#contemporary spiritual writers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A academic reflection of Dallas Willard's "Renovation of the Heart"

What book would you recommend? “That’s interesting, I’d like to know something about spirituality. Can you recommend something for me to read that would be helpful?” Introduction This essay is framed in the context of Christianity. Spirituality must be viewed from our own lived experience and our weltanschauung[1] and it would be disingenuous to not be authentically Christian and…

View On WordPress

#Augustine Of Hippo#contemporary spiritual writers#Covid-19#Dallas Willard#Dan allender#Exodus 15:22-23#falling from grace#Gustavo Gutierrez#Luke 18:9-14#Mary Margaret Funk#Methodist#Nina A. Toumanova#Proverbs 27:17#psalm 1#Psalm 119#Psalm 143#Psalm 145#Psalm 39#Psalm 42#Psalm 48#Psalm 77#Rebecca St. james#Renovation of the heart#Rev. Dr. Brenda K. Buckwell#Richard Foster#Stormie O’Martian#The Spirit of Disciplines#The way of the pilgrim#Wesleyan#Wesleyan Methodist

0 notes

Text

#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#poets on tumblr#poetry#writeblr#poets corner#spilled ink#spilled words#poetry community#contemporary poet#spiritual poetry#spirituality

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from An Interesting Book— more at AnInterestingBook.com

#spirituality#literature#modern#American#art#contemporary literature#writing#writers#writers of tumblr#meditation#buddhism#philosophy#poetry#zen#moon#melancholia#searching#words#beautiful words#sacred#yoga#wisdom#quotes#good books#good reads#reading

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

free online james baldwin stories, essays, videos, and other resources

**edit

James baldwin online archive with his articles and photo archives.

---NOVELS---

Giovanni's room"When David meets the sensual Giovanni in a bohemian bar, he is swept into a passionate love affair. But his girlfriend's return to Paris destroys everything. Unable to admit to the truth, David pretends the liaison never happened - while Giovanni's life descends into tragedy. This book introduces love's fascinating possibilities and extremities."

Go Tell It On The Mountain"(...)Baldwin's first major work, a semi-autobiographical novel that has established itself as an American classic. With lyrical precision, psychological directness, resonating symbolic power, and a rage that is at once unrelenting and compassionate, Baldwin chronicles a fourteen-year-old boy's discovery of the terms of his identity as the stepson of the minister of a storefront Pentecostal church in Harlem one Saturday in March of 1935. Baldwin's rendering of his protagonist's spiritual, sexual, and moral struggle of self-invention opened new possibilities in the American language and in the way Americans understand themselves."

+bonus: film adaptation on youtube. (if you’re a giancarlo esposito fan, you’ll be delighted to see him in an early preacher role)

Another Country and Going to Meet the Man Another country: "James Baldwin's masterly story of desire, hatred and violence opens with the unforgettable character of Rufus Scott, a scavenging Harlem jazz musician adrift in New York. Self-destructive, bad and brilliant, he draws us into a Bohemian underworld pulsing with heat, music and sex, where desperate and dangerous characters betray, love and test each other to the limit." Going to meet the Man: " collection of eight short stories by American writer James Baldwin. The book, dedicated "for Beauford Delaney", covers many topics related to anti-Black racism in American society, as well as African-American–Jewish relations, childhood, the creative process, criminal justice, drug addiction, family relationships, jazz, lynching, sexuality, and white supremacy."

Just Above My Head"Here, in a monumental saga of love and rage, Baldwin goes back to Harlem, to the church of his groundbreaking novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, to the homosexual passion of Giovanni's Room, and to the political fire that enflames his nonfiction work. Here, too, the story of gospel singer Arthur Hall and his family becomes both a journey into another country of the soul and senses--and a living contemporary history of black struggle in this land."

If Beale Street Could Talk"Told through the eyes of Tish, a nineteen-year-old girl, in love with Fonny, a young sculptor who is the father of her child, Baldwin's story mixes the sweet and the sad. Tish and Fonny have pledged to get married, but Fonny is falsely accused of a terrible crime and imprisoned. Their families set out to clear his name, and as they face an uncertain future, the young lovers experience a kaleidoscope of emotions-affection, despair, and hope. In a love story that evokes the blues, where passion and sadness are inevitably intertwined, Baldwin has created two characters so alive and profoundly realized that they are unforgettably ingrained in the American psyche."

also has a film adaptation by moonlight's barry jenkins

Tell Me How Long the Train's been gone At the height of his theatrical career, the actor Leo Proudhammer is nearly felled by a heart attack. As he hovers between life and death, Baldwin shows the choices that have made him enviably famous and terrifyingly vulnerable. For between Leo's childhood on the streets of Harlem and his arrival into the intoxicating world of the theater lies a wilderness of desire and loss, shame and rage. An adored older brother vanishes into prison. There are love affairs with a white woman and a younger black man, each of whom will make irresistible claims on Leo's loyalty.

---ESSAYS---

Baldwin essay collection. Including most famously: notes of a native son, nobody knows my name, the fire next time, no name in the street, the devil finds work- baldwin on film

--DOCUMENTARIES--

Take this hammer, a tour of san Francisco.

Meeting the man

--DEBATES:--

Debate with Malcolm x, 1963 ( on integration, the nation of islam, and other topics. )

Debate with William Buckley, 1965. ( historic debate in america. )

Heavily moderated debate with Malcolm x, Charles Eric Lincoln, and Samuel Schyle 1961. (Primarily Malcolm X's debate on behalf of the nation of islam, with Baldwin giving occassional inputs.)

----

apart from themes obvious in the book's descriptions, a general heads up for themes of incest and sexual assault throughout his works.

#james baldwin#motivated by i think people here think it's harder to find resources and read than it actually is. so much stuff online!#motivation nr 2 wtf

12K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there, I’m planning on writing gothic/gothic romance fiction. Do you have any tips?

Do you also have any tips to not make your writing too repetitive? I have a habit of repeating words a lot.

Writing Notes: Gothic Fiction

Gothic Novel

European Romantic pseudomedieval fiction having a prevailing atmosphere of mystery and terror.

Its heyday was the 1790s, but it underwent frequent revivals in subsequent centuries.

Called Gothic because its imaginative impulse was drawn from medieval buildings and ruins, such novels commonly used settings such as castles or monasteries equipped with subterranean passages, dark battlements, hidden panels, and trapdoors.

The Gothic is characterized by its darkly picturesque scenery and its eerie stories of the macabre.

It draws its name and aesthetic inspiration from the Gothic architectural style of the Middle Ages — crumbling castles, isolated aristocratic estates, and spaces of decrepitude are familiar settings within the genre.

Gothic fiction is rooted in blending the old with the new.

As such, it often takes place during moments of historical transition, from the end of the medieval era to the beginnings of industrialization.

Contemporary technology and science are set alongside ancient backdrops, and this strange pairing helps create the pervasive sense of uncanniness and estrangement that the Gothic is known for.

Past & present fold in on each other; even as man’s technological advancements seem to make him increasingly powerful, history continues to haunt.

Elements of Gothic Literature

The Gothic is a genre of spiritual uncertainty: it creates encounters with the sublime and constantly explores events beyond explanation. Whether they feature supernatural phenomena or focus on the psychological torment of the protagonists, Gothic works terrify by showing readers the evils that inhabit our world.

CHARACTERS

Characters in Gothic fiction often find themselves in unfamiliar places, as they — and the readers — leave the safe world they knew behind.

Ghosts are right at home in the genre, where they’re used to explore themes of entrapment and isolation, while omens, curses, and superstitions add a further air of mystery.

ATMOSPHERE

Eeriness is as important as the scariness of the events themselves.

In a Gothic novel, the sky seems perpetually dark and stormy, the air filled with an unshakable chill.

THEMES

In addition to exploring spooky spaces, Gothic literature ventures into the dark recesses of the mind: the genre frequently confronts existential themes of madness, morality, and man pitted against God or nature.

Physical and mental ruin go hand in hand — as the ancient settings decay so do the characters’ grips on reality.

History of Gothic Literature

The vogue was initiated in England by Horace Walpole’s immensely successful The Castle of Otranto (1765).

His most respectable follower was Ann Radcliffe, whose The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) are among the best examples of the genre.

A more sensational type of Gothic romance exploiting horror and violence flourished in Germany and was introduced to England by Matthew Gregory Lewis with The Monk (1796).

The classic horror stories Frankenstein (1818), by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and Dracula (1897), by Bram Stoker, are in the Gothic tradition but introduce the existential nature of humankind as its definitive mystery and terror.

Easy targets for satire, the early Gothic romances died of their own extravagances of plot.

But Gothic atmospheric machinery continued to haunt the fiction of such major writers as:

Charlotte, Anne, and Emily Brontë, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and even Charles Dickens in Bleak House and Great Expectations.

In the second half of the 20th century, the term was applied to paperback romances having the same kind of themes and trappings similar to the originals.

Tips on Writing Gothic Fiction

SETTING

Gothic fiction can, of course, be set anywhere – but 2 key components of Gothic settings are as follows:

Gothic settings are isolated – a small community, a rural town, a single-family home on the open moors… wherever your Gothic story takes place, make sure that the setting is in isolation from the rest of the world. Places that are difficult to get to, with small populations, or are only home to one family or small group of people are ideal for weaving a Gothic tale. Even if your characters are not physically isolated – maybe they live in a city, for example – their isolation should be present in some way; maybe emotionally, maybe socially. There are plenty of options therein.

Gothic settings revolve around a home base – not necessarily a home or house, though that is quite common; but, with almost every Gothic tale, a central setting is introduced very quickly and almost all the action takes place inside or around it. This furthers that feeling of isolation, and also helps the house or laboratory or island or whatever else feel alive, as if it is a character itself.

These settings are often fun to develop and aid the story so, so much by being atmospheric and anthropomorphic.

By creating a strong setting and central location, you are setting up your Gothic fiction for success.

VOICE & CHARACTER

A strong voice, usually in first person, is a staple of Gothic fiction.

Gothic main characters are usually curious, determined, and unable to rest until whatever is going on around them is uncovered.

They are not faint of heart and often have experience dealing with hardship in the past; they are uniquely qualified for whatever disturbing events are going on.

Your character’s voice should be curious, but not paranoid; apprehensive, but not frightened or cowardly; and, above all, interesting.

As many Gothic are written in first person, you want your main character to take action and investigating the goings-on.

ATMOSPHERE

Similar to setting, it’s important to focus on atmosphere. Make sure you appeal to the five senses – let your reader know how it sounds, smells, feels!

The more details, the better; immerse your reader by making them feel as if they are actually in the space.

Often, as mentioned, Gothic novels take place in areas that are remote, experience frequent storms or bad weather, or otherwise have a very ominous environment.

Of course, Gothic novels can take place anywhere, but the takeaway here is to remember to highlight aspects that go beyond the visual.

SUBGENRE

Know what the genre within your Gothic work is or is going to be.

Are you writing a Gothic romance? A Gothic thriller? A Gothic horror? There are even types of books one might categorize as a “cozy Gothic” – taking the elements of a cozy mystery, but with a Gothic setting and characters.

There are some very specific geographical locations and time periods for Gothics, Victorian or Regency-era Northern England being a couple of them; but they are not all set in Europe in the 19th century, nor should they be.

Consider such settings as seen in Southern Gothic in the 2020s, for example, or Canadian Gothic (set anywhere in Canada, but usually southern and rural Ontario) in the late 90s, among many others. These are only a few examples of hundreds!

Dark academia titles can often fall into the Gothic genre as well, and, of course there are Gothic fantasy and sci-fi titles as well.

Carefully consider what sub-genre your Gothic fiction falls under before writing it, or during the early stages of writing as your work gets fleshed out. It may fall under just one category, or multiple! Either way, knowing this will help you write and later market your title.

MARKETING

Think about marketing at an early stage. Make it clear that it is a Gothic novel!

And consider publishing your title at a time when the Gothic genre might be in higher demand, such as during the month of October or the winter in general.

Appeal to fans of grim stories, horror romance, and what have you by theming your marketing.

If writing a Gothic novel is new for you, be sure to highlight that!

It can be exciting when an author tries out a new genre and moves into a new literary space. Be sure to let your readers know of this new venture.

Gothic Romance

As a genre, gothic fiction was first established with the publication of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto in 1764. Characterized by a dark, foreboding atmosphere and outlandish, sometimes grotesque, characters and events, gothic fiction has flourished and branched off into many different subgenres in the centuries since its creation.

While Walpole introduced what would later become the definitive tropes of the genre (creepy castles, cursed families, gloomy atmosphere), it was not until Ann Radcliffe’s A Sicilian Romance in 1790 that gothic romance began to develop as its own legitimate subgenre.

Radcliffe kept many of the same tropes established by Walpole’s work, such as isolated settings with semi-supernatural phenomena; however, her novels featured female protagonists battling through terrifying ordeals while struggling to be with their true loves.

This concept is what separates gothic romance from its cousin, gothic horror.

Female leads would come to dominate gothic romance, especially after the publication of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre in 1847.

A young woman struggling to maintain her independence as she falls for a dark, brooding, handsome man became a genre-defining plot of gothic romances published in the decades that followed.

A renewed public interest in gothic romance came on the heels of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca upon its publication in 1938.

Authors such as Victoria Holt, Mary Stewart, and Phyllis A. Whitney dominated the gothic romance trade paperback market from the 1960s to the 1990s.

The image of a young woman running away from a darkened castle became a staple of gothic romance novel covers.

In 1983, Gaywyck, by Vincent Virga, became the first published gay gothic romance.

Modern additions to the genre continue to reflect its interest in both terror and romance, while also delivering updated or reimagined versions of familiar tropes.

Tips for Avoiding Word Repetition

While repeating a word or phrase can add emphasis and rhythm to your writing, it can also make your writing awkward and difficult to read. When you’re not using repetition as a rhetorical device, repeating words can get in the way of good writing. Here are some tricks for avoiding unnecessary repetition of words:

Read your work aloud. Reading aloud will help you avoid unintentional word repetition. Reading your work aloud is an excellent way to both hear the sonic effects of your prose and catch awkward repeated sounds or other unintended effects.

Read your work backward. Reading your work backward is an editing trick that forces your brain to slow down and pay close attention to the individual sentences. Start at the end of a chapter, paragraph, or page and read the last sentence of that section. (Don’t read the sentence itself backward—it won’t make any sense.) Next, read the second-to-last sentence, and so on. This will allow you to work at the sentence level, catching any unintended repetition or other small mistakes that your brain naturally skims over.

Consult a thesaurus. So you’ve found a repeated word. Now what? You can try rearranging your sentence to get rid of the repeated word, or you can keep the sentence the same and plug in a different word in its place. If you’re at a loss, consult a thesaurus for a list of synonyms. You want your writing to sound like you, and to be accessible to your audience, so it’s best to avoid using words you aren’t familiar with. But if you find yourself unintentionally repeating the same word over and over, a thesaurus can help you identify another word that more precisely captures your meaning.

Some Writing Strategies to Avoid Repetition

Excerpts from writing tips on repetition by Dr. Ryan Shirey:

While repetition is not an inherently bad thing (and can quite often be used to great effect as in the classical rhetorical technique of anaphora), most of us want to make sure that we’re not boring our readers by saying the same things over and over again without any variation or development.

If you’re worried about repeating ideas, then one of the easiest and most illuminating things that you can do is to reverse outline your draft. When you reverse outline, you take your draft and distill each idea and piece of evidence back into an outline. Some writers like to do this in the margins and others prefer a separate sheet of paper. Whatever your preference, a reverse outline will let you see rather clearly whether or not you’ve returned to the same idea or piece of evidence multiple times in the same essay. If you find that you have, you can think about rearranging or cutting paragraphs as necessary.

Another strategy if you’re worried about repeating ideas is to use different colored highlighters, colored pencils, or coloring tools in a word processing program to mark areas of your text where you’re working on specific ideas. If I’m writing a paper on the history of the run up to World War I, for example, I might decide to mark all the areas where I discuss treaty arrangements in green, all the areas where I discuss colonial expansion in blue, the parts that discuss arms manufacturing and trade in red, and so on. Once I’ve visualized these ideas with color, I can see more easily whether or not I keep returning to the same topics or whether I need to restructure any portions of my essay. Be careful, though–you don’t want to create artificial distinctions that might negatively impact your overall point. For instance, if a conflict over colonial expansion leads to a treaty arrangement, I would need to be very careful about using the context in which I’m discussing that treaty dictate how I code that sentence or paragraph.

If you’re worried about repeating words or phrases, you can use the “find” feature in your word processing program to highlight all of the instances where you’ve used it. Once you’ve identified the problem areas, you can look for ways to combine sentences using coordination or subordination, replace nouns with pronouns, or (very carefully) use a thesaurus to diversify your vocabulary.

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6 ⚜ More: Writing Notes & References

Hope this helps with your writing!

#anonymous#gothic#writeblr#literature#dark academia#writers on tumblr#writing tips#writing advice#on writing#writing reference#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#romance#writing resources

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astro observations part 5

🐝 Saturn in 5th house individuals don’t like parties

🐝 All the Cancer Sun guys i met were either metalheads or femboys, i swear there’s no in-between

🐝 Libra Sun love nature. They're the type to spend weekends hiking, going on picnics with friends & family

🐝 Check out asteroid Armisticia (1464) in synastry. If you’ve got it conjuncting personal planets or angles, it indicates that you and the other person are on the same page when it comes to conflict, making it easier to find a solution to the problem and make peace

🐝 Aquarius on 4th house cusp individuals might have grown in a LGBTQ+ family. They might have got adopted by a gay/lesbian couple

🐝 When Cancer Moons go to college, they usually choose a college close to their hometown and commute to it

🐝 Trines to your Mercury show what type of writer you would be

If Mercury trines Moon - poetry, children's books (0-6 yo)

If Mercury trines Venus - romance novels, art books, chick-lit fiction (ik it's basically dead, but long live the internet)

If Mercury trines Mars - action & adventure novels, war novels

If Mercury trines Jupiter - young adults fiction, comedy books, travel literature, religion/spirituality books

If Mercury trines Saturn - contemporary novels, non-fiction books (memoirs, biographies, academic works, etc.)

If Mercury trines Uranus - sci-fi novels, (combined with Pluto) dystopian novels

If Mercury trines Neptune - fantasy novels, children's books (6-12 yo)

If Mercury trines Pluto - mystery novels, horror novels, thrillers

Hope you enjoyed today's post!❤️

Post ideas are welcomed in the comments!

See you soon! ଘ(੭ˊᵕˋ)੭* ੈ✩‧

#astro#astro community#astro placements#astrology#asteroids#astro observations#astro posts#astro notes#astrology notes#astroblr#astro blog#astrology tumblr#astrology community#saturn in 5th house#cancer#cancer sun#libra#libra sun#cancer moon#mercury

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wuxia is a popular Chinese literary genre, also known as wuxia xiaoshuo (武 侠小说, literally “martial arts fiction”). The genre consists of three components: wu (武, “martial arts” or “the arts of fighting”), xia (侠, “knighterrant”), and xiaoshuo (小说, “fiction”) (Ni 1980). Rooted in the spiritual and ideological traditions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, wuxia stories feature the adventures of a warrior xia and his/her skills in martial arts, as well as the themes or principles of xia (e.g. chivalry, altruism, justice, and righteousness). An important aspect of wuxia is its setting, known as jianghu (江湖, literally “rivers and lakes”), that is, an alternate society created by xia in opposition to the authority (Chen 2010, 108). This alternate society finds a concrete form in “the complex of inns, highways and waterways, deserted temples, bandits’ lairs, and stretches of wilderness at the geographic and moral margins of settled society” (Hamm 2005, 17). Jianghu also refers to a semi-Utopia where xia punishes evil and exalts goodness out of their chivalric imperative to “carry out the Way on Heaven’s behalf” (Chen 2010, 109). Classics such as Water Margin (or Outlaws of the Marsh) and Journey to the West solidified wuxia as a genre, with the former establishing “the literary formula emulated by later writers whereby righteous men choose to become outlaws rather than serve under corrupt administrations” (Teo 2015, 20) and the latter being “a source for supernatural elements in contemporary wuxia literature” (Rehling 2012, 73). Dang Li (2021) The Transcultural Flow and Consumption of Online Wuxia Literature through Fan-based Translation, Interventions, 23:7, 1041-1065, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2020.1854815 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2020.1854815

#wuxia#cdrama#jianghu#language#translation#chinese#my stuff#sorry again gonna keep posting interesting snippets cuz maybe one or two other folks will also be interested

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

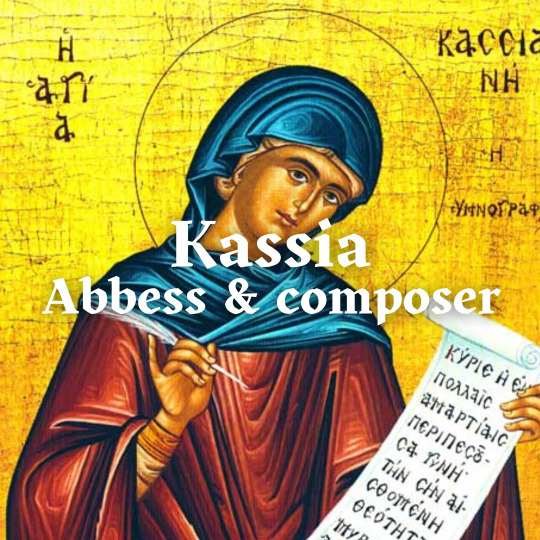

Abbess, composer, poet, philosopher: Kassia (c.810–c.865) was a multi-talented woman and one of the most prominent female voices in the Byzantine world.

The outspoken candidate

Kassia was born into an aristocratic family; her father, a military official (Kandidatos) at the imperial court, ensured she received an exceptional education. In a society where women had a relatively high literacy rate, Kassia’s intellect and skills stood out. As a teenager, she earned praise from Theodore the Studite, who wrote:

"While you have not surpassed those of old, of whose wisdom and education we in this generation, both men and women, fall far short—and immeasurably so—you have done so with regard to those of the present, since the fair form of your discourse has far more beauty than a mere specious prettiness"

From a young age, Kassia demonstrated her piety and strong personality. She supported a monk imprisoned by the Iconoclast authorities and likely began contemplating a monastic life early on.

She participated in a bride show at the palace, where the young Emperor Theophilos sought to choose his empress. Theophilos reportedly remarked to her, "From woman come evils," referencing Eve’s sin. Kassia, undeterred, replied, "But from woman sprang many blessings," alluding to the Virgin Mary.

Kassia was not chosen. Her poem On Stupidity may reflect her thoughts on the encounter:

It is terrible for a stupid person to possess some knowledge;

and if he has an opinion, it’s even worse;

but if a stupid man is young and in a position of power,

alas and woe and what a disaster.

Woe, O Lord, if a stupid person attempts to be clever;

where does one flee, where does one turn, how does one endure?

The abbess

After this experience, Kassia was reportedly delighted to pursue her true calling as a nun. She founded her own monastery in Constantinople, where she served as abbess.

Life in a women’s monastery offered significant opportunities. Nuns held all key offices within the monastery, and the abbess wielded complete authority. She carried a staff like her male counterparts, sat on a throne during church services, and could even preach. In some cases, abbesses were respected as spiritual authorities for men as well as women.

Kassia’s writings during this time reveal a vivid personality. She was outspoken and direct, with little tolerance for hypocrisy or falsehood. At times, she came across as impatient or acerbic, but her works also show a sensitive, compassionate side and an emphasis on genuine friendships.

The artist

Kassia dedicated her days to “philosophizing,” writing epigrams and composing gnomic poetry. However, she is best remembered for her liturgical hymns. As one of the few female hymnographers in Byzantine history (alongside contemporaries like Theodosia and Thekla), Kassia is the only woman whose works were incorporated into the official Byzantine hymnals, which remain in use today. The 14th-century writer Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos ranked her eleventh on his list of the most influential composers.

Kassia’s writings often highlighted the contributions and courage of women. She rejected stereotypes of female weakness and submission, as reflected in this poem:

I hate silence, when it is a time for speaking.

I hate the one who conforms to all ways.

She even hinted at the idea of female superiority in her poem Woman:

Esdras is witness that women

Together with truth prevail over all.

Today, Kassia is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with her likeness depicted in icons. Her feast day is celebrated on September 7, and her most famous hymn is still chanted during the liturgy for Holy Wednesday each year.

youtube

Enjoyed this post? You can support me on Ko-fi!

Further reading:

Herrin Judith, “Changing functions of monasteries for women during Byzantine iconoclasm”, in: Garland Lynda (ed.), Byzantine Women, Varieties of Experience 800-1200

Sherry Kurt, Kassia the Nun in context: The Religious Thought of a Ninth-Century Byzantine Monastic

#kassia#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#9th century#byzantine history#byzantine empire#female authors#female composers#feminism#middle ages#medieval women#medieval history

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're thrilled to publish our newest piece—this time by a returning writer. @areyougonnabe first wrote for us about Tumblr back in 2020 (and also was one of the podcast's final guests this year before we went on hiatus). Now she's back with a deep dive into contemporary classic rock fandom—the shippy, transformative kind—and the interesting temporal shift that happens within historical RPF:

Today’s young Beatles fans can consume every atom of sound and image from the 1960s, but however fond they are of Ringo’s silly tweets or Paul’s new music, there’s a line of demarcation somewhere in the past which spiritually separates then from now. Real-time, ongoing celebrity pop culture can be full of anxieties, but an older band’s story can be more like reading a book that was already written.

Read or listen to an audio version via the link above—and to support more in-depth fan culture journalism, consider becoming a patron!

#fandom#fansplaining#allegra rosenberg#the beatles#mclennon#music fandom#RPF#historical RPF#classic rock#fanworks#fanfiction

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

I should probably talk about the context because the character depicted in this illustration is not the most famous or popular even in his homeland. Outside of Russia, you may have heard of him in connection with the novel "Wings". But Mikhail Kuzmin is an interesting figure as a poet, writer, and representative of the queer culture of the Russian Empire. I think it can be noted that I enjoy studying the history and culture of the LGBTQ+ community of different eras, so this personality has already interested me before. However, I found a great source of inspiration in his diaries, which he kept for a long time and shared his worldview, notes on creativity, contemporaries, life, and his romantic relationships. For this illustration, I used an excerpt from the 1906 entries, which is dedicated to celebrating Easter, but also addresses Kuzmin's spiritual doubts and the conflict of his religiosity with the theme of his orientation. I hope I can shed some light on this unusual topic with my art.

#illustration#art#russian literature#mikhail kuzmin#20th century#1900s#art nouveau#decadance#dark aesthetic#dark art#artists on tumblr#queer history#iconography#fanart#historical fandom

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remedios Varo, Icono, (Icon), 1945. Oil on gold leaf gilded wood with mother-of-pearl incrustations. Ícono was built as a medieval altarpiece and it is usually closed to preserve the energy of the image, and open only for specific liturgical feasts.

First photograph is the altarpiece open and the second is the alterpiece closed. "Ícono" stands out in Remedios Varo's production by its particular structure, built as a medieval altarpiece usually closed to preserve the energy of the image, and open only for specific liturgical feasts. Inside, a winged unicycle is carrying a cylindrical-shaped tower in a starry landscape, natural satellites and birds which evoke a fantastic universe teeming with spiritual allusions. The work depicts mind as substance in ongoing transformation, marked by the implications of contemporary psychology, ancestral rituals, and magic realism derived from the ideas by Russian mystic and writer George Ivanovich Gurdjieff.

#Remedios Varo#Icono#Icon#1945#medieval art#altarpiece#unicycle#starry night#artwork#magical realism#oil on wood#gold leaf#gilded#mother-of-pearl#wood art#surrelism#pearl#nacre#art#fine art#fineart#painting#art history#history of art#women in art#women artists

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

💋 I Love AI made the photo Lan with silver curly hair and tattooed (大波浪的銀髮刺青蘭/ ) Unreal but delightful beauty不真實卻令人開懷的美~*) \(^0^)/

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Reading Book . . .

「師傅,工廠已經這樣了"就去它娘的吧",餓不死土裡的蚯蚓就餓不死咱們工人階級。 If an earthworm in the ground won't starve to death, then neither will we, the working class.” He”」

─ Mo Yan, Shifu, You'll Do Anything for a Laugh: A Novel /莫言 《師傅越來越幽默》第5章. (Chinese writer, b. 1955) Literary movement Magical & realism. Nobel Prize winner in Literature 2012. His original name is Guan Moye (管謨業).

📌 He has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature 2012 for his work which "with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary". Among the works highlighted by the Nobel judges were Red Sorghum (1987) and Big Breasts & Wide Hips (2004), as well as The Garlic Ballads.

《師傅越來越幽默》Shifu, You'll Do Anything for a Laugh | Book Read Free In English 👇 https://bookreadfree.com/396781/9757727.amp 中文 👇 https://read.99csw.com/book/3359/

and Listening for novel 👇 你也可以用聽的 ;-)

🎧 莫言的中篇小說欣賞:《師傅越來越幽默》Shifu, You'll Do Anything for a Laugh via 字裡行間一點悟 @Calligraphy-insight Channel on YouTube

youtube

About writer - Mo Yan 莫言

China''s most critically acclaimed author, has changed the face of his country''s contemporary literature with such daring and masterly novels as Red Sorghum, The Garlic Ballads, and The Republic of Wine. In this collection of eight astonishing stories--the title story of which has been adapted to film by the award-winning director of Red Sorghum Zhang Yimou--Mo Yan shows why he is also China''s leading writer of short fiction.

His passion for writing shaped by his own experience of almost unimaginable poverty as a child, Mo Yan uses his talent to expose the harsh abuses of an oppressive society. In these stories he writes of those who suffer, physically and spiritually, under its yoke: the newly unemployed factory worker who hits upon an ingenious financial opportunity; two former lovers revisiting their passion fleetingly before returning to their spouses; young couples willing to pay for a place to share their love in private; the abandoned baby brought home by a soldier to his unsympathetic wife; the impoverished child who must subsist on a diet of iron and steel; the young bride willing to go to any length to escape an odious, arranged marriage. Never didactic, Mo''s fiction ranges from tragedy to wicked satire, rage to whimsy, magical fable to harsh realism, from impassioned pleas on behalf of struggling workers to paeans to romantic love.

#chu lan#ai photo generator#大波浪的銀髮刺青-蘭#taiwan artist#love that lan with silver curly hair and tattooed#莫言#mo yan#字裡行間一點悟 @Calligraphy-insight#live love laugh#thank you xoxo#reading#chinese novel#Youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

My actual presumption re: Akutagawa's knightliness and amnesia is that Bram and Akutagawa are sharing a skinsuit, consequently weaving their consciousnesses into the most gothic twink the modern mind is capable of conceiving. (You might assume adding Poe or Percy Shelley would make for a more gothic twink, but the addition of either would destabilize the whole twink, and it would either become immediately beset with late stage rabies or it would drown itself within moments of its wretched birth).

Akutagawa is not entirely Akutagawa. The armor looks decidedly more draconic in the teaser we received at the end of S5, wherein Akutagawa seems to have wholly returned to Atsushi's side— fulfilling Shibusawa's climactic fight comment in Dead Apple that the dragon and tiger deserve each other— in time for the overarching climax.

(That's why I think Fyodor set Shibusawa on Atsushi— he mistook Shibusawa for the dragon that would engage with the tiger, creating a singularity that is the "book" insofar as the book exists. Really, it's a white hole that connects realities, either metaphorically or literally. Or, so I think.)

So, Akutagawa has not yet actualized into the dragon that his rivalry with Atsushi has allowed him to cultivate into over the course of the story, but he's very close. He's also too much of a knight right now, which is Bram's role— Akutagawa was always a rook. Even where Akutagawa is protective, he is not chivalrous or knightly, and his protectiveness does not arise from ordainment or ritual oaths of public service but from the individual promises he's made to others and his city. He also doesn't remember Atsushi. Bram, meanwhile, is nobility with vassals to protect, empowered by the princess to whom he swore fealty with the weight of his ordained station. He also has never met Atsushi.

However, this knightly Akutagawa is not all Bram either. His precise, clipped, and cutting speaking pattern slips between Bram's romantic, archaic denouncements. Akutagawa recalls his own words from his first appearance. He appeared where he was needed most, and he's remaining true to his promises. Rashomon responds to him. Akutagawa is very much there, but insofar as he's backseat driving, Bram has the firmer grip on the wheel.

Notably, knight!Akutagawa seemingly quotes the Kolbrin Bible, after which the chapter is named, which is something of a conspiracy theorist's secular bible that mashes together Celtic and Druid mysticism, Judaism and Egyptology. Allegedly, it's a manuscript written 3,600 years ago that was translated between WW1 and WW2. There is no evidence that any of this is true— it was most likely produced in the 90s, based on its very anachronistic language.

I fucking hate contemporary occultism, I tried to dismiss the Kolbrin Bible as the relevant reference, but I haven't yet found anything more likely (although the day is young). There's some foundation for referencing an esoteric occult publication: the somewhat notorious founder of theosophy, Helena Pavlovna Blavatsky, published a theosophical interpretation of Dostoevsky months after his death; spiritualism absolutely influenced fiction and sci-fi; WB Yeats and George William Russell (luminaries of modern Irish literature) were involved with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and their works were shaped by their interests in mysticism and the occult. More saliently, Bram Stoker corresponded with prominent occultists and harbored a tempered "writer's interest" in the occult. I am not getting into Houdini's former friend's interest in spiritualism because I hate him, and thinking about him makes me spit bile, but he's another prominent example.

So, there's cause for the reference, and, maybe this sort of text feels right for bsd, which is also an anachronistic alternative history that's mashing together a whole lot of eastern and western influences with little regard for propriety. I'm still not pleased with it, and I hope my shallow look into the imagery from this most recent chapter led me into the enshittified part of the surface web. But, there are some apparent threads worth exploring.

Prior to Akutagawa name dropping the Harbor of Sorrow, Fyodor seemingly also references the Kolbrin Bible (which is, to mirror Fyodor's language below, an imitation religious text):

"The Harbour of Sorrow we leave behind and with four ships sail towards the sunsetting."

At first, I thought the setting sun imagery in Fyodor's exposition was an uncharacteristically blunt reference to Dazai Osamu's novel, but the setting sun in the Kolbrin Bible seems more likely, since in the latter there is an intentional journey towards the setting sun, while the setting sun in Dazai Osamu's novel reflects an aristocratic family's necrotizing decline.

The Harbour of Sorrow in the Kolbrin Bible is described thusly:

They came to the Harbour of Sorrow, which lies by the Hazy Sea, away from the Land of Mists. There great trees grew and smaller trees upon them, and moss hung from them like door curtains. It lay near the great shallow waters South of the Isle of Hawhige and North of the Sea Pass. Green pearls are found there. Many died in the Harbour of Sorrow, for it was a place with a curse upon it, which caused an evil sickness. The Sons of Fire came with Hoskiah and saved them, and they came to this place and built a city.

(I can't help but acknowledge that the character for "Asagiri" in Kafka Asagiri refers to morning mist.)

In modern Western mysticism, "sons of fire" could mean a few different things, but in this context, I'm inclined towards the epithet for Western spiritualists' bastardization of sage kings— "divine" teachers. It may also reference Aaron's sons in the Bible, who were killed by Moses after they committed a profane act before God. As a reminder, shortly before stabilizing Yokohama in collaboration with Mori, Taneda, and Natsume, Fukuzawa either participated in or permitted acts that appear to have been assassinations to facilitate Japan's withdrawal from the Great War, which engendered in him self loathing and shame and shattered his relationship with four others.

(As an aside, I don't actually think Fukuzawa assassinated anyone, or was an assassin by trade— the five swords of Japan are a specific reference to five swords and their mythologies, and I think he must have been the ceremonial purification sword that was never meant to be sharp. It was meant to cut only evil. I think he allowed something to happen that violated oaths he made, so he exiled himself like a ronin who killed his master. The only reason we think he killed anyone, despite Ranpo acknowledging Fukuzawa wasn't an assassin in Untold Origins, is because the Decay of Angel fed "evidence" to the government officials who Nikolai later killed to incite them into pursuing the Agency— there is nothing suggesting that evidence has any merit, and much suggesting it's falsified. This is why I always say not to rely on the bsd wiki— it tends to take these things at face value and doesn't qualify unreliable information.)

Anyway! There are other threads to connect the text above to bsd, including the foreigners present in Yokohama and the Kolbrin Bible's British Isles settings and US + UK modern mysticism. But, to move on to other passages connected to the Harbor of Sorrow.

“When some of us came from the Harbour of Sorrow, we were full of praise at our deliverance from death, but amid the forests of fruitfulness, much of our gratitude and will was lost. Why must men always be better men in the face of disaster and in the midst of privation, than in the green fields of peace and plenty? Does this not answer the questions of many who ask why there is sorrow and suffering on Earth? Why is it the lot of men to struggle and suffer, if not to make better men?

...

"Many who are with us in the light will join us, and then we shall be stronger in arms and strengthened in belief. (Annotation: How few came!) Yet our destiny lies among the barbarians. They are fine, upright men endowed with courage, do not belittle their ways, but bring them into the light.

"Our city was not founded as a marketplace, a place for exchanging only the things of Earth. Neither did we come here as conquerors, but as men seeking refuge.

“My trusted ones, remember that the road of life is not smooth, neither is the way of survival a path of grass. The most needful thing for any people who wish to survive is self-discipline. Think less of gold and more of the iron which protects the gold. Remember, too, these words from the Book of Mithram, The keenest sword is useless unless it be held in the hand of a resolute man. Also, the man who has gold keeps it in peace if he tends his bowstring."

I have not read the Kolbrin Bible, I have immense distaste for modern occultism/spiritualism/mysticism outside of limited and carefully curated, contextualized slices of the same. I also don't make a habit of overly familiarizing myself with the British Isles. I don't have much frame of reference for interpreting the above.

But on a surface reading, the passages in the Kolbrin Bible that refer to the Harbor of Sorrow touch on similar-to-bsd themes of intentional community and finding purpose in protecting and cultivating the light in both the wake and the eve of immense darkness, and finding companionship in those who share your purpose and resolve no matter how differently they may approach the same.

Further, they both embrace that it's not about being golden, but protecting what is gold, which is Kyouka's core arc in Dead Apple as she transitions from trying to protect Atsushi as someone she considers untouched by the darkness within her, to realizing that Atsushi, too, has killed, and that her desire to use Demon Snow to protect those she loves isn't shameful or a betrayal of her mother's memory. This is something that I think the fandom often misunderstands about bsd— the light and dark do not exist in opposition, but in duality. The characters immersed in the dark do not need to be saved; the characters in the twilight have their reasons for finding purpose elsewhere, but that doesn't strip the love they had while in the dark. If anything, it makes it easier for them to realize that love was and still is there.

That interplay of light and dark (which is also the title of a Natsume Soseki novel) is where Akutagawa and Bram begin to melt most into one another. They have both been dehumanized, hated, and killed; rejected and stripped of dignity, robbed of those they loved by petty violence. Neither seeks to save anyone other than those to whom they've sworn to try, and they've both been reckless with who they've killed. Nevertheless, they love fiercely, and where their fear is defensive, their anger is avenging (Akutagawa's furious pursuit of the reckless murderers in 55 Minutes, the implication that Bram was fighting to protect his vassals when he was subdued as a calamity previously).

But they aren't evil. Evilness isn't a person, it's cowardice and weakness and fear. They've both grappled with the desire to succumb to their grief and their anger and their terror. But they struggle against those urges in themselves with fierce resolve.

It's the sort of resolve that Fyodor lacks. Fyodor, codependent on his dehumanization, claims that there's death in salvation only because he can't bear to keep living under the weight of humanity's rejection but is too weak and afraid of being alone to die without taking everyone else with him. Fyodor's disgusted by Atsushi's humanity and love because he sees in it what he's convinced himself he can never be afforded. But Bram and Akutagawa both have always had the certainty of love in their families, and then in Aya and in Higuchi.

There is no salvation in death or goodness; there is no sure path towards resolution or closure. There isn't any inherent meaning to our pain, and even those of us who live in relative peace are walking on a knife's edge over uncertainty and chaos. But, we can choose to accept love, and we can choose to love others. Isn't that a little bit wonderful?

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd 119#bsd fyodor#bsd akutagawa#bsd bram#etc etc#sorry there's a lot here! if i were kinder i would add headings for you. but im not and im late on turning in some overdue work 🥰

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources on Louisiana Voodoo

door in New Orleans by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques

For better or worse, and almost always downright wrong, the Louisiana Voodoo religion, and its form of practice Louisiana Hoodoo, are likely to come up in any depiction of the state of Louisiana. I’ve created a list of works on contemporary and historical Louisiana Voodoo/Hoodoo for anyone who’d like to learn more about what this tradition is and what it is not (hint: it developed completely separately from Haitian Vodou which now is the most visible form of Voodoo present in New Orleans and is unique and distinct from other practices called Hoodoo across America) or would like to depict it in a non-stereotypical way, I’ve listed them in chronological order, and bolded those works I consider the best, many of which are primary sources. Please keep a few things in mind. Almost all sources presented unfortunately have their biases. As ethnographies Hurston’s work no longer represent best practices in Anthropology, and has been suspected of embellishment and sensationalism on this topic. Additionally, her portrayal is of the religion as it was nearly 100 years ago- all traditions change over time. Likewise, Teish is extremely valuable for providing an inside view into the practice, but certain views, as on Ancient Egypt, may be offensive now. I have chosen to include the non-academic works by Alvarado and Filan for the research on historical Voodoo they did with regards to the Federal Writer’s Project that is not readily accessible, HOWEVER, this is NOT a guide to teach you to practice this closed tradition, and again some of the opinions are suspect- DO NOT use sage, which is part of Native practice and destroys local environments. I do not support every view expressed, but think even when wrong these sources present something to be learned about the way we treat culture.

*To compare Louisiana Voodoo with other traditions see the chapter on Haitian Vodou in Creole Religions of the Caribbean by Olmos and Paravinsi-Gebert. Additionally, many songs and chants were originally in Louisiana Creole (different from the Louisiana French dialect), which is now severely endangered. You can study the language in Ti Liv Kreyol by Guillery-Chatman et. Al.

Le Petit Albert by Albertus Parvus Lucius (1706) grimoire widely circulated in France in the 18th century, brought to the colony & significantly impacted Hoodoo

Mules and Men by Zora Neale Hurston (1935)

Spirit World-Photographs & Journal: Pattern in the Expressive Folk Culture of Afro-American New Orleans by Michael P. Smith (1984)

Jambalaya: The Natural Woman's Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish (1985)

Eve’s Bayou (1997), some of the visual depiction is derived from Haitian Vodou however

Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce by Carolyn Morrow Long (2001)

A New Orleans Voodoo Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau by Carolyn Morrow Long (2006)

LSU Master’s Thesis: A Trinity of Beliefs and a Unity of the Sacred: Modern Vodou Practices in New Orleans by Elizabeth Thomas Crocker (Louisiana Voodoo starts on page 50 and includes an interview of Brenda Marie Osbey)

“Yoruba Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo” by Ina J. Fandrich (2007)

The New Orleans Voodoo Handbook by Kenaz Filan (2011)

“Why We Can’t Talk To You About Voodoo” by Brenda Marie Osbey (2011)

The Tomb of Marie Laveau In St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 by Carolyn Morrow Long (2016)

Lemonade, visual album by Beyonce (2016)

How to Make Lemonade, book by Beyonce (2016)

“Work the Root: Black Feminism, Hoodoo Love Rituals, and Practices of Freedom” by Lyndsey Stewart (2017)

The Lemonade Reader edited by Kinitra D. Brooks and Kameelah L. Martin (2019)

The Magic of Marie Laveau by Denise Alvarado (2020)

In Our Mother’s Gardens (2021), documentary on Netflix, around 1 hour mark traditional offering to the ancestors by Dr. Zauditu-Selassie

“Playing the Bamboula” rhythm for honoring ancestors associated with historical Voodoo

Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans 1880-1940 by Kodi A. Roberts (2023)

The Marie Laveau Grimoire by Denise Alvarado (2024)

Voodoo: An African American Religion by Jeffrey E. Anderson (2024)

Given the interest in Ryan Coogler’s Sinners I’ve been getting requests to list Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition by Yvonne P. Chireau (film consultant) and Mojo Workin’: The Old African American Hoodoo System by Katrina Hazzard-Donald. These are good sources for a general survey of African diaspora spiritual practices but contain almost no information on or specific to the uniqueness of Louisiana Voodoo and in some cases repeat older inaccuracies. I want to mention here that the term Hoodoo likely comes from the Louisiana Voodoo tradition but transformed to become a catch all phrase for several different and varying African based practices across America.

#I’ll continue to update as I find more sources#Please be respectful of other people’s religion#Louisiana Voodoo#In the case of authors behind a paywall or whom you do not wish to support I highly recommend your local library#Voodoo#some consider voodoo/hoodoo diff today but this may not always have been the case historically so they have been presented together here#Sinners#ryan coogler

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Ojibwe Characters: A Basic Guide

Creating well-rounded, respectful Ojibwe characters takes a bit of research and consideration. This guide gives a quick overview of things to think about when writing Ojibwe people and incorporates some context to avoid common pitfalls. Writing any Indigenous character means approaching with care, so let’s dive in!

1. Understand Ojibwe Culture and Community

Get to know the basics of Ojibwe culture, beliefs, and values. My people, the Ojibwe (also spelled Ojibwa, Ojibway, or Chippewa) are part of the Anishinaabe people. We are present across Canada and the northern U.S. Midwest, with diverse communities that each have their own practices and perspectives.

Community-centered thinking: Many Ojibwe people have a strong sense of connection to community and family. Recognize that we tend to prioritize our connections and often have a deep relationship with our elders and youth.

Language and terminology: Use respectful terms. The Ojibwe language (Anishinaabemowin) is central to identity, even if a character doesn’t speak it fluently.

2. Avoid “Spiritual Mysticism” Stereotypes

Steer clear of clichés about Indigenous mysticism. Instead, focus on how Ojibwe spirituality is lived in everyday ways—whether through ceremonies like smudging, seasonal celebrations, or even just respecting the land and ancestors. Characters don’t need to be “shamans” or mystical guides to show their culture.

Spirituality in balance: While many Ojibwe people honor spirituality, each person practices differently. Just as in any culture, some may be very connected to it, while others are more secular.

3. Use Realistic Names and Nicknames

Ojibwe names often have meaning and are given in specific cultural contexts, sometimes in ceremonies or after significant events. If using an Ojibwe name, make sure it’s well-researched, and consider including a backstory on how it was given to your character.

Nicknames are common and can range from family names to personal traits. Think about nicknames that resonate with your character’s personality and family background rather than something “exotified.”

4. Research Traditional Roles, Not “Warrior” Stereotypes

Ojibwe people are often cast as “warriors” or “stoic fighters,” which is limiting. In reality, Ojibwe communities have had diverse roles throughout history, including diplomats, healers, artisans, teachers, and more.

Consider what makes sense for the time and place your character lives in—an Ojibwe character could be a modern-day artist, teacher, software developer, veteran, or lawyer. Complex portrayals highlight our adaptability and contemporary lives.

5. Acknowledge History Without Making Trauma the Focus

Many Indigenous communities, including Ojibwe, have endured hardships like colonization, boarding schools, and loss of land. However, it’s essential not to reduce characters to trauma alone. Show their resilience, joy, humor, and everyday experiences alongside their histories.

Avoid “tragic backstory syndrome”: A good character is multidimensional. Balance struggles with strengths, showing how they thrive in the modern world while honoring their roots.

6. Respect Language and Use It Thoughtfully

If your character speaks or knows Anishinaabemowin, use it respectfully and sparingly unless you're fluent. Small phrases or words can add depth without risking inaccuracies. If they use Ojibwe words, provide a translation for context.

Resource suggestion: Check out the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary for phrases, pronunciation, and examples of how the language fits into daily life.

7. Research and Connect With Indigenous Resources

For non-Indigenous writers, it’s important to engage with authentic sources and, if possible, speak with Ojibwe individuals or consult books, articles, or online resources created by Ojibwe authors and scholars.

Media to check out: Look for books, films, and articles by Ojibwe creators (such as works by Louise Erdrich or Gerald Vizenor) for direct perspectives.

8. Show Ojibwe Humor and Resilience

Ojibwe humor is a big part of the culture—often dry, sarcastic, and shared among family and friends. Including humor adds authenticity and breaks away from “stoic” stereotypes. Remember, we laugh, joke, and enjoy life as much as anyone else!

9. Give Credit and Respect Acknowledgments

Mention that you’ve researched Ojibwe culture and language if possible, and consider a small acknowledgment to the sources you used. It shows respect for our culture and the people who helped make the character accurate and relatable.

Sample Character Traits for Inspiration:

Joyful and witty, known for quick humor but deeply thoughtful.

Family-oriented, regularly calling or visiting relatives or helping out in the community.

Resourceful and resilient, finding creative ways to navigate the modern world while honoring traditional values.

Quietly proud, choosing to celebrate their heritage subtly but meaningfully, like wearing Ojibwe beadwork or carrying traditional items.

Writing an Ojibwe character respectfully and fully means creating someone real and complex. Remember, the best portrayals come from genuine understanding and thoughtful depiction. Happy writing, and Chi miigwech (thank you very much) for taking the time to represent us well! 🪶✨

And if you are ever confused, ask! I love answering questions about my culture!

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medusa Spitblossoms Medusa: A Mythological Tale of Maiden to Monstrosity

Medusa, a name that evokes both fascination and terror, is one of the most intriguing figures in Greek mythology. This captivating Gorgon, known for her hair of serpents and the ability to turn mortals into stone, has been the subject of countless artistic interpretations, symbolizing power, femininity, and the complex nature of humanity. Although Medusa is not considered a goddess, she is an important and unique character from Greek mythology, specifically one of the Gorgons, three sisters known for their monstrous appearance.

While Medusa is a notable figure in Greek mythology and has been the subject of various artistic interpretations and symbolism, she is not worshipped as a goddess in the traditional sense. Over time, Medusa myth has been used as a symbol to protect and ward off the negative, representing a dangerous threat meant to deter other dangerous threats, an image of evil to repel evil. In this blog post, we will delve into the myth of Medusa and explore the profound symbolism associated with her enigmatic persona.

Medusa, a name that evokes both fascination and terror, is one of the most intriguing figures in Greek mythology. This captivating Gorgon, known for her hair of serpents and the ability to turn mortals into stone, has been the subject of countless artistic interpretations, symbolizing power, femininity, and the complex nature of humanity. Although Medusa is not considered a goddess, she is an important and unique character from Greek mythology, specifically one of the Gorgons, three sisters known for their monstrous appearance.

While Medusa is a notable figure in Greek mythology and has been the subject of various artistic interpretations and symbolism, she is not worshipped as a goddess in the traditional sense. Over time, Medusa myth has been used as a symbol to protect and ward off the negative, representing a dangerous threat meant to deter other dangerous threats, an image of evil to repel evil. In this blog post, we will delve into the myth of Medusa and explore the profound symbolism associated with her enigmatic persona.

The Mythical Origins of Medusa:

Medusa Greek mythology was once a beautiful mortal woman with flowing hair. However, due to a series of unfortunate events, she was cursed by the goddess Athena, transforming her into a monstrous creature. Her once luscious locks were replaced by serpents, and her gaze became the deadly weapon that turned any who looked upon her to stone. This tale of transformation and divine punishment carries deep symbolic meaning, resonating with themes of beauty, envy, and the consequences of hubris.

Medusa Spiritual Meaning:

While Medusa mythology is often depicted as a terrifying monster, she also embodies a potent symbol of feminine power. Her serpentine hair represents primordial wisdom, connected to the chthonic forces of nature and the untamed aspects of femininity. Medusa challenges traditional notions of beauty and subverts the male gaze, offering an alternative archetype of strength and resilience for women throughout history. In modern times, she has become an icon for female empowerment, encouraging women to embrace their unique qualities and reclaim their narrative.

Medusa in Art and Literature:

Throughout the ages, artists and writers have been captivated by Medusa's enigmatic allure, immortalizing her in various forms. From ancient Greek pottery to Renaissance paintings and contemporary sculptures, Medusa's image continues to inspire creative interpretations. Notable works such as Caravaggio's "Medusa" and Bernini's "Medusa Shield" showcase the enduring fascination with this mythological figure. Furthermore, Medusa's presence in literature, from Ovid's "Metamorphoses" to contemporary novels, reflects her enduring relevance as a complex symbol of power, desire, and the human condition.

Medusa as a Metaphor for the Human Psyche:

Medusa symbolism as a figure of feminine power, Medusa also represents the intricate workings of the human psyche. The concept of "petrification" associated with her gaze can be interpreted as the fear of facing our deepest fears and desires, the paralysis that comes with inaction, or the consequences of avoiding self-reflection. Medusa reminds us that embracing and integrating our shadow selves is a crucial step towards personal growth and self-actualization.

Medusa and Poseidon

Medusa greek mythology was described as a beautiful mortal woman before she was cursed. She was said to have flowing golden or auburn hair, which was considered her most striking feature. Her beauty was so captivating that she caught the attention of various suitors and even garnered the interest of the sea god Poseidon.

However, after an encounter with Poseidon in the temple of Athena, Medusa's fate took a tragic turn. According to the myth, Poseidon raped Medusa within the temple of Athena, defiling the sacred space. As a result of this violation, Athena punished Medusa rather than Poseidon. The enraged Athena cursed Medusa, transforming her appearance into a grotesque form to punish her. Her beautiful hair was turned into serpents, her eyes became glowing and petrifying, and her once attractive countenance became monstrous.

It's important to note that descriptions of Medusa's appearance can vary in different interpretations and artistic depictions. Artists and storytellers throughout history have depicted Medusa in various ways, emphasizing different aspects of her monstrous transformation. However, the common thread in the myth is that she was initially a beautiful woman who was tragically transformed into a horrifying creature as a result of a curse bestowed upon her.

Perseus and Medusa

The story of Medusa and Perseus is a well-known tale in Greek mythology. It involves the hero Perseus and his quest to slay the monstrous Gorgon Medusa.

Perseus was the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Danaë, a mortal woman. When Perseus was a baby, an oracle prophesied that he would one day kill his grandfather, Acrisius. To prevent this, Acrisius locked Danaë and Perseus in a chest and cast them into the sea. They were eventually rescued by a fisherman and brought to the island of Seriphos, where they lived.

As Perseus grew older, King Polydectes of Seriphos became infatuated with Danaë and desired to marry her. Perseus, reluctant to see his mother wedded to the king, accepted a dangerous task proposed by Polydectes. The king requested the head of Medusa, the only mortal Gorgon, as a gift from Perseus.

The Gorgons, Medusa included, were monstrous creatures with snakes for hair and the power to turn people to stone with their gaze. Medusa, in particular, possessed this petrifying ability. To aid him in his quest, Perseus received various gifts from the gods, including a reflective shield from Athena, winged sandals from Hermes, and a helm of invisibility from Hades.

Using these divine gifts, Perseus embarked on his journey. He managed to find the three Gorgons, including Medusa, in their lair. Avoiding direct eye contact with Medusa, he used his shield as a mirror to observe her without turning to stone. With a swift strike, Perseus beheaded Medusa while she slept. The winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor, both born from Medusa's blood, emerged from her severed neck.

On his way back, Perseus encountered various adventures, including rescuing Andromeda, a princess, from a sea monster. Eventually, he returned to Seriphos and used Medusa's head as a weapon against his enemies. In one incident, he petrified King Polydectes and his court, avenging his mother's mistreatment.

Perseus later reunited with his grandfather, Acrisius. However, the prophecy came true when Perseus accidentally killed Acrisius during a discus-throwing contest. As a result, Perseus fulfilled the prophecy, but his heroic feats brought him renown and established his place in Greek mythology.

The myth of Medusa and Perseus is often seen as a tale of heroism, triumph over monstrous forces, and the fulfillment of prophecies. It showcases Perseus' courage, resourcefulness, and divine assistance in his quest to slay Medusa and the subsequent events that unfolded as a result.

Medusa's Children

According to Greek mythology, Medusa goddess did have offspring. After Perseus, the hero who beheaded Medusa, two creatures emerged from her severed neck: Pegasus and Chrysaor.

Pegasus was a winged horse known for his incredible speed and association with poetry and inspiration. He became a famous mythological figure in his own right and was tamed by the hero Bellerophon, who rode him on various adventures.

Chrysaor, on the other hand, was a giant or a warrior with a golden sword. His name translates to "Golden Blade." Chrysaor is not as widely known or featured in mythology as Pegasus, but he is often mentioned as the sibling of the winged horse.

It's important to note that Medusa's offspring were not conceived in the traditional sense but were born from her blood or the remnants of her body after her death. They played significant roles in subsequent mythological narratives and were seen as the legacy of Medusa, carrying aspects of her power and essence.

Was Medusa Immortal?

In Greek mythology, Medusa was not immortal. Like many other figures in Greek mythology, she was a mortal who possessed certain abilities and encountered divine beings. Medusa was originally a beautiful mortal woman, but due to a curse placed upon her by the goddess Athena, she was transformed into a monstrous creature with snakes for hair and the ability to turn people to stone with her gaze.

Medusa's immortality, or lack thereof, can be interpreted differently depending on the version of the myth. Some sources suggest that she was mortal and eventually slain by the hero Perseus, who used a mirror-like shield to avoid looking directly at her and beheaded her while she slept. In this interpretation, Medusa's death implies that she was not immortal.

However, other versions of the myth propose that Medusa, along with her sisters, possessed a degree of immortality. They were depicted as beings who could not be killed conventionally due to their monstrous nature. Their immortality was tied to their monstrous form, which persisted despite any injuries inflicted upon them. It was only through a specific act, such as Perseus using his reflective shield to decapitate her, that Medusa could be defeated.

Overall, the concept of Medusa's immortality can vary depending on the interpretation of the myth. In some versions, she was mortal and eventually slain, while in others, she possessed a form of immortality that required a specific method of defeating her.

Is Medusa a Goddess?

Medusa is not a goddess; she's a figure from Greek mythology. She was originally a beautiful woman turned into a Gorgon with snakes for hair. Medusa is often associated with her petrifying gaze.

What Does Medusa Symbolize?

The Medusa meaning is multifaceted and can be interpreted through various lenses, including mythology, psychology, and symbolism. Here are a few key aspects of the meaning associated with Medusa:

What Does Medusa Represent?

Transformation and Metamorphosis: Medusa's story revolves around a significant transformation. She was once a beautiful mortal woman who, due to a curse, became a grotesque figure with snakes for hair and the power to turn people to stone. Her tale represents the concept of metamorphosis, both physically and symbolically. It reflects the potential for profound changes in one's life and the transformative power that lies within.

Complexity and Duality: Medusa embodies the complexity and duality of human nature. On one hand, she is depicted as a monstrous figure capable of petrifying others. On the other hand, she was once a beautiful woman who faced unjust punishment. This duality reflects the intricate nature of humanity, showcasing how individuals can possess both light and dark aspects within themselves.

Reflection and Self-Exploration: Medusa's gaze, which turned people to stone, can be seen as a metaphor for self-reflection and the consequences of avoiding or denying one's own truth. Medusa prompts individuals to confront their inner fears, desires, and shadows. Her story encourages deep introspection, acceptance, and the integration of all aspects of oneself.

Archetypal and Symbolic Representation: Medusa has become an archetypal figure, representing various themes and symbols. These include femininity, power dynamics, wisdom, protection, transformation, and the embodiment of the wild and untamed forces of nature. Her symbolism transcends time and continues to resonate with individuals seeking to understand and express different facets of the human experience.

Medusa in Modern Witchcraft

Medusa's role in witchcraft varies depending on the specific tradition or belief system being explored. It's important to note that Medusa herself is a figure from Greek mythology, while witchcraft encompasses a wide range of practices and beliefs that can be found in different cultures throughout history.

In some modern forms of witchcraft, Medusa energy may be invoked or revered as a symbol of feminine power, transformation, and protection. She is seen as a representation of the wild, untamed aspects of nature and the feminine divine. Some witches may draw inspiration from her story to connect with their own inner strength, resilience, and the ability to face challenges.

In certain magical practices, Medusa's image or symbolism might be incorporated into rituals, spells, or charms for specific purposes. For example, her serpentine hair might be seen as a potent symbol for the awakening of kundalini energy or as a representation of the transformative power of the serpent archetype.

It's essential to recognize that witchcraft is a diverse and multifaceted spiritual path, and individuals or groups within witchcraft traditions may interpret and incorporate Medusa's symbolism differently. Medusa's role in witchcraft is often subjective and open to personal interpretation, reflecting the practitioner's unique beliefs and intentions.

27 notes

·

View notes