#end stock buybacks

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Buying back CHIPS

The only way to stop public money from being siphoned off to shareholders and top executives

ROBERT REICH

SEP 24

Friends,

One of my goals in writing this letter is to expose where government needs to take a stronger hand to safeguard the public interest from corporate avarice.

I applaud the economic policies of the Biden-Harris administration, which have abandoned the neoliberal claptrap of former Democratic administrations and come down on the side of working people.

But I also want those policies to work. The administration’s commendable goal of reviving America’s semiconductor industry by subsidizing new chip factories in the United States is today endangered by the increasing likelihood that those subsidies will enrich big shareholders and CEOs rather than strengthen our semiconductor industrial base.

So far, nearly $30 billion in federal CHIPS grants have been awarded, with the grants going to 11 semiconductor producers.

But the major goal of these producers is not to revive America’s semiconductor industry. It’s to raise their share prices. Most of these producers have spent billions buying back their shares of stock in order to do just that.

As I’ve emphasized in previous letters to you, stock buybacks increasingly are being used by corporations to satisfy Wall Street’s insatiable demand for higher share prices.

But every dollar the semiconductor producers spend on buybacks is a dollar not spent on innovation for long-term competitiveness.

This contradiction between the public interest in a strong American semiconductor industry and corporate interests in high stock prices creates a significant risk that public subsidies in the CHIPS Act will be siphoned off to shareholders and top executives through stock buybacks.

Taxpayer money should not be used to boost share prices and CEO pay. Recipients of this money should not be allowed to engage in stock buybacks.

The first CHIPS grant of $35 million went to BAE Systems in June 2023. At the time, BAE was in the midst of a $2 billion stock buyback; another nearly $2 billion in stock buybacks has been authorized by BAE’s board.

Intel, America’s largest homegrown producer of semiconductors and already the recipient of $8.5 billion in CHIPS money has been authorized by its its board to buy back a further $7.24 billion of its own shares of stock. (Meanwhile, the administration has promised Intel nearly $20 billion in grants and loans.)

Intel spent $30.2 billion on buybacks between 2019 to 2023. It also assured investors last year that the company remained committed to delivering “very healthy” dividends.

All told, semiconductor producers now in line for $30 billion in public subsidies spent more than $41 billion on stock buybacks between 2019 and 2023.

Their CEOs — whose compensation packages are larded with stocks and stock options — have every incentive to continue pumping up their own corporations’ stock prices with buybacks.

According to a recent report from the Institute for Policy Studies and the Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund, CEOs whose corporations have entered into preliminary CHIPS agreements with the government hold more than $2.7 billion worth of stock in their companies ($306 million on average). They therefore stand to personally benefit from buybacks.

CHIPs money is being distributed to these corporations by the Commerce Department. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo has given personal assurances that “CHIPS money is not a subsidy for big companies … for stock buybacks or to pad their bottom line.” The Department has stated that when awarding grants, it will give preference to companies who commit to not engage in stock buybacks.

But none of the companies receiving CHIPS subsidies has publicly committed to suspending their existing stock buyback plans.

The Commerce Department has only asked applicant corporations to detail their plans for stock buybacks over five years. (These applications and the subsequent agreements are not public.)

Moreover, it’s relatively easy for big corporations to shift money among units or subsidiaries to obscure buybacks, especially if other corporations buy parts of them or if outside private equity investors control parts of their operations.

Intel is a case in point. The chipmaker Qualcomm is now considering buying parts of Intel’s design business and possibly its foundry unit. And the giant private equity firm Apollo Management is likely to make a big investment in Intel (Apollo has already bought a stake in Intel’s chip-manufacturing operation in Ireland).

Given the increasing pressure from Wall Street and CEOs to use stock buybacks to boost share prices, the administration must ensure that public subsidies improve the semiconductor manufacturing base and do not merely enrich shareholders and CEOs.

How do do this? My humble advice to the Secretary Raimondo and the Biden-Harris administration: Bar all semiconductor producers who receive government subsidies from making stock buybacks. Make the prohibition explicit in all final CHIPS subsidy contracts.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI’s productivity theater

Support me this summer on the Clarion Write-A-Thon and help raise money for the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop!

When I took my kid to New Zealand with me on a book-tour, I was delighted to learn that grocery stores had special aisles where all the kids'-eye-level candy had been removed, to minimize nagging. What a great idea!

Related: countries around the world limit advertising to children, for two reasons:

1) Kids may not be stupid, but they are inexperienced, and that makes them gullible; and

2) Kids don't have money of their own, so their path to getting the stuff they see in ads is nagging their parents, which creates a natural constituency to support limits on kids' advertising (nagged parents).

There's something especially annoying about ads targeted at getting credulous people to coerce or torment other people on behalf of the advertiser. For example, AI companies spent millions targeting your boss in an effort to convince them that you can be replaced with a chatbot that absolutely, positively cannot do your job.

Your boss has no idea what your job entails, and is (not so) secretly convinced that you're a featherbedding parasite who only shows up for work because you fear the breadline, and not because your job is a) challenging, or b) rewarding:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/19/make-them-afraid/#fear-is-their-mind-killer

That makes them prime marks for chatbot-peddling AI pitchmen. Your boss would love to fire you and replace you with a chatbot. Chatbots don't unionize, they don't backtalk about stupid orders, and they don't experience any inconvenient moral injury when ordered to enshittify the product:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/25/moral-injury/#enshittification

Bosses are Bizarro-world Marxists. Like Marxists, your boss's worldview is organized around the principle that every dollar you take home in wages is a dollar that isn't available for executive bonuses, stock buybacks or dividends. That's why you boss is insatiably horny for firing you and replacing you with software. Software is cheaper, and it doesn't advocate for higher wages.

That makes your boss such an easy mark for AI pitchmen, which explains the vast gap between the valuation of AI companies and the utility of AI to the customers that buy those companies' products. As an investor, buying shares in AI might represent a bet the usefulness of AI – but for many of those investors, backing an AI company is actually a bet on your boss's credulity and contempt for you and your job.

But bosses' resemblance to toddlers doesn't end with their credulity. A toddler's path to getting that eye-height candy-bar goes through their exhausted parents. Your boss's path to realizing the productivity gains promised by an AI salesman runs through you.

A new research report from the Upwork Research Institute offers a look into the bizarre situation unfolding in workplaces where bosses have been conned into buying AI and now face the challenge of getting it to work as advertised:

https://www.upwork.com/research/ai-enhanced-work-models

The headline findings tell the whole story:

96% of bosses expect that AI will make their workers more productive;

85% of companies are either requiring or strongly encouraging workers to use AI;

49% of workers have no idea how AI is supposed to increase their productivity;

77% of workers say using AI decreases their productivity.

Working at an AI-equipped workplaces is like being the parent of a furious toddler who has bought a million Sea Monkey farms off the back page of a comic book, and is now destroying your life with demands that you figure out how to get the brine shrimp he ordered from a notorious Holocaust denier to wear little crowns like they do in the ad:

https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2004/hitler-and-sea-monkeys

Bosses spend a lot of time thinking about your productivity. The "productivity paradox" shows a rapid, persistent decline in American worker productivity, starting in the 1970s and continuing to this day:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Productivity_paradox

The "paradox" refers to the growth of IT, which is sold as a productivity-increasing miracle. There are many theories to explain this paradox. One especially good theory came from the late David Graeber (rest in power), in his 2012 essay, "Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit":

https://thebaffler.com/salvos/of-flying-cars-and-the-declining-rate-of-profit

Graeber proposes that the growth of IT was part of a wider shift in research approaches. Research was once dominated by weirdos (e.g. Jack Parsons, Oppenheimer, etc) who operated with relatively little red tape. The rise of IT coincides with the rise of "managerialism," the McKinseyoid drive to monitor, quantify and – above all – discipline the workforce. IT made it easier to generate these records, which also made it normal to expect these records.

Before long, every employee – including the "creatives" whose ideas were credited with the productivity gains of the American century until the 70s – was spending a huge amount of time (sometimes the majority of their working days) filling in forms, documenting their work, and generally producing a legible account of their day's work. All this data gave rise to a ballooning class of managers, who colonized every kind of institution – not just corporations, but also universities and government agencies, which were structured to resemble corporations (down to referring to voters or students as "customers").

Even if you think all that record-keeping might be useful, there's no denying that the more time you spend documenting your work, the less time you have to do your work. The solution to this was inevitably more IT, sold as a way to make the record-keeping easier. But adding IT to a bureaucracy is like adding lanes to a highway: the easier it is to demand fine-grained record-keeping, the more record-keeping will be demanded of you.

But that's not all that IT did for the workplace. There are a couple areas in which IT absolutely increased the profitability of the companies that invested in it.

First, IT allowed corporations to outsource production to low-waged countries in the global south, usually places with worse labor protection, weaker environmental laws, and easily bribed regulators. It's really hard to produce things in factories thousands of miles away, or to oversee remote workers in another country. But IT makes it possible to annihilate distance, time zone gaps, and language barriers. Corporations that figured out how to use IT to fire workers at home and exploit workers and despoil the environment in distant lands thrived. Executives who oversaw these projects rose through the ranks. For example, Tim Cook became the CEO of Apple thanks to his successes in moving production out of the USA and into China.

https://archive.is/M17qq

Outsourcing provided a sugar high that compensated for declining productivity…for a while. But eventually, all the gains to be had from outsourcing were realized, and companies needed a new source of cheap gains. That's where "bossware" came in: the automation of workforce monitoring and discipline. Bossware made it possible to monitor workers at the finest-grained levels, measuring everything from keystrokes to eyeball movements.

What's more, the declining power of the American worker – a nice bonus of the project to fire huge numbers of workers and ship their jobs overseas, which made the remainder terrified of losing their jobs and thus willing to eat a rasher of shit and ask for seconds – meant that bossware could be used to tie wages to metrics. It's not just gig workers who don't score consistent five star ratings from app users whose pay gets docked – it's also creative workers whose Youtube and Tiktok wages are cut for violating rules that they aren't allowed to know, because that might help them break the rules without being detected and punished:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/13/solidarity-forever/#tech-unions

Bossware dominates workplaces from public schools to hospitals, restaurants to call centers, and extends to your home and car, if you're working from home (AKA "living at work") or driving for Uber or Amazon:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/02/chickenized-by-arise/#arise

In providing a pretense for stealing wages, IT can increase profits, even as it reduces productivity:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/11/robots-stole-my-jerb/#computer-says-no

One way to think about how this works is through the automation-theory metaphor of a "centaur" and a "reverse centaur." In automation circles, a "centaur" is someone who is assisted by an automation tool – for example, when your boss uses AI to monitor your eyeballs in order to find excuses to steal your wages, they are a centaur, a human head atop a machine body that does all the hard work, far in excess of any human's capacity.

A "reverse centaur" is a worker who acts as an assistant to an automation system. The worker who is ridden by an AI that monitors their eyeballs, bathroom breaks, and keystrokes is a reverse centaur, being used (and eventually, used up) by a machine to perform the tasks that the machine can't perform unassisted:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

But there's only so much work you can squeeze out of a human in this fashion before they are ruined for the job. Amazon's internal research reveals that the company has calculated that it ruins workers so quickly that it is in danger of using up every able-bodied worker in America:

https://www.vox.com/recode/23170900/leaked-amazon-memo-warehouses-hiring-shortage

Which explains the other major findings from the Upwork study:

81% of bosses have increased the demands they make on their workers over the past year; and

71% of workers are "burned out."

Bosses' answer to "AI making workers feel burned out" is the same as "IT-driven form-filling makes workers unproductive" – do more of the same, but go harder. Cisco has a new product that tries to detect when workers are about to snap after absorbing abuse from furious customers and then gives them a "Zen" moment in which they are showed a "soothing" photo of their family:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/ai-bringing-zen-first-horizons-192010166.html

This is just the latest in a series of increasingly sweaty and cruel "workplace wellness" technologies that spy on workers and try to help them "manage their stress," all of which have the (totally predictable) effect of increasing workplace stress:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/15/wellness-taylorism/#sick-of-spying

The only person who wouldn't predict that being closely monitored by an AI that snitches on you to your boss would increase your stress levels is your boss. Unfortunately for you, AI pitchmen know this, too, and they're more than happy to sell your boss the reverse-centaur automation tool that makes you want to die, and then sell your boss another automation tool that is supposed to restore your will to live.

The "productivity paradox" is being resolved before our eyes. American per-worker productivity fell because it was more profitable to ship American jobs to regulatory free-fire zones and exploit the resulting precarity to abuse the workers left onshore. Workers who resented this arrangement were condemned for having a shitty "work ethic" – even as the number of hours worked by the average US worker rose by 13% between 1976 and 2016:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/11/robots-stole-my-jerb/#computer-says-no

AI is just a successor gimmick at the terminal end of 40 years of increasing profits by taking them out of workers' hides rather than improving efficiency. That arrangement didn't come out of nowhere: it was a direct result of a Reagan-era theory of corporate power called "consumer welfare." Under the "consumer welfare" approach to antitrust, monopolies were encouraged, provided that they used their market power to lower wages and screw suppliers, while lowering costs to consumers.

"Consumer welfare" supposed that we could somehow separate our identities as "workers" from our identities as "shoppers" – that our stagnating wages and worsening conditions ceased mattering to us when we clocked out at 5PM (or, you know, 9PM) and bought a $0.99 Meal Deal at McDonald's whose low, low price was only possible because it was cooked by someone sleeping in their car and collecting food-stamps.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/jul/20/disneyland-workers-anaheim-california-authorize-strike

But we're reaching the end of the road for consumer welfare. Sure, your toddler-boss can be tricked into buying AI and firing half of your co-workers and demanding that the remainder use AI to do their jobs. But if AI can't do their jobs (it can't), no amount of demanding that you figure out how to make the Sea Monkeys act like they did in the comic-book ad is doing to make that work.

As screwing workers and suppliers produces fewer and fewer gains, companies are increasingly turning on their customers. It's not just that you're getting worse service from chatbots or the humans who are reverse-centaured into their workflow. You're also paying more for that, as algorithmic surveillance pricing uses automation to gouge you on prices in realtime:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/07/24/gouging-the-all-seeing-eye/#i-spy

This is – in the memorable phrase of David Dayen and Lindsay Owens, the "age of recoupment," in which companies end their practice of splitting the gains from suppressing labor with their customers:

https://prospect.org/economy/2024-06-03-age-of-recoupment/

It's a bet that the tolerance for monopolies made these companies too big to fail, and that means they're too big to jail, so they can cheat their customers as well as their workers.

AI may be a bet that your boss can be suckered into buying a chatbot that can't do your job, but investors are souring on that bet. Goldman Sachs, who once trumpeted AI as a multi-trillion dollar sector with unlimited growth, is now publishing reports describing how companies who buy AI can't figure out what to do with it:

https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/pages/gs-research/gen-ai-too-much-spend-too-little-benefit/report.pdf

Fine, investment banks are supposed to be a little conservative. But VCs? They're the ones with all the appetite for risk, right? Well, maybe so, but Sequoia Capital, a top-tier Silicon Valley VC, is also publicly questioning whether anyone will make AI investments pay off:

https://www.sequoiacap.com/article/ais-600b-question/

I can't tell you how great it was to take my kid down a grocery checkout aisle from which all the eye-level candy had been removed. Alas, I can't figure out how we keep the nation's executive toddlers from being dazzled by shiny AI pitches that leave us stuck with the consequences of their impulse purchases.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/07/25/accountability-sinks/#work-harder-not-smarter

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#productivity theater#upwork#ai#labor#automation#productivity#potemkin productivity#work harder not smarter#scholarship#bossware#reverse centaurs#accountability sinks#bullshit jobs#age of recoupment

463 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Trump’s Tax Scam: Why Nothing Trickled Down

The Trump tax cuts were a YUGE scam.

But this November we have a chance to end this trickle-down hoax once and for all.

Donald Trump’s biggest legislative achievement (if you want to even call it that) was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

The law permanently slashed corporate taxes and temporarily cut income tax rates mostly for rich individuals through the year 2025. The results were worse than I could have imagined.

Trump and his officials claimed the tax cuts would lead to corporations hiring more workers and would “very conservatively” lead to a $4,000 boost in household incomes.

What actually happened in the years since?

In AT&T’s case, the company saw its overall federal tax bill drop by 81%. It spent 31 times more on dividends and stock buybacks to enrich wealthy shareholders than it paid it in taxes. Meanwhile, it slashed over 40,000 jobs.

That was par for the course with Trump’s tax cuts.

Like AT&T, America’s biggest corporations didn’t use their tax savings to increase productivity or reward workers. Instead, they increased their stock buybacks and dividends.

Many of them, including AT&T, even ended up paying their executives more in some years than what they paid Uncle Sam.

Those executives (along with other high earners) then got to keep more of their earnings because Trump’s tax cuts for individuals were heavily skewed toward the rich. The lowest earners? They got squat.

And many middle-income families saw their taxes go up.

And those supposed $4,000 raises, did you get one?

The bottom line is that Trump’s tax law fueled a massive transfer of wealth into the hands of the rich and powerful. Corporate profits have skyrocketed. U.S. billionaire wealth has more than DOUBLED since 2018.

The tax cuts have also added $2 trillion to the national debt so far, but that hasn’t stopped Trump and the so-called “party of fiscal responsibility” from doubling down on renewing them.

If Trump is reelected and Republicans take control of Congress, they’re planning to renew the expiring tax cuts for individuals that primarily benefited the rich. This would cost $4.6 trillion over the next decade, more than double the cost of the original tax cuts.

Trump has also threatened to lower the corporate tax rate even further from 21% to 15% — which would cost another $1 trillion.

It’s trickle-down economics on steroids.

All of this would cause the federal deficit and debt to soar — which Republicans will then use as an excuse to cut spending on government programs the rest of us rely on.

But the Democrats have their own tax plan. We can make it a reality this November. What would it do? Just the opposite of Trump’s tax plan.

ONE: It would increase taxes on wealthy individuals with incomes in excess of $400,000 a year, while cutting taxes for lower-income Americans.

TWO: It would make billionaires pay at least 25 percent of their incomes in taxes, still leaving them with plenty left over.

THREE: It would raise the corporate income tax to 28 percent, which is about what it was in 1990.

LASTLY, it would quadruple the tax on stock buybacks to get corporations to invest more of their earnings in workers’ wages and productivity instead of windfalls for investors.

So the real choice is between the Republicans’ plan to make the rich much richer, and the Democrats’ plan to make the rich pay their fair share and provide what Americans need.

Which do you want?

344 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some highlights from the proposed bill for those interested:

Highest Personal Income Tax Rate Since 1986 (combined Federal Tax rate of 45%)

Highest Capital Gains Tax Since 1978. A rate over twice as high as China’s capital gains tax rate.(nearly doubles rate from 20% to 39%)

Corporate Tax Rate Higher than Communist China. (A 31% increase, from 21% to 28%)

Unconstitutional Wealth Tax on Unrealized Gains

Quadrupled Tax on Stock Buybacks. This tax will hit every American with a 401K or IRA or union pension.

$31 Billion Tax on American Energy

32% Increase to Medicare Taxes

Carried Interest Tax on Capital Gains

$23 Billion Retirement Tax

$24 Billion Cryptocurrency Tax

Real Estate Tax Hike (wants to end 1031 Like-Kind Exchanges)

Doubles the Global Minimum Tax (Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) from on U.S. multinational corporations from 10.5 to 21 percent, which after the disallowance of foreign tax credits would provide a top rate of 26.25 percent)

#Capitalism#Socialism#Politics#Anticapitalism#Antisocialism#Wage#Wage Gap#Eat the Rich#Minimum Wage#Living Wage#Affordable Education#Affordable Healthcare#Free Education#Free Healthcare#Student Loans#Accounting#Consulting#Business#Humor#Funny#Funny meme#Funny memes#Dark Humor#Office Humor#Excel#Economics#Keynesian Economics#Austrian Economics#Finance

818 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notable quotes from this article include:

"The strike – which marks the first time all three of the Detroit Three carmakers have been targeted by strikes at the same time – is being coordinated by UAW president Shawn Fain. He said he intended to launch a series of limited and targeted “standup” strikes to shut individual auto plants around the US." "They involve a combined 12,700 workers at the plants, which are critical to the production of some of the Detroit Three’s most profitable vehicles including the Ford Bronco, Jeep Wrangler and Chevrolet Colorado pickup truck."

"The UAW has a $825m strike fund that is set to compensate workers $500 a week while out on strike and could support all of its members for about three months. Staggering the strikes rather than having all 150,000 members walk out at once will allow the union to stretch those resources.

A limited strike could also reduce the potential economic damage economists and politicians fear would result from a widespread, lengthy shutdown of Detroit Three operations."

AND, THE BIG ONE: "Among the union’s demands are a 40% pay increase, an end to tiers, where some workers are paid at lower wage scales than others, and the restoration of concessions from previous contracts such as medical benefits for retirees, more paid time off and rights for workers affected by plant closures.

Workers have cited past concessions and the big three’s immense profits in arguing in favor of their demands. The automakers’ profits jumped 92% from 2013 to 2022, totaling $250bn. During this same time period, chief executive pay increased 40%, and nearly $66bn was paid out in stock dividends or stock buybacks to shareholders.

The industry is also set to receive record taxpayer incentives for transitioning to electric vehicles.

Despite these financial performances, hourly wages for workers have fallen 19.3%, with inflation taken into account, since 2008."

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Rich should pay their Wealth Tax, not just their income.

youtube

Stock Buybacks should be Illegal!

Pass protections for journalists before Trump takes office!

Urge Congress to block Trump’s plans to privatize the USPS!

Demand Change: It's Time to Fix Our Broken Healthcare System!

Block Donald Trump’s Attempts to Abolish the Department of Education!

Tell President Biden and Congress to halt all arms sales to Israel immediately!

Don't Abolish the Department of Education!

Your Year-End Gift to Beyond Plastics MATCHED Up to $50,000!

No Construction of the TMT Telescope on Mauna Kea!

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. must not be the next Secretary of Health and Human Services!

Toss Brawny for being a subsidiary of Koch Industries, one of the largest and most consistent direct funders of anti-choice and anti-LGBTQ+!

There's also an important petition addressing racial behavior concerns involving South African and Swiss authorities. Consider exploring platforms like Change.org for details.

#fuck elongated muskrat#fuck elon musk#fuck capitalism#tax the rich#eat the rich#youtube#youtube shorts#fuck donald trump#fuck trump#fuck jeff bezos#corporate greed#stock buybacks#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

BREAKING: Netflix Just Had Its Best Quarter Ever… So They’re Raising Prices!

Netflix just added 18.9 MILLION new subscribers in three months, made $10.25 BILLION in revenue, and their stock is soaring—yet instead of rewarding loyal customers, they’re hiking prices AGAIN.Meanwhile, workers everywhere are being told to "tighten their belts" while corporate execs pocket billions. And of course, Netflix approved a $15 BILLION stock buyback, because why invest in better wages, working conditions, or lower prices when they can just make shareholders richer?Late-stage capitalism is when a company makes record-breaking profits and somehow you still end up paying more.

https://www.barrons.com/articles/netflix-earnings-stock-price-b32bfbbe

#netflix#fuck netflix#boycott netflix#class war#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Close your eyes so you don’t notice this explanation of convertible bonds and the situation HYBE is in was written by a NJ fan 😂

When HYBE’s stock was priced at 350,000 won per share back in 2021, they issued convertible bonds (CBs) with a conversion price set at 110% of the stock price, which equals 385,000 won. Now, how can investors profit from this?

Let’s say I’m an investor and I bought 20B won worth of HYBE’s CBs, making me a bondholder. Here are the key terms of the CB:

1) Interest rates: Both the nominal interest rate (interest paid regularly) and the maturity interest rate (interest paid at the end of the bond’s term) are 0%. This means I don’t earn any interest while holding the bonds. My only opportunity to profit is if I convert the bonds into shares and the stock price increases.

2) Fixed conversion price: The conversion price is set at 385,000 won per share, and it remains fixed. Even if HYBE’s stock price drops significantly, I’m locked into this price—there are no adjustments.

3) Maturity and early redemption: The CBs mature in 5 years, in November 2026, but there’s an option for early redemption starting November 5.

How do I profit?

1) Waiting until maturity: If I wait until the bond matures and choose not to convert the CBs into shares, I won’t make any profit because there’s no interest. However, I also won’t lose money—assuming HYBE remains financially stable—because I’ll get my original 20B won back. The best-case scenario here is breaking even, while the worst-case scenario is if HYBE goes bankrupt, in which case I could lose everything.

2) Converting if the stock price rises: Let’s imagine I hold the bonds for 3 years, and by some miracle, HYBE’s stock price climbs to 500,000 won per share. Here’s where I can profit: I can convert my CBs into shares at the fixed price of 385,000 won per share and sell those shares at the higher market price of 500,000 won. With 20 billion won invested, I can convert the bonds into:

20,000,000,000 / 385,000 = 51,948

If I sell them at 500,000 won per share, my profit would be:

51,948 x (500,000−385,000) = 5,974,020,000 won

This results in a profit of 5.97B won, or a 29.87% ROI.

Right now, HYBE’s stock is well below 385,000 won, and given the controversies they’re facing, I see no clear reason for the stock price to recover to that level and higher anytime soon. Even though HYBE is attempting to boost the price through share buybacks, I’m doubtful they’ll succeed in pushing the stock high enough before 2026.

The risk is if I wait too long and HYBE’s financial situation worsens, they may not have enough cash to repay my original investment. In that case, I could be in serious trouble. So, considering the current conditions, the most sensible option is to redeem my bond early and recover my capital, rather than betting on an uncertain rise in the stock price. This way, I can use it on better investments.

What stands out now is that HYBE doesn’t have enough cash on hand to easily repay all these investors. As of June, the company had 298.15 billion won in cash, but they owe 324.3 billion won, leaving them with a shortfall. This puts HYBE in a difficult position, as they need to find a way to cover the gap. With their stock price low and their finances already under strain, the company faces a significant challenge in managing these repayments.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump blasts Biden on key issue impacting voters after damaging report: ‘Totally lost control’ | Fox News

GREEDFLATION! VIA FOXNEWS!

RAISE THESE MOFO'S TAXES AS THEIR PRICES RISE!. KEEP REMINDING THEM THAT THEY ARE SIGNALING THE END OF TAXPAYER FINANCED BAILOUTS! AND INSTEAD OF STOCK BUYBACKS THEY BETTER START SAVING FOR THE NEXT FINANCIAL CATASTROPHE!. END THEIR OFFSHORE TAX HIDEAWAYS! .

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not sure how you solve the whole "shareholder value maximization" thing. It seems fairly obvious that CEOs being very highly paid for overloading perfectly functional and profitable businesses with debt they can't really service long-term to pay for stock buybacks and pointless acquisitions is a bad thing on balance, but a good thing for everyone who gets to decide if it happens or not. You start with a functional productive enterprise and end with a yard sale, with the now shambling frankencompany being re-carved up and bought piecemeal by other companies still in the "fanatical acquisitions" stage of the process. At best you end up with consolidation/monopolization and displacement of profits onto the finance industry. But how do you stop it? Will it wither away as increased interest rates compel more judicious application of capital?

I do wish it were practical for workers at companies being liquidated due to inability to service debt to buy the company free of debt at a steep discount and run it as a cooperative. Realistically, this sort of resolution has only been remotely plausible in situations with sufficient political agitation (LIP type) or established union power and wealth. But in the case of unions, often the funds they have available are pension funds and such, and it's generally not great if they burn people's retirement trying to make a company doomed by macroeconomics beyond their control work, and presumably that would be the case at least some of the time.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friends,

I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling more anxious about the outcome of the upcoming election. I’m still nauseously optimistic, but the nausea is growing.

I’m as skeptical of polls as any of you, but when all of them show the same thing — that Kamala Harris’s campaign stalled several weeks ago, yet Trump’s continues to surge — it’s important to take the polls seriously.

Harris will give her closing message to the American people tomorrow at a rally on the National Mall’s Ellipse in Washington.

Over the last several weeks, she’s focused on Trump’s threats to a woman’s right over her body and to the rights of all Americans to a democracy.

Tomorrow night, though, she needs to respond forcefully to the one issue that continues to be highest on the minds of most Americans: the economy.

She must tell Americans simply and clearly why they continue to have such a hard time despite all the official economic indicators to the contrary: It’s because of the power of large corporations and a handful of wealthy individuals to siphon off most economic gains for themselves.

Most Americans are outraged that they continue to struggle economically at the same time billionaires are pulling in ever more wealth. Most know they’re paying too much for housing, gas, groceries, and the medicines they need. They also know that a major cause is the market power of big corporations.

They want someone who’ll stand up to big corporations and the politicians in Washington who serve them.

They want a president who’ll be on their side. A president who will crack down on price gouging, who will bust up the monopolies and restore competition, who will fight to cap prescription drug costs, who will get big money out of politics and stop the legalized bribery that rigs the market for the rich, and who will make sure corporations pay their fair share and end tax breaks for billionaire crooks.

A president who will put working families first — before big corporations and the wealthy.

Harris needs to say she will be this president.

Her policy proposals support this. She’s committed to strong antitrust enforcement — cracking down on mergers and acquisitions that give big food corporations the power to jack up food and grocery prices, prosecuting price-fixing, and banning price gouging. She needs to remind voters of this.

She also says she’ll raise taxes on the rich, provide $25,000 in down-payment assistance to help Americans buy their first home, restore the Expanded Child Tax Credit to $3,600 to help more than 100 million working Americans, and introduce a new $6,000 tax cut to help families pay for the high costs of a child’s first year of life.

All should be parts of her speech tomorrow about why she will be the champion of working people.

She wants to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, make stock buybacks more expensive, and expand Medicare to cover home health care — paid for with savings from the expansion of Medicare price negotiations with drug manufacturers.

She needs to frame all of this as a response to the power of big corporations and the wealthy — and say in no uncertain terms that she’s on the side of the people, not the powerful.

If she fails to do this in her closing argument, Trump’s demagogic response will be the only one the public hears — that average working people are struggling because of undocumented workers and the “enemy within,” including Democrats, socialists, Marxists, and the “deep state.”

Harris should fit her message about democracy inside this economic message. If our democracy weren’t dominated by the rich and big corporations, fewer of the economy’s gains would be siphoned off to them. Average working people would have better pay and more secure jobs and be able to afford to homes, food, fuel, medicine, child care, and eldercare.

A large portion of the public no longer thinks American democracy is working. According to a new New York Times/Siena College poll, only 45 percent believe our democracy does a good job representing ordinary people. An astounding 62 percent say the government is mostly working to benefit itself and elites rather than the common good.

In her closing argument, Harris should commit herself to reversing this, so government works for the common good.

Harris started her campaign in July and early August by emphasizing these themes about the economy and democracy.

But in more recent weeks, she’s focused mostly on Trump’s particular threat to democracy. Her campaign seems to have decided that she can draw additional voters from moderate Republican suburban women upset by Trump’s role in fomenting the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

That’s why she’s been campaigning with Liz Cheney and gathering Republican officials as supporters. And why she has chosen to give her closing message on the Ellipse — where Trump summoned his followers to march on the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Yet when she shifted gears from the economy to Trump’s attacks on democracy, Harris’s campaign stalled. I think that’s because Americans continue to focus on the economy and want an answer to why they are still struggling economically.

If Trump gives them an answer — although baseless and demagogic — but Harris does not, he may sail to victory on November 5.

Hence in her closing message she must talk clearly and frankly about the misallocation of economic power in America — lodged with big corporations and the wealthy instead of average Americans — and her commitment to rectify this.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Too big to care

I'm on tour with my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me in BOSTON with Randall "XKCD" Munroe (Apr 11), then PROVIDENCE (Apr 12), and beyond!

Remember the first time you used Google search? It was like magic. After years of progressively worsening search quality from Altavista and Yahoo, Google was literally stunning, a gateway to the very best things on the internet.

Today, Google has a 90% search market-share. They got it the hard way: they cheated. Google spends tens of billions of dollars on payola in order to ensure that they are the default search engine behind every search box you encounter on every device, every service and every website:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/03/not-feeling-lucky/#fundamental-laws-of-economics

Not coincidentally, Google's search is getting progressively, monotonically worse. It is a cesspool of botshit, spam, scams, and nonsense. Important resources that I never bothered to bookmark because I could find them with a quick Google search no longer show up in the first ten screens of results:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/21/im-feeling-unlucky/#not-up-to-the-task

Even after all that payola, Google is still absurdly profitable. They have so much money, they were able to do a $80 billion stock buyback. Just a few months later, Google fired 12,000 skilled technical workers. Essentially, Google is saying that they don't need to spend money on quality, because we're all locked into using Google search. It's cheaper to buy the default search box everywhere in the world than it is to make a product that is so good that even if we tried another search engine, we'd still prefer Google.

This is enshittification. Google is shifting value away from end users (searchers) and business customers (advertisers, publishers and merchants) to itself:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/05/the-map-is-not-the-territory/#apor-locksmith

And here's the thing: there are search engines out there that are so good that if you just try them, you'll get that same feeling you got the first time you tried Google.

When I was in Tucson last month on my book-tour for my new novel The Bezzle, I crashed with my pals Patrick and Teresa Nielsen Hayden. I've know them since I was a teenager (Patrick is my editor).

We were sitting in his living room on our laptops – just like old times! – and Patrick asked me if I'd tried Kagi, a new search-engine.

Teresa chimed in, extolling the advanced search features, the "lenses" that surfaced specific kinds of resources on the web.

I hadn't even heard of Kagi, but the Nielsen Haydens are among the most effective researchers I know – both in their professional editorial lives and in their many obsessive hobbies. If it was good enough for them…

I tried it. It was magic.

No, seriously. All those things Google couldn't find anymore? Top of the search pile. Queries that generated pages of spam in Google results? Fucking pristine on Kagi – the right answers, over and over again.

That was before I started playing with Kagi's lenses and other bells and whistles, which elevated the search experience from "magic" to sorcerous.

The catch is that Kagi costs money – after 100 queries, they want you to cough up $10/month ($14 for a couple or $20 for a family with up to six accounts, and some kid-specific features):

https://kagi.com/settings?p=billing_plan&plan=family

I immediately bought a family plan. I've been using it for a month. I've basically stopped using Google search altogether.

Kagi just let me get a lot more done, and I assumed that they were some kind of wildly capitalized startup that was running their own crawl and and their own data-centers. But this morning, I read Jason Koebler's 404 Media report on his own experiences using it:

https://www.404media.co/friendship-ended-with-google-now-kagi-is-my-best-friend/

Koebler's piece contained a key detail that I'd somehow missed:

When you search on Kagi, the service makes a series of “anonymized API calls to traditional search indexes like Google, Yandex, Mojeek, and Brave,” as well as a handful of other specialized search engines, Wikimedia Commons, Flickr, etc. Kagi then combines this with its own web index and news index (for news searches) to build the results pages that you see. So, essentially, you are getting some mix of Google search results combined with results from other indexes.

In other words: Kagi is a heavily customized, anonymized front-end to Google.

The implications of this are stunning. It means that Google's enshittified search-results are a choice. Those ad-strewn, sub-Altavista, spam-drowned search pages are a feature, not a bug. Google prefers those results to Kagi, because Google makes more money out of shit than they would out of delivering a good product:

https://www.theverge.com/2024/4/2/24117976/best-printer-2024-home-use-office-use-labels-school-homework

No wonder Google spends a whole-ass Twitter every year to make sure you never try a rival search engine. Bottom line: they ran the numbers and figured out their most profitable course of action is to enshittify their flagship product and bribe their "competitors" like Apple and Samsung so that you never try another search engine and have another one of those magic moments that sent all those Jeeves-askin' Yahooers to Google a quarter-century ago.

One of my favorite TV comedy bits is Lily Tomlin as Ernestine the AT&T operator; Tomlin would do these pitches for the Bell System and end every ad with "We don't care. We don't have to. We're the phone company":

https://snltranscripts.jt.org/76/76aphonecompany.phtml

Speaking of TV comedy: this week saw FTC chair Lina Khan appear on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. It was amazing:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaDTiWaYfcM

The coverage of Khan's appearance has focused on Stewart's revelation that when he was doing a show on Apple TV, the company prohibited him from interviewing her (presumably because of her hostility to tech monopolies):

https://www.thebignewsletter.com/p/apple-got-caught-censoring-its-own

But for me, the big moment came when Khan described tech monopolists as "too big to care."

What a phrase!

Since the subprime crisis, we're all familiar with businesses being "too big to fail" and "too big to jail." But "too big to care?" Oof, that got me right in the feels.

Because that's what it feels like to use enshittified Google. That's what it feels like to discover that Kagi – the good search engine – is mostly Google with the weights adjusted to serve users, not shareholders.

Google used to care. They cared because they were worried about competitors and regulators. They cared because their workers made them care:

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/4/4/18295933/google-cancels-ai-ethics-board

Google doesn't care anymore. They don't have to. They're the search company.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/04/teach-me-how-to-shruggie/#kagi

#pluralistic#john stewart#the daily show#apple#monopoly#lina khan#ftc#too big to fail#too big to jail#monopolism#trustbusting#antitrust#search#enshittification#kagi#google

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

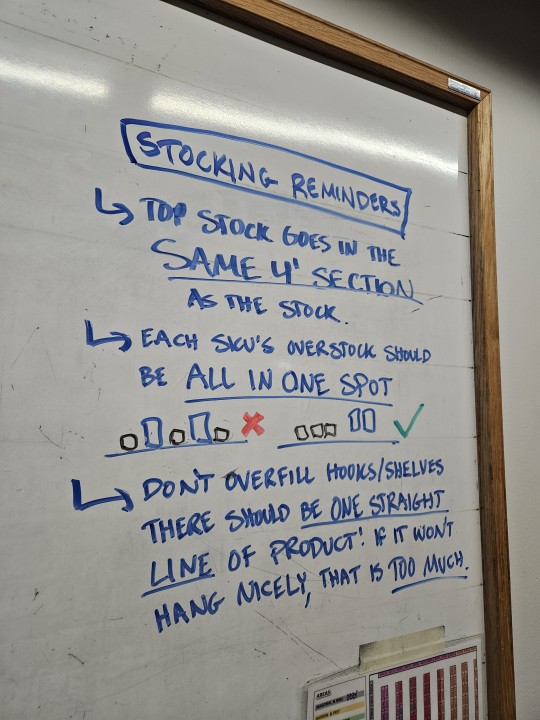

ID. photo of a whiteboard with bullet points written on it, titled "Stocking Reminders."

Top stock goes in the same 4' section as the stock.

Each SKU's overstock should be all in one spot. (below this point there is a diagram of a shelf with colorcoded boxes, one mixed up and one with the colors together)

Don't overfill hooks/shelves. There should be one straight line of product! If it won't hang nicely that is too much.

End ID.

end of my fucking rope tuesday. this won't stop my coworkers because they can't read but the amount of topstock i found in fucking random aisles today was truly absurd. like we've graduated from putting it in the same aisle 16ft away on the opposite side (annoying but at least line of sight) to putting it in topstock in its unlabeled cardboard shipping box, three aisles away, in a different department.

other highlights of today:

i asked this kid to downstock One Aisle and he spent 3(?) hours standing over there doing, as far as i can tell, nothing. which dgmw i can respect. minimum wage => minimum effort but my man that wasn't even CLOSE to the minimum and you are actively making everyone else's lives more difficult!!!

hardware mgr tried to have someone else (the aforementioned kid who can't even put stock in the right spot!!!) do counts on stock, BEHIND MY BACK, AGAIN. so i started off the day with an argument with him. bc if im not shooting outs regularly enough for you fucking TALK TO ME. and i will tell you what i need, which is you to do your fucking JOB and MANAGE YOUR PEOPLE. and get on their asses to actually maintain their sections!!! i could do the whole fucking store in an hour if literally anyone else did their jobs!!!

got a new rope assortment in from a new vendor, hardware mgr packed up the old stuff for buyback but ALSO managed to pack up a bunch of the NEW stuff with it despite the packaging being a completely different color AND saying the new brand name, so i had to go digging in 15 different taped-shut boxes to find it back.

just some truly atrocious and annoying customers. girl if youre in a hurry that is YOUR problem for not planning. i cant read your mind and i cant give you an answer if you cant explain your problem to me.

got called "ladies" collectively about 8 times today by my coworker who a) does ABA as his other job b) asked me if ozzy was my "real name" and c) said he used to be a liberal but he thinks there are more important things than peoples' identities. we're mostly copacetic now though bc he sees how much work i do and also we've commiserated about the state of the educational system & when he was talking about how "boys and girls learn differently" i very lightly floated the "well, i don't think that's inherent necessarily, you know, like we're raised and taught certain ways to be from SUCH a young age, and kids pick up on stuff pretty fast," and he was like huh ive never thought about that. ill have to think about that. so not unsalvageable! just a particular Kind Of Guy.

they're doing work on the roof and they fucking broke the ancient drainpipe that runs through our upstairs backstock area, so theres like three totes worth of roof-water-soaked merchandise that i have to take out of inventory tomorrow. and everything else in that backstock area has a fine coating of rust flakes from the disintegrating ceiling. and i was paged up there to help sort thru the stock and like. there are THREE PEOPLE here today who actually have a manager title, which I DONT!!! so why cant the three of you take care of it!!! and i KNOW its bc im good at problem-solving and don't really say no and would do it faster than anyone else but god. come on. its putting wet stock in totes.

also in the last 30 min of my shift (in the hardware dept!!! doing inventory counts!!!) my coworker walkied Me, Specifically, even though i knowww they were fully staffed in cashiers and housewares today, to pick up a call from a specific problem customer ABOUT A HOUSEWARES PRODUCT. bro i know FULL WELL you are doing fucking nothing but online shopping on the work computer, you fucking handle it!!! im on a DIFFERENT FLOOR and im busy doing other shit!!!

and its only tuesday!!! yippee!!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’re already signed up, great! If you’d like to sign up and receive issues over email, you can do so here.

Today, as the U.S. is drawn into wars in Israel and Ukraine, as well as the defense of now-peaceful Taiwan, I’m writing about war. Not the policy choices, or whether U.S. military power is a net force for good or ill, but the actual practical machinery behind the American defense base that produces the weaponry necessary to sustain the military.

As stockpiles dwindle, there is now widespread agreement among policymakers that America must rebuild its capacity to arm itself and its allies. But according to a new scorching government report released this week, that’s mostly just talk. The Pentagon doesn’t bother tracking the guts of defense contracting, which is who owns the mighty firms that build weaponry.

But first, I have a personal announcement. I am going on leave this week, and I’ve hired a colleague named Lee Hepner to take over for BIG while I am out. You are in for a treat. Hepner works with me at the American Economic Liberties Project. He’s a lawyer with over a decade's worth of policy and political experience at the state and local level, and when I have a question on the law or procedure, Hepner’s one of my go-to people. He’s drafted important legislation, and has recently been focusing on the airline industry, labor issues, and a lot of the major antitrust litigation I've written about here, including the trials of the Meta-Within merger, the Microsoft-Activision acquisition and the Google monopolization case. You're in good hands.

And now, let’s talk the defense base. Here’s an exceptionally boring chart that involves all the money in the world. Welcome to the Pentagon.

One of the more important side stories to the recent wars in Ukraine and Israel, and competition with China over Taiwan, is that the U.S. defense industrial base, composed of 200k plus corporations, is being forced to actually build weapons again. Defense is big business, and since the end of the Cold War, the government has allowed Wall Street to determine who owns, builds, and profits from defense spending.

The consequences, as with much of our economic machinery, are predictable. Higher prices, worse quality, lower output. Wall Street and private equity firms prioritize cash out first, and that means a once functioning and nimble industrial base now produces more grift than anything else. As Lucas Kunce and I wrote for the American Conservative in 2019, the U.S. simply can’t build or get the equipment it needs. There are at this point a bevy of interesting reports coming out of the Pentagon. The last one I wrote up earlier this year showed that unlike the mid-20th century defense-industrial base, today government cash goes increasingly to stock buybacks rather than actual armaments. And now, with a dramatic upsurge in need for everything from missiles to artillery shells to bullets, we’re starting to see cracks in the vaunted U.S. military.

The signs are unmistakable. In Ukraine, fighters are rationing shells. Taiwan can’t get weapons it ordered years ago. The Pentagon has put together a secret team to scour stockpiles to find high-precision armaments in demand on every battlefield and potential battlefield. But the problem goes beyond national defense. In Lake City, Missouri, the largest small arms ammunition plant in the world has decided all ammo production is going to the military, meaning that there is going to be a domestic shortage for hunters, sportsmen, and maybe even police. This shortage may look like a story of a sudden surge in demand, but it’s actually, as Elle Ekman wrote in the Prospect in 2021, a story of consolidation and de-industrialization.

Surges due to wars aren’t new, and there’s always some time lag between the build-up and the delivery. But today, the lengths of time are weirdly long. For instance, the Army is awarding contracts to RTX and Lockheed Martin to build new Stinger missiles, which makes sense. But the process will take.. five years. Why? What is new is Wall Street’s role in weaponry. We used to have slack, and productive capacity, but then came private equity and mergers. And now we don’t. The government can’t actually solicit bids from multiple players for most major weapons systems, because there’s just one or two possible bidders. So that means there’s little incentive for firms to expand output, even if there’s more spending. Why not just raise price?

But don’t take my word for it, take that of the Pentagon. In 2022, the DOD reported that “that consolidation of the industrial base reduces competition for DOD contracts and leads DOD to rely on a more limited number of suppliers. This lack of competition may in turn increase the risk of supply chain gaps, price increases, reduced innovation, and other adverse effects.” And that’s why, more than a year into the Ukraine conflict, the ramp-up is still not where it needs to be.

This week, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which is a Congressional office charged with investigating problems in government and business, explained why. The GAO came out with a report on how the Pentagon is doing essentially zero oversight of Wall Street’s acquisitions of defense contractors. The title is as boring as you’d expect, designed to have few people pay attention, but offering a red-alert to procurement officials.

The report is simply jaw-dropping. Despite all the chatter about consolidation at high levels within the Pentagon, and in Congress, the bureaucracy has made essentially no progress whatsoever. For instance, we have a trillion dollar defense budget, but there are just two people in the Department of Defense who look at mergers in the defense base. You couldn’t staff the morning shift of a small coffee shop with that, and yet two people are supposed to look at the estimated four hundred mergers plus going on every year among defense contractors and subcontractors.

Four hundred mergers every year is a lot, but of course, that’s just an estimate. Why don’t we know how many acquisitions happen in the defense base? As it turns out, it’s an estimate because the Pentagon isn’t tracking defense mergers anymore. To put it in boring GAO-speak, Pentagon“officials could not say with certainty how many defense-related M&A now occur annually because they no longer track or maintain data on all M&A in the defense industrial base.” So the DOD is almost totally blind to the corporate owners of contractors and subcontractors, which might be one reason that, say, Chinese alloys are being discovered in sensitive weapons systems like the state of the art F-35.

It gets worse. There’s no policy or guidance on mergers, and DOD doesn’t even require contractors or subcontractors to tell them that there is new ownership when an acquisition occurs. In fact, the Pentagon relies on public news to learn of mergers. They often do not know that the mergers are going on, or that the Federal Trade Commission is reviewing them. When big mergers happen, even if the Pentagon is concerned, no one tracks what happens after it closes. They do no analysis of industry sectors, as their “M&A office is not collecting robust data or conducting recurring trend analyses that could help them identify M&A in risky areas of consolidation among defense suppliers.”

The Pentagon’s head-in-the-sand approach is why Lockheed now has a chokehold on nuclear missile modernization, since it bought the key supplier of rocket engines and denies those engines to rivals bidding for the contract to upgrade what is known as the nuclear triad.

So how does the U.S. government manage defense base mergers? Well, the Pentagon defers to the antitrust agencies to look solely at competition. “While DOD policy directs Industrial Base Policy and DOD stakeholders to assess other types of risks, such as national security and innovation risks,” wrote the GAO, “they have not routinely done so.” Basically, dealing with their own defense base is someone else’s job.

What I found most useful about the GAO report is the Pentagon’s response, a classic bureaucratic hand wave. The DOD agreed with all the conclusions of the GAO. It should track mergers and what happens afterwards, it should have more personnel doing so, it should consider national security aspects of corporate combinations, and it should have clear policy on mergers. But it doesn’t. The DOD says it will have a better strategy to deal with mergers… by 2024. Basically, you’re right, but it’s not our problem.

Every day, it seems like political leaders and consultants are saying it’s time to really get that arsenal of democracy going, and to re-industrialize for real. It’s quite possible to get a lot done. The FTC and DOJ now have significant amounts of national security-related information on mergers due to a Congressional change in pre-merger notification laws in 2022, so the DOD could easily do a better job of tracking what’s happening in the defense base.

More to the point, the Pentagon is very powerful. The Deputy Secretary of Defense, Kathleen Hicks could simply start smashing heads on competition and begin telling contractors that if they don’t shape up, she will start an internal war against them. Or the head of the Armed Services Committees could threaten the cushy cash flow that leads to record stock buybacks among contractors, if the ramp-up doesn’t start. Or they could grant antitrust authority for the DOD straight-up, which would rely on a national security standard that allows widespread corporate restructuring without the long slog of a court case. There are many paths.

But if you actually look at the guts of the bureaucracy, nothing is happening, because doing something about our industrial base means thwarting Wall Street, and that’s generally not something that’s considered on the table among normie policymakers. Giant bureaucracies are hard to change, but they are not immovable. One of the ways that you know a previously non-functional bureaucracy is on the right track is, ironically, if there is bitter infighting and anger among staff, who are being tasked to do things differently. But as the GAO showed this week, that’s just not happening in the Pentagon, or at least, not happening nearly fast enough.

And that’s why America is increasingly out of ammunition.

#military industrial complex#us military#nato#ukraine#israel#capitalism#economics#wall street#finance capitalism#finance capital#lockheed martin

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Expiration Date Capitalism

I think capitalist endeavors should have an expiration date, or other means of phasing it out for each individual situation.

Like, we let patents expire even though the person who invented a thing literally *invented* a new thing, and spent who knows how much time, money, and knowledge to create it.

Why can’t capitalist stakes in businesses do the same? E.g. After 20 years, there’s no more investor return. The business then runs for itself and its workers. (So if the guy who made the company is still running, he’ll still earn a good *wage* but not a *profit*.)

Or perhaps letting things expire after they’ve provided a certain return on investment. E.g. After a company’s stocks have returned 10x their original value (adjusting for inflation), the stocks die and the company just runs for itself, focusing on efficiency and wages, not whatever crazy shortcuts or buybacks investors want to do to make some more cash out of it, in perpetuity (esp when a lot of the “innovations” are just new ways to screw employees and customers).

The company can decide to issue *new* stocks for investors to invest in, but the old stocks or ownership rights won’t last forever. Just because you built a popular coffee shop or grocery store, doesn’t mean you get to monopolize its success till the end of time. Get rewarded for your investment; get rewarded for your work, but then let the money go where it should: the business, to quality products and services, and to the laborers who provide it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bitcoin Is Now Above $29K

Bitcoin has pushed above $29,000 following the U.S. Federal Reserve’s 25 basis point interest rate hike on Thursday, with some analysts speculating on a strong break to the upside after over a month of trade in a narrow wedge. The move over $29,000 came a few hours after the Fed hike as a report indicated another U.S. bank failure could soon be at hand. Crypto services provider Matrixport has said that if Thursday’s rate rise proves to be the last of this cycle, bitcoin could rally 20% to $36,000. Despite trading volumes declining slightly, the “path higher sees only limited resistance,” Matrixport said in a research note on Thursday. The end of the recent earning season will see stock buybacks restart, which will “continue to be a tailwind for stocks and risk assets,” the note added.

https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2023/05/04/first-mover-americas-bitcoin-ending-week-on-positive-note/?outputType=amp

7 notes

·

View notes