#early American

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

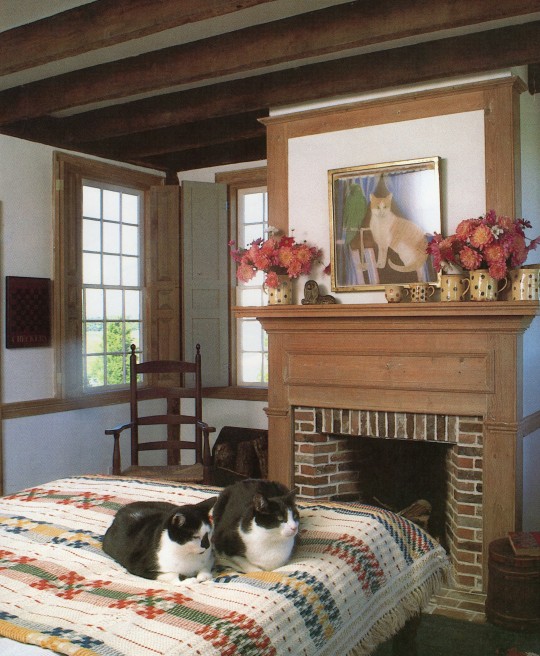

House Beautiful Weekend Homes, 1990

#vintage#vintage interior#1990s#90s#interior design#home decor#bedroom#bed#fireplace#cat#beamed ceiling#portrait#pottery#shutters#wood#early American#country#farmhouse#style#home#architecture

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

🕯️welcome to Shenandoah cottage 🕯️

#cottagecore#cottage aesthetic#cozycore#cozy aesthetic#winter#fall#christmas#autumn#1800s#1900s#early American#colonial era#dark academia#light academia

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dining Room Decor, 1972

#70s dining rooms#70s homes#70s decor#70s interiors#1972#1970s#70s#seventies#early 1970s#dining room decor#home decor#dining room ideas#home ideas#decor ideas#rustic decor#rustic dining rooms#early american#natural light

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

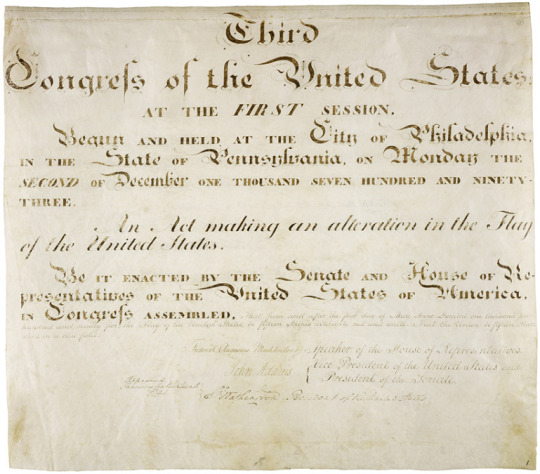

An Act Making an Alteration in the Flag of the United States

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States GovernmentSeries: Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of CongressFile Unit: Public Law, 3rd Congress, 1st Session: Alteration in the Flag of the United States, January 13, 1794

Third Congress of the United States AT THE FIRST SESSION Begun and held at the City of Philadelphia, IN THE State of Pennsylvania, ON Monday THE SECOND OF December ONE THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND NINETY-THREE. An Act making an alteration in the Flag of United States. Be IT ENACTED BY THE Senate AND House OF Representatives OF THE United States of America, IN Congress ASSEMBLED, [handwritten] That from and after the first day of May Anno Domini one thousand seven hundred and ninety five the Flag of the United States, be fifteen Stripes alternate red and blue. That the Union be fifteen Stars white in a blue field. Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg Speaker of the House of Representatives. John Adams [start bracket] Vice President of the United States and President of the Senate. [end bracket] Approved January the thirteenth 1794 Go. Washington. President of the United States.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ralph Earl, “Houses Fronting New Milford Green”, circa 1796

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

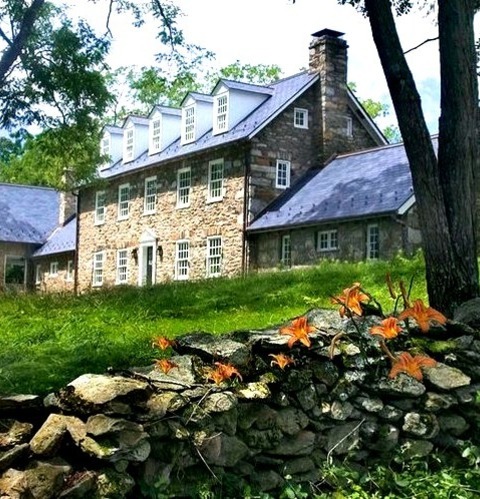

Stone in DC Metro Mid-sized country beige three-story stone exterior home idea with a shingle roof

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gravestone for Bartholomew Gedney, Copp's Hill Burying Ground, Boston, 2000.

Memorial Day 2023.

#gravestone#early american#cops hill burying ground#boston#massachusetts#2000#photographers on tumblr#black and white#copps hill burying ground

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Uncovered Deck in Boise picture of a large backyard deck in the mountains without a cover

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys. As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the daughters. As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste. He brought me to the banqueting house, and his banner over me was love. Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love. I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please. The voice of my beloved! behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills. My beloved spake, and said unto me, Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away. For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone --from Song of Solomon 2:1-11 (KJV)

I know it's a little early to be saying the winter is past - we've been known to get a little snow as late as early May on occasion - but on days when the birds are carrying on outside my window like they don't even know what winter is, sometimes I get those lines stuck in my head.

#william billings#choral music#early american#song of solomon#song of songs#i am the rose of sharon#springtime#classical music#18th century music#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Country Kitchens, 1991

#vintage#interior design#home#vintage interior#architecture#home decor#style#1990s#90s#dining room#windsor chair#fireplace#grandfather clock#antique#furniture#hooked rug#country#early American#baskets#rustic

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Living Room Decor, 1975

#70s living rooms#70s homes#70s decor#70s interiors#1975#1970s#70s#seventies#mid 1970s#living rom decor#home decor#living room ideas#home ideas#decor ideas#early american#traditonal decor#vintage decor

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

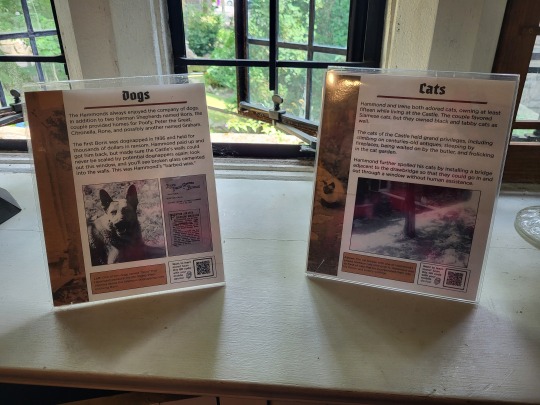

Early American Room July 28, 2024 Hammond Castle Museum Gloucester, Massachusetts

#massachusetts#gloucester#hammond castle#museums#castle#medieval aesthetic#fantasy castle#fairytale castle#fantasy#fairytale#early american#four poster bed#our adventures

0 notes

Text

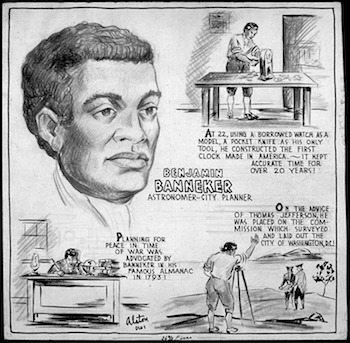

Scientist, mathematician, astronomer, surveyor, almanac author, among other accomplishments.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the other side by dean cornwell (1918)

#vintage#art#painting#oil painting#vintage aesthetic#aesthetic#oil on canvas#history#artwork#romantic academia#1900s#fine art#dark academia#canvas#artist#beauty#early 1900s#old art#old paintings#classic art#19th century art#oil on wood#culture#art history#vintage art#history aesthetic#classical art#museum#american art

12K notes

·

View notes