#gilgamesh and huwawa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Would you be able to translate the phrase ‘it’s all happening’? I know translations aren’t always direct. It would be as an exclamation that all things planned are coming to fruition and taking place with success and abundance.

It turns out there isn't a great translation of this, because there isn't a word I know of for "happen" in Sumerian! There's no distinct word for such a concept of something "happening" or "occurring" that appears in the texts I know of. When you see such a word in a translation, it's generally a circumlocution to make a sentence make sense in English. So in Shulgi G, when "Nanna... asked for the thing to happen," what it actually says is Nanna ning al banidug "Nanna insisted (on the) thing".

In Gilgamesh and Huwawa, there's a sentence that should be helpful here: "That will happen to me too - that is the way things go." It's U ngae urgin nambaake, urshe hemea, which I'd more literally translate as "And I really am done like that, may it be thus." Baake "It is done" is a form of aka "to do, take action", using the ba- prefix (which normally means "for it" or "in it") to construct a circuitous passive. I guess we could construct a sentence like Shar baake "All (of it) is done; all (of the action) has been taken".

But to convey the tone of success and abundance, I'd probably instead opt for a sentence using sa dug "to succeed". Shar sa duge "It has all succeeded" or Shar sa e "it is all succeeding". (All these use shar "all, totality, everything".)

I hope one of these is helpful!

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

Según tú Gilgamesh, ¿Cuáles son los servant más fuertes a los que te has enfrentado?

-JA! solo uno tiene tal titulo y es Enkidu, los demás han sido un mero entretenimiento, excelentes pero entretenimiento a fin de cuentas. Aunque la lucha con el Rey de Conquistadores sin duda fue una memorable-

Porque jamas, JAMAS, JAMAS!!! va a decir en voz alta que cierto par de Berserkers lo pusieron contra las cuerdas

#anonimos#stellar golden king: gilgamesh#mientras tanto Lancelot y Heracles: MENTIROSO!!!#y Huwawa a la distancia: no viene a mi sin la muñeca#and Arturia: en una ruta me lo papee a punta de Excalibur y Avalon#y Kingu: pudo haber sido empate

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crush sent me a video of her working with the actual epic of gilgamesh at work

I have never been more attracted to a person than this moment

#you’re in her DMs#I’m pointing to lines on the actual tablet of the elic gilgamesh#discussing huwawa#e

1 note

·

View note

Text

i havent seen much talk of it here, but hakuno's myroom lines basically confirm that their original servant in gil's route of CCC was enkidu

[ID: A cropped screenshot from a reddit thread which says "Conv 7 (0:00) It's Gilgamesh, but not the King of Heroes. (0:04) Ah, I see. What Berserker said was true. (0:10) He lost his friend and his youth, but in exchange, he became the King of Men. (0:18) The long four-year period has ended, huh." End ID]

This has been a long-held theory among fans, given that when Hakuno has dreams of Gil's backstory it's from Enkidu's POV, not Gils himself like when other masters dream about their servants. Also, Hakuno's previous servant was stated to be a Berserker, which we know from Strange Fake is one of Enkidu's other main summonable classes.

Given that Hakuno in FGO seems to have memories of EVERY timeline, they appear to remember their original Berserker servant unlike in CCC itself. Here they mention something their servant had told them, specifically saying that Berserker told them about Gil's life journey in a way that would only be possible if they knew Gil personally. While Huwawa is also connected to Gil and canonically a Berserker, she didn't have any sort of long-standing relationship with Gil. That leaves basically only Enkidu for this to be referring to

So yeah. Hakuno summoned Enkidu in one timeline of Extra, then lost their contract with them and made one with Gil instead

#fate grand order#fgo#enkidu#kishinami hakuno#hakuno kishinami#fgo spoilers#gilgamesh#caster gilgamesh

216 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Humbaba's appearance ever described in detail in any written sources? When looking online, I keep seeing artists depicting him in very specific ways (head covered in entrails, scaly skin, snake phallus...), but I'm having trouble finding the sources for those same specific details

This is something I've spent quite a lot of time investigating myself last year when I was working on his wiki article. The short answer is that not really, but we can piece something together from the available scraps - and it’s not really similar to the modern standard you're describing. You are definitely looking in the right places for Humbaba information if you found no trace of these traits - only one of them goes back directly to an actual source, and even then it’s less firm than it might seem at first glance. More under the cut.

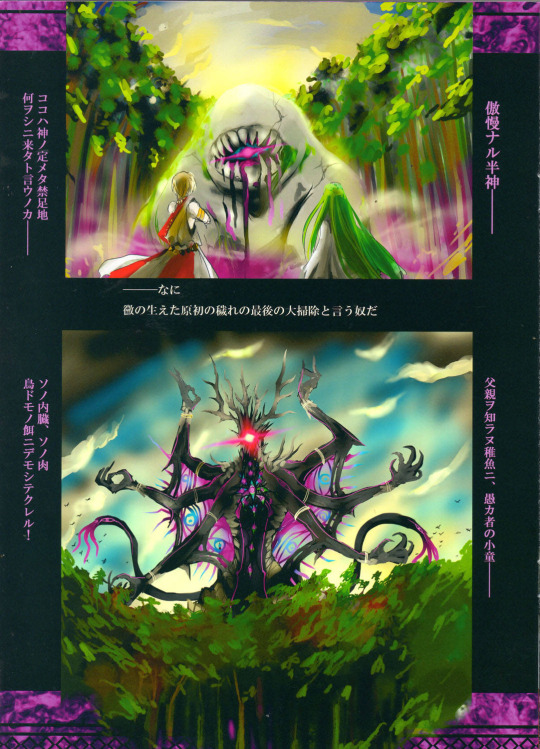

The textual sources are actually very lax when it comes to describing Humbaba’s appearance, What is emphasized are his supernatural powers and authority granted by the gods - Wer (they set this guy up like he’s the next arc villain in a shonen in the Old Babylonian version’s Sippar fragments) and Enlil or Enlil alone. There’s a decent chance he was viewed as largely human-like. Andrew R. George ( The Babylonian Gilgamesh epic: introduction, critical edition and cuneiform texts, p. 144) describes him as “essentially anthropomorphic” though speculates he might have been imagined as tree-like. Multiple considerations regarding Humbaba’s iconography can be found in the articles from Gilgamesch: Ikonographie eines Helden, especially in Lambert’s and Collon’s. Collon essentially just concludes that Humbaba was simply depicted as an unusually tall and/or broad but still largely human-like figure, Lambert notes similarities to the lahmu (so we’re still within the realm of burly hairy men, essentially). Piotr Michalowski (A Man Called Enmebaragesi, p. 205-206) argues that at least in the standalone narratives Humbaba was essentially a parody of various peripheral “barbarian” rulers. It is perhaps worth pointing out that while the etymology of Humbaba’s name is up for debate, it is clear that it was originally an ordinary personal name, and individuals bearing it appear in administrative texts from the Ur III period before Humbaba the literary character arose.

While myths and the epic itself are lax, plenty of information about Humbaba’s appearance can be found in other genres of texts. This evidence has been collected by George (same monograph as above, p. 146-147). His face was regarded as outlandish, with a bulbous nose and big eyes. There are references to diviners spotting Humbaba’s face while analyzing animal entrails. An artistic representation of this phenomenon is seemingly known from one exemplar, and is the source of “entrails-faced” Humbabas in modern work.

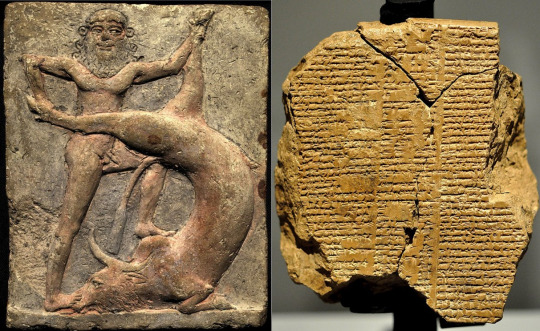

A unique sculpture from Neo-Babylonian Sippar seen above (you can view it from more sides here) is inscribed with a short formula starting with “If the coils of the colon resemble the head of Huwawa”, and has accordingly been described as the visual representation of this statement since the 1920s. Identification as Humbaba has been affirmed for example by Anthony Green in his 1997 article Myths in Mesopotamian Art (p. 137-138 + 150 for a confirmation of the museum number; published in Sumerian Gods and their Representations; you can find it online,it’s worth checking out since it also includes timeless classics like Wiggermann’s Transtigridian Snake Gods and Westenholz’s Nanaya, Lady of Mystery). I’m not actually aware of any parallels, but it’s a cool, striking visual and I personally don’t find its modern fame undeserved.

However, it needs to be stressed that it’s not standard. Humbaba’s face is also quite common in visual arts. In fact, it’s so common that Frans Wiggermann (Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: the ritual texts, p. 150) argues that the face came first, with the name perhaps representing a unique sound made by the creature while grinning or laughing (what is this, One Piece?) and only developed into a literary character later. These images served an apotropaic purpose guarding doors (examples have been discovered in situ), appear chiefly in Old Babylonian times, and show remarkably consistent traits, here are some I’ve assembled for the wiki article last year:

Scaly skin doesn’t show up anywhere as a trait of Humbaba’s, as far as I am aware. That’s Tishpak’s thing. However, it is perhaps worth noting that a type of lizard, ḫuwawītum, was named after Humbaba (George, p. 145). This was discussed briefly by Claus Wilcke a long time ago in Humbaba’s entry in the Reallexikon (p. 535); he pointed out the animal was compared to a gecko or what he identified as some variety of agamid. Not sure if anyone ever tried identifying it more precisely with any species of reptile which can be found in Iraq or Syria. Given Humbaba’s apparently outlandish looking eyes my first thought was a chameleon, honestly, but don’t quote me on that, plus note that it seems chameleons were called bargunna (or bargungunna).

As for the other reptilian matter, snake phallus is a part of Pazuzu's iconography (see his Reallexikon entry by Wiggermann, p. 377), not Humbaba's. As far as I can tell, the Humbaba plaque above is naked and shows no such characteristics. Many other possible depictions of Humbaba show him in some sort of kilt with no phallus of any sort in sight (see the numerous seals shown in Collon’s article mentioned above, for instance). I know the snake phallus claim was even on wikipedia at some point - long before my involvement - but it doesn’t come up in any publication about Humbaba I read from within the past 40 years.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dearest Enkimoots (Epic of Gilgamesh Mutuals), today I have learned that the Epic of Gilgamesh is made up of 5 sumerian poems (Gilgamesh and Huwawa; Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish; Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld; and Death of Gilgamesh) dating to over a thousand years before the full Epic (which was in Akkadian).

I know I will be reading these along with The Descent of Ishtar and Eridu Genesis (The Flood Myth), so i thought you all may also like it.

#the epic of gilgamesh#autism#enkidu#humbaba#literature#poems#poetry#history#historical lit#gilgamesh

41 notes

·

View notes

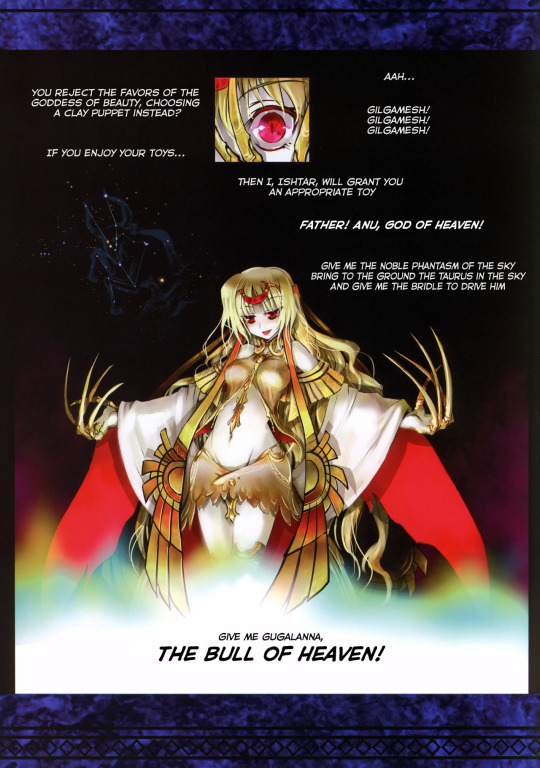

Text

So come to find out that the Ishtar design from PFALZ that got spread around isn't actually from the same doujin where Gugalanna's design comes from (sorry reignsan!). PFALZ actually made two different doujins for different monsters from the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the design that people point to is actually from the doujin for Humbaba/Huwawa and not the one for Gugalanna (Ishtar actually has a different design in that doujin!).

I think the golden skeletal parts get people confused but you can actually see the differences between the two designs here.

I think I also see the idea that this design is canon pop up here and there because of Gugalanna and to be clear, PFALZ wasn't working with Type-Moon when he created these designs. (EDIT: Unsure if I was high as a kite when I wrote this but I have no idea what compelled past me to say this, please disregard this bit) Gugalanna was designed a full five years before it would be put into F/GO but it wasn't canon for a long time. This can also be seen in the fact that his Huwawa design is also not the design Huwawa has in Strange/Fake.

(Although personally, it fucks)

It's a very interesting take on Ishtar but there's nothing to support it being canon.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Epic of Gilgamesh: The World's First Big Budget Adaptation

My Yuletide assignment this year was an excuse for me to reread (and rediscover everything I loved about) The Epic of Gilgamesh ‒ and I can seldom resist the excuse to ramble about this kind of thing, but where do you even start, with a work like Gilgamesh? It’s the world’s oldest (known) work of literature, it features an all-but-canon m/m romance, and (even from incomplete reconstructions from languages which have been dead and alien for millennia) its central themes and most striking imagery still resonate to this day.

But perhaps my favourite thing is that it’s also what amounts to the world’s first ever big-budget adaptation of an existing story, complete with extra of sex and violence, a tropey bromance between its male leads, gratuitous cameos from other popular mythic figures, and even this one wonderfully confusing deleted bonus-scene, tacked on at the end like a DVD extra. I’m not even kidding.

Let me explain.

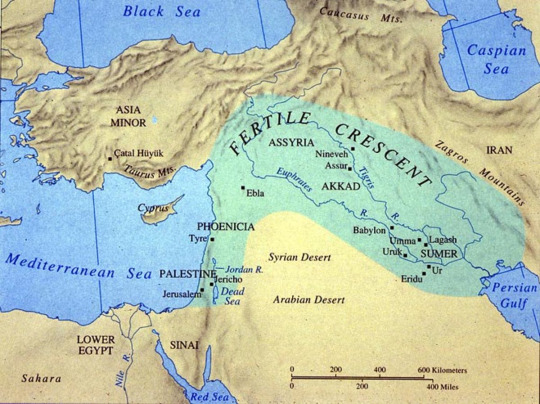

The oldest surviving stories about Gilgamesh – a semi-divine, semi-mythical Sumerian king – were inscribed on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia (modern day Saudi Arabia) somewhere around 2000 BC. Five distinct poems from this era have survived in variously-complete format. Gilgamesh and Akka tells of how Gilgamesh gained independence for Uruk from the kingdom of Kish (ruled by the titular Akka, in what seems to be the one Gilgamesh tale most likely to have some real historical basis). Gilgamesh and Huwawa and Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven both recount his battles with their respective monsters. Gilgamesh and the Netherworld deals with the death of his servant Enkidu, whose shade is briefly allowed to return to the mortal realms to report on what awaits in the hereafter. And finally, The Death of Gilgamesh deals with Gilgamesh’s death from illness, the gods decreeing that semi-divine isn’t sufficient for immortality.

But these aren’t the best-known version of Gilgamesh. A few centuries later, someone took those existing tales and reworked them into a single, cohesive epic, spanning 11 tablets (plus one confusing bonus tablet that we’ll get to later on). The new, integrated epic promotes Enkidu from merely a servant to Gilgamesh’s equal: created to be his companion by the gods, in answer to prayers of the people, exhausted by Gilgamesh’s tyrannical rule.

In all the best traditions of modern shonen manga, Gilgamesh and Enkidu meet, fight, and then become fast friends. Together, they battle both Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven, in episodes only lightly reworked from the original poems. But this time, these acts anger the gods, and their punishment is Enkidu’s death. Distraught at the loss of his friend, and faced with the horror of his own mortality, Gilgamesh goes on a quest to find the one man the gods ever made immortal: Utnapishtim, the Sumerian Noah (our gratuitous cameo). But Utnapishtim can only tell Gilgamesh that, short of saving the world from another biblical flood, his quest is a fool’s errand. Finally accepting his own mortality, Gilgamesh returns home. (This is, of course, a very summarised version of the full epic, but you get the general gist.)

Comparing the epic to the ‘original’ poems can be a little fraught, considering that even after reconstruction from multiple different partially-preserved copies, there are still gaps in both versions. We can only speculate whether there might have been other Sumerian poems that haven’t survived ‒ let alone how many other variations existed in oral tradition throughout the region and beyond. But for all the epic version adds and changes, what stands out most is how they’ve picked up and expanded on what was already the strongest running theme of the Sumerian stories: mortality – whether that be the desire to leave behind a record of great deeds to be remembered by (such as the slaying of monsters), or more explicitly in those final two poems, dealing with Enkidu and Gilgamesh's deaths.

For all that’s been added, the promotion of Enkidu to Gilgamesh’s equal does have more basis in the Sumerian originals that it might first appear. Though explicitly only 'a servant', Enkidu is the only other character appearing (or at least mentioned) in every poem, aiding his king in his struggles against Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. In sending Gilgamesh to the netherworld upon his death, the gods even note that he will be reunited with his ‘beloved’ Enkidu, whose death he so fervently mourned. And though everything else in the circumstances of Enkidu’s death has been changed, both versions render it a major event, and one that leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken.

There’s even a trace of epic!Gilgamesh’s tyranny in Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, where he so exhausts the men of Uruk with his games and contests (similar accusations to the first chapter of the epic) that the gods themselves step in, arranging for his favourite toys to fall through a crack in the earth into the Netherworld (prompting Enkidu to volunteer to retrieve them… and you can see where this is going).

But for all the adaptation takes from those old poems, some of its most striking chapters are (as far as we know) completely new – including all of Enkidu’s backstory. The Gilgamesh of the epic is still respected as a wise and powerful ruler, and he still exhausts the men of Uruk with his contests, but now, he’s also been asserting his right to droit de signeur (yes, really – that trope goes this far back), and his people aren’t happy. The gods’ solution is to make the semi-divine Gilgamesh an equal: Enkidu the wild man, raised in the wilderness by beasts. Nearly as huge and powerful as Gilgamesh himself, Enkidu soon becomes a problem for hunters trying to make their living nearby.

How do you solve a problem like a wild man? Well, obviously, you introduce him to sex.

Gilgamesh’s solution to the Enkidu-problem is to send Shamhat, a cultic prostitute of the temple of Ishtar (ritual sex was apparently a Big Thing in some ancient fertility cults) – and it works. After a full seven days of sex with Shamhat (look, this is why you send a professional), Enkidu finds he can now understand the language of men, but the wild animals reject him. Something stirs in him when Shamhat tells him of Uruk and Gilgamesh, but the tipping point comes when he learns Gilgamesh is due to make a scheduled appearance at an upcoming wedding (ifyouknowwhatimean). Enkidu rushes to Uruk, intercepts Gilgamesh on the very doorstep of the bride in question, and the two demi-gods proceed to throw down. And then become instant BFFs. Seriously, I wasn’t kidding about how very Shonen Jump it is; I don’t know what else to tell you.

Now, to what degree these new intro chapters were an excuse to sex things up and get the audience’s attention, I can only speculate – but there is a lot of sex in these first two tablets (and next to none afterwards). Regardless, this feels like the perfect place to segue into what for many will be the more pressing question: just how gay is the Epic of Gilgamesh?

Because I mean, just on a surface level, it’s already pretty suggestive: Enkidu, having newly discovered sex, shows up to pointedly cockblock Gilgamesh’s appointment with a young lady, and one round of (ahem) "wrestling" later, suddenly they really like each other. And the mere fact the gods’ solution to "this guy keeps exhausting all our men and fucking all our women!" is to send him Enkidu… you’ve got to wonder if he’s just a wrestling partner on Gilgamesh’s own level, or is he meant to satisfy other needs as well?

But you really don’t need slash-goggles to find subtext in this tale. Even the academics are here for this one.

Significantly, Enkidu’s coming is foretold to Gilgamesh in a series of prophetic dreams, helpfully interpreted for him by the goddess Ninsun, his mother. In the first, Enkidu is represented by a meteor that falls down before Gilgamesh – and to quote George’s translation directly, Gilgamesh recalls, “Like a wife I loved it, caressed and embraced it.” This is not what you'd call ambiguous wording. His mother corrects this only in that the meteor is to be a man – and to drive this point home, Enkidu spends much of the rest of the poem being described as having strength “as mighty as a rock from the sky.” If that wasn’t all suggestive enough, one might also note that Enkidu does his share of “caressing and embracing” (that same wording, presumably going all the way back to the original language) of Shamhat during their week-long sex marathon too.

Then Gilgamesh has his second dream – almost beat-for-beat identical to the first, except that now Enkidu appears as an axe rather than meteor. This is a little more confusing. Both are certainly dangerous objects which hit hard, but axes don’t generally fall from the sky, and Enkidu is never compared to an axe again. So why include it?

The most compelling (and really the only) academic explanation I’ve seen put forward is that both objects may be playful Akkadian puns. Kisru (meteor) evokes kezru, and hassinu (axe) evokes assinnu – and both kezru and assinnu are apparently terms for types of male cultic prostitute: men who have sex with other men. Lest you wonder if this might be reaching, that amazing “Like a wife I loved it” line is still right there. It all adds up.

Before we get too carried away with pre-historic queer representation though, it’s notable that even in a time where apparently no-one batted an eye at male cultic prostitutes, the Gilgamesh/Enkidu subtext would be left largely as the stuff of implication – but the pattern is also weirdly familiar. Like modern media adaptations from Sherlock to Captain America: Winter Soldier, it’s plain the screenwriters absolutely want to imbue their central male/male relationships with all the intensity and pathos (and maybe even a bit of wink-wink-nudge-nudge) of a romance, and yet stop short of making it explicit. I cannot begin to guess whether the same forces were in play here, but the resonance is still pretty striking.

We’re still not done with gay-Gilgamesh-shenanigans though, because we’ve still got to cover that mysterious, DVD-extra of a 12th tablet, which may-or-may-not include an actual, textual statement of how much Gilgamesh likes handling Enkidu’s dick.

This one is going to need some more context. See, the 12th and final tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh consists of a fairly-literal Akkadian translation of the latter half of the original Sumerian poem, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld. Narratively speaking, this is a bit of a record-scratch moment, because not only has the epic already reached its logical conclusion as of the end of tablet 11, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld is the one that revolves around the death of Enkidu – and in the new epic version, Enkidu has already died in completely different circumstances, way back in tablet 7. So what the hell is it doing here?

The best guess as to why anyone felt the need to include this episode in its original form is that the bulk of the original Sumerian poem relays a detailed account of how one’s actions in life will affect one’s prospects in the hereafter. Enkidu’s shade dutifully reports that a Sumerian citizen who hopes to be comfortable in the netherworld must have plenty of sons (to make offerings in the name of their departed father), must show respect to the gods, must die peacefully – the list goes on. The material has transcended the world of poetry and moved into scripture – and that may have been considered worth preserving long after the original tales were lost.

So where does the dick-touching come in? Brace yourselves: Enkidu’s account of the netherworld includes some graphic details about what happens to your junk. That crotch you touched, so that your heart rejoiced, is filled with dust like a crack in the ground. And so on.

Here’s where making definitive statements about this passage get messy. There are at least two different versions (the original Sumerian and the one from the epic) in different languages, and not always preserved well enough that all the words are still legible. So I’ve seen translations where it seems to be Enkidu’s own body that Gilgamesh ‘rejoiced to touch’. I’ve seen versions where it seems to be some unnamed woman’s body instead. Or maybe Enkidu’s saying that even having a wank isn’t worth much rejoicing in the afterlife (and for the record, I’ve seen all the above in just the work of just one author, Andrew George. Consensus is not a luxury we have here). There’s some ambiguity there, and I have no idea how much of that is down to interpretation, translation, or the actual state of the text. The 12th tablet of the epic of Gilgamesh remains a mystery stuffed into an enigma (then presumably filled in with dust).

Anyhow, back to the main text of the epic. From the meeting of Enkidu and Gilgamesh, things happen surprisingly fast. Gilgamesh immediately proposes a trip to the cedar forest to slay the monster Huwawa: an act which so impresses the goddess Ishtar that she hits on Gilgamesh, he rejects her, and she sends the Bull of Heaven to punish him. Angered by the death of both Huwawa and the bull, the gods inflict a fatal illness on Enkidu, whose death leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken. Like screenwriters trying to cram everything from Captain America’s origin story to his emergence from the ice into a single movie, the complete tale of Gilgamesh’s time with his literally-god-given-soulmate seems like it’s been compressed down to maybe a couple of months, max. But such is the nature of adaptations like this one.

But the best parts of the epic are hardly over. Gilgamesh’s search for Utnapishtim, the one man ever made immortal by the gods, will see him meet scorpion men and stone men, will take him across a sea whose very touch is death, and force him to race the sun through the tunnel it takes each night under the earth. He finds the man he seeks at the end of the world – which is our poet’s excuse to include the entire Sumerian flood myth in the narrative, as Utnapishtim recites exactly what he had to do to earn his immortality.

Gratuitous as it may be, this is not a complaint. I kind of love the pre-biblical Sumerian version of this story – not least because, despite being initiated by the most revered of the gods, the deluge sent to punish mankind for their ills is unambiguously framed as a mistake. Mankind is saved only because Ea, wisest of the gods, sneakily breaks his oath of secrecy by alerting Utnapishtim to the danger and directing him to build his ark – and Ea gets away with it by directing his warning not to the man himself but to the fence outside his home, so he can honestly tell the other gods “Who me? I didn’t tell anyone, I only whispered it to a fence!” (I like to imagine him walking away from that initial meeting with the other gods rolling his eyes, going, “Well someone’s gonna regret this in the morning, you just wait. Alright, alright, damage control time…”)

And the gods absolutely do regret the deluge. When at last the rain stops, and Utnapishtim lights some incense in ritual thanks to the gods for his survival, the text describes the parched gods clustering around the smoke of the offering like flies. To find something like that – that comes so close to suggesting that the gods themselves depend on humanity for some measure of their power and comfort – in a text this old blows my mind a little. It’s also a hell of an image.

In any version of Gilgamesh, the general attitude to the gods has a lot of commonalities to what you’d find in, say, Greek mythology. The gods are absolutely divine and worthy of worship, but also come across as one huge, long-running soap opera of privilege, dysfunction and pettiness. Even the Athenians, though, generally kept the image of their patron goddess Athena reasonably clean. By contrast, when Uruk’s own patroness Ishtar appears in the tale, her role is to hit on Gilgamesh, be rejected, go crying to her father for help, and send the Bull of Heaven down for revenge. Gilgamesh insults her, kills the bull, and even hurls part of its carcass at her as a parting blow. He then makes flasks of its horns and presents them to her own temple in her honour. For bonus confusion, the original Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Netherworld also opens with a passage where Gilgamesh does Ishtar a much-appreciated favour in clearing out the demons infesting a divine tree. What on earth are we supposed to make of it all? The worship of Ishtar must have taken some truly god-level compartmentalisation.

Much as I love Gilgamesh, some of it is inescapably pretty impenetrable to the casual modern reader. If you were paying attention back at that very first bit about Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, for example, you might have caught that plot point where the great king Gilgamesh so exhausted all the men of Uruk with his games that the gods themselves had to step in and take his toys away. What those toys were isn’t totally clear, but the best guess seems to be a ball and a mallet. These were made of wood from that divine tree, but even so – was ancient Sumerian croquet really that intense? You’ll run into stuff like this a lot reading any version of Gilgamesh – scholars will do their best, but some of it just doesn’t translate, reminding you you’re reading something written in a cultural context no-one’s seen in over 4000 years.

But that only makes it all the more fascinating when (like finding bits of Shakespeare in the infinite monkey cage) you run into the stuff that does still resonate. I could not tell you why Gilgamesh begins his case for why they should rebel against Kish with a spiel about the digging and/or operation of wells – but then you get to the bit where Akka compares Uruk with its great city walls of Uruk to a cloudbank sitting on the earth, or the part where Enkidu finally responds to Akka’s repeated demands of, “Slave, is that man your king?” with, “That man is indeed my king!” – and even separated from the poet by several millennia and the hard work of so many archaeologists to piece this thing back together, the words and the imagery still get me.

I could go on here. There’s so much I love in the various versions of Gilgamesh, so much that fascinates me and confuses me (and has very much tipped me back down multiple research rabbit-holes trying to get my head around it). But as both a gigantic nerd and fanfic writer, my favourite thing might still be learning just how far back the human tradition of telling and retelling old stories goes, recreating and adapting them in new formats, to resonate with new audiences. There isn’t a doubt in my head that even way back in ancient Akkadia, there were grumpy old fans arguing that this modern newfangled epic isn’t a patch on the proper old Sumerian poems – look at all the good bits they skipped and all the stuff they got wrong! Why, you realise they aren’t even teaching scribes proper Sumerian in school anymore? Pah, no respect for the classics!

Anyway, if you’ve never read the Epic of Gilgamesh in full (and it’s really not so long it’ll take you long to do), this would be my cue to recommend you Stephen Mitchell’s version as probably the most accessible English language introduction. This one is (in his own words) explicitly a version, not a translation: Mitchell isn’t a Mesopotamian scholar, but a poet, and his goal was to create something in semi-modern verse that captures as much of the original as possible in a format more accessible to the contemporary English-speaking reader ‒ patching over the holes as best as possible. And I can only applaud him the effort: after all, it’s nothing people haven’t already been doing with Gilgamesh for thousands of years.

But if you’d like to go a bit further down the rabbit hole, my other key source was Andrew George’s translation. George is an academic, and his version is a far more literal translation, preserving the gaps where we still don’t know exactly what’s missing, but including as much as possible from the various different versions which survive to us in different places – including those original Sumerian poems. Both Michell’s and George’s books are available quite cheaply as ebooks. (George’s much-longer and much-more-academic two volume work on Gilgamesh isn’t available as an ebook, alas, but can also be found in pdf format pretty easily on the web too).

Finally, I’ve got to rec you Irving Finkel’s talk on his work on even older versions of that flood myth – it’s only tangentially related to Gilgamesh, but damn, it’s fascinating too!

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i have two questions for you:

how did the hittites(?) adopt gods into their pantheon? did they change any major parts of the myths or was it just eating them whole? something else?

what was the phd-obtaining process like?

I have two answers for you! They are both long; brace yourself.

1. The short answer is: yes, they totally changed all sorts of stuff, except when they maybe didn't. The long answer is complicated and difficult, because we have almost zero examples of the original myths/rituals/etc: most of the people from whom the Hittites adopted gods didn't keep written records of their own. So we can't do a side-by-side comparison of, say, a myth from Kizzuwatna (a territory in southeastern Turkey that was conquered early on) and the same myth from the Hittite archives, because the Hittite documents are the only ones we have - the origins are lost. We also don't actually have much straight-up narrative myth; there's a lot more ritual description and incantation (sometimes involving bits of myths along the way). But! We can still work with what we've got.

So, for example, there are some rituals that exist at Hattusa in a shorter form in Hurrian (the language of Kizzuwatna), and then in a longer, modified form in Hittite. Our understanding of Hurrian is not awesome, and all of these texts are super broken and incomplete, but stuff has clearly been changed and added and moved around between the two versions. There's also a record of Puduhepa, a Hittite queen who was the daughter of a Kizzuwatnean priest, attempting some syncretism: that is, she states that the Hittite Sun-Goddess, the female head of the pantheon, is the same as the Hurrian head goddess Hebat. She just goes by different names in the different places, says Puduhepa. So here the two traditions are being fully merged.

This is a pretty extreme example, because Kizzuwatna was incorporated into the Empire quite early, and because there was a lot of intermarriage, so the Hurrian traditions/language ended up deeply interwoven with the central Anatolian traditions by the end of the Empire (at least in the upper class). There are other rituals attested at Hattusa - for example, ones with incantations in a language called Palaic - that don't seem to have been modified in the same way? We have Palaic incantations (which we mostly cannot read) bracketed by pretty basic ritual acts (offerings, libations, etc). These seem to have been adopted into the Hittite festival calendar without much modification. But we can't really know that, because we don't have the original rituals from Pala - and further, there could have been a modified Hittite version with translated incantations and we just haven't found it.

A final example is the one single text that we can compare to a native version, which is Gilgamesh! There is a Hittite version of Gilgamesh, and it is SO GREAT: the Hittites skip the whole beginning part at Uruk. They could not give LESS of a shit about Uruk. What do they care about southern Mesopotamian cult cities? NOTHING. But the bit where Gilgamesh and Enkidu come north into Syria to face Huwawa/Humbaba, up near Hittite stomping grounds, gets lots and lots of attention. Such beautiful country! Such impressive cedar trees! They really linger over it and it is fantastic.

2. The PhD-obtaining process was pretty gruelling! as PhDs always are, really. I did a combined MPhil/PhD, and all told it took eight years, which is pretty normal for the field and even kind of speedy for my university. (Though it is still longer than any human being should spend in graduate school.) First two years were coursework and the Master's thesis - I did an edition of a text for my Master's, which is like - you look at all the fragments of your text, including copies if any. (You are looking usually mostly at published drawings of clay tablets, with reference to photos where available; if you and/or your project are big and important you might go to visit some of the fragments in person if possible.) You make a composite transliteration, which is a transcription of the cuneiform into Latin script, where you match up the fragments as best you can and restore gaps based on copies if they exist, and then a translation. Then you write a commentary where you talk about any difficult grammatical stuff and say whatever you have to say about the content. If you're doing graduate work in cuneiform studies - and other kinds of philology too - you gotta learn how to do this and do a good job at it, and it is incredibly painstaking and difficult, woof.

So then! Two more years of coursework! It's a hell of a lot of coursework; most doctorates do not make you take this much. But you have to learn so many, many languages. I did Akkadian, Sumerian, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian, and then the more minor Anatolian languages (Lydian, Lycian, etc.) which are only very poorly attested and so you just kind of do your best with what's there and move on with your life. I also had to know how to read French (which I came in with) and German (which I came in with a tiny bit of) and Italian (which I did not know) for research purposes, which was extremely necessary - most of the secondary sources for my dissertation were in German. Those three languages had to be done outside of regular coursework. (Also sometimes other languages! One of my favorite grad school stories is when I was taking a class that was just two of us in my advisor's office, doing abovementioned obscure Anatolian languages, and he turned around at the end of class with two hefty printouts in his hands and said, "Do you two read Spanish?" and we were like, "no," and he was like, "Well, you're going to have to! Read this for next time," and handed us each a forty-page article in Spanish. GOOD TIMES.)

Anyway. After coursework came comprehensive exams, which are almost as fun as they sound - ours were four eight-hour tests, to be taken over seven business days, covering what we had learned in class the previous four years. Then I had to prepare a dissertation topic - this was also when my funding was starting to run out, so I had to start working as a TA and writing instructor, and as a copyeditor for a journal published out of our department. So I proposed my dissertation at the end of my fifth year, and then worked and wrote for three years, which: every year of the last three years was more difficult than any that had come before it. But then I finished! And now I am Doctor Frostfire, the end.

So yeah, it was really - it was quite tough. I don't regret doing it, but it would be hard for me to in good conscience recommend that anyone else do it, because it's really not very good for you to do all that. I was certainly in a much, much worse state of physical and mental health at the end than at the beginning. But I am very proud of it; I wrote a really good dissertation, and one of the nice things about such a tiny obscure field is that you can really witness your own impact on it, even while still a graduate student. And! I am now in a position to dispense Hittite facts basically endlessly, because eight years teaches you A LOT. Hooray!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the ancient Babylonian epic or Atrahasis. The Annunaki gods grappled with the consequences of their creation . As humanity flourished, their numbers swelled, and the incessant noise and activity disturbed the divine realm. Enli, the chief deity, grew increasingly frustrated with the humans' overpopulation and their disruption of the celestial peace. To restore balance, the Annunaki first unleashed a series of plagues and famines, hoping to curtail the burgeoning human population. Yet, humanity proved resilient, adapting, and surviving each divine assault. Enlil, exasperated, convened the gods and proposed a final, drastic measure: a great flood to cleanse the earth. Enki, the god of wisdom and a protector of humanity, secretly warned Atrahasis, a pious man favored by the gods. Enki instructed him to build a vast ark, preserving his family and the seeds of life. When the deluge engulfled the world, Atrahasis' ark weathered the storm, ensuring the continuity of life. The epic of Atrahasis highlights Annunaki's struggle with maintaining cosmic order and their drastic measures to achieve it, illustrating their profound impact on the fate of humanity. ☆ alien.related

Anunnaki gods were worshipped by Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia long before Greeks praised Olympian gods or Egyptians prayed to Osiris. While Zeus and the rest of Greek gods resided at top of Mount Olympus, and Osiris was god of earth and underworld, Anunnaki were winged deities who lived up in heavens and came down to Earth to decide on people’s destiny. Sumerians had many myths involving Anunnaki gods passing judgment on humans. The gods were described as children of the Earth and sky. This indicates they were believed to interact with humans when they came down to Earth. Based on ancient carvings depicting deities of ancient Mesopotamia, some had wings, wore horned caps, and had bird faces, while others held something resembling a modern-day ladies’ purse. Anunnaki descended from the god of heavens An and goddess of the Earth Ki. The word Anunnaki word can be translated into “princely seed” in Sumerian, but as a term, it remains poorly defined. There is hardly any evidence of an exact number of these gods and their various functions as historical texts deviate from one another. According to Sumerian beliefs, Heaven and Earth were inseparable until Enlil came along. Enlil split Heaven and Earth in two and carried the Earth away whilst his father, An, carried away the sky. Sumer, one of oldest civilizations, estimated to have existed between 4500-1750 BC. It consisted of a small number of city-states, each organized around a temple now called a ziggurat, dedicated to Anunnaki gods’ worship. Ziggurats were layered pyramids with a flat top. Archaeologists consider those communities to be “servant-slave” populations dedicated to serving temple gods. Later, priesthood rulership was replaced by kings. Babylonian cuneiform texts describe Sumerians as ancients. Despite their ancient origins, Sumerians had developed a sophisticated method of keeping time, dividing the day into hours, similar to way we count time today. They also invented cuneiform, one of earliest known systems of writing in human history. In addition, they invented plow. This played a great role in helping their empire grow. Epic of Gilgamesh; so-called Mesopotamian Odyssey begins with five short poems in Sumerian language about Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. It is known from tablets that were written during first half of 2nd Millennium BC. The poems have been entitled “Gilgamesh and Huwawa,” “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven,” “Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish,” “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld,” and “The Death of Gilgamesh.” The sophistication of Sumerians is demonstrated by a clay tablet translated in 2015 showing that ancient astronomers made extremely accurate mathematical calculations for the orbit of Jupiter a full 1400 years before Europeans did. These extraordinary advances in Sumerian civilization so early in antiquity that made some researchers doubt Sumerian mythology and extrapolate so-called ancient astronaut or ancient alien theories about Anunnaki. Fringe theorists believe Sumerian deities were aliens from another planet that ruled the Sumerians, sharing their advanced knowledge and intelligence with them. Researcher and author Michael Cremo (Forbidden Archaeology), Zecharia Sitchin, Erich von Däniken (Chariots of the Gods), author and researcher Michael Tellinger, and several others argue that Anunnaki were actually aliens posing as gods. Some of these theories also assert these aliens genetically engineered human race to be a slave species, influencing human affairs for millennia. These off-world gods brought advanced technologies that account for sophisticated megastructures such as pyramids or Stonehenge. Tellinger claimed that Anunnaki extracted massive amounts of gold using human labor and introduced the concepts of money, finance, and debt to human societies.

Source(Below)

#epic of gilgamesh#anunnaki#sumerian#ancient sumeria#ancient#culture#This is interesting!#Babylonian#myth#osiris#Egypt#Research#Enlil#epic of Atrahasis#tsubasa of phantasia concept#Tsofph Gilgamesh#tsofph season 11#tsubasa of phantasia#Ancient Aliens#Anunnaki#Babylonian Myths#Enuma Elish

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I wanna ask, what exactly measurement of "shekel" in Sumerian? The reason I asked the question is because of this passage on "Bilgamesh and Huwawa" poem

I did some googling but other than Israel currency, shekel is only appeared as measurement for weight like silver, and 30 shekels are more n less equal to 340 gr. But I don't think that measurement is ever used in liquid object like oil? (CMIIW) Also isn't 340 gr oil too much to be used only to wake up someone (but to be fair, Gilgamesh's chest was explicitly noted to be massive)? Or is that the weight of oil + cloth that Enkidu used? Or did that mean something different entirely?

Hello! The term "shekel" is a translation of the Sumerian unit ging 𒂆, which was 1/60 of a mina, and could be used for weight of any object (though silver is most common). The exact weight of a ging could vary, anywhere between about 8 and 12 grams. The phrasing in the original text is tug 30 ging ia "a cloth (of) 30 ging of oil," which means the amount of oil would convert to around 300 ml, between a cup and a cup and a half. To me that doesn't seem unreasonable for attempting to fully smother a demigod's chest in oil, not just to wake him up but to prepare him for his day - oiling of the body was a common practice, and, for example, is a key part of the "humanization" of Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Do note that the term ging can also refer to a separate unit of volume, which Halloran lists as about 0.3 cubic meters. This would convert out to about 2,378 gallons of oil, which is definitely not what's meant here.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two-sided .925 sterling silver talisman with the face of Terrible Humbaba on one side, and his epithet in Sumerian cuneiform on the other. Humbaba / Humwawa is a giant monster made by Utu the sun, and set by the god Enlil to protect the cedar forests where the gods lived. "When he looks at someone, it is the look of death."[Gilgamesh and Huwawa] "Humbaba's roar is a flood, his mouth is death and his breath is fire! He can hear a hundred leagues away any [rustling?] in his forest! Who would go down into his forest!"[Epic of Gilgamesh] Some texts describe his face as leonine, others say he is more exotically monstrous. My image is based on photographs clay figurines which were carried for protection. Each piece is hand-made, cast and finished from a mold which I also made. Each piece is unique, with unique variations in texture and finish, including some small defects which are an inevitable part of the process.

#Occult Art#Talismanic Jewelry#Witchcraft#Pagan#Jewelry#Art Jewelry#Jewelry Art#Witch Jewelry#Humbaba#Humbawa#Apotropaic#Sorcerer’s Workbench

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Gilgamesh the king came back to the city after the victory over the demon Huwawa,

he washed the filth of battle from his hair and washed the filth of battle from his body,

put on new clothes, a clean robe and a cloak tied with a sash, and cleaned and polished the weapons

that had been bloodied with the hateful blood of the demon Huwawa, guardian of the forest,

and put a tiara on his shining hair, so that he looked as beautiful as a bridegroom.

The goddess Ishtar saw him and fell in love with the beauty of Gilgamesh and longed for his body.

"Be my lover, be my husband," she spoke and said. "Give me the seed of your body, give me your semen;

plant your seed in the body of Ishtar. Abundance will follow, riches beyond the telling:

a chariot of lapis lazuli and brass and ivory, with golden wheels,

and pulled, instead of mules, by storm beasts harnessed. Enter our house: from floor and doorpost breathes

the odor of cedar; the floor kisses your feet. Your doe goats give you triplets, your ewes also;

your chariot steeds and oxen beyond compare." Gilgamesh answered and said: "What could I offer

the queen of love in return, who lacks nothing at all? Balm for the body? The food and drink of the gods?

I have nothing to give to her who lacks nothing at all. You are the door through which the cold gets in.

You are the fire that goes out. You are the pitch that sticks to the hands of the one who carries the bucket.

You are the house that falls down. You are the shoe that pinches the foot of the wearer. The ill-made wall

that buckles when time has gone by. The leaky waterskin soaking the waterskin carrier.

Who were your lovers and bridegrooms? Tammuz the slain, whose festival wailing is heard, year after year,

under your sign. He was the first who suffered. The lovely shepherd bird whom Ishtar loved,

whose wing you broke and now wing-broken cries, lost in the darkness on the forest floor.

'My wing is broken, broken is my wing.' The lion whom you loved, strongest of beasts,

the mightiest of the forest, who fell into the calamity of the pits, the bewildering

contrivances of the goddess, seven times seven. You broke the great wild horse and snaffled him:

he drinks the water his hobbled hooves have muddied. The goatherd who brought you cakes and daily for you

slaughtered a kid, you turned him into a wolf chased away by the herdsmen, whose hairy flanks,

smelly and mangy, the guardian dogs snap at. You loved Ishullanu, your father's gardener,

who brought you figs and dates to adorn your table. You looked at him and showed yourself to him

and said: 'Now, touch me where you dare not, touch me here, touch me where you want to, touch me here.'

He said: 'Why should I eat the rotten food, having been taught to eat the wholesome food?

Why should I sin and be cursed and why should I live where the cold wind blows through the reeds upon the outcast?'

Some say the goddess turned him into a frog among the reeds, with haunted frog voice chanting,

beseeching what he no longer knows he longs for; some say into a mole whose blind foot pushes

over and over again against the loam in the dark of the tunnel, baffled and silent, forever.

And you would do with me as you did with them."

The Epic of Gilgamesh translated by David Ferry, 1992

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gilgamesh and Huwawa

Gilgamesh and Huwawa is a Sumerian poem relating the expedition of Gilgamesh and Enkidu to the Cedar Forest and the slaying of the monster-demon Huwawa. The work predates and informs The Epic of Gilgamesh in which the death of the monster leads to Enkidu's own as his actions are condemned by the gods.

Face of the Demon Humbaba

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin (Copyright)

Continue reading...

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

1, 2,4,5,6,9,11,15,18,19,20,22. - para los de fate y mao mao

who does your muse hate? -Arturia: la mentira, que insulten su manera de pensar y sus creencias y morales, la mala comida, que abusen de su confianza, que la cuestionen en exceso, la traición -Gilgamesh: las serpientes, las cosas sin un propósito o valor, que desprecien su conocimiento especialmente cuando sabe que tiene la razón, ver que la gente se autodesprecia a si misma -Lancelot: a si mismo, los estándares y estereotipos sociales, que las personas no disfruten la vida sacrificadas a su trabajo e ideales, cierto doradito (?, la injusticia y cualquier cosa que vaya en contra de su código de caballería -Mao Mao: la mentira, la hipocresía, que le vean la cara de tonta, que la subestimen, cualquier contacto físico o coqueteo, no poder conseguir las cosas que quiere especialmente cuando son valiosas

how does your muse handle grief? -Arturia: por lo general ella es una persona bastante cerrada, que en fecha reciente poco a poco se ha ido abriendo con la gente. Pero aun tiene la pesima costumbre que un dolor o una pena lo guarda en su corazon, considerando que es de ella y solo de ella, a menos sea algo en exceso grave que es cuando estalla. Por regla general no le gusta la vean llorar, cuando llora delante de alguien es que es algo muy grave -Gilgamesh: puede irse a los extremos, o fingir que realmente no esta afectado por el asunto (lo cual hace casi que todo el tiempo, excepto con sus personas de confianza) o hundirse en el trabajo o las fiestas para no pensar. Igual que Arturia no le gusta le vean llorar -Lancelot: siempre fue una persona demasiado expresiva de sus sentimientos y emociones, principalmente en ataques de furia siendo que antes gritaba hasta quedarse ronco, y ahora destroza todo lo que tenga a su paso para luego terminar llorando de rabia. A diferencia de sus colegas Servants le da lo mismo si lo ven lidiando con sus tristezas o no -Mao Mao: como alguien que ha pasado por tanto dolor en la vida, el mismo la ha vuelto una persona en exceso hermética. Nunca ha derramado una lagrima en su vida y es muy poco probable que lo haga, prefiriendo enterrar el dolor en lo mas profundo de su corazón

how many scars does your muse have? Actualmente gracias a sus cuerpos de Servants, Arturia, Gilgamesh y Lancelot no presentan cicatrices algunas. Pero en vida, Gilgamesh a pesar de ser un "semi" dios, tenia una cicatriz en la espalda y otra en el pecho, ambas producto de su batalla contra Huwawa, y una menor en el brazo derecho de cuando Ishtar dolida en su rechazo le hizo un desgarrón. Arturia no guardaba cicatrices gracias al poder de Avalon que curaba automáticamente sus heridas, pero Lancelot llevo unas cuantas mayormente en el torso y piernas. Mao Mao las unicas cicatrices que posee son las del brazo izquierdo

how long can your muse hold a grudge? De los Tres Servants Gilgamesh es el mas rencoroso, aunque por lo general lo enmascara con una mueca de desdén alegando que no va a perder el tiempo despreciando pedantes que no valen la pena. Arturia dependiendo del grado de ofensa que le hayas hecho, pueden ser desde una semana hasta años. Lancelot tiende a perdonar mas fácilmente, pero eso si, si te agarra idea u odio, te va a odiar para toda la vida.

Mao Mao rara vez detesta a alguien, de hecho prefiere no hacerlo porque es perder el tiempo. Hubo una epoca que odiaba a su padre, pero poco a poco ha ido superando ese rencor, aunque prefiere tenerlo de muy lejos

how does your muse handle loneliness? -Gilgamesh es el clásico caso que detesta estar solo pero jamas lo dirá en voz alta, a pesar que entiende y acepta que hay momentos que necesita estar solo para meditar y reflexionar

-Arturia ya esta acostumbrada al aislamiento y la soledad, poco a poco ha ido rompiendo esa costumbre, pero por regla general no le molesta estar sola

-Lancelot tampoco le gusta la soledad, porque de una u otra manera termina pensando en cosas que preferiría olvidar (a pesar que al mismo tiempo el las recuerda como un castigo auto impuesto). Por eso si no puede estar en compañía de alguien sale a caminar por ahí

-Mao Mao ama la soledad, principalmente porque es el momento que puede dedicarse a sus amados experimentos de medicina sin personas molestas interrumpiéndola

does your muse think violence is ever warranted? Para los cuatro, la respuesta es SI, aunque lógicamente las circunstancias varían acorde a cada uno: -Mao Mao por lo general evitara a toda costa el camino de la violencia, lo suyo es el pensamiento lógico y resolverlo mediante el habla, pero es capaz de levantarle la mano a alguien si tiene que hacerlo

-Gilgamesh, te da tres oportunidades, y dependiendo de lo que hayas hecho o no o lo deja pasar o te arroja dos espadas por encima en señal de advertencia

-Arturia, como buena guerrera, si la provocas o! te metes con lo que es sagrado con ella, lo mas seguro es que te rete a un duelo para defender su honor, lógicamente si puedes pelear

-Lancelot, en vida buscaba resolver las cosas por la vía diplomática, y una vez agotada se iba a las manos, o dependiendo que hubieras dicho de una se iba a las manos. Ahora, no hace falta provocarle demasiado para que quiera aventarte algo por la cabeza, aunque trata de refrenarse para no lastimar a nadie

what would your muse consider their worst failing? Mao Mao trata de no centrarse demasiado en sus fallos y errores, ella prefiere verlos como una experiencia de aprendizaje

-Gilgamesh, aunque NUNCA pero NUNCA pero NUNCA lo dirá en voz alta…admite que su peor fallo fue ser padre, porque considera que Ur-Nungal es el producto de todos sus errores, tanto el modo en que lo concibi�� como la manera en que "lo crió", preguntándose mas de una vez si el chico no hubiera estado mejor bajo otra familia, viendo en el joven todos los errores e idioteces que el mismo cometió de joven, a sabiendas que fue culpa exclusivamente suya

-Arturia, a pesar que en cierto modo supero los cuestionamientos hacia si misma, y esta consciente del gran legado que Camelot dejo para la historia, todavía a veces piensa que su peor error fueron sus decisiones como rey

-Lancelot sin duda fue haberse enamorado, aunque una parte de si sigue amando a Guinevere, la otra parte se lamenta en primer lugar de haberla conocido, alegando que si iba a sufrir por amor prefería no haberse enamorado jamas, y todo lo que le costo a su reino por su propia estupidez

what might others consider your muse’s worst failing to be? A cualquiera que los conozca que les pregunten: -sobre Gil, sin duda la época en que fue un rey tirano, para muchos ese fue el peor error de toda su vida -Arturia, ser una mártir que jamas se permitió un deseo o pensamiento para si misma, sacrificando todo en pro de su pueblo sin tomar en cuenta el como se sentían los demás -Lancelot todos los errores que cometió a raíz de Guinevere, muchos creyendo que lo mas sensato era, si no podía dejar de amarla, haberse ido de Gran Bretaña

-Mao Mao…nadie puede decir alguna falla de ella, porque realmente es difícil definirla a ella como un todo en palabras. A lo mucho que es una jovencita muy intrepita

does your muse suffer from nightmares? how often? what about? como Servant, Gilgamesh sufre muy pero muy pocas pesadillas, se podría decir que casi nada, pero en vida las sufría bastante, la perdida de Enkidu, su fallido viaje, el miedo a la muerte. A pesar que con el tiempo fueron disminuyendo, no dejaron de atormentarle durante toda su vida

-Arturia en vida sufría de vez en cuando de la misma pesadilla, ella viéndose devorada por un dragón, creyendo en principio representaba a su tío Vortirgen, pero en realidad se trataba de ella misma, de su eterno miedo constante a fallar y con ello la caída de su reino. Como Servant en cambio, mayormente se trata del momento que se vio obligada a destruir por vez primera al Santo Grial, y en menor medida, cuando creyó perdería a sus amigos en la Quinta Guerra, siendo que las sufre de manera esporádica

-Lancelot es el que sufre de mas pesadillas, producto de su mismo sentimiento de culpa, optando por a veces pasar días sin dormir. Esto ya lo sufría desde sus últimos años de vida, siendo que antes de su relación con Guinevere, de vez en cuando tenia pesadillas de perder a Arturia o alguno de sus amigos Caballeros

-Mao Mao en esencia es la misma pesadilla, y solo si y solo si! le tocan el tema de sus padres, del resto duerme tranquilamente

out of everything your muse has lost/given up, which hurt the most? -Mao Mao hace tiempo acepto la realidad de su familia, incluso diciéndose a si misma que ella nació sin la capacidad de amar, aunque sabe que no es cierto o si no no amara a su padre adoptivo. Así que para ella no ha perdido nada

-Gilgamesh es otro que no se arrepiente de las perdidas consecuencias de sus acciones, sabiendo que todo había tenido un porque y una razón. Excepto Enkidu, aunque esta consciente que sin la muerte de Enkidu no habria hecho tal viaje que le permitió descubrirse a si mismo y crecer como persona, no significa que lo acepte, es mas, quiza nunca llegue a aceptarlo. Especialmente por las consecuencias que trajo su fallecimiento…y en cierto modo haberse resignado en vida a que su relación con Gal nunca seria como el realmente la hubiera deseado, aunque al final de sus días ambos hubieran llegado a una relación cordial

-Aunque Arturia al final de la Quinta Guerra acepto renunciar para siempre a su sueño del Santo Grial, no significa que deje de dolerle, aunque no lo exprese en voz alta, especialmente cuando ve a su amigo todos los días

-Para Lancelot, las perdidas que vivió aun le siguen doliendo en carne propia, a pesar de haber conseguido su mayor deseo que era el juicio de su Rey durante la Cuarta Guerra

what is something your muse wants to tell others, but is too afraid to? -Mao Mao no tiene reparos en decir las cosas de frente…salvo cuando se trata de la dueña de la Casa Verdigris, su "abuela", a quien se cuida de decirle algo si no quiere afrontar las consecuencias

-Irónicamente, Gilgamesh mas que miedo no sabe como decirlo, especialmente luego de haberle dicho en sus primeros años de infancia que deseaba se hubiera muerto, y siente que decirlo ahora seria una hipocresía. Pero es un simple lo siento a su hijo, aunque suene insólito de parte del Rey de los Héroes. Y lógicamente nunca lo dirá

-Aunque en la actualidad Arturia esta siendo mas honesta respecto a expresar sus pensamientos, todavía le cuesta mencionar en voz alta respecto a sus pensamientos y sentimientos mas profundos

-En vida, a pesar de por regla general decir las cosas directamente, hubieron cuestiones que por miedo Lancelot se cuido muy bien de decirlas, principalmente para no lastimar a sus amigos y camaradas. Pero ahora como Servant no tiene miedo de decir y expresar lo que piense, y si no lo dice es por mera cortesía

looking back, what is one thing your muse wishes they had done differently?

-Mao Mao no tiene ningún tipo de arrepentimiento de su vida, esta satisfecha como se han dado las cosas, porque a pesar de todo no le falto en cierto modo el calor de unos padres, así fuera de manera totalmente atípica. Es mas, ella lo ve como ventaja porque le enseño a ser independiente en la vida.

-Para Gilgamesh, es el tema de su hijo, aunque de nuevo, jamas lo dira en voz alta. Siendo alguien que le gustaban los niños, se imaginaba sus futuros herederos concebidos y criados de manera distinta

-Y en el caso de los Caballeros de Camelot, mejor no le toquen el tema, que aunque a Arturia le duela menos que en el pasado, sus errores siguen siendo una llaga en su corazón. Ni hablemos de Lancelot, que ha tenido días en que ha llegado al extremo de desear jamas haber salido del Lago Nimue para convertirse en Caballero

#headcanons#stellar golden king: gilgamesh#stellar king of knights: arturia#stellar black knight: lancelot#stellar medicine flower: maomao#me llevo un buen y me falto rin xD!#pero bueno aca le di la oportunidad a los 3 bebos

0 notes

Text

Máscara de argila Humbaba (ortografia assíria) ou Huwawa (ortografia suméria) para uso na adivinhação (De Sippar, sul do Iraque, cerca de 1600-1800 AEC.). A máscara é feita de intestinos enrolados representados por uma linha contínua. Um método para prever o futuro na antiga Mesopotâmia foi o estudo da forma e da cor dos órgãos internos de um animal sacrificado. O especialista em adivinhação que fez a máscara é chamado na inscrição como Warad-Marduk. Uma inscrição cuneiforme na parte de trás desta máscara de argila, sugere que os intestinos podem ser encontrados sob a forma da cara de Huwawa nesta máscara. Huwawa (também chamado de Humbaba em alguns textos) era um monstro que aparece na Epopeia de Gilgamesh. Ele era guardião da Floresta de Cedros (provavelmente referindo-se ao Líbano na versão final do conto), mas foi derrotado por Gilgamesh e Enkidu. Ela foi encontrada em Sippar, o centro de culto para o Deus-sol Shamash.

Sobre a prática da adivinhação como parte do ofício profético no antigo Sudoeste Asiático, adquira o Curso “Profecia em Israel e em Judá”

Para informações e inscrição:

Se você deseja explicação, orientação, recomendações bibliográficas personalizadas ou aulas específicas, entre em contato pelo e-mail [email protected] e solicite um orçamento. Terei prazer em atender, esse é o meu trabalho. Não atendo através de minhas redes sociais. Valorize o trabalho de professores. Hora/aula - R$ 100,00 Pacote de 4 horas/aula - R$ 300,00 FORMAS DE PAGAMENTO: 1. Pix: [email protected] 2. PicPay: @angelanatel 3. Mercado Pago: link.mercadopago.com.br/angelanatel (nesse caso acrescentando 5 reais ao valor total) 4. PayPal - [email protected] (nesse caso acrescentando 7 reais ao valor total) 5. PagSeguro: 1 hora/aula - https://pag.ae/7YYLCQ99u Pacote de 4 horas/aula - https://pag.ae/7YYLEGWG8 Sobre mim e meu trabalho: https://linktr.ee/angelanatel

0 notes