#fayette pinkney

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

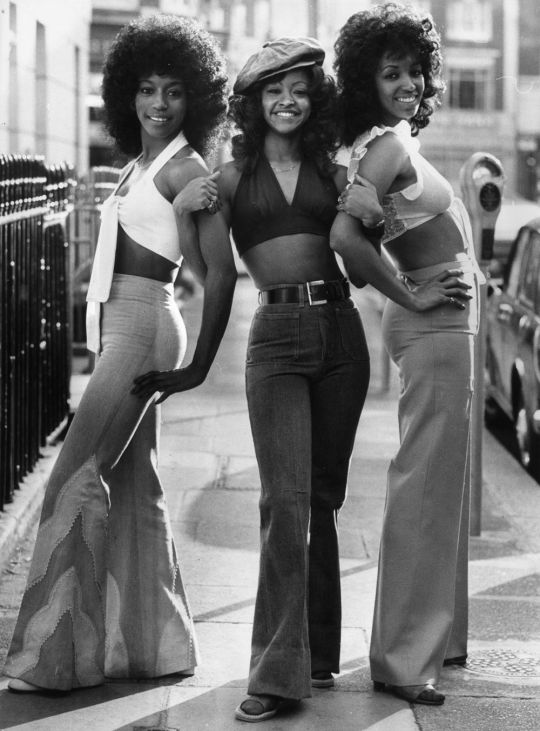

The Three Degrees, singing trio, Sheila Ferguson, Valerie Holiday and Fayette Pinkney, in their belly-baring tops and flares.

#african#africans#African American#three degrees#sheila ferguson#valerie holiday#fayette pinkney#kemetic dreams

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most comprehensive birthday list.

#Rod Stewart#Aynsley Dunbar#Pat Benatar#Donald Fagen#Jim Croce#Fayette Pinkney#Michael Schenker#Nasri

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Three Degrees - When Will I See You Again • TopPop

Happy Birthday Fayette Pinkney

0 notes

Text

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Three Degrees, 1970

#Three Degrees#BLM#1970s#Music#girl group#Old School Cool#Cool Kids of History#Black Lives Matter#the three degrees#History#Music History#70s#70s music#70s fashion#fashion#women of color#valerie holiday#freddi poole#Fayette Pinkney#R&B#Soul#Disco#Feminism#Girl Gang

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

David Bowie and Fayette Pinkney, 70s.

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THREE DEGREES: Fayette Pinkney, Sheila Ferguson and Valerie Holiday

Fun fact: In 1974, MFSB along with the soulful trio The Three Degrees recorded the single “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia),” written and produced by the legendary Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff. This became the theme song for Soul Train from 1974-1975 [X]

#fayette pinkney#sheila ferguson#valerie holiday#the three degrees#three degrees#girl groups#1960s#60s music#1960s fashion#60s#soul music#tsop#mfsb

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Three Degrees, early 1970s | Valerie Holiday, Sheila Ferguson, Fayette Pinkney (L-R)

#Three Degrees#1970s#girl group#singer#chanteuse#Valerie Holiday#Sheila Ferguson#Fayette Pinkney#Philadelphia International Records#tsop#music#R&B#soul#disco#pop#The Three Degrees

14K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Three Degrees — “The Year Of Decision”, 1974

#The Three Degrees#Fayette Pinkney#Valerie Holiday#Sheila Ferguson#Singer#The Year Of Decision#1970s#Music

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frances “Fanny” Burney d’Arblay was such a fascinating person! She came from a large, lively and rather prominent family and was a celebrated author in her time. She was the “Keeper of the Robes” for Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and one of her confidents. Later in life she married the French General Alexandre d’Arblay in 1793. D’Arblay had been an adjutant-general to the Marquis de La Fayette during the French Revolutionary Wars and while in prison, in a letter that was more or less meant as a farewell letter, La Fayette congratulated d’Arblay on his marriage.

La Fayette to his aides-de-camp, January 3, 1794 (English translation):

Farewell, my dear aides-de-camp; my wishes, my tenderness and my gratitude for you will last until my last breath. I renew to d’Arblay and Boinville my tender congratulations on their marriage, and I address a line to M. Pinkney who will deliver this letter to you.

In 1810, Fanny had to undergo a mastectomy and was treated by the most leading physicians of her time – among them Doctor Larrey and Doctor Dubois (obstetrician to the Empress Marie Louise).

English woman witnesses the First Consul at a review

Bonaparte, mounting a beautiful and spirited white horse, closely encircled by his glittering aides-de-camp, and accompanied by his generals, rode round the ranks, holding his bridle indifferently in either hand and seeming utterly careless of the prancing, rearing, or other freaks of his horse, insomuch as to strike some who were near me with a notion of his being a bad horseman. I am the last to be a judge upon this subject; but as a remarker, he only appeared to me a man who knew so well he could manage the animal when he pleased, that he did not deem it worth his while to keep constantly in order what he knew, if urged or provoked, he could subdue in a moment.

Precisely opposite to the window at which I was placed, the Chief Consul stationed himself after making his round; and thence he presented some swords of honour, spreading out one arm with an air and mien which changed his look from that of scholastic severity to one that was highly military and commanding.

Just as the consular band, with their brazen drums as well as trumpets marched facing the First Consul, the sun broke suddenly out from the clouds which had obscured it all the morning; and the effect was so abrupt and so dazzling that I could not help observing it to my friend, the wife of m'ami, who, eyeing me with great surprise, not unmixed with the compassion of contempt, said— ‘Est-ce que vous ne savez pas cela, Madame? Dès que le Premier Consult vient à la parade, le soleil vient aussi! Il a beau pleuvoir tout le matin; c'est égal, il n'a qu'à paroitre, et tout de suite il fait beau.’

[You don’t know, Madame? As soon as the First Consul comes to the parade, the sun comes too! It may be raining all morning; it doesn’t matter, he has only to appear, and immediately the weather is fine.]

Madame d’Arblay [writer Fanny Burney] quoted in Masquerier and His Circle by Robert René Meyer Sée, 1922. Link

#reblog#microcosme11#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#british history#history#1793#1794#1810#larrey#dubois#pinkney#empress marie louise#fanny burney#madame d'arblay#letter#queen charlotte#george iii#lafayette in prison

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Félix Frestel - Georges' "second father"

By now it is well know how close the Marquis de La Fayette and George Washington were. La Fayette described himself as Washington’s adopted son and Washington made no attempt to correct him in any way. What many people do not know however, is that La Fayette’s son, Georges, also had a “second father” - his words, not mine. The man in question was Georges tutor, guardian and lifelong family friend Félix Frestel.

Félix Frestel

Félix Frestel was chosen as a tutor for six-year old Georges by his parents. Georges’ sister Virginie recollects in her memoirs that:

She [Adrienne] was charged at the same time with the accomplishment of my father’s intentions and was anxious to be worthy of the trust reposed in her. For herself also, she wished to find in a tutor the qualities my father desired. It was in the sight of God and guided by the principles of an enlightened piety that, although placing above all things the preservation of faith, she would have thought herself guilty had she neglected in her son's education anything which it is good and useful to acquire. She believed that learning, combined with rectitude of heart leads us to the knowledge of God. She and my father selected M. Frestel as George’s tutor. My mother then made a painful sacrifice. She thought that my father’s constant occupations and that his high position might be prejudicial to her son’s education if he remained at home, by unavoidably diverting him from his studies and causing feelings of pride and vanity to arise in his heart. She hired therefore for M. Frestel and his pupil, then six years old, a small lodging, rue Saint Jacques, where she frequently visited them.

Although I could not find Frestel’s exact date of birth, he was constantly described as a (very) young man and I would therefor estimate that he probably was in his early to mid-twenties when he first became Georges’ tutor. Things seemed ordinary enough at first. Georges progressed well and the pair got along. Things changed as the French Revolution grew more intense. When the arrest warrants for the La Fayette’s were issued, Frestel took Georges, then thirteen, to a little secluded cabin in the mountains where they would be fairly safe from prosecution. Virginie tells us:

A priest assermenté came to offer her [Adrienne] a place of refuge amidst the mountains. M. Frestel took my brother there during the night.

It should be said at this point that Frestel was not of noble birth. If he would have simply severed his ties with the La Fayette’s at this point in time, he probably would not have had much to fear - but he did not. He stayed with the family, primarily taking care of Georges but also going back and forth to confer with Adrienne. In Virginies memoirs we read:

M. Frestel, having left his place of retreat, came in the middle of the night to confer with my mother. In her grief at being so far distant from my father, she wished to send him his son, and thought that, once out of France, George might succeed in joining him, or at least in being of use to him. It was therefore decided that George should depart with M. Frestel, who was to procure a tradesman’s licence and then a passport to go to the fair of Bordeaux. From thence the two travellers were to endeavour to get over to England, there to confer with M. Pinkney, the American minister in order to settle with him what was to be done for my father. My mother denied herself the comfort of seeing my brother before his departure. She feared her courage would fail her at the moment of parting. (…) My mother ardently wished that her son should leave France before her. A letter from Bordeaux, written by M. Frestel had led her to believe that my brother had embarked. Unfortunately M. Frestel having met with too many obstacles, had returned with George to his own relations in Normandy, but was still determined to take the first favourable moment for accomplishing my mother’s wishes.

But although Frestel tried his absolute best, he was not able to get Georges out of the country.

Meanwhile, M. Frestel, seeing the impossibility of leaving France, decided on bringing my brother back to Chavaniac. My mother received him with mingled feelings of pain and joy, which caused her much agitation. M. Frestel pointed out the insurmountable obstacles which had prevented him from carrying out her plans, assuring her that he was ready to recommence his attempts, provided she would furnish him with the means of doing so. Not having courage to decide on another separation, she allowed my brother to join the family.

The family’s situation only became more dire after this. Adrienne was finally taken into custody and Frestel risked his own life trying to reunite the mother with her children:

In the course of January (1794), we found out that it was not impossible to bribe the jailor and to gain admission into the prison [where Adrienne was held captive]. M. Frestel undertook the negotiation which was not without danger. He succeeded. It was settled that he would take one of us every fortnight to Brioude. My sister was the first to go. She started on horseback in the night, remained the whole of the following day with the good aubergiste, already mentioned as devoted to us, and spent the night with my mother. But when daylight came, they were obliged to tear themselves from each other. My sister brought back joy in the midst of us with the details of this happy meeting.

Adrienne was later transferred to a different prison in Paris and when later her sister, mother and grand-mother were executed by the guillotine, it was unclear if she would be next. Virginie’s books details Frestel’s services to the family around this time. He contacted different French and American dignitaries to help Adrienne, he oversaw the selling of some of the families property, he collected money by selling, in accordance with Adrienne, some of the families jewels but also by asking the people in the village if they would be willing to help - witch they were. He kept track of all the different prisons Adrienne was brought to and took care of the children.

I give this short summary without any quotes because it is easier for you all to read the chapter in Virginie’s book in full than for me to quote everything. Most importantly however, Frestel, with some help from the outside, finally managed to get Georges to America:

M. de Segur introduced her [Adrienne] to M. Boissy d'Anglas, a very influential member of the new Committee of Public Safety, whose object was to do as much good as lay in his power. He obtained a passport for my brother under the name of Motier, and made his colleagues sign it without their knowing whom it was for. M. Frestel was equally provided with one, but, in order to avoid suspicion, it was decided that they should not travel together, that M. Russell, citizen of Boston, should take George to Le Havre, and embark him on a small vessel on board of which even his name should be kept secret. My mother decided that before naming himself he was to await M. Frestel's arrival, under the care of M. Russel's father. She did not wish him to be known in the United States till he had a guide to direct him.

While browsing the FoundersOnline archive, you will frequently see Félix Frestel referred to as La Fayette’s former secretary who was captured with him, escaped and then served as a tutor to Georges. While I trust the editors of FoundersOnline more than myself, I am confused as to when Frestel was supposed to have worked as La Fayette’s secretary and have been imprisoned. I might even propose that the editors may have confused Félix Frestel with Felix Pontonnier. Pontonnier was La Fayette’s secretary and had just turned sixteen when he was captured with his employer. After a short time in captivity he managed to escape - I have trouble to believe that La Fayette had to secretaries named Felix at the same time that both were captured and escaped in the same manner.

Anyway, Frestel and Georges arrived in Boston in August 1795. They moved to New York in October and lived with the Russell’s as well as with the Hamilton’s among others. Georges had to move around a lot in the coming months and he scarcely received any news how his family was fairing in Europe. Frestel was his only real constant at the time. He not only served as a companion and even a “second father” but also continued Georges’ education.

It was proposed by George Washington that Georges should attend Harvard University and that Frestel should continue to accompany him there. Washington was willing to pay for all the expenses that might arise. He wrote to George Cabot on September 7, 1795:

3. considering how important it is to avoid idleness & dissipation; to improve his mind; and to give him all the advantages which education can bestow; my opinion, and my advice to him is, (if he is qualified for admission) that he should enter as a student at the University in Cambridge altho’ it shd be for a short time only. The expence of which, as also of every other mean for his support, I will pay; and now do authorise you, my dear Sir, to draw upon me accordingly; and if it is in any degree necessary, or desired that Mr Frestel his Tutor should accompany him to the University, in that character; any arrangements which you shall make for the purpose—and any expence thereby incurred for the same, shall be born by me in like manner.

“From George Washington to George Cabot, 7 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 642–643.] (05/17/2022)

In the end, the decision was made for Georges to continue his education privately with Frestel. He and Georges finally were allowed to stay with George Washington and his family in February 1796. Washington wrote to Alexander Hamilton at the time (February 3, 1796) that:

My mind being continually uneasy on Acct. of Young Fayette, I cannot but wish (if this letter should reach you in time, and no reasons stronger than what have occurred against it) that you would request him, and his Tuter, to come on to this place on a visit; without avowing, or making a mystery of the object—Leaving the rest to some after decision.

“To Alexander Hamilton from George Washington, 13 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 20, January 1796 – March 1797, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974, p. 55.] (05/17/2022)

Georges arrival in America was big news and his presence induced a great deal of back and forth from the leading people of the time. Many of these letters survived and some of them also help to determine Félix Frestel’s character more closely.

Henry Know wrote to George Washington on September 2, 1795:

The son of Monsieur La Fayette is here—accompanied by an amiable french man as a Tutor—Young Fayette goes by the name of Motier, concealing his real name, lest some injury should arise, to his Mother, or to a young Mr Russel of this Town now in France, who assisted in his escape—Your namesake is a lovely young man, of excellent morals and conduct. If you write to him please to direct under cover to Joseph Russel Esqr. Treasurer of the Town of Boston—They will write by this post to you.

“To George Washington from Henry Knox, 2 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 621–624.] (05/17/2022)

Alexander Hamilton wrote to George Washington on October 16, 1795:

Mr. Fristel [sic], who appears a very sedate discreet man, informs me that they left France with permission, though not in their real characters, but in fact with the privity of some members of the Committee of safety who were disposed to shut their eyes and facilitate their departure.

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 16 October 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 19, July 1795 – December 1795, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973, pp. 324–328.] (05/17/2022)

George Washington wrote on December 4, 1797 to Félix Frestel:

For the flattering terms in which you have expressed your sense of the civilities, which your merits alone, independent of the consideration of being the Mentor & companion of our young friend, richly entitled you to, I offer you my thanks—and for the sentiments of friendship with which you are pleased to honor me, I shall always entertain a lively & grateful remembrance. You carried with you the regrets of the whole family, at parting; and I can assure you, Sir, that if you should visit America again, we shall feel very happy in seeing you under this roof, and in your old walks.

“From George Washington to Felix Frestel, 4 December 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 499.] (05/17/2022)

But luckily for us, not only letters about Frestel survived but also letters by him - something that I found especially delightful since we all know how much I like historical handwritings. Some of Frestel’s original letters to Eleanor Parke Custis are today held by the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon. Have in mind when searching the archive that for most letters only summaries are available and that some of the letters appear to be misdated to 1824. The Library of Congress however gives us access to some handwritten originals. Because Frestel co-authored many of his letters with Georges, you sometimes have to take a second look if a letter was handwritten by Frestel or by Georges. Here is an example of one of Frestel’s letters:

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Felix Frestel to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (05/17/2022)

New-york October the 22d 1797.

Sir

I have never been in my life more deeply convinced than in this particular occasion, that I ought to renounce for ever to express to you in a language which I am so little master of, any of the thoughts of my mind, any of the feelings of my heart. I have failed so often in the attempt, that I cannot hope to be now more successful. however I am confident that, although the expressions of my sentiments of gratitude may be ever so inadequate and imperfect, you will nevertheless always do justice to them.

I hope to be more easily understood, when in the idiom of my own country, and in the bosom of that deserving, though unfortunate family, ever so dear to your heart, I shall relate to the parents of my friend, what I have Known and seen better than any man whatever: I mean that constant and unabated interest with which you sympathised in all their misfortunes—that eager sollicitude and anxiety with which you took every measure in your power to lessen the weight of their chains and to break them at last—that Kind, tender and truly paternal affection, with which you received and treated him during all the time he stayed in America—and even that attentive politeness which you extended to me, although I was quite unknown to you before and availed myself, when I came in this country, of no recommendation, but that attachment and friendship for George, which brought me with him in America, and which now carries me back with him to our native country. thus, I hope, the proper expressions shall never fail me.

for my part, sir, I shall remember as long as I live the happy moments I have passed under your hospitable roof, and the examples of virtue which I have seen there daily practiced. they have impressed my mind with a deep sense of respect for its inhabitants and with this very pleasing idea, which I will never forget—“that all who are truly great, are consequently and necessarily good.”

to have been, Sir, and to be always honored with your esteem, shall be for ever the pride of my life, my best compensation for any sacrifices or sufferings whatever, and one of the most delightful recollections of my memory.

with a heartfelt gratitude, though but imperfectly expressed, and with very sincere and fervent wishes for your happiness and felicity, so intimately connected with the felicity and happiness of your own country, I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient humble Servant

Felix Frestel

“To George Washington from Felix Frestel, 22 October 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 419–420.] (05/17/2022)

Here is an overview of all of Frestel’s handwritten letters from the Library of Congress.

After their stay in America, Georges and Frestel returned to Europe. While Georges went to live with the rest of his family in exile, Frestel apparently returned to his family in the Normandy. He later married Marie Cécile Girard - I again have no exact date but I would estimate that the marriage took place sometimes between 1800 and 1805. The couple had at least two sons and I could not find proof of any more (surviving) children.

Georges Léon Frestel

Léon Frestel (as he was most commonly referred to) was the couples oldest son, born in September of 1806. I have no definitive proof but I strongly assume that his first name, Georges, is a homage to Georges Washington de La Fayette, his father’s charge. Léon had to face several severe misfortunes in life and died young. These misfortunes and the course of his life though, are a clear indicator of how close the La Fayette’s and the Frestel’s were. Jules Germain Cloquet, La Fayette’s personal physician and friend wrote in his recollection of the Marquis:

In the year 1828, about the middle of Autumn, M. George Lafayette came post to Paris to take me to Lagrange where my professional assistance was required for the eldest son of his old preceptor, M. Frestel, who had met with a severe accident on a shooting party. We reached Lagrange at eleven o’clock at night, and found the General with his family and friends, assembled in the drawing-room, where they anxiously awaited our arrival, and my opinion on the state of the wounded man. Young Léon Frestel’s gun had burst; and his right hand, which had been laid open to the wrist, was horribly shattered: I was obliged to amputate the last three fingers. His father, who was endowed with uncommon strength of mind, did violence to his feelings, and refused to quit his son during the operation, which the patient supported with the utmost courage and resignation. As soon as I returned to the drawing-room, the interest displayed by Lafayette, his children, and his friends, in behalf of the poor young man, was intense; and I really am unable to describe their eagerness to know my undisguised opinion of his situation, or the emotion, the relief, and the happiness felt by them on learning my hopes, ‑ a happiness alloyed by the pain of knowing that the sufferer was mutilated. Such scenes are too exciting; the feelings inspired by them, and the emotions and expressions which characterize them, are too multiplied and too various to admit of an attempt on my part to pourtray them. They must be witnessed, for they belong to those circumstances of human existence which leave a deep impression on the soul, and are always more easily conceived than described. Dr. Sautereau continued to attend the wounded man, who soon recovered, and who afterwards himself constructed an extremely simple machine as a substitute for the fingers which he had lost. A few weeks before the breaking out of the cholera morbus, M. Léon Frestel, who had commenced his career under the happiest auspices, fell a victim to a severe inflammation of the chest.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 231-232.

Léon died on May 1, 1832 after labouring seven days under an inflammation of the chest. Georges Washington de La Fayette wrote in a letter, dated April 12, 1832 to a family friend:

[André Gaston] Frestel, who had known Mr. de Peron [La Fayette’s grandson] for a long time, had accepted this proposal, all the more willingly because in his colonel's friendship for him he would find some alleviation of the keen pain he was experiencing at the death of his older brother [Georges Léon Frestel], taken at the age of 26 after seven days of chest inflammation from which he was believed almost cured, when we lost him.

Léons Acte de Décès is in the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) of the city of Paris:

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 1239, p. 12-13. (05/17/2022)

As far as I know, Léon was unmarried and without any children when he died.

André Gaston Frestel

Gaston Fréstel (as he was commonly referred to) was born on March 14, 1808 and had a much happier life than his older brother. He served in the military and his carrer was described by Georges Washington de La Fayette in a letter to Monsieur Guittére dated April 12, 1832:

[André] Gaston Frestel, an excellent citizen, rushed to my father’s side at the town hall at the time of the business in July and was my fellow staff-officer until my father left the command of the national guard, on December 26, 1830. since then he joined an artillery regiment, where he received the guard equivalent to the rank of corporal, until Mr. de Peron my nephew, being appointed colonel of the 27th, suggested that he come with him to his regiment. Frestel, who had known Mr. de Peron for a long time, had accepted this proposal, all the more willingly (…)

In the same letter Georges describes his relation with Gaston as follows:

(…) a young friend of mine, whom I love as I would love a younger brother.

Gaston Fréstel eventually married Eugénie Alexandre on May 27, 1843 in Paris. Their Acte de Mariage is held by the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) of the city of Paris:

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 2137, p. 38-40. (05/17/2022)

If you read carefully, you can see two things. Firstly, Eugénie was born in England, in Dover. Secondly, the two of them were a bit naughty by 19th century standards. By the time they married, they were already the parents of a son, Paul Frestel, born on October 22, 1842.

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 532, p. 46-48. (05/17/2022)

Paul’s Acte de Naissance also has an interesting little note on the backside. He was married to Emmeline Alice Léontine Huré on March 21, 1902.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#french revolution#history#handwriting#félix frestel#georges léon frestel#andré gaston frestel#french#paul frestel#georges washington de lafayette#virginie de lafayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1902#1842#1843#eugénie alexandre#1832#research#jules germain cloquet#henry know#alexander hamilton

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

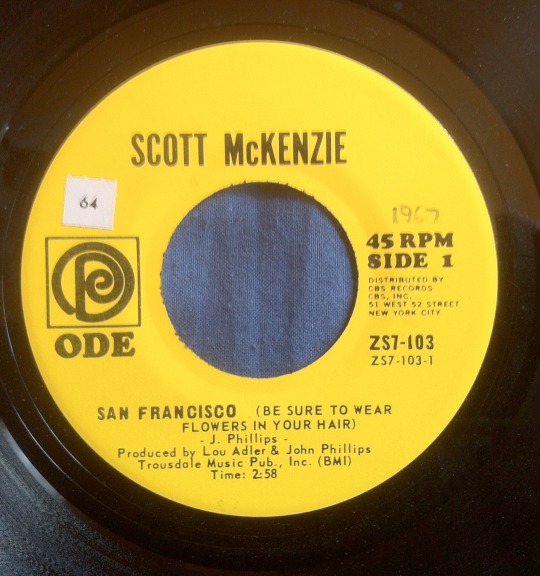

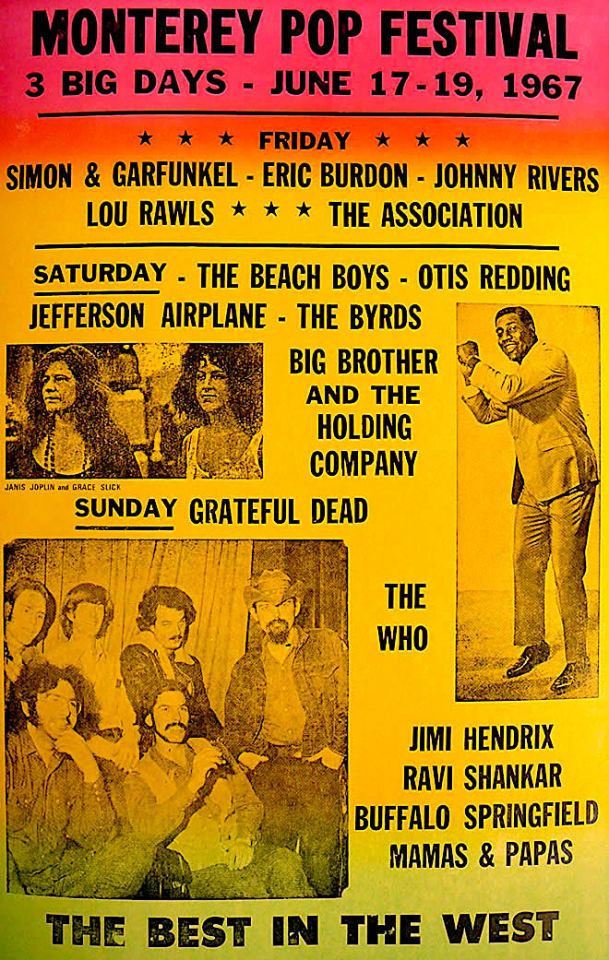

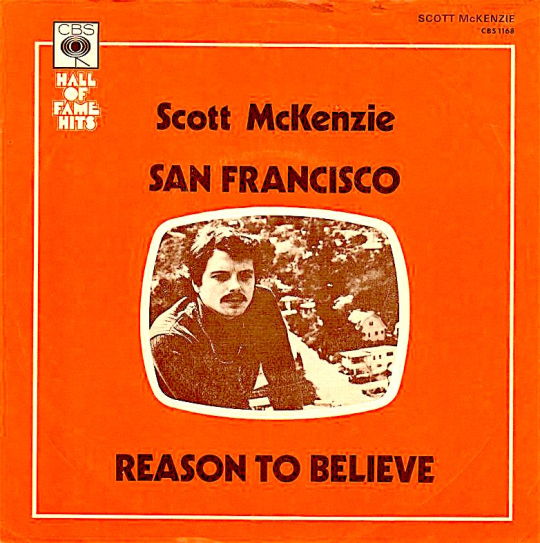

HAPPY BIRTHDAY to the 1964 Vee-Jay LP INTRODUCING THE BEATLES, Pat Benatar, Ray Bolger, Frances X. Bushman, Eddy Clearwater, Jemaine Clement, Shawn Colvin, the 1972 UK LP issue of CONCERT FOR BANGLADESH, Jim Croce, drum heroes Aynsley Dunbar and Max Roach, Donald Fagen, the 1947 Broadway launch of FINIAN’S RAINBOW, George Foreman, the 1928 Gershwin-Romberg-Wodehouse musical ROSALIE, Byron “Whild Child” Gipson, Teresa Graves, Bob Lang (The Mindbenders), Don Letts (Big Audio Dynamite), Ronnie Hawkins, Paul Henreid, sculptress Barbara Hepworth, Frank James, Brian Joo, Mary Ingalls, Jerry Lee Lewis’s 1958 UK single “Great Balls of Fire,” Linda Lovelace, Mendelssohn’s 1833 cantata "Die erste Walpurgisnacht," Sal Mineo, St. Philomena, Fayette Pinkney (Three Degrees), Johnnie Ray, Lyle Ritz (Wrecking Crew), Brad Roberts (Crash Test Dummies), Hrithik Roshan, Samira Said, William Sanderson, Michael Schenker, “Silly Symphony” comics, Frank Sinatra Jr., Sonic the Hedgehog, Nadja Salerni-Sonnenberg, Rod Stewart, Scott Thurston, composer-violinist Gasparo Visconti, mega-producer Jerry Wexler, and Scott McKenzie, the singer-songwriter best known for his association with John Phillips and the 1967 Summer of Love anthem “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair),” the sonic tract that called 1000s of young people to California.

Phillips (who played on the track with The Wrecking Crew) wrote the song to appease authorities concerned that hippies would overrun the Bay Area for the Monterey Pop Festival. Peace and love prevailed. The song has been used in several films and was a theme for the Prague Spring Czech uprising in 1968. That same year, McKenzie’s next Top 40 hit “Like an Old Time Movie” (also written and played by Phillips) segued with McKenzie writing “What About Me” for Anne Murray (her first hit single).

Like many artists circa 1960, McKenzie morphed out of doo-wop and became a folkie, joining the New York folk scene that beget The Mamas & The Papas. Phillips initially invited McKenzie to join that group but he declined, saying he didn’t want “the pressure.” His solo career phased in and out, then he joined a road version of The Mamas & The Papas in 1986. Concurrently, the Phillips-McKenzie team joined Mike Love and Terry Melcher to create the huge Beach Boys hit “Kokomo.”

The evergreen “San Francisco” remains McKenzie’s best-known work (he passed from Guillain-Barre syndrome in 2010). Periodically I dabbled with the song, dirty demo-ing a grunge-y Iggy Pop-like update in 1990 (oddly prescient to Iggy moving to my old Nob Hill neighborhood years later): https://johnnyjblairsingeratlarge.bandcamp.com/track/san-francisco-be-sure-to-wear-flowers-in-your-hair-demo-remastered-2020

HB and RIP Scott.

#ScottMcKenzie #SanFrancisco #Flowers #Hair #MontereyPopFestival #SummerofLove #JohnPhillips #MamasandthePapas #wreckingcrew #PragueSpring #folkmusic #BeachBoys #Kokomo #MikeLove #TerryMelcher #GuillainBarre #grungemusic #IggyPop #NobHill #demo #johnnyjblair #singeratlarge

#Scott McKenzie#singer songwriter#music#san francisco#flowers#hair#Monterey Pop Festival#Summer of Love#John Phillips#Mamas and the Papas#Wrecking Crew#Prague Spring#folk music#Beach Boys#Kokomo#Mike Love#Terry Melcher#Nob Hill#demo#Johnny j blair

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Three Degrees (Valerie Holiday, Sheila Ferguson and Helen Scott (Fayette Pinkney left in 1976) dance with Prince Charles at a charity event for the Prince's Trust at the King's Country Club in Eastbourne, England in July 1978, but when did they see him again?

2 notes

·

View notes