#forerunner trilogy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Forthencho has been dead for 100,000 slutty, slutty years

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay.

Since some Halo fans missed the point.

I’m going to make it clear:

THE MANTLE OF RESPONSIBILITY IS NOTHING BUT AN IDEA!!!!!!

An idea invented by the Precursors and adhered to by both them and the Forerunners.

At the most it is a test! A test which all have failed!

An idea!

An excuse to impose one’s will over the galaxy!

Nobody is worthy or deserving of it.

That doesn’t mean we can’t be better but the Mantle is not the means by which one ought to do it.

Greg Bear implied and all but stated this in the Forerunner trilogy novels.

And Epitaph has only reinforced this even further. With the Ur-Didact all but admitting it. (Even if it took him a thousand centuries)

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#halo lore#deep lore#gaming#literature#microsoft#bungie#343 industries#halo studios#mantle of responsibility#forerunner#forerunner trilogy#greg bear#precursors#vent post#media literacy#or lack thereof#media illiteracy#missing the point#humanity#misunderstanding

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOCAL INHABITANTS 100,000 YEARS AGO???

POSSIBLY MODERN AND NEANDERTHAL HUMANS???

SO I NEVER REALIZED WE HAD THIS BEFORE THE FORERUNNER TRILOGY

I thought it was only halo 3 terminals I completely forgot about this part of evolutions

Absolutely awesome seeing how far back the roots of this lore goes

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Gamelpar

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ASFGDDYXFJFFH

FLORIAN

FLORIAN

Day Chaser Makes Paths Long Stretch Morning Riser

My favorite florian

Melon shop next to the Flórián shopping center, Budapest, 1989. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

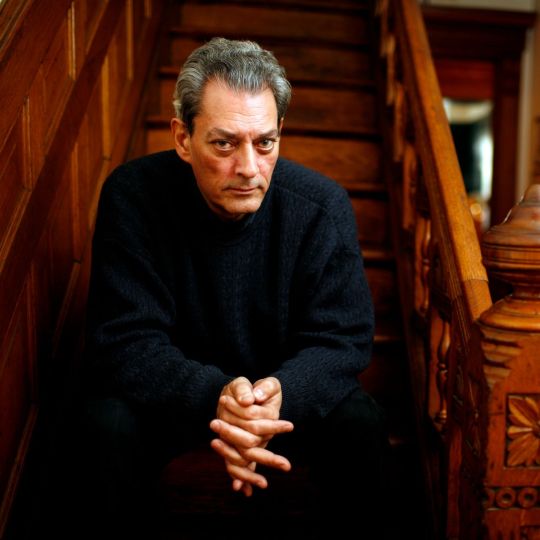

Paul Auster

Author of The New York Trilogy who conjured up a world of wonder and happenstance, miracle and catastrophe

The American writer Paul Auster, who has died aged 77 from complications of lung cancer, once described the novel as “the only place in the world where two strangers can meet on terms of absolute intimacy”. His own 18 works of fiction, along with a shelf of poems, translations, memoirs, essays and screenplays written over 50 years, often evoke eerie states of solitude and isolation. Yet they won him not just admirers but distant friends who felt that his peculiar domain of chance and mystery, wonder and happenstance, spoke to them alone. Frequently bizarre or uncanny, the world of Auster’s work aimed to present “things as they really happen, not as they’re supposed to happen”.

To the readers who loved it, his writing felt not like avant-garde experimentalism but truth-telling with a mesmerising force. He liked to quote the philosopher Pascal, who said that “it is not possible to have a reasonable belief against miracles”. Auster restored the realm of miracles – and its flip-side of fateful catastrophe – to American literature. Meanwhile, the “postmodern” sorcerer who conjured alternate or multiple selves in chiselled prose led (aptly enough) a double life as sociable pillar of the New York literary scene, a warm raconteur whose agile wit belied the brooding raptor-like image of his photoshoots. For four decades he lived in Brooklyn with his second wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt.

The fortune that drives his stories played a part in his own career. City of Glass (1985), the philosophical mystery that launched his New York Trilogy and his ascent to fame, appeared from a small imprint after 17 rejections. Though the novel helped build his misleading reputation as a cool cult author, a moody Parisian existentialist marooned in noir New York, it had a pseudonymous forerunner that shows another Auster face.

Squeeze Play, published under the pen-name “Paul Benjamin” in 1982, is a baseball-based crime caper. Its disconsolate gumshoe, Max Klein, muses that “I had come to the limit of myself, and there was nothing left.” If that plight sounds typically Auster-ish, then even more so was the baseball setting. Auster adored the sport and played it well: “I had quick reflexes and a strong arm – but my throws were often wild.” In a much-repeated tale, he failed aged eight to get an autograph from his idol Willie Mays, of the New York Giants, because he had not brought a pencil. Auster “cried all the way home”.

Auster’s work is more deeply embedded in the mid-century national culture that fuelled the novels of his elders, such as Philip Roth and John Updike, than some advocates appreciated. His fables of identity-loss and alienation have emotional roots in the mean, lonely city streets he knew when young. He once insisted, to fans and scoffers who labelled him an esoteric “French” or European coterie author, that “all of my books have been about America”.

He was born in Newark, New Jersey (also Roth’s hometown). His parents, Queenie (nee Bogat) and Samuel Auster, children of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe, set him on a classic American path of upward mobility through education while remaining, to their son, opaque. The Invention of Solitude (1982) was Auster’s haunting attempt to imagine the life of his impenetrable father. Ghostly fathers would pervade his work. As would sudden calamity. When, aged 14, he witnessed a fellow summer-camper struck dead by lightning, the event became a paradigm for the savage contingency of life, “the bewildering instability of things”. His later novel 4321 (2017), which revisits this formative trauma, cites the composer John Cage: “The world is teeming: anything can happen.” In Auster’s work, it does.

At Columbia University in New York, he studied literature, and took part in the student protests of 1968, before moving to Paris to scrape a living as a translator of French poetry (a surrealist anthology was his first published work). He lived – literally in a garret – with the writer Lydia Davis, and returned in 1974 with nine dollars to his name. Back in New York, they married, but were divorced in 1978, a year after the birth of their son, Daniel. Poetry collections followed, but Auster’s thwarted efforts to secure a decent livelihood meant that he gave his ruefully funny 1997 memoir Hand to Mouth the subtitle “a chronicle of early failure”.

In 1982, he married the novelist and essayist Hustvedt (who recalled their courtship as “a really fast bit of business”). She became his first reader and trusted guide; they had a daughter, Sophie. Husband and wife would work during the day on different floors of their Park Slope brownstone, and watch classic movies together in the evening. Auster wrote first in longhand, then edited on his cherished Olympia typewriter.

The New York Trilogy (Ghosts and The Locked Room followed a year after City of Glass) made his stock soar, and attracted both celebrity and opportunity.

Auster wrote gnomic screenplays for arthouse films (Smoke, Blue in the Face, both 1995), even directed one (The Inner Life of Martin Frost, 2007). But it was the enigmatic, hallucinatory aura of his fiction – in 1990s novels such as The Music of Chance, Leviathan and Mr Vertigo – that defined his sensibility. Sometimes this trademark style could veer into whimsy or self-parody (as in Timbuktu, 1999, with its canine hero) although stronger novels – such as The Brooklyn Follies (2005) – always pay heed to the pulse, and voice, of contemporary America. Keenly engaged in current affairs, Auster held office in the writers’ body PEN, deplored the rise of Donald Trump, and spoke of his country’s core schism between ruthless individualism and “people who believe we’re responsible for one another”.

Auster the exacting aesthete was also a yarn-hungry storyteller. If he edited a centenary edition of Samuel Beckett – a literary touchstone, along with Hawthorne, Proust, Kafka and Joyce – he also compiled a selection of unlikely true tales submitted by National Public Radio listeners. They revealed the strange “unknowable forces” at work in everyday life. In his epic novel 4321, the formal spellbinder and social chronicler meet. It sends a boy born in New Jersey in 1947 down four separate paths in life: an Auster encyclopedia, ingenious but heartfelt too. Bulk and heart also characterised his mammoth 2021 biography of the Newark-born literary prodigy Stephen Crane, Burning Boy.

The ferocity of fate that scars his work gouged wounds into Auster’s life as well. Daniel succumbed to addiction, accidentally killed his infant daughter with drugs, and died of an overdose in 2022. Auster’s cancer diagnosis came in 2023. Prolific and versatile as ever, in that year he still published both an impassioned essay on America’s firearms fixation (Bloodbath Nation) and his farewell novel, Baumgartner. Its narrative hi-jinks dance smartly over a bass chord of grief.

Auster populated a literary planet all his own, where the strange music, and magic, of chance and contingency coexist with love, dream and wonder. In Burning Boy, he wonders why Crane’s output now goes largely unread, although “the prose still crackles, the eye still cuts, the work still stings”. After 34 books, so does his own.

Auster is survived by his wife and daughter, and a grandson, and by his sister, Janet.

🔔 Paul Benjamin Auster, writer, born 3 February 1947; died 30 April 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have an inspiration for the Futuristic/high tech themes and designs in your setting? You mentioned Sonic once, but I wonder if there's more

Sonic is a big one for sure. I’d say the other primary ones are probably Portal 2 and the Halo Trilogy. I’m heavily influenced by the early forerunner architecture as well as the gritty industrial vibe of the human tech in Halo

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro post time :o

Hi I'm Glass, 30F (she/her). I spend way too much time with worldbuilding or story ideas or exploring themes SIGH. I'd enjoy building/upgrading my computers if I had the money and space for it >:( I also find driving (without traffic or a ton of stoplights) while listening to music super relaxing (eg my story playlists)

Bluesky

AO3

Dragon's Dogma 2 screenshottery

I really like to draw/write about Narinder/The One Who Waits 🙃

I've got four Cult of the Lamb AUs/storylines on a sliding scale of dark to lighthearted:

Depression Quest (fic, cw: abuse, self harm, depression)

The Courtship of the God of Death (fic, cw: unhealthy/toxic relationship, obsession, jealousy, manipulation, violence, gore, emotional/psychological abuse)

Restart (cw: violence, gore)

19th Century AU

More on the AUs below the cut

Interests: Dragon's Dogma, Cult of the Lamb, Star Wars Outlaws, Final Fantasy IX, Neon Genesis Evangelion, No Man's Sky, Rune Factory 4/5, Skyrim, Fallout New Vegas/4, Nier Replicant/Automata, pre-Destiny Bungie lore + Destiny's Book of Sorrows and a few other bits + Halo's Forerunner Trilogy

My name comes from something I wrote for my oc worldbuilding project:

He pressed against the glass of time, feeling it crack beneath his fingers. He stepped into the tides of space, seeing the water part for his feet. … He broke through the glass, looked down at them again. … He swam through the rising tides to a new world.

Depression Quest:

My very First Idea™ for Cult of the Lamb. It follows the canon ending of Lamb conquering The One Who Waits. Essentially, the Lamb turns Narinder into a trophy husband, and Narinder does not have a good time.

This is my darkest au and includes things such as abuse, self harm, depression, etc. My favorite thing is the fact that Ratoo and Narinder eventually become friends. I've written a chapter but the fic won't be updated often. Tag: #cotl depression quest

The Courtship of the God of Death:

This is the fic I've published on AO3. Follows the alternate ending of The One Who Waits regaining the Red Crown and his freedom, but instead of sacrificing the Lamb, he accepts their proposal to become his Consort and rule over the Cult by his side. He enjoys his victory, deals with the Lamb's affection for him, and processes what happened between he and his siblings.

It starts out lighthearted, then becomes a descent into darker themes such as obsession, jealousy, manipulation, emotional/psychological abuse, and the toxic relationship between the Lamb and Narinder. It also includes some violence and gore. It borrows some stuff from Depression Quest, and involves the majority of my headcanons/worldbuilding. Tags: #cotl courtship, #cotl the courtship of the god of death, #the courtship of the god of death, #cult of the lamb the courtship of the god of death

Restart:

Follows the alternate ending of The One Who Waits sacrificing the Lamb and regaining the Red Crown. He gets bored and decides to time/worldjump to another version of The Lands of the Old Faith, replacing Ratau/the Lamb as the crusader against the Bishops. Too bad he's a thousand years out of practice.

This is more slice of life and includes Narinder and Lamb arguing like a married couple but there's some drama in there. It does include violence and gore since Narinder does have to go on his Crusades and fight his siblings. This one does not have a fic written, it's more ideas I've doodled. Well, I did have a chapter written, but it may be posted as a separate piece instead.

tl;dr Narinder goes New Game+ and becomes the player character (but he really sucks at it). Tag: #cotl restart

19th Century AU:

Created after watching of Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, and Emma. It follows Prince Narinder of the Kingdom of the Old Faith Amenthes, investor of Ratau and Ratoo Trading Company, who has just moved into Acheron Estate. He bumps into the Lamb by chance while meeting with Ratau, and hires her as his servant after being intrigued by her fiery personality.

It's a slice of life and is a silly, self-indulgent AU written as if it was a screenplay. Maybe I'll post the scenes on AO3 even though they're out of order. Tag: #cotl 19th century AU

Also made a concept playlist (ask box post with song list, WIP) on the AUs because I'm absolutely nuts

I've also written mad ideas and wrote a few bits on an OC worldbuilding thing I've had since like 2010 or something no idea if people might be interested in it and it's as convoluted as the Kingdom Hearts series soooo Tag: #three kids and their pet ghost

#intro post#cotl 19th century au#cotl courtship#cotl depression quest#three kids and their pet ghost#introduction#introductory post#pinned post#pinned intro#blog intro#cotl the courtship of the god of death#the courtship of the god of death#cult of the lamb the courtship of the god of death#cotl restart#cotl restart au

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

One of us one of us one of us

"I need to be more insane about the Forerunner trilogy" Join us! Join us!! :D

I have so much halo insanity already....... 💀

(MAYBE SOMEDAY I'll get to these ambitions I just have so many)

#the mantle of responsibility of being insane about forerunner trilogy rests on your shoulders zita#/joking

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh YEAH?????!!!!

Well at least I didn’t DAMN the entire galaxy for the purposes of REVENGE TEN MILLION YEARS OLD!!!!!!!!!!

You stupid SHIT!!!!!!!

*FOR LEGAL REASONS THIS IS A JOKE!*

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#my poor attempt at a joke#halo#forerunner trilogy#precursors#the flood#gravemind#the primordial#greg bear#Kelly Gay#halo epitaph#cosmic horror#microsoft#343 industries#halo studios#revenge ten million years old#revenge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

*notices your URL*

Gamelpar…

As in Old Father?

Of the Tudejsa?

Is your URL a Halo: Primordium reference?

Or am I looking too deeply into this and seeing patterns in things that aren’t there? (A trait all humans share)

Sorry if this is out of nowhere and comes across as prying, it just stuck out to me.

it is INDEED a halo reference from primordium, my friend you're not out of your way at all!!

back in my old halo obsession days, my tumblr mutual @monitorchakas introduced me to the characters of the forerunner trilogy, and the character Gamelpar aka the first shitposter and his wisdom has forever stayed with me

my tumblr blog title is also inspired by him and his very wise words

he's an obscure little gremlin character in the halo franchise and i love him <3

#IM NEVER CHANGING MY NAME EVER#i aspire to be just as weird and wise as him#love to see that someone is enough into halo that they recognize an obscure character from it!!!#asks#gamelpar

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking of the recent Halo books I've listened to

Last Light--i liked the main characters, the Gammas were a delight and it was weirdly nice spending time with Fred even tho I didn't care about him in the early books at alllll. Interesting premise and setting, for the most part kept moving.

Smoke and Shadow-- I was originally going to skip cuz I know some of the dumb stuff that happens in later books but the short story from Fractures sold me. It was short and sweet and I really ended up liking Rion, and New Tyne is my favorite setting from the novels so it was nice to spend a bit of time there again.

Fractures--i skipped the forerunner stories cuz I skipped the Forerunner trilogy, but I mean hey I like a short story collection. My favorites were the Last Light follow up, fun premise, kept me on my toes, and the Envoy 'prequel.' Didn't enjoy it as much as the first short story book but still alright.

Envoy--im not finished so maybe it'll sell me, but it's just alright. Cole Protocol is my favorite of all the novels so I was excited to see Buckell writing again, but it's just alright. I'm enjoying it but it's a bit plodding and it lacks the intrigue and mystery that made Cole Protocol so good for me. The Gray Team chapters are the most interesting parts for me, which feels flipped cuz they were my least interesting part of Coke Protocol to me, the human characters and the Covenant plot really pulled me in in that on.

New Blood--eh idk where to place this. It's short but fine. The Veronica/Buck stuff is good. The main story is eh.

Broken Circle--i don't have much to say about it. It was fine, I enjoyed myself. I always like seeing San Shayuum and their weird culture. Not the most interesting book but if it sounds interesting to you, id give it a shot.

Hunters in the Dark--👎👎👎👎👎👎👎 BORING

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

could you give a shortlist of halo novels worth reading

I would say obviously The Fall of Reach ranks number one (it’s genuinely good and the bit where that twink from polygon everyone loves makes fun of it for using dramatic irony in a throwaway line (bizarre bit of criticism from him, I have to assume he doesn’t read) is dumb). I would also throw Ghosts of Onyx in there, especially because for some dumbass reason that book becomes a lynchpin for understanding the extremely loose narrative arc of the 343 Industries games. First Strike is a fun read, and the two Master Chief prequels by Troy Denning are also good. Actually, I would say you can basically read all of Denning’s Halo books and have a good time. Avoid the Karen Traviss series like it’s an STD, any affection I had for her from the Republic Commando and Gears of War books was instantly lost with her Kilo-5 stuff.

Oh and also I recommend the Forerunner Trilogy not even just cause they’re good Halo books but because they’re very good sci fi books in general. Very different feeling from the rest of setting, very interesting subject matter, and Greg Bear does a great job exploring the like. More fantastical and crazy sci fi elements of what the Forerunners were capable of. They get up to some wild shit in the trilogy.

#I actually really haven’t read that many Halo novels#I fell off video game books after high school and only recently got back into them

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, the Black Jewels Trilogy

Saw these books recommended in a thread about adult sexy fantasy books, and my brain went ??? Wait. They weren’t that adult???? They had dark themes, but they were fluff.

I’d almost forgotten about them. I read them about 15 years age (wat!) in high school. My friends at the time peer pressured me into it. They would tell me about all their favourite scenes and squee about them as we whiled away lunches in the stairwell, which both spoiled a lot of the fun of reading them the first time and I still remember which scenes were spoiled as I did my reread.

I enjoyed them well enough at the time, because they were dark and a bit gory and a bit sexy and I was ravenous as a teen for anything with sex, violence, and especially BDSM. I grew out of them by uni.

So the thread was specifically recommending them as an adult alternative to the trendy ACoTaR books by Sarah J Maas that I have never read and don’t intend to. I have since learned that some hold the opinion that SJM plagiarized or otherwise cribbed heavily from Black Jewels. (The other alternative offered in that thread were the Kushiel books, which I would agree are more adult, both in subject matter and style.)

On a reread, I think my initial impression that these books are more for teens—or people who specifically want and need an id-based power fantasy—holds up. Content warnings for literally all the standard bogeyman: rape, pedophilia, implied cannibalism, torture, etc etc. It dives shallowly into all the dark stuff in order to get to the revenge fantasy at the heart of the series.

Extensive spoilers under the cut. There’s a few things I liked, but there’s a lot more I didn’t enjoy about it too. (And it’s not because of any of the content warning stuff above.)

I wrote my review of the first three books before reading any of the sequels. Sequel reviews will be forthcoming.

The Setting

The worldbuilding is a mess. I have no idea how the economy works or why there are even nonBlood ‘landens’ (basically magicless folk) at all when they Literally. Never. Show. Up.

Yet! For all that! It is so rare to see a matriarchy in a fantasy setting that I will forgive the cardboard worldbuilding and pretend like economics doesn’t matter it’s just fantasy. I love that the greatest power is downwards, the Darkness rather than the heavens. Dark stuff more powerful. It’s neat! Like even today the books feel different, even when they’re extremely 2000s aesthetically. Goth vibes ftw. Less good is the gender essentialism and the caste system, which feels like a forerunner to A/B/O in some ways.

Basically, like in A/B/O, everyone has like a secondary biological gender that determines their rank in the hierarchy. So women who are born Queens are biologically meant to rule, and men are drawn to serve them. (It’s stupid, but I respect the inherent service kink aspect.) Some males are Warlords, who are more aggressive, and some men are even higher caste as Warlord Princes, who are ‘predators’ who want to murder ppl all the time, but they’re supposed to be controlled by the women I guess. They're emotionally immature alpha males. Yuck.

I still have no real idea how the fuck Terreille and Kaeleer are different tbh, one just has sentient animals? Are they different dimensions?? The physicality of the environment in this book is like wisps of smoke. Stuff just appears, usually when it needs to, and then goes away again, much like how the magical protagonists are always calling and vanishing objects.

Daughter of the Blood

For a trilogy with a deeply repetitive, emphatic style that over-relies on (dorky) catchphrases (‘and the Blood will sing to Blood,’ ‘everything has a price,’ ‘Mother Night’) each book does have a unique flavour and its own problems.

Weirdly, the thing I hated the most about the first book was the random fatphobia. I never even noticed it as a kid, but almost every time a fat character is introduced they’re a gross dude and likely a pedophile. Don’t like it, tired of seeing it, stop. I’m not even going to forgive the series for being from the early 2000s. I don’t care. Cut it out. At least it only happens in the first book.

The Mary-Sue (she really is! I mean that with affection!) Jaenelle is a child in this book, and her main problems in life are getting sent to a mental institution called Briarwood that is run by pedophiles. We also—at no point ever in the books—get her POV, so a lot of the horror is mitigated by how much the details are glossed over. I think that was meant to be more horrifying but the author isn’t good enough at building atmosphere to make that work. The book chooses a couple specifically horrible situations and then hammers into them in a way that feels both schlocky but also makes the world and the situation feel smaller. I don’t like the way repetition is used in these books. It’s certainly a choice but it’s one that drives the nuance out of book. Almost every villain in this book is a rapist, which makes the rape feel cheap by the end—and I don’t think cheapening it was the intention.

Yet, to be honest, I think this is the strongest book of the three. I actually really like the beginning, with Tersa being crazy and giving prophecies. I don’t know, the writing just draws me in somehow. It’s not great writing, I want to be clear. It’s got nothing on, idk, Tanith Lee. But it is extremely readable and compelling. I was having a good time.

Also, Lucivar and Daemon, like, kiss? And that is just about the only gay thing that you will see in the books until Daemon fakes raping his father in the third book. It is unrelentingly heterosexual otherwise. But I think I was hooked early on as a teen hoping for some gay action. I was disappointed at the time and I’m disappointed now.

This is also the book with probably the most sex and violence. Men are castrated on screen a couple times, there’s explicit cannibalism of one of the other children at Briarwood, one of our viewpoint characters is an assassin, etc etc. Much bad sex happening. Daemon and Lucivar, the hot dudes who are brothers, have been sex slaves for like 1700 years which is objectively hilarious that is SUCH an absurd amount of time to just... be more powerful (aka have darker Jewels) than any of your slavers and just not gotten free? Even with magical cock rings that control them, it's still so stupid.

Also, our main character is actually their dad, Saetan (I WILL NEVER BE OVER THESE NAMES) who is like 50k years old? That makes me giggle so much. That’s so old. Why. Honestly props to Anne Bishop, she really just went for it. I have so much respect for how batshit absurd everything is.

Honestly I just kinda like the first book? It’s paced a lot better than the other ones, it’s dark and ridiculous and full of bad things happening. Jaenelle reminds me of a friend of mine, oddly enough. She’s probably tolerable because we never get her POV.

I also liked Daemon and Jaenelle’s relationship in this one. Under the worldbuilding power fantasy terms of this setting, Jaenelle is literally made up of the dreams of people in the world, and Daemon’s dream was to be the lover of the Most Powerful Matriarch Ever, who in the book is called ‘Witch.’ So meeting her as a kid he’s constantly bombarded by his attraction to her spirit/power/Witch-self, whatever. But she’s a kid and he’s Very Not Into That. He and Saetan are constantly respecting her consent at every opportunity, so it doesn’t squick me out in the slightest.

Because you know, at that age (12-14), I would have killed for an ancient powerful lover who is The Hottest Guy In All The Realms to be all but overcome with lust for me and yet completely absolutely in service to my every need and desire.

It’s a power fantasy, yo.

Anyway the next two books will completely kill any interest I have in their relationship so really, Daughter of the Blood could have ended here and I would have been satisfied.

Heir to the Shadows

Wow, does this one have middle book syndrome. It’s a slog. Someone out there probably likes it. One of the scenes my high school friends liked is the introduction of the Arcerian cat Kaelas where he squashes the Sceltie puppy Ladvarian. I remember them telling me about it with glee. It’s cute, but not enough to save this book.

Everytime a conflict happens it’s almost instantly resolved. Jaenelle grows up, Saetan spoils her, she has friends. All the characters feel really one note. There is almost no sex in this book, but there is some gore. The extremely boring villains, Dorothea and Hekatah, who are basically the same person except one of them is undead (‘demon-dead’), do some violence. Our protagonists do more violence. There’s a unicorn genocide. I can’t keep any of the characters that are in Jaenelle’s court straight (except for Karla and the aforementioned cat and puppy).

Oh, Daemon’s just insane for the whole book, and I ended up skimming all his sections because nothing happened in them.

That sure was a book. Took me longer to read than the other two combined.

Queen of the Darkness

Back to a compelling read, somehow. I blasted through it.

A major issue I have with this series is about how power is framed. Might makes right. The good guys happen to be more powerful, so they can unleash their often bloody revenge, which is always framed as a good thing, a triumph. And also, no one just talks to each other, because bad guys are bad and good guys are good. There is no real compromise, and no nuance.

Like, Bishop is writing a matriarchy, but instead of, idk, expanding on that idea, she just kinda writes the same power imbalances that exist in our world except more villains are women, which instead of feeling empowering or whatever reeks of internalized misogyny. Yeah, I get it, women are bitches and oppressing the mens, so then the sad menz all rape vulnerable women. So it’s a patriarchy, actually, with the Queen-caste women as figureheads. WHY YOU DO THIS.

Honestly I find the ‘might makes right’ part much more problematic than any inclusion of sex slavery, unicorn genocide, or pedophilia. All the latter are perpetrated by villains; what's the excuse for the good guys?

Like this book is more about being righteous and also horny than it is trying to say stuff about politics or whatever, but it’s saying stuff about politics anyway, and what it’s saying is that the most powerful people make the rules. And being an emotionally unregulated nuclear bomb person is perfectly fine so long as you’re the good guy. And frankly, I hate that, and I disagree with it.

And ok, sure, so the Queens are supposed to emotionally regulate their Warlord Princes except that’s mostly just by hoping they hold onto their tempers until they can unleash them in a better direction which doesn’t strike me as real emotional regulation. And who’s supposed to regulate Jaenelle? Just... Jaenelle? Like theoretically the males who serve her, but the way they treat her seems more likely to cause nuclear explosions. She is herself a walking bomb.

Honestly the way males treat females in this book is gross. Men just like overprotect and patronize to the point of infantilizing a woman. And Big Yikes if she so much as gets a period—which is apparently The Worst and makes them unable to use power which THANKS I HATE IT—and it’s just awful, the men treat them like INVALIDS. Not romantic. Didn’t like it as a teen, don’t like it now.

Additionally, I don’t like how emotions and trauma are handled in this. I love a good broken traumatic character, and it's even better if they're powerful and need to navigate not causing harm whilst healing. I lap that shit up. Black Jewels fails me here. All the characters are so fucking one note and so the trauma/healing stuff feels shallow and uninspired.

Additionally, Jaenelle and Daemon are so boring and they’re ‘courting’ each other like high schoolers with zero personality and I hate it. They had better sexual chemistry when she was 12, which is probably just because Daughter of the Blood was the better written book.

Also, they got like a romancey fade to black sex scene? Yeesh.

I DO appreciate that Daemon has no magic healing dick: Jaenelle is still pretty traumatized about stuff after they bone. She’s better about sex, sure, but she’s still upset about being a Queen, etc etc. You know, this series has ooooodles of problems, but I really don’t think Jaenelle is one of them. She works for me. (Although Daemon being a virgin after 1700 years as a pleasure slave? I HATE THAT, that’s stupid. Miss me with that bullshit. At least Jaenelle is never punished by the text for not being a virgin.)

I don’t have much to say about the end. Because we go in knowing Daemon's got back up plans it takes all the tension out of the climax. The story ends with an expected triumph. The book doesn’t set up the idea that Jaenelle will die well enough either, like it’s telegraphed from the first that the Kindred will save her, and then they do. Ok then. Wow, so tense. Much thrill.

So like, I raced through reading this, sure, but it still wasn’t a satisfying read. But it wasn’t a slog. And there were some fun interactions—I enjoyed Surreal and her wolf Graysfang. There were moments.

Honestly this series is so unhinged that despite all the ridiculosity of it, I think I’m coming away feeling weirdly affectionate towards it? It’s bad, the alpha male tropes are nauseating, the matriarchy failed hard, and it’s repetitive as fuck. I’ve been thinking about this series for weeks now, and I have no idea why I find it compelling! It’s infuriating! Maybe it’s compelling because it’s infuriating.

In conclusion: I guess I’m going to read all of this garbage and yell about it. Stay tuned for the sequels.

#Amber reads the Black Jewels series#black jewels trilogy#book review#sort of more like unhinged book screaming#there's like so much other shit I could probably add to this screaming but like it's long enough#and the sequels really dig into many weaknesses#so ... yeah#why did I do this to myself

23 notes

·

View notes