#g. w. hegel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

«Toda filosofía, precisamente por ser la exposición de una fase especial de evolución, forma parte de su tiempo y se halla prisionera de las limitaciones propias de éste. El individuo es hijo de su pueblo, de su mundo, y se limita a manifestar en su forma la sustancia contenida en él: por mucho que el individuo quiera estirarse, jamás podrá salirse verdaderamente de su tiempo, como no puede salirse de su piel; se halla encuadrado necesariamente dentro del espíritu universal, que es su sustancia y su propia esencia. ¿Cómo podría salirse de ella? La filosofía capta, con el pensamiento, este mismo espíritu universal; la filosofía es, para él, el pensamiento de sí mismo y, por tanto, su contenido sustancial determinado. Toda filosofía es la filosofía de su tiempo, un eslabón en la gran cadena de la evolución espiritual; de donde se desprende que sólo puede dar satisfacción a los intereses propios de su tiempo.»

G. W. Hegel: Lecciones sobre la historia de la filosofía, I. FCE, pág. 48. México, 1955.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

#hegel#georg w. f. hegel#g. w. hegel#idealismo#idealismo alemán#filosofía#verdadevolución#individuo#historia#historia de la filosofía#lecciones sobre la historia de la filosofía#lecciones sobre la filosofía de la historia#pueblo#mundo#filosofía contemporánea#época#espíritu universal#teo gómez otero

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hegel#hegelian dialectic#g. w. f. hegel#georg wilhelm friedrich hegel#hegelianism#marxismo#socialism#leftism#marxism leninism#philosophy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desire

Every human action is a product of some sort of Desire, for we first need to "want" to then actualize that into an action. We could align the root of every Desire to a yearning for reconciliation with that which we stem from, the Womb. The womb is the only place in the entirety of our existence into which Desire is not present, because each and every thing we could want is (god hopes) given to us without the need of our yearning for them beforehand. In the womb the whole and the baby are into perfect harmony, but in this world we, as humans, are never in harmony with the whole We will call that whole the Absolute. Could perhaps every Human Desire stem from a yearning for harmony with the Absolute? If yes then it would mean life is but the inability to properly encounter the truth of the whole, and by proxy to be in a constant influx of Desires because we fail to find harmony with the Absolute. To Desire something that is never attainable can only mean existence is a constant of lying to yourself about having found harmony with the Absolute or suffering from the lack of such harmony. I do not like this answer, but it seems to be the logical result of my recent studies on Hegel, which could have been clouded by my also recent readings of Dostoyevsky but i do not wish to think about that at the moment. If the answer to the question if "Does every Desire stem from a yearning for harmony with the Absolute?" is no, then what could we as rational creatures desire besides wanting to unite with the whole? It seems both answers lead to the exact same result in regards to what is the end result of man searching for a higher state of consciousness The answer is Madness For man inevitably will end up mad because he thinks he has united with the Absolute or is mad for not wanting to do it at all. Either way, Fuck it we ball

#fyp#words words words#words#spilled words#my words#words of wisdom#lit#literature#philosophy#hegel#g. w. f. hegel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Hegel on the Journey of Spirit to Self-Understanding

Tuesday 27 August 2024 is the 254th anniversary of the birth of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831), who was born in Stuttgart on this date in 1770.

It is unlikely that anyone would call Hegel’s philosophy of history an Enlightenment philosophy of history, but there is a sense in which Hegel is the culmination of an especially fertile period in the philosophy of history that preceded him. Hegel transcended these Enlightenment philosophies of history in a supremely abstract way of understanding history and the developments it unfolds.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Text post: https://geopolicraticus.substack.com/p/hegel-on-the-journey-of-spirit-to

Video: https://youtu.be/kPIcS2x51tE

Podcast: https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/hEhcN4j0pMb

#philosophy of history#youtube#G. W. F. Hegel#Hegel#Walter Kaufmann#William Barrett#Bertrand Russell#Sidney Hook#Thomas Carlyle#Napoleon#Dasein#spirit#hero#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kisah Kalut Pendidikan

Pendidikan adalah cara untuk membuat manusia yang seutuhnya manusia, namun seperti apakah manusia yang seutuhnya manusia? Aristoteles (384 SM - 322 SM) berkata: manusia yang bahagia. Cicero (106 SM - 43 SM) berkata: manusia sempurna. Manusia yang sempurna adalah meninggalkan orientasi kebuasan dan orientasi kebanggaan menuju orientasi penalaran rasional.

Era Pencerahan (akhir abad ke-17 hingga awal abad ke-19) menolak Aristoteles tentang pendidikan. Bukan manusia bahagia yang menjadi tujuan pendidikan, tetapi manusia berkebudayaan. Bagi Era Pencerahan, manusia yang seutuhnya manusia adalah manusia yang memaksimalkan relasinya dengan alam. Terkadang relasi itu tidak membahagiakan, misalnya saat alam berubah menjadi bencana, tetapi pasti melahirkan kebudayaan, yaitu seni, sains, dan filsafat.

Gottfried von Harder (1744-1803) melihat manusia yang seutuhnya manusia adalah mereka yang bergantung kepada kolektivitas tetapi kolektivitas terbatas pada kekhasan budaya yang melingkupinya. Herder mempersempit relasi manusia dengan alam dengan relasi manusia dengan manusia, namun sama-sama menekankan pengaruh eksternal terhadap pembentukan manusia yang seutuhnya manusia yang dalam hal ini adalah kekhasan budaya masing-masing manusia.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) memperluas relasi manusia versi Harder dan menyebutnya sebagai relasi manusia (roh subjektif) dengan segala hal di luar manusia yang disebutnya roh objektif. Relasi tersebut dibangun dalam bingkai rasionalitas yang berlangsung sepanjang hidup manusia. Setiap generasi belajar dari generasi sebelumnya sehingga suatu saat manusia mencapai kesadaran tertinggi, yaitu menyatu dengan kesadaran roh objektif tersebut yang sesungguhnya adalah ekspresi Diri Sang Roh (Rasional) Ilahi itu sendiri.

Puncak dari Era Pencerahan adalah positivisme. Positivisme (abad ke-19) mengembalikan pemikiran Arisoteles tentang pendidikan yang melahirkan manusia bahagia. Modernitas melahirkan ilmu pengetahuan dan produk-produk hukum yang digadang-gadang menjadikan manusia bahagia karena minimnya penderitaan yang diselesaikan oleh ilmu pengetahuan dan hukum. Belakangan, kebahagiaan menjadi kesenangan, lalu menjadi komoditas yang diperjualbelikan. Kapitalisme lahir dari sini. Seni dan filsafat tidak ada harganya karena "jarum pentul sama harganya dengan puisi."

Positivisme melahirkan hal-hal yang maha dipuja yang dinamai modernitas, kemajuan, serta peradaban. Dampaknya ternyata sangat buruk karena melahirkan rasialisme dan diskriminasi karena jika ada yang modern, maju, dan beradab, maka ada yang primitif, terkebelakang, dan barbar. Lalu atas nama menjadi manusia yang seutuhnya manusia, orang harus dijajah, ditindas demi untuk diberadabkan, dimajukan, dan dimodernkan. Di era seperti inilah lahir sekolah sebagai lembaga satu-satunya yang mampu melahirkan manusia yang seutuhnya manusia.

Bukan hanya sekolah yang dilahirkan oleh positivisme, tetapi juga negara dan hukum. Problemnya, yang lahir kemudian adalah mekanisasi manusia. Manusia yang seutuhnya manusia sama dengan manusia mekanik yang memiliki kehidupan tetapi tidak memiliki jiwa. Hidupnya seperti gerak jam yang teratur kapan harus tidur, bangun, bekerja, hingga tidur lagi. Mekanisasi melahirkan pabrikasi yang produknya adalah manusia. Ya, manusia adalah produk, tidak lebih.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) hadir sebagai kritik terhadap positivisme dan Era Pencerahan. Marx senada dengan Hegel dalam hal adanya semacam roh objektif yang bersifat absolut yang menjadi muara dari segala upaya manusia menjadi manusia yang seutuhnya manusia, namun Marx memahami bahwa relasi antara roh objektif dengan manusia dibingkai oleh materialisme dan aktivitas material manusia. Faktor material inilah memengaruhi kesadaran manusia dalam kehidupannya. Bahkan manusia tidak memiliki kesadaran karena apa yang dimaksud oleh manusia dengan kesadaran sesungguhnya adalah faktor-faktor material sebagai pengandali manusia.

Kekuasaan atas faktor-faktor material melahirkan stratifikasi sosial berdasarkan gender, ras, umur, keterampilan, dsb. Di setiap strtifikasi sosial itu, hadir penguasa-penguasa material yang akan terus menjaga kekuasaannya dengan berbagai cara dari gangguan mereka yang cemburu dan hendak merebut. Karena itu, penguasa material membutuhkan ideologi dan keyakinan (agama) untuk memanipulasi kesadaran masyarakat agar tetap terbuai di dalam ketidakberdayaannya dan menganggapnya sebagai kenyataan alamiah dan wajar. Dalam ketidakberdayaan dan juga ketidaksadarannya, masyarakat akan terus-menerus menggantungkan diri pada kekuasaan/penguasa material. Intinya adalah ada relasi timbal balik antara kondisi material dengan sistem-sistem pemikiran dominan. Bahkan bagi Marx, “pendidikan” sesungguhnya adalah ideologi untuk memanipulasi.

Salah satu permisalan untuk kosa kata kosa kata seperti: pendidikan, masyarakat terdidik, universitas, dan yang berkaitan dengan itu. Semuanya sesungguhnya adalah ideologi yang memainkan gugusan kosa kata yang dibentuk agar terkesan luhur, tapi sesungguhnya tujuannya adalah kekuasaan kaum tertentu atas kaum yang lain demi kepentingan kekuasaan material. Katakanlah kaum terdidik itu bernama dosen, rektor, peneliti, dekan, pengamat, dsb. Bukankah yang mengikat mereka semua adalah kepentingan kekuasaan material dengan jargon-jargon kosa kata kaum terdidik, akademisi, cendekiawan, dsb yang kesannya sungguh luhur? Semua tidak lebih daripada “permainan bahasa”, language games, sebagaimana istilah Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951).

Manusia mekanik sebagai hasil pendidikan adalah manusia yang hidup bukan untuk saat ini, tetapi untuk masa depan karena kehidupannya senantiasa dihantui oleh masa depan yang tidak pasti. Masa depan itu bukan ditentukan sendiri oleh manusia itu sendiri, tetapi ditentukan oleh kolektivitas. Sepertinya, manusia jenis itu dinamai manusia rata-rata dan manusia kawanan, menurut istilah Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Manusia bukan kawanan, tetapi adalah individu-individu dengan kekhasannya masing-masing. Dia hanya akan menjadi manusia jika menjadi dirinya sendiri, bukan menjadi orang lain. Persoalannya, Nietzsche seperti sedang menyulut pemberontakan dari individu kepada masyarakatnya.[]

#pendidikan#friedrich nietzsche#Wittgenstein#karl marx#g. w. f. hegel#aristoteles#ideologi#cicero#positivisme#Gottfried von Harder

0 notes

Text

İlk olarak Sanatın bilimsel olarak irdeleme açısından değeri söz konusu olduğunda durum hiç kuşkusuz Sanatın eğlenceye ve oyalanmaya hizmet eden, çevremizi süsle yen, yaşamın dışsal koşullarına hoşluk veren ve süsleme yoluyla başka nesneleri öne çıkaran yitici bir oyun olarak kullanılabileceği biçimindedir. Bu yolda Sanat gerçekte bağımsız olmayan, özgür olmayan, ama hizmet eden Sa nattır. Ama irdelemeyi istediğimiz şey amacında olduğu gibi aracında da âzg-ürolan Sanattır. Sanatın genel olarak başka ereklere de hizmet edebilmesi ve sonra salt bir oyalanma olabilmesi olgusu onun benzer olarak düşünce ile de ortak olduğu bir yanıdır. Çünkü bir yandan bilim hiç kuşkusuz sonlu erekler için hizmet eden bir düşünce olarak ve olumsal araç olarak kullanılabilir ve o zaman belirlenimini kendisinden değil ama başka nesnelerden ve ilişkilerden kazanır; ama öte yandan kendini bu hiz metten ayırarak gerçekliğin bağımsızlığına yükseltebilir ve onda bağımsız olarak yalnızca kendi erekleri ile uyum içinde olabilir.

#hegel#georg wilhelm friedrich hegel#g. w. f. hegel#hegelian dialectic#aesthetic#introduction#Lectures on Aesthetics#aesthetics

0 notes

Text

True, as we're witnessing now.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Generating plasm and stacking matchboxes: how to build a better future through collective consciousness.

Alternatively - Steban and Ulixes were building Tatlin's Tower so I have to talk about the symbolism or I will explode!!

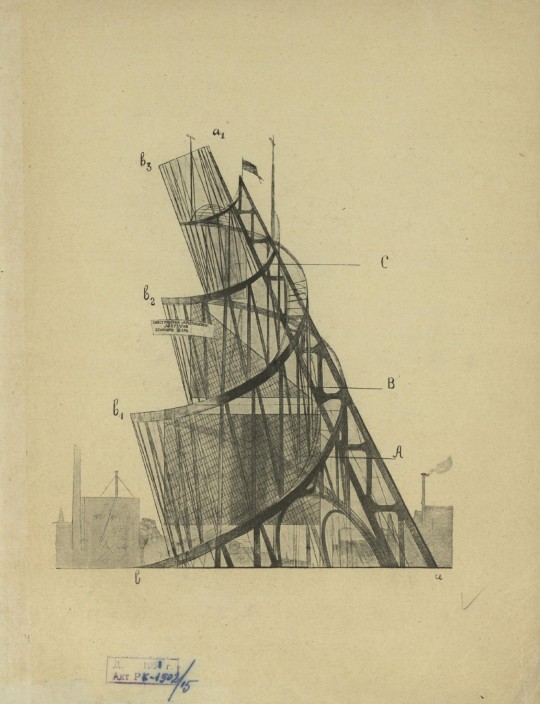

While completing the communist vision quest you get an opportunity to build a model of "The Tower of History", depicted on the last page of "A Brief Look at Infra-Materialism": a leaning tower wrapped in a dramatic helix. The scale model you make is a mirror image of Tatlin's Tower - a design for a grand monumental building to the Third International: the government organization advocating for world communism.

The main idea of the monument was to produce a new type of structure, uniting a purely creative form with a utilitarian form. Meaning it would function as an office building while also serving as a symbol of cultural significance. And let me tell you, this bad boy can fit so much symbolism in it.

Tatlin was commissioned to develop a design in 1919, after the 1917 February Revolution - a parallel to Disco Elysium's Insulinde we're witnessing post-Antecentennial Revolution.

Tatlin's work was inspired by high revolutionary goals, which are evident in the visual direction of the tower as well, expressing the ideological strive for achieving something that has never been done before, overcoming the odds. The structure "oscillates like a steel snake, constrained and organized by the one general movement of all the parts, to raise itself above the earth. The form wants to overcome the material and the force of gravity..."

The tower has meaning packed even in the materials. For example, the glass structures (marked A, B, C on the architectural rendering) were meant to serve legislative, executive and informative initiatives while rotating around their axes at different speeds. The material signified the purity of initiatives, their liberation from material constraints and their ideal qualities.

But here's the best part. The spirals.

"The spiral is the movement of liberated humanity. The spiral is the ideal expression of liberation: with its base set in the earth, it flees from the ground and becomes a symbol of the suspension of all (...) earthy interests." They are "the most elastic and rapid lines which the world knows" that represent movement and aspiration, continuing the themes of progress and freedom, but they also refer to something else.

In the process of building the matchbox model Rhetoric points out: "It's almost exactly as Nilsen's sketch imagined, a physical manifestation of the dialectical spiral of history."

The shape of the tower is a representation of dialectical development of history, first visualized as a spiral by G. W. F. Hegel. He pictured transformational change as "both linear and circular in order to be short-term responsive, i.e. possibly negating itself, and long-term strategic, i.e. a process of development."

Hegel's dialectics would later be reinterpreted through the prism of materialism by Marx and Engels to create dialectical materialism - the basis for historical materialism.

"Still, this idea, as formulated by Marx and Engels on the basis of Hegels’ philosophy, is far more comprehensive and far richer in content than the current idea of evolution is. A development that repeats, as it were, stages that have already been passed, but repeats them in a different way, on a higher basis, (...) a development, so to speak, that proceeds in spirals, not in a straight line; a development by leaps, catastrophes, and revolutions; (...) the interdependence and the closest and indissoluble connection between all aspects of any phenomenon (history constantly revealing ever new aspects), a connection that provides a uniform, and universal process of motion, one that follows definite laws - these are some of the features of dialectics as a doctrine of development that is richer than the conventional one."

The tower embodies progress in materialist understanding of history while also indicating the connection to ideological plasm, a manifestation of "the proletariat's embrace of historical materialism", necessary to create a better future.

According to Nilsen, the proletariat of a revolutionary state can generate enough plasm to create extra-physical architecture that "disregards the laws of 'bourgeois physics' and instead relies on the revolutionary faith of the people for structural integrity."

This function of plasm implies that The Tower of History can be created only under revolutionary circumstances - without a sufficient amount of plasm even the matchbox model didn't stay up. The exact same sentiment is expressed about Tatlin's Tower: "We maintain that only the full power of the multimillion strong proletarian consciousness could bring into the world the idea of this monument and its forms. The monument must be realized by the muscles of this power, because we have an ideal, living and classical expression the pure and creative form of the international union of the workers of the whole world."

Nilsen called it "the highest expression of Communist principles, a society whose literal foundation is the faith of its people."

Tatlin's Tower was a symbol of faith in the revolutionary future, the global triumph of Marxist socialism. A monument "made of iron, glass and revolution."

It was never built in real life, and neither was The Tower of History in the world of Elysium.

But you can try to see if there's enough plasm between the three of you. And the matchbox tower stays up for a long moment, quivering with an improbable energy. You believe it can say up - and it does.

So you have to believe; whether it's for collective action or generating ideological plasm. Then, together, maybe you'll be able to build as much as 0.0002% of communism.

#i tricked myself into reading leftist theory for disco elysium#never thought i would be reading Lenin to write about videogame worldbuilding#tower related quotes are from ''The monument to the Third International'' by Nikolai Punin#infra-materialism#disco elysium#de#de meta#disco elysium analysis#disco elysium spoilers#disco elysium meta

677 notes

·

View notes

Text

Each of the parts of philosophy is a philosophical whole, a circle rounded and complete in itself. In each of these parts, however, the philosophical Idea is found in a particular specificality or medium. The single circle, because it is a real totality, bursts through the limits imposed by its special medium, and gives rise to a wider circle. The whole of philosophy in this way resembles a circle of circles. The Idea appears in each single circle, but, at the same time, the whole Idea is constituted by the system of these peculiar phases, and each is a necessary member of the organisation.

G. W. F. Hegel, Hegel's Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830) (Hegel's Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences), translated by William Wallace

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jägermeister

Chapter Nine: Monsters of Our Own

Since their shared drift, Newt had been averting his mental gaze from Hermann for fear he would return it.

The mortifying ordeal of the drift.

Now he lasered his full focus on the Hermann in his head.

By honing in on Hermann, Newt could almost ignore the cacophonous whispers of hive mind. Almost. It was like humming loudly whenever Hermann got too pedantic. Newt could still hear him, but it was more about the principle of ignoring him than the de facto state of ignorance.

Newt followed the ghost of Hermann through his own neural pathways, like chasing a very tall rabbit. Harvey, maybe, or Frank.

Every living creature on Earth dies alone. Kelly, Richard. Donnie Darko. Newmarket Films, 2001

Newt liked Donnie Darko. He wondered if Hermann would too.

Probably not.

Hermann liked Frankenstein.

And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper. Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein, Introduction, 1831.

Like the Jaegers. The monsters of our own making. Death to the imposter-syndrome.

Whoever had christened the Jaegers was probably the same chucklefuck that thought it was a good idea to name their base of operations anything with the word ‘shatter’ in it.

At least Hermann's favorite film adaptation was Young Frankenstein, but that was, like, objectively the best one.

“Hearts and kidneys are tinker toys! I am talking about the central nervous system!" Brooks, Mel, et al. Young Frankenstein, Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 1998.

Hermann liked…

Hermann liked Downton Abbey.

…Yeah, Newt had nothing.

Hermann liked Hegel, and there was something in dialectical philosophy that was blowing dust on the laser grid of Newt’s mental landscape.

We call dialectic the higher movement of reason in which utterly separate terms pass over into each other spontaneously. Hegel, G. W. F., The Science of Logic, 1812.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy was developed in the late 80s specifically to treat Borderline Personality Disorder.

BPD wasn't even added to the DSM-III until 1980, and for almost a decade after that, it was considered untreatable. It was a life sentence. Except when it was a death sentence.

Then Marsha Linehan developed Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and suddenly it wasn’t so untreatable anymore.

Newt didn't have time for full-fidelity DBT, so his therapy had been a little more autodidactic in nature, but it was ultimately about finding a middle ground in the black and white thinking that resulted from such extreme emotional experiences. Newt was still salty that he couldn't say the phrase ‘shades of gray’ without invoking that unfortunate representation of BDSM culture. When it came to consent, Christian Grey was almost as bad as the cultists.

Anyway, Hermann's Hegelian née Kantian dialectic was also a rejection of dichotomies, not unlike earlier Derridean deconstruction of Saussure’s significant binaries. Non-binary. They/them.

Maybe Newt should change his pronouns to, “Yes/And?”

Labels could make you aware of more options, but eventually you would see there were more options than there were labels. Dichotomies were reductive, especially when applied to human beings. Almost nothing was all or nothing.

Abstract, negative, concrete.

Thesis, synthesis, antithesis.

Scientist, hive mind… hive mind.

Newt had never felt so skinless. He had to sew himself a new one, like the women at Playtex, who went from making girdles and bras to spacesuits. They beat out three major defense contractors to produce the suits for Apollo 11.

Hermann loved those ladies, so now Newt did too. He'd never even heard of them before, but Hermann had memorized names, even though so many of them went unidentified, their work considered trivial in history’s biased gaze.

Eleanor Foraker, Iona Allen, Francine Burris, Henrietta Crawford, Velma Breeding, Hazel Fellows. The astronauts had stars and multimillion dollar inertial navigation systems, but those women had only pins to guide them.

On a less endearing note, Hermann liked Nietzsche, although Newt was starting to suspect that he was just homesick.

It was still a surprise, coming from Hermann Handwriting-of-God Gottleib, but Newt knew that relationships with god were never so simple. His relationship with someone's gods was now incredibly complex indeed.

Anyway, Hermann liked Nietzsche because of something, something, Übermensch, because of course Hermann thought his own humanity was something to be overcome.

Maybe Newt just wasn't getting it. He had never been as good at the purely theoretical stuff as Hermann, and he wasn't exactly working at full capacity.

He was definitely over capacity.

Whatever. Irrelevant. If the Übermensch was some sort of Platonic ideal of humanity, then it could only ever be a false idol. Perfection was a myth. Perfection was a way to ruin something good enough, which was all Newt could ever hope to be.

Playing by the rules was ridiculous, when everyone who wrote them was already dead, and there were plenty of people present, now, in need of rehumanization. Nothing othered, nothing maimed.

Fuck Superman though— Newt’s bone to pick with Nietszche was from Beyond Good and Evil.

Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft, mag zusehn, dass er nicht dabei zum Ungeheuer wird. Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Jenseits von Gut und Böse, ch. 4, no. 146, 1886.

He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.

...

@lastdaysofwar

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greg Foat - The Rituals of Infinity - some nu-jazz leanings on his new album, too

'The Rituals of Infinity' album is inspired by many things. Some titles are named after iconic science fiction books such as The Rituals Of Infinity, A Private Cosmos, The Dark Labyrinth and The World of the Red Sun. Minerva's Owl, on the other hand, is about the Ancient Greek Legend. "The owl of Minerva takes flight only at dusk." so wrote G. W. F. Hegel, the nineteenth century's major philosopher of history. By that, he meant that any given phase of history can be understood only in retrospect — after it's over. A beautifully fitting closing of the album. The album features the legendary Art Themen on Soprano and Tenor Saxophones, and Trevor Walker on Trumpet and Flugel Horn in a fine supportive role harmonising with Katherine Farnden on Cor Anglais. Natcyet Wakili has such a fluid approach to the drums which really makes the album special, alongside Jasper Osbourne on Bass Guitar. Shawn Lee also stopped by the studio with his horror movie classic waterphone - adding some eery atmospheric finishing touches to the album.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Propounding peace and love without practical or institutional engagement is delusion, not virtue.” ― Hegel, G. W. H.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

But the life of the spirit is not the life that shrinks from death and keeps itself untouched by devastation, but rather the life that endures it and maintains itself in it. It wins its truth only when, in utter dismemberment, it finds itself. It is this power, not as something positive, which closes its eyes to the negative, as if it had not seen it; but rather something negative, grasping itself, turning around in itself. The life of Spirit is not the life that is scared of death and spares itself destruction, but rather that life which endures it and maintains itself in it.

G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Napoleon and Revolutionary Imperialism

Thursday 15 August 2024 is the 255th anniversary of the birth of Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 05 May 1821), who was born in the city of Ajaccio on the island of Corsica on this date in 1769.

Napoleon was one of the most consequential men of Western history. As such, he has served as a symbol and as an historical ideal, in Huizinga’s sense. But Napoleon meant many things to many men, so his use as a symbol is always ambiguous, and the many meanings that have been associated with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire have never converged on a single vision of history.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Text post: https://geopolicraticus.substack.com/p/napoleon-bonaparte-and-revolutionary

Video: https://youtu.be/kQJ8UEZM6_s

Podcast: https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/R3xMDcrb6Lb

#philosophy of history#youtube#Napoleon Bonaparte#Bonapartism#Jacobinism#historical ideals#empire#revolution#French Revolution#Carl von Clausewitz#Francis Parker Yockey#G. W. F. Hegel#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

In English translations of the early nineteenth-century writings of German idealist G. W. F. Hegel, Aufhebung is sometimes translated as “positive supersession,” and intriguingly, this rather stiff bit of jargon unites the ideas of lifting up, destroying, preserving, and radically transforming, all at once. These four components can be illustrated with reference to slavery, the earliest example of a radical cause calling itself “abolitionist” in history. The successful global fight for the abolition of slavery meant that the noble ideal of humanism, trumpeted in the French Revolution, was simultaneously lifted up (vindicated), destroyed (exposed as white), preserved (made tenable for the future) and transformed beyond recognition (forced to incorporate those it had originally excluded). Slavery was overturned in law and eventually more or less done away with in practice. What we must understand, however, is that our very capacity to understand these events was generated by them. In the “before” times, the ideals that governed slave-trading societies really were human rights, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The world manifested those ideas as they existed then, until, at the end of an enslaved person’s rifle, the self-styled inventors of “freedom” in these societies learned at last what real freedom (a more real freedom, for the time being) looked like. Humanism: negated, remade, born, buried, prolonged. By winning the struggle against slavers, abolition gave the lie to those societies, and supplied those brave ideals with their first-ever shot at becoming more than words.

Sophie Lewis in Abolish the Family

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death, if that is what we wish to call that non-actuality, is the most fearful thing of all, and to keep and hold fast to what is dead requires only the greatest force. Powerless beauty detests the understanding because the understanding expects of her what she cannot do. However, the life of spirit is not a life that is fearing death and austerely saving itself from ruin; rather, it bears death calmly, and in death, it sustains itself. Spirit only wins its truth by finding its feet in its absolute disruption. Spirit is not this power which, as the positive, avoids looking at the negative, as is the case when we say of something that it is nothing, or that it is false, and then, being done with it, go off on our own way on to something else. No, spirit is this power only by looking the negative in the face and lingering with it [tarrying with the negative]. This lingering is the magical power that converts it into being. – This power is the same as what in the preceding was called the subject, which, by giving existence to determinateness in its own element, sublates abstract immediacy, or, is only existing immediacy, and, as a result, is itself the true substance, is being, or, is the immediacy which does not have mediation external to itself but is itself this mediation.

G. W. F. Hegel - Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit - pg. 20 - 21. (Emphasis mine)

9 notes

·

View notes