#eliza-williams-1922

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

"Annie Liggett Bryner, sister of George, Carrie, Laura, and Emma," 1886 by Ann Longmore-Etheridge Via Flickr: Annie Liggett was born in Saville Township, Perry Co., Pennsylvania in December 1859 to Samuel (1811-1889) and Anne Milligan Liggett (1821-1888). The couple had married on April 28, 1846. Her elder sister Laura Jane was born in 1849; brother George Alfred had been born in 1852; sister Emma Ada had been born in March 1856; Carrie Eleanor was born in 1862. On the 1870 census, Annie can be found living her father who is the 59-year-old proprietor of an iron factory; her mother, Laura, Emma, and Carrie, as well as 18-year-old George, who works in the foundry. According to the book "The History of Perry Country," 1922, by Harry H. Hain, this was Clinton Foundry, which Liggett had built and owned. Laura Liggett married William Flickinger in November 1876. She died in 1933. By 1880, George--now an engineer, presumably at Clinton Foundry--has married a woman named Leah and moved out to start his own family of two daughters and 2 sons, but he hasn't strayed far, living right next door to his parents. (As late as 1910, George is living in Perry Country with his wife, several of his daughters and grandchildren.) Annie married Dr. Newton E. Bryner on October 14, 1886. He seems to have come into the area to replace the previous local physician. The above cabinet card was probably taken at the time of their marriage. Unfortunately, Newton, a graduate in medicine of the University of New York, was dead in less than a year. He passed in April 1887 at Cisna Run (his father's farm), Perry Co., PA. (Note: there seems to be some confusion amongst the Liggett siblings. There may have been another daughter--or the daughter of another Perry County family--named Anna Eliza who was born in 1859 and died in 1877. If this is the case, she was not the woman who marred Newton Brynner in 1886, clearly, as this photo and subsequent census listings bear out. There is also confusion about the death date of Dr. Bryner with some sources giving it as 1877. His alma mater, the University of New York, clearly states in its roster of graduates that Bryner died in 1887.) Annie appears on the 1900 census for Saville Township, Perry Co., as a 40-year-old widow living with Emma Liggett Scott, her 44-year-old sister, who lists her occupation as a farmer who has been married for one year. No husband appears to live in house. The situation had not changed 10 years later, when on the 1910 census, both sisters are still living together and living on their own income. This was derived, presumably, by Emma's ownership of her father's foundry, which is noted in the Haim history. By 1920, the husband had returned: he is 55-year-old James W. Scott, who is a decade younger than his wife. All of them appear to be living on their own incomes. Annie Liggett Bryner in 1927. "Hector Kraus, 408 Market Street, Harrisburg, PA" Albumin print cabinet card.

#portrait#victorian#1880s#cabinet card#liggett#bryner#pennsylvania#perry#saville#carte de visite#CDV#vintage#19th century#albumen#carte de vistie#nineteenth century#early photography#cabinet#card#carte#de#visite#early photogrpahy#fashion#geneaology#history#Ann#Longmore-Etheridge#Collection#flickr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Starter for @eliza-williams-1922 !)

Clemcy woke to the scent of blood and motor oil, the sound of heavy wind through trees, and a ringing headache that made the other sensations faintly nauseating. He shifted, squinting around.

Well. Judging by the absolutely crumpled vehicle around him, this was the aftermath of a car crash. And judging by the too-bright, dreamlike feel to the world and the cold ache of magic depletion settled deep into his soul, his body had died in said crash and was only just now reviving.

Wonderful. He let his eyes slide closed again and waited for the ringing in his ears to fade.

—

One minute later, Clemcy remembered why he crashed and was galvanized back into motion. He retrieved what belongings he could find within the crumpled carcass of the car, including his now-battered briefcase, and staggered his way far enough into the woods to escape the sight of anyone looking out from the road.

Ten minutes after sinking down with his back against a tree, Clemcy had determined that his laptop was now unresponsive beyond his ability to recover with the (lack of) resources he had to hand. Which meant that he was unable to easily contact the rest of himself.

A brief telepathic search allowed him to locate the nearest settlement. Five minutes and a few minor cleaning spells later, he and his clothing were no longer coated in blood and he looked at least vaguely presentable.

One teleportation spell and a subsequent blackout of indeterminate length brought Clemcy to the outskirts of the settlement, which proved to be a small rural town. He spotted a gas station sign and made his way towards it.

—

“I don’t suppose that you know somewhere in town that might have computer repair supplies?” Clemcy asked the gas station cashier as he pushed a small collection of food, drinks, and pain medication towards the register. He tried for a self-deprecating smile, but suspected that his tension showed through. “Someone with a computer of their own and who might have a set of precision screwdrivers that I could borrow, for example. I’m in a bit of a hurry.”

#long post#(and off we go!)#eliza-williams-1922#Clemcy#the Necromancer is in#Eliza#rp#eliza williams 1922#thread: a few restorations

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

@eliza-williams-1922 liked THIS for a starter...

‘Lisa, if I don’t make it out of this place, take these fuckers DOWN. The things they are doing here... Lisa. I love you.’

It had become something like a prayer. Words said over and over again as though the software engineer could transmit his thoughts to his wife. As though thinking them loud enough would protect him from what was happening here. Would protect Lisa and the boys from whatever Murkoff decided to do to keep it all silent.

He was running. When wasn’t he running? Running from noises and prisoners and doctors and static. How was he running from static? Running blindly through halls he didn’t know the path of using a camera for light half the time. Slammed into a room and closed the door, leaning back against it with a sob of exhaustion. Unaware of anyone else in the room for the time being.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ithadel has left his journal open on the table beside Eliza’s cot. The most recent page contains notes documenting Eliza’s injuries and survival, but one corner of the previous page contains a small, colored ink sketch.

(In response to this ask meme! Though @eliza-williams-1922 actually sent the ask to my other blog, I wanted to do a response from Ithadel as well as Linast. :) I referenced the illustration itself from this photograph.)

#(Cropped in close because I did indeed just draw this in my own journal)#(and I'm so used to writing freely in it that I jotted down a bunch of unrelated notes right around it without thinking hah)#Ithadel#Eliza#Eliza Williams 1922#eliza-williams-1922#unpleasant circumstances thread#art#my art#traditional art#art: Ithadel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@eliza-williams-1922 answered from HERE:

Eliza smiles reassuringly at the boy, “I can understand that. They are kinda spooky at this time of day.”

“How did you get out here all by yourself?”

He’d run away from home. His little plastic toy knife clutched tightly in one hand while the other fiddled with the ribbon around his neck. After a moment of guilty contemplation, he tucked the toy into a pocket to sign.

“I’m running away. And no one will ever find me in the woods. But they’re creepier than I thought.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have a favorite characteristic of your muse(s)? are there any plots on your wishlist?

saltly and sweet: an ooc ask meme - Open - Any Verse

1. Izadia is an incredibly happy, friendly person, and playing her often makes me feel better. Like me she also has anxiety, but she just tries to brighten the world by being in it

2. Not super specifically, no. I struggle a lot to write rp specific plots rather than dnd plots that have direct goals. I want to do some stuff around her pregnancy, maybe. I might want a thread with an actual angel mun.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merc, despite not knowing how to cook, enjoyed shopping for food.

Stores that were open at all hours of the day tended to have a far wider selection of snacks and foodstuff that Rasul barely trusted her to make in the microwave, and so these became part of her nightly routine when she wasn’t elbows deep in a project.

The snack she wanted was on the top shelf, however, and there was a person already standing in front of the shelf. Merc was usually a patient type, but this person was so short, and she was right there-

“Head’s up,” she told the lady simply, reaching right over her head and leaning into her space to grab the proper bag of flavored carbs she craved.

@eliza-williams-1922

#eliza-williams-1922#this took AGES i am sorry#i hope this okay!#merc just. really wanted them chips

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

⅀?

Send me a ⅀ and I’ll explain one of my characters’ backstories really badly

Girl discovers she’s immortal. Spends the next 60 years moping about it before attempting to get her shit together.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some casual outfits for Eliza @eliza-williams-1922

Made With: Azalea’s Casual Style Dress up

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Visibly Strange (closed)

@eliza-williams-1922

Ash’s nose crinkled in the direction of the stranger, taking a step towards her. She didn’t expect to find another supernatural being while she was in town and this one- well she didn’t smell of anything familiar, but she wasn’t human either.

The wolf knew not to simply ask someone what they were, that’s just plain rude. As she continued her approach, she forced her ears to droop slightly, slouching to be a little smaller, all to aware of how rough and intimidating she tended to be. She just hoped that being visibly non-human would be enough to get the other comfortable enough to out herself.

“Uh. Hi.” she had spent too much time thinking about her posture that she forgot to think of something to say, “This is weird but. I’m Ash. And you seem interesting. So I’m talking to you now.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Username change: eliza-williams-1922 to zodiac--muses

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Miss Eliza Wedgwood and Miss Sargent Sketching, John Singer Sargent, 1908, Tate

Bequeathed by William Newall 1922 Size: support: 502 x 356 mm frame: 693 x 546 x 20 mm Medium: Watercolour and gouache on paper

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sargent-miss-eliza-wedgwood-and-miss-sargent-sketching-n03658

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More than a year after meeting Linast, Eliza finds an unaddressed envelope slid under her door. It contains a sealed oil pastel illustration. On the back of the paper is a note written in large, somewhat uneven handwriting that reads:

Eliza --

I wanted to say thank you for helping me. It took a long time, but I’ve gotten back home to my sibling again. I might not have made it this far without you.

-- Linast

(For @eliza-williams-1922 in response to this ask meme! With reference to our An Unusual Morning thread.)

#(written while Linast is still recovering from the whole human incident)#(he probably does try to visit her in person again. just... later. he was pretty unstable for a long time after returning.)#(once again it's been a long while since I've touched oil pastels. I'm not the best with them but they are fun!)#rp#art#Linast#Eliza#(An Unusual Morning)#Eliza Williams 1922#eliza-williams-1922#(ic art: Linast)#illustrated answers#my art#art: Linast

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

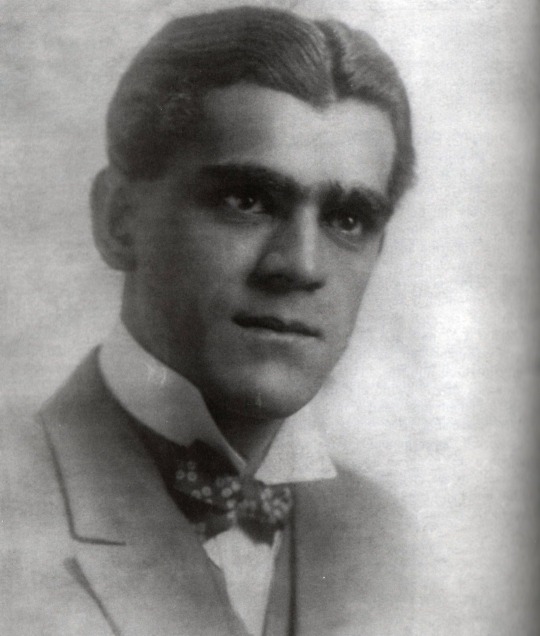

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff was an English actor who was primarily known for his roles in horror films. He portrayed Frankenstein's monster in Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939). He also appeared as Imhotep in The Mummy (1932).

In non-horror roles, he is best known to modern audiences for narrating and as the voice of the Grinch in the animated television special of Dr. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966). For his contribution to film and television, Karloff was awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Karloff was born William Henry Pratt on 23 November 1887,[2] at 36 Forest Hill Road, Dulwich, Surrey (now London), England. His parents were Edward John Pratt, Jr. and Eliza Sarah Millard. His brother, Sir John Thomas Pratt, was a British diplomat. Edward John Pratt, Jr. was an Anglo-Indian, from a British father and Indian mother, while Karloff's mother also had some Indian ancestry, thus Karloff had a relatively dark complexion that differed from his peers at the time. His mother's maternal aunt was Anna Leonowens, whose tales about life in the royal court of Siam (now Thailand) were the basis of the musical The King and I. Pratt was bow-legged, had a lisp, and stuttered as a young boy.[7] He learned how to manage his stutter, but not his lisp, which was noticeable throughout his career in the film industry.

Pratt spent his childhood years in Enfield, in the County of Middlesex. He was the youngest of nine children, and following his mother's death was brought up by his elder siblings. He received his early education at Enfield Grammar School, and later at the public schools of Uppingham School and Merchant Taylors' School. After this, he attended King's College London where he took studies aimed at a career with the British Government's Consular Service. However, in 1909, he left university without graduating and drifted, departing England for Canada, where he worked as a farm labourer and did various odd itinerant jobs until happening upon acting.

Pratt began appearing in theatrical performances in Canada, and during this period he chose Boris Karloff as his stage name. Some have theorised that he took the stage name from a mad scientist character in the novel The Drums of Jeopardy called "Boris Karlov". However, the novel was not published until 1920, at least eight years after Karloff had been using the name on stage and in silent films, opening the possibility that the Karlov character might have been named after Karloff after the novel's author noticed it in a cast listing and liked the sound of it rather than simply being a coincidence. Warner Oland played "Boris Karlov" in a film version in 1931. Another possible influence was thought to be a character in the Edgar Rice Burroughs fantasy novel H. R. H. The Rider which features a "Prince Boris of Karlova", but as the novel was not published until 1915, the influence may be backward, that Burroughs saw Karloff in a play and adapted the name for the character. Karloff always claimed he chose the first name "Boris" because it sounded foreign and exotic, and that "Karloff" was a family name (from Karlov—in Cyrillic, Карлов—a name found in several Slavic countries, including Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria).

Karloff's daughter, Sara, publicly denied any knowledge of Slavic forebears, "Karloff" or otherwise. One reason for the name change was to prevent embarrassment to his family. Whether or not his brothers (all dignified members of the British Foreign Service) actually considered young William the "black sheep of the family" for having become an actor, Karloff apparently worried they felt that way. He did not reunite with his family until he returned to Britain to make The Ghoul (1933), extremely worried that his siblings would disapprove of his new, macabre claim to world fame. Instead, his brothers jostled for position around him and happily posed for publicity photographs. After the photo was taken, Karloff's brothers immediately started asking about getting a copy of their own. The story of the photo became one of Karloff's favorites.

Karloff joined the Jeanne Russell Company in 1911 and performed in towns like Kamloops (British Columbia) and Prince Albert (Saskatchewan). After the devastating tornado in Regina on 30 June 1912, Karloff and other performers helped with clean-up efforts. He later took a job as a railway baggage handler and joined the Harry St. Clair Co. that performed in Minot, North Dakota, for a year in an opera house above a hardware store.

Whilst he was trying to establish his acting career, Karloff had to perform years of manual labour in Canada and the U.S. in order to make ends meet. He was left with back problems from which he suffered for the rest of his life. Because of his health, he did not enlist in World War I.

During this period, Karloff worked in various theatrical stock companies across the U.S. to hone his acting skills. Some acting companies mentioned were the Harry St. Clair Players and the Billie Bennett Touring Company. By early 1918 he was working with the Maud Amber Players in Vallejo, California, but because of the Spanish Flu outbreak in the San Francisco area and the fear of infection, the troupe was disbanded. He was able to find work with the Haggerty Repertory for a while (according to the 1973 obituary of Joseph Paul Haggerty, he and Boris Karloff remained lifelong friends). According to Karloff, in his first film he appeared as an extra in a crowd scene for a Frank Borzage picture at Universal for which he received $5; the title of this film has never been traced.

Once Karloff arrived in Hollywood, he made dozens of silent films, but this work was sporadic, and he often had to take up manual labour such as digging ditches or delivering construction plaster to earn a living.

His first on screen role was in a film serial, The Lightning Raider (1919) with Pearl White. He was in another serial, The Masked Rider (1919), the first of his appearances to survive.

Karloff could also be seen in His Majesty, the American (1919) with Douglas Fairbanks, The Prince and Betty (1919), The Deadlier Sex (1920), and The Courage of Marge O'Doone (1920). He played an Indian in The Last of the Mohicans (1920) and he would often be cast as an Arab or Indian in his early films.

Karloff's first major role came in a film serial, The Hope Diamond Mystery (1920). He was Indian in Without Benefit of Clergy (1921) and an Arab in Cheated Hearts (1921) and villainous in The Cave Girl (1921). He was a maharajah in The Man from Downing Street (1922), a Nabob in The Infidel (1922) and had roles in The Altar Stairs (1922), Omar the Tentmaker (1922) (as an Imam), The Woman Conquers (1922), The Gentleman from America (1923), The Prisoner (1923) and the serial Riders of the Plains (1923).

Karloff did a Western, The Hellion (1923), and a drama, Dynamite Dan (1924). He could be seen in Parisian Nights (1925), Forbidden Cargo (1925), The Prairie Wife (1925) and the serial Perils of the Wild (1925).

Karloff went back to bit part status in Never the Twain Shall Meet (1925) directed by Maurice Tourneur but he had a good support role in Lady Robinhood (1925).

Karloff went on to be in The Greater Glory (1926), Her Honor, the Governor (1926), The Bells (1926) (as a mesmerist), The Nickel-Hopper (1926), The Golden Web (1926), The Eagle of the Sea (1926), Flames (1926), Old Ironsides (1926), Flaming Fury (1926), Valencia (1926), The Man in the Saddle (1926), Tarzan and the Golden Lion (1927) (as an African), Let It Rain (1927), The Meddlin' Stranger (1927), The Princess from Hoboken (1927), The Phantom Buster (1927), and Soft Cushions (1927).

Karloff had roles in Two Arabian Knights (1927), The Love Mart (1927), The Vanishing Rider (1928) (a serial), Burning the Wind (1928), Vultures of the Sea (1928), and The Little Wild Girl (1928).

He was in The Devil's Chaplain (1929), The Fatal Warning (1929) for Richard Thorpe, The Phantom of the North (1929), Two Sisters (1929), Anne Against the World (1929), Behind That Curtain (1929), and The King of the Kongo (1929), a serial directed by Thorpe.

Karloff had an uncredited bit part in The Unholy Night (1930) directed by Lionel Barrymore, and bigger parts in The Bad One (1930),The Sea Bat (1930) (directed by Barrymore), and The Utah Kid (1930) directed by Thorpe.

A film which brought Karloff recognition was The Criminal Code (1931), a prison drama directed by Howard Hawks in which he reprised a dramatic part he had played on stage. In the same period, Karloff had a small role as a mob boss in Hawks' gangster film Scarface, but the film was not released until 1932 because of difficult censorship issues.

He did another serial for Thorpe, King of the Wild (1931), then had support parts in Cracked Nuts (1931), Young Donovan's Kid (1931), Smart Money (1931), The Public Defender (1931), I Like Your Nerve (1931), and Graft (1931).

Another significant role in the autumn of 1931 saw Karloff play a key supporting part as an unethical newspaper reporter in Five Star Final, a film about tabloid journalism which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

He could also be seen in The Yellow Ticket (1931) The Mad Genius (1931), The Guilty Generation (1931) and Tonight or Never (1931).

Karloff acted in eighty movies before being found by James Whale and cast in Frankenstein (1931). Karloff's role as Frankenstein's monster was physically demanding – it necessitated a bulky costume with four-inch platform boots – but the costume and extensive makeup produced a lasting image. The costume was a job in itself for Karloff with the shoes weighing 11 pounds (5.0 kg) each.[13] Universal Studios quickly copyrighted the makeup design for the Frankenstein monster that Jack P. Pierce had created.

It took a while for Karloff's stardom to be established with the public – he had small roles in Behind the Mask (1932), Business and Pleasure (1932) and The Miracle Man (1932).

As receipts for Frankenstein and Scarface flooded in, Universal gave Karloff third billing in Night World (1932), with Lew Ayres, Mae Clarke and George Raft.

Karloff was reunited with Whale at Universal for The Old Dark House (1932), a horror movie based on the novel Benighted by J.B. Priestley, in which he finally enjoyed top billing above Melvyn Douglas, Charles Laughton, Raymond Massey and Gloria Stuart. He was loaned to MGM to play the titular role in The Mask of Fu Manchu (also 1932), for which he gained top billing.

Back at Universal, he was cast as Imhotep who is revived in The Mummy (1932). It was as successful at the box-office as the other two films and Karloff was now established as a star of horror films.

Karloff returned to England to star in The Ghoul (1933), then made a non-horror film for John Ford, The Lost Patrol (1934), where his performance was highly acclaimed.

Karloff was third billed in the Twentieth Century Pictures historical film The House of Rothschild (1934) with George Arliss, which was highly popular.

Horror, however, had now become Karloff's primary genre, and he gave a string of lauded performances in Universal's horror films, including several with Bela Lugosi, his main rival as heir to Lon Chaney's status as the leading horror film star. While the long-standing, creative partnership between Karloff and Lugosi never led to a close friendship, it produced some of the actors' most revered and enduring productions, beginning with The Black Cat (1934) and continuing with Gift of Gab (1934), in which both had cameos. Karloff reprised the role of Frankenstein's monster in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) for James Whale. Then he and Lugosi were reunited for The Raven (1935).

For Columbia, Karloff made The Black Room (1935) then he returned to Universal for The Invisible Ray (1936) with Lugosi, more a science fiction film. Karloff was then cast in a Warner Bros. horror film, The Walking Dead (1936).

Because the Motion Picture Production Code (known as the Hays Code) began to be seriously enforced in 1934, horror films suffered a decline in the second half of the 1930s. Karloff worked in other genres, making two films in Britain, Juggernaut (1936) and The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936).

He returned to Hollywood to play a supporting role in Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936) then did a science fiction film, Night Key (1937).

At Warners, he did two films with John Farrow, playing a Chinese warlord in West of Shanghai (1937) and a murder suspect in The Invisible Menace (1938).

Karloff went to Monogram to play the title role of a Chinese detective in Mr. Wong, Detective (1938), which led to a series. Karloff's portrayal of the character is an example of Hollywood's use of yellowface and its portrayal of East Asians in the earlier half of the 20th century. He had another heroic role in Devil's Island (1939).

Universal found reissuing Dracula and Frankenstein led to success at the box-office and began to produce horror films again starting with Son of Frankenstein (1939). Karloff reprised his role, with Lugosi co starring as Ygor and Basil Rathbone as Frankenstein.

After The Mystery of Mr. Wong (1939) and Mr. Wong in Chinatown (1939) he signed a three-picture deal with Columbia, starting with The Man They Could Not Hang (1939). Karloff returned to Universal to make Tower of London (1939) with Rathbone, playing the murderous henchman of King Richard III.

Karloff made a fourth Mr Wong film at Monogram The Fatal Hour (1940). At Warners he was in British Intelligence (1940), then he went to Universal to do Black Friday (1940) with Lugosi.

Karloff's second and third films for Columbia were The Man with Nine Lives (1940) and Before I Hang (1940). In between he did a fifth and final Mr Wong film, Doomed to Die (1940).

Karloff appeared at a celebrity baseball game as Frankenstein's monster in 1940, hitting a gag home run and making catcher Buster Keaton fall into an acrobatic dead faint as the monster stomped into home plate.

Karloff finished a six picture commitment with Monogram with The Ape (1940). He and Lugosi appeared in a comedy at RKO, You'll Find Out (1941), then he went to Columbia for The Devil Commands (1941) and The Boogie Man Will Get You (1941).

An enthusiastic performer, he returned to the Broadway stage in the original production of Arsenic and Old Lace in 1941, in which he played a homicidal gangster enraged to be frequently mistaken for Karloff. Frank Capra cast Raymond Massey in the 1944 film, which was shot in 1941, while Karloff was still appearing in the role on Broadway. The play's producers allowed the film to be made conditionally: it was not to be released until the production closed. (Karloff reprised his role on television in the anthology series The Best of Broadway (1955), and with Tony Randall and Tom Bosley in a 1962 production on the Hallmark Hall of Fame. He also starred in a radio adaptation produced by Screen Guild Theatre in 1946.)

In 1944, he underwent a spinal operation to relieve a chronic arthritic condition.

Karloff returned to film roles in The Climax (1944), an unsuccessful attempt to repeat the success of Phantom of the Opera (1943). More liked was House of Frankenstein (1944), where Karloff played the villainous Dr. Niemann and the monster was played by Glenn Strange.

Karloff made three films for producer Val Lewton at RKO: The Body Snatcher (1945), his last teaming with Lugosi, Isle of the Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946).

In a 1946 interview with Louis Berg of the Los Angeles Times, Karloff discussed his arrangement with RKO, working with Lewton and his reasons for leaving Universal. Karloff left Universal because he thought the Frankenstein franchise had run its course; the entries in the series after Son of Frankenstein were B-pictures. Berg wrote that the last installment in which Karloff appeared—House of Frankenstein—was what he called a " 'monster clambake,' with everything thrown in—Frankenstein, Dracula, a hunchback and a 'man-beast' that howled in the night. It was too much. Karloff thought it was ridiculous and said so." Berg explained that the actor had "great love and respect for" Lewton, who was "the man who rescued him from the living dead and restored, so to speak, his soul."

Horror films experienced a decline in popularity after the war, and Karloff found himself working in other genres.

For the Danny Kaye comedy, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947), Karloff appeared in a brief but starring role as Dr. Hugo Hollingshead, a psychiatrist. Director Norman Z. McLeod shot a sequence with Karloff in the Frankenstein monster make-up, but it was deleted from the finished film.

Karloff appeared in a film noir, Lured (1947), and as an Indian in Unconquered (1947). He had support roles in Dick Tracy Meets Gruesome (1947), Tap Roots (1948), and Abbott and Costello Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff.

During this period, Karloff was a frequent guest on radio programmes, whether it was starring in Arch Oboler's Chicago-based Lights Out productions (including the episode "Cat Wife") or spoofing his horror image with Fred Allen or Jack Benny. In 1949, he was the host and star of Starring Boris Karloff, a radio and television anthology series for the ABC broadcasting network.

He appeared as the villainous Captain Hook in Peter Pan in a 1950 stage musical adaptation which also featured Jean Arthur.

Karloff returned to horror films with The Strange Door (1951) and The Black Castle (1952).

He was nominated for a Tony Award for his work opposite Julie Harris in The Lark, by the French playwright Jean Anouilh, about Joan of Arc, which was reprised on Hallmark Hall of Fame.

During the 1950s, he appeared on British television in the series Colonel March of Scotland Yard, in which he portrayed John Dickson Carr's fictional detective Colonel March, who was known for solving apparently impossible crimes. Christopher Lee appeared alongside Karloff in the episode "At Night, All Cats are Grey" broadcast in 1955.[17] A little later, Karloff co-starred with Lee in the film Corridors of Blood (1958).

Karloff appeared in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1952) and visited Italy for The Island Monster (1954) and India for Sabaka (1954).

Karloff, along with H. V. Kaltenborn, was a regular panelist on the NBC game show, Who Said That? which aired between 1948 and 1955. Later, as a guest on NBC's The Gisele MacKenzie Show, Karloff sang "Those Were the Good Old Days" from Damn Yankees while Gisele MacKenzie performed the solo, "Give Me the Simple Life". On The Red Skelton Show, Karloff guest starred along with actor Vincent Price in a parody of Frankenstein, with Red Skelton as "Klem Kadiddle Monster". He served as host and frequent star of the anthology series The Veil (1958) which was never broadcast due to financial problems at the producing studio; the complete series was rediscovered in the 1990s.

Karloff made some horror films in the late 1950s: Voodoo Island (1957), The Haunted Strangler (1958), Frankenstein 1970 (1958) (as the Baron), and Corridors of Blood (1958). In the "mad scientist" role in Frankenstein 1970 as Baron Victor von Frankenstein II, the grandson of the original creator. In the finale, it is revealed that the crippled Baron has given his own face to the monster. Karloff donned the monster make-up for the last time in 1962 for a Halloween episode of the TV series Route 66, which also featured Peter Lorre and Lon Chaney, Jr.

During this period, he hosted and acted in a number of television series, including Thriller and Out of This World.

Karloff appeared in Black Sabbath (1963) directed by Mario Bava. He made The Raven (1963) for Roger Corman and American International Pictures (AIP). Corman used Karloff in The Terror (1963) playing a baron who murdered his wife. He made a cameo in AIP's Bikini Beach (1964) and had a bigger role in that studio's The Comedy of Terrors (1964), directed by Jacques Tourneur and Die, Monster, Die! (1965). British actress Suzan Farmer, who played his daughter in the film, later recalled Karloff was aloof during production "and wasn’t the charming personality people perceived him to be".

In 1966, Karloff also appeared with Robert Vaughn and Stefanie Powers in the spy series The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., in the episode "The Mother Muffin Affair," Karloff performed in drag as the titular character.

That same year, he also played an Indian Maharajah on the installment of the adventure series The Wild Wild West titled "The Night of the Golden Cobra".

In 1967, he played an eccentric Spanish professor who believes himself to be Don Quixote in a whimsical episode of I Spy titled "Mainly on the Plains".

Karloff's last film for AIP was The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1967).

In the mid-1960s, he enjoyed a late-career surge in the United States when he narrated the made-for-television animated film of Dr. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and also provided the voice of the Grinch, although the song "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch" was sung by the American voice actor Thurl Ravenscroft. The film was first broadcast on CBS-TV in 1966. Karloff later received a Grammy Award for "Best Recording For Children" after the recording was commercially released. Because Ravenscroft (who never met Karloff in the course of their work on the show) was uncredited for his contribution to How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, his performance of the song was often mistakenly attributed to Karloff.

He appeared in Mad Monster Party? (1967) and starred in the second feature film of the British director Michael Reeves,The Sorcerers (1966).

Karloff starred in Targets (1968), a film directed by Peter Bogdanovich, featuring two separate stories that converge into one. In one, a disturbed young man kills his family, then embarks on a killing spree. In the other, a famous horror-film actor contemplates then confirms his retirement, agreeing to one last appearance at a drive-in cinema. Karloff starred as the retired horror film actor, Byron Orlok, a thinly disguised version of himself; Orlok was facing an end of life crisis, which he resolved through a confrontation with the gunman at the drive-in cinema.

Around the same time, he played occult expert Professor Marsh in a British production titled The Crimson Cult (Curse of the Crimson Altar, also 1968), which was the last Karloff film to be released during his lifetime.

He ended his career by appearing in four low-budget Mexican horror films: Isle of the Snake People, The Incredible Invasion, Fear Chamber and House of Evil. This was a package deal with Mexican producer Luis Enrique Vergara. Karloff's scenes were directed by Jack Hill and shot back-to-back in Los Angeles in the spring of 1968. The films were then completed in Mexico. All four were released posthumously, with the last, The Incredible Invasion, not released until 1971, two years after Karloff's death. Cauldron of Blood, shot in Spain in 1967 and co-starring Viveca Lindfors, was also released after Karloff's death.

While shooting his final films, Karloff suffered from emphysema. Only half of one lung was still functioning and he required oxygen between takes.

He recorded the title role of Shakespeare's Cymbeline for the Shakespeare Recording Society (Caedmon Audio). The recording was originally released in 1962. A download of his performance is available from audible.com. He also recorded the narration for Sergei Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf with the Vienna State Opera Orchestra under Mario Rossi.

Records he made for the children's market included Three Little Pigs and Other Fairy Stories, Tales of the Frightened (volume 1 and 2), Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories and, with Cyril Ritchard and Celeste Holm, Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes, and Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark.

Karloff was credited for editing several horror anthologies, commencing with Tales of Terror (Cleveland and NY: World Publishing Co, 1943) (compiled with the help of Edmond Speare). This wartime-published anthology went through at least five printings to September 1945. It has been reprinted recently (Orange NJ: Idea Men, 2007). Karloff's name was also attached to And the Darkness Falls (Cleveland and NY: World Publishing Co, 1946); and The Boris Karloff Horror Anthology (London: Souvenir Press, 1965; simultaneous publication in Canada - Toronto: The Ryerson Press; US pbk reprint NY: Avon Books, 1965 retitled as Boris Karloff's Favourite Horror Stories; UK pbk reprints London: Corgi, 1969 and London: Everest, 1975, both under the original title), though it is less clear whether Karloff himself actually edited these.

Tales of the Frightened (Belmont Books, 1963), though based on the recordings by Karloff of the same title, and featuring his image on the book cover, contained stories written by Michael Avallone; the second volume, More Tales of the Frightened, contained stories authored by Robert Lory. Both Avallone and Lory worked closely with Canadian editor and book packager Lyle Kenyon Engel, who also ghost-edited a horror story anthology for horror film star Basil Rathbone.

Beginning in 1940, Karloff dressed as Father Christmas every Christmas to hand out presents to physically disabled children in a Baltimore hospital.

He never legally changed his name to "Boris Karloff." He signed official documents "William H. Pratt, a.k.a. Boris Karloff."

He was a charter member of the Screen Actors Guild, and he was especially outspoken due to the long hours he spent in makeup while playing Frankenstein's Monster.

He married six times and had one child, daughter Sara Karloff, by fifth wife Dorothy Stine. His final marriage was in 1946 right after his fifth divorce. At the time of his daughter's birth, he was filming Son of Frankenstein and reportedly rushed from the film set to the hospital while still in full makeup.

He was an early member of the Hollywood Cricket Club.

Upon returning to England in 1959, his address was 43 Cadogan Square, London. In 1966, he bought 25 Campden House (in 29 Sheffield Terrace), Kensington W8, and 'Roundabout Cottage' in the Hampshire village of Bramshott. A longtime heavy smoker, he had emphysema which left him with only half of one lung still functioning. He contracted bronchitis in 1968 and was hospitalised at University College Hospital. He died of pneumonia at the King Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst, in Sussex, on 2 February 1969, at the age of 81.

His body was cremated following a requested modest service at Guildford Crematorium, Godalming, Surrey, where he is commemorated by a plaque in the Garden of Remembrance. A memorial service was held at St Paul's, Covent Garden (the Actors' Church), London, where there is also a plaque.

During the run of Thriller, Karloff lent his name and likeness to a comic book for Gold Key Comics based upon the series. After Thriller was cancelled, the comic was retitled Boris Karloff's Tales of Mystery. An illustrated likeness of Karloff continued to introduce each issue of this publication for more than a decade after his death; the comic lasted until the early 1980s. In 2009, Dark Horse Comics began publishing reprints of Boris Karloff's Tales of Mystery in a hard-bound edition.

For his contribution to film and television, Boris Karloff was awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 1737 Vine Street for motion pictures, and 6664 Hollywood Boulevard for television.[36] Karloff was featured by the U.S. Postal Service as Frankenstein's Monster and the Mummy in its series "Classic Monster Movie Stamps" issued in September 1997. In 1998, an English Heritage blue plaque was unveiled in his hometown in London. The British film magazine Empire in 2016 ranked Karloff's portrayal as Frankenstein's monster the sixth-greatest horror movie character of all time.

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Boris Karloff among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.

#boris karloff#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#classic hollywood#1910s movies#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#1960s hollywood#classic horror#horror icons#frankenstein#the mummy#hollywood legend

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carter G. Woodson

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the African diaspora, including African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the "father of black history". In February 1926 he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week", the precursor of Black History Month.

Born in Virginia, the son of former slaves, Woodson had to put off schooling while he worked in the coal mines of West Virginia. He made it to Berea College, becoming a teacher and school administrator. He gained graduate degrees at the University of Chicago and in 1912 was the second African American, after W. E. B. Du Bois, to obtain a PhD degree from Harvard University. Most of Woodson's academic career was spent at Howard University, a historically black university in Washington, D.C., where he eventually served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Early life and education

Carter G. Woodson was born in New Canton, Virginia on December 19, 1875, the son of former slaves, Anne Eliza (Riddle) and James Henry Woodson. His parents were both illiterate and his father, who had helped the Union soldiers during the Civil War, supported the family as a carpenter and farmer. The Woodson family were extremely poor, but proud as both his parents told him that it was the happiest day of their lives when they became free. Woodson was often unable to regularly attend primary school so as to help out on the farm. Nonetheless, through self-instruction, he was able to master most school subjects.

At the age of seventeen, Woodson followed his brother to Huntington, where he hoped to attend the brand new secondary school for blacks, Douglass High School. However, Woodson, forced to work as a coal miner, was able to devote only minimal time each year to his schooling. In 1895, the twenty-year-old Woodson finally entered Douglass High School full-time, and received his diploma in 1897. From 1897 to 1900, Woodson taught at Winona. In 1900 he was selected as the principal of Douglass High School. He earned his Bachelor of Literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1903 by taking classes part-time between 1901 and 1903. From 1903 to 1907, Woodson was a school supervisor in the Philippines.

Woodson later attended the University of Chicago, where he was awarded an A.B. and A.M. in 1908. He was a member of the first black professional fraternity Sigma Pi Phi and a member of Omega Psi Phi.He completed his PhD in history at Harvard University in 1912, where he was the second African American (after W. E. B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate. His doctoral dissertation, The Disruption of Virginia, was based on research he did at the Library of Congress while teaching high school in Washington, D.C. After earning the doctoral degree, he continued teaching in public schools, as no university was willing to hire him, ultimately becoming the principal of the all-black Armstrong Manual Training School in Washington D.C. He later joined the faculty at Howard University as a professor, and served there as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. His dissertation advisor was Albert Bushnell Hart, who had also been the advisor for Du Bois, with Edward Channing and Charles Haskins also on the committee.

Woodson felt that the American Historical Association (AHA) had no interest in black history, noting that though he was a due-paying member of the AHA, he was not allowed to attend AHA conferences. Woodson became convinced he had no future in the white-dominated historical profession, and to work as a black historian would require creating an institutional structure that would make it possible for black scholars to study history. As Woodson lacked the funds to finance such a new institutional structure himself, he turned to philanthropist institutions such as the Carnegie Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Career

Convinced that the role of his own people in American history and in the history of other cultures was being ignored or misrepresented among scholars, Woodson realized the need for research into the neglected past of African Americans. Along with William D. Hartgrove, George Cleveland Hall, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History on September 9, 1915, in Chicago. That was the year Woodson published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. His other books followed: A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The History of the Negro Church (1927). His work The Negro in Our History has been reprinted in numerous editions and was revised by Charles H. Wesley after Woodson's death in 1950. Woodson described the purpose of the ASNLH as the "scientific study" of the "neglected aspects of Negro life and history" by training a new generation of blacks in historical research and methodology. Believing that history belonged to everybody, not just the historians, Woodson sought to engage black civic leaders, high school teachers, clergymen, women's groups and fraternal associations in his project to improve the understanding of Afro-American history.

In January 1916, Woodson began publication of the scholarly Journal of Negro History. It has never missed an issue, despite the Great Depression, loss of support from foundations, and two World Wars. In 2002, it was renamed the Journal of African American History and continues to be published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).

Woodson stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA during visits to Chicago. His experiences at the Y and in the surrounding Bronzeville neighborhood inspired him to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) ran conferences, published The Journal of Negro History, and "particularly targeted those responsible for the education of black children". Another inspiration was John Wesley Cromwell's 1914 book, The Negro in American History: Men and Women Eminent in the Evolution of the American of African Descent.

Woodson believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among blacks and whites could reduce racism and he promoted the organized study of African-American history partly for that purpose. He would later promote the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926, forerunner of Black History Month.The Bronzeville neighborhood declined during the late 1960s and 1970s like many other inner-city neighborhoods across the country, and the Wabash Avenue YMCA was forced to close during the 1970s, until being restored in 1992 by The Renaissance Collaborative.

He served as Academic Dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute, now West Virginia State University, from 1920 to 1922. By 1922, Woodson's experience of academic politics and intrigue had left him so disenchanted with university life that he vowed never to work in academia again.

He studied many aspects of African-American history. For instance, in 1924, he published the first survey of free black slaveowners in the United States in 1830.

NAACP

Woodson became affiliated with the Washington, D.C. branch of the NAACP, and its chairman Archibald Grimké. On January 28, 1915, Woodson wrote a letter to Grimké expressing his dissatisfaction with activities and making two proposals:

That the branch secure an office for a center to which persons may report whatever concerns the black race may have, and from which the Association may extend its operations into every part of the city; and

That a canvasser be appointed to enlist members and obtain subscriptions for The Crisis, the NAACP magazine edited by W. E. B. Du Bois.

Du Bois added the proposal to divert "patronage from business establishments which do not treat races alike," that is, boycott businesses. Woodson wrote that he would cooperate as one of the twenty-five effective canvassers, adding that he would pay the office rent for one month. Grimké did not welcome Woodson's ideas.

Responding to Grimké's comments about his proposals, on March 18, 1915, Woodson wrote:

I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. In fact, I should welcome such a law suit. It would do the cause much good. Let us banish fear. We have been in this mental state for three centuries. I am a radical. I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me.

His difference of opinion with Grimké, who wanted a more conservative course, contributed to Woodson's ending his affiliation with the NAACP.

Black History Month

Woodson devoted the rest of his life to historical research. He worked to preserve the history of African Americans and accumulated a collection of thousands of artifacts and publications. He noted that African-American contributions "were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them." Race prejudice, he concluded, "is merely the logical result of tradition, the inevitable outcome of thorough instruction to the effect that the Negro has never contributed anything to the progress of mankind."

The summer of 1919 was the "Red Summer", a time of intense racial violence that saw about 1,000 people, most of whom were black, killed between May and September 1919. In the face of widespread disillusionment felt in black America caused by the "Red Summer", Carter worked hard to improve the understanding of black history, later writing "I have made every sacrifice for this movement. I have spent all my time doing this one thing and trying to do it efficiently". The 1920s were a time of rising black self-consciousness expressed variously in movements such as the Harlem Renaissance and the Universal Negro Improvement Association led by an extremely charismatic Jamaican immigrant Marcus Garvey. In this atmosphere, Woodson was considered by other black Americans to be one of their most important community leaders who discovered their "lost history". Woodson's project for the "New Negro History" had a dual purpose of giving black Americans a history to be proud of and to ensure that the overlooked role of blacks in American history was acknowledged by white historians. Woodson wrote that he wanted a history that would ensure that "the world see the Negro as a participant rather than as a lay figure in history".

Woodson wrote "while the Association welcomes the cooperation of white scholars in certain projects...it proceeds also on the basis that its important objectives can be attained through Negro investigators who are in a position to develop certain aspects of the life and history of the race which cannot otherwise be treated. In the final analysis, this work must be done by Negroes...The point here is rather that Negroes have the advantage of being able to think black". Woodson's claim that only black historians could really understand black history anticipated the fierce debates that rocked the American historical profession in the 1960s-1970s when a younger generation of black historians claimed that only blacks were qualified to write about black history. Despite these claims, the need for money ensured that Woodson had several white philanthropists such as Julius Rosenwald, George Foster Peabody, and James H. Dillard elected to the board of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Woodson preferred whites such as Rosenwald who were willing to finance his Association, but did not want to be involved in its work. Some of the whites that Woodson recruited such as the historian Albert Bushnell Hart and the teacher Thomas Jesse Jones were not content to play the passive role that he wanted, leading to personality clashes as both Hart and Jones wanted to write about black history. In 1920, both Jones and Hart resigned from the Board in protest against Woodson.

In 1926, Woodson pioneered the celebration of "Negro History Week", designated for the second week in February, to coincide with marking the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The Black United Students and Black educators at Kent State University expanded this idea to include an entire month beginning on February 1, 1970. Beginning in 1976 every US president has designated February as Black History Month.

Colleagues

Woodson believed in self-reliance and racial respect, values he shared with Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist who worked in New York. Woodson became a regular columnist for Garvey's weekly Negro World.

Woodson's political activism placed him at the center of a circle of many black intellectuals and activists from the 1920s to the 1940s. He corresponded with W. E. B. Du Bois, John E. Bruce, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Hubert H. Harrison, and T. Thomas Fortune, among others. Even with the extended duties of the Association, Woodson was able to write academic works such as The History of the Negro Church (1922), The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), and others which continue to have wide readership.

Woodson did not shy away from controversial subjects, and used the pages of Black World to contribute to debates. One issue related to West Indian/African-American relations. He summarized that "the West Indian Negro is free", and observed that West Indian societies had been more successful at properly dedicating the necessary amounts of time and resources needed to educate and genuinely emancipate people. Woodson approved of efforts by West Indians to include materials related to Black history and culture into their school curricula.

Woodson was ostracized by some of his contemporaries because of his insistence on defining a category of history related to ethnic culture and race. At the time, these educators felt that it was wrong to teach or understand African-American history as separate from more general American history. According to these educators, "Negroes" were simply Americans, darker skinned, but with no history apart from that of any other. Thus Woodson's efforts to get Black culture and history into the curricula of institutions, even historically Black colleges, were often unsuccessful.

Death and legacy

Woodson died suddenly from a heart attack in the office within his home in the Shaw, Washington, D.C. neighborhood on April 3, 1950, at the age of 74. He is buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland.

The time that schools have set aside each year to focus on African-American history is Woodson's most visible legacy. His determination to further the recognition of the Negro in American and world history, however, inspired countless other scholars. Woodson remained focused on his work throughout his life. Many see him as a man of vision and understanding. Although Woodson was among the ranks of the educated few, he did not feel particularly sentimental about elite educational institutions. The Association and journal that he started are still operating, and both have earned intellectual respect.

Woodson's other far-reaching activities included the founding in 1920 of the Associated Publishers in Washington, D.C. This enabled publication of books concerning blacks that might not have been supported in the rest of the market. He founded Negro History Week in 1926 (now known as Black History Month). He created the Negro History Bulletin, developed for teachers in elementary and high school grades, and published continuously since 1937. Woodson also influenced the Association's direction and subsidizing of research in African-American history. He wrote numerous articles, monographs and books on Blacks. The Negro in Our History reached its 11th edition in 1966, when it had sold more than 90,000 copies.

Dorothy Porter Wesley recalled: "Woodson would wrap up his publications, take them to the post office and have dinner at the YMCA. He would teasingly decline her dinner invitations saying, 'No, you are trying to marry me off. I am married to my work'". Woodson's most cherished ambition, a six-volume Encyclopedia Africana, was incomplete at the time of his death.

Honors and tributes

In 1926, Woodson received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Spingarn Medal.

The Carter G. Woodson Book Award was established in 1974 "for the most distinguished social science books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States."

The U.S. Postal Service issued a 20-cent stamp honoring Woodson in 1984.

In 1992, the Library of Congress held an exhibition entitled Moving Back Barriers: The Legacy of Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had donated his collection of 5,000 items from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries to the Library.

His Washington, D.C. home has been preserved and designated the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Carter G. Woodson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

On February 1, 2018, he was honored with a Google Doodle.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

BYRON FOULGER

August 27, 1899

Byron Kay Foulger was born in Ogden, Utah. He attended the University of Utah and started acting through in community theatre. He made his Broadway debut in March 1920 in a production of Medea featuring Moroni Olsen (the Judge in “The Courtroom”), and performed in four more productions with Olsen on the 'Great White Way', back-to-back, ending in April 1922. He then toured with Olsen's stock company, and ended up at the Pasadena Playhouse, where he both acted and directed.

Foulger made his film debut in 1933 for RKO, just like Lucille Ball. Oddly, the two never appeared together despite him doing nearly 300 films from 1933 to 1952. In 1940, he did three films with William Frawley (Fred Mertz).

In 1952, Lucy and Foulger were both part of a color Westinghouse industrial film called Ellis in Freedomland. Foulger played a night watchman in a department store while Lucy was the voice of Lina the Launderette (aka Washing Machine).

BYRON (to Lucy): “You don’t have any friends, do you?” LUCY (tearing up): “No, I don’t!”

Foulger’s television career featured nearly 100 appearances but Lucy fans are bound to remember him as the spokesman of The Friends of the Friendless in “Lucy’s Last Birthday” (ILL S2;E25) in 1953.

DORIS: “Oh, shut up, Fred!”

It took a dozen years for Fouger to re-team with Lucy, in 1965′s “My Fair Lucy” (TLS S3;E20). He played Fred Dunbar, the henpecked husband of Doris (Reta Shaw). The character is named after Lucy’s brother, Fred, who also gave his first name to the landlord on “I Love Lucy.”

FRED: “Oh, shut up, Doris!”

The Countess (Ann Sothern) recruits Lucy Carmichael to con the Dunbars into financing her charm school by pretending to be transformed a la Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady. Foulger also worked with Sothern on two episodes of “My Mother the Car” in 1965 and 1966.

MR. TRINDLE (pointing excitedly to Lucy): “Yes! That’s the one! I’ll never forget in a thousand years! That’s her!”

Two years later, Foulger was back on “The Lucy Show” to play Mr. Trindle, owner of a jewelry store supposedly robbed by Lucy in “Lucy Meets the Law” (TLS S5;E19). This would be his last appearance opposite Lucille Ball.

FOULGER at DESILU!

Three years after his appearance on “I Love Lucy,” Foulger was seen on an episode of “Our Miss Brooks” with Eve Arden and Gale Gordon, filmed on the Desilu lot and aired on CBS.

In 1957 and 1958, he did two episodes of the CBS Desilu sitcom “December Bride” starring Verna Felton and Harry Morgan.

In 1958, he did two episodes (as different characters) on “The Danny Thomas Show” filmed at Desilu Studios.

In 1959, he did an episode of Desilu’s hit mobster series “The Untouchables”.

In the mid-1960s Foulger was on the Desilu lot to film three episodes of “The Andy Griffith Show” playing different characters each time.

Foulger was seen on all three of CBS’s inter-connected rural sitcoms: “The Beverly Hillbillies” (1962 & 1965), “Green Acres” (1966), and the recurring role of Mr. Guerney and Wendell Gibbs on 22 episodes of “Petticoat Junction” (1965-69).

From 1926 until his death he was married to actress Dorothy Adams, having one child, Rachel. Foulger died of heart trouble on April 4, 1970 at the age of 70.

#Byron Foulger#I Love Lucy#Lucille Ball#Petticoat Junction#The Lucy Show#Reta Show#CBS#Desilu#TV#Ellis in Freedomland#Andy Griffith Show#Danny Thomas Show#The Untouchables#December Bride#Our Miss Brooks#Moroni Olsen

2 notes

·

View notes