#fermented

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Seven yoghurt balls on a plate drizzled with olive oil. The one in the center is plain; the others are covered in mint, toasted sesame seeds, ground sumac, za'tar, crushed red chili pepper, and nigella seeds. End ID]

لبنة نباتية / Labna nabatia (Vegan labna)

Labna (with diacritics: "لَبْنَة"; in Levantine pronunciation sometimes "لَبَنَة" "labanay") is a Levantine cow's, sheep's, or goat's milk yoghurt that has been strained to remove the whey and leave the curd, giving it a taste and texture in between those of a thick, tart sour cream and a soft cheese. The removal of whey, in addition to increasing the yoghurt's tanginess and pungency, makes it easier to preserve: it will keep in burlap or cheesecloth for some time without refrigeration, and may be preserved for even longer by rolling it into balls and submerging the balls in olive oil. Labna stored in this way is called "لبنة كُرَات" ("labna kurāt") or "لبنة طابات" ("labna ṭābāt"), "labna balls." Labna may be spread on a plate, topped with olive oil and herbs, and eaten as a dip for breakfast or an appetizer; or spread on kmaj bread alongside herbs, olives, and dates to make sandwiches.

The word "labna" comes from the Arabic root ل ب ن (l b n), which derives from a Proto-West-Semitic term meaning "white," and produces words relating to milk, yoghurt, nursing, and chewing. The related term "لَبَن" ("laban"; also transliterated "leban") refers to milk in Standard Arabic, but in Levantine Arabic is more likely to refer to yoghurt; a speaker may specify "لَبَن رَائِب" (laban rā'ib), "curdled milk," to avoid confusion.

Labna is a much-beloved food in Palestine, with some people asserting that no Palestinian home is without a jar. Making labna tabat is, for many, a necessary preparation for the winter season. However, by the mid-2010s, the continuation of Israel's blockade of the Gaza strip, as well as Israeli military violence, had severely weakened Gaza's dairy industry to the point where almost no labna was being produced. Most of the 11 dairy processors active in Gaza in 2017 (down from 15 in 2016) only produced white cheese—though Mustafa Eid's company Khalij had recently expanded production to other forms of dairy that could be made locally with limited equipment, such as labna, yoghurt, and buttermilk.

Dairy farmers and processors pushed for this kind of innovation and self-sufficiency against deep economic disadvantage. With large swathes of Gaza's arable land rendered unusable by Israeli border policing and land mines, about 90% of farmers were forced by scarce pasture land and low fodder production to feed their herds with increasingly expensive fodder imported from Israel—dairy farmers surveyed in 2017 spent an estimated 87% of their income on fodder, which had doubled in price since 2007. Cattle were thus fed with low quantities of, or low-quality, fodder, resulting in lower milk production and lower-quality milk.

Most dairy processors were also unable to access or afford the equipment necessary to maintain, upgrade, or diversify their factories. Since 2007, Israel has tightly restricted entry into Gaza of items which they consider to have a "dual use": i.e., a potential civilian and military function. This includes medical equipment, construction materials, and agricultural equipment and machinery, and impacts everything from laboratory equipment to ensure safe food supplies to packaging and labelling equipment. Of the dairy products that Gazan farmers and processors do manage to produce, Israel's control over their export can cause huge financial losses—as when Israel prohibited the export of Palestinian dairy and meat to East Jerusalem without warning in March of 2020, costing estimated annual losses of 300 million USD.

In addition to this kind of economic manipulation, direct military violence threatens Gaza's dairy industry. Mamoun Dalloul says that his factory was accused of holding rockets and subsequently bombed in 2008, 2010, 2012, and again in 2014, resulting in repeated moves and the loss of the capability to produce yellow cheese. The Israeli military partially or totally destroyed 10 dairy processing factories, and killed almost 2,000 cows, during its 2014 invasion of Gaza, resulting in an estimated 43 million USD of damage to the dairy sector alone. Damage to cow-breeding farms in 2014 reduced the number of dairy cows to 2,600, just over half their previous number. Damage to, or destruction of, wells, water reservoirs, water tanks, and the Gaza Power Plant's fuel tank exacerbated pre-existing problems with producing cattle feed and with the transportation, processing, and refrigeration of dairy products, leading to spoiled milk that had to be disposed of. Repeated offensives made dairy processors reluctant to re-invest in equipment that could be destroyed at any time.

Israeli industry profits by making Gazan self-sufficiency untenable. Israeli goods entering Palestine are not subject to import taxes, and Israeli dairy companies are not dealing with the contaminated water, limited electricity, high costs of feed, out-of-date and expensive-to-repair equipment, and scarce land (some companies, such as Tnuva, purchase milk from farms on illegal settlements in the West Bank) with which Gazan producers must contend. The result is that the local market in Gaza is flooded with imports that are cheaper, more diverse, and of higher quality than anything that local producers can offer. Many consumers believe that Israeli products are safer to eat.

Nevertheless, Gazans continue building and rebuilding. Despite significant decreases in ice cream factories' production after the imposition of Israel's blockade in 2007, Abu Mohammad noted in 2015 that locally produced ice cream was cheaper and more varied than Israeli imports. In 2017, the amount of dairy sold in 74 shops in Gaza that was sourced locally, rather than from Israel, had increased from 10% to 60%. Ayadi Tayyiba, the region's first factory with an all-woman staff, opened in 2022; it produced cheese, yoghurt, and labna with sheep's milk from affiliated farms. However, demand for sheep's milk products has decreased in Gaza due to its higher production costs, leading the factory to supplement its supply with purchased cow's milk.

The current Israeli genocidal offensive on Gaza has caused damage of the same kind as—though to a greater extent than—previous shellings and invasions. Lack of ability to sell milk that had already been produced to factories, as well as lack of access to electricity, caused an estimated 35,000 liters of milk to spoil daily in October of 2023.

Support Palestinian resistance by calling Elbit System’s (Israel’s primary weapons manufacturer) landlord, donating to Palestine Legal's activist defense fund, and donating to Palestine Action’s bail fund.

Equipment:

A blender

A kettle or pot, to boil water

A cheesecloth or tea towel

Ingredients:

1 cup (130g) cashews (soaked, if your blender is not high-speed)

3/4 cup filtered or distilled water, boiled

1-3 vegetarian probiotic capsules (containing at least 10 billion cultures total)

A few pinches sea salt

More water, to boil

Arabic-language recipes for vegan labna use bulghur, almonds, or cashews as their base. This recipe uses cashew to achieve a smooth, creamy, non-crumbly texture, and a mild taste like that of cow's milk labna. You might try replacing half the cashews with blanched almonds for a flavor more similar to that of sheep's or goat's cheese.

Make sure your probiotic capsules contain no prebiotics, as they can interfere with the culture. The probiotic may be multi-strain, but should contain some of: Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidus, Lactobacillus acidophilus. The number of capsules you need will depend on how many cultures each capsule is guaranteed to contain.

Instead of probiotic capsules, you can use a speciality starter culture pack intended for use in culturing vegan dairy, many of which are available online. Note that starter cultures may be packaged with small amounts of powdered milk for the bacteria to feed on, and may not be truly vegan.

If you want a mustier, goat-ier taste to your labna, try replacing the water with rejuvelac made with wheat berries.

You can also start a culture by using any other product with active cultures, such as a spoonful of vegan cultured yoghurt. If you have a lot of cultured yoghurt, you can just skip to straining that directly (step 5) to make your labna—though you won't be able to control how tangy the labna is that way.

Instructions:

This recipe works by blending together cashews and water into a smooth, creamy spread, then culturing it into yoghurt, and then straining it (the way yoghurt is strained to make labna). It's possible that you could skip the straining step by adding more cashews, or less water, to the yoghurt to obtain a thicker texture, but I have not tested the recipe this way.

1. If your blender is not high-speed, you will need to soak your cashews to soften them. Soak in filtered or distilled water for 2-4 hours at room temperature, or overnight in the fridge. Rinse them off with just-boiled water.

2. Boil several cups of water and use the just-boiled water to rinse your blender, tamper, measuring cups, the bowl you will ferment your yoghurt in, and a wooden spoon or rubber spatula to stir. Your bowl and stirring implement should be in a non-reactive material such as wood, clay, glass, or silicone.

3. Make the yoghurt. Blend cashews with 3/4 cup just-boiled water for a couple of minutes until very smooth. Transfer to your bowl and allow to cool to about skin temperature (it should feel slightly warm if dabbed on the inside of your wrist). If the mixture is too hot, it may kill the bacteria.

4. Culture the yoghurt. Open the probiotic capsules and stir the powder into the cashew paste. Cover the bowl with a cheesecloth or tea towel. Ferment for 24 hours: on the countertop in summer, or in an oven with the light on in winter.

Taste the yoghurt with a clean implement (avoid double-dipping!). Continue fermenting for another 12-24 hours, depending on how tangy you want your labna to be. A skin forming on top of the yoghurt is no problem and can be mixed back in. Discard any yoghurt that grows mold of any kind.

5. Strain the yoghurt to make labna. Place a mesh strainer in a bowl, making sure there's enough room beneath the strainer for liquid to collect at the bottom of the bowl; line the strainer with cheesecloth or a tea towel, and scoop the cultured yoghurt in. Sprinkle salt over top of the yoghurt. Fold the towel or cheesecloth back over the yoghurt, and add a small weight, such as a ceramic plate or a can of beans, on top.

You can also tie the cheesecloth into a bag around a wooden spoon and place the wooden spoon across the rim of a pitcher or other tall container to collect the whey. The draining may occur less quickly without the weight, though.

Strain in the refrigerator for 24-48 hours, depending on the desired texture. I ended up draining about 2 Tbsp of whey.

6. If not making labna balls: Put in an airtight jar, and add just enough olive oil to cover the surface of the labna. Store in the fridge for up to two months.

7. To form balls (optional): Oil your hands to form the labna into small balls and place them on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper. They may still be quite soft.

Optionally sprinkle with, or roll in, dried mint, za'tar, sesame seeds, nigella seeds (القزحة), ground sumac, or crushed red chili pepper, as desired.

Optionally, for firmer balls, lightly cover with another layer of parchment paper and then a kitchen towel, and leave in the refrigerator to dry for about a day.

Place labna balls in a clean glass jar and add olive oil to cover. Retrieve labna from the jar with a clean implement. They will last in the fridge for about a year.

551 notes

·

View notes

Text

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

#panty sissy#diaper sissy#transgender#beta sissy#sissy for bbc#sissy sumesive#transducer#humiliation sissy#artists on tumblr#fermion#nature#gay#sissy graman#ferminization#fermented#classic sissy#classes sissy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

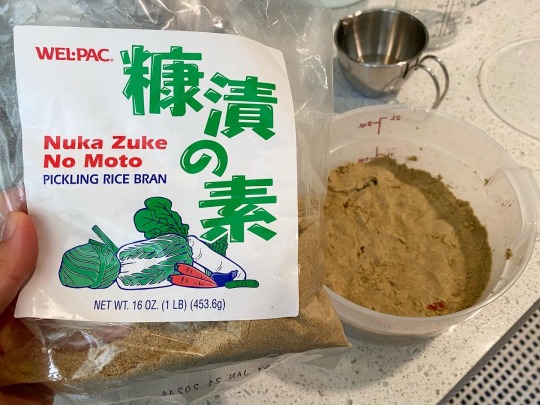

누카즈케

2023/8/10 - 8/19 예전부터 벼르고 벼르다, 재료까지 구해놓고도 이런 저런 이유로 실행을 안하고 있다가, 드디어 해봤다, #누카즈케. 과정이 신기해보여 해보고 싶은 이유가 가장 컸고, 맛은 오이지와 비슷하지 않을까 생각했었는데… 실험적으로 해본 오이와 무우. 흐음. 굳이 이런 귀찮은 (매일 뒤집어줘야함) 과정을 거치며 먹고 싶을 정도의 맛은 아니라고 결론내리고 프로젝트 막을 내렸다. 아래는 인터넷에 떠도는 정보들을 모아 따라해본 과정 정리.

〰️〰️〰️〰️〰️

☑️ Everyday: 하루에 한번씩 반죽을 조물락 조물락해주어 바람을 쐬어줌. 처음에는 괜찮는데, 하루하루 지날수록 상당히 귀찮게 느껴짐. 냉장고에 보관하면 몇일에 한번만 해줘도 된다고 한다. 냉장고 공간 부족으로 실온에서 진행…

☑️ Day 1 쌀겨 가루, 다시마 우려낸 물, 소금 조금 , 고추씨 조금 넣고 저런 점토 같은 재질이 되도록 섞어줌. 다시마와 마른 고추, 그리고 채소 자투리도 조금 추가. 이때 넣는 채소 자투리들은 밑간 들이기 위한 용이라고 함

☑️ Day 6(?), 7(?) 자투리 넣었던 채소들 덜어내고, 실제 먹을 채소들 투입. 다시마도 건져냄. 오이와 무우 새로 넣어줌

☑️ Day 10(?) 오이와 무우 꺼내서 물로 헹궈준 뒤 먹을 사이즈로 잘라서 보관.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fermented Pickled Tomatoes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A collage inspired by Jenny Hval’s novel, Paradise Rot.

I started and finished Paradise Rot and honestly, it was a really good book. I LOVE the way the words are described. Reading the book made me feel humid and fermented. Take that as you will.

#clementinescollage

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fermented Strawberries | Healthy Home Economist

How to ferment fresh strawberries into a lightly cultured chunky puree as a natural preservation method and to significantly enhance probiotics and enzymes. Makes a tasty topping for ice cream, pancakes, toast, and waffles. Also delicious to stir into oatmeal, yogurt, or kefir. We are nearing the end of strawberry season here in Central Florida. I’ve been meaning to experiment with fermenting…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

SciTech Chronicles. . . . . . . . .Feb 13th, 2025

#gravitationally-warped#NGC-6505#space-time#Euclid#Mediterranean#KM3Net#ARCA#ORCA#microbiome#fermented#proximal#distal#mutations#epigenetic#DNA#methylation#cytosine#Bioink#SCOBY#nanocellulose#hydrogel

0 notes

Text

My simple go-to, no muss pickle recipe:

Add salt, pepper, chili powder and sugar to simple vinegar.

Shake.

Marinate thinly-sliced vegetable in it.

Eat.

#food#recipes#pickles#homemade#homemade food#pickling#homemade pickles#fermented#dill pickles#spicy#pickled veggies#pickled cucumber#pickled red onions#pickled mushrooms#vegetarian

1 note

·

View note

Text

"enrique, explain what menopause means."

"well. it depends."

0 notes

Text

[ID: Buttermilk being poured from a Moroccan ceramic cup with orange and black geometric designs into a glass. End ID]

لبن نباتي / Lbn nabati (Vegan traditional buttermilk)

Lbn (لْبْنْ or لْبَنْ; also transliterated "lban") is a Moroccan buttermilk drink. It is not to be confused with standard Arabic لَبَن ("laban"), meaning "milk"; with Levantine لَبَن ("laban"), also called لَبَن رَائِب ("laban ra'ib"), which is curdled milk (a.k.a., yoghurt); or with Levantine لَبْنَة ("labna"), which is yoghurt that has been strained and thickened.

Instead, lbn is a traditional buttermilk. It is historically made the same way Western traditional buttermilk is: by leaving raw milk to sit at room temperature while the cream separates and rises to the top, allowing the cream to ferment, and then churning the cream until it separates further into milk solids (cultured butter) and a cultured liquid byproduct (traditional buttermilk). Commercial Western buttermilk, and some Moroccan lbn, is now no longer traditional buttermilk but instead cultured buttermilk, which is produced by fermenting low-fat milk; this produces a thicker, more acidic liquid than traditional buttermilk. Lbn is usually made with goat's milk, though cow's milk is also often used.

Lbn—very sour and tangy, slightly sweet, and about the consistency of milk—is consumed as a refreshing after-dinner drink during the summer. It is also used to soak كُسْكُس ("couscous") (made from durum, barley, or corn flour). Couscous with lbn is called سَيْكُوك ("saykouk") in Darija (Moroccan Arabic), or أزَيْكُوك ("azaykouk") in Tamazight.

Saykouk is a cold dish, commonly eaten in the desert and in rural areas during the summertime; but it is also sold from food carts and by vendors on bicycles year-round in cities. On Fridays, Moroccans often eat couscous dishes with lbn on the side, and may make some on-the-fly saykouk by pouring lbn into their bowls to soak the couscous that remains after the vegetables or meat in the dish have been eaten.

This recipe resembles cultured buttermilk, in that it ferments non-dairy milk with live cultures to achieve a sour taste. However, it more resembles traditional dairy buttermilk in taste and texture. Note that this lbn is intended for drinking and for recipes that call for Moroccan traditional buttermilk, and not for replacing Western cultured buttermilk in pastries or pancakes.

Recipe under the cut!

Patreon | Paypal | Venmo

Ingredients:

2 cups full-fat oat milk

1-3 vegetarian probiotic capsules (containing at least 10 billion cultures total)

A few pinches salt

A few pinches granulated sugar

Make sure your probiotic capsules contain no prebiotics, as they can interfere with the culture. The probiotic may be multi-strain, but should contain some of: Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidus, Lactobacillus acidophilus. The number of capsules you need will depend on how many cultures each capsule is guaranteed to contain.

Instead of probiotic capsules, you can use a specialty starter culture pack intended for use in culturing vegan dairy, many of which are available online. Note that starter cultures may be packaged with small amounts of powdered milk for the bacteria to feed on, and may not be truly vegan.

Other types of non-dairy milk may work. My trial with soy milk did not succeed (it never became notably tangy). Soaked and blended cashews will thicken substantially, so be sure to blend cashews with at least twice their volume in (just-boiled, filtered) water if you want to use cashews as your base. I found that oat milk, as well as being more convenient and cheaper than cashews, more closely mimicked the taste of lbn. I have not tested anything else.

Instructions:

1. Boil several cups of water and use the just-boiled water to rinse your measuring cup, the container you will ferment your lbn in, and a wooden spoon or rubber spatula to stir. Your bowl and stirring implement should be in a non-reactive material such as wood, clay, glass, or silicone.

2. Measure oat milk into a container and open probiotic capsules into it. Stir the powder from the capsules in until well combined.

3. Cover the opening of the container with a cheesecloth or tea towel. Ferment for 24 hours: on the countertop in temperate weather, or in an oven with the light on in cold weather.

Taste the lbn with a clean implement (avoid double-dipping!) to see if it is ready. If it still tastes 'oaty,' continue fermenting for another 1-3 days, tasting every 12 hours, until it is notably tangy.

4. Blend lbn with large pinches of salt and sugar; or put lbn, salt, and sugar in a jar with a lid and shake to combine. Taste and adjust salt and sugar.

5. Store in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to a week. This lbn will continue to culture slowly in the fridge and will eventually (like dairy lbn) become too sour to drink.

Serve chilled.

#I'm really excited about this one guys I have been racking my brain for a way to make vegan lbn forever!!#but that was before I knew about the power of culturing#Moroccan#cultured#fermented#vegan recipes#vegetarian recipes

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am normal and can be trusted with the transgenderification beam

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Apple Cinnamon Overnight Oats

0 notes

Text

Bridget Foliaki-Davis Shares 5 of Her Favourite Probiotic-Rich Foods for Better Gut Health

Bridget Foliaki-Davis, a renowned chef, functional nutritionist, and the visionary behind Bridget’s Healthy Kitchen, shares her favourite probitic-rich foods. Your gut is home to trillions of microorganisms that all work together to achieve overall health and wellbeing. It is responsible for digestion, flushing out toxins, nutrient absorption keeping your immune strong and even your mental…

1 note

·

View note