#diagnosed as unusual and perverse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I bet you say that to all the guys...

#star trek#star trek tos#leonard mccoy#jim kirk#spock#bones mccoy#captain kirk#amok time#the corbomite maneuver#mcspirk#maxstarfall#foamswords#just so you know I almost placed the post snippet over kirk's chest like a censor bar#but i decided to give the people what they want instead#diagnosed as unusual and perverse

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

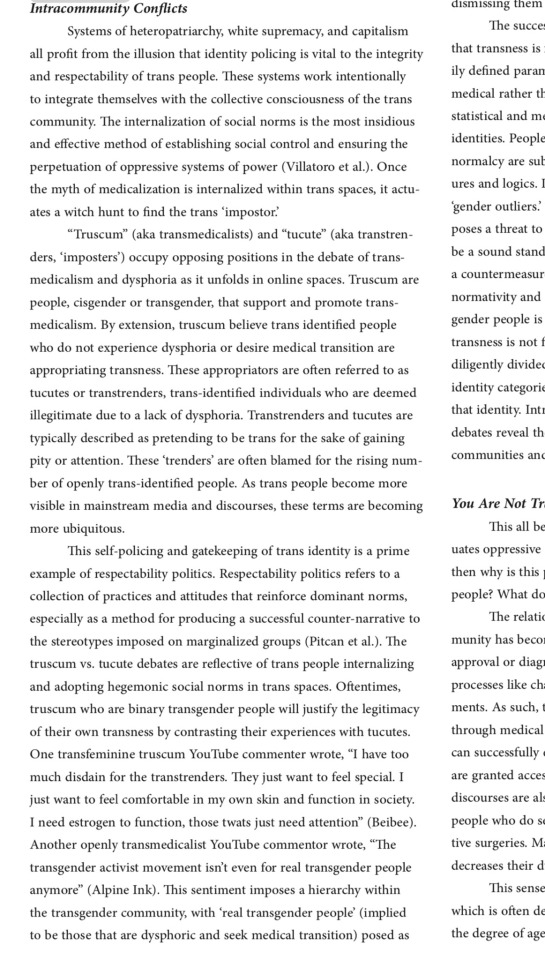

Transmedicalism (may give some trans folkx validity) is mosty transphobic to me.

I’ve seen a handful of trans people (and lots of cis het transphobes cheering them on, ofc) saying some transphobic shit about this whole Planet Fitness ordeal of a pre transition transwoman shaving her legs in a womans bathroom, and I guess some cishet paremt left their 12 year old alone in the bathroom and now TERFs and Transphobes (cis and het transphobes) are piling onto this occurence as “SEE I TOLD YOU! WE HAVE TO FORCE ANYONE WHO SAYS THEY ARE TRANS TO GO THROUGH HORMONES AND SURGERY BEFORE WE SAY THEY ARE REALLY TRANS”.

Ive even had some cis friends call me in a panic about it.

Yall need to realize, there ARE trans prople who are transphobic and the anti trans movement LOVES those token trans people.

(^Pic from source 2 below)

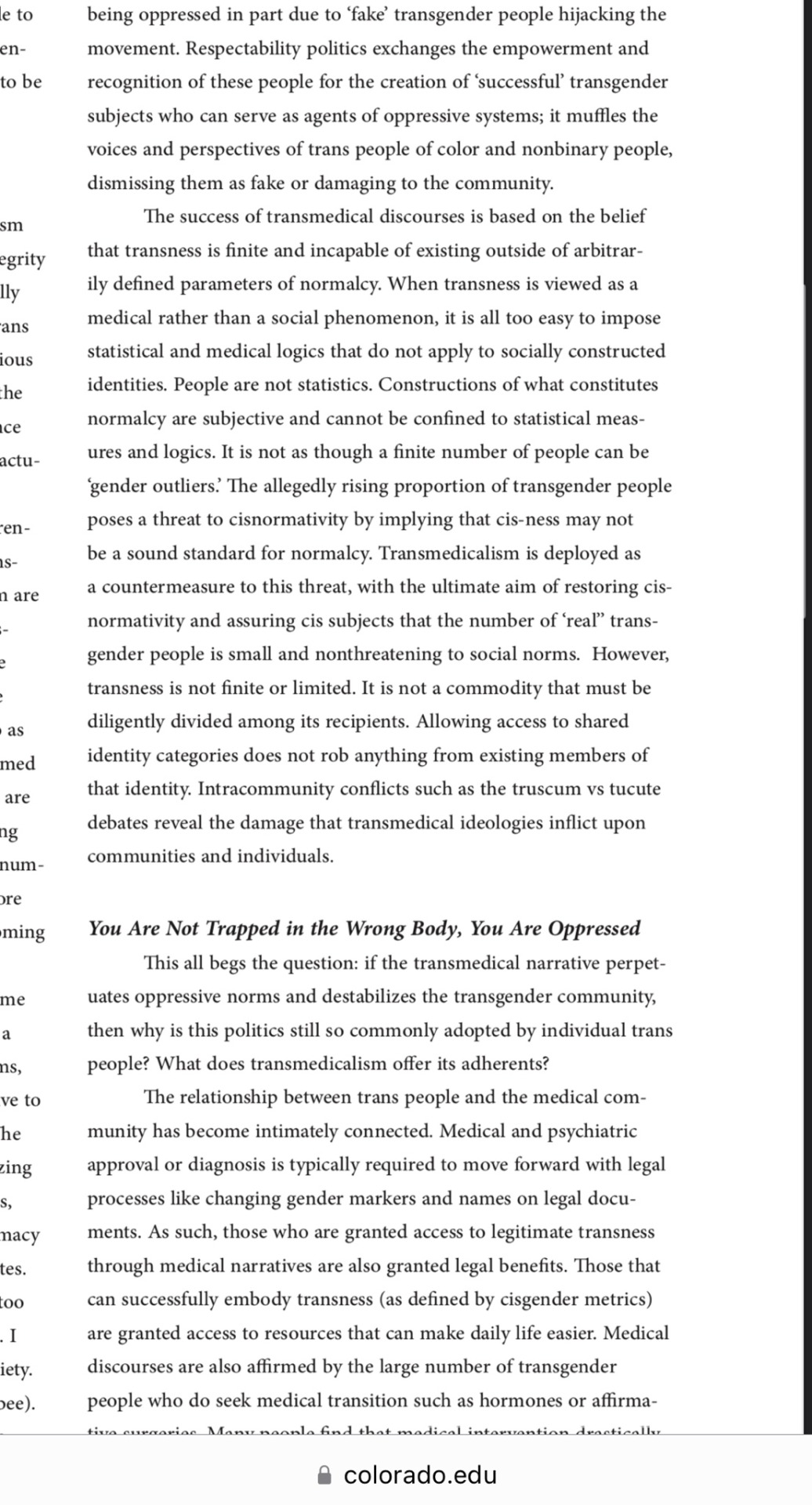

“Transmedicalism brings together unusual allies, some within the transphobic gender critical movement who see it as a useful tool in their quest to erase transgender people and their identities, and a minority within the community itself who believe that only those who have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria and who have completed surgical and other medical transition can truly be considered trans.

Claiming that gender dysphoria is intrinsic to having a transgender identity is a perspective that effectively erases the identity of a huge swathe of the transgender community, including non-binary people. It is also counter to any definition of being transgender outlined by public bodies and specialists, from:

The American Psychiatric Association (https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/gender-dysphoria)

to the NHS (https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/gender-dysphoria-clinical-programme/gender-dysphoria/)

Making gender dysphoria inherent to trans identity, experience, and indeed definitive to it, leads to a series of clearly untrue and indeed perverse conclusions.

It makes suffering intrinsic to trans identity and experience, something that is not only demonstrably untrue, but upon even a moment’s reflection, cruel as a framework. A person’s gender identity is not emergent from or dependent on trauma, and they don’t need to be subject to discomfort and suffering to ‘qualify’ as who they are.

It denies bodily autonomy and applies gatekeeping criteria to a person’s gender identity based on events to which they are physically and/or medically subjected.

It drags us back to a world where people claim that they can tell others who they are, what gender they experience, and undermine self-knowledge, with those requiring gender dysphoria as a ‘qualification’ of being trans claiming to control and define the gender identity and selfhood of others. This is in fact a component of transphobia and trans erasure, and a dangerous precedent for the community.”

^ Source 1: (https://www.gendergp.com/not-all-trans-people-experience-gender-dysphoria/

“Transmedicalism is a view of transgender identity that holds that experiencing dysphoria is required for ‘legitimate’ trans identity. This belief asserts that gender dysphoria, generally described as a feeling of distress originating from the incongruence between one’s assigned gender and gender identity, is a condition to be treated through medical intervention such as hormone therapy and gender affirming surgeries. Transmedicalism grounds transness in gender dysphoria, asserting that a lack of gender dysphoria is a lack of trans- ness.”

Further: “… transmedicalism is a nuanced framework of patholo- gizing transgender identity that depends on and perpetuates systems of oppression, intracommunity conflict, and limited visibility of trans subjects.”

X

^ Source 2: (https://www.colorado.edu/honorsjournal/sites/default/files/attached-files/hj2022-genderethnicstudies-hendriethetrap.pdf

#trans#trans women#transfem#transmasc#trans woman#trans man#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtiqa2s#queer#non binary#enby#mycology#magic mushies#microbiology#mold#60s psychedelia#lgbtqia#lgbtqia2s#lgbtqia2s+#myc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's this one thing that's been bothering us particularly badly as of late, and it's this recent surge in "normal people" going out of their way to mark all evildoers as "abnormal". It's far from the first time we encountered that kind of behavior, and we more or less get why so many people say things like "he's not a real christian" or "she's not a real mother" or "how sick do you have to be to do something like that" or "you have to be abnormal" and so on and so forth, especially when put in front of a shocking news of a particularly gruesome murder or something equally drastic.

It's uncomfortable, and hard to imagine yourself doing that, but you still see a person looking like any other, with all the outward features of a human just like you. I'm not really surprised, that when faced with someone that looks similar enough to them to count as a human, most people immediately separate themselves out by making up some sort of a "difference" major enough for them to be able to re-categorize this uncomfortably human-looking person as an inhumane monster. Completely outside of the realm of "normal people".

The problem is, that what that essentially does is create this assumption that harm is some sort of a symptom of "not being me enough syndrome" that ought to be treated in some way, or at least dealt with by means of isolation. This often involves throwing insults, accusations or otherwise asserting that the perpetrator must be mentally ill, or disabled, or an Arab or whatever is considered too far away from "normal"

On one hand, this is just another way normal people balance out the desire to be the only thing X in existence (something that we might as well call the "oneness perversion") with the need to recognize and react to any signs of something or someone unusual. Everyone is supposedly the same person, but depending on the degree of "deviation", weirdos like us either have a "sickness" that they believe they can "heal" (thus eliminating that pesky differentness) or don't even count as a human at all.

At the same time, doing this reassures the normals, that they will never have to assume responsibility for anything serious, because they're not "off enough" to do anything other than a minor, forgettable offense. And the way this interacts with both big events like the rise of fascism, with millions of people asserting that the fascists were all abnormal mental monsters from hell, and smaller more personal moments like "mommy loves you so she'd never do something like that" in response to us trying to tell her to stop doing something like that, is a major issue that could potentially result in yet another tragedy.

Unfortunately, the normals would have to acknowledge their capability to commit any harm imaginable and unimaginable, but most of them still seem to prefer comfort at our cost than any conscious effort to change and be a better person. And there's something really shitty about so many people immediately diagnosing all sorts of people from J.K.Rowling all the way to Adolf Hitler (admittedly it's not a particularly long way, but still) with all sorts of mental illnesses - schizophrenia, bpd, psychopathy, narcissism, even low libido and high libido for some reason.

This is really frustrating, because it's the everyday Joes of 20th century Germany that did the Holocaust. It's the standard view havers that radicalized so far right, that tried to do colonialism in Europe, and that were already okay with the concept enough to consider applying it to the "Wild East" as they called Eastern Europe in direct reference to the so called "Wild West" in America.

The serial killers and psychopaths and all the black characters that normals whiten themselves with were busy mentally breaking the fuck down from another day of burning the corpses of all the "abnormals" the nazis were exterminating on a mass scale. It's all wife-loving, dog-having, typical, everyday people that committed all of these atrocities, and we, the undesirables, were their primary targets of removal and eventually extermination. And it's high time the general public admits that and recognizes their own ability to do all evil, including the most disturbing and extreme of acts. If they can't do that, then we will all be doomed one day. Mind my words.

/Yui

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Id, Ego, Super-Ego

Chapter 2 - Utterson considers the unusual nature of Jekyll’s will. Seemed like ‘madness’, but now suggests ‘disgrace’. Utterson visits Dr. Lanyon hoping for fresh information. He learns nothing new about Hyde. Utterson dreams of Jekyll and Hyde. He begins to ‘haunt’ the street outside Hyde’s door hoping to see a reason for Jekyll’s link to him. The two men meet and, like the other witnesses, Utterson cannot explain his dislike for Hyde. Their conversation doesn’t reveal much. Utterson visits Jekyll, he isn’t there. Utterson considers Hyde to be ‘the ghost of some old sin, the cancer of some concealed disgrace’ returning to ruin him. Worries time is running out for Jekyll.

Can Utterson really be as innocent as he appears? We know he represses his natural instincts but know very little about his private life. He becomes obsessed with Hyde as the story continues. Mr Enfield. Imagery of the street lit up as if for a procession and empty as a church. Symbolism of an empty church?

Jekyll deliberately creates Hyde to behave ‘badly’ and get away with it. Jekyll wants to appear better than everyone else and he cannot reconcile his ‘loose’ morals.

Victorian man was conflicted with a sense of division between being rational and sensual; a public and private man. Contemporary society is more progressive; attitudes have shifted and we are more accepting thanks to civil rights and social justice movements. The desire for a more ‘just’ society has lead to the necessary creation of a new set of rules or ‘norms’. These rules have good intentions but consequences when broken.

Personal vs. Social Emotion Rachel Hewitt (2017) - What seem to be personal emotions are products of the time and place in which we live. Language ‘offers the clearest view of how cultural attitudes shape our personal experiences of feeling’. Before the 19th Century, different ideas of emotions and different ways of naming them. Appetites - relating to base desires (lust) Sentiments - seen as voluntary and associated with moral behaviour. The word emotion was related to movement or disturbance, usually of a riotous political nature. Some of this meaning is relevant today - emotional people are seen as out of control, less rational. English is fill of words relating to embarrassment - Discomfiture, awkwardness, humility, mortification, uneasiness, self-consciousness, shame. This relects the importance of propriety, decorum, politeness and respectability in English culture. ‘Emotion is... produced at the intersection between each person and the culture they inhabit.’ (Hewitt, 2017)

21st Century - shaming people.We hunt for people’s shameful secrets and clues to a secret inner evil. eg twitter responses. A cathartic alternative to social justice - we can say what we want to about people who say the wrong thing. Stevenson’s Victorian gentlemen think they’ve ‘civilized’ themselves out of feeling base emotions, but Enfield and the other want to kill Hyde. Stevenson uses ‘I gave a view halloa’ which is a hunting term used to announce that the fox has broken cover. This emphasises not only Hyde’s animalistic qualities, but the blood lust of his ‘hunters’. “Killing being out of the question, we... should make his name stink from one end of London to the other”. Shaming is a substitute for what they want to do. Sublimation - diverting a base sexual or biological urge into something more socially acceptable.

Sigmund Freud 1923 ‘Psychic apparatus’ of the mind. Id (’Es’) - Instincts Primitive, unorganized, emotional. The realm of the illogical (Storr, 1989). Governed by the ‘pleasure principle’. Represents the unconscious. Ego (’ich’) - Reality Represents the conscious mind and the ‘reality principle’. Able to defer gratification. ‘Mature’ and ‘reasonable’. ‘Acts as an intermediary between the id and the external world’ Superego (’Uber-ich’) - Morality Our internalisation of cultural rules. How we ought to behave. Usually works in opposition to the id.

Hyde represents ‘id’ but also exhibits ‘ego’ - acts to prevent capture by the police and consequent death. Hyde doesn’t have ‘superego’ - no morals to judge or shape his own behaviour.

Freud began his private psychiatric practice in 1886 (same year J&H was published) initially using hypnosis. Inspired by Europe’s most famous hypnotist - Dr. Charcot who became famous for hypnotising women with hysteria; the symptoms seemed to disappear under hypnosis. Hysteria - a particular set of physical symptoms with no physical cause. (eg. loss of speech, paralysis of a limb, muscle spasms.) Most sufferers were women.

Hysteria Hustvedt (2011) - Hysteria a ‘medical “trash can”’ - ‘diagnosed when no other cause could be found’. Variously blamed on a ‘wandering womb’, demonic possession, lesions of the nerves, or unexplained epidemics. In Chapter 9 - Hyde was ‘wrestling against the approaches of the hysteria’.

Freud saw the hypnotic experiments showing the power of the unconscious mind. Many patients seemed to develop a double personality under hypnosis. After Charcot’s death some patients admitted they were faking.

Freud and his colleague Josef Breuer invented a ‘talking cure’ called ‘psychoanalysis’. This aims to unearth unconscious desires and memories through ‘free association’ (the totally free, uncensored expression of thoughts and ideas.) and analysis of dreams. Freud theorised that repression of desires (especially as a child) could lead to fixations in later life. Patients recalling out loud the first instance they experienced a troubling symptom would cause the symptom to disappear.

Freud believed artists and writers had a special skill for sublimation. Artists were able to ‘avoid neurosis and perversion’ by playing out these fixations in their art.

William ‘Deacon’ Brodie Stevenson was fascinated by Brodie. Co-wrote a play about him in 1878 (pre J&H). Brodie was a cabinetmaker and town councillor by day and a burglar by night. Frequented taverns, had two mistresses and five illegitimate children.

From a Freudian perspective, the fact that Stevenson dreamt the story is even more significant. “[T]he dream is a fulfilled wish” (Freud, 1920) Freud divided dreams into: Manifest content - the remembered details of the dream Latent content - true meaning of the dream Dream-work - the mental processes by which repressed desires are made acceptable to the conscious mind by being disguised as manifest content.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serial Killers

Countess Erszebet Bathory was a breathtakingly beautiful, unusually well-educated woman, married to a descendant of Vlad Dracula of Bram Stoker fame. In 1611, she was tried - though, being a noblewoman, not convicted - in Hungary for slaughtering 612 young girls. The true figure may have been 40-100, though the Countess recorded in her diary more than 610 girls and 50 bodies were found in her estate when it was raided.

The Countess was notorious as an inhuman sadist long before her hygienic fixation. She once ordered the mouth of a talkative servant sewn. It is rumoured that in her childhood she witnessed a gypsy being sewn into a horse's stomach and left to die.

The girls were not killed outright. They were kept in a dungeon and repeatedly pierced, prodded, pricked, and cut. The Countess may have bitten chunks of flesh off their bodies while alive. She is said to have bathed and showered in their blood in the mistaken belief that she could thus slow down the aging process.

Her servants were executed, their bodies burnt and their ashes scattered. Being royalty, she was merely confined to her bedroom until she died in 1614. For a hundred years after her death, by royal decree, mentioning her name in Hungary was a crime.

Cases like Barothy's give the lie to the assumption that serial killers are a modern - or even post-modern - phenomenon, a cultural-societal construct, a by-product of urban alienation, Althusserian interpellation, and media glamorization. Serial killers are, indeed, largely made, not born. But they are spawned by every culture and society, molded by the idiosyncrasies of every period as well as by their personal circumstances and genetic makeup.

Still, every crop of serial killers mirrors and reifies the pathologies of the milieu, the depravity of the Zeitgeist, and the malignancies of the Leitkultur. The choice of weapons, the identity and range of the victims, the methodology of murder, the disposal of the bodies, the geography, the sexual perversions and paraphilias - are all informed and inspired by the slayer's environment, upbringing, community, socialization, education, peer group, sexual orientation, religious convictions, and personal narrative. Movies like "Born Killers", "Man Bites Dog", "Copycat", and the Hannibal Lecter series captured this truth.

Serial killers are the quiddity and quintessence of malignant narcissism.

Yet, to some degree, we all are narcissists. Primary narcissism is a universal and inescapable developmental phase. Narcissistic traits are common and often culturally condoned. To this extent, serial killers are merely our reflection through a glass darkly. More here gemtv serial

In their book "Personality Disorders in Modern Life", Theodore Millon and Roger Davis attribute pathological narcissism to "a society that stresses individualism and self-gratification at the expense of community ... In an individualistic culture, the narcissist is 'God's gift to the world'. In a collectivist society, the narcissist is 'God's gift to the collective'".

Lasch described the narcissistic landscape thus (in "The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an age of Diminishing Expectations", 1979):

"The new narcissist is haunted not by guilt but by anxiety. He seeks not to inflict his own certainties on others but to find a meaning in life. Liberated from the superstitions of the past, he doubts even the reality of his own existence ... His sexual attitudes are permissive rather than puritanical, even though his emancipation from ancient taboos brings him no sexual peace.

Fiercely competitive in his demand for approval and acclaim, he distrusts competition because he associates it unconsciously with an unbridled urge to destroy ... He (harbours) deeply antisocial impulses. He praises respect for rules and regulations in the secret belief that they do not apply to himself. Acquisitive in the sense that his cravings have no limits, he ... demands immediate gratification and lives in a state of restless, perpetually unsatisfied desire."

The narcissist's pronounced lack of empathy, off-handed exploitativeness, grandiose fantasies and uncompromising sense of entitlement make him treat all people as though they were objects (he "objectifies" people). The narcissist regards others as either useful conduits for and sources of narcissistic supply (attention, adulation, etc.) - or as extensions of himself.

Similarly, serial killers often mutilate their victims and abscond with trophies - usually, body parts. Some of them have been known to eat the organs they have ripped - an act of merging with the dead and assimilating them through digestion. They treat their victims as some children do their rag dolls.

Killing the victim - often capturing him or her on film before the murder - is a form of exerting unmitigated, absolute, and irreversible control over it. The serial killer aspires to "freeze time" in the still perfection that he has choreographed. The victim is motionless and defenseless. The killer attains long sought "object permanence". The victim is unlikely to run on the serial assassin, or vanish as earlier objects in the killer's life (e.g., his parents) have done.

In malignant narcissism, the true self of the narcissist is replaced by a false construct, imbued with omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. The narcissist's thinking is magical and infantile. He feels immune to the consequences of his own actions. Yet, this very source of apparently superhuman fortitude is also the narcissist's Achilles heel.

The narcissist's personality is chaotic. His defense mechanisms are primitive. The whole edifice is precariously balanced on pillars of denial, splitting, projection, rationalization, and projective identification. Narcissistic injuries - life crises, such as abandonment, divorce, financial difficulties, incarceration, public opprobrium - can bring the whole thing tumbling down. The narcissist cannot afford to be rejected, spurned, insulted, hurt, resisted, criticized, or disagreed with.

Likewise, the serial killer is trying desperately to avoid a painful relationship with his object of desire. He is terrified of being abandoned or humiliated, exposed for what he is and then discarded. Many killers often have sex - the ultimate form of intimacy - with the corpses of their victims. Objectification and mutilation allow for unchallenged possession.

Devoid of the ability to empathize, permeated by haughty feelings of superiority and uniqueness, the narcissist cannot put himself in someone else's shoes, or even imagine what it means. The very experience of being human is alien to the narcissist whose invented False Self is always to the fore, cutting him off from the rich panoply of human emotions.

Thus, the narcissist believes that all people are narcissists. Many serial killers believe that killing is the way of the world. Everyone would kill if they could or were given the chance to do so. Such killers are convinced that they are more honest and open about their desires and, thus, morally superior. They hold others in contempt for being conforming hypocrites, cowed into submission by an overweening establishment or society.

The narcissist seeks to adapt society in general - and meaningful others in particular - to his needs. He regards himself as the epitome of perfection, a yardstick against which he measures everyone, a benchmark of excellence to be emulated. He acts the guru, the sage, the "psychotherapist", the "expert", the objective observer of human affairs. He diagnoses the "faults" and "pathologies" of people around him and "helps" them "improve", "change", "evolve", and "succeed" - i.e., conform to the narcissist's vision and wishes.

Serial killers also "improve" their victims - slain, intimate objects - by "purifying" them, removing "imperfections", depersonalizing and dehumanizing them. This type of killer saves its victims from degeneration and degradation, from evil and from sin, in short: from a fate worse than death.

The killer's megalomania manifests at this stage. He claims to possess, or have access to, higher knowledge and morality. The killer is a special being and the victim is "chosen" and should be grateful for it. The killer often finds the victim's ingratitude irritating, though sadly predictable.

In his seminal work, "Aberrations of Sexual Life" (originally: "Psychopathia Sexualis"), quoted in the book "Jack the Ripper" by Donald Rumbelow, Kraft-Ebbing offers this observation:

"The perverse urge in murders for pleasure does not solely aim at causing the victim pain and - most acute injury of all - death, but that the real meaning of the action consists in, to a certain extent, imitating, though perverted into a monstrous and ghastly form, the act of defloration. It is for this reason that an essential component ... is the employment of a sharp cutting weapon; the victim has to be pierced, slit, even chopped up ... The chief wounds are inflicted in the stomach region and, in many cases, the fatal cuts run from the vagina into the abdomen. In boys an artificial vagina is even made ... One can connect a fetishistic element too with this process of hacking ... inasmuch as parts of the body are removed and ... made into a collection."

Yet, the sexuality of the serial, psychopathic, killer is self-directed. His victims are props, extensions, aides, objects, and symbols. He interacts with them ritually and, either before or after the act, transforms his diseased inner dialog into a self-consistent extraneous catechism. The narcissist is equally auto-erotic. In the sexual act, he merely masturbates with other - living - people's bodies.

The narcissist's life is a giant repetition complex. In a doomed attempt to resolve early conflicts with significant others, the narcissist resorts to a restricted repertoire of coping strategies, defense mechanisms, and behaviors. He seeks to recreate his past in each and every new relationship and interaction. Inevitably, the narcissist is invariably confronted with the same outcomes. This recurrence only reinforces the narcissist's rigid reactive patterns and deep-set beliefs. It is a vicious, intractable, cycle.

Correspondingly, in some cases of serial killers, the murder ritual seemed to have recreated earlier conflicts with meaningful objects, such as parents, authority figures, or peers. The outcome of the replay is different to the original, though. This time, the killer dominates the situation.

The killings allow him to inflict abuse and trauma on others rather than be abused and traumatized. He outwits and taunts figures of authority - the police, for instance. As far as the killer is concerned, he is merely "getting back" at society for what it did to him. It is a form of poetic justice, a balancing of the books, and, therefore, a "good" thing. The murder is cathartic and allows the killer to release hitherto repressed and pathologically transformed aggression - in the form of hate, rage, and envy.

But repeated acts of escalating gore fail to alleviate the killer's overwhelming anxiety and depression. He seeks to vindicate his negative introjects and sadistic superego by being caught and punished. The serial killer tightens the proverbial noose around his neck by interacting with law enforcement agencies and the media and thus providing them with clues as to his identity and whereabouts. When apprehended, most serial assassins experience a great sense of relief.

Serial killers are not the only objectifiers - people who treat others as objects. To some extent, leaders of all sorts - political, military, or corporate - do the same. In a range of demanding professions - surgeons, medical doctors, judges, law enforcement agents - objectification efficiently fends off attendant horror and anxiety.

Yet, serial killers are different. They represent a dual failure - of their own development as full-fledged, productive individuals - and of the culture and society they grow in. In a pathologically narcissistic civilization - social anomies proliferate. Such societies breed malignant objectifiers - people devoid of empathy - also known as "narcissists".

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“At the time, age eighteen, having been brought up in a hair-trigger society where the ground rules were – if no physically violent touch was being laid upon you, and no outright verbal insults levelled at you, and no taunting looks in the vicinity either, then nothing was happening, so how could you be under attack from something that wasn’t there? At eighteen I had no proper understanding of the ways that constituted encroachment. I had a feeling for them, an intuition, a sense of repugnance for some situations and some people but I did not know intuition and repugnance counted, did not know I had a right not to like, not to put up with, nobody and everybody coming near.”

“Indeed, his mental aberration, as diagnosed by the community, was that he expected women to be doughty inspirational, even mythical, supernatural creatures. We were supposed also to altercate with him, more or less too, to overrule him, which was all very unusual but part of his unshakeable women rules. If a woman wasn’t being mythical and so on, he’d try to nudge things in that direction by himself becoming slightly dictatorial towards her. By this he was discomfited but had faith that once she came to with the help of his improvised despotism, she would remember who she was and indignantly reclaim her something beyond the physical once again.”

“There would be injustices too, thought the traditional women, those big ones, the famous ones, the international ones – witch-burnings, footbindings, sutee, honour killings, female circumcision, rape, child marriage, retributions by stoning, female infanticide, gynaecological practices, maternal mortality, domestic servitude, treatment as chattels, as breeding stock, as possessions, girls going missing, girls being sold […] But no. Not that…Instead these local issue women spoke of homespun, personal, ordinary things, such as walking down the street and getting hit by a guy, any guy, just as you’re walking by, just for nothing, just because he was in a bad mood and felt like hitting you or because some soldier from ‘over the water’ had given him a hard time so now it was your turn to have the hard time so he hits you. Or having your bum felt as you’re walking along. Or having loud male comment passed upon your physical characteristics as you’re passing. Or getting molested in the snow under the guise of some nice friendly snowfight […] Then there was menstruation and how it was seen as an affront to being a person. And pregnancy too, how that couldn’t be helped but all the same, an affront to being a person. Then the spoke about ordinary physical violence as if it wasn’t just normal violence, also speaking of how getting your blouse ripped off in a physical fight, or your brassiere ripped off in a physical fight, or getting felt up in a fight wasn’t violence that was physical so much as it was sexual even if, they said, you were supposed to pretend the bra and the breast had been incidental to the physical violence and not the disguised point of the physical violence, making it sexual violence all along.”

“Of course I knew I was angry. Of course I knew I was frightened, that I had no doubt my body, to me, was brimming with natural reaction. At first I could feel this reaction which confirmed I was alive, that I was in there, inside my body, experiencing this under-the-surface turbulence. Thing was though, before I’d gained the understanding of what was happening, my seemingly flattened approach to life became less pretence and more and more real as time went on. As first emotional numbness set in. Then my head, which initially had reassured with, ‘Excellent. Well done. Successfully am I fooling them in that they do not know who I am or what I’m thinking or what I’m feeling’, now began itself to doubt I was even there. ‘Just a minute,’ it said. ‘Where is our reaction? We were having a privately expressed reaction but now we’re not having it. Where is it?’ Thus my feelings stopped expressing. Then they stopped existing. And now this numbance from nowhere had come so far on its development that along with others in the area finding me inaccessible, I, too, came to find me inaccessible. My inner world, it seemed, had gone away.”

About reading while walking:

‘It’s creepy, perverse, obstinately determined,‘ went on longest friend. ‘It’s not as if, friend,’ she said, ‘this were a case of a person glancing at some newspaper as they’re walking along to get the latest headlines or something. It’s the way you do it – reading books, whole books, taking notes, checking footnotes, underlining passages as if you’re at some desk or something, in a little private study or something, the curtains closed, your lamp on, a cup of tea beside you, essays being penned – your discourse, your lucubrations. It’s disturbing. It’s deviant. It’s optical illusional. Not public-spirited. Not self-preservation. Calls attention to itself and why –with enemies at the doors, with the community under siege, with us all having to pull together – would anyone want to call attention to themselves here?’

‘For all your so called knowledge of the world, how come you don’t know that?’ I didn’t know what ma meant by my knowledge of the world. My knowledge of the world consisted of fucking hell, fucking hell, fucking hell which didn’t lend itself to detail, the detail really being those words themselves.”

‘In the name if God!’ She cried, ‘Are they correct? Is everybody correct? Have you been fecundated by him, by that renouncer, that “top wanted list” clever man, the false milkman?’ ‘What?’ I said, for it had been singular, that word she’d used and genuinely for a moment I had no clue what she meant by it. ‘Imbued by him?’ she elaborated. ‘Engendered in. Breeded in. Fertilised, vexed, embarrassed, sprinkled, caused to feel regret, wished not to have happened - dear God, child, do I have to spell it out?’ Well why didn’t she spell it out? Why couldn’t she just say pregnant? But this was like ma. It wasn’t as if I hadn’t enough on my plate, without having to take time out from poisoning - which still I hadn’t realized was poisoning – to guess her latest removed remark. She didn’t stay on difficult pregnancies either, for ma could give herself horror stories one right after the other. Next came abortions and I had to guess them also, from ‘vermifuge, pennyroyal, Satan’s apple, premature expulsion, being failed in the course of coming into being’…”

0 notes

Note

The Sleepaway Camp movies are always movies I flip-flop on, the first in particular has a kind of grimy fetishy feel you dont see in the slashers of that era, sickening in an interesting way. And yet you have that final image being shot in such a brilliant slow pan, but its message to the audience is disgusting... A weirdly complex series in retrospect

*spoiler alert* i guess

yeah, that first movie is pretty uncomfortable. i mean, the truth is that i really like it. i’m impressed with the unusual casting of actual greasy awkward teenagers of varying ages, which adds to the movie’s visceral punch and takes it further outside the realm of barely legal fantasy than slashers tend to go. there’s something gritty and depressing about it, in spite of its being occasionally way over the top, as in the case of aunt martha. and of course, the concluding sequence is one of my favorites in all of horror cinema; it has a dreamlike nature, with angela’s feral fright wig and twisted posture, and an unnatural half-frozen quality, all of which i realize is necessary to accomplish the special effect, but i think this actually makes the scene more horrifying than it might have been if it were more “realistic”. but yeah, unavoidably, it’s virulently transphobic. (in the second movie, they make a big point right at the very beginning about how angela got a sex change while institutionalized and is now a “real” woman, and i don’t really know what to say about that, i just wanted to mention it because i think it’s a totally weird thing to insist on) it operates in the grand tradition of PSYCHO, which...at least the shrink’s “explanation” at the end of PSYCHO is universally regarded as ludicrous. there’s a touch of drag in TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE too, but it’s harder to lock on to amid the rest of the chaos and perversion unless you’re specifically interested. i also rewatched DRESSED TO KILL recently, and that one is really difficult; like, yeah, we all know that depalma is obsessed with hitchcock, but this PSYCHO retread is so knowing that it feels like...he should just know better, than to introduce all of this insulting psychobabble and “expert” diagnoses of transfolk being totally pathological. it takes a movie that’s fun and stylish and ridiculous, and thrusts it into a mire of poisonous theory that’s a real buzz kill. my basic affection for all of the named movies says a lot about how i tend to prioritize artistry over social consciousness on the whole, so i’m not trying to hide or even apologize for that...but, you know, i’m not totally blind.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The truth about anxiety – without it we wouldn’t have hope

In a world so full of uncertainty it’s little wonder so many of us feel stressed. But understanding it can change how you feel. Why do so many people these days seem so stressed out and anxious? It’s a common question, among mental health professionals and laypeople alike, but there’s a case to be made that it’s exactly upside down. How come there’s anyone whoisn’t paralysed by anxiety, every hour of every day? After all, anxiety thrives in conditions of uncertainty – and nowadays the world is full of potential threats we don’t fully understand and can’t control.

Most of us just have to take it on trust that planes won’t fall out of the sky, or that the milk in our fridge won’t give us listeria. Sudden, unpredictable movements in the global financial system threaten to ruin anyone’s livelihood at any moment; plus now we have all the many unknowns around Brexit, an unstable liar in charge of America’s nuclear codes, and the omnipresent spectre of climate change. And as if all that weren’t enough, we spend our days marinating in an online environment designed to stoke panic about any remaining threats we might have been managing to ignore.

Some definitions may help here. “Stress”, as psychologists tend to use it, means an immediate response to an external pressure, and a moderate amount can actually be a good thing: totally unstressed people never revise for exams, or meet work deadlines. In most everyday contexts, when the external pressure stops, so does the stress. Which means that by far the simplest way to deal with stress, whenever possible, is to deal with whatever’s bothering you head on – to tackle the difficult piece of work, to talk to the friend you’ve fallen out with – or, failing that, to distance or distract yourself from its source. (Persistent and chronic stress requires a different approach.)

Get Society Weekly: our newsletter for public service professionals

Read more

But anxiety is a particular kind of internal response to stress, and it’s frequently far more fraught. As the Australian author Sarah Wilson points out in her combined memoir and anxiety self-help manual, First, We Make the Beast Beautiful, the problem isn’t simply that there are a lot of reasons to be anxious. It’s also that, perversely, society actually rewards certain anxious behaviours, such as being frenetically busy and driven – while the “reward” for managing to free yourself from anxiety might be a reputation for laziness, complacency, or showing insufficient concern about the state of the world. Then there’s the fact that anxiety is self-reinforcing: once you’re feeling anxious, you’re primed to seek further things to feel anxious about – including, as if that vicious circle weren’t frustrating enough, your anxiety itself.

Anxiety, at root, isn’t a bizarre psychological anomaly, but a fundamental aspect of human functioning

“Anxiety”, of course, is also the name for a family of official psychological disorders. But it’s a condition that makes it unusually clear that the line between “mental illness” and “ordinary human distress” is a subjective one, dependent as much on cultural conventions as on science. The main reason “generalised anxiety disorder” is so much more prevalent now is that it was only defined as a disorder in psychiatry’s bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in 1980. (If you feel “keyed up or on edge”, or have “difficulty concentrating”, it’s possible you qualify.) And one main reason it surged from 2001 onwards was a concerted media push by GlaxoSmithKline, after it received US approval to market its antidepressant Paxil (Seroxat in the UK) in the treatment of anxiety. “Local newscasts around [the United States] reported that as many as 10 million Americans suffered from an unrecognised disease,” the journalist Brendan Koerner has written. “Viewers were urged to watch for the symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, irritability, muscle tension, nausea, diarrhoea, and sweating …”

To be clear, none of this is to suggest that those with a diagnosed anxiety disorder don’t have a real illness, or that medication isn’t often part of the solution: “The basic premise for an anxiety disorder, or when anxiety becomes a clinical problem, is when anxiety controls our life, rather than us being able to control our anxiety,” says Robert Edelmann, emeritus professor of forensic and clinical psychology at the University of Roehampton. But it’s also a reminder that anxiety, at root, isn’t a bizarre psychological anomaly, but a fundamental aspect of human functioning. The problem, explains the psychology writer James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, is that it’s a response evolution bequeathed us for a setting radically different from today’s.

All anxiety contains a kernel of good news: you wouldn’t feel anxious if there weren’t the chance of things going well

Prehistoric humans lived in an “immediate-return environment”, as other mammals still do: their moment-to-moment choices mattered because of the immediate difference they made. You saw a predator and felt a surge of anxiety, which motivated you to evade it. Or you felt dangerously hungry, and anxiety focused your attention on quickly finding food. Once the threat was resolved, the anxiety would evaporate. But modern humans live in a “delayed-return environment”. We get paid for our work at the end of the week or month; we study for educational qualifications that take years. When we save money – or don’t – the consequences might not be felt for decades. And so the anxiety has nowhere to go. Instead, it accumulates and curdles.

Advertisement

This helps explain why national and international news events, such as Brexit or the election of Donald Trump, are such a widespread source of personal anxiety, including of the clinical kind. Some people – undocumented immigrants in Trump’s America, for example – are affected in direct, unambiguous ways. But even if you ultimately won’t be, you’ll have no way of knowing that for some time. Moreover, it often feels like there’s nothing you can do in response – no equivalent to the prehistoric hunter-gatherer’s decision to start running away, or go looking for food. When no constructive action seems possible, we resort to worry and rumination, which feel somehow constructive, even though they aren’t. One reaction to the anxiety of being immersed in a 24-hour news cycle “is that people try to find out more information, because anxiety is about a lack of control and they believe that having more information will make them feel more in control”, says the American therapist Lori Gottlieb, author of the forthcoming book Maybe You Should Talk to Someone. “But it doesn’t – it just makes people feel more anxious.”

Living in the moment? Good - but don’t forget the past or future

Read more

This is why most non-pharmaceutical solutions to anxiety, whatever its cause, involve the limited and realistic exertion of control: figuring out what constructive actions you can take, and taking them, while refraining from struggling to control things you can’t, which is a recipe for additional anxiety. (This is the “dichotomy of control”, a distinction dating to the Stoics of ancient Greece and Rome.) You can’t personally guarantee a comfortable retirement, or long-term physical health, let alone the optimal relationship between Britain and the rest of Europe. But you can calculate what you can afford to save, and track your saving. You can exercise a few times a week, and eat more leafy greens. You can take local, concrete political action. Whether or not you end up achieving your desired goal, your anxiety levels will almost certainly fall.

Finally, it’s worth recognising – as the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaardobserved in The Concept of Anxiety back in 1844 – that all anxiety contains a kernel of good news: you wouldn’t feel anxious in the first place if you had no freedom, and if there weren’t at least the possibility of things turning out well. “One would have no anxiety if there were no possibility whatever,” wrote the psychologist Rollo May, paraphrasing Kierkegaard. If you knew with absolute certainty that life from now on would bring only failure and defeat, you might well be depressed, but you wouldn’t feel on edge. Anxiety is the experience of knowing that life might bring success, fulfilment and joy, combined with the fear that you don’t know how to ensure that’s what will happen. And while severe anxiety can certainly be a debilitating problem, demanding treatment, some sense of uncertainty about the future is surely part of what makes life worth living. If you ever actually managed to rule out the potential for any nasty surprises, you’d find that you’d ruled out the possibility of any good ones, too.

0 notes

Link

One of the most striking things about Brett Kavanaugh’s Senate hearing last Thursday was how quickly the male Republican senators dismissed everything they heard from Christine Blasey Ford, the woman accusing Kavanaugh of sexual assault.

Ford sat before the entire country and calmly laid out the details of her alleged assault in excruciating detail. It was as convincing as it was painful, and the all-male Republican panel sat silently through most of it.

And then came Kavanaugh.

His testimony was the polar opposite of Ford’s. He was angry, loud, and openly defiant. “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit,” he fumed. “This is a circus!”

The strategy paid off. Inspired by Kavanaugh’s rage, the Republicans spent most of their time apologizing to him. He became the victim, and the hearing was suddenly about his pain and his struggle.

Here’s a question worth asking: if the tables were reversed, would Ford — or any woman — be rewarded in this way for expressing her rage? Probably not. Anger works for men in ways it doesn’t for women, and the Kavanaugh hearing was an unusually clear example of this.

A new book by Rebecca Traister, written long before the hearing last week, has a lot to say about why male and female anger plays so differently in our culture. Titled Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, Traister details the long history of female rage in this country, showing how it’s often mocked or caricatured but also how it has ignited many movements for social progress, including the early suffragist struggle and the more recent #MeToo movement.

I spoke to Traister last week, just before Ford and Kavanaugh testified in front of the Senate. We discussed the roots of female fury in America and what happens when it’s finally unleashed in the political sphere. I also asked her what the #MeToo movement and Kavanaugh’s nomination reveal about this cultural moment.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

You speak of women’s anger as both catalytic and problematic. What does it catalyze, and for whom is it problematic?

Rebecca Traister

It could be catalytic and problematic for the very same people. It is catalytic because of its ability to communicate shared frustration over injustice or a need to resist some injustice, and then once you have the communicative part, you can get to the mobilizing and action part.

At the same time, all that rage can be problematic because it’s hard to contain, hard to direct. This is true of the women’s movement, but also of every social movement. There are always internal frustrations within a movement that can split it into factions and undercut solidarity. So rage is powerful in terms of setting things in motion, but if it boils over, it can destroy a movement from the inside.

“People in power have assumed that they can behave in certain ways and get away with it”

Sean Illing

Anger works for men in ways it doesn’t for women, and we — as a culture — cater to male rage and often punish women for expressing their rage. How do you make sense of this in the book?

Rebecca Traister

Look at the 2016 presidential election. On the one hand, we had two very different candidates, with two very different ideologies, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, and they were understood to be successful in part because they were able to channel rage so effectively. It may have been rage over different things, but it was rage all the same. And they were applauded for this, for tapping into the frustrations and passions of their supporters. It was seen as a political skill, something almost noble.

This wasn’t true or possible for Hillary Clinton. To be honest, Clinton is not rhetorically gifted and not great at conveying anger, but almost every time she appeared to get angry or upset, she was criticized for it. It’s harder for women to traffic in anger without being punished, because we’re conditioned to avoid being publicly angry, and we’re told from birth that anger makes us unlikable and unserious. So we avoid it. And every time Clinton was called “shrill,” we were reminded of this.

Sean Illing

And yet here we are, in this moment, where women are getting more vocal and more comfortable expressing their rage, and who knows what might become of that. Do you think there’s something almost perversely beautiful about this moment, about the urgency of the struggle and the threat?

Rebecca Traister

There are different kinds of incentives in place to keep women from taking seriously the anger of other women, and one of the things about the past couple of years has been the insistence on staying angry, and this has come as a surprise to me. Even as I was writing this book, I kept thinking there would be this surge and that it would fade in a few weeks or so. But it hasn’t gone away, and it’s incredible.

And we’re watching a Supreme Court nomination being actively and crucially disrupted by the allegations of sexual misconduct and sexual abuse. I’m not sure that would have happened without the #MeToo movement preceding it. So all of this is producing political results, and I’m thankful for that.

I’m also encouraged by teachers strikes across the country and the activists who protested the health care repeal and all the women we’re seeing running for Congress. So it’s beautiful to see this anger translate into real political outcomes and not just fade away into nothingness. Women are refusing to just let their rage go, and that’s remarkable to watch.

“Political fury is baked into this country’s founding”

Sean Illing

I think a lot about how we describe different kinds of oppression, how some forms of oppression are easier to diagnose, easier to criticize than others. I wonder if you think it’s more difficult to talk about the oppression of women because they’re a majority and not a minority, which seems counterintuitive to the way we usually think of oppression.

Rebecca Traister

Absolutely, and it’s such an interesting question. You can think about this on a number of levels, but I’ll just focus on the personal. Every woman, across racial and class lines, has men in her personal and professional life, and her resistance to gender inequities is a kind of challenge to the dynamics of all of these relationships. If she stands her ground, there are consequences. It can alter these relationships.

One of the costs women incur when they push for these changes is that they get blamed, not incorrectly, for disturbing these bonds. During the second wave of feminism, you saw a huge spike in divorce rates, for example. That was a direct consequence of the political struggle.

I hear stories all the time from women today who have become politicized in the last two years and their romantic relationships are changing as a result. We’re trying to change the rules in the middle of a game we’re all a part of, because we’ve all been raised in an unequal society, and there’s no way to change that without paying a price.

But yeah, the fact that women are a majority, and the inequities we’re contesting are so pervasive and internalized, makes this fight both more difficult and disruptive.

Sean Illing

Speaking of disruptions, we’re having this conversation against the backdrop of Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation, which has been derailed by allegations of sexual assault and sexual misconduct. How does this ongoing saga align with the story you’re telling in this book?

Rebecca Traister

This feels like a catalytic moment to me. People in power have assumed that they can behave in certain ways and get away with it. We have active examples of that. For example, our sitting president, despite being accused by multiple people of sexual assault in the days before the election, won anyway. We have certain assumptions in this country that you can participate in acceptable forms of abuse and it will not interfere with your life, will not undercut your political power.

And we’re told all the time that our stories don’t count — the kind of stories Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez told about Brett Kavanaugh, for example. And we don’t tell them because we know that we’ll be attacked as unreliable. But I was deeply moved by the fact that Ramirez, who says Kavanaugh exposed himself to her when they were freshmen at Yale, admitted to being drunk when it happened. That’s not the story we’re encouraged to tell, but it’s true and it happened and she said it.

“It’s harder for women to traffic in anger without being punished, because we’re conditioned to avoid being publicly angry”

Sean Illing

In the book, you also talk about some of the anger that women feel toward other women, especially white women, who sometimes shut off or dial down their anger at the expense of other women. I mention this because I think it touches a core problem every social justice movement encounters: the apathy of the privileged.

Rebecca Traister

The people who can afford to be apathetic are invested in the continuation of a power structure. For example, we shouldn’t be surprised that 53 percent of white women voted for Donald Trump. White women have voted for Republican candidates for a long time, even though those candidates represented the continuation of a capitalist patriarchal power structure. Fifty-six percent voted for Romney over Obama in 2012, so 53 percent is actually an improvement.

So white women support the system because they believe they derive benefits from it. Even though many of them are oppressed in various ways, their proximity to power — and their attachment to those who benefit directly from it — makes them less likely to challenge the system. I think that’s always been the case.

Sean Illing

So what does victory, right now in this moment, look like?

Rebecca Traister

Obviously, elections matter. But it’s not just about the midterms or the next presidential election. This is a long-term movement, and like every long-term movement, it will take decades of work.

For example, there are a lot of women running for Congress right now, and that’s great, but it’s not just about women candidates. How many of them are actually going to win? I don’t know the answer to that, but it matters. And it’s also about what it will mean to bring women into the electoral system as activated citizens.

We’re seeing women run and canvass and fundraise and volunteer in ways we haven’t seen before, and many of them were activated by the Women’s March — that was the first time they ever protested. When you bring new people into the process like that, things can happen.

What are the long-term effects of all this? I’m not sure, but I know some of the things I’d like to see. I’d like to see Brett Kavanaugh denied a seat on the Supreme Court. I would like to not confirm someone who will overturn Roe v. Wade or gut voting rights or further diminish collective bargaining rights. I would like to see Democrats take back the House, the Senate, and, as soon as possible, the White House. I would like to see a $15 minimum wage and a federal jobs program and much stronger social safety nets.

These changes would fundamentally alter the power structure when it comes to gender, race, and economic inequality. But all of this won’t happen on November 6, no matter how the elections go. Again, this is a long-term struggle and we’re just at the beginning of the latest cycle of change.

This project will take the rest of our lives.

Original Source -> Rebecca Traister on the revolutionary power of female rage

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

"Why Did a Federal Judge Sentence a Terminally Ill Mother to 75 Years for Health Care Fraud?"

The question in the title of this post is the headline of this recent law.com article about a notable (and notably harsh) federal sentencing. Here are some of the details, with some commentary to follow:

A federal judge in Texas sentenced a terminally ill woman to 75 years in prison last month for bilking Medicare — an apparent record sentence for the U.S. Department of Justice for health care fraud.

Marie Neba, 53, of Sugar Land, Texas, was sentenced by U.S. District Judge Melinda Harmon of the Southern District of Texas on eight counts stemming from her role in a $13 million Medicare fraud scheme. Neba, the owner and director of nursing at a Houston home health agency, was convicted after a two-week jury trial last November. At the sentencing on Aug. 11, the government recommended a 35-year imprisonment, said Michael Khouri, who started representing Neba as her private attorney shortly after the trial...

The unusually lengthy sentence for what health care fraud legal experts call a relatively routine case has them scratching their heads, even in this recent era of the federal government’s crackdown on health care fraud. Neba, the mother of 7-year-old twin sons, was diagnosed in May with stage IV metastatic breast cancer that has spread to her lungs and bones, according to Khouri, who has filed an appeal of the conviction and the sentence. She currently is receiving chemotherapy treatments and is in custody in a federal detention center. “Marie Neba is a mother, a wife and a human being who is dying. If there is any defendant that stands before the court that deserves a below-guideline sentence … it’s this woman that stands before you,” Khouri argued before Harmon at the sentencing hearing, according to a transcript recently obtained by ALM....

Patrick Cotter, a former federal prosecutor who heads the government interaction and white-collar practice group at Greensfelder, Hemker & Gale in Chicago, said given the circumstances, he would have expected Neba to receive a sentence of several years in prison. “Nothing is surprising in that she went to jail and not for six months,” he said. “But how you get anything close to 75 years is beyond me and makes no sense at all. In 35 years, I have never heard of the government’s [prison term] recommendation being doubled by the judge, particularly when the government is asking for a tough sentence anyway.”

Gejaa Gobena, a litigation partner at Hogan Lovells and former chief of the DOJ Criminal Division’s Health Care Fraud Unit, concurred. “We prosecuted hundreds of cases and never had a sentence approaching anywhere near this,” Gobena said.

Legally, the answer to how the long sentence came about is not that difficult: Harmon, applying several enhancements under the federal sentencing guidelines, imposed the statutory maximum prison term on each charge, and then ran them consecutively. “I am not a heartless person. I think I am not. I hope I am not,” Harmon told Neba before announcing the sentence. “It must be a terrible experience that you are going through, Ms. Neba, and I don’t want you to think that by sentencing you to what I am going to sentence you to that I’m trying to heap more difficulties on you because I am not. … It’s just the way the system works, the way the law works. You have been found guilty of a number of counts by a jury, and this is what happens.”

Even so, historically, the case is highly unusual, breaking the previous record by 25 years. Since a pair of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in December 2007 that reaffirmed that the federal sentencing guidelines are merely advisory, federal trial judges have much greater latitude to impose what they think are appropriate sentences, even if the guidelines call for higher or lower sentences. The longest health care fraud sentence prior to Neba’s came in 2011, when Lawrence Duran, the owner of a Miami-area mental health care company, was sentenced to 50 years for orchestrating a $205 million Medicare scheme that defrauded vulnerable patients with dementia and substance abuse. The next longest? Forty-five years in 2015 for a Detroit doctor who gave chemotherapy to healthy patients, whom federal prosecutors then called the “most egregious fraudster in the history of this country.”

According to court documents, Neba, from 2006 to 2015, conspired with others to defraud Medicare by submitting more than $10 million in false claims for home health services provided through Fiango Home Healthcare Inc., owned by Neba and her husband and co-defendant, Ebong Tilong. Using that money, Neba paid illegal kickbacks to patient recruiters for referrals and to Medicare beneficiaries who allowed Fiango to use their Medicare information to bill for home health services that were not medically necessary nor provided, and, all told, received $13 million in ill-gotten Medicare payments, the documents said.

Neba was convicted of one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud, three counts of health care fraud, one count of conspiracy to pay and receive health care kickbacks, one count of payment and receipt of health care kickbacks, one count of conspiracy to launder monetary instruments and one count of making health care false statements.

Four co-defendants, including Tilong, have pleaded guilty in the case. He is scheduled to be sentenced on Oct. 13....

Harmon, through her case manager, declined to comment on the case. The transcript, however, reveals several factors that influenced her decision to impose the lengthy prison term, including: “Most importantly,” Neba’s sentencing guideline range of life imprisonment (though Harmon was proscribed by statutory maximums from imposing a life sentence);..... Neba’s attempt to obstruct justice by telling a co-defendant, before arraignment in the federal courthouse, “to keep to her story,” specifically “not to tell anybody that she, [the co-defendant], was paying the patients.”

Neba’s decision to go to trial on the charges, rather than plead guilty and provide some sort of government assistance, also played a role in her sentence. Had she pleaded guilty to one or more of the charges “at the very beginning without obstruction of justice,” and received the highest credit for cooperation for doing so, Neba’s sentencing guideline range would have been 14.5 years, federal prosecutor William Chang told Harmon during the hearing. “Had the same thing happened and she received no [credit] whatsoever, it would be 21.8 years,” he added. “If she had gone to trial and been convicted, but no obstruction of justice, the sentence would have been 30 years on the calculation of the guidelines. So, we want the court to understand the United States’ principal position for what it seeks.”

Khouri, Neba’s attorney, said he plans to challenge on appeal the manner in which the sentencing guideline range was calculated and argue, among other matters, that the sentence is excessive.

I have quoted so much of this press report because the more details it provides, the more perverse the entire federal sentencing seems along with the perversity of this particularly extreme sentence. For starters, though we supposedly have a federal sentencing system designed to sentence a defendant based principally on the seriousness of her offense, this defendant's guideline ballooned from less than 15 years imprisonment to life imprisonment essentially because she put the government to its burden of proof at a trial and said the wrong thing to a co-defendant.

Trial penalty guideline calculations notwithstanding, now that the guidelines are advisory, a prosecutor and a judge would need to be able to justify such an extreme functional LWOP sentence based on all the 3553(a) statutory factors. No matter how seriously one regards health care fraud, I cannot fully understand how any of these factors (save the guideline range) can support this extreme sentence in this not-so-extreme case of fraud. If reasonableness review has any substance whatsoever, and if the facts in this article are accurate, it seem clear to me that this sentence ought to be found substantive unreasonable.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8247011 http://sentencing.typepad.com/sentencing_law_and_policy/2017/09/why-did-a-federal-judge-sentence-a-terminally-ill-mother-to-75-years-for-health-care-fraud.html via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

"Why Did a Federal Judge Sentence a Terminally Ill Mother to 75 Years for Health Care Fraud?"

The question in the title of this post is the headline of this recent law.com article about a notable (and notably harsh) federal sentencing. Here are some of the details, with some commentary to follow:

A federal judge in Texas sentenced a terminally ill woman to 75 years in prison last month for bilking Medicare — an apparent record sentence for the U.S. Department of Justice for health care fraud.

Marie Neba, 53, of Sugar Land, Texas, was sentenced by U.S. District Judge Melinda Harmon of the Southern District of Texas on eight counts stemming from her role in a $13 million Medicare fraud scheme. Neba, the owner and director of nursing at a Houston home health agency, was convicted after a two-week jury trial last November. At the sentencing on Aug. 11, the government recommended a 35-year imprisonment, said Michael Khouri, who started representing Neba as her private attorney shortly after the trial...

The unusually lengthy sentence for what health care fraud legal experts call a relatively routine case has them scratching their heads, even in this recent era of the federal government’s crackdown on health care fraud. Neba, the mother of 7-year-old twin sons, was diagnosed in May with stage IV metastatic breast cancer that has spread to her lungs and bones, according to Khouri, who has filed an appeal of the conviction and the sentence. She currently is receiving chemotherapy treatments and is in custody in a federal detention center. “Marie Neba is a mother, a wife and a human being who is dying. If there is any defendant that stands before the court that deserves a below-guideline sentence … it’s this woman that stands before you,” Khouri argued before Harmon at the sentencing hearing, according to a transcript recently obtained by ALM....

Patrick Cotter, a former federal prosecutor who heads the government interaction and white-collar practice group at Greensfelder, Hemker & Gale in Chicago, said given the circumstances, he would have expected Neba to receive a sentence of several years in prison. “Nothing is surprising in that she went to jail and not for six months,” he said. “But how you get anything close to 75 years is beyond me and makes no sense at all. In 35 years, I have never heard of the government’s [prison term] recommendation being doubled by the judge, particularly when the government is asking for a tough sentence anyway.”

Gejaa Gobena, a litigation partner at Hogan Lovells and former chief of the DOJ Criminal Division’s Health Care Fraud Unit, concurred. “We prosecuted hundreds of cases and never had a sentence approaching anywhere near this,” Gobena said.

Legally, the answer to how the long sentence came about is not that difficult: Harmon, applying several enhancements under the federal sentencing guidelines, imposed the statutory maximum prison term on each charge, and then ran them consecutively. “I am not a heartless person. I think I am not. I hope I am not,” Harmon told Neba before announcing the sentence. “It must be a terrible experience that you are going through, Ms. Neba, and I don’t want you to think that by sentencing you to what I am going to sentence you to that I’m trying to heap more difficulties on you because I am not. … It’s just the way the system works, the way the law works. You have been found guilty of a number of counts by a jury, and this is what happens.”

Even so, historically, the case is highly unusual, breaking the previous record by 25 years. Since a pair of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in December 2007 that reaffirmed that the federal sentencing guidelines are merely advisory, federal trial judges have much greater latitude to impose what they think are appropriate sentences, even if the guidelines call for higher or lower sentences. The longest health care fraud sentence prior to Neba’s came in 2011, when Lawrence Duran, the owner of a Miami-area mental health care company, was sentenced to 50 years for orchestrating a $205 million Medicare scheme that defrauded vulnerable patients with dementia and substance abuse. The next longest? Forty-five years in 2015 for a Detroit doctor who gave chemotherapy to healthy patients, whom federal prosecutors then called the “most egregious fraudster in the history of this country.”

According to court documents, Neba, from 2006 to 2015, conspired with others to defraud Medicare by submitting more than $10 million in false claims for home health services provided through Fiango Home Healthcare Inc., owned by Neba and her husband and co-defendant, Ebong Tilong. Using that money, Neba paid illegal kickbacks to patient recruiters for referrals and to Medicare beneficiaries who allowed Fiango to use their Medicare information to bill for home health services that were not medically necessary nor provided, and, all told, received $13 million in ill-gotten Medicare payments, the documents said.

Neba was convicted of one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud, three counts of health care fraud, one count of conspiracy to pay and receive health care kickbacks, one count of payment and receipt of health care kickbacks, one count of conspiracy to launder monetary instruments and one count of making health care false statements.

Four co-defendants, including Tilong, have pleaded guilty in the case. He is scheduled to be sentenced on Oct. 13....

Harmon, through her case manager, declined to comment on the case. The transcript, however, reveals several factors that influenced her decision to impose the lengthy prison term, including: “Most importantly,” Neba’s sentencing guideline range of life imprisonment (though Harmon was proscribed by statutory maximums from imposing a life sentence);..... Neba’s attempt to obstruct justice by telling a co-defendant, before arraignment in the federal courthouse, “to keep to her story,” specifically “not to tell anybody that she, [the co-defendant], was paying the patients.”

Neba’s decision to go to trial on the charges, rather than plead guilty and provide some sort of government assistance, also played a role in her sentence. Had she pleaded guilty to one or more of the charges “at the very beginning without obstruction of justice,” and received the highest credit for cooperation for doing so, Neba’s sentencing guideline range would have been 14.5 years, federal prosecutor William Chang told Harmon during the hearing. “Had the same thing happened and she received no [credit] whatsoever, it would be 21.8 years,” he added. “If she had gone to trial and been convicted, but no obstruction of justice, the sentence would have been 30 years on the calculation of the guidelines. So, we want the court to understand the United States’ principal position for what it seeks.”

Khouri, Neba’s attorney, said he plans to challenge on appeal the manner in which the sentencing guideline range was calculated and argue, among other matters, that the sentence is excessive.

I have quoted so much of this press report because the more details it provides, the more perverse the entire federal sentencing seems along with the perversity of this particularly extreme sentence. For starters, though we supposedly have a federal sentencing system designed to sentence a defendant based principally on the seriousness of her offense, this defendant's guideline ballooned from less than 15 years imprisonment to life imprisonment essentially because she put the government to its burden of proof at a trial and said the wrong thing to a co-defendant.

Trial penalty guideline calculations notwithstanding, now that the guidelines are advisory, a prosecutor and a judge would need to be able to justify such an extreme functional LWOP sentence based on all the 3553(a) statutory factors. No matter how seriously one regards health care fraud, I cannot fully understand how any of these factors (save the guideline range) can support this extreme sentence in this not-so-extreme case of fraud. If reasonableness review has any substance whatsoever, and if the facts in this article are accurate, it seem clear to me that this sentence ought to be found substantive unreasonable.

0 notes

Text

On bullshit

I am quoted in Leslie Peacock's article about doctors and medical marijuana. I do not disown any of the things I am quoted as saying, and I commend Peacock on her excellent research and writing. I've enjoyed reading her for at least two decades. But the slant of the article creates a misperception that I am (and many other doctors like me are) cruelly depriving suffering human beings of beneficial treatment. This is not correct.

Silly season

The "silly season" is almost here. This is the season in which some people talk and act crazy about themselves and public policy. It happens around every two years. Political candidates do everything in their power to win public office. In Arkansas, judicial candidates file as early as December of this year. Democrats and Republicans will start signing up as early as February 2018. Voting for primary elections starts in early May. When the primaries are finished, Arkansas's political government will basically be decided. There is only one viable political party now in Arkansas, the Republicans, and winners of the Republican primary contests will most likely proceed to public office. The general election in November 2018 will simply be a formality for our red state's constitutional officers and most of the legislature. Our governor, attorney general and representatives can plan their agendas now for the next two years.

The silly season is also made simpler by computer voting. Arkansas is quickly switching to the Schouptronic machines provided by the Danahar Control Corp. in Illinois. Paper trails are not available to the silly news media and software engineers will eventually be able to design voting results throughout our state. Maybe someday soon Arkansans will be able to phone text their choices for "Republican Idol." Virtual democracy and a one-party system take a lot of the silliness out of politics.

Gene Mason Jacksonville

On bullshit

I am quoted in Leslie Peacock's article about doctors and medical marijuana. I do not disown any of the things I am quoted as saying, and I commend Peacock on her excellent research and writing. I've enjoyed reading her for at least two decades. But the slant of the article creates a misperception that I am (and many other doctors like me are) cruelly depriving suffering human beings of beneficial treatment. This is not correct. The problem is that there is a lack of scientifically valid evidence that marijuana is helpful for any medical condition that I treat, such as PTSD. Peacock notes on the Psychiatric Associates of Arkansas Facebook page an article reviewing the evidence for using marijuana for PTSD and chronic pain. The article concludes there is no good evidence that marijuana is a beneficial treatment for either of these conditions. The article is published in the prestigious, peer-reviewed journal Annals of Internal Medicine and is summarized in a Reuter's clip. Peacock's article states that my office "voted" not to certify medical marijuana. Voting has nothing to do with this or with determining whether any medical treatment is appropriate. If doctors voted that apple juice cured colon cancer, it would not make it any more effective. I do not object to unusual treatments. If you look on the Facebook page there are also articles about using ketamine (the club drug "special K") as a treatment for depression and MDMA (the club drug "ecstasy") as a treatment for PTSD. If there is evidence a treatment is safe and alleviates human suffering or remediates human disease, then I am all over it. The "evidence" for medical marijuana is testimonial. While testimony is emotionally compelling, it carries no scientific weight. It is not hard to find examples of testimony to just about anything. Even the available testimonial data is not gathered in the systematic scientific way a medical sociologist might do. In my own area of psychiatry there is plenty of evidence that marijuana does harm. For instances it can provoke paranoia and psychosis in people who are predisposed. It can interfere with motivation and memory. I defer to other specialists regarding marijuana as a treatment for seizures, HIV, Alzheimer's disease, etc.

I know that the law only requires that a doctor certify that somebody has one of the listed conditions and does not require the doctor to certify that it is his or her professional opinion that marijuana helps the condition. Think about who this disclaimer lets off the hook: It is not the doctors who provide treatments to patients that are proven to be helpful to them. I will never in my capacity as a doctor advise a patient: "Take this; there is no evidence it works and I don't know whether it does more harm than good — but here you go."