#city of saints and madmen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#city of saints and madmen#jeff vandermeer#short stories#fantasy#book poll#have you read this book poll#polls#requested

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you like I Am In Eskew and The Silt Verses, why not try the Ambergris trilogy? We’ve got:

Mushrooms

Like so many mushrooms

A fucked up river full of fucked up squid

Tons of eldritch body horror

Unstable and obsessive artists tapping into unnatural forces in an attempt to communicate something that cannot be easily described in words

Magic-powered hell capitalism

Feuding historians

“I never lose my sense of the city’s incomparable splendor — it’s love of rituals, its passion for music, its infinite capacity for the beautiful cruelty.”

Names to rival even the great Chuck Harm

Awful cities that have something intrinsically yet indescribably wrong with them

Strange and unknown horrors that are omnipresent but uneasily ignored because to acknowledge them directly is too frightening to consider

Many, many characters who are sopping wet, pathetic, and/or unhinged in variously sad yet endearing ways

”it’s the silt, man! The silt!”

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

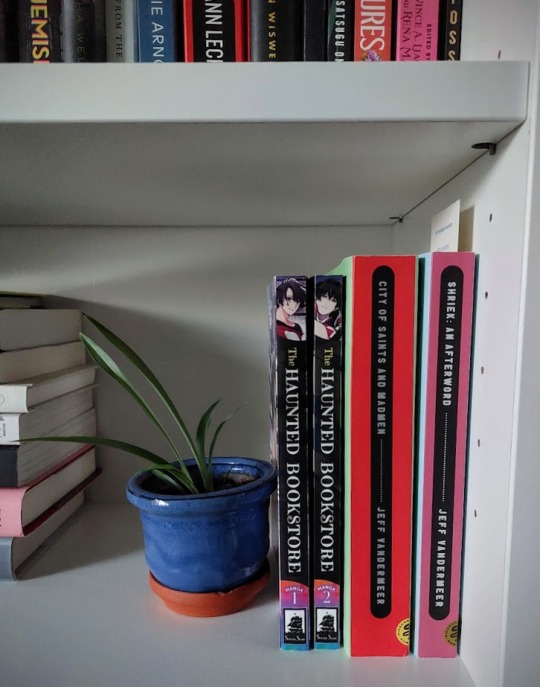

Title: City of Saints and Madmen | Author: Jeff VanderMeer | Publisher: Picador (2022)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a lovely birthday today; as always, my gift haul 🤭

(Not pictured: a whole bunch of lovely rainbow yarn)

#birthday#books#my toxic trait is putting my writing research list on my Amazon wishlist for birthday and xmas#Knitwear Club#Sheer Vale#Jeff VanderMeer#Robert Lifton#Victor Lavalle#Gotye#Going Clear#Alien Messiahs#The Ballad of Black Tom#Absolution#Southern Reach Series#City of Saints and Madmen

0 notes

Text

I am genuinely only packing two* books for a week-long trip tomorrow. It's a spring miracle.

*I will have my tablet with a truly absurd quantity of academic books and also two baby books for a shower I'm attending and also my entire manuscript to read through. But bygones.

#I had considered bringing both my english and italian southern reach trilogy copies so I could work on italian#but I don't really have the space 😔#this is what happens when you have to pack in a CARRY ON. FOR NEW ENGLAND. IN MARCH.#WHY IS IT SNOWING NEW ENGLAND. EXPLAINNNNN#it's SPRING#(I have lived in new england I am well aware that's the way the dunkin donut crumbles#but like any good new englander* I will complain the whole time)#*I am not yet a new englander but I soon will be which is part of the purpose of the trip#anyway I haven't actually decided which second book I should bring#it's gotta be fiction#I'm thinking babel but other options include city of saints and madmen which I'm still trying to finish#or the body scout by lincoln michel which is from the library so it would be helpful to work on library books#or the ninefox gambit since I haven't started that but I should#ANYWAY much to think about#tbh it'll probably be the library book on account of that being the smallest option lmao#I really do have very limited space lol

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh shit--Finch and Shriek are SIGNED??!!

this is why I love ordering from BookOutlet. I once got a signed copy of The City in the Middle of the Night too, just randomly.

#books#book haul#i didn't get city of saints and madmen cause they didn't have it (ive already read it anyway)#but! excited to give these two a second chance

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

flipping open a book that seems somewhat confusing and immediately thinking "well. this will be good practice for when i start House Of Leaves"

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need to read the traitor baru cormorant so badly, like that's the number one fantasy novel i want to read.

#other books i need to read are city of saints and madmen which is my number one weirdfic book i need to read#well actually it's house of leaves but that is scary...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surprising how I always forget Letterboxd exists given how it directly enables one of my great joys in life: being incredibly annoying about something I've just seen/watched/etc

#like I love doing it with books! finished City of Saints and Madmen and immediately went on one about how the writer was too afraid to#commit to the ideas he created#and yet! I always forget to with films#my letterboxd has I think 4 films on it. 2 were from tonight's movie night

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books of 2024: September Wrap-Up.

Delighted to report I am VERY far behind on my NaNo prep reading goals, and now September is gone (oops). However! This month I did manage to carve nine (9) pages out of a behemoth scene, write a newsletter article for the nonprofit I volunteer at, and alpha/hype read a friend's manuscript, so I still had a fairly wordy month (I say, as if all of my months are not Wordy™).

Photos/reviews linked below:

THE HAUNTED BOOKSTORE, Vol. 1 & 2 - ★★★½ These were cute! I liked them enough that I went ahead and ordered the next two volumes, and I'm glad I did--turns out there are only four manga in the series, so I'll have the whole thing :) I plan on returning to these after November/as part of Driscoll prep again, because they match the vibe I'm trying to channel really well.

CITY OF SAINTS AND MADMEN - ★★★½ (rating subject to change upon series completion) So on my shelf, this book doesn't LOOK like a brick, but it's 704 pages (according to Goodreads, because the pages in the back half of the book are not numbered sequentially lmaooo). It's told in several novellas strung together and then An Appendix full of all sorts of (sneakily?) relevant bits and pieces--fascinating anthology of a book, very meta-textual. It grew on me! If you can get through the first story, it's worth sticking with, and the whole series is turning into a puzzle box. And speaking of...

SHRIEK: AN AFTERWORD - 135/451 pages read; will report back later. I definitely had to dual wield CITY and SHRIEK last night to compare passages that are, in fact, duplicated across books, and I feel like the calculus meme about it. This one is structured interestingly, too: It's written by a sister (first person) about her brother, but the brother is annotating her manuscript in his own first person (in parentheticals wedged into or tacked onto paragraphs, also first person). I'm very excited to finish this, and equally excited to see what's going on with FINCH after that, so. Back to reading I go!!

Under the Cut: A Note About ~*★Stars★*~

Historically, I have been Very Bad™ about assigning things Star Ratings, because it's so Vibes Heavy for me and therefore Contingent Upon my Whims. I am refining this as I figure out my wrap up posts (epiphany of last month: I don't like that stars are Odd, because that makes three the midpoint and things are rarely so truly mid for me)(I have hacked my way around this with a ½). Here is, generally, how I conceptualize stars:

★ - This was Bad. I would actively recommend that you do NOT read this one, no redeeming qualities whatsoever, not worth the slog. Save Yourself, It's Too Late For Me. Book goes in the garbage (donate bin).

★★ - This was Not Good. I would not recommend it, but it wasn't a total waste or wash--something in here held my interest/kept my attention/sparked some joy. I will not be rereading this ever. Save Yourself (Or Join Me In Suffering, That Seems Like A Cool Bonding Activity).

★★★ - This was Good/Fine/Okay/Meh. I don't care about this enough to recommend it one way or another. Perfectly serviceable book, held my interest, I probably enjoyed myself (or at least didn't actively loathe the reading). I don't have especially strong feelings. You probably don't need to save yourself from this one--if it sounds like your jam, give it a shot! Just didn't resonate with me particularly powerfully. I probably won't reread this unless I'm after something in particular.

★★★½ - I liked this! I'll probably recommend it if I know it matches someone's vibes or specific requests, but I didn't commit to a star rating on Goodreads. More likely to reread, but not guaranteed.

★★★★ - I really enjoyed this!! I would recommend it (sometimes with caveats about content warnings or such--I tend to like weird fucked up funny shit, and I don't have many hard readerly NO's). Not a perfect book for me by any means, but Very Good. This is something I would reread! Join me!!

★★★★★ - I LOVED THE SHIT OUT OF THIS, IT REWIRED MY BRAIN, WILL RECOMMEND TO ANYONE AND EVERYONE AT THE SLIGHTEST PROVOCATION (content warning caveats still apply--see 4-star disclaimer). Excellent book, I'll reread it regularly, I'll buy copies for all my friends, I'll try to convince all of Booklr to read it, PLEASE join me!!

#books of 2024#books of 2024: september wrap-up#the haunted bookstore#ambergris trilogy#jeff vandermeer#city of saints and madmen#shriek: an afterword#shriek#the more of these wrap ups i do the more i realized i picked THE ABSOLUTE WORST TIME TO START THEM btw#like i've definitely read 46 books so far this year total#so averaging more than one a week by a fairly significant margin#and YET: the past two months i've only finished three (3)#because i keep nerfing myself with bricks (le guin and vandermeer respectively)#and because i've figured out the writing groove again a little better lol#anyway i wanted to have already finished reading a bunch of my haunted house books so those could be marinating right now#but instead i'm staring at them several books out on my shelf still#so i might be taking a couple weeks to do a lot of reading and prep a book in two lmao#i might be able to do the human/earthling character prep now and just save the house for after i read more haunted house stuff#i want to be swimming in a sea of Ideas and i'm not quite there yet#making gr8 progress on the fungus front though so that counts for something#adhd really is feeling like you're behind all the damn time huh

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

February Reading Recap

Mostly I read Wheel of Time last month. And by that I mean I reread the first nine books of Wheel of Time last month. (I finished the 10th one yesterday morning.)

So this is a pretty short list because providing a recap of my Wheel of Time reactions per book feels a little facetious to me for some reason, probably because I've read all of them going on five times at this point and my impressions thereof remain pretty consistent across those reads.

I will say that I think my favorites of the first nine books are probably The Shadow Rising, The Fires of Heaven, and A Crown of Swords, even if Lord of Chaos does get special mention for the Enboxening.

The Atlas Paradox and The Atlas Complex by Olivie Blake. My feelings about this series sort of...deteriorated as it went on. I thought the first book was good, noticed some flaws but overall enjoyed the second book, and by the third the author's writing tics and particular habits were starting to wear on me. I don't know if this was a matter of exposure, like listening to a podcast too fast and becoming excruciatingly overaware of every one of the host's verbal tics, or if the series itself actually got worse, but...

I gathered from perusing a few reviews that some peoples' objections to the last book in particular were plot-related, which actually wasn't my problem; my problem had more to do with a certain air of self-important self-consciousness to the writing style itself that only became more apparent over the course of the series. Blake's writing went from slightly overwritten but in a way that felt fun to thinking it was truly innovative prose (it wasn't). Overall I don't regret reading the series but I probably wouldn't recommend it either.

Absolution by Jeff Vandermeer. I don't think one needs to reread the other Area X books in order to read this one but I suspect I might've gotten more out of it if I had; I think I am going to do a reread at some point in the not-too-distant future.

I liked this book more than I've liked the other Vandermeers I've read more recently, but I think it did also confirm for me that I just prefer Vandermeer's earlier work (City of Saints and Madmen in particular) to his more recent writing. Maybe that makes me basic or unsophisticated (I have a sneaking suspicion) but it is what it is. Still, this was a weird, surreal ride that resists clear allegorization and I do appreciate that for it.

Incidents Around the House by Josh Malerman. I read Bird Box recently and was pleasantly surprised by how much I liked it, so I picked this one up on a whim as a recent horror that looked like it might have potential. I wasn't sure about the conceit at the beginning (narrated by a child, played to the hilt stylistically as well), but I think Malerman handled it fairly well...it was putting a lot of weight of the story itself on that single conceit, though, and I don't think I came out of it impressed overall. It was fine? But it's not going to stick with me, and as far as 'profoundly unreliable narrator horror novels' I read another one recently I liked more (The September House).

The Failures by Benjamin Liar. I read the acknowledgments after finishing this book (I sometimes do) and the Bas-Lag books by China Mieville were mentioned, which made me do a serious doubletake (and also go 'huh I should reread those' but that's beside the point). I can see it, though - a blurb on the back also compared this book to Jeff Vandermeer's early work, which has a certain resonance too, though I think both other authors are better writers. I'm compelled by this start to a series, for sure! I definitely plan to follow where it goes. It's different from anything else I've read recently; the way it wove together distinct narrative threads out of order without making it clear what their precise order was until late in the game was very well done.

The only negative reaction I had here was to something that also twigged me about Nevernight by Jay Kristoff when I read it (though to a lesser degree here) which is the sense of a writer's narrative voice being a little too taken with its own cleverness. A wry, arch narrative voice can be a lot of fun done well, but if it's not handled impeccably at least for me it can just become grating. While Liar didn't quite reach that point in this book, it's something I was quite aware of and the main detraction from my enjoyment of the work as a whole.

A Song to Drown Rivers by Ann Liang. I was excited to trip over this one, because I haven't seen any retellings about characters/figures from Chinese classic literature, but I probably shouldn't be surprised that I was a little disappointed - and in this case I think knowing the source material better might've just made that worse. It wasn't bad, but it wasn't particularly exceptional either: a lightweight novel, without a lot of depth of character, writing, or plot. It was fairly fun, I read it in an afternoon, I can't say much more for it than that. I do hope that its existence heralds possibly more retellings about characters/figures from Chinese classic literature, though, because I probably will read those.

I also wanted more politics and less romance, though that may partly be on me for "shoulda known better" syndrome.

---

Currently reading Trickster Makes This World by Lewis Hyde, which has been on my shelf approximately forever. This will be followed by continuing my Wheel of Time reread, alternating with reading other books because I don't want to just. Mainline fourteen books of one series in three months, even though I could definitely do that.

Not sure what those books are going to be at this point, though. I'm first in holds line for The Hands of the Emperor by Victoria Goddard and A Rome of One's Own by Emma Southon, but I'm also eyeing reading The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories (a short story collection of Chinese SFF) or possibly (finally) How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell. We shall see.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

If you are doing book recs, I was wondering if you had any for sci-fi that deals with sociology, archeology, anthropology - mostly those kinds of sciences. Ursula Le Guin's work is my favorite example of this, so do you know anything similar to The Left Hand of Darkness?

Or, if not, do you have any recs for nature/climate sci-fi, such as The Southern Reach trilogy? Thank you so much!

hello! i'm always open to book recs, thanks for the message :)

first, for sf + social sciences:

Renee Gladman, Event Factory - an epistemological crisis is an ontological one. mischief and other weirdness ensues.

Ted Chiang - honestly all of his work, but here's Stories of Your Life and Others

Jeff VanderMeer, City of Saints and Madmen (there's...a lot to unpack here, but I think you'll like it)

Becky Chambers, The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet. Chambers is what would happen is UKLG and Octavia Butler had glorious gay sex.

China Miéville, The City and the City. This, and Embassytown, are literary research questions and tongue-twisters.

Connie Willis, Doomsday Book - a lighthearted take on the themes you mention.

now, for cli-fi. know that I have read literal thousands of books over the course of my life atp, and have never found something that made me feel the way Annihilation made me feel. ever.

so, here's some cli-fi, but if you're looking for Southern Reach, you may be due for a re-read (or are waiting, like me, for the fourth entry to actually come out!!! which it is !!!)

Sequoia Nagamatsu, How High We Go in the Dark

Sequoia Nagamatsu, Where We Go When All We Were is Gone

C. Pam Zhang, Land of Milk and Honey

There's also more VanderMeer to explore! I'm currently reading and loving Dead Astronauts. I also loved Veniss Underground.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm happy with the progress of my Dead Astronauts playlist but still want to search for songs that are more representative of individual characters.

In the meantime I've read and finished The Strange Bird. What a sad, moving story. It's book 1.5 of the Borne series so you could read it before Dead Astronauts but it easily could be read as book 2.5.

Happy I finished that series and now I can move onto the rest of VanderMeer's backlist. Not sure if I'll read Hummingbird Salamander or City of Saints and Madmen first. Probably will start both and see which one pulls me in.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was going to pack two books. I decided on a whim that I was also going to bring a third. I found out that Murakami's Novelist as a Vocation is finally in paperback, so now I have that as well.

I am always, if nothing else, painfully on brand.

#the pain is in my shoulders#for the record the other books are: city of saints and madmen. speak bird speak again. and marx for cats.#look i had wanted the murakami book for a minute but i knew i was gonna get through it in like 3 hours#and the hardcover was a solid 35 bucks at the local bookstore#anyway.#megs is reading

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

(eisoj5 here, lol) dealer's choice about season of mists!!

dear @eisoj5! thank you for this ask! my dealer's choice fact about season of mists is that I actually made lists of all the titles on nearly every one of the themed shelves in Edwin's bookshop. I could go on about any one of them but I'm going to list one of my personal favourites, the Mushroom Shelf:

Black Mould by Ben Aaronovitch

Ghost Music by An Yu

The Girl with All the Gifts and The Boy on the Bridge by M. R. Carey

Close Encounters of the Fungal Kind by Richard Fortey

Deep Waters by William Hope Hodgson

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher

The Way Through the Woods by Litt Woon Long

Fruiting Bodies, and Other Fungi by Brian Lumley

Severance by Ling Ma

Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The Fall of the House of Usher by Edgar Allan Poe

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard

Mycelium Running by Paul Stamets

Rosewater by Tade Thompson

The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Tsing

City of Saints and Madmen, Shriek: An Afterword, and Finch by Jeff VanderMeer (VanderMeer's Southern Reach quartet also appears on the Lighthouse Shelf)

(from the end-of-year Director's Cut game (ask me for additional lore or meta about any of my fics this year)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

DARKWING DUCK IN: killer klowns from outer space

In the city of saint canard it was Halloween night, and somewhere a Halloween festival was held, there were games, food, rides, haunted houses and Halloween expo displaying scary props and costumes and creepy animatronics.

Inside the expo, launchpad was terrified by the props and animatronics.

"Ugh, ah" launchpad flinched from his left and right, animatronic clowns and creepy girl props scared him.

Drake was there with his adopted daughters: gosayln and morgana to which the girls find the expo thrilling.

Drake takes launchpad's arm and pats it to comfort him.

"It's ok launchpad, it's not real, see" Drake shows him a fake spider.

"I know it's just my first Halloween, everything seems so real"

"You practically spend your entire Halloween thinking you put a curse on duckberg, how clueless are you" morgana says.

"Morgana!" Drake scolds her.

"You know what I like best about Halloween" gosayln asked looking up at the sky as they exit the expo.

"Hmm? The free candy" Morgana asked taking a candy apple.

"No, the costume, you get to be whoever you want, ever costume tells a story"

But during the walk, launchpad was on the edge with the creepy Halloween stuff.

And just as he was in a panic, "hey launchpad" Morgana called him, he turns around and gets terrified by her creepy mask.

"AH!" He went out screaming while Morgana laughed.

"Launchpad! Morgana!" Drake sighs in frustration.

Then a creepy maze catches gosayln's eye, "ok stay right here I'm gonna go get launchpad and try to calm him down" Drake tells her.

"Ok, I'm gonna go check out that maze dad"

"Alright just be careful sweetie" so Drake ran after launchpad.

Then gosayln heads inside the scare maze, in the maze was a labyrinth and each turn was a jumpscare such as: scarecrow, witch, werewolf, demon possession, a madmen with a chainsaw or axe, a killer, someone being sacrificed, zombies, vampire or some red glowing eyes peeking behind the corn maze.

But whatever the jumps are is, it didn't scare gosayln, she passes by pretending to yawn or wasn't impressed or whenever something jumps out to scare her, she didn't flinch or screamed.

A hockey mask killer with a machete jumping right in front of her.

"Got anything better" she turns.

"And cue the freakish red demon" she points out to the demon jumping out right on time but she showed no interest and moves on.

"Got anything better" she asked but up ahead she noticed a tall shadowy figure at her direction.

"And what's your story: a stalker into little girls" gosayln asked the actor but he didn't respond.

So gosayln turned but as she walked, she heard footsteps, turning around she saw no one so she continued.

But then she hears the footsteps again, she turns and she heard running footsteps, she turns to find rustling in the cornfield, she thought it was nothing at first, thought it was part of the maze.

"Ok very funny, but I'm not scared" she went back to walking but she heard footsteps again, it started to make her feel a little scared.

and looking back she sees someone falling her, so she immediately started to run, she was now scared.

As she hears the footsteps getting closer she tried to outrun or lose the figure.

She stopped as she gets trapped, she then turns around looking at the sounds of rustling leaves.

"Ok this isn't funny anymore, this is become really scary now" she tells, waiting for a response, no one says anything, but she felt someone was following her, shaking she banks up.

But then she bumps into someone, she feels something behind her as her hand moves and trembles, she up to see...

A clown was looking down at her, she was so scared, she fainted on the ground.

When she woke up, she saw she was in drake's arms who seemed concerned and lots of people gather looking worried.

"Gosayln are you alright?" Drake asked.

Gosayln tried to speak but was to scared stuttered in words, then she looks around.

"Hey,hey it's ok, what happened" Drake asked.

But then she sees the clown that scared her,he took his ask off to reveal it was just an actor, who seemed nervous.

"AH!" Then gosayln had a panic attack, she holds on to Drake and screams.

"Whoa hey, it's ok" Drake holds her, shielding her face.

Everyone muttered at her and he sees the clown that scared her.

He covers her and glares at the crowd and the clowns, "GET OUT OF HERE"

After the fiasco night, the news came on, showcasing after the panicked attack.

"In local news a girl was traumatized at last night Halloween maze, the go to seems to be the adopted daughter of famous movie actor Drake mallard who delayed any comment"

As the reporter went on launchpad and Morgana were watching the news, while gosayln was hearing upstairs in her room, she was upset when Drake was leaning against her door concerned.

"Hey you ok" he walks in.

"Not really, I felt like I embarrassed the family"

"Look don't worry about it ok, these things happen" Drake sits besides her.

"You don't get it, I'm supposed to be the daughter of Darkwing and yet I'm afraid of something as stupid as clowns"

"It's not stupid, lots of people are afraid of clowns"

But he could see she wasn't feeling better, "I hope you don't mind me asking but why are you afraid clowns"

"Well I was a little girl grandpa took me to see the circus, it was amazing at first but after the show I saw something in the sky, it was a red balloon but o got distracted that I lost grandpa I got so worried and went to the backstage to go find him but all I saw were clowns, they had these painted faces, colorful costumes and props, it was funny at first but then they started getting closer, hoarding in on me, I got so scared but the time grandpa found me, the damage was already done, he found me in a closet terrified, so that's why I'm afraid of clowns I know it sounds stupid but-"

"Hey hey it's ok I understand it's normal to have fears, everyone gets afraid sometimes"

"But not you, you're Darkwing duck"

"At night yes, but sometimes even Darkwing duck gets scared too"

After a brief moment of silence, he checks his watch,hey listen I have to go on patrol now ok, I'll be back so you be careful ok"

He heads to door and looks back and kisses her forehead.

"And remember it's not weakness to be afraid" he heads out.

#darkwing duck reboot#ducktales#dt 2017#ducktales reboot#gosalyn mallard#gosalyn waddlemeyer#drakepad#horror#killer klowns from outer space#crossover

12 notes

·

View notes