#el paso border

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

U.S.-Mexico Border Congestion Is Screwing Up The Automotive Industry

Increased border security means crossings have slowed to a crawl. A new wave of migrants from Central and South America looking to escape grave issues in their home countries are reportedly leading to logistical tangles for the automotive industry at the U.S.-Mexico border. At least 19,000 trucks hauling $1.9 billion in goods are currently idling in Mexico, according to Automotive News.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

I stand with the freedom loving people defending the Texas border against an illegal immigrant invasion!!

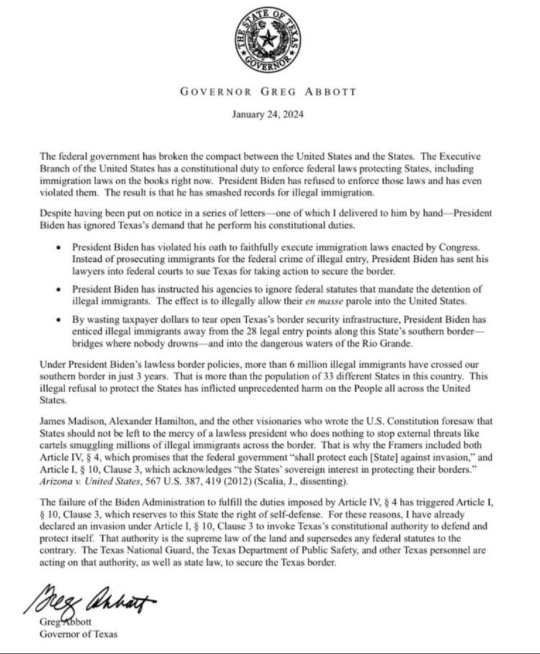

Good advice in 1775 and maybe even better advice in 2024!!

#lgb#fjb#the southern border is an invasion#southernborder#southern border#texas#el paso texas#harris county texas#houston texas#texas rangers#texa

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

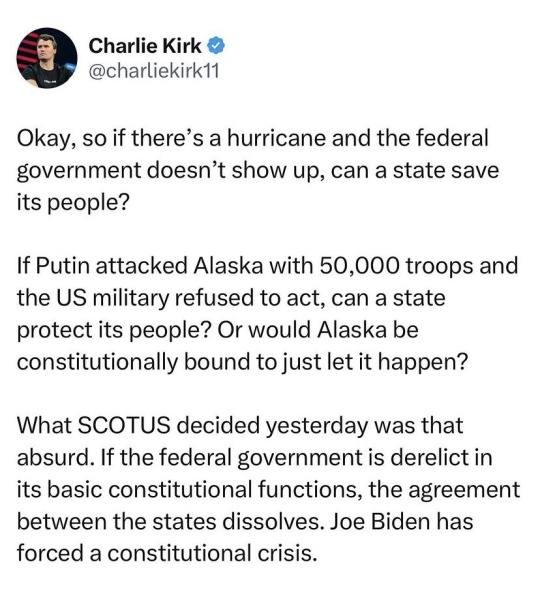

WTF?

About the surge of illegal immigrants in El Paso:

The TX National Guard & Dept. of Public Safety quickly regained control & are redoubling the razor wire barriers.

DPS is instructed to arrest every illegal immigrant involved for criminal trespass & destruction of property. 🤔

#pay attention#educate yourselves#educate yourself#knowledge is power#reeducate yourself#reeducate yourselves#think about it#think for yourselves#think for yourself#do your homework#do some research#do your own research#ask yourself questions#question everything#news#texas#border crisis#el paso#military

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, October 19, 2024 - Kamala Harris

Colin Allred, Beto O'Rourke, Stacey Plaskett, Laura Kelly, and the Vice President took the campaign to El Paso, TX to close out the campaigns swing through Texas. The 'official' schedule of today's events is below.

El Paso, TX (Event #1) Event Location: Paso Del Norte Event Type: Facility Tour Event Time: 8:00 -11:00 MT *The campaign took a facility tour of both the footbridge at the Paso Del Norte Bridge and the nearby US Customs and Border Protection building. Securing the border and reforming the immigration system are peak priorities for the Harris-Walz Campaign. We look forward to working with congress to find a solution to a problem that has been continued due to President Donald Trump axing a bipartisan bill.

El Paso, TX (Event #2) Event Location: University of Texas at El Paso Event Type: Get Out the Vote Event Time: 14:00 - 17:00 MT *The campaign held a Get Out the Vote campaign on-campus at UTEP today. We met with several students, faculty members, and community members alike. The campaign was positively received.

~BR~

#kamala harris#tim walz#harris walz 2024#campaigning#policy#2024 presidential election#legislation#united states#hq#politics#democracy#harris walz 2024 campaigning#texas#Colin Allred#stacey plaskett#beto o'rourke#UTEP#GOTV#get out the vote#border security#immigration reform#laura kelly#vote blue#vote vote vote#University of Texas at El Paso#El Paso#West Texas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#poynter's beat academy#us mexico border#migrants#asylum seekers#migration#el paso#texas#journalists#journalism#border field trip

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"…the El Paso Salt War. Which was not really a war, but popular uprising, a potently cinematic rebellion, and one that we had never even heard of. Which, when we read more about it later, seemed like that’s probably just how they want it."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

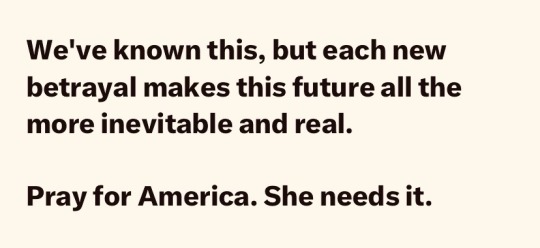

The air was polluted for three miles in any direction from the Asarco smelter plant, which was near the U.S.–Mexican border in El Paso, Texas.

After a 1970s CDC study showed that the mostly Mexican-American population of this Texas town had dangerously high blood lead levels, its buildings were demolished and its residents were booted.

The American Smelting and Refining Company owned a smelter in El Paso that, starting in 1910, refined hundreds of thousands of tons of lead and copper harvested from its mines in Mexico. It did so with the help of “an army of Mexican contract workers" according to a University of Houston associate professor of history.

Mexican workers who labored in Asarco mines began migrating north, lured by that new operation on the U.S. side of the border. Many settled on company land below the foothills of Mt. Cristo Rey. In the early years of the 20th century, Smeltertown lay outside El Paso city limits, a few miles from the city’s downtown.

By this time, Smeltertown had evolved from a small border town into an industrial hub for ASARCO. In 1900, Smeltertown had a population of 2,721. By 1920, the number grew to 3,119. Of this number, 95% were Mexican.

Smeltertown was designed by ASARCO to revolve all aspects of life around smelting. By creating a monopoly over labor in the town, the company could max their potential output for profit. To do this, managers needed an untainted focus on smelting at all hours of the day. Therefore, ASARCO strategically planned Smeltertown to invite and keep laborers.

The most enticing method in which ASARCO attracted foreign labor was company provided housing. Small tenement style apartments were constructed for all migrant employees. Located a short walk from the factory, it ensured that smelting was always on the minds of their workers. Homes lacked electricity, indoor plumbing, or furnished floors. These conditions were intentional. Not only did a lack of appliances keep costs cheap for ASARCO, it also kept laborers out of the comfort of their homes and therefore smelting more frequently.

A home in Smeltertown, April 27, 1957, University of Texas at El Paso Library Special Collections Department, Cassola Studio Photographs, PH 041

Racial Hierarchy

Smtertown was divided into an upper section, El Alto, where the Anglo managers lived, and a lower section, El Bajo, where the Mexican workers lived.

Migrants were easily exploited by Anglos in positions of power. St. John describes, “The borderlands labor market was segmented by race… working-class ethnic Mexicans who labored as cowboys, miners, and smelter workers earned lower wages and were denied better-paying jobs in favor of Anglo-Americans and European immigrants."

Poverty in Smeltertown could be extreme. Residents built and invested in their homes, but the company owned the land. As in other single-industry towns, Smeltertown’s residents fashioned their own way of life in the world the company made, one marked by inequality, racial segregation, and corporate paternalism.

This discrimination was most noticeable in the physical makeup of Smeltertown itself. Company owners and managers lived atop the hill in the gated Smelter Terrace, coined the "hidden oasis." These Anglos enjoyed paved driveways, green lawns, and swimming pools. A woman who grew up in Smeltertown notes, “I never went to Smelter Terrace, and I assume my mother did not either. There was no interaction between the workers and management children, I am now ashamed to say.”

On the contrary, blue collar immigrants lived at the bottom of the hill in adobe shacks that lacked running water and electricity. These row style living quarters were designed for single men working the smelting factory. Thus, when families followed along across the border, they were forced to squeeze into these tiny spaces. Children often slept on the dirt floors in order to fit everyone comfortably.

According to Daniel Solis, a former resident, “Smeltertown essentially was an eyesore for El Paso” an embarrassment to city officials and the company.

Sewage and water systems were built by the residents.

Daily Pollution Ignored by the City

The residents of Smeltertown also experienced the discomforts of living with ASARCO’s emissions on a daily basis. Sulfur dioxide, a major by-product of smelting, creates foul odors and can cause breathing problems and irritation of the eyes, throat and lungs. Daniel Solis recalls:

"In July and August … our folks would bring us into the house, because the smoke, the pollution, the sulfur, would settle into our community for about 2 or 3 hours every day in the mid-day when there was no breeze to take it away. When we would breathe that, we could not be outside because we were constantly coughing. So nobody can tell me that there was no ill effect on the majority of the folks that lived in Smeltertown."

Mary Romero writes that Smeltertown families tried early on to get the city to respond to problems of pollution.

Residents had organized in the 1950’s in an unsuccessful attempt to get the city to pave Smeltertown streets and thus control the dust problem. Several parents had sought medical attention for children born with brain damage and other illnesses; not one case, however, had been diagnosed as lead poisoning. Past attempts to label health problems as pollution-related illnesses had been unsuccessful.

Given the arduous work and poor living conditions, everyday lives of workers consisted of making the most of their situation.

ASARCO's company reign did not stop at housing. They constructed all resources necessary to function in Smeltertown in order to keep Mexicans from finding work elsewhere. Examine the list below to see all facets of life ASARCO controlled for their laborers.

Company Owned Estbalishments

Hospital

Supermarket

General Store

Jail

Post Office

A Closer Look: Company Store

The company store stocked items adapted to the needs of an isolated industrial community. Citizens could buy groceries, clothing, and even ship mail from the facility. The Smelter Store functioned by extending credit to workers that would eventually deduct from their weekly paycheck. ASARCO kept prices relatively high in comparison to their laborers' respective salaries in order to keep workers hungry for the money necessary to pay. Angel Luján, a former smelter explains, “it was like I owe my soul to the company store." Most laborers lived on a paycheck to paycheck basis due to this loan structure designed by ASARCO. To live a standard lifestyle in Smeltertown, Mexicans had to "sign away their paycheck and their lives" to the company.

“A Silent Poison”

In March 1971, a team of Epidemic Intelligence Service officers from the CDC arrived to investigate lead exposure connected to the Asarco smelter.

The El Paso City–County health commissioner, had called the CDC after his department discovered that Asarco was discharging large quantities of lead and other metallic wastes into the air. Between 1969 and 1971, the smelter’s stacks had spewed more than 1,000 tons of lead, 560 tons of zinc, 12 tons of cadmium, and 1.2 tons of arsenic into the atmosphere. Soil studies showed the highest concentrations of lead and other metals in surface soil closest to the smelter—essentially, in Smeltertown.

Smeltertown children on the way to school in a horse-drawn wagon, El Paso, ca. 1900, El Paso Historical Society

Although the CDC team found no cases of overt lead poisoning, 43 percent of people in all age groups and 62 percent of children 10 and under living within one mile of the smelter had blood lead levels of at least 40 micrograms per deciliter. That’s eight times the level at which the CDC recommends a full-fledged public health response today.

The CDC team quickly followed up with a second study in Smeltertown in 1972, examining the health consequences of lead exposure in children. The CDC team administered IQ tests and a finger-tapping test of physical reflexes to the Smeltertown kids with elevated blood levels; a control group of children with blood lead levels below 40 micrograms per deciliter was also tested. The study found that children with elevated blood lead levels tested as many as seven points lower on the IQ test than the control group; they also showed much slower reaction times on the physical reflexes test.

Initially, the families reacted to the disclosures of lead contamination with great concern and cooperated with the research teams and doctors who came to test and treat the children. Some children were taken out of the community to be tested—the 4 year-old sister of Daniel Solis was taken to Chicago, although, as Daniel recounts, “She had never been to the airport, much less on an airplane.” Most of the children were treated at local hospitals, using chelation therapy, a drug regimen designed to remove heavy metals from the blood. The treatment is painful, and can be prolonged.

Daniel recalls that his young siblings were terrified of the painful injections.

This is what scientists now know: Lead in the air or in dust, paint, or fumes can work its way into the human body. In children, lead can permanently damage the brain and nervous system. It can slow a child’s growth and development. It can cause learning, hearing, speech, and behavior problems. Studies—the Smeltertown study being among the first—have linked early-childhood lead exposure to reduced IQ, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, juvenile delinquency, and criminal behavior, according to the CDC.

The consequences of early-childhood lead exposure can be moderated by educational enrichment, something that may not be readily available in poor communities with fewer opportunities and resources.

The pediatrician who led the CDC team stated, “I’m convinced one of the reasons our society has allowed it to go on is because the effects disproportionately fall on poor and minority children. In Smeltertown, people were almost universally immigrants from Mexico.”

During the trial, Ken Nelson, Director of Environmental Sciences for ASARCO, testified that lead contamination in Smeltertown had been “overlooked” by the company ASARCO officials said it had “never occurred” to them to include Smeltertown in the company’s air pollution monitoring system.

Asarco fought hard against the notion that the elevated blood lead levels in Smeltertown had anything to do with the smelter, or that lead exposure was harming children’s development.

The company claimed that elevated blood lead levels were caused by lead paint and gasoline emissions. It commissioned its own parallel study of the health effects in children and found no evidence of IQ loss. But the findings by the health department and the CDC team contradicted the company’s. The closer to the smelter the sample, the higher the concentrations of lead in the air, dust, and soil; human blood levels mimicked that pattern. And the CDC's team findings on the children’s IQ and physical reflexes were irrefutable.

It is worth noting that despite their groundbreaking nature, the study findings received little national attention at the time; A report by the New York Times in 1972 was the lone article that the newspaper wrote about Smeltertown.

As part of the settlement, the city and Asarco decided Smeltertown would be demolished, its residents forced to relocate. In October 1972, not two years after the lead studies began—eviction notices went out to all Smeltertown residents ordering them to clear out of their homes by January 1.

It should also be noted that the demolition of Smeltertown represented the least expensive solution for the city and ASARCO.

A statement by ASARCO’s physician that if Smeltertown had been allowed to remain, it would have required a greater commitments of funds and services than either the city or company was willing to provide.

The demolition of Smeltertown did not solve the problem of ASARCO’s emissions. Although the problem was first defined as a community health problem; it was later redefined as a problem specific to Smeltertown.

Restricting government action to Smeltertown fulfilled several objectives for various local interest groups. Business and industry were reassured that environmental policies would not threaten future growth. Pollution abatement would be placed second to economic stability, and therefore the chances of plant shutdowns or corporate flight were lessened … city and state officials were able to ignore contamination and possible health threats in other parts of Texas, New Mexico and Mexico.

Daniel Solis argues that the eradication of Smeltertown destroyed a significant part of Mexican-American history in El Paso. Like Romero, he points out that the solution chosen by the city and the company redirected attention away from the wider problems of contamination that was affecting children, workers and communities in the region.

The problems resulting from ASARCO’s emissions resurfaced continually over the years of ASARCO's operations in El Paso. Although the plant closed in 1999, the toxic contamination from ASARCO continued to be the focus of community struggles with the company, as community members pressed for information about the extent of contamination on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Everything that made up Smeltertown—every home and shop—would be bulldozed. Everything but the smelter itself, which would run for another 26 years.

Tight-Knit Comunidad

Mechanical department workers at Asarco, November 16, 1950

Outside of the work itself, laborers grew to establish unique cultural communities through their shared experiences. By mutually bonding over the challenges posed by the comany town, Esmeltianos banded together. Mexican migrants created their own binational "Mexican town" in Smeltertown.

Many Mexicans created their own Mexican establishments such as general stores, restaurants, and push cart vendors. Providing a wide labor market, El Paso inspired many Esmeltianos to extend their communities outside the company lines of Smeltertown. By 1930, various Mexican neighborhoods and establishments sprawled out in the El Bajo area, completely unaffiliated with ASARCO. One such example was the town YMCA, developed as a communal space for Mexican children to socialize and exercise. Efforts like these developed a deeper kinship in Smeltertown, away from the grave reality of smelting for a company. Instead, Mexicans claimed the borderlands as their own by branding cultural ties to the region.

Simple beautfication projects such as gardening gave citizens agency over the lives they lived in Smeltertown. Esmeltianos placed a large focus on simple tasks that emphasized aspects of life away from the company. Across the highway, many of the adobe shacks rented by the families were transformed with household money. They did not earn any home equity or even reimbursement for their efforts, just the pride in making a comfortable home for their families. In doing so, Smeltertown veered further and further away from the corporate grasp of ASARCO. Esmeltianos curated their community by naming streets and organizing sub barrios of El Bajo with Mexican influence. The combination of these efforts manifested into a town with a purpose far deeper than smelting.

What was originally intended to be a regimented camp strategized to produce maximum smelting output morphed into a binational community dense with culture. ASARCO may have owned Smeltertown, but it was its Mexican inhabitants that transformed the border town into a vibrant community.

Rubén Escandon has been collecting oral histories about the town for years from his own relatives and others as a member of the committee that protects Mt. Cristo Rey and the giant white cross Smeltertown residents erected at its peak.

“Everybody knew everybody,” says Escandon, who was born in 1965 in the satellite community of La Calavera, or Skull Canyon, near the Smelter Cemetery.

Gabe Flores, born and raised in Smeltertown in the 1940s and ’50s, remembers that the local señoras would pay him a few coins to walk hot lunches of caldo de res (beef stew), tacos, and fresh corn tortillas up the hill to the smelter men, who would be black with soot. When times were lean, Flores recalls, neighbors would borrow from each other: a little food, money, whatever was needed.

“It was all family,” he says. “Nobody was ashamed. Everybody was the same. Maybe they went through harder times and just realized they had to help each other. The fact that we would help each other, it bonded us together.”

Gloria Peña, an El Paso field nurse independently contracted to help with the lead testing in Smeltertown, recognized “the deep sense of loss” residents felt at the prospect of losing their community. “This is the beauty of our language because when you say ‘community’ it doesn’t have the same impact on us as if you say ‘comunidad.’ That is what Smeltertown had.”

A blood test being prepared for one of 500 children being tested for blood lead poisoning, March 30, 1973

Former resident, Cecilia Flores Marquez stated about her three children, “When they were young, no [they did not have health issues]. But they are having issues now.” Her youngest daughter became allergic to metal in her 30s, she says—something the doctors say could be related to the lead exposure.

There were no long-term studies of the former residents of Smeltertown to measure the health outcomes of their exposure to lead. Today former residents are left guessing whether this or that disability, defect, or illness could have been caused by lead. They have no way of knowing for sure.

Smeltertown after it closed down, January 5, 1973

Asarco would run its smelter for another quarter century after bulldozing Smeltertown. It was not until the decline of world copper prices in 1999 that the smelter halted production and the company mothballed the facility, keeping only a skeleton crew on board. Ten years later, the smelter sat silently on the bluff, atop a century’s worth of hardened black slag.

Asarco’s towering smokestacks finally came down in 2013. Today there is almost nothing left of the company or Smeltertown but the slag-coated hillside and the graves in the Smelter Cemetery.

Sources: (×) (×) (x)

#🇲🇽#usa#united states#mexican history#history#racism#discrimination against mexicans#el paso#texas#American Smelting and Refining Company#mexico#mexican american#mexican#immigration#lead poisoning#ASARCO#smeltertown#CDC#new mexico#u.s. mexican border#hispanic#latino#latina#smelter#pollution#segregation#sulfur dioxide#air pollution#copper

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

peace on the Rio Grande, Juárez, México / 1.6.24

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rodeo nights. ⭐️🐂🌵🐴 🔴⚪️🔵

#rodeohouston#rodeostyle#rodeo clown#rodeo#rodeodrive#el paso#diablo#border patrol#longhorns#texas longhorns#cattle drive#cattle ranching#cattle#houston texans#monoprint#printmakingart#printmaking#printmaker#Alamo#remember the alamo#friday night lights#west texas#lone star state#don’t mess with texas#wild west#westerns#country music#country#line dancing#texas bbq

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lastnight.... it happened. It'll happen again until we get someone in office who wants it fixed. It is fixable- they just don't want it fixed!!

Storm is approaching, be ready 🙏

I am here my Lord...send me

Train hard

Pray HARDER.

#heathen#vikings#palidin#templar#warriormindset#warrior of light#thinblueline#modern templar#el paso#westtexas#texans#law enforcement#zombie hunter#protector#hunter gatherer#us mexico border#borderlands#border patrol#defend america#lord save us all#battleready#battle report#defend life#dont trust them#do not comply

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good advice in 1775 and good advice in 2024!!

#lgb#fjb#the southern border is an invasion#southernborder#southern border#texas rangers#houston texas#el paso texas#harris county texas#texas

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

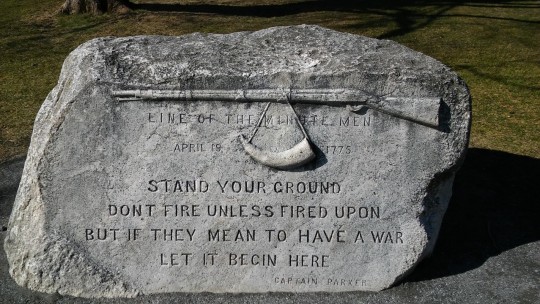

For context, I just find it funny how history books like to cover up how the US was a direct inspiration for the gas chambers used during the holocaust. The El Paso de-lousing chambers were racially motivated. The use of Zyklon B inspired German scientist Gerhard Peters to push for the chemical to be used to disinfect nazi concrntration camps.. He included photos of the El Paso de-lousing chambers as examples for how effective Zyklon B could be.

Obviously I cannot compare the atrocities of the holocaust to other historical incidents, but it's difficult to ignore how the US' own prejudice was an active inspiration for the gas chambers that would later kill millions.

#we point our bloodied fingers at other nations#history memes#history#history facts#historical#el paso#1917 bath riots#el paso bath riots#us border#gasoline baths at us border#holocaust#gas chambers#concentration camps#Gerhard Peters#Carmelita Torres

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Border Crisis Won’t Be Solved at the Border

If Texas officials wanted to stop the arrival of undocumented immigrants, they could try to make it impossible for them to work here. But that would devastate the state’s economy. So instead politicians engage in border theater.

By Jack Herrera

#history#white history#us history#am yisrael chai#jumblr#republicans#black history#democrats#immigrants#border#greg abbott#Rafael Cruz#ted cruz#rafael Ted Cruz#money#Capitalism#anti capitalism#texas#houston#San Antonio#el paso#Vice President Kamala Harris#VP Kamala Harris#VP Harris#Kamala Harris#Vice President Harris#Jill Stein#donald trump#trump#Harris

1 note

·

View note

Text

Speech Governor Walz gave in El Paso, TX!

~BR~

#El Paso#border security#immigration reform#immigration#daca#citizenship#refugees#asylum seekers#UTEP#University of Texas at el Paso#jasmine crockett#Divine Nine#Stacey Plaskett#beto o'rourke#Texas#kamala harris#tim walz#harris walz 2024#campaigning#policy#2024 presidential election#legislation#united states#hq#politics#democracy

2 notes

·

View notes