#dark marx production co.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Dark Marx - You Don’t Bring Me Flowers (Original Soundtrack) (1987)

0 notes

Text

Kirby Right Back At Ya! Reboot Ideas

So since it's been a while, I thought of Kirby Right Back At Ya! getting a reboot/sequel. So here's what I thought of.

King Dedede gets a new company to help him (but not in the Clobbering That There Kirby way, but more in a 'I want to become a new ruler' way.)

We have a load of new characters to add, so I thought of who should be added!

Dark Matter: The newest company of Darkness' Rights Kompany or DRK for short. They don't charge for anything and often help King Dedede. Who's products backfire.

Drawcia: Maybe she can be the royal painter for King Dedede as well as a romantic love interest with Escargoon. She's very motherly towards others and often paints with others.

Paintra: Drawcia's younger sister. A bit of a snark towards the king.

Marx: A bit of a prankster and a mischievous one. But often has a softer side.

Susie: Haltmann Co. employer who often has inventions that can help Dreamland.

Magalor: An explorer of worlds. And a bit of a curious guy.

Gooey: A character who acts as Kirby's friend.

ChuChu: The southern bell.

Nago: A cat who is new in town. She's often lazy.

Pitch: Tokkori's nicer cousin. She's sassy and often a bit of a hothead and even outright blames Tokkori for everything which results them arguing.

Sectonia: A very kind queen who is obsessed with beauty both inner and outer.

Taranza: A very adventurous spider.

Adeline: A painter from another world.

Galacta Knight: A female knight who is very motherly towards Kirby and has a playful rivalry of Meta Knight.

Tokkori leaves.

--Anonymous Submission

My Comments: I like it! Mind if I borrow some of these for the children's show idea?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppression & Liberty - Simone Weil

INTRESTING CONCEPTS

‘The long-foreseen moment has arrived when capitalism is on the point of seeing its development arrested by impassable barriers.’ / ‘In whatever way we interpret the phenomenon of accumulation, it is clear that capitalism stands essentially for economic expansion and that capitalist expansion has now nearly reached the point where it will be halted by the actual limits of the earth’s surface. And yet never have there been fewer premonitory signs of the advent of socialism.’

‘Political sovereignty is nothing without economic sovereignty; which is why fascism tends to approach the Russian régime on the economic plane also, by concentrating all power, economic as well as political, in the hands of the Head of the State.’

‘The American technocrats have drawn an enchanting picture of a society in which, with the abolition of the market, technicians would find themselves all-powerful, and would use their power in such a way as to give to all the maximum leisure and comfort possible. This idea reminds us, by its utopianism, of that of enlightened despotism which our forefathers cherished. All exclusive, uncontrolled power becomes oppressive in the hands of those who have the monopoly of it. And we can already see very clearly how, within the capitalist system itself, the oppressive action of this new social stratum is taking shape.’

REFLECTIONS CONCERNING TECHNOCRACY, NATIONAL-SOCIALISM, THE U.S.S.R. AND CERTAIN OTHER MATTERS

‘Whoever accepts Lenin’s formula, “Without a revolutionary theory there is no revolutionary movement”, is compelled to accept also the fact that there is practically no revolutionary movement at the present time.’

CRITIQUE OF MARXISM

‘The whole of this doctrine, on which the Marxist conception of revolution entirely rests, is absolutely devoid of any scientific basis. In order to understand it, we must remember the Hegelian origins of Marxist thought. Hegel believed in a hidden mind at work in the universe, and that the history of the world is simply the history of this world mind, which, as in the case of everything spiritual, tends indefinitely towards perfection. Marx claimed to “put back on its feet” the Hegelian dialectic.’

ANALYSIS OF OPPRESSION

‘All religions make man into a mere instrument of Providence, and socialism, too, puts men at the service of historical progress, that is to say of productive progress. Marx, it is true, never had any other motive except a generous yearning after liberty and equality; but this yearning, once separated from the materialistic religion with which it was merged in his mind, no longer belongs to anything except what Marx contemptuously called utopian socialism. If Marx’s writings contained nothing more valuable than this, they might without loss be forgotten, at any rate except for his economic analyses.’

'Marx omits to explain why oppression is invincible as long as it is useful, why the oppressed in revolt have never succeeded in founding a non-oppressive society, whether on the basis of the productive forces of their time, or even at the cost of an economic regression which could hardly increase their misery; and, lastly, he leaves completely in the dark the general principles of the mechanism by which a given form of oppression is replaced by another What is more, not only have Marxists not solved a single one of these problems, but they have not even thought it their duty to formulate them. It has seemed to them that they had sufficiently accounted for social oppression by assuming that it corresponds to a function in the struggle against nature.’

‘From time to time the oppressed manage to drive out one team of oppressors and to replace it by another, and sometimes even to change the form of oppression; but as for abolishing oppression itself that would first mean abolishing the sources of it, abolishing all the monopolies, the magical and technical secrets that give a hold over nature, armaments, money, co-ordination of labour. Even if the oppressed were sufficiently conscious to make up their minds to do so, they could not succeed. It would be condemning themselves to immediate enslavement by the social groupings that had not carried out the same change; and even were this danger to be miraculously averted, it would be condemning themselves to death, for, once men have forgotten the methods of primitive production and have transformed the natural environment into which these fitted, they cannot recover immediate contact with nature.’

SKETCH OF CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL LIFE

‘The present social system provides no means of action other than machines for crushing humanity; whatever may be the intentions of those who use them, these machines crush and will continue to crush as long as they exist. With the industrial convict prisons constituted by the big factories, one can only produce slaves and not free workers, still less workers who would form a dominant class.’

‘Each time that the oppressed have tried to set up groups able to exercise a real influence, such groups, whether they went by the name of parties or unions, have reproduced in full within themselves all the vices of the system which they claimed to reform or abolish.’

‘The only possibility of salvation would lie in a methodical cooperation between all, strong and weak, with a view to accomplishing a progressive decentralization of social life; but the absurdity of such an idea strikes one immediately. Such a form of co-operation is impossible to imagine, even in dreams, in a civilization that is based on competition, on struggle, on war.’

FRAGMENTS

‘The bourgeoisie was only able to free itself of this religious, ecclesiastical and feudal ideology in proportion as feudal society fell into decadence. But it only purified the representation of God of the dross that had accumulated around it since the time when there had been a natural economy; it fashioned for itself a sublimated God who was no longer anything but a transcendent Reason, preceding all events and determining the direction they were to take.’

‘In Hegel’s philosophy, God still appears, under the name of “world spirit”, as mover of history and lawgiver of nature. It was not until after accomplishing its revolution that the bourgeoisie recognized in this God a creation of man himself, and that history is man’s own work.’

ON THE CONTRADICTIONS OF MARXISM

‘There is a contradiction, an obvious, glaring contradiction, between Marx’s analytic method and his conclusions / The “State machine” is oppressive by its very nature, its mechanism cannot function without crushing the citizens; the best will in the world cannot turn it into an instrument for the public good; the only way to stop it from being oppressive is to smash it. Moreover—and in this matter Marx’s analysis is less rigorous—the oppression exercised by the State machine is identical with that exercised by big industry; this machine is automatically at the service of the principal social force, namely, capital, or in other words the equipment of industrial undertakings. Those who are sacrificed to the development of industrial equipment, that is to say the proletariat, are also those who are exposed to the full brutality of the State, and the State keeps them by force in the position of slaves of the undertakings.’

‘Nothing of all this can be abolished by means of a revolution; on the contrary, all this must have disappeared before a revolution can take place; or if it does take place beforehand, it will only be an apparent revolution which will leave oppression intact or even increase it. Yet Marx reached precisely the opposite conclusion; he concluded that society was ripe for a revolution of liberation. Do not let us forget that nearly a hundred years ago he already thought such a revolution to be imminent.’

‘Manual labor, in the majority of cases, is still farther removed from the work of a craftsman, still more divested of intelligence and skill; machines are still more oppressive. The arms race calls still more imperiously for the sacrifice of the people as a whole to industrial production. The State machine develops day by day in a more monstrous fashion, becomes day by day farther and farther removed from the mass of the population, blinder, more inhuman.’

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE MAN WHO CAME TO DINNER

March 27, 1950

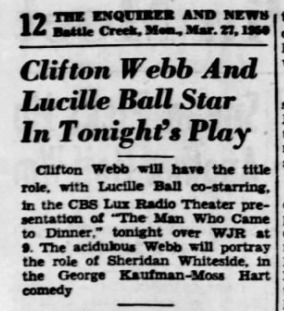

"The Man Who Came To Dinner” was a presentation of Lux Radio Theatre, broadcast on CBS Radio on March 27, 1950.

The Man Who Came to Dinner is a comedy in three by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart. It debuted on October 16, 1939, at the Music Box Theatre in New York City, where it ran until 1941, closing after 739 performances. It then enjoyed a number of New York and London revivals.

The play was adapted for a 1942 feature film, scripted by Philip G. Epstein and Julius J. Epstein and directed by William Keighley. The film featured Monty Woolley, Bette Davis, Ann Sheridan, Billie Burke, Jimmy Durante, Mary Wickes and Richard Travis.

“The Man Who Came to Dinner” was previously presented on radio by Philip Morris Playhouse on July 10, 1942. Monty Woolley, who played the leading role in the film version, starred in the adaptation. It was broadcast again by Theatre Guild on the Air on ABC Radio November 17, 1946 starring Fred Allen. In 1949, “The Man Who Came to Dinner” was produced on “The Hotpoint Holiday Hour” starring Charles Boyer, Jack Benny, Gene Kelly, Gregory Peck, Dorothy McGuire, and Rosalind Russell.

On October 13, 1954, a 60-minute adaptation was aired on the CBS Television series “The Best of Broadway.” A “Hallmark Hall of Fame” production was broadcast n November 29, 1972 starring Orson Welles, Lee Remick (Maggie Cutler), Joan Collins (Lorraine Sheldon), Don Knotts (Dr. Bradley), and Marty Feldman (Banjo). The 2000 Broadway revival was broadcast by PBS on October 7, 2000, three days after the New York production closed, and was also released on DVD.

Synopsis ~ The story is set in the small town of Mesalia, Ohio in the weeks leading to Christmas in the late 1930s. The outlandish radio wit Sheridan Whiteside is invited to dine at the house of the well-to-do factory owner Ernest Stanley and his family. But before Whiteside can enter the house, he slips on a patch of ice outside the Stanleys' front door and injures his hip. Confined to the Stanleys' home in a wheelchair, Whiteside and his retinue of show business friends turn the Stanley home upside down! But is he really injured?

This adaptation was written by S.H. Barnett. The characters eliminated for this adaptation include Richard Stanley, John, Mrs. Dexter, and Mrs. McCutcheon.

The show is hosted by William Keighley, who directed the 1942 film adaptation.

Lux Radio Theatre (1935-55) was a radio anthology series that adapted Broadway plays during its first two seasons before it began adapting films (”Lux Presents Hollywood”). These hour-long radio programs were performed live before studio audiences in Los Angeles. The series became the most popular dramatic anthology series on radio, broadcast for more than 20 years and continued on television as the Lux Video Theatre through most of the 1950s. The primary sponsor of the show was Unilever through its Lux Soap brand.

CAST

Lucille Ball (Maggie Cutler) was born on August 6, 1911 in Jamestown, New York. She began her screen career in 1933 and was known in Hollywood as ‘Queen of the B’s’ due to her many appearances in ‘B’ movies. “My Favorite Husband” eventually led to the creation of “I Love Lucy,” a television situation comedy in which she co-starred with her real-life husband, Latin bandleader Desi Arnaz. The program was phenomenally successful, allowing the couple to purchase what was once RKO Studios, re-naming it Desilu. When the show ended in 1960 (in an hour-long format known as “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour”) so did Lucy and Desi’s marriage. In 1962, hoping to keep Desilu financially solvent, Lucy returned to the sitcom format with “The Lucy Show,” which lasted six seasons. She followed that with a similar sitcom “Here’s Lucy” co-starring with her real-life children, Lucie and Desi Jr., as well as Gale Gordon, who had joined the cast of “The Lucy Show” during season two. Before her death in 1989, Lucy made one more attempt at a sitcom with “Life With Lucy,” also with Gordon.

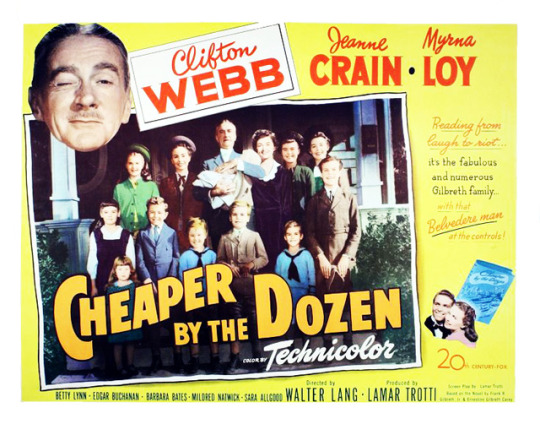

Clifton Webb (Sheridan Whiteside) had appeared with Lucille Ball in the 1946 film The Dark Corner. He was nominated for three Oscars. Webb had played the role of Sheridan Whiteside on stage for two years.

Eleanor Audley (Mrs. Stanley) appeared in several episodes of Lucille Ball’s “My Favorite Husband” as mother-in-law Letitia Cooper. Audley was first seen with Lucille Ball as Mrs. Spaulding, the first owner of the Ricardo’s Westport home in “Lucy Wants to Move to the Country” (ILL S6;E15). She returned to play one of the garden club judges in “Lucy Raises Tulips” (ILL S6;E26). Audley appeared one last time with Lucille Ball in a “Lucy Saves Milton Berle” (TLS S4;E13) in 1965.

Ruth Perrott (Sarah) played Katie the maid on Lucille Ball’s radio show “My Favorite Husband.” On “I Love Lucy” she played Mrs. Pomerantz in “Pioneer Women��� (ILL S1;E25), was one of the member of the Wednesday Afternoon Fine Arts League in “Lucy and Ethel Buy the Same Dress” (ILL S3;E3), and played a nurse when “Lucy Goes to the Hospital” (ILL S2;E16).

Betty Lou Gerson is best remembered as the voice of Cruella De Ville in the original Disney film One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961).

Stephen Dunn had appeared with Lucille Ball in Miss Grant Takes Richmond (1949).

John Milton Kennedy (Announcer)

‘DINNER’ TRIVIA

The same date as this radio adaptation (March 27, 1950), original star Monty Wooley arrived in Vancouver to perform in the play.

This broadcast aired the day after the “My Favorite Husband” episode “Liz’s Radio Script” also starring Lucille and Ruth Perrott.

Lucille Ball’s good friend and frequent co-star Mary Wickes was typecast as a nurse due to her breakthrough role as Nurse Preen in the Broadway, film, and television versions of The Man Who Came To Dinner.’ She does not play Nurse Preen in this adaptation. The character is given the first name Geraldine.

Lucille Ball previously appeared on “Lux Radio Theatre” for a November 10, 1947 adaptation of her film The Dark Corner (1946).

The first commercial talks about how Lux soap is gentle on stockings, like those worn by Betty Grable in Wabash Avenue.

The second commercial (between acts two and three) interviews actress Joan Miller, talking about the Warners picture Stage Fright, and how Lux helped keep the costumes looking great.

In the post show interviews, Clifton Webb promotes his next film Cheaper By The Dozen.

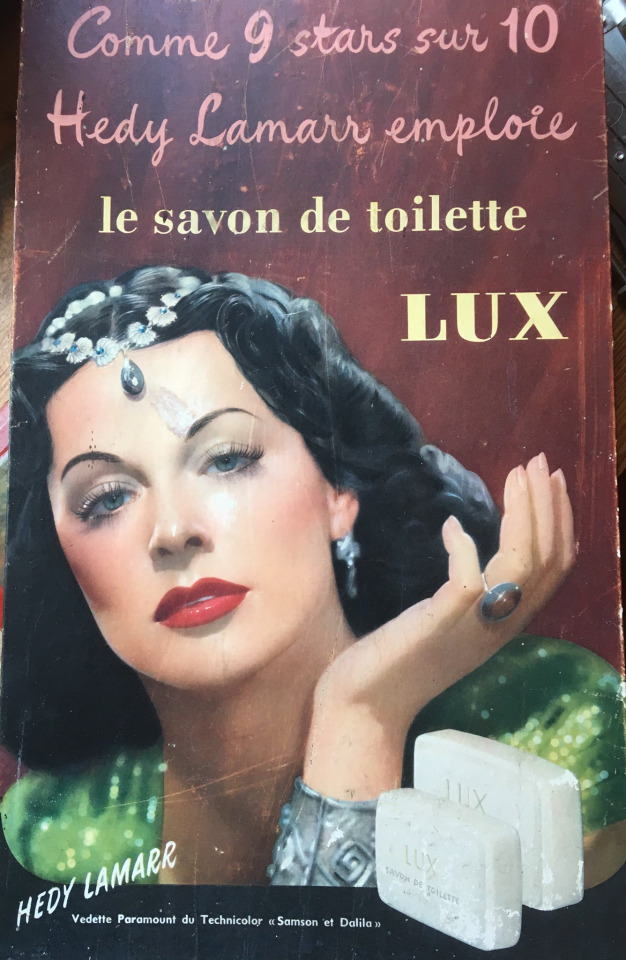

The final Lux commercial talks about how movie star Hedy Lamarr uses Lux.

The program presents a special address from president of the Red Cross, General George C. Marshall. The American Red Cross was mentioned on “My Favorite Husband” and Red Cross posters were frequently scene decorating the sets on “I Love Lucy.”

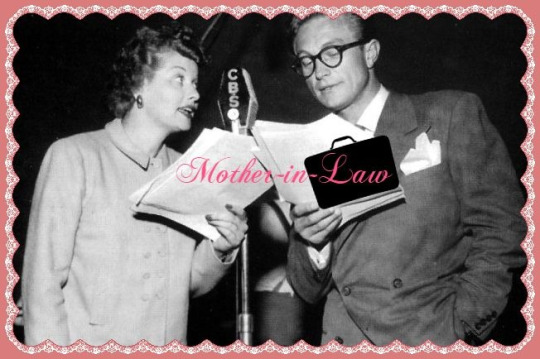

The ending of radio’s “My Favorite Husband” episode “Mother-in-Law” (November 4, 1949) starring Lucille Ball is identical to the ending of The Man Who Came To Dinner.

In “Lucy and Viv Reminisce” (TLS S6;E16) on January 1, 1968, while nursing Lucy, who has a broken leg, Viv slips and also breaks her leg. She says she feels just like a female version of The Man Who Came To Dinner.

“Vivian Sues Lucy” (TLS S1;E10) on December 3, 1962 also has a plot that resembles The Man Who Came To Dinner. Viv injures herself due to Lucy’s careless housekeeping, and is bedridden. Lucy goes out of her way to cater to her every whim, so that she won’t sue!

Although the play is fictional, it draws on real life figures and events for its inspiration.

Sheridan Whiteside was modeled on Alexander Woollcott.

Beverly Carlton was modeled on Noël Coward.

Banjo was modeled on Harpo Marx, and there is a dialogue reference to his brothers Groucho and Chico. When Sheridan Whiteside talks to Banjo on the phone, he asks him, "How are Wackko and Sloppo?"

Professor Metz was based on Dr. Gustav Eckstein of Cincinnati (with cockroaches substituted for canaries), and Lorraine Sheldon was modeled after Gertrude Lawrence.

The character of Harriet Sedley, the alias of Harriet Stanley, is an homage to Lizzie Borden. The popular jump-rope rhyme immortalizing Borden is parodied in the play.

Radio critic Dick Diespecker was not exactly enthusiastic about this adaptation.

The announcer reminds viewers that next week “Lux Radio Theatre” will present “Come To the Stable” starring Loretta Young and Hugh Marlowe

The announcer promotes Lucille Ball’s new picture Fancy Pants starring Bob Hope.

#Lucille Ball#The Man Who Came To Dinner#Clifton Webb#Eleanor Audley#My Favorite Husband#Ruth Perrott#Red Cross#Betty Lou Gerson#Hedy Lamarr#Betty Grable#Kaufman and Hart#Fancy Pants#Lux Radio Theatre#Lux#William Keighley

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbert Manfred "Zeppo" Marx (February 25, 1901 – November 30, 1979) was an American actor, comedian, theatrical agent, and engineer. He was the youngest of the five Marx Brothers and also the last to die. He appeared in the first five Marx Brothers feature films, from 1929 to 1933, but then left the act to start his second career as an engineer and theatrical agent.

Zeppo was born in Manhattan, New York City, on February 25, 1901. His parents were Sam Marx (called "Frenchie" throughout his life), and his wife, Minnie Schönberg Marx. Minnie's brother was Al Shean, who later gained fame as half of the vaudeville team Gallagher and Shean. Marx's family was Jewish. His mother was from East Frisia in Germany; and his father was a native of France, and worked as a tailor.

As with all of the Marx Brothers, different theories exist as to where Zeppo got his stage name: Groucho said in his Carnegie Hall concert in 1972 that the name was derived from the Zeppelin airship. Zeppo's ex-wife Barbara Sinatra repeated this in her 2011 book, Lady Blue Eyes: My Life with Frank. His brother Harpo offered a different account in his 1961 autobiography, Harpo Speaks!, claiming (p. 130) that there was a popular trained chimpanzee named Mr. Zippo, and that "Herbie" was tagged with the name "Zippo" because he liked to do chinups and acrobatics, as the chimp did in its act. The youngest brother objected to this nickname, and it was altered to "Zeppo". Another version of this story was that his name was changed to "Zeppo" in honor of the then popular "Zepplin". In a much later TV interview, Zeppo said that Zep is Italian-American slang for baby and as Zeppo was the youngest or baby Marx Brother, he was called Zeppo (BBC Archives).

Zeppo replaced brother Gummo in the Marx Brothers' stage act when the latter joined the army in 1918. Zeppo remained with the team and appeared in their successes in vaudeville, on Broadway, and the first five Marx Brothers films, as a straight man and romantic lead, before leaving the team. He also made a solo appearance in the Adolphe Menjou comedy A Kiss in the Dark, as Herbert Marx. It was described in newspaper reviews as a minor role.

In Lady Blue Eyes, Barbara Sinatra, Zeppo's second wife, reported that Zeppo was considered too young to perform with his brothers, and when Gummo joined the Army, Zeppo was asked to join the act as a last-minute stand-in at a show in Texas. Zeppo was supposed to go out that night with a Jewish friend of his. They were supposed to take out two Irish girls, but Zeppo had to cancel to board the train to Texas. His friend went ahead and went on the date, and was shot a few hours later when he was attacked by an Irish gang that disapproved of a Jew dating an Irish girl.

As the youngest and having grown up watching his brothers, Zeppo could fill in for and imitate any of the others when illness kept them from performing. Groucho suffered from appendicitis during the Broadway run of Animal Crackers and Zeppo filled in for him as Captain Spaulding.

"He was so good as Captain Spaulding in Animal Crackers that I would have let him play the part indefinitely, if they had allowed me to smoke in the audience", Groucho recalled. However, a comic persona of his own that could stand up against those of his brothers did not emerge. As critic Percy Hammond wrote, sympathetically, in 1928:

One of the handicaps to the thorough enjoyment of the Marx Brothers in their merry escapades is the plight of poor Zeppo Marx. While Groucho, Harpo, and Chico are hogging the show, as the phrase has it, their brother hides in an insignificant role, peeping out now and then to listen to plaudits in which he has no share.

Though Zeppo continued to play it straight in the Brothers' movies for Paramount Pictures, he occasionally got to be part of classic comedy moments in them—in particular, his role in the famous dictation scene with Groucho in Animal Crackers (1930). He also played a pivotal role as the love interest of Ruth Hall's character in Monkey Business (1931) and of Thelma Todd's in Horse Feathers (1932).

The popular assumption that Zeppo's character was superfluous was fueled in part by Groucho. According to Groucho's own story, when the group became the Three Marx Brothers, the studio wanted to trim their collective salary, and Groucho replied, "We're twice as funny without Zeppo!"

Zeppo had great mechanical skills and was largely responsible for keeping the Marx family car running. He later owned a company that machined parts for the war effort during World War II, Marman Products Co. of Inglewood, California, later acquired by the Aeroquip Company. This company produced a motorcycle, called the Marman Twin, and the Marman clamps used to hold the "Fat Man" atomic bomb inside the B-29 bomber Bockscar.[citation needed] He invented and obtained several patents for a wristwatch that monitored the pulse rate of cardiac patients and gave off an alarm if the heartbeat became irregular, and a therapeutic pad for delivering moist heat to a patient.

He also founded a large theatrical agency with his brother Gummo. During his time as a theatrical agent, Zeppo and Gummo, primarily Gummo, represented their brothers, among many others.

On April 12, 1927, Zeppo married Marion Bimberg Benda.[15] The couple adopted two children, Timothy and Thomas, in 1944 and 1945, and later divorced on May 12, 1954. On September 18, 1959, Marx married Barbara Blakeley, whose son, Bobby Oliver, he wanted to adopt and give his surname, but Bobby's father would not allow it. Bobby simply started using the last name "Marx".

Blakeley wrote in her book, Lady Blue Eyes, that Zeppo never made her convert to Judaism. Blakeley was of Methodist faith and said that Zeppo told her she became Jewish by "injection".

Blakeley also wrote in her book that Zeppo wanted to keep her son out of the picture, adding a room for him onto his estate, which was more of a guest house, as it was separated from the main residence. It was also decided that Blakeley's son would go to military school, which according to Blakeley, pleased Zeppo.

Zeppo owned a house on Halper Lake Drive in Rancho Mirage, California, which was built off the fairway of the Tamarisk Country Club. The Tamarisk Club had been set up by the Jewish community, which rivaled the gentile club called The Thunderbird. His neighbor happened to be Frank Sinatra. Zeppo later attended the Hillcrest Country Club with friends such as Sinatra, George Burns, Jack Benny, Danny Kaye, Sid Caesar, and Milton Berle.

Blakeley became involved with the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and had arranged to show Spartacus (featuring Kirk Douglas) for charity, selling tickets, and organizing a postscreening ball. At the last minute, Blakeley was told she could not have the film, so Zeppo went to the country club and spoke to Sinatra, who agreed to let him have an early release of a film he had just finished named Come Blow Your Horn. Sinatra also flew everyone involved to Palm Springs for the event.

Zeppo was a very jealous and possessive husband, and hated for Blakeley to talk to other men. Blakeley claimed that Zeppo grabbed Victor Rothschild by the throat at a country club because she was talking to him. Blakeley had caught Zeppo on many occasions with other women; the biggest incident was a party Zeppo had thrown on his yacht. After the incident, Zeppo took Blakeley to Europe, and accepted more invitations to parties when they arrived back in the States. Some of these parties were at Sinatra's compound; he often invited Blakeley and Zeppo to his house two or three times a week. Sinatra would also send champagne or wine to their home, as a nice gesture.

Blakeley and Sinatra began a love affair, unbeknownst to Zeppo. The press eventually got wind of the affair, snapping photos of Blakely and Sinatra together, or asking Blakeley questions whenever they spotted her. Both Sinatra and she denied the affair.

Zeppo and Blakeley divorced in 1973. Zeppo let Blakeley keep the 1969 Jaguar he had bought her, and agreed to pay her $1,500 (equivalent to $8,600 in 2019) per month for 10 years. Sinatra upgraded Blakeley's Jaguar to the latest model. Sinatra also gave her a house to live in. The house had belonged to Eden Hartford, Groucho Marx's third wife. Blakeley and Sinatra continued to date, and were constantly hounded by the press until the divorce between Zeppo and Blakeley became final. Blakeley and Sinatra were married in 1976.

Zeppo became ill with cancer in 1978. He sold his home, and moved to a house on the fairway off Frank Sinatra Drive. The doctors thought the cancer had gone into remission, but it returned. Zeppo called Blakeley, who accompanied him to doctor's appointments. Zeppo spent his last days with Blakeley's family.

The last surviving Marx Brother, Zeppo died of lung cancer at the Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage on November 30, 1979, at the age of 78. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean.

In his will, Zeppo left Bobby Marx a few possessions and enough money to finish law school. Both Sinatra and Blakeley attended his funeral.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Editor's note: while I've certainly been away from Can't You Read for quite a while, anyone who follows my work at ninaillingworth.com or my Patreon blog already knows that I've been writing (and podcasting) again. You can check out some of my latest essays here, here and here; to listen to the podcast I co-host with Nick Galea (No Fugazi) just click here.

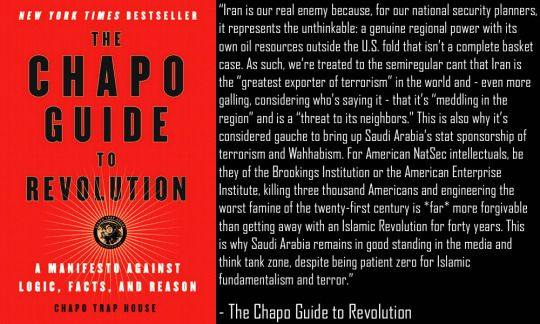

Today however I'm back on my bookworm bullsh*t with another curiously dated review of left wing literature from my extensive library of pinko pontification. In today's review, we're going to be taking a look at “The Chapo Guide to Revolution: a Manifesto Against Logic, Facts and Reason” written by five members of the popular left wing podcast “Chapo Trap House” - specifically, Felix Beiderman, Matt Christman, Brendan James, Will Menaker and Virgil Texas.

Baby Steps up the Ramparts

It is I will theorize, utterly impossible to write a review about the Chapo Trap House book without engaging in the extremely online, three-sided culture war that has sprung up around both “the Chapos” themselves and the enormously popular podcast they host. In light of the fact that seemingly everyone on the internet who detests the show regard the Chapos as slovenly crackpot losers born on third base and podcasting from mom's basement, it really is alarming how much digital ink has been spilled about the various types of “threat” to all that is good and holy this simple irony-infused podcast supposedly represents. While I intend to largely sidestep that discussion by focusing entirely on the book and not the podcast (which I don't listen to regularly, to be honest with you), I accept that virtually nobody reading this is going to be happy unless I do something to address the elephant in the room, so here goes:

Neera Tanden and her winged neoliberal monkeys can eat sh*t, but extremely online leftists have a point that the Chapos themselves occasionally skirt the line between mockingly ironic reactionary thought and just plain old reactionary thought; although this is not particularly alarming to me because they're Americans and America itself is a breeding ground for reactionary ideas – decolonizing your mind is a process and I'm pretty sure it's one I myself am also engaging in still every single day of my life at this point. Importantly, in my opinion this failing does not make them cryptofascists so much as the product of American affluence; I'm having a hard time understanding how teaching Marx and Zinn to Twitter reply guys serves the fascist agenda in any meaningful way. While I obviously can't pretend to know another person's heart, in my opinion the Chapo boys are definitely leftists but they're obviously not labor class and yes it's a little hard to explain away the group's loose affiliation with the (objectively strasserist) Red Scare podcast through co-host Amber A'Lee Frost - but I'm not going to waste a couple thousand words trying to untangle Brooklyn independent media drama from half a country away and besides, Amber didn’t write this book. Despite these critiques however, I think it's important to note that under no circumstances am I prepared to accept the argument that with fascists to the right of me, and lanyards, um also to the right, the real problem here is... Chapo Trap House.

Ok, with that out of the way let's dive right in and talk about the question I think most folks who've written about The Chapo Guide to Revolution have largely failed to grasp – namely, what kind of book is it precisely? Combining elements of comedy, playful online trolling, historical analysis, political theory and good old-fashioned cross platform promotional marketing, the book has often lead critics to compare it to catch-all comedic efforts like Joe Stewart's “America” or even humorous men’s lifestyle advice texts like “Max Headroom's Guide to Life.” This is I think an essential misreading of the fundamentally earnest and direct tone the book actually takes in its efforts to reach a fledgling audience growing more receptive to left wing ideas. The Chapo Guide to Revolution is, as the cover says, a manifesto; but rather than serving as the mission statement for a particular formed political ideology, the Chapos have written an extremely effective, entry-level argument for why labor-class millennials should be leftists – and, of course, why they should listen to Chapo Trap House; this is still a cross-promotional work after all.

Naturally as befits a book about a comedy podcast, albeit a very political one, the Chapo Guide to Revolution is an extremely funny book that does a remarkable job translating the type of caustic online humor previously only found in left wing Twitter circles, onto the written page. While its certainly true that this quirky style of comedy can be a little difficult to grasp for the uninitiated, and typically a cross-promotional work of this type will get bogged down in self-referential humor and inside jokes, the book mostly avoids this trap by sticking with the basics and assuming that the reader has literally never heard an episode of Chapo Trap House, which in turn makes the humor fairly universal and extremely accessible – at least for anyone under the age of fifty. This endeavor is greatly aided by the dark and dystopian, yet hilariously eviscerating art of Eli Valley; a man who himself has since become one of the leading left wing critics of establishment power online through his extremely provocative sketches and ink work.

The truth however is that if the Chapo Guide to Revolution was merely just a funny book, I wouldn't be reviewing it here today. No, the reason this book is worth writing about at all lies in the fact that underneath all the jokes, taunts and “half-baked Marxism” lies an objectively brilliant work of historical analysis, cultural critique and left wing political theory – albeit an unfocused theory that borrows heavily from half a dozen functionally incompatible left wing thinkers and literary giants, but a fundamentally serious work of political philosophy nonetheless.

Yes, that's correct; I said brilliant. Where think-tank minions and neoliberal swine in the corporate media see a petulant pinko tantrum, and online leftist academics see privileged dudebros appropriating Marx (poorly), I see a brilliant and yet stealthy synthesis of political theories, historical analysis and organizational ideas originally presented by writers like Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky and Thomas Frank. Drawing on historical theories from Marx, Gramsci and Rocker, the Chapos have cobbled together a rudimentary political philosophy that represents a crude and yet promising welding of anarchist concepts about labor, Marxist concepts about economics and democratic socialist concepts about politics, collected together under the generic banner of “socialism.”

At this point some of you are undoubtedly snickering, but please bear with me for a moment here because what the Chapos (or their ghostwriter) have done in this book is truly a marvelous thing to behold precisely because you can't see it unless you're paying close attention. By positioning The Chapo Guide to Revolution as both a comedic work and an introductory level text, the authors have created a sort of unique crash course in left wing history, geopolitics, philosophy and political theory for a newly awakened generation of Americans who find themselves increasingly politicized whether they like it or not.

Underneath the acerbic millennial humor, “extremely online” diction and unrelenting waves of sarcasm, The Chapo Guide to Revolution is also a surprisingly accurate “CliffsNotes” style textbook presentation of multiple broad-based social science subjects – here are just a few examples:

In “Chapter One: World” the book presents a rudimentary and yet deliciously insightful history of post-World War II American empire that draws on authors like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky, with a touch of contemporary writers like Greg Grandin and Naomi Klein. In particular the attention devoted to condensing the target audience's formative experiences with empire like the War on Terror, the invasion of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan, into a short and coherent narrative that can be easily shared with other novice political observers makes this book an invaluable resource for budding millennial leftists Additionally, while it certainly might have been an accident, the Chapos' choice to wrap this “Pig Empire geopolitics for newbs” lesson in a protracted joke about America as an extremely ruthless corporate startup at least touches on ideas presented by writers like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Sheldon Wollin (or Chris Hedges repeating Sheldon Wolin), Joel Bakan, Rosa Luxemburg and others.

In Chapters Two and Three, entitled “Libs” and “Cons” respectively, the authors conduct a remarkably thorough political science lesson on the two major mainstream political “ideologies” in American culture, including both a rough outline of their history and their modern calcification inside the Democratic and Republican parties. Of course both of these sections rely heavily on the personal experiences of the authors growing up in a politicized America, but these discussions also dip into the works of Thomas Frank and Cory Robin to explore and critique the liberal and conservative political mindset respectively; in particular the Chapos summary of Robin's work on the conservative worship of hierarchies is an inspired distillation. More importantly however, the Chapos also expose the way in which these two ideologies represent a false dichotomy within the greater confines of a larger capitalist socioeconomic order; which is of course a (still absolutely correct) idea straight out of the works of Karl Marx.

In Chapter Six, appropriately entitled “work” the authors engaged in a disarmingly earnest discussion about wage slavery, the false promises of the protestant work ethic and the history of terrible jobs available to the labor class under various iterations of the capitalist project. This is followed by a humorous, but dystopian review of what future jobs might look like if the neoliberal socioeconomic order continues on as it has so far, and an extremely brief but sincerely argued pitch for completely transforming the role of work in society through some from of technologically assisted anarcho-communism. This last idea is admittedly a little half-baked but you have to admire their balls when the Chapo boys flatly call for a three hour workday; a position that will undoubtedly be popular with the labor class who're currently engaged in all those sh*tty jobs the book describes earlier in the chapter. Once again this synthesis of left wing ideas about work does represent a new and unique formulation, but despite the humorous and original content you can also clearly see the influence of anarchist writers like Kropotkin, Rocker and Goldman in this chapter, as well as contemporary authors like David Graeber and Mark Blyth.

Unfortunately, if there is a downside to writing a brilliantly subversive comedy book that functions as a “my little lefty politics primer” for politically awakening millennials, it's that you simply don't have the space for an intellectually rigorous examination of all the ideas you're sharing – there is after all a big difference between reading the Cliff Notes version of Zinn, Chomsky or Marx, and reading the original theories in their full form. Furthermore, the individual life experiences, idiosyncrasies and humor styles of the authors do at times bleed into the text in a way that I personally suspect was detrimental to the overall analysis. Here's a short list of “sour notes” I found in this otherwise remarkable book:

From what I have listened to of the Chapo Trap House podcast, it has always been my impression that the Chapos were particularly effective critics of American corporate media, so I was a little disappointed that the chapter on media in The Chapo Guide to Revolution was a fairly tepid and narrow discussion about (admittedly vapid) bloggers turned celebrated pundits. Don't get me wrong, I'm sure power dunking on the likes of Matty Yglesias, Meagan McArdell and Andrew Sullivan was viscerally satisfying for the book's target audience, but there's really not much of a broader critique of the media's ideological role in American capitalism and culture here like one would find in Herman & Chomsky's “Manufacturing Consent”, Matt Taibbi's “Hate Inc” or Michael Parenti's “Inventing Reality.” This absence I fear has the tragic side effect of reinforcing the idea the American corporate media sucks because egg-shaped moron bougie pundits are bad at their job and not because of the inherent failings of the for-profit media model and the institution's true role as an ideological shepherd keeping the masses aligned with the goals of elite capital and the ruling classes – almost exclusively against the bests interests of the labor class.

The introduction is written in what I can only assume is a sarcastic imitation of right-leaning self improvement books with a touch of Tyler Durden's Fight Club ethos thrown in; this might have been a better choice in a completely different book but it's largely out of place with the rest of this book. At this point I should also say that the best part about the Kidzone intermission is that it was only two pages long. Needless to say, neither one of these sections did anything for me whatsoever.

While it's entirely possible that at forty-three years of age, I'm simply too old to really get the “millenialness” of the chapter on Culture, the simple truth is that I found most of it to be a fairly useless examination of pop culture influences the Chapos hold in reasonably high esteem. As someone who isn't particularly engaged in watching lengthy television series or regularly playing video games, I really couldn't dig into most of the material presented and the less said about the art jokes and the bizarre absurdist discussion of elevator brands, the better. There is however one rather notable exception here in the brief essay on The Sorkin Mindset, which is an objectively brilliant evisceration of the liberal obsession with the West Wing and the tragic effect that obsession has had on Democratic Party politics – this really could have gone in the chapter on “Libs” because it's that valuable of a tool for understanding and critiquing the modern liberal lanyard worldview. Finally I guess I should note that while the Chapo boys' insightful critique of the vapid “prestige TV” phenomenon is both interesting and correct, it really only “matters” if you're a consumer of these types of series – and I'm not.

While I certainly understand the authors' decision to use their notes section to preemptively debunk bullsh*t complaints about the more outrageous accusations they level against the American establishment, I would have liked to see a “recommended reading” section. It is very clear that the Chapos have a reasonably strong background in imperial history, political science and labor theory and I feel like pointing readers towards writers who expand on the theories they summarize in The Chapo Guide to Revolution might have been a better use of space than printing links to old internet articles bad faith actors will never type into a search engine anyway.

Although it might seem like there was more about the book I didn't like, than I did, this is a little misleading – the first three chapters of The Chapo Guide to Revolution are pure fire and comprise over half of the volume. If you throw in the brilliant chapter about work and labor theory, the overall package is far more substance than style, despite the fact that it remains humorous and a little bit edgy throughout the book. While it's certainly fair to say that an introductory primer on why you should be a leftist for newly-politicized millennials isn't a must-read for everyone, the simple truth is that the vast majority of online leftists I know could learn a thing or two from this rudimentary synthesis of various left wing ideas into the seeds of a working, modern political ideology compatible with a uniquely Americanized, millennial left.

While no three hundred page comedy book written by five podcasters from Brooklyn is going to teach you everything there is to know about socialism and left wing ideology, there's something to be said for offering an accessible, entry-level alternative tailor-made for a target demographic already being heavily recruited by the fascists. As a starting point for exploring left wing political thought, you could do a lot worse than The Chapo Guide to Revolution and for a generation of kids who've mostly been encouraged to be passive accomplices to their own subjugation while blaming their misery on anyone even more powerless than they are, there is perhaps nothing more valuable than a condensed narrative that explores how to even think about another way to live.

Remarkably, this book finds a way to deliver on that monumental task while simultaneously failing to grasp one single relevant thing about the cherished American novel Moby Dick. Despite this infuriating literary myopia and insolence, this still might literally be the best book ever written for young American leftists who simply aren't going to spend ten years reading academic literature written by dead white guys from Germany and Russia. - nina illingworth Independent writer, critic and analyst with a left focus. Please help me fight corporate censorship by sharing my articles with your friends online! You can find my work at ninaillingworth.com, Can’t You Read, Media Madness and my Patreon Blog Updates available on Twitter, Mastodon and Facebook. Podcast at “No Fugazi” on Soundcloud. Chat with fellow readers online at Anarcho Nina Writes on Discord!

#chapo trap house#book review#The Chapo Guide to Revolution#left wing politics#geopolitics#humor#leftism#introduction to leftism#Noam Chomsky#Howard Zinn#Thomas Frank#Cory Robin#culture war#politics#news#media#bloggers#savage burns

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

... claws my way up from hell once more and vomits onto the dash.... hello. its nora. i used to write rory bergstrom, but if u were here before that u might remember me as greta or alma putnam or..... som1 else.... an endless carousel of trash children..... this is finn, who i actually wrote for an early version of this rp abt 5yrs back now...... grits teeth..... so forgive me if im rusty i havent written him in a long time but seein honey boy gave me a lotta finn muse n im keen to get Back On The Horse yeehaww...

DYLAN O’BRIEN / CIS-MALE — don’t look now, but is that finn o’callaghan i see? the 25 year old criminology and forensic studies student is in their graduate year of study year and he is a rochester alum. i hear they can be judicious, adroit, morose and cynical, so maybe keep that in mind. i bet he will make a name for themselves living off-campus. ( nora. 24. gmt. she/her )

shakes my tin can a humble pinterest, ma’am....

finn has a bio pasted at the bottom (n written in like.... 2015.... gross) but it’s long so if u don’t wanna read it here’s the sparknotes summary..... anyway this was written years ago n a lot of it seems really cliche and lame now but..... we accept the trash we think we deserve

grumpy, ugly sweater wearing, tech-savvy grandpa

very dry sense of humour and embraces nihilism.

if ron swanson and april ludgate had a baby it would be finn

he was raised in derry, just south of dublin.

from a big family. elder sister called sinead. he also has a younger sister (aoife), a younger brother (colm), and a collie named lassie because his father lovs cliches (finn hates cliches but loves his dog).

his father was a pub landlord and his mother worked at the market sellin fruit n veg when they met but got a job as a medical receptionist when she had kids cos it meant she cld be there with them in the day and work nights.

his parents met when they were p young and fiesty and rushed into marriage cos they were catholic n just wanted to have sex. his family were literally dirt-poor, but they had a lot of love i guess

hmmmmm his relationship w his father wasn’t the best cos i can’t write character who have healthy relationships w their parents throws up a peace sign. yh, had a pretty emotionally distant, alcoholic violent father n so gets a lot of his bad habits i.e. drinking as a coping mechanism and poor anger management from him BUT anyway

as a kid he was never very motivated in class, he always had a nervous itch to be off somewhere doing something else. struggled under government austerity bcso there just wasn’t the resources to support low income families where the kids had learning difficulties n needed support. fuck the tories am i right

his mum suggested he try sports to help w his restless energy but he was never any good at football so he took up boxing and tap dance instead. he took to tap dancing like a fish to fuckin water. as adhd n found this as a really good way to use his excess energy in a creative way

had a few run ins with the police in his early teens for spray painting and graffiti, but he straightened himself out n now actually considering becoming a detective inspector??? cops are pigs.

he had a youtube channel where he posted videos of him tapdancing and breakdancing as a kid, basically would be a tiktok boy nowadays, n had like... a small fanbase in his early teens. attended several open auditions unsuccessfully, until he was finally cast in billy eliot when he was fifteen.

during billy eliot he began dating an italian dancer called nina. they became dance partners soon after and toured across the republic with various different shows (inc riverdance lol the classic irish stereotype). their relationship was p toxic tbh, they were both very hot tempered people and just used to argue and fight all the time.

he went semi-pro at tap dancing, and nina couldn’t stand being second best so she moved back to italy with her family. ignored his texts, phone calls, etc, eventually he was driven to the point where he used his savings to buy a plane ticket, showed up at her house and she was like wtf?? freaked out and filed a restraining order accusing him of stalking.

he was fined for harassment and then returned home to derry, but after the incident with nina he quit dancing for good and finished his leaving cert before heading to university in the US to get as far away from nina and his past life as poss. and basically since he quit dancing to study forensics (death kink. finn cant get enough of that morgue. just walks around sayin beat u) he’s become a massive grump and jsut doesn’t see the good in people any more.

u’ll find finn in an old man bar drinking whiskey bc he is in fact an old man at heart or sat on his roof smoking a joint, drawing wolves and lions and skeletons and shit, playing call of duty or getting blazed or at the corner of the room in a house party ignoring everyone and scrolling through twitter. is a massive e-boy. always up-to-date on memes and internet slang. has reddit as an app on his phone

not very good at communication. rather than solve his issues by talking, he’d prefer to just solve them through fighting or running away from his problems hence why he has come halfway across the world to get away from an issue which probs cld have been solved w a few apology emails.

takes a lot to phase him, but when his beserk button gets pressed he can become a bit pugnacious like an angry lil rottweiler. in his undergrad he was in a few fist fights but doesn’t really do tht any more as he doesn’t condone violence.

in the previous version of this rp he was hospitalised like 5 times. pls, give my son a break. stop tryin to kill him. he literaly got a bottle smashed over his head and bled out all over his favourite angora rug that was the only light of his life

works at the campus coffee shop n always whines about how he’s a slave to capitalism. always smells of coffee

lives off campus with an elderly woman named Marianne, and basically gets reduced rent bcos he makes her dinner / keeps her company. they have a great bond

fan of karl marx. v big on socialism

insomniac with chronic nosebleeds

cynical about everything. too much of a fight club character 4 his own good n has his head up tyler durden’s sphincter

always confused or annoyed

statistics

basic information

full name: finnegan seamus o'callaghan nickname(s): finn age: 25 astrological sign: aries hometown: derry, ireland occupation: phd student / former street entertainer fatal flaw: cynicism positives: self-reliant, street smart, relaxed, intelligent, spontaneous, brave, independent, reliable, trustworthy, loyal. negatives: hostile, impulsive, stubborn, brooding, pugnacious, untrusting, cynical, enigmatic, reserved.

physical

colouring: medium hair colour: dark brown, almost black eye colour: brown height: 5’9” weight: 69kg build: tall, athletic voice: subtle irish accent, low, smooth. dominant hand: left scar(s): one on the left side of his ribs from a knife wound that he doesn’t remember getting cos he was drunk distinguishing marks: freckles, tattoo of a wolf howling at a moon allergies: pollen and the full spectrum of human emotion alcohol tolerance: high drunken behaviour: he becomes friendlier, far more conversational than when sober, flirtier, and generally more self-confident.

psychological

dreams/goals: self-fulfilment, travel the globe, experience life in its most alive and technicoloured version, make documentary films, help the vulnerable in society, grow as a human being.

skills: jack-of-all-trades, very fast runner, good at thieving things, talented tap dancer, good in crisis situations, dab-hand at mechanics, musically-intelligent, can throw a mean right hook and very capable of defending himself, can roll a cigarette, memorises quotes and passages of literature with ease, can light a match with his teeth.

likes: the smell of the earth after rain, poetry, cigarettes, shakespeare, whiskey, tattoos, travelling, ac/dc, deep conversations, leather jackets, open spaces, the smell of petrol, early noughties ‘emo phase’ anthems.

dislikes: the government, parties, rules, donald trump, children, apple products, weddings, people in general, small talk, dependency, loneliness, pop music, public transport, justin timberlake, uncertainty.fears: fear itself, drowning alignment: true neutral mbti: istp – “while their mechanical tendencies can make them appear simple at a glance, istps are actually quite enigmatic. friendly but very private, calm but suddenly spontaneous, extremely curious but unable to stay focused on formal studies, istp personalities can be a challenge to predict, even by their friends and loved ones. istps can seem very loyal and steady for a while, but they tend to build up a store of impulsive energy that explodes without warning, taking their interests in bold new directions.” (via 16personalities.com)

full bio (lame as fuck written years ago..... pleathe...)

tw homophobia

born in quigley’s pub on the backstreets of sunny dublin, young finnegan o'callaghan was thrown kicking and screaming into the rowdy suburbs of irish drinking culture. the son of a landlord and a fishwife, he never had much in the way of earnings, but there was never a dull moment in his lively estate, where asbo’s thrived, but community spirit conquered. at school, finn was pegged as lazy and unmotivated, though truly his dyslexia made it hard for the boy to learn in the same environment of his peers and only made him more closed-off in class. struggling with anger management, finn moved from school to school, unable to fit the cookie-cutter mould that school enforced on him, though whilst academic studies were of little interest to the boy, he soon found his true passions lay in recreational activities. immersed into the joys of sport from as young as four, finn was an ardent munster fan and anticipated nothing more than the day he could finally fit into his brother’s old pair of rugby boots.

his calling finally came unexpectedly, not in the form of rugger, but through dance. to learn to express himself in a non-academic way, he began tap dancing, finding therapy in the beat of his soles against the cracked kitchen tiles (much to his mother’s disgrace). it wasn’t a conscious choice, finn just realised one day that dance was something that made him feel. a king of the streets, finn made his fortune on those cobbled pavements – dancing and drawing to earn his keep. by default, finn became a street artist, each penny he earned from his chalk drawings saved in a jam jar towards buying his first pair of tap shoes. though many of his less-than-amiable neighbours called him a nancy and a gaybo, finn refused to quit at his somewhat ‘unconventional’ hobby, for the young scrapper found energy, life, and released anger through the rhythm of tap. soon he branched out into street dance, hip hop, break dancing, lyrical, his days spent smacking his scuffed feet against the broken patio into the night.

when he was thirteen he took up boxing, and as expected, his newfound ‘macho’ pastime conflicted with his dancing. the boxers called him ‘soft’; the dancers called him ‘inelegant’. he felt like two different people; having to choose between interests was like being handed a knife and asked to which half of himself he wished to cut away. he couldn’t afford professional training in dance, with most schools based in england and limited scholarships available. instead, he made the street his studio, racking up a small fanbase on youtube. when he was fifteen he made his debut in billy eliot at the olympia theatre in dublin. enter nina de souza, talented, beautiful and italian; ballet dancer, operatic singer, genius whiz kid, and spoiled brat. she was selfish, conceited, hell bent on getting her own way, and every director’s nightmare. finn fell for her like a house of cards. he’d always had a soft spot for girls who meant trouble. and so their hellish courtship began.

by the time they were seventeen, the two young swans had danced in every playhouse across the republic. they were known in theatres across the country for their tempestuous personalities, their raging arguments with one another, their tendency to drop out of shows altogether without any notice, yet the money kept rolling in and the audiences continued to grow. for three years, their families continued to put up with their hysterical fights followed by passionate reconciliations. he was too possessive, and she was too wild. their carcrash of a relationship finally came to a catastrophic halt when nina broke off the whole affair and returned to italy with her family. for months finn tried to contact her, yet his phone calls, texts, facebook messages were always ignored, until finally he was driven to drastic measures and used his savings to get a plane to her home town. when finn turned up uninvited at nina’s house she freaked out – and rightly so – she contacted her agent, accused him of stalking her, and had a restraining order placed against him. finn was arrested, held in a station overnight, and charged with harassment before he was allowed to return to dublin.

after the incident with nina, finn lost the fight in his eyes. he became far more hostile, far less likely to retaliate with his own fists, and picked fights not for the thrill of feeling his own fists pummel another into a wall, but for the sensation of his own brittle bones cracking. he dropped his tap shoes in a dumpster, stopped talking to his friends, followed his father’s advice and went back to school to complete his leaving certificate. a few short months later, and finn was packing his bags, saying his bittersweet goodbyes, and travelling half-way across the globe to be as far away as possible from his past self, his mess of a life, and most of all nina. it seemed somehow ironic that the boy who had been cautioned by the garda so much during his youth for spray painting, busking without a liscence, and raucous parties would become the grumpy, aloof overseas student studying a degree in criminology; that his once reckless spirit could be crushed so easily.

of all things that finn could be called, straightforward would never be one of them. ever since his first days in atticus, the boy was pegged as hostile, hot-headed, cynical, rude. he seemed to spend more time in his thoughts than engaging in conversation. like a ticking time-bomb, finn’s anger was of the calm kind, liable to explode without a moment’s noticed. his unpredictable personality make him something of an enigma to those who aren’t amiable with the lad, though hostile as he may appear, he harvests a good heart. loyalty lies at the centre of his affections, and whilst his friends are few in number, he makes a lifelong partner. somewhere within finn, there’s still some fight left, but mostly he has recognised that his hedonistic lifestyle did little to leave him fulfilled – mostly, it just emptied him out – and over his three years at university has resigned himself to a nihilistic predicament.

if u wanna plot with me pls pls pls im me or like this post!! i am always game for plots i love em so excited to write with you all here r some ideas

study buddies. finn is now a phd student so has to start takin shit seriously. he gon be in the library every day doing that independent study. if he had ppl who were also regular library goers n they get each other coffees to save time.... tht wld be sweet

ppl who love techno dj sets and going super hard on the weekends!!! fuck yea

friends with benefits. exes on bad terms. ppl he tried to date but couldnt because he’s always emotionally hung up on someone else. spicy hook up plots

ppl he met touring?? maybe ppl who were also in the entertainment industry..... anyone got a character who is ex circus hit me up

does anyone else study criminology / forensics / criminal psych / law? phd students sometimes lecture so he cld be an assistant lecturer / tutor if ur character is in a younger year

gamers !!! social recluses !!! hermits !!

finn goes to the skatepark and all the young boys there think he’s a gradnpa which he is!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sherry Amott Creative Supervisor on The Dark Crystal.

Sherry Amott lent her theater design and production expertise to the Henson Company throughout the 70s and 80s. She was among the many Muppet designers for The Muppet Show and The Muppet Movie, and worked at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop on various characters for The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth, and Dreamchild. She was Head of Fabrication of Audrey II for the Frank Oz film Little Shop of Horrors.

Amott worked on Sesame Street as well, creating Linda’s pet dog Barkley and designing the outfits for the cover of the famous Sesame Street Fever LP, among other feats.

After “Little Shop of Horrors” Amott married British filmmaker, director and editor John Tippey. Their son Jake was born in London in 1986. Post-Henson she worked briefly as a children’s and young adult librarian before moving to Cincinnati to work for Horizon Productions as a producer, and later, Creative Director. Her freelance work included character and costume design and fabrication for theatre, video and interactive projects. She co-produced and designed an interactive CD-ROM and website for artist January Marx Knoop. In 2007 Sherry Amott Tippey became Creative Director at Curtis, Incorporated, a Visual Communications firm in Cincinnati where she enjoys writing, producing, project management, multimedia production and web design.

Sherry sings with the Kentucky Symphony Orchestra Chorale, BACHorale, October Festival Choir, and Voices of Freedom.

Jake is lead guitar, singer and songwriter for The Frankl Project. Recent photos of The Frankl Project opening Riotfest at the House of Blues in Chicago are posted here.

CREDITS Designer The Muppet Show: The Germ, others Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas The Muppet Movie Sesame Street: Barkley Sesame Street Fever: Muppet disco attire The Dark Crystal: Creative supervisor; Creature design and fabrication (Mystics, Pod People, and Slaves) Dreamchild: Mechanical design assistant designer Labyrinth: Senior animatronic designer; Creature workshop teams: The Chilly Downs, Junk Lady, The Wiseman Performer Labyrinth: Firey 3 (assistant)

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

The same old stupid game

I’ve recently had the misfortune to come across a few articles, one by Inez Feltscher Stepman of The Federalist and David Satter, “senior fellow” at the so-called Hudson Institute. Naturally, as reactionary commentators for reactionary propaganda outlets, their tripe is full of lies, half-truths, and glaring omissions meant to serve their biases. It’s the normal bourgeois playbook for libeling Communism.

I’m not a tremendous fan of the Soviet Union, or the manner of “actually existing Socialism” that developed there, but I feel compelled to refute this nonsense not only because it’s dishonest, or that it’s a perversion of the actual history, but at least because the Soviet Union is the dead horse reactionaries love to beat when Socialism as a subject is discussed.

I came across Stepman’s tripe after seeing someone post the following cap from her twitter:

galaxymind.jpg

I try not to go by screen caps alone. A favorite of /pol/’s tactics is taking things out of context to craft their own narrative around events, which often have little or any basis in reality. Given the... content of this tweet, the meaning seems pretty obvious, but I try to err on the side of caution, so I ran her name through my sophisticated crime computer and was immediately directed to her posts at The Federalist. The results weren’t particularly impressive, but something did jump out to me: “The Biggest Legacy Of International Women’s Day Is Communism.”

I had a feeling it was going to be painful given the title, and I wasn’t wrong.

As a Communist, I have a soft spot for International Working Women’s day, as the event was originally known. Women have played a special role in the history of labor organization and revolutionary activity, and today Capitalism derives much of its profit from the relentless, merciless exploitation of the female gender in its various forms.

How progressive.

Even in the so-called First World, I’ve seen my female friends and co-workers mistreated and immiserated by the Capitalist system in ways unique to their kind. I celebrate IWWD because in its ideal form, it is an opportunity not only for women to build solidarity between one another (which is often sorely lacking) but for men to show their support, and build solidarity with the other gender (and vice versa on International Working Men’s Day). It’s an opportunity to remember the work of women past, the progress we’ve been able to achieve together, and lay the ground work for a better future for us all. The purpose of the day is to pay special attention to the circumstances of our working sisters, but at its heart it’s a day to reaffirm our dedication to the cause of true egalitarianism, and not the false mirage offered by bourgeois “feminists” that demand more female CEOs while ignoring the Mexican nannies they underpay to raise their children for them, or pushing expensive shirts for “charity,” assembled in stifling and dangerous sweat shops by the thousands of women they actually should be fighting for.

Naturally, Stepman starts off strong.

Leon Trotsky, of icepick fame, wrote afterwards: “We did not imagine that this ‘Women’s Day’ would inaugurate the revolution. Revolutionary actions were foreseen but without date. But in morning, despite the orders to the contrary, textile workers left their work in several factories and sent delegates to ask for support of the strike … which led to mass strike … all went out into the streets.”

What a splendid introduction. I wonder if she characterizes so “Abraham Lincoln, of getting-shot-in-the-back-of-the-head fame.” She links to a Fortune article, which in turn links to an apparently defunct World March for Women site. Usually, not linking directly to the source material (when possible) is a strong indicator of chicanery, to say the least. After a bit of searching, I was able to track it down to Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, where the actual quote goes like so:

THE 23rd of February was International Woman’s Day. The social-democratic circles had intended to mark this day in a general manner: by meetings, speeches, leaflets. It had not occurred to anyone that it might become the first day of the revolution. Not a single organisation called for strikes on that day. What is more, even a Bolshevik organisation, and a most militant one – the Vyborg borough committee, all workers – was opposing strikes. The temper of the masses, according to Kayurov, one of the leaders in the workers’ district, was very tense; any strike would threaten to turn into an open fight. But since the committee thought the time unripe for militant action – the party not strong enough and the workers having too few contacts with the soldiers – they decided not to call for strikes but to prepare for revolutionary action at some indefinite time in the future. Such was the course followed by the committee on the eve of the 23rd of February, and everyone seemed to accept it. On the following morning, however, in spite of all directives, the women textile workers in several factories went on strike, and sent delegates to the metalworkers with an appeal for support. “With reluctance,” writes Kayurov, “the Bolsheviks agreed to this, and they were followed by the workers–Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. But once there is a mass strike, one must call everybody into the streets and take the lead.” Such was Kayurov’s decision, and the Vyborg committee had to agree to it. “The idea of going into the streets had long been ripening among the workers; only at that moment nobody imagined where it would lead.” Let us keep in mind this testimony of a participant, important for understanding the mechanics of the events.

Certainly lends a different perspective to the “quote,” I think, but we can’t show that the Bolsheviks weren’t power-mad, bloodthirsty tyrants now, can we? Of course, progressing through the article we find the same ridiculous libels that we usually find.

That revolution, which caused Russia to exit WWI and brought Vladimir Lenin to power, started the chain of events that eventually lead to the slaughter of as many as 100 million people under the banner of Communism.

To say that the revolution “caused Russia to exit WWI” is a half-truth at best. Russia was suffering severely from the deprivations caused by the titanic struggle with Germany, for which Russia was horribly unprepared. All the nonsense that reactionaries like this try to pin on the Soviets--not enough rifles or ammunition for their troops, mass human wave tactics, shooting ‘cowards’ retreating without orders, etc--was committed by Tsarist Russia. By the end of the war, due to incompetence among the aristocracy and general staff, unpreparedness either militarily or economically, intervention by the Tsar himself in military affairs on the Eastern Front, and the terrific conditions the Russian soldiers and peasantry were exposed to, Russia would see more than four-million of its people dead. Russia was incapable of continued involvement in the war. The Bolsheviks end up signing away a vast expanse of Russia to buy peace, which is exactly what the people wanted, and what the parliamentary government refused to give them.

The “100 Million Dead” is the usual smear, but I’ll return to that shortly.

Obviously, few people celebrating International Women’s Day in 2018 intend to glorify Communism’s dark history. But the day still retains the essence of its Marxist roots by encouraging women to think of themselves as a homogenous [sic] class with discrete common interests, in opposition to men’s.

Here the brainlet further exposes herself for the pseudo-intellectual that she is. There’s a lot to be said about Marxism and its history with “Feminism.” This sort of characterization reveals how little of either Stepman understands of either.

In Marxist terms, men and women don’t constitute separate classes within society. In short, one’s social class is determined by one’s relationship to the means of production, i.e., do you have to work for a living, or do you live from others working necessary resources to which you control by monopoly? There are numerous divisions possible based on how you want to slice it, but generally you can say that there are the bourgeois, those that own the things people need to live, and the proletariat, those that earn a wage working for the bourgeois. From the Marxist perspective, men and women inhabit the same class based on their material relations, but nowhere are their assumed to be “homogenous,” or that they have universal or even necessarily opposed interests. As workers, they have a united interest in overthrowing the capitalist system of bourgeois ownership that keeps them in bondage, but to treat people as a homogeneous mass with all the same needs and goals runs directly counter to the materialist analysis on which Marx bases his thought.

It’s well understood by the actual Left that until we’re all free, men and women, etc, then none of us are free, and even a cursory glance at the history of people’s revolutions reveals that without the united effort of women and men, they’ll both languish in bondage. One half of the proletariat trying to get a leg up on the other isn’t just nonsensical, it’s counter revolutionary, detrimental to the well being of both.

The rest of her rubbish-bin of an article is just more smears and ignorance (to be charitable, rather than to assume she’s knowingly lying).

David Satter’s brain rot was ladled out during November of last year, the centennial of the Russian revolution, and he plays the same old tired tunes, inflating the supposed atrocities of “Communism.” That’s always the way, isn’t it? Anyone that dies in a “Communist” country is a victim of Communism, but the swollen mountain of stinking corpses that are still being piled up in the name of Capitalism, well, sorry! that just don’t count.

From the megamind himself:

Although the Bolsheviks called for the abolition of private property, their real goal was spiritual: to translate Marxist-Leninist ideology into reality. For the first time, a state was created that was based explicitly on atheism and claimed infallibility. This was totally incompatible with Western civilization, which presumes the existence of a higher power over and above society and the state.

Another brainlet misrepresentation. Marxism is a materialist philosophy. It’s concerned with the objective and the real. There was nothing “spiritual” about the Bolshevik’s desire to abolish Tsarism, educate the peasants, feed them, house them, clothe them, and modernize the country. I fully doubt that Lenin et al made claims of “infallibility,” and as usual this dipshit completely ignores the reactionary, pro-Tsarist character of the Orthodox church and its role in supporting the aristocracy at the expense of the common people. To say that an “atheist state” is incompatible with Western civilization is utterly idiotic. What is he a “senior fellow” of, exactly? Poopy?

The Bolshevik coup had two consequences. In countries where communism came to hold sway, it hollowed out society’s moral core, degrading the individual and turning him into a cog in the machinery of the state. Communists committed murder on such a scale as to all but eliminate the value of life and to destroy the individual conscience in survivors.

This is a bald faced lie. David Satter is either embarrassingly incompetent as a historian, or he’s an out-and-out liar. He blithely ignores that, previous to the Bolsheviks, the Tsar had no compunction about executing political dissidents, siccing his Cossacks on unarmed civilians, sending ordinary Russians to die by the thousands in wars his country could ill afford, much less equipped to fight, and a devoted proponent of autocracy.

There is no one or two ways about it: the Great War was a Capitalist war, fought for access to markets and resources. There was no noble aim, just destruction and mayhem to secure the fortunes of the wealthy. By the war’s end, Russia alone would lose more than four-million of its people. In total, nearly 25 million people would end up victims of a conflict that resulted ultimately only in ruin and misery for all involved. Pricks like Haig and Ludendorff would “lead” their armies from comfortable, opulent settings, ordering men to march into machine gun fire by the tens-and-hundreds-of-thousands. Even more would die in World War II, approximately 85 million people--110 million people in all, dead in ten years of warfare, and that isn’t even counting all the other conflicts and deaths resulting from the normal operation of Capitalism. Even if the “100 million killed by Communism” was true, it would be absolutely dwarfed by the casualties incurred by Capitalism.

But that’s a stupid game that I don’t like to play, reducing human deaths to some sort of barometer of “rightness.” It ignores the historical context of these events and smacks of bourgeois moralism masquerading as concern for humanity. More than that, it’s an insipid tu quoque parroted by idiots to convince other idiots.

But the Bolsheviks’ influence was not limited to these countries. In the West, communism inverted society’s understanding of the source of its values, creating political confusion that persists to this day.

I don’t know what this brainlet is trying to say by this. Communism is completely in line with Western values of fairness and democracy. The United States was one of the most militant countries in the world at the time, and for good reason. It was the Communists that won workers the 8-hour work day, sick leave, overtime pay, and so on and so on. The implication here is that this “political confusion” is the result of the plebeians standing up to their social betters. It’s clear that by David Satter’s idea of “Western Values,” he means social domination by an aristocracy of blood or wealth. Ah, yes, but it was the Bolsheviks and their mad desire for social equality that undermined human value.