#glenda gilmore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Breaking the Dollhouse/Final Family AU

@barclaysangel @streets-in-paradise @fairchilds-glasses

*The first time Andy taught Nica and the triplets how to use a firearm*

Glen: Wow. *turns to Nica* He has much knowledge.

Nica: We shall form a cult around him.

Glenda: Build a statue many stories high.

Junior: We shall grow our hair long and stop bathing.

Andy: *amused* Please, don't do any of that.

#chucky#chucky 2021#child's play#chucky syfy#andy barclay#nica pierce#junior wheeler#glen ray tilly#glenda ray tilly#final family#breaking the dollhouse#chucky incorrect quotes#source: gilmore girls

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

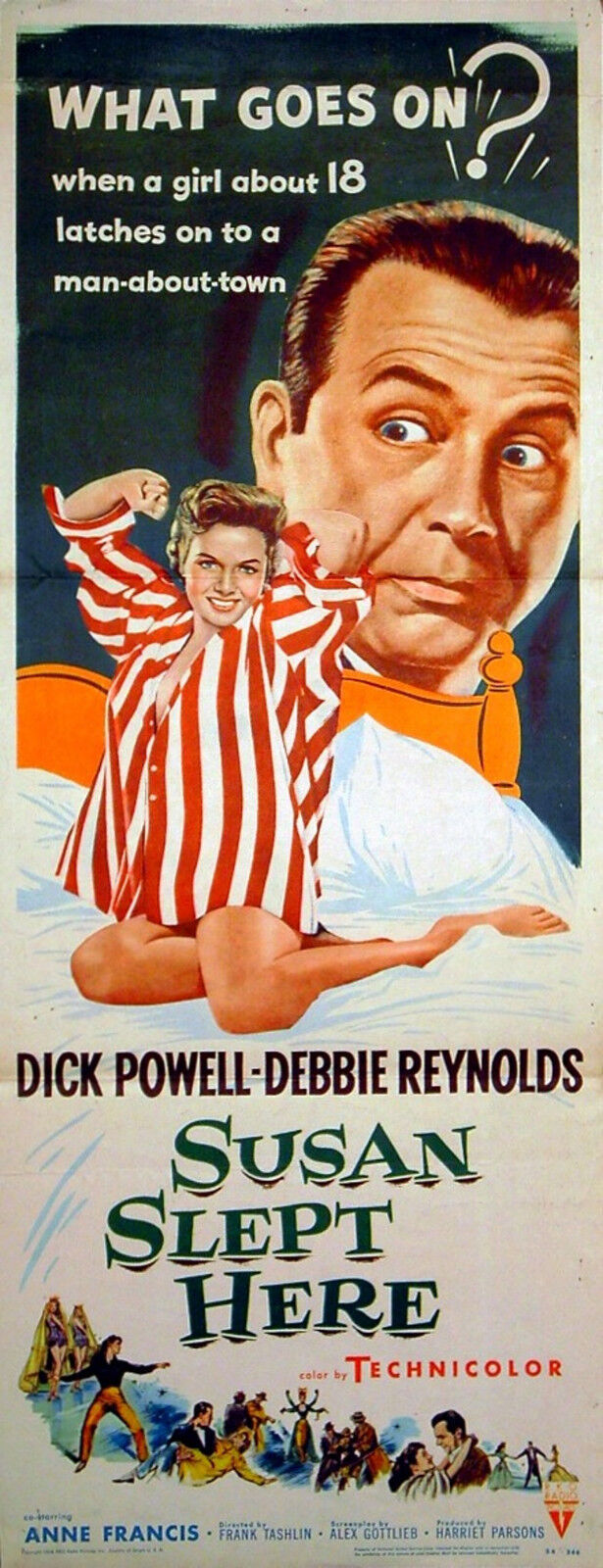

Bad movie I have Susan Slept Here 1954

#Susan Slept Here#Dick Powell#Debbie Reynolds#Anne Francis#Glenda Farrell#Alvy Moore#Horace McMahon#Herb Vigran#Les Tremayne#Mara Lane#Rita Johnson#Maidie Norman#Lela Bliss#Daws Butler#Ken Carpenter#Ellen Corby#June Foray#Rudy Germane#Art Gilmore#Barry Norton#Louella Parsons#Murray Pollack#Benny Rubin#Bernard Sell#Red Skelton#Norman Stevans#Brick Sullivan

1 note

·

View note

Text

His Girl Friday (1940)

Date Watched: 24/01/2023

Referenced in: 4x05, 6x05 and 7x18

Rating: ★★★★★

What an incredible film that stands the test of time. Brilliant funny film with great performances from Rosalind Russell and Carey Grant! The supporting cast is brilliant too. I recommend this film to anyone - The opening scene is my favourite, the banter between the main leads is just amazing.

-

(Other GG Movies I’ve watched so far)

(Full references under the cut)

4x05, The Fundamental Things Apply (2003) Lorelai questioning Luke on what movies he's seen LORELAI: You have never seen "Casablanca"? Are you kidding? LUKE: Just get anything, please. LORELAI: "Chinatown"? LUKE: Anything at all. LORELAI: "Bonnie and Clyde"? LUKE: A video game would be nice also. LORELAI: "It Happened One Night"? "His Girl Friday"? "Treasure of the Sierra Madre"? "Diner"? LUKE: I saw "Mr. and Mrs. Bridge." LORELAI: Oh. My house, eight o'clock. We have such work to do.

6x05, We've Got Magic to Do (2005) Rory says that Lacey is "my girl Friday." RORY: The Swing Dolls, everybody. (Richard walks back into the main Hall, as the people applaud) I'm Rory Gilmore, the architect of this event. (everyone starts to applaud again. Emily looks radiant) Thank you. And I'd like to take this moment to thank some others for the outstanding success this evening. To Lacey Boscombe, my right hand, my girl Friday, I could not have done it without you. To Glenda, Lance, the entire serving crew, thank you. To the kind people at KBC Audio who generously donated this amazing...(as Rory delivers her "Thank You" speech Richard looks at her with great sadness)

7x18, Hay Bale Maze (2007) Rory mentions the film while debating what to wear to her interview. RORY: Okay, I need to pick out a coat. A trench coat would be too "All The President's Men," but my blue coat would be too "His Girl Friday." PARIS: I'm just gonna cut to the chase. Why are you here? LOGAN: You're not talking metaphysically, are you?

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If the United States invades Iraq without provocation on the grounds that Saddam Hussein might hurt us in the future, we will forever change our national character. Who are we? Aren’t we the nation that deplored Japan’s pre-emptive strike against Pearl Harbor and denounced Hitler’s invasion of Poland? Even in wars that provoked much internal criticism, we responded to what we asserted were invasions of South Korea, South Vietnam and Kuwait. This time we are the invaders. No matter how much Bush tells us we are the good guys and Hussein is the bad guy, the president will not be able to change the historical fact that we attacked another sovereign nation without provocation. We are the good guys. But good guys don’t invade other countries, unless they have exhausted every other option for self-preservation. If they do, they become the bad guys.

Glenda Gilmore

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Test Bank for These United States A Nation in the Making: 1945 to the Present by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore bbn

Contents Full Edition: Chapters 1-15 Post-45 Edition: Chapters 8-15 Chapter 1. Origins of the American Century Chapter 2. "To Start to Make This World Over": Imperialism and Progressivism, 1898–1912 Chapter 3. Refining and Exporting Progressivism: Wilson's New Freedom and the Great War, 1913–1919 Chapter 4. Prosperity's Precipice: The Paradoxes of the 1920s Chapter 5. A Twentieth-Century President: Franklin Delano Roosevelt's First Term, 1932–1936 Chapter 6. A Rendezvous with Destiny, 1936–1941 Chapter 7. The Watershed of War: At Home and Abroad, 1942–1945 Chapter 8. A Rising Superpower, 1944–1954 Chapter 9. Postwar Prosperity and Its Discontents 1946—1960 Chapter 10. A Season of Change: Liberals and the Limits of Reform, 1960–1966 Chapter 11. May Day: Vietnam and the Crisis of the 1960s Chapter 12. Which Side Are You On? The Battle for Middle America, 1968–1974 Chapter 13. A Season of Darkness: The Troubled 1970s Chapter 14. The New Gilded Age, 1980–2000 Chapter 15. United We Stand, Divided We Fall, Since 2000 Read the full article

0 notes

Text

"Southern whites cannot walk, talk, sing, conceive of laws or justice, think of sex, love, the family or freedom without responding to the presence of Negroes." – Ralph Ellison

The problem of holding the Negro down, therefore, is easily solved. When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his “proper place” and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. – Carter G. Woodson, The Miseducation of the Negro, 1933

-

When we discuss anti-Black racism, it must be noted that we are talking about a very specific root of white supremacy, one that is wholly unique – but still connected – to the anti-indigenous, anti-Muslim, antisemitic movement that infects and affects the [white] Western world.

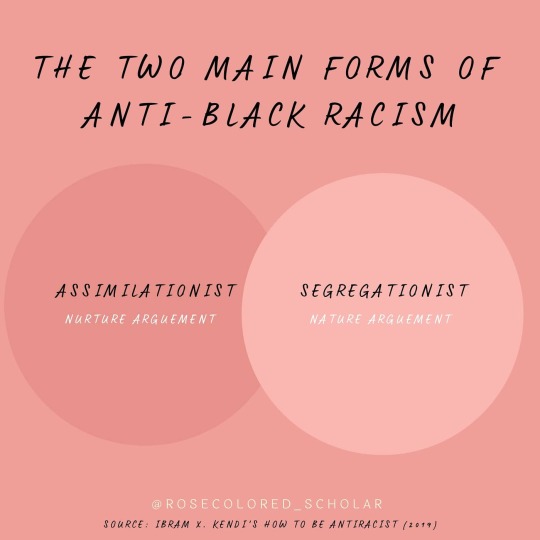

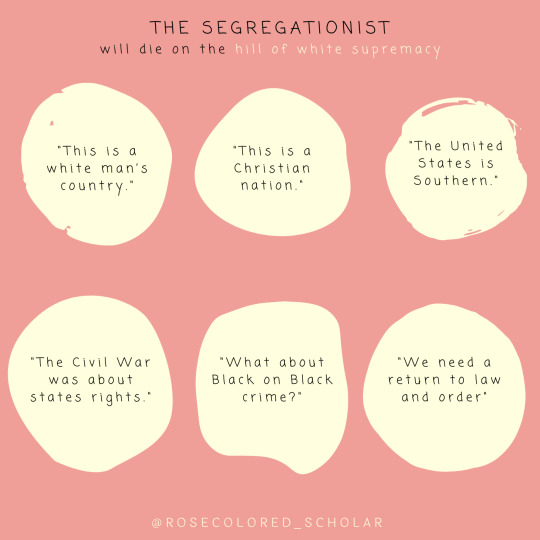

In the weeds of complexities and intersections, there are two major types of anti-black racism that dominate our public sphere: segregationist and assimilationist.

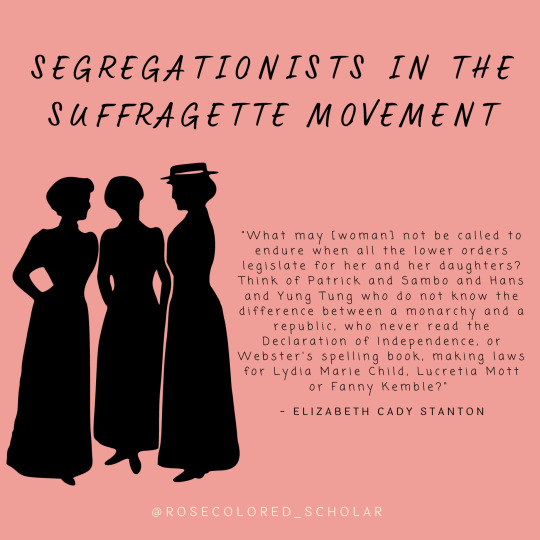

Segregationist is the school of thought we are most familiar with, in part, because white supremacist violence is both visible and vitriol.

Our minds supply us with images of the Ku Klux Klan and burning crosses, the Nazi sympathizers and defenders of the Lost Cause with confederate flags, the red-faced parents screaming at Ruby Bridges and the Little Rock Nine, and police officers brutalizing Black bodies peacefully protesting in the streets. These images were introduced to the [white] American public during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s on their living room television sets. They are now ingrained into our collective consciousness and we label those actions and images as RACIST. However, those the danger that comes with that system of reality is that it detaches us from the subtle, pervasive, and continuing politics and practices of segregationists’ work. The Klan did not create America's caste system. They merely reinforced it.

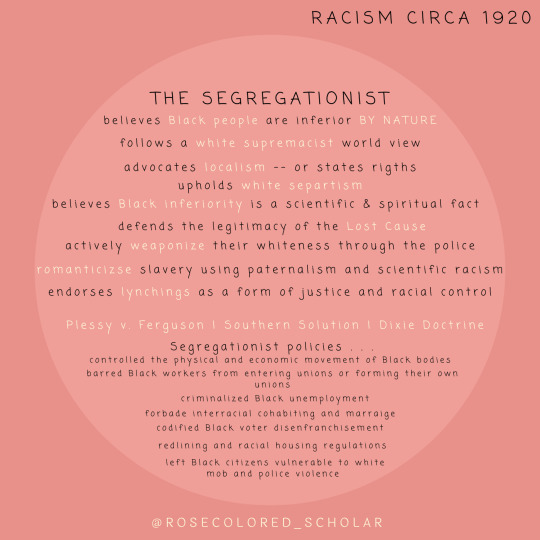

To understand segregationist thought, you must understand their historical AND contemporary system of reality.

Southern educator and researcher Thomas Bailey details in his 1914 work Race Orthodoxy in the South the racial credence that was adopted by the majority white Southerners:

Segregationists believe that Black people are inferior by nature. This idea is based on a multigenerational caste system that places Blacks as intellectually, socially, morally, and physically inferior to those who identify as white (or near white).

1. “Blood will tell.”

2. The white race must dominate.

3. The Teutonic peoples stand for race purity.

4. The negro is inferior and will remain so.

5. “This is a white man’s country.”

6. No social equality.

7. No political equality.

8. In matters of civil rights and legal adjustments give the white man, as opposed to the colored man, the benefit of the doubt; and under no circumstances interfere with the prestige of the white man.

9. In educational policy let the negro have the crumbs that fall from the white man’s table.

10. Let there be such industrial education of the negro as will best fir him to serve the white man.

11. Only [white] Southerners understand the negro question.

12. Let the [white] South settle the negro question.

13. The status of peasantry is all the negro may hope for if the races are to live together in peace.

14. Let the lowest white man count for more than the highest negro.

15. The above statements indicate the leadings of Providence.

(Scholar question: Which of these credence’s do you think still exist in our present-day spaces?)

While we have moved forward since Bailey’s book publication 106 years ago, some of these decrees are uncomfortably familiar . . . we often don’t want to analyze why the South, as a geopolitical region and former secessionist state, was able to enforce white supremacy in every area of public (and private) life nor do we care to examine how these policies set the tone for the rest of the United States in regards to the larger Jim Crow ideology, or Dixie Doctrine.

Dixie Doctrine, as defined in Glenda Gilmore’s massive work Defying Dixie, as the active participation and organization of white supremacists in both the South and nation’s capital who worked to reinforce the racial caste system.

While Jim Crow often exists in the pages of academia as a series of segregationist policies that influenced [white] public spaces, Dixie Doctrine showcases an international, color-coded solution for ever human deed and thought across color and racial lines. White supremacists believed that a racial caste system would spread across the nations – with the white race at the top.

Since the South was not a sovereign nation, Jim Crow’s – and, by extension, Dixie Doctrine’s – health depended on the federal government’s support of its administration and on receptive public opinion or – at least – the complacency of people both within and outside of the South. Scholar Amy Louise Wood notes that “with the final withdrawal of federal troops in the South in 1877, the use of violence to control the black population was practiced without hindrance, as white southerners sought to reverse the changes brought about Reconstruction and to restore the old social order” (Wood 762). The violence and disenfranchisement that covered the Jim Crow era came about, in part, due to the vacuum created by the disruptions and dislocation of the New South:

In this new environment, one’s social status was less known and less fixed and traditional forms of authority—the patriarchal household, the church, the planter elite—were called into question. Moreover, interactions in industrial workplaces and exchanges in the commercial marketplace could potentially place white and blacks on equal footing . . . white southerners reasserted their authority amid these changes through the systematic disenfranchisement of African Americans and the establishment of racial segregation throughout the 1890s. (Wood 764)

Jim Crow took the national stage when Southerner Woodrow Wilson became president in 1913. The first national Congress under his leadership saw no less than 20 bills presented that pushed for Jim Crow legislation in DC. These bills included segregated train cars – or Jim Crow cars – race segregation of federal jobs, racial exclusion from military service, and tougher miscegenation laws. Under his administration, any form of legal or economic justice for Black Southerners (and Black citizens across the United States) was merely a calculated maneuver meant to “make Jim Crow work more smoothly” (Gilmore 19).

Under Woodrow, the United States saw one of the worst decades of anti-Black violence – over 100 Black individuals were lynched, shot, or burned in 1915 alone. Following the 1920s, the Great Depression fueled a whole new way of violence against black Southerners and Westerners who were seen by working-class whites as competitors for labor jobs. Since many Black workers were willing (or forced) to work for lower wages and were barred from unions, they were seen by many industrialists as the perfect workers to exploit for labor, given that their protests were met by overwhelming police force. Black laborers also had to worry about the possibility of being fired for speaking out or protesting given that most Southern states had strict vagrancy laws that targeted unemployed Black men, who were then shuffled into hard labor camps and chain gangs for indeterminate amounts of time.

Employing overworked and underpaid Black workers over white union workers and independent laborers also served to deepen the established racial divide since employment not only guaranteed wages, but also served as a social and economic barometer in the reimagined, industrial age. This resented not only resulted in heightened racial violence, but also squashed any potential interracial efforts to create inclusive unions and strengthen better workers’ rights.

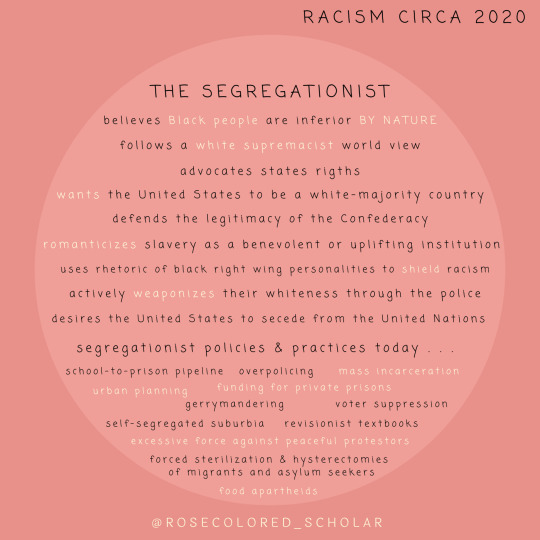

In summary, white segregationists are very concerned with the economic, political, and [spiritual] advancement of Black, brown, and indigenous people. When author Isabel Wilkerson noted in a recent interview that Trumpians were not only voting on issues relating to 2016 (and now 2020) but also the "Race Question" of 2054 (the year when, according to our census, the United States will no longer be a white-majority country).

-

The idea of race & caste runs so deeply, and the suggestion that white Americans will no longer be the political and racially dominant group comes from the same place of fear that white Southerners in the 1870s and 1920s used to justify their racial violence and segregationist system of reality . . . .

Join my patreon and follow me on Instagram @rosecolored_scholar

#history#white supremacy#leon litwack#glenda gilmore#padawan historian#antiracist liberation#rosecolored_scholar#segregationists#assimilationists#understanding racism#carter g. woodson#scientific racism#antiracism#black lives matter#politics#woodrow wilson

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

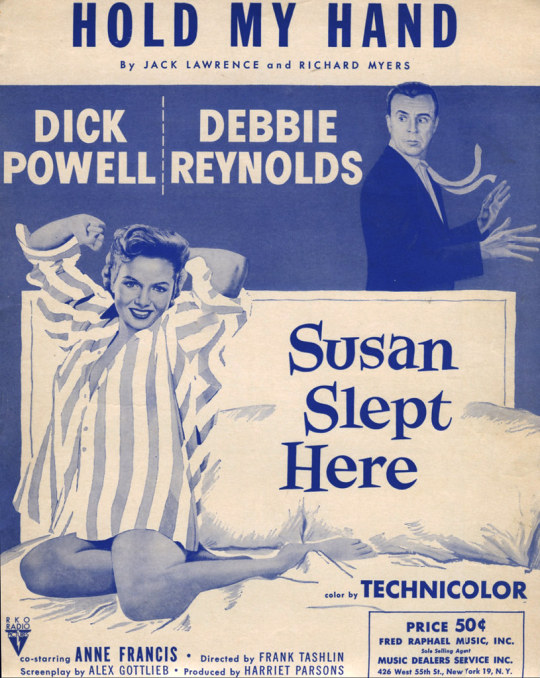

Susan Slept Here (1954) Frank Tashlin

December 22nd 2022

#susan slept here#1954#debbie reynolds#dick powell#alvy moore#anne francis#glenda farrell#les tremayne#herb vigran#horace mcmahon#maidie norman#mara lane#art gilmore#louella parsons

1 note

·

View note

Text

Character introduction: Connie

Basics:

Name: Connie Gilmore

Pronunciation: k- ah - n - ee | g- IH - l - m aw r

Meaning: Connie is an English name which means ‘constancy’ or ‘steadfastness’ (it’s ironic).

Gilmore is a reduced Anglican form of the Gaelic Mac Gille Mhoire (Scots), or Mac Giolla Mhuire (Irish). It means ‘servant of’.

Birthday: 13 June 1954

Age: 26

Pronouns: She/her

Sexuality: Lesbian

Siblings: One older brother

Parents: A single mother. Unknown Muggle father.

Other Family: None of note

Languages: English

Current Residence: Her friend Glenda’s couch

Hometown: Chicago, Illinois

Wizard Fun:

Ilvermorny House: Thunderbird

Year of Graduation: 1971 (flunked out)

Occupation: None currently

Pet: A brown rat, named Igor

Blood Status: Halfblood

Species: Human; Metamorphmagus

Patronus: Crocodile

Boggart: A swarm of bees (she’s allergic)

Amortentia: Old books. Shampoo. Chicago deep dish pizza.

Wand type: 11”, Jackalope antler core, hawthorn wood, surprisingly swishy

Affiliation: Neutral

Appearance:

Height: 5’4”

Hair Color: Naturally blonde. Hair colour fluctuates according to mood, but she favours red and blonde

Eye Color: Blue (naturally). Also varies

Typical Hair Style: Most days, shoulder-length red hair with bangs

Fashion Style: Typical muggle fashion of the period - mostly bohemian, thrifted clothes

Distinguishing Features: Varies, day to day. As a Metamorphmagus, Connie is constantly changing her appearance. However, her most distinctive features that you’ll likely see her with on the daily are the bright red hair, the up-turned nose, and icy blue eyes.

Personality: Connie comes across as a generally easy-going person. She doesn’t like conflict, nor does she like taking sides. She prefers to come across as laid-back and confident - she wants people to like her. She has a good sense of humour and has a genuine laugh that’s infectious (she snorts when she laughs). She’s always the one with creative ideas - however, she’s not a particularly hard worker, so she’s not often going out of her way to do things.

Positive Traits: + Creative + Humorous

Negative Traits: - Indifferent - Fickle

Quick Facts:

Connie is a Metamorphmagus.

She has an older brother who’s a Squib.

She is not currently on speaking terms with her mom.

She is a halfblood - mom is a witch, dad is a Muggle. She’s never met her father.

She’s not particularly skilled at magic - though she’s never cared to put effort into learning it and using it (she failed out of Ilvermorny before she could finish her seventh year). She only uses it when it’s absolutely necessary.

Connie wants to be famous amongst Muggles as a horror movie producer/director.

Her stance on the war is neutral. She could be swayed to join either side by the right person.

Theme song: “The Bidding” by Tally Hall

Headcanons:

Connie really loves disco music.

She has picked up photography and filming as a hobby, and only uses Muggle cameras.

She plays the monsters in her own amateur films using her Metamorphmagus abilities.

Connie once had a whirlwind love affair with a woman who was part-Veela. They met when she moved to London, through the gay club scene. Things ended rather horribly, but Connie still thinks about her to this day.

Connie’s hair is usually blonde and unstyled on days that she’s feeling sad, or just not feeling herself.

She keeps her wand in her boot, or stuck in her hair when she does an updo.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

**•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚*ABOUT THE WRITER**•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚*

Name: Ty Age: 24 Timezone: GMT+2 Wanted Plot count: 23 distinct ideas Character count: 6 Character ideas: 3

☑ Down to plot ☑ Down to ship ☑ Down to be messaged ☑ Will write: characters with out-of-the-box ways of interacting with the world around them; most romance tropes; NSFW content; hurt with comfort; violence and/or murder justified by plot; fight scenes; slice of wizarding life. ☒ Won’t write: graphic depictions of torture; plots ending in despair; self-harm.

**•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚*ABOUT THE CHARACTERS**•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚*

🖌 Devereaux Sauvage Jr [21, Pureblood, Beauxbatons, Death Eater by order of his father] - The son of French purebloods who value status over the free will of their own children, and who willingly offered up their son to the Dark Lord in order to maintain their privileged lifestyle. Works as a Junior Spellsmith in the French Ministry, where he spends his days refining and documenting new spells. When no one’s looking, he takes to the streets to graffiti anti-Voldemort and anti-pureblood protest art on the sides of prominent buildings under a pseudonym. Loves his crup, D’Artagnan, and enjoys painting. Recently betrothed to his childhood acquaintance/nemesis, Laure Deschamps.

☠ Fyodor “Theo” Bychkov [20, Pureblood, Durmstrang, Atticus House, Neutral but with a Dark Mark] - An ex-Death Eater who ran away from Russia to escape the life and find himself without just blindly following orders. Met his boyfriend, Declan, in Paris after sustaining injuries in an underground boxing fight, and moved to London with him on a whim. Currently working odd jobs. Rarely uses a wand because of childhood trauma. Dating Declan Whitlock.

🎙 Glenda Chittock [24, Muggleborn, Hogwarts, Ravenclaw, Neutral but openly critical of the Death Eaters] - An American Girl born in England who got the chance to finally live her dreams and be a witch. Though she spent much of her school career trying to navigate how to make friends and not alienate them, she’s found her footing now. Runs her own pro-muggleborn radio station, Sonorus Radio, where she plays exclusively muggle music, interviews those who have dealings in the muggle world to promote them, and brings in experts on distinctly wizarding concepts to educate those too afraid to ask about the culture. Plans to court Buck McKinnon.

☘ Clifford Gu [28, Half-blood, Ilvermorny, Pukwudgie, Neutral] - The unprophesied son of a Chinese-American family steeped in tradition, born half-deaf in possible retribution. Underwent speech therapy and tutoring most of his life to communicate better. After school, went straight into a parent-mandated Healer career until it all became too much. Fled to England to open his own magical plant nursery, all while lying to his parents about his true reason for leaving the continent.

✉ Ivelisse Cassidy [24, Muggleborn, no magical education, Neutral] - After running away from home to find her own path in life, quickly fell in with a no-good gang. Spent most of her time working to be indispensable - and was pretty good at it. When the whole situation went to hell, left with Georgie and his crew for a better life. Now runs a secondhand bookstore, Vellichor Books, in muggle London which doubles as a post office for messages you don’t want tracked. The price? A secret or a happy childhood memory. Open for shipping.

☢ Lonnie Gilmore [34, Half-blood, Squib, Death Eater] - A squib who has the misfortune to look like his disappeared father, and whose relationship with his remaining parent only grew more strained when his younger sister displayed metamorphmagus abilities. Spent his holidays reading his sisters books until he discovered that making potions didn’t require a wand or innate magical abilities. Was working as a bartender when he happened upon a Death Eater on a recruiting mission, and easily got manipulated into believing muggleborns are the reason squibs are born without magic. Moved to the UK to work as a potioneer for the Dark Lord.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If girls’ private schools encouraged an intimate atmosphere of nurture, sociability, and fun, much coeducational public schooling retained its competitive practices and was more challenging. Opponents of coeducation argued that the presence of girls feminized and compromised the secondary curriculum. But evidence suggests the contrary: that expectations of male achievement raised the stakes and the competition for girls.

As it was put in an 1841 article in Ladies’ Repository, in many young ladies’ seminaries ‘‘the girl is excused of strict scholarship. . . . She works to disadvantage. The mind itself has not been educated.’’ In contrast to girls educated at such ‘‘finishing schools,’’ the author argued, ‘‘see here and there is one who, we may say, has been educated—who has studied like a boy’’ and you will see ‘‘equality of attainment with any male youth of like years and pursuit.’’

Encouraging a girl to study ‘‘like a boy’’ was seldom the goal of the citizens who sponsored secondary schools; coeducational secondary schools which taught ostensibly parallel classes for boys and girls did not always deliver classes of like intensity to both. And sometimes, especially in the earlier days, there were different requirements for girls and boys. …Public schools sometimes attempted to soften lessons for girls so as to address the concerns raised by the debate over emulation.

Nonetheless, in comparison, the point seems indisputable. Girls studying in coeducational secondary schools were more likely to participate in a competitive and meritocratic form of schooling which rewarded and encouraged individual achievement among both girls and boys. Such schools published class rank and scheduled public exhibitions. Evidence from the few coeducational private boarding schools suggests that this might have been the case for both public and private, day and boarding schools.

Coeducation in practice in the nineteenth century included various arrangements governing the schooling of girls and boys together and apart. The word itself was of American origin and set up an implicit contrast with the tradition of same-sex schooling in Great Britain and in many parts of the American Northeast and South. Common grammar schools united boys and girls in the same classes under the same roofs, and many secondary schools adopted a similar model. Yet the ‘‘coeducating’’ of boys and girls in secondary schools, and sometimes even in grammar schools, generally involved some separation of boys and girls, by administrative order.

As we have seen, some high schools, particularly in the Northeast, went so far as to conduct parallel classes for girls and boys, using gender as a principle for dividing students into different sections for as long as they could. Gradually, however, throughout the country, school districts bowed to economic realities and chose to educate their boys and girls together, offering a common curriculum and a common standard for success. For those attending the new public high schools, which became increasingly common in the Northeast at midcentury, coeducational schooling meant attending schools which enrolled more girls than boys.

The actual ratio varied from school to school. Where the public high school served as a college preparatory school for the affluent native-born, the numbers of boys tended to increase. In less affluent or immigrant communities, boys instead would leave school to take jobs, and high schools would sometimes graduate two or even three girls for every boy. The underattendance of boys at high schools was a cause of regular lament by all, including girl students who were left without escorts after school social functions. Yet it presents the historian of gender with some interesting questions. Some of them are simply statistical. Did girls excel and win honors proportionate to their greater attendance at high school? Did they excel at greater rates than the statistics might predict? And if so, why?

Girls and boys attending public high schools shared a liberal curriculum, competition, and grades. Unlike female seminaries and convent schools, which taught ornamental and domestic arts alongside more traditional liberal studies, the public high school at midcentury and after did not offer a gendered curriculum. Instead, it taught a classical or liberal curriculum, rich in history, moral philosophy, mathematics, Latin, Greek, and French. Botany, chemistry, and physical sciences were also often taught. Girls and boys took these classes either together or in separate tracks, a significant commonality in a world otherwise stratified by gender.

Increasingly toward the end of the century, citizens and educators came to question the usefulness of this classical learning to boys and girls attempting to make their way in the working world. And when high schools responded, they brought the gender segmentation of the workforce into school. Commercial subjects supplemented liberal studies, and educators provided manual training and home economics to prepare boys and girls for the future. Even then, though, high schools retained an important core of liberal studies, which established common ground between boys and girls, as well as across classes. In high schools, girls and boys studied together and competed to master abstract subject matter which neither sex could lay special claim to.

In studying North Carolina’s African-American community in the 1890s, Glenda Gilmore has noted the significance of its leaders’ dissent from the Tuskegee program of agricultural education and manual training advanced by Booker T. Washington. She sees their defense of a classical curriculum for the children and grandchildren of slaves as significant resistance to attempts to create a separate caste in this country under Jim Crow.

Classical education was similarly important for girls, for it offered a common ground on which to compete and succeed beyond the hierarchy of gender. The practice of recitation, saying one’s lessons orally, was not initially designed as a competitive practice. It was simply the most convenient way to test rote memory, the common style of teaching and learning in most grammar schools in the nineteenth century. Yet recitation meant that all would know when a student succeeded, and when one failed.

More deliberate was the spelling bee, a competition that was both a game and a pedagogy. Some schools held public examinations, which elevated the pressure to ‘‘know one’s lessons’’ to a higher degree. Almost all schools scheduled exhibition days in which students read or recited pieces to the general public and received awards. (In fact, the decision of the cloistered convent schools to bar the public from the awarding of prizes in the mid–nineteenth century was a cause of conflict with parents.) The consequences of such a system for teenage girl students, as for boy students, were that strong students thrived while weak ones foundered. This is an obvious result, of course. Yet in the world of Victorian gender relations, what is significant is that girls and boys were playing fundamentally the same game, both competing in the rough meritocracy that such competition encouraged.

At least initially and sometimes later as well, they were not equally comfortable with that competition: domestic culture discouraged self-promotion in girls, and successful girls were sometimes abashed and embarrassed. Sometimes, too, parents did not notice, honor, or encourage girls’ school accomplishments. …But within the universe of the schoolroom and at schoolwide ceremonies (neither insignificant for a peer based social world), girl scholars were encouraged and rewarded for achievement—for scoring high, for spelling well, for accomplishments of both mind and habit. They felt the sweet rewards of victory in conquering rivals, earning respect, and taking as prizes a seat at the front of the room.

These school rules made the institution unique within a woman’s life as it extended from cradle to grave. Not in the family or the workplace or the halls of government did females and males share so similar an experience. Even within the church, where souls were ungendered, women did not preach, sit as deacons, or otherwise live out their identities as equal competitors for eternity.

Coeducational grammar and secondary schools made all kinds of distinctions, and even those who encouraged girls to compete might in the same breath warn against it. Yet medals were awarded and reputations made in coeducational high schools. Of all the unequal institutions, such schools were the least unequal, and thus must stand as both an important harbinger of the future and a transformer, gradually, of their present.

Girls outnumbered boys in school. Barring other factors skewing accomplishments, girls could thus be expected to outnumber boys on the honor rolls. All things being equal, girls should have been salutatorians and valedictorians and honor-roll students in percentages similar to their representation in the class. In fact, though, girls tended to do better proportionately than boys. Statistics on one school, the high school of Milford, Massachusetts, reveal that between 1884 and 1900 girls represented 64 percent of graduates, a ratio of nearly two to one. But girls accounted for nearly three-quarters of those graduating in the top ten places during the late century.

When valedictorians and salutatorians were designated, beginning in 1889, 86 percent of those so honored through the next decade were girls. Girls’ tendency to dominate the academic ratings was an accepted part of the school’s culture and can undoubtedly be explained in part by Milford’s policy, probably followed by many other schools as well, of granting honors on the basis of scholarship and deportment together.

Deportment grades measured decorum and tractability; both by socialization and reputation, girls could be counted on to turn in higher performances. Usually there were a few male standouts, but sometimes it was a clean sweep. In the class of 1887 at Milford, for example, boys were completely eclipsed. The class began with an equal number of boys and girls, thirty-one each. By the end of the four year span, though, the numbers had been dramatically reduced to twelve girls and five boys.

The student newspaper announced: ‘‘The girls claim the first ten in scholarship and deportment. In attendance three girls are perfect and in deportment eight; of these, two have the honor of being perfect in both.’’ The article ended by noting, ‘‘These are facts of which they may well feel proud.’’ The reference here is a bit unclear. Perhaps it was referring to the individual girls who had triumphed, each of whom should feel proud. But a more plausible reference is to girls of the class as a group, all of whom, the article suggests, might take pride in their sex’s collective sweep of graduation honors.

How much of girls’ success can be attributed to their greater skill at achieving perfect conduct? For girls, for whom ‘‘being good’’ was a high priority, school offered any number of ways to fulfill that mandate. If being ‘‘perfect’’ simply required getting to school every day, or behaving once in school, it was certainly doable—a gratifyingly concrete measure for an otherwise elusive moral status.

Almyra Hubbard, a schoolgirl diarist in Hayesville, New Hampshire, wrote in 1859 of her discovery of this back door to school achievement. She knew that she worked hard; her journal, a school assignment itself written faithfully in a careful hand, indicates as much. Yet she did not get top grades and did not seem to be one of the handful of students she mentioned in February who would need to draw to see who got the first seat in the class. She could, however, make sure she got to class—a trip that took her an hour and a half when she walked it—and she seized upon this route to class honor.

One day, she wrote in her journal, ‘‘There are but few scholars here this afternoon. The room is quite still.’’ The quietness was not just a result of how many were there, but who was there: ‘‘As a general thing the noisy ones do not venture out in unpleasant weather.’’ Almyra Hubbard was both quiet and present, even when her classmates were fair-weather scholars.

When she attended her great uncle’s funeral in April, it was the first time she had missed school in a year and a half. In May the school principal adopted a new rule which advantaged Hubbard, ‘‘by which any one who is absent cannot make up her lessons.’’ She imagined, ‘‘It will cause some of the girls to be a little more regular in their attendance at school.’’ One key component of school success, as Almyra Hubbard had discovered early, was simply the ability to meet school demands for the regular habits of industrial discipline.

Girls outdid boys in this arena so regularly that when the Milford paper in 1890 reported on two students with perfect attendance throughout their high school careers, it featured what was newsworthy: ‘‘Wonderful to relate, one is a boy!’’ Not all girls had stellar grades in deportment. A consistent problem for boy and girl students both was ‘‘communication.’’ Students in many schools were forbidden to talk among themselves between classes and expected to be quiet most other times, an expectation which few could meet. The entire first-year class at Milford High School in 1865 was called to the teacher’s desk and scolded so that they nearly all cried, Annie Roberts Godfrey reported.

Godfrey was in the second-year class, and was also called up, where she ‘‘acknowledged that I had communicated but would try to improve. I did not cry.’’ The next year, though, Godfrey’s problems with communication meant that her deportment grade was very low—‘‘only 78, lowest in school, I fear.’’ We have no records for how Godfrey fared at graduation, but clearly convent schools were not alone in attempting to impose serious constraints on student sociability during school itself. It was an innovation in 1894 when Salem High School instituted a ‘‘whispering recess,’’ which allowed students to talk softly between classes.

- Jane H. Hunter, “Competitive Practices: Sentiment and Scholarship in Secondary Schools.” in How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

the following characters have fourty eight hours to please post, or else their characters will be reopened on friday 9:42pm nzst --

Hector Kelly

Connie Gilmore, Rene Deschamps, Elizabeth Burke, Marina Scarr, Cherry Scrimgeour, Noah Harris, Ellie Dowson, Otto Bagman, Ernest Richards, Aja Ansari, Sigrid Hellstrom, Santiago Smith, Benvolio Solace, Belinda Sun, Montgomery McKinnon, Henrick Drake, Laisren Mackenna, Basil Pierce, Nikau Parata, Patricia Rakepick, Hestia Jones, Albert Runcorn

Poppy Potts, Wendy Fletcher, Zina Batista, Echo Voltaire, Dorcas Meadowes

Dexter Bennett, Dirk Creswell, Declan Whitlock

Bonnie Blake, Maxine Flint, Thalia Mendoza, Edgar Bones, Riley Wood, Ricky Moon

Regulus Black, Lorcan d’Eath

Lily Evans, Amelia Bones, Remus Lupin, Xenophilius Lovegood

Adelaide Boot

Fyodor Bychkov, Glenda Chittock, Clifford Gu, Devereaux Sauvage Jr, Lonnie Gilmore, Ivelisse Cassidy, Kimiko Monet, Rhys Amin, Whitney Jaggernauth, Azriel Emmanuel, Valentijn Vos, Harrison Marchbanks, Jack Doe, Euphemia Abernathy, Shivaun Reaver

Charity Burbage, Walter Shafiq, Algilbert Fontaine

Archie Graves, Carolina Snyde, Gwenog Jones, Melanie MacDougal, River Hedley

Valerie Petrov, Sebastian Laviscount, Mara Lovelace, Calista Travers, Araminta Valentine, Nimue MacKenna, Sorina Rosales, Leilani Ishikawa, Estrella Norwood, Theodora Zabini, Petra Ulvehud, Elodie Corbin, Ava Davudi, Inala Greentree

Andromeda Black, Antonin Dolohov, Barty Crouch Jr, Castor Dolohov, George Calloway, Kassandre Fairchild, Logan Buchanan, Mafalda Hopkirk, Mason Mcelreath, Max Winters, Melinda Dolohov, Miraphora Mina, Thorfinn Rowle, Vareena Gore

Juliette McLaggen, Beatrice Hoffman, Pandora Lovegood, Gladys Gudgeon, Cristine Avery, Deidra Wolfram, Cadence Bell, Lane Macmillan, Tate Lodgston, Katherine Burke, Geraldine Ollivander, Gulliver Hedley

Alejandro Sundstrom, Bailey Blake, Calantha Rosier, Darcy Killick, Dorian Silvius, Elena Montague, Jude Arnoult, Marley Marsh, Mary Macdonald, Myra Yadav, Nari Mina, Ronan Prince, Slade Wixx, Tyson Huxley, William Abbington, Barbie Benitez, Shu-Hui Zhao, Damien Ricci, Alora Poverly

the following characters have a fourty eight hour extension, and have until 9:42pm nzst on sunday to post:

Ambrose Burke, Yasiel Baptist, Zehir Aydem, Kiernan Kenny, Josefina Reinhart

0 notes

Text

Character introduction: Connie

Basics:

Name: Connie Gilmore

Pronunciation: k- ah - n - ee | g- IH - l - m aw r

Meaning: Connie is an English name which means ‘constancy’ or ‘steadfastness’ (it’s ironic).

Gilmore is a reduced Anglican form of the Gaelic Mac Gille Mhoire (Scots), or Mac Giolla Mhuire (Irish). It means ‘servant of’.

Birthday: 13 June 1954

Age: 26

Pronouns: She/her

Sexuality: Lesbian

Siblings: One older brother

Parents: A single mother. Unknown Muggle father.

Other Family: None of note

Languages: English

Current Residence: Her friend Glenda’s couch

Hometown: Chicago, Illinois

Wizard Fun:

Ilvermorny House: Thunderbird

Year of Graduation: 1971 (flunked out)

Occupation: None currently

Pet: A brown rat, named Igor

Blood Status: Halfblood

Species: Human; Metamorphmagus

Patronus: Crocodile

Boggart: A swarm of bees (she’s allergic)

Amortentia: Old books. Shampoo. Chicago deep dish pizza.

Wand type: 11”, Jackalope antler core, hawthorn wood, surprisingly swishy

Affiliation: Neutral

Appearance:

Height: 5’4”

Hair Color: Naturally blonde. Hair colour fluctuates according to mood, but she favours red and blonde

Eye Color: Blue (naturally). Also varies

Typical Hair Style: Most days, shoulder-length red hair with bangs

Fashion Style: Typical muggle fashion of the period - mostly bohemian, thrifted clothes

Distinguishing Features: Varies, day to day. As a Metamorphmagus, Connie is constantly changing her appearance. However, her most distinctive features that you’ll likely see her with on the daily are the bright red hair, the up-turned nose, and icy blue eyes.

Personality: Connie comes across as a generally easy-going person. She doesn’t like conflict, nor does she like taking sides. She prefers to come across as laid-back and confident - she wants people to like her. She has a good sense of humour and has a genuine laugh that’s infectious (she snorts when she laughs). She’s always the one with creative ideas - however, she’s not a particularly hard worker, so she’s not often going out of her way to do things.

Positive Traits: + Creative + Humorous

Negative Traits: - Indifferent - Fickle

Quick Facts:

Connie is a Metamorphmagus.

She has an older brother who’s a Squib.

She is not currently on speaking terms with her mom.

She is a halfblood - mom is a witch, dad is a Muggle. She’s never met her father.

She’s not particularly skilled at magic - though she’s never cared to put effort into learning it and using it (she failed out of Ilvermorny before she could finish her seventh year). She only uses it when it’s absolutely necessary.

Connie wants to be famous amongst Muggles as a horror movie producer/director.

Her stance on the war is neutral. She could be swayed to join either side by the right person.

Theme song: “The Bidding” by Tally Hall

Headcanons:

Connie really loves disco music.

She has picked up photography and filming as a hobby, and only uses Muggle cameras.

She plays the monsters in her own amateur films using her Metamorphmagus abilities.

Connie once had a whirlwind love affair with a woman who was part-Veela. They met when she moved to London, through the gay club scene. Things ended rather horribly, but Connie still thinks about her to this day.

Connie’s hair is usually blonde and unstyled on days that she’s feeling sad, or just not feeling herself.

She keeps her wand in her boot, or stuck in her hair when she does an updo.

1 note

·

View note

Link

This is a nice thread. Mostly.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Pro-Trump Senator's Former Professor Savagely Calls Out His Hypocrisy After He Claims He's 'Muzzled' https://secondnexus.com/josh-hawley-glenda-gilmore-muzzling

0 notes

Note

........ dont pretend that nazism/white supremacy isn't hugely filled with misogyny and is not appealing to women at all. :/ dont even pretend that violence isn't primarily a white male problem. im surprised you didnt say "but muslims are terrorists too" the same way you said women are. men are like 99.9% of these people, please stop spreading lies.

I’m a historian trained in the history of the American civil rights movement. My PhD adviser is the leading expert anti-desegretation organizing in the country.

My reference to the numbers of women who were members of the KKK Women’s Auxillery comes from Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s by Kathleen M. Blee (University of California Press). A book I had to read for my doctoral comps and features on the reading lists a great many people who pass through my department heading towards PhD’s in American History.

You can find a lot of the history of how white women’s supremacy and protecting the virtue of white ladies in No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship by Linda K. Kerber (Hill and Wang).

Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South by Hannah Rosen (UNC Press) and Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 by Glenda Gilmore (UNC Press) will give you a good companion of how women and ideas about womanhood shaped the American racial system post Civil War and into the 20th century. Both books are pillars in the field.

If you want something more modern I’d suggest you look at how the blameless white mother and the ill behaved African American and Latino mother have shaped both our abortion and our welfare policy in in ways that demonize minority women and keep them in poverty Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America by Leslie Reagan (University of California Press) and Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico by Laura Briggs (University of California Press).

Or I suppose you missed my linking to the New York Times article from January of 2017 where the woman who sparked Emmett Till’s murder, a brutal killing of a child in the name of her virtue as a white woman, confessed to making the entire incident up.

White women have always … always… when given the choice chosen our skin over our gender and thrown black men and women under the bus to advance our own comfort. There is literally no example in American history that speaks against this.

But yeah. I’m lying to make white women look bad.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mass Shootings are NOT the Same as Black-on-Black Crime

There exist a disturbing trend in the media of people trying to compare the recent mass shootings with black-on-black violence.

So, since the media has a bad habit of sound biting misinformation and conflating (or at least entertaining) B.O.B. violence with white nationalist terrorism, let's do a quick history lesson to understand the differences between black community violence and white domestic terrorism:

When people (particularly non-black individuals) describe black-on-black crime, they are often referencing black violence in relation to gang and drug activity. However, when communities have limited access to employment opportunities, underfunded schools and dilapidated housing, crime rates rise.

But *concerned citizen voice* why are black individuals joining gangs and selling drugs? Well, to look at this population, we have to take a closer look at the framework of white supremacy in the United States:

White supremacy is the economic, social and political legislation that disenfranchises non-white individuals and strips them of civil liberties, mobility and opportunities afforded to white individuals. White privilege is the day-to-day benefits of that legislation.

After the Civil War, the North and South attempted reconciliation by promoting a unified front on the basis of race. This white supremacists ideology created an entirely new class purely on the basis of race. Reconstruction legislation was rolled back and, across the South, black Americans saw their budding civil rights stripped to the bone - the birth of Jim Crow and the Dixie Doctrine.

"Since the South was not sovereign, Jim Crow's health depended on the federal government's support of its administration and on positive public opinion or - at least - indifference in the territories outside of the South" (Gilmore 17). Dixie Doctrine became "white" America First policy, stretching way beyond the region of the South. 📜

(There's a fascinating history trail on how white supremacy in America influenced European empires' treatment of their colonized populations and the U.S. treatment of N. Americans and Haitians, but I'll save that for another day).

📚 Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950 by Dr. Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore (Published 2008)

🎨 Olympia, Édouard Manet, oil on canvas, 1863

Long story short, blacks found themselves not only politically and economically marginalized, but also terrorized by Southern-bred fascists, lynch mobs and domestic terrorist groups, like the Klu Klux Klan. The KKK capitalized on well-worn cookie-cutter images that illustrated black Americans as brutes, sex-crazed jezebels, thieves, and wild bucks hellbent on destroying white American families (hmmmm sound familiar?) This provided an acceptable excuse to justify the rape of black women, the lynching of blacks by white women and men, and the disenfranchisement of blacks by an entirely white political system.

🎨 Portrait of Two Society Women, Stephen Slaughter, 1740s.

Fast forwarding to the Civil Rights Movement of the 50s-60s, blacks continued to fight against tax polls and disparities existing in sharecropping, banking and unions. However, the larger white society was more interested in VISIBLE signs of ending racism: i.e. integration (put a pin in this). Integration became a cover for Neo-Conservatives in the 70s who accepted formal equality and viewed racism as individual bigotry from a not-so-distant past and, for the part, based in the South. This cover allowed white supremacy to evolve.

Integration meant black schools were closed down, or underfunded due to legislation around performance-based funding

Integration meant that black communities that used to be communities of both wealthy and working class families were now predominantly poor.

Integration saw the push out of black-owned businesses that now had to compete with larger white corporations and, simultaneously, deal with racist landlords and real estate developers.

Integration meant that without prosperous businesses, without adequate schools (not to mention continued trauma through POLICE BRUTALITY and a lack of mental/emotional health facilities) some black turned individuals turned to criminal activity. Again, criminal activity is endemic among poor communities NOT just black ones.

🎨 Portrait of an Arab (identified as Christos the Athenean), Nikolaos Gyzis, 1871.

Now compare that boatload of exposition with present day mass shootings . . .

• Who is the main demographic of shooters?

• What is their socioeconomic background?

• What political ideologies do they tend to adhere to?

• What trends do we notice in their manifestos and declarations?

This is NOT just a mental health problem. This is NOT comparable to black-on-black violence. This is an AMERICAN problem and a WHITE MALE problem that is deeply interwoven in our history, perceptions and ideas surrounding race, gender, nationalism and identity.

Since this is a lot to process, I'll save my thoughts about precarious manhood and the strain gender dynamics places on young men (and how populism and Southern-bred fascism has indoctrinated some of these men into their ranks) for another time.

BUT REMEMBER THIS!!!

White supremacy is not a vestigial, dying system; it is well-funded and it is growing. It is the legacy of our Constitution, the spark that ignited the Civil War and Civil Rights Movement and the poison that clouds the minds of these young white terrorists.

Until we own up to THAT and break the dam concealing the stain and shame of white supremacy, not a damn thing is gonna change in this country.

🎨 Portrait of the Countess Pototskaya, her sister Shuvalova with Ethiopian girl, Orest Kiprensky, 1835.

17 notes

·

View notes