#derisking

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cindy Picos was dropped by her home insurer last month. The reason: aerial photos of her roof, which her insurer refused to let her see.

“I thought they had the wrong house,” said Picos, who lives in northern California. “Our roof is in fine shape.”

Her insurer said its images showed her roof had “lived its life expectancy.” Picos paid for an independent inspection that found the roof had another 10 years of life. Her insurer declined to reconsider its decision.

Across the U.S., insurance companies are using aerial images of homes as a tool to ditch properties seen as higher risk.

Nearly every building in the country is being photographed, often without the owner’s knowledge. Companies are deploying drones, manned airplanes and high-altitude balloons to take images of properties. No place is shielded: The industry-funded Geospatial Insurance Consortium has an airplane imagery program it says covers 99% of the U.S. population.

The array of photos is being sorted by computer models to spy out underwriting no-nos, such as damaged roof shingles, yard debris, overhanging tree branches and undeclared swimming pools or trampolines. The red-flagged images are providing insurers with ammunition for nonrenewal notices nationwide.

“We’ve seen a dramatic increase across the country in reports from consumers who’ve been dropped by their insurers on the basis of an aerial image,” said Amy Bach, executive director of consumer group United Policyholders.

The increasingly sophisticated use of flyby photos comes as home insurers nationwide scramble to “derisk” their property portfolios, dropping less-than-perfect homes in an effort to recover from big underwriting losses.

(continue reading)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Expert policy-makers in Western capitals feel that they have to make a response to major historic challenges like climate or the rise of China, or South Africa’s energy crisis. It is their job to look to the future and to devise at least purportedly rational strategies of power. But those who make policy on such matters as sustainable development do not hold the purse-strings and have limited capacity to shift budget-constraints. Those that do set budgets, either do not care about broader global issues, prefer other tools for affecting those goals - such as military power - or are revenue constrained and unwilling to levy more revenue from their constituents for the far-flung goals favored by the policy-making elite.

There is thus never “enough money” for the softer and more complex dimensions of development and global policy. But, despite these all too obvious limitations, the policy-machine grinds on. Faut de mieux those tasked with geoeconomic policy and sustainable development cooperate to come up with programs like JET-P. The policies tick all the boxes as far as sophistication of design and conception. Powerful interests - notably high-finance - ensure that they are arranged, at least notionally, so as to offer derisking and to promote the vision of public-private partnership. The promise of “mobilizing” private money helps to paper over the lack of solid public funding.

But despite all the self-interested engagement by private finance, the fiscal constraint remains paramount. The forces interested in global development are not as powerfully engaged as they are around the military-industrial complex, oil and gas or the Wall Street nexus. The result are ambitious and professionally designed policies that whip up waves of enthusiasm in the ranks of analysts, think tanks, NGOs, pundits, but which have no prospect of materially affecting reality either with regard to the announced policy objective or the profit opportunities of Western capital.

From experience since 2021 the conclusion we must surely draw is that the one interest that such policies undeniably serve is the perpetuation of the policy circuit. Practical effectiveness is not necessarily the main driver of policy-generation. Indeed, failure may be productive in generating new policy. This not only perpetuates the machinery of policy-making. More importantly it contributes to the generation of a “state effect” - the US has a policy for x,y,z. It sustains the common sense that the world is governed and that “governance” is in some sense a coherent process.

brutal

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

The core defining feature of capitalism is that it is fundamentally anti-democratic. Yes, many of us live in democratic political systems, where we get to elect candidates from time to time. But when it comes to the economic system, the system of production, not even the shallowest illusion of democracy is allowed to enter. Production is controlled by capital: large corporations, commercial banks, and the 1% who own the majority of investible assets… they are the ones who determine what to produce and how to use our collective labour and our planet’s resources. And for capital, the purpose of production is not to meet human needs or achieve social objectives. Rather, it is to maximize and accumulate profit. That is the overriding objective. So we get massive investment in producing things like fossil fuels, SUVs, fast fashion, industrial beef, cruise ships and weapons, because these things are highly profitable to capital. But we get chronic underinvestment in necessary things like renewable energy, public transit and regenerative agriculture, because these are much less profitable to capital or not profitable at all. This is a critically important point to grasp. In many cases renewables are cheaper than fossil fuels! But they have much lower profit margins, because they are less conducive to monopoly power. So investment keeps flowing to fossil fuels, even while the world burns. Relying on capital to deliver an energy transition is a dangerously bad strategy. The only way to deal with this crisis is with public planning. On the one hand, we need massive public investment in renewable energy, public transit and other decarbonization strategies. And this should not just be about derisking private capital – it should be about public production of public goods. To do this, simply issue the national currency to mobilize the productive forces for the necessary objectives, on the basis of need not on the basis of profit. Now, massive public investment like this could drive inflation if it bumps up against the limits of the national productive capacity. To avoid this problem you need to reduce private demands on the productive forces. First, cut the purchasing power of the rich; and second, introduce credit regulations on commercial banks to limit their investments in ecologically destructive sectors that we want to get rid of anyway: fossil fuels, SUVs, fast fashion, etc. What this does is it shifts labour and resources away from servicing the interests of capital accumulation and toward achieving socially and ecologically necessary objectives. This is a socialist ecological strategy, and it is the only thing that will save us. Solving the ecological crisis requires achieving democratic control over the means of production. We need to be clear about this fact and begin building now the political movements that are necessary to achieve such a transformation.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last February, as the sound of automatic weapons erupted in the early hours before dawn, Amina Museni hurriedly packed a bag while her husband, Joseph, shook their three children awake. They were joining a group of neighbors fleeing their hamlet as the front line between the Congolese army and rebels of the March 23 Movement, or M23, crept closer. For days afterward, they walked across the hilly landscape of Masisi, in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, before reaching one of the camps that have sprung up around Goma, the capital of North Kivu province. There, they pitched their tent, a young family of five among more than a million people displaced by the resurgence of a conflict that has ravaged Congo for nearly three decades.

When Foreign Policy visited the camp last July, Museni sat amid an undulating sea of white tarpaulins stretched over eucalyptus sticks. “When I was little, I lived in a tent with my parents,” Museni said, her youngest child, Nestor, cradled into her neck. “Now my children have to endure the same. It feels like a curse.”

Why Congo has been in a perennial state of upheaval since the mid-1990s has been the subject of much debate, but no other narrative has cut through as much as that of so-called conflict minerals. In the 2000s, the link between markets’ demand for minerals and the war in Congo helped bring attention to the conflict in an unprecedented way. Western organizations such as the Enough Project and Global Witness mobilized around the seductive proposition that the solution to one of the world’s deadliest conflicts was within the grasp of consumers and policymakers, triggering a series of laws and regulations beginning with, in the United States in 2010, Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The logic behind the legislation was simple. “Armed groups finance themselves through the exploitation of cassiterite, gold, coltan,” Fidel Bafilemba, a Congolese researcher who used to work for the Enough Project, told me at the time. “By stopping the export of these conflict minerals, we dry up their resources and lessen the violence.”

Section 1502 required companies to conduct due diligence checks on their supply chain to disclose their use of minerals originating from Congo and neighboring countries and to determine whether those minerals may have benefited armed groups. The legislation didn��t outright ban the sourcing of minerals from mines contributing to conflict financing but instead intended “this transparency and its attendant reputational risk” to pressure companies to stop buying them voluntarily, according to Toby Whitney, one of the authors of Section 1502.

What followed is an important lesson for a world rushing to secure critical minerals for the energy transition. Western advocacy led to policies focused on derisking supply chains and virtue signaling to consumers, rather than improving artisanal miners’ living conditions or addressing the conflict’s root causes. That narrative continues today: An Apple store in Berlin was vandalized last week by Fridays for Future activists accusing the tech giant of sourcing so-called conflict minerals from Congo.

ITSCI, the region’s leading private traceability scheme, is facing criticism about the validity of its work—and that it has not improved the lives of artisanal miners in the region. ITSCI stresses its limited mandate and that it is working as intended. But in a cruel twist, the cost of the due diligence program has been shouldered by Congolese miners themselves, effectively asking the world’s poorest workers to pay for the right to sell their own resources to Western companies.

This week, industry leaders and activists gathering at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris for the annual Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains will need to reassess their approach. “We welcomed Dodd-Frank,” said Alexis Muhima, a Congolese researcher, during a meeting in a cramped office in Goma. “But what it did is outsource complex issues to the private sector, and we’ve been paying for it ever since.”

“The Americans didn’t think this through.”

There was a time in the 1970s when the quarries of Nyabibwe, a mining town in South Kivu province, were run with enough capital to employ 500 workers and to invest in semi-industrial machinery. Every month, the French company in charge shipped 20 metric tons of cassiterite ore—a component of tin—back to Europe for cans, wires, and solder. Safari Kulimuchi was a worker at the mines, starting at age 17, who quickly rose through the ranks to become a manager. “It was an exciting time. … Things seemed to be working out,” Kulimuchi recalled to Foreign Policy over dinner in Nyabibwe. But, he said, “it didn’t last.”

In the years that followed, Kulimuchi witnessed the economic unraveling of Congo (then Zaire), rotten under decades of rule by dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who presided over the country from 1965 to 1997. Amid a global economic downturn in the mid-1980s, the French company departed, abandoning its workers to fend for themselves. “Overnight, we had no wages, no tools, no structure,” Kulimuchi said. “We used to have a stone crusher. Now we had to crush rocks with a hammer.”

Nyabibwe was far from an exception. Across the country, as investment dried up and the state abdicated its responsibilities, people resorted to making ends meet any way they could. An informal economy based on débrouillardise, or resourcefulness, sprouted in the ruins of Mobutu’s derelict regime. That informal economy is estimated to account for more than 80 percent of Congolese economic activity today. Nyabibwe grew into a town as people came from far and wide to work in the mines. They replaced the industrial machinery with picks and shovels, a low-capital, labor-intensive extraction called artisanal mining, as opposed to industrial mining. “Artisanal mining is the heart of our economy. It’s the reason Nyabibwe became this big center,” Kulimuchi said. The World Bank estimated in 2008 that up to 16 percent of the Congolese population depended on the sector. “For us, it’s a lifeline,” Kulimuchi added.

Mobutu was finally ousted in 1997 by a coalition helmed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel army led by Paul Kagame. Kagame had just seized power in Rwanda in the aftermath of the genocide there and was intent on chasing after Hutus responsible for the massacres, many of whom had crossed into Zaire. What became the First Congo War brought Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a Congolese rebel, to power.

Kabila’s allies in the RPF quickly turned into foes when they refused to relinquish control over an area where instability threatened their security and interests. The Second Congo War began in 1998 with the creation of the RCD, a Tutsi-led, Rwandan-backed armed group that quickly gained control of a large swath of eastern Congo. The rebels began shipping cargo loads of coltan and cassiterite ores out of mines such as Nyabibwe’s into Rwanda just as the price of coltan, a key component of capacitors used in mobile phones and most electronic devices, soared with the demand for electronic goods at the turn of the century. A 2001 United Nations report estimated that Rwanda made at least $250 million during a temporary spike in prices in late 1999 and 2000. A popular formulation in Western campaigns at the time linked the violence in Congo to “blood phones.”

Many experts have criticized the advocacy of the 2000s for sometimes going so far as to suggest that conflict minerals were the root cause of the violence, painting armed actors as merely bloodthirsty, greedy militias—instead of considering real, historical grievances. The Enough Project campaigns, leaning hard on celebrities such as Robin Wright and Ryan Gosling to spread the group’s message, obfuscated the nuances of the conflict and the vital place of artisanal mining in the local economy. “The ‘conflict minerals’ label was problematic,” said Sophia Pickles, a former Global Witness campaigner and U.N. investigator. “This isn’t just about Congo—it’s a global issue.”

The campaigns succeeded in putting the issue on U.S. legislators’ agenda, but Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act was both too specific—singling out the so-called 3T minerals (tin for cassiterite, tantalum for coltan, and tungsten) in eastern Congo—and extremely vague on execution. It deferred the drafting of rules to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), leaving companies with no clear guidelines to report on their supply chain.

The law created a panicked scramble in the industry, said William Millman, a former technical director at Kyocera AVX, a leading manufacturer of electronic components and major coltan buyer. “Everybody was ignorant about the specifics. We just relied on our smelters.” Unlike an oil company directly operating its wells or a sneaker company outsourcing production to a sweatshop in Asia, electronics companies have virtually no way of knowing where the minerals in their products come from upstream of the smelters or refiners that have turned them into smooth metal—unless the smelters themselves know. “I visited all my suppliers to gather information. They knew very little because it was all largely bought on the spot market with international brokers,” Millman said. As a result of Section 1502, companies liable to fall under the SEC rule demanded that their suppliers simply stop buying from eastern Congo.

The result? A de facto embargo dropped like a bomb on the mining communities of North and South Kivu, just as the region was emerging from its latest cycle of violence. Nyabibwe had navigated two major wars mostly unscathed, but when I visited in June 2012, the town was in the midst of an existential crisis. Businesses dependent on the cash flow generated by the mines were closing down one by one, unable to sell stockpiles of rubber boots and shovels, blacksmithing services, or simply food. Tellingly, the local nightclub had shut its doors. More concerning were thousands of families’ insufficient funds to access health care, forcing women to give birth at home. One study found that the boycott increased the probability of infant mortality in affected mining communities by at least 143 percent.

Kulimuchi, who was then 54, was still managing a small team of undeterred miners. “The Americans didn’t think this through,” he said. His team had three metric tons of ore stored in a warehouse in Bukavu, South Kivu’s capital, waiting to be bought and shipped. “School is about to start again. Where are we going to find the money to send our children?”

Though U.S. lawmakers had struck out on their own with Section 1502, industrywide talks to create guidelines for the responsible sourcing of minerals in high-risk areas globally were already underway at the OECD. The OECD guidelines, adopted later in 2010, ended up becoming the foundation for the SEC rules, released in 2012. “The choke point in the supply chain is the smelters—everything has to go through them, and there aren’t many smelters in the world,” Millman said. “The OECD came up with a standardized protocol to audit and certify the smelters on an annual basis to know that they have control and knowledge of their supply chain.”

According to Millman, a handful of downstream companies seemed genuinely interested in doing things right and getting involved at the mine level. In 2011, together with Motorola and the Washington-based NGO Resolve, what was then AVX launched Solutions for Hope, a pilot project in Congo’s Katanga (now Tanganyika) province, where there was no conflict. They created a closed-pipe supply chain, sourcing from artisanal mines through a company that sold directly to a Chinese smelter and then onward to AVX, which manufactured components for Motorola and Hewlett-Packard.

Solutions for Hope also decided to hire the services of ITSCI. Its “bag and tag” traceability scheme set up by the International Tin Association (ITA) promised to trace minerals from the mine and guarantee their origin to buyers through a paper trail associated with sealed tags affixed on bags. According to Millman, Solutions for Hope was successful largely because its integrated supply chain bypassed traders and brought end-user companies closer to the miners. Replicating it would take time and effort. But, Millman said, “what other companies who had sat back saw was that, suddenly, with ITSCI there was a way for their CEOs and CFOs to sign off on their SEC statements. … And so everyone piled in, and it became the easy option.” ITSCI’s first project in eastern Congo was implemented in October 2012 in Nyabibwe.

“Do you think these people stopped working?”

Ten years on from when we first met, Kulimuchi came down from the mountainside where he had been working with his son on a sunny day last July, his broad smile still intact. The mining site hadn’t changed much either. Around us, men wearing flip-flops were using the same basic tools to split the earth open, with no protective equipment.

Initially, Kulimuchi recalled, the artisanal miners had been relieved when a large delegation showed up to officially launch the traceability scheme. “It meant we could finally start selling again. All my financial worries would be a thing of the past,” Kulimuchi said he thought at the time.

Instead, an elaborate public-private bureaucracy emerged, driven in part by regional governments intent on bringing the artisanal mining sector under control but quickly superimposed by foreign private sector initiatives like ITSCI, responding to market demand for paperwork required by end-user companies to file their reports to the SEC.

“We started selling again, but it’s a cacophony. There is a ton of admin, taxes after taxes, and prices have gone down. We have been weakened by all this,” Kulimuchi said.

As the de facto embargo on eastern Congo’s minerals lifted, by 2012 thousands of small sites across the region found themselves effectively outlawed by a new mine site validation process. To be able to sell, Congolese mining sites must now be inspected by a delegation of government representatives, NGOs, and U.N. agencies. At sites given the go-ahead from that audit, the Congolese artisanal mining agency carries out its own checks while also tagging and recording the minerals in logbooks for ITSCI. There are other records kept by the provincial government’s Mining Division and a regional body. Many sites are still waiting for an audit. For those that don’t conform, the consequences are devastating: “You are destroying the livelihood of hundreds or thousands of people,” said Maxie Muwonge, who was a program manager for the International Organization for Migration between 2013 and 2018 when it was tasked with coordinating the validation process. “This excludes entire communities. What are they meant to do? Do you think these people stopped working?”

In fact, even under the de facto embargo, the minerals trade never really stopped. It just went further underground. Rwanda’s export statistics, which experts say don’t match its reserves, suggest that smuggling to neighboring countries spiked during the period. While the volume of trafficked minerals has fallen with the reopening of the legal market in eastern Congo, smuggling is still an issue, not least because of the market distortion caused by heavy regulation and taxation in Congo of small businesses. “Many collapsed because they couldn’t meet the requirements, and the investment in the sector decreased. It broke down artisanal miners even further,” Muwonge said.

Joyeux Mumpenzi followed in his mother’s footsteps when he decided to become a négociant, an intermediary who buys minerals from the creuseurs, or diggers, and transports them to export companies in large cities—a reflection of the highly organized division of labor in the artisanal sector. “To begin with, we have no say regarding the going price—the London Metal Exchange sets it, and it fluctuates constantly,” he said. “Then there are all the taxes, and finally, the export company retains a penalty on my payment for ITSCI.”

Today, 99 percent of ITSCI’s revenue comes from the levies it collects from upstream actors based on the volumes of minerals tagged and exported, ITSCI program manager Mickaël Daudin said in an interview. The organization says artisanal miners are not supposed to pay for the scheme. But the cost, or at least a percentage of it, is passed down the supply chain to the négociants and ultimately to the miners. “I have no choice” in doing so, Mumpenzi said. “I end up earning little more than they do, and I take huge financial risks.” The 33-year-old trader says he earns about $300 a month, while an artisanal miner’s household makes $200 on average.

ITSCI, which operates in both Congo and Rwanda, applies differentiated levies to businesses in the two countries. Daudin said that’s because “the cost of implementation … remains much higher” in Congo than in Rwanda but declined to disclose the levies’ rates; a Congolese government official called it a “conflict tax.” The rate discrepancy effectively encourages trafficking to Rwanda for Congolese mining operators keen to increase their margins.

A report published in 2022 by Global Witness cited “[s]ome industry sources” alleging that ITSCI was in fact set up to facilitate the laundering of Congolese minerals smuggled into Rwanda. Foreign Policy hasn’t been able to confirm the claim, but the tagging system that ITSCI created does offer the perfect cover for smuggling, in Rwanda or Congo. The integrity of the scheme relies entirely on the integrity of the people implementing it; the tags themselves offer no guarantee. In a statement released in response to the report, ITSCI wrote that it “strongly rejects all Global Witness’ stated or implied allegations of wrongdoing, facilitating deliberate misuse of ITSCI systems or illegal activity.” If ITSCI had aimed to maximize smuggling into Rwanda as alleged, a spokesperson wrote to Foreign Policy in an email, “ITSCI would not have launched in Katanga in 2011 nor in any other adjoining locations at other times. During 15 years of implementation, ITSCI has continued to expand the programme in [Congo], now supporting more than 1,500 sites across 8 Provinces.”

The Global Witness report also documented how the system can be breached without ITSCI’s cooperation. For starters, the tagging is not performed by ITSCI but by Congolese government agents who earn less than the miners themselves and sometimes go for months without pay at all. From bribing agents to trading in tags, the number of ways to circumvent the system is almost limitless—as Mumpenzi demonstrated to Foreign Policy. The négociant stood up from the sofa in his living room and walked to a corner where sturdy white plastic bags had been stacked. “See the tags? The bags were sealed by an agent before I picked them up yesterday,” he said. “The mineral sand now has to be washed, so when I’ll bring the bags to the washing station, the tags will be removed. When minerals are washed, the weight goes down, so this is a perfect time to smuggle in minerals before a new tag goes on. As long as the bag weighs less than it did initially, no one will say anything.”

ITSCI doesn’t rebuke such allegations categorically. The organization says it was aware of many of the incidents documented by Global Witness and had already addressed them. “The program isn’t perfect. There are issues, and there always will be,” Daudin told Foreign Policy. “But from my point of view, it wasn’t better before.”

Kulimuchi and other artisanal miners might beg to differ. Rather than improving their living conditions, the “increasing regulation of the artisanal mining sector and responsible sourcing efforts, have rather had a negative overall effect on the socio-economic position of artisanal miners,” analysts at the International Peace Information Service (IPIS), a leading minerals research institute, wrote in 2019. Guillaume de Brier, a researcher at IPIS, told me that “working in an ITSCI or a non-ITSCI site doesn’t change anything. Conditions are dismal in both cases. There’s no difference in terms of child labor, and miners don’t earn more.”

When asked by Foreign Policy about this criticism, an ITSCI spokesperson stressed the organization’s limited mandate as a traceability and due diligence not-for-profit initiative. “It does not function as a certification mechanism,” the spokesperson wrote, and the organization’s focus “does not extend to working conditions.”

However, evidence suggests that responsible sourcing efforts have failed to shift conflict dynamics. A 2022 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), part of its mandate to evaluate the impact of Section 1502, was titled “Conflict Minerals: Overall Peace and Security in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo Has Not Improved Since 2014.” Violence has instead risen, remaining “relatively constant from 2014 through 2016 but steadily [increasing] from 2017 through 2021,” GAO wrote.

Arguably, some measure of progress has been achieved at the 3T mining sites targeted by Dodd-Frank, where the presence of armed groups has decreased. But while ITSCI claims to have played a role, de Brier says the scheme merely implanted in sites where the situation was already better. Overall, this demilitarization has largely been the result of Congolese policies and the evolution of conflict dynamics themselves: The defeat of the M23 rebellion in 2013 (the armed group changed names multiple times as it successively integrated into and rebelled against the national army) led to the dismantling of one of the country’s most predatory mafia networks. Today, for instance, Bisie, once an iconic mining site under the control of Bosco “The Terminator” Ntaganda, is operated by the Canadian company Alphamin. (Ntaganda is serving a 30-year prison sentence in Belgium following his conviction by the International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity.)

Now though, with the resurgence of the M23 rebellion since November 2021—which has displaced Museni, her family, and more than 2.5 million others—even that small measure of progress is under threat.

“This is how the armed groups are paid.”

Belgian colonial administration profoundly altered the Congolese relationship with the land, introducing private ownership and displacing people for commercial exploitation. Since independence, who has the right to own land—and by extension its resources—has remained an unresolved existential question. “The main resource driving conflict isn’t coltan,” said Onesphore Sematumba, an analyst at the International Crisis Group. “It is the land. It’s material ownership, of course, but also who has a legitimate right to be here.”

In the borderlands of eastern Congo, these questions have been exacerbated by intertwined histories with neighboring countries. Hutus and Tutsis, who arrived from Rwanda in successive waves throughout the 20th century—first brought by Belgian colonialists to work on plantations in the territories of Rutshuru and Masisi—have struggled to find acceptance and secure land rights. Rwanda, meanwhile, a small, densely populated country with little resources of its own, largely depends on economic ties and access to Congo’s resources. These two dynamics have helped create the vicious circle of the last three decades. Backed by Rwanda, the RCD rebellion and its successors claiming to fight for Tutsis’ rights have helped entrench tensions along ethnic lines while facilitating land grab by a small elite.

“Indigenous communities in Masisi were dispossessed of their land during the war,” said Janvier Murairi, a Congolese researcher. “Today’s farm and mine owners are people who had links to the RCD. Everything from Mushaki to Masisi town belongs to hardly more than 10 people.”

One such owner was Edouard Mwangachuchu, an aspiring Tutsi politician and a member of the RCD’s political branch, who was awarded a concession covering seven mines in Rubaya by the rebel administration in 2001. Two years later, the Sun City Agreement, a peace deal negotiated between rebel factions with little regard for social justice or community grievances, endorsed Mwangachuchu’s ownership over the mining sites as a prize of war for the RCD, granting his company, MHI (now SMB), control over what have become the most productive sites at Congo’s largest coltan mine. Today, Rubaya accounts for about 15 percent of global coltan production.

Rubaya is emblematic of the way ITSCI, and more broadly due diligence as it is practiced today, treats “conflictual issues, such as concessions and land ownership, … as a black box,” Christoph N. Vogel writes in his 2022 book, Conflict Minerals Inc., turning a blind eye to political issues around social justice and equity, even as those are drivers of the violence it means to help prevent.

In Rubaya, Mwangachuchu’s plan to turn the quarries into an industrial mine spurred a backlash from local communities. “The artisanal miners didn’t accept that this family [the Mwangachuchus] who had come into the possession of the mines through the conflict could take away their livelihood,” Murairi said. The government mediated a deal: The miners were allowed to continue mining SMB sites but had to sell exclusively to the company.

ITSCI began operating in Rubaya in 2014, tagging minerals from both SMB and peripheral sites belonging to a state-owned mining company, SAKIMA. But the situation unraveled as the scheme was embroiled in a tit-for-tat commercial war in the years that followed.

Suspecting that ITSCI’s tags were being used to launder the sale of its minerals to a rival trading company, SMB eventually turned to ITSCI’s main competitor in the tag-and-bag business, Better Mining. The move should have represented a major financial blow to ITSCI, the loss of roughly half its revenues for Congo. Instead, as production at the SAKIMA sites kept growing while SMB’s dwindled, ITSCI’s business was preserved. According to an internal U.N. report provided to Foreign Policy, “Only about seventeen percent of the production that officially originates from the SAKIMA concession has in fact been mined there.” The report noted that “[s]uch discrepancy between official data and reality is only conceivable if a structured mechanism of fraud is established.”

Daudin, the ITSCI program manager, responded that ITSCI is “confident about its data.” He argued that the production increase was due to the higher level of investment going to SAKIMA sites when local miners turned away from SMB.

The M23’s resurgence dealt the last blow to Mwangachuchu, who was arrested in March 2023 and charged with treason after weapons were allegedly found on the grounds of his company’s facilities in Rubaya. According to the prosecutor, Mwangachuchu intended to support the M23 rebellion. The government has since revoked SMB’s mining permits. Few people in North Kivu will feel sorry for Mwangachuchu, “but one of the protagonists was pushed out in favor of the other, and that never works,” said Achile Kitsa, a former private secretary to the provincial mines minister.

The Congolese army took full control of Rubaya last spring, leaving the former SMB concession at the mercy of local armed groups it used as proxies on the front line against the M23. “This is how the armed groups are paid,” said a Congolese researcher who spoke on condition of anonymity. ITSCI resumed its operations in June, tagging minerals from the SAKIMA perimeter up until November, when the road was cut off by the fighting, according to Daudin. “We relaunched our activities after evaluating each site with the government services,” he said in July. “There are no nonstate armed groups in our sites.”

In a December report, the U.N. Group of Experts on Congo contradicted Daudin, establishing that between June and November, the “production from [the former SMB] sites was either smuggled to Rwanda or laundered into the official supply chain using [ITSCI] tags for minerals produced in [the SAKIMA concession], where mining activities were still authorized.”

“ITSCI recognizes that there have been, and remain, ongoing risks regarding fraud and presence of both non-state and state armed groups in the area of Masisi territory, North Kivu,” the ITSCI spokesperson wrote. “These risks are regularly reported through ITSCI’s OECD-aligned systems.”

Muhima, the Congolese researcher, sees the possibility of tainted minerals in the ITSCI supply chain as inevitable, given its built-in conflict of interest. “Their income depends on the volume they export. They cannot stop tagging minerals, or their business will collapse.”

“We don’t need another scheme.”

Congolese activists were not pleased with the Global Witness report exposing the shortcomings of ITSCI when it was published in 2022. They felt that the research mostly rehashed criticisms and evidence that they had presented for many years without being listened to and that the report failed to draw the necessary conclusions, ending with tepid recommendations to reform ITSCI or consider options to replace it with another independent scheme. “We don’t need another scheme,” Murairi said. “We don’t need more foreigners who think Congolese can’t do anything.”

Global Witness’s cautiousness should perhaps not come as a surprise. The activist organization played no small part in paving the way for today’s conundrum, and the risk of triggering another de facto embargo on Congolese minerals hangs heavy. “We’ve learnt some very difficult lessons, and as an activist, I’m not the one who bore the consequences of bad policymaking,” said Pickles, the former Global Witness campaigner.

When I pressed Daudin last July about ITSCI’s resumption of its activities in Rubaya, even as armed groups were swarming the mining area, he dodged: “If we don’t start tagging again, mining communities will be the first ones to suffer from not being able to carry on their activities.”

ITSCI suffered a major setback in October 2022, when the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), a member association of more than 400 of the world’s largest corporations, announced that it was taking the scheme off its list of recognized upstream due diligence mechanisms. ITSCI had failed to submit an independent assessment of its alignment with the OECD guidelines in time. When the organization eventually released an independent audit in June 2023, it failed to assess ITSCI’s activities in Congo, focusing solely on coltan production in Rwanda. The RMI has offered to pay for three site visits in Congo, including in Rubaya, but ITSCI has so far not agreed. (“Site visits outside alignment assessments are not explicitly required,” said the ITSCI spokesperson, who noted the terms of such a visit are nonetheless under negotiation with RMI.)

“They are holding everyone hostage,” an industry insider close to the RMI process told Foreign Policy. “There is so much pressure on the RMI to capitulate and say we need this system. But this isn’t a technical issue.” To many experts and industry insiders, the resurgence of the M23 conflict has at least had the benefit of clarifying the situation. “The system cannot withstand what it was built for. It can’t withstand the conflict. We are back to square one.”

Breaking ITSCI’s quasi-monopoly is often presented as the solution in minerals circles, but SMB’s switch to Better Mining solved none of the problems in Rubaya and only created more confusion. Better Mining’s for-profit business model and its reliance on technology make it hard to scale and mean it is explicitly designed for larger companies with capital, not artisanal miners. “The problem with all these initiatives is that no one is there to control them,” said de Brier, the IPIS researcher.

Who is supposed to exert this control is part of the problem. Much like the fragmented nature of the supply chain, the nebulous ecosystem of public and private actors involved in responsible sourcing means that responsibility befalls no one in particular. In a July 2023 report, the GAO noted that the number of companies filing conflict minerals disclosures to the SEC had been steadily declining year-on-year since 2014, in part because “companies perceive that they are unlikely to face enforcement action by the SEC if they do not comply.”

Pickles noted that, unlike Dodd-Frank, the European Union’s own conflict minerals regulation, which came into force in 2021, avoided the trap of focusing only on Congo but equally fell for industry schemes such as ITSCI. “I’ve spoken to the competent authorities of three member states, and they said that the reports they receive from companies don’t tell them anything. They don’t actually know what’s happening along the supply chain,” she said. “So where does that leave us?”

For Congolese, ending this hypocrisy is a necessary first step but requires trust and support on the part of international partners. “The Congolese government has its own traceability system. All the necessary documents are delivered by Congolese state agencies. They tell you where the minerals come from just as reliably as ITSCI’s tags, which is to say it’s not perfect but it’s no worse,” Muhima said. “The same state agents deliver these documents and implement ITSCI’s program—for free I might add, since ITSCI doesn’t pay for them. What needs to be improved urgently is their payment.”

These lessons are relevant beyond the specifics of the 3T supply chain. The attention around cobalt—the conflict mineral du jour thanks to its use in electric vehicle batteries—is a case in point. While there is no conflict in the area where cobalt is extracted, working conditions and child labor have been discussed in much the same way as conflict minerals were back in the 2000s: in decontextualized and sometimes inaccurate reports that fail to examine the complex ways in which minerals interact with people’s livelihoods. Instead, such reports paint artisanal mining as illegitimate, something to eliminate. They have been used to justify land grab by large mining companies whose supply chains are easily traceable for end-user companies.

“We haven’t learned from our experience with diamonds or 3T minerals. With cobalt, it’s as if those experiences never existed,” said Joanne Lebert, the executive director of IMPACT, a nonprofit organization working on natural resource governance. “Instead of supporting communities, we’re just monitoring. There is no connection in my view between a clean supply chain and governance and security outcomes. Maybe you take kids out of your supply chain, but they’ll go to agriculture, to domestic work. They’ll go to another mine. They’ll sneak in at night. Clean supply chain is about eliminating the risk and not necessarily about doing good. And it’s the doing good we have to get at.”

Following the same pattern, an EU law aimed at preventing products linked to deforestation from entering the European market is pushing coffee companies toward industrial producers able to generate the paperwork and sidelining small farmers from Ethiopia to Brazil. Private companies will always take the shortcut, while black markets, exploitation, and conflict feed on exclusion.

Whether Western consumers like it or not, artisanally mined minerals will continue to find their way into the supply chains that fuel the energy transition and consumer products. Investing in mining communities’ welfare, education, and businesses is indispensable.

Museni is still living in the refugee camp on the outskirts of Goma with her husband and young children. Surrounded, the provincial capital has been struggling to absorb and provide for the constant new waves of displaced families reaching the city as the M23 is inching closer.

Even as evidence of Rwanda’s support to the rebellion has been mounting, the country has still not been sanctioned. In February, the EU signed an agreement “to nurture sustainable and resilient value chains for critical raw materials” with the Rwandan government, calling the country “a major player on the world’s tantalum extraction.” Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi described the deal as a “provocation in very bad taste.”

In Nyabibwe, Kulimuchi took me on a final walk around the town, waving around at the myriad businesses and hard-working people in the streets. “No one here has a bank account, for example. We can’t save. We can’t build,” he said. “We don’t require much—a road to Bukavu, a little boost, you know. Then, we’ll take it from there.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

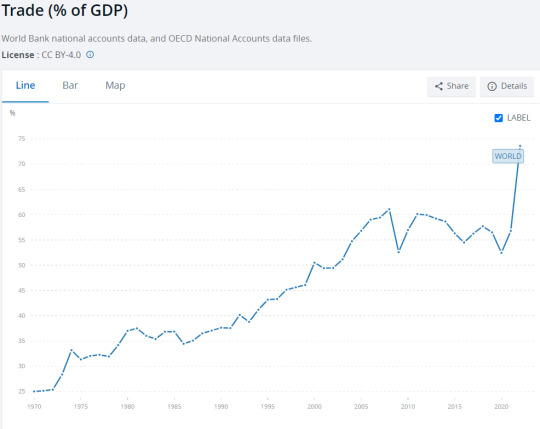

2024: a globalizáció vége

Megjósolni a jövőt nyilván nem annyira egyszerű, úgyhogy egész jó esélye van annak, hogy faszságokat fogok írni, de az is lehet, hogy pár meglátásnak azért lesz értelme.

a wto adatai szerint már 2018 után is csak alig nőtt a világkereskedelem tonnákban mérve, aztán jött a covid, putyin háborúja, ami a középpontba helyezte egyre több helyen a decoupling, a derisking és a friendshoreing fogalmát. ez pl. azon is látszódik, hogy a legfrissebb adatok szerint az usa legfontosabb kereskedelmi partnere mexikó, amit kanada követ, míg kína csak a harmadik. a trump alatt bevezetett vámok ma is élnek, sőt azokhoz újabb kereskedelmi korlátozások kapcsolódtak. az ira és a chips act egészen nyilvánvalóan protekcionista lépések, melyek célja az importhelyettesítés.

európa ugye leginkább az orosz kapcsolatot vágta el, de azért miután kiderült, hogy nem versenyképes az elektromos autók terén, egyre inkább hajlik arra is, hogy kína felé is korlátozza piacát és inkább csak hisztizik amiatt, hogy amerika mennyi támogatást önt a saját iparára. meg persze van a karbonvám és társai, ami a klímára hivatkozva védené az európai piacot. azonban európa nem igazán rendelkezik nyersanyagokkal és azt is örömmel veszi, ha a szennyező iparágak valhol máshol vannak.

kína az ingatlanszektor válságára azt a választ találta ki, hogy növeli az exportját, mert hszi szerint a fogyasztói társadalom valami rossz, nyugati, dekadens dolog, így a belső kereslet élénkítéséről szó sem lehet. a kínai feldolgozóipar és gazdaság ráadásul szintén brutális nyersanyagimportra szorul. szóval kína szívesen folytatná a globalizációt, ahol az állami vagy államilag támogatott kínai cégek versenyelőnyben vannak az állami be nem avatkozás politikáját vivő nyugati cégekkel szemben.

gazdasági értelemben ez a világ jóval több mint fele, a többiek - japán, india, oroszország, közel-kelet - egész egyszerűen nem tényezők vagy csak bizonyos területeken fontosak, mint tajvan és a csipek vagy szaúdarábia és oroszország, meg az olaj. ezen gazdaságok többsége azért inkáb kereskedne, mint kelet és dél-kelet-ázsia vagy a nagy nyersanyagtermelők, mint az oroszok, kanada, ausztrális és a közel-kelet. mindegy is, ez a bekezdés inkább csak mellékszál, de mondjuk india azért annyira nem akar kinyílni, ha nem muszáj.

az sem olyan nagyon meglepő, hogy a világkereskedelem nagyja a tengeren zajlik, ahol azért van egy pár pont, aminek a lezárása komoly gondokat okoz. ilyen a szuezi csatorna és a vörös-tenger másik végén található bab-el-mandeb-szoros, amit ha jól értem a húsziknak többé-kevésbé csak sikerült lezárni, bár talán az indiába és kínába tartó orosz tankereknek nincs miért aggódniuk. ugyanez azonban már nem biztos, hogy igaz az európába tartó, kínai árut szállító dán konténerhajókra.

van persze előnye, ha az ember előbb nézi meg az adatokat és utólag kezd el okoskodni, de szerencsére én képes vagyok megmagyarázni ezt is. szerintem a kereskelem arányának 2022-es megugrása csak statisztikai hiba, az egyre szaporodó korlátozások miatti kerülőutak eredménye. én legalábbis nem nagyon találkoztam olyan információval, ami alapján 2022-ben hihetetlenül nagy új lendületet kapott volna a világkereskedelem. mindegy.

a tézisem nagyjából az, hogy egy egyébként is deglobalizálódó világban, ahol egyre több ország vezet be protekcionista intézkedéseket, a vörös-tenger blokádja tovább ront a helyzeten. mindez európának különösen rossz, magyarországnak meg még annál is inkább. most talán úgy tűnik, hogy a konvojosdi nem működik a vörös-tengeren, de abban biztosak lehetünk, hogy egy trump vezette amerika meg se próbálná megvédeni az eu-kína kereskedelmet.

azt meg remélem nem kell bővebben kifejteni, hogy a bezárkózás egyre több szereplő részéről miért nem ígér sok jót a jövőre nézve. boldog új évet mindenkinek, remélem végül nem lesz igazam

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgive me for this, but ah... Trains are not the paradise you seem to be describing.

They certainly can be - they're far more energy efficient than planes or cars, can be powered directly from renewable sources, and not having to fight gravity means that the engineering constraints are far, far, far looser and more forgiving of creature comforts than planes.

But capitalism is capitalism, and as someone who semi-regularly finds himself on multi-hour train journeys I can assure you that trains can also be pretty bad for comfort levels, especially when the operating company has rammed as many seats in as possible to maximise their profits.

Are they better for disabled people? Absolutely they can be - a lot of modern rolling stock has automatic floor extensions at their doors to close the gap between train and platform, so getting on and off is fine, and under the regulations we have in the UK, disabled accessible carriages have to be provided (which will provide space for multiple passengers in wheelchairs). Would the operating companies not bother if the regs weren't in place? Quite possibly - after all, those wheelchair bays could probably hold 5 or 6 rows of normal seating, while as wheelchair bays, if they're unoccupied by a wheelchair, they only have the 4 or 5 folding seats around the edge. Can people still be dicks about their luggage? Absolutely.

This of course is before we deal with gauge problems - hopefully any new trans-continental high speed rail line would be built to a broad gauge, not least because it would be an opportunity to finally deal with the preponderance of standard gauge, which does place fairly clear limits on the loading gauge - getting four seats and an aisle into standard gauge's loading gauge limits results in quite narrow seats and a narrow aisle - a broad gauge being used might result in a new standard gauge which would be more forgiving and may even start making it possible for the rest of the world to start seriously considering broadening their gauges.

But then capitalism will come back in and make damn sure that the US would never do such a thing (though maybe the current admin could be encouraged to embrace breitspurbahn guage on the basis of "well Hitler liked it") - continuing to use standard gauge on such a line would ensure that the rolling stock is cheaper and would derisk the entire project.

Also, anyone who seriously thinks trains vibrate less than planes ah... have never spent time on a train. They can be smooth as silk, but that requires expensive (to both buy and maintain) suspension systems (those aircushion bogies are lovely), and continuing, meticulous maintenance of the rails - given the rising numbers of derailments in the US in recent years... Yeah that's seemingly an optional consideration.

Also, it's worth noting that sleeper trains (which are what a transcontinental express would probably want to be) would probably be comfier than regular intercity trains, but are not something I've sampled... Because they're fucking expensive, and I can't imagine any redblooded american corporate type not pricing the luxury of a sleeper train to hell and gone (seriously, last time I looked the Caledonian sleeper - only going 800 miles - was north of £1,000 per ticket - I can fly from here to San Francisco for something around the same price).

Basically, if you want transcontinental high speed rail in the US to be what you're all imagining, you're going to have to get the US government to build it, build it to a broad gauge (Indian Gauge would probably be the best option - it's already used in the US on the BART system, and being the standard in India means parts would probably be cheaper than the ideal option of something like Brunel gauge or something even bigger), and then regulate it properly, run it well, and under no circumstances should it be expected to be run at a profit (though ideally it should atleast be able to cover it's running and maintenance costs).

“Nobody’s going to want to sit on high-speed rail for fifteen hours to get from New York City to LA.”

Me. I will sit on high-speed rail for fifteen hours. I’ll sit on it for days. I’ll write and read and nap and eat and then do it all over again. I’ll stare out the windows and see America from ground level and not have to drive. I’ll see the Rockies and the deserts and cornfields and the Mississippi River and your house and yours and yours too. I’ll make up stories in my head about the small towns I see as we go along. I’ll see the states I’ve yet to see because driving or flying there is a fucking slog and expensive to boot. I’ll enjoy the ride as much as the destination. And then I’ll do it all over again to come the fuck home.

189K notes

·

View notes

Text

Undervalued Gem, $CGBS Breakout

Deep-value hunters live for pricing anomalies, cases where market cap barely covers option value on future capacity. Crown LNG at roughly sixty million dollars enterprise value, controlling plans for more than twenty-three million tons per annum of LNG infrastructure, screams anomaly. It trades at nearly one fortieth of the per-ton valuation peers enjoyed at similar project stages. The discount will not persist forever, catalysts loom. NextDecade, pre-Rio Grande FID, fetched twenty-two dollars per annual ton. Tellurian, before financing faltered, hovered near fifteen. Even tiny Glenfarne LNG commands ten. Crown sits under three. Yes, Crown is earlier, but projects are derisking quickly, first steel on Kakinada piles within twelve months.

Banks cannot justify coverage under one hundred million float, compliance cost too high. Many institutionals cannot touch sub-two-dollar stocks. Retail sets the price, often driven by message-board sentiment. That vacuum fosters mispricing. Once any project seals debt, lenders publish base-case cash flows, sell-side desks follow, and valuation increases tend to arrive in vertical spikes, not gentle slopes.

Bears cry dilution. True, Crown will raise equity, but consider scale. Suppose twenty million new shares at twenty cents fund final engineering. Enterprise value rises by four million, optional capacity by billions. Dilution becomes footnote, not thesis killer.

Catalyst Roadmap

Q4 2025, MARAD draft environmental impact statement for Texas platform

Q1 2026, IGX contract signing ceremony confirming multi-buyer flow

Q3 2026, Kakinada debt financial close

Q1 2027, Scottish regulator green-light for Grangemouth pipeline

Each milestone compresses the EV gap. Even half those triggers can triple share price on discount closure alone.

Take sixty-percent odds at least one FID locks, which would bump valuation to peer ten-dollar per ton multiple on 7 MTPA, implying 500 million EV, eight times today. Even after twenty-percent dilution, equity might 6-bag. Forty-percent failure odds still leave expected value near two-hundred million. That is triple the current cap. Numbers suggest mispricing, plain as day.

Undervalued gems hide inside noise. Crown’s noise is illiquidity, boardroom silence, and emerging-market uncertainty. Under that static sits optionality Wall Street usually stamps at three to five billion. Retail holding now owns the claim. If catalysts cooperate, the breakout could be violent. I am sized accordingly.

0 notes

Link

#clinicaltrialdesign#digitaltherapeutics#neuro-innovation#neurodatagovernance#neuroethics#neurotechadoption#regulatorystrategy#TransatlanticCollaboration

0 notes

Text

Climate-related disaster recovery costs are rising. Reports from Bloomberg and RBC cite hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars expended, with these numbers to rise.

0 notes

Quote

In contrast to the sentiment for renewables in the public markets today, we continue to see a bifurcation from private markets where there continues to be robust demand from private investors for our derisked operating assets and platforms with advanced projects and highly executable growth opportunities.

Aiera | Events | Q1 2025 Brookfield Renewable Corp Earnings Call

Despite weak public market sentiment, private investors remain highly bullish on renewables #Energy

0 notes

Text

قد يؤدي سعر ETH إلى حشد 10x ، إذا تم إعداد هذه التجارة بشكل جيد

تعاني أسواق التشفير من موجة صعودية قوية ، تم تسليط الضوء عليها عن طريق اندلاع Bitcoin وتحول واسع في المشاعر. أثبت أبريل 2025 مضطربًا بشكل استثنائي على Ethereum ، حيث بدأ الشهر من خلال عرض محاولات للاسترداد ، بعد أن سجل مؤخراً أعلى مستوى في 30 يومًا عند 2078 دولارًا. ومع ذل�� ، فإن هذا الزخم لم يدم طويلاً عندما دخل السوق مرحلة هبوطية واضحة ، مدفوعة بحذر الاقتصاد الكلي والتحول في مشاعر السوق. على مدار الشهر ، شهد سعر ETH انخفاضًا حادًا ، حيث وصل إلى أدنى مستوى في 30 يومًا عند 1386 دولارًا. هرع المتداولون إلى محافظ Derisk ، مما أدى إلى ضغط بيع ثقيل ، مما ساهم في الشريحة. علاوة على ذلك ، أضاف نشاط الحيتان إلى توترات السوق ، لكن النقاط التقنية التي تبقى حول النطاق المتوسط تتجه نحو زخم صعودي ضعيف وحماس محدود للتعافي السريع. على الرغم من الانتعاش اللامع ، يستمر سعر ETH في التداول تحت تأثير هبوطي. يحاول الدببة حاليًا تقييد التجمع دون 1800 دولار حيث يتعثر الزخم الصعودي بعد ارتفاعه إلى 1780 دولارًا. خضعت خطوط التحويل والأساس لتقاطع صعودي ، لكن سحابة Ichimoku لم تتحول بعد إلى الصعود ، والتي تلمح نحو الانسحاب المحتمل الذي يمكن أن يعيق تقدم التجمع لفترة من الوقت. ومع ذلك ، إذا كانت المشاعر تقلب لصالح الثيران ، فإن السعر يمكن أن يؤمن المقاومة بمبلغ 1800 دولار وبعد ذلك يتجاوز 2000 دولار ، مما قد يبدأ تجمعًا صعوديًا جديدًا. ما مدى ارتفاع سعر Ethereum (ETH) في عام 2025؟سعر Ethereum على المدى الطويل هو وميض الإشارات الصعودية الضخمة حيث يبدو أن الرمز المميز قد انتعش من القاع. يبدو أن الإعداد التجاري الحالي متطابق مع عمليات الثور السابقة ، وبالتالي ، بناءً على ذلك ، يمكن التكهن بأن سعر ETH قد يخضع لارتفاع هائل ويحقق رقمًا مكونًا من 5 أرقام قريبًا. شارك المحلل الشهير ، Cryptorover ، المخطط التاريخي لـ Ethereum ، وأشار إلى أوجه التشابه بين الإجراء الحالي للسعر والإجراء السابق. قال المحلل إن سعر ETH يكرر التاريخ ، والذي قد يؤدي إلى ارتفاع بنسبة 3000 ٪ ، كما حدث في عام 2021. إذا حدث ارتفاع مماثل ، فإن سعر Ethereum قد لا يحقق فقط رقمًا مكونًا من 5 أرقام ولكن أيضًا يتجاوز هذا النطاق لتشكيل ATH جديد.

0 notes

Text

Vaultboy Calls's Post

#SOL - 3 wallets purchased #DERISKING @ $0.00015 | MC: $111.0k Volume: $3,343.37 15m CHART https://gmgn.ai/sol/token/rLkfkJiz_8kUUYUriBscJvMbDNP7vUF2FW14kgbt8DRjwNDc3pump

0 notes

Text

Tariffs, which are taxes on imported goods, are a key part of President Trump’s policy agenda. Pharmaceuticals are among the sectors targeted for tariffs. The administration has highlighted at least two objectives for tariffs on pharmaceuticals: securing U.S. drug supply chains by onshoring drug production and creating U.S. manufacturing jobs.

Understanding the impact of tariffs on pharmaceuticals is important because of the role prescription drugs play in the lives of Americans—61% of American adults (157M) and 20% of children (15M) fill at least one prescription each year through retail or mail pharmacies. Many of the same patients also get drugs administered in virtually all inpatient hospital stays. And millions of patients receive physician-administered drugs in the outpatient setting, for conditions like cancer or autoimmune diseases.

At the time of writing this article, there are two potential versions for sector-wide pharmaceutical tariffs. One is a 25% across-the-board tariff on pharmaceuticals. The other comes in the form of not yet defined reciprocal tariffs that would reflect any subsidies, including tax treatments, that foreign governments use to support specific domestic industries. These proposed tariffs would supplement tariffs already in place on all Chinese products, set at 20% for pharmaceuticals, and 25% tariffs on Canadian and Mexican products.

Although not spelled out in the announcements, the implied mechanism for accomplishing the administration’s goals can be summarized as follows:

Tariffs push up the price that foreign products cost

As that price increases, demand shifts away from the more expensive foreign products towards domestic products

Domestic firms not only gain market share, but also increase their prices, further increasing their profits

Increased profitability of domestic manufacturers then encourages domestic manufacturers to expand their capacity and new manufacturers to set up production in the U.S., increasing U.S. employment.

In this article, I discuss the extent to which this basic scenario is likely to play out as a result of contemplated tariffs by answering four questions:

How might tariffs impact drug prices?

Will tariffs lead to onshoring of pharmaceutical production?

Will drug shortages result from tariffs?

Will tariffs help de-risk drug supply chains from China?

To answer these questions, I first describe key structural dynamics in drug markets that will underpin my analysis. I distinguish between newer brand-name drugs, which are currently under patent protection, and generic off-patent drugs, which are inexpensive copies of older branded products that lost market exclusivity. I also describe the structure of the manufacturing part of drug supply chains and the role that FDA plays in overseeing manufacturing.

The analysis of the four questions suggests that prices will rise across drugs if tariffs are extended to India and Europe, but the rise will not be for the full amount of the tariffs. The tariff pressure and political considerations will lead to many onshoring announcements for branded drugs. But we should not expect to see the same for generic drug makers because the return on investment for such major capital investments will be too low and uncertain. In turn, tariff pressure for both domestic and foreign manufacturers of generics will test their already low margins, potentially leading to product discontinuations or cost cutting that erodes quality. Any production disruptions in the already fragile generic injectable markets are likely to result in shortages.

I conclude with a set of considerations for the Trump administration.

1 note

·

View note

Text

DeRISK Quantified Vulnerability Management evaluates cyber risks using business-level metrics

http://securitytc.com/TJmCm7

0 notes

Text

Smackover Lithium successfully completes derisking of DLE technology at South West Arkansas Project -

Home 2025 March 11 MagnoliaReporter.com: Smackover Lithium successfully completes derisking of DLE technology at South West Arkansas Project LEWISVILLE, Arkansas — Smackover Lithium, a joint venture (“JV”) between Standard Lithium Ltd., and Equinor, has achieved one of the last technical milestones in the development of the South West Arkansas in Lafayette and Columbia counties. The joint…

0 notes