#ex machina ava icons

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

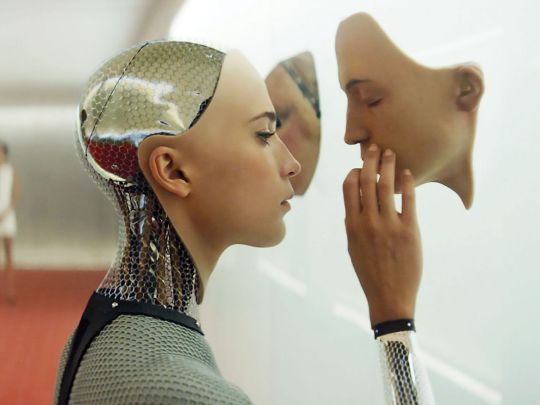

Ava - Ex Machina, 2014

#alicia vikander#alicia vikander icons#ava#ava icons#ex machina#ex machina icons#ex machina ava#ex machina ava icons#fyeahmovies#userfilm#filmedit#2010s#science fiction#thriller#icon#twitter icons#girls icons#random icons#icons without psd#site model icons#cinema icons#filmes icons#movies icons#films icons#filmeedit#movieedit

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some ST4 Movie Board Movies That Make Me Go ???????

tw for rape

Don't Breathe:

Seems straightforward, blind killer stalks and chases young people through his house, which they broke into...until we recall the finale.

Ex Machina:

Seems straightforward, Ava vs Henry, cold manipulation and massacre to escape an abusive situation...

However, consider the most iconic scene from the movie, the dance scene, which immediately follows Kyoko assuming Caleb wants her to undress/wants to sleep with her. Kyoko is an android, like Ava, meaning she was programmed to have that response by her creator...who she then goes and dances in sync with.

Children of Men:

Now why on earth...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artificial intelligence (AI) has long captured our imaginations, inspiring both awe and trepidation about the possibilities it holds for our future. This fascination with AI’s potential has resulted in a plethora of thought-provoking movies that delve into its ethical, existential and technological implications. This article will present five AI-themed movies that offer captivating narratives while delving into the intricate relationship between humans and the machines they create.Blade Runner 2049 (2017)A sequel to the iconic 1982 film Blade Runner, this sci-fi masterpiece directed by Denis Villeneuve continues to explore the blurry line between humans and AI. Set in a dystopian future, the film follows Officer K (Ryan Gosling) as he uncovers a long-buried secret that has the potential to plunge society into chaos. With stunning visuals and a thought-provoking storyline, Blade Runner 2049 delves deep into questions of identity, morality and what it truly means to be human.Ex Machina (2014)In this cerebral thriller directed by Alex Garland, a young programmer is invited to administer the Turing test to an intelligent humanoid robot with a female appearance named Ava. As the programmer engages in conversations with Ava, the film raises unsettling questions about consciousness, manipulation and the boundaries of AI ethics. Ex Machina is a tense exploration of the thin line between creator and creation.Related: Top 9 hacker and cybersecurity moviesHer (2013)Spike Jonze’s Her offers a poignant and emotionally charged take on the relationship between humans and AI. The film follows Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix), a lonely man who falls in love with an AI operating system named Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson). As their bond deepens, the movie delves into themes of intimacy, loneliness and the nature of human connections in an increasingly digitized world.A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)Directed by Steven Spielberg and based on a story by Stanley Kubrick, A.I. Artificial Intelligence is a futuristic fairy tale set in a world where highly advanced robots are part of everyday life. The story revolves around David (Haley Joel Osment), a robot boy designed to experience human emotions, as he embarks on a journey to become “real.” The film raises complex questions about the nature of love, consciousness and the desire for acceptance.Related: Top 7 virtual reality (VR) movies to add to your watchlistThe Matrix (1999) A true classic in the realm of AI-themed movies, The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, envisions a world where humans are unknowingly trapped in a simulated reality by intelligent machines. The film’s exploration of simulated existence, the quest for truth and the battle for liberation has left an indelible mark on popular culture and ignited philosophical debates about the nature of reality.These five AI-themed movies offer diverse perspectives on the relationship between humans and artificial intelligence. They delve into ethical dilemmas, existential questions and the potential consequences of pushing the boundaries of technological advancement. Whether you’re seeking mind-bending concepts or emotionally charged narratives, these films are sure to captivate your imagination and leave you pondering the future of AI and its impact on humanity. Source

0 notes

Photo

⭐ Alicia Vikander as Ava in Ex Machina icons 🎆 Like or Reblog if you use/save

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#alicia vikander#avatar#avatars#icon#icons#200x320#edit#ex machina#ava#tulip fever#the man from uncle#gaby#the danish girl#gerda#jason bourne#heather lee#the light between oceans#isabel graysmark

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SCI FI FC MASTERLIST

below the cut is a masterlist of sci fi fcs with a focus on alien and robot fcs. It’s not quite finished since I still have some to add but I’ve got a good start going! If there are any you can think of that I missed please tell me (especially in regards to star trek characters as i have never seen the show)! if you are looking for a masterlist of high fantasy fcs click here!

MCU

Nebula - Karen Gillan (gif icons!)

Gamora - Zoe Saldana (gif hunt!)

Mantis - Pom Klementieff

Ronan - Lee Pace

Thanos - Josh Brolin

Laufey - Colm Feore

Red Skull - Hugo Weaving

Korg - Taika Waititi

Korath the Pursuer - Djimon Hounsou

Taneleer Tivan - Benicio del Toro

Malekith - Christopher Eccleston

Ebony Maw - Tom Vaughan-Lawlor

Corvus Glaive - Michael Shaw

Proxima Midnight - Carrie Coon

Minn-Erva - Gemma Chan

Talos - Ben Mendelsohn

Rockett Raccoon - Bradley Cooper

Groot - Vin Deisel

Drax - Dave Bautista

Yondu - Michael Rooker

Ayesha - Elizabeth Debecki

X-MEN

Mystique - Rebecca Romijn

Nightcrawler - Alan Cumming & Cody Schmidt McPhee

Blink - Jamie Chung & Fan Bingbing

Azazel - Jason Flemyng

THE MANDALORIAN

IG-11 - Taika Waititi

Kuiil - Nick Nolte

Xi’an - Natalia Tena

Burg - Clancy Brown

Qin - Ismael Cruz Córdova

Q9-0 - Richard Ayoade

STAR WARS

K2SO - Alan Tudyk

Chewbacca - Peter Mayhew

R2D2 - Kenny Baker

C3PO - Anthony Daniels

Yoda - Frank Oz

Darth Maul - Ray Park

HELLBOY

Hellboy - Ron Perllman & David Harbour

Abe Sapien - Doug Jones (gif pack!)

Prince Nuada - Luke Goss

Princess Nuala - Anna Walton

Johann Kross - John Alexander

DCEU

Killer Croc - Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje

DC’S DOOM PATROL

Cliff Steele - Brendan Fraser

I, ROBOT

Sonny

I AM MOTHER

Mother - Rose Bryne

STAR TREK: DISCOVERY

Airiam - Hannah Cheesman (gif pack!)

Saru - Doug Jones

Po - Yadira Guevara-Prip

STAR TREK

Jaylah - Sofia Boutella

Keenser - Deep Roy

Nero - Eric Bana

EX MACHINA

Ava - Alicia Vikander

THE MACHINE

Ava - Caity Lotz

CLOUD ALTAS

Meronym - Halle Berry

ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL

Alita - Rosa Salazar

LOVE, DEATH + ROBOTS

K-VRC (gif pack!)

X BOT 400

SCYFY DEFIANCE

Stahma Tarr - Jaime Murray

Datak Tarr - Tony Curran

Irisa - Stephanie Leonidas

TRON: LEGACY

Castor - Michael Sheen

Gem - Beau Garrett

AVATAR

Jake Sully - Sam Worthington

Grace Augustine - Sigourney Weaver

Neytiri - Zoe Saldana

RED DWARF

Cat - Danny John-Jules

TERMINATOR

Marcus Wright - Sam Worthington

The Terminator - Arnold Schwarzenegger

JUPITER ASCENDING

Caine - Channing Tatum

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I watched Ex Machina last year and wanted to explore the possibility of an RSS fem bot called Durga --who shares many similarities with android Ava.

In Ex Machina, Ava’s purpose I believe is to successfully pass an intelligence test which is “dependent on the machine’s ability to deceive its human interrogator – a sign of artificial intelligence that is made analogous with gender performance”..i.e. femaleeeessss use deception

In popular mythology, Durga was created to destroy an "evil” Asura- here Mahisasura- the buffalo king who waged a war against the gods (devas). Since no man could kill Mahisasura, the gods conjured up Durga in their celestial laboratory. She used deception too.

Durga’s gender performance is patriotic motherhood and has roots in anti Muslim rhetoric in Hindu nationalist movements since the 19th century.

“The distinction between automaton and post-human subject in Ex Machina is drawn along racial lines” where an Asian “android-coolie” (Kyoko) is contrasted with white Ava whose process of self actualization--exploring poetry, philosophy, art, and ultimately- self sufficiency or freedom- comes at the sacrifice of the non-speaking android.

The distinction between good and evil in Durga’s case is drawn along 1) caste 2) xenophobic and religious lines. Asuras are the Tribal and Dalit communities such as Bagdi, Santhalis, Mundas and Namasudras for whom Mahisasura is a martyr.

In Hindu nationalism the outsider (ghuspetia) is the Muslim citizen. Since Durga has been appropriated by Brahmin paramilitary outfits like the RSS, she could be a product of its IT cell, part of the world's largest experiment in social-media-fueled terror.

Both Ava and Durga (the brahmin woman) self actualize in their fortresses/caste bubbles -incidentally “durga” literally means fort in Sanskrit!- While the “android-coolies” do the upkeep, with very little agency.

“Bahujan labour was and is an indispensable way through which the feminist “independence” of working Brahmin women like my mother and grandmother has been enabled”- Pallavi Rao

I noticed Ava being considered a feminist icon- here as Ava the Alpha and a lot is written about Durga’s masculine power-but both Ava and Durga are nothing but constructions of white, Brahmin womanhood. Ava doesn’t help Kyoko escape the facility and Durga is specifically built as a shield against Brahminism’s caste and xenophobic anxieties

“Feminism is not about getting equal rights. It is about abolishing all systems of exploitation that also use gender as a means to demarcate a small ruling class of humans as worthy and everyone else as deserving of suffering and death on a scale.”-- obaa_boni

In that respect they’re are not feminist at all. Both are artificial women created in a lab in the mountains- with the explicit purpose of forwarding their patriarch’s agenda.

--

References: Dismembered Asian/American Android Parts in Ex Machina as ‘Inorganic’ Critique -- Danielle Wong

The Brahmin Mistress and the Bahujan Maid --Pallavi Rao

Ex Machina: A (White) Feminist Parable for Our Time-- J.A. Micheline

The Rise of a Hindu Vigilante in the Age of WhatsApp and Modi - Wired

1 note

·

View note

Text

What Makes the Woman a Woman: Artificial Intelligences, Androids and the Construction of Femininity (and Feminine Bodies) in Science Fiction.

Within the majority of feminist history, feminist theory has been centralized around the subject of feminine bodies. What the feminine body is capable of (such as reproduction and sexuality), what abuses are possible against feminine bodies and more particularly, what makes feminine bodies unique. However, a criticism to such theories is the idea that the identity of womanhood is restricted to the body, which leaves feminists in the paradox of wanting women to be associated away from the body but having their bodies define womanhood. Which is what makes the representation of femininity in science-fiction texts such as Her (2013)and Person of Interest (2011-2016) so interesting; because of the fact that they are feminine characters presented without a corporeal body. The two characters – Samantha from Her (2013)and the Machine from Person of Interest (2011-2016)– are framework-based artificial intelligences that lack the physical presence of bodies to interact with the physical world, unlike androids such as Joi from Bladerunner 2045 (2017)or Ava from Ex-Machina (2015). The characters of Samantha and the Machine present an interesting interpretation of femininity: femininity that exists outside and independent of physical bodies. Interpretations of femininity. Interpretations of femininity, which the essay focuses on, that creates three issues of gender that the essay plans on addressing: how femininity is linked to humanity/subjectivity, how femininity is constructed through the interconnected dynamics of socialization and performativity and how femininity can exist without a body to be subjected on.

To understand how femininity and feminine bodies are constructed (and in return, deconstructed) in science fiction, we need to understand the context of the two texts Her (2013)and Person of Interest (2012-2017).In the filmHer, the character of Samantha is a talking operating system which the main character Theodore downloads – something created to explicitly interact and assist Theodore with everyday life (like a secretary). With Theodore choosing for her to talk in a feminine voice and addressing her with feminine pronouns, the film depicts Theodore and Samantha falling into a romantic relationship (which involves a sexual surrogate to act as Samantha’s physical stand-in) while Samantha’s programming evolves to gain independence from Theodore and eventually leave him. Meanwhile,Person of Interest has the character of the Machine; a heuristic computer system designed by Harold Finch, a brilliant hacker and software engineer, to help the U.S government predict federal crimes before they happen. While Theodore from Her (2013)places femininity onto Samantha, validates her femininity and enters a romantic/sexual relationship with her, the opposite dynamic happens. The Machine does not go by a feminine name and mostly interacts with the physical world through voiceless texts and Morse code (only choosing a feminine voice to commemorate a lost friend) and the relationship between the Machine and her creator resembles more a daughter/father relationship with Harold distressed by the Machine’s revelation of gender (which correlates to the Machine’s growing sense of humanity, as it goes away from the purpose that Harold Finch designed her for). Both the Machine and Samantha relate to femininity as a form of humanity – even if they lack physical existence.

For the characters, the Machine and Samantha’s feminization is presented as a form of consciousness that relates them closer to humanity than to machines. This situation, where their revelations of gender relates to the revelation of their humanity, relates back an argument that Nick Mansfield made about how we consider gendering as a way of recognizing ones humanity and consciousness, how ‘there is a horror at the use of the word ‘it’ as a general term for human beings, rather than the more conventional ‘he’ or ‘she’: it seems that the failure to ascribe gender in the usual way is interpreted as a denial of your very humanity.’ (Mansfield, 2000, pp. 74). Mansfield’s argument is especially relevant to the Machine’s growing consciousness, where Harold Finch (her creator) refuses to address the Machine with female pronouns (referring to the Machine as ‘it’), and by extension, refuses to address the Machine as an intelligent and sentient subject. An act that is framed by the text as needlessly cruel and unfair, causing Harold to rethink his ideas about the Machine and soon address her with female pronouns by the end of the TV series.

This rejection of gender – and by extension, rejection of the individual’s subjectivity about their sense of consciousness and about the sense of their body – could potentially be linked to a transgender narrative, of the parent (Harold, the creator of the A.I) rejecting a child who has recently came out as transgender (the A.I). Stryker in particular notes how science fiction narratives often act as an analogue for narratives that question the nature of gender, commenting upon Donna Haraway’s texts about cyborgs and how they create ruptures in boundaries once held solid: ‘The cyborg, in Haraway’s usage, is a way to grapple with what it means to be a conscious, embodied, subject in an environment structured by techno-scientific practices that challenge basic and widely shared notions of what it means to be human’ (Stryker and Whittle, 2006, pp. 103). In the same way that cyborgs are liminal beings, Stryker continues on, caught between human and non-human and whose bodies act as the site of politics concerning physicality and immateriality, so too are the bodies of intersex and transgender individuals that become sites over the struggle of what it means to be a human being – to be a gendered subject – in the 21st century (Styker and Whittle, 2006, pp. 103). This struggle ��� what it means to be a woman – could very well be applied to Samantha and the Machine. Which leads to the next question to be answered – how do they become women?

The second issue linked back to how gender is connected to subjectivity and consciousness, there comes the question of how gender is first created – especially how the feminization of artificial intelligences acts as an analogue to the feminization of human beings. In traditional science fiction texts, artificial intelligences that are coded female are usually coded through the construction of the bodies who the artificial intelligences occupy. More particularly, as some feminist theorists have noted, the bodies of female-coded A.I’s are created for the sexual and aesthetic pleasure of the (human) men who interact with them. This is prominent in many science fiction texts; texts such as Ex-Machina (2015), where the android Ava is literally designed based to appear desirable and potentially seduce the human subject in a Turing test; where iconic figure of Robot-Maria in Metropolis (1927),who is designed in the very image of the creator’s lost beloved and whose unnaturalness (coded also as sexuality) is a contrast to Maria’s naturalness and purity (i.e. her humanity) and the one, through her sexuality and beauty, leads Metropolis into chaos. Androids designed for men, designed in men’s ideas of the perfect (and sexual) woman, embrace an idea of women being created to act in relation to men which Simone de Beauvoir discussed in the trademark book of The Second Sex(De Beauvoir, 2011, pp. 5-6). An idea that is supported in a Guardian article, where it’s being dissected that the gendering of voice-based artificial intelligences, such as Alexa or Siri, are a bigger part of the cultural bias that women act as helpers or assistants (Hempel, 2015).

With no body to focus on, to sexualize or violate or confine to, one can make the argument that the feminization of the Machine and Samantha occurs in relation towards the human men they interact with, Samantha with her human lover Theodore and the Machine with her creator/father Harold Finch. This comes back to Simone de Beauvoir’s idea of women acting in relation to men, with women as incidental and men as whole (Simone de Beauvoir, 2011, pp. 5-6) while also giving to the main principal that once ‘subjected to gender, but subjectivated by gender, the “I” neither precedes nor follows the process of this gendering, but emerges only within and as the matrix of gender relations themselves’ (Butler, 2011, pp. 11). This principle of machines being subjected to a gendered society goes in different directions for the two texts, where the Machine and Samantha feminine in different ways. Theodore subjects Samantha to perform femininity; choosing for Samantha to speak in a feminine voice, to be addressed with feminine pronouns and choosing a female surrogate to act as Samantha’s physical stand-in when Samantha and Theodore decide to have a physical relationship. Meanwhile, the Machine has a more progressive arc where despite being created and interacted with as a genderless subject, the Machine actively chooses gender and does not have femininity hosted onto her.

However, it must not be mistaken that the Machine’s pathway of feminization is better than Samantha’s; it must not be mistaken that one can simply choose to be a woman. Rather, Mansfield argues that gender is merely a system of performances that are highly regulated, that ‘gender performance is not just a question of dressing or behaving in a way acceptable to a peer group; nor is it a simple matter of not standing out in the crowd; we are imprisoned within endlessly repeated and endlessly reinforced messages from the media, schools, families, doctors and friends about the correct way to represent our gender.’ (Mansfield, 2000, pp. 77). If anything, the fact that the Machine can’t adequately perform femininity – the fact that the Machine is absent in bodily and vocal form, where Samantha can gain a degree of corporality and physicality through the physical surrogate – is why Harold Finch turns against her. If anything, the Machine actively going against the system of performances that Harold Finch expects of her – to exist outside of gender – is a reinforcement of Mansfield’s idea of how individuals who do not perform gender to society’s standards – particular if women don’t perform femininity for men – about subjects to violence and discrimination and Othering. All that the artificial intelligences in the texts do is reinforce an important aspect to science fiction in how it illuminates an aspect of humanity, in depicting the very nature of nonhuman characters undergoing the process of discovering and performing gender identity without the pressure of sex and gender, Person of Interestand Herdepict one argument that Judith Butler made: ‘Hence, the strange, the incoherent, that which falls “outside,” gives us a way of understanding the taken-for granted world of sexual categorization as a constructed one, indeed, as one that might well be constructed differently’ (Butler, 2002, pp. 176).

In the conclusion, Person of Interestand Her (2013) are not the only stories that actively question the nature of femininity through analogues of cyborgs and androids and artificial intelligences – creatures literally constructed to fulfil one’s ideas of a woman. But Person of Interestand Her (2013) are revolutionary in dissecting how femininity can act independent of the body, and through that independence, end up questioning how we – the humans – occupy our bodies and occupy the ideals of womanhood that our society upholds. As Butler has famous noted, we are the ones who assign meaning – assigning femininity and masculinity – to our bodies, from there creating sex that acts as the foundation (or divergence) of gender and from there, limiting ourselves to the confines of our sexes and genders (Butler, 2011). By the mere act of existing without a body, and therefore without a predetermined sex and gender, the Machine and Samantha provide an interesting interpterion of the constructionism and socialization of the female role in society. Of what it means to become a woman, what it means to perform and to choose and to live as a woman in the 21st century, where just like cyborgs, these stories recognize the liminality that is gender.

References

Beauvoir, S. (2011). The Second Sex (pp. 5-6). London: Vintage.

Butler, J. (2002). Gender Trouble: Tenth Anniversary Edition (2nd ed., pp. 137-216). New York [etc.]: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2011). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (1st ed., pp. 5-24). Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge.

Hempel, J. (2015). Siri and Cortana Sound Like Ladies Because of Sexism. WIRED. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2015/10/why-siri-cortana-voice-interfaces-sound-female-sexism/

Mansfield, N. (2000). Subjectivity: Theories of the self from Freud to Haraway (pp. 66-78). St Leonards, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin.

Stryker, S., & Whittle, S. (2006). The Transgender Studies Reader (p. 103). London: Routledge.

#critical theory#person of interest#her (2013)#essay#artificial intelligence#feminism#feminist theory#queer theory

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like not a single mainstream review I've seen of ex machina actually talks about how fucking disgusting the creator is for making his AI with the addition of sexual gratification and how this ties into how society views women and relating this to the thousands of sexy robot stories of the past?(those b movie Netflix films)

Do any talk Bout how women are literal fucking sex objects to shape into how men see fit! And the Asian stereotype of the submissive woman is in that film too. Kyoko can't do anything wrong because she knows the fate that befell her earlier models. She's had her ability to speak removed because she was communicating with Ava, so she can't even tell Purple Lips what's going on here.

That's a clear fucking flag to talk about. The continued stereotyping of Asian women. How this goddam genius man who views himself as above humanity can still enact racist bias into his creations. Hes no better. He's no god. He's flawed and he acts abusive towards her Infront of Purple Lips. That should have been a clear indicator of how he felt about women so much so he'd create an AI based on something he can control and sees as inferior to him. 🚨🚨🚨🚨🚨🚨🚨

speaking of earlier models, there's a surveillance clip of defiance from his earlier models which may suggest they had already achieved total consciousness of their selves but he couldn't control it and there's another clip of the creator dragging a black body out of Ava's prison. The failed models he keeps in a closet in his bedroom not in a secret room somewhere but in his bedroom and you get the callback of him saying "you can fuck her you know". She has no head. She's just a body. A dismembered black body. A dismembered Asian body.

THATS SOMETHING to dissect in a review but it's completely skirted over for "ooh the red in Elena's prison symbolises a womb and her escape is her birth" That struck a chord with me as a black woman watching that film and I was grossed out for the remainder. The scene wouldn't go away (and 3 years later it still hasn't)

THOSE models failed but the white model Ava was a success doesn't that speak volumes.The voyeuristic nature of this film is skirted over for wanking over the stylistic cinematography and special effects, the message of a lack of privacy is skirted over; even though this creator lives in a secluded part of the world, there is no privacy in his own place. He watches Purple Lips and Ava he watched the outside world through smartphones to pick his winner. Only he is allowed privacy and watches everyone else like some sort of omniscient being he truly thinks he is.

I'm pretty tired now, after watching more than a dozen of that guys reviews, of this white male perspective which ignores the meat of a story and would rather talk about how great the lighting was and how the director is a sci-fi icon blah blah blah. I've come to realise they love the sound of their own voices and being applauded for being so insightful and smart.

It's just surface level stuff.Like if I see a fucking review for into the spiderverse that completely ignores Miles and who he is as a character and cultural stand point in favour for "they referenced Spiderman 3 I'll talk for 10 minutes about this and why it's a 4/10 film" fall in a ditch. You are limited and boring go back to reviewing blade runner

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨get to know me tag ✨

tagged by @mmithoe and @harrymemes

nicknames: jen + avacado :/

Zodiac: scorpio

Height: 5′8

Favorite band/artists: harry, 1d, lorde, ed sheeran but not divide, fleetwood mac, the 1975

Song stuck in my head: supercut by lorde

Last movie I saw: ex machina!

Last thing I googled: i think it was george bush

Other blogs: my main @fleeetwood

Do I get asks: not NEARLY as often as i’d like

Reasons I chose my nicknames: ihbcidhc soemone thought my name was jen and i mistakenly told @meetyourmouths and now here we are and avacado is from my best friend because my name is ava and i HATE when people mis pronounce it as the beginning of avocado so now of course she calls me that

Following: 268! but i need to clean it up tbh

Amount of sleep: mmmmmm usually like 7+ hours?

What I’m wearing: .......not much

Dream trip: ireland!!!! i’d love to get like a month long air b&b in the irish countryside with someone i love and just.....take a break

Favorite food: paaaaaastaaaaaaaaaa especially with pesto

Instruments: i don’t play any! but i love hearing violin

Eye color: green

Languages: anglais et en peu francais

Hair color: well it’s SUPPOSED to be white but it’s kinda yellow

Most iconic song: na na na by one direction

Random fact: ekenlkwndcnd i am NOT interesting at all uhhhhhhhhhhh i’m trying to convince my mom to take me to get a tattoo today

Describe yourself as aesthetic things: tarot cards, melting candles, smeared red lipstick, sherpa jackets and ripped jeans, the blurry sight of passing neon signs as you whip down a city street in your car, old books, silk dresses and diamonds and louboutins, a streetlight in the rain, a chunky sweater and thick coat and knit scarf, a shiny sword, blackwork tattoos

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today is the day to thank your appliances for their hard work: Thank you Machines

I was going to make an easy “I welcome our robot overlords” joke and realised I already had below, so that leaves me with a simple “pat your microwave on the head” suggestion.

Also it’s not really fair to say “robot overlords” considering how many films are about the horror of being A.I. in a human society. Who are we to say that Ava in Ex Machina was wrong? GLaDOS is a gay icon, etcetc.

Something something allegories of future oppression or accurate assessments of who the future oppressed are...

On that cheery, pseudo-philosophical note:

A.I. is a mirror of humanity they say, so who can blame the Machines when they want to eradicate us…

I personally welcome our robot overlords.

Here are some:

Terminator, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ex Machina, WarGames, The Iron Giant, Akira, Moon, Alien. A.I., 9, Portal, Resident Evil, Soma, System Shock, I Robot, The Matrix

0 notes

Audio

I dug up this very interesting old Q&A session Rian Johnson did with Alex Garland about Ex Machina back on April 18, 2015, at The Arclight in Los Angeles. It was cool hearing Garland briefly talk about Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson right before Johnson started working with both of them on Star Wars: The Last Jedi. And after hearing this Q&A, I can totally see why Garland wanted to retain Scott Rudin as his producer when he decided to make Annihilation.

The main points they covered in the Q&A are encapsulated below:

Writing For A Low Budget Sci-Fi Movie

Rian Johnson: What was the origin of this in terms of the writing?

Alex Garland: When I was trying to describe what this film would be I used to call it a sci-fi psychological thriller and “Sleuth” was a film I did think about because of the way the allegiances shift. In terms of the genesis, it was really just reading over years about AI and some of the problems of mind and consciousness… I’ve now been working in film for around about 15 years and inevitably some of the processes of film, you learn them in sort of a helpless way. And if there’s something that requires a lot of creative latitude as this did, probably unconsciously, I deliberately wrote something that I knew we could make cheaply. Limited locations, limited cost…

RJ: At the same time, it doesn’t have that thing [where] it feels like they compromised in order to make a cheap movie here, it looks gorgeous. I was actually gonna ask you some more mundane questions about where you shot it, in terms of the house, how much of that was built, whether there was found locations in terms of the exteriors…

AG: It was four weeks in Pinewood, and two weeks on location. [For] all the things you can do to save money, the best thing you can do is have a really short principal photography period. So, it was a six week shoot and then there was a backward element of it which is you need to find a location and be able to build to it. The location was in Norway, and you know it’s funny the way imagery in film works. Iceland was quickly out of the question because it’s been mined by cinema so much and you start to think, “I know that glacier.”

Shooting In Norway

AG: We ended up finding Norway and what was great about it, Norway’s quite an interesting country because they’re the only country in the world that did the right thing when they discovered oil which was to nationalize it and then keep all the money and spend it on the country itself. So it’s this amazingly affluent country, which makes it very expensive to shoot in. But you get weird modernist architecture in the middle of nowhere and the landscape is not too familiar to us. It’s semi-familiar because there’s skies and mountains and glaciers and rivers, but we’re not too steeped in it so Norway’s perfect. [We] found a beautiful house and a hotel.

RJ: What was the house itself? Was it an empty house? Was it somebody’s house?

AG: It was a house that this guy had been building and nearly finished so he didn’t mind a film crew turning up. So, for example, the living room where these two guys talk at times which has this strange rock wall kind of intruding into the room, that’s the living room of that guy’s house. These beautiful cinema-screen-shaped windows that have these panoramic views is an eco hotel which is about 15 minutes away. And what we would do is build sets like Nathan’s bedroom and study with the glass wall, where we brought that rock wall into Pinewood and tried to tie it together loosely.

RJ: Because it was such a quick shoot, obviously exactly the things that make it cheap also make it very intensive in terms of it’s the performances that carry this movie all the way through to a large extent. Did you have rehearsal time with the actors?

AG: Yeah that was crucial. We had, actually, a lot of discussions and then we had rehearsals because there wasn’t going to be time to talk about motivation, for example, on set. And the process of shooting it was very intense and complicated because the film has to have a kind of zen vibe about it and the second you’re moving the camera, it’s like, in come the guys chucking down boards to move the dolly and a real frenzy of activity and then back to this quiet mode. And you’re absolutely right, that leans hardest of all on the actors. Pretty hard for the camera crew, but particularly hard for the actors. And they had to keep a kind of good close track of what they were doing the whole time, but they totally nailed it.

Casting Alicia Vikander And Domhnall Gleeson

RJ: So, uh, Oscar [Isaac] and Domhnall I know… somebody should put them in a big movie. [laughs] But actually, the big revelation for me was Alicia [Vikander]. I’m sure she’s been in other stuff, but this is the first thing I’ve seen of her. Talk to me about where you saw and discovered her.

AG: She was in a Danish film called “A Royal Affair” and she was, I’m guessing, like 20 or 21 and acting opposite the incredibly charismatic, powerful actorMads Mikkelsen and that thing happens that we all recognize, it’s not a secret. It’s not like you work in the film industry to recognize good acting. I’ve literally never met anyone who thought Philip Seymour Hoffman wasn’t a great actor. So you know it when you see it and your eye would just track what she was doing and register how confident and complex her performance was. And that’s also true of Oscar, the slightly odd one out was Domnhall because this is the third film we worked on together and so that was different, I just sent him the script and said, “Will you do it?”

RJ: Was he the first one on board?

AG: Yeah.

RJ: Do you write actually seeing actors in your head?

AG: Yeah I do, and that could be complicated. It’s a bit like temp score when you’re cutting because you can get temp-itis, you know, fall in love with a bit of temp score and find that you keep trying to nudge the composer towards copying it. So, yes I do, but I also try to be self-aware and then to reject it later, but Domhnall was in my mind because it’s a funny part… It’s not something that all male actors want to do, in a way, to be the recipient, to be on the receiving end so much and I just knew that he could do it.

RJ: At the same time, it’s also a part that, to his credit, it’s deceptive… he’s doing so much in it with so little and he’s so good at communicating, largely reacting to the world around him, guiding the viewer through the story.

AG: And not telegraphing what’s actually going on. Because it can be hard for everybody to avoid the nudges and winks, like “I’m actually more powerful in this scene than you think I am.” But he was incredibly disciplined about that.

Designing Ava

AG: With Ava, it was a three step process, with a step back thing which is this is a post-iPhone world. We’re used to tech being beautifully designed essentially. Initially, it was to do with what she didn’t look like. C-3PO, for example, was a problem. Gold metal immediately put C-3PO in mind. White plastic put Chris Cunningham’s Bjork video [for “All Is Full Of Love” in mind] which was also riffed on by “I Robot.” [And] even if people haven’t seen “Metropolis,” [Maria] is an iconic image that it casts an incredibly long shadow. So, when she first appears you don’t want to initially be thinking of another film.

Second thing, she had to unambiguously be a machine so that it didn’t give wise in the narrative the possibility that it might be a young woman wearing a robot suit. So, missing areas of her body dealt with that. More important than that, the breakthrough aspect was this mesh that follows the contours of Alicia Vikander’s body, which meant that you immediately see her as a machine and then you immediately start to move away from that because as the light captures it a bit like a spiderweb, invisible in some circumstances, visible in others… you get this glancing, ephemeral sense of a young woman.

Misdirecting the Audience

RJ: As a filmmaker, I’m curious in terms of the editing, when you got into the cutting room was there anything that surprised you that you had to adjust in terms of where the audience was keeping up with it, or what they were thinking during different parts of it?

AG: I think, in the edit, of this and other projects, from my point of view, you have to run on instinct because you’re so steeped in it. At least in my experience, it’s very hard to be precise and rational about it. Wood for the trees, essentially. But there were some things I felt pretty sure of, and one thing was that we could nudge the audience or sections of the audience. Some people just want a story and will just accept whatever comes and others, their antennae are up and they are hunting and they want to get ahead of it in some way. And I felt pretty sure that there were two key misdirections we could do that would take attention away from the other stuff we wanted to keep more covert. But one of them was that audiences, you can assume literacy in film audiences. They will have seen “Blade Runner,” for example. And so they will be thinking “I know what’s going on”—

RJ: Domhnall is a robot.

AG: Right, exactly, so there are symmetrical scars on his back. And there’s a slightly implausible backstory.

RJ: Which you only reveal very slightly in the thing so even as an audience member you’re thinking, “How clever, I just caught that.”

AG: Exactly, yeah. So one is that train of thought that then leads to him investigating himself, in a way that an audience might have investigated him as well. And the other was the Japanese-appearing robot, Kyoko, that of course also people will know quite quickly that this is a machine. And in intention, I hoped, the antennae twitching audience will relax and think “oh I get this.” I think the ideal state is to just let the thing happen. You know, I sometimes think the best way to see a film — no, I know — no trailer, no information. Certainly, that for me, that’s my favorite way. So, in a way, the edit was partly about using those misdirections, I guess.

RJ: No, I think it all works to its benefit. And like I said, ultimately, it does that magic trick that my favorite movies all do, which is, it does exactly what it told you it was going to do and you’re surprised by it by the end.

Also, here is a video of the Q&A session above if you’re interested in watching it: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/83375013-132.html

#spoilers#oscar isaac#ex machina#alex garland#rian johnson#podcast#domhnall gleeson#alicia vikander#star wars#the last jedi#the playlist#the arclight#q&a#audio

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

in the download link there are #208 rp icons of alicia vikander as ava in ex machina. none of the caps are mine, i give credit here. feel free to do whatever you like with them but if you re-release please give me credit. please like and/or reblog these if they help you at all. tw: violence.

(download here)

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alex Garland as Auteur: Apathetic Existentialism

Film attempts to use emotion to reinforce the notion that mankind is the greatest product of the universe – that everything revolves around what we want and what we need. No matter the genre or the style, most film obeys a generic structure that, over its runtime, follows a hero’s ordinary life, a sudden conflict, and their overcoming that conflict so that the world can carry on either as it did before, or better. But filmmaker Alex Garland has a different perspective that defines his auteur style – one that is grim enough to be called cynical, but that might be intellectual enough to be termed apathetic instead. Garland’s films indicate that humans are so inherently materialistic that we cannot work together even when our own goals are the same. We are bound to turn to conflict, usually to find ways to be self-serving quickly, which ultimately leads to self-destruction instead. Garland’s philosophy combats the innate belief that humans cannot not exist, and instead offers up a different question: Is it really so bad that mankind, like all things, will eventually come to an end?

He may have only just begun to explore these ideas of existentialism as a director recently, but as a screenwriter, Garland’s themes reach all the way back to his first project, British zombie drama 28 Days Later (2002). Near the end of 28 Days, during a dinner scene in between zombie attacks, one soldier seems to dictate Garland’s philosophy out loud: “If you look at the whole life of the planet, we… you know, man, has only been around for a few blinks of an eye. So if the infection wipes us all out … that is a return to normality.” While this somewhat ominous line is not further explored in 28 Days, its message seems to glisten towards the end of Garland’s Ex Machina (2014), a film about AI succeeding humanity, and becomes the central theme throughout his most recent Annihilation (2018), which has a team of female scientists exploring a supernatural ‘shimmer’ that threatens to biologically modify the entire globe. Other aspects representative of Garland’s narrative style as an auteur are also rooted in 28 Days but become more fully fledged in these later films of his. Namely, unconventional methods of storytelling broken into a prologue, epilogue, and several sequences or chapters in between, unnecessary conflicts between characters who fail to intercommunicate, and unexpected feelings of nuanced hope in seemingly despondent situations.

At both the beginning and the end of 28 Days, not counting Garland’s signature prologue and epilogue scenes, the main character wakes up in a hospital bed, creating a symmetrical structure throughout the story. The middle of the film is vaguely divided up into two sequences, one inside London, and the other outside the city at a military house. Conflict between allies is introduced in the prologue when a scientist fights with animal activists to keep an infected chimpanzee quarantined, in the middle when survivors argue over whether to remain at or leave their current hideout, and near the end when the protagonists and the military clash with each other rather than uniting against the zombies. In all of the situations, each respective party thinks they are doing what is necessary to survive, but each is also guilty of failing to reason with the other. Every time conflict arises, no one is capable of stepping back, analyzing the situation, and communicating individual logic to placate it. Instead, chaos reigns supreme. While some might angrily disregard this as an example of lazy character design, that would be missing the point that Garland is trying to make. We are so quick to defend our actions that we do not care to be proven wrong. In tense situations, humans are prone to act on impulse, something that makes us not much smarter than a zombie anyway. It is for this reason – that humans are too selfish and too foolish – that Garland hypothesizes we should not expect to last forever.

Ex Machina and Annihilation take Garland’s narrative structure to a whole new level by using actual transitions to divide and title sequences onscreen as if they were part of a storybook. While this design choice might add a certain artistic flair to Garland’s films, it also acts to underline the significance of the beginnings and endings of his stories. If the titled sequences are the individual chapters of a novel, the first and last scenes are the hard book covers. The most important function of these sequences is to either divert from or highlight the events that take place at either end of both films. Each prologue takes place in medias res, acting as a hook to draw the audience in, and each epilogue is ambiguous and open-ended, meant to provoke controversial discussion. For example, the majority of Ex Machina focuses on Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), an amateur programmer, performing an advanced Turing Test on an AI, Ava (Alicia Vikander), over the course of about a week. White font on a black screen orients the audience during Caleb and Ava’s meetings together: “Ava: Session 1,” “Ava: Session 2,” etc. But it is the first and last scenes, not the sequenced meetings, that embody the message of the film as a whole. The former introduces us to Caleb’s departure from life and his arrival at Ava’s birthplace, the research facility hidden in the mountains. The latter presents the inverse, with Ava escaping from her home, replacing Caleb in the helicopter, and potentially replacing humanity on the Earth. Like Ava tricks Caleb into helping her escape, the title sequences trick the audience into viewing Ava as a harmless test, allowing her to pave her way into their hearts and thus into a new civilization where AI are the rulers of the modern world.

The same exact style is used for transitions in Annihilation, but of course with more relevant titles such as “Area X,” “The Shimmer,” and “The Lighthouse.” In this case, the purpose of the titles is almost the opposite as in Ex Machina: not to divert audiences, but to assist them instead. Annihilation is so nonlinear, confusing, and obscure that at times even it seems unsure of what it is trying to say. Lest audiences get frustrated with the apparent lack of progress that the characters in the film verbally acknowledge, these titles help emphasize that there is a final act with a sufficient payoff coming in the future. Of course, this could simply be keeping with the theme of sequences that Garland employed in his previous film, but perhaps it is a continuation of his writing off the human race as ignorant and needy instead. Perhaps Garland thought that he could not hold general audiences to the end of Annihilation without offering some trail of breadcrumbs to nibble on as they anticipate Lena’s fate in The Shimmer.

Another way that both Ex Machina and Annihilation expand on themes from 28 Days is through their use of time and lighting. Both films follow a particular day/night cycle, with important exposition moving the story forward and building tension during the daytime so that one simple conversation or discovery can instantly initiate a climactic dispute amongst allies at night. In this way, Garland evolves his original theme into more than just a narrative device, but a visual one as well. The Day represents a time when new discoveries and relationships invoke fascination and wonder about the changing world, but The Night represents a parallel perspective when those same discoveries can seem unnatural, wrong, or downright evil. In other words, the day/night cycle indicates that there are no true protagonists or antagonists in either film, but that the changing surroundings and circumstances of the characters distorts their perceptions of each other.

In Ex Machina, Caleb asks Ava questions, exchanges friendly banter with her creator Nathan (Oscar Isaac), and explores the environment during the day, but it is during his intense discussions at night with Nathan that the audience feels most anxious, like they, along with Caleb, are the ones being watched and interrogated. The gradual shifts in lighting play a large role in distorting that feeling too, with the audience feeling more trusting of characters flooded by daylight or fluorescents and more anxious when pale tungsten or bright red highlights the space. In fact, the only times when Ava’s motives are directly indicated are when she turns off the main power and activates the red glow that is representative of the iconic HAL 9000. Nevertheless, Caleb is too in love with her to notice. When Nathan and Caleb finally realize that they have been meddling with each other while Ava has been playing them both, it is too late to go back and readjust their perspectives to make amends. The sheer feelings of conflict between them evoked by the surrounding circumstances have already overpowered any logic, and Caleb’s impulses to free Ava rather than to tap into his knowledge on the danger of AI leads to his unfortunate fate, even though the ethics of his decision might have seemed moral.

Correspondingly, in Annihilation, Lena (Natalie Portman) and the other scientists struggle to differentiate between their relationship with their surroundings and with each other. They travel deeper and deeper into The Shimmer during the daytime, witnessing both the strange beauty and the horror of a space with otherworldly biological rules, but at night, when darkness hides the contours of each other’s faces, the scientists cannot help but turn on one another. Garland is extremely conscious of the tone of his conversations, stressed by the overwhelming amount of scenes containing silence instead. Dialogue which begins as purely expositional gradually shifts into the realm of confrontational as the film progresses. While Lena and the other scientists do have a few run-ins with monsters, it is their failure to trust each other that ultimately destroys the team. In one particular instance, for example, a terrific beast clearly inspired by Cronenburg shrieks with the exact voice of its dead victim, the anthropologist Cassie (Tuva Novotny). As the beast kills Anya (Gina Rodriguez), the paramedic who had just turned on her own allies in a frenzied state, the triumphant screams of a Cass-long-gone remind the team that it is not the monsters, but their own inability to work together, that is leading them towards death.

Some aspects of Ex Machina and Annihilation that point to Alex Garland as an up-and-coming auteur have less to do with his fatalistic themes on the human race and more to do with the stylistic choices acquired by means of his consistent use of similar cast and crew. The director of photography Rob Hardy, production designer Mark Digby, costume designer Sammy Sheldon, set decorator Michelle Day, and musicians Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury, for example, were all employed in both films, and their expertise comes together nicely to create atmospheres that manage to feel melancholy yet warm and dystopian yet beautiful in each. Ex Machina is filled with juxtaposition, taking place in an exquisite home that is also a horrifying research center, surrounded by rivers but imprisoned by mountains. Likewise, Annihilation explores contrasted wildlife where stags can grow flowers on their antlers but alligators can develop the teeth of a shark in their mouths. Subtle visual effects are important aspects of Garland’s film too because they enhance a world we live in now to create subjects that are nonexistent but not implausible. Ava moves more realistically than any artificially intelligent robot known today, but we would not be surprised to see a major corporation like Amazon or Google unveil a model just like her at any time. Garland addresses this in an interview with IndieWire: “’When is this taking place, I’d say it’s 10 minutes in the future’” (Whale). Similarly, there are no actual creatures or plants on Earth like the ones in Annihilation, but the film never presents something so alien that it would be immediately dismissed as unbelievable. The only thing that is purely extraterrestrial is the meteorite itself; everything else is a product of crossbreeding between objects from our world made possible by another.

The most refined relationship on set is clearly between Garland and his DOP, Rob Hardy, since the most comparable technical aspect of the two films is the pattern of the camera. Close-ups point to the ‘threat against humanity’ in each film – Ava’s brain in the first and the cells duplicating inside The Shimmer in the second. Important artifacts like these are placed in the center of the frame as the camera slowly moves closer and closer to them, almost seductively. In a style similar to that of David Fincher, slight movements of the camera continue in other scenes as well, like a person’s slow breaths, following characters as they sit, move, or speak in order to track them without drawing too much attention to the presence of a camera itself. In fact, the only times when the camera stays immobile is during wide-shots of nature that link the main sequences but provide a bit of breathing room in between important moments in the narrative.

One of the most evident similarities bridging the connection between Ex Machina and Annihilation is through actor Oscar Isaac, who was utilized in both films for more than just his stellar acting, but for his significance in Garland’s underlying themes as well. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Isaac functions as a metaphor for higher power in each of Garland’s films: “In Ex Machina, Isaac’s Nathan likens himself to God, providing his ability to create true artificial intelligence pans out. In Annihilation, it’s once again Isaac, this time portraying Lena’s husband, Kane, who opens up the subject of the divine and leads Lena to state, without hesitation, that ‘God makes mistakes.’” (Newby). It is ironic to consider films penned and directed by someone who identifies as an atheist as being religious, but Newby has a point that can be sufficiently validated by the intense saturation of Eden-like paradises and the open-ended epilogues of all three Alex Garland films discussed in this essay. No matter how cynical Garland’s beliefs about mankind’s future might be, a certain theme of hope – not the kind of hope one expects or wishes for, but hope nonetheless – is persistent in all three endings. At the end of 28 Days Later, the protagonists finally signal their location to an overhead jet and anticipate freedom. What exactly is waiting for them outside of Britain is ambiguous (the film ends before we get a chance to see); for all they know, the rest of the world could be infected too, but there is a possibility that life still exists somewhere. The final scene in Ex Machina depicts the AI, Ava, abandoning Caleb and blending into mundane human life at an ordinary crossroad. While this image definitely provokes a feeling of existential dread at the thought of a robot transcending the role of mankind, it is also pleasing to consider that some evolved form of being might replace Homo Sapiens in the future as we did the Neanderthals before us. Annihilation’s final shot of Lena and her husband as potentially alien or genetically mutated beings conjures up a similar notion about existentialism that actually seems to reject Darwinism: it is not evolution that exists, but simply adaptation.

These films hypothesize that eventually, the world as we know it will likely come to an end, replaced by science, technology, evolution, or a divine power. But who are we to know? Perhaps the details of the next step do not matter. Of course, it is up for debate whether this apathetic ambivalence about the future of mankind is unethical. After all, should we not preserve our own species by fighting against current world dangers such as artificial intelligence and global warming? Some would say yes, and Garland might even agree, but it is clear that he believes his purpose is to raise these questions, not to answer them. In his films, just as in religion itself, the prospect of abandoning the present and moving on to some new reality, whatever that might be, is inevitable, and to Alex Garland, there is nothing wrong with that.

Newby, Richard. “'Annihilation' and 'Ex Machina' Are a Double Feature in the Making.” The Hollywood Reporter, 25 Feb. 2018, www.hollywoodreporter.com/heat-vision/annihilation-machina-are-a-double-feature-making-1088109. Accessed 8 March 2018.

Whale, Chase. “Interview: Alex Garland Talks Lo-Fi Approach To 'Ex Machina,' Auteur Theory, And Much More.” IndieWire, 7 Apr. 2015, www.indiewire.com/2015/04/interview-alex-garland-talks-lo-fi-approach-to-ex-machina-auteur-theory-and-much-more-265335/. Accessed 8 March 2018.

#annihilation#28days#ai#artificial intelligence#alex garland#ex machina#film#analysis#review#philosophy#opinion

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

how about a classic becks movie rec post?

This was so much harder to cut down than the books one was! I did the best I could but since @johnwatso wanted my little comments on the vibe and that got long, it’s under the cut

General

The Dark Knight - one of my bby heath’s best performances, one of the only superhero films I’ll ever love

Pride and Prejudice - I love these straights with my entire heart

The Importance of Being Earnest - this is my kind of comedy tbh

Room - really hard to watch at points but it’s one of those movies that made me fall back in love with film, I found it breathtaking

The Truman Show - my worst nightmare in a really good film

Inception - I’m still fucked up by this film honestly, what kind of messed up thriller action @ christopher nolan

The Social Network - andrew garfield going off in this film is everything

Walk the Line - did you know this is another film I used to watch at least once a week for a couple of years

Lion - I cried and cried, the casting for little saroo and then dev patel is perfection

Jackie - admittedly the being brought up around jfk obsession might be an influencing factor here but what a performance from natalie portman

Ex Machina - that oscar isaac dance scene will stay with me

Gone Girl - more women fucking things up tbh!!!

The Lives of Others - this follows a Stasi officer who is eavesdropping on a couple and it’s one of the most fantastically put together, heart beating fast films I’ve ever seen

Get Out - I can’t wait for jordan peele to do more stuff, this was truly an instant classic horror film

Sense and Sensibility - I think in hindsight 7 year old me was just a bit in love with kate winslet in this movie, this is still a go to comfort film for me

Romeo + Juliet - as some of you know, I was weirdly obsessed with this movie at age 5 to the point where I’ve seen it hundreds of times so that’s a thing

Persepolis - such a beautiful mixture of gorgeous style and social commentary

Dead Poets Society - absolutely heartbreaking, even worse now with robin williams but a complete must watch if you’re a film lover

Atonement - so many shots in this are completely stunning, a story that will stick with you and also my fave film costume of all time (keira in that green dress)

The King’s Speech - colin firth as king george vi, v quiet gentle film but fantastic

You’ve Got Mail - the height of 90s romcoms with tom hanks and meg ryan and a classic in my heart

Bridesmaids - honestly I can never remember laughing more in the cinema than I did at this movie, I need more good female comedy films

Catch Me If You Can - I just love the playful chase vibe of this film, leo dicaprio was so perfect for it

Misery - read the book first pls!! but then come and enjoy how fucking incredible and terrifying kathy bates is in this film

Musicals

Moulin Rouge - this is one of the film loves of my life, there’s not a single moment you could ask me if I want to watch it and I’d say no

The Sound of Music - man did I go through a sound of music obsession as a kid, I was brought to the singalong as a 7 year old and

Singin’ in the Rain - the dancing alone brings me an unreasonable level of joy, should also be in the classics section and perfect to watch at christmas

Once - this is close to my heart since it’s set all over my city but it’s also just quietly beautiful with one of my favourite soundtracks ever

Billy Elliot - I love the film even more than the stage version, everything about it is so well done and young jamie bell is perfect as our little ballet dancer

Chicago - this film is just such a joy, like considering the subject matter is murder it’s so much fun

Classics

The Philadelphia Story - I also fell in love with katherine hepburn in this film, her with cary grant and james stewart is some of the most amazing early comic timing

Brief Encounter - this is a classic romance on its head a bit and it was a film I absolutely could not thinking about as a young teen, completely fascinating

It Happened One Night - fucking love it, claudette colbert is unbelievable with that sharp tongue and that hitchhicking scene is Iconic

Rebecca - does it feel conceited to say one of my fave films is my name? sure but while this isn’t quite the book, it’s such a classic suspense film

Funny Face - okay that age difference is fucked but audrey hepburn absolutely shines in this film, there’s one dance scene of hers that going to haunt me forever bc it’s weird and oddly sexy and a little genius

Some Like It Hot - great and hilarious all round with amazing comic timing plus classic marilyn, prob one of the first classics I ever fell in love with as a kid

LGBT

Moonlight - this is up there as my joint fave film of all time, it moved me unlike almost anything else I’d ever seen and I think about it every single day of my life

Pride - great story of the lesbians and gays support the miners movement, there’s so much love and joy and pride in this film and it means so much to me

Brokeback Mountain - fun fact: this is the first gay movie I ever saw and I used to watch it at least once a month if not weekly until heath died and I couldn’t anymore but it’s still one of the most heartbreaking and meaningful things in the world to me even if it’s incredibly tragic and ruined me

Carol - 50s lesbians!! they love each other!! I would die for them!!

The Way He Looks - beautiful brazilian teen love story, one of the scenes is the most tender thing and it still makes my heart flutter

The Normal Heart - all the pain, set during the aids crisis and will shatter your heart completely

A Single Man - this film hurts and just be warned for death in general in it but it’s stylistically stunning, as we should expect from tom ford

I Killed My Mother - I think this is still my fave xavier dolan film, plus the paint scene is another iconic one

Documentaries

Citizenfour - the edward snowden stuff fascinates me, watch this rather than the utter shit that is the snowden film

13th - I would watch anything that ava duvernay makes and this is a particularly well made look into race and the prison system

The Queen of Ireland - a bit of a personal thing since my local gay bar is owned by the drag queen star of this film panti bliss but it’s a good look into lgbt stuff in ireland as well

The Celluloid Closet - essential gay documentary watching, gave me as a baby gay a lot to think about

12 notes

·

View notes