#félix frestel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Georges – "What If" or an Alternative Life

We all know how the life of Georges de La Fayette, only son of Adrienne and Gilbert turned out. Born into a life of privilege, separated for the first time from his family as a young boy to make sure that his father’s status would not interfere with his studies, he later had to flee with his tutor into the mountains and then to America. In America he was a constant wanderer before returning to France and joining his family in exile in Danish-Holstein. The family was finally able to return to France for good, Georges joined the Army, married, had children, became a politician, returned with his father to America in 1824/25 and finally inherited his title as Marquis de La Fayette – just like his two sons later inherited the title from him.

While his father, his mother and his sisters were all imprisoned at various points in time for various reasons and durations, Georges remained free and was able to live, relatively speaking, “comfortably” in America. But let us imagine for a moment how his life could or would have looked like if some things had been different. Because Georges was a family man – even as a grown man he lived with or near his parents (granted, their living arrangements were normally quite spacious, so …), he married the daughter of one of his father’s friends and colleagues, he followed his fathers into the military and in politics, he cared for his mother, he accompanied his father to America – what would happen if his family had died during the French Revolution? Not only his mother and father but maybe even his sisters? Chances were rather high, Adriennes life was threatened by illness and the guillotine (her grandmother, mother and sister were all guillotined) and La Fayette’s life was threatened by illness, the French warrant for his arrest and his status as a Prisoner of War in both Prussia and Austria.

This questions “how would Georges’ life look like” is not completely theoretical. When Adrienne send her son to America, she wrote both to James Monroe and to George Washington and her letters make it clear that she had planned for the eventuality that Georges maybe had to stay for a very long time in America.

Adrienne wrote in an undated letter, probably from November of 1794, to James Monroe:

I ask him kindly to look after my son. I want him to finish his education in an American house of commerce. It would appear to me preferable to set him up at the residence of a consul of the United States. I want him to join their navy, and if it is absolutely impossible for him to begin his first line of duty at sea on an American vessel, I would have him serve on a French merchant ship.

I encourage the minister of the United States to recall that my son was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1785, and that he still has his certificate as a citizen of that state. I foresee therefore no difficulty in his entering the service of this second country, friend and ally of the French Republic.

Papers of James Monroe, 3: 165; Bookmen’s Holiday, x: 20

She wrote secondly in a letter to George Washington on April 23, 1795:

Sir, I send you my son. (…) it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. (…) While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. (…) My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. (…)

Noailles Lafayette

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 317-322.

I shortened the letter in some parts but there is a complete version under the cut for everyone who is interested.

Adrienne gives very detailed instructions, how Georges should be brought up. In short, she wants him to:

Continue his education under Frestel’s tutelage, without too much ado

Start an apprenticeship, I believe, in a house of commerce

Work on an American merchant ship, or, if that is not possible, on a French merchant ship

Be the picture-perfect American citizen without forgetting his identity as a Frenchman

This is all pretty straight forward and we could end our little thought experiment here and take Adrienne’s instructions as the alternative life Georges could have lead. But I would like to elaborate on some aspects.

Félix Frestel

See, on this blog we appreciate Festel and all that he did. Adrienne herself wrote it in the letter to Washington how much the La Fayette’s owned to Frestel. He was Georges tutor long before the Revolution and likely also lived with him during this time. By all accounts he and Georges were close and Georges’ parents also liked and respected Frestel a lot. He risked his personal safety to hide George, helped Adrienne when her fate hung in the balance, he uprooted his entire life and left a family that he “dearly loved” to follow Georges to America – friendship and all things considered, this went clearly beyond the call of duty of a tutor. Adding to that my suspicion that he was not paid during the French Revolution. Both from a logistical and a financial point, paying Frestel would have been difficult and while we have letters from Adrienne to Monroe, asking him to do certain financial transactions for her, there is not letter from her reminding or asking him to pay Frestel. This is certainly no conclusive evidence but I have a very strong hunch.

In America, Frestel was father, friend and teacher for Georges and I am of the firm believe that he would not have easily deserted the boy, even if their stay in America would have been a longer one. I can think of two possible scenarios. One possible scenario would be that Frestel stayed with Georges until he boy would have reached his majority and finished his education in so far as that he was settled with an American merchant firm and learning there. Frestel might have returned then to France – he was free to do so, there was no warrant for his arrest and his name was not on the list of émigrés – and be reunited with his family. Since he was such a loyal soul and very devoted to his pupil, I could imagine him doing what Adrienne in reality did. Going back to France and trying to reclaim the possessions of the La Fayette family for Georges.

In the second scenario, Frestel decides to stay in America, possible because he had started his own family there. When he left France, he was unmarried and childless. It was therefor very possible for him to fall in love in America and decided to stay there with his family. Just as well he could take his wife and potential children with him back to France.

The Merchant Navy

While first reading Adrienne’s letters I found it quite peculiar that she was so insistent on the merchant navy. The merchants trade is one thing, but the service on a merchant ship means a live at sea and some potential dangers that you do not have, if you sit on dry land behind your desk. It could have been Georges expressed desire but since later in France as an adult he choose the Army over the Navy (and there is no indication that he ever considered the navy), I am somewhat doubting that. Life at sea however promised “adevntures”, comradery and occupation – all things that Georges would have needed and liked. Under British law, crew members of merchant ships were often pressed into the military service due to their skills and experiences. American law was different in that regard and Georges would not have worked as a common sailor, so he should have been all good on that front. Being at sea for long stretches of time was also making social engagements difficult. Adrienne had seen what politics can due to peaceful family life and she maybe intended to set Georges up in way where he would not join the politics of his time.

Being an American – Being a Frenchman

Adrienne herself wrote that she hopes her son “preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison”. Later in life, La Fayette wrote in a letter to his son that they should never forget, no matter what had happened or will happen, France is their country and their home. Georges was born and breed in Paris and he was a patriot. In the real turn of events, he would go on risking his life for France. The question therefor is, would he stay in America or return to France? Both are very real possibilities but, in our scenario, I lean more towards staying in America. We assume that his close family is dead (and with that more or less all family members on his father’s side) and many of his Noailles relatives were also dead or had fled the country (his mother’s father for example, he settled in Switzerland). He had extended family that settled into exile in Wittmold but even in reality he only joined them once his sisters and parents were freed and settled there as well. This extended family alone did not seem to be such a huge pull-factor for him. In our scenario he has nothing to return to, no family, no money, no title, no land – even if we assume that Frestel or Georges managed to get some of the family’s possessions back, they would have been empty, void of life and happiness. They would have been shadows, painful reminders of his former life and all that he had lost. Georges was utterly devoted to his family and to his father in particular. I do not think that he could just let go and start over without constantly lingering in the past. But then again, he was French. France was his home and everything that was left from his family was there in France. That again leads us to two possible scenarios.

In the first one, Georges stays in America. If someone was able to get some or all of the family’s former holdings back, he would maybe sell them and use the money to provide for the family he would (absolutely and definitely) start in America. He maybe would even start his own house of commerce. He could also use some of the money to provide for his father’s elderly widowed aunt still living in France. La Fayette had loved her dearly and vice versa. She would have been too old to come to America but Georges could find other means of making sure she was comfortable. He would inherit his father’s titles and probably not use them much, if at all, while in America. Instead referring to his father as “General La Fayette”

In the other scenario, Georges return to France, either with a wife he married while in America or he finds himself a wife in France. Either way, the girl in question would likely been the sister/daughter/niece/etc. of one of his father’s acquaintances. I could imagine that in France, and especially in Paris, even while serving in the merchant navy, there would have been high chances of Georges being caught up in his “old life”. In this scenario, I can very well see Georges enter politics and most importantly bump heads with Napoléon, just as his father would have done. But where Georges had his father’s opinions and views, he did not had his father later “immunity” towards Napoléon’s antipathy.

Anyway, this whole post has turned into a long “what if” rambling but if you made it to this point, I would be really interested to hear your opinions!

Adrienne to George Washington, April 18, 1795

Sir, I send you my son. Although I have not had the consolation of being listened to nor of obtaining from you those good offices which I thought likely to bring about his father’s delivery from the hands of our enemies, because your views were different from mine, nevertheless my reliance on your kindness is not diminished, and it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. Notwithstanding all the perils he encountered on his way, he made known to M. Morris the horrible situation I was in, and, after having had the courage to traverse the whole of France in those times of horror, following a prisoner, who was to all appearances devoted to death, he animated the zeal of the American minister to whose applications I probably owe that my sacrifice was deferred until the revolution of the 10th of Thermidor [July 28]. He will tell you that I have never given a pretext for any accusation against me, that my country can reproach me with nothing, and I myself will tell you that it is near him and with him that my son invariably learnt, even in the depth of misery, to discern between liberty and the horrors to which its name has been associated. While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. I ardently wish M. Washington to know what he is, and how much we are indebted to him. A letter will very in sufficiently fulfil my object. When shall I be able to do so myself? My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. I shall not say anything here of my own position nor of the one which interests me still more than mine. I rely upon the bearer of this letter to interpret the feelings of my heart, too withered to express any others but those of the gratitude I owe to MM. Monroe, Skypwith, and Mountflorence for their kindness and their useful endeavours in my behalf. I beg M. Washington will accept the assurance etc.

Noailles Lafayette

The French original can be found here:

“To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 18 April 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-18-02-0041. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 51–54.]

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#american revolution#american history#history#letter#georges de la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1794#1795#george washington#james monroe#founders online#alternative history#felix frestel

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Young Lafayette and Félix Frestel remained with the Washingtons until October 1797, when word arrived that Lafayette had been freed after five years in prison. The two young men decided to sail back to Europe with all due speed. In a touching farewell, George Washington Lafayette wrote to his godfather how grateful he was for his efforts to rescue his real father and how happy he had been to form a temporary part of his family. Washington fully reciprocated the feeling. When young Lafayette was reunited with his father, he handed him a letter from Washington, who said that young Lafayette was 'highly deserving of such parents as you and your amiable lady.' The boy's family were astonished at how much he had grown, not to mention his striking resemblance to his father. Instead of coming to America, however, the impoverished Lafayette and his nomadic family spent the next two years wandering across northern Europe, living in Hamburg, Holstein, and Holland.

Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow, pg. 739.

#Georges Washington de Lafayette#Félix Frestel#George Washington#Martha Washington#Marquis de Lafayette#Adrienne de Lafayette#Adrienne de Noailles#Washington: A Life#Ron Chernow#pg. 739

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Félix Frestel - Georges' "second father"

By now it is well know how close the Marquis de La Fayette and George Washington were. La Fayette described himself as Washington’s adopted son and Washington made no attempt to correct him in any way. What many people do not know however, is that La Fayette’s son, Georges, also had a “second father” - his words, not mine. The man in question was Georges tutor, guardian and lifelong family friend Félix Frestel.

Félix Frestel

Félix Frestel was chosen as a tutor for six-year old Georges by his parents. Georges’ sister Virginie recollects in her memoirs that:

She [Adrienne] was charged at the same time with the accomplishment of my father’s intentions and was anxious to be worthy of the trust reposed in her. For herself also, she wished to find in a tutor the qualities my father desired. It was in the sight of God and guided by the principles of an enlightened piety that, although placing above all things the preservation of faith, she would have thought herself guilty had she neglected in her son's education anything which it is good and useful to acquire. She believed that learning, combined with rectitude of heart leads us to the knowledge of God. She and my father selected M. Frestel as George’s tutor. My mother then made a painful sacrifice. She thought that my father’s constant occupations and that his high position might be prejudicial to her son’s education if he remained at home, by unavoidably diverting him from his studies and causing feelings of pride and vanity to arise in his heart. She hired therefore for M. Frestel and his pupil, then six years old, a small lodging, rue Saint Jacques, where she frequently visited them.

Although I could not find Frestel’s exact date of birth, he was constantly described as a (very) young man and I would therefor estimate that he probably was in his early to mid-twenties when he first became Georges’ tutor. Things seemed ordinary enough at first. Georges progressed well and the pair got along. Things changed as the French Revolution grew more intense. When the arrest warrants for the La Fayette’s were issued, Frestel took Georges, then thirteen, to a little secluded cabin in the mountains where they would be fairly safe from prosecution. Virginie tells us:

A priest assermenté came to offer her [Adrienne] a place of refuge amidst the mountains. M. Frestel took my brother there during the night.

It should be said at this point that Frestel was not of noble birth. If he would have simply severed his ties with the La Fayette’s at this point in time, he probably would not have had much to fear - but he did not. He stayed with the family, primarily taking care of Georges but also going back and forth to confer with Adrienne. In Virginies memoirs we read:

M. Frestel, having left his place of retreat, came in the middle of the night to confer with my mother. In her grief at being so far distant from my father, she wished to send him his son, and thought that, once out of France, George might succeed in joining him, or at least in being of use to him. It was therefore decided that George should depart with M. Frestel, who was to procure a tradesman’s licence and then a passport to go to the fair of Bordeaux. From thence the two travellers were to endeavour to get over to England, there to confer with M. Pinkney, the American minister in order to settle with him what was to be done for my father. My mother denied herself the comfort of seeing my brother before his departure. She feared her courage would fail her at the moment of parting. (…) My mother ardently wished that her son should leave France before her. A letter from Bordeaux, written by M. Frestel had led her to believe that my brother had embarked. Unfortunately M. Frestel having met with too many obstacles, had returned with George to his own relations in Normandy, but was still determined to take the first favourable moment for accomplishing my mother’s wishes.

But although Frestel tried his absolute best, he was not able to get Georges out of the country.

Meanwhile, M. Frestel, seeing the impossibility of leaving France, decided on bringing my brother back to Chavaniac. My mother received him with mingled feelings of pain and joy, which caused her much agitation. M. Frestel pointed out the insurmountable obstacles which had prevented him from carrying out her plans, assuring her that he was ready to recommence his attempts, provided she would furnish him with the means of doing so. Not having courage to decide on another separation, she allowed my brother to join the family.

The family’s situation only became more dire after this. Adrienne was finally taken into custody and Frestel risked his own life trying to reunite the mother with her children:

In the course of January (1794), we found out that it was not impossible to bribe the jailor and to gain admission into the prison [where Adrienne was held captive]. M. Frestel undertook the negotiation which was not without danger. He succeeded. It was settled that he would take one of us every fortnight to Brioude. My sister was the first to go. She started on horseback in the night, remained the whole of the following day with the good aubergiste, already mentioned as devoted to us, and spent the night with my mother. But when daylight came, they were obliged to tear themselves from each other. My sister brought back joy in the midst of us with the details of this happy meeting.

Adrienne was later transferred to a different prison in Paris and when later her sister, mother and grand-mother were executed by the guillotine, it was unclear if she would be next. Virginie’s books details Frestel’s services to the family around this time. He contacted different French and American dignitaries to help Adrienne, he oversaw the selling of some of the families property, he collected money by selling, in accordance with Adrienne, some of the families jewels but also by asking the people in the village if they would be willing to help - witch they were. He kept track of all the different prisons Adrienne was brought to and took care of the children.

I give this short summary without any quotes because it is easier for you all to read the chapter in Virginie’s book in full than for me to quote everything. Most importantly however, Frestel, with some help from the outside, finally managed to get Georges to America:

M. de Segur introduced her [Adrienne] to M. Boissy d'Anglas, a very influential member of the new Committee of Public Safety, whose object was to do as much good as lay in his power. He obtained a passport for my brother under the name of Motier, and made his colleagues sign it without their knowing whom it was for. M. Frestel was equally provided with one, but, in order to avoid suspicion, it was decided that they should not travel together, that M. Russell, citizen of Boston, should take George to Le Havre, and embark him on a small vessel on board of which even his name should be kept secret. My mother decided that before naming himself he was to await M. Frestel's arrival, under the care of M. Russel's father. She did not wish him to be known in the United States till he had a guide to direct him.

While browsing the FoundersOnline archive, you will frequently see Félix Frestel referred to as La Fayette’s former secretary who was captured with him, escaped and then served as a tutor to Georges. While I trust the editors of FoundersOnline more than myself, I am confused as to when Frestel was supposed to have worked as La Fayette’s secretary and have been imprisoned. I might even propose that the editors may have confused Félix Frestel with Felix Pontonnier. Pontonnier was La Fayette’s secretary and had just turned sixteen when he was captured with his employer. After a short time in captivity he managed to escape - I have trouble to believe that La Fayette had to secretaries named Felix at the same time that both were captured and escaped in the same manner.

Anyway, Frestel and Georges arrived in Boston in August 1795. They moved to New York in October and lived with the Russell’s as well as with the Hamilton’s among others. Georges had to move around a lot in the coming months and he scarcely received any news how his family was fairing in Europe. Frestel was his only real constant at the time. He not only served as a companion and even a “second father” but also continued Georges’ education.

It was proposed by George Washington that Georges should attend Harvard University and that Frestel should continue to accompany him there. Washington was willing to pay for all the expenses that might arise. He wrote to George Cabot on September 7, 1795:

3. considering how important it is to avoid idleness & dissipation; to improve his mind; and to give him all the advantages which education can bestow; my opinion, and my advice to him is, (if he is qualified for admission) that he should enter as a student at the University in Cambridge altho’ it shd be for a short time only. The expence of which, as also of every other mean for his support, I will pay; and now do authorise you, my dear Sir, to draw upon me accordingly; and if it is in any degree necessary, or desired that Mr Frestel his Tutor should accompany him to the University, in that character; any arrangements which you shall make for the purpose—and any expence thereby incurred for the same, shall be born by me in like manner.

“From George Washington to George Cabot, 7 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 642–643.] (05/17/2022)

In the end, the decision was made for Georges to continue his education privately with Frestel. He and Georges finally were allowed to stay with George Washington and his family in February 1796. Washington wrote to Alexander Hamilton at the time (February 3, 1796) that:

My mind being continually uneasy on Acct. of Young Fayette, I cannot but wish (if this letter should reach you in time, and no reasons stronger than what have occurred against it) that you would request him, and his Tuter, to come on to this place on a visit; without avowing, or making a mystery of the object—Leaving the rest to some after decision.

“To Alexander Hamilton from George Washington, 13 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 20, January 1796 – March 1797, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974, p. 55.] (05/17/2022)

Georges arrival in America was big news and his presence induced a great deal of back and forth from the leading people of the time. Many of these letters survived and some of them also help to determine Félix Frestel’s character more closely.

Henry Know wrote to George Washington on September 2, 1795:

The son of Monsieur La Fayette is here—accompanied by an amiable french man as a Tutor—Young Fayette goes by the name of Motier, concealing his real name, lest some injury should arise, to his Mother, or to a young Mr Russel of this Town now in France, who assisted in his escape—Your namesake is a lovely young man, of excellent morals and conduct. If you write to him please to direct under cover to Joseph Russel Esqr. Treasurer of the Town of Boston—They will write by this post to you.

“To George Washington from Henry Knox, 2 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 621–624.] (05/17/2022)

Alexander Hamilton wrote to George Washington on October 16, 1795:

Mr. Fristel [sic], who appears a very sedate discreet man, informs me that they left France with permission, though not in their real characters, but in fact with the privity of some members of the Committee of safety who were disposed to shut their eyes and facilitate their departure.

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 16 October 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 19, July 1795 – December 1795, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973, pp. 324–328.] (05/17/2022)

George Washington wrote on December 4, 1797 to Félix Frestel:

For the flattering terms in which you have expressed your sense of the civilities, which your merits alone, independent of the consideration of being the Mentor & companion of our young friend, richly entitled you to, I offer you my thanks—and for the sentiments of friendship with which you are pleased to honor me, I shall always entertain a lively & grateful remembrance. You carried with you the regrets of the whole family, at parting; and I can assure you, Sir, that if you should visit America again, we shall feel very happy in seeing you under this roof, and in your old walks.

“From George Washington to Felix Frestel, 4 December 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 499.] (05/17/2022)

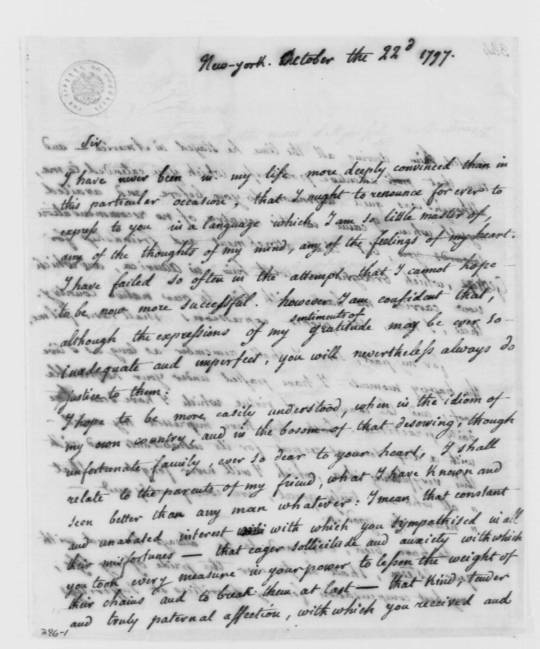

But luckily for us, not only letters about Frestel survived but also letters by him - something that I found especially delightful since we all know how much I like historical handwritings. Some of Frestel’s original letters to Eleanor Parke Custis are today held by the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon. Have in mind when searching the archive that for most letters only summaries are available and that some of the letters appear to be misdated to 1824. The Library of Congress however gives us access to some handwritten originals. Because Frestel co-authored many of his letters with Georges, you sometimes have to take a second look if a letter was handwritten by Frestel or by Georges. Here is an example of one of Frestel’s letters:

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Felix Frestel to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (05/17/2022)

New-york October the 22d 1797.

Sir

I have never been in my life more deeply convinced than in this particular occasion, that I ought to renounce for ever to express to you in a language which I am so little master of, any of the thoughts of my mind, any of the feelings of my heart. I have failed so often in the attempt, that I cannot hope to be now more successful. however I am confident that, although the expressions of my sentiments of gratitude may be ever so inadequate and imperfect, you will nevertheless always do justice to them.

I hope to be more easily understood, when in the idiom of my own country, and in the bosom of that deserving, though unfortunate family, ever so dear to your heart, I shall relate to the parents of my friend, what I have Known and seen better than any man whatever: I mean that constant and unabated interest with which you sympathised in all their misfortunes—that eager sollicitude and anxiety with which you took every measure in your power to lessen the weight of their chains and to break them at last—that Kind, tender and truly paternal affection, with which you received and treated him during all the time he stayed in America—and even that attentive politeness which you extended to me, although I was quite unknown to you before and availed myself, when I came in this country, of no recommendation, but that attachment and friendship for George, which brought me with him in America, and which now carries me back with him to our native country. thus, I hope, the proper expressions shall never fail me.

for my part, sir, I shall remember as long as I live the happy moments I have passed under your hospitable roof, and the examples of virtue which I have seen there daily practiced. they have impressed my mind with a deep sense of respect for its inhabitants and with this very pleasing idea, which I will never forget��“that all who are truly great, are consequently and necessarily good.”

to have been, Sir, and to be always honored with your esteem, shall be for ever the pride of my life, my best compensation for any sacrifices or sufferings whatever, and one of the most delightful recollections of my memory.

with a heartfelt gratitude, though but imperfectly expressed, and with very sincere and fervent wishes for your happiness and felicity, so intimately connected with the felicity and happiness of your own country, I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient humble Servant

Felix Frestel

“To George Washington from Felix Frestel, 22 October 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 419–420.] (05/17/2022)

Here is an overview of all of Frestel’s handwritten letters from the Library of Congress.

After their stay in America, Georges and Frestel returned to Europe. While Georges went to live with the rest of his family in exile, Frestel apparently returned to his family in the Normandy. He later married Marie Cécile Girard - I again have no exact date but I would estimate that the marriage took place sometimes between 1800 and 1805. The couple had at least two sons and I could not find proof of any more (surviving) children.

Georges Léon Frestel

Léon Frestel (as he was most commonly referred to) was the couples oldest son, born in September of 1806. I have no definitive proof but I strongly assume that his first name, Georges, is a homage to Georges Washington de La Fayette, his father’s charge. Léon had to face several severe misfortunes in life and died young. These misfortunes and the course of his life though, are a clear indicator of how close the La Fayette’s and the Frestel’s were. Jules Germain Cloquet, La Fayette’s personal physician and friend wrote in his recollection of the Marquis:

In the year 1828, about the middle of Autumn, M. George Lafayette came post to Paris to take me to Lagrange where my professional assistance was required for the eldest son of his old preceptor, M. Frestel, who had met with a severe accident on a shooting party. We reached Lagrange at eleven o’clock at night, and found the General with his family and friends, assembled in the drawing-room, where they anxiously awaited our arrival, and my opinion on the state of the wounded man. Young Léon Frestel’s gun had burst; and his right hand, which had been laid open to the wrist, was horribly shattered: I was obliged to amputate the last three fingers. His father, who was endowed with uncommon strength of mind, did violence to his feelings, and refused to quit his son during the operation, which the patient supported with the utmost courage and resignation. As soon as I returned to the drawing-room, the interest displayed by Lafayette, his children, and his friends, in behalf of the poor young man, was intense; and I really am unable to describe their eagerness to know my undisguised opinion of his situation, or the emotion, the relief, and the happiness felt by them on learning my hopes, ‑ a happiness alloyed by the pain of knowing that the sufferer was mutilated. Such scenes are too exciting; the feelings inspired by them, and the emotions and expressions which characterize them, are too multiplied and too various to admit of an attempt on my part to pourtray them. They must be witnessed, for they belong to those circumstances of human existence which leave a deep impression on the soul, and are always more easily conceived than described. Dr. Sautereau continued to attend the wounded man, who soon recovered, and who afterwards himself constructed an extremely simple machine as a substitute for the fingers which he had lost. A few weeks before the breaking out of the cholera morbus, M. Léon Frestel, who had commenced his career under the happiest auspices, fell a victim to a severe inflammation of the chest.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 231-232.

Léon died on May 1, 1832 after labouring seven days under an inflammation of the chest. Georges Washington de La Fayette wrote in a letter, dated April 12, 1832 to a family friend:

[André Gaston] Frestel, who had known Mr. de Peron [La Fayette’s grandson] for a long time, had accepted this proposal, all the more willingly because in his colonel's friendship for him he would find some alleviation of the keen pain he was experiencing at the death of his older brother [Georges Léon Frestel], taken at the age of 26 after seven days of chest inflammation from which he was believed almost cured, when we lost him.

Léons Acte de Décès is in the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) of the city of Paris:

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 1239, p. 12-13. (05/17/2022)

As far as I know, Léon was unmarried and without any children when he died.

André Gaston Frestel

Gaston Fréstel (as he was commonly referred to) was born on March 14, 1808 and had a much happier life than his older brother. He served in the military and his carrer was described by Georges Washington de La Fayette in a letter to Monsieur Guittére dated April 12, 1832:

[André] Gaston Frestel, an excellent citizen, rushed to my father’s side at the town hall at the time of the business in July and was my fellow staff-officer until my father left the command of the national guard, on December 26, 1830. since then he joined an artillery regiment, where he received the guard equivalent to the rank of corporal, until Mr. de Peron my nephew, being appointed colonel of the 27th, suggested that he come with him to his regiment. Frestel, who had known Mr. de Peron for a long time, had accepted this proposal, all the more willingly (…)

In the same letter Georges describes his relation with Gaston as follows:

(…) a young friend of mine, whom I love as I would love a younger brother.

Gaston Fréstel eventually married Eugénie Alexandre on May 27, 1843 in Paris. Their Acte de Mariage is held by the État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) of the city of Paris:

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 2137, p. 38-40. (05/17/2022)

If you read carefully, you can see two things. Firstly, Eugénie was born in England, in Dover. Secondly, the two of them were a bit naughty by 19th century standards. By the time they married, they were already the parents of a son, Paul Frestel, born on October 22, 1842.

Paris Archives, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859), Cote 5Mi1 532, p. 46-48. (05/17/2022)

Paul’s Acte de Naissance also has an interesting little note on the backside. He was married to Emmeline Alice Léontine Huré on March 21, 1902.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#french revolution#history#handwriting#félix frestel#georges léon frestel#andré gaston frestel#french#paul frestel#georges washington de lafayette#virginie de lafayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1902#1842#1843#eugénie alexandre#1832#research#jules germain cloquet#henry know#alexander hamilton

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just saw your post about the letters between George(Lafayette) and Jackson so I had to ask this question

Out of all five of the Lafayettes (Gilbert, Adrienne, and their three children) who had the best handwriting in your opinion?

Or maybe any others who were close to them that you think had a good handwriting?

And here we are for round two, my dear Anon!

Félix Frestel was Georges’ tutor and brought him to America during the French Revolution. The Library of Congress has a small number of letters from Frestel, mostly to George Washington.

Félix Frestel to George Washington, October 22, 1797, (English).

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Felix Frestel to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (05/23/2022)

Last but not least, Auguste Levasseur. He was La Fayette’s secretary and we have quite a sizable stack of letters, mostly between him and Georges Washington de La Fayette.

Auguste Levasseur to Georges Washington de La Fayette, January 7, 1826, (French).

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 32], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/23/2022)

After I have let you all suffer through these examples, lets summaries what we have seen. I think my most favourite handwriting is Levasseur’s. Following Levasseur is either Adrienne’s (particularly the one in English) or La Fayette’s handwriting. I can not quite decide between the two of them. An honourable mentions goes to Georges and Edmond. :-)

That was my unnecessary long opinion on historic handwritings, I hoped that was what you were looking for and I hope you have/had a fantastic day!

#ask me anything#anon#letters#handwriting#1826#1797#george washington#georges washington de lafayette#félix frestel#auguste levasseur#history#french history#marquis de lafayette#la fayette

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris, le 12 Avril 1832

This letter was written by Georges Washington de La Fayette to a family friends, Monsieur Guittère. The first part of the letter serves as a note of introduction to Gaston Frestel, the son of Georges former tutor and guardian Félix Frestel. The second part of the letter deals with the ongoing cholera epidemic that had Paris in its grip at that time - and in true La Fayette fashion, Georges uses cholera and the health crisis as a metaphor for the political crisis.

paris, le 12. Avril ‑ 1832 ‑

mon cher monsieur Guittère,

permettez moi de vous présenter un jeune ami à moi, que j’aime comme j’aimerais un jeune frère. C’est le fils d’un homme qui m’a servi de second père, et à la mémoire duquel j’I voué respect, et reconnaisse éternelle. ‑

[André] Gaston Frestel, excellent citoyen, est accouru près de mon père, à l’hôtel de ville, au moment des affaires de juillet et a été mon camarade officier d’état major, jusqu’au moment où mon père a quitté le commandement de la garde nationale, au 26 décembre 1830. ‑ depuis il s’est engagé dans un régiment d’artillerie où il a gagné la garde équivalent à celui de caporal, jusqu’à c que Mr. de Peron mon neveu, étant nommé colonel du 27ème, ait bien voulu penser à lui et lui proposer de venir avec lui dans son régiment. ‑ Frestel, qui depuis longtemps connaît Mr. de Peron, a accepté cette proposition, d’autant plus volontiers que dans l’amitié de son colonel pout lui il trouvera quelque adoucissement à la vive douleur qu’il vivent d’éprouver de la mort de son frère aîné [Georges Léon Frestel], enlevé à l’âge de 26 ans après sept jours de fluxion de poitrine dont on le croyait presque guéri, au moment où nous l’avons perdu. ‑ mon pauvre jeune ami est malheureux, il est assuré de votre intérêt. ‑ je serai reconnaissant du bon accueil que vous voudrez bien lui faire; comme si j’en éprouvais le bons effets moi même. ‑ je regrette bien, mon cher monsieur Guittère, de n’avoir pas profité davantage de votre dernier séjour ici, je suis honteux de n’avoir pas été vous chercher même une seule fois chez vous, mais la vie que je menais alors, et dont celle que je mène aujourd’hui ne diffère que trop peu, pourra m’avoir obtenu votre indulgence. ‑ dans tous les cas, croyez que les anciennes relations avec les homes comme vous, laissent des traces, qui ne peuvent s’effacer.

nous luttons ici contre bien des espèces de choléras. Celui qui s’appelle plus spécialement le choléra morbus nous a fait du mal, mais il paraît arrivé à son degré le plus élevé, et nous espérons qu’il va bientôt décroître. Le choléra politique, et diplomatique semble plus tenace et malheureusement, ceux qui pourraient le plus y porter remède sont précisément ceux qui l’entretiennent. Que faire à cela; n’avoir pas plus peur de ce choléra que de l’autre, et le laisser user comme l’autre; tout ce qui n’est point en sympathie avec l’esprit national doit nécessairement être de courte durée, et certes le ministère actuel serait bien aveugle, s’il se croyait de la popularité. ‑

nous nous portons tous bien en dépit de l’épidémie, ce qui est bien heureux, vu le nombre de personnes qui composent notre famille. ‑ elle est encore augmentée depuis votre départ de Paris. Mathilde a épousé Mr ‑ Bureaux de pusy, fils d’un membre de l’assemblée ‑ constituante, prisonnier d’olmutz avec mon père. ‑

j’espère mon cher monsieur Guittère que ma lettre vous trouvera en bonne santé, et que vous voudrez bien agréer l’expression de mes inaltérables sentiments pour vous. ‑

Georges W. Lafayette. ‑

My translation:

my dear Mr Guittère,

allow me to introduce to you a young friend of mine, whom I love as I would love a younger brother. He is the son of a man who was a second father to me, and whose memory I will respect and recognize until the end of my life.

[André] Gaston Frestel, an excellent citizen, rushed to my father’s side at the town hall at the time of the business in July and was my fellow staff-officer until my father left the command of the national guard, on December 26, 1830. since then he joined an artillery regiment, where he received the guard equivalent to the rank of corporal, until Mr. de Peron my nephew, being appointed colonel of the 27th, suggested that he come with him to his regiment. Frestel, who had known Mr. de Peron for a long time, had accepted this proposal, all the more willingly because in his colonel's friendship for him he would find some alleviation of the keen pain he was experiencing at the death of his older brother [Georges Léon Frestel], taken at the age of 26 after seven days of chest inflammation from which he was believed almost cured, when we lost him. my poor young friend is unhappy, he is assured of your interest. I shall be grateful for the warm welcome you will kindly give him; as if I experienced the good effects myself. I very much regret, my dear Monsieur Guittère, not having taken more advantage of your last stay here, I am ashamed not to have gone to look for you even once at home, but the life I was leading then, and whose that which I lead today differs only too little, your indulgence may have obtained for me. in any case, believe that old relationships with men like you leave traces that cannot be erased.

we are fighting here against many species of cholera. That which is more specifically called cholera morbus has done us harm, but it seems to have reached its highest degree, and we hope that it will soon decrease. The political and diplomatic cholera seems more tenacious and unfortunately, those who could best remedy it are precisely those who maintain it. What to do about it; not to be more afraid of this cholera than of the other, and let it wear out like the other; everything that is not in sympathy with the national spirit must necessarily be of short duration, and certainly the present ministry would be very blind if it believed itself to be popular.

we are all doing well despite the epidemic, which is very fortunate, given the number of people in our family. it has been further increased since your departure from Paris. Mathilde married Mr Bureaux de Pusy, son of a member of the Constituent Assembly, prisoner of Olmutz with my father.

I hope, my dear Monsieur Guittère, that my letter will find you in good health, and that you will kindly accept the expression of my unalterable feelings for you.

Georges W. Lafayette.

Archives départementales de Sein-et-Marne - La Fayette, une figure politique et agricole (05/16/2022).

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#1832#georges washington de lafayette#letter#handwriting#seine-et-marne#monsieur guittère#georges léon frestel#félix frestel#andré gaston frestel#cholera#history

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just saw your post about the letters between George(Lafayette) and Jackson so I had to ask this question

Out of all five of the Lafayettes (Gilbert, Adrienne, and their three children) who had the best handwriting in your opinion?

Or maybe any others who were close to them that you think had a good handwriting?

Yes, finally somebody is asking me something about handwritings. :-) Thank you Anon!

But although I love the question, it is a bit tricky to answer because for some of the family-members the sample sizes are quite small.

Henriette died aged just two so there are naturally no written documents from her.

I know of one handwritten letter by Anastasie but that one was written when she was six years old and therefor also not really suitable to judge her handwriting by.

I also know of one handwritten letter from Virginie when she was an adult.

For Adrienne and Georges we have a number of adult letters (and in George’s case also a few youthful ones) - not too many, but enough for such a comparison.

And, to absolutely no one’s surprise, we have a large number of handwritten letters from La Fayette. I also have a few letters of Edmond de La Fayette - La Fayette’s grandson by his son Georges.

As to people in the vicinity of the La Fayette’s, I would propose Félix Frestel (George’s turor in his youth) and Auguste Levasseur (La Fayette’s secretary around 1824/25). They are amongst the few people where a number of handwritten letters survived.

I am not sure, if I have a clear favourite but we can go over all the different handwritings and I can leave my opinion :-)

First of all, Anastasie:

Anastasie de La Fayette to George Washington, June 18, 1794 (English).

LaFayette: Citizen of two Worlds, From “Rebel” To Hero: The American Revolutionary War, Anastasie de Lafayette. Letter to George Washington. June 18, 1784., 2006, Cornell University. (05/22/2022)

Well, this is obviously the handwriting of a young person but I think the handwriting is nevertheless quite neat, especially considering Anastasie’s age and the fact that English was not her native language. I also have to say that her letter is, from all of the letters in my collection probably the most legible one.

Virginie is next:

Virginie de La Fayette Lasteyrie to Madame Hay, undated (French).

Monroe-Hay Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary. (05/22/2022)

A lovely, solid handwriting. Nothing too fancy in my eyes but very legible and clean.

Adrienne is up next. For her we have both letters in French as well as in English:

Adrienne to George Washington, November 9, 1790 (French).

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Marie A. F. de Noailles de Lafayette to George Washington, November 9, in French. November 9, 1790, Manuscript/Mixed Material, p. 1. (05/22/2022)

Adrienne to Georg Washington, June 18, 1794 (English).

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Marie A. F. de Noailles de Lafayette to George Washington. 1784. Manuscript/Mixed Material, p. 1. (05/22/2022)

I really like Adrienne’s handwriting, both in French and in English. Her French writing is quite small and very neat/controlled while her English writing is a bit more outlandish and larger. I think there is a certain similarity between her and her daughters handwriting.

Georges’ is next. The problem with him is that a considerable number of his letters are in a rather bad condition.

Georges Washington de La Fayette to Captain Allyn, February 17, 1825 (English).

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 31], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/22/2022)

Georges Washington de La Fayette to Monsieur Dutrone, January 6, 1826 (French).

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 33], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/22/2022)

Now, I think I would not call his handwriting “beautiful” but I think is had a certain charm. He definitely evolved from his writing in his boyhood. You often see with his letters that he started out very controlled and then the writing just becomes messier the more he wrote. He was also quite fond of hyphens. I think his handwriting is consistently the most legiable.

We move on to his son Edmond:

Edmond de La Fayette to an unknown person, November 27, 1852 (French).

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 36], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/22/2022)

I can not quite tell what it is, but I really like Edmond’s handwriting. It has something … flourishing. :-)

We close the list of more intimate members of the family with La Fayette himself.

Now, La Fayette’s handwriting is the one I “work” with the most and I have seen it all - the good, the bad and the ugly. His handwriting is normally very legible but I can also always tell when a letter was written in haste, when he had a headache or anything along the line. It should be noticed though that his handwriting was different in English than in French. There are several letter between him and Dr. Benjamin Franklin where Franklin criticizes him for his handwriting. I also noticed that I started to write my L’s like La Fayette did - that should be a warning sign for me. :-)

La Fayette to the Count de Charlus, April 20, 1777 (French)

Raab Collection, April 20, 1777, The Birth of a Legend: 20-year-Old Marquis de Lafayette Leaves France Behind and Sets Sail for America and into History. (05/23/2022)

La Fayette to Captain Francis Allyn, November 9, 1828 (English)

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 21], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/23/2022)

You will see that I chose two letters with the largest possible gap - I wanted to illustrate that La Fayette’s handwriting stayed relatively consistent and did not change too much with age or maturity.

Since Félix Frestel and Auguste Levasseur are still missing and Tumblr only allows me to include a certain number of pictures, I will make a follow-up post where we have a look at some more handwritings and I can tell you whom I probably like best. :-)

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#george washington#georges washington de lafayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#anastasie de lafayette#virginie de lafayette#félix frestel#auguste levasseur#letter#handwriting#1784#1790#1794

16 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In September 1795, at an inopportune moment, Lafayette's adolescent son materialized in America, confronting Washington with an excruciating dilemma. Escorted by his tutor, Félix Frestel, George Washington Lafayette came armed with a letter to his godfather, hoping to involve the president more deeply in efforts to liberate his father. The once-dashing Lafayette père had grown gaunt and deathly pale from years in hellish dungeons, suffering from swollen limbs, oozing sores, and agonizing blisters. He was to remain persona non grata for the five-man Directory that governed France after the end of the Reign of Terror. However strongly he felt, Washington was reluctant to receive young Lafayette for fear of offending the French government, especially after the Jay Treaty furor. Beyond his official duty to safeguard American interests, Washington dreaded that any move might worsen the precarious plight of Lafayette's wife in France, and he was openly stumped about what to do. 'On one side, I may be charged with countenancing those who have been denounced the enemies of France,' Washington confided to Hamilton. 'On the other, with not countenancing the son of a man who is dear to America.'

Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow, pg. 737. Lafayette’s commitment to the French cause, along with the contributions of others in the French aristocracy, cemented the relationship between France and the new United States. However, this same relationship would be the very thing keeping Lafayette from his freedom.

#Marquis de Lafayette#Félix Frestel#George Washington de Lafayette#Adrienne de Lafayette#adrienne de noailles#Alexander Hamilton#Washington: A Life#Ron Chernow#pg. 737

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The People in La Fayette’s employ

Félix Frestel

Sebastien Wagner

Auguste Levasseur

Servants

Aides-de-camp and military secretaries

Miscellaneous

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

okay, quick question: how old was frestel when he came to the u.s. with georges? I stg I was reading stuff about georges' stay there and when i tried to imagine frestel my mind completly stopped workimg cause of this lmao. thankss =)))

Dear @msrandonstuff,

your question comes as quite a peculiar coincident. As it is, I have a lengthy and, I hope, detailed post about Félix Frestel and his family scheduled for this afternoon (afternoon in my time zone.) But to answer your question, I do not know the exact date of Frestel’s birth and therefor can not give you an exact age at which he came to America with Georges. Based on descriptions of him and the age of his children, I would estimate that Frestel was in his late twenties to early thirties when he came to America.

Not the clear answer that I would like to give you, but I nevertheless hopes that gives you a more concrete image of Félix Frestel.

I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#felix frestel#georges washington de lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#american history#french history#french revolution

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

omg I loved the analogy at the beginning, it's perfect.

and the fact that Frestel risked his life to take care of Georges just shows how amazing he was (and how deeply he cared for him)

Georges' "second father"

By now it is well know how close the Marquis de La Fayette and George Washington were. La Fayette described himself as Washington’s adopted son and Washington made no attempt to correct him in any way. What many people do not know however, is that La Fayette’s son, Georges, also had a “second father” - his words, not mine. The man in question was Georges tutor, guardian and lifelong family friend Félix Frestel.

Félix Frestel

Félix Frestel was chosen as a tutor for six-year old Georges by his parents. Georges’ sister Virginie recollects in her memoirs that:

She [Adrienne] was charged at the same time with the accomplishment of my father’s intentions and was anxious to be worthy of the trust reposed in her. For herself also, she wished to find in a tutor the qualities my father desired. It was in the sight of God and guided by the principles of an enlightened piety that, although placing above all things the preservation of faith, she would have thought herself guilty had she neglected in her son's education anything which it is good and useful to acquire. She believed that learning, combined with rectitude of heart leads us to the knowledge of God. She and my father selected M. Frestel as George’s tutor. My mother then made a painful sacrifice. She thought that my father’s constant occupations and that his high position might be prejudicial to her son’s education if he remained at home, by unavoidably diverting him from his studies and causing feelings of pride and vanity to arise in his heart. She hired therefore for M. Frestel and his pupil, then six years old, a small lodging, rue Saint Jacques, where she frequently visited them.

Although I could not find Frestel’s exact date of birth, he was constantly described as a (very) young man and I would therefor estimate that he probably was in his early to mid-twenties when he first became Georges’ tutor. Things seemed ordinary enough at first. Georges progressed well and the pair got along. Things changed as the French Revolution grew more intense. When the arrest warrants for the La Fayette’s were issued, Frestel took Georges, then thirteen, to a little secluded cabin in the mountains where they would be fairly safe from prosecution. Virginie tells us:

A priest assermenté came to offer her [Adrienne] a place of refuge amidst the mountains. M. Frestel took my brother there during the night.

It should be said at this point that Frestel was not of noble birth. If he would have simply severed his ties with the La Fayette’s at this point in time, he probably would not have had much to fear - but he did not. He stayed with the family, primarily taking care of Georges but also going back and forth to confer with Adrienne. In Virginies memoirs we read:

M. Frestel, having left his place of retreat, came in the middle of the night to confer with my mother. In her grief at being so far distant from my father, she wished to send him his son, and thought that, once out of France, George might succeed in joining him, or at least in being of use to him. It was therefore decided that George should depart with M. Frestel, who was to procure a tradesman’s licence and then a passport to go to the fair of Bordeaux. From thence the two travellers were to endeavour to get over to England, there to confer with M. Pinkney, the American minister in order to settle with him what was to be done for my father. My mother denied herself the comfort of seeing my brother before his departure. She feared her courage would fail her at the moment of parting. (…) My mother ardently wished that her son should leave France before her. A letter from Bordeaux, written by M. Frestel had led her to believe that my brother had embarked. Unfortunately M. Frestel having met with too many obstacles, had returned with George to his own relations in Normandy, but was still determined to take the first favourable moment for accomplishing my mother’s wishes.

But although Frestel tried his absolute best, he was not able to get Georges out of the country.

Meanwhile, M. Frestel, seeing the impossibility of leaving France, decided on bringing my brother back to Chavaniac. My mother received him with mingled feelings of pain and joy, which caused her much agitation. M. Frestel pointed out the insurmountable obstacles which had prevented him from carrying out her plans, assuring her that he was ready to recommence his attempts, provided she would furnish him with the means of doing so. Not having courage to decide on another separation, she allowed my brother to join the family.

The family’s situation only became more dire after this. Adrienne was finally taken into custody and Frestel risked his own life trying to reunite the mother with her children:

In the course of January (1794), we found out that it was not impossible to bribe the jailor and to gain admission into the prison [where Adrienne was held captive]. M. Frestel undertook the negotiation which was not without danger. He succeeded. It was settled that he would take one of us every fortnight to Brioude. My sister was the first to go. She started on horseback in the night, remained the whole of the following day with the good aubergiste, already mentioned as devoted to us, and spent the night with my mother. But when daylight came, they were obliged to tear themselves from each other. My sister brought back joy in the midst of us with the details of this happy meeting.

Adrienne was later transferred to a different prison in Paris and when later her sister, mother and grand-mother were executed by the guillotine, it was unclear if she would be next. Virginie’s books details Frestel’s services to the family around this time. He contacted different French and American dignitaries to help Adrienne, he oversaw the selling of some of the families property, he collected money by selling, in accordance with Adrienne, some of the families jewels but also by asking the people in the village if they would be willing to help - witch they were. He kept track of all the different prisons Adrienne was brought to and took care of the children.

I give this short summary without any quotes because it is easier for you all to read the chapter in Virginie’s book in full than for me to quote everything. Most importantly however, Frestel, with some help from the outside, finally managed to get Georges to America:

M. de Segur introduced her [Adrienne] to M. Boissy d'Anglas, a very influential member of the new Committee of Public Safety, whose object was to do as much good as lay in his power. He obtained a passport for my brother under the name of Motier, and made his colleagues sign it without their knowing whom it was for. M. Frestel was equally provided with one, but, in order to avoid suspicion, it was decided that they should not travel together, that M. Russell, citizen of Boston, should take George to Le Havre, and embark him on a small vessel on board of which even his name should be kept secret. My mother decided that before naming himself he was to await M. Frestel's arrival, under the care of M. Russel's father. She did not wish him to be known in the United States till he had a guide to direct him.

While browsing the FoundersOnline archive, you will frequently see Félix Frestel referred to as La Fayette’s former secretary who was captured with him, escaped and then served as a tutor to Georges. While I trust the editors of FoundersOnline more than myself, I am confused as to when Frestel was supposed to have worked as La Fayette’s secretary and have been imprisoned. I might even propose that the editors may have confused Félix Frestel with Felix Pontonnier. Pontonnier was La Fayette’s secretary and had just turned sixteen when he was captured with his employer. After a short time in captivity he managed to escape - I have trouble to believe that La Fayette had to secretaries named Felix at the same time that both were captured and escaped in the same manner.

Anyway, Frestel and Georges arrived in Boston in August 1795. They moved to New York in October and lived with the Russell’s as well as with the Hamilton’s among others. Georges had to move around a lot in the coming months and he scarcely received any news how his family was fairing in Europe. Frestel was his only real constant at the time. He not only served as a companion and even a “second father” but also continued Georges’ education.

It was proposed by George Washington that Georges should attend Harvard University and that Frestel should continue to accompany him there. Washington was willing to pay for all the expenses that might arise. He wrote to George Cabot on September 7, 1795:

3. considering how important it is to avoid idleness & dissipation; to improve his mind; and to give him all the advantages which education can bestow; my opinion, and my advice to him is, (if he is qualified for admission) that he should enter as a student at the University in Cambridge altho’ it shd be for a short time only. The expence of which, as also of every other mean for his support, I will pay; and now do authorise you, my dear Sir, to draw upon me accordingly; and if it is in any degree necessary, or desired that Mr Frestel his Tutor should accompany him to the University, in that character; any arrangements which you shall make for the purpose—and any expence thereby incurred for the same, shall be born by me in like manner.

“From George Washington to George Cabot, 7 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 642–643.] (05/17/2022)

In the end, the decision was made for Georges to continue his education privately with Frestel. He and Georges finally were allowed to stay with George Washington and his family in February 1796. Washington wrote to Alexander Hamilton at the time (February 3, 1796) that:

My mind being continually uneasy on Acct. of Young Fayette, I cannot but wish (if this letter should reach you in time, and no reasons stronger than what have occurred against it) that you would request him, and his Tuter, to come on to this place on a visit; without avowing, or making a mystery of the object—Leaving the rest to some after decision.

“To Alexander Hamilton from George Washington, 13 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 20, January 1796 – March 1797, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974, p. 55.] (05/17/2022)

Georges arrival in America was big news and his presence induced a great deal of back and forth from the leading people of the time. Many of these letters survived and some of them also help to determine Félix Frestel’s character more closely.

Henry Know wrote to George Washington on September 2, 1795:

The son of Monsieur La Fayette is here—accompanied by an amiable french man as a Tutor—Young Fayette goes by the name of Motier, concealing his real name, lest some injury should arise, to his Mother, or to a young Mr Russel of this Town now in France, who assisted in his escape—Your namesake is a lovely young man, of excellent morals and conduct. If you write to him please to direct under cover to Joseph Russel Esqr. Treasurer of the Town of Boston—They will write by this post to you.

“To George Washington from Henry Knox, 2 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 621–624.] (05/17/2022)

Alexander Hamilton wrote to George Washington on October 16, 1795:

Mr. Fristel [sic], who appears a very sedate discreet man, informs me that they left France with permission, though not in their real characters, but in fact with the privity of some members of the Committee of safety who were disposed to shut their eyes and facilitate their departure.

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 16 October 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 19, July 1795 – December 1795, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973, pp. 324–328.] (05/17/2022)

George Washington wrote on December 4, 1797 to Félix Frestel:

For the flattering terms in which you have expressed your sense of the civilities, which your merits alone, independent of the consideration of being the Mentor & companion of our young friend, richly entitled you to, I offer you my thanks—and for the sentiments of friendship with which you are pleased to honor me, I shall always entertain a lively & grateful remembrance. You carried with you the regrets of the whole family, at parting; and I can assure you, Sir, that if you should visit America again, we shall feel very happy in seeing you under this roof, and in your old walks.

“From George Washington to Felix Frestel, 4 December 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 499.] (05/17/2022)

But luckily for us, not only letters about Frestel survived but also letters by him - something that I found especially delightful since we all know how much I like historical handwritings. Some of Frestel’s original letters to Eleanor Parke Custis are today held by the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon. Have in mind when searching the archive that for most letters only summaries are available and that some of the letters appear to be misdated to 1824. The Library of Congress however gives us access to some handwritten originals. Because Frestel co-authored many of his letters with Georges, you sometimes have to take a second look if a letter was handwritten by Frestel or by Georges. Here is an example of one of Frestel’s letters:

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Felix Frestel to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (05/17/2022)

New-york October the 22d 1797.

Sir

I have never been in my life more deeply convinced than in this particular occasion, that I ought to renounce for ever to express to you in a language which I am so little master of, any of the thoughts of my mind, any of the feelings of my heart. I have failed so often in the attempt, that I cannot hope to be now more successful. however I am confident that, although the expressions of my sentiments of gratitude may be ever so inadequate and imperfect, you will nevertheless always do justice to them.

I hope to be more easily understood, when in the idiom of my own country, and in the bosom of that deserving, though unfortunate family, ever so dear to your heart, I shall relate to the parents of my friend, what I have Known and seen better than any man whatever: I mean that constant and unabated interest with which you sympathised in all their misfortunes—that eager sollicitude and anxiety with which you took every measure in your power to lessen the weight of their chains and to break them at last—that Kind, tender and truly paternal affection, with which you received and treated him during all the time he stayed in America—and even that attentive politeness which you extended to me, although I was quite unknown to you before and availed myself, when I came in this country, of no recommendation, but that attachment and friendship for George, which brought me with him in America, and which now carries me back with him to our native country. thus, I hope, the proper expressions shall never fail me.

for my part, sir, I shall remember as long as I live the happy moments I have passed under your hospitable roof, and the examples of virtue which I have seen there daily practiced. they have impressed my mind with a deep sense of respect for its inhabitants and with this very pleasing idea, which I will never forget—“that all who are truly great, are consequently and necessarily good.”

to have been, Sir, and to be always honored with your esteem, shall be for ever the pride of my life, my best compensation for any sacrifices or sufferings whatever, and one of the most delightful recollections of my memory.

with a heartfelt gratitude, though but imperfectly expressed, and with very sincere and fervent wishes for your happiness and felicity, so intimately connected with the felicity and happiness of your own country, I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient humble Servant

Felix Frestel

“To George Washington from Felix Frestel, 22 October 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 419–420.] (05/17/2022)

Here is an overview of all of Frestel’s handwritten letters from the Library of Congress.

After their stay in America, Georges and Frestel returned to Europe. While Georges went to live with the rest of his family in exile, Frestel apparently returned to his family in the Normandy. He later married Marie Cécile Girard - I again have no exact date but I would estimate that the marriage took place sometimes between 1800 and 1805. The couple had at least two sons and I could not find proof of any more (surviving) children.

Georges Léon Frestel

Léon Frestel (as he was most commonly referred to) was the couples oldest son, born in September of 1806. I have no definitive proof but I strongly assume that his first name, Georges, is a homage to Georges Washington de La Fayette, his father’s charge. Léon had to face several severe misfortunes in life and died young. These misfortunes and the course of his life though, are a clear indicator of how close the La Fayette’s and the Frestel’s were. Jules Germain Cloquet, La Fayette’s personal physician and friend wrote in his recollection of the Marquis: