#conrad anker

Text

Western history is full of the daring feats of explorers—Lewis and Clark in North America, John Cabot in Canada, Marco Polo along the Silk Road, and the list goes on.

But what about the explorers who set out with the same optimism as these navigational celebrities, only to face mysterious adversity?

Here are five explorers who had all the advantages of their more successful counterparts, only not to reach their goals and leave very little trace of their true fates.

Franklin’s failed Northwest Passage quest

British explorer Sir John Franklin left England in 1845 with 129 crew members and officers in search of the Northwest Passage, a shipping route from the Atlantic to the Pacific through Canada.

They were expertly equipped with iron-sheathed ships, three years of food and drink, even an early daguerreotype camera.

Instead of finding the passage, however, the ships became trapped in the Canadian Arctic’s most treacherous, ice-choked corner, north of King William Island.

Twenty-four men died by April 1848, including the captain.

The new captain, Francis Crozier, apparently abandoned the ships and set out with the remaining crew over the icy terrain in a desperate attempt to reach land.

Inuit hunters reported seeing bedraggled crewmen dragging sleds across the ice.

A few bodies have since been found, along with deserted campsites and bits and pieces, including silver dessert spoons and cotton shirt fragments.

In 2014, the wreck of Erebus was located, followed by the Terror in 2016.

While the wrecks themselves did not solve the mystery of what killed the men, the recovered bones of some men bore knife marks, suggesting the crew was fending off starvation by cannibalism.

Fawcett’s Lost City of Z

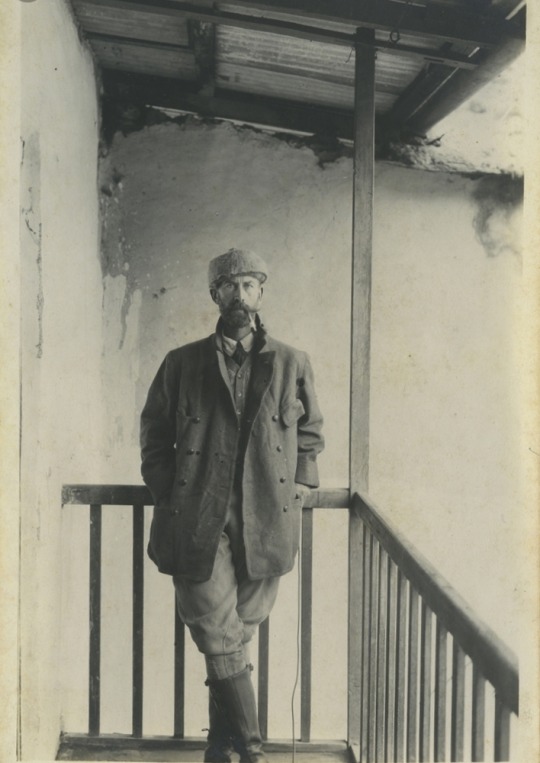

British explorer Col. Percy Harrison Fawcett already had undertaken several expeditions into the Amazon early in the 20th century when he came across an irresistible Portuguese document at the National Library of Brazil.

Detailing the discovery of a “large, hidden, and very ancient city, without inhabitants, discovered in the year 1753,” it told of grand ruins hidden in the Mato Grosso jungle.

Fawcett instantly decided to find the ruins, which he named the Lost City of Z.

After one failed attempt to find this awesome site, Fawcett, his son Jack, his son’s friend Raleigh Rimell, and two local laborers departed into the Brazilian wilderness in April 1925.

They wrote their last dispatch home on May 20.

Their Brazilian helpers had left them, Fawcett noted, but “You need have no fear of failure.”

No one ever heard from the party again.

Their disappearance became an obsession, with adventurers over the next decades trying to retrace their steps.

A reporter who went after Fawcett in 1930 also disappeared, as did a Swiss hunter and his search party.

Unconfirmed reports filtered out from the jungle of pale-skinned prisoners and their young children, but Fawcett and his party have never been found.

Mallory’s ill-fated Everest summit

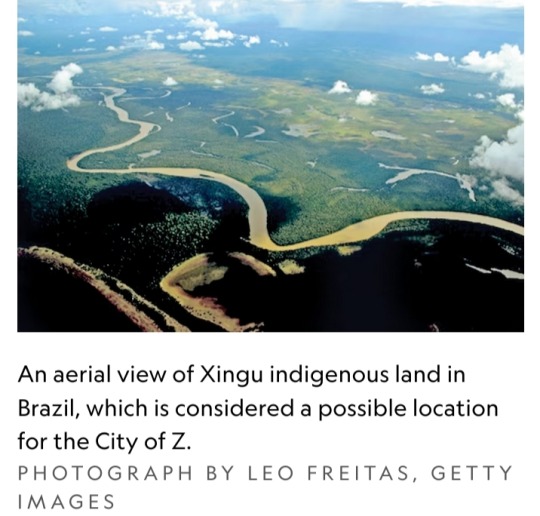

The hopes of the world, or at least of the world’s mountain-climbing community, were pinned on George Leigh Mallory when he began his third attempt to reach the summit of Mount Everest in April 1924.

The handsome English climber had reached 27,235 feet, 1,800 feet below Everest’s peak, on a 1922 expedition.

This time, he intended to make it to the top.

On June 8, Mallory and his young companion, Sandy Irvine, set out on what they hoped would be the final sprint.

A fellow climber spotted them, two black spots, about 800 vertical feet below the summit. Then a snow squall closed in, and the climbers disappeared.

Mallory’s body was not recovered for 75 years.

In 1999, climber Conrad Anker discovered Mallory’s frozen corpse at 26,760 feet on the mountain’s north face. Irvine’s body has not been found.

Whether Mallory was on his way up to the summit or was coming down from a successful ascent is unknown.

If he did reach the peak, he would have beaten Edmund Hillary, the New Zealand mountaineer who has been lauded for being the first man to reach the summit since his successful ascent in 1953.

But the world may never know.

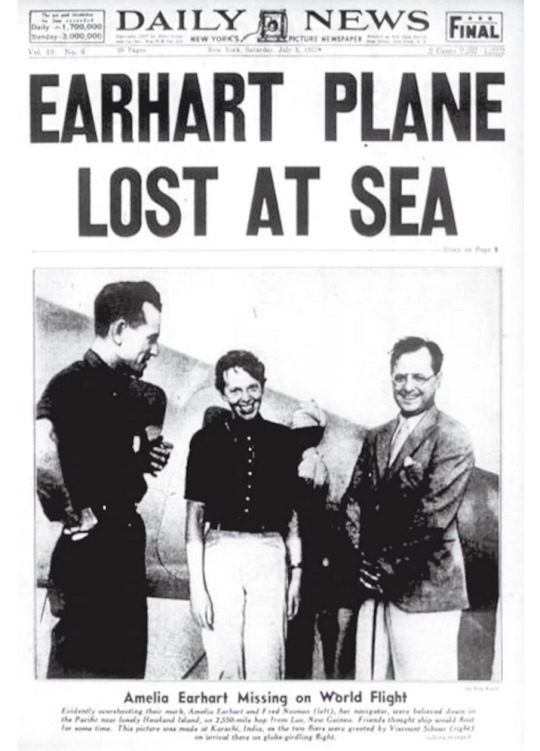

Amelia Earhart’s strange disappearance

Amelia Earhart was world famous. She was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic and the first person to fly from Hawaii to California.

Her round-the-world flight in 1937 was her final challenge.

Accompanying her when she took off from Miami on 1 June 1937 was an experienced navigator, Frederick Noonan.

The first legs of the 29,000-mile trip were arduous, but the 2,556-mile Pacific leg from New Guinea to tiny Howland Island was the toughest of all.

From the air, Earhart radioed she couldn’t see the island and was running low on fuel. Then silence.

Recent forensic analysis suggest that bones found in 1940 on the Pacific island of Nikumaroro were those of the aviator.

Dimensions of Earhart’s body according to photos and clothing matched measurements recorded of the bones.

Unfortunately, the bones themselves were lost—so DNA testing cannot be done.

Researchers are still following every lead, from a skull fragment found in a museum to underwater fragments possibly from her plane, but so far, her disappearance remains a mystery.

Ambrose Bierce’s baffling Mexican quest

Ambrose Bierce isn’t the typical explorer. A Civil War veteran, he was also a journalist and poet, known for his cynical and misanthropic writings.

One such entry in his Devil’s Dictionary, for example, reads, “Fidelity: A virtue peculiar to those who are about to be betrayed.”

In 1913, with his family dead and his career waning, the 71-year-old Bierce headed out to visit Civil War battlefields, including Missionary Ridge and Chickamauga, and onward to Mexico.

“I am going to Mexico with a pretty definite purpose, which is not at all presently disclosable,” he wrote to his secretary.

He may have joined up with Pancho Villa’s rebel army and traveled with it to Chihuahua.

Reports from one of Villa’s battles told of an “old gringo” killed in the fighting.

Could that have been Bierce? Or did he live on in Mexico, California, France, or Brazil, where reports have placed him over the years?

#Sir John Franklin#Northwest Passage#King William Island#Col. Percy Harrison Fawcett#Amazon#Lost City of Z#Mato Grosso#George Leigh Mallory#Sandy Irvine#Mt. Everest#Conrad Anker#Amelia Earhart#Frederick Noonan#Nikumaroro#Ambrose Bierce#Mexico#explorers#missing explorers#mystery#disappearance

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a poll for a movie that doesn't exist.

It is vintage times. The powers that be have decided to again remake the classic vampire novel Dracula for the screen. in an amazing show of inter-studio solidarity, Hollywood’s most elite hotties are up for the starring roles. the producers know whoever they cast will greatly impact the genre, quality, and tone of the finished film, so they are turning to their wisest voices for guidance.

you are the new casting director for this star-studded epic. choose your players wisely.

Previously cast:

Jonathan Harker—Jimmy Stewart

The Old Woman—Martita Hunt

Count Dracula—Gloria Holden

Mina Murray—Setsuko Hara

Lucy Westenra—Judy Garland

The Three Voluptuous Women—Betty Grable, Marilyn Monroe, and Lauren Bacall

Dr. Jack Seward—Vincent Price

Quincey P. Morris—Toshiro Mifune

Arthur Holmwood—Sidney Poitier

R.M. Renfield—Conrad Veidt

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

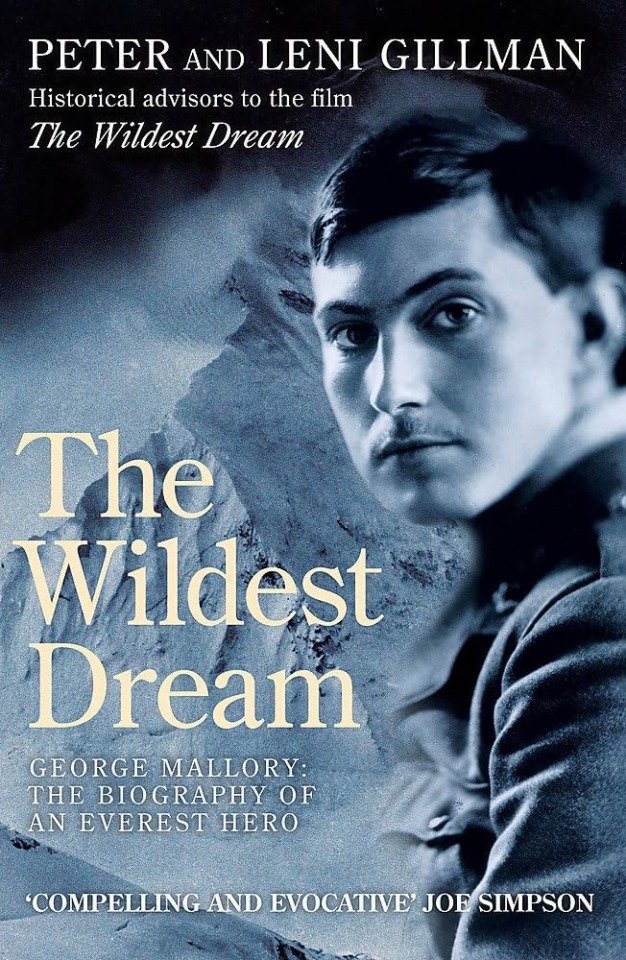

The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest Film

The film The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest, Distributed by: National Geographic Society is a thrilling documentary that explores George Mallory’s attempt to climb Mount Everest in 1924. Mallory and his climbing partner, Andrew Irvine, were last seen 800 feet from the summit of Everest in 1924, and in 1999 American mountaineer Conrad Anker discovered his body frozen on the mountain. Did Mallory make it to the summit?

youtube

This is the official history of the 1924 expedition, it is considered an exceptional account of the 1924 tragedy; also of the discovery of Mallory's body in 1999 and the historic "re-enactment" of the climb in 2007, where the famous "second step" was climbed freely as Mallory would have done, had he and Irvine made the "summit" in 1924. There is a surprising amount of detail, skillfully told in a way that maintains the reader's interest. The mystery of whether Mallory and Irvine were the first to reach the summit of Everest remains, but we now know more intimately the trials and tribulations they endured in their effort to do so. In an era of technological advances, the rise from the North remains formidable. The film, the soundtrack and this book already exist.

Mallory had promised his beloved wife Ruth to leave a picture of her at the top of the mountain. No picture of her was found in Mallory’s very much intact remains. Does that mean he left the picture at the summit, and therefore made it to the highest peak in the world decades before Edmund Hillary officially climbed Everest?

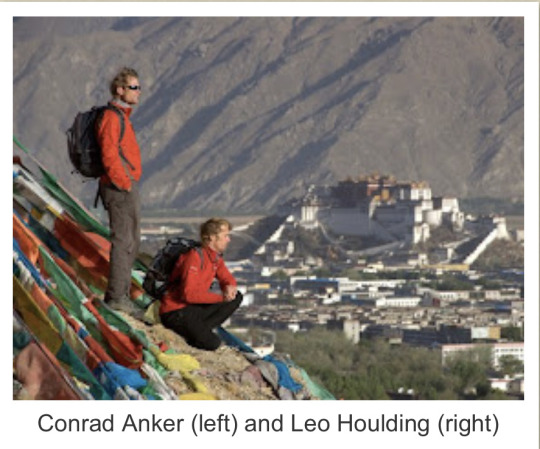

Conrad Anker, in modern climbing gear, ascends a nearly vertical rock formation on Mount Everest during the filming of The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest. PHOTOGRAPH BY JIMMY CHIN

The film The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest, is a mix of historical documentary and modern-day climbing adventure. It is a love story intertwined with Mallory’s insatiable passion that haunted him to achieve his “Wildest Dream” to climb Mount Everest. It parallels Mallory’s fears and desires with that of modern-day climber Conrad Anker.

Modern climbers Conrad Anker and Leo Houlding dress in attire and use gear that Mallory and Irvine would have used in their 1924 climb of Mount Everest. Courtesy National Geographic Film

Conrad Anker, with the help of National Geographic Entertainment, decided to find out if Mallory could have indeed reached the summit in 1924. It seems very appropriate that the man who discovered Mallory’s body was the one who would return to Everest and find out. Using hobnailed boots, and recreated gabardine apparel, Anker simulates some of the climbing conditions Mallory would have faced. Using modern gear, but no fixed ladder, Anker and his climbing partner attempt the “Second Step”, the famous last section of Everest that Mallory would have had to free-climb to reach the summit.

Modern climbers in vintage climbing gear of the 1920s

An additional element of intrigue is that the film was narrated by Liam Neeson and his late wife Natasha Richardson. Richardson recorded the part of Mallory’s wife, Ruth. Just before the actress Richardson passed away in a fatal ski accident in March 2010, she was reading the part of Ruth Mallory, who had to tell her children about their father’s death. Film director Anthony Geffen said that she teared up and said she just couldn’t imagine telling her children such news. Just a few weeks later Liam Neeson had to do exactly that!

The film is based on the biography of George Mallory: The Wildest Dream. Chronicles all three of Mallory's Everest expeditions. Illuminates how Mallory reconciled his ambitions on Everest with his unquestioned love for his wife and family.

@kiaora45 It was my pleasure 💙

#biography #GeorgeMallory #TheWildestDream #ConradAnker #LeoHolding #ConquestofEverest #NationalGeographicSociety #GeorgeMallory #RuthMallory # mountaineer #alpinist #climber #LiamNeeson #NatashaRichardson #Everest #NationalGeographicEntertainment #Film #AnthonyGeffen

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

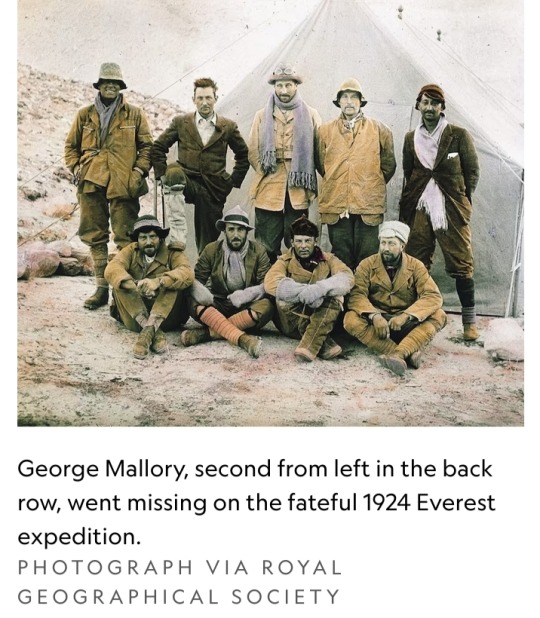

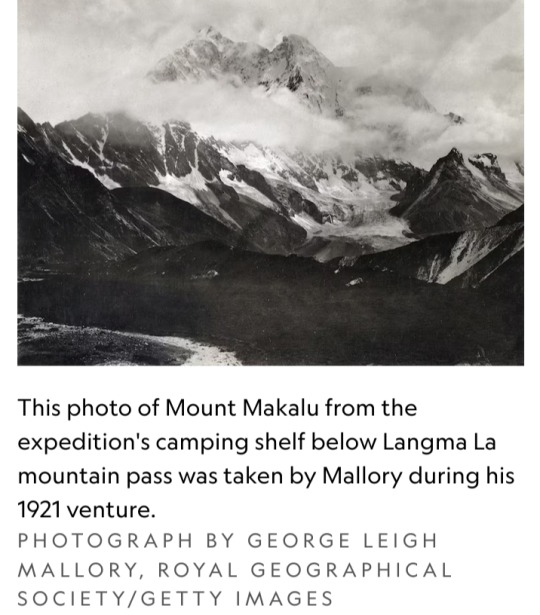

A Photo By George Mallory of Mount Everest from 22,500 feet taken during the 1921 expedition. Royal Geographical Society/Getty Images

The Unending Allure Of High Mountains

A Century After George Mallory’s Disappearance On Everest, Why Do His Words, “Because It’s There,” Remain An Indelible Explanation For The Human Obsession With High Places?

— By Henry Wismayer | June 6, 2024

At 12.50 p.m. on June 8, 1924, high on the Tibetan flank of Mount Everest, Noel Odell clambered onto a small crag just as the clouds overhead dissipated. Far above, on the northeast ridge, two spidery dots were moving uphill.

The lower dot, he guessed, was the greenhorn, Sandy Irvine, a first-timer to the Himalayas who had nonetheless proved himself to be indefatigable on the mountain. The man he was following was the most feted climber of his generation. The leading light of the expedition and already a global celebrity, George Mallory was now edging toward the greatest unclaimed trophy in exploration. Judging by their steady progress and convinced of Mallory’s resolve and prowess, Odell felt sure they would make the summit. The moment was transitory and everlasting. “Then the whole fascinating vision vanished,” Odell would recall later, “enveloped in cloud once more.”

The next person to see Mallory was Conrad Anker, on May 1, 1999. Anker, a preeminent American climber, was part of an expedition assembled to find Mallory and Irvine’s bodies. Following gut instinct, Anker’s furlough in the Death Zone was mere hours old when he spotted “a patch of alabaster … [a] body that wasn’t modern.” He conveyed the news to teammates elsewhere on the mountain over an open radio channel with a prearranged coded message: “I’ve got a thermos of Tang juice and some Snicker bars. Why don’t you guys come down and have a little picnic with me? Over.”

A nametag sewn onto a shirt collar confirmed the corpse’s identity: “G. Mallory.” For 75 years, Mallory’s body had lain on this spot at 26,670 feet. Jet-stream winds had shredded his clothes to rags. Years of harsh sun had bleached his exposed skin a pearlescent white. His right leg was broken at a grotesque angle and the mummified torso was abraded on its right side, evidence of a catastrophic fall. Aspects of his posture — the left leg placed protectively over the shattered right, fingertips dug into the shale as if fighting to stymie a slide — led his discoverers to conclude that he had died not from the fall but from exposure.

Before they buried the body beneath a pile of stones, Anker’s team frisked it for possessions. Decades after the 1924 expedition, Mallory’s eldest daughter Clare had recalled her father’s promise to leave a photograph of his wife, Ruth, on Everest’s summit. Among the items in his pockets were a brass altimeter, a monogrammed handkerchief, a tin of bouillon cubes and a pocketknife. No sign of the photograph could be found.

“Behind the mystery of the first ascent of Earth’s tallest peak lurks another conundrum, one to which Mallory’s own answer still echoes through the decades.”

This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit.

“It’s the ultimate exploration detective story,” said Mick Conefrey, whose new book “Fallen” (2024), is the latest to dissect the 1924 expedition and its aftermath. “Mallory was the most romantic figure in the early history of mountaineering. The fact that he climbed ‘unplugged,’ without any down clothing, satellite phone or Kevlar oxygen bottle, means that people really want to believe he could have done it.” Definitive proof may never arrive. Irvine may have been carrying a Kodak Vest Pocket camera, the film inside which, were it ever recovered, might solve the question. But his body remains missing, imprisoned somewhere in the Himalayan deep freeze.

Behind the mystery of the first ascent of Earth’s tallest peak lurks another conundrum, one to which Mallory’s own answer still echoes through the decades. Beyond vainglory, what was drawing these men toward the roof of the world? A year or so before his disappearance, while Mallory was on a fundraising lecture tour in America, a persistent New York Times pressman asked him a question he’d been subjected to many times before: Why climb Everest at all? An antic Mallory answered: “Because it’s there.”

It is strange to consider that a laconic retort should become the most famous explanation for the human urge to climb mountains, if not for all exploration. However, wittingly or not, Mallory’s words captured an enigmatic allure which, in the decades after his disappearance, would only grow. The summit pyramid that was once Mallory and Irvine’s alone is today a lodestar for modern thrill-seekers, some of whom pay tens of thousands of dollars to endure the annual traffic jam beneath the Hillary Step, even though cold probability suggests that some of them will never return.

The past and present votaries of Everest are merely the most conspicuous exemplars of a universal longing. For millions of hikers, climbers, skiers and weekend ramblers, the mountains are places of romance, recreation and refuge. Our love affair with them has shaped a shared culture as well as our ideas and ideals. On that day a century ago, Mallory became a martyr to a visceral compulsion: the urge to ascend.

Into The Alps

A couple of months ago, in the ebbing weeks of the European winter, I traveled to the Swiss Alps to contemplate a mountain. Like many armchair adventurers, I’d chewed over the Mallory mystery for years; the story always seemed like the ultimate allegory of a fascination I shared. Though I am no climber, I’ve rarely seen a mountain without wanting in some deep fiber of my being to be on top of it. Determined to explore what drew Mallory and today entices millions of others toward the great ranges, I set my sights on the Bernese Oberland.

Specifically, I wanted to see the Eiger. Topping out at 13,015 feet, the Eiger ranks 33rd on the list of the Alps’ highest peaks. The most straightforward route to the summit, the west flank, was first climbed in 1858 by Charles Barrington, a merchant from County Wicklow in Ireland, and two Swiss guides. “Thus ended my first and only visit to Switzerland,” Barrington wrote later. “Not having enough money with me to try the Matterhorn, I went home.”

The Eiger is notorious for its north face, or Nordwand, the vertiginous limestone cliff that menaces the Grindelwald Valley. For years now, I’d been reading about this fabled slab, which for many embodies the mesmerism and overwhelming physicality of the quintessential mountain. But I had seldom spent much time in the Alps, deeming the developed and populous countries of Western Europe too trodden and too tamed. The naivety of this presumption struck me foursquare when I caught first sight of the Nordwand as the train neared the station at Kleine Scheidegg.

An hour before dusk, with the Eiger glowering through evening clouds, I pushed through the revolving doors of the Bellevue des Alpes Hotel. The descendent of a hotel that has stood on the Scheidegg Pass for almost two centuries, the Bellevue is a grand dame kept in aspic, all wood-paneled drawing rooms and haute cuisine served by white-jacketed waiters. It is also a waymarker in the progress of an infatuation.

The Urge To Ascend

The human tendency to ascribe meaning to mountains is common to the societies that live in their shadow. As civilization spread around the globe, numerous peoples settled in mountainous areas, adapting their lifestyles and even their physiologies to existence at altitude. Archaeological records suggest that people have been present on the Tibetan Plateau for at least 30,000 years. The Andes have been inhabited year-round since at least 5,000 B.C.E.

From afar, these mountain peaks, by virtue of their salience and metaphorical potency, have long inspired awe and reverence. Massifs like Olympus, Himinbjörg and Kailash have served, in different eras and for different religions, as holy mountains, abodes of the gods. Today, in Bhutan, where Buddhism still merges with animist mythology, the high peaks are sacrosanct and mostly unclimbed. Others, like Tài Shān in China or Adam’s Peak in Sri Lanka, are objects of daily pilgrimage. Setting foot on a mountain can be devotional or blasphemous. Either way, the high peak, talismanic and remote, is often viewed as a surrogate for heaven.

The secular impulse to climb mountains for respite and adventure is much younger. Up until the middle of the 18th century, regions like the Bernese Oberland were viewed with fear and suspicion, environments inimical to human survival. Beauty was seen in landscapes pacified by human hands — in the bucolic picturesque of the English painter John Constable, in rolling fields bound by hedge and furrow. The highlands, with their impassable terrain, freezing temperatures and asphyxiating air, represented ungovernable chaos; it was commonplace to describe them as blemishes or “warts” and to explain their formation as scars, deformities wrought on the once-virginal land by the cataclysm of the biblical flood.

A seismic shift in our perception of mountainous landscapes can be traced back to the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment. As science challenged religious orthodoxy, it ushered in a new humanistic way of seeing the world and a concomitant desire to rationalize wild places. Soon, this inquisitiveness turned skyward. It was as if, in demystifying the processes once ascribed to the supernatural, the empiricists sought to dethrone the deities and claim the firmament for their own.

In late 1783, the first manned untethered hot-air balloon, designed by the Montgolfier brothers, soared for 25 minutes through the skies over Paris. Three years later, when Jacques Balmat and Michel-Gabriel Paccard made the first successful ascent of Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in the Alps, an imaginative barrier was breached. Over the next century, almost every Alpine peak succumbed to human trespass, and cartographers and geologists colored in the surrounding topography. In 1857, the Alpine Club in London became the world’s first climbing society, a graduation for mountaineering into an organized endeavor.

For the less intrepid traveler, too, the mountains were starting to exert a peculiar aesthetic gravity. By the middle of the 19th century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s exhortation to retour à l’état de nature, subsequently refined by the artistic movements of Romanticism and Transcendentalism, had taken seed in the minds of a growing leisure class. Early Grand Tourers traversing the Alps en route to Italy were known to pull the blinds of their carriages to spare their gaze from the unsightly disorder of mountain vistas. Now their successors were traveling to places like Kleine Scheidegg to seek them out. The Eiger and its titanic neighbors Mönch and Jungfrau took their place among the iconography of “Alpenbegeisterung,” enthusiasm for the Alps.

“The high peak, talismanic and remote, is often viewed as a surrogate for heaven.”

The hostelry that would evolve into the Bellevue des Alpes opened its doors in 1840. It began as nothing more than “a mountain hut where ten or so people could sleep next to each other in the hay,” the current owner, Andreas von Almen, told me. Over the ensuing years, it would grow with the tourist footfall. A major expansion coincided with the arrival of the railway from the low valleys in 1893. Its present incarnation dates back to 1925 when the whole joint was refitted for its first winter season. By then, an activity that would evolve into a global pastime, alpine skiing, was gaining popularity. The cruel landscape of pre-Enlightenment superstition had receded. The mountains had become scenery, and then a playground.

Among the high peaks, new generations of Nietzschean supermen were pushing the fascination to its upmost limits. Tales of courage and tragedy from the precipice, recounted in books and periodicals, fed a public appetite for vicarious adventure. In 1871, Edward Whymper’s “Scrambles Amongst the Alps,” which included an account of a descent on the Matterhorn when four of Whymper’s companions plunged to their deaths, was a publishing sensation. Mallory’s forays on Everest in the 1920s were chronicled in daily bulletins in The Times of London.

The Nordwand, a 6,000-foot concave rampart, sheened in verglas, was a different proposition — “the epitome,” wrote the Austrian alpinist and explorer Heinrich Harrer, “of everything tragically sensational in mountain climbing.” Well into the 20th century, as ski lifts and funiculars began to appear in the surrounding valleys, many an accomplished mountaineer insisted it was unclimbable. In time, its ribs and crannies would assume a fantastical toponymy: “White Spider,” “Death Bivouac,” “Traverse of the Gods.” Von Almen, who is lank and patrician with a stentorian Teutonic voice like Werner Herzog’s, called it “a vertical arena,” the climber’s Colosseum.

The first attempts to surmount the Nordwand ended in catastrophe. On the most infamous occasion, in 1936, a four-strong team made it halfway up the face before turning back. On the retreat, an avalanche killed three of the party, leaving a lone survivor, Toni Kurz, dangling helplessly from a rope. Held up only by the stuck body of a dead colleague, unable to climb or descend, Kurz battled to free himself for 14 hours, as a rescue party strove in vain to reach him, before succumbing to exposure and exhaustion.

Here was the mountain’s pull operating at different valences. At the bleeding edge was Kurz, suspended above the void. But also beholden were the guests at the Bellevue, who watched the tragedy play out from their bedroom windows, and millions of others, who read about Kurz’s operatic demise in the newspapers at home.

The route would eventually yield to Harrer and his team in 1938. Their photographic portraits, sun-leathered faces squinting into the lens, sit alongside those of the Nordwand’s other victors and victims on the wall of the Bellevue’s central corridor. “You could sit, drink a coffee, eat a cake, all while watching the climbers through a telescope,” said von Almen, who took over the hotel with his wife Silvia in 1998. “Nobody had seen anything like it before.” The idea of mountain country as the ultimate proving ground of human fortitude was now etched onto the modern mind.

A 19th-Century Engraving of the Eiger in Switzerland. Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Conquering The Heights

The burgeoning love affair between human and mountain was kindled by a new Romantic sensibility, but it also intersected with that other European preoccupation, the race of nations. To the empire-builders looking to plant flags on the last unexplored tracts of terra incognita, the peaks, like the poles, were first and foremost prizes to be won.

“As I sat daily in my room, and saw that range of snowy battlements uplifted against the sky … I felt it should be the business of Englishmen, if of anybody, to reach the summit,” wrote Lord George Curzon, later the viceroy of India, as he gazed at the Himalayan horizon from the hill station of Simla in 1899. In 1952, the year before Curzon’s vision was fulfilled, the Manchester Guardian newspaper alleged that an abortive attempt Everest set out with an intention to erect statues of Lenin and Stalin at its apex. When news that the ninth British expedition to the mountain had finally put two men on the summit reached London the day before Elizabeth II’s coronation, the same journal heralded the achievement as “a new, timely, and brilliant jewel in the Queen’s diadem.”

Still today, highlands play host to fierce competition; summits are “conquered” or “bagged,” connoting mastery over nature, however illusory. Julie Rak, a professor at the University of Alberta and the author of “False Summit” (2021), has written about how the alpine Rückenfigur — literally “back-figure,” the artistic depiction of a person looking out over a mountain panorama — has become an enduring motif of individual romantic status. “Mountaineering would become intimately connected to personal sovereignty and the development of the self,” she told me over a video call. “Climbing a peak and looking out from the summit becomes a way of possessing the surrounding land.”

For the climber, one aspect of the mountains’ allure undoubtedly stems from the physical and mental challenges they pose. Another victim of the Nordwand, the American climber John Harlin, put it concisely: “Control of fear is the spice.” But even the most pedestrian interaction with mountains might also impart a sense of accomplishment and the endorphin rush of physical effort. The simple act of walking through rugged terrain fosters agency and self-possession — what Rebecca Solnit, in “Wanderlust” (2000), called the “kinesthetic pleasures of one’s body moving at the limit of its ability.” Footsore and ravenous, the hiker at the end of a day in the hills will often find that food tastes better, that they have never slept so well.

Dissolution & Awakening

On October 14, 1976, another pair of British tyros, Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker, were inching up the west wall of Changabang, a granite spire in the Garhwal Himalayas. Boardman later described the experience of climbing the final pitch as something close to rapture:

I felt in perfect control and knew the thrill of seeing the ropes from my waist curl down through empty space. I was as light as the air around me, as if I were dancing on tip-toes, relaxed, measuring every movement and seeking a complete economy of effort. Speak with your eyes, speak with your hands, let it all flow from your heart. True communication, true communion, is silent.

I first encountered this passage in “Fallen Giants” (2008), a history of Himalayan mountaineering by Maurice Isserman and Stewart Weaver, and it is now inscribed in my memory. There is something incantatory about the words, which, in conveying the climb as totalizing and transcendental, resemble the utterances of a disciple groping toward enlightenment. For Boardman and Tasker, chasing that pure high would prove costly. Both would perish attempting a new route up Everest in 1982.

Many of us who will never know the exhilaration of a vertical rock face in the Himalayas will nevertheless have some inkling of the heightened consciousness that Boardman articulates. Ascent yields aesthetic rewards, but it also confers perspective. “You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again, the surrealist René Daumal wrote in his unfinished novel, “Mount Analogue” (1952). “So why bother in the first place? Just this: what is above knows what is below but what is below does not know what is above.” Like all knowledge, however, attaining it only makes the recipient appreciate how little they truly understand.

For all the hubris and one-upmanship that might serve as ostensible motivation for a mountain adventure, the takeaway is often less a sense of triumph than of humility. After summiting the Nordwand, Harrer said: “I was conscious of the privilege of having been allowed to live.” Within the climber’s honor code there exist right ways to pay homage — or, as the journalist and climber Jon Krakauer put it, “a very strong sense of how the game ought to be played.” In time, mountaineers would disavow the siege-like methods of Mallory’s era, instead prioritizing self-reliance, ethical purity and the brotherhood of the rope. Today, Mount Everest is often lamented for its human litter and commodification; even in 1997, Krakauer was describing it as a “slag heap.” Just this year, a signboard welcoming visitors to basecamp stirred controversy. The closer the furniture of civilization presses, the more the mountain is defiled.

One concept that recurs again and again in accounts of time spent among the mountains is immanence, a desire to become one with the landscape. In “The Living Mountain” (written in 1945 but only published in 1977), Nan Shepherd’s slender panegyric describes the author’s experiences and meditations during a lifetime of walking in the Cairngorms, “a mass of granite thrust up through the schists and gneiss that form the lower surrounding hills,” in northeast Scotland.

Shepherd writes of the mountains as a place of existential immediacy and primordial magic. Her Cairngorms are an elemental sensorium, intimate but unknowable; spending time among them “intensifies life to the point of glory.” Most of all, Shepherd pursues dissolution. As she explores the ridges and recesses, bathes naked in tarns, and sleeps in the wide open, she presents the environment as a single animate body, a place that “does nothing, absolutely nothing, but be itself.” It is with this vast entity that the open-minded visitor might seek to become merged. Like the crofters and gamekeepers who live in its valleys, Shepherd wishes to become “bone of the mountain.” And so, through all seasons and weathers, with “senses keyed,” she “walks the flesh transparent.” In places, “The Living Mountain” reads like an animist hymn:

So there I lie on the plateau, under me the central core of fire from which was thrust this grumbling grinding mass of plutonic rock, over me blue air, and between the fire of the rock and the fire of the sun, scree, soil and water, moss, grass, flower and tree, insect, bird and beast, wind, rain and snow — the total mountain. Slowly I have found my way in.

Among the heights, Shepherd gave lyrical weight to a widespread intuition: that being in the mountains precipitates awakening. It is common for walkers and climbers to report experiencing reveries in high places. People talk about the radiance of the light, of pregnant silences and quickening skies. Forever prone to anthropomorphizing the mountain, we refer to its brow, shoulders, flanks and feet. Though it is absurd to accord sentience to a pile of rock, we often perceive mountains as mercurial, places of moods. At times they are beneficent, river-bearers, all-seeing guardians; at others, they transmute into implacable godheads conjuring wrathful weather.

This idea that the mountain is a repository of esoteric energy tends to be central to the various religious doctrines that venerate them. Recently, I spoke to Tim Bunting, an adherent of Shugendō, an ancient form of mountain worship still practiced in some areas of Japan. Originally from New Zealand, Bunting moved to Yamagata Prefecture to teach English in 2010 but threw himself into Shugendō in 2016 after the sudden death of his father. “Most people come to Shugendō at some sort of turning point in their life,” he told me. “We see mountains as a space to reflect and gather, get direction.”

Soon, Bunting was initiated as a yamabushi, literally “one who prostrates before mountains.” Based around the three sacred peaks of Dewa Sanzan, his sect follows a Shinto-adjacent form of Shugendō and incorporates elements of Buddhism and nature worship. Devotees walk for miles through the thick-forested slopes dressed in white vestments and take part in weeklong ascetic retreats punctuated by prayer, chanting and rituals, the contents of which are closely guarded. Upon arriving at a place of meditation, a conch is blown to greet the Shinto divinities, the kami, “to let them know that we’re entering their realm.”

“Being in the mountains precipitates awakening.”

For the yamabushi, the mountains’ potency resides in their liminal nature. Toward the summit of Mount Gassan, highest of the Dewa Sanzan, you eventually emerge above the tree line, Bunting told me. Even in July, when the low valleys swelter, the mountain’s upper reaches might be fogbound and covered in snow. The environmental transition between upland and lowland serves to demarcate a metaphysical boundary. Bunting’s video call background showed a torii, a square red archway at the base of forested hills. “They mark the border between the profane and the sacred,” he explained. Beyond it, the mountain becomes a spiritual plane where the yamabushi can converse with the dead, practice acceptance and pursue rebirth.

“The mountains are the womb,” Bunting said. “Yamabushi believe that entering this landscape takes us back to a time before we were born. You go in and you’re changed. From there, you can rebuild.”

Though the forms by which they express their devotion vary significantly, Boardman, Shepherd and Bunting — climber, poet and pilgrim — all share a conception of the mountain as a threshold, a portal to self-actualization. In communing with landscape, each sees themselves gaining access to a deep wisdom that can only be approached through embodied experience. “To know Being,” Shepherd concluded, “this is the final grace accorded from the mountain.”

The Edges Of The Wild

On my second morning in Kleine Scheidegg, I caught a train into the bowels of the Eiger. In 1896, emboldened by the Alpine tourism boom, a construction team broke ground for a single-cog railway that, even today, seems an astonishing feat of engineering. Thousands of mostly Italian migrant laborers, digging with pick and shovel, burrowed nearly six miles into the limestone, reemerging, 16 years later, onto a saddle above 11,000 feet between Mönch and Jungfrau.

A century on, Jungfraujoch, “the highest station in Europe,” is a magnet for modern mountain lovers — not the lunatic poets of the Nordwand but the tourist public (a million a year according to the railway), who come to take in the view. It is a place to experience modern Alpenbegeisterung in stereo.

The train climbed steeply from Scheidegg Pass, then tunneled into the Eiger’s west flank. My ears popped as we gained altitude, and upon disembarking, many of the passengers staggered drunkenly as they recalibrated to the change in atmosphere.

Up top, beneath the Sphinx Observatory, a wraparound balcony overlooked the glacial junction of Konkordiaplatz. Today’s crowds milled about in a very modern kind of communion. The combination of clear skies and thin air had made everyone giddy. People held their arms wide, as if trying to embrace the panorama. Many selfies happened.

The vibe wasn’t what you might call reverential. The indoor galleries were a study in Alpine kitsch, and a boutique sold Omega and Tissot watches to visitors who hadn’t already been bankrupted by the price of the rail tickets. Later, when I spoke to von Almen about the experience, he despaired of the attraction’s bare-faced commercialization, saying it demonstrated a “disrespect for the mountains.”

But if the crowds at Jungfraujoch seemed touched by a certain fever, it was hard to begrudge. It was a pristine, windless day. The slopes of Mönch and Jungfrau, after the previous day’s dump of snow, stood imperious against a cobalt sky. On the glacier plateau, visitors queued to have their photo taken holding the Swiss flag. Youngsters threw snowballs and slithered down the slope on their backsides. Mountains, it must be remembered, are places of fun as well as enchantment.

Still, there were notes of obeisance. In one tunnel, a bronze statue of Adolf Guyer-Zeller, the entrepreneur who conceived the railway, depicted him in forward motion, naked and muscular, and semi-encased in stone. Back up at the Sphinx terrace, I noticed dozens of votive offerings — Buddhist prayer flags and lovers’ padlocks tethered to the wire balustrade.

Yet I realized with some misanthropic guilt that I hankered to be elsewhere, alone or in more placid company. The proximity of the ridgelines, mingled with a sense that I had cheated the mountain by catching a train to its upper reaches, only amplified my longing to be higher still. I yearned to feel the exposure and solitude of the fastness, to give myself up more completely to the mountain — perhaps even to jump.

Science is yet to settle on a coherent explanation for the compulsion many people feel to launch themselves from precipices. Psychologists call it “the high place phenomenon” or, more poetically, “the call of the void.” Successive studies have found little evidence that it is a form of suicidal ideation, suggesting instead that it indicates the misinterpretation of a survival signal. The reflex does not prefigure an appetite for oblivion but rather escape. We don’t envisage ourselves hitting the ground. We think only of the liberating moment of lift-off.

I waited patiently for a lull in the hubbub. I found a quiet spot on the handrail, got up on tiptoes, and leaned right over the edge.

A Sanctuary In The Sky

Occasionally, an obsession with mountains can slip into mania. In “The End of History and the Last Man” (1992), Francis Fukuyama singled out the mountaineer as an exemplar of a distinctly modern restlessness. In seeking altitude, he speculated, climbers revealed themselves as fidgety malcontents bent on rebelling against what Fukuyama called the end of history, but which could less contentiously be reframed as the nagging banality of bourgeois existence. “The Alpinist has, in short, re-created for him or herself all the conditions of historical struggle: danger, disease, hard work, and finally the risk of violent death,” Fukuyama wrote.

In 2022, a German-Austrian psychiatric survey of alpine club members seemed to support this idea that the uphill impulse might be forged in neurosis. Of people who self-identified as regular or “extreme” mountaineers, those with preexisting psychological disorders were also more likely to push their climbing to extremes. Participants with experiences of anxiety or depression, high levels of stress, or with histories of eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive behavior or alcohol and drug abuse, tended to report climbing harder for longer. They took greater risks and were more intent on “sensation-seeking.” Although the study fell short of establishing the causal direction, the authors speculated that subjects may have been using excessive mountaineering as a form of “self-therapy.”

It’s contentious to suggest that these observations may signify a correlation between a desire to ascend and a penchant for self-destruction. Conjectures about the Freudian “death drive,” the idea that there exists within everyone a bodily instinct to return to a state of quiescence, would seem to contradict the much-documented pleasure that so many of us derive from mountain encounters.

What does seem more universally applicable is that one part of the highlands’ allure lies not in what the mountain is — but what it is not. In contrast to the lowlands, so utterly reshaped by society, the mountains permit only visitation. We covet them precisely because they resist our dominion. Sentinels of geological time, the peaks are often seen to embody a reassuring impassivity, aloof to the human ants playing in their shadow. Elevation, danger, sensory abundance: All of these facets of mountain country cultivate an aura of remoteness. Ascent is also departure. The mountain, in other words, is a place to regress, a sanctuary in the sky.

“Look at the world today. Is there anything more pitiful?” says the High Lama in Frank Capra’s movie adaptation of “Lost Horizon” (1937), about the fictional Tibetan lamasery of Shangri La. “What madness there is! What blindness! A scurrying mass of bewildered humanity crashing headlong against each other. … The world must begin to look for a new life. And it is our hope that they may find it here.”

Many have tried. In 1934, a decade on from Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance, a traumatized ex-soldier called Maurice Wilson flew a Gipsy Moth biplane from London to India, then, disguised as a Buddhist monk, he traveled overland by rail and foot to the base of Everest. With no mountaineering experience, he had emerged from a nervous breakdown two years earlier harboring an eccentric mission to climb the world’s highest mountain alone. As his one-man expedition became bogged down on the intermediate slopes, 6,000 vertical feet from his goal, he must have apprehended the impossibility of the task he’d set for himself. And yet he persevered, setting out for a final time on the last day in May onto the North Col. His body was found there the following year. The last note in his diary, written as he prepared to leave the tent that morning: “Off again, gorgeous day.”

The Potent Myth Of Mallory’s Ascent

Notions of mountains as an enticing refuge where the poetic soul might achieve immanence doubtlessly shaped how Mallory has been remembered. Tragic as it was, the mystery surrounding the exact circumstances of his disappearance invited many to paint it as the ideal hero’s death, the death that posterity demanded.

After combing through the evidence for his new book, Conefrey came to believe it is “almost inconceivable” that Mallory and Irvine summited Everest. “Mallory was a prolific writer,” he told me. “But in this key period of his life there’s no diary, no letters. You’re left with a void that people want to fill.” For Mallory’s contemporaries, and many people thereafter, that has meant conjuring, as Conefrey put it, “a romantic vision of Mallory striving upwards and dying on the summit.”

The reality was that the cultural desire to view the mountaineer as a paradigmatic hero had found, in the lithe and handsome Mallory, an irresistible archetype. In life, many biographers have noted, much was made of his physical perfection. “Mon dieu, George Mallory!” wrote one acquaintance, the writer Lytton Strachey, in a letter to a friend. “My hand trembles, my heart palpitates … He’s six foot high, with the body of an athlete by Praxiteles and a face — oh incredible — the mystery of Botticelli, the refinement and delicacy of a Chinese print.”

Decades later, this characterization of Mallory as an inanimate artwork would echo in the testimonies of those who found him embalmed near the crest of Everest. Steeped in the mythos of gallantry and sacrifice that had grown around Mallory’s story, Anker and his team were less inclined to see a battered corpse than a priceless artifact. One expedition member, Dave Hahn, recalled feeling “like I was viewing a Greek or Roman marble statue.” Talk about immanence. Mallory had become stone.

Such eulogies left little room for the nuances of Mallory’s story, not least the fact that, for months leading up to departure, he had vacillated over whether to leave his wife and young children. In truth, the immortal “Because it’s there” barely scratched the crust off the cauldron of reasons that drew him towards the Himalayas; instead, it is the perfect complement to a romantic legend.

“Sentinels of geological time, the peaks are often seen to embody a reassuring impassivity, aloof to the human ants playing in their shadow.”

“Modern ideas of individualism and aestheticism coalesced around Mallory,” said Rak, who has argued that Mallory’s lionization in the eyes of the press and public bequeathed a spirit of elitism that still pervades climbing culture. “It’s Mallory who makes mountaineering understandable to the ordinary people, but as a result, his legacy becomes outsized. No one can ever climb as well as him. No one can be as pure as him. Everyone who comes afterward can only ever hope to imitate Mallory.” As the myth gathered potency, all of Mallory’s shortcomings, along with the fellow climbers and porters who enabled his ascent, were elided. “Mallory gets pictured later as somebody who almost did it by himself, which is categorically untrue,” Rak added.

Based on his own extensive writings, it is clear that Mallory was bewitched by the mountains because he wanted to be first, and because they made him feel alive. “What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy,” he once wrote. “And joy is, after all, the end of life.” But it seems fair to suppose that he may also have been a fugitive from reality. Like Maurice Wilson, Mallory had fought in the First World War, serving as an artillery officer during the carnage of the Somme. In “Into the Silence” (2011), Wade Davis concluded that the horrors they’d witnessed on the Western Front imbued the 1920s climbers with a special intensity, and perhaps also a desire to flee the lowland world that had so betrayed their generation. For them, Everest had become “a symbol of continuity in a world gone mad.”

Davis posited that the best epitaph for Mallory wasn’t “Because it’s there” but an equally spare sentiment summoned by another expedition member, Bentley Beetham, as the grieving survivors retreated from the mountain: “The price of life is death.” Mallory might have died, but my how he had lived. “Could any man desire a better end?” Beetham asked.

This, then, would be Mallory’s role in death: a cipher for the idealism that swirled about the mountaintops where he met his demise. It is an idealism that straddles secular and spiritual traditions, and one that clarifies the futility of all human endeavor with the promise that, beyond our ken, there resides something higher, something more, something completely outside human control. And because the truth of it can never be truly known, we are free to believe that Mallory, in his final moment, might have attained an apotheosis — that he died not distraught and in agony, but in ecstasy, glimpsing the face of God.

On my final afternoon in Kleine Scheidegg, I walked east from the Bellevue until I found a snowy hill perpendicular to the Nordwand. I walked upward, crunching through foot-deep snow, until I’d freed my sightlines from the human drapery of wires and ski-lifts. I found a dry tussock raised out of the snow, and sat there for some time, neck craned to the wall. Finally, I had the mountain to myself. I thumbed through Krakauer’s account of a failed attempt to breach the Nordwand’s “formidable mythology,” picking out the features I knew from years of reading. More than once, I heard the distant crack and rumble of rockfalls or avalanches reverberate through the valley. It was a perfect hour.

Four thousand miles east, just like in the Alps, the ice is receding from the high Himalayas. Perhaps on some distant future day, sooner than we expect or wish, that inexorable thaw may extrude an antique Kodak camera from the cold grasp of Everest. It occurred to me, with a certainty I hadn’t felt before, what a shame that would be.

— Henry Wismayer is a Writer Based in London.

#The Unending Allure#High Mountains#George Mallory’s Disappearance | Mount 🏔️ Everest#“Because It’s There”#Henry Wismayer#NoēmaMag.Com

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steven's books

okay. I did a very reasonable thing and looked at screenshots of Steven sitting at his desk in episode one when he was trying to stay awake. And i tried to figure out as many of his books as i could

I'll show you the screenshots and then under the cut my deep dive into figuring out the different books (also: tumblrs picture cropping sucks)

Okay, PREPARE. This is a LONG post. I put screenshots of all the books i could kinda see on here. If you can figure out any more, let me know or add onto this!

now, enjoy:

a book about Ancient Egypt:

a book about Greek History

"Area 51 Fact or Fiction"

“World Mythology”, possibly “Larousse World Mythology” by Pierre Grimal

"What’s old is new again: Asgard", probably a book about New Asgard

"History of Wakanda"

“The Paradice Papers” by Merlin Stone, original on right

a book about Peru

a book about the silk road

"Rome and her Empire" by David Shotter, original on right

“Valley of the Kings” which is the royal necropolis of the New Kingdom of Egypt

some more books about Ancient Egypt

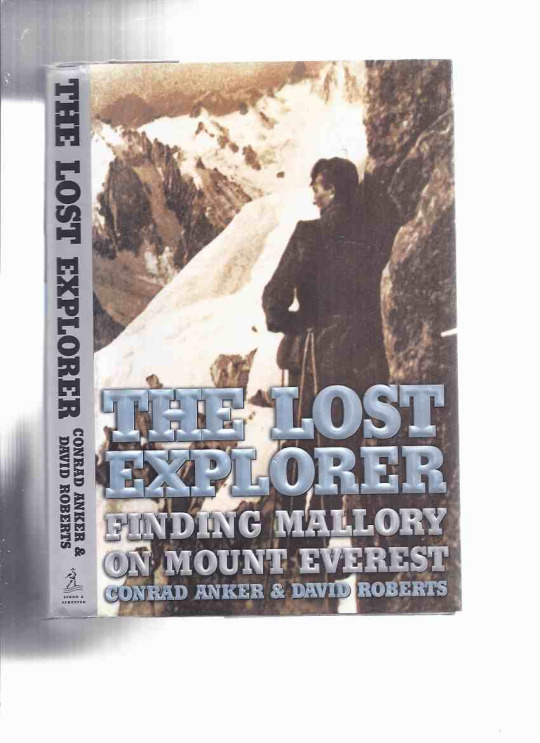

"The Lost Explorer: Finding Mallory on Mount Everest" by Conrad Anker, original on right

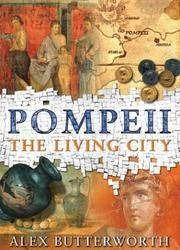

"Pompeii: The Living City" by Alex Butterworth and Ray Lawrence, original on right

“Free-Born John: A Biography of John Lilburne” by Pauline Gregg (and above it anything about anything classical), original on right

“Luther: Man Between God and the Devil” by Heiko A. Oberman (and above it one with no title or indication), original on right

- above and under 2 books i haven't figured out

“Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King” by Antonia Fraser, original on right

“The Revolution of the Dons; Cambridge and Society in Victorian England” by Sheldon Rothblatt, original on right

- under it one with only a snippet i haven't figured out

Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources, published by Penguin Classics

(thank you @sta33ington for helping with this one)

#it's currently 2am btw#i spent too long on this#my google search is full of: history book with green spine#reverse image search let me down#i am a nerd#moon knight#marvel moon knight#moon knight 2022#moon knight series#moon knight disney+#steven grant

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 Gipsies Started My Pahadi Dukan From Zero, Now Funded By OYO Founder Ritesh Agarwal Along With Many Others

The summit is what drives us, but the climb itself is what matters.” – Conrad Anker.

The mountains possess an enchanting allure that beckons to our souls, murmuring captivating tales of adventure and unexplored possibilities. And this very pull leads some to places where they transform their lives and even impact thousands of others. For one remarkable individual hailing from an average and humble background, the magnetic pull of the Himalayas proved irresistible, leading him on an extraordinary journey and he named it “my Pahadi dukan”.

The story of Himanshu Dua, who happens to be the co-founder and CEO of “My Pahadi Dukan,” which is a unique e-commerce store, is one of those real stories that have origins in the mountains and have impacted thousands of individuals living in the remotest areas of the Himalayas. It deserves to be told to the world.

It is the story of Himanshu Dua and his three friends, who were wandering to find motivation, and they found their life goal in the mountains. Today, he and his three friends, Shubham Tandon, Mohammed Anas Zubair, and Rohan Sehgal, have created a platform called ” My Pahadi Dukan” where people from far away in the mountains are able to showcase their products not only to the people living in India but also to an international audience and make a better living.

The Journey of Himanshu Dua from a Student to “My Pahadi Dukan “ Founder

Dua belongs to Bahadurgarh, which is a small town in Haryana. He graduated from the botany field and holds a master’s degree in forensic science from Delhi University. However, since his childhood, he has been exposed to travel. During his school days, he got the opportunity to visit Leh, Ladakh.

The awe-inspiring landscapes of Leh and Ladakh seemingly whisper their enchantment to him, forever captivating his heart and igniting and seeding an unwavering passion for their tranquil beauty and the simple people living there.

A Prodigy of our own, Phunsukh Wangdun( AKA “3 Idiots” famous character) institute

Apart from his degrees, he has also done 2 fellowships at the Himalayan Institute of Alternative Ladakh(HIAL), which is famous for its founder, Sonam Wangchuk, the person on whom the fictional character of Phunsukh Wangdun in the 2009 film ‘3 Idiots was conceptualized and played by Mr. Perfectionist Amiri Khan. It seems “Himanshu” took the lesson “Knowledge ke piche bhago, success jak marte huye piche aayegi” (Gain knowledge and success will come automatically) seriously and put his soul and sweat into finding something where he can make a difference in people’s lives.

How did the Idea of My Pahadi Dukan come into existence

So he came up with the idea of opening an e-commerce store dedicated to selling these hidden treasures from remote villages to domestic and international customers. This idea was original and had the power to transform people’s lives by allowing them to earn money simultaneously.

Himanshu and his co-founders felt it was a great opportunity to create something sustainable and profitable. Naturally, their first motivation was to create something to help people living in these regions. And boy, have they delivered? Today, their startup has the backing of IIT Mandi Catalyst, Mr. Ritesh Agarwal from Oyo Rooms at IIM Kashipur, and they have secured financing from the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare.

What products do they sell, and where are they sourced from?

The platform has a customer satisfaction rate of almost 98%, and they are able to dispatch their products all over the world, including India, because of their unique style of working, where they take preorders as well as deliver fruits and other products in good shape by using vacuum -free packing.

What is” My Pahadi Dukan “ aiming for in the future?

He concedes that there are challenges, and maintaining a business is not a small task. However, he thinks his ideas are noble, his efforts are honest, and he will accomplish his targets in the future. And he has no reason not to think in this manner and aim for the sky. Because his passion is pure and his purpose is noble, and with the knowledge and support of partners and co-workers, “My Pahadi Dukan” will undoubtedly fly high.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Join Meru Peak Expedition with Kahlur Adventures

At an impressive height of 6,660 meters (21,850 feet), Meru Peak is a magnificent mountain situated in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand, India. Known for its iconic Shark’s Fin route, Meru Peak has earned a reputation as one of the most challenging and rewarding climbs in the world.

For adventurers looking to test their mettle against the Himalayas, the Meru Peak Expedition offers an unparalleled experience that blends extreme mountaineering with breathtaking natural beauty.

The Allure of Meru Peak

Meru Peak 6660M India, often simply referred to as Meru Peak, is part of the Gangotri Range in the western Himalayas. Surrounded by notable peaks like Shivling, Bhagirathi, and Thalay Sagar. However, what sets Meru Peak apart is its unique and formidable Shark’s Fin route, a 1,500-meter (4,900-foot) vertical rock wall that has become a symbol of extreme mountaineering.

The Shark’s Fin gained worldwide fame through the documentary film “Meru,” which chronicles the harrowing journey of climbers Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin, and Renan Ozturk as they attempted to conquer this nearly insurmountable route.

Their successful ascent in 2011 not only marked a milestone in the history of mountaineering but also highlighted the peak's reputation as a climber’s ultimate challenge.

The Challenge of the Meru Peak Expedition

The Meru Peak Expedition is not for the faint-hearted. The climb is renowned for its technical difficulty, unpredictable weather conditions, and the sheer physical and mental endurance required to reach the summit.

The route to the top is fraught with obstacles, including steep ice slopes, challenging rock faces, and the ever-present threat of avalanches.

The Shark’s Fin route specifically challenges a climber's skill and perseverance. The vertical rock face demands advanced climbing techniques, and the thin air at high altitudes adds an extra layer of difficulty.

Despite these challenges, the Meru Peak Expedition remains a coveted achievement for mountaineers worldwide.

The Experience of a Lifetime

Reaching the summit of Meru Peak is a monumental achievement, but the journey itself is equally rewarding. As climbers ascend, they are treated to awe-inspiring views of the surrounding Himalayan peaks. The snow-capped summits against the backdrop of a deep blue sky create a visual spectacle that is both humbling and exhilarating.

The Meru Peak Expedition is more than just a physical challenge; it is a spiritual journey that takes climbers into the heart of the Himalayas. The sense of accomplishment that comes from standing atop Meru Peak, knowing that you have conquered one of the world’s most challenging climbs, is an experience that stays with you for a lifetime.

Why Choose Kahlur Adventures for Your Meru Peak Expedition?

For those seeking to embark on the Meru Peak Expedition, Kahlur Adventures is a trusted and experienced adventure tour operator. With a team of skilled guides and mountaineers, Kahlur Adventures ensures that climbers are well-prepared and supported throughout their journey. Safety is a top priority, and the company’s deep knowledge of the region and the challenges of the climb provides peace of mind for adventurers.

Kahlur Adventures offers comprehensive expedition packages that include pre-expedition training, acclimatization schedules, and logistical support. Their commitment to excellence ensures that climbers have the best possible chance of success on their Meru Peak Expedition.

Conclusion

Embarking on the Meru Peak Expedition is an extraordinary adventure that challenges both body and spirit. For those ready to take on the challenge, Kahlur Adventures stands ready to guide you on this unforgettable journey to the summit of Meru Peak.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. What is the best time to undertake the Meru Peak Expedition?

The best time for the Meru Peak Expedition is during the pre-monsoon (May to June) and post-monsoon (September to October) seasons. These periods offer more stable weather conditions, which are crucial for a successful ascent.

Q. How difficult is the Shark’s Fin route on Meru Peak?

The Shark’s Fin route is one of the most technically challenging climbs in the world. It requires advanced rock climbing skills, experience with ice climbing, and the ability to endure high-altitude conditions.

Q. What is the duration of the Meru Peak Expedition?

The Meru Peak Expedition typically takes around 20 to 25 days, including acclimatization, ascent, and descent. The exact duration can vary depending on weather conditions and the pace of the climbers.

Q. What equipment is required for the Meru Peak Expedition?

Climbers need specialized mountaineering equipment, including crampons, ice axes, ropes, harnesses, and high-altitude clothing. Kahlur Adventures provides a detailed equipment list and can assist with gear rental if needed.

Q. Is prior mountaineering experience necessary for the Meru Peak Expedition?

Yes, prior experience with high-altitude climbing and technical mountaineering is essential for the Meru Peak Expedition. The climb is extremely demanding, and climbers must be well-prepared and physically fit.

0 notes

Text

Mountain quotes and aphorisms

Quotes on mountains

Mountain quotes and aphorisms by great authors, ideas, thoughts, reflections and poetic phrases about mountains, peaks, climbs, climbers and their metaphors of life.

The ordinary man looking at a mountain is like an illiterate person confronted with a Greek manuscript.

Aleister Crowley

We cannot lower the mountain, therefore we must elevate ourselves.

Todd Skinner

I learn something every time I go into the mountains.

Michael Kennedy

Mountains are not Stadiums where I satisfy my ambition to achieve, they are the cathedrals where I practice my religion.

Anatoli Boukreev

No matter how tall the mountain is, it cannot block the sun.

Chinese Proverb

The mountain has never attracted me, in fact I have never liked to climb too high, I prefer to keep my feet more or less at sea level.

Carl William Brown

Never measure the height of a mountain until you reach the top. Then you will see how low it was.

Dag Hammerskjold

Great things are done when men and mountains meet; This is not done by jostling in the street.

William Blake

Sometimes you come up against a mountain and you end up making the mountain seem bigger than God.

Jeremy Lin

The greatest gift of life on the mountain is time. Time to think or not think, read or not read, scribble or not scribbleto sleep and cook and walk in the woods, to sit and stare at the shapes of the hills.

Phillip Connors

I like the mountains because they make me feel small. They help me sort out what's important in life.

Mark Obmascik

In every walk with nature, one receives far more than he seeks.

John Muir

When the sun is shining I can do anything; no mountain is too high, no trouble too difficult to overcome.

Wilma Rudolph

There's no glory in climbing a mountain if all you want to do is to get to the top. It's experiencing the climb itselfin all its moments of revelation, heartbreak, and fatiguethat has to be the goal.

Karyn Kusama

Mountain famous quotes

You can’t move mountains by whispering at them.

Anonymous

Every man should pull a boat over a mountain once in his life.

Werner Herzog

Mountain people are generally increasingly stingy, introverted and above all think they are better than their unfortunate colleagues on earth.

Carl William Brown

Getting to the top is optional. Getting down is mandatory.

Ed Viesturs

In the mountains there are only two grades: you can either do it, or you can’t.

Rusty Baillie

Great things are done when men and mountains meet.

William Blake

He who climbs upon the highest mountains laughs at all tragedies, real or imaginary.

Friedrich Nietzsche

If you don't have a mountain, build one and then climb it. And after you climb it, build another one; otherwise you start to flatline in your life.

Sylvester Stallone

Everyone wants to live on top of the mountain, but all the happiness and growth occurs while you’re climbing it.

Andy Rooney

The summit is what drives us, but the climb itself is what matters.

Conrad Anker

Beyond the mountains, more mountains.

Haitian proverb

I have always preferred the sea to the mountains, meaning peaks, with some exceptions for the woods, where rebels usually take refuge.

Carl William Brown

Our peace shall stand as firm as rocky mountains.

William Shakespeare

Life is a mountain of solvable problems, and I enjoy that.

James Dyson

The only Zen you can find on the tops of mountains is the Zen you bring up there.

Robert M. Pirsig

Mountains aphorisms

We've climbed the mighty mountain. I see the valley below, and it's a valley of peace.

George W. Bush

I take all day to climb mountains and then spend about 10 minutes at the top admiring the view.

Sebastian Thrun

Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far they can go.

T. S. Eliot

Always be thankful for the little things…even the smallest mountains can hide the most breathtaking views.

Nyki Mack

Somewhere between the bottom of the climb and the summit is the answer to the mystery why we climb.

Greg Child

Life's a bit like mountaineering, never look down.

Edmund Hillary

I have always preferred seaside vacations to mountain vacations, also because I see people dressed all year round, and the human circus always has a certain effect on me.

Carl William Brown

Over every mountain there is a path, although it may not be seen from the valley.

Theodore Roethke

Each fresh peak ascended teaches something.

Sir Martin Convay

Earth and sky, woods and fields, lakes and rivers, the mountain and the sea, are excellent schoolmasters, and teach some of us more than what we could learn from books.

John Lubbock

Only if you have been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.

Richard Nixon

Mountains are to the rest of the body of the earth, what violent muscular action is to the body of man. The muscles and tendons of its anatomy are, in the mountain, brought out with force and convulsive energy, full of expression, passion, and strength.

John Ruskin

Climb the mountains and get their good tidings.

John Muir

Man can climb to the highest summits, but he cannot dwell there long.

George Bernard Shaw

One may walk over the highest mountain one step at a time.

Barbara Walters

Quotes and ideas about the mountain

You don't climb mountains without a team, you don't climb mountains without being fit, you don't climb mountains without being prepared and you don't climb mountains without balancing the risks and rewards. And you never climb a mountain on accidentit has to be intentional.

Mark Udall

Your faith can move mountains and your doubt can create them.

Swami Vivekananda

I am not a revolutionary at all. Imagine the ideal society as a happy reality beyond a great mountain of stupidity. Just build a tunnel and there we are in the middle of serenity. Come on, we need explosives!

Carl William Brown

Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting, So…get on your way!

Dr. Seuss

It’s not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.

Sir Edmund Hillary

I'm a person of the mountains and the open paddocks and the big empty sky, that's me, and I knew if I spent too long away from all that I'd die; I don't know what of, I just knew I'd die.

John Marsden

Those who travel to mountain-tops are half in love with themselves, and half in love with oblivion.

Robert Macfarlane

I can't do with mountains at close quarters - they are always in the way, and they are so stupid, never moving and never doing anything but obtrude themselves.

D. H. Lawrence

The last word always belongs to the mountain.

Anatoli Boukreev

Nothing puts things in perspective as quickly as a mountain.

Josephine Tey

Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees.

John Muir

Mountains, according to the angle of view, the season, the time of day, the beholder’s frame of mind, or any one thing, can effectively change their appearance. Thus, it is essential to recognize that we can never know more than one side, one small aspect of a mountain.

Haruki Murakami

Seeing some of my acquaintances in the mountains during the Christmas holidays, I remember the good old days of university, when I had to work on holidays, always, while many of my classmates went to have fun, in the summer to the sea, and in the winter to the snow!

Carl William Brown

The choices we make lead up to actual experiences. It is one thing to decide to climb a mountain. It is quite another to be on top of it.

Herbert A. Simon

The mountains are calling, and I must go.

John Muir

Mountain short meditations

It isn't the mountain ahead that wears you out; it's the grain of sand in your shoe.

Robert W. Service

What draws us from the low valleys to the high mountains is that noble stance of the summits!

Mehmet Murat ildan

Climb the mountain not to plant your flag, but to embrace the challenge, enjoy the air and behold the view. Climb it so you can see the world, not so the world can see you.

David McCullough Jr.

Mountaineer from Brescia falls three thousand meters, he is in very serious conditions. Praise the mountains and keep to the plain!

Carl William Brown

When preparing to climb a mountain, pack a light heart.

Dan May

When faced with a large project, remember you move a mountain one stone at a time.

Catherine Pulsifer

Mountains are earth's undecaying monuments.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

The best view comes after the hardest climb.

Vanessa Gendoma

I would not exchange all the most beautiful views of nature, be they spectacular mountain, sea, plain or city scenes, for a single glance at my mother's face, serene, cheerful, but also suffering.

Carl William Brown

In the mountains, you are sometimes invited, sometimes tolerated, and sometimes told to go home.

Fred Beckey

In the mountains, you are sometimes invited, sometimes tolerated, and sometimes told to go home.

Fred Beckey

There is a world out there, and you have got to look at both sides of the mountain in your lifetime.

Bill Janklow

The mountains were his masters. They rimmed in life. They were the cup of reality, beyond growth, beyond struggle and death. They were his absolute unity in the midst of eternal change.

Thomas Wolfe

I've realized that at the top of the mountain, there's another mountain.

Andrew Garfield

We are now in the mountains and they are in us, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us.

John Muir

Mountains quotes and aphorisms

The mountains are a reminder of the power and majesty of nature, and of our own smallness in the face of it.

Ajaz Ahmad Khawaja

What are men to rocks and mountains?

Jane Austen

Once in a high school class in the mountains they asked me what I would do to people like Pacciani (the famous monster of Florence), my answer was that I would clone a dozen of them and send them right to that area.

Carl William Brown

The cliche is that life is a mountain. You go up, reach the top and then go down.

Jeanne Moreau

It isn't the mountains ahead to climb that wears you out; it's the pebble in your shoe.

Muhammad Ali

It is very tough to climb a mountain. However, it is not as tough as convincing yourself that you can climb it.

Bhuwan Thapaliya

Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal. Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood by all, but which the wise, and great, and good interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Mountains know secrets we need to learn. That it might take time, it might be hard, but if you just hold on long enough, you will find strength to rise up.

Tyler Knott

May your dreams be larger than mountains and may you have the courage to scale their summits.

Harley King

How glorious a greeting the sun gives the mountains!

John Muir

Mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery.

John Ruskin

The way up to the top of the mountain is always longer than you think. Don’t fool yourself, the moment will arrive when what seemed so near is still very far.

Paul Coelho

Mountain top: the place where life finds the purest meaning of freedom.

Vinicius Montgomery

Every mountain top is within reach if you just keep climbing.

Barry Finlay

I don't know why, but on a visual and emotional level, if I really have to choose, I prefer desert canyons with little vegetation, to lush mountains full of a flourishing and vain natural wealth.

Carl William Brown

No matter how sophisticated you may be, a large granite mountain cannot be deniedit speaks in silence to the very core of your being.

Ansel Adams

You can also read:

Quotes and ideas on vacation

Tourism and travels

Thoughts about travelling

www.officeholidays.com

www.moresailing.co.uk

Job tourism in Lombardy

Turismo enogastronomico

Trip Advisor travels

Top destinations and tours

The Lake District

Essays with quotes

Quotes by authors

Quotes by arguments

Thoughts and reflections

News and events

Read the full article

#aphorismsonmountain#mountainaphorisms#mountainquotes#quotesandaphorismsaboutthemountain#quotesonmountain

0 notes

Text

Joseph Conrad – Der Existenzkapitän

Tichy:»Das Logbuch verzeichnet: Planken aus British Understatement, rätselhafte Teilhaber am Steuerrad der großen Fragen, der Anker abgerissen, auf der Schiffsschraube das Wort Pflicht, die Mannschaft voller Narren – Feindfahrt mit Humor. Conrad lesen heißt ins Grundsätzliche reisen. So recht heimisch in der deutschen Literatur ist er nicht geworden. Liegt es an seinen Stoffen? Sie erzählen

Der Beitrag Joseph Conrad – Der Existenzkapitän erschien zuerst auf Tichys Einblick. http://dlvr.it/TBQFvw «

0 notes

Text

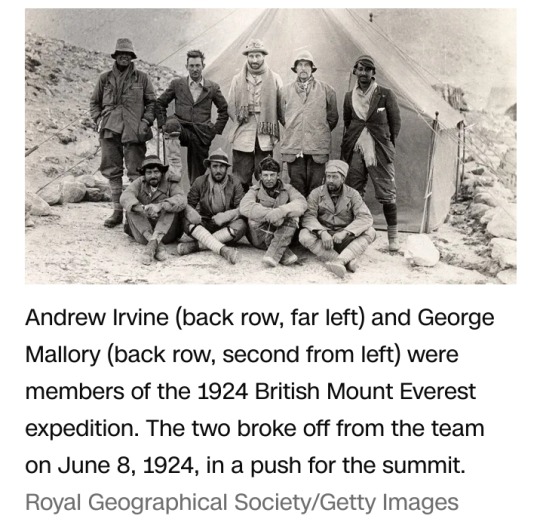

(CNN) — George Mallory is renowned for being one of the first British mountaineers to attempt to scale the dizzying heights of Mount Everest during the 1920s — until the mountain claimed his life.

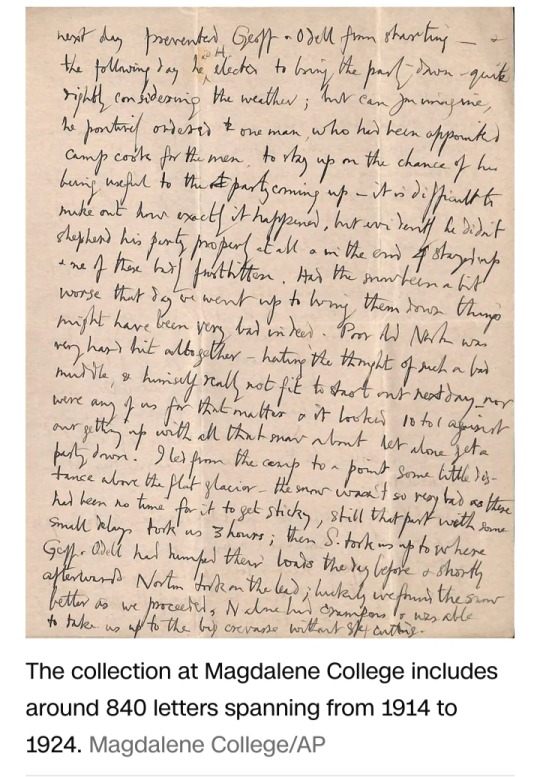

Nearly a century later, newly digitized letters shed light on Mallory’s hopes and fears about ascending Everest, leading up to the last days before he disappeared while heading for its peak.

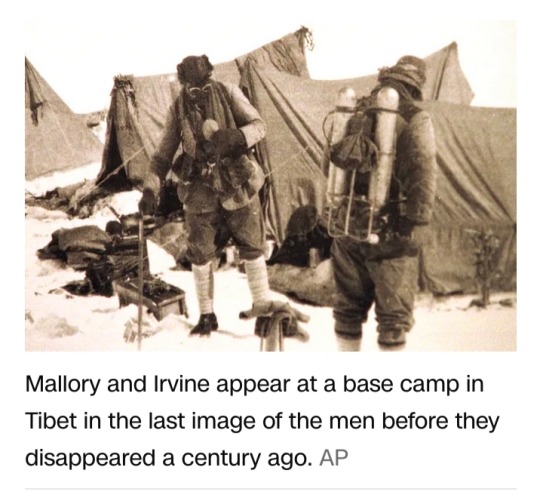

On 8 June 1924, Mallory and fellow climber Andrew Irvine departed from their expedition team in a push for the summit; they were never seen alive again.

Mallory’s words, however, are now available to read online in their entirety for the first time.

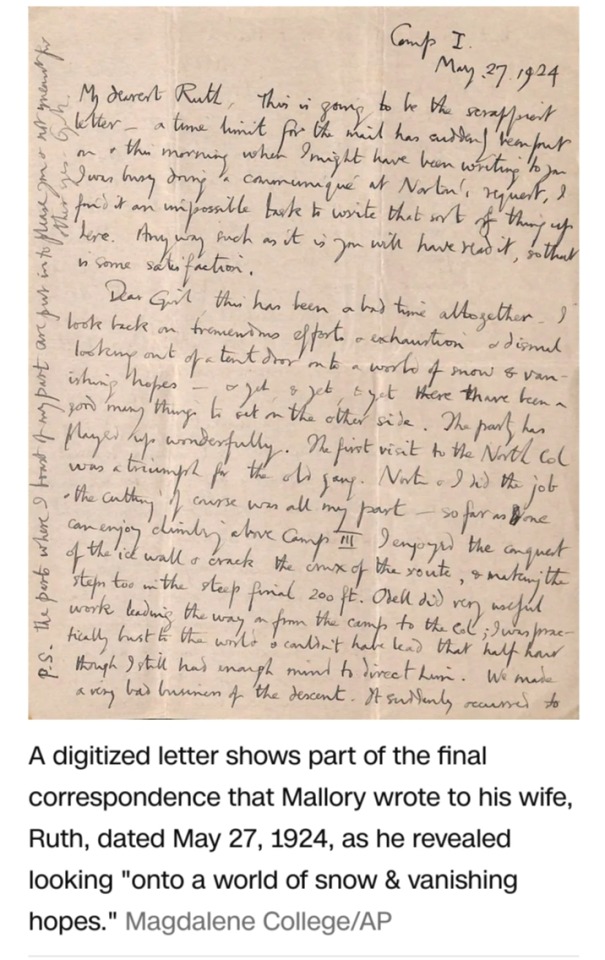

Magdalene College, Cambridge, where Mallory studied as an undergraduate from 1905 to 1908, recently digitized hundreds of pages of correspondence and other documents written and received by him.

Over the past 18 months, archivists scanned the documents in preparation for the centennial of Mallory’s disappearance.

The college will display a selection of Mallory’s letters and possessions in the exhibit “George Mallory: Magdalene to the Mountain,” opening June 20.

The Everest letters outline Mallory’s meticulous preparations and equipment tests, and his optimism about their prospects.

But the letters also show the darker side of mountaineering: bad weather, health issues, setbacks, and doubts.

Days before his disappearance, Mallory wrote that the odds were “50 to 1 against us” in the last letter to his wife Ruth dated 27 May 1924.

“This has been a bad time altogether,” Mallory wrote. “I look back on tremendous efforts & exhaustion & dismal looking out of a tent door and onto a world of snow & vanishing hopes.”

He went on to describe a harrowing brush with death during a recent climb, when the ground beneath his feet collapsed, leaving him suspended “half-blind & breathless.”

His weight supported only by his ice axe wedged across a crevasse as he dangled over “a very unpleasant black hole.”

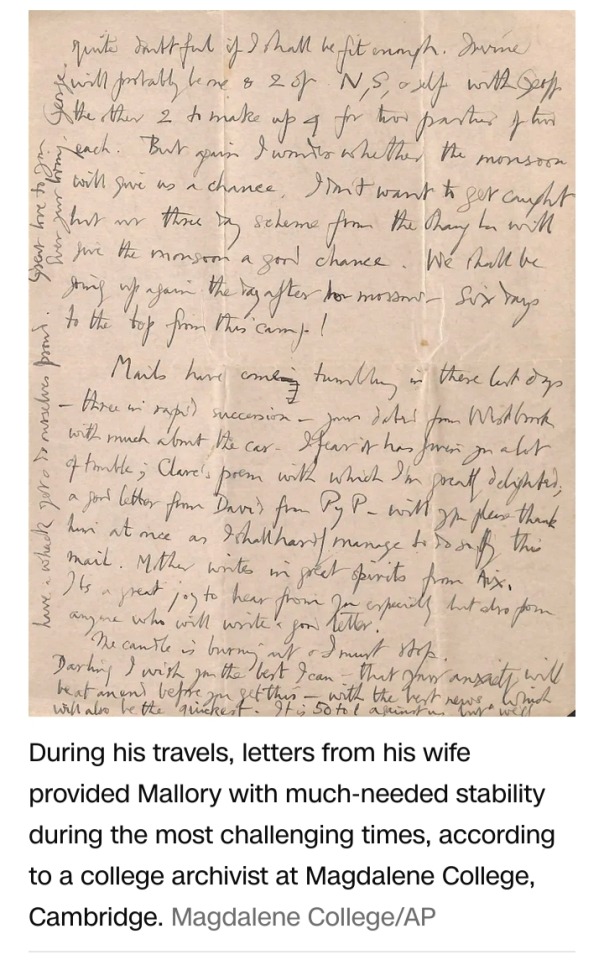

Other letters Mallory exchanged with Ruth were written at the time of their courtship, while he was serving in Britain’s artillery regiment during World War I.

Throughout his travels, correspondence from Ruth provided him with much-needed stability during the most challenging times, said project lead Katy Green, a college archivist at Magdalene College.

“She was the ‘rock’ at home, he says himself in his letters,” Green said.

The archivist recounted one note in which Mallory told Ruth: “I’m so glad that you never wobble, because I would wobble without you.”

Yet while Mallory was clearly devoted to his wife, he nonetheless repeatedly returned to the Himalayas despite her mounting fears for his safety.