#gudea

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

foundation nail with kneeling god | c. 2120 - 2110 BCE | ĝirsu, lagash, sumer (modern day dhi qar governorate, iraq). reign of gudea.

in the louvre collection

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

#gudea is a style icon#𒅗𒌤𒀀 𒅇 𒁹𒁹𒁹 𒇽𒈨𒌍#𒅗 𒌤 𒀀#gù-dé-a#sumerian#gudea#sumer#ancient history#ancient art#lookbook#ἐποίησα

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! might be a little out of your wheelhouse, but i was recently watching a video about math and sumerian architecture (we found a lost temple using maths sent by an ancient sumerian god | curator's corner w. matt parker) and at roughly 15:00, the curator says that this one bit of text translates to "to make things function as they should"

i tried to find a more in-depth translation of this but couldn't find anything, so maybe i'm just not looking in the right places, but any help would be great!

Hello, and thanks for sharing this video! Link is here for anyone who wants to watch, it discusses Sumerian math, architecture and Gudea. Note first that the text in question is written vertically along the statue's skirt, so you have to tilt your head to the right to be able to read the signs.

I couldn't seem to find a version of this statue in transliteration, but I do recognize some of the listed signs, so found a similar phrase: Ningdu irinake pa bie, which the ETCSL translates as "He had everything function as it should in his city." From that I was able to piece together the rest, as the initial ningdu "propriety, what is as it should be" is the same, 𒃻𒌌, and the verb pa ... e 𒉺 𒌓𒁺 "to show, make manifest" appears too, though here with bonus verb prefix muna- 𒈬𒈾 "for him/her". The third sign looks to me like a mistranscribed final -e 𒂊, the directive case ending.

So the full phrase would be Ningdue pa munae 𒃻𒌌𒂊 𒉺 𒈬𒈾𒌓𒁺. And searching for that led me to several instances of this phrase, which Oracc generally translates as "For [him]... he made an eternal thing appear" or "For [him]... he made it appear in its correct form", with the [him] being a person referred to earlier in the text. (The muna- prefix isn't gendered, so it could also be "for [her]" etc, but all the examples I found refer to a man or male deity.) See also the similar phrase at the start of The Song of the Hoe "Not only did the lord make the world appear in its correct form..." Ene ningdue pa nan'gamine.

I'd translate this phrase more fluidly/generally as "He made manifest the proper form/function for (so-and-so)". Parker's translation as an infinitive is an approximation given it's being pulled from context. I hope that's helpful!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I sogni lucidi di Gudea

Cari Lettori condivido con voi lo studio del Prof Verderame, un approfondimento necessario e autorevole circa gli argomenti che sono in programmazione in questo anfratto telematco 12 Verderame Sogni Gudea defDownload

0 notes

Text

The monumental royal cone of Gudea

Official or display cone excavated in Girsu (mod. Tello), dated to the Lagash II (ca. 2200-2100 BC) period and now kept in Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Sumerian Text

(d)nin-gir2-su ur-sag kal-ga (d)en-lil2-la2 lugal-a-ni gu3-de2-a ensi2 lagasz(ki)-ke4 nig2-du7-e pa mu-na-e3 e2-ninnu anzu2(muszen)-babbar2-ra-ni mu-na-du3 ki-be2 mu-na-gi4

Source: CDLI

Translated text

For Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of Enlil, his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made a fitting thing resplendent for him, and his Eninnu with the White Thunderbird he built for him and restored for him.

Source: P234000: royal-monumental cone

I see six names in the text, the names of two gods, the name of Gudea and the name of a temple [E+ninnu] (cuneiform e2 meaning temple), the name of the city of Lagasz (lagash(ki)) and the title ensi2 meaning governor and ruler.

Ninurta or Ninĝirsu (meaning Lord of Girsu) is the name of an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with agriculture, healing, hunting, law, scribes and war. He was the son of Enlil. In the text, Enlil is introduced as the lord of Ninĝirsu. (lugal-a-ni)

Ninĝirsu was honored by Gudea, who was the ruler of the city of Lagash (ensi2 lagasz(ki)-ke4).

Gudea mentions in the text that he built the Eninnu Temple (e2 ninnu 𒂍𒐐) with White Thunderbird for Ninĝirsu.

#history of mesopotamian kings#mesopotamia#ancient mesopotamia#archaeology#ancient history#akkadian#sumerian city#sumerian#sumerian language#city of girsu#gudea#sumerian kings

0 notes

Text

Statue of Gudea,

"Gudea, the man who built the temple, may his life be long."

Neo-Sumerian, circa 2090 BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

the bau epithet in E is so good though. the lady of lost things

i should develop a favourite gudea statue

#its nin ngin u-gu de-a: lady (of) things that have disappeared#(alternative translation)#i did Not know 'u-gu de' existed but. i do now#it's the same gu and de as in the name (gudea) which. is fascinating#ugu has no meaning on epsd2 except verbal compound#but u- does exist as a verbal prefix for past?#anyway gu=voice and de=pour out#i wonder if u-gu de carries a feeling of “things that have poured out their voice” or “things that no longer speak” or something?#so unbelievably not an expert btw. all i have is several dictionaries.#ref.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nail of Gudea

Sumerian, ca. 2144-2124 BCE (Lagash II; Ur III [Neo-Sumerian])

Clay cones and nails were inscribed in the name of a ruler of a Mesopotamian city-state to commemorate an act of building or rebuilding, often of a temple for a specific deity. Deposited in the walls or under the foundations of these structures, the words of the texts were directed at the gods but would be found by later restorers.

352 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, can I participate in your game?

Of course, thank you for participating🤍

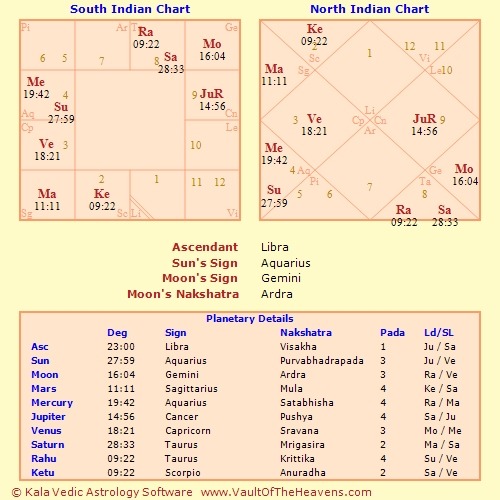

Your divine archetype:

🌧🌊🌋🔥 The pure wisdom of destruction, fierce compassion and the bringer of catharsys ⛈🌫🌩⚡

Your Goddesses:

Nisaba_ Sumerian goddess of knowledge, scribes and written word. She was first considered a grain goddess and there are no accounts of her as a writing goddess, but as she bacame increasingly important among Mesopotamian people, there were more and more stories written about her. In "Dream of Gudea", she is pictured as "a woman holding a gold stylus and studying a clay tablet on which the starry heaven was depicted".

Your moon nakshatra_ Ardra, is the first Rahu-ruled lunar mansion in the Mercurial sign of Gemini. Rahu relates strongly to the written word, the essence manifested in a form, or just forms with no essence. Essentially, Ardra can be viewed as the birth of logic, analysis, complex thoughts, complex feelings, complexity in general, rationality and all that can be debated. In short, it's the nakshatra of collective humanity and its views, and since it's the first nakshatra of such overwhelming information and neural activity, it's also the nakshatra of pain and the birth of sufferring, where the "trauma" is arguably at its peak.

There is obviously more to your chart, but to begin with your most important placement is important to me, as it sets the tone for the whole thing.

Your dominant element is Air, with all of your big three placements being in the three Air signs_ a huge emphasis on the element of communication, rationalization, thoughts and cerebral activity in general.

Seshat_ Egyption Goddess of knowledge, writing, the written word, often compared to Nisab. She is often depicted with horns and a star between them. It was ssid that Seshat knew how to measure the distance between stars, observe them and other celestial bodies.

Associated with the labeling aspect of knowledge, Seshat can be strongly associated with Rahu. The air elememt, in general, has a lot to do with communication and exchange of information.

Even though Jupoter nakshatras do not have associations with these on the same level, they still relate to this element's themes.

Kymopoleia(or, Cymopoleia)_ Greek sea nymph, often considered a goddess, who was said to have the power to usher sea storms. Her name means "wave ranging", and her other name_ Cymatolege, means "wave-stirrer". She was married to Briareos_ hundred-handed storm giant.

So, sea storms are quite literally probably the most direct association Ardra nakshatra can have. This stirring and violent, tense energy is one of the defining aspects of this lunar mansion. The notable thing is that in your chart, your other big three nakshatras_ Vishakha and Purva Bhadrapada, also have this type of energy, especially the latter, because of its shared association with the god Rudra with Ardra.

All of these nakshatras tell a story of upheaval, of destruction and transformation towards something new, of righteous anger directed from the inner self to the goal of intense cleansing. They want to transmute their energy in a cathartic way, even if it looks "wrong" or rebellious to others, sometimes, especially if that is the case.

A goddess from Armenia_ Tsovinar, is eerily similar to her, who rules over water, sea and rain. Her name means "daughter of the sea", and she was said to make "rain fall down from heaven with her fury".

I'm going to move on to other goddesses who relate to those in some ways, but you can read about Kymopoleia in my Ardra as a goddess post.

Astrape and Bronte_ Greek goddesses, personifications of lightning and thunder respectively. Their task is to carry the lightning bolts of Zeus with pegasus, also being his shield bearers.

Vishakha nakshatra is related to merging opposites, and with that exchange, creating something bigger than the sum of what they both are separately. This generates electricity, so, Vishakha at large can be considered a nakshatra of lightning and thunder. Ardra is also associated with the thunderous cries and the rainy storms.

Sekhmet_ Egyptian goddess of war, fire, dance and medicine, often depicted as having a lion's head. She was said to have the ability to inflict disease on masses but also cure it. She could breath fire from her mouth, an ability that was likened to the desert wind.

Sekhmet was also considered as a Solar deity.

While your Rahu and Ketu are not technically in their exaltation nakshatras, they are still in their exaltation signs(Taurus and Scorpio), activating the axis of one of the Sun-Saturn nakshatra oppositions, that of Krittika and Anuradha. Rahu in a chart is said to represent what a person is meant to become. Krittika has thematic connections to Purva Bhadra_ it's the literal consuming fire that the excess of P. Bhadra is cleansed and reduced in, and it's also a Solar nakshatra.

Ketu in Anuradha though, amplifies the already relevant Saturnian influence, and adding to the occult associations(Sun in Saturnian Aquarius, Saturn Atmakaraka). Your Rahu is in the 8th house, meaning that you approach the matters of secrecy, sexuality, anything occult with carefulness and great precision, otherwise avoiding it alltogether. The material world is that of familiarity and reliable, however, and it's the key to accessing the energy that you'll eventually have the intense need to release.

There is definitely an aspect of healing in your chart. There is so much energy that is moved, that a change is almost certainly imminent.

There is a myth where at the end of his rule, the Sun god Ra sends goddess Hathor(associated with Uttara Bhadra) in the form of Sekhmet to destroy all mortals who have conspired against him. She did as he said, and her thirst for blood was not quenched at the end of that battle. She went on to destroy Egypt and wipe out almost all of humankind.

To stop her, Ra and other gods devised a plan to pour a lake of beer that resebled blood, dyed red from ochre. Mistaking it for actual blood, Sekhmet drank it, became too drunk and gave up on her violent endeavor.

To add a few goddesses, Yoruban Oya_goddess of winds, Greek Sophia_ Goddess of wisdom and Hindu Tara_ savior goddess are all in one way or another relevant to your chart.

If you want to research or find other goddesses yourself, you can search for goddesses of lightning, fire, rain, sea, wisdom, perserverance through challenges... etc.

As a last note, your chart ruler is Venus(Libra ascendant), and your atmakaraka(along with your rahu) is in Taurus. There is a Venusian influence in you, one that is focused towards restraint and harmony. If you feel called to, you can look for goddesses connected to that.

...

This is it, hope you found this helpful.

Please, leave a feedback in the asks after reading. 💕

#vedic astrology#astrology#nakshatras#astrology observations#sidereal astrology#astro notes#astrology tumblr#ask#goddess essence game#ardra#vishakha#purva bhadrapada#gemini#libra#aquarius#rahu#jupiter#saturn#venus#sun#mercury#air signs

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anunnaki 𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾 The earliest known usages of the term Anunnaki come from inscriptions written during the reign of Gudea (c. 2144–2124 BC) and the Third Dynasty of Ur. In the earliest texts, the term is applied to the most powerful and important deities in the Sumerian pantheon: the descendants of the sky-god An. This group of deities probably included the "seven gods who decree" An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of Gudeo—Girsu, Mesopotamia, 2090 BCE

According to the Met: "The Akkadian Empire collapsed after two centuries of rule, and during the succeeding fifty years, local kings ruled independent city-states in southern Mesopotamia. The city-state of Lagash produced a remarkable number of statues of its kings as well as Sumerian literary hymns and prayers under the rule of Gudea (ca. 2150–2125 B.C.) and his son Ur-Ningirsu (ca. 2125–2100 B.C.). Unlike the art of the Akkadian period, which was characterized by dynamic naturalism, the works produced by this Neo-Sumerian culture are pervaded by a sense of pious reserve and serenity.

This sculpture belongs to a series of diorite statues commissioned by Gudea, who devoted his energies to rebuilding the great temples of Lagash and installing statues of himself in them. Many inscribed with his name and divine dedications survive. Here, Gudea is depicted in the seated pose of a ruler before his subjects, his hands folded in a traditional gesture of greeting and prayer.

The Sumerian inscription on his robe reads as follows:

When Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of Enlil, had established a courtyard in the city for Ningišzida, son of Ninazu, the beloved one among the gods; when he had established for him irrigated plots(?) on the agricultural land; (and) when Gudea, ruler of Lagaš, the straightforward one, beloved by his (personal) god, had built the Eninnu, the White Thunderbird, and the..., his 'heptagon,' for Ningirsu, his lord, (then) for Nanše, the powerful lady, his lady, did he build the Sirara House, her mountain rising out of the waters. He (also) built the individual houses of (other) great gods of Lagaš. For Ningišzida, his (personal) god, he built his House of Girsu. Someone (in the future) whom Ningirsu, his god - as my god (addressed me) has (directly) addressed within the crowd, let him not, thereafter, be envious(?) with regard to the house of my (personal) god. Let him invoke its (the house's) name; let such a person be my friend, and let him (also) invoke my (own) name. (Gudea) fashioned a statue of himself. "Let the life of Gudea, who built the house, be long." - (this is how) he named (the statue) for his sake, and he brought it to him into (his) house."

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am interested to know about the 4 winds and what is their role in mythology

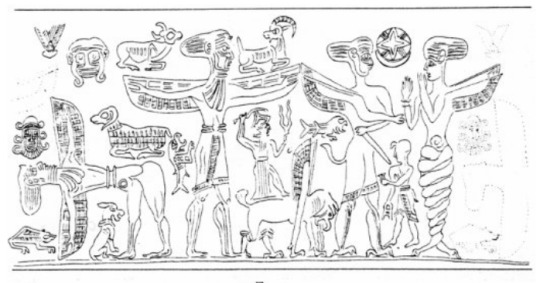

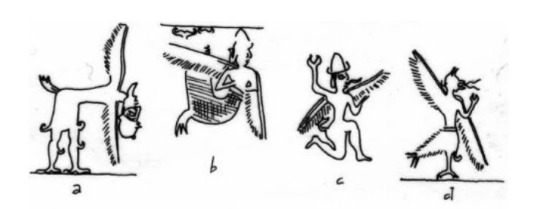

You’re in luck because while there isn’t much material, it’s fairly easily accessible - by reading Wiggermann’s The Four Winds and the Origin of Pazuzu you can learn 90% of what there is to know. However, since he doesn’t cover the myth(s) involving the South Wind, I figured a brief summary is in order - you can find it under the cut. All images are taken from Wiggermann’s article, and have been reproduced here for educational purposes only.

The four winds are the West Wind (Amurru; not identical with the god Amurru), the East Wind (Šadû), the North Wind (Ištānu; no relation to the phonetically similar Hittite designation for sun deities) and the South Wind (Šūtu; I’m not aware of any connection to the goddess Sutītu, who was essentially a deified Sutean - ie. “Southerner” - stereotype much like how Amurru was a deified stereotypical Amorite). The names are virtually always translated into English, so I’ll stick to following this convention here. The South Wind, who has a plenty of solo attestations as a literary character, is usually female, and the other three male; this reflects the grammatical gender of their names. However, there is at least one case where the North Wind is referred to with feminine terms regardless of that. It seems fairly consistent that regardless of their gender the four are treated as siblings, though. We know they shared the same mother but her identity is never specified. Not that unusual, really. In Mesopotamian astronomy, the winds’ names could also refer to specific constellations: North Wind is Ursa Major, South Wind is Piscis Austrinus, West Wind is Scorpio and East Wind is Perseus and the Pleiades. Note that some of these connections are not exclusive to them; Scorpio or individual stars forming it could be instead associated with Ishara, Ninigirimma, or even Lisin.

While it can be difficult to identify minor deities in Mesopotamian art, the four winds are distinct enough to make this fairly straightforward to researchers. All of them are depicted with wings and windswept hair (of course), but there are additional traits unique to each. The South Wind, as expected, looks feminine and typically has entwined legs; the North Wind is partially theriomorphic (the rest has no animal traits save for their wings); the West Wind is bent over in an acrobatic pose; and the East Wind is, essentially, a “generic wind” iconographically. The oldest example of a depiction of the group is a seal from Sippar from the nineteenth century BCE, which shows the four of them surrounding a weather god, presumably Adad:

Wiggermann based on this attestation suggests that the group might have originally emerged from the theological speculation of Adad’s clergy from Sippar, and that the seal might depict a set of statues displayed at his local temple. Hard to prove, but compelling, imo. However, personified winds occasionally can be found in earlier sources too: one of Gudea’s inscriptions poetically described the North Wind as a winged man, there’s also a seal from roughly the same period showing Adad, his spouse (presumably Shala) and a winged attendant who might similarly be a wind. However, they were not exclusively associated with the weather god - there is also at least one reference to them acting as messengers of Anu instead. South Wind sometimes appears as a servant of Ea, as well.

With time, the South Wind essentially overshadowed her siblings, and could be recognized as an independent wind deity. She eventually lost part of her original iconography: the wings vanished, but a standard horned crown started to appear on her head, indicating stabilization of her status as a deity. She plays a major role in the myth Adapa and the South Wind. The eponymous hero breaks her wing (or both of her wings) with a curse (notably no physical contact occurs), and as a result she stops blowing. Anu therefore summons Adapa to heaven. He plans to essentially deify him, but this doesn’t come to pass because Ea convinced him to refuse any gifts he might receive.

In this article you can learn more about the history of this myth. Most notably, recently a new version has been discovered during excavations at Tell Haddad (ancient Me-Turan). This is relevant to your question since it seems to its compilers it was South Wind who mattered more than Adapa - the narrative is more concerned with her restoration than with its expected protagonist! Anu asks Adapa why did he break her wings, he seemingly does not answer, and instead the focus shifts to declaring a new destiny for the South Wind. Her arrival is said to bring an unspecified disease, which however is also cured by her departure. By breaking her wings, Adapa made her unable to leave, which seemingly meant the disease could not be cured. Interestingly, this might actually be the original form of the myth - in other words, it was originally about the South Wind, with Adapa as a side character, with the switch of importance only occurring later.

Next to the South Wind, the West Wind probably fared the best once the group ceased to be depicted together. He absorbed his brother’s non-human traits, and in the Middle Babylonian period sometimes had the tail of a bird or stinger or a scorpion, and on top of that a set of talons. The acrobatic pose remained consistent, though. Wiggermann thinks that he was subsequently fused with the apotropaic image of Humbaba’s head to create a prototype of Pazuzu, but this remains speculative.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you had to pick the top five coolest sounding words in sumerian, regardless of what they mean, what would they be?

What an interesting question! I had my twitch community help brainstorm some words, and here's what we came up with.

My longtime favorite is ngarngarngar, which means "hospitality" or "careful preparation (as for a guest)". It's written 𒃻𒃻𒃻 so literally means "prepare-prepare-prepare".

I love shakira, which doesn't refer to a Colombian pop star but instead means "butter" or "butter-churn". I used it, along with shadibshezeda "bitter artichoke", in a haiku I wrote way back in the day.

One that I say often because it's so useful is gana!, meaning "let's go!" "yeah!" "indeed!" "you can do it!" etc. It can be used to encourage others but is most often used to encourage oneself: Gudea Cylinder A says Gana! Ganabdu! "Come on! I have to tell her about it!", wildly relatable in my opinion.

From my infamous Sumerian insults post, the one I use most often is agaashgi "most awkward person", which is both fun to say and incredibly useful. Check that post for more fun ones, like igibala "traitor" - if Sumerians had soap operas they'd definitely gasp igibala! at the most dramatic moment.

And twitch chat nominated the phrase kulinambura, from kuli "friend" and nambura "payment" - how I'd say "PayPal" in Sumerian. It rolls off the tongue, and what word is cooler than kuli?

If y'all have favorite Sumerian words, please share them in the comments or reblogs!

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gudea, Prince of Lagash, c. 2090 BCE, Neo-Sumerian / Ur

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

After being chased out of our camp by the powerleveler, my group was pessimistic about finding another one, as Velketor’s Labyrinth had become the server’s most popular leveling zone. After trying a few different picks, however, we got very lucky, and were able to lay claim to one of the two best camps in the zone: “inner castle” (IC). As the name suggests, the camp is located within a castle at the heart of the labyrinth, and serves as the sanctum of Velketor the Sorcerer himself.

My group had no intention of challenging the exiled giant, of course, and was content to instead battle his minions. Setting up camp in the castle’s basement, a group member showed me around the area, and before long we were shattering golems and gargoyles with abandon. One of my groupmates, Gudea, was kind enough to give me a set of powerful magical drums (Drums of the Beast) he had found on an earlier adventure. I made levels 56 and 57. Kudos to Bourbon, Burien, Danger, Gudea, Soulclapx, Sskinz, Tainx, Trielle, and Waandering!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

While drawing the Manager after MotR and comparing to my earlier pre-MotR attempts, I thought maybe I can also try to combine the canon version with what-have-been-in-my-head-for-years-of-text-descriptions – different eye colour (dark or brassy), a bit older, not as spotlessly smooth-faced...

Then I wondered if I’m too influenced by "Mesopotamian = beard" stereotype (in fact there are plenty of beardless kings in Sumerian and Akkadian art, such as Gudea or Ibbi-Sin, off the top of my head). Hmm, I thought, actually I can imagine him shaving while whistling nursery rhymes and casually ignoring that the mirror can’t properly reflect him without bleeding nightmares...

Then I remembered that in cultures where beards have significance, shaving it off is also usually a sign of mourning, self-shame or grief. And in MotR a whole city was destroyed just a few months ago, and a new one fell similarly catastrophically:

...so at that time May does have a reason to be in mourning (at least formally/ritualistically, if he wasn’t close to those he knew in the Fourth City). Even more, he might have been grieving since the First City, judging by how he always speaks of his story with no ability to let go.

Oh well. 5 years in Fallen London, and I still can’t think about him without this risk of unscheduled emotions. Even over visual design, forgodssake. (Though these cheekbones ARE heart-wrenchingly gorgeous, by the way.)

32 notes

·

View notes