y defensa. Estaba compuesta principalmente por placas de hierro y cuero lacado, unidas por cordones de seda, formando un conjunto flexible y resistente. Componentes de la armadura samurái Cada parte de la armadura tenía su propio propósito y significado. La cabecera o kabuto protegía la cabeza y frecuentemente incluía una máscara con rasgos feroces para intimidar al enemigo. El cuerpo era cubierto por la dō, una coraza que protegía el torso y estaba diseñada para desviar golpes y flechas. Los brazos y las piernas estaban protegidos por los kote y suneate respectivamente, que ofrecían seguridad adicional sin limitar los movimientos del guerrero. Armas tradicionales: La katana La katana es posiblemente la más reconocida de las armas samurái. Caracterizada por su hoja curva y afilada, esta espada no solo era efectiva en combate, sino que también simbolizaba el alma del samurái. Su elaboración era un proceso complejo y meticuloso, reflejando el estatus y la calidad de su portador. El arco y la flecha: Armas a distancia Mientras que la katana es famosa, el Yumi (arco) y las flechas también eran elementos cruciales en el arsenal del samurái. El Yumi era notablemente largo, lo que permitía disparar con gran precisión y potencia desde distancias considerables. El uso del arco requería una gran habilidad y era una parte integral del entrenamiento samurái.

La lanza Yari: Versatilidad en combate Otra arma fundamental era la Yari, una lanza que ofrecía gran versatilidad en el combate cuerpo a cuerpo. Poseía una larga hoja afilada montada en un eje que variaba en longitud, permitiendo realizar ataques rápidos y efectivos. La Yari podía ser usada tanto desde el suelo como desde la posición elevada en un caballo, aumentando su utilidad en diferentes escenarios de batalla. El Wakizashi y el Tanto: Armas secundarias Además de la katana, los samuráis llevaban el Wakizashi y el Tanto como armas secundarias. El Wakizashi era una espada más corta, ideal para combates en espacios reducidos. Por otro lado, el Tanto, un pequeño cuchillo, cumplía múltiples funciones tanto en el combate como en la vida diaria del samurái. Importancia cultural de la vestimenta y las armas La vestimenta y las armas tradicionales de los samuráis no solo definían sus capacidades en el campo de batalla, sino que también eran un símbolo de su honor, disciplina y estatus social. Cada pieza, desde la armadura hasta las armas, era diseñada y elaborada con un cuidado extremo, reflejando la rica herencia cultural y las intrincadas tradiciones del Japón feudal. La vida cotidiana de los samuráis: De la guerra a la paz Entrenamiento y disciplina militar La vida cotidiana de los samuráis estaba profundamente enraizada en un riguroso régimen de entrenamiento y disciplina. Desde temprana edad, los futuros guerreros eran instruidos en el arte del combate con espadas, arcos y otras armas tradicionales. Este entrenamiento no solo fortalecía su físico, sino que también cultivaba una mentalidad férrea y determinada necesaria en el campo de batalla. El código de ética conocido como Bushido, o "el camino del guerrero", guiaba cada aspecto de la vida de los samuráis. El Bushido enfatizaba valores como la lealtad, el honor y el sacrificio. Cumplir con este código era esencial, ya que cualquier desvío podía resultar en la deshonra familiar y personal, a veces requiriendo el seppuku, o suicidio ritual, para restaurar el honor perdido. Con la llegada de la paz en el período Edo, el rol de los samuráis comenzó a transformarse. Además de sus deberes militares, empezaron a asumir responsabilidades administrativas y burocráticas. Muchos se convirtieron en funcionarios de gobierno, gestionando tierras y recursos, asegurándose de que las leyes y las políticas del shogunato se implementaran correctamente. Educación y cultura En tiempos de paz, los samuráis también se dedicaban a la educación y al cultivo personal. Estudiaban literatura, poesía y filosofía, incluidos los clásicos chinos y las enseñanzas del zen. La caligrafía y la pintura eran otras formas de expresión artística que muchos samuráis practicaban, demostrando que el camino del guerrero también pasaba por el cultivo del espíritu y la mente. [aib_post_related url='/consejos-para-ganar-elasticidad-en-las-piernas/' title='Consejos para ganar elasticidad en las piernas' relatedtext='Quizás también te interese:'] Los samuráis valoraban profundamente la vida familiar y las obligaciones que conllevaba. El hogar samurái era una estructura jerárquica donde el respeto y la obediencia eran fundamentales. Los matrimonios, comúnmente arreglados, se basaban en la consolidación de alianzas y el fortalecimiento de las posiciones sociales. La educación de los hijos también era una prioridad, asegurando que las futuras generaciones siguieran el camino samurái. Agricultura y economía Muchos samuráis participaron en actividades agrícolas y económicas para complementar sus ingresos. La tierra era una fuente vital de sustento, y la gestión eficiente de estas propiedades era crucial para mantener el estatus y la independencia económica. En algunos casos, incluso supervisaban la producción de bienes artesanales o comerciales, ayudando a diversificar las fuentes de ingresos durante tiempos de paz. Las relaciones sociales eran una parte integral de la vida cotidiana de los samuráis. Regularmente participaban

en ceremonias de té, festivales y otros eventos comunitarios que fortalecían los lazos sociales y reafirmaban su estatus en la sociedad. Estas interacciones no solo eran oportunidades para mostrar habilidades y refinamiento personal, sino también para consolidar redes de apoyo y lealtades mutuas. La influencia de los samuráis en la cultura japonesa El legado histórico de los samuráis Los samuráis, conocidos como la clase guerrera de Japón, han dejado una huella imborrable en la historia y cultura del país. Surgiendo en el período Heian, su influencia se extendió durante siglos hasta la Restauración Meiji en el siglo XIX. Estos guerreros no solo fueron maestros en el arte de la guerra, sino también mecenas de la cultura y promotores de valores como el honor, la lealtad y la disciplina. La filosofía del Bushido o "Camino del Guerrero" es uno de los legados más significativos de los samuráis. Este código dictaba la conducta, los deberes y el estilo de vida de los samuráis, abarcando virtudes como el coraje, la compasión y la honestidad. A través del Bushido, los samuráis promovieron una ética que sigue resonando en la sociedad japonesa contemporánea. Impacto en el arte y la literatura La rica tradición de los samuráis también se refleja en el arte y la literatura japonesa. Obras literarias como "El cuento de los Heike" y múltiples haikus fueron inspirados por la vida y hazañas de estos guerreros. Pinturas y grabados históricos también destacan la figura del samurái, representando escenas de batallas épicas y retratos de famosos guerreros. Influencia en la educación y formación Durante el dominio de los samuráis, la educación y la formación física eran aspectos cruciales. El Kendo, el arte de la esgrima con sables, y el Kyudo, la arquería tradicional japonesa, son disciplinas que se originaron bajo la tutela samurái. Estas prácticas no solo entrenaban el cuerpo, sino que también cultivaban la mente, reforzando la importancia de la autodisciplina y la perseverancia. La influencia de los samuráis se extiende también a la arquitectura y el diseño urbano. Los castillos japoneses, como el Castillo de Himeji, son ejemplos emblemáticos de la arquitectura samurái. Estas fortalezas no solo funcionaban como residencias, sino que también simbolizaban el poder y la autoridad de sus habitantes. Además, la disposición de las aldeas y ciudades muchas veces era planificada para optimizar defensas y recursos estratégicos. En la actualidad, la figura del samurái continúa siendo una fuente inagotable de inspiración en la cultura popular. Películas, series de televisión, manga y videojuegos a menudo retratan la vida de estos guerreros, manteniendo vivo su legado y presentándolo a nuevas generaciones tanto en Japón como en todo el mundo. La influencia de los samuráis en la cultura japonesa es vasta y multifacética. A través de su código ético, sus contribuciones al arte y la literatura, su impacto en la educación y formación, su influencia en la arquitectura y su presencia en la cultura pop, los samuráis han dejado una marca indeleble que sigue perdurando hasta nuestros días. El legado de los samuráis en la historia contemporánea El legado de los samuráis, guerreros emblemáticos del Japón feudal, ha dejado una huella imborrable en la historia contemporánea de Japón y más allá. Estos guerreros no solo desempeñaron un papel crucial en la formación de la sociedad japonesa, sino que también han influido en diversos aspectos de la cultura moderna. Influencia en las artes marciales Las artes marciales modernas, como el judo, el kendo y el aikido, tienen sus raíces en las técnicas de combate que los samuráis utilizaban. Estos métodos de lucha no solo se centraban en la habilidad física, sino que también promovían el desarrollo del carácter y la disciplina, valores que siguen siendo fundamentales en las artes marciales de hoy en día. Ética del bushido El código de honor samurái, conocido como bushido, ha sido adaptado y venerado como una filosofía de vida en la era contemporánea.

Principios como la lealtad, el honor y el sacrificio personal han trascendido épocas y continúan inspirando tanto a líderes empresariales como a individuos en su vida diaria. Papel en la cultura popular Los samuráis han dejado una marca indeleble en la cultura popular global. Desde películas como "Los Siete Samuráis" hasta videojuegos y series de televisión, la figura del samurái se ha convertido en un símbolo de valentía y nobleza. Este fenómeno ha ayudado a popularizar aún más la cultura japonesa en todo el mundo. Influencia en la moda y el diseño El legado samurái también se extiende al mundo de la moda y el diseño. Elementos tradicionales como la katana y la armadura samurái han sido reinterpretados en tanto alta costura como en ropa casual. Dichos elementos se pueden ver en pasarelas internacionales y en marcas de moda de renombre. Educación y liderazgo En el ámbito educativo y corporativo, muchos principios del entrenamiento samurái se han integrado en programas de liderazgo y desarrollo personal. Ejercicios de meditación y prácticas como el Kendo son utilizados para enseñar concentración, autocontrol y determinación. Play on YouTube El legado de los samuráis también se refleja en las innovaciones tecnológicas de Japón. El país ha liderado avances en robótica e inteligencia artificial, campos que destacan por su precisión y dedicación, valores profundamente enraizados en la ética samurái.

0 notes

Text

Time period in japan

Currently researching on the The Kamakura period (鎌倉時代, Kamakura jidai, 1185–1333) and The Heian period (平安時代, Heian jidai 794 to 1185)

0 notes

Text

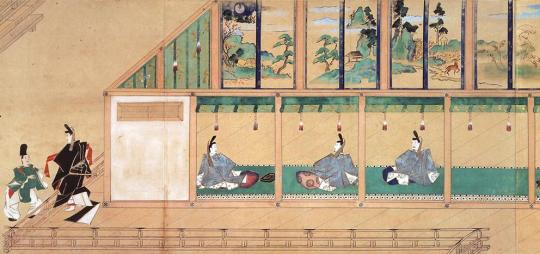

Junihitoe wo Kita Akuma / The Devil Wears Junihitoe Kimono (2020)

Rai (Kentaro Ito) struggles to get a job and got dumped by his girlfriend who thinks she can't grow if she stays with him. The fact that his younger brother is better looking, smarter and good in everything that he is not, further adds to his insecurities.

Rai works part time at an exhibition for the "Tale of Genji", where he learns the history. He realises everyone knows about Hikaru Genji, the handsome and intelligent man, who charms the ladies of the court but no one knows about his older brother, Ninomiya.

Ninomiya is the son of the Emperor's first wife, but he is less appealing and less intelligent than Hikaru. And the Emperor loves Ninomiya and his mother, the concubine, more than his own wife, Nyogo Kokiden (Ayaka Miyoshi) which made her cold and bitter.

Unlike Hikaru, Ninomiya is not good with words and is not a womanizer. He is too honest and good natured for his own good, which frustrates his mother, Kokiden, who knows her son can't survive the harsh world, which resonates with Rai.

One night, on his way home, Rai learns about his younger brother's achievement and a celebration was in order. Rai decides to wander around to avoid returning home, when he encounters a mysterious light which transports him back in time and meet Kokiden.

youtube

It's meant to be light-hearted which started off as a comedy but along the way the story gets serious as Rai got entrenched into the political intricacies of the court which changes Rai, who finds a sense of belonging here and doesn't want to return to the present.

Kentaro Ito and Ayaka Miyoshi are so good in their roles. I've never seen Kentaro Ito expressing all forms of emotions in one movie, that I got teary eyed watching, relating to his life struggles that you could feel his pain. He just wants to be loved for who he is.

Ayaka Miyoshi plays a complex character who seems cold and ruthless on the outside that people called her the devil, when she is just protective and ambitious. She knows that being too honest will get you killed and has to be the devil to defeat another devil.

Kentaro Ito's character learns to be more forgiving and accepting of himself while Ayaka Miyoshi's character learns to be more human, learning that others have feelings too, and how powerful the right words can be that they can turn rivals into allies without a fight.

When I first read Japanese history, I am attracted to Sengoku Jidai, the warring times between Samurai but over time, I grew interested in Heian Period, long before the Samurai reign supreme over Japan. I find the culture and music of the time to be quite intriguing.

#junihitoe ko kita akuma#the devil wears junihitoe kimono#十二単衣を着た悪魔#kentaro ito#ayaka miyoshi#ito kentaro#miyoshi ayaka#japanese movie#j movie#japanese film#japanese drama#j drama#jdrama#dorama#japan#asian drama#asia movie#historical fiction#tale of genji#my recommendations#my review#heian period

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kannin: Keep Going!

Theme for 2023 is Kannin, keep going!

With my brother-in-arms Pedro, and a few others, we had the chance to share lunch with Sensei. During this time, he said, “this year, the important is Kannin, keep going.” (1) There are several meanings to Kannin. Kannin refers to a period in Japanese history at the beginning of the 11th century (1017-1021). (2) Then during the Heian Jidai, it became a generic term referring to the officials…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

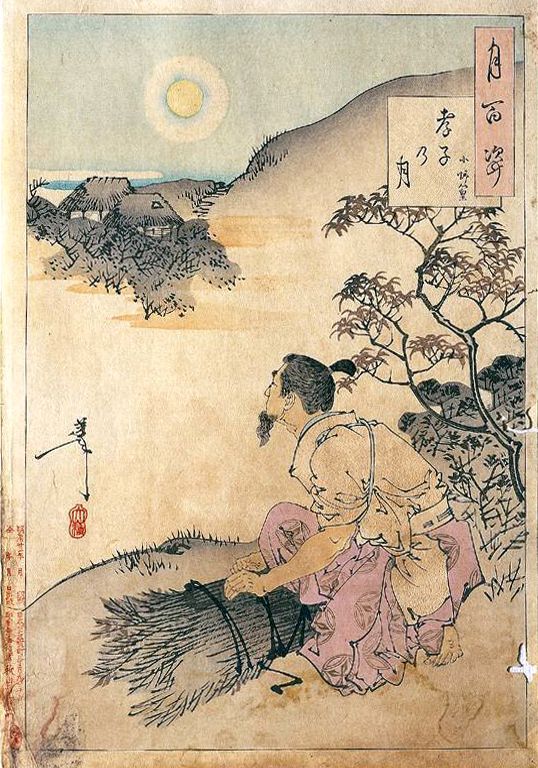

Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集

ou Kokinshū 古今集 - 1ère Anthologie de waka 和歌.

VOYAGES / Livre 9

Ono no Takamura par Kikuchi Yōsai 菊池容斎 (1781 - 1878).

Poème 407 de Ono no Takamura 小野篁 ou Sangi no Takamura 参議篁 (802-853) - savant et poète.

わたの原 「和田の原」 / 八十島かけて / こぎ出ぬと / 人には告げよ / あまのつり舟 Wata no hara / Yasoshima kakete / Kogi idenu to / Hito ni wa tsugeyo / Ama no tsuri bune

Illustration du poème 407 : Ono no Takamura (Sangi Takamura) de Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760 - 1849).

Vers les octante îles de la vaste plaine marine je m'en vais voguant va-t'en le lui annoncer ô la barque du pêcheur

Traduction : René Sieffert

Illustration du poème 407 de Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1797-1861).

Ce poème, dans le Kokinshū 古今集, est présenté comme suit : "Alors qu'il avait été exilé dans la province d'Oki-no-kuni 隠岐国, envoyé chez quelqu'un qui demeurait en la ville pour lui annoncer qu'il s'embarquait". Les "huit fois dix îles" est une des multiples façons de désigner l'archipel. Les nombres huit, quatre-vingt, huit cent, huit mille, huit myriades ou huit cent mille s'appliquent à des choses ou des êtres trop nombreux pour être comptés, ou, à la limite, en nombre indéfini, tels les kami 神, les dieux shintō 神道 qui sont ya.o.yorozu 八百万, "huit cents myriades" . Bien que bon nombre d'anecdotes rapportent des traits d'esprit de Takamura, douze seulement de ses poèmes figurent dans les chokusen-shū 勅撰集 . Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集 ou Kokinshū 古今集 , IX, 407. "De 100 poètes un poème" René Sieffert.

Histoire : Ono no Takamura a été haut fonctionnaire à la cour de l'empereur Saga tennō (52) 嵯峨天皇 (786 - 842 r. 809 - 823) au IXe siècle. Lettré célèbre, en particulier pour ses compositions en chinois, avait été, en 829, adjoint à Fujiwara no Tsunetsugu 藤原常嗣 (796-840), chef de l'ambassade qui devait se rendre en Chine ; comme il s'était dérobé en se prétendant malade, on l'avait exilé dans l'archipel d'Oki-shotō 隠岐諸島. Rentré en grâce, il devint par la suite Conseiller du troisième rang de Cour.

Six de ses waka ont été inclus dans l'anthologie impériale Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集 ou Kokinshū 古今集 et l'un de ses poèmes a été inclus dans l'Ogura Hyakunin Isshu 小倉百人一首 (11).

Légende : Takamura a également souvent été loué comme modèle de piété filiale et de générosité. Il partageait ses allocations avec des parents et des amis qui étaient plus dans le besoin que lui et montrait un grand respect pour ses parents. L'iconographie pourrait également faire référence à Ceng Shen, un disciple important de Confucius, à qui est attribuée la compilation des 24 parangons de la piété filiale. La légende raconte que Ceng cueillait des broussailles dans la forêt quand il eut la prémonition que sa mère avait besoin de lui. Il se dépêcha de rentrer chez lui pour constater qu'elle lui avait tellement manqué qu'elle s'était mordue le doigt avec contrariété.

Illustration : "100 aspects of the moon - Moon of the filial son (Koshi no tsuki) de Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1839 - 1892)

#poem#poetry#japan#kokin wakashu#kokinshu#waka#tanka#heian jidai#ono no takamura#kikuchi yosai#katsushika hokusai#utagawa kuniyosehi#tsukioka yoshitoshi#anthologie de poésie#poème#japon

393 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tomoe Gozen (巴 御前) (1157–1247); was a late twelfth-century female samurai warrior known for her bravery and strength. She is believed to have fought in and survived the Genpei War. She was also the concubine of Minamoto no Yoshinaka. According to one historical account, Tomoe was beautiful, with white skin, long hair, and charming features. She was also a remarkably strong archer, and as a swordswoman, she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot. She handled unbroken horses with superb skill; she rode unscathed down perilous descents. Whenever a battle was imminent, Yoshinaka sent her out as his first captain, equipped with strong armour, an oversized sword, and a mighty bow; and she performed more deeds of valour than any of his other warriors (The Tale of the Heike).

657 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mononogu shouzoku is a formal wear worn until the late Heian period. Its notable characteristic include hire ( cloth sash hung from the shoulders ) and kuntai ( cloth sash hung from the waist ). I changed the uwagi pattern because the real one was really hard to draw o)-( I also added base pattern on the karaginu. The other elements are drawn with reference. Reference: kimonohistory.fuyulink.co.uk/c… Holbein watercolor on Reeves paper. Thank God I only have one paper left. Absolutely will not repurchase the paper ever again, it gets teared easily o)-( Art (c) Hachiretsu

#junihitoe#juunihitoe#karaginumo#heian#heianera#heian era#karaginu mo#heian period#heian jidai#hachiretsu#watercolor#traditional art#traditional work#mononogu shouzoku#itsutsuginu karaginu mo#deviantart

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Époque de Nara

L'Époque de Nara (Nara Jidai) de l'ancien Japon (710-794), appelée ainsi parce que pendant la majeure partie de cette période, la capitale était située à Nara, alors connue sous le nom de Heijokyo, fut une courte période de transition avant l'importante période de Heian. Malgré sa brièveté, cette période produisit tout de même les œuvres littéraires japonaises les plus célèbres jamais écrites et certains des temples les plus importants encore utilisés aujourd'hui, notamment à Todaiji, le plus grand bâtiment en bois du monde à l'époque, qui abrite toujours la plus grande statue en bronze de Bouddha jamais réalisée.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note