#bur oak

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bur oak, the largest acorns in my region

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mine#photography#minnesota#trees#woods#drought#river#railroad#train#dead trees#midwestern gothic#rural gothic#barren trees#bur oak#the church of splatter day saints

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bittersweet nightshade, among the plants I personally associate with the Morrigan in my practice, growing in the crook of a double-trunked bur oak. I have been seeking to divine a period of time for an oath/geis, and I believe the number of berries to be the answer after also divining a confirmation. Crows calls rang out as my Grove and I came upon this tree during a casual gathering. Rather than a new oath/geis, this is a continuation. Bittersweet nightshade is symbolic of fidelity, healing, and protection (though it is poisonous).

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

your girl is tatted

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

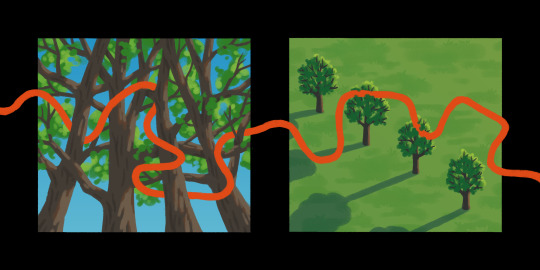

a piece i did for a class on native american history, inspired by Murder on the Red River by Marcie Rendon (more info under cut)

“She bounded down two concrete stairs and stepped out on to the green grass of the campus mall, surrounded on either side by thick stately oaks. She could tell each one had been strategically planted along the winding sidewalks between the red brick buildings. Even with groups of students sitting on the grass, leaning against their trunks, the trees seemed lonely. Nothing like the oaks along the river that grew where they wanted to grow and leaned in and touched each other with their middle branches, whose voices sang through their leaves like the hum of electric wires running alongside the country roads.” From Murder on the Red River

This piece is inspired by Murder on the Red River, a mystery novel by Marcie Rendon. It’s about Cash Blackbear, a young Ojibwe woman who investigates the murder of a Native man. Cash was taken from her mother and siblings as a young child and lived in a series of foster homes, most of which were abusive. About a third of Native American children were taken from their parents and placed in foster homes, even when they could have been placed with relatives instead of being separated from their community members and culture. Native American boarding schools, which also separated children from their families and culture, had mostly all been shut down by the 1970s (Katherine Beane), when Murder on the Red River takes place. But the removal of children to foster homes was just another way that the government tried to force Native Americans to assimilate into white culture. The Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978. It set requirements to keep Native children with relatives when safe and possible, and to work with the tribe and family of children. This act has made progress, though Native children are still adopted or placed in foster care at a higher rate than non-Native children (NICWA). In my illustration, there are four trees, representing Cash, her mother, and her two siblings. In the image on the right, the trees are growing as they do in their natural forest habitat, winding together. In the image on the left, the trees have been planted on the neat lawn of the college campus, a place where white culture is dominant. The trees are apart from each other, separated as Cash’s family were torn apart. They were forced to assimilate as many Native Americans were. The trees are bur oaks, aka Quercus macrocarpa, a species native to North Dakota where the book takes place. Their range encompasses much of the U.S. and parts of Canada (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center). The grass on the right image is Kentucky Bluegrass, aka Poa pratensis. It is invasive to North America. It was introduced in the 17th century from Europe, and is now found all over North America. It is commonly used for lawns and pasture, and can outcompete native prairie plants (North Dakota State Library). The Red River borders North Dakota and Minnesota. The Ojibwe have lived in Minnesota since before the 17th century, after migrating from Northeastern North America over hundreds of years (Minnesota Historical Society). The shape of the Red River traces through the image, weaving and intermingling through the branches of the trees, showing Cash’s deep connection with the land she is from.

Works Cited “About IWCA” National Indian Child Welfare Association, https://www.nicwa.org/about-icwa/ Beane, Katherine, American Indians in Minnesota, 12 March 2024, Nicholson Hall, Minneapolis, MN. Lecture. “Kentucky Bluegrass”, North Dakota State Library. https://www.library.nd.gov/statedocs/AgDept/Kentuckybluegrass20070703.pdf Rendon, Marcie. Murder on the Red River. Soho Crime, 2017. “The Ojibwe People”, Minnesota Historical Society, https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/native-americans/ojibwe-people “Quercus macrocarpa”, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=QUMA2

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I find it strange how you'd like to get so fat that you depend on someone but at the same time you're saying that you wanna do gardening. It's like there is a confrontation between your kink and your regular life...

in fantasy (or with a lot of consideration between me and my feeder) i’d become dependent. realistically, i’ve always dreamt of having my own garden and i think i could keep up with it at over 350lbs tbh

why can’t i have both…… scooter accessible garden pls. with raised beds i won’t have to bend over too much 🥺

bonus. bacon and tomato sandwich w home grown red snapper variety tomatoes, one of the only beefsteak-like varieties that grow in TX 🥳 DELICIOUS w mayo and some black pepper.

#i mean. i can do everything now esp w a garden wagon and smthn to put under my knees lol!!#btw lettuce plants don’t like the heat we have rn so there’s not many leafy greens haha#it would’ve been a blt!!!#picking tomatoes n green beans braless is a joy i wish on every fat girl#also btw. i want an arboretum tooooooo#not just fruit trees… hear me out. i lov mesquites and i love mesquite flour#bald cypress. i love their lil cone scents. i’d make oils 4 soaps#bur oak… you can eat their big ass acorns…#i wish for a pawpaw tree but that’s not happening in TX unless ur in the east#if you build things well it’s not too bad#raised beds exist. drip systems exist#talk#ask#i am posting this at midnight so ppl don’t make fun of me for this shitty yummy sandwich m

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

have you ever seen an Oak tree so beautiful it made you cry?

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, Sacramento. I continue to like your airport (so far as airports go).

#honestly i'm down with almost every significant airport here#SNA BUR ONT LGB SFO OAK SJC SAN#but of course what is the one that people always book before i can warn them otherwise? fucking lax

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

thoughts on midwest pine species?

if native: 👍

... im not much of a tree person.... much more of a flower/grass/shrub kinda guy. sorry :(

#i get an ask.... i get an ask about plants... i get an ask about native midwest plants... its trees :(#I DONT KNOW SHIT ABOUT TREES YALL#i love my guy bur oak and swamp white oak and maybe a couple box elders and cottonwoods. outside of that im lost#i look at a deciduous tree and think 'oh that might be a sycamore' i look at a conifer i think 'ooh cool tree'

1 note

·

View note

Text

Storm knocks over historic Plano tree estimated to be 400-plus years old

The historic 90-foot tall Bur Oak at Bob Woodruff Park in east Plano fell during a storm this week. Arborists have estimated the tree could be older than 400 years old.

View On WordPress

#Historic bur oak falls during storm at Bob Woodruff Park in Plano TX#Plano parks#Plano Tree City USA#Tree

0 notes

Text

oldman!price x reader angsty (?) drabble

‧︎✳︎༚︎‧︎⁎︎°︎

age leaves john price in tantrum.

he despises what it’s done to his body. the creak in his knees when he walks, the strain in his shoulder when he reaches across the table. steam engine, ironclad and coal hot, neglected the rust on the belly of its stirrups. adopted a sudden fragility he cannot stand.

takes a literal force of nature to get him to retire, and he grieves it like a father. it, in all honesty, was one. taught him how to shoot straight, how to hold his men, how to be without feeling like he’s an imposter in his own skin. forced him to grow up- which is ironically exactly what ended their alliance.

nursed whiskeys, fattened ice kissing the base. smoked like somehow- fossilized in ligero- he’d find his youth again. blistered under reluctant mortality, indulged in fatal vices because if anything is putting him in the grave it’s a gun or a cigar.

a pot never boils watched, yet you stay at your designated post by the doorway while he broods (he’s a dramatic at heart), storm clouds stamped on the collapse of his shoulders.

if you were one of his soldiers, you let him fester.

but you were his wife.

it wasn’t like you hadn’t aged yourself, silver linings sprouting from your scalp, sun spots and bleached knuckles. even so, you found time to pick up his medications, comb through amateur food blogs for gut health and bone pain, roll the aches out of his shoulder before bed. you were kind- and it was insulting.

spitfire catching on the burs of his muttonchops- unfamiliar with dependence. he was a captain for Christ’s sake- alloy lighthouse, built by cement and sheer fucking will. he didn’t need to be hand fed vitamin C and dragged to yoga class. he pitched barbed wire, dug his shallow trench and intended lay in it.

until, one evening, thunder strikes him out of dewy acrimony. he clambers up the stairs, musk of tobacco and spite plants a grimy boot in the oak. he glances over the railing, and stills.

bathroom door, cutting swaddled atmosphere with thin bisque, a pyramid down the center of the hall that created the illusion of darker corners. centered in the odd, domestic scaffolding was you- shower damp and concentrated.

it was like watching a bird preen feathers. tugging at the sags, yanking at the silvers, skin pitching at the nostril and eyes narrowing into thin keyways. and if he squinted, sniper accuracy rendered tears. sallow river bed on your flushed cheeks, clumped lashes, a frown that broke hearts.

“you’re never struggling alone, John,” you had said one evening, when he had been foolishly apathetic, “i’ll make sure of that.”

he hadn’t said anything.

guilt squirms at the base of his neck. the stranger named comfort that swelled within your embrace unnerved him so much he had forgotten to introduce himself. and now, milking moonlit lighting, with a wife who thought he was hiding from her, he called himself what he had never been as a soldier.

a coward.

you were making tea the next morning, windows surrendering a warmth when the day was still docile. it was while you were humming that your husband, sneaky bastard, folds you into the plush of his chest, drowsy lips dragging on the cusp of your shoulder.

“you always look so beautiful in the mornin, darlin.”

and it was true. you’ve never looked better to the old man.

#he bought you flowers after this btw#hates to see his wife cry :(#john price x you#captain john price x reader#captain john price x you#john price x reader#price x reader#price x you#john price#captain johnathan price#captain john price#price cod#john price cod#jonathan price#spurbleu✴︎‧︎⁎︎drabbles

642 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please could I request a Sonic x reader where reader is feeling down about themselves and has low self esteem and Sonic is there to comfort them ? Thank you !!

⋆🎐˚。⋆ — literally have been fantasizing about sonic making me feel better about myself as a person for a good three months. that would fix me, me thinks! ty for requesting! <3

⤷ sonic x insecure!reader 𐚁₊⊹

— “i hope i don’t look like an idiot,”

sonic whispered to himself, watching himself comb through his quills in the full length mirror in the living room. you two were simply getting ready to go out with friends, where you would meet up at an arcade — or wherever the night took you. he felt rather proud of how he presented himself, but then again, you were his common sense, so he would have to ask you before confirming anything.

at the thought of you, his legs instantly darted to the door of your bedroom, knocking a few times.

“babe, you comin’?” he called out, his face inches away from the door as he waited excitedly. when he was met with an odd sound of ruffling and a moment of silence, his eyes furrowed at the lack of response and pressed his ear against the cool oak.

“…you okay?” he asked, dragging the question in his voice. a muffled “yeah” was made out of the barrier between you two, which caused sonics ear to twitch out of discomfort with that answer. he pursed his lips and gently twisted the knob, stepping into the room hesitantly.

you sat on your bed, and you looked lovely. but you sat there, looking at the mirror on your left hand side. you didn’t turn your head when he walked in, and for a moment he was concerned.

“uhm,” he started, not sure what to say. “y/n?” he walked up to you and his heart thumped as he got a closer look at your outfit. “is that new? i don’t think i’ve seen this one before. definitely not complaining.” he tried to seem flirtatious like he usually is, but he couldn’t help but notice your unamused face that still stared in the mirror.

sitting beside you, not taking his eyes off of your drooped head, he tilted his own in curiosity. “do you not like it?” he questioned in a gentle voice, making sure he didn’t overwhelm you. you sat silent for another moment, the gentle burring of the ventilation humming quietly in the back.

“‘m just thinking.” you responded blandly, your mouth feeling dry. sonic tapped his finger on his leg, not knowing what to say. “about?” he questioned.

catching a glance of your face as you looked at him, he noticed the exhausted expression in your eyes. it startled him. before he could speak, you took a breath, pausing for a moment before resuming,

“sonic, i don’t…” you shook your head slightly, looking to him again. “…like… anything about myself.”

your voice slightly broke out of stress, running a hand through your hair. you laughed a little, trying to not seem so dark, but that didn’t hide anything from sonic. his ears folded down as a form of heartache, his chest feeling pained to hear those words.

“hey, hey—“ he moved slightly closer to you, his hand resting on the small of your back. “what? why… why do you think that?” his voice almost went up an octave out of both confusion and shock, as for he only ever saw you as a perfect entity that didn’t deserve to be trapped on the limits of earth.

taking a shaky breath, you let your hands fall to your lap in defeat. “i feel like a burden, i guess? like your friends don’t enjoy my humour, or my presence, or the fact that im only around because you happen to be with me? hell if i know.” you intended to come off as irritated, but to your boyfriend, you just sounded hurt. he shook his head reassuringly, leaning his face closer to you so you would look at him.

“y/n, they adore you. literally. i can’t even — there is everything to love about you. do you not see that?” he asked that question as if he were genuinely shocked, his eyes concerned and sad. he absolutely despised seeing you so upset with yourself, he just doesn’t understand it. he has so much love to feel for you that there was simply no room for criticism. “and even if for some reason they didn’t, that does not measure who you are as a person. and for the record — you are incredible,” he motioned your face towards his using his thumb on your chin. “you are — beyond any words — the best person anyone could have in their life.” he slid his hand to your shoulder, gently rubbing your arm in a soothing manner, where you melted into his touch.

you sighed, your eyes looking down. “i wish it were easier for me to believe that.” you replied in a raspy voice. sonic stood up in front of you, looking down into your eyes. cupping your face in his hands, he stroked his thumbs over your flushed cheeks.

“you made a difference here, genuinely. you gave purpose to our lives just by being who you are. you’re a flower amidst a desert. all of that .. err, stuff,” you couldn’t help but snicker at him, your eyes glossy and full of love. he smiled warmly, one of his hands running its fingers through your hair, admiring you.

“i like everything about you. every flaw and corny joke you make, every clumsy step and hearty laugh. it’s hard to admire someone when there’s nothing to them, but you have everything,” sonic pressed a kiss to your forehead, then to your ear, “you’re enough, and everything more than that.” he lifted his head to look at you, his heart melting as he noticed a few tears running down your cheeks. your lips twitched as you peered through your wet eyelashes, sniffling softly.

“i’m sorry, im sorry im sorry —“ you repeated quietly on a chain, sonic whimpering quietly in response. it broke him to see you cry.

“hey hey you have nothing to be sorry for, hey..” he held your head against his chest as you cried, stroking your hair and maneuvering his way back to sitting beside you so he could hold you.

he let you cry for a moment as you caught your breath and wiped your tears with the back of your hand, regaining your composure.

“i’m so sorry, i-im such a wreck, i know you ju…just wanted to hang out with your friends,” you rambled, but sonic just stared, his eyes gazing over you.

“god, you’re beautiful.” he whispered, catching you off guard, you looked at him, snot covering your nose, your face wet and hair disheveled.

“what?” you asked weakly, confused. sonic reached for your hand, taking it to his mouth, kissing your knuckle.

“it’s moments like these where i can see who you really are, and i see you.” his last words made your heart palpitate. i see you. words you didn’t even know you needed to hear. he smiled, keeping your hand close to him.

“and you’re just glowing. you don’t even see it.” he added, making you smile and look away.

“you’re such a … i don’t even know.” you laughed through your teeth, wiping your face again. sonic tucked your hair behind your ear.

“let’s stay in tonight.” he suggested, but you were quick to protest.

“no, no, we can’t cancel last minute. i’m fine, we can go—“

“mm, i’d rather spend the rest of tonight loving you, okay? please?” his tone was rather persuasive, and you looked a little taken aback.

“i, uh… can’t really say no to that.” you replied which gained sonics classic smirk.

“it’s settled. i’ll go call tails.” he got up. heading to the door but looking behind his shoulder before he left.

‘i love you’ he mouthed, earning a shy chuckle from you and a sniffly ‘i love you more’ back. ♥︎

#sonic fanfiction#sonic the hedgehog#sonicssweetheart#digital diary#fanfic#sonic oneshots#requests open#sonic self ship#sonic angst#sonicxinsecurereader#oneshot#send reqs#sonic prime#sonic boom#sonic fluff#sonic headcanons#sonic fandom#sonic x reader

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newell Park. I’ve been sorely neglecting my visits, but I’m not too late to see the oak blooms. This visit, I identified a number of other trees (not featured) including the Ohio buckeye, common chokecherry, elm, and redbud.

Featured are new fronds my bur oak friend is growing, the fact that my pin oak friend looks like a dryad from afar, and a deep hollow in one of the trees on the park’s southeaster corner. Last image is taken from my favorite bench in the park. Trying to catch what it looks like in every season.

0 notes

Text

like anyone with good taste, I adore late 15th century Flemish millefleur tapestries

So here's a bur oak with savanna species in the shade, and prairie in the sun

Prints et al available here!

781 notes

·

View notes

Text

chapter 7's gonna be fun

Sometimes, sitting in this chair, Gale feels like a schoolboy called to the principals office. Or how he assumes it would feel. He’d been a well-behaved child, and the only times he’d ever found himself in a chair in front of the principal it had not been him that was in trouble. But under the not-so-stern scrutiny he feels picked apart, placed on a glass tray and thrown under the bright light of a microscope.

He picks at his cuticles, both thumbs gone chapped and bloody, the skin swollen, red, puffy, skin flaking off in spots that will turn to agony if he tugs on them. Gale places one thumb between his teeth, nibbles away the temptation of the peel. The string of saliva left upon separation is tinged pink.

“How are you doing today, Gale?”

“I don’t want to answer that.”

Helen sits back, crossing her legs, “And you’re under no obligation to.”

“Have you ever had venison?” he asks, “Not– not the stuff you get at the grocery store. Real Venison.”

She shakes her head.

“You taste it. You taste everything the deer’s ever eaten. Sweet from berries, and a tang from the bark the strip in the winter. My dad got one year that’d been feasting in a copse of bur oaks. You could taste it, taste the nuttiness. That they’d gone a little sweet and fermented.”

“Did you go hunting with your father often?”

“No,” Gale huffs, a bit of a smile that felt anything but pleasant. “No, he said I was too soft.”

The clock ticks on the wall, a soft mechanical heartbeat. Gale times his breaths with it.

He picks at his thumb again, “I dreamt about it again last night.”

To her credit, Helen doesn’t react. And she doesn’t speak either, which Gale is grateful for. He feels a bit like he’s walking across an iced-over puddle at the moment. The barrier barely thick enough to shoulder his weight, cracks spreading out like lacework. He has to tread carefully.

“I dreamt about the dog. And the field.”

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some sew-on leaf patches: bur oak, bigtooth aspen, sugar maple, red maple on scrap denim. Making a few more of these for market season.

199 notes

·

View notes