#bisexual oppression

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It’s so crazy to me how even in shows that are supposed to be progressive and queer focused, bisexuality is so misunderstood and misrepresented. I’ve been watching Batwoman with my boyfriend, and the way they handle bisexuality in the show is quite frankly, a fucking travesty.

the show centers on a sapphic couple who have been broken up for a few years, and one of the women (a bisexual) is now in a relationship with a man. Her whole identity is portrayed as if she’s betrayed her lesbian ex girlfriend by being with a man (despite the fact that they’ve been broken up for years) and is seen as an obstacle that needs to be overcome.

The show also passingly conflates bisexuality with polyamory as if this isn’t one of the biggest negative stereotypes that affects the bisexual community.

this sort of treatment happens a considerable amount with queer focused shows and movies, another one of which is can think of is Orange is the Black, in which in the main character, Piper, is bisexual. Pipers bisexuality is a huge part of the storyline, but she is only outrightly labeled as bisexual a handful of times throughout the entire show, and when she IS labeled bisexual it’s accompanied with the description of shallow.

Bisexual representation is abysmally handled in queer media, and I need writers to start actually researching what it means to have a bisexual character, and not simply fall into the dozens of negative stereotypes that are out there about us.

#bisexual#bisexuality#queer#lgbtqia#sapphic#queer media#queer tv#queerness#bisexual representation#bisexual erasure#bisexual oppression#bisexual stereotypes#ro says stuff

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

it always makes me so sad to see other people, especially other queer folk, shame a label for being “too specific”

A label is supposed to IDENTIFY, if it doesn’t properly do the job than that’s when it becomes “what’s the point?”

Plenty of people go unlabeled because they CANT find the right label

Plenty of people use a bunch of different labels because they can’t find the right label.

“why say your pansexual, bisexual works just fine” no it doesn’t if it doesn't properly describe the experience someone is having and wants to convey (being attracted to all genders without a preference)

“Why use omnisexual, pansexual works just fine” no it doesn’t if it doesn't properly describe the experience someone is having and wants to convey (being attracted to multiple genders with a preference)

“Why use gynesexual, pansexual works just fine” no it doesn’t if it doesn't properly describe the experience someone is having and wants to convey (being attracted to femininity regardless of gender)

All of what I listed goth under the umbrella term bisexual, which fit under the umbrella term queer which fits under the umbrella of “relationships with other humans”. Humans get more specific because they want to be able to describe their experience. Humans desire connection.

It may seem cringe to but these are people identities, these are peoples lives. People can go their whole lives feeling like their ignoring themselves and their identity because of a label they picked whether it be hyper specific or super vague. These labels are for no one but themselves and a means to convey identity to build a bridge to others. Two things can be true at once.

Not to mention the amount of neurodivergent and autistic people like myself out there feeling separated from humanity altogether and may pick a trans identity less than conventional.

Your experience is your own and not everyone’s like you. Be educated and try to understand where someone is coming from. And if you can’t bother, then don’t ruins someone’s day (and maybe even life) with your comments.

Its already a terrible life just learn to be tolerant of how people cope.

#tolerance#empathy#compassion#oppression#sociology#beliefs#stardust writing#queer#lgbtq community#queer community#lgbtqia#lgbtq#queer love#queer pride#queer artist#happy pride 🌈#pride month#trans pride#pride 2025#lgbtqiia+#2slgbtqia+#transgender#nonbinary#pansexual#bisexual#tags#Notice how I said other humans?#I don’t mean animals#And I don’t mean adults with children#if that wasn’t obvious

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

the way some of you clearly think bisexuals don't experience actual attraction and feelings for people, but rather decide ahead of time if they want a man or a woman this time and then just go and pick whoever comes into their line of sight next is so obvious and definitely makes me think you all don't need to speak on things you don't know about

#if you aren't bi I realllly don't want to hear you talking about us or our experiences#because it's just gonna be stereotypes or bitterness from a bi woman who upset you#I know damn well I would not get away with saying some of the shit that you guys do if it was about lesbians instead of bi women#and I don't want to#I shouldn't be able to get away with that!#but some of you absolutely are completely prejudiced and I feel like no one takes that seriously#if you use the term 'bihet' this is about you btw#gonna call out 'bi lesbians' because 'that's not how sexuality works!! you're one or the other!!' but then turn around and say it's okay as#long as it's to insult us??#doesn't add up.#so if you aren't bi go ahead and don't bother talking about bi people#you don't understand how bisexuality works#you don't understand how relationships in general work#('you could just get over your attraction to women and eventually find a man you'd be happy with so you aren't actually oppressed!')#(like okay. you could just never act on your attraction and not tell anyone. just like you want us to do. oh wait? sound familiar? yeah.)#'you could lie about your sexuality and force yourself to only date men' is not an argument you want to be making and I can't believe you#haven't pieced that together. because that exact same thing can be said about anyone

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

holly-anne hull (and matt blaker), shot from sidestage at phantom london by melanie gowie (2023)

#phantom london#phantom of the opera#phantom west end#holly-anne hull#matt blaker#raoulstine#truly such a gift to me that the paratext around phantom means i get to feel like god's bravest and most oppressed warrior about R/C <3#me [very brave and noble and sui generis]: I Like When There Is A Princess And A Knight And Bad Stuff Happens To Them!#i love butchfemme i love doomed chivalry i actually even love mutually dumb bisexuality like it is 2013 on here still

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bisexual Feminist Blinkies! 🩷

All blinkies made by me, but I found all the formats on blinkie.cafe!

#feminist#bisexual feminist#feminists 4 trans rights#feminism#fuck the patriarchy#female oppression#girl power#women#women deserve better#women deserve respect#women power#we should all be feminists#transgender#trans rights#trans feminism#bisexual women#bisexuality#bi#bi bi bi#bi sapphic#bisexual sapphic#sapphic#sapphicism#sapphic pride#bi pride#bisexual pride#blinkies#web graphics

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

essentially what's frustrating abt being a bi woman on here is that if you bring up the fact that our statistics reflect the markers of being an oppressed class, despite a large percentage of us being partnered with the other sex, it's treated as if you're arguing that heterophobia exists

#and it's like. why don't you get that oppression exists on a material level.#how many times are you gonna bring up material reality to some transactivist and then fail to apply the same logic to bisexuality#do passing trans men have male privilege or do they still experience sex-based oppression? answer quickly

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sick of It: Medicine, Margins, & the Struggle to Be Understood

Another zine?

Well, yes! Another zine! For me, they’ve been a constant source of fascination since my middle school emo days, when I first read The Perks of Being a Wallflower. It felt like finding a secret language — a way to express myself outside the mainstream. Back then (and still now), I was obsessed with The Rocky Horror Picture Show and alternative music, and discovering that zines could blend both worlds was mind-blowing. Zines make complex, emotional, and nuanced topics easier to digest — especially in spaces like medicine, where the language can feel cold and clinical, and the stakes are deeply personal.

So why this topic, and why now? Well, the western world doesn’t usually think of medicine as a space for ambiguity, emotion, or cultural critique—but I believe we should. As someone going into the medical field, I’ve been grappling with how often care gets reduced to checklists, diagnoses, and prescriptions — especially when it comes to mental health. This topic is personal, too: as a queer person, I’ve seen how systems like the DSM have historically pathologized queerness and continue to enforce narrow ideas of what’s “normal.” Why are we so quick to label everyday human struggles as disorders? How did we end up treating things like loneliness, grief, or shyness with medication? And what happens when we bring in philosophy, queer theory, and other humanities to rethink what “health” even means?

By unpacking the history of the DSM, the medicalization of life, and our cultural discomfort with uncertainty, I aim to describe a future where medicine is less about control and more about care—where doctors are allowed to sit with the unknown, and where being human doesn’t have to mean being sick. This project is an homage to the queer and alternative voices that came before me—but it’s also for everyone. Everyone should have the right to timely, effective, and personal medical care.

Quick Disclaimer

Mental illnesses are real, valid, and can be incredibly debilitating—trust me, I know. This zine is in no way intended to delegitimize the reality of mental health struggles or the life-changing benefits that therapy, medication, and diagnosis can offer. For many people, these tools are essential, even lifesaving. This work is not a rejection of medicine, but a critique of how modern (and not-so-distant past) medical systems have sometimes failed to account for nuance, culture, and the full complexity of being human. My hope is to open up space for conversation, reflection, and alternative ways of thinking about care — not to close the door on any particular path to healing.

The History of the DSM

The American Psychiatric Association's DSM has been thought to be the science-informed, authoritative guide to diagnosing mental illness in the United States (and only in the United States) for decades. Yet its history is about more than simply an expanding knowledge base concerning mental health — it is about deeply ingrained cultural concerns about normativity, identity, and control. [x] From a queer theoretical perspective, the DSM is not merely a clinical instrument, but is equally an apparatus of regulation marking the limits of normative subjectivity. Presented for the first time in 1952, the DSM has been revised six times, ever more pathologizing increasingly wide swaths of human behavior. With the DSM-III (1980), widely regarded as a revolution in psychiatry, there was an effort made to standardize diagnoses by moving toward its biomedical and symptom-focused model. This shift was couched as scientific advancement, but it reaffrimed the authority of psychiatry at the moment it was losing its legitimacy in culture [DSM: A history of psychiatry’s Bible].

This move may be understood as part of a larger biopolitics — a type of power which governs and specifies life through medicalizing so-called deviancy. Historically, queerness has itself been medicalized within the DSM: homosexuality was categorized as a disorder until 1973, and gender nonconformity is still couched in medical discourse through the diagnoses of "gender dysphoria.” [x] Despite the rewriting of language, the power relations remain. The DSM's categorizations do not merely categorize mental states — they create and impose norms about what sorts of lives are understandable, healthy, and valuable.

The Evolution of the DSM

The DSM's trajectory from its initial editions to the current DSM-5-TR illustrates a trend toward expanding diagnostic categories. This expansion has been both appreciated for increasing recognition of mental health issues and critiqued for potentially over-pathologizing normal variations in human behavior.

This broadening of diagnoses has significant implications. On one hand, it can lead to greater access to care for individuals experiencing distress. On the other, it risks labeling individuals unnecessarily, leading to stigma and the potential for overmedication. The DSM's influence extends beyond clinical settings, affecting insurance coverage, educational accommodations, and legal decisions, ultimately embedding its classifications deeply into societal structures.

Oddly enough, where there is queer theory, there is Marxist theory. The way the DSM deals with capitalist institutions — especially the pharmaceutical industry — has been the central target of such criticism (go figure!). The proliferation of diagnostic categories strongly correlates with the commercial development of many new drugs, leaving one to wonder about the motives of some of the inclusions in the manual. Critics say such a relationship can foster the medicalization of normality, in which natural experiences are recast as disorders that must be addressed with drugs.

I think Peter Conrad puts it very well: “The impact of medicine and medical concepts has expanded enormously in the past fifty years... the jurisdiction of medicine has grown to include new problems that previously were not deemed to fall within the medical sphere.” [The Medicalization of Society...] The money that pharmaceutical companies make off these substances is genuinely disgusting. Discovering new disorders open markets for medications, and the sanction of the DSM confers legitimacy on these conditions. It’s this dynamic that has led to favoring medication over other types of therapy, such as psychotherapy or community-based interventions, which may be more beneficial for some people (but don't make the big companies as much money).

The DSM has come under fire for conflicts of interest in the creation of diagnostic criteria and selection of disorders for inclusion. Research from Cosgrove et al. informs that a majority of members of DSM panels had money links to drug firms. [x] This is cause for serious concern about the role of profit motives in determining what gets designated as a mental illness—especially given that new diagnoses typically spur demand for new medications.

Think about the medicalization of the everyday: shyness as social anxiety disorder, bereavement as major depressive disorder, moodiness in adolescents as intermittent explosive disorder—and all these changes result in a new wave of prescriptions for SSRIs and other psychotropics. The financial incentives to pathologize behavior not only shape the approaches to treatment but also the definitions of illness itself.

This expanding scope of medical prerogative has redefined the limits of what was once thought to be “treatable," reinforcing the notion that all types of distress or deviation must be remedied through therapeutic channels. As was mentioned earlier, the DSM defined homosexuality as a mental illness—what gets pathologized usually mirrors not scientific agreement but social bias. Although that designation was rescinded more than 50 years ago, the taint of pathologization often still clings to non-normative identity in more insidious forms.

The DSM becomes a site in which capitalist and clinical interests intersect, producing “treatable” subjects and driving the commercialization of mental illness. According to Horwitz, diagnoses have not only evolved to serve as tools for treatment but also as tools for the construction of identity, access to treatment, and institutionalization [DSM: A history of psychiatry’s Bible]. For a few, diagnosis offers language for suffering and a path to support. However, queer theorists warn against the comfortable allure of legibility in a system that has historically pathologized and erased non-normative being. Thus, while diagnosis might provide solace in the form of legitimation, communality, and access, it also exacts a frame that threatens to reduce multifaceted lives to lists. For queer and raced communities, this might be a lifeline and a straitjacket—a means of being noticed but only within a frame that has exerted efforts to eliminate them.

Epistemology

So, here in a world in which queer lives tend to get misunderstood or overlooked, diagnosis of mental illness can provide a kind of epistemic acknowledgment. Epi-what-now?! In simple terms, epistemology is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature, origin, boundaries, and value of knowledge. It deals with the core questions: What does it mean to understand something? How do we separate belief and truth? In medical and psychiatric fields, epistemology assists us in analyzing how a certain type of knowledge—such as diagnostic criteria or clinician expertise—is made, validated, and used, sometimes laying bare the cultural, political, and institutional power structures that determine what we think of as "capital ‘T’ truth" about the human body and mind. Being diagnosed can authenticate that a real process is occurring—when the cause of distress is structural in nature, e.g., homophobia, racism, family rejection. In cyberspace in particular, communities tend to congregate in respect to diagnosis—ADHD, BPD, autism, CPTSD. For queer people in some cases, these conditions may grant more cultural visibility than queerness does on its own, providing a legible cultural model through which to explain their difference. In his journal, Michel Foucault’s asserts that "medical language does not merely describe reality—it aids in the construction of reality."

Diagnoses do not merely name disorder; instead, they aid in the formation of the way individuals perceive themselves and are perceived by others. Neurodivergent conceptualizations appeal to many queer individuals because they upend normative timelines, ways of expressing themselves, and modes of relationship. In this sense, requesting a diagnosis isn't always a matter of fixing the self but rather a matter of resisting assimilation into cishetero-normative and neurotypical forms. It is a survival and articulation tactic in a hostile world. This holds particularly for the diagnosis of gender dysphoria, which it’s possible to reclaim as a means of negotiating healthcare systems while resisting their normative enforcement.

At the same time, we need to make space for paradox. Medical gaslighting—where women, queer individuals, and people of color have their symptoms disregarded—is an ongoing and damaging practice that exists. [x] But so does the pathologization of marginalized identity. A queer patient may be invalidated when complaining about pain but also rapidly diagnosed with a psychiatric condition that locates their distress within personal pathology instead of as a reaction to structural violence.

Embracing Uncertainty

In The Epistemology of the Closet, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick critiques the rigid binaries that dominate Western thought—healthy or sick, treatable or untreatable, known or unknown—and reveals how those dichotomies oversimplify the richness of human experience. Her metaphor of “the closet” is not limited to sexuality; it serves as an epistemological structure that organizes what is speakable and unspeakable, what is acknowledged and what is disavowed. Sedgwick observes that “the relations of the closet—the relations of the known and the unknown, the explicit and the inexplicit… have the potential for being peculiarly revealing, even paradigmatic, for the understanding of other kinds of epistemological structures.” This insight resonates deeply within psychiatry, a field where uncertainty is often met not with curiosity but with suspicion—and all too often, with diagnosis [The Epistemology of the Closet]. The DSM's relentless push to label and classify emotional distress speaks volumes about a larger cultural tendency to sidestep the discomfort of the unknown. Increasingly, medical practitioners—especially physicians—are expected to respond not only to physical illness but also to deeper, less tangible forms of suffering: loneliness, grief, disconnection, and the weight of systemic harm. When care becomes a process of regulation—when every ache must be labeled, coded, and treated—we risk erasing the profoundly human potential that lies within what medicine can’t yet name.

This call for a more humane approach echoes in modern critiques of clinical practice. Hilty et al. argues for a reimagining of medical education—one grounded in interdisciplinary learning and human-focused care. [x] Similarly, Amsterlaw et al. point out a troubling gap between reality and expectation: while patients often crave certainty and doctors strive to deliver it, certainty rarely captures the messy, fluid truth of human health. [x] That mismatch—between lived experience and rigid diagnostic structures—can lead to overmedication, fractured trust, and a sense of alienation that no prescription can fix.

So, in short, the DSM is not a neutral document. It is shaped by political, cultural, and economic forces—which, in turn, shapes us. So I offer this: what if naming is not always liberating? What if diagnosis sometimes deepens the exclusions it aims to heal?

Moving Toward a New Philosophy of Care

So, what can be done? It is not just practice but also philosophy that must change in medicine. We need systems that reward relationships, not solely diagnosis: longer visits, integrative teams, community-based care. Physicians should be taught to hear stories, not just checklists. The humanities in general, and queer theory in particular, supply critical tools: We challenge the binaries, derive worth from the inarticulate, and practice compassion for what can’t be cured.

What if practitioners were trained to say, “I don’t know — but I’m here with you”? What if healing was about more than just an absence of symptoms? This isn’t naive—it’s a demand for structural and cultural change. The medicine of the future is one that is permeated with slowness, multiplicity and uncertainty; not because these are failings, but because they are constitutive of caring itself.

Rethinking caring is not just a matter of philosophy—it is a matter of action. Are the reform efforts centered on access? Without the line to the doctor, the person who is listening and the shoulder to lean on, the vision stays silhouetted. Broad-case providers — PAs, NPs, DOs, MDs — are lifelines in low-access areas. But they are frequently overwhelmed, underpaid and asked to not only heal illness, but also grief, poverty and alienation. This is where reform needs to start. Increase access through mobile clinics, multilingual care and community-centered services. Invest in primary care as the foundation of health — not just as a gateway to specialists, but as a milieu for relational healing as well. Include humanities and critical theory in medical education. Dismantle silos between fields. Fund time, not efficiency. And restructure our pharmaceutical systems to prioritize ethics over profit (I’m so done with these drug ads!).

Finally, it’s not only a matter of fixing what’s broken. It’s about redefining what we mean by health—and who gets to define it.

#always question authority#protect trans kids#free the oppressed classes#do not let the oppressors win#build communities where no one is disposable#practice mutual aide not charity#disrupt systems that thrive on silence#your anger is valid#your care is revolutionary#another world is not only possible#it is necessary#zine#essay#long post#queerzine#medicine#modern medicine#overmedication#transgender#gay#ftm#mtf#bi#bisexual#queer#lgbtq#pan#this was my final#this was for school#i hope i get a good grade on this

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sat in a restaurant yesterday with a lesbian listening to their recent experience with a straight poly couple. It was rape, but neither of us used that word. I've also met the bi chick who lured them into the situation - she boasted to me about how much her boyfriend loves sleeping with a lesbian. How he loves violent sex, how she loves taking it and making lesbians watch.

Now, I hate men. But honestly? I hate bisexual chicks who act as unicorn bait more.

#This is why it's 100% valid to exclude bisexuals from your dating pool#especially as a lesbian#we face too much violence to takes risks with a demographic that spends a majority of its time being complicit in our assault/oppression#and don't pull the Not All Bisexuals claim because it's ENOUGH of you#if you understand KAM but don't understand this then you don't actually understand KAM

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bisexual Woman flag <3

I chose pink for- not femininity as all women are beautiful whether they’re masculine or feminine- but for femaleness. Purple for sapphicness and womanhood. And green since it’s an international women’s day colour. I am so proud of this flag :)

#custom flags#bi flag#bi woman#bisexuality#bi#bi bi bi#bisexualism#bi pride#bi positivity#bisexual pride#bisexual positivity#bi women#bisexual women#women#feminist#feminism#fuck the patriarchy#patriarchy#male privilege#female oppression#bi women <3

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's kinda baffling the gymanstics transandrophobes perform in order to insist transmascs aren't oppressed and only experience Transphobia Lite and are in fact oppressors of trans women

#same vibe as people that rank which sexualities are Most Oppressed#and say bisexuals oppress gays and lesbians

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the rampant biphobia on tiktok needs 2 be addressed

#like ever since i got on lesbiantok i see a lot of vitriol towards bisexual women from lesbians n its making me uncomfortable i wont lie#like its getting weird…..u dont need to be doing all that :/#bisexuals do not oppress lesbians they do not have privilege over us like Please bro#im so tired of that damn clock app dude#as a lesbian we need to stop fighting n start working out our differences n maybe kiss abt it later idk!!!!!#.post

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

We don't necessarily want you all to pay or be sorry, we want you to stop supporting systems put in place to oppress people who don't look like you.

By all means, be proud to be white, Christian, straight, cis gender, etc ...

But not everyone wants that for themselves and we all should have the right to choose whatever is best for us, even if it's not the path you would have chosen for yourself.

#gender fluid#mixed race#mexican and white#Mexican#indigenous#indigenous lives matter#black lives matter#black and brown#poc#people of color#people of the world#systems of oppression#oppression#free all oppressed peoples#donald j#djt#donald trump#fuck trump#trust no priest#anti christian#christian mythology#christian faith#athiesm#spirituality#gay#bisexual#lesbian#transgender#support#acab1312

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Are we going to sit around and wait for every group to point out their own invisibility to us?"

The Natural Next Step: Including Transgender in Our Movement by Naomi Tucker (Anything That Moves iss. 4)

#invisibility#erasure#queer#oppression#naomi tucker#the natural next step: including transgender in our movement#the natural next step#anything that moves: the magazine for the working bisexual#anything that moves

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Rikki Schlott

Published: July 20, 2023

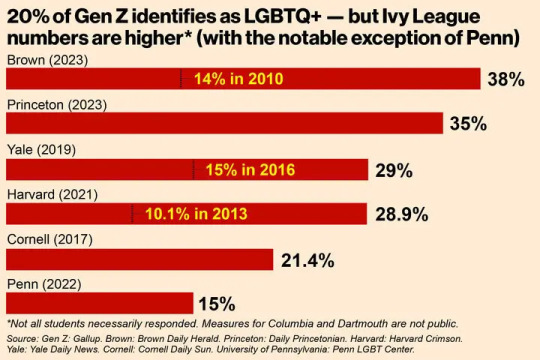

While just 7% of Americans are LGBTQ+, students at Ivy League universities are identifying as non-straight at rates as much as five times the general public.

Brown University made headlines after a student poll revealed a whopping 38% of their student body is not straight.

“Honestly I’m not surprised by that statistic,” an anonymous senior at Brown University told The Post. “At Brown, there’s no social pressure to fit into a box or hide your identity.”

Other Ivies aren’t far behind. In fact, more than a third of students at Princeton and more than a quarter at Yale and Harvard identify as LGBTQ+, as per recent polling — and campus sources chalk it up, in part, to politics and a desire to join an “oppressed” group.”

According to the Census Bureau, 20% of Gen Z is LGBTQ+, far more than older cohorts. But Ivy League students far outstrip their generation as a whole.

According to Abigail Anthony, who graduated from Princeton University with a degree in politics this year, a progressive and identity-consumed culture on elite campuses could be contributing.

[ Ivy League schools have much larger proportions of LGBTQ+ students than the general population. ]

“Since sexual orientation identity is largely non-falsifiable, many people will claim LGBTQ status to join the ‘oppressed’ group,” she told The Post.

According to a Princeton student newspaper survey, 35% of the 2023 graduating class identified as something other than straight.

“It could be that students at elite schools are more inclined to be obsessed with social acceptance and professional advancement, and … profess an LGBTQ identity to indicate their political beliefs on a campus that leans left,” she added.

At schools for which historical data is available, the proportion of students who are not straight is skyrocketing. Brown jumped from 14% in 2010 up to 38% this year.

Some 29% of Yale’s class of 2023 identified as something other than heterosexual when they were surveyed as freshmen in 2019. That’s up from just 15% of the class of 2020 when they were asked by the school paper in 2016.

And the proportion of LGBTQ+ students at Harvard tripled over the last decade, from 10% of incoming freshmen in 2013 to 29% in 2021.

The most recent data from Cornell comes from 2017, when 21.4% of freshmen were LGBTQ+. The University of Pennsylvania is an outlier, at just 15% as of 2022.

Ben Appel, 40, finished his undergraduate degree in 2020 as an adult student at Columbia’s General Studies program. And, although he is gay himself, he said his Gen Z classmates were markedly more likely to identify as “queer.”

[ A student newspaper poll found that the number of students at Brown who are LGBTQ+ jumped from 14% in 2010 up to 38% this year. ]

“Queer is as much politics as it is a sexual identity. Maybe even more so,” Appel, author of the forthcoming book “Cis White Gay: The Making of a Gender Heretic,” told The Post. “The Ivies have a lot of really privileged kids. I’m sure many are motivated to identify into a so-called marginalized community in order to earn some social cache.”

He thinks a growing number of amorphous labels allow more people to fall under the LGBT umbrella than ever before.

“The ‘trans’ and ‘queer’ umbrellas have expanded to include gender-nonconforming people and even people who would normally be considered straight,” Appel noted.

[ The share of heterosexual students at Brown dropped by 25.2% between 2010 and 2023. ]

Anthony agrees: “In some instances, a straight person will identify as bisexual but simply continue dating the opposite sex.”

Although Columbia hasn’t published similar figures, Appel and another Columbia graduate both estimate they are in line with other Ivy League schools.

“It’s becoming a majority,” an anonymous member of Columbia’s class of 2022 observed.

Appel said that Ivy League universities are particularly likely to have curriculum that is fixated on gender and sexuality.

“It makes sense that these polls were taken at Ivy League universities,” he told The Post. “Students take one queer theory course and come out as queer.”

At Princeton this year, 35% of seniors identified as something other than straight, compared with just 25% of incoming freshmen. And nearly one in five Princeton grads this year came out while in college.

Cornell developmental psychology professor and young adult sexuality expert Ritch Savin-Williams believes that Gen Z students are coming out in larger numbers due to increased social acceptance — especially on progressive campuses: “The shift has been in the visibility and the willingness of individuals to express it and to declare it.”

==

"Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome." -- Charlie Munger

#Rikki Schlott#LGBTQ+#LGBTQ#intersectionality#oppressor#oppressed#oppressor vs oppressed#queer theory#Ivy League#identity politics#bisexual#religion is a mental illness

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bisexual women with boyfriends are SO much louder than bisexual women with girlfriends. Gatekeeping isn't real and no one cares about your boyfriend just shut up

#I'm literally a bisexual woman with a boyfriend before y'all come for me#literally i see way more posts about how terrible it is to gatekeep than actual gatekeeping#it's also annoying to be like “leave your boyfriend at home” because acting like pride is still a queer safe space is a bit naive#y'all are fighting over a corporate parade just shut up#but seriously bi women with boyfriends need to stop acting like they're oppressed for dating men

15 notes

·

View notes