#england's protestantism

Text

random thought bc I've been listening to Six on repeat: the queens claim that the only reason they're remembered is because of Henry, but would Henry be one of the most iconic and well-known English monarchs if not for them?

#like his defining trait is sorta 'bloke who had six wives who he treated pretty badly all told' plus the whole church of england thing#which arguably would have happened anyway in some sense since protestantism was sweeping europe but is generally credited to him wanting#a divorce whether thats accurate or not#yes he was quite charismatic etc but there were plenty of others who were too or at least interesting#like nobody talks about the guy who was Probably murdered in a framed hunting accident#or the one who was executed by having a red hot poker rammed up his arse#or the one who dies after gorging himself on strawberries and eel pie iirc#ok fine maybe i only remember the memorable daeths but you get the point#the six wives are what made henry viii significant is what i'm saying#via shitposts#six#six the musical#tudors#tudor queens#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#katherine howard#catherine parr#henry viii

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why People Are Wrong About the Puritans of the English Civil War and New England

Oh well, if you all insist, I suppose I can write something.

(oh good, my subtle scheme is working...)

Introduction:

So the Puritans of the English Civil War is something I studied in graduate school and found endlessly fascinating in its rich cultural complexity, but it's also a subject that is popularly wildly misunderstood because it's caught in the jaws of a pair of distorted propagandistic images.

On the one hand, because the Puritans settled colonial New England, since the late 19th century they've been wrapped up with this nationalist narrative of American exceptionalism (that provides a handy excuse for schoolteachers to avoid talking about colonial Virginia and the centrality of slavery to the origins of the United States). If you went to public school in the United States, you're familiar with the old story: the United States was founded by a people fleeing religious persecution and seeking their freedom, who founded a society based on social contracts and the idea that in the New World they were building a city on a hill blah blah America is an exceptional and perfect country that's meant to be an example to the world, and in more conservative areas the whole idea that America was founded as an explicitly Christian country and society.

Then on the other hand, you have (and this is the kind of thing that you see a lot of on Tumblr) what I call the Matt Damon-in-Good-Will-Hunting, "I just read Zinn's People's History of the United States in U.S History 101 and I'm home for my first Thanksgiving since I left for colleg and I'm going to share My Opinions with Uncle Burt" approach. In this version, everything in the above nationalist narrative is revealed as a hideous lie: the Puritans are the source of everything wrong with American society, a bunch of evangelical fanatics who came to New England because they wanted to build a theocracy where they could oppress all other religions and they're the reason that abortion-banning, homophobic and transphobic evangelical Christians are running the country, they were all dour killjoys who were all hopelessly sexually repressed freaks who hated women, and the Salem Witch Trials were a thing, right?

And if anyone spares a thought to examine the role that Puritans played in the English Civil War, it basically short-hands to Oliver Cromwell is history's greatest monster, and didn't they ban Christmas?

Here's the thing, though: as I hope I've gotten across in my posts about Jan Hus, John Knox, and John Calvin, the era of the Reformation and the Wars of Religion that convulsed the Early Modern period were a time of very big personalities who were complicated and not very easy for modern audiences to understand, because of the somewhat oblique way that Early Modern people interpreted and really believed in the cultural politics of religious symbolism.

So what I want to do with this post is to bust a few myths and tease out some of the complications behind the actual history of the Puritans.

Did the Puritans Experience Religious Persecution?

Yes, but that wasn't the reason they came to New England, or at the very least the two periods were divided by some decades. To start at the beginning, Puritans were pretty much just straightforward Calvinists who wanted the Church of England to be a Calvinist Church. This was a fairly mainstream position within the Anglican Church, but the "hotter sort of Protestant" who started to organize into active groups during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I were particularly sensitive to religious symbolism they (like the Hussites) felt smacked of Catholicism and especially the idea of a hierarchy where clergy were a better class of person than the laity.

So for example, Puritans really first start to emerge during the Vestments Controversy in the reign of Edward VI where Bishop Hooper got very mad that Anglican priests were wearing the cope and surplice, which he thought were Catholic ritual garments that sought to enhance priestly status and that went against the simplicity of the early Christian Church. Likewise, during the run-up to the English Civil War, the Puritans were extremely sensitive to the installation of altar rails which separated the congregation from the altar - they considered this to be once again a veneration of the clergy, but also a symbolic affirmation of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.

At the same time, they were not the only religious faction within the Anglican Church - and this is where the religious persecution thing kicks in, although it should be noted that this was a fairly brief but very emotionally intense period. Archbishop William Laud was a leading High Church Episcopalian who led a faction in the Church that would become known as Laudians, and he was just as intense about his religious views as the Puritans were about his. A favorite of Charles I and a first advocate of absolutist monarchy, Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canturbury in 1630 and acted quickly to impose religious uniformity of Laudian beliefs and practices - ultimately culminating in the disastrous decision to try imposing Episcopalianism on Scotland that set off the Bishop's Wars.

The Puritans were a special target of Laud's wrath: in addition to ordering the clergy to do various things offensive to Puritans that he used as a shibboleth to root out clergy with Puritan sympathies and fire them from their positions in the Church, he established official religious censors who went after Puritan writers like William Prynne for seditious libel and tortured them for their criticisms of his actions, cropping their ears and branding them with the letters SL on their faces. Bringing together the powers of Church and State, Laud used the Court of Star Chamber (a royal criminal court with no system of due process) to go after anyone who he viewed as having Puritan sympathies, imposing sentences of judicial torture along the way.

It was here that the Puritans began to make their first connections to the growing democratic movement in England that was forming in opposition to Charles I, when John Liliburne the founder of the Levellers was targeted by Laud for importing religious texts that criticized Laudianism - Laud had him repeatedly flogged for challenging the constitutionality of the Star Chamber court, and "freeborn John" became a martyr-hero to the Puritans.

When the Long Parliament met in 1640, Puritans were elected in huge numbers, motivated as they were by a combination of resistance to the absolutist monarchism of Charles I and the religious policies of Archbishop Laud - who Parliament was able to impeach and imprison in the Tower of the London in 1641.

This relatively brief period of official persecution that powerfully shaped the Puritan mindset was nevertheless disconnected from the phenomena of migration to New England - which had started a decade before Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury and continued decades after his impeachment.

The Puritans Just Wanted to Oppress Everyone Else's Religion:

This is the very short-hand Howard Zinn-esque critique we often see of the Puritan project in the discourse, and while there is a grain of truth to it - in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Congregational Church was the official state religion, no other church could be established without permission from the Congregational Church, all residents were required to pay taxes to support the Congregational Church, and only Puritans could vote. Moreover, there were several infamous incidents where the Puritan establishment put Anne Hutchinson on trial and banished her, expelled Roger Williams, and hanged Quakers.

Here's the thing, though: during the Early Modern period, every single side of every single religious conflict wanted to establish religious uniformity and oppress the heretics: the Catholics did it to the Protestants where they could mobilize the power of the Holy Roman Emperor against the Protestant Princes, the Protestants did it right back to the Catholics when Gustavus Adolphus' armies rolled through town, the Lutherans and the Catholics did it to the Calvinists, and everybody did it to the Anabaptists.

That New England was founded as a Calvinist colony is pretty unremarkable, in the final analysis. (By the by, both Hutchinson and Williams were devout if schismatic Puritans who were firmly of the belief that the Anglican Church was a false church.) What's more interesting is how quickly the whole religious project broke down and evolved into something completely different.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and ultimately it kind of broke the authority of the Congregationalist Church and led to its eventual dis-establishment.

The Puritans are the Reason America is So Evangelical:

This is another area where there's a grain of truth, but ultimately the real history is way more complicated.

Almost immediately from the founding of the colony, the Puritans begin to undergo mutation from their European counterparts - to begin with, while English Puritans were Calvinists and thus believed in a Presbyterian form of church government (indeed, a faction of Puritans during the English Civil War would attempt to impose a Presbyterian Church on England.), New England Puritans almost immediately adopted a congregationalist system where each town's faithful would sign a local religious constitution, elect their own ministers, and decide on local governance issues at town meetings.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and accusing one another of being witches. (More on that in a bit.)

And then the Great Awakening - which to be fair, was a major evangelical effort by the Puritan Congregationalist Church, so it's not like there's no link between evangelical - which was supposed to promote Congregational piety ended up dividing the Church and pretty soon the Congregationalist Church is dis-established and it's safe to be a Quaker or even a Catholic on the streets of Boston.

But here's the thing - if we look at which denominations in the United States can draw a direct line from themselves to the Congregationalist Church of the Puritans, it's the modern Congregationalists who are entirely mainstream Protestants whose churches are pretty solidly liberal in their politics, the United Church of Christ which is extremely cultural liberal, and it's the Unitarian Universalists who are practically issued DSA memberships. (I say this with love as a fellow comrade.)

By contrast, modern evangelical Christianity (although there's a complicated distinction between evangelical and fundamentalist that I don't have time to get into) in the United States is made up of an entirely different set of denominations - here, we're talking Baptists, Pentacostalists, Methodists, non-denominational churches, and sometimes Presbyterians.

The Puritans Were Dour Killjoys Who Hated Sex:

This one owes a lot to Nathaniel Hawthorne's Scarlet Letter.

The reality is actually the opposite - for their time, the Puritans were a bunch of weird hippies. At a time when most major religious institutions tended to emphasize the sinful nature of sex and Catholicism in particular tended to emphasize the moral superiority of virginity, the Puritans stressed that sexual pleasure was a gift from God, that married couples had an obligation to not just have children but to get each other off, and both men and women could be taken to court and fined for failing to fulfill their maritial obligations.

The Puritans also didn't have much of a problem with pre-marital sex. As long as there was an absolute agreement that you were going to get married if and when someone ended up pregnant, Puritan elders were perfectly happy to let young people be young people. Indeed, despite the objection of Jonathan Edwards and others there was an (oddly similar to modern Scandinavian customs) old New England custom of "bundling," whereby a young couple would be put into bed together by their parents with a sack or bundle tied between them as a putative modesty shield, but where everyone involved knew that the young couple would remove the bundle as soon as the lights were turned out.

One of my favorite little social circumlocutions is that there was a custom of pretending that a child clearly born out of wedlock was actually just born prematurely to a bride who was clearly nine months along, leading to a rash of surprisingly large and healthy premature births being recorded in the diary of Puritan midwife Martha Ballard. Historians have even applied statistical modeling to show that about 30-40% of births in colonial America were pre-mature.

But what about non-sexual dourness? Well, here we have to understand that, while they were concerned about public morality, the Puritans were simultaneously very strict when it came to matters of religion and otherwise normal people who liked having fun. So if you go down the long list of things that Puritans banned that has landed them with a reputation as a bunch of killjoys, they usually hide some sort of religious motivation.

So for example, let's take the Puritan iconoclastic tendency to smash stained glass windows, whitewash church walls, and smash church organs during the English Civil War - all of these things have to do with a rejection of Catholicism, and in the case of church organs a belief that the only kind of music that should be allowed in church is the congregation singing psalms as an expression of social equality. At the same time, Puritans enjoyed art in a secular context and often had portraits of themselves made and paintings hung on their walls, and they owned musical instruments in their homes.

What about the wearing nothing but black clothing? See, in our time wearing nothing but black is considered rather staid (or Goth), but in the Early Modern period the dyes that were needed to produce pure black cloth were incredibly expensive - so wearing all black was a sign of status and wealth, hence why the Hapsburgs started emphasizing wearing all-black in the same period. However, your ordinary Puritan couldn't afford an all-black attire and would have worn quite colorful (but much cheaper) browns and blues and greens.

What about booze and gambling and sports and the theater and other sinful pursuits? Well, the Puritans were mostly ok with booze - every New England village had its tavern - but they did regulate how much they could serve, again because they were worried that drunkenness would lead to blasphemy. Likewise, the Puritans were mostly ok with gambling, and they didn't mind people playing sports - except that they went absolutely beserk about drinking, gambling, and sports if they happened on the Sabbath because the Puritans really cared about the Sabbath and Charles I had a habit of poking them about that issue. They were against the theater because of its association with prostitution and cross-dressing, though, I can't deny that. On the other hand, the Puritans were also morally opposed to bloodsports like bear-baiting, cock-fighting, and bare-knuckle boxing because of the violence it did to God's creatures, which I guess makes them some of the first animal rights activsts?

They Banned Christmas:

Again, this comes down to a religious thing, not a hatred of presents and trees - keep in mind that the whole presents-and-trees paradigm of Christmas didn't really exist until the 19th century and Dickens' Christmas Carol, so what we're really talking about here is a conflict over religious holidays - so what people were complaining about was not going to church an extra day in the year. I don't get it, personally.

See, the thing is that Puritans were known for being extremely close Bible readers, and one of the things that you discover almost immediately if you even cursorily read the New Testament is that Christ was clearly not born on December 25th. Which meant that the whole December 25th thing was a false religious holiday, which is why they banned it.

The Puritans Were Democrats:

One thing that I don't think Puritans get enough credit for is that, at a time when pretty much the whole of European society was some form of monarchist, the Puritans were some of the few people out there who really committed themselves to democratic principles.

As I've already said, this process starts when John Liliburne, an activist and pamphleteer who promoted the concept of universal human rights (what he called "freeborn rights"), took up the anti-Laudian cause and it continued through the mobilization of large numbers of Puritans to campaign for election to the Long Parliament.

There, not only did the Puritans vote to revenge themselves on their old enemy William Laud, but they also took part in a gradual process of Parliamentary radicalization, starting with the impeachment of Strafford as the architect of arbitrary rule, the passage of the Triennal Acts, the re-statement that non-Parliamentary taxation was illegal, the Grand Remonstrance, and the Militia Ordinance.

Then over the course of the war, Puritans served with distinction in the Parliamentary army, especially and disproportionately in the New Model Army where they beat the living hell out of the aristocratic armies of Charles I, while defying both the expectations and active interference of the House of Lords.

At this point, I should mention that during this period the Puritans divided into two main factions - Presbyterians, who developed a close political and religious alliance with the Scottish Covenanters who had secured the Presbyterian Church in Scotland during the Bishops' Wars and who were quite interested in extending an established Presbyterian Church; and Independents, who advocated local congregationalism (sound familiar) and opposed the concept of established churches.

Finally, we have the coming together of the Independents of the New Model Army and the Leveller movement - during the war, John Liliburne had served with bravery and distinction at Edgehill and Marston Moore, and personally capturing Tickhill Castle without firing a shot. His fellow Leveller Thomas Rainsborough proved a decisive cavalry commander at Naseby, Leicester, the Western Campaign, and Langport, a gifted siege commander at Bridgwater, Bristol, Berkeley Castle, Oxford, and Worcester.

Thus, when it came time to hold the Putney Debates, the Independent/Leveller bloc had both credibility within the New Model Army and the only political program out there. Their proposal:

redistricting of Parliament on the basis of equal population; i.e one man, one vote.

the election of a Parliament every two years.

freedom of conscience.

equality under the law.

In the context of the 17th century, this was dangerously radical stuff and it prompted Cromwell and Fairfax into paroxyms of fear that the propertied were in danger of being swamped by democratic enthusiasm - leading to the imprisonment of Lilburne and the other Leveller leaders and ultimately the violent suppression of the Leveller rank-and-file.

As for Cromwell, well - even the Quakers produced Richard Nixon.

#history#puritans#calvinism#english civil war#oliver cromwell#the stupid meme about christmas#new england#protestantism

443 notes

·

View notes

Text

once again need all the "medieval fantasy" fans out there to understand that by many historical opinions, the War of the Roses began AFTER the medieval period

"medieval" is a whole lot older than most of yall realize and i'm begging yall to look at a timeline before you start calling things "medieval fantasy"

#the War of the Roses is like either the first time after the medieval period#or the last thing in the medieval period depending on who you ask#for context that means ALL of Tudor England took place AFTER the medieval period regardless of which take you believe#shakespeare was AFTER the medieval period#all of Protestantism in general is AFTER the medieval period

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#historyposting#henry viii throws the religion of england into doubt -> elizabeth i cements protestantism as the national religion#james i comes to the throne as a protestant -> unhappy english catholics try to blow him up#this starts a tradition of bonfire night -> effigies of guy fawkes become known as guys#guy comes to mean a dude in general in american english -> people start arguing over whether it's gender neutral#simple really

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright uninformed rant time. It kind of bugs me that, when studying the Middle Ages, specifically in western Europe, it doesn’t seem to be a pre-requisite that you have to take some kind of “Basics of Mediaeval Catholic Doctrine in Everyday Practise” class.

Obviously you can’t cover everything- we don’t necessarily need to understand the ins and outs of obscure theological arguments (just as your average mediaeval churchgoer probably didn’t need to), or the inner workings of the Great Schism(s), nor how apparently simple theological disputes could be influenced by political and social factors, and of course the Official Line From The Vatican has changed over the centuries (which is why I’ve seen even modern Catholics getting mixed up about something that happened eight centuries ago). And naturally there are going to be misconceptions no matter how much you try to clarify things for people, and regional/class/temporal variations on how people’s actual everyday beliefs were influenced by the church’s rules.

But it would help if historians studying the Middle Ages, especially western Christendom, were all given a broadly similar training in a) what the official doctrine was at various points on certain important issues and b) how this might translate to what the average layman believed. Because it feels like you’re supposed to pick that up as you go along and even where there are books on the subject they’re not always entirely reliable either (for example, people citing books about how things worked specifically in England to apply to the whole of Europe) and you can’t ask a book a question if you’re confused about any particular point.

I mean I don’t expect to be spoonfed but somehow I don’t think that I’m supposed to accumulate a half-assed religious education from, say, a 15th century nobleman who was probably more interested in translating chivalric romances and rebelling against the Crown than religion; an angry 16th century Protestant; a 12th century nun from some forgotten valley in the Alps; some footnotes spread out over half a dozen modern political histories of Scotland; and an episode of ‘In Our Time’ from 2009.

But equally if you’re not a specialist in church history or theology, I’m not sure that it’s necessary to probe the murky depths of every minor theological point ever, and once you’ve started where does it end?

Anyway this entirely uninformed rant brought to you by my encounter with a sixteenth century bishop who was supposedly writing a completely orthodox book to re-evangelise his flock and tempt them away from Protestantism, but who described the baptismal rite in a way that sounds decidedly sketchy, if not heretical. And rather than being able to engage with the text properly and get what I needed from it, I was instead left sitting there like:

And frankly I didn’t have the time to go down the rabbit hole that would inevitably open up if I tried to find out

#This is a problem which is magnified in Britain I think as we also have to deal with the Hangover from Protestantism#As seen even in some folk who were raised Catholic but still imbibed certain ideas about the Middle Ages from culturally Protestant schools#And it isn't helped when we're hit with all these popular history tv documentaries#If I have to see one more person whose speciality is writing sensational paperbacks about Henry VIII's court#Being asked to explain for the British public What The Pope Thought I shall scream#Which is not even getting into some of England's super special common law get out clauses#Though having recently listened to some stuff in French I'm beginning to think misconceptions are not limited to Great Britain#Anyway I did take some realy interesting classes at uni on things like marriage and religious orders and so on#But it was definitely patchy and I definitely do not have a good handle on how it all basically hung together#As evidenced by the fact that I've probably made a tonne of mistakes in this post#Books aren't entirely helpful though because you can't ask them questions and sometimes the author is just plain wrong#I mean I will take book recommendations but they are not entirely helpful; and we also haven't all read the same stuff#So one person's idea of what the basics of being baptised involved are going to radically differ from another's based on what they read#Which if you are primarily a political historian interested in the Hundred Years' War doesn't seem important eonugh to quibble over#But it would help if everyone was given some kind of similar introductory training and then they could probe further if needed/wanted#So that one historian's elementary mistake about baptism doesn't affect generations of specialists in the Hundred Years' War#Because they have enough basic knowledge to know that they can just discount that tiny irrelevant bit#This is why seminars are important folks you get to ASK QUESTIONS AND FIGURE OUT BITS YOU DON'T UNDERSTAND#And as I say there is a bit of a habit in this country of producing books about say religion in mediaeval England#And then you're expected to work out for yourself which bits you can extrapolate and assume were true outwith England#Or France or Scotland or wherever it may be though the English and the French are particularly bad for assuming#that whatever was true for them was obviously true for everyone else so why should they specify that they're only talking about France#Alright rant over#Beginning to come to the conclusion that nobody knows how Christianity works but would like certain historians to stop pretending they do#Edit: I sort of made up the examples of the historical people who gave me my religious education above#But I'm now enamoured with the idea of who actually did give me my weird ideas about mediaeval Catholicism#Who were my historical godparents so to speak#Do I have an idea of mediaeval religion that was jointly shaped by some professor from the 1970s and a 6th century saint?#Does Cardinal Campeggio know he's responsible for some much later human being's catechism?#Fake examples again but I'm going to be thinking about that today

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

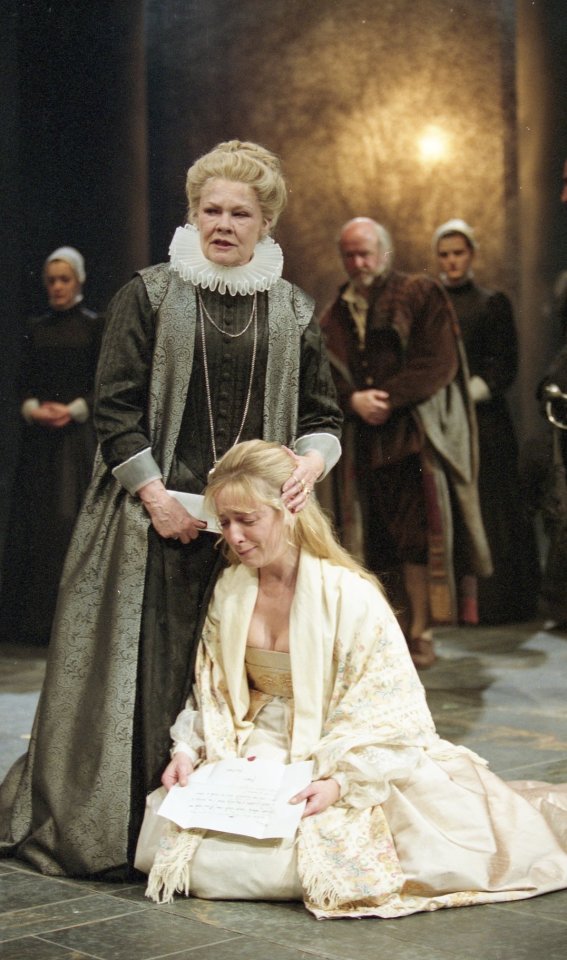

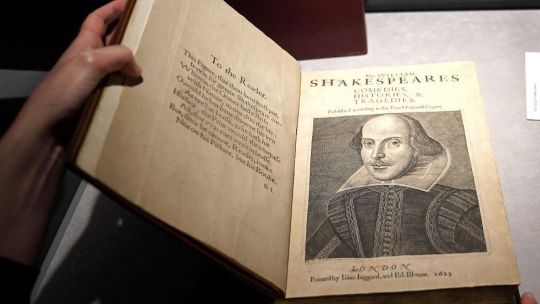

Anonymous asked: Going through your archive I loved your fantastic long posts on Shakespeare. As you know there is some debate on whether Shakespeare was either a Catholic or Protestant. Where do you stand on this issue?

The issue of Shakespeare’s religion, as you have pointed out, has been an issue that has long vexed both scholars and the educated layman. To be honest it is of little interest to me (beyond a playful parlour game) because it has never stopped me appreciating the greatness of his works.

Of course it would have mattered to Shakespeare. For in his lifetime, atheism was equated with immorality, and Catholicism in England was equated with treason. Queen Elizabeth I had executed Edward Arden, a relative of Shakespeare’s mother, for his supposed Catholic treachery. Religion was a matter of life or death; and Shakespeare, like everyone else, walked a precarious denominational line.

But if pushed I would say he was Protestant but with a Catholic imagination. I suppose this is what fence sitting looks like. But hear me out.

It’s possible to answer this seemingly simple question in lots of different ways. Like other English subjects who lived through the ongoing Reformation, Shakespeare was legally obliged to attend Church of England services. Officially, at least, he was a Protestant. But a number of scholars have argued that there is evidence that Shakespeare had connections through his family and school teachers with Roman Catholicism, a religion which, through the banning of its priests, had effectively become illegal in England. Even so, ancestral and even contemporary links with the faith that had been the country’s official religion as recently as 1558, would make Shakespeare typical of his time. And in any case, to search for a defining religious label is to miss some of what is most interesting about religion in early modern England, and more importantly, what is most interesting about Shakespeare.

Questions such as ‘was Shakespeare a Protestant or a Catholic?’ use terms that are too neat for the reality of post-Reformation England. The simple labels Catholic, Protestant, and Puritan paper over a complex way faith works in our lives. Even in less turbulent times, religion is a framework for belief; actual faith slips in and out of official doctrine. Religion establishes a set of principles about belief and practice, but individuals pick and choose which bits they listen to. I think that’s fair as someone who is a believing Anglican Christian I slip and fall in my faith all the time, but all one can do is ask for sincere forgiveness, get up, dust yourself off, and get on with your life. Until the next prat fall.

My point is that ‘Catholicism’ was an especially tricky category in this era to be definitive about. Under pressure of crippling fines and even execution, early modern Catholics maintained their faith in a variety of ways. Not every so-called papist supported the pope. The Roman Catholic Church of this era encompassed ‘recusants’ (who openly displayed their Catholicism by refusing to attend mandatory Church of England services) and ‘church papists’ (who conformed to the monarch’s protestant customs, but secretly practiced Catholicism). Some Catholics supported Elizabeth politically, looking to the pope only in spiritual matters; others plotted her overthrow.

Catholicism was in the eye of the beholder; other Protestants saw many elements of Elizabeth’s own Church as horrifyingly ‘Romish’, but to average Protestants those puritanical objections seemed hysterical. Some accepted the theology and politics of the reformation, but still harboured an emotional attachment to older traditions, like praying for the dead.

Furthermore, people have a habit of changing their minds over time, shifting their beliefs at different moments of their lives. Asking about the confessional allegiance of any early modern individual is a much more difficult – and interesting – enterprise than figuring out an either/or choice. Whatever Shakespeare’s personal faith was, he wrote plays that worked for audiences who had to feel their way through these dilemmas, audiences for whom Protestantism was the official state religion, but who experienced a far messier reality.

Playhouses provided spaces to explore these anxieties. Even though the direct representation of specific theological controversy was banned, Renaissance plays frequently featured elements of the Roman Catholic religion that had been practically outlawed in real life. Purgatorial ghosts and well-meaning friars still appeared on stage; star-crossed lovers framed their first kiss in terms of saintly intercession and statue veneration (Romeo and Juliet, 1.4.206-19); and various characters swore ‘by the mass’, ‘by the rood’, and ‘by’r lady’.

Shakespeare wrote over sixty years after Henry VIII set the Reformation in motion. By the 1590s, English friars, nuns and hermits belonged firmly to the past, and many writers used them like the formula ‘once upon a time’: to create a safely distant, fictional world. Even so, Catholic Europe and Jesuit missionaries were perceived by state authorities as a very present danger. Anti-Catholic propaganda demonised that faith as fundamentally deceitful; ‘papist’ piety was mere pretence, a cover for lechery, treachery, and sin.

Accordingly, some writers used Catholic settings as a shorthand for corruption (think of the decadent world of Webster’s Duchess of Malfi, with its murderous and lascivious Cardinal). So Catholicism could point in different fictional directions: it could benignly and nostalgically suggest an unreal past, in the manner of a fairytale; or, it could paint a threatening image of a more contemporary fraud.

But it’s striking that Shakespeare uses Catholic content rather differently from his contemporary dramatists, often embracing the contradictory connotations of, say, a friar, exploiting the figure’s nostalgic and threatening associations at the same time. This exploration of ambiguity seems to have been one way in which he thought through not only religious controversies, but also the very act of making fiction itself. A figure who works both like a fairytale and like a fraud tests out what is good and what is dangerous about literary illusion.

All’s Well that Ends Well is a case in point. This comedy tests fantasy ideals against real-life problems. Helen, the clever wench who miraculously cures a king and wins a husband of her own choosing, finds herself in love with a prince who isn’t so charming. But critics have never been too sure about whether Helen herself is a virtuous victim of her snobbish husband, or if she’s simply conniving and self-centred. By putting all of these possibilities in play Shakespeare invites us to interrogate the ideals that underpin romantic comedy: are the conventions we think of as happy endings really all that happy?

One way that Helen secures her own happy ending is by putting on a pilgrim’s habit which allows her to follow (and eventually catch) her runaway husband. But this costume, with its mixed Catholic associations, further complicates the character and the morality of the plot. While the Catholic Church regarded pilgrimage to holy places as “meritorious” (a way of piously working to the salvation that only Christ could enable), Reformers scoffed at the notion that one earthly place could be holier than another, dismissed as idolatrous the intercession of saints usually invoked at shrines, and abhorred the idea that Christ’s gift of salvation needed supplementing. Shakespeare hints both that Helen might be the hypocrite of anti-Catholic polemic, who uses a pious habit to conceal selfish intentions, and that she might be a prayerful woman, who would be justly rewarded with a happy ending.

Furthermore, the comedy also draws on more secular associations of ‘pilgrimage’, which run through the love poetry of the period figuring amorous devotion. We first learn of Helen’s pilgrimage in a letter that takes the form of the sonnet; at this point Helen is painted as something of a Petrarchan stalker, trekking her errant husband in the clothing of well-worn poetic metaphor. But Shakespeare unpicks other threads of meaning in the pilgrim costume too. In anti-Catholic fabliaux pilgrims used their religious journeys for decidedly smutty adventures. It’s probably no mistake that Helen uses her pilgrimage so that she can finally have sex. And again, there’s a question mark hanging over this behaviour. On the one hand her active desire for physical intimacy with her husband is legitimate and liberating, but on the other, she repeatedly removes her husband’s power of consent, most disturbingly in a bed-trick (a ‘wicked meaning in a lawful deed’). The comedy questions her sexual scruples.

Shakespeare exploits the various associations of the pilgrim in post-Reformation England. In Helen, papist and Catholic connotations are compounded: she is meritorious and devious, miraculous and cunning. The ‘happy ending’ of this play sees husband and wife reunited and apparently reconciled. But the ‘real’ wonder of this moment is provisional: ‘All yet seems well’ (my emphasis). The audience is very aware of the pragmatic tricks that Helen had to perform in order win this resolution. By drawing on the contradictory meanings of the pilgrim, Shakespeare creates a paradoxical character that engages his audience with the ethical dilemmas of fiction: when might the means justify the ends?

In this play, as in others, Shakespeare calls on the ambiguous associations of Catholic figures, images and ideas, as a means of engaging his audience with the problems he frames. He seems to revel in the pleasures of slippery meaning. By flirting with stereotypes and sectarian expectations he makes his audience think more deeply about the difficulties of the plays and their own culture. Whatever Shakespeare’s personal religion was, the religion he put on stage was both playful and probing.

But it is an interesting question to speculate what William Shakespeare’s religious beliefs were. I’ve had several fascinating discussions with friends and even work colleagues (between them they have a few English lit PhDs under their belt) to get a better understanding of this question.

When Shakespeare died in 1616 at age 52, he was buried in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, which would have been an impossibility for a known atheist. Yet questions about his religion arose early, some 70 years after his death, when Richard Davies, an Anglican clergyman, wrote from local legend that the poet had “dyed a Papyst.”

The controversy continued. In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson considered Shakespeare a brilliant but irreverent poet. Consider the Bard’s lines: “Why, all the souls that were, were forfeit once/ And He that might the vantage best have took/ Found out the remedy.” So speaks the Franciscan novice Isabella to the cruel judge Angelo in Shakespeare’s black comedy ‘Measure for Measure’ (1604). Is the poetry here biblical or merely “universal” in its meaning?

A century later Samuel Taylor Coleridge found the Bard’s comedic forgiveness of the judge Angelo to be morally abhorrent. While literary critics believed Shakespeare too “fanciful” and “rustic” to be orthodox, many popular authors noted Shakespeare’s encyclopaedic use of the Bible.

One my Irish work colleagues who has an English Lit PhD pointed to other commentators who entered the fray. For example in 1899, the Rev. H. S. Bowden collected the evidence in The Religion of Shakespeare, using the work of Richard Simpson to compile his pro-Catholic compendium.

She also told me that it was not until G. Wilson Knight successfully argued in The Wheel of Fire (1930) for a Christian and biblical Shakespeare that this view was accepted by what might be called the ‘Shakespeare establishment.’ For the first time in over 200 years, the problem of how the poet of “fancy” could also be a serious, Bible-loving Christian was considered solved. Yet this Shakespeare was the Protestant Shakespeare of the British Empire, not the Catholic poet of Father Bowden.

The “Catholic Shakespeare” thesis entered mainstream English criticism with E. A. J. Honigmann’s book, Shakespeare: The Lost Years (1985). It demonstrated how a butcher’s son from Warwickshire triumphed in London through connections with an aristocratic Catholic family in Lancashire, without implying that the Bard had a continuing allegiance to Rome.

The full development of the Catholic thesis, however, came in the seminal work of Peter Milward S.J. - Shakespeare’s Religious Background (1973), with further work by Ian Wilson in 1993 with this publication of his book, Shakespeare: The Evidence, which meticulously researched Shakespeare’s literary and political ties to Catholic patrons and politics.

All fine and dandy but these books never settled the question once and for all.

The main problem with claiming that Shakespeare was a Catholic recusant is the historical record: He lived and died a member of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. Other close ties to the Reformed Church include his lodging with Huguenots when in London, and the marriage of his daughter Susanna to a Protestant doctor, John Hall, after she was fined for being a Catholic recusant. That record need not contradict what appears to be sympathy for Catholicism, clearly evident in his plays; but Shakespeare also tried to present an objective approach to Rome. For example, Franciscans are depicted for their honest vocations, although cardinals are notoriously portrayed as murderous cowards.

One possible explanation for this apparent inconsistency may lie in the fact that the English Reformation was still in progress during Shakespeare’s lifetime. England remained Catholic in spirit and practice long after 1534, with parts of Lancashire still practicing the “old faith” openly. It is possible that the post-Reformation Holy Trinity Church in Warwickshire was sufficiently traditional to allow a Catholic-sympathiser like Shakespeare to participate. If the Church of England authorities knew of the poet’s Stratford affiliation, then the fact that Shakespeare’s nonattendance at Puritan-leaning London parishes went unpunished could be explained.

Despite this, the Catholic recusancy thesis - that the plays have a pro-Catholic political subtext - has never received broad acceptance amongst scholars. And as for the general public, I don’t think they care. I wouldn’t take the question too seriously either, especially if it gets in the way of enjoying Shakespeare’s works in itself.

I would conclude that the most promising avenue for appreciating Shakespeare’s Catholicity lies not in biography but rather in the recognition of his Catholic imagination, readily discoverable in his plays. Through metaphor, the poet enlarges the sensibilities through an encounter with inspired meaning. Reformed theology had posited an irreparable break between the divine and the human, whereas the Catholic imagination seeks and finds the divine in broken humanity, bridging the gap between nature and grace.

One example should suffice. A reference to the passage “Why, all the souls…” from “Measure for Measure” demonstrates how a ‘Catholic’ imagination functions poetically. The speaker, Isabella, is a devout if initially self-righteous novice with the Poor Clares of Vienna. In her first meeting with the Puritan Angelo, she pleads for the life of her brother, who is under a death sentence for impregnating his girlfriend. Angelo argues that mercy is impossible because her brother “is a forfeit of the law.” In a Pauline argument, Isabella asserts that all were condemned by sin (Rom 3:23) until the Son of God sacrificed his equality with God to achieve salvation for the world (Rom 3:24-26).

But I wouldn’t push it too far. It can be archetypal or thematic or say something of the Christian world view of sin, fallen-ness, and forgiveness, and redemption, but it’s not in your face and it’s not explicitly obvious. At the end of the day Shakespeare was a genius story teller, not a theologian or ideologue, or anything else.

This brings me to my final point. Speaking for myself as a theatre lover in general, the answer we seek must be in the context of why we love drama and Shakespeare’s theatre especially. The theatre seeks to entertain, preparing the heart and mind for reflection, while the purpose of sermons is to preach and instruct. Drama is never a sermon. And this would apply to the portrayal of Shakespeare as a proselytising Protestant, papist renegade or atheist subversive. When ideology reduces a living drama to apologetics, voices of protest will inevitably be raised. This is something we forget today as woke ideology has infected modern entertainment across the board. The Wokists - artists as activists who relentlessly peel back the onion skin until nothing is left - have forgotten the first rule of drama as truth telling: tell a good story, don’t preach.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#shakespeare#william shakespeare#plays#literature#playwright#religion#christianity#catholcism#protestantism#morality#imagination#catholic imagination#beliefs#shakespeare's religious beliefs#elizabethan england#anti-woke#woke#theatre#drama#arts#society#culture#english

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Llandaf Cathedral, South Wales

#llandaff#llandaf#llandaf cathedral#cathedral#catholiscism#protestantism#church in wales#church of england#wales#south wales#cardiff#caerdydd#stained glass#church#gothic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone (read: the internet outside tumblr (read: the tv show clips on my tiktok fyp)) is like oh watch shogun oh its so good. and im like hmm ok this looks deeply orientalist but im bored ill pirate it to hate watch. but then i didn't even get to the orientalism bc i found the main guy so deeply insufferable (read: protestant) that I had to turn it off around 5 minutes in

#it's such a choice to have the first thing revealed about your protagonist be his militant protestantism. a bad one#like yeah catholicism sucks. but have you ever met a member of the church of england

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of the Church of England visited the Romanian Patriarchate. Photo: Basilica.ro / Mircea Florescu

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

"What is the story behind bonfire night?", Union with David Olusoga, November 5, 2023

Remember, remember the 5th of November, but what are we remembering it for? 🎆 🔥

The future of the Union is today at greater threat than at any time in living memory. In this ambitious four-part, landmark series David Olusoga uncovers the long history of union and disunion, tracing their origins back centuries.

The fracture lines of our current division run along the borders between the 'home nations' but we are also disunited by social class and inequality, by England's north-south divide and the historic dominance of London. Our disunity can be told through the historic rise and fall of what are today called 'left-behind towns' and the long history of our rural-urban divide.

David’s own personal experience connect him to several regions of the UK, each with their own strong identities. He grew up in a working-class community in the North East of England, a politically independent region with an antipathy towards London. And as a mixed-race child who came Britain in the 1970s, he has seen for himself how complex and nuanced the relationship between the individual and the nations of the UK can be.

BBC

#Union with David Olugosa#BBC#Guy Fawkes#UK#history#David Olusoga#Bonfire Night#Guy Fawkes Night#Gunpowder Plot#religion#England#protestantism#catholicism#politics#monarchy#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Paul’s Cathedral, the City of London, November 2022

#my travels#my photography#such as it is#protestantism#anglicanism#this church was only ever Protestant#re: all those people dunking on Protestant architecture#the original cathedral burned down in the fire in 1666 and this one replaced it well after the Reformation in England

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like how the fandom has unspokenly, collectively decided that Pritchard's family sucks. Like we all took one look at that man and that he's from New Hampshire and went "oh god yeah that is a queer man who is not on speaking terms with his relatives"

#for context for non-americans: NH is part of the region called New England and NE is the heart of the original protestant colonies#NE is extremely protestant culturally even for individuals who aren't religious#American Protestantism is a special brand of community thought control that stresses sacrifice obsession with image and normalcy#and is particularly hostile to queer folks neurodivergent folks and poc#source: my friends from NE telling me i would hate it#and other new englanders talkin about it#francis pritchard#it also to me explains a bit of why his coping mechanism is being fucking mean#New Englanders if im missing anything important feel free to add

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tapestry of History, 12 – The Rise of the West, 7 – The Reformation, 3

(Image credit – Wikipedia – St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, Paris 1572 – by François Dubois)

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th Century is one of the pivotal events of Western History, and thereby of World History. The geopolitical state of the world in the 21st Century is, in part, attributable to the consequences of the division of Europe into Roman Catholic and Protestant nation-states…

#Christianity#Church of England#History of the West#Huguenots#John Calvin#King Francis 1 of France#Pope Paul 3#Protestant Reformation#Protestantism#Reformed Church#The Reformation#The Tapestry of History#Wars of religion

0 notes

Link

#queen elisabeth#did you know#queen elizabeth i#Christianity#christian history#religious history#protestantism#england

0 notes

Text

"Faith is the gift of God, and cannot be wrought in the hearts of men by any power of man, but only by the Holy Ghost."

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I.

Born: 2 July 1489, Aslockton, England

Died: 21 March 1556 (age 66 years), Oxford, England

Archbishop of Canterbury: Cranmer served as the Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest religious office in the Church of England, from 1533 until his death in 1556. He played a pivotal role in the English Reformation, promoting the break from the authority of the Pope and establishing the Church of England as a separate entity from the Roman Catholic Church.

Author of the Book of Common Prayer: Cranmer is perhaps best known for his work on the Book of Common Prayer, which was first published in 1549 during the reign of King Edward VI. This book provided a standardized form of worship in English, making religious services more accessible to the general population and promoting uniformity in worship practices within the Church of England.

Supporter of Henry VIII's Divorce: Cranmer played a key role in King Henry VIII's efforts to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. He provided theological and legal arguments supporting the annulment, which ultimately led to the English Reformation and the establishment of the Church of England separate from papal authority.

Martyrdom: Despite his prominence during the reign of Henry VIII and Edward VI, Cranmer's fortunes changed dramatically during the reign of Queen Mary I, a staunch Catholic. He was arrested, tried for heresy, and ultimately convicted. On March 21, 1556, Cranmer was burned at the stake as a heretic. His final recantation, where he renounced his earlier Protestant beliefs, is often cited as one of the most dramatic moments of the English Reformation.

Influence on English Protestantism: Cranmer's theological writings and liturgical reforms had a lasting impact on English Protestantism. His emphasis on Scripture, justification by faith, and the primacy of individual conscience over papal authority laid the groundwork for the development of Anglicanism as a distinct branch of Christianity. Despite his tragic end, Cranmer's legacy continues to shape the beliefs and practices of Anglicans worldwide.

#Thomas Cranmer#Archbishop of Canterbury#English Reformation#Protestantism#Church of England#Book of Common Prayer#Henry VIII#King Edward VI#Queen Mary I#Martyr#Theology#Reformer#Heresy#Papal Authority#Anglicanism#Protestant Reformation#Religious Reform#Protestant Martyr#English History#Religious Leader#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday

1 note

·

View note

Text

if you think about it murdoc and batty are kind of like roman catholicism and england in the 16th century

#txt#batty is roman catholicism and murdoc is england#the break from rome#im talking about the break from rome and the birth of protestantism#murbat#0

1 note

·

View note