#brazil environmental policy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

The Dark Side of Brazil - The Dark Truth Exposed | geography facts

In this video, we'll be taking a look at the dark side of Brazil. Explore the social inequality issues, environmental challenges, and corruption that persist in this captivating nation. Discover the lesser-known aspects of Brazil and the human rights issues that have recently come to light. By the end of this video, you'll have a better understanding of the hidden side of Brazil and how you can contribute to addressing these issues.

#brazil's environmental problems#human rights violations in brazil#environmental issues in brazil#brazil political corruption#the dark side of brazil#brazil economic crisis#brazil environmental policy#brazil financial crisis#brazil economic problems#human rights issues in brazil#brazil history#brazil economy#dark side of brazil#brazil social inequality#corruption in brazil#geography guru#geography facts#brazil facts#negative sides of living in Brazil#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lula and Biden to announce clean energy partnership, defying Trump

The bilateral meeting between Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and U.S. President Joe Biden on the 19th will unveil a significant joint initiative on energy transition, a top priority for both leaders, according to official sources confirmed by GLOBO. Brazil's message is clear, official sources noted: "Regardless of the outcome" of the recent U.S. elections, which paved the way for Republican Donald Trump's return to the White House on January 20, "the Lula administration will uphold the agenda it's been building with the U.S."

Trump neglected the energy transition during his first term (2017-2021), and the topic lost steam following his election, but despite the evident disappointment his victory caused within the Brazilian government, the Presidential Palace and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have kept their plans for the bilateral meeting between the two heads of state intact.

The agreement will be similar to the Partnership for Workers' Rights announced by the two presidents in September 2023, which will also be part of the agenda of topics to be discussed by Lula and Biden in Rio. The energy transition partnership began being developed in early 2024, with the intention of starting implementation in 2025.

Combating climate change is a key topic in the shared agenda of Lula's Brazil and Biden's U.S., and it is expected to become a point of contention between the Brazilian president and Trump. Government sources admitted that "the future of the initiative is uncertain, but it will be announced." One goal is to change the energy matrix of both countries and promote renewable alternatives. Teams from both governments will begin working on an action plan that opposes Trump's energy vision. "We will advocate for clean energies, discuss biofuels, green hydrogen, electric cars," commented one of the consulted sources. This vision is far from the American president-elect, a proponent of fossil fuels and considered a climate change denier by environmentalists.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#united states#us politics#luiz inacio lula da silva#joe biden#foreign policy#international politics#environmentalism#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's the top 2 stories from each of Fix The News's six categories:

1. A game-changing HIV drug was the biggest story of 2024

In what Science called the 'breakthrough of the year', researchers revealed in June that a twice-yearly drug called lenacapavir reduced HIV infections in a trial in Africa to zero—an astonishing 100% efficacy, and the closest thing to a vaccine in four decades of research. Things moved quick; by October, the maker of the drug, Gilead, had agreed to produce an affordable version for 120 resource-limited countries, and by December trials were underway for a version that could prevent infection with just a single shot per year. 'I got cold shivers. After all our years of sadness, particularly over vaccines, this truly is surreal.'

2. Another incredible year for disease elimination

Jordan became the first country to eliminate leprosy, Chad eliminated sleeping sickness, Guinea eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus, Belize, Jamaica, and Saint Vincent & the Grenadines eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, India achieved the WHO target for eliminating black fever, India, Viet Nam and Pakistan eliminated trachoma, the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness, and Brazil and Timor Leste eliminated elephantiasis.

15. The EU passed a landmark nature restoration law

When countries pass environmental legislation, it’s big news; when an entire continent mandates the protection of nature, it signals a profound shift. Under the new law, which passed on a knife-edge vote in June 2024, all 27 member states are legally required to restore at least 20% of land and sea by 2030, and degraded ecosystems by 2050. This is one of the world’s most ambitious pieces of legislation and it didn’t come easy; but the payoff will be huge - from tackling biodiversity loss and climate change to enhancing food security.

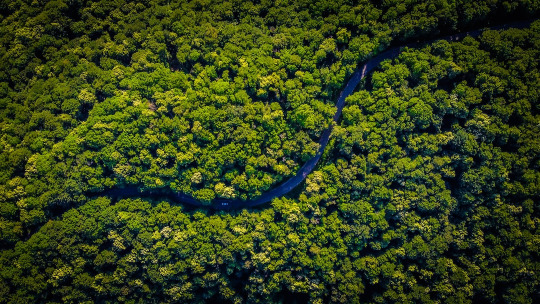

16. Deforestation in the Amazon halved in two years

Brazil’s space agency, INPE, confirmed a second consecutive year of declining deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. That means deforestation rates have roughly halved under Lula, and are now approaching all time lows. In Colombia, deforestation dropped by 36%, hitting a 23-year low. Bolivia created four new protected areas, a huge new new state park was created in Pará to protect some of the oldest and tallest tree species in the tropical Americas and a new study revealed that more of the Amazon is protected than we originally thought, with 62.4% of the rainforest now under some form of conservation management.

39. Millions more children got an education

Staggering statistics incoming: between 2000 and 2023, the number of children and adolescents not attending school fell by nearly 40%, and Eastern and Southern Africa, achieved gender parity in primary education, with 25 million more girls are enrolled in primary school today than in the early 2000s. Since 2015, an additional 110 million children have entered school worldwide, and 40 million more young people are completing secondary school.

40. We fed around a quarter of the world's kids at school

Around 480 million students are now getting fed at school, up from 319 million before the pandemic, and 104 countries have joined a global coalition to promote school meals, School feeding policies are now in place in 48 countries in Africa, and this year Nigeria announced plans to expand school meals to 20 million children by 2025, Kenya committed to expanding its program from two million to ten million children by the end of the decade, and Indonesia pledged to provide lunches to all 78 million of its students, in what will be the world's largest free school meals program.

50. Solar installations shattered all records

Global solar installations look set to reach an unprecedented 660GW in 2024, up 50% from 2023's previous record. The pace of deployment has become almost unfathomable - in 2010, it took a month to install a gigawatt, by 2016, a week, and in 2024, just 12 hours. Solar has become not just the cheapest form of new electricity in history, but the fastest-growing energy technology ever deployed, and the International Energy Agency said that the pace of deployment is now ahead of the trajectory required for net zero by 2050.

51. Battery storage transformed the economics of renewables

Global battery storage capacity surged 76% in 2024, making investments in solar and wind energy much more attractive, and vice-versa. As with solar, the pace of change stunned even the most cynical observers. Price wars between the big Chinese manufacturers pushed battery costs to record lows, and global battery manufacturing capacity increased by 42%, setting the stage for future growth in both grid storage and electric vehicles - crucial for the clean flexibility required by a renewables-dominated electricity system. The world's first large-scale grid battery installation only went online seven years ago; by next year, global battery storage capacity will exceed that of pumped hydro.

65. Democracy proved remarkably resilient in a record year of elections

More than two billion people went to the polls this year, and democracy fared far better than most people expected, with solid voter turnout, limited election manipulation, and evidence of incumbent governments being tamed. It wasn't all good news, but Indonesia saw the world's biggest one day election, Indian voters rejected authoritarianism, South Korea's democratic institutions did the same, Bangladesh promised free and fair elections following a 'people's victory', Senegal, Sri Lanka and Botswana saw peaceful transfers of power to new leaders after decades of single party rule, and Syria saw the end of one of the world's most horrific authoritarian regimes.

66. Global leaders committed to ending violence against children

In early November, while the eyes of the world were on the US election, an event took place that may prove to be a far more consequential for humanity. Five countries pledged to end corporal punishment in all settings, two more pledged to end it in schools, and another 12, including Bangladesh and Nigeria, accepted recommendations earlier in the year to end corporal punishment of children in all settings. In total, in 2024 more than 100 countries made some kind of commitment to ending violence against children. Together, these countries are home to hundreds of millions of children, with the WHO calling the move a 'fundamental shift.'

73. Space exploration hit new milestones

NASA’s Europa Clipper began a 2.9 billion kilometre voyage to Jupiter to investigate a moon that may have conditions for life; astronomers identified an ice world with a possible atmosphere in the habitable zone; and the James Webb Telescope found the farthest known galaxy. Closer to Earth, China landed on the far side of the moon, the Polaris Dawn crew made a historic trip to orbit, and Starship moved closer to operational use – and maybe one day, to travel to Mars.

74. Next-generation materials advanced

A mind-boggling year for material science. Artificial intelligence helped identify a solid-state electrolyte that could slash lithium use in batteries by 70%, and an Apple supplier announced a battery material that can deliver around 100 times better energy density. Researchers created an insulating synthetic sapphire material 1.25 nanometers thick, plus the world’s thinnest lens, just three atoms across. The world’s first functioning graphene-based semiconductor was unveiled (the long-awaited ‘wonder material’ may finally be coming of age!) and a team at Berkeley invented a fluffy yellow powder that could be a game changer for removing carbon from the atmosphere.

-via Fix The News, December 19, 2024

#renumbered this to reflect the article numbering#and highlight just how many stories of hope there are#and how many successes each labeled story contains#2024#good news#hope#hope posting#hopeposting#hopepunk#conservation#sustainability#public health#energy#quality of life#human rights#science and technology

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Best News of Last Week

1. Arizona governor Ok's over the counter birth control

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs (D) has expanded access to over-the-counter birth control that will “soon be available to Arizonans,” according to a press release.

Arizonans 18 and older will soon be able to go to their local pharmacy and purchase oral contraceptives without a doctor’s prescription.

2. ‘Great news’: EU hails discovery of massive phosphate rock deposit in Norway

A massive underground deposit of high-grade phosphate rock in Norway, pitched as the world’s largest, is big enough to satisfy world demand for fertilisers, solar panels and electric car batteries over the next 50 years, according to the company exploiting the resource. About 90% of the world’s mined phosphate rock is used in agriculture for the production of phosphorous for the fertiliser industry, for which there is currently no substitute.

3. U.S. Is Destroying the Last of Its Once-Vast Chemical Weapons Arsenal

Decades behind its initial schedule, the dangerous job of eliminating the world’s only remaining declared stockpile of lethal chemical munitions will be completed as soon as Friday.

4. Chinese scientists create edible food packaging to replace plastic

By incorporating certain soy proteins into the structure, Chinese University of Hong Kong scientists successfully created edible food packaging.

5. World's 1st 'tooth regrowth' medicine moves toward clinical trials in Japan

A Japanese research team is making progress on the development of a groundbreaking medication that may allow people to grow new teeth, with clinical trials set to begin in July 2024. The tooth regrowth medicine is intended for people who lack a full set of adult teeth due to congenital factors.

6. No Longer Endangered: The Bald Eagle is an Icon of the ESA

When the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was enacted in 1973, bald eagle population numbers across the country showed that the species was close to disappearing. Before the ESA, in the 1950s and ‘60s, eagles were shot routinely despite the protection. The ESA listing helped bring public attention to the issue.

Through the early 1970s and into the early ‘80s, numbers increased gradually. Then, as you got into the ‘90s, there was still gradual growth. From the late ‘90s into the 2000s, the population really exploded. There was a doubling rate of every several years or so for a while.

7. Deforestation in Brazil's Amazon drops 34% in first half 2023

Deforestation in Brazil's Amazon fell 34% in the first half of 2023, preliminary government data showed on Thursday, hitting its lowest level in four years as President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva institutes tougher environmental policies.

Data produced by Brazil's national space research agency Inpe indicated that 2,649 square km (1,023 square miles) of rainforest were cleared in the region in the half year, the lowest for the period since 2019.

----

That's it for this week :)

This newsletter will always be free. If you liked this post you can support me with a small kofi donation:

Support this newsletter ❤️

Also don’t forget to reblog.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

The agricultural lobby is a sprawling, complex machine with vast financial resources, deep political connections and a sophisticated network of legal and public relations experts. “The farm lobby has been one of the most successful lobbies in Europe in terms of relentlessly getting what they want over a very long time,” says Ariel Brunner, Europe director of non-governmental organisation BirdLife International. Industry groups spend between €9.35mn and €11.54mn a year lobbying Brussels alone, according to a recent report by the Changing Markets Foundation, another NGO. In the US, agricultural trade associations are “enormously powerful”, says Ben Lilliston, director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. “Our farm policy is very much their policy.” The sector’s spending on US lobbying rose from $145mn in 2019 to $177mn last year, more than the total big oil and gas spent, according to an analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). In Brazil, where agribusiness accounts for a quarter of GDP, the Instituto Pensar Agropecuária is “the most influential lobbying group”, according to Caio Pompeia, an anthropologist and researcher at the University of São Paulo. “It combines economic strength with clearly defined aims, a well-executed strategy and political intelligence,” he adds. As a result of this reach, big agribusinesses and farmers have successfully secured exemptions from stringent environmental regulations, won significant subsidies and maintained favourable tax breaks.

[...]

Research suggests that big farms and landowners reap far greater benefits from subsidy packages than small-scale growers, even though the latter are often the public face of lobbying efforts. “It’ll almost always be a farmer testifying before Congress or talking to the press, rather than the CEO of JBS,” says Lilliston. But between 1995 and 2023, some 27 per cent of subsidies to farmers in the US went to the richest 1 per cent of recipients, according to NGO the Environmental Working Group. In the EU, 80 per cent of the cash handed out under the CAP goes to just 20 per cent of farms.

22 August 2024

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seed networks are community organizations that have multiplied in the past decade in different Brazilian biomes to collect, trade and plant native seeds in degraded areas.

In the Chapada dos Veadeiros area, in Goiás state members of seed networks from several parts of Brazil met for almost a week in early June.

Along with environmental organizations, researchers and government officials, they participated in discussions to boost Redário, a new group seeking to strengthen these networks and meet the demands of the country’s ecological restoration sector.

“This meeting gathered members of Indigenous peoples, family farmers, urban dwellers, technicians, partners, everyone together. It creates a beautiful mosaic and there’s a feeling that what we are doing will work and will grow,” says Milene Alves, a member of the steering committee of the Xingu Seed Network and Redário’s technical staff.

Just in 2022, 64 metric tons of native seeds were sold by these networks, and similar figures are expected for 2023.

The effort to collect native seeds by traditional populations in Brazil has contributed to effective and more inclusive restoration of degraded areas, and is also crucial for the country to fulfill its pledge under international agreements to recover 30 million acres of vegetation by 2030.

Seed collection for restoration in these areas has previously only been done by companies. But now, these networks, are organized as cooperatives, associations or even companies, enable people in the territories to benefit from the activity.

Eduardo Malta, a restoration expert from the Socio-Environmental Institute and one of Redário’s leaders, advocates for community participation in trading and planting seeds. “These are the people who went to all the trouble to secure the territories and who are there now, preserving them. They have the greatest genetic diversity of species and hold all the knowledge about the ecosystem,”

.

The Geraizeiros Collectors Network are one of the groups that makes up Redário. They were founded in 2021, and now gathers 30 collectors from eight communities in five municipalities: Montezuma, Vargem Grande, Rio Pardo de Minas, Taiobeiras and Berizal.

They collect and plant seeds to recover the vegetation of the Gerais Springs Sustainable Development Reserve, which was created in 2014 in order to stop the water scarcity as a result of eucalyptus monocultures planted by large corporations.

“The region used to be very rich in water and it is now supplied by water trucks or wells,” says Fabrícia Santarém Costa, a collector and vice president of the Geraizeiros Collectors’ Network. “Today we see that these activities only harm us, because the [eucalyptus] company left, and we are there suffering the consequences.”

Costa was 18 years old in 2018, when the small group of seed collectors was founded and financed by the Global Environmental Facility. She says that working with this cooperative changed the way she looks at life and the biome in which she was born and raised. She describes restoring the sustainable development work as "ant work", ongoing, slow. But it has already improved the water situation in the communities. In addition, seed sales complement geraizeiros’ income, enabling them to remain in their territories.

.

The Redário initiative also intends to influence public policies and regulations in the restoration sector to disseminate muvuca, the name given by the networks to the technique of sowing seeds directly into the soil rather than growing seedlings in nurseries.

Technical studies and network experiences alike show that this technique covers the area faster and with more trees. As a result, it requires less maintenance and lower costs. This system also distributes income to the local population and encourages community organizations.

“The muvuca system has great potential [for restoration], depending on what you want to achieve and local characteristics. It has to be in our range of options for meeting the targets, for achieving them at scale,” says Ministry of the Environment analyst Isis Freitas.

Article published August 3rd, 2023

#long post#climate change#climate#hope#good news#more to come#climate emergency#positive news#hopeful#climate justice#news#important#good post#links

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

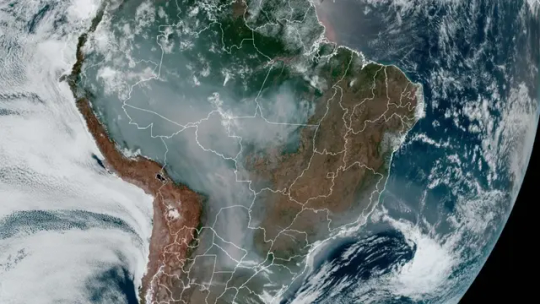

Smoke clouds and deforastation in Brasil - Mundane Astrology

Disclaimer: This post was mostly written in the beginning of September 2024. It was a very scary time and I just couldn't finish it until now that I'm better.

I don't know if you got the news that South America got covered with smoke clouds since at least the beginning of August, as huge areas in the Pantanal and the Amazon are burning. I promised to make posts based on the suggestions some of you made, but this is all that's been on my mind lately, because I'm smelling fire every day even as I live in a coastal city that's nowhere near them. I have a bit of a cough since June when I had a cold and then the cough persisted. Some days it was gone, but since the smoke clouds it's been consistent. I've never seen anything like it, an entire country and neighboring countries covered in smoke. To be clear, the fires are not natural, they are criminal acts, they are started for land grabbing and also probably as retaliation for the environmental protection policies of our current left-leaning government. This is also greatly done on indigenous lands. It all started after months of brutal attacks on the Guarani Kaiowá in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, all the while threats like the Time Frame thesis are still being pushed. It's making me feel like how we all felt in those days in the beginning of the covid pandemic, when we thought we were just going to stay home for 15 days, but a sense of doom was slowly creeping, because that number just kept getting bigger until we didn't know anymore. It's been making me feel sad, angry and fearful.

Smoke in São Paulo and Goiás. The Sun looked like that for days in my town as well.

I won't talk about Brazil's chart in depth¹, but it's important to talk a little bit about the ruler of that chart, which is Saturn in Taurus in the 4th house and the Moon with Aldebaran, the star of the bull's eye. This country is marked by its agrarian issues and the inequality in the distribution of land ownership in Brazil is one of the most pronounced in the world. The largest portions of land remains in the hands of a very tiny portion of the population, who are the richest and major producers of agribusiness, while they destroy forests and invade indigenous territory. That Saturn in Taurus in the 4th shows how the project for this country at the declaration of independence was still a perpetuation of colonization, and also how we were supposed to be a peaceful people, just meant to work, to be enslaved and tame like our cattle. Brazil still has a reputation of being very festive, happy and peaceful, even as we are built on so much violence².

From outside people mostly see Rio de Janeiro and beach culture as the postcard of the country, but that disguises the greater countryside culture of deep Brazil, which is incredible but not as marketable for tourism, and it's actually hard not to see it tainted with the violence of agribusiness. As it's obvious from our very strong barbecue culture, Brazil is a leader in the export of meat and soy, and the latter is actually because it's greatly used for cattle feed. When you hear about deforestation in the brazilian part of the Amazon, or about the destruction of any natural area of this country, it's always criminal fires started by powerful landowners trying to expand their areas of agribusiness, especially for soybean plantation and for livestock, perpetuating the genocide of indigenous people, who are the most interested in protecting nature, but still don't have their lands demarcated and their rights protected without the threat of extermination.

Because of all of that, whenever we see the 4th house greatly activated for the year it's scary. The 4th house is about the forests, land and indigenous peoples. Looking at the Solar Ingress into Aries for Brasília, the country is ruled mainly by the Sun and has Mercury as the co-ruler this year.

The Sun was scorching the earth in the 4th house. In 2020 we also had the Sun in the 4th house and that was a historic year in terms of huge fires and deforestation too, when a third of the Pantanal biome was burned, so it checks out that the Sun in the 4th unfortunately signifies these things for this country in these times. Besides, Mars is the 4th house ruler, and it's in the 2nd house affecting resources, and we'll definitely see a rise in food prices because of what's happening pretty soon, which are already high. I consider its placement in Aquarius important, as Ísis notices often the recurrence of air signs in charts for fires, because they help it spread and thrive, especially the fixed air sign. The Moon in another fire sign in the 8th house doesn't help at all.

However, the IC is in Pisces with Venus and Saturn, while Mars will eventually reach them. Three weeks after the Solar Ingress, Mars met Saturn at 14° Pisces. One of the most important conjunctions to watch for in Mundane Astrology is the Mars-Saturn one, which is famous for signifying calamity and disease. Soon after the conjunction, the Full Moon in Scorpio came with those two in the 4th house. That's when we had the historic floods in Rio Grande do Sul, one of the most horrible environmental disasters we've seen. I've written about it here. The mix of fire and water signified a year with one of the worst floods and at the same time one of the worst droughts ever.

But now we're in the winter, thus we need to open up the chart for the Cancer Solar Ingress. It has the same rising sign, but this time Saturn is much more angular, and also stationary and about to go retrograde. Saturn on the IC is the co-ruler for the winter trimester.

Saturn is closer to the IC, making it a lot more powerful. He's stationary and about to go retrograde. Pretty soon he'll reach 15° Pisces where the fixed star Achernar is at and where it had its conjunction with Mars earlier in the year. Achernar is the alpha star of the constellation of the river Eridanus, which tells the myth of Phaethon, who drove the sun god Helios' chariot too close to the Earth and burned it. He gets striked by Zeus with his lighting bolt and his body falls into the river Eridanus.

Mars is still ruling the 4th house representing land and forests. He's in Taurus with the fixed star Hamal, the head of the Ram, which has his nature. So even though it's in Taurus, Mars is still very much himself. If we imagine the planets moving through the chart, we soon understand that Jupiter is going to square Saturn at some point, and Mars will do the same.

After the New Moon in Leo is when the fires got really wild and we got the smoke cloud covering almost the entire continent. On August 14 there was one big trigger for this: the Mars-Jupiter conjunction at 16° Gemini squaring Saturn. Nothing more symbolic of a continent-sized cloud of smoke above our heads than Mars-Jupiter in an air sign on top of the MC. As I've said, these are not wild fires, they're being coordinated, some were on caught on camera, that's why we see the 12th house activated, as it indicates hidden enemies and criminal activity.

Things got worse with the Full Moon, which was at 27° Aquarius, the exact degree of that Mars of the Aries Ingress chart. And this is where we're still at. I'm still smelling fire most of the time, especially at night for some reason, because I guess at night the air changes or something, I don't think anyone is trying to explain this enough. The sky looks like it's completely clouded, but the Sun is orange and its light is direct. I'm still coughing.

Aftermath

This is a very scary thing to just throw at you, so for anyone who cares about environmental issues I'll leave some more links about research that were made, measures that are being taken until now, things you could look up, follow or read about, etc.

278.3 thousand fire outbreaks registered in 2024;

The government strategies that are being taken;

Mídia Indígena - An indigenous communication collective from Brazil;

Articulação do povos indígenas do Brasil, an association of entities representing indigenous people;

About the struggle for land in Brazil and MST , the largest popular movement in Latin America, which is aimed at land reform;

Ailton Krenak, legendary indigenous leader of the krenak people, environmentalist and author of "Ideas to Postpone the end of the World", "Ancestral Future", "Life is Not Useful" etc;

Davi Kopenawa, yanomami political leader and author of "The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman";

Marina Silva, the current Minister of Environment and Climate Change, a very important politician in our environmental politics;

Ministry of the Indigenous Peoples, presided by Sônia Guajajara.

-----

¹ We mostly use the 1822 chart of the Declaration of Independence, although there are other important ones.

² Zé Ramalho captured our Taurean project pretty well in song: Admirável Gado Novo.

#mundane astrology#astrology readings#brazilian politics#climate change#latin american politics#environmental politics#pantanal#traditional astrology#hellenistic astrology#fixed stars#indigenous peoples#indigenous rights#climate crisis#reforma agraria

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

COP29 NOV 11--Blue Zone

review of the notes from my first day of the UN COP29 Climate Change Conference. Disclaimer I'm just a ~silly guy~ not a policy or geopolitical expert. My observations and opinions do not reflect AC or RINGOs. This is what I witnessed, overheard, remember, and (crucially) understand, and may not be representative of final policy decisions.

I was in the Blue Zone today (official UN ground, where negotiations occur). From the RINGO meeting, rumor was the night before COP29 officially began officials were up till 4 am arguing about the agenda. Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement (mechanisms of carbon markets) was deeply contested in particular. Also arguments about unilateral and multilateral trade agreements. Also weather Global Stocktake (assessment of global progress on Paris Agreement) would be filed under general or financial sections. US/EU/Australia/smaller island nations were wanting it to be considered broader, with BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) wanting it under strictly Finance. More Paris Agreement stuff.

This resulted in the opening plenary beginning at 11 am, followed immediately by break for closed door discussions on the second item of the day, the agenda. This was a completely unprecedented delay, and the agenda was only resolved at 9pm.

This is the previous COP president Sultan Al Jaber, who did the opening address of plenary and handed over the presidency to Muhktar Babayev (photo below) with an embrace.

Notes of claims from Babayev's address to the plenary body:

We are set to break records on renewable energy and its investment.

There is a goal of low-carbon growth (as opposed to zero, which I think is an important distinction)

853 million put into the Loss and Damage fund

A call to increase climate financing ambitions. This is not charity, but in the self interest of all countries who with to mitigate the ethical and economical consequences of climate change.

A reinforcement of the call to transition away from fossil fuels (important, as last year is the first time such phrasing was used for the UNFCCC)

Emphasizing the cooperation required of everyone.

Genocide and the environment

Social justice is deeply tied into climate change efforts. Here in the Blue Zone we had a demonstration to end genocide (as relevant by its massive carbon emissions, if the human rights angle doesn't suffice), with particular emphasis on Palestine and reclaiming Indigenous lands. Demonstrations within the blue zone are allowed with permission, and can have a maximum of 20 people actively participating. Those in solidarity of the demonstration raised their fists in support. Also, this could not happen in the Green Zone (public conference) due to it being controlled by the host country, and Azerbaijan has strict laws against protests.

USAmerican election and its future climate policy

I proceeded to get rather lost trying to find a conference on USAmerican climate response to the Trump election, but got there too late because the Blue Zone is massive oof. Did catch the people coming out, and the strategy thus far is that the Biden administration's environmental policies were designed to endure regime shifts and should be difficult to undo without significant political effort. So, we'll be unfortunately testing that durability, particularly with how Trump likes to flout the rules and the Supreme Court deemed that legal.

Additionally, NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) are due in February but the US may potentially do theirs sooner before the regime shift. Effectiveness is questionable because the accountability of countries upholding their NDCs is already kinda honor code.

Subfederal action is going to be a main proponent of climate action from here on.

Conference: Transparency for transforming the agrifood system

I...must admit I was constantly blacking out and jerking back awake during this meeting because of jet lag. So the merit of these notes may be questionable particularly bc I'm having trouble reading them. However, notes from representatives from Mongolia, Pakistan, Georgia, UN, and others.

10% of global green house gas emissions are from agriculture (Technically this was from Babayev's speech but I think it's a useful reference point for this conversation. Production, manufacturing, distribution, and waste of food produces a lot of emissions).

Data quality is of large concern for transparency and effectiveness of implementation purposes. Countries have different methodologies and argue about which is superior, and the quality of others' methods. This can be particularly of note in the carbon markets. Data collection is a large logistical and technological challenge.

Everyone wants increased transparency. Or claim to. I think, aside from technical difficulties in data collection and funding thereof, the countries would actually prefer others are transparent and less themselves to be. As evidenced by things like high levels of methane unaccounted by the summation of all countries' submitted emission reports. But that's just my opinion.

BTRs (Biennial transparency reports) are difficult, and the country representatives present were apologizing for delays.

Calls for increase of human capacity. Imma be level that seems like a vague ideal to me, but I think it might mean carrying capacity (kinda a deeply flawed concept already, sustainability is extremely difficult to ascertain without prolonged unsustainability to confirm it)

Double counting is a problem for carbon removals

Efforts to work with farmers in data collection and to better improve their methods

A claim on carbon neutral livestock farming to balance cattle methane emissions with soil carbon sequestering through grazingland ecosystem management.

Conversion of carbon sink ecosystems into farmland. From personal research: In 2019, 17% of global cropland was newly converted since 2003, and the rate of yearly conversion is accelerating.

Potentially using IPCC software for consistency in data collection and analysis

Ecocide as a tool of war

Lastly, there are country pavilions in the Blue Zone where they raise issues. I did not particularly look too much into most of them, but would like to share Ukraine's because it was amazing imo.

One, the walls are literally full of seeds, and I think it will be really cool seeing them begin to sprout by the end of the conference

Two, how destroying the environment is a concentrated effort to destroy its people. Because again, protecting the environment/climate is protecting the people.

Lastly, these solar panels damaged in the war. A large emphasis in this pavilion was rebuilding from the bombing and coming back greener, which I found particularly admirable. The bravery to forge something new while grieving the comfort of what was lost. The circumstances presenting the opportunity to reinvent their infrastructure is obviously horrendous, but seizing said opportunity nonetheless is inspiring. Renewable energy is also a way to be energy independent, which is particularly important if you’re say Ukraine and the closest major oil exporter is Russia.

Now, I had left the Blue Zone by then (needed dinner where there isn't price gouging! Yikes!) but plenary did eventually assume very late, and massive progress on Article 6 was made!

This is about Carbon Markets, some people are happy others aren't, etc. Also the agenda was implement as the original plan (GST under finance) with acknowledgements made that it was broader consideration. And now plenary can actually continue instead of being stymied! In consideration for the day of lost time, sessions will run later than usual. After today it's going to get busy!

#nom does politics#cop29#unfccc#climate change#climate change action#environment#politics#world politics#UN#united nations#us election 2024#ecosystem#agriculture#genocide#uhguhgpidh This took so much time and it's NOTHING compared to how much I did nov 12#something to nom on

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHANGHAI — Over the past generation, China’s most important relationships were with the more developed world, the one that used to be called the “first world.” Mao Zedong proclaimed China to be the leader of a “third” (non-aligned) world back in the 1970s, and the term later came to be a byword for deprivation. The notion of China as a developing country continues to this day, even as it has become a superpower; as the tech analyst Dan Wang has joked, China will always remain developing — once you’re developed, you’re done.

Fueled by exports to the first world, China became something different — something not of any of the three worlds. We’re still trying to figure out what that new China is and how it now relates to the world of deprivation — what is now called the Global South, where the majority of human beings alive today reside. But amid that uncertainty, Chinese exports to the Global South now exceed those to the Global North considerably — and they’re growing.

The International Monetary Fund expects Asian countries to account for 70% of growth globally this year. China must “shape a new international system that is conducive to hedging against the negative impacts of the West’s decoupling,” the scholar and former People’s Liberation Army theorist Cheng Yawen wrote recently. That plan starts with Southeast Asia and extends throughout the Global South, a terrain that many Chinese intellectuals see as being on their side in the widening divide between the West and the rest.

“The idea is that what China is today, fast-growing countries from Bangladesh to Brazil could be tomorrow.”

China isn’t exporting plastic trinkets to these places but rather the infrastructure for telecommunications, transportation and digitally driven “smart cities.” In other words, China is selling the developmental model that raised its people out of obscurity and poverty to developed global superpower status in a few short decades to countries with people who have decided that they want that too.

The world China is reorienting itself to is a world that, in many respects, looks like China did a generation ago. On offer are the basics of development — education, health care, clean drinking water, housing. But also more than that — technology, communication and transportation.

Back in April, on the eve of a trip to China, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva sat down for an interview with Reuters. “I am going to invite Xi Jinping to come to Brazil,” he said, “to get to know Brazil, to show him the projects that we have of interest for Chinese investment. … What we want is for the Chinese to make investments to generate new jobs and generate new productive assets in Brazil.” After Lula and Xi had met, the Brazilian finance minister proclaimed that “President Lula wants a policy of reindustrialization. This visit starts a new challenge for Brazil: bringing direct investments from China.” Three months later, the battery and electric vehicle giant BYD announced a $624 million investment to build a factory in Brazil, its first outside Asia.

Across the Global South, fast-growing countries from Bangladesh to Brazil can send raw materials to China and get technological devices in exchange. The idea is that what China is today, they could be tomorrow.

At The Kunming Institute of Botany

In April, I went to Kunming to visit one of China’s most important environmental conservation outfits — the Kunming Institute of Botany. Like the British Museum’s antiquities collected from everywhere that the empire once extended, the seed bank here (China’s largest) aspires to acquire thousands of samples of various plant species and become a regional hub for future biotech research.

From the Kunming train station, you can travel by Chinese high-speed rail to Vientiane; if all goes according to plan, the line will soon be extended to Bangkok. At Yunnan University across town, the economics department researches “frontier economics” with an eye to Southeast Asian neighboring states, while the international relations department focuses on trade pacts within the region and a community of anthropologists tries to figure out what it all means.

Kunming is a bland, air-conditioned provincial capital in a province of startling ethnic and geographic diversity. In this respect, it is a template for Chinese development around Southeast Asia. Perhaps in the future, Dhaka, Naypyidaw and Phnom Penh will provide the reassuring boredom of a Kunming afternoon.

Imagine you work at the consulate of Bangladesh in Kunming. Why are you in Kunming? What does Kunming have that you want?

The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lyrically described Asia’s communities as organic and spiritual in contrast with the materialism of the West. As Tagore spoke of the liberatory powers of art, his Chinese listeners scoffed. The Chinese poet Wen Yiduo, who moved to Kunming during World War II and is commemorated with a statue at Yunnan Normal University in Kunming, wrote that Tagore’s work had no form: “The greatest fault in Tagore’s art is that he has no grasp of reality. Literature is an expression of life and even metaphysical poetry cannot be an exception. Everyday life is the basic stuff of literature, and the experiences of life are universal things.”

“Xi Jinping famously said that China doesn’t export revolution. But what else do you call train lines, 5G connectivity and scientific research centers appearing in places that previously had none of these things?”

If Tagore’s Bengali modernism championed a spiritual lens for life rather than the materiality of Western colonialists, Chinese modernists decided that only by being more materialist than Westerners could they regain sovereignty. Mao had said rural deprivation was “一穷二白” — poor and empty; Wen accused Tagore’s poetry of being formless. Hegel sneered that Asia had no history, since the same phenomena simply repeated themselves again and again — the cycle of planting and harvest in agricultural societies.

For modernists, such societies were devoid of historical meaning in addition to being poor and readily exploited. The amorphous realm of the spirit was for losers, the Chinese May 4th generation decided. Railroads, shipyards and electrification offered salvation.

Today, as Chinese roads, telecoms and entrepreneurs transform Bangladesh and its peers in the developing world, you could say that the argument has been won by the Chinese. Chinese infrastructure creates a new sort of blank generic urban template, one seen first in Shenzhen, then in Kunming and lately in Vientiane, Dhaka or Indonesian mining towns.

The sleepy backwaters of Southeast Asia have seen previous waves of Chinese pollinators. Low Lan Pak, a tin miner from Guangdong, established a revolutionary state in Indonesia in the 18th century. Li Mi, a Kuomintang general, set up an independent republic in what is now northern Myanmar after World War II.

New sorts of communities might walk on the new roads and make calls on the new telecom networks and find work in the new factories that have been built with Chinese technology and funded by Chinese money across Southeast Asia. One Bangladeshi investor told me that his government prefers direct investment to aid — aid organizations are incentivized to portray Bangladesh as eternally poor, while Huawei and Chinese investors play up the country’s development prospects and bright future. In the latter, Bangladeshis tend to agree.

“Is China a place, or is it a recipe for social structure that can be implemented generically anywhere?”

The majority of human beings alive today live in a world of not enough: not enough food; not enough security; not enough housing, education, health care; not enough rights for women; not enough potable water. They are desperate to get out of there, as China has. They might or might not like Chinese government policies or the transactional attitudes of Chinese entrepreneurs, but such concerns are usually of little importance to countries struggling to bootstrap their way out of poverty.

The first world tends to see the third as a rebuke and a threat. Most Southeast Asian countries have historically borne abuse in relationship to these American fears. Most American companies don’t tend to see Pakistan or Bangladesh or Sumatra as places they’d like invest money in. But opportunity beckons for Chinese companies seeking markets outside their nation’s borders and finding countries with rapidly growing populations and GDPs. Imagine a Huawei engineer in a rural Bangladeshi village, eating a bad lunch with the mayor, surrounded by rice paddies — he might remember the Hunan of his childhood.

Xi Jinping famously said that China doesn’t export revolution. But what else do you call train lines, 5G connectivity and scientific research centers appearing in places that previously had none of these things?

Across the vastness of a world that most first-worlders would not wish to visit, Chinese entrepreneurs are setting up electric vehicle and battery companies, installing broadband and building trains. The world that is looming into view on Huawei’s 2022 business report is one in which Asia is the center of the global economy and China sits at its core, the hub from which sophisticated and carbon-neutral technologies are distributed. Down the spokes the other way come soybeans, jute and nickel. Lenin’s term for this kind of political economy was imperialism.

If the Chinese economy is the set of processes that created and create China, then its exports today are China — technologies, knowledge, communication networks, forms of organization. But is China a place, or is it a recipe for social structure that can be implemented generically anywhere?

Huawei Station

Huawei’s connections to the Chinese Communist Party remain unclear, but there is certainly a case of elective affinities. Huawei’s descriptions of selfless, nameless engineers working to bring telecoms to the countryside of Bangladesh is reminiscent of Party propaganda and “socialist realist” art. As a young man, Ren Zhengfei, Huawei’s CEO, spent time in the Chongqing of Mao’s “third front,” where resources were redistributed to develop new urban centers; the logic of starting in rural areas and working your way to the center, using infrastructure to rappel your way up, is embedded within the Maoist ideas that he studied at the time. Today, it underpins Huawei’s business development throughout the Global South.

I stopped by the Huawei Analyst Summit in April to see if I could connect the company’s history to today. The Bildungsroman of Huawei’s corporate development includes battles against entrenched state-owned monopolies in the more developed parts of the country. The story goes that Huawei couldn’t make inroads in established markets against state-owned competitors, so got started in benighted rural areas where the original leaders had to brainstorm what to do if rats ate the cables or rainstorms swept power stations away; this story is mobilized today to explain their work overseas.

Perhaps at one point, Huawei could have been just another boring corporation selling plastic objects to consumers across the developed world, but that time ended definitively with Western sanctions in 2019, effectively banning the company from doing business in the U.S. The sanctions didn’t kill Huawei, obviously, and they may have made it stronger. They certainly made it weirder, more militant and more focused on the markets largely scorned by the Ericssons and Nokias of the world. Huawei retrenched to its core strength: providing rural and remote areas with access to connectivity across difficult terrain with the intention that these networks will fuel telehealth and digital education and rapidly scale the heights of development.

Huawei used to do this with dial-up modems in China, but now it is building 5G networks across the Global South. The Chinese government is supportive of these efforts; Huawei’s HQ has a subway station named for the company, and in 2022 the government offered the company massive subsidies.

“For many countries in the Global South, the model of development exemplified by Shenzhen seems plausible and attainable.”

For years, the notion of an ideological struggle between the U.S. and China was dismissed; China is capitalist, they said. Just look at the Louis Vuitton bags. This misses a central truth of the economy of the 21st century. The means of production now are internet servers, which are used for digital communication, for data farms and blockchain, for AI and telehealth. Capitalists control the means of production in the United States, but the state controls the means of production in China. In the U.S. and countries that implicitly accept its tech dominance, private businesspeople dictate the rules of the internet, often to the displeasure of elected politicians who accuse them of rigging elections, fueling inequality or colluding with communists. The difference with China, in which the state has maintained clear regulatory control over the internet since the early days, couldn’t be clearer.

The capitalist system pursues frontier technologies and profits, but companies like Huawei pursue scalability to the forgotten people of the world. For better or worse, it’s San Francisco or Shenzhen. For many countries in the Global South, the model of development exemplified by Shenzhen seems more plausible and attainable. Nobody thinks they can replicate Silicon Valley, but many seem to think they can replicate Chinese infrastructure-driven middle-class consumerism.

As Deng Xiaoping said, it doesn’t matter if it is a black cat or a white cat, just get a cat that catches mice. Today, leaders of Global South countries complain about the ideological components of American aid; they just want a cat that can catch their mice. Chinese investment is blank — no ideological strings attached. But this begs the question: If China builds the future of Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and Laos, then is their future Chinese?

Telecommunications and 5G is at the heart of this because connectivity can enable rapid upgrades in health and education via digital technology such as telehealth, whereby people in remote villages are able to consult with doctors and hospitals in more developed regions. For example, Huawei has retrofitted Thailand’s biggest and oldest hospital with 5G to communicate with villages in Thailand’s poor interior — the sort of places a new Chinese high-speed train line could potentially provide links with the outside world — offering Thai villagers without the ability to travel into town the opportunity to get medical treatments and consultations remotely.

The IMF has proposed that Asia’s developing belt “should prioritize reforms that boost innovation and digitalization while accelerating the green energy transition,” but there is little detail about who exactly ought to be doing all of that building and connecting. In many cases and places, it’s Chinese infrastructure and companies like Huawei that are enabling Thai villagers to live as they do in Guizhou.

Chinese Style Modernization?

The People’s Republic of China is “infinitely stronger than the Soviet Union ever was,” the U.S. ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, told Politico in April. This prowess “is based on the extraordinary strength of the Chinese economy — its science and technology research base, its innovative capacity and its ambitions in the Indo-Pacific to be the dominant power in the future.” This increasingly feels more like the official position of the U.S. government than a random comment.

Ten years ago, Xi Jinping proposed the notion of a “maritime Silk Road” to the Indonesian Parliament. Today, Indonesia is building an entirely new capital — Nusantara — for which China is providing “smart city” technologies. Indonesia has a complex history with ethnic Chinese merchants, who played an intermediary role between Indigenous people and Western colonists in the 19th century and have been seen as CCP proxies for the past half century or so. But the country is nevertheless moving decisively towards China’s pole, adopting Chinese developmental rhythms and using Chinese technology and infrastructure to unlock the door to the future. “The internet, roads, ports, logistics — most of these were built by Chinese companies,” observed a local scholar.

The months since the 20th Communist Party Congress have seen the introduction of what Chinese diplomats call “Chinese-style modernization,” a clunky slogan that can evoke the worst and most boring agitprop of the Soviet era. But the concept just means exporting Chinese bones to other social bodies around the world.

If every apartment decorated with IKEA furniture looks the same, prepare for every city in booming Asia to start looking like Shenzhen. If you like clean streets, bullet trains, public safety and fast Wi-Fi, this may not be a bad thing.

Chinese trade with Southeast Asia is roughly double that between China and the U.S., and Chinese technology infrastructure is spreading out from places like the “Huawei University” at Indonesia’s Bandung Institute of Technology, which plans to train 100,000 telecom engineers in the next five years. We’re about to see a generation of “barefoot doctors” throughout Southeast Asia traveling by moped across landscapes of underdevelopment connected to hubs of medical data built by Chinese companies with Chinese technology.

In 1955, the year of the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, the non-aligned world was almost entirely poor, cut off from the means of production in a world where nearly 50% of GDP globally was in the U.S. Today, the logic of that landmark conference is alive today in Chinese informal networks across the Global South, with the key difference that China can now offer these countries the possibility of building their own future without talking to anyone from the Global North.

Welcome to the Sinosphere, where the tides of Chinese development lap over its borders into the remote forests of tropical Asia, and beyond.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wars usually divide people, but Ukraine received overwhelming international sympathy after the full-scale Russian invasion. This was based on several factors. The unprovoked aggression made a moral stance obvious. Historically, too, Ukraine has never invaded or occupied any country. The many layers of the conflict garnered support on multiple fronts: sovereignty and independence; rule of law and human rights; nuclear and environmental threats; democracy against autocracy; and, in the end, the fact that it’s about an underdog stopping a superpower.

Ukraine’s foreign policy has traditionally focused narrowly on European and trans-Atlantic integration. But now that the country’s future depends on financial and military aid, Ukraine has—for the first time in its history—had to proactively engage with the rest of the world.

In June, more than 90 countries attended two days of talks in Switzerland at the behest of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky—the so-called High-level Summit for Peace for Ukraine. It was the latest in a series of global meetings organized by Kyiv to rally support. There have been presidential and parliamentary delegation visits (including to Saudi Arabia and Argentina) and invitations for foreign leaders to come to Kyiv (such as the Indonesian president and a delegation of African leaders).

At those meetings, Kyiv has raised a range of issues: sanctions against Russia; providing ammunition (including both new technologies and requests from the states that used to receive aid from the Soviet Union and then Russia); votes in the United Nations; the “Grain from Ukraine” initiative, designed to support shipments to countries in need from Ukrainian agricultural producers; and support on calls for Russia to be held accountable for war crimes.

For more than a year, my organization, the Public Interest Journalism Lab, has been inviting senior editors, intellectuals, and famous media personalities from more than 20 countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America to come to Ukraine. They have visited villages and grain terminals and talked to soldiers and war crime survivors, as well as Zelensky. Through this work, I have gained an insight into how thought leaders from many countries are thinking about this war; that feedback has, in turn, helped inform our evolving national strategy for winning hearts and minds around the world. After the initial full-scale invasion in February 2022, a majority of states supported the U.N. resolution calling for Russia to leave Ukrainian territory, with 141 votes in favor, 7 votes against, and 31 abstentions. We need to keep that broad base of support. Kyiv simply can’t afford for the war to become a globally divisive issue—even as Russia works to make it so.

Starting with the 2014 occupation of Crimea, the Kremlin has invested billions into anti-Ukrainian propaganda aimed at confusing Western audiences. Since its 2022 invasion, Moscow has refocused its tactics onto a divide-and-conquer strategy. With this in mind, Russian state media closed a few offices in the EU and the United States and opened more bureaus and outlets in the global south, including in South Africa, Kenya, and Brazil. To audiences in these countries, Russia portrays its war against Ukraine as a fight with the West, thereby challenging the idea that universal values and rules of law matter.

In combating this propaganda, Ukraine understands that there is no one message or one approach that will work across the world. In 2022, Zelenskyy introduced his “peace formula”—a 10-point plan intended to encourage countries to support the Ukrainian initiatives that they found most applicable to them, including nuclear safety, food security, and the return of prisoners and deported persons. This was intended to pave the way for those who wanted to stay away from direct military support or humanitarian initiatives by providing less contentious options.

At the Switzerland summit this June, the agenda focused on the least controversial initiatives— namely, nuclear energy and nuclear installations, global food security, the release of prisoners of war, and the return of the Ukrainian children deported to Russia—and each was in line with international law, including the U.N. Charter. Though China did not send a representative, and a few countries (such as Brazil, Mexico, and Indonesia) did not sign the final communique, the majority of the 90 countries in attendance did. The next meeting may be hosted by Saudi Arabia later this year.

Outreach has become especially urgent given the state of Ukrainian stockpiles. The EU does not have enough capacity to manufacture weapons for itself, and recent debates in the U.S. Congress have shown that Ukraine cannot be that dependent on American supplies. (And that supplies are not, in any case, enough for all the U.S. allies around the world.)

So far, Ukraine has mainly relied on its post-Soviet types of weapons, obtained from the countries that used to receive or buy them from the Soviet Union, Russia, or Ukraine itself. Appropriate ammunition is available in Argentina, Thailand, Brazil, and some African states. Since the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and a few recently added members) won’t provide any weapons to Ukraine, the primary aim is to ensure that they do not help Russia either, as North Korea does. And recently, Ukraine reached out to South Korea and Japan for more advanced ammunition.

After North Korean leader Kim Jong Un visited Russia in September 2023, Seoul has been looking not just at what Pyongyang gives to Moscow, but also what it may receive back. The Ukrainian prosecutor’s office has said the rocket that hit the civilian city of Kharkiv—the second-largest Ukrainian city, located 30 kilometers (19 miles) away from the Russian border— on Jan. 2 was of North Korean origin. And the use of at least 21 more North Korean-made ballistic missiles, including three in the city of Kyiv and in the Kyiv region, has now been identified by that office.

Now that Ukraine is focusing on developing its own weapons capabilities, the hope is that the advanced South Korean defense sector may assist with knowledge and technology, even if it does not supply armaments.

Against this backdrop is the potential precedent that Russia’s war in Ukraine sets for China regarding Taiwan. Ukraine is aware that China is probably one of the countries that benefits from the stalemate between Russia and Ukraine: It has opened up access to cheap Russian gas, led to the annihilation of Russian and Western arsenals, and distracted Washington from Pacific power struggles. There may be people in Washington who dislike the idea of Ukraine giving Beijing any greater role in international diplomacy, but Ukraine cannot afford to ignore it—Beijing supplying weapons to Russia is a realistic nightmare for Kyiv.

In answering a question from a Chinese writer at an interview that I had the chance to facilitate, Zelensky noted that Chinese President Xi Jinping is one of the few global leaders to whom Russian President Vladimir Putin will listen to in discussions around avoiding nuclear escalation.

In Africa, Ukraine has opened seven new embassies since 2023, adding to the 10 already operating on the continent. Meanwhile, the Russian diplomatic service inherited a Soviet diplomatic infrastructure that included hundreds of embassies. Though Ukraine did maintain strong trade relations with North Africa following its independence, mainly due to geographic proximity to the Mediterranean Sea, the post-Soviet republics that regained independence amid catastrophic economic crises couldn’t dream of having comparable reach or even a presence anywhere from Tokyo to Delhi, or Nairobi to Kampala.

But though Ukraine will never be able to compete with Russia diplomatically, there is one way in which Ukraine has reached much of the world: food.

Until Russia blockaded Ukrainian ports in February 2022, thereby disrupting a major route for moving agricultural products, Ukrainians themselves didn’t fully comprehend how dependent so much of the world was on their exports. The World Economic Forum estimates that before 2022, Ukraine provided 10 percent of the world’s grains. The country also grows 15 percent of the world’s corn and 13 percent of its barley, alongside sunflower and other staple crops. In 2020, Ukraine was, for instance, the top supplier of wheat and rye to Indonesia; these are the base ingredients for instant noodles, a staple snack for the world’s fourth most populous country.

In July 2022, the United Nations and Turkey brokered the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which eased the Russian blockade. The agreement allowed for a limited number of cargo ships to leave Odesa along a tightly controlled maritime corridor, subject to Russian inspections. Still, the agreement managed to let out more than 1,000 vessels to send at least 32.8 million metric tons of agriculture products.

It was at this point that Ukrainian leadership understood that there was something Ukraine could not just ask for, but offer. Ukraine also partially succeeded in explaining that food prices had climbed not because of the war in Ukraine, but because of the Russian blockade of the Ukrainian ports, and that—despite fighting for its life—the country was doing its best to continue to feed the world.

The Black Sea agreement was unilaterally broken by Moscow in the summer of 2023. Since then, Russian artillery has been constantly targeting Ukrainian agriculture infrastructure and ports. The Ukrainian message to agricultural consumers is that the liberation of the Black Sea and the Ukrainian south is the only way to return to cheaper commodities.

Appealing to concepts of universal justice and human rights is another important avenue for Ukraine to pursue internationally. As Olena Zelenska, the first lady of Ukraine, said at an event that I organized in response to a question from a Nigerian editor, “when we understand that the international system doesn’t work, we must talk not just about ourselves, but about all the other war crimes, humanitarian crises, and tragedies of people around the world.”

The Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine has registered more than 130,000 alleged war crimes committed by Russia. To prosecute senior Russian leaders, the country seeks global support to create an ad hoc Special International Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression, which Ukrainian attorneys call “the mother of all crimes.” War crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide are currently being investigated by Ukrainian law enforcement, as well as by the International Criminal Court (ICC). National prosecutors, overwhelmed by the scale of atrocities, are willing to pass even the most notorious and memorable cases to be investigated abroad under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

National prosecutors, overwhelmed by the scale of atrocities, are willing to pass even the most notorious and memorable cases to be investigated abroad under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

One example comes from an initiative that I am involved with devoted to war crime documentation, the Reckoning Project. A team from this organization, which includes Ukrainian and international members—including journalists and lawyers of Syrian origin—submitted a criminal complaint to the Argentinian Federal Judiciary in April to investigate torture against a Ukrainian citizen committed during the Russian occupation of Ukraine. (The Argentinian Constitution allows its courts, based on universal jurisdiction, to try international crimes, including crimes against humanity and war crimes, irrespective of where they took place.)

Pragmatists warn that striving to promote human rights issues globally in such ways is naive. But my experience is that it feels the opposite when you talk to those who were oppressed in Iran, Nicaragua, or Syria. Talking to the survivors of war crimes left a powerful impression on correspondents from Asia, Latin America, and Africa who came to Ukraine with various interests and priorities. These conversations were particularly powerful because the journalists were able to relate by sharing stories about their own societies with the Ukrainian survivors.

A Nicaraguan reporter compared the suffering of a schoolteacher from the Kherson region who was held in Russian captivity to the torture that prisoners are subjected to in his native country. A Uruguayan editor wanted to learn how the proper documentation of human rights abuses could enable the delivery of justice in the case of still-ongoing trials of the Uruguayan junta for crimes committed in the 1970s.

With a human rights nongovernmental organization from South Korea, we discussed the possibility of working together on how to broaden the definition of sexual and gender-related violence in international laws, comparing offenses in Ukraine and North Korea. In Abuja, after a screening of a clip from a Reckoning Project film about the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia, a Nigerian activist asked me to support her campaign to recover the girls stolen by Boko Haram who still remain in captivity.

During an interview with Asian journalists, Ukrainian Prosecutor General Andrii Kostin himself raised the repeated accusation that Ukraine receives disproportionally more global attention than other global tragedies. “My way to respond is to say that we have the political ability to use any existing global platform which the government can access to investigate, and we are ready to share it,” he said.

Where else, if not here, can justice be served? Given the scale of the properly documented evidence accumulated by local and international media, the presence of investigators, and a relatively functional national law enforcement, what would be the meaning of those conventions if they cannot succeed in prosecutions in this case?

The warrant issued to Putin by the ICC for the deportation of the Ukrainian children in March 2023 was, if not an immediate game-changer, still likely the fastest-ever decision in ICC history. Ukraine wants to prove that even if the international treaties are impotent in preventing atrocities, there should be a more robust global response to prosecute perpetrators, so they do not enjoy full immunity—like the Russian army’s, which enabled it to master its gruesome practices in Chechnya, Georgia, and then in Syria before entering Bucha and Mariupol.

Still, the importance of the so-called rules-based order should not be confused with a framing of the war as a fight between democracy and dictatorship, which risks alienating much of the world.

Tensions must be navigated carefully. For Ukrainian officials, meeting their Taiwanese or Hong Kong counterparts would be impossible—they cannot afford to alienate Beijing. In such cases, Ukrainian civil society, and sometimes the opposition, takes the lead. In the summer of 2024, the major Ukrainian Human Rights Documentary Film Festival partnered with the Taiwan International Documentary Festival. Likewise, Ukrainian human rights defenders stay away from the officials in semi-authoritarian countries, leaving those relations to authorities.

In January 2023, Cambodia—which experienced the Khmer Rouge genocide and is one of the world’s most mined countries—offered to train professionals in Ukraine in humanitarian demining. Ukraine also maintains strong trade relations with Algeria.

Some of these interactions may look symbolic, but they challenge Russian attempts to claim that all not-fully-democratic countries back Moscow by default.

Ukrainians know how offensive it feels to be denied their agency in a situation in which the whole population stood up to invasion by its neighbor and former imperial ruler. But by now, Kyiv is learning not to push nations to choose a side, and not to treat votes in the U.N. as the only criteria for engagement. Members of the Non-Aligned Movement cherish that tradition, which has no connection to their take on a far-away war. It took time for Ukrainians to understand that some continents have not just anti-American, but also anti-European sentiments because of the horrors of colonial history.

After the Israel-Hamas war broke out in Gaza, a group of experts that worked on reaching out to the so-called global south—a term everybody dislikes but has not yet been replaced with a better alternative—gathered in Kyiv to discuss how Ukraine could navigate this newly polarized environment. Support for Israel outside of the United States and Western Europe may be seen as an attempt to please Washington, but Ukraine has its own historic relations with Israel. The Holocaust was partly committed on Ukrainian soil; many Israelis are immigrants from the territory of Ukraine. Hamas is supported by Iran, which also openly backs Moscow. At the same time, there will be other Ukrainians whose sympathy goes to the Palestinian people, whose land—like Ukraine—is occupied.

The ensuing discussion made it more obvious that invoking parallels to every tragedy may be inappropriate and counterproductive for Ukraine. Nonetheless, Ukrainians intuitively feel that their fate is bound to the rest of the globe and a common struggle for a better world. Global solidarity isn’t something that can be demanded; it must instead be inspired.

In the end, Ukraine does not expect foreigners to fight—it is Ukrainians who are paying the highest prices, with their own lives.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a huge potential for the members of the extended Brics group to cooperate in ensuring energy security in their countries, South African Minister of Energy and Electricity Kgosientso Ramokgopa said at the 9th Brics Energy Ministerial Meeting in Moscow.

"We believe that this Brics group of like-minded country members has a huge potential and working together will strengthen this resolve through cooperation on energy security, and also provide an opportunity to join efforts to annihilate the challenges diagnosed during the Brics 2023 Summit held in South Africa, such as addressing the lack or absence of an integrated energy policy framework," Ramokgopa said.

The minister said this meeting came at "a critical phase where our countries are grappling with the challenge of balancing developmental goals with energy transition pathways".

"We must ensure that these transitions safeguard energy sovereignty and security, promote sustainable economic development, facilitate universal access and respond effectively to environmental imperatives, all the while ensuring no one is left behind," he said.

Commenting on the meeting being the first that included the new members of the Brics grouping that joined at the beginning of the year, Ramokgopa said the expansion of the Brics membership was a clear affirmation of the group's growing significance and influence in the global energy agenda.

Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates were admitted as new members to the original Brics grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa in January.

Business Standard

Source: www.business-standard.com

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Morally, nobody’s against it’: Brazil’s radical plan to tax global super-rich to tackle climate crisis

A 2% levy would affect about 100 billionaire families, says the country’s climate chief, but the $250bn raised could be transformative

Proposals to slap a wealth tax on the world’s super-rich could yield $250bn (£200bn) a year to tackle the climate crisis and address poverty and inequality, but would affect only a small number of billionaire families, Brazil’s climate chief has said.

Ministers from the G20 group of the world’s biggest developed and emerging economies are meeting in Rio de Janeiro this weekend, where Brazil’s proposal for a 2% wealth tax on those with assets worth more than $1bn is near the top of the agenda.

No government was speaking out against the tax, said Ana Toni, who is national secretary for climate change in the government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

“Our feeling is that, morally, nobody’s against,” she told the Observer in an interview. “But the level of support from some countries is bigger than others.”

However, the lack of overt opposition does not mean the tax proposal is likely to be approved. Many governments are privately sceptical but unwilling to publicly criticise a plan that would shave a tiny amount from the rapidly accumulating wealth of the planet’s richest few, and raise money to address the pressing global climate emergency.

Janet Yellen, the US Treasury secretary, told journalists in Rio that the US “did not see the need” for a global initiative.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#environmentalism#economy#climate change#environmental justice#brazilian politics#foreign policy#international politics#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sônia Guajajara, An Indigenous Trailblazer

Born on March 6, 1974, in the heart of the Amazon rainforest on Araribóia Indigenous Land, Sônia Guajajara embodies resilience, courage, and advocacy for Indigenous rights. She is a member of the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) and has made history as the first Indigenous person to run for a federal executive position in Brazil during the 2018 General election.

As the leader of the Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil (APIB) (translated as the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, it is a national reference and unifying force within the Indigenous movement in Brazil), Sônia Guajajara represents around 300 Indigenous ethnic groups in Brazil. She fiercely opposes deforestation policies and advocates urgent environmental action, even amidst the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Her work at COP26 led to the creation of a $1.7 billion fund for Indigenous peoples and local communities, recognizing their essential role in protecting land and forests from degradation.