#critique de livre

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

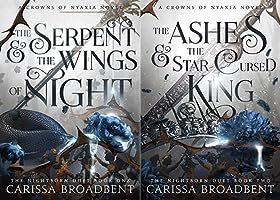

Book Review : The Serpent & The Wings of Night - Carissa Broadbent

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS I'VE READ IN A WHILE

Soul-Crushing. Mind-Blowing. Heart-Breaking. Gut-Wrenching.

I could go on for a while. This was Sarah J Maas meets The Hunger Games in a dark vampire world. But better than all that. It had everything. Also the MC is like 23 so it was perfect for me : not too teenage but not quite yet adult either. Exactly what I look for in books right now.

The vibes ? Awesome. If you're slightly tired of vampire stories and romances, this one won't disappoint. It's dark, in a desert-like world, it has magic and awful gods, murder everywhere. Romance is hella present, but it's not the whole plot.

Because the plot has deadly trials, intricate political themes, unlearning what you've been taught in your childhood, injustice, and so much more. It's finely woven, so much so that you only understand the whole puzzle by the last pages.

And as for the romance... wow. Talk about fucking slow-burn and tension building. The chemistry between these two is unbelievable. ALSO there's a healthy yet complicated father-daughter bond that's just... <3

And the ending, well... it broke my soul into a million tiny pieces, and still left me craving for more. You know the kind of book where you put it down feeling like your chest has been ripped out, and you're both glad and sad about it ? Like how can you go back to living your life after that ? That's this kind of book. I can't wait to read the next one, but i also dread it for my poor little heart.

Well done, Carissa, well done.

What about you ? Have you read this book ? (please i need someone to yell with me about it)

#review#book review#critique littéraire#critique de livre#writing#reading#mine#writeblr#fantasy#na#the serpent and the wings of night#tsatwon#romantasy

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thieves' Gambit T1 de Kayvion Lewis

Ross Quest, voleuse de 16 ans, doit gagner un concours pour sauver sa mère kidnappée. Le récit est captivant, avec une dynamique authentique. Note: ★★★★

#compétition#Critique de livre#Défis mortels#Fiction adolescente#Héros solitaire#Histoire d’aventure#Histoire de survie#Kayvion Lewis#Littérature YA#Livre audio#Livre pour jeunes adultes#Lizzie#Nancy Philippot#Protagoniste féminine#Récit d’action#Relations amicales#Roman de compétition#Roman jeunesse#Suspense#Thieves&039; Gambit#Thriller#Voleurs

0 notes

Text

svetla et helea

Svetla et Helea surplombent les lacs du royaume des Mille Eaux - #midjourney #fotor

www.leseptiemepeuple.fr

#fantasy#livre audio#roman audio#dark fantasy#book blog#fantasy books#roman fantasy#livres et lecture#critique de livre#midjourney#fotor#dark-fantasy#le septième peuple#audiobooks#audiobook#livreaddict#livre

0 notes

Text

Is it not like the basics ? To read a book/watch a movie to form an opinion on it ? Why did you criticize a book or a movie without interacting with it ? It is not elitist, how can you have an opinion on a text you don't know !?

sorry to be part of the elitist intelligentsia but i do think you have to read the text you have an opinion on if you expect your opinion to be taken seriously

#it is the basic#lire un livre avant de critiquer ?#c'est la base#it is NOT elitist#just logic#seriously#read or watch before criticising

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

Olivier Adam - Il ne se passe

Coucou les amis, Présentation du premier polar d'Olivier Adam dont le titre peut surprendre Il ne passe jamais rien ici. Un excellent roman noir !

Jamais rien ici Comme d’habitude, Olivier Adam s’inspire d’un artiste pour lui dédier ce roman choral, présenté sous forme d’une enquête parfaitement réussie. L’épigraphe est un hommage à l’artiste Jean-Louis Murat, trop rapidement disparu. Dans un petit village, près du lac d’Annecy, Olivier Adam y implante son nouveau roman dont le titre peut surprendre : “Il ne se passe jamais rien…

View On WordPress

#Amour#Billet littéraire#Bric à brac de culture#Chronique littéraire#Chronique livre#Chroniques littéraires#Critique#Enquête#enquête policière#Féminicide#Lac#Littérature contemporaine#littérature française#Littérature francaise#Litterature contemporaine#montagnes#Polar#Relation#Relation mère-fils#Relation père-fils#roman#Roman social#romans policiers#social#Thriller#Thriller noir#Village

0 notes

Text

Ep.71 🍽️ François Simon "La cuisine, c'est le don. On a envie qu'il y ait du sentiment."

François Simon, le critique gastronomique le plus célèbre de France. J’ai découvert tardivement sa voix envoûtante, ses mots, son œuvre, grâce à Instagram où il publie chaque jour ses découvertes. Il était temps de parler des lieux où on donne rendez-vous pour un 1er date : un café, qui peut mener à un restaurant et qui sait ensuite ? Quel endroit choisir ? Et quelle place à l’intérieur du lieu ?…

View On WordPress

#amour#Anton Ego#bruit#café#célibat#célibataire#chef#comptoir#couple#critique gastronomique#cuisine#cuisine de maman#dating#féminisme#François Simon#livres#misophonie#partage#patriarcat#petit déjeuner#plaisir simple#podcast#Ratatouille#recette#rencontres#restaurant#sexfriends#sociologie#terrasse#traditions culinaires

0 notes

Text

Voici l'histoire du dernier des hommes qui parlait la langue des serpents, de sa sœur qui tomba amoureuse d’un ours, de sa mère qui rôtissait compulsivement des élans, de son grand-père qui guerroyait sans jambes, d’une paysanne qui rêvait d’un loup-garou, d’un vieil homme qui chassait les vents, d’une salamandre qui volait dans les airs, d’australopithèques qui élevaient des poux géants, d’un poisson titanesque las de ce monde et de chevaliers teutons épouvantés par tout ce qui précède... Peuplé de personnages étonnants, empreint de réalisme magique et d’un souffle inspiré des sagas scandinaves, un roman à l’humour et à l’imagination délirants. (Booknode)

Folklore, contes et croyances s'entremêlent et, parfois, s'entrechoquent dans ce roman hors du commun. Dans cette Estonie réinventée, Leemet notre protagoniste, se trouve à la frontière entre tradition et modernité. Les hommes quittent un à un la forêt, se convertissent au christianisme et oublient la langue des serpents. Entre ceux qui se cramponnent à des coutumes insensées et ceux qui se précipitent aveuglément dans un nouveau mode de vie, Leemet peine à trouver sa place.

Je découvrais ici l'imaginaire de Kivirähk. Je l'avoue, je craignais un peu d'y trouver un monde qui me serait inaccessible, moi qui en sais bien peu sur le folklore scandinave. Au final, je m'inquiétais pour rien. L'auteur nous invite avec plaisir dans son univers merveilleux, accessible à tous et terriblement captivant. Il s'interroge sur le progrès et les valeurs ancestrales sans prendre parti. Au contraire, il démontre les bons et mauvais côtés de chacun, laissant à son protagoniste - et à ses lecteurs - le soin de faire le tri.

J'ai adoré découvrir ce monde fantastique et ces personnages hauts en couleurs. C'était le premier Kivirähk que je lisais, mais certainement pas le dernier.

Note finale : 5/5

instagram

#j'ai lu#livres#critique#l'homme qui savait la langue des serpents#Andrus Kivirähk#littérature estonienne#fantastique#lecture de septembre#Instagram

0 notes

Text

« Nous sommes comme des livres. La plupart des gens ne voient que notre couverture, une minorité ne lit que l'introduction, beaucoup de gens croient les critiques. Peu connaissent notre contenu. »

~ Émile Zola -

453 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ter T.a não te dá passe livre pra criticar o corpo alheio...

Pelo contrário, nós pessoas com T.a sabemos mais do que ninguém como é a sensação horrível de odiar o próprio corpo e de se sentir mal só por se olhar no espelho... Então não faz sentido fazer alguém sentir o mesmo ódio e a mesma sensação que nós sentimos e que, sabemos o quão ruim é.

Se quer criticar algum corpo, critique o seu, quem sabe isso te ajude a focar na sua meta e a deixar o corpo alheio em paz.

obs: isso não é válido pra pessoas que criticaram seu corpo!! se alguém falou sobre seu peso, você tem sim direito de falar sobre o dela de volta.

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review : The Cruel Prince - Holly Black

You're only reading this series now ?!

Well... yes. I'm late. I know. Lmao. Better late than never.

Anyway, I heard a loooot about this series before reading it. Praise comparing it to Leigh Bardugo, Cassandra Clare and Sarah J Maas -> aka, all my favorite authors. So I was very confident picking up this book. I expected it to become my new favorite, my latest obsession.

It was not the case. Hear me out, I did like it. But not as much as I expected to. Allow me to explain. The novel is divided in two parts, Book 1 and Book 2. Book 1 lasts for more than half the actual thing. It's all about lore, worldbuilding, getting to know the characters etc. And I just... couldn't get lost in this world. I suppose little folk and faeries aren't necessarily for me. It was nice-ish, but just too much description and lore at once for my taste.

And the whole plot is basically low-stakes teenage drama and I just couldn't find myself caring about what would happen next. You can definitely tell there's underlying politics and scheming about to come. You can feel it has a lot of potential but... it's just not fully developed. So I was a bit disappointed.

BUT THEN.

You get to the end of Book 1. AND. HERE. IT. IS. There's politics, there's intrigue, there's plot, drama and tension all at once, and it finally starts to feel like the stakes are higher than ever and we're about to get real action and find out what this OC is capable of.

And Book 2 is just awesome. I really liked it and read it super quickly. I do want to read the next book and I did enjoy this one, I just wished the first part was shorter and the second longer.

What about you ? Have you read this series ?

#review#book review#critique littéraire#critique de livre#writing#reading#mine#writeblr#ya#fantasy#cruel prince#holly black

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

les reines de la nuit

#fantasy#livre audio#roman audio#roman fantasy#dark fantasy#book blog#fantasy books#dark-fantasy#astres#aipicture#ai generated#ai image#midjourney#livreaddict#critique de livre#livre#books & libraries#listen#literature#livres et lecture#liveblogging

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ser livre é algo que não tem preço...Sentimos em nossa alma a doçura e a delicadeza da sensação de paz de alegria, e a felicidade completa...Sem medo de críticas ou questionamentos...Somos donos de nós mesmos...E A felicidade voa para as palmas das mãos, quando estamos prontos para aceitá-la...

Ser libre no tiene precio... Sentimos en nuestra alma la dulzura y la delicadeza del sentimiento de paz, de alegría y felicidad completa... Sin miedo a la crítica ni al cuestionamiento... Somos dueños de nosotros mismos... Y la felicidad vuela a las palmas de nuestras manos, cuando estamos listos para aceptarla...

Essere liberi non ha prezzo... Sentiamo nella nostra anima la dolcezza e la delicatezza del sentimento di pace, di gioia e di felicità completa... Senza timore di critiche o domande... Siamo padroni di noi stessi... E la felicità vola nei palmi delle nostre mani, quando siamo pronti ad accettarla...

Être libre, ça n’a pas de prix... Nous ressentons dans notre âme la douceur et la délicatesse du sentiment de paix, de joie et de bonheur complet... Sans crainte de la critique ou de la remise en question... Nous sommes maîtres de nous-mêmes... Et le bonheur s’envole dans la paume de nos mains, quand nous sommes prêts à l’accepter...

Being free is priceless... We feel in our soul the sweetness and delicacy of the feeling of peace, of joy, and complete happiness... Without fear of criticism or questioning... We are masters of ourselves... And happiness flies into the palms of our hands, when we are ready to accept it...

Frei zu sein ist unbezahlbar... Wir spüren in unserer Seele die Süße und Zartheit des Gefühls des Friedens, der Freude und des vollkommenen Glücks... Ohne Angst vor Kritik oder Infragestellung... Wir sind Meister unserer selbst... Und das Glück fliegt uns in die Hände, wenn wir bereit sind, es anzunehmen...

Özgür olmak paha biçilemez... Ruhumuzda huzur, neşe ve tam mutluluk duygusunun tatlılığını ve inceliğini hissediyoruz... Eleştirilmekten ve sorgulanmaktan korkmadan... Biz kendimizin efendisiyiz... Ve mutluluk, kabul etmeye hazır olduğumuzda avuçlarımızın içine uçar ...

Fonte: 1Vidapoeticando 🌺🍃 🦋

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je veux pas critiquer booktok pour critiquer booktok mais je crois que j'ai compris pourquoi certains livres très populaires déçoivent parfois quand on les lit enfin. Je regardais une booktokeuse qui parlait des livres qu'elle aimait et qu'elle n'aimait pas et elle en parlait de manière très émotionnelle : "ce livre va vous faire pleurer", "ça me faisait frissonner" et c'est pas forcément une mauvaise chose ! Je dis souvent à mes élèves de partir de ce qu'ils ressentent pour analyser un texte. Mais après il faut aller plus loin : quand elle parle du style d'un auteur qu'elle n'aime pas "vous verrez en lisant, c'est particulier" en quoi ? C'est froid ? Au contraire, c'est très riche, y a beaucoup d'adjectifs ? En quoi c'est triste, en quoi c'est beau ?

Le problème, c'est que je peux vous montrer trois livres radicalement différents en vous promettant qu'ils m'ont fait pleurer et ce sera sans doute vrai, mais ça ne suffit pas : c'est le détail, la forme, qui va porter le livre, le distinguer des autres. Si elle avait dit : "J'ai beaucoup aimé ce livre car sa structure narrative atypique fait qu'on est porté tout au long de l'histoire. Le style froid de l'auteur, assez neutre, permet de vraiment mettre en relief la dureté de ce monde" etc, on saurait à quoi s'attendre et en lisant ensuite le livre, même si on aime quand même pas, on n'aurait pas l'impression d'avoir été trompé sur la marchandise. Je pourrais me dire "en effet, la structure narrative est atypique mais personnellement, je la trouve confuse" et ainsi de suite. Alors que juste dire "ça m'a fait pleurer donc c'est bien", on ne peut pas cerner l'intérêt du bouquin.

Vous pouvez pleurer en lisant Twilight et en lisant Proust, et c'est légitime dans les deux cas, mais les techniques littéraires ne seront pas les mêmes.

#je sais pas si c'est clair#je veux pas clasher sur booktok mais c'est plus un conseil méfiez-vous des avis sans éléments concrets#je dis ça parce que je me suis déjà fait avoir lol#livre#booktok

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last break between Fouché and Babeuf

Once again, feel free to correct me if I am saying anything wrong, I am not infallible. The flow and structure leave much to be desired due to my significant fatigue, so I would fully understand any critique. It's just that with my computer acting up and no USB key at the moment, I’ll publish it to avoid losing important information.

I have already shown some excerpts from historians or speeches about the rupture between Fouché and Babeuf here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/767448240197140480/excerpts-from-letters-and-chapters-of-historians?source=share

Historical context: Initially allies, as is well known in history (to the point that Fouché may have funded Gracchus Babeuf’s newspaper), they gradually drift apart. An interesting fact: they were almost the same age, and it is possible they knew each other before the Revolution in Arras, when Gracchus was a feudalist, though this is uncertain. They also had a common experience: losing several of their brothers and sisters during childhood (plus both are very caring husbands to their wives, adoring fathers to their offspring and have been devastated by the loss of some of their children ). However, Jean-Marc Schiappa explains that, while the possibility they met before the Revolution is conceivable, there are reservations about this idea. Why, then, did Babeuf not contact him in 1793?

Shortly before this break, Gracchus Babeuf had already realized Fouché’s true nature, not to mention the reproaches he had against him, especially for what he had done to his family, accusing him of reducing them to begging. Waresquiel claims they were close before the break, due to the use of the informal "tu," which suggests familiarity. Jean-Marc Schiappa rejects this hypothesis, noting that revolutionaries used "tu" as a sign of republican equality. On the other hand, Babeuf had thought about entrusting Fouché with the guardianship of his children in case of misfortune. Jean-Marc Schiappa quotes an anonymous historian who explained that Fouché supported Gracchus Babeuf’s children while he was in prison. However, Schiappa qualifies this by pointing out that Babeuf’s children (probably Émile and Camille) went to see him, and he only gave them 10 livres, saying he was not wealthy. When Émile wrote to his father, Gracchus, saying that it was not the generosity of his friends that allowed them to survive, it seems he was referring to Fouché, according to Schiappa. This must have been the first significant grievance Gracchus had against Fouché (though perhaps their initial break had occurred earlier).

Gracchus Babeuf’s return in 1795: Babeuf was released from prison on the 26th of Vendémiaire Year IV (October 18, 1795) thanks to an amnesty on 4 Brumaire. During his time in prison, he surrounded himself with or formed alliances with Darthé, Buonarroti, Antonelle, Charles Germain, Bodson, and many others. It is possible that the widow of Lebon was part of this group, as she mentioned during their time in prison that “Here, all the friends are in constant meetings with Babeuf.” Gracchus, who was in contact with Jullien de Paris, left the capital for some time, though he returned. Topino-Lebrun had offered him a position in Switzerland months earlier. Gracchus found his children and wife in a dreadful state, the result of Boissy d’Anglas’ laws and others. He had lost his daughter, who died of malnutrition, which deeply saddened him when he learned of her death in prison.

Gracchus continued his meetings and his journal. But here’s an excerpt from Jean-Marc Schiappa on how Fouché tried to corrupt Babeuf (possibly under the orders or with the support of Barras):

“On 14 Brumaire, shortly after the meeting at Bouin’s, Babeuf was received in the presence of Antonelle, a democratic journalist, and former member of the Revolutionary Tribunal, by Fouché at the latter’s request. Fouché had read the manuscript of the first issue of Tribun du Peuple. How? More would need to be known about the discussions at Bouin’s, given the later trajectories of Féru and Rousillon, who later became close to Barras, and their possible connections with Fouché. For two hours, Fouché insisted that Babeuf soften his text and remove certain passages. Acting probably as an emissary of Barras, a member of the Directory and considered the most republican of the Directors, he offered to obtain ‘six thousand subscriptions from the Directory.’ This was nothing other than the purchase of the newspaper and the journalist.” Apparently, Fouché was surprised by Babeuf’s refusal. A few days later, Babeuf publicly denounced Fouché in his newspaper article, detailing the deal Fouché had offered to him and to the tribune. Later, Gracchus would claim that he was innocent of the venality some offered him, as he lived in poverty and refused to be corrupted by Fouché (or even Barras). Gracchus no longer wanted anything to do with Fouché and reproached him for his compromises.

Waresquiel agrees with Schiappa on Fouché’s attempt to corrupt Gracchus Babeuf.

First question: So, when did the break begin? I think it’s easy to say that it started in prison in 1795. Indeed, we can say that on April 8, 1795, he wrote to Fouché as follows: “The catastrophe of 12 Germinal makes great changes likely. This does not at all mean that I renounce or quit the cause. The ideas that occupy me, along with the conclusion I want to establish in this letter, will lead me, my friend, to discuss with you the great battle we have just lost... but should we let ourselves be defeated? No. It is in great dangers that genius and courage unfold.” However, on August 9, 1795, Charles Germain (one of the most important conspirators) wrote to Babeuf about Fouché: “Well! Here’s Fouché arrested. Good! Good! Morbleu! That’s how we learn to live with that scoundrel. What an example for traitors!” Moreover, Fouché was apparently disliked by several important conspirators (we don’t even need to explain why for the Duplay family, Charles Germain, Babeuf later). Let’s not forget that there were tensions with some like Amar and Vadier, who were reproached by their babouvist “colleagues” for their participation in the 9 Thermidor (even though Amar and Vadier were ambiguous, though not traitors in this conspiracy babouvist), even though some important, trusted babouvists like Bodson were staunchly anti-Robespierre (Bodson reproached Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety for the death of his friend Chaumette and Hébert). What I mean is that Babeuf was already surrounded by people who resented Fouché, and soon he would have his own grievances against him.

What was Fouché's responsibility in the repression suffered by Gracchus Babeuf afterward?

After all, Fouché is known for showing no mercy to those who become his deepest enemies. And Babeuf swore, through his words of rupture and speeches, to always stand against him (and people like him) for the good of the revolution. Babeuf also brought founded accusations against him, such as his dubious dealings. Waresquiel says that the first service Fouché rendered to Barras was regarding the Babeuf faction. Waresquiel also mentions that Fouché did not directly participate in Babeuf's final arrest, which would lead to his death, but that he did inform Barras about the conspirators. Both Fouché and Barras mention this in their memoirs (which are highly debatable). Nevertheless, Buonarroti, who is much more reliable, is sure of Barras’s involvement in the repression of the Babouvists, as is Tissot, who agrees with Buonarroti on this hypothesis (particularly regarding the repression at the Grenelle camp). Jean-Marc Schiappa himself does not exclude it, even though Claude Mazauric claims that Barras had reservations about arresting the Babouvists, and that Lazare Carnot was the driving force behind the repression of the Babouvists, as seen in the posts here: link 1, link 2, link 3.

(Do not mistake any comparison between Carnot and Barras, by the way; even though they may share some responsibility for the Grenelle camp and the crushing of the Babouvists. The former, known as the Organizer of Victory, carried out an atrocious and unforgivable repression in the Equal's conspiracy, but with the sincere belief that he was saving the Republic, whereas the latter, Barras, saw the revolution primarily as a means to wealth and lived well within corruption. Their mindsets at the time of the Babouvist repression were thus entirely different. In fact, their mindsets were completely different on most subjects.)

Here is what Fouché would later say (he, who would have the Rue du Bac club, where neo-Jacobins gathered, shut down two years later) about the last nostalgic supporters of Babeuf and equality, according to Waresquiel:

"Deep down, Fouché likes the Jacobins no more than they like him. This is what he told Jacques de Norvins, the future director of the police of the Roman States, when he was once discussing with him his former friends from the Terror period, the last nostalgic supporters of Babeuf and equality, who certainly do not want to change: 'They're still stuck on the Incorruptible Robespierre. Well, I hunt them down to stop them from shooting themselves. I give them bread, I mock them, and within six months, they’ll come to besiege me for positions.' 'And will you give them some?' asked Norvins. - 'Why not?' replied Fouché."

The ex-conventionnel is almost always the man for the situation because he knows it better than anyone else. He remains unshaken in the face of threats. He’s seen worse. One last day in August, one of his former acquaintances from the Jacobin club, sensing the tide turning, came to insult him right in the courtyard of his ministry, on behalf of his "brothers and friends." "We’ll parade your head through the streets of Paris," he threw at him, and Fouché, colder and more mocking than ever, replied: "Let me look at myself in a mirror, so I can get an idea of the effect my head will have when you place it on the point of a pike."

It’s clear that Fouché had already broken with the Jacobins.

Although, Fouché lied in his statement: "I give them bread, I mock them, and within six months, they’ll come to besiege me for positions." Has he forgotten that just a few years ago, he made this offer to Gracchus, who not only refused but also openly denounced him (and I believe there were others who did the same as Gracchus)? I don’t think so. After all, Fouché is a master of deceit. On the other hand, Waresquiel, with convincing evidence, claims that four years later, Fouché saved Vadier from deportation, despite Vadier having some responsibility in the Babouvist conspiracy, although ambiguous (but once again, for everything he was blamed for, Vadier, a major political ambiguous figure who has a lot to reproach himself for , was not a traitor in the Babouvist conspiracy, unlike Grisel). In his memoirs, Fouché says:

"It was during the early troubles of the Directory, when it was facing the Babœuf faction. I communicated my ideas to Barras; he invited me to write them down in a report, which I submitted to him. The position of the Directory was politically analyzed, and its dangers listed precisely. I characterized the Babœuf faction, which had revealed itself to me, and showed that, while dreaming of the agrarian law, they secretly aimed to seize the Directory and power by surprise, which would have brought us back to demagoguery through terror and blood. My report made an impression, and the problem was cut off at its root. Barras then offered me a secondary position, which I refused, not wanting to accept posts except by the main route; he assured me he lacked enough influence to elevate me, his efforts to overcome his colleagues’ prejudice against me having failed. The coldness between us grew, and everything was postponed."

Although it’s ironic that Fouché speaks of demagoguery through terror and blood, because while Babeuf condemned certain excesses of the representatives on mission like Carrier, Fouché himself is known for his cannon executions in Lyon.

However, while it is difficult to assess the extent of Fouché’s responsibility in the repression of the Babouvists, it is undeniable when it comes to what he later did to their widow during the repression of the Jacobins, as well as to Gracchus's son, Émile Babeuf, later during the first Malet conspiracy a few years later.

I have already discussed the three theories that led Fouché to target Marie-Anne Babeuf (arrested once when he was Minister of Police, shortly after the Saint-Nicaise street attack) twice and her son once (during the Malet conspiracy) here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/771601754872856576/the-mysteries-of-marie-anne-babeuf-wife-of?source=share.

I recently learned two important pieces of information. The first, unsurprisingly, concerns Félix Le Peletier, who opposed Bonaparte as soon as he became First Consul. In 1800, Félix, accompanied by his longtime friend Antonelle, clashed with Bonaparte's justice for printing pamphlets against him and participating in clandestine movements. This forced them to flee Paris that same year. Later, Félix Le Peletier was saved from deportation with the help of his friend Saint-Jean d’Angely.

Now, Félix Le Peletier was also the protector of the Babeuf family, and Marie-Anne Babeuf, in particular, had a great talent for political clandestinity. Fouché must have met her at this time, as she was in Paris and played an important role in her husband Gracchus's political life. She always supported him loyally, demonstrating great cunning. In addition to participating in her husband's printing activities, she was a kind of political right-hand woman to him. During her arrest, the police held her for three weeks trying to figure out where her husband was hiding, but she refused to cooperate, to the point that the police became desperate.

It is also known that Gracchus Babeuf sent his letters secretly via his close associates, including Marie-Anne and their son Emile. In his correspondence, notably in a letter addressed to Fouché on April 8, 1795, he mentioned that his messages were sent securely, often through his wife and his son Émile, who handled the delivery while evading the police. While there is no direct evidence, given Marie-Anne's determined character in adversity, it is possible that she continued her clandestine activities, as she was close to opposition figures. However, there is no certainty about this, and her life remains a mystery. Her arrest in 1801 therefore seems inevitable.

The second piece of information particularly caught my attention. According to historian Pierre Serna, there is evidence from 1808 showing that Émile Babeuf had contact with Antonelle through a document written in his hand. This contact might also be linked to the republican opposition movement against Bonaparte, namely the Philadelphes (a group of neo-Jacobins opposed to Bonaparte), as well as with Buonarroti. Although Buonarroti had limited trust in Émile, with whom he had worked closely when Émile’s father Gracchus was alive, this information suggests intriguing connections. In 1807, an arrest warrant was issued for Émile Babeuf, which seemed justified, although the only evidence against him was a document in his own handwriting, mentioning Antonelle's name and visits to Buonarroti. What is surprising is that the charges were quickly dropped. The police seemed to be unaware that he was abroad for work during the Malet Conspiracy, and yet they seized his mother’s papers, interrogated her (though harshly), and returned her belongings after two days. This remains rather strange.

But what is truly frightening is knowing that Fouché knew Émile as a child, to the point that Gracchus may have considered entrusting his son to him. Years later, Fouché sought to have him arrested, even though he had known him when Émile was a child.

So, once again, here are the three theories for which Fouché targeted Marie-Anne Babeuf and Émile, updated with the new knowledge I’ve learned recently:

Theory 1: Opportunistically, Fouché wanted to show Bonaparte that he had no mercy for the Jacobins (after all, Fouché was in a delicate position), especially after the Saint-Nicaise street attack, which I briefly discussed here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/756533326215528448/the-jacobins-executed-by-bonaparte?source=share and here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/767626191447392256/the-journey-of-the-forgotten-french-revolutionary?source=share . Bonaparte had not forgotten the Babouvistes, so widow Babeuf was a logical target. But why attack her and her son again in 1808, even though this episode of the Malet Conspiracy exposes Fouché’s limitations as Minister of Police, according to Jean Tulard? I don’t know. I think after that, it was because Émile had contacted Buonarroti, so maybe for verification. Especially since Émile had a note mentioning Antonelle. Honestly, I think the first hypothesis is the most plausible.

Theory 2: Gracchus Babeuf and Fouché worked together at one point (more precisely, Fouché manipulated Gracchus before Gracchus realized his true nature and showed him the door, as you can see here). It is very likely, if not almost certain, that Fouché met Gracchus’s wife and saw her political talents, her activism, her combative nature in the underground, and her ability to escape the police, as she was always by Gracchus’s side. As a close ally to her husband, she had been involved in underground activities, and Fouché may have suspected that she continued anti-Napoleonic actions. Furthermore, her associations with neo-Jacobins and opponents like René Vatar and Félix Le Peletier may have fueled Fouché's suspicions. Perhaps these suspicions were justified, given the strong character of widow Babeuf. In 1808, he may have wanted to verify this. Fouché was simply acting as a "good" Minister of Police to fight against the Empire’s opponents, especially since his son Émile was in contact with Buonarroti and Antonelle (and probably with her too, even if she stayed in Paris).

Theory 3: The third theory is the one I believe the least, but after discussions with friends, I’ve decided to include it. We know that Fouché liked to keep all documents related to him, including sensitive documents about others, and he liked to destroy traces of himself (including information about his own mother, for which there is no record). In fact, in his later years, he burned papers containing important correspondence, notably with Condorcet, Robespierre, Collot d'Herbois, and others. We know that Gracchus Babeuf had to produce documents about him, corresponded with him, especially when Gracchus considered him an ally but also had messages mentioning him. It is possible that Fouché sought to recover these documents, either directly or indirectly. We also know that in Gracchus’s last letter before his execution, he left his defense papers to his wife, advising they be passed on to their friends. Here is an excerpt from this letter: “Lebois announced he would print our defenses separately. We must give my defense as much publicity as possible. I recommend to my wife, my dear friend, that she not give any copy of my defense to Baudouin, to Lebois, or to others, without keeping another exact copy with her to ensure that this defense is never lost,” as you can see here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765954409563897856/last-letter-of-babeuf-before-his-execution?source=share.

What’s the connection? Gracchus Babeuf may have entrusted his wife with other important papers, and Joseph Fouché might have wanted to recover them, either indirectly, or he wanted to verify their contents to see if they concerned him directly. So, what could he do if Marie-Anne Babeuf surely didn’t want anything to do with him anymore? He could commit burglary (Fouché clearly demonstrated that he often acted outside the law in ways that are difficult to understand. I am currently examining the Clément de Ris case more closely through the papers of Clément de Ris to see if the hypothesis of historian Alain Decaux aligns with that of Waresquiel, which highlights the extent to which Fouché could be unscrupulous at times as you all know which is an understatement). However, Marie-Anne Babeuf would have quickly deduced who it was or would have her suspicions. It is important to note that the Babeufs had important links with François Réal, who had a significant role in Bonaparte’s government (François Réal, along with Admiral Truguet, was one of the few to openly protest against Bonaparte when Napoleon ordered the repression of the Jacobins in 1801 during a council). So, she might have informed Réal, who would tell Bonaparte, which would have been problematic. So burglary is out of the question. On the other hand, when someone is arrested or interrogated, their house can be searched legally. This is partly why he included Marie-Anne Babeuf’s name in the list of Jacobins to be arrested in 1801—to thoroughly search her home and the homes of her friends to try to recover her papers. Perhaps Fouché was not satisfied with what he found in 1801 and took the opportunity to try again and search her home in 1808. Proof is that her papers were confiscated, even though they were returned to her two days later. So, Fouché targeted Marie-Anne Babeuf to verify that she didn’t have any compromising documents about him, or to try to get his hands on any papers Gracchus might have left, which could be important for him.

On the other hand, my friends are the ones who, before I discovered the proposal Fouché made to Gracchus, theorized that if Babeuf had gone along with the tide, like Fouché, and hadn’t denounced, maybe Fouché would have granted him a pension or at least a good sum of money. And they were right, so this third theory could work, even though, again, it’s the least plausible one I think.

P.S.: Interesting fact, according to Jean Dautry, Fouché refused to arrest Antonelle during the Malet Conspiracy, even though his opposition to Bonaparte was much better known. Yet, the two men had little in common. Why? It’s important to specify that Antonelle knew Fouché from when Gracchus was alive, as he witnessed the attempt at corruption that Fouché tried on Gracchus. Did Antonelle have something compromising on Fouché? I don’t think so, otherwise, he would have made sure that these proofs came to light, or he would have used them to benefit the freedom of many of his comrades, knowing this noble revolutionary. Or, as Jean Tulard showed, this Malet Conspiracy of 1808 revealed the limits of Fouché’s effectiveness as Minister of Police. He would have had every interest in making it seem that this conspiracy wasn’t dangerous, and as a result, Antonelle���s name, which was well-known, was erased.

On the other hand, why did Antonelle (Gracchus's ally) attend the final meeting that would lead to the break between Gracchus and Fouché? Because frankly, if Barras hoped to corrupt Antonelle, that's really foolish. I mean, Gracchus was in a state of great poverty, had just lost his daughter to malnutrition, and his wife and sons were in horrible health. Even though he refused to be corrupted by Barras, I can understand why, seeing his advanced state of misery, Barras hoped he would accept his offer. But Antonelle? I mean, yes, he had been loyal to the revolution his whole life but he's immensely wealthy ( Antonelle's wealth comes honestly), so offering him more money to corrupt him would be pointless.

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#joseph fouché#babeuf#lazare carnot#Barras#Antonelle#history#france

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

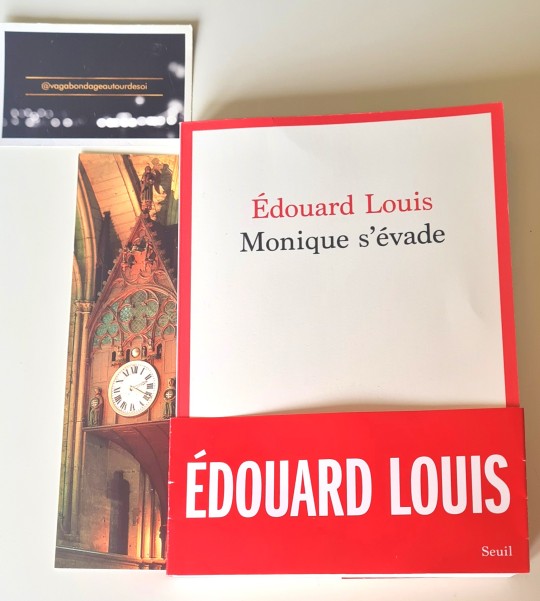

Édouard Louis - Monique s'évade

Présentation du récit de Édouard Louis, Monique s'évade, une commande de sa mère pour rendre compte de sa libération et son évasion.

Avec ce leitmotiv “La honte est une mémoire”, Édouard Louis relève tous ses petits souvenirs de rendez-vous manqués, ces moments de gêne, de ses paroles prononcées, vite oubliées, qui décriait le quotidien de sa mère, même séparée de son père. Elle avait cru encore une fois qu’un homme pouvait la protéger ! Mais, un soir, elle appelle son fils… “Trois maris, trois poivrots”. Et au troisième,…

View On WordPress

#Billet littéraire#Chronique littéraire#Chronique livre#Chroniques littéraires#Condition de femmes#Critique sociale#Evasion#Famille#Famille violence#Femme#femmes#Liberté#Littérature francaise#Litterature contemporaine#Maltraitance#Récit#Relation mère-fils#SDF Femmes#violence#Violence à l&039;égard des femmes#Violence envers les femmes#Violences#Violences conjugales#Violences domestiques#Violences masculines

0 notes

Text

Le droit d’emmerder Dieu par Richard Malka

« Avocat, c’est un métier d’indigné », répète à l’envi Eric Dupont-Moretti. Son confrère Richard Malka le démontre dans les 93 pages d’une plaidoirie puissante prononcée lors du procès des attentats de Janvier 2015 au cours duquel il défend son client: Charlie Hebdo. Le journal satirique a été créé en 1992 sous la houlette de Philippe Val, Cabu, Wolinski, Gébé et Cavanna sous un nom de société tristement ironique: « société Kalashnikov »! C’est Richard Malka lui-même qui en avait rédigé les statuts…

L’avocat nous livre l’intégralité du texte qu’il avait prévu de prononcer lors du procès, le 4 décembre 2020.

Il ne s’agit pas d’une plaidoirie larmoyante, consacrée à la mémoire des victimes dont il était à l’évidence l’ami. Malka dépasse la tristesse et la révolte, se refuse aux phrases convenues des condoléances, transforme sa plaidoirie en un réquisitoire sans concession contre l’obscurantisme. « Le sens de ces crimes, c’est l’annihilation de l’Autre et de la différence », entame-t’il. Mais ce qu’il recherche, dans sa démonstration implacable, c’est la réponse à la question essentielle: comment en est-on arrivé là?

L’avocat reprend avec minutie la chronologie de l’affaire des caricatures. Il démonte l’engrenage invraisemblable d’une haine minutieusement instillée par des puissances étrangères décidées à éteindre Les Lumières comme la liberté de dire et de penser en Occident.

Il défend le droit à la critique, au pamphlet et à la caricature que tous les tribunaux français ont sans cesse confirmé. On peut rire de la politique comme de la religion, rappelle-t’il.

« Non, l’Islam ne peut pas être la seule religion de notre pays à exiger de ne pas être critiquée », remarque-t’il en soulignant que ce serait alors « sortir l’Islam du pacte républicain ». Pour Richard Malka, la classe politique dans son ensemble, et la plupart des intellectuels se sont beaucoup fourvoyés. Il ne comprend pas les mots d’apaisement lancés ici et là, pour « amadouer » les tenants d’une approche totalitaire de la société. « Il n’y a pas de salut dans la lâcheté », lance-t’il en conclusion.

Renoncer à la liberté d’expression, c’est accepter le « crépuscule des Lumières » tandis que le combat consiste à espérer « qu’elles soient une nouvelle aube ».

Indigné, Malka l’est au point de nous faire adhérer à son point de vue qui se résume ainsi: un éloge de la vie libre et éclairée.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

6 notes

·

View notes