#berthier (classic)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jacques Augustin Catherine Pajou - Louis-Alexandre Berthier, Prince de Neufchâtel et de Wagram, maréchal de France - 1808

oil on canvas, height: 215 cm (84.6 in); width: 133 cm (52.3 in)

Palace of Versailles

Louis-Alexandre Berthier (20 November 1753 – 1 June 1815), Prince of Neuchâtel and Valangin, Prince of Wagram, was a French military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was twice Minister of War of France and was made a Marshal of the Empire in 1804. Berthier served as chief of staff to Napoleon Bonaparte from his first Italian campaign in 1796 until his first abdication in 1814. The operational efficiency of the Grande Armée owed much to his considerable administrative and organizational skills.

Born into a military family, Berthier served in the American Revolutionary War and survived suspicion of monarchism during the Reign of Terror before a rapid rise in the ranks of the French Revolutionary Army. Although a key supporter of the coup against the Directory that gave Napoleon supreme power, and present for his greatest victories, Berthier strongly opposed the progressive stretching of lines of communication during the Russian campaign. Allowed to retire by the restored Bourbon regime, he died of unnatural causes shortly before the Battle of Waterloo. Berthier's reputation as a superb operational organiser remains strong among current historians.

Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou (27 August 1766, Paris - 28 November 1828, Paris) was a French painter in the Classical style.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Act 3 - Death & Other Complications” Out Now!

It’s finally finished… and ahead of schedule again!

The unofficial continuation of the live-action “Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon” series continues with a brand-new episode: “Act 3 - Death & Other Complications”!

The mysterious girl from the future, Chibiusa, has dropped a bombshell on Ami Mizuno that threatens to upend her life. As each former Sailor Guardian is plagued with visions of the future, how can Ami cope with the knowledge of her personal destiny? Will she reclaim her powers, or succumb when she encounters the Black Moon Clan’s Berthier? And who is the mysterious Sailor Guardian that appears in her dreams?

New uniforms! New powers! Bold new takes on classic characters and timeless storylines!

“Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon Season 2: Black Moon” releases new episodes monthly on AO3, Wattpad, and FanFictonNet!

I’d be honored if you gave it a read. Feel free to leave a comment, as well. I answer all questions and comments from readers.

Archive of Our Own

Wattpad

FanFictionNet

#bishoujo senshi sailor moon#bssm#fanfic#pgsm#sailor jupiter#sailor mars#sailor mercury#sailor moon#sailor moon live action#sailor venus#pretty guardian sailor moon#ao3 fanfic#ao3#wattpad#fanfiction

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#my gifs#sailor moon#ayakashi sisters#sailor mercury#sailor venus#sailor jupiter#sailor mars#petz#calaveras#berthier#koan#90s anime#oldanimeedit#mine#gif#gifset#sailormoonedit

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Classic Hollywood Sailor Moon Villains - Berthier

Ref: Marie Wilson

#sailor moon#berthier#fan art#digital art#anime#villain#black moon clan#spectre sisters#krita#classic hollywood

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[CHARACTER] Berthier.

Series: Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon

Kana: ベルチェ Romaji: Beruche

Role: Villain Type: Humanoid (formerly), human (currently) Alignment/Organization: Black Moon Clan (formerly) First appearance: Episode 60 Last appearance: Episode 86 Status: Alive Voice actor: Yuri Amano

TRIVIA

Berthier’s name is derived from the mineral berthierite.

She was the second youngest of the Ayakashi Sisters.

Much like her rival Sailor Mercury, Berthier’s element was water.

In the manga, Sailor Moon killed Berthier. Yet in the first anime adaptation, Berthier survived and she was eventually purged of evil.

Berthier’s signature attack was Dark Water. In episode 71, Berthier attempted to kill herself as well as everyone else with Dark Water Full Power until Koan convinced her not to.

Berthier had a tendency to add the “chan” honorific to her droid’s names. In general, Berthier spoke formally with everyone.

Other Sailor Moon characters that Yuri Amano voiced are: Puko (episode 132), Kiriko (episode 145), and CereCere.

#sailor moon#berthier#black moon clan#sailor moon r#ayakashi sisters#ayakashi sisters (classic)#black moon clan (classic)#sailor moon (classic)#berthier (classic)#dark water#dark water full power#villain#villains (classic)#character#characters (classic)#episode 60#episode 61#episode 64#episode 68#episode 71#episode 72#episode 86

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

A book recommendation

The topic of book recommendations just came up. By coincidence I was about to recommend a book I recently acquired. The publisher threatens to unleash the Furies from Hades if anyone dares to reproduce anything from the book without written permission. But since this is a plug for this particular book, maybe they will tolerate my copying a couple of paragraphs to partly illustrate the author's point of view.

The book is called "The Eagle in Splendour: Inside the Court of Napoleon". It's by Philip Mansel, and my copy is from the Tauris Parke 2021 edition.

To whet your appetite, gentle readers, here are the promised extracts:

From pp. 1-2:

"Despite or because of his Jacobin past, General Bonaparte, First Consul of the French Republic, was an ultra-monarchist. In 1799-1804, at the same time as introducing a new constitution, with the Senate, Tribunate and Corps Législatif, he established a court system, in a calculated sequence of monarchising measures. First came a guard (1799); then official costumes (1800); residence and receptions in the Tuileries palace (1800-1); a chapel headed by his favourite composer Paisiello (...) (1802); a monarchy, a dynasty and a coronation (1804); finally a nobility (1808). The choice of such a system, when France was a victorious republic, and the rapidity with which the Republicans adapted to it, proves its appeal. The transformation of France into a republic in 1792 had been partly due to contingences: the 'executive gap' left by the absence of a vigorous monarch, minister or general; the radicalism of the National and Legislative Assemblies; and war."

From pp. 3-4:

"Napoleon I re-monarchised Europe as well as France. Not only did he appoint members of his dynasty: Prince of Piombino and Lucca (1805); Grand Duke of Berg (1805); and Kings of Holland (1806), Naples (1806), Westphalia (1807) and Spain (1808); but with a consistency revealing his monarchical principles, he also abolished all republics in Europe, old and new: Venice (1797), France (1804), Genoa (1805), Lucca (1805), Ragusa (1808), and the Cisalpine (1805), Batavian (1806) and Septinsular (1807) republics. He made Frankfurt, the classic German city-state, into a Grand Duchy (to which his step-son Eugene-Napoleon would have succeeded) and allotted 52 former 'free cities' of the Holy Roman Empire to different German rulers, or to himself. Thus, by 1812 he had placed every city in Europe under a monarch; even Swiss cities acknowledged him as 'Mediator of the Helvetic Confederation'. Europe was more monarchical than at any time since the rise of the Italian city states in the twelfth century."

I, for one, am hooked. I found the passage about France becoming a republic because of contingencies particularly interesting. To my mind it explains why it was so easy for even people as the Marshals to accept the return of the Bourbon monarchy, as well as explaining why Marshals such as Bessières and Berthier, both royalists in my opinion, were ready to serve the new, Napoleonic monarchy: the transition might have appeared to them as one from monarchy to Révolution and instability, to a new monarchy, and for Berthier, to the old Versailles monarchical dynasty again he knew so well.

I am not very far ahead yet in this book, but so far I love it and highly recommend it.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I really liked those “classic art in modern setting” pics. So I tried to do my own. Nap, Berthier and Jojo have their first encounter with modern means of transportation.

#napoleon's marshals#meandmylackofphotoshopskills#napoleon bonaparte#louis-alexandre berthier#joachim murat

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I loved your fantastic account of the battle of Waterloo and how each nation came to define the rest of the century for all the European countries in different ways. However what are your thoughts about the battle itself? Did Wellington win it or did Napoleon lose it? What were the turning points that you think determined the fate of the battle?

Thank you for reading and liking my previous post on Waterloo. I did heavily lean into studying ancient classical warfare when I was studying Classics but I only got into Napoleonic warfare because of a father who was (and still remains) big Napoleonic warfare military enthusiast. Through his keen eyes as a former serving military man, I also looked at the battle as a soldier might as well putting on my academic critical thinking cap. It’s a popular parlour game not just in Sandhurst but also in the officers’ mess (where those regiments actually fought at Waterloo) and around dinner tables - in my experience anyway.

I’ve always seen such speculative and counterfactual questions as an amusing diversion. I’ve never seriously looked at the detail until I came to France and unexpectedly interacted with Napoleonic scholars as well as soldiers (the cultured and historically well read ones at least) that forced me to think more about it. I’ve always been of the ‘if the Prussians hadn’t arrived in time to save Wellington’ school; and this was always enough to get me by in any conversation.

But my vanity was stung by interacting with one of my downstairs neighbours, a high decorated retired army general, with whom I played a weekly game of chess over a glass of wine during the Covid lockdown in Paris. He didn’t spare me as he knew so much detail about the battle. But a typical failing of French thinking is to pontificate around generalities rather than specific reasons. So for him it came down to pooh-poohing the generalship of Wellington (the rain saved him) and lauding the emperor (he had haemorrhoids and thus a bad day at the office). So rain and haemorrhoids were the decisive factors in determining the outcome of the battle of Waterloo.

It was clear I had to raise my game. So I’ve been reading more when I could.

I had recently finished reading a wonderful book ‘The Longest Afternoon: The 400 Men Who Decided the Battle of Waterloo’ by the Cambridge historian Brendan Simms. The book came out in 2015 but it’s been lying on my shelf for these past few years until I actually took this slim book to read on my one of my business trips.

The idea behind this short book is so superbly useful. It places to one side the huge, cinematic panorama of history and instead concentrates on one particular farmhouse, on one particular day: 18 June 1815. History is vivified, lifts itself off the page and into the mind, when a historian of Brendan Simm’s immense stature zooms in on the details - and here the details are compelling.

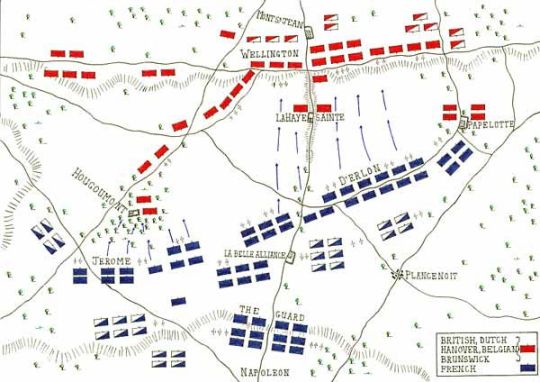

For the course of one day, 400 soldiers, wet, cold, in some cases hungover, who had bivouacked for the night in an abandoned farmhouse at La Haye Sainte, near a crucially strategic crossroads, found themselves staring down the massed barrels of Napoleon’s vanguard – and held them off. On June 18, 1815, Wellington established his position and sent one battalion and part of a second to the farmhouse under the command of Major Baring. Napoléon’s initial attack was a direct assault that surrounded the house and came near to breaking Wellington’s line; but it held, and the legendary charge of two British heavy cavalry brigades drove back the French.

This is a detailed account of the defence of La Haye Sainte, a walled stone farmhouse forward of Wellington’s centre. Its defenders were the King’s German Legion, which (despite the British army’s penchant for oddball names) was genuinely German. Britain harboured many German expatriates who detested Napoléon, a number augmented in 1803 when he occupied Hanover and disbanded its army. That very year two ambitious officers recruited the first members of the King’s German Legion, which grew into a corps of some 14,000 men and served with distinction at Copenhagen, Walcheren and in Spain before its apotheosis at Waterloo.

Ordered to capture the farmhouse, Marshal Michel Ney - commanding Napoléon’s left wing - obeyed but became preoccupied with his famously unsuccessful cavalry attack. Reminded of the order two hours later, he dispatched infantry that reached the house and set it on fire. The men inside controlled the blaze and continued to fight until Ney took personal charge of a furious assault that succeeded only when the defenders ran out of ammunition and withdrew, having held out for six hours. Had they not defended it so stoutly and if the farm had fallen any sooner then Napoleon would have been able to get at Wellington’s troops before his Prussian reinforcements arrived, and in all likelihood Waterloo would have been a French victory instead; it would now be the name of a train station in Paris rather than London.

I doubt there is a definitive answer to this question which is why certain people love arguing about it because it’s so open ended in terms of cause and effect. You can pick on any episodic event and hail that as the decisive turning point. It’s one reason why we are so fortunate to have so many well researched history books on the battle of Waterloo to replenish the issues for a newer generation to argue with past generations.

If I were to go beyond the ‘if the Prussians hadn’t arrived to save Wellington’ line then I would point to ten decisive turning points which in themselves might not have changed the outcome but taken together certainly influenced the final outcome of one of the most important and iconic battles in history.

Napoleon gives Marshal Davout a desk job

6 June 1815 – All commanders need a good chief of staff to ensure that their intentions are translated into clear orders. Unfortunately for Napoleon – as what is arguably one of the most decisive battles in European history loomed – his trusted chief of staff, Marshal Berthier, was no longer available. Berthier had sworn an oath of loyalty to Louis XVIII – and then fallen to his death from a window – so the job was given to Marshal Soult.

Soult was an experienced field commander but he was certainly no Berthier. Napoleon’s two main field commanders were also far from ideal. Emmanuel Grouchy had little experience of independent command. Michel Ney’s heroic command of the French rear-guard during the retreat from Moscow led Napoleon to dub him “the bravest of the brave”, but by 1815 he was clearly burnt out.

Worse still, when on 6 June Napoleon ordered his generals to assemble with their troops on the Belgian border he chose to leave behind Louis-Nicolas Davout, his ‘Iron Marshal’, as minister of war. The emperor needed someone loyal to oversee affairs at home but the decision not to take with him the ablest general at his disposal would deprive him of the one commander who might have made a difference.

Constant Rebecque ignores orders

15 June – In June 1815 Napoleon assembled 120,000 men on the Belgian border. Opposing him were 115,000 Prussians under Field Marshal Blücher and an allied force of about 93,000 men under Wellington. Faced with such odds, Napoleon’s best chance of victory was to get his army between his two enemies and defeat one before turning on the other. On 15 June his army crossed the frontier at Charleroi and headed straight for the gap between the two allied armies.

Wellington was taken completely by surprise: “Napoleon has humbugged me” he said. Uncertain what Napoleon’s intentions were, he ordered his army to concentrate around Nivelles, over 12 miles away from the Prussian position at Ligny. This would have left the two allied armies dangerously separated but fortunately for Wellington, a staff officer in the Dutch army, Baron Constant Rebecque, understood what was actually needed. He disregarded Wellington’s order and instead sent a force to occupy the key crossroads of Quatre Bras, much nearer to the Prussians.

D’Erlon misses the show

16 June – Two battles were fought on 16 June. While Marshal Ney took on Wellington’s army as it hurriedly tried to concentrate around Quatre Bras, Napoleon led the main French force against the Prussians at Ligny. Blücher’s inexperienced Prussians were given a severe mauling but despite this they managed to fall back in relatively good order.

This was partly due to a disastrous mix-up on the part of the French. Confusion over orders saw General D’Erlon’s corps instructed to leave Ney’s army at Quatre Bras and join the fighting at Ligny only to be recalled as soon as they got there. The result was that 16,000 Frenchmen who could have intervened decisively actually took part in neither battle.

Blücher stays in touch

17 June – Wellington succeeded in beating back Ney at Quatre Bras but Blücher’s defeat left the British general with a large French army on his eastern flank. He was forced to fall back northwards towards Brussels. The Prussians were retreating as well. Normally a retreating army tries to withdraw along its lines of communication (ie the route back to its base). Had the Prussians done this they would have headed eastwards. The two allied armies would then have been even further apart and Wellington would have been overwhelmed. But instead of doing that, the Prussians retreated northwards towards Wavre. It was to be a crucial move. The two allied armies stayed in contact and on 17 June Wellington was able to fall back to the ridge at Mont St Jean, and prepare to make a stand there until Blücher’s Prussians could come to his aid.

The weather takes a hand

17 June – The night before the battle was marked by a thunderstorm of biblical proportions. Rain lashed down, turning roads into quagmires and trampled fields into seas of mud.

It was a night of tremendous rain and cloudbursts. Wellington said that even in the monsoons in India, he’d never known rain like it. To wake up cold and damp, wet and terrified, then you have this slaughter in a very small space. By evening there were over 200,000 men struggling to kill each other within four square miles.

Private Wheeler of the 51st Regiment later wrote: “The ground was too wet to lie down… the water ran in streams from the cuffs of our Jackets… We had one consolation, we knew that the enemy were in the same plight.” Wheeler was right of course – the rain would inconvenience all three armies, not least the Prussians as they struggled along narrow country lanes to link up with Wellington.

It’s often said that Napoleon delayed starting the battle in order to allow the ground to dry out but the chief cause of the delay was probably the need to allow his units, many of whom had bivouacked some distance away, to take up their allotted places. Napoleon enjoyed a considerable advantage in artillery at Waterloo but this was lessened by the fact that the mud made it difficult to move his guns around and that cannonballs, normally designed to bounce along until they hit something, or someone, often disappeared harmlessly into the soggy ground. Macdonnell closes the gates

11:30am, 18 June – On 18 June the two armies prepared to do battle. Most of Wellington’s troops were sheltered from enemy fire on the reverse slope of the Mont St Jean ridge. The position was protected by three important outposts: a group of farms to the left, the farm of La Haye Sainte in front and the farmhouse of Hougoumont to the right.

At about 11.30am the French launched their first attack – an assault on Hougoumont. This soon developed into a battle within a battle as the French threw in ever more men in a bid to capture the vital chateau. They nearly succeeded: led by a giant officer nicknamed ‘the Smasher’, a group of French soldiers worked their way round to the rear of the chateau, forced open its north gate and burst inside.

James Macdonnell, the garrison commander, acted quickly. He gathered a group of men and they heaved the gate shut again. The French inside the chateau were then hunted down and killed. Only a young drummer boy was spared. Hougoumont was to remain in allied hands all day and Wellington later commented that the entire result of the battle depended on the closing of those gates.

Ney loses his head after his cavalry founders

1.30pm – The infantry of D’Erlon’s corps finally saw action as they attacked the left wing of Wellington’s army. As they reached the crest of the ridge they were met by the infantry of Sir Thomas Picton’s division. Picton, a foul-mouthed Welshman who rode into battle in a civilian coat and round-brimmed hat, was shot dead but his men stopped the French, who were then driven back by Wellington’s cavalry.

The next major French attack was very different. Ney unleashed his cavalry in a mass frontal attack, and thousands of Napoleon’s famous cuirassiers – big men in steel breastplates riding big horses – thundered up the hill. But Wellington’s infantry stayed calm. Forming squares, they presented in all directions a hedge of bayonets that no horse could be made to charge.

Ney needed to call the cavalry off or support them with infantry but he lost his head and threw more horsemen into the fray. When he abandoned these fruitless attacks, Wellington’s line was still unbroken, two hours had been wasted, and the Prussians were arriving in force.

The Prussians arrive

4.30pm – Blücher had promised to come to Wellington’s aid, and kept his word. Napoleon had detached nearly a third of his army under Grouchy to prevent the Prussians joining up with Wellington but Grouchy failed to do this and, by mid-afternoon, the first Prussian units were in action on the battlefield.

At about 4.30pm they launched their first attack upon the key village of Plancenoit near the rear of Napoleon’s main position. This savage battle would rage for over three hours. Faced with this, Napoleon was forced to send many of his remaining reserves to shore up his position – leaving him with precious few troops to exploit any success his troops might enjoy against Wellington.

Napoleon says no, and von Zeithen turns back

6.30pm – At about 6.30pm the French captured La Haye Sainte. Posting artillery and skirmishers around the farm, they unleashed a storm of shot, shell and musketry into Wellington’s exposed centre. The regiments there suffered horrendous casualties, but Wellington’s line held – just.

Ney asked for reinforcements to press home his advantage but Napoleon refused. Instead he sent troops to recapture Plancenoit which had just fallen to the Prussians. Von Zeiten’s Prussian I Corps arrived on the scene. These much-needed reinforcements were set to join Wellington when a Prussian aide de camp rode up with an order from Blücher instructing them to head south and support his troops at Plancenoit. Von Zeiten obeyed. Realising that Von Zeiten’s troops were desperately needed on the ridge, Baron von Müffling, Wellington’s Prussian liaison officer, galloped after Von Zeiten and pleaded with him to ignore this new order and stick to the original plan. The Prussian general turned back and took his place on Wellington’s left, enabling the duke to shift troops over to reinforce his crumbling centre. The crisis had passed.

Napoleon’s last roll of the dice ends in panic

7.30pm – With Plancenoit back in French hands the stage was set for the final act in the drama. At about 7.30pm Napoleon unleashed his elite imperial guard in a last desperate bid for victory. But it was too late – they were hopelessly outnumbered and Wellington was ready for them. His own troops had been sheltering from the French fire by lying down but when the two large columns of French guardsmen reached the crest of the ridge Wellington ordered his own guards to stand up. One British guardsman describes the scene: “Whether it was (our) sudden appearance so near to them, or the tremendously heavy fire we threw into them but La Garde, who had never previously failed in an attack, suddenly stopped.”

Meanwhile Sir John Colborne of the 52nd Light Infantry wheeled his regiment round to attack the flank of the first French column while General Chasse ordered his Dutch and Belgian troops forward against the other. Soon both French columns had withered away under the deadly fire. Their defeat led to widespread panic in the French army: amid cries of “La Garde recule” (“the Guard is retreating”) it dissolved into a disorderly retreat mercilessly harried by the Prussians. “The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life,” as Wellington described the battle, was over.

This isn’t an exhaustive list but it will do.

Waterloo was a watershed moment for Europe, and indeed the world. The end of the Napoleonic Wars heralded a peace in Europe which was not broken until the outbreak of World War One in 1914. In the century following the Battle of Waterloo an increased respect developed for the figure of the soldier. True the Battle became mythologised in the nineteenth century and is now embedded in our cultural memory as one of the great British success stories.

We still celebrate Waterloo because it was a great British victory - even if we had a little bit of help from the Prussians. It embodied the British bulldog spirit and marked the moment we finally overcame Napoleon and his empire after a decade of being at war.

The ramifications from Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars are still felt today in contemporary European politics. I think because of this the battle continues to fascinate and to court intense discussion and disagreement.

No doubt my French neighbour the retired army general and I will continue to stubbornly argue our differing viewpoints until the wine bottle empties. But we both agree that we would enjoy having dinner with Napoleon and talk about his military campaigns. I admire Napoleon a little more having read more and for living in France. He’d be a very amusing and stimulating companion.

In many ways, he was also an enlightened and intelligent ruler. His Code Napoleon is an extremely enlightened law code. At the same time this is a man who had a very, very low threshold for boredom. I think he was addicted to war.

General Robert E. Lee, at Fredericksburg said, “It is well that war is so dreadful, otherwise we would grow too fond of it.”

Napoleon would never have agreed with that. War was his drug. There’s no evidence that Wellington enjoyed war. He said after Waterloo, and I believe him, “I pray to God that I have fought my last battle.” He spent much of the battle saying to the men, “If you survive, if you just stand there and repel the French, I’ll guarantee you a generation of peace.” He thought the point of war was peace. And he sure gave not just Britain but also an entire European continent some respite from the spilling of blood on a battlefield.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#waterloo#battle#battle of waterloo#napoleon#wellington#history#britain#france#prussia#austria#german#europe#military#british army#soldier

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Baptiste Berthier

In honor of Berthier's birthday, I thought it would be interesting to know a little more about where he came from. Luckily I have a biography by Franck Favier, who has a whole chapter dedicated to the origins and social rise of his family. His father comes across as quite a successful and hard-working man. We can see how such a man would influence our Berthier's work ethics and character.

Please be indulgent, I translated this a little too fast to be really good, but I did my best to be in time.

What a destiny for this family of the Ancien Régime: in three generations, it climbed the ranks of society, passing from the status of ploughman to the splendours of Versailles, then to that of Prince of the Empire! The ascent surprised, because the Berthier family escaped the inevitability of a predetermined fate.

The Berthiers come from the village of Chessy-les-Prés, on the borders of Champagne and Burgundy. The great-grandfather, Rodolphe (1648-1710), was a ploughman, then a laborer. He married a ploughman's daughter, Marie Branche, in 1671. From their marriage were born at least two children who reached adulthood, François (1676), and Michel (1679). The first seems to have known a relative social stagnation by remaining a ploughman, while the second progresses: between the two births, their father Rodolphe passed to domestic service, in the service of Michel de Changy, Lord of Vézannes, who will be the godfather of little Michel.

This parrainage appears providential, because it allows Michel to escape the peasant world to embrace the career of wheelwright, probably with the wheelwright of the seigneury. He then emigrated to the town of Tonnerre, a classic sign of local rural exodus. In 1712, he married Jeanne Dumez, daughter of the servant of the bailiff of Noyers. The Lord of Vézannes still appears as a co-signatory of the act. From their marriage six children are born: four daughters [...] and two sons of whom only Jean-Baptiste, born in 1721, reaches adulthood [...]

Jean-Baptiste enters the service of the seigneurial family. Destiny steps in: Jean-Baptiste inherited from his wheelwright father qualities in mathematics and geometry which surprised his master. The latter then plays his connections, which allows Jean-Baptiste to enter the Ministry of War in 1739 as an instructor, then in 1741 as inspector general at the Ecole de Mars, military academy of Paris [...] There he was responsible for making young nobles maneuver. His studies subsequently pushed him from geometry to topography. As inspector, he proposed to modify the training programs and obtained a little more practice: he built on Ile aux Cygnes, in Paris, a miniature fort called Fort-Dauphin for the exercise of a siege. In front of the marshals of France and the people of Paris, the cadets and officers mimed the assault and the defense of the work.

However, it was during the War of the Austrian Succession that Jean-Baptiste's career took a new turn. In 1744 he obtained a lieutenancy and a job in the body of geographic engineers.

This body of engineers, founded in 1691 by Vauban, was made up of soldiers specializing in topographical surveys. They quickly distinguished themselves from ordinary engineers, more occupied with fortification work, and brought together experts recognized for their skill and dexterity in drawing up maps that were very useful for military strategies. The function required physical (endurance), but also intellectual (geometry, trigonometry and drawing) and military (fortifications) qualities. It repulsed highborn people, but was a means of social advancement for individuals of more modest condition.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Fontenoy (1745), Jean-Baptiste Berthier joined the army, assigned to the staff of Marshal de Saxe, commanding the army of Flanders, as an engineer geographer serving for reconnaissance of the camps , marches and locations of the king's armies. He took part in the Dutch campaign, was noticed at the battle of Lawfeld on July 1 and 2, 1747, where he was also wounded. The war allowed him to show his skills and courage on the ground. On this occasion, he established an album of twenty-five maps relating the main facts of the campaign, an album which he offered to the king.

His reputation being made, he can consider another means of ascension: marriage. On September 23, 1749, he married Marie Françoise Lhuillier de La Serre, born in 1731, whose father, César Alexandre, was captain of the castle of the Marquis de Breteuil, in charge of the surveillance and hunting of the estate [..] All were from recent nobility [..]

Jean-Baptiste thus entered the networks of geographers, important networks which tended to perpetuate themselves, by endogamy, in castes, without progressing, unlike the Berthiers. Fortune was to further benefit the family, already well served: on September 13, 1751, a fireworks rocket celebrated for the birth of the Duke of Burgundy set the Great Stable of the Palace of Versailles ablaze. Faced with the improvisation of the emergency services, Jean-Baptiste Berthier takes the responsibility of organizing the fight against the disaster, even putting his body on the line. Louis XV, who witnessed his exploits in person, would be grateful to him. He will thus enter into the favor of the sovereign. He will be in charge of multiple tasks, participating for example in the founding of the Military School of Paris from 1751 or also, through his plans and drawings, in the improvement of French military ports.

1753 saw the birth of his first son, Louis-Alexandre, the eldest of an upcoming series of twelve children, six of whom survived the horrors of infant mortality. In 1757, Jean-Baptiste acceded to the post of chief geographer engineer and to the direction of maps and plans of the Ministry of War. As such, he is in direct contact with the King and the Minister of War, to whom he can present each morning, with supporting maps, the operations of the French army during the Seven Years' War. As for his wife, she is assigned the much sought-after office of Monsieur's chambermaid. This charge made it possible to penetrate even further into the King's House. Monsieur will also honor the Berthiers by holding on the baptismal font one of their sons named after himself, Louis-Stanislas, born in 1767, while one of their daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette, born in 1757, had for godmother the Marquise de Pompadour.

[..]

The Duke of Choiseul demanded from Berthier the construction of the hotels of the Navy and Foreign Affairs. The work was quickly completed, in eighteen months. Speed, reasonable cost, architectural elegance, richness of ornamentation, ingenuity of interior design are admired by contemporaries [..] Moreover, always pragmatic, Berthier innovated in memory of the fire of 1751: he decided to replace everywhere the parquet floors with tiles, and developed a new system of incombustible brick vaults.

In July 1763, the king, as a reward, appointed him chief geographer of the king's camps and armies, governor of the War, Navy and Foreign Affairs hotels, and raised him to the nobility by letters patent established in Compiègne [..]

To these honors was added a salary of 12,000 pounds per year, half of which went to his widow and reversible to his children. It was the peak for Jean-Baptiste Berthier, who decided to have his portrait and that of his wife painted, signs of his notability. In 1765, he received the order of Saint-Michel, and two of his children have, as we have seen, illustrious godfather and godmother.

His new status giving him the privilege of being able to practice hunting, he associates the useful with the pleasant. At the request of Choiseul, then to that of the king, he established numerous hunting maps for most of the royal forests: Amboise, Rambouillet, Versailles, Marly, Saint-Germain, Sénart, Boulogne and Vincennes. This considerable work, unfinished during the Revolution, will be completed by his son, the future marshal.

[..] Having reached the peak of his career, Jean-Baptiste Berthier can look at his career with satisfaction. Despite his words: "I am no richer than when I was born in Tonnerre from the poorest citizens of this city", his rise is remarkable.

Beyond the titles and honors accumulated by the engineer Berthier, we will notice the extent of family and matrimonial alliances. The Berthier couple had twelve children, five of whom, along with the marshal, reached adulthood. Among those who survived, the two daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette (1757-?) And Thérèse (1760-1827) made excellent marriages [...] Of the four sons, three will be, under the Revolution and subsequently, illustrious soldiers: Louis-Alexandre marshal, Louis-César (1765-1819) and Victor-Léopold (1770-1807), major generals. The fourth son, Charles, born in 1759, nicknamed Berthier de Berluy to differentiate him from his elder Louis-Alexandre, died during the American expedition.

[..]

General Thiébault, then in garrison at Versailles, reports in his Memoirs of his meeting with old Jean-Baptiste in 1803.

"One morning, as I was having breakfast, a little old man who was still green came into my house, and who, in a deliberate tone, said to me:" Would you like, Monsieur le Général, to receive a visit from the father of the Minister of War, of General Berthier? " I hastened to answer that I would have hastened to offer this to him, if I had known that he was in Versailles, and I could have added if I had known that he was still in this world. He told me that he resided in Paris, but that, having come to Versailles on business, he had not wanted to leave it without seeing me. "From your place," he said, "I will visit, as is my habit, the Hotel de la Guerre which was built by me, where I lived so many years and where all my children were born. "I insisted that he do me the honor of having lunch with me, but he only accepted a cup of coffee, and the idea occurred to me to suggest that I accompany him to the Hotel de la Guerre, which he was delighted with. We left together, and if it had been about selling it to me, he could not have shown me this hotel in more detail and told me more exactly the history of all this construction from the cellars to the attics. When, after one hour, we reached the attics, he said: "This is the accommodation that I was occupying ", and having stopped in a rather small and more than modest room with alcove:" Here is ", he added with pride," where Alexandre was born. "And on this subject he recounted many memories to me. We would have been by the cradle of the Macedonian king that Macedonia could not have been complete. Convinced that he had kept this place for the last bouquet of what he wanted to show me and teach me, I thought I was at the end of my chore. I had already congratulated him on his legs which seemed to find in this building the vigor they had during the construction, when he warned me that what was most curious to see, was the roof. Immediately he passed through a window, and drawing me as if to a trailer, but running, climbing like a cat, he walks me from ridge to ridge, from gutter to gutter, at the risk of breaking my neck twenty times. "

Six months later he passed away. He had fulfilled his role of dynastic founder to the best of his ability. He endowed his descendants, either by marriages for his daughters, or by a perfect education for his sons. The fact that he gave Alexandre as a second name to his eldest son and César to his third son could presage Jean-Baptiste's military ambitions. He was not disappointed.

Franck Favier- Berthier, l'ombre de Napoléon

I hoped you enjoyed this!

#napoleonic#louis alexandre berthier#franck favier#berthier l'ombre de napoléon#jean-baptiste berthier#papa berthier#another tireless and skillfull berthier#the anecdote reported by thiébault made me smile#papa berthier would have whipped out the baby pictures if he could#also: proof that the ancien régime society wasn't that frozen that you couldn't make yourself a place#happy birthday berthier!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Some) Greek Gods as Historical Figures

So some days ago I secretly logged back into Mythology and Cultures amino and I stumbled across post of casting historical figures as the gods from Greek mythology. Of course, I hated it, so I made my version of this.

Note: Of course, this is going to have quite a lot of Napoleonic figures, since I am more familiar of this period, but please do reblog this post (or tag me on another post) with the hashtag “#mythical figures as historical people” and add some more of your historical figure Greek God fancasts!

Note 2: this post is for entertaining purpose, and just me introducing some guys to y’all and I am not a historian myself and hopefully you all would still like my takes😅

1. Zeus - Louis XIV of France

First and foremost, I shall introduce the king of gods featured in Greco-Roman myths. You may ask, why don’t I cast Henry VIII of England? Well, my reason is very simple: Henry is far from accurate to Zeus in actual myths.

To be honest, Zeus has a more “absolute power” energy in it, and Louis XIV totally has rocked it (like that iconic line “l’état, c’est moi (I am the state)”). Well, Henry also has that kind of energy but everyone only remembers his six wives and the uncountable number of bloodshed (not to mention Catherine of Aragon is a much better fighter than him—got this from Horrible Histories OwO)... Anyways, Louis XVI is basically a Zeus.

2. Hera - Catherine of Aragon

This brings to Catherine of Aragon herself. She’s a total Q U E E N and if you have watched “Six” the musical you already got what I mean (like, being the wife who married to Henry the longest). There’s also the early warlike aspect in Hera (featured in Homer’s works) that Catherine has it as well (at least you know that she’s getting more victories than Henry if you have watched Horrible Histories season 6, in the episode with Rowan Atkinson playing Henry VIII (which is sad because I want Ben Willbond to play him—he iconic to the HH fandom)), making her a great casting of Hera.

Hera, in my opinion, is a very strong woman who has to take Zeus’s shit and I could totally understand why she took revenge on the girls that Zeus has slept with—but anyways, hopefully you guys would like it :3

3. Aphrodite - Pauline Bonaparte

This is half-self-explanatory, really—just look at that statue she posed as Venus, the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite.

Pauline was famed for her beauty in her time, also a big chunk of scandals from her affairs (which bugs her big brother Napoleon, a lot). Nevertheless, despite her big spending habits and a great sexual appetite, she always helped Napoleon in some surprising ways (like she sold her house in Paris to the Duke of Wellington to get the funds for Napoleon).

Just like Aphrodite herself, Pauline harnessed her beauty very well. Thus, I rest my case.

4. Apollo - Joachim Murat or Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

(Warning: long content ahead)

Firstly, let me briefly introduce them because you guys might not know them much.

Joachim Murat was a marshal of France, also one of Napoleon’s brother-in-law, grand duke of Berg and Cleves from 1806 to 1808 and the King of Naples from 1808 to 1815. After the wars, he attempted to escape yet was caught and executed in 1815 in Pizzo, Italy (if you have read of Alexandre Dumas’s “Famous Crimes” you might know him—by the way no one has cut his head off and sent it to that big nose King Ferdinand).

For those who have watched “Elisabeth” or the “Sissi” movies, you might know Franz Joseph I of Austria already but you might not know much about himself besides being the husband of the (in)famous Empress Sisi (ie. Empress Elisabeth of Austria). He was the Emperor of the Austria from 1848 to his death in 1916—one of the longest reigning European monarchs in history. During his reign, the empire had been through a lot of change, most notably, the creation of Austria-Hungary. Nevertheless, he was also the Emperor who started World War I and he died of old age in the midst of the Great War.

For Apollo, I’m not casting musicians because this is quite overdone. I rather want to shed a light to the other arts that he represented in Greco-Roman mythology. This makes me want to draw a parallel to Joachim Murat as he was also a great sucker of classical literature. Plus, he also was known to be a flamboyant dresser (his nickname was “the Dandy King” by the way), also the designer of the uniforms of the Neapolitan army (with an excessive amount of amaranth, perhaps his favourite colour). Really, everyone just sees him as a great flamboyant himbo but in reality, he’s iconically badass in the battlefield as the First Horseman of Europe. Well, also he’s known for being extremely good with women even though his wife Caroline was fierce as hell. So, in my opinion, he fits the image of Apollo that we know.

However, you guys might feel surprised why I picked Franz Joseph for Apollo. Well, he really... was a rather mediocre ruler in my opinion, and perhaps our most memorable image of him was the senile emperor who signed the declaration of war to Serbia. Nevertheless, he was a well-liked man among his subjects, at least to some old citizens of Austria-Hungary telling future generations. Besides, culture flourished in Vienna under his reign—with notable figures like Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Erwin Schrödinger. Despite the series of unfortunate events which made the empire started to crumble, Austria-Hungary arguably has its cultural importance in Europe. Sounds like what Apollo would do if he’s a ruler, somehow.

Well, enough of his political achievements, let’s talk about his private life... which was probably the actual reason why I picked him.

Enter Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria, the Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary, also known as Sisi.

On a side note, Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier of France, Prince of Neufchâtel and of Wargram, was Empress Sisi’s grand-uncle in-law via his marriage to Duchess Maria Elisabeth in Bavaria

Absolutely love Pia as Elisabeth in the musical so please don’t mind me using a gif from this :3 ((also, “Elisabeth” spoiler alert

Franz originally was to marry her sister Helene (nicknamed Néné), nevertheless, on the first meeting in Bad Ishl, he has fallen for the young Elisabeth, head over heels—making him defying his domineering mother, Archduchess Sophie, for the very first time. Elisabeth also liked him and did not expressed her refusal either, so they got married in St. Augustine’s Church in 29th April, 1854.

However, the marriage was not well. Sisi was not accustomed to the strict Austrian court especially Archduchess Sophie (also she was not really a fan of intimacy). Poor Franz was rather helpless in situations between his mother and his wife, and eventually, Sisi chose her freedom over her duty as Empress, traveling around the world. They two briefly went back together during the Austro-Hungarian compromise, yet she was constantly not there. Eventually, Sisi was assassinated by an anarchist named Luigi Lucheni during her stay in Geneva, Switzerland, and Franz was devastated over her death (“she will never know how much I love her”).

To Franz, he loved her so, but he really didn’t understand her needs. Even though he had countless mistresses and female companions in Vienna, he still missed his wife. I say, he was really unlucky when it comes to love. Like Apollo himself, he dated countless nymphs and humans, but a lot of his notable relationships did not have a good end. (Probably Cyrene was the most lucky one, yet she also has chosen to be left alone after mothering several children with Apollo.) For this, I picked Franz Joseph as Apollo.

5. Ares - Jean Lannes or Michel Ney

As usual, for those who don’t know much history, I shall briefly introduce my babeys these two great soldiers.

Jean Lannes was one of the marshals of Napoleon, known for being one of Napoleon’s closest friends and his fiery personality, and is considered one of the best marshals of the 1st French Empire. His finest moments including the Battle of Ratisbon in which he led his men to storm the well-guarded city with ladders (hence his nickname “ladder lord” in our very humble Napoleonic marshalate fandom :3). Sadly, he died of the wound he received in the battle of Aspern-Essling in 1809.

Michel Ney was also one of the marshals of Napoleon, known for his extreme valour (yep, he is known as the “Bravest of the Brave”). As you might know, he was one of the marshals who was in Waterloo, yet, his finest hour was during the retreat from Russia in the disasterous 1812. Sadly, he was arguably the most prominent victim of the White Terror under the second Bourbon restoration, executed in 1815 (**I am not accepting any kind of conspiracy theories of my babey survived and died in America😤).

Speaking of Ares, I have a lot of things to say (that’s my dad ;-; no jkjk). He is really not that bloodthirsty idiot who casually hates humans. Well, he’s more like a fiery dork and a man who was very faithful to his lovers, and fights very well (by the way also one of the best dads). So, the bois that come into my mind are automatically two of the most courageous marshals of France.

Lannes, if I have to get him a godly parent, it would definitely Ares. He resembled the god a lot (also I sometimes imagined Ares as a smol bean with dark hair), probably looks the most like Ares himself. He got that fiery temper, that faithfulness to his wife Louise, also being a very courageous fighter in the field—well he literally was like, “NO LEMME STORM DAT CITY *grabs ladder*”.

There you have it, my big bro our ladder lord Jean Lannes who can pull off a perfect Ares.

Ney is like a slightly introverted (and mature) version of an Ares person. You can guess his temper already through his famed auburn hair, and indeed despite his shy exterior his temper sometimes was a bit explosive, and a bit impatient (which was somehow one of his fatal flaws). He was a great fighter, known as a skilled swordsman in his youth. And you all know how brave he is in his famed epithet. Michel Ney is purely badass (and C U T E) you know (and he needs a lot of hugs because he has really been though a lot in the wars, and was a possible case of PTSD which was shown in his arguably suicidal behaviour during the battle of Waterloo). That’s why I casted him as the Greek god Ares OwO

//

And there you have it, my interpretations on the Greek gods via people in history. I originally would like to include more but somehow I realised that I have written too much about my picks. So, if you want to add more, reblog this post or tag me on the post you made on this topic (and please use the hashtag “mythical figures as historical people” so that I could look into your choices via the search bubble on this app🥺).

Last but not the least, I hope you all lovelies like this, also have learnt something new via my brief introductions on some historical people. Have a great day!

#greek mythology#finally some Greek mythology content#i hope you all don’t mind me overselling my bois#no shipping intended on the castings#this is from an ex-Hellenic devotee who had been in Classics class#Zeus#Hera#Aphrodite#Apollo#Ares#methods of procrastinating from university tasks and responsibilities#why am I still up in 2am I said I would get a proper sleep tonight for excessive headbanging to David Bowie for his birthday🌚#the relationship between Franz and Sisi got me sobbing all the time#Louis XIV#Catherine of Aragon#pauline bonaparte#joachim murat#franz joseph i#elisabeth of austria#elisabeth of bavaria#empress sisi#jean lannes#michel ney#mythical figures as historical people

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the Bonapartes: Pauline (3/3)

[Part 1] [Part 2]

Following the untimely death of Leclerc, Pauline’s brothers were anxious to find her a new husband--preferably a politically advantageous one. Napoleon had hoped to marry her to Francesco Melzi d’Eril, a wealthy Milanese nobleman who had just become the Vice President of the Italian republic (Napoleon himself being the president), but Melzi respectfully declined. On August 28, 1803, Pauline was married to twenty-eight-year-old Don Camillo Filippo Ludovico Borghese, Prince of Sulmon and of Rossano, Duke and Prince of Guastalla, who, in the words of Hortense de Beauharnais, “was not particularly clever but good-looking and who possessed a great fortune in Rome.” Napoleon was lukewarm to the match and, like Pauline, quickly came to regard Camillo as “an imbecile” (Napoleon, who adored bestowing derogatory nicknames on people, would also style Camillo as “His Serene Idiot”). The pair had no real chemistry and the marriage turned sour in no time.

[Camillo Borghese]

In the summer of 1804, however, Camillo, still enthralled by his wife’s beauty, commissioned the sculptor Antonio Canova to immortalize Pauline in white marble. Canova was initially reluctant to accept the commission--until he laid eyes on Pauline in person, after which he agreed to begin working on it within a month. To Canova’s suggestion that he depict her as Diana, the virgin huntress, Pauline laughed, saying “No one would believe in my chastity.” She insisted on being portrayed as Venus, the goddess of love.

[Canova’s statue of Pauline as Venus Victrix]

It was in August of 1804 that the relationship between Pauline and Camillo ruptured, and it would remain ruptured seemingly past the point of repair for the next twenty years. On the 14th of August, Dermide, Pauline’s only child with Leclerc, died in Rome after falling ill with a fever. Pauline was in Tuscany at the time, trying to reestablish her poor health. The news was first received by Camillo, who, anticipating his wife’s blame, had it kept from her for several days. “Pauline will regard me with horror!” he declared. “Wasn't it I who wanted her to leave her son in Rome? No doubt he would have died anyway, but she is bound to accuse me of his death.” Finally, one of Pauline’s attendants was forced to reveal the news after arousing her suspicions. Pauline raged at Camillo as “the butcher of my son” and ordered him out of her sight. The break between them was complete, and quite public. Pauline viciously hinted to her companions that Camillo was impotent, declaring that "to give oneself to Camillo was to give oneself to no one." She showed no interest in attempting to provide him with an heir, and took great delight in humiliating him by embarking on a series of openly flaunted love affairs. For his part, Camillo soon began a long-term affair with a distant cousin, the Duchessa Lante. From this point, Pauline and Camillo would lead mostly separate lives, until the final months of Pauline’s. Having never truly enjoyed Rome, she now grabbed any opportunity she could find to escape it.

In 1805, she began the first of the only two of her numerous affairs in the aftermath of Leclerc’s death in which she showed a legitimate, deep attachment to her lover. While taking the waters at Plombières, she met an artist, the thirty-year-old Comte de Forbin, and fell madly in love with him. Pauline soon made Forbin her chamberlain, so he could be with her constantly. The affair lasted for the next two years and, writes Pauline’s biographer Margery Weiner,

was so intense, passionate and almost fatal because her obsession with him was so great that she declined visibly, although nothing would persuade her to detach herself from him; no doubt in temperament Forbin had much in common with Murat.

[The Comte de Forbin]

The eventual decline in her health was so great that a renowned gynecologist, Dr. Hallé, was called in, to consult with Pauline’s personal physician, Peyre. Hallé explained the situation in a letter to Peyre as follows:

Her habitual and constant state is one of uterine excitement and if this state is continued and prolonged it can become alarming. The spasms I saw in her arms were hysteric and so were the headaches. Her general condition is one of exhaustion. I talked to her in general terms about everything which contributed to the uterine irritation and I thought she listened to me but I'm afraid not sufficiently. One cannot always make douches responsible and one must suppose that in a young, pretty, sensitive and solitary woman, who is visibly fading away, there is a constant cause for this decline. Whatever this cause is it is time and more than time to eliminate it.

Napoleon was greatly displeased by the stories reaching him in Paris of his sister’s behavior in Rome. “Do not count on me for help,” he wrote to her, “if at your age you let yourself be governed by bad advice,” adding that if she continued to quarrel with Camillo, “France will be closed to you.” For good measure, he had their uncle Cardinal Fesch, write to Pauline to tell her, “on my behalf, that she is no longer pretty, that she will be much less so in a few years, and... she should not indulge in those bad manners which the bon ton reproves.”

Pauline’s affair with Forbin ended only when Forbin accepted an appointment in the army--whether at his own request, or at the insistence of Napoleon, remains unclear. Pauline soon moved on to other amusements. While staying in Nice during the winter of 1807-8, a young violinist, Felice Blangini, caught Pauline’s wandering eye. Pauline offered him the post of her chef d’orchestra (she had no orchestra). Blangini was a shy man, of a much humbler station than his predecessor Forbin, and found his suddenly elevation vaguely terrifying. "I knew,” he wrote later, “that the Emperor was kept informed of what his sister did, the names of her intimates.” But he lacked the will to stand up to Pauline, and submitted to being paraded around by her in public. It was with considerable relief on Blangini’s part that the affair was abruptly ended when Napoleon appointed Camillo governor-general of the Transalpine Department of the French Empire, and ordered him and Pauline to travel to Turin together to take up the seat.

Pauline, disgusted at finding herself shackled to Camillo once more, made the journey to Turin as quarrelsome as possible. At one point she reminded her husband "in a not very amiable fashion that he was only governor-general by virtue of being her husband, and that he would be nothing if he had not married the Emperor's sister. Which," recounts Maxime de Villemarest, the secretary who accompanied the pair, "had some truth in it." To which Camillo responded in "the most piteous manner" (in the words of de Villemarest) with cries of "Paulette! Paulette!"

By mid-1808 she had already found a way to escape from Camillo and Turin (she insisted to Napoleon that the climate was bad for her health) and was back in France once more. Added to her delight was an increase of her income by Napoleon to six hundred thousand francs, a sum that Napoleon rendered off-limits to Camillo. In Paris she presided regularly over balls and cercles, and in no time had resumed her position as one of the central figures in Parisian society. In the words of one of her neighbors, Stanislas de Girardin,

Pauline Borghese was then in the full brilliance of her beauty. Men pressed about her to admire her, to pay court. And she enjoyed this homage as her due. In the glances she exchanged with some of them, indeed, there was a recognition of past favors granted or hints of romance to come. Few women have savored more the pleasure of being beautiful.

She was one of the few people in whom Napoleon found comfort following his divorce with Josephine--an event which pleased Pauline greatly--in December of 1809. She was less pleased at Napoleon’s choice for a new bride--the teenage archduchess Marie-Louise--and sulked with her sisters over having to carry the bride’s train at the imperial wedding. The Countess Potocka has left this innuendo-laden description of Pauline from around this time (the italics are hers):

Princess Pauline Borghese was a type of classical beauty to be found in Greek statues. Despite the things she did which hastened the ravages of time, in the evening, by the aid of a little artifice, she captured all suffrages, and not a woman would have dared to dispute her the apple which Canova awarded her after unveiled contemplation, as it was said. To the most delicate and regular features imaginable she added an admirable figure too often admired. Thanks to so many graces, her wit passed unnoticed; nothing but her gallantries were spoken of, and certainly they gave plenty of matter for discussion.

After brief liaisons with Russian general Prince Alexander Tchernitcheff and Polish general (and future Marshal) Józef Poniatowski, Pauline embarked on her second of the two aforementioned love affairs in which she genuinely seems to have fallen for her partner. This time, her lover was a young hussar from Berthier’s staff named Jules de Canouville, who became fiercely devoted to her. At Pauline’s request, Napoleon made de Canouville a baron, but the young man (and his affair with Pauline) soon incurred the Emperor’s wrath. Napoleon sent him to Marshal Masséna in Spain, bearing dispatches (and a secret order to Masséna to keep the young man in Spain until further notice). It didn’t go quite as Napoleon had planned. Pauline’s biographer Fraser describes de Canouville’s journey:

Even in the midst of this duty, de Canouville thought only of Pauline. Knowing that, with her, to be absent was to be soon forgotten, he covered 170 relays at a gallop, a distance of over seven hundred miles, and arrived a few days later, covered in mud, at headquarters in Salamanca. There he learned that the supply lines to Portugal were cut and resolved to return the next day to Paris with the news, rather than pursue his quarry further. An hour without Pauline, he said, was a desert, and he whiled away the evening while telling all who would listen that Napoleon had charged him with his mission only by way of vengeance.

[Jules de Canouville]

In 1812, he departed with the Grande Armée for Russia, where he served on the staff of Pauline’s brother-in-law Murat, who kept Pauline apprised of de Canouville’s whereabouts--and also informed her of his death at the battle of Borodino on 7 September. News of de Canouville’s death hit Pauline hard. “Apparently this braggart cavalier,” writes Fraser, “with his joie de vivre and optimism, had touched in Pauline some chord that her other, more sophisticated lovers had not. Weeks later Pauline's librarian and confidant Ferrand wrote: 'She does nothing but cry, she doesn't eat, and her health is altered.'"

She remained at Nice throughout 1813 and into 1814, her health continuing to decline, and her anxieties over the future of her brother’s reign mounting. She made efforts to prepare her finances for any potential catastrophe that might befall the family, but evinced no concern for her personal safety. When Napoleon was finally defeated and forced to abdicate in April of 1814, Pauline prepared to join him in exile on the island of Elba--after first going to Naples. She stayed in Naples from June through October, residing in a villa loaned to her during this period by her sister Caroline, the Queen of Naples, and reportedly helping to broker a reconciliation between Napoleon and the Murats, though there is no trace of any correspondence between Napoleon and his brother-in-law from this period. She also worked to quickly sell off her remaining properties in France, rather than risk having them sequestered by the Bourbons. Her final property, Neuilly--formerly belonging to the Murats--was sold to the British government, to serve as the residence of the newly-appointed ambassador to the court of Louis XVIII, the Duke of Wellington.

Pauline finally joined Napoleon on Elba in November of 1814, the only one of his siblings to do so. Her presence delighted Napoleon, and this delight in turn gave renewed life in the British tabloids to the long-recurring rumors of an affair between Napoleon and Pauline. At any rate, Napoleon soon began to fall into a state of depression, which Pauline worked to cure by arranging various balls and other entertainments to keep him occupied. She apparently attempted to coax multiple generals into affairs on Elba, and was turned down repeatedly, and Napoleon’s Mameluke servant Ali was highly critical of her conduct. Displeased with Napoleon’s plans to escape the island and return to France, she confided to Marchand both a diamond necklace for Napoleon to sell if he needed money, and her fear that she would never see her brother again. She was proven correct.

When it became known that the Allies intended to exile Napoleon to Saint Helena after his defeat at Waterloo, Pauline wrote to the Pope to request asylum in Rome. It was granted (partly on account of her brother Louis, now residing there himself, arguing on her behalf) and she made the journey in October. Like the rest of the Bonaparte siblings, she would remain, until the death of Napoleon, under heavy surveillance by multiple governments. The further intervention of the Pope ended a dispute between Camillo and Pauline which enabled Pauline to return to the Palazzo Borghese. Pauline received many British visitors here while Napoleon was on Saint Helena, and tried to charm as many influential Whigs as she could, knowing that they were sympathetic to Napoleon’s situation. As the years passed, reports of Napoleon's deteriorating health caused Pauline great anxiety, affecting her own health in turn. Visitors described her as "much altered" and "grown thin." The Canova statue--and its obvious contrast with her own now diminished figure--suddenly brought about in her a marked insecurity, to the point where Pauline eventually asked Camillo not to show it off to visitors anymore, using the absurd excuse that "the nudity of the statue approaches indecency."

News of Napoleon's death in 1821 left Pauline both heartbroken and outraged. As she had following the death of Dermide, she lashed out for a scapegoat, finding it this time in the English people as a whole. “I have made a vow to receive no more of the English. Without exception they are all butchers." To Hortense she wrote, "I cannot accustom myself to the idea that I will never see him again. I am in despair. Adieu. For me life has no more charm, all is finished."

She fell deathly ill in Rome in late 1823, but recovered enough to continue to charm visitors and dance at soirees again the following year. Another reconciliation was affected with Camillo (this one also via the Pope), and Pauline moved back into the Palazzo Borghese--this time for good--in 1824. Surprisingly, their relationship seemed at last to be taking a genuinely positive turn, even inspiring a local poet “to write an ode on the subject of their matrimonial felicity."

In the spring 1825, Pauline's health began to fail for the final time. She suffered greatly--her bedchamber woman writing later that Pauline had been in pain for over eighty days. Her last letter was written to her brother Louis in Rome on 13 May 1825. "I do nothing but vomit and suffer, I am reduced to a shadow. They are repairing the street and I can't stand the awful noise. The Prince is going to take a villa in the suburbs here where we shall spend the month of May. It is impossible in the state in which I am to think of going to the villa in Lucca.... Embrace Mamma and I send a thousand good wishes to the family. I am ill, ill, but I embrace you." She also confirmed herself as a devout Catholic. "I die without any feelings of hatred or animosity against anyone, in the principles of the faith and doctrine of the apostolic church, and in piety and resignation." She died on 9 June 1825; a stomach tumor was attributed as her cause of death, as it had been for her father.

“Her greatest quality,” writes Margery Weiner, “was hidden except from those who knew her best; lovable herself, she was capable of the greatest devotion.... Not as Queen of Hearts, not as a woman given over to frivolity, narcissism and promiscuity should Pauline Bonaparte be remembered, but as a perfect example of a devoted and loving sister.”

***

Sources:

Broers, Michael. Napoleon: Soldier of Destiny. 2014.

Broers, Michael. Napoleon: The Spirit of the Age, 1805-1810. 2018.

De Beauharnais, Hortense. The Memoirs of Queen Hortense, Vol I (ebook, 2016)

Fraser, Flora. Venus of Empire: The Life of Pauline Bonaparte, 2009.

Roberts, Andrews. Napoleon: A Life. 2014.

Stryienski, Casimir (ed.), Memoirs of Countess Potocka, 1900.

Weiner, Margery. The Parvenue Princesses: Elisa, Pauline, and Caroline Bonaparte. 1964.

#Meet the Bonapartes#Pauline Bonaparte#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Joachim Murat#Jules de Canouville#Camillo Borghese#Louis Bonaparte#history#19th century

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Augustin Pajou - Portrait of the Artist's Family - ca 1802

oil on canvas, 63 x 52 cm, Musée du Louvre

Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou (27 August 1766, Paris - 28 November 1828, Paris) was a French painter in the Classical style.

His father was the sculptor, Augustin Pajou. Nothing is known of his childhood. In 1784, at the age of eighteen, he became a student at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Four attempts to win the Prix de Rome were unsuccessful.

In 1792, he became a member of the Compagnie des arts de Paris, organized by the Louvre, alongside the painter Louis-François Lejeune as well as the future economist, Jean-Baptiste Say. While stationed with the regular army in Sedan, he wrote numerous letters to his friend, François Gérard. which express his initial enthusiasm, but gradually turn to boredom, disillusionment and physical exhaustion.

After being demobilized, he participated in creating the "Commune générale des arts", an institution designed to replace the Académie Royale. He served as Secretary for the Commune's President, Joseph-Marie Vien. In 1795, he married Marie-Marguerite Thibault (1764-1827). Under the First Empire, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of Maréchal Louis-Alexandre Berthier, which may still be seen at Versailles. In 1812, he was awarded a gold medal for his depiction of Napoleon offering clemency to the Royalists who had taken refuge in Spain.

In 1811, at the urging of François-Guillaume Ménageot, who had become apprised of the precarious financial situation facing the sculptor David d'Angers, Pajou wrote a letter to the mayor of Angers, demanding that material aid be given to the sculptor. The aid was granted and was considered a lifesaver for d'Angers, who went on to win the Prix de Rome for sculpture and spend several years at the French Academy in Rome. In 1814, he painted three tableaux celebrating the Bourbon Restoration. They were displayed at the Salon and it is possible they were seen by Napoleon.

He resigned from most of the associations of which he was a member in 1823, citing poor health. In a letter from that period, he says that he was "cruelly tormented for a year by a continual tremor." He died in 1828 and was interred at the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise.

His son, Augustin-Désiré Pajou also became a well-known painter.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (2/7/20) Antoine-Jean Gros (French, 1771-1835) Napoleon Bonaparte on the Battlefield of Eylau, 1807 (1808) Oil on canvas, 521 x 784 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris

The battle of Eylau (8 February 1807) in Poland, in which the Russian army was defeated by the French during the fourth coalition, was an extremely bloody engagement, resulting in 25,000 dead and wounded. In this picture, the Emperor, advancing towards the right, is mounted on a light bay horse, and surrounded by his staff; the cloak and hat which he wore at Eylau were handed to Gros, who kept them till his death. Napoleon is speaking to a wounded Lithuanian, who is moved by the humanity of the victor, and is credited with saying: 'Caesar has granted me life; I will serve you faithfully, as I have served Alexander.' Opposite Napoleon, on a prancing charger, is Murat, whose epic charges transformed an undecided battle into victory; between Murat and Napoleon can be seen Marshal Berthier, Marshal Bessières and General Caulaincourt; the young Lithuanian soldier who stretches his arms towards Napoleon is supported by Baron Percy, Surgeon-in-Chief to the Grande Armée.

In this work, Gros has entirely forsaken classical composition; he has grouped his figures in masses and put striking close-ups of bleeding corpses in the foreground. Although he had never been far east, he has successfully rendered the melancholy of the great wintry plain, the sky leaden with smoke from the burning village.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#my gifs#sailor moon#ayakashi sisters#koan#berthier#calaveras#petz#sailor moon classic#90s anime#gifset#oldanimeedit#gif#mine

439 notes

·

View notes

Text

books read in 2019

january

1.The Little Mermaid — Hans Christian Andersen (1837) (audio)

2. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button — F. Scott Fitzgerald (1922) (audio)

3. Jungle River — Howard Pease (1938)

4. Lolita — Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

5. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenence — Robert M. Pirsig (1974)

6. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde — Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

7. Crome Yellow — Aldous Huxley (1921)

8. The Story of the Eye — George Bataille (1921)

february

9. The Immoralist — Andre Gide (1902)

10. 1984 — George Orwell (1949) (audio) (2nd time)

11. The Catcher in the Rye — J.D. Salinger (1951) (audio) (2nd time)

12. Animal Farm — George Orwell (1945) (audio) (2nd time)

13. The Woodlanders — Thomas Hardy (1877)

14. Descartes in 90 Minutes — Paul Strathern (1996)

15. Jane Eyre — Charlotte Brontë (1847)

march

16. Discourse on the Method (1637) (in Heffernan) & 16.5 The Search After Truth by the Light of Nature — René Descartes

17. Bilingual “Discourse on the Method” & Essays — Descartes & George Heffernan (1994)

18. Autobiography — John Stuart Mill (1873)

19. Méditations — René Descartes (1641)

20. Discourse on Method and Related Writings — René Descartes (Penguin Classics) incl. le monde et les règles

21. Meno — Plato (385 BC) (audio)

22. Crito — Plato (audio)

23. Poetics — Aristotle (audio)

24. The Apology — Plato (audio)

25. Phaedo — Plato (audio)

26. Five Dialogues — Plato (euthyphro, apology, crito, meno, phaedo) (2nd time except euthyphro)

27. Ion - Plato

28. The Art of Loving — Erich Fromm (1956)

29. On Liberty — J.S. Mill (1859)

april

30. A History of Knowledge — Charles Van Doren (1991)

31. Why I am So Wise — Friedrich Nietzsche (Penguin abridged Ecce Homo) (1908)

32. The Varieties of Religious Experience — William James (1902)

33. Pragmatism — William James (1907)

34. Candide — Voltaire (1759)

35. Short stories by Voltaire — Zadig, Micromegas, The World as it Is, Memnon, Bababec, Scarmentados Travels, Plato’s Dream, Jesuit Berthier, Good Brahman, Jeannot and Colin, An Indian Adventure, Ingenuous, One-Eyed Porter, Memory’s Adventure, Chaplain Goudman (1747-1775)

36. The Great Conversation — Robert M. Hutchins (1952)

may

37. Aeschylus’ Oresteia Trilogy & Prometheus Bound (458 BC) — Laurel Classical Drama (1965)

38. Sophocles’ Antigone, Oedipus the King, Electra, Philoctetes (~400 BC) — Laurel Classical Drama (1965)

39. Euripides’ Medea, Hippolytus, Alcestis, The Bacchae (~430 BC) — Laurel Classical Drama (1965)

40. Mythology — Edith Hamilton (1940)

41. Erewhon — Samuel Butler (1872)

42. The Iliad — Homer (850 BC)

43. The Little Prince — Antoine de Saint Exupery (1943)

44. Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (2nd time), The Suppliants, Seven Against Thebes, The Persians (Penguin Classics)

45. Teaching From the Balance Point — Edward Kreitman (Suzuki guide — 1998)

june

46. Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (2nd time), Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone (2nd time) (Penguin Classics)

47. The Odyssey — Homer (850 BC)

48. The Secret Garden — Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

49. Coraline — Neil Gaiman (2002)

50. The Lost Art of Reading — David Ulin (2010)

51. Sophocles’ Ajax, Electra (2nd time), Women of Trachis, Philoctetes (2nd time) (Penguin Classics)

52. The House of the Seven Gables — Nathaniel Hawthorne (1851)

53. The Awakening — Kate Chopin (1899) (audio)

54. Straight is the Gate — André Gide (1924)

55. Wuthering Heights — Emily Brontë (1847)

56. Journey to the Center of the Earth — Jules Verne (1864) (audio)

57. East of Eden — John Steinbeck (1952)

58. Sons and Lovers — D.H. Lawrence (1913)

59. Grapes of Wrath — John Steinbeck (1939) (audio)

july

60. Attached — Amir Levine (2010) (audio)

61. The Prophet — Khalil Gibran (1923) (audio)

62. The Four Agreements — Don Miguel Ruiz (1997) (audio) (2nd time)

63. The Transparent Self — Sidney Jourard (1964)

64. The Return of the Native — Thomas Hardy (1878)

65. The Souls of Black Folk — W.E.B Du Bois (1903) (audio)

66. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) (audio)

67. The Call of the Wild — Jack London (1903) (audio)

68. The Importance of Being Earnest — Oscar Wilde (1895) (audio) (2nd time)

69. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz — L. Frank Baum (1900) (audio)

70. The Picture of Dorian Gray — Oscar Wilde (1890) (audio)

71. Justine — Marquis de Sade (1791)

72. Love and Will — Rollo May (1969)

73. Nine Stories — J.D. Salinger (1953)

74. The Psychology of Man’s Possible Evolution — P.D. Ouspensky (1950)

75. The Good Earth — Pearl S. Buck (1931) (audio)

76. The Symposium — Plato (385-370 BC)

77. Children’s Stories by Oscar Wilde (1888)

august

78. Plato’s Apology (3rd time), Crito (3rd time) ; Laches, Gorgias (audio)

79. Plato’s Greater Hippias, Phaedrus (audio)

80. The Scarlet Letter — Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850) (audio)

81. Plato’s Phaedo (3rd time), Euthyphro (3rd time); Charmides

82. Eyeless in Gaza — Aldous Huxley (1936)

83. A Little History of the World — E. F. Gombrich (1936) (audio)

84. Waiting for Godot — Samuel Beckett (1953)

85. Anna Karenina — Leo Tolstoy (1877)

86. A Little History of Literature — John Southerland (2013)

87. Sartor Resartus — Thomas Carlyle (1831)

88. Macbeth — Shakespeare (1606)

september

89. An Apology for Idlers — Robert Louis Stevenson (Penguin Great Ideas collection of essays) (1877)

90. The Cloister and the Hearth — Charles Reade (1861)

91. How to Read a Book — Mortimer Adler & Charles van Doren (1972) (audio)

92. Robinson Crusoe — Daniel Defoe (1719) (audio)

93. The Story of Art — E. H. Gombrich (1950)