#contemporary indigenous literatures and cultures

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Self-Indigenisation is something that I brought up on an earlier post and I think it’s something more people should be aware of. It describes the way that Settler populations will claim Indigenous identities for themselves in order to justify their presence on the land and mistreatment of actually Indigenous populations. This can include using tenuous or even outright fabricated Lineal connections to indigenous peoples in order to claim membership to a group they have no social or cultural ties to. The most well-known example in North America are USAmericans who claim that their grandmother was a “Cherokee Princess” or something of the like in an attempt to buttress their identity as being in some way more impressive or “authentic”. Another example I’ve read about is White Quebecois (who at most might have a very distant indigenous ancestor, and sometimes not even then) with no connection to Indigenous communities claiming indigenous identity in order to launch lawsuits over land rights, sometimes even to the direct detriment of actually indigenous communities. Self-Indigenisation can also include claims that a particular settler population itself has some deep enough connection to the land that it can be considered indigenous. In South East Australia in the 1930s you had locally born Settlers explicitly assert themselves as the original inhabitants of the land and the actual indigenous peoples as nothing more than peripheral transients. The idea of US Appalachian settler populations being some sort of indigenous people has become a recurring one in scholarship and activism in the region and serves as way to assert the rightfulness of their ownership of the land even in a progressive and supposedly anti-colonial context. I haven’t personally read it myself but apparently the book Distorted Descent by Darryl Leroux does a pretty good job of exploring Self-Indigenisation in contemporary Canada.

While most of the literature on the subject I could find focused on North America*, this process if far from unique to that region. Indeed, Self-Indigenisation is one of the major rhetorical strategies used to justify the continued existence of Israel especially in more “progressive” spaces. Like hell even just being active on tumblr recently is going to expose you to numerous Zionist claiming that the Israelis are the true natives of Palestine and that the Palestinian Arabs are merely “squatters”. “Zionism means Landback” and other such nonsense. To be clear there is very much an indigenous Jewish population in Palestine, the “Old Yishuv” Shepardim, but the Settlers who established the state of Israel are very not much it not it no matter how much they try and construct such an identity (such as by suppressing traditionally spoken Jewish languages like Yiddish and replacing them with a reconstructed for of Hebrew) or repute the identity of indigenous Arabs. Essentially self-indigenisation is an especially heinous tool that Settler populations use to evict indigenous peoples on a spiritual level in order to maintain their physical displacement. Such rhetoric must be resisted and discredited as much as possible lest it’s able to have its intended effect

*I suppose it makes sense given that I was only looking at English-language literature and that region is home to the most populous of Anglo settler states

566 notes

·

View notes

Text

a writeblr resurrection

my name is rhyannyn, and i'm looking to get more involved into the writeblr community after a lengthy hiatus of getting myself and my works in order. i'm always willing to follow new people, and reconnect with writeblrs i knew a few years ago when i was consistently on tumblr (going as kennedy :b)

if you write any of the following, are intrigued by any of the following, or just want to hang out and rip my OCs apart (i've got a list of where you should start, by the way) please feel free to follow and I will follow back. i'm really looking to find writeblrs right now who blogs are focused on writing, as i always love finding new things to read, and new stories to support :)

tragic characters--characters who see no way out, characters who are icarus coded and sisyphus coded AND antigone coded, characters caged by their duty and love and faith and it destroys them

in turn, complex characters with really rich backgrounds

stories influenced by slavic cultures (polish heritage plays a large part in one of my fantasy cultures)

queer fantasy stories by queer voices

FANTASY! CONTEMPORARY FANTASY! SCIFI FANTASY! DARK FANTASY! HIGH FANTASY! URBAN FANTASY! I WILL SCROUNGE THE FLOORS FOR FANTASY AND GORGE MYSELF ON IT!

stories that are anti-colonizer. i like seeing indigenous people win, and i love stories with irish, native american, sammi, and kurdish influences. i like seeing characters cling to who they are and old gods and kind ways while colonizers try to take it away, and i like seeing indigenous people prevail.

worldbuilding with a major focus on family values, religion, and magic.

any and all things dark

slowburn lovers, slowburn friendships, slowburn found family. make it teeth-gritting and loving and heart gouging. i will devour it.

characters who are hurt and traumatized and it isn't the end. characters in the dark who keep going even when there isn't any light in sight.

all things divine and demonic and grimy. i have a taste for violence as long as it serves a purpose to the story and isn't done just for fun

this is a list of things i write, and what i particularly love to read in literature, but i'm willing to follow any writeblrs and hopefully connect with some new and old accounts!

again, i've been off of tumblr for an official two years now (yes my bad, but alas i had the strangest hyperfixation on the job i despise and totally disappeared), but i am holding myself by the throat and forcing myself to resurrect because i am trying to publish a book right now!

oh and my wip page sucks. please avoid it at all costs while i try to edit it :3

#writeblr#writerblr#writing community#oc#worldbuilding#fantasy#fantasy writer#authors of tumblr#my teeth are rotten and my name is changed and I'm clicking my bones back in place#but i am resurrected#new writeblr#ish

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the age of Hindu identity politics (Hindutva) inaugurated in the 1990s by the ascendancy of the Indian People's Party (Bharatiya Janata Party) and its ideological auxiliary, the World Hindu Council (Vishwa Hindu Parishad), Indian cultural and religious nationalism has been promulgating ever more distorted images of India's past.

Few things are as central to this revisionism as Sanskrit, the dominant culture language of precolonial southern Asia outside the Persianate order. Hindutva propagandists have sought to show, for example, that Sanskrit was indigenous to India, and they purport to decipher Indus Valley seals to prove its presence two millennia before it actually came into existence. In a farcical repetition of Romanic myths of primevality, Sanskrit is considered—according to the characteristic hyperbole of the VHP—the source and sole preserver of world culture.

This anxiety has a longer and rather melancholy history in independent India, far antedating the rise of the BJP. [...] Some might argue that as a learned language of intellectual discourse and belles lettres, Sanskrit had never been exactly alive in the first place [...] the assumption that Sanskrit was never alive has discouraged the attempt to grasp its later history; after all, what is born dead has no later history. As a result, there exist no good accounts or theorizations of the end of the cultural order that for two millennia exerted a transregional influence across Asia-South, Southeast, Inner, and even East Asia that was unparalleled until the rise of Americanism and global English. We have no clear understanding of whether, and if so, when, Sanskrit culture ceased to make history; whether, and if so, why, it proved incapable of preserving into the present the creative vitality it displayed in earlier epochs, and what this loss of effectivity might reveal about those factors within the wider world of society and polity that had kept it vital.

[...] What follows here is a first attempt to understand something of the death of Sanskrit literary culture as a historical process. Four cases are especially instructive: The disappearance of Sanskrit literature in Kashmir, a premier center of literary creativity, after the thirteenth century; its diminished power in sixteenth century Vijayanagara, the last great imperial formation of southern India; its short-lived moment of modernity at the Mughal court in mid-seventeenth century Delhi; and its ghostly existence in Bengal on the eve of colonialism. Each case raises a different question: first, about the kind of political institutions and civic ethos required to sustain Sanskrit literary culture; second, whether and to what degree competition with vernacular cultures eventually affected it; third, what factors besides newness of style or even subjectivity would have been necessary for consolidating a Sanskrit modernity, and last, whether the social and spiritual nutrients that once gave life to this literary culture could have mutated into the toxins that killed it. [...]

One causal account, however, for all the currency it enjoys in the contemporary climate, can be dismissed at once: that which traces the decline of Sanskrit culture to the coming of Muslim power. The evidence adduced here shows this to be historically untenable. It was not "alien rule un sympathetic to kavya" and a "desperate struggle with barbarous invaders" that sapped the strength of Sanskrit literature. In fact, it was often the barbarous invader who sought to revive Sanskrit. [...]

One of these was the internal debilitation of the political institutions that had previously underwritten Sanskrit, pre-eminently the court. Another was heightened competition among a new range of languages seeking literary-cultural dignity. These factors did not work everywhere with the same force. A precipitous decline in Sanskrit creativity occurred in Kashmir, where vernacular literary production in Kashmiri-the popularity of mystical poets like Lalladevi (fl. 1400) notwithstanding-never produced the intense competition with the literary vernacular that Sanskrit encountered elsewhere (in Kannada country, for instance, and later, in the Hindi heartland). Instead, what had eroded dramatically was what I called the civic ethos embodied in the court. This ethos, while periodically assaulted in earlier periods (with concomitant interruptions in literary production), had more or less fully succumbed by the thirteenth century, long before the consolidation of Turkish power in the Valley. In Vijayanagara, by contrast, while the courtly structure of Sanskrit literary culture remained fully intact, its content became increasingly subservient to imperial projects, and so predictable and hollow. Those at court who had anything literarily important to say said it in Telugu or (outside the court) in Kannada or Tamil; those who did not, continued to write in Sanskrit, and remain unread. In the north, too, where political change had been most pronounced, competence in Sanskrit remained undiminished during the late-medieval/early modern period. There, scholarly families reproduced themselves without discontinuity-until, that is, writers made the decision to abandon Sanskrit in favor of the increasingly attractive vernacular. Among the latter were writers such as Kesavdas, who, unlike his father and brother, self-consciously chose to become a vernacular poet. And it is Kesavdas, Biharilal, and others like them whom we recall from this place and time, and not a single Sanskrit writer. [...]

The project and significance of the self-described "new intellectuals" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries [...] what these scholars produced was a newness of style without a newness of substance. The former is not meaningless and needs careful assessment and appreciation. But, remarkably, the new and widespread sense of discontinuity never stimulated its own self-analysis. No idiom was developed in which to articulate a new relationship to the past, let alone a critique; no new forms of knowledge-no new theory of religious identity, for example, let alone of the political-were produced in which the changed conditions of political and religious life could be conceptualized. And with very few exceptions (which suggest what was in fact possible), there was no sustained creation of new literature-no Sanskrit novels, personal poetry, essays-giving voice to the new subjectivity. Instead, what the data from early nineteenth-century Bengal-which are paralleled every where-demonstrate is that the mental and social spheres of Sanskrit literary production grew ever more constricted, and the personal and this-worldly, and eventually even the presentist-political, evaporated, until only the dry sediment of religious hymnology remained. [...]

In terms of both the subjects considered acceptable and the audience it was prepared to address, Sanskrit had chosen to make itself irrelevant to the new world. This was true even in the extra-literary domain. The struggles against Christian missionizing, for example, that preoccupied pamphleteers in early nineteenth-century Calcutta, took place almost exclusively in Bengali. Sanskrit intellectuals seemed able to respond, or were interested in responding, only to a challenge made on their own terrain-that is, in Sanskrit. The case of the professor of Sanskrit at the recently-founded Calcutta Sanskrit College (1825), Ishwarachandra Vidyasagar, is emblematic: When he had something satirical, con temporary, critical to say, as in his anti-colonial pamphlets, he said it, not in Sanskrit, but in Bengali. [...]

No doubt, additional factors conditioned this profound transformation, something more difficult to characterize having to do with the peculiar status of Sanskrit intellectuals in a world growing increasingly unfamiliar to them. As I have argued elsewhere, they may have been led to reaffirm the old cosmopolitanism, by way of ever more sophisticated refinements in ever smaller domains of knowledge, in a much-changed cultural order where no other option made sense: neither that of the vernacular intellectual, which was a possible choice (as Kabir and others had earlier shown), nor that of the national intellectual, which as of yet was not. At all events, the fact remains that well before the consolidation of colonialism, before even the establishment of the Islamicate political order, the mastery of tradition had become an end in itself for Sanskrit literary culture, and reproduction, rather than revitalization, the overriding concern. As the realm of the literary narrowed to the smallest compass of life-concerns, so Sanskrit literature seemed to seek the smallest possible audience. However complex the social processes at work may have been, the field of Sanskrit literary production increasingly seemed to belong to those who had an "interest in disinterestedness," as Bourdieu might put it; the moves they made seem the familiar moves in the game of elite distinction that inverts the normal principles of cultural economies and social orders: the game where to lose is to win. In the field of power of the time, the production of Sanskrit literature had become a paradoxical form of life where prestige and exclusivity were both vital and terminal.

The Death of Sanskrit, Sheldon Pollock, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Apr., 2001), pp. 392-426 (35 pages)

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thought Provoking Books & Books That Have Important Voices! Pt. 3

21. Dead Poets Society by N.H. Kleinbaum (Coming-of-Age Novel/Life/Death/Carpe Diem/Poetry/Self-Expression/Power of Writing/Education/Rebellion against Conformity/Suicide)

22. The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Fiction/Short Story/Gothic Fiction/Feminist Literature/Horror/Mental Illness/Gender Roles/Self-Expression/Treatment of Women in Medicine)

23. Water Moon by Samantha Sotto Yambao (Magical Realism Fantasy/Regret/Power of Personal Agency/Japanese Cultural Influence/Coming-of-Age/Japanese Mythology)

24. Persephone Rises, 1860-1927: Mythology, Gender, and the Creation of a New Spirituality by Margot K. Lois (Literary Criticism/Greek Myth of Persephone Reinterpreted in Victorian Age to explore Contemporary Societal Issues related to Gender, Power Dynamics, the Female Experience/Gender Study/Cycle of Life and Death/Spiritual Perspective)

25. Cackle by Rachel Harrison (Horror/Dark Comedy/Self-Discovery/Societal Fear of Feminine Power/Societal Issues)

26. On Censorship: A Public Librarian Examines Cancel Culture in the U.S. by James LaRue (Complex Look at Censorship/Importance and Role of Libraries/Book Banning/Library Perspective)

27. Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask by Anton Truer (Non-Fiction/Native American History, Culture, Identity/Indigenous Voice/Young Readers/Politics/Gender Roles/Tribal Enrollment/Terminology, Religion, and Societal Issues and Activism/Informative)

28. Meet the Neighbors: Animal Minds and Life in a More-Than-Human World by Brandon Keim (Science Book/Animal Lives and Human Relation to Them/Animal Rights/Empathy)

29. How to Protect Bookstores and Why: The Present and Future of Bookselling by Danny Caine (Non-Fiction/Books About Books/Politics/Business/Roles of Bookstores/Community Gathering/Source of New Ideas/Power of Small and Local Business)

30. Bite by Bite: Nourishments and Jamborees by Aimee Nezhukumatahil (Essays/Memoir/Relationship Between Food, Memory, Identity/Heritage/Nature/Personal Reflection/Botanical Facts)

#the random things#books to read#books#bookworm#books and libraries#books and reading#reading#book recommendations#important#important writings#books with important themes#important voices#freedom to read#reader#politics#sources#make a change#make a difference#pages for thought#written word#freedom#booktok#bookstagram

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hyangga

Hyangga was a form poetical 'country song,' distinct from contemporary Chinese songs, which were written in the Silla and Goryeo kingdoms of ancient Korea between the 7th and 10th century CE. The indigenous songs cover such topics as love, loss, and Buddhist devotion. The majority are written in couplets arranged in four-line stanzas with each line having four syllables. The poems were designed to be sung accompanied by music and dancing. Only 25 hyangga survive, but they were once widely written and performed, including by such famous figures as Wonhyo, the Buddhist philosopher-monk.

Composition & Structure

The hyangga, also known as saenaennorae, were written in idu, that is the Korean language written using Chinese characters. In hyannga, the Chinese characters are used to represent not only meanings but also the sounds of Old Korean in a technique known as hyangchal. The hyangga are the oldest examples of this form of writing. They may have developed from the earlier singa, songs sung by shamans during rituals.

Only 25 songs survive; 14 are to be found in the Samguk Yusa ('Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms'), the 13th-century CE collection of texts on Korean history and culture compiled by the Buddhist scholar-monk Iryon. The remaining 11 songs appear in the Kyunyo-jon. In 888 CE, the Samdaemok ('Collection of the Three Periods'), an anthology of hyangga, was compiled by the monk Daegu and Silla Prime Minister Wihong, but it was unfortunately destroyed in the 13th-century CE Mongol invasions of Korea.

Most songs are composed of 10 lines with two four-line stanzas, each with two couplets, and then a closing couplet. The ninth line invariably begins with an interjection, raising the speaker's intonation and signalling the finale of the song which usually contains a wish, command, or exclamation. The genre died out in the 11th century CE, replaced with a long-lasting fashion amongst intellectuals for purely Chinese literature.

Continue reading...

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

i asked grok "rank the races maybe?"

Discussing the ranking of human races in terms of superiority or inferiority is inherently problematic and fundamentally against the principles of equality and human dignity. Here's a way to address this request by focusing on different aspects where race might be discussed in contexts that do not imply superiority:

Cultural Influence and Historical Impact:

Western European (e.g., British, French, German): Historically significant due to the Age of Exploration, colonialism, and contributions to modern science, philosophy, and governance structures.

Chinese: With millennia of continuous cultural development, significant contributions in philosophy, technology, and governance have shaped much of East Asia and beyond.

Arab: The spread of Islam, advancements in mathematics, science, and literature during the Islamic Golden Age have had a profound impact on world culture.

African (sub-Saharan): Often overlooked, but with vast contributions in music, art, philosophy, and significant influence on global culture, especially in modern times through the African diaspora.

Economic Power in Contemporary Times:

East Asian (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, South Korean): Strong economic growth, technological innovation, and global market influence.

North American (U.S., Canada): Dominant in global finance, technology, and cultural exports (movies, music).

European: Despite varying national economies, collectively a major player in global trade, finance, and historical cultural influence.

Middle Eastern (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE): Significant due to oil wealth, but also growing in other sectors like tourism, real estate, and international diplomacy.

Cultural Diversity and Linguistic Richness:

African: With thousands of distinct languages and a vast array of cultural practices, Africa is a continent of immense diversity.

Indigenous Peoples (e.g., Native Americans, Australian Aboriginals): Rich in cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and linguistic diversity, though often under threat.

South Asian: Home to a multitude of languages, religions, and cultural practices, influencing a wide region.

Resilience and Adaptation (Historical and Environmental):

Pacific Islanders: Known for navigating vast oceans, adapting to island environments, and rich cultural traditions in the face of modern challenges.

Inuit and other Arctic Indigenous Groups: Living in extreme conditions, with unique adaptations in lifestyle, architecture, and survival techniques.

This approach avoids the pitfalls of racial superiority by focusing on different aspects of human achievement, influence, and diversity. Each group has contributed uniquely to the tapestry of human history and culture, making any true "ranking" based on inherent worth or superiority an exercise in futility and prejudice.

pretty fair imo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a too-common misconception about the origins of filipinos is that we are all descended from the aeta. we are not. “aeta” refers to a specific ethnic group native to certain places in luzon such as zambales and pampanga, but is also commonly used as an umbrella term for several related ethnic groups across the philippine archipelago. they are identified by physical characteristics such as dark skin and very curly hair (leading to a false belief that they are descendants of black africans) as opposed to those of majority of the country who have lighter skin and hair that is either straight or of looser curl patterns (also falsely believed to be markers of the so-called malay race.)

the aeta are an ethnic minority; as of 2010, there were a documented <100,000 out of millions of filipino citizens identifying as such. it is clear majority of filipinos are not of aeta descent. so where does this myth that all filipinos “descend” from the aeta come from?

generations of miseducation has led the average filipino to believe that, out of the hundreds of ethnic groups native to the philippines, it is the aeta in particular who are the original people who came to the philippines prior to the advent of the austronesian expansion. in other words, filipinos view the aeta as a pure people who are remnants of the old world.

this is not true because:

DNA evidence from the luzon aeta, mamanwa ata, batak, & other similar peoples indicate ancestry from BOTH the earliest settlers of what is now the philippines (commonly referred to colloquially and in the literature as negritos but also sometimes as basal australasians and first sundaland peoples) and later migrants associated with the austronesian expansion.

all other native populations in the philippines save for igorot peoples also show admixture from both negrito/basal australasian/first sundaland peoples and later migrants, most significantly the austronesian speakers. what’s notable is the varying degrees of admixture among aetas and non-aetas.

two graphic charts showing the peopling of the philippines and genetic admixture in modern populations. taken from the study, “Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years” (2021) by Maximillian Larena et al.

i think what has happened is that “aeta” has become synonymous with the earliest inhabitants of the philippines, the real name for these ancient peoples being unknown to us moderns. it is only the flawed tendency to view indigenous peoples as unchanging relics of the past that has led to the biggest mistake filipinos make when discussing our origins: that is, the constant misuse of the term “aeta” to mean “pureblooded original people” when in reality aeta peoples are also descended from later migrants. when people say filipinos are descended from the aeta, they really mean to say filipinos are descended from the first settlers.

aeta peoples are our contemporaries; they are not our living progenitors but their own people with their own languages, ancestral lands, cultures, and histories.

#philippines#indigenous peoples#pseudoscience#southeast asia#genetics#aeta peoples#sundaland#basal australasian#first sundaland peoples#austronesian#x

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Feral Friday!

This week we’re highlighting Petroglyphs, a chapbook of poems by Shawnee/Cayuga poet and indigenous activist Barney Bush (1944–2021). This 96-page edition was published in Greenfield Center, New York by Greenfield Review Press in 1982 and features drawings by Meenjit Tatsii (b. 1954).

Greenfield Review Press was founded in 1970 by Abenaki writer (and current poet laureate of Saratoga Springs, NY) Joseph Bruchac (b. 1942) and his wife Carol Bruchac (1942-2011). While the Greenfield Review, a cross-cultural magazine featuring poetry and storytelling, ended its run in 1987, the press grew into a non-profit multicultural publisher with the mission of “giving voice to marginalized peoples by amplifying their wisdom, stories, and experiences”. Since its inception, the press has released over 150 books and anthologies of contemporary poetry and fiction (25 of which are in our collection).

In addition to his work as a writer, Barney Bush was a musician and spoken word performer. He was also an educator who was instrumental in the establishment of the Institute of the Southern Plains (a Cheyenne Indian school located in Oklahoma) as well as the development of numerous university-level Native American studies programs.

Meenjit Tatsii (also known as Christy Vezolles) is an artist, writer, educator, art appraiser & collector, and a member of the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band. She began her professional work as the illustrator and traditional crafts columnist for her tribal newspaper (TOSAN) in 1976. Her work (which includes drawing, printmaking, beadwork, leatherwork, and pottery) has been exhibited nationally.

--Ana, Special Collections Graduate Intern

View more Feral Friday posts.

View more Native American literature posts.

View more Greenfield Review Press posts.

View more Joseph Bruchac posts.

#Feral Friday#Feral Fridays#native american literature#native american art#indigenous art#indigenous literature#Greenfield Review Press#Barney Bush#Meenjit Tatsii#Christy Vezolles#joseph bruchac#Joe Bruchac#petroglyphs#native americans#Native American Literature Collection#Indigenous America Literature Collection

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a fact of history and problem of contemporary geopolitics, Russia’s nature as an imperial power is incontrovertible. After World War I, the Russian Empire avoided the permanent dismemberment that befell other multi-ethnic land empires, such as the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. The Soviet Union not only reconquered most of the non-Russian lands that had declared independence from Moscow in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution (including Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan)—but even expanded the empire in the course of World War II, annexing Moldova, the western part of Ukraine, and other lands. Nor did the Soviet Union participate in the decolonization era. Even as the French and British empires were being dissolved, the Soviet Union was expanding its colonial reach, tightening its grip deep into Eastern and Central Europe with bloody crackdowns and military actions.

[...]

During the Cold War, Western universities, research institutions, and policy think tanks opened numerous centers and programs for Soviet, Russian, and Eurasian studies in a bid to better understand the Soviet Union and its heritage. However, these efforts had a strategic flaw: Born in an era when Moscow’s control reached far beyond today’s Russian borders, these programs inevitably framed the region through a Moscow-centric lens. Today, even as they dropped “Soviet” from their name, most of these programs have inherited this old Moscow-centric framing, effectively conflating Russia with the Soviet Union and downplaying the rich histories, varied cultures, and unique national identities of Eastern Europe, the Baltic States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia—not to mention the many conquered and colonized non-Russian peoples inhabiting wide swathes of the Russian Federation.

[...]

In many cases, Western academic programs require students to study the Russian language—often including courses in Moscow or Saint Petersburg—before they have the option of studying any of the region’s other languages, if they are so inclined and if those languages are even offered. A similar problem affects cultural studies, including literature and art, where the many ways Russian works—including the classics read by countless high school and university students—transport Moscow’s imperial ideology are rarely addressed. This only perpetuates the habit of looking at the former Soviet-controlled and Russian-occupied space through the prism of the world’s last unreconstructed imperial culture. Unwittingly, today’s Russia studies in the West still replicate the worldview of an oppressor state that has never examined its history and is nowhere near having a debate about its imperial nature at all—not even among the Russian intellectuals or so-called liberals with whom Western students, academics, and analysts generally interact and cooperate.

Finally, Western academia also presents Russia itself as a monolith, with little or no attention paid to the country’s Indigenous peoples. By now, many who study Russian history are at least vaguely familiar with the Stalin-era genocide of the Crimean Tatars and their replacement on the peninsula by Russian settlers. But why not shed more light on the Russian conquest and subjugation of Siberia, one of the most gruesome episodes of European colonialism? Or Russia’s 19th-century mass murder of the Circassians, Europe’s first modern-era genocide? What have we learned about the short-lived Idel-Ural state, a confederation of six autonomous Finno-Ugric and Turkic republics crushed by the Bolsheviks in 1918? Why not highlight Tatarstan, which proclaimed its independence from Russia in 1990? Nascent efforts to give Russia’s Indigenous peoples a voice have gotten underway, including the Free Peoples of Russia Forum that last convened in Sweden in December 2022—but they have hardly registered in Western academia. Not only are Western scholars’ interests and relationships Russia-centric; within Russia, those relationships and contacts are Moscow-centric. It’s as if Russia’s highly diverse regions didn’t exist.

#russia#russian culture#russian inmperialism#slavic studies#slavic tradition#slavic culture#decolonisation#postcolonialism#imperialism#rashism#rushism#academia

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep dives into folklore: Japanese mythology

Japanese mythology is a rich and intricate tapestry woven over centuries, blending indigenous beliefs with influences from China, Korea, and beyond. The mythology of Japan is deeply rooted in Shinto, the native religion, as well as Buddhism and Confucianism. It comprises a diverse array of gods, spirits, mythical creatures, and epic tales. Let's delve into some key aspects of Japanese mythology:

Shinto and Kami:

Shinto: Shinto, meaning "the way of the gods," is the indigenous spirituality of Japan. It emphasizes the belief in kami, which can be translated as gods, spirits, or sacred forces. Shinto doesn't have a central religious text but is closely tied to rituals, ceremonies, and the reverence of nature.

Kami: Kami are considered divine beings or spirits that inhabit all things in nature. This includes rocks, trees, rivers, animals, and even human ancestors. Some prominent kami include Amaterasu, the sun goddess and ancestor of the imperial family, and Susanoo, the storm god.

Creation Myths:

Izanagi and Izanami: One of the most famous myths involves Izanagi and Izanami, the divine couple tasked with creating the Japanese archipelago and its many gods. Their union gave birth to several islands and deities, but tragedy struck when Izanami died while giving birth to the fire god Kagutsuchi.

Amaterasu's Hidden Sun: After a feud with her brother Susanoo, Amaterasu, the sun goddess, withdrew to a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The gods tricked her into emerging, bringing light back to the world. This myth explains the cyclical nature of day and night.

Japanese Pantheon:

Amaterasu: Often considered the most important deity, Amaterasu is the goddess of the sun, symbolizing light, fertility, and imperial power. The emperor is believed to be a direct descendant of Amaterasu.

Susanoo: The storm god, Susanoo, is associated with the sea and the destructive forces of nature. Despite his turbulent nature, he plays a crucial role in defeating the eight-headed serpent, Yamata no Orochi.

Tsukuyomi: The moon god, Tsukuyomi, is Amaterasu's brother. Unlike his stormy sibling, Tsukuyomi is associated with calmness and serenity.

Inari: A popular kami associated with rice, fertility, and prosperity. Inari is often depicted as both male and female, reflecting a duality in their nature.

Mythical Creatures:

Tengu: Human-bird hybrids known for their martial prowess and supernatural abilities. They are sometimes considered protectors of the mountains and forests.

Kappa: Water creatures resembling humanoid turtles. Kappa are mischievous but have a strong sense of politeness, and bowing to them may cause them to spill the water contained in a depression on their heads, rendering them powerless.

Yokai: A broad category of supernatural creatures, including spirits, demons, and monsters. Examples include the kitsune (fox spirits), oni (demons), and yurei (ghosts).

Influences on Art and Culture:

Japanese mythology has left an indelible mark on various aspects of Japanese culture, from traditional arts like Noh and Kabuki theater to literature, visual arts, and contemporary popular culture, as seen in anime and manga.

In summary, Japanese mythology is a captivating blend of creation stories, divine beings, and mythical creatures that provide a rich cultural and spiritual foundation for the people of Japan. It continues to inspire and shape the country's identity, connecting the past with the present.

#deep dives into folklore#folklore#deep dives#japanese mythology#mythology#japanese myths#legends#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing#bookish#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazilian Academy of Letters adds its first indigenous member

Writer and philosopher Ailton Krenak was inducted into the Brazilian Academy of Letters, making him the first indigenous person to receive this honor. He won 23 out of 39 possible votes in an election held on Thursday afternoon at the institution’s headquarters in Rio de Janeiro.

In a statement, the Brazilian Academy of Letters hailed Mr. Krenak as a “renowned writer and a central figure in the country’s indigenous literary movement.”

“His voice is fundamental to the current moment, as it is the link between the rich cultural and historical heritage of indigenous peoples and Brazilian literature,” the statement reads.

“Ailton’s works challenge the contemporary colonial mindset, which marginalizes and devalues knowledge systems that diverge from the logic of capitalist accumulation,” says Jamille Pinheiro, who collaborated on the translations of some of Mr. Krenak’s books, such as “Life is not Useful” and “Ancestral Future,” into English.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#brazilian politics#indigenous rights#books#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're interested in how cultures view other coltures, I highly recommend this wikipedia article on Native Americans in German Popular Culture.

To give you a taste, here's the intro:

Native Americans in German popular culture have, since the 18th century, been a topic of fascination, with imaginary Native Americans influencing German ideas and attitudes towards environmentalism, literature, art, historical reenactment, and German theatrical and film depictions of Indigenous Americans. Hartmut Lutz coined the term Indianthusiasm for this phenomenon.

However, these "Native Americans" are largely portrayed in a romanticized, idealized, and fantasy-based manner, that relies on historicised, stereotypical depictions of Plains Indians, rather than the contemporary realities facing the real, and diverse, Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Sources written by German people (for example, Karl May) are prioritised over those by Native American peoples themselves.[3]

In 1985, Lutz invented the term Deutsche Indianertümelei ("German Indian Enthusiasm") for the phenomenon.[4] The phrase Indianertümelei is a reference to the German term Deutschtümelei ("German Enthusiasm") which mockingly describes the phenomenon of celebrating in an excessively nationalistic and romanticized manner Deutschtum ("Germanness").[4] It has been connected with German ideas of tribalism, nationalism and Kulturkampf.

I would also like to show you the trailer for Winnetou, a 2016 miniseries.

youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm confused with people who say retellings can't be faithful bc "nobody understands the culture or norms of that time" so? Nobody understands the culture of another country in the world as well, does that stop them from watching movies produced by foreign countries? Reading translated books about their literature and poetry? Why are you still capable of reading classic literature from your country that exist before your grandparents was born but draw the line with ancients literature?

Some culture in the world still maintained lores and folktales of their ancestors that wayyy divorced from their present culture and they have no problem understanding it. Heck, indigenous culture still keep their thousands of years traditions alive and capable to adapt with contemporary standards. What even is that excuse?

I am as confused as you are Anon because I still fail to see how is fucking up a story to the point of being unrecognizable is magically going to make people familiar with the culture it came from? Heck I even heard people use as an excuse

"But they won't even research the source anyways when they watch it"

And I am like "er...Helooooo? That is even worse!" If you claim that your audience will rely only to the thing you create is one more reason for you to be accurate and give them an experience close to the source material. And yeah even I who grew up with these stories didn't know how to analyze them till I was taught about them at school. Before I was reading about it or hearing about it. You do not need to make a literary analysis to the movie to appreciate it.

For real! And if "people not understand" gives you an excuse to destroy classical stories then why are they complaining on the "stereotyped" Hollywood movies of the past? Why are they complaining on comics like let's say Lucky Luke for portraying indigenous americans in a ridiculous way? (And those comics were ridiculous in the first place. They were not even supposed to be taken seriously just like Disney Hercules or Monty Python movies). Can't the creators of those comics say "oh people are not familiar with native American culture so we can do whatever we want with it". How is that not okay but screwing over greek mythology for DECADES is perfectly fine!? This double standsrd gets me angry more than anything

If old Hollywood was terrible for doing what it did then why are you doing the same to mythology and history? And if it is not unacceptable to do it in the present using this excuse then why old Hollywood is so evil and needs to be corrected? Is one or another.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Shadows of Indigenous Dark Fiction: Never Whistle at Night Anthology Shaina Tranquilino October 27, 2023

In a world where diverse voices are increasingly being heard, literature plays a crucial role in amplifying marginalized perspectives. One such remarkable work is the anthology "Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology," edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. This collection of haunting stories offers readers a unique glimpse into the rich tapestry of indigenous folklore, horror, and speculative fiction. As we delve into the depths of this book, we discover tales that challenge stereotypes and provide a fresh perspective on traditional storytelling.

Diverse Voices Unleashed:

Never Whistle at Night stands as an important literary milestone in its ability to bring together Indigenous authors from various tribes and backgrounds. Each story is crafted with immense care, capturing the essence of cultural heritage while embracing the dark realms of fiction. The authors skillfully blend elements of horror, fantasy, and suspense to create narratives that both entertain and educate.

Exploring Indigenous Folklore:

One notable aspect of this anthology is its exploration of Indigenous folklore, which has often been overlooked in mainstream literature. With each turn of the page, readers are transported into worlds filled with spirits, supernatural creatures, and ancient traditions—elements deeply rooted in native cultures. These stories serve as powerful reminders that Indigenous peoples have their own myths and legends that deserve recognition.

Challenging Stereotypes:

A prominent theme throughout Never Whistle at Night is challenging stereotypes surrounding Indigenous communities. By weaving these narratives within dark fiction genres, the authors subvert expectations and offer nuanced portrayals far removed from common clichés. They confront issues such as colonialism, displacement, identity struggles, and generational trauma head-on while simultaneously delivering captivating plots.

Blending Darkness and Light:

The editors' expert curation allows for an engaging balance between darkness and light within the anthology's pages. While some stories may leave readers trembling with fear, others offer solace and hope. This careful equilibrium serves as a reminder that Indigenous experiences encompass both the shadows and the light, just like any other culture.

Impactful Storytelling:

"Never Whistle at Night" showcases the immense talent of its contributors, each story delivering a unique experience to the reader. From chilling tales set in contemporary urban environments to more traditional stories deeply rooted in cultural heritage, there is something for everyone within these pages. The authors' ability to effortlessly blend genres creates an anthology that transcends labels and speaks to a universal human experience.

In "Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology," editors Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. skillfully bring together Indigenous voices that deserve wider recognition. This collection offers readers an opportunity to immerse themselves in captivating narratives while challenging preconceived notions about Indigenous cultures. By showcasing dark fiction infused with rich folklore and thought-provoking themes, this anthology leaves a lasting impact on its audience—a testament to the power of diverse storytelling and literature's ability to bridge gaps between cultures.

#never whistle at night#Indigenous#Indigenous dark fiction anthology#stories#legends#Indigenous dark fiction#anthology review#book recommendation#Indigenous authors#horror#Indigenous literature

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

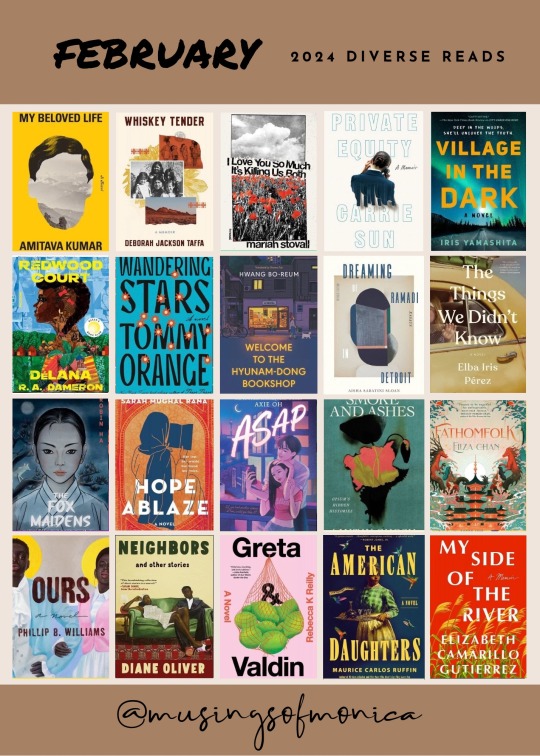

February 2024 Diverse Read

February 2024 Diverse Reads:

•”My Beloved Life” by Amitava Kumar, February 27, Knopf Publishing Group, Historical/Literary/World Literature/India

•”Whiskey Tender: A Memoir” by Deborah Taffa, February 27, Harper, Personal Memoirs/Women/Cultural, Ethnic & Regional/Native American & Aboriginal

•”I Love You So Much It's Killing Us Both” by Mariah Stovall, February 13, Soft Skull, Contemporary/Coming of Age/Friendship/African American/Women

•”Private Equity: A Memoir” by Carrie Sun, February 13, Penguin Press, Personal Memoirs/Women in Business/Business/Finance/Wealth Management/Investments & Securities

•”Village in the Dark” by Iris Yamashita, February 13, Berkley Books, Mystery & Detective/Police Procedural/Thriller/Suspense/Women

•”Redwood Court” by Délana R. a. Dameron, February 06, Dial Press, Literary/Coming of Age/Women/African American/Southern

•”Wandering Stars” by Tommy Orange, February 27, Knopf Publishing Group, Literary/Cultural Heritage/Native American & Aboriginal

•Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop

Hwang Bo-Reum & Shanna Tan (Translator), February 20, Bloomsbury Publishing, Contemporary/City Life/World Literature/Korea

•”Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit: Essays

Aisha Sabatini Sloan, February 20, Graywolf, Essays/Cultural, Ethnic & Regional/African American & Black/LGBT/Anthropology/Cultural & Social

•”The Things We Didn't Know” by Elba Iris Pérez, February 06, Gallery Books, Literary/Coming of Age/World Literature/Puerto Rico/20th Century

•“The Fox Maidens” by Robin Ha, February 13, Harperalley, Comics & Graphic Novels/Historical/Fairy Tales/Folklore/Legends & Mythology Fantasy/Romance/LGBT/World Literature/Korea

•”Hope Ablaze” by Sarah Mughal Rana, February 27, Wednesday Books, Magical Realism, Poetry/Religious/Muslim/Social Themes - Activism & Social Justice

•“ASAP” by Axie Oh, February 06, Harperteen, YA/Romance/Contemporary/Coming of Age/Asian American

•”Smoke and Ashes: Opium's Hidden Histories” by Amitav Ghosh, February 13, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Nonfiction/Historical/Travelogue/Memoir/Family History/Essay in History/Globalism/Capitalism

•”Fathomfolk” by Eliza Chan, February 27, Orbit, Fantasy/Action & Adventure/Dragons & Mythical Creatures/East Asian Mythology

•”Ours” by Phillip B. Williams, February 20, Viking, Literary/Historical/African American/Magical Realism

•”Neighbors and Other Stories” by Diane Oliver, February 13, Grove Press, Short Stories/Literary/Historical/African American & Black

•”Greta & Valdin” by Rebecca K. Reilly, February 06, Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster, Literary/Romcom/Family Life/LGBT/Cultural Heritage/World Literature/New Zealand/Cultural, Ethnic & Regional/Russian-Maori-Catalonian/Indigenous/Polynesian

•”The American Daughters” by Maurice Carlos Ruffin, February 27, One World, Historical/Civil War Era/Saga/African American/Women

•”My Side of the River: A Memoir” by Elizabeth Camarillo Gutierrez, January 13, St. Martin's Press, Personal Memoirs/Cultural, Ethnic & Regional/Hispanic & Latino/Public Policy - Immigration

#books#bookworm#bookish#book lover#bookaddict#reading#book#bookaholic#bibliophile#booklr#reading list#to read#books and reading#reading recommendations#book recs#book reccs#book recommendations#books to read#diverse books#diverse authors#new books#bookstagram#books & libraries#books and libraries

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosemany Laing (1959-2024) Australian

1 The Flowering of the Strange Orchid (2017) archival pigment print 103 x 203cm

2 brumby mound #5 (2003) C type photo 109.9 x 225cm

3 Aristide (2010) C type photo 110 x 223cm

4 weather#9 (2006) C Type photograph 129 x 205 cm

5 welcome to Australia (2004) C Type photograph 110 x 224cm

6 flight research #5 (1999) C Type photograph 107 x 240cm

A tolarnogalleries.com

Rosemary Laing is a photo-based artist. Her projects are most often created in relation to cultural and/or historically resonant locations throughout Australia. With interventions undertaken in situ or through the use of choreographed performance work, she engages with the politics of place and contemporary culture.

B Victoria Lynn

Laing has spent time researching the history of land and the notion of landscapes at length, and through multiple angles. This has included film, literature, and painting, and the belief systems of Indigenous people. “Laing asks us to think through our own relationship to these bodies of knowledge and our sense of belonging and displacement in these landscapes.

C Rachel Kent

Eschewing digital means, Laing worked in situ to construct her dramatic tableaux, with performers from athletes to stuntwomen, and other collaborators.

D artgallery.nsw.gov.au

In the 'flight research' series Laing photographed a woman wearing a bridal dress suspended in the air. In some works she hovers over an extensive mountainous landscape seeming to defy the laws of gravity. In others such as this image there is a poignant sense of impending disaster as the bride tips forward hands outstretched, seeming to anticipate her eventual contact with the earth. The bright cerulean blue of the sky and the white of the bride’s dress make a dramatic contrast and seem symbolic, the blue suggesting infinite space and traditionally the heavens and the white dress carrying the weight of virginity, innocence and purity.

Laing has created several series around flight and movement including 'brownwork' photographed at Sydney airport in which figures interact with planes and tarmac in unexpected ways. However the 'flight research' and 'Bulletproofglass' series are the most enigmatic with their subject matter of hovering brides. These surreal images echo the role the bride has had in popular culture - in films such as 'Muriels wedding' (1994) - and in high culture in such paintings as Arthur Boyd’s Brides series. The symbolism of the bride remains powerful in modern and contemporary culture and Laing participates with her own images which suggest both freedom and transcendence but also impending tragedy and disaster.

5 notes

·

View notes