#gif essays

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#blackandwhite#b&w aesthetic#b&w sexy#lesbians#girls who like girls#girls who love girls#lesbianism#mine#love#essays#writing#writing life#girl thoughts#girl blogger#girl blogging#girl things#girlblogging#just a girlblog#funny post#art#classical art

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The screen I spend the most time with these days is a black LCD monitor attached to a PC in an indie bookshop on Long Island. I spend whole days looking at point-of-sale software called Anthology which also keeps track of the store’s inventory. Often, it’s accurate. Occasionally, it says we have three copies of The Bell Jar that have simply disappeared from the face of the Earth. No one stole them. They were raptured, like socks that never make it out of the dryer.

If you’ve never worked a retail job, let me tell you what it’s like: you come in with a little spring in your step, caffeinated, and ready to greet your coworkers and update them on how terrible your last shift without them was. Though the memory of the previous shift’s slog might give you a little anxiety, and though a hangover can make your fuse a little short, you’re in a better mood at the start of the day than at the end. Tedious tasks like ordering and unboxing books (sci-fi movies did not prepare me for how much cardboard there would be in the future) seem manageable in the morning. Customers seem kind. The items you’re selling feel necessary to human happiness. Whatever is going on in your life is put on pause to manage store operations, and time flies. Then, by 3 PM, whether you had time for lunch or not, you wish you had done anything else with your day — or, better yet — your life.

While the back-straining work of moving inventory around the store or walking the floor helping customers all day without a second to sit down might make you physically tired, the real work of retail is mental and forces employees to become part-machine. Retail workers have to ask the same three questions (“Rewards?” “Bag?” “Receipt?”) and reply to the same three questions (“Have it?” “Bathroom?” “Manager?!?!?”) for 8-10 of their most worthwhile waking hours.

In bookstores, there is the added expectation that while you’re participating in this mind-numbing routine, you’re at least able to pretend to like and engage with literature. I'm not arguing that people working at Old Navy aren’t eloquent or as over-educated for their job as I am. If they aren’t teenagers, most retail employees I’ve encountered have, by virtue of talking to coworkers and customers all day, the same high emotional intelligence as the smartest people I know who chain smoke outside bars. Still, my guess is that it’s rare for a customer to see a clothing store employee folding clothes, and think “I wonder what their opinion is of the latest Ann Patchett book” or “I wonder if they read Knausgård and run a book club when they’re not helping me find jeans in my size.” People see booksellers doing the same tedious tasks as any other retail employee and assume they not only possess unlimited knowledge about the state of publishing but also have unlimited hours to read while in the store. Customers hold booksellers to an impossible intellectual standard. When they fail to live up to said standard, they’re subjected to conversations like this:

“You haven’t read the latest Kingsolver?” a customer will ask, “Why not? What about this one? Or that one? It’s so good though! I thought you would have read all of these!”

What’s a shame is that they think they’re being kind when they half-recommend, half-admonish bookstore employees. Worse are the people who are flat-out rude. Case in point, a man came into the store at hour six of my shift, and without any preamble, treating me like I was a human Google search bar, said the name of an author, then started spelling the name. When I asked for a second to look up what I assumed he was asking for, he rolled his eyes and began spelling slowly and loudly: “PAUL. P…A…U…”

Sadly, I’m too old to be treated that way and without thinking I raised my hand and said sternly “Don’t do that.” Now some oblivious retired banker is walking around Long Island asking himself why indie booksellers are so mean. My Midwestern niceness has disappeared, my helpful attitude is now nonexistent. I have been worn down by the people I’m paid to be kind to.

Read the rest here.

#lit#lol#humor#funny#essay#essays#bookselling#barnes and noble#reading#writing#customers#american fiction#books#literature#better book titles#dan wilbur

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I should be working on my history essay rn. And yet…here I am…posting memes…someone please kindly yell at me in the comments or rb tags to get working on my history essay. Thx! ( :

#adhd problems#i should be doing homework#essays#finals week#history essay#please yell at me#But like respectfully tho#Like aggressive encouragement or something#y’know?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading BioShock: Rapture (Part 6: Frank Fontaine: Funny He-He Clown Man)

<- Part 5: Three Old Men Jerking Their Milk Sticks || Back to the Beginning || Part 7: Shadow Eve ->

By Chapter 2, Shirley finally introduces a few antagonists—Fontaine, as well as G-men doing the world’s worst surveillance.

If you’re hoping for tension,

stop.

hope is a lie and this book is its grave

I Would Like to Feel Anything Please

This chapter opens on Sullivan trying to shake a G-man and failing. Apparently it doesn’t matter because he goes ahead and meets with a character called Ruben Greavy, head engineer for the Wales brothers. I’m assuming that Greavy was originally the city designer before Wales & Wales had to be worked in.

I was most interested in the G-man because I keep looking for antagonists. Ryan has a goal, right? In literally any story anywhere, there would be obstacles the protag has to overcome. One might reasonably conclude that government institutions are Andrew Ryan’s greatest foes. They have the power to stop him through legislation and force: it doesn’t matter how much money you have if your enemy can mobilize the fucking Army.

Who else has the power to stop Ryan? Probably other industry tycoons. In Ayn Rand’s fiction, company presidents commonly ally with each other and the government to stymie the goals of her Ubermensch.

Although present, Fontaine is a small-time crook and motivated in other directions and is thus a non-issue.

As it turns out, I shouldn’t have been excited to see the G-men. After info-dumping a thousand things we either already know or could read in more interesting ways, Sullivan says this:

“Maybe they’ll get a warrant after all. I don’t think they’d find anything illegal.”

So you’re saying there’s no threat.

We are in Chapter 2, on page thirty-fucking-nine, and THERE ARE STILL NO STAKES.

But Preferably Not Indignation

At this point, it’s not about not knowing who Ryan’s enemies are. Functionally, I don’t think they exist. While Shirley invokes entire government institutions, like the FBI or IRS, they literally have nothing to do and no reason to be there.

Moreover, the Olympian—Ryan’s yacht—is namedropped. Which is when I realized that it was being used as a cargo ship.

Wait a fucking minute.

Look, I don’t know shit about boats, but can you really use a yacht like that? Like to ship big ol city parts? Why would you do that? I mean there’s a certain poetic quality in, say, stripping the guts out of your pleasure yacht to bend it to base labor, but we all know Shirley didn’t think that far.

(grumbles to self. angrily notates “research midcentury yacht models and cargo ships”)

Salty — Today at 10:22 AM No, yachts can’t be used like that watchword — Today at 10:23 AM "I found this out in 1 minute Shirley" thank you I figured the design mattered Salty — Today at 10:23 AM It does You’d need some kind of crane to lower things into the water and there’s no way a yacht could take that shit without being built not like a yacht

So it turns out that Andrew Ryan has sent his chief of security personally down to the docks to confirm the time it leaves like he’s some kind of little messenger drone. Somewhere in the proceeding info-dump, Sullivan tells Greavy to leave with all of the building supplies in his ship as soon as possible in case the G-men want to raid them, even though there’s nothing illegal going on. Their reasoning is that they don’t want the US government to learn even a scrap of information about what they’re doing.

Or what? What would they fucking do? There are no laws about shipping out giant city parts. I suppose it could be framed as Ryan being paranoid, but Shirley always explains what characters are doing to the nth degree, and there’s no such explanation here.

Also, and I don’t know why this isn’t being used: the world was fucking flattened after World War II. Shipping building supplies makes a lot of fucking sense. Just tell the gubmint that you’re selling them to France or something. “Aw, yeah, Uncle Sam. You know how much the French like glass tubes. Gonna put all the filthy tourists in there like hamsters so they don’t touch anything. When you get troublemakers you just close the bulkheads and fill them with water.”

Besides, all you have to do is tell the gubmint what you’re shipping off with. It’s for records to be checked against the port that receives the shipment to make sure there’s no funny business. What I don’t remember is if you have to declare what port you’re going to—I suspect that would be the case—but I mean. LIE? This is your life’s work. LIE.

Finally, New York is one of the busiest and biggest ports in the nation. Why would anyone be looking that closely at one more cargo ship? Paperwork back then was even more annoying and difficult to grok than it is today. Imagine the volume for a port like New York’s.

Just fucking LIE.

The real point of this scene is so there can be an exposition dump. Shirley couldn’t just send a messenger who didn’t know what was going on—he needed two people who were In the Know. The important part isn’t entertainment, it’s information: unnecessary and uninteresting exposition about Rapture’s political and economic goals, why they’re shipping supplies the way they are, and the US government, all despite the characters involved being intimately knowledgeable of the situation. Also, they’re about 75% through with the entire escapade, so if this conversation ever occurred at all, you’d think it would be months in the past. The G-man is an attempt at escalation, but then Shirley immediately de-escalates by saying he’s powerless.

So, just to reiterate:

Sullivan tries to shake a tail, fails, and doesn’t care because it doesn’t matter. He shows up at a ship containing building materials for Rapture, meets Greavy, and they lecture each other back and forth about subjects they should already know to summarize a bunch of events we should have seen. As an afterthought, Sullivan tells Greavy he showed up in person to confirm the time the ship leaves instead of calling because the phones are probably tapped. Sullivan will leave before the ship leaves so he won’t actually know the time to confirm with his boss. This particular ship is one of multiple ships and represents only one of multiple shipments—there’s nothing remarkably special about it. They’re not in any danger in any way and there’s nothing the USA can do legally to stop them. End scene.

How the hell is anything this bad.

How.

There should really be like twenty chapters for every one of BioShock: Rapture’s, each explaining how we got here. Because instead of sharing the exciting cat-and-mouse shit, Shirley writes about the outcomes where everything is settled.

This is how our reflections write in the mirror universe.

I have read fanfiction by fans of every age and fluency level and ability. Most of it was trash, but it could be excused because they were young or new or amateur writers, and even then, they’re often excited about a concept and trying really hard and might have some neat thoughts to share.

This… this is on a whole different level.

Writing Is Hard (and Caring Is Harder)

The reason for this is, of course, that Shirley would have had to research several different subjects to write about them in any depth, and time was of the essence. In fact, I am now 100% convinced that everything here is done in a mad effort to save effort, which sounds as delightful as it is.

The elements he thinks to research are absurd. I am now sure that he doesn’t know how to rank research subjects by importance. He does not research, say, the histories of the IRS or the FBI or corporate espionage. No, he researches “how to install a toilet” and “historical boxing.” He’s most often focused on physical processes or what things look like—not on what people do or why they do them.

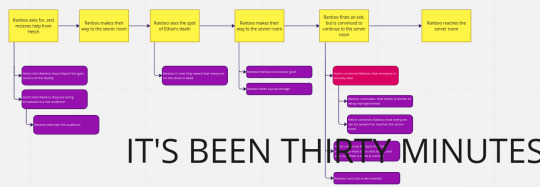

I have a new bet for you: that each chapter will be like a little push-pin in a plot point. None of them will be married meaningfully to any of the other plot points. They will be little islands in time and rely on the reader to insert connective tissue. This will essentially be a disjointed short story collection, except without any tension whatsoever, because they’re just summaries of larger stories that we never see.

Shrug

Let’s contrast this burning sludge puddle with a different burning sludge puddle: Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. This is a fitting contrast as Rapture is a callback to Galt’s Gulch.

The protagonist, Dagny Taggart, discovers Galt’s Gulch (libertarian paradise and Aryan summer camp) in Part 3, roughly 60% through the book. In my paperback, Part 3 begins on page 643, and the story ends on page 1,069 (nice). The font is like 6 points. I can’t stress enough how dense this book is.

Rand spends ungodly amounts of time and detail lingering on her enemies—politicians and company presidents and whiny family members. She waxes eloquent on the destructive side of selflessness. Over the course of an eternity, she displays in slow, evolving detail how that world fucks her characters over, despite all their best efforts. And oh—they struggle. They fight!

When Dagny ends up in Galt’s Gulch, staring straight into the face of Objectivist Jesus, she has been through hell, and it feels like a relief: like she’s finally free.

Galt’s Gulch was not a given—it was a process.

Rapture deserves the same build-up. The build-up is the story, you understand?

BioShock: Rapture is like a romance novel that skips all its character building and sex sequences to leap straight into post-coital snuggling. It’s not half as interesting or meaningful if you don’t include all of the pining and rage and frustration and explicit dicking.

Funny He-He Clown Man

Oh, Frank Fontaine. They done did u dirty.

Hey, hypothetical reader, I’m gonna ask you something: what do you think when you hear "Frank Fontaine"? Do you think of a funny little clown man who changes into costumes every ten seconds like a malicious Bugs Bunny? Because that’s what we have here. And, like everything else in this shapeless abortion, I hate it.

Generally, when I write a character who’s not my own, I say: “What is most interesting about this guy?” And I go for some neat character trait or behaviorism and then expand. Everything about that person fractals off of their base personality, psychology, behaviorisms, internal worlds, and past experiences.

Of course, that character doesn’t exist in a vacuum, so you know what else I do? I look at how they’re utilized in the source material, I ask what exactly the source material is, and I examine what the story was originally trying to do.

Characters Are Limited

Since the Beginning of Time, it has been popular in fandoms to act performatively enraged about how each and every character in a piece of media is not fully-fleshed out and explored to the last quark of the final atom.

First, that’s not how narratives work. Stories have to be limited by their natures: we are limited to this time, this space, this person, these concerns, these events. Material can only stretch so far, and characters can only intersect so long. It’s impossible to touch on every single concern and detail of your world, and if you attempt it, you’ll carefully hand-craft an unreadable clusterfuck.

Second, a character is not a person. A character is a slave to the narrative. They are an ingredient and a tool. Even if they’re the complete focal point of the story, you cannot possibly fully explore them. They do not have full human lives or sapience. They only have what they are given. As inhuman objects and creative constructs, they are also not worthy of the same respect as a real human being. can you believe I have to say that

Third, it’s not important to have a fully-rounded character because that’s not always what the story requires. There are all kinds of different stories outside of character-driven ones—for example, focal points might be on themes, ideas, settings, or vast periods of time, and not on people at all; sometimes the narrative as a whole is more important than the characters inside of them; sometimes the style and POV limits how much we can know; sometimes it’s simply more entertaining or informative to omit certain information; and so on.

There are many ways to be interesting, and there are many ways to string along a series of plot points, and characters are just more tools in the toolbox. Instead of raking a narrative across the coals for not meeting your standards, it’s far more sensible to ask what the narrative is and what it’s trying to do, then judge it according to the standards it was trying to meet.

The Fountainhead

Sometimes a character works best if we don’t know that much about them. In my opinion, Frank Fontaine is one of these. He has a limited efficacy and only in specific situations.

How is Fontaine used in BioShock? Sparingly, that’s how. And when he finally shows up as ringleader, it’s to head what is arguably the weakest part of the game. Suddenly you have to look straight at him for a couple of hours, and he’s just not that interesting under a spotlight. He’s a small-time crook who won the lottery; what made him interesting was the Atlas con and his friction with Andrew Ryan, and both are over. He’s not that big of a deal in and of himself. He doesn’t really have any power other than ADAM—and of course, that’s the point.

Fontaine is not a character with an arc. He can’t change and he wouldn’t work very well if he did. In fact, he’s not really a character at all—he’s an anthropomorphized human quality. One of the alternate meanings of “frank” is “honesty” or “truth”; “Fontaine,” or “fountain,” probably refers to Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

“What is the fountainhead—the source—of the Ubermensch?” Rand asks.

Levine replied: “What is the fountainhead of Objectivism?”

If Objectivism got everything it wanted, what would its world really look like? Because it wouldn’t be Galt’s Gulch or Rapture in its heyday.

Frank Fontaine is the ultimate culmination of Objectivist theory—not Andrew Ryan. The guy who wins doesn’t have to have any laudable moral qualities at all—all he has to be is the strongest or most cunning. The best idea or product doesn’t necessarily succeed because Objectivism isn’t about quality—you can just get steamrolled into bullshit because some company has more resources and social currency than the innovative little guy. If all you value is strength, all you will receive is the strong, and that strongman does not have any incentive to be anything other than a flesh-tearing, blood-drinking brute.

One of BioShock’s best qualities is how it just lets Fontaine sort of exist quietly in the background, like the faint, tense hum of an electric wire. You see evidence of him. You see what people think of him. But you never actually see him. The mystery is part of his power. Pre-twist, you only hear his voice once, and it’s probably utilized as a red herring in case you started to doubt Atlas’ identity. After all, Atlas is Irish, and Fontaine is from New York or something! You can trust Atlas!

But Can You Trust Shirley?

what the fuck do you think

I thought of just ending here and letting you figure it out but I believe this deserves just a little explication.

In Chapter 2, Fontaine—going by the surname Gorland—waltzes in, front and center, and with all the flare of a supervillain descending from on high, steals some loser’s shitty-ass bar.

“Whatta hell ya mean you’re the owner, Gorland?” … “…You’re about to sign this bar over to me, is whatta hell.” … Merton stared at the papers, eyes widening. “That was you? Hudson Loans? Nobody told me that was—” “A loan is a loan. What I seem to recall is, you were drunk when you signed it. Needed some money to pay off your gambling vig. A big fucking vig it was too, Merton!”

Fontaine got a guy drunk and made him sign something. Is this supposed to impress me?

I cut a ton of needless bullshit out and I still didn’t cut as much as I should have. (A “vig” is a gambling debt, so “gambling” is redundant, among other things.) What shitty dialogue this is. I told you, McDonagh isn’t the only one you should be cringing at. Shirley is terrified you won’t understand him so he makes sure to explain every point three times over.

When Levine writes “CIA spook” or “das vedanya,” it’s not to prove his work. It’s there because it makes sense there. When Shirley uses a specific term, it’s to show off. It’s like a little kid running up to show you that he finished a question on his homework. Except he does it every time he finishes something. And he’s always wrong somehow.

“Vig” in particular got me.

“Vig, you know! Yeah I looked it up! Vig! A gambling debt! Bet you’ve never heard that before! I researched! See! Vig!”

I will find your thesaurus, tear each page out one by one, and eat them in front of you without breaking eye contact. You will see me when you get up at midnight for a drink of water, slowly crunching in the dark. When you call the police I will evaporate. All that will be left is the hardcover, tented over a single dead roach pinned to the floor. At night you will hear me whispering from the walls: “haaaaaaaack”

Cynicism, Nihilism, Gnosticism, Humanism

Frank Fontaine is the most cynically written of all the characters thus far. He’s the one with the most obvious To-Do List.

“What do I need to establish about Frank Fontaine?” Shirley asked himself. “Let’s see: he is a conman. He is a great actor. He needs to find out about Rapture and get there somehow. He’s a super-awful guy. I should establish his background, motivations, and how he learned his skills. I know! He lived in a vaudeville theater!”

All right, all right. Let me be fair. I would bet money that Levine is the source of that background bit—BioShock features a million stages for a reason that I will someday write about at length—but god I hate it. I was in one-act play and I have watched hundreds of films but it doesn’t mean I know how to act. Isn’t it enough that Fontaine learns to manipulate others, perhaps out of a sense of childish self-preservation before evolving into predation? Does it have to be a big show?

…yes, I guess. Fuck. Because gnosticism.

Gnosticism is one of those BioShock themes that I least expected in this novel because it is a pure thought exercise and exists on several metaphorical levels. I’m sure Shirley has been informed of its existence, but we all know how he’ll handle it (he can’t lol). All you need to know about gnosticism is that it’s a philosophy that believes the physical environment is a broken copy of a higher reality. Even though the physical realm is fucked, it can still point toward a higher truth. In other words, you can learn from the physical world’s half-truths to achieve gnosis—knowledge of that ultimate spiritual truth—and thereby ascend to that higher spiritual plane.

But Ken Levine has a different take on ascension.

According to Levine, you learn by going through the horrors of life, but the truth is not some beatific vision. There is no god and there is no better world: there is Only Man. All you learn is that human beings hurt each other, and that they won’t ever stop, and to survive, you must go to war yourself—whether you like it or not. In the process, you struggle toward an understanding of how to make a better world, but there’s a catch: you have committed all kinds of harm out of ignorance. By committing that harm, you have ensured that the damage goes on… and on… and on.

No human being can avoid this.

Nobody can just TELL you how to make a better world—it’s far too big and complicated a place, and it’s always changing. You have to experience it for yourself to understand how it works. That means you can’t take your knowledge to others, either—because not only can future generations not understand you, your own knowledge is highly individual, and the world is continually changing so that you’re always one step behind. Future generations have to make their own mistakes in their own unique settings to figure out how best to live. In the process, they fuck up the future in a whole new way.

Everyone thinks they’re going through hell looking for heaven, but it turns out it’s always been about this fucked-up world and this fucked-up present with its fucked-up people. All you can do is your best with what you know.

The way Levine illustrates this is that art and artifice performatively point toward that ultimate higher truth: there is no escape, and we are destined to hurt ourselves and future generations in an unbreakable cycle. BioShock is existential horror at its heart, and it’s the best kind—the humanist kind.

So, thematically speaking, Fontaine being a literal performer, acting for our education and elevation, is correct. If you pay attention to the game, every character functions this way. Everything is a performance for your benefit as player. I have to admit that it makes sense. Plus, other than working retail, entertainment is a great way to learn how to hate the human race.

I still hate it. I want Fontaine to be more grounded, I guess. Every time I imagine him in a theater I cackle a little.

Cardboard People

Returning to BioShock: Rapture, the first problem with Fontaine’s section is that he doesn’t feel like a person. I don’t get a sense of his past, even when it’s explicitly mentioned. I bring up Fontaine’s past because people do what they do based on a complicated play of psychological need and lessons learned to survive past environments.

Alas: Fontaine is a one-note mustache-twirler. He wants to get money why? To get more money. Not to survive, not to defy the privations of his past, not to take vengeance on an uncaring world, not to bang girls, not to buy cool shit. He just fucks people up because that’s what he does.

Also, despite being a petty criminal, he seems above and beyond the law somehow. I’m not afraid for him when that G-man from earlier walks into his bar.

…oh, for fuck’s sake, that’s still my optimism talking. I keep expecting this book to work like a book. This thing is the hairy knot you find at the bottom of a drain.

Anyway, the second problem with Fontaine is that the entire story works to his benefit, and it’s immediately ludicrous. Instead of giving Fontaine problems to solve—and giving Andrew Ryan ways to work against him—you know, like real human beings with brains—Shirley just throws information and idiots at Fontaine constantly.

Allow me to illustrate.

Frank Fontaine gets his bar by drugging a guy who is dumb with or without intoxication. Fontaine wanted this bar so he could listen into bar patrons’ conversations for hot tips on gambling and grifts. When does this pay off?

guess

If you said, “Immediately!”, Fuck You! You are correct!

[Fontaine] wiped at an imaginary spill on the bar, edging closer. “But can we count on Steele?” said the one some called Twitchy. He twitched his pencil-thin mustache. “Thinks he’s going to challenge the Bomber next year…” “So let him challenge; he can lose one fight. He needs the payoff, needs it big,” said the chunkier one of the two, “Snort” Bianchi—with a snort.

is this a joke

This is one place I am not sure of Shirley’s intentions. Is it supposed to be bad? Is it supposed to be funny? Is he making fun of me or is he just dumb enough to think this is clever?

What I think this dialogue and these characters represent is Shirley’s attempt to complement BioShock's audio diaries. Again, we hit that divide between the ways stories are best told through different mediums. BioShock’s audio diaries are the literary equivalents of bullion cubes. That’s because you experience dialogue sparingly in a video game, and most content is wrapped up in gameplay, so you’ve got to get your whole idea across as quickly and densely as possible.

It’s for this reason that every BioShock character is an outsized caricature. In the same way that Fontaine is a symbol of Objectivism in its purest form (let's face it, the fountainhead of Man with a capital M), McDonagh is Andrew Ryan’s conscience, and Andrew Ryan is Man falling for the lies of the demiurge. Jasmine Jolene—whom we will see in Chapter 3—represents untenable fantasy.

Oh, and Shadow Eve.

Y’all wanna talk about Shadow Eve? I do. There's only like three of us reading this and I'm counting myself so I'm assuming the vote is unanimous.

Long story short, Shirley doesn’t understand the differences between video game narratives and literary ones, and this fact is probably going to hurt me until the end of this entire broken endeavor.

Shirley also feels like he needs to show Fontaine at work at all times. In his mind, Fontaine is nothing but cons 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Shirley only knows what people do; he doesn’t know why they do anything.

In any case, Fontaine shoos off the Great Value Mobsters, for he has spotted our G-man from earlier, a man named Voss. It appears that Voss is looking for informations.

[Voss] leaned across the bar so he could be heard over the noise. “Word on the street is, this here’s your joint now.”

Originally, I had been reading this quickly, only to run into this paragraph and get terribly confused. Like damn, word travels fast, it’s been 30 minutes and everybody already knows this is Fontaine’s bar?

I had to go back and re-read. The passage of time is suggested somewhere in the info-dump that tells you everything about Fontaine instead of growing him organically over a generous period. It’s done terribly but at least it happened.

Voss crooked a finger, leaned even farther across the bar. Gorland hesitated—then he leaned close. Voss spoke right in his ear. “You hear anything about some kind of big, secret project happening down at the docks? Maybe bankrolled by Andrew Ryan? North Atlantic project? Millions of bucks flowing out to sea…?” “Nah,” Gorland said…. “What kinda deal’s he up to?” “That’s something we don’t… something you don’t need to know.”

haaaaaa haaaaaaa haaaaaaaaaaaaaack

In any case, Fontaine has it in mind that if there are millions of dollars flowing out to sea, he wants in on it somehow.

He didn’t hear anything about Ryan for a couple of days, but one day he heard a drunk blond chippie muttering about “Mr. Fatcat Ryan… goddamn him…” as she frantically waved her empty glass at him. “Hey wherezmuh drinkie?” demanded the blonde.

oh…………. oh this is a hate crime

Have you ever heard of Born Yesterday (1950)? Go watch a clip and listen to the actress, Judy Holliday. Her voice is what I hear in my mind. Except in Born Yesterday the protag is a human being and not a one-dimensional cutout with tits. And Born Yesterday is perfectly representative of its time so the fact it’s outclassing a writer in 2011 is shameful. The only question I have left about this book is, “Who cannot dunk on John Shirley?”

Now I think I understand Shirley a little better. I’m going to give him the benefit of a doubt and assume that we are looking at this crying woman through Fontaine’s eyes, and that this is not reality, but his fucked-up perspective.

You know how I was talking about the relationship between third-person limited POV and bedrock reality? This is one of those breakdowns. In third-person limited, we can see inside of one person, but nobody else. They occupy a world limited by their bias, but that world operates outside of them according to its own logic, which our Subject may or may not be able to comprehend truthfully. There should be clear divisions between what the Subject knows and perceives versus what is happening outside of them. When outside characters speak, or outside events occur, the reader should be assured that they really occurred in the ways they are shared. Otherwise there’s nothing solid to latch onto.

But I’ve got to be honest: I don’t know if this is intentional or not. I have never questioned point-of-view this way in my life. How much have I taken for granted in my tiny span? How do you learn to do something like this so, so badly?

This is John Shirley. We taught him wrong, as a joke.

Of course he wears all black and a goofy hat. Then he sucked all the contrast out until he was clothed in void. Does he think he’s a warlock

Long story short, this POV shit feels like madness to me. Should prose cause seasickness? The way this book is fucked up is one of the most unique experiences I’ve ever had. Although I’m learning a great deal from it, I also hate this experience. And I hate John Shirley.

“I’ll have a Scotch if I can’t have my man back,” she sobbed, “that’s what I’ll have! Dead, dead, dead, and no one from that Ryan crew is saying why.”

Ms. Ogyny the Exposition Whore has managed to interest me despite my deep loathing. I spy a mystery!

Coincidentally, this is why Fontaine’s sections tend to be the most interesting: he’s actively trying to figure things out where other characters just kind of hover in time and space.

New Reasons for Me to Feel an Unearned Sense of Superiority

Some of Shirley’s idiosyncrasies start popping out here because I’ve had some time to suffer under his patterns, much like a player getting their ass handed to them under an Elden Ring boss. For example, he sticks dialogue inside of descriptive paragraphs, and he thinks “went on” is an acceptable dialogue tag. I thought that was a fucking error until it happened the second time.

(✿◠‿◠)ノ.❀。• *₊°。I still think it is a fucking error ❀。• *₊°。 ❀

In my opinion, dialogue can be stuck with a descriptive scene, but it should be limited to the speaker’s actions alone. The implication is that the speaker is performing an action while speaking. Shirley will just slap dialogue into a paragraph with multiple actors and let the reader sort it out.

The reason why this is a problem is that it becomes questionable who the speaker is until you find a subject-verb or infer from context clues. Also, the longer the descriptive sequence, the more you have to think about the time taken to say the sentence as the character is performing the action.

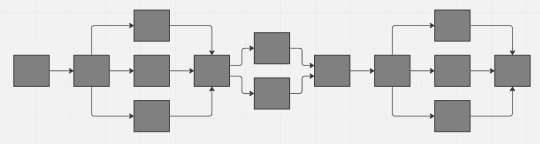

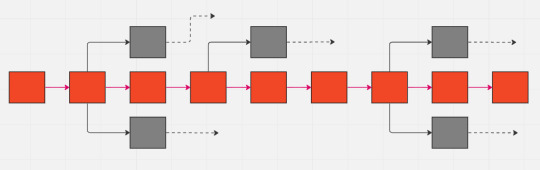

You do not want your work to feel like this:

This is where I noted another little idiosyncrasy: every time Shirley does any research, he regurgitates it almost wholly undigested. Here, in an example from the prologue, he discusses the outfit of a Red Army soldier:

“Father,” Andrei whispers, in Russian, turning to look at a tall lean man in a long green coat with red epaulets, a black hat, a rifle slung over his shoulder. “Is that man one of the Red Guard?”

“in Russian” no shit

“Oh, that’s perfectly reasonable,” you may protest.

Then how about this sequence in Chapter 2, where he talks about boxers:

The talk at the crowded bar tonight was full of how Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, back from the war with a pocketful of nothing and a big tax debt, was going to defend his world heavyweight title against Billy Conn. And how the retired Jack Johnson, first Negro to win the heavyweight champ title, had died two days before in a car accident. None of which was what Gorland needed to know.

(✿◠‿◠)ノ.❀。• *₊°。then why the fuck did you mention it ❀。• *₊°。 ❀

My chief complaint about the first set of descriptors is the list of prepositional phrases and weak adjectives and verbs. It’s a lot of talk with no power or aim. Additionally, Shirley just wrote about a dozen other people while mentioning their appearances so briefly that they might as well have been plywood standees, so a thoughtfully colorized soldier jumps out like a cat in a shitty horror film. That said, if you’re not a picky bastard, it may not bother you.

But the second one is outright incorrect. None of these historical people or subjects have anything to do with Fontaine’s current aims, nor with what he does next. It’s just there to prove that Shirley did research. If anything, it shows Shirley’s weakness: he doesn’t know how to smoothly blend research into his work.

This description is like stirring your cookie batter three times and calling it done, then spooning out a big lump of baking powder.

Shirley just put that shit in the oven.

“I just want my Irving back,” she said, her head sagging down over the drink. Lucky the song coming on the juke was a Dorsey and Sinatra crooner, soft enough he could make her out. “Jus’ wannim back.” He absentmindedly poured a couple more drinks for the sailors at her side, their white caps cocked rakishly as they argued over bar dice and tossed money at him. “What became of the unfortunate soul?” Gorland asked, pocketing the money and wiping the bar. “Lost at sea was he?” She gawped at him. “How’d you know that, you a mind reader?” Gorland winked. “A little fishy told me.”

gross

God, this paragraph is ugly and I hate it. Shirley splits the lady’s dialogue, part of which butts up against Fontaine and two sailors and causes a moment of cognitive dissonance. Shirley is ridiculously specific as to the song playing when “soft crooner” would have sufficed. The true note of interest—the data that Fontaine is sniffing out—skitters around the outsized imagery like a stupid cartoon creature.

Shirley does have a strength, and it’s in visuals. I can see and feel and smell this bar. Unfortunately, his visuals are static and progress little to nothing. Also, from what I can tell, it’s his only skill, unless causing headaches is desirable.

Also, before I leave this part, I want to clarify that there’s no problem with mentioning historical events, organizations, music, speech, people, etc, in your historical novel, and in fact you should, but if that description is at the expense of your plot, you have erred.

In any case, Fontaine asks this unfortunate caricature of womanhood what happened to her beloved. Shirley writes a long and embarrassing paragraph of dialogue that cannot end soon enough, and when it does end, it’s like this:

“Well, I went over to the place that hired him, Seaworthy Construction they was called—and they threw me out! Treated me like I was some kinda tramp! All I wanted was what was comin’ to me… I came out of South Jersey, and let me tell you, we get what we’re owed ’cause…” She went on in that vein for a while, losing the Ryan thread.

You lazy fucking bastard.

This is not the first time Shirley has ended a paragraph like this, either.

A Visual Depiction of the Dismount

Look, there are graceful ways to ease out of dialogue. Shirley doesn’t care what they are. Dialogue stands between him and a description of a “zoot-suiter [putting] a bebop number on the juke.” Do I care about that, sir? I do not. How about Andrew Ryan? How about Rapture? How about

Fontaine Shapeshift Moments Numbers 4, 5, & 6

One of Shirley’s responsibilities as writer is that he needs to illustrate the kind of person that Fontaine is. As far as I’m concerned, he’s done it several times over. It is abundantly clear that Fontaine is an asshole, and it’s clear what kind of asshole he is, even if he is kinda boring. Now that Fontaine has the Rapture thread, you would expect for him to follow that, because that’s what I’m reading this book for.

Obviously, that’s why Shirley takes Fontaine to a boxing ring! Because it is time to throw a fight! After all, we must follow up on that Great Value Mobster thread! We care so much about that! My heart throbs with anticipation! About Twitchy and Snorts!

See, Shirley did not illustrate one specific trait of Fontaine’s, and he thinks it’s important enough to digress to it: Fontaine’s ability to shapeshift, as it were.

“My name’s Lucio Fabrici,” Gorland said, tying Steele’s glove’s nice and tight. “Bianchi sent me.” … “Fabrici” had gone to great lengths for this disguise. The pinstripe suit, the toothpick stuck in the corner of his mouth, the spats, the toupee, the thin mustache—a high quality theatrical mustache carefully stuck on with spirit gum. But mostly it was his voice, just the right Little Italy intonation, and that carefully tuned facial expression that said, We’re pals, you and I, unless I have to kill you.

Wait. Was “spirit gum” called that in 1946? Oh, I don’t care.

It’s worth mentioning that I have noted two black characters so far—the boxer from the historical infodump and Steele’s trainer, who Fontaine paid to scram—and Shirley doesn’t let the trainer talk. And you know what? Given how he writes dialogue, that’s probably the safest option.

After Fontaine throws the thrown fight, he goes to his bookie operation.

[Fontaine] walked over to Morry, to have a gander at the take, and heard a couple of the dockworkers talking over their flask. “Sure, Ryan’s hiring big down there. It’s a hot ticket, pal, big paydays. But problem is—real QT stuff. Can’t talk about the job. And it’s dangerous too. Somewhere out in the North Atlantic, Iceland way…”

First of all, there’s the unnecessary description. Can’t we just assume that Fontaine walked somewhere? What does that add to the narrative? Use stronger imagery or take that shit out. That’s literally your only skill and now you’re fucking that up, too.

Second of all, split the dialogue off, why do you keep sticking it to random fucking descriptions.

Third of all, how does the entire fucking world not know what Andrew Ryan is doing? Half of what Fontaine has learned has been from overhearing random people. It’s like the whole universe is conspiring to help Fontaine out, and it’s getting a little weird, I’m gonna be honest. Every time I randomly overhear people it’s things like grocery lists and brain-dead political takes. When will I overhear where to find one million dollars

Then there’s how Fontaine reacts when he overhears this information. This sentence immediately follows the paragraph above:

[Fontaine] slipped outside by the side door and set himself to wait.

He literally says nothing to anyone. He just leaves. He’s just had an intense exposition-filled conversation with his employees and then he’s like whoops bye bitches fuck your lives

Look at how fucking pathetic this sentence is, too. “Set himself to wait”? I actually double-checked this after an edit because I was sure I’d inserted a typo. No, it’s just this bland.

This whole sequence was almost certainly written at a sprint. Words and phrases are weak as shit—no emotional power, no visual or spatial sense, no movement. There are no smooth transitions and, quite naturally, no tension. It’s just one domino falling after another. You wanna take a moment and think?

NO.

RUN BITCH.

RUN

Fontaine follows the deckhands until they reach their ship—the Olympian.

Gorland tilted his hat so the G-man wouldn’t see his face and strolled over, hands in his pockets, weaving a bit, making like he was drunk.

There’s some more embarrassing tryhard dialogue but you can read it yourself.

“Making like he was drunk.” jesus christ are you even trying

The only important part is the deckhand arguing with an officer.

“I just ain’t shipping out to that place again, and that’s all there is to it,” snarled the deckhand in the black peacoat. … “I don’t mind being on the ship—but in that hell down below, not me!” “There’s no use trying to say you’ll only take the job if you stay on the ship—it’s what Greavy says that goes! If he says you go down, you go down!” “Then you go down in my place—and you wrestle with the devil! It’s unholy, what he’s tryin’ to do down there!”

Wait. What? Why? Why is it unholy to build things under the ocean? Look, I was a religious nut for a huge portion of my life, and I can’t remember any taboos about checks notes building underwater?

As the deckhand takes off, having quit employment with Ryan Industries, Fontaine sees a piece of metal, picks it up, and runs after the deckhand.

“Hey!” the man yelped. Gorland held the deckhand firmly in place and pressed the end of the cold metal pipe to the back of his neck. “Freeze!” Gorland growled, altering his voice. He put steel and officiousness into it. … “You think I’m some crooked dock rat? I’m a federal agent! Now don’t even twitch!” [Fontaine said.]

Fontaine flashes a fake badge, then gets this deckhand to spill his guts. In two pages, he learns about Ryan building a city beneath the sea, complete with information about its technology and current state of construction.

End chapter.

Fontaine’s section of Chapter 2 runs from pages 39 through 54. In about two weeks, he has pretended to be six different people and learned everything he needs to know about Andrew Ryan.

You Can Always Try

I don’t know what Shirley was on at this point. In my mind, you devote one chapter to Fontaine at the tail-end of one really good con. Really put your effort into the con, show the ups and downs as the criminals attempt to outmaneuver the popo. Maybe show Fontaine fuck up some other criminal and then take his name. A shadow steps out of the smoke, adjusts his hat. “The name is Frank Fontaine.” Ohhhhh noooo I thought Frank Fontaine was that other guyyyy ooooooh shiiiiitttttt! And then never give out his background the rest of the story, and never show his internal world. Third-person objective: narrator stands outside of everyone. Keep Fontaine a huge question mark the entire story.

But Shirley was like, “Give Fontaine 3,000 cons in the same chapter, one after the other after the other, nonstop, don’t breathe, don’t stop, go go go go, and do it in such a way that Fontaine looks like the only human player in a world of NPCs.”

It just feels so unnecessary.

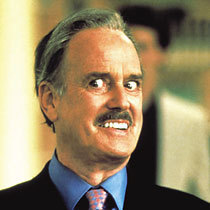

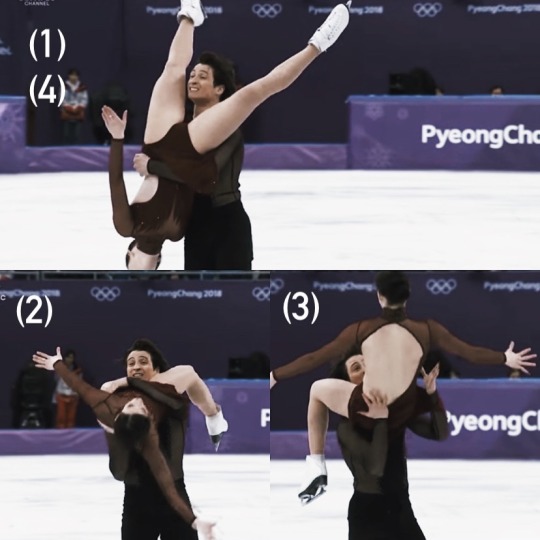

Here are images of Fontaine and Atlas.

That’s called “growing your hair out” and “cosmetic surgery” you fucking dumbass. It’s not that big of a deal. Now write something I give a shit about.

Question: how couldn’t the feds get all of this information in all the same ways, plus some? This is the FBI in 1946, the USA has just gone through WW2 like gangbusters, the Cold War is just warming up, and—most terrifyingly of all—J. Edgar Hoover is the FBI director. You think they give a single shit? Hell, I’m not sure they’d have to do much in the way of skullduggery at all. So far, the biggest problem with keeping Rapture secret has been employees talking.

Long story short, now Andrew Ryan and the US government look like chumps, and the narrative has the gall to imply Fontaine is skilled when he’s just unreasonably lucky. And if there’s one rule you should never break for a BioShock story it’s to make Andrew Ryan a fucking chump.

If You Must

Although having Fontaine front and center is not ideal, it’s also doable. So far, he’s the most interesting character in the book—probably because he’s solving the Rapture mystery. There are elements he doesn’t understand, which is a kind of tension, even if there are no repercussions for failure.

This tension is accidental. Just like every other character, Fontaine’s challenges and enemies are either neutered or indistinct. He hovers in a kind of eternal limbo where he is everything he has ever been. We can’t pretend it’ll get any better from here on out. However, let’s pretend that Shirley gives a fuck.

Now that Fontaine in a traditional character-driven narrative, we need to give him an arc. The Fontaine of Chapter 2 must not be the same Fontaine we see by the end of the story. We know Shirley will fail, but that’s the standard we’re going to judge him by. Remember: this isn’t BioShock-the-game. We’re writing literature now, so the aims and methods are different. If you’re going to use him as a major antagonist, he needs challenges to surmount, same as Andrew Ryan and Bill McDonagh and every other character ever.

So if you’re going to use Fontaine in this role, he has got to have an arc of some kind. He’s got to have something to overcome or learn or become because he’s in the kind of story that calls for that.

A competent writer would give you a reason to be interested in Fontaine. Shirley knows you’ve picked up this book because you’re a fan, so he presupposes you already are. So he just… doesn’t try.

jesus christ this lazy bastard. I hold him in utter contempt.

And I am just now at Chapter Fucking Three.

<- Part 5: Three Old Men Jerking Their Milk Sticks || Back to the Beginning || Part 7: Shadow Eve ->

#bioshock#bioshock rapture#frank fontaine#writing#reading#essays#rants#long post#vvatchword#vv reading#sorry for how awkward this gets but I'm tired and done now

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I haven't seen Disney's Wish myself (I'm waiting for it to assumedly go to Disney+, theaters are a lot of money to spend too often), so I can't speak on the film from my own point of view yet, but I have seen the reaction to it so far and I wanted to share my thoughts on why I think some of these reactions are happening, based on my own experience of watching and listening to the Disney fandom's critiques over the many years I've done so. These are just my observations based on my experiences and it's okay to disagree, just be cordial.

Opinions below the cut ↓

I feel like a part of why Wish is the way it allegedly is has to do with something that has been plaguing Disney for a while: trying to prove bad-faith criticisms wrong instead of knowing their strengths.

I'm sure they still happen, but especially in the early and mid-2010s Disney had a lot of half-baked criticisms directed at their stories and characters. Wish might be another one of many attempts to quell these critiques. For example, I remember a common piece of writing advice would be to make villains complex all the time, with villains who are evil for evil's sake being seen as less well done (this was towards media in general, but it applied to Disney too), so Disney began the surprise villain and/or the sympathetic villain trend in their films. Now people have seen that shtick so much they want traditional villains back (me too). It's now overdone and no longer shocking or subversive in their movies anymore. [And as a little add-on, I understand why people want King Magnifico's design to be more "traditionally villainous" but I'm actually happy he isn't, as it's really hard to design a villain like that without perpetuating some kind of bigoted stereotype that a lot of traditional villains have. Even Mother Gothel, one of the last, if not the last of the classic villains Disney has attempted, had a lot of antisemitism baked into not only her design but also her actions. Disney's done that a lot, which is likely accidental, but still bad. I'd much prefer him to look and act like some guy over an awful Jewish stereotype or something similar.] People also called princesses with the temperaments of, say, Aurora, Belle, or Cinderella "boring", or hell, "sexist" in their characterization, so the heroines were made more relatably quirky, as that type of humor towards/by girls and women were very popular in the 2010s. Asha is allegedly somehow both socially inept and socially competent, which arguably isn't a flaw at all, just contradictory. (My neuro-spicy brain wants to somewhat lean towards neurodivergence when I hear that, but I haven't seen the film, so what do I know?) Now people are souring to that too, understandably, as that humor's kind of dated and overdone with Disney's heroines. These traits aren't bad on girls automatically, especially if they make sense for the environment they grew up in like Anna or Rapunzel, but they've just been done to death with Disney. Ironically, now when I see people suggest alternative traits for Asha they propose a more "sophisticated", "mature", or "self-assured" type of personality, aka, what the "sexist" traditional heroines had a lot of the time.

The newer tropes Disney tried to do in place of their old ones don't have as much staying power as the old. Once they're done so much they get stale. If they're based on trends in media rather than being actually captivating in writing, they become timely. People can digest characters like Cinderella, who are interesting and aren't overly worried about upholding trends in their characterization, for centuries whether they realize it or not. But characters like what Asha is allegedly like are based on trendy, shallow politics that aren't as deep as they sound, maybe sometimes even circling right back into the bigotry it was trying to combat (like the girl-boss stuff), and become overdone and/or dated if they aren't done well or in a new way. I feel like because of the poorly made assessments that people used to make towards Disney, Disney is almost embarrassed by their past films when they really shouldn't be. This is why the recent remakes tend to over-correct the originals. In the original Beauty and the Beast, it was not a flaw that Adam was eleven when he was made to look like a beast in my opinion, it just made it more interesting, but some reviews saw it as a bad thing, so they changed the line in "Be Our Guest" that implied his age. It was seen as a flaw that the original Cinderella didn't have a clear reason to stay with her abusive family, even though that's how familial abuse works often and it's really rude to victims to ask "Why don't you just leave?" or something like that; so Disney gave Ella the explanation that she stays because it was her father's home in the 2015 remake, which only added more flaws when you remember that she does leave the house in the end anyway. What was the point in saying that? People wanted strong female characters, so Mulan in her remake is a flawless, emotionless girl-boss. It was seen as sexist when female characters wanted romantic love because "girls don't need a man, so romance is sexist", so Disney stopped telling love stories and focused more on issues of the self, which isn't bad, but now people want Disney to tell love stories again and are disappointed that Asha didn't have a romance with the mostly cut "Star-Boy" character in Wish (again, me too, I love Disney's love stories). All of these are overcorrections to things that were never flaws to begin with, just nit-picks from bad observations of their films. There are too many examples. It's like Disney is insecure.

If Disney understood that these things weren't bad in essence, Wish would be more liked by its critics; if Disney wasn't afraid to let their female characters have actual flaws, not see romantic love as something dated, not continue to listen to these types of shitty judgments, or just take more risks again because that's what shaped the company—taking risks against the odds, Wish would be better (I assume all of the former based on what I've heard, again I haven't seen Wish myself). The pseudo-feminism and CinemaSins type of critiquing from the 2010s has mostly died out. The culture's changed. The tropes people once condemned are now being begged to be brought back. What goes around comes back around. It showcases what was truly timeless and what was just a trend in media.

In my opinion, old bad-faith "fan" responses are partially to blame for these themes in recent films, but of course, Disney is ultimately at fault because they make their own choices. There could also be plenty of other reasons why Wish feels half-done to some, like the alleged poor treatment of employees behind the scenes.

By the way, if you were a Disney fan who had these types of opinions in the past, you shouldn't be hard on yourself about it, especially if you were just a kid listening to and trying to appeal to the adults that were around you or influenced you. The latter is the boat I was in once, and now I've grown up past that. Needlessly cynical film takes and pseudo-feminism were all the rage for a while and many have had that phase of being really into those mindsets. You're not bad if you've been in it at any time in the past as long as you are learning and growing.

I'm choosing to be optimistic about Disney. Somehow I still am. They have been in a creative rut for what seems like a while now. Disney-creative doesn't seem to be allowed to tell the stories they want to tell, instead being made to cater to the wrong people. The people who like to insult Disney more than they like watching their films. They should make movies for the fans of all ages who love them. But I believe Disney can bounce back from this. Disney has been through rough patches before, but these rough patches in the past have led to eras like the Disney Renaissance. I'm hoping the backlash from Wish will lead to Disney making changes once more. They've done that repeatedly in their complex 100 years of establishment. Gone are the times when the Disney remakes were panned by fans but still made tons of money that justified their continued production. And long gone are the days when fans were actually excited about the prospects of Disney recreating their movies (because yes people felt that way once upon a time). Now the remakes aren't making as much as Disney wants and sometimes even flopping. Gone are the days when their animated films were their critical lifeline, Wish proves that they are not immune to being received poorly. It's time for something new. Or old done new. Just something different. It would be one thing if this were just another bad movie, but this was their 100th-year celebration, you think they'd be more careful to not muck it up. But apparently, all it did was reflect all the flaws that have been in Disney's storytelling as of late. That's why the backlash is so great. It feels like the last straw. Once time goes on past the 100th-anniversary era, I think the hate for Wish will die down, but that wouldn't make it less potentially flawed. When I first caught wind of this film, way before we had a trailer even, I was very excited that it seemed like a return to form for Disney, but apparently, it might not be, and that's got a lot of people disappointed, especially since this movie was meant to be a celebration. I've loved Disney for as long as I can remember and I know a lot of people are the same way. People wouldn't be so disappointed in the state of the company if they didn't care deeply about Disney and believed that they could do better. I still think Disney could be great. I still believe in them. They just need to believe in themselves again.

If you made it this far, thank you so much for reading! ♥

#disney#wish#disney's wish#wish 2023#disney discourse#fandom discourse#discourse#disney essay#disney essays#essay#essays

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I’ve tried to show here, realism once was among the staunchest allies to the violence perpetrated globally by European colonial power. It’s hardly surprising then to see realism find its strongest legacy in American literature today. That said, my point here isn’t that realism doesn’t produce compelling storytelling. It couldn’t have served power for this long if it didn’t. My point is about the countless erasures enacted by the hegemonic forms of storytelling and its many gatekeepers. My point is about the soft violence of narrative, that in its vast potential to silence dissenting voices, upholds and fortifies imperial violence. This violence is nowhere as immediate and forceful as the mass slaughter of children, starving or bombing entire families off the face of Earth. Yet as a brown woman writer, I haven’t been able to look away from the subtler form of narrative violence that lasts for generations if not centuries, and at some point it stops needing the colonizer to do the work for empires. If narrative is inextricable from power, my point is about the ways in which narrative erases many of us and a few of the many ways in which we reclaim it.

In 2022 my debut novel, Border Less, was published in North America (7.13 Books) and South Asia (HarperCollins India), two spaces of diasporic life and aesthetic legacies that my fiction centers. When the novel was first released in the United States, I was nervous about its reception even if I was proud of the book I’d written. I was nervous mostly because when I transitioned from a world of literary criticism to a world of fiction writing, I learned how much narrative forms harden and tangle with the tastes of the market, especially in the United States, a key player within global anglophone literature. In an industry documented to be predominantly white at the highest levels of literary gatekeeping, I feared that my indie debut as a brown woman writer would mark the end of a dream that had barely begun to manifest.

To my relief, Border Less was received generously by its readers, who appreciated in general the novel’s play with form. In the United States, though, a couple of questions came up often in my conversations with literary gatekeepers, informed readers whose opinions hold power to shape the larger response to a book. Some asked me—explicitly or implicitly—to explain why my book should be called a novel if it employs fragmentation, discontinuity, and perspectives of multiple characters. Others—spoiler alert—asked me to explain why I chose to end my novel with a minor character’s meta-narrative perspective over the main character’s narrative one. What I heard in these recurrent questions was the assumption that a “real” novel is one that maintains continuity of narration and perspective, one that focuses on and pursues until the closing note the protagonist’s inner journey. What I heard here was the assumption that a real novel is the realist novel.

Before I continue I’d like to clarify my intent in sharing this observation. In emphasizing a partial and North American reaction to Border Less, my intention isn’t to condescend to critics or readers who didn’t get it. Neither am I here to dismiss the merits of realism as a narrative form. As an author I’m grateful to every reader who engaged with my debut in all ways they did. As a critic and educator I spent over a decade reading and teaching the realist novel, mainly those authored by Black and brown writers from across the world; it’s a narrative form I still love. Yet as I continued to explain my debut book as a novel to a North American literary community, I couldn’t help wondering: How did the novel, known to be the most versatile of narrative forms, congeal here into such a bordered form? In other words, how did the contemporary American novel become synonymous for so many with the modern realist novel? Who do these literary borders serve, and what’s at stake if we don’t ask these questions?

In his groundbreaking book Culture and Imperialism (Knopf, 1993), Palestinian American literary critic Edward Said chronicled the massive growth of the realist novel in recent Western history, especially in the three homes of unparalleled imperial power: England and France in the nineteenth century and the United States in the twentieth. Similar to social media’s capacity for the rapid, mass circulation of ideas today, the realist novel served then as a key tool of Western imperial propaganda, especially through the form’s emphasis on narrative principles that weren’t central to fiction from many other parts of the world, or even to precolonial Europe. Whether we consider the first English novel, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and its widely popular subset of imitations called Robinsonades, all featuring a protagonist who leaves the motherland to establish a colony elsewhere, or we consider Defoe’s successors—Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Jane Austen, and others—the realist novel encoded a web of references and attitudes toward non-Western peoples that bolstered Western imperial expansion.

Through close readings of excerpts from novels by Defoe, Conrad, Austen, Dickens, and other colonial writers, Said shows how realism focused on character development in stories of survival and self-determination and served a predominantly bourgeois readership. In these books, “The novelistic hero and heroine exhibit the restlessness and energy characteristic of the enterprising bourgeoisie, and they are permitted adventures in which their experiences reveal to them the limits of what they can aspire to, where they can go, what they become.” To borrow from today’s workshop parlance on “craft”—and to echo John Gardner’s famous description of good fiction—the realist novel worked hard at building “a vivid and continuous dream in the reader’s mind” through a prioritization of craft elements like character development, causality with its notion of linear time, continuity of narration maintained through verisimilitude, commentary, setting, and description, especially of the imperial home-country, articulated through the secondary yet key presence of distant colonies.

Said, of course, isn’t the only writer to show us how much of a recent geo-historic construct realism and its narrative principles are, even if it was in his work that I first understood how much storytelling serves power. About two decades later, acclaimed Indian writer Amitav Ghosh published a nonfiction book on the relationship between Western humanistic thought and global environmental concerns, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (University of Chicago Press, 2016). In this book, Ghosh talks about the rise of the Anthropocene in Western arts, sciences, and contemporary culture in which the human being—rather than nonhumans, the landscape, or some other element—became a literary narrative’s main agent of force, the one in charge of shaping plot. Here, too, the centrality of character development or the pursuit of “individual moral adventure” that is most associated with “serious fiction” in the West and the Anthropocene’s upholding of human agency, gained ground with the marriage of modernity, colonialism, capitalism, and monotheistic religions, especially Protestantism in which “Man began to dream of achieving his own self-deification by radically isolating himself before an arbitrary God.” Furthermore, The Great Derangement shows us how the realist novel upheld continuity of narration through the use of detail and description or “narrative fillers” (to echo literary theorist Franco Moretti) to establish verisimilitude or the principle of probability, once again with the goal of not disrupting the implied bourgeois reader’s pleasure.

In 2017, Chinese American writer Gish Jen’s book The Girl at the Baggage Claim: Explaining the East-West Culture Gap (Knopf) echoed Ghosh’s claim of the Anthropocene dominating the Western literary arts where the conception of self, in general, remains individualistic. Similar to Ghosh, Jen attributes the recent historic emphasis on individualism over the collective in Western storytelling to a string of historic developments that include “monotheism, Judeo-Christianity, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Reformation, and Romanticism, not to say the rise of market economy.”

Said’s, Ghosh’s, and Jen’s works name well—in their own ways—the historic context that allowed realism to dethrone other forms of storytelling, first in the West and increasingly around the world. Yet these works don’t link this history enough to a key space through which realism continues to maintain its legitimizing hold on anglophone literature in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What I’m talking about here is the role of the mainstream MFA program in the United States, the nation of the largest military and imperial power of our time. As I have written elsewhere, the MFA is an undeniable, hegemonic force on contemporary American letters, an empire of its own that often universalizes a provincial pedagogy of “good” storytelling. So much necessary ink has already been spilled by my peers here. Several contemporary writers, including Junot Díaz, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Claudia Rankine, Felicia Rose Chavez, Matthew Salesses, Beth Nguyen, David Mura, and Joy Castro, as well as my own essays elsewhere, have shown how much of what we understand to be the craft of good storytelling in the United States disseminates the historic context and cultural capital of a highly narrow demographic: upper- to middle-class, able-bodied, cis white men. Eric Bennett’s work here is particularly incisive in understanding the nexus between the production of American literature and American imperialism. For instance, Bennett published two essays in recent years in the Chronicle of Higher Education whose titles and bylines say it all: “How Iowa Flattened Literature: With CIA help, writers were enlisted to battle both Communism and eggheaded abstraction. The damage to writing lingers” (2014) and “How America Taught the World to Write Small: It exported a literature of individualism and domesticity—not one of solidarity and big ideas” (2020). These essays situate the origins of creative writing programs in the U.S. in the mid-twentieth-century American fear of Communism and the MFA’s economic foundations in the CIA, the State Department, and patronage by conservative American businessmen. “The discipline of creative writing was effectively born in the 1950s. Imperial prosperity gave rise to it, postwar anxieties shaped it,” Bennett affirms, referring to the explosion of MFA programs across the U.S. whose pioneering figures like Paul Engle at Iowa and Wallace Stegner at Stanford “shared a common vision for American culture with the internationalists of the Truman and Eisenhower administrations and influential philanthropic foundations.” Bennett writes about how the mainstream MFA program fostered a highly bordered kind of writing, one that upheld “the putative civic sufficiency of unapologetic selfhood” as key not only to good, literary storytelling, but also to the American identity defined in opposition to a Communist one.

In 2014, Brian Merchant, technology columnist for the Los Angeles Times, echoed Bennett on the MFA and the CIA in a piece for Vice in which he equated postwar American literature produced by “the MFA factory” to a “content farm” that perpetuated a specific ideology and aesthetic of writing. This specific aesthetic, often taught as a universal one, valorized the concrete over the abstract; showing over telling; the role of emotions and imagination over critical thinking; domesticity and nationalism over transnationalism; the right grammar, syntax, and sentence craft over one’s relationship to a lived historic moment and the world. For Bennett, Merchant, and many of my American peers of color, this aesthetic both proceeds and follows the birth of the MFA in an anticommunist paranoia; it finds its most enduring legacy in names like F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Paul Engle, Frank Conroy, Wallace Stegner, Ernest Hemingway, John Cheever, Raymond Carver, and periodicals like the O. Henry anthologies, the Paris Review, the New Yorker, the Best American Short Stories, and more.

As I write this essay, almost a century since the birth of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, whose graduates are most credited with the rise of the American MFA, the latter has produced several faculty members of color who, as I’ve noted earlier, practice and write about an alternative pedagogy of literary storytelling. Moreover, in spotlighting the traditional MFA program in the U.S., its dominant ideology and pedagogy of writing, my irritation isn’t with a practice of craft that pushes our students to choose concrete details over abstractions or engage with feelings over critical thinking or our visual faculties over aural ones while working with the page. The aforementioned approaches can produce effective explorations with writing for the novice writer, as well as finely crafted stories by any writer who takes them seriously. Neither is this essay about my exasperation with realism or its core narrative assumptions; I continue to love the form, even if I do read the realist novel through a different critical lens now. As a writer and an educator, I often rail against the pedestalization of narrative assumptions from a colonial era that continue to be upheld as timeless, universal truths within a field of U.S. “creative” writing that prides itself on celebrating innovation and, increasingly these days, diversity and decolonization. What baffles me is the centrality of realism as the—not a—respectable form of literary storytelling in the twenty-first-century U.S., whether it is through the mainstream writing workshop and its decontextualized pedagogy of craft, fiction, or reviews published by prestigious literary magazines, major deals for “literary” fiction by the Big Five, the adjudication of prestigious awards, and more.

Moreover, it raises the questions, however rhetorical: Can “minority” writers break the aesthetic and ideological walls drawn by imperial institutions in the name of good storytelling and still be celebrated for their work? In an industry where diversity has become a profitable buzzword and phenomenon, a marginalized point of view in fiction may be very welcome, even rewarded with the highest honors, but what of marginalized points of view that tell their story through marginalized forms of storytelling? In other words, for the minority writer, is travel toward aesthetic innovation doomed to follow a fiercely bordered road? A path predetermined by the hegemonic notions of form?

A book that resonated deeply with me while I grappled with questions of narrative form and gatekeeping as an Asian American writer is Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (One World, 2020), even if it centers a highly bordered notion of Asian America. I read Minor Feelings in 2020 while I was finishing drafting my novel, Border Less, which was due for publication at the time. In her collection of essays that digress unapologetically, Hong reminds her readers how much the white gatekeepers of American literary fiction love coming-of-age stories by nonwhite writers, delivered on the page through “the MFA orthodoxy of ‘show don’t tell.’” The latter is a narrative move in which readers are invited to view a character’s journey without authorial intervention, a narrative move perfected by realism, I add. In returning often to her journey with artistic expression that would feel true to herself, Hong confesses that she abandoned her novel-in-progress about the 1992 L.A. riots and the complexity of American race relations, mostly because she couldn’t write a book that would suit the U.S. fiction market’s narrative taste. This market’s “ethnic literary project,” Hong reminds us, craves and rewards narratives of becoming by BIPOC, those that highlight stories of “survival and self-determination,” recalling in many ways Said’s “enterprising bourgeois” protagonist in colonial, realist fiction. Furthermore, the U.S. market’s love of realist fiction—with its narrative preferences for continuity, linearity, third-person narration, and show-don’t-tell—serves its implied white readers as it allows them to consume stories of pain by people of color without having to confront a white history of colonial violence and its global aftermath.

As much as I loved reading and teaching Hong’s journey as an Asian American writer, I haven’t stopped wondering: How many “minority” writers routinely abandon their novels because the forms available to or legitimized for them do not suit the stories they are trying to tell? In my community of aspiring and published authors, I know too many. And I ask myself, often in vain: Whose voice speaks loudest in their heads when aspiring novelists convince themselves that their manuscript is best laid to rest?

In 2004 in Mumbai, I started working every night on my debut novel, even if I didn’t know then that my jottings would eventually become a book. I had returned to my hometown after taking a year of leave from my graduate program in the United States, where I was training to become a literary critic, the closest I thought people like me could get to becoming a fiction writer. Even if I had always loved the world of art, language, and storytelling and had a strong legacy of these within my community, even if I had won a doctoral fellowship from an elite literature program, I wondered while scribbling in my notebook if the world of art, language, and storytelling was a path for me. From the time I mastered reciting Wordsworth’s “[I wandered lonely as a Cloud]” or excerpts from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in my middle school in Mumbai to the years I wrote the earliest drafts of Border Less, the stories I grew up imbibing from my community felt a galaxy away from the stories I was taught to appreciate as Literature. When I say Literature with an uppercase L, I refer to a body of writing that is legitimized by the Western establishment or imperial powers as the “literary” or “fine” arts. At the end of my sabbatical in Mumbai, I returned to the United States, finished my education, and started teaching, the only way I knew to financially sustain myself while nurturing writerly dreams. On the long, winding road to becoming an author, things about which I often write elsewhere, I was fortunate to encounter the right mentors, “minority” women across the racial spectrum who taught me an alternative relationship to literature and storytelling. After a colonial education in English that pushed me away from Literature in my earlier years of schooling, I discovered later in life storytelling by Black and brown writers from across the world who resisted erasure and reclaimed power through colonial languages in Literature: Arundhati Roy, Aimé Césaire, Édouard Glissant, Bharati Mukherjee, Ananda Devi, Toni Morrison, Maryse Condé, Gloria Anzaldúa, and many more.