#capital markets corporate lawyer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Trilegal: Your Capital Markets Corporate Legal Experts

Trilegal capital markets corporate lawyers offer a comprehensive range of services, advising on equity and debt capital market transactions. From initial public offerings to overseas listings, we assist companies in issuing equity and equity-linked instruments, including preferential issues and private placements. With extensive experience in business trust and REIT transactions in India and Singapore, our team ensures expert guidance and seamless execution for your capital market endeavors.

#capital markets corporate lawyer#Full service law firm#Most recognized law firm in India#trilegal india

0 notes

Text

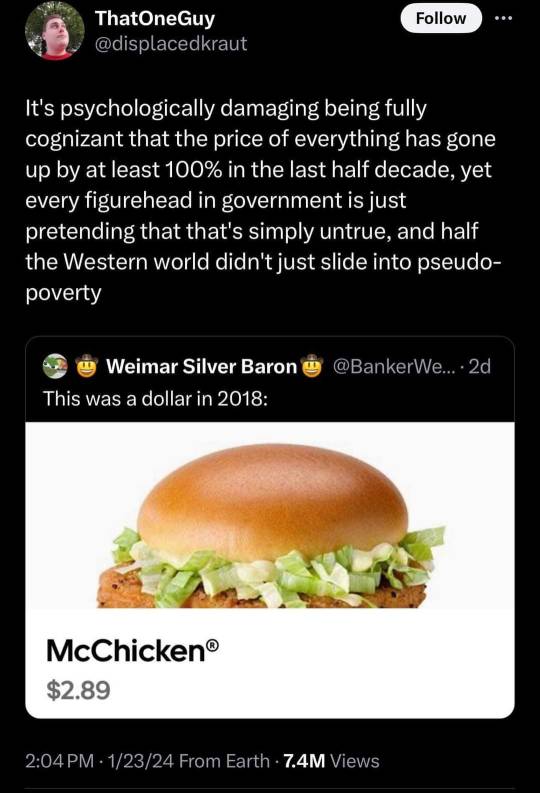

All of this said, remember that economic metrics (including price of goods at market) often are bundles (aggregates) of all economics activity that fits certain criteria. So, in other words, a change in one area will affect a portion or sector of the economy. But also, it affects the whole (even if slight). And this is on multiple levels economically, due to multiple companies all trying to operate and dominate over each other in all industries. This is further amplified by tiered types of products (economy, value sized, premium, luxury, quick service vs fine dining, etc.)

Example: food prices have risen generally. Like @weshallbekind said, certain foods increase some don't. Gas and certain new cars have higher prices, some haven't. Of course something like gas, however, is an everyday good, as are many food items. These essential items having increased prices is a component of inflation (as are interest rates, unemployment, speculation booms, currency changes, etc. different rant though). Again, aggregates, so potentially many factors. But aggregates don't reflect capitalism's main goal. Instead these aggregates are used as tools to accomplish said goal.

Keep in mind, however, that this is why capitalism like ours inherently doesn't work. It seeks to minimize costs (see also: not paying for enough workers, vertical integration, flip flopping between self check out and cashiers, moving/outsourcing, and raising prices [despite having massive economies of scale and the ability to negotiate]) for the benefit of profit. Not progress and profit, not progress, not satisfying the customers needs and wants; profit.

What does this mean then? It means profit over everything, while also creating desires in you (via marketing) to buy things you don't really need (mostly) or into which you invest your personality, time, or data. But mostly your money. Now, of course, everyone needs food, shelter, miscellaneous tools and safeguards, etc. Now those things are regulated to some degree, but nonetheless goods sold and marketed to you to profit.

Therefore, anything to make profit and make you buy it regularly could at least be attempted. Pay undocumented citizens pennies on the dollar so you don't have to give them benefits, minimum wage, or rights, check. Purposefully not include the charger and cable needed to use the phone, check. Use surge pricing to maximize profit and stress the existing infrastructure (human or otherwise), check. Overcharge you for literally the same exact product by calling it something fancy and putting their label on it, check.

And sure, of course costs increase. Of course paying people more means higher costs, especially if "times are tough". You know what takes more priority, usually, though? Executive compensation ratios, cash reserves, market dominance, mergers and acquisitions, vertical integration, lobbying, tax benefits.

Once again, let me remind you: metrics are aggregates, statistics, and computations based on demand, supply, input costs, interest rates, taxes, preferences, laws, availability of resources, currency exchange rates, speculation booms, etc. All these metrics and their formulas, however, are used (by corporations) to find their way to massive profits. By using these metrics in manipulating the market and their business practices, they're working to profit; they're striving for greater capital than the next company. Always.

#also#technically i would call USA capitalism corporatism#Adam Smith wasn't talking about Amazon when he talked about markets#he was talking about literal open air markets where you sell to the customer their daily necessities#small corporations (like my dad is a small town private practice lawyer) are fine#not companies that own most of their competition and lobby government#like im all for a free market with regulation clear effective and fair tax structures#I'm also down for small businesses and larger business agreements or alliances#also co-ops non-profits whatever#but no corporations#my dad isn't lobbying congress or manipulating stock prices#he's just a guy who wants to make sure he and his family can enjoy their life

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

Finance and and debt capital market law firm practice is a cornerstone of our firm, Elixir Legal services. Our private equity clients include public and private corporations, national and state banks, funds of all sizes, small business development, and investment companies. Having represented both lenders and borrowers, we have an in-depth understanding and extensive experience as a fairly established capital market law firm in Mumbai.

#Best Capital Markets Law firm In Mumbai#capital markets corporate law firm in mumbai#debt capital markets lawyer in mumbai#best law firms for capital markets in mumbai#capital markets attorney in mumbai#best capital markets law firms in mumbai#capital markets lawyer in mumbai#capital markets law firm in mumbai#financial markets lawyer in mumbai#equity capital markets lawyer in mumbai#top capital markets law firms in mumbai

0 notes

Text

F.6.3 But surely market forces will stop abuses by the rich?

Unlikely. The rise of corporations within America indicates exactly how a “general libertarian law code” would reflect the interests of the rich and powerful. The laws recognising corporations as “legal persons” were not primarily a product of “the state” but of private lawyers hired by the rich. As Howard Zinn notes:

“the American Bar Association, organised by lawyers accustomed to serving the wealthy, began a national campaign of education to reverse the [Supreme] Court decision [that companies could not be considered as a person]… . By 1886, they succeeded … the Supreme Court had accepted the argument that corporations were ‘persons’ and their money was property protected by the process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment … The justices of the Supreme Court were not simply interpreters of the Constitution. They were men of certain backgrounds, of certain [class] interests.” [A People’s History of the United States, p. 255]

Of course it will be argued that the Supreme Court is chosen by the government and is a state enforced monopoly and so our analysis is flawed. Yet this is not the case. As Rothbard made clear, the “general libertarian law code” would be created by lawyers and jurists and everyone would be expected to obey it. Why expect these lawyers and jurists to be any less class conscious then those in the 19th century? If the Supreme Court “was doing its bit for the ruling elite” then why would those creating the law system be any different? “How could it be neutral between rich and poor,” argues Zinn, “when its members were often former wealthy lawyers, and almost always came from the upper class?” [Op. Cit., p. 254] Moreover, the corporate laws came about because there was a demand for them. That demand would still have existed in “anarcho”-capitalism. Now, while there may nor be a Supreme Court, Rothbard does maintain that “the basic Law Code … would have to be agreed upon by all the judicial agencies” but he maintains that this “would imply no unified legal system”! Even though ”[a]ny agencies that transgressed the basic libertarian law code would be open outlaws” and soon crushed this is not, apparently, a monopoly. [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 234] So, you either agree to the law code or you go out of business. And that is not a monopoly! Therefore, we think, our comments on the Supreme Court are valid (see also section F.7.2).

If all the available defence firms enforce the same laws, then it can hardly be called “competitive”! And if this is the case (and it is) “when private wealth is uncontrolled, then a police-judicial complex enjoying a clientele of wealthy corporations whose motto is self-interest is hardly an innocuous social force controllable by the possibility of forming or affiliating with competing ‘companies.’” [Wieck, Op. Cit., p. 225] This is particularly true if these companies are themselves Big Business and so have a large impact on the laws they are enforcing. If the law code recognises and protects capitalist power, property and wealth as fundamental any attempt to change this is “initiation of force” and so the power of the rich is written into the system from the start!

(And, we must add, if there is a general libertarian law code to which all must subscribe, where does that put customer demand? If people demand a non-libertarian law code, will defence firms refuse to supply it? If so, will not new firms, looking for profit, spring up that will supply what is being demanded? And will that not put them in direct conflict with the existing, pro-general law code ones? And will a market in law codes not just reflect economic power and wealth? David Friedman, who is for a market in law codes, argues that ”[i]f almost everyone believes strongly that heroin addiction is so horrible that it should not be permitted anywhere under any circumstances anarcho-capitalist institutions will produce laws against heroin. Laws are being produced on the market, and that is what the market wants.” And he adds that “market demands are in dollars, not votes. The legality of heroin will be determined, not by how many are for or against but how high a cost each side is willing to bear in order to get its way.” [The Machinery of Freedom, p. 127] And, as the market is less than equal in terms of income and wealth, such a position will mean that the capitalist class will have a higher effective demand than the working class and more resources to pay for any conflicts that arise. Thus any law codes that develop will tend to reflect the interests of the wealthy.)

Which brings us nicely on to the next problem regarding market forces.

As well as the obvious influence of economic interests and differences in wealth, another problem faces the “free market” justice of “anarcho”-capitalism. This is the “general libertarian law code” itself. Even if we assume that the system actually works like it should in theory, the simple fact remains that these “defence companies” are enforcing laws which explicitly defend capitalist property (and so social relations). Capitalists own the means of production upon which they hire wage-labourers to work and this is an inequality established prior to any specific transaction in the labour market. This inequality reflects itself in terms of differences in power within (and outside) the company and in the “law code” of “anarcho”-capitalism which protects that power against the dispossessed.

In other words, the law code within which the defence companies work assumes that capitalist property is legitimate and that force can legitimately be used to defend it. This means that, in effect, “anarcho”-capitalism is based on a monopoly of law, a monopoly which explicitly exists to defend the power and capital of the wealthy. The major difference is that the agencies used to protect that wealth will be in a weaker position to act independently of their pay-masters. Unlike the state, the “defence” firm is not remotely accountable to the general population and cannot be used to equalise even slightly the power relationships between worker and capitalist (as the state has, on occasion done, due to public pressure and to preserve the system as a whole). And, needless to say, it is very likely that the private police forces will give preferential treatment to their wealthier customers (which business does not?) and that the law code will reflect the interests of the wealthier sectors of society (particularly if prosperous judges administer that code) in reality, even if not in theory. Since, in capitalist practice, “the customer is always right,” the best-paying customers will get their way in “anarcho”-capitalist society.

For example, in chapter 29 of The Machinery of Freedom, David Friedman presents an example of how a clash of different law codes could be resolved by a bargaining process (the law in question is the death penalty). This process would involve one defence firm giving a sum of money to the other for them accepting the appropriate (anti/pro capital punishment) court. Friedman claims that ”[a]s in any good trade, everyone gains” but this is obviously not true. Assuming the anti-capital punishment defence firm pays the pro one to accept an anti-capital punishment court, then, yes, both defence firms have made money and so are happy, so are the anti-capital punishment consumers but the pro-death penalty customers have only (perhaps) received a cut in their bills. Their desire to see criminals hanged (for whatever reason) has been ignored (if they were not in favour of the death penalty, they would not have subscribed to that company). Friedman claims that the deal, by allowing the anti-death penalty firm to cut its costs, will ensure that it “keep its customers and even get more” but this is just an assumption. It is just as likely to loose customers to a defence firm that refuses to compromise (and has the resources to back it up). Friedman’s assumption that lower costs will automatically win over people’s passions is unfounded as is the assumption that both firms have equal resources and bargaining power. If the pro-capital punishment firm demands more than the anti can provide and has larger weaponry and troops, then the anti defence firm may have to agree to let the pro one have its way. So, all in all, it is not clear that “everyone gains” — there may be a sizeable percentage of those involved who do not “gain” as their desire for capital punishment is traded away by those who claimed they would enforce it. This may, in turn, produce a demand for defence firms which do not compromise with obvious implications for public peace.

In other words, a system of competing law codes and privatised rights does not ensure that all individual interests are meet. Given unequal resources within society, it is clear that the “effective demand” of the parties involved to see their law codes enforced is drastically different. The wealthy head of a transnational corporation will have far more resources available to him to pay for his laws to be enforced than one of his employees on the assembly line. Moreover, as we noted in section F.3.1, the labour market is usually skewed in favour of capitalists. This means that workers have to compromise to get work and such compromises may involve agreeing to join a specific “defence” firm or not join one at all (just as workers are often forced to sign non-union contracts today in order to get work). In other words, a privatised law system is very likely to skew the enforcement of laws in line with the skewing of income and wealth in society. At the very least, unlike every other market, the customer is not guaranteed to get exactly what they demand simply because the product they “consume” is dependent on others within the same market to ensure its supply. The unique workings of the law/defence market are such as to deny customer choice (we will discuss other aspects of this unique market shortly). Wieck summed by pointing out the obvious:

“any judicial system is going to exist in the context of economic institutions. If there are gross inequalities of power in the economic and social domains, one has to imagine society as strangely compartmentalised in order to believe that those inequalities will fail to reflect themselves in the judicial and legal domain, and that the economically powerful will be unable to manipulate the legal and judicial system to their advantage. To abstract from such influences of context, and then consider the merits of an abstract judicial system.. . is to follow a method that is not likely to take us far. This, by the way, is a criticism that applies…to any theory that relies on a rule of law to override the tendencies inherent in a given social and economic system” [Op. Cit., p. 225]

There is another reason why “market forces” will not stop abuse by the rich, or indeed stop the system from turning from private to public statism. This is due to the nature of the “defence” market (for a similar analysis of the “defence” market see right-“libertarian” economist Tyler Cowen’s “Law as a Public Good: The Economics of Anarchy” [Economics and Philosophy, no. 8 (1992), pp. 249–267] and “Rejoinder to David Friedman on the Economics of Anarchy” [Economics and Philosophy, no. 10 (1994), pp. 329–332]). In “anarcho”-capitalist theory it is assumed that the competing “defence companies” have a vested interest in peacefully settling differences between themselves by means of arbitration. In order to be competitive on the market, companies will have to co-operate via contractual relations otherwise the higher price associated with conflict will make the company uncompetitive and it will go under. Those companies that ignore decisions made in arbitration would be outlawed by others, ostracised and their rulings ignored. By this process, it is argued, a system of competing “defence” companies will be stable and not turn into a civil war between agencies with each enforcing the interests of their clients against others by force.

However, there is a catch. Unlike every other market, the businesses in competition in the “defence” industry must co-operate with its fellows in order to provide its services for its customers. They need to be able to agree to courts and judges, agree to abide by decisions and law codes and so forth. In economics there are other, more accurate, terms to describe co-operative activity between companies: collusion and cartels. These are when companies in a specific market agree to work together (co-operate) to restrict competition and reap the benefits of monopoly power by working to achieve the same ends in partnership with each other. By stressing the co-operative nature of the “defence” market, “anarcho”-capitalists are implicitly acknowledging that collusion is built into the system. The necessary contractual relations between agencies in the “protection” market require that firms co-operate and, by so doing, to behave (effectively) as one large firm (and so resemble a normal state even more than they already do). Quoting Adam Smith seems appropriate here: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” [The Wealth of Nations, p. 117] Having a market based on people of the same trade co-operating seems, therefore, an unwise move.

For example, when buying food it does not matter whether the supermarkets visited have good relations with each other. The goods bought are independent of the relationships that exist between competing companies. However, in the case of private states this is not the case. If a specific “defence” company has bad relationships with other companies in the market then it is against a customer’s self-interest to subscribe to it. Why subscribe to a private state if its judgements are ignored by the others and it has to resort to violence to be heard? This, as well as being potentially dangerous, will also push up the prices that have to be paid. Arbitration is one of the most important services a defence firm can offer its customers and its market share is based upon being able to settle interagency disputes without risk of war or uncertainty that the final outcome will not be accepted by all parties. Lose that and a company will lose market share.

Therefore, the market set-up within the “anarcho”-capitalist “defence” market is such that private states have to co-operate with the others (or go out of business fast) and this means collusion can take place. In other words, a system of private states will have to agree to work together in order to provide the service of “law enforcement” to their customers and the result of such co-operation is to create a cartel. However, unlike cartels in other industries, the “defence” cartel will be a stable body simply because its members have to work with their competitors in order to survive.

Let us look at what would happen after such a cartel is formed in a specific area and a new “defence company” desired to enter the market. This new company will have to work with the members of the cartel in order to provide its services to its customers (note that “anarcho”-capitalists already assume that they “will have to” subscribe to the same law code). If the new defence firm tries to under-cut the cartel’s monopoly prices, the other companies would refuse to work with it. Having to face constant conflict or the possibility of conflict, seeing its decisions being ignored by other agencies and being uncertain what the results of a dispute would be, few would patronise the new “defence company.” The new company’s prices would go up and it would soon face either folding or joining the cartel. Unlike every other market, if a “defence company” does not have friendly, co-operative relations with other firms in the same industry then it will go out of business.

This means that the firms that are co-operating have simply to agree not to deal with new firms which are attempting to undermine the cartel in order for them to fail. A “cartel busting” firm goes out of business in the same way an outlaw one does — the higher costs associated with having to solve all its conflicts by force, not arbitration, increases its production costs much higher than the competitors and the firm faces insurmountable difficulties selling its products at a profit (ignoring any drop of demand due to fears of conflict by actual and potential customers). Even if we assume that many people will happily join the new firm in spite of the dangers to protect themselves against the cartel and its taxation (i.e. monopoly profits), enough will remain members of the cartel so that co-operation will still be needed and conflict unprofitable and dangerous (and as the cartel will have more resources than the new firm, it could usually hold out longer than the new firm could). In effect, breaking the cartel may take the form of an armed revolution — as it would with any state.

The forces that break up cartels and monopolies in other industries (such as free entry — although, of course the “defence” market will be subject to oligopolistic tendencies as any other and this will create barriers to entry) do not work here and so new firms have to co-operate or loose market share and/or profits. This means that “defence companies” will reap monopoly profits and, more importantly, have a monopoly of force over a given area.

It is also likely that a multitude of cartels would develop, with a given cartel operating in a given locality. This is because law enforcement would be localised in given areas as most crime occurs where the criminal lives (few criminals would live in Glasgow and commit crimes in Paris). However, as defence companies have to co-operate to provide their services, so would the cartels. Few people live all their lives in one area and so firms from different cartels would come into contact, so forming a cartel of cartels. This cartel of cartels may (perhaps) be less powerful than a local cartel, but it would still be required and for exactly the same reasons a local one is. Therefore “anarcho”-capitalism would, like “actually existing capitalism,” be marked by a series of public states covering given areas, co-ordinated by larger states at higher levels. Such a set up would parallel the United States in many ways except it would be run directly by wealthy shareholders without the sham of “democratic” elections. Moreover, as in the USA and other states there will still be a monopoly of rules and laws (the “general libertarian law code”).

Hence a monopoly of private states will develop in addition to the existing monopoly of law and this is a de facto monopoly of force over a given area (i.e. some kind of public state run by share holders). New companies attempting to enter the “defence” industry will have to work with the existing cartel in order to provide the services it offers to its customers. The cartel is in a dominant position and new entries into the market either become part of it or fail. This is exactly the position with the state, with “private agencies” free to operate as long as they work to the state’s guidelines. As with the monopolist “general libertarian law code”, if you do not toe the line, you go out of business fast.

“Anarcho”-capitalists claim that this will not occur, but that the co-operation needed to provide the service of law enforcement will somehow not turn into collusion between companies. However, they are quick to argue that renegade “agencies” (for example, the so-called “Mafia problem” or those who reject judgements) will go out of business because of the higher costs associated with conflict and not arbitration. Yet these higher costs are ensured because the firms in question do not co-operate with others. If other agencies boycott a firm but co-operate with all the others, then the boycotted firm will be at the same disadvantage — regardless of whether it is a cartel buster or a renegade. So the “anarcho”-capitalist is trying to have it both ways. If the punishment of non-conforming firms cannot occur, then “anarcho”-capitalism will turn into a war of all against all or, at the very least, the service of social peace and law enforcement cannot be provided. If firms cannot deter others from disrupting the social peace (one service the firm provides) then “anarcho”-capitalism is not stable and will not remain orderly as agencies develop which favour the interests of their own customers and enforce their own law codes at the expense of others. If collusion cannot occur (or is too costly) then neither can the punishment of non-conforming firms and “anarcho”-capitalism will prove to be unstable.

So, to sum up, the “defence” market of private states has powerful forces within it to turn it into a monopoly of force over a given area. From a privately chosen monopoly of force over a specific (privately owned) area, the market of private states will turn into a monopoly of force over a general area. This is due to the need for peaceful relations between companies, relations which are required for a firm to secure market share. The unique market forces that exist within this market ensure collusion and the system of private states will become a cartel and so a public state — unaccountable to all but its shareholders, a state of the wealthy, by the wealthy, for the wealthy.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some 50 miles southwest of Taipei, Taiwan’s capital, and strategically located close to a cluster of the island’s top universities, the 3,500-acre Hsinchu Science Park is globally celebrated as the incubator of Taiwan’s most successful technology companies. It opened in 1980, the government having acquired the land and cleared the rice fields,with the aim of creating a technology hub that would combine advanced research and industrial production.

Today Taiwan’s science parks house more than 1,100 companies, employ 321,000 people, and generate $127 billion in annual revenue. Along the way, Hsinchu Science Park’s Industrial Technology Research Institute has given birth to startups that have grown into world leaders. One of them, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), produces at least 90 percent of the world’s most advanced computer chips. Collectively, Taiwan’s companies hold a 68 percent market share of all global chip production.

It is a spectacular success. But it has also created a problem that could threaten the future prosperity of both the sector and the island. As the age of energy-hungry artificial intelligence dawns, Taiwan is facing a multifaceted energy crisis: It depends heavily on imported fossil fuels, it has ambitious clean energy targets that it is failing to meet, and it can barely keep up with current demand. Addressing this problem, government critics say, is growing increasingly urgent.

Taiwan’s more than 23 million people consume nearly as much energy per capita as US consumers, but the lion’s share of that consumption—56 percent—goes to Taiwan’s industrial sector for companies like TSMC. In fact, TSMC alone uses around 9 percent of Taiwan’s electricity. One estimate by Greenpeace has suggested that by 2030 Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing industry will consume twice as much electricity as did the whole of New Zealand in 2021. The bulk of that enormous energy demand, about 82 percent, the report suggests, will come from TSMC.

Taiwan’s government is banking on the continuing success of its technology sector and wants the island to be a leader in AI. But just one small data center, the Vantage 16-megawatt data center in Taipei, is expected to require as much energy as some 13,000 households. Nicholas Chen, a lawyer who analyzes Taiwan’s climate and energy policies, warns that the collision of Taiwan’s commitments to the clean energy transition and its position in global supply chains as a key partner of multinational companies that have made commitments to net-zero deadlines—along with the explosive growth in demand—has all the makings of a crisis.

“In order to plan and operate AI data centers, an adequate supply of stable, zero-carbon energy is a precondition,” he said. “AI data centers cannot exist without sufficient green energy. Taiwan is the only government talking about AI data center rollout without regard to the lack of green energy.”

It is not just a case of building more capacity. Taiwan’s energy dilemma is a combination of national security, climate, and political challenges. The island depends on imported fossil fuel for around 90 percent of its energy and lives under the growing threat of blockade, quarantine, or invasion from China. In addition, for political reasons, the government has pledged to close its nuclear sector by 2025.

Taiwan regularly attends UN climate meetings, though never as a participant. Excluded at China’s insistence from membership in the United Nations, Taiwan asserts its presence on the margins, convening side events and adopting the Paris Agreement targets of peak emissions before 2030 and achieving net zero by 2050. Its major companies, TSMC included, have signed up to RE100, a corporate renewable-energy initiative, and pledged to achieve net-zero production. But right now, there is a wide gap between aspiration and performance.

Angelica Oung, a journalist and founder of the Clean Energy Transition Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for a rapid energy transition, has studied Taiwan’s energy sector for years. When we met in a restaurant in Taipei, she cheerfully ordered an implausibly large number of dishes that crowded onto the small table as we talked. Oung described two major blackouts—one in 2021 that affected TSMC and 6.2 million households for five hours, and one in 2022 that affected 5.5 million households. It is a sign, she says, of an energy system running perilously close to the edge.

Nicholas Chen argues that government is failing to keep up even with existing demand. “In the past eight years there have been four major power outages,” he said, and “brownouts are commonplace.”

The operating margin on the grid—the buffer between supply and demand—ought to be 25 percent in a secure system. In Taiwan, Oung explained, there have been several occasions this year when the margin was down to 5 percent. “It shows that the system is fragile,” she said.

Taiwan’s current energy mix illustrates the scale of the challenge: Last year, Taiwan’s power sector was 83 percent dependent on fossil fuel: Coal accounted for around 42 percent of generation, natural gas 40 percent, and oil 1 percent. Nuclear supplied 6 percent, and solar, wind, hydro, and biomass together nearly 10 percent, according to the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Taiwan’s fossil fuels are imported by sea, which leaves the island at the mercy both of international price fluctuations and potential blockade by China. The government has sought to shield consumers from rising global prices, but that has resulted in growing debt for the Taiwan Electric Power Company (Taipower), the national provider. In the event of a naval blockade by China, Taiwan could count on about six weeks reserves of coal but not much more than a week of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Given that LNG supplies more than a third of electricity generation, the impact would be severe.

The government has announced ambitious energy targets. The 2050 net-zero road map released by Taiwan’s National Development Council in 2022 promised to shut down its nuclear sector by 2025. By the same year, the share of coal would have to come down to 30 percent, gas would have to rise to 50 percent, and renewables would have to leap to 20 percent. None of those targets is on track.

Progress on renewables has been slow for a number of reasons, according to Oung. “The problem with solar in Taiwan is that we don’t have a big area. We have the same population as Australia and use the same amount of electricity, but we are only half the size of Tasmania, and 79 percent of Taiwan is mountainous, so land acquisition is difficult.” Rooftop solar is expensive, and roof space is sometimes needed for other things, such as helicopter pads, public utilities, or water tanks.

According to Peter Kurz, a consultant to the technology sector and a long-term resident of Taiwan, there is one renewable resource that the nation has in abundance. “The Taiwan Strait has a huge wind resource,” he said. “It is the most wind power anywhere in the world available close to a population.”

Offshore wind is under development, but the government is criticized for imposing burdensome requirements to use Taiwanese products and workers that the country is not well equipped to meet. They reflect the government’s ambition to build a native industry at the same time as addressing its energy problem. But critics point out that Taiwan lacks the specialist industrial skills that producing turbines demands, and the requirements lead to higher costs and delays.

Despite the attraction of Taiwan’s west coast with its relatively shallow waters, there are other constraints, such as limited harbor space. There is also another concern that is unique to Taiwan’s geography: The west side of the island faces China, and there are continuing incursions into Taiwan’s territorial waters from China’s coast guard and navy vessels. Offshore wind turbines are within easy rocket and missile range from China, and undersea energy cables are highly vulnerable.

Government critics regard one current policy as needless self-harm: the pledge to shut down Taiwan’s remaining nuclear reactor by next year and achieve a “nuclear free homeland.” It is a pledge made by the current ruling party, the Democratic People’s Party (DPP), and as the deadline approaches, it is a policy increasingly being questioned. Taiwan’s civil nuclear program was started under the military dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT party with half an eye on developing a nuclear weapons program. Taiwan built its first experimental facility in the 1950s and opened its first power plant in 1978. The DPP came into existence in 1986, the year of the Chernobyl disaster, and its decision to adopt a no-nuclear policy was reinforced by the Fukushima disaster in neighboring Japan in 2011.

“I think the DPP see nuclear energy as a symbol of authoritarianism,” said Oung, “so they oppose it.”

Of Taiwan’s six nuclear reactors, three are now shut down, two have not been brought online, and the one functioning unit is due to close next year. The shuttered reactors have not yet been decommissioned, possibly because, in addition to its other difficulties, Taiwan has run out of waste storage capacity: The fuel rods remain in place because there is nowhere else to put them. As some observers see it, politics have got in the way of common sense: In 2018, a majority opposed the nuclear shutdown in a referendum, but the government continues to insist that its policy will not change. Voters added to the confusion in 2021 when they opposed the completion of the two uncommissioned plants.

On the 13th floor of the Ministry of Economic Affairs in Taipei, the deputy director general of Taiwan’s energy administration, Stephen Wu, chose his words carefully. “There is a debate going on in our parliament,” he said, “because the public has demanded a reduction of nuclear power and also a reduction in carbon emissions. So there is some discussion about whether the [shuttered] nuclear plants will somehow function again when conditions are ready.”

Wu acknowledged that Taiwan was nudging against the limits of its current supply and that new entrants to Taiwan’s science and technology parks have to be carefully screened for their energy needs. But he took an optimistic view of Taiwan’s capacity to sustain AI development. “We assess energy consumption of companies to ensure the development of these companies complies with environmental protection,” he said. “In Singapore, data centers are highly efficient. We will learn from Singapore.”

Critics of the government’s energy policy are not reassured. Chen has an alarming message: If Taiwan does not radically accelerate its clean energy development, he warns, companies will be obliged to leave the island. They will seek zero-carbon operating environments to comply with the net-zero requirements of partners such as Amazon, Meta, and Google, and to avoid carbon-based trade barriers such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

“Wind and solar are not scalable sources of zero-carbon energy,” he said. “Nuclear energy is the only scalable, zero-carbon source of energy. But the current laws state that foreign investment in nuclear energy must be capped at 50 percent, with the remaining 50 percent owned by Taipower. Given that Taipower is broke, how could a private investor want to partner with them and invest in Taiwan?”

Chen argues that Taiwan should encourage private nuclear development and avoid the burdensome regulation that, he says, is hampering wind development.

For Kurz, Taiwan’s energy security dilemma requires an imaginative leap. “Cables [carrying offshore wind energy] are vulnerable but replaceable,” he says. “Centralized nuclear is vulnerable to other risks, such as earthquakes.” One solution, he believes, lies in small modular nuclear reactors that could even be moored offshore and linked with undersea cables. It is a solution that he believes the Taiwan’s ruling party might come around to.

There is a further security question to add to Taiwan’s complex challenges. The island’s circumstances are unique: It is a functioning democracy, a technological powerhouse, and a de facto independent country that China regards as a breakaway province to be recovered—if necessary, by force. The fact that its technology industry is essential for global production of everything from electric vehicles to ballistic missiles has counted as a security plus for Taiwan in its increasingly tense standoff with China. It is not in the interest of China or the United States to see semiconductor manufacturers damaged or destroyed. Such companies, in security jargon, are collectively labelled Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” a shield the government is keen to maintain. That the sector depends inescapably on Taiwan’s energy security renders the search for a solution all the more urgent.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have to ask, how do you feel about the nihilism of the writing behind the show? Specifically about the ways people can’t truly ever change? (This is a bit broad sorry)

yeah i talked about this some the other day. like, my communist opinion is that the roys couldn't change because they were trapped within (choosing to stay within) the same set of circumstances, namely capitalism and the attempt to build an empire. even at the very end, losing waystar wasn't a choice any of them made to try to 'get out', and even if it had been, they still would have been operating within the ruling capitalist ontology, because capitalism is much larger than this one corporation. tbc, everything jesse armstrong has said makes me think his cynicism is different than mine: he thinks people are just intrinsically unable to change. i disagree with that; people have the capacity for radical alteration, and the oppression of capitalism will never succeed in eliminating human agency. but, as a story of people who are raised to treat the world like a market, and who continue to choose to do that as fully autonomous adults, i don't really have a problem with succession portraying them as stagnating. if anything, it would have really annoyed me if they were somehow able to self-actualise whilst still choosing waystar and profit and exploitation every single day. if you wanted to commie it up you could make one of them actually try to challenge capitalism (the closest we get is ewan's lawyer, who is doing this by trying to use the capitalist legal apparatus to his advantage, which is really just poking fun at petit-bourgeois) or you could write a story in which the pov characters are not billionaires running a family empire.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

NYPD Chief of Detectives Joseph Kenny told NBC New York in an interview Thursday that investigators have uncovered evidence that Luigi Mangione had prior knowledge UnitedHealthcare was holding its annual investor conference in New York City.

Mangione also mentioned the company in a note found in his possession when he was detained by police in Pennsylvania.

“We have no indication that he was ever a client of United Healthcare, but he does make mention that it is the fifth largest corporation in America, which would make it the largest healthcare organization in America. So that’s possibly why he targeted that company,” said Kenny.

UnitedHealthcare is in the top 20 largest U.S. companies by market capitalization but is not the fifth largest. It is the largest U.S. health insurer.

Mangione remains jailed without bail in Pennsylvania, where he was arrested Monday after being spotted at a McDonald’s in the city of Altoona, about 230 miles (about 370 kilometers) west of New York City. His lawyer there, Thomas Dickey, has said Mangione intends to plead not guilty. Dickey also said he has yet to see evidence decisively linking his client to the crime.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foreign Business License

Thailand, with its strategic location, burgeoning economy, and favorable business climate, has become a popular destination for foreign investors. To establish a business in the Land of Smiles, obtaining a foreign business license is essential. This article will provide a comprehensive overview of the process and key considerations.

Types of Foreign Business Licenses

The type of business license required depends on the nature of your business operations. Here are the most common types:

Limited Company (LTD): This is the most popular option for foreign investors, offering limited liability and a corporate structure.

Branch Office: A branch office is an extension of a foreign parent company, operating under its name and subject to its control.

Representative Office: A representative office is primarily for market research and liaison activities, without engaging in direct business transactions.

Obtaining a Foreign Business License

The process for obtaining a foreign business license in Thailand involves several steps:

Company Name Registration: Choose a unique and available company name that complies with Thai regulations.

Document Submission: Prepare and submit the necessary documents, including company registration forms, passports of directors, and proof of address.

Paid-up Capital: Deposit the required minimum paid-up capital into a Thai bank account. The amount varies depending on the type of business and business plan.

Office Registration: Register your business office with the Department of Business Development (DBD).

Tax Registration: Register your business for taxes with the Revenue Department.

Work Permits: Obtain work permits for foreign employees working in Thailand.

Important Considerations

Business Plan: A well-structured business plan outlining your company's objectives, operations, and financial projections is crucial.

Local Partner: In certain industries or sectors, a local partner may be required.

Regulations: Familiarize yourself with Thai business laws and regulations, including labor laws, environmental regulations, and import/export rules.

Visa Requirements: Ensure that you and your foreign employees have the appropriate visas to work and reside in Thailand.

Professional Assistance: Consider hiring a local lawyer or business consultant to guide you through the process and navigate Thai bureaucracy.

Conclusion

Obtaining a foreign business license in Thailand can be a rewarding endeavor. By understanding the requirements, preparing necessary documents, and seeking professional assistance, you can successfully establish your business in this dynamic and growing economy.

#lawyers in thailand#thailand#corporate in thailand#corporate lawyers in thailand#business in thailand#business lawyers in thailand

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What type of lawyer are you?

I work in corporate/capital markets law.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Increase in Monetary Threshold of Initial Public Offerings 2024 for Turkey

Increase in Monetary Threshold of Initial Public Offerings 2024 for Turkey is newly declared by Capital Markets Board of Turkey (Hereinafter as the Board). The Board changed the financial criteria for initial public offerings.

Introduction

Investment Advice offered by Turkish investment lawyers and|or Turkish business lawyers for investing in İstanbul and Turkey are very helpful for particularly foreign investors. Pi Legal Consultancy formulates papers for legal alerts on free investment advice for long-term investment projects in Turkey. Undoubtedly, expert advice can have an enormous impact duly planning the scope of any investment project.

Is Türkiye safe for investment? If you are curious about the answer to the question, you can read our article.

The development and enforcement of an overarching core principles is necessary for better integrated and consolidated capital markets. It is also essential to attract investments for Turkey. Monetary threshold for initial public offerings is an important aspect for consideration.

What is the main Supreme Authority for Capital Markets in Turkey?

The Capital Markets Board of Turkey is the main regulatory and supervisory authority for the field. The Board are granted following mandates:

-enhancement of investor protection,

-adoption the norms of the international capital markets,

-promotion and enhancement of the effectiveness of both the supply and the demand side of the markets,

-promotion of transparency and fairness in the capital markets,

facilitation of modernisation of the market structure,

For our work and all legal services on the matter of capital markets, please click our Practice Areas, titled Capital Markets

What is the legal alert on increase in monetary threshold of initial public offerings 2024 for Turkey?

A new decision dated December 29, 2023 has been published in the Capital Markets Board Bulletin (2023/82). Monetary thresholds have been revised by the Board for initial public offerings.

In accordance with the decision, the minimum amount for the registered capital system cannot be lower than TRY 100.000.000.

For a comprehensive discussion on the establishment of limited liability companies, take a look at our article on Limited Liability Company Formation.

For a comprehensive discussion on the establishment of limited liability companies, take a look at our article on Limited Liability Company Formation.

What is the monetary threshold for initial public offerings?

Monetary threshold is meant to meet minimum criteria in order to be able to go public for corporations. National authorities are granted wide margin of appreciation to interfere with changing the standards and conditions for initial public offerings.

What is capital markets consultancy?

The main purpose of Capital Markets Law is to regulate and control the secure, fair and orderly functioning of the capital markets and to protect the rights and benefits of the investors in Turkey. Changing capital markets remains a global challenge for every single country. The Turkish capital market legal regime is far beyond simple and thus requires an effective capital markets consultation. Capital markets consultancy will pave the way for success rate of your capital investments.

What Is the Role of Pi Legal Consultancy for capital markets consultancy?

Pi Legal Consultancy capital markets consultants support inter alia, as follows:

Initial public offerings,

Structured finance,

Mergers and acquisitions,

Real estate and regular investment trusts,

IPO Transactions,

Issue and sale of capital market instruments,

Call for public offer with a view to purchasing capital market instruments and any sale,

Publicly held corporation,

Publication of the prospectus, announcement and advertisements.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, it is worth re-emphasizing that Turkey has been regarded as one of the most attractive investment-friendly regions across the globe. Investors should bear in mind all regulatory changes about Turkey. The Turkish Capital Markets Board made a recent change in initial public offerings 2024 for Turkey. In short, this change will have a challenging influence upon initial public offerings 2024 and going public for Turkey.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

re: last reblog i really do think it’s a testament to the idea that. humans do genuinely WANT to work like we all fucking LOVE among us we like to do little tasks and feel like we are Helping. and we know intuitively that we have to Help in order for things to Work, but luckily we all have Things that are Pleasant for us to do (or, at the very least, that we are Good At) that we can and want to do to Help. the problem is NO ONE wants to work if that’s the only way we can keep living, to pay for housing, for food, to get healthcare. and people are instead going to do whatever thing they can kind of whatever at in order to pay bills most effectively... meaning people aren’t actually doing the Helping in the way they are best suited to... and that makes me sad. just as a guy who is good at Very Few Things and has a very limited set of jobs he can actually do, but, through a rare instance of extreme privilege (amidst the Everything Else i have not going for me), have the opportunity to take one of the Very Few Things i have and run with it. and hopefully i will do a very very good job!!! but so many people want that job and other jobs because they pay well, not because they genuinely think that is the best way for them to Help. and it’s just frustrating because that’s how you get a lot of people who are Really Fucking Bad At Their Job, which is a huge problem in things like healthcare, or a lot of people who are Really Good At Their Job, But Their Job Happens To Be Being The Worst Fucking Human Alive (wall street, marketing research, corporate lawyers, any job that involves the production and protection of capital). and i’m like Man. what happened to the kid who asked their classmates if they were okay when they fell off the playground. the kid who shared goldfish if they saw another kid didn’t have a snack that day. humans hate seeing other people suffer, yet we are so willing to perpetuate it if that means we can save our own hinds. and then we get confused when the people who are suffering say “fuck this!!! i don’t wanna anymore.”

this has... diverged a long way from where i was originally going. but idk. i guess what i’m saying is “to each according to his need,” yes, good, we can all agree on that. but it’s preceded by “from each according to his ability...” and i guess what i’m saying is, if you remove the imminent threat of death... humans on the whole are much more able, in a much wider arrange of domains, than we give ourselves credit for.

#like we laugh and joke about 'i'm a dj' 'i resell vintage' 'i'm looking for a sublet' 'i sell k' or the commune being full of nerds who can#*can do tarot readings or whatever#but there are people who WANT to grow and tend crops and there are people who WANT to make food and there are people who WANT to deliver the#*the mail#i mean i'd be okay with cleaning a public toilet once in awhile as long as i didn't have to do it all the goddamn time. and could contribute#*contribute in other ways for the other 4 days of the work week.#and also if i were given proper ppe.#like each of us has things we can do and would be willing to do that are actually helpful as long as we didn't have to do it all of the time#or could alternate#does that make sense. i mean i'm kind of on the transsexual marxists who love weed and autism and abortions website. so i'm sure we're biase#*biased. but#he scream at own follower

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Step by Step Ep 10

Soooo, Jeng admonishes Pat for doing something behind his back, for doing something without discussing it with him first (he's right). Then Jeng does EXACTLY the SAME thing lol The funny thing is that objectively looking at this whole situation, this mess and chaos, Pat did the right thing by resigning. Similarly, Jeng basically did the right thing as well, by making sure the department survived because too many people work there.

And that's one of the things that annoys me so much about this office romance: everyone in the office is so obsessed with Jeng and Pat, with corporate little games, with blackmail, with gossip, that everyone has forgotten that, SURPRISE!, other people work there too, people who have invested their time and energy in this work and who must live and support themselves in the capital city, where everything is always more expensive. Jeng and Jaab will always be fine, but what about the others? When Jeng heroically proposes that Pat stays and HE resigns... it's romantic, but I want to kick his ass, like.. man, the future of the department depends on you, not Pat! But obviously, you didn't think about THIS, trying to heroically sacrifice for your beloved! But I have a suspicion bordering on certainty that at this point, in Jeng's head: department=Pat 😀 It’s juts... I’m too old for this. Watching it literally makes me feel tired.

In the fantasy world of SBS, you can resign and come back to work the next day as if nothing had happened, The Gays ruin companies, the stock market, the economy, whatever (although the company uses BL themes in marketing but like, they’re not The Real Gays), and a video of two guys embracing is the end world and probably everyone! the whole country! is talking about it! and it’s a tragedy! Maybe that's how it is in Thailand and I'm wrong, but does Pat, an ordinary worker whose private life is used by the company he works for, have NO options to defend or even attack? As I understand it, the video recorded during his free time, of him doing nothing inappropriate, is circulating on the company's OFFICIAL group chat and being discussed by management, moreover, it is being used for some dirty games. Are there no lawyers in Bangkok? Never mind, since sleeping in the same bed in a hotel, SBS has repeatedly made plot inserts like that, that don't make sense.

Anyway, it's a total mess because Jeng and Pat never had a decent, honest, not necessarily nice conversation about their relationship and its place in the company, they just jumped right into the pool of love and fan service. The show spends LOTS of time on power point presentations but doesn't spend a minute on Jen a Pat talking about work, jumping straight to the drama. I think - this is just my personal opinion - Jeng should suggest, that it would be a good idea if Pat resigned at the beginning of their relationship, when Pat had not yet gotten into trouble, could get good references, leave a good impression, etc. Jeng should help Pat financially and support him while he is looking for a new job. They MUST work separately, which is just good for a relationship. Yes, it wouldn't be a nice conversation, but it would be necessary. Like most important conversations in life. I fondly remember Unintentional Love Story where rich and influencial TaeJoon with heart eyes and with full firmness says to his young boyfriend "you have my full permission to use me". That was super hot and romantic in how honest and open about his wealth and position TaeJoon was, but maybe it’s just me 😉. Jeng IS older and richer than Pat, there's nothing wrong with supporting him until he finds new job. Is that fair to Pat? Of course it isn't! But in the real world (and even in the fantasy world of SBS), there is no other way if Pat and Jeng want to be together and want to be happy.

In the next episode trailer, one of my most hated tropes in BL was announced: the time jump. TWO YEARS. I HATE THIS. Sure! There's nothing better than wasting the best years of your life on pain and unfulfilled love. Who would want to spend this time working on the relationship, solving problems TOGETHER, kissing and cuddling and stuff? Some losers probably, the real men ✨SUFFER✨. Separation is just so romantic, unlike some boring work on yourself and love for the other person, right?....😑

I respect Be My Favorite for a lot of things, but one of them is that it's one of the few shows lately where the characters actually TALK. Yes, they argue a lot, they fight, but it's still good because they are honest with each other, even when they yell at each other. 😄 And what is important is that later they come back to each other and apologize, explain. Personally, I prefer BMFs to be all about communication, talks and personal development even if they had to do it until the end of the series and become a couple in the last minute of the season 😎 I prefer that to no communication and unnecessary drama.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Commercial law is the body of law that governs business and commercial transactions. It covers a wide range of legal issues that arise in the context of business activities, such as contracts, intellectual property, employment, and finance. Commercial law also regulates the formation and operation of different types of business entities, such as corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships. The purpose of commercial law is to provide a legal framework that promotes fair competition, protects businesses and consumers, and facilitates economic growth.

#law firm in mumbai#law firm mumbai#capital markets lawyer#divorce lawyer mumbai#advocates in mumbai#top law firm in mumbai#criminal lawyers in mumbai#best law firm in mumbai#best lawyers in mumbai#best lawyers in mumbai for property#criminal law firms in mumbai#law firms in fort mumbai#legal firm in mumbai#solicitors in mumbai#corporate law firms in mumbai#legal firms in mumbai#best criminal lawyer in mumbai#best law firms in mumbai#advocates mumbai#top lawyers in mumbai#corporate lawyers in mumbai#litigation law firms in mumbai#solicitor firms in mumbai#law firms mumbai#top corporate law firms in mumbai#insurance claim advocates in Mumbai

0 notes

Text

Top Strategies for Successful Deal Sourcing in Private Equity

Correct deal sourcing ensures long-term success. Remember, without a steady flow of quality investment opportunities, even the leading private equity (PE) firms can quickly fall behind their competitors. Therefore, deal sourcing is not merely about finding companies to invest in. Rather, it is about capturing the promising opportunities without being left out. This post will explore the top strategies enabling private equity firms to optimize deal sourcing.

What is Deal Sourcing?

Deal sourcing or deal origination involves multiple practices aimed at discovering the investment opportunities and business merger possibilities that yield the best above-the-market returns. It also prioritizes risk assessments that conform to investor profiles or company leadership’s expectations. Comparing multiple investment opportunities is vital to avoid investing in a less competitive corporation. Besides, several relationship management and pitch deck creation methods can affect how what deal sourcing in private equity entails, resulting in variations across PE firms.

What Are the Top Deal Sourcing Strategies in the Private Equity Space?

1. Building Strong Relationships

A tried and tested strategy to source deals lets stakeholders thrive using private equity. It might involve developing and nurturing strong relationships. Connecting with business owners, industry experts, and intermediaries will also open more doors to exclusive opportunities. Most private equity companies create these relationships over the years, but sometimes, doing so takes decades.

Attending industry conferences, taking part in networking events, and constantly engaging with stakeholders develop credibility and trust. Credibility and trust facilitate early insights into companies looking for investors or acquisition opportunities.

Maintaining relationships with intermediaries means networking with investment bankers, brokers, and lawyers. This practice is important because they are often the first to know when a business is ready to explore new capital. They also understand when to sell an asset based on market conditions. By being a reliable and proactive partner, firms offering private equity services can get early access to promising deals.

2. Upgrading Technology and Data Analytics

Most industries have refined their workflows to prepare for data-driven environments. Financial sectors are no exceptions to this trend. Accordingly, successful deal sourcing relies on technology and advanced data analytics. Private equity firms are now using proprietary databases. They also seek relevant artificial intelligence tools or machine learning modeling methods.

Once selected, new tech often helps PE firms sort and explore extensive data volumes. As a result, they can swiftly identify potential investments with better yields. Related tools also allow firms to evaluate industries and analyze market trends for under-the-radar opportunities.

For example, automated data scraping and sentiment analysis will successfully point out companies picking up steam or receiving good reviews. Their attractiveness as assets in their respective markets will be governed by many metrics.

However, technology upgrades enable private equity professionals to track and analyze them. Consider historical performance variations, financial health, and growth potential of thousands of companies. Automating their examination allows for quicker, more informed decisions to be made. At the same time, processing data faster than the competition can give firms a huge edge.

3. Proactive Sector Specialization

Another popular and effective strategy for successful deal sourcing is sector specialization. In this case, many private equity advisory teams will focus on specific industries where they possess deep knowledge. For instance, healthcare, technology, manufacturing, or consumer goods. By narrowing their focus, firms can develop a nuanced understanding of sector dynamics. They can also surpass generalist PE firms when it comes to grasping competitive landscapes’ threats and potential growth opportunities.

Sector specialization allows firms to recognize trends and anticipate market shifts before other financial guidance providers do so. It ultimately helps PE professionals build credibility within a given industry. Furthermore, business owners are often more comfortable partnering with them to get investors who have an informed understanding of the unique challenges and opportunities of their sector. This expertise will undoubtedly lead to more inbound deal opportunities.

Additionally, by focusing on a specific sector, it becomes easier for firms to identify standalone investment opportunities along with potential synergistic acquisitions. In turn, ambitious portfolio improvement goals become feasible. This strategic approach creates a snowball effect where one successful investment triggers further opportunities.

4. Proprietary Deal Flow Development

Sometimes, relying solely on intermediated deal sourcing can lead to intense competition. The unwanted outcomes of similar circumstances often include inflated valuations. How can PE firms mitigate this? They must develop proprietary deal flow channels. In other words, they will identify and engage potential targets directly rather than waiting for an intermediary.

Firms achieve this by conducting market research on attractive companies. Later, they interact with company owners and executives to build trust-driven relationships. While cold outreach is daunting, successful outreach assures great rewards. To this end, stakeholders must execute these efforts thoughtfully.

A firm that takes the time to understand a company’s business, goals, and needs before making contact is far more likely to create meaningful conversations. On the other hand, a lack of proprietary deal flow development can hinder communications.

It is truly labor-intensive but helps PE firms gain access to deals that their competitors likely have no clue about. This exclusive access, therefore, leads to better pricing, more favorable terms, and less competition.

5. The Use of Buy-Side Advisors

Buy-side advisors often provide private equity professionals with the expertise they need to improve their deal sourcing. These advisors specialize in identifying and evaluating potential investments based on the firm’s criteria. They use their intelligence networks, market insights, and industry expertise to identify opportunities that a firm would not have considered on its own.

These advisors also excel at conducting due diligence. Their approach includes checking enterprise track records to ensure that the investments will meet the client firm’s standards and expectations. That is why PE stakeholders can optimize efficiency and divert their in-house resources to higher-value activities. Outsourcing a few activities in deal sourcing to experienced professionals will also help distribute data-related risks.

6. Strengthening the Brand and Reputation

Reputation is everything in private equity. Consequently, PE firms that have integrity, expertise, and an ability to add value to their portfolio companies will be far more likely to receive inbound deal flow. Remember, business owners want to partner with PE professionals they trust. It is no wonder that a strong brand assists in attracting and securing high-quality investment opportunities.

Developing a reputed brand requires consistent efforts in thought leadership, public relations (PR), and proven track records. Accordingly, publishing industry reports, speaking at conferences, and sharing case studies of successful investments can help PE firms position themselves as leaders in their fields. When business owners think of potential investors, firms with a visible and positive reputation are more likely to come to mind.

Conclusion

Successful deal sourcing in private equity requires relationship-building strategies powered by technological innovation and sector expertise. Proactive outreach is also integral to increasing awareness about what the PE firms do. Meanwhile, a strong brand reputation augments networking efforts as more business owners and investors habitually think of the firm.

By using these strategies, private equity firms can ensure a steady pipeline of high-quality opportunities across deal sourcing. They can position themselves for long-term success and competitive resilience while creating lasting values for their investors and portfolio companies.

0 notes

Text

The Dutch BV is the preferred legal entity for many entrepreneurs due to its:

Limited liability, protecting shareholders’ personal assets.

Professional image, ideal for domestic and international operations.

Flexible ownership structure, suitable for single or multiple shareholders.

Steps to Establish a Dutch BV

Draft the Articles of Association

Collaborate with a Dutch notary to outline the company’s internal regulations.

Deposit Initial Capital

A minimum of €0.01 is required, making it accessible for startups.

Sign the Incorporation Deed

Finalize the incorporation process by signing the deed with the notary.

Register with the KvK

The notary typically handles this step, ensuring compliance.

Comply with Tax Regulations

Obtain a corporate tax number and adhere to ongoing tax obligations.

Advantages of a Virtual Office in the Netherlands

A virtual office is a cost-effective way to establish a credible presence in the Netherlands. It offers:

Prestigious Business Address: Enhance your company’s professional image.

Cost Savings: Avoid the high expenses of renting physical office space.

Flexibility: Ideal for remote or international businesses testing the Dutch market.

Mail Handling Services: Efficiently manage correspondence and deliveries.

Common Challenges and How to Overcome Them

Understanding Dutch Regulations:

Consult with local experts or partners to navigate legal requirements.

Language Barrier:

Many Dutch professionals are bilingual, but official documentation may require translation.

Tax Compliance:

Utilize professional services to ensure accurate filings and adherence to deadlines.

Why Partner with House of Companies?

House of Companies offers comprehensive services to simplify the business setup process, including:

Assistance with registration and incorporation.

Virtual office solutions in prime locations.

Ongoing support for compliance, tax filings, and administrative tasks.

Resources for Entrepreneurs

Business Formation in the Netherlands: Expert insights into starting your business.

Start a Dutch BV: Step-by-step guidance for setting up a Dutch BV.

Virtual Office Solutions: Tailored services to support your business operations.

Conclusion

The Netherlands’ vibrant economy and business-friendly environment make it an excellent choice for entrepreneurs and companies looking to expand their horizons. By understanding the steps to business registration, leveraging the benefits of a Dutch BV, and utilizing virtual office solutions, you can establish a strong foothold in the Dutch market. Partner with House of Companies for expert assistance and unlock the full potential of your business in the Netherlands.

0 notes

Text

How to Invest in Commercial Real Estate: A Comprehensive Guide

Investing in commercial real estate has long been a popular strategy for building wealth and generating passive income. With its potential for higher returns, diversification, and stability, it’s no wonder that many individuals and businesses are keen to explore opportunities in this lucrative sector. However, diving into commercial real estate requires a solid understanding of the market, strategic planning, and careful execution.

This guide will walk you through the essentials of how to invest in commercial real estate, ensuring you’re well-prepared to make informed decisions.

Understanding Commercial Real Estate Commercial real estate (CRE) refers to properties used for business purposes, such as offices, retail spaces, industrial facilities, and multi-family apartment buildings. Unlike residential real estate, where properties are typically used for living, commercial properties generate income through leasing to businesses or tenants.

The key types of commercial real estate include:

Office Spaces: Corporate buildings, co-working spaces, and small office units. Retail Spaces: Shopping malls, standalone stores, and retail complexes. Industrial Properties: Warehouses, manufacturing units, and distribution centers. Multi-family Residential: Apartment complexes with multiple units rented out. Specialty Real Estate: Hotels, hospitals, and recreational facilities. Benefits of Investing in Commercial Real Estate When you decide to invest in commercial real estate, you gain access to numerous advantages, such as:

Higher Income Potential: Commercial properties generally offer higher rental yields compared to residential properties. Long-term Leases: Commercial tenants often sign multi-year leases, ensuring steady income over a longer period. Diversification: Investing in CRE allows diversification of your portfolio, reducing risks associated with other asset classes. Value Appreciation: Well-located commercial properties can experience significant value appreciation over time. Tax Benefits: Investors can benefit from tax deductions on mortgage interest, property depreciation, and operating expenses. Steps to Invest in Commercial Real Estate 1. Define Your Investment Goals Before making any commitments, it’s crucial to determine why you want to invest in commercial real estate. Are you looking for passive income, capital appreciation, or a combination of both? Defining clear objectives will help you choose the right type of property and strategy.

2. Understand the Market Research is a cornerstone of successful commercial real estate investment. Analyze market trends, demand-supply dynamics, and the economic outlook of the area you’re considering. Key factors to evaluate include:

Local economic growth Infrastructure development Vacancy rates Average rental yields 3. Choose the Right Property Type Your choice of property should align with your investment goals. For example:

If you prefer steady cash flow, opt for office spaces or multi-family units. If you’re targeting high returns, consider retail spaces in prime locations. 4. Secure Financing Commercial real estate investments often require significant capital. Explore financing options such as:

Traditional bank loans Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) Private equity funds Syndicated deals Ensure you have a robust financial plan to manage down payments, mortgage payments, and maintenance costs. 5. Conduct Due Diligence Before closing a deal, perform thorough due diligence to assess the property’s viability. This includes:

Inspecting the physical condition of the property Verifying legal documentation Reviewing financial records Analyzing the tenant profile and lease agreements 6. Hire Professionals Commercial real estate transactions can be complex. Hiring experienced professionals such as real estate agents, lawyers, and financial advisors can streamline the process and minimize risks.

7. Close the Deal Once you’re satisfied with the property’s potential, negotiate favorable terms and close the deal. Ensure all agreements are documented and legally binding.

Popular Strategies to Invest in Commercial Real Estate There are multiple ways to invest in commercial real estate, catering to different risk appetites and financial capacities.

1. Direct Ownership Purchasing a property outright gives you full control over its management. This strategy is ideal for investors seeking long-term gains but requires substantial capital and active involvement.

2. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) REITs allow you to invest in commercial properties without owning them directly. These trusts pool funds from investors to purchase and manage income-generating properties, offering dividends in return.

3. Crowdfunding Platforms Online platforms enable individuals to invest in commercial real estate projects with smaller amounts. This is a cost-effective way to diversify your portfolio.

4. Partnerships Forming partnerships with other investors can help you pool resources and share risks. Ensure clear agreements are in place to avoid conflicts.

5. Flipping Commercial Properties Buying undervalued properties, renovating them, and selling them at a profit is a high-risk, high-reward strategy.

Challenges of Investing in Commercial Real Estate While the rewards can be significant, investing in commercial real estate also comes with challenges:

High Initial Costs: Commercial properties require substantial upfront investment. Market Volatility: Economic downturns can impact rental income and property values. Management Complexity: Managing commercial properties involves dealing with tenants, maintenance, and compliance. Illiquidity: Selling commercial properties can take time, especially in a sluggish market. Mitigating these challenges requires thorough planning, risk assessment, and professional guidance.

Tips for First-time Investors in Commercial Real Estate Start Small: Begin with smaller properties or invest through REITs to gain experience. Focus on Location: Prioritize properties in high-demand areas with good infrastructure. Build a Network: Connect with industry experts, brokers, and other investors to gain insights. Stay Informed: Keep up with market trends and regulatory changes to make informed decisions. Diversify: Spread your investments across different property types and locations to minimize risks. Why Now is a Good Time to Invest in Commercial Real Estate The commercial real estate market is witnessing a resurgence, driven by factors such as: