#beatus of liébana

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

mappa mundi

from the "rylands beatus", a copy of beatus of liébana's 8th c. commentary on the apocalypse of st john, spain, late 12th or early 13th c.

source: Manchester, John Rylands Library, Latin MS 8, fol. 43v-44r

#12th century#13th century#mappa mundi#maps#rylands beatus#beatus of liébana#apocalypse#adam and eve#medieval maps#medieval art

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Manuscript Monday!

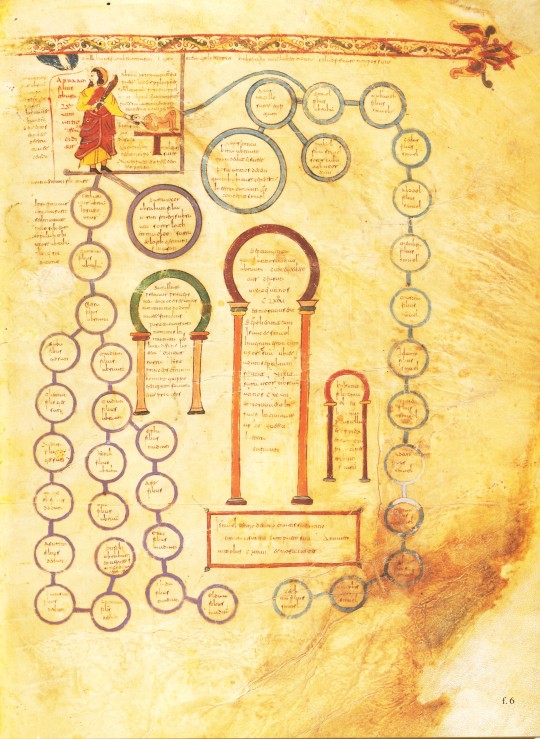

In this series we will periodically focus on selections from our manuscript facsimile collection. Today we present selections from the Morgan Beatus Manuscript, reproduced as A Spanish Apocalypse, The Morgan Beatus Manuscript in New York by George Braziller, Inc. in association with the Pierpont Morgan Library in 1991. The original manuscript, made around 10th century CE at the scriptorium of San Miguel de Escalada in Spain by a monk named Maius, is the earliest surviving illuminated version of the monk Beatus of Liébana's commentary on the biblical Book of Apocalypse (also known as the Book of Revelation). The text of the Book of Revelation makes up the first part of the manuscript, and Beatus’s commentary comprises the second part. The Book of Revelation tells of the end-times in Christianity, during the final judgement of humanity by God. The story within this Biblical book was also seen by those living during the Latin medieval era as representative of the beginning of something new: God’s celestial kingdom. Due to this view of the book, many artists incorporated imagery from this part of the Bible in their work.

Produced in Al-Andalus, or Muslim-ruled Spain, the artistic style of this work combines both Muslim and Christian visual traditions to create a beautifully illuminated manuscript that supplements the commentary by the monk. This artistic style is known as the Mozarabic, which comes from the Arabic mustaʿrib, meaning ‘Arabicized’. Interestingly, this style of art can only be seen in Christian religious art and architecture from Spain at the time, as non-religious artistic objects made by Christians look so similar to Islamic versions of the same works that they cannot be identified as intentionally Christian. Some key Islamic artistic elements within the manuscript include buildings with horseshoe arches, intricate geometric and vegetal patterns as borders for larger images, and the large, bulging eyes of the illustrated animals.

Another interesting aspect of this specific manuscript is the colophon at the end of the manuscript. It tells readers about the circumstances surrounding the creation of this book, including the maker, the patron, the year it was made, and an explanation about why Maius created the manuscript ("I write this . . . at the command of Abbot Victor, out of love for the book of the vision of John the beloved disciple. As part of its adornment I have painted a series of pictures . . . so that the wise may fear the coming of the future judgement of the world's end."). Colophons in medieval manuscripts are not usually as detailed, so the inclusion of all this information contributes greatly to the knowledge and history surrounding the Morgan Beatus Manuscript.

View more Manuscript Monday posts.

– Sarah S., Special Collections Graduate Intern

#manuscript monday#manuscripts#morgan library#morgan beatus manuscript#Beatus of Liébana#Spain#Christian art#Mozarabic#Islamic art style#facsimilies#Spanish art#Medieval art#Spanish medieval art#A Spanish Apocalypse#George Braziller#illuminated manuscripts#Sarah S.

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beatus of Liébana (Spanish: Beato; c. 750 – c. 800) was a monk, theologian, and author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse, an influential compendium of previous authorities' views on the Apocalypse. For him, the observation and reading of such works was a sacred action, akin to communion. Beatus treats the reading of the book as the same as the body, and so by reading the book, the reader is one with Christ.[2] He also led the opposition against a Spanish variant of Adoptionism, the heretical belief that Christ was the son of God by adoption, an idea first propounded in Spain by Elipandus, the bishop of Toledo.

Aside from his work, almost nothing is known about Beatus. He was a monk and probably an abbot at the monastery of Santo Toribio de Liébana in the Kingdom of Asturias, the only region of Spain remaining outside of Muslim control. Beatus appears to have been well known by his contemporaries. He was a correspondent with the notable Christian scholar, Alcuin, and a confidant of queen Adosinda, daughter of Alfonso I of Asturias and wife of Silo of Asturias.[3][4] A supposed biography, the Life of Beatus, has been identified as a 17th-century fraud with no historical value.[3][5]

False Prophet (Revelation 16:13)

Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the ‘Beatus of Saint-Sever’), Saint-Sever before 1072

BnF, Latin 8878, fol. 184v

#studyblr#history#christianity#catholicism#adoptionism#art#medieval art#kingdom of asturias#spain#beatus of liébana#elipandus#alcuin#adosinda#commentary on the apocalypse

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vues sur l'Apocalypse

2361. Beatus de Saint-Sever, (Charlotte Denoël) ((Charlotte Denoël), Beatus de Saint-Sever, ~1060) (Bibliothèque nationale, Citadelles et Mazenod,2022)

⌘ BnF ⌘ Beatus Wiki

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

bird painted on ostracon - Thebes, Egypt - c.1479–1458 BCE

Paul Manship - Crowned Crane - gilt bronze on lapis lazuli base - 13 5⁄8 x 7 x 2 7⁄8 inches - 1932

bird & snake - illumination - Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the ‘Beatus of Saint-Sever’) - Saint-Sever - before 1072

Ron Mueck (Australian, b.1958) Still Life - mixed media sculpture - 2009

Horus the Golden - Horus standing on the hieroglyph for gold - faience and polychrome inlay - Middle Egypt - Hermopolis - Late Period or Ptolemaic Period - 4th century BCE

Utagawa Hiroshige I (Japanese, 1797- 1858)- Jūmantsubo Plain at Fukagawa Susaki - woodblock print - 1856

Adam Binder (British, b.1970) - Wren II - patinated bronze - 2012

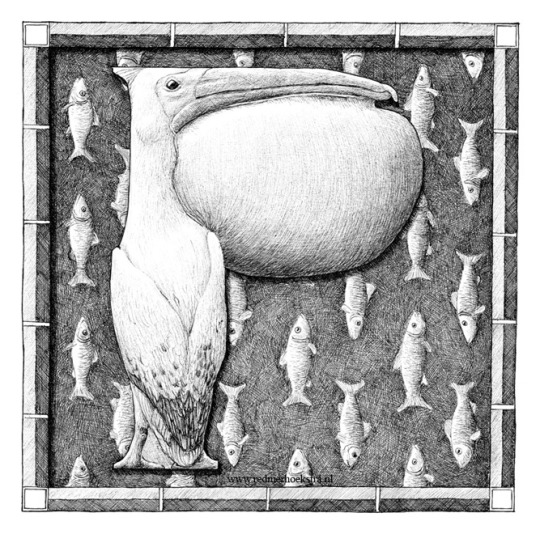

Redmer Hoekstra (Dutch, b.1982) - Pelikaan (Pelican) - pencil - 2015

Bill Mayer (American illustrator, b.1951) - Ibis - painting

Edwin John Alexander (Scottish, 1870-1926) - Griffon (Tawny) vulture (Gyps fulvus) - watercolor & gouache - 26 x 17 cm - Paris - 1891

Eric Fan (born in Hawaii, living & working in Canada) - Kingfisher - painting - 2014

John Boyd (England, b.1957) - Dodo Variations IV - painting

J.K.Brown aka John Kennedy Brown (wooarts) (Welsh, b.1979) - Bird - metal-scrap sculpture

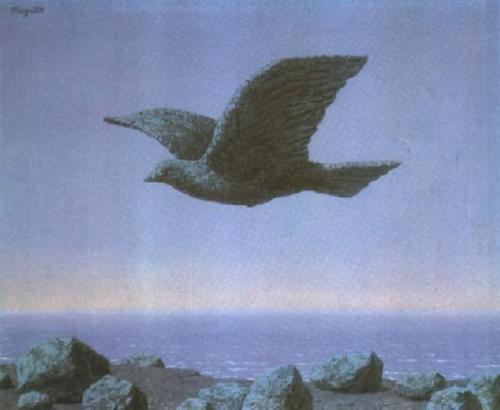

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967) - The Idol - painting - 1965

Michael Sowa (German, b.1945) - Die Rückkehr der Zugvögel (The Return of the Migratory Birds) - painting

Mullanium (steampunktendencies) - Blue Jay - mixed media assemblage

Pelican - painted wood toy

Vojtěch Preissig (Czech, 1873-1944) - Seven Ravens - etching - 1900

Incense container with plovers - lacquer, gold, sea-shell - Japan - late Muromachi period (1392-1573)

Dilhaar (www.instagram.com/hmdbti/) - flying bird - paintings & gif

“Before I ever started painting and before I even started taking drawing seriously, I was in love with the idea of painted animation. Frame by frame, each painting coordinates with the one before and the one after to create life. I still have a lot to learn and there are a lot of technical things I don’t know and will improve on but I like this start. Forget thoughts, focus on actions. Regarding this specific animation I really love the shapes of the shadow on the ground.” - Dilhaar

#art by others#other's artwork#sculpture#painting#birds#print#toy#illumination#gif#Paul Manship#Vojtěch Preissig#Mullanium#Michael Sowa#René Magritte#J.K.Brown#John Boyd#Eric Fan#Edwin John Alexander#Bill Mayer#Redmer Hoekstra#Adam Binder#Utagawa Hiroshige#Ron Mueck#Egypt#Dilhaar @hmdbti

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

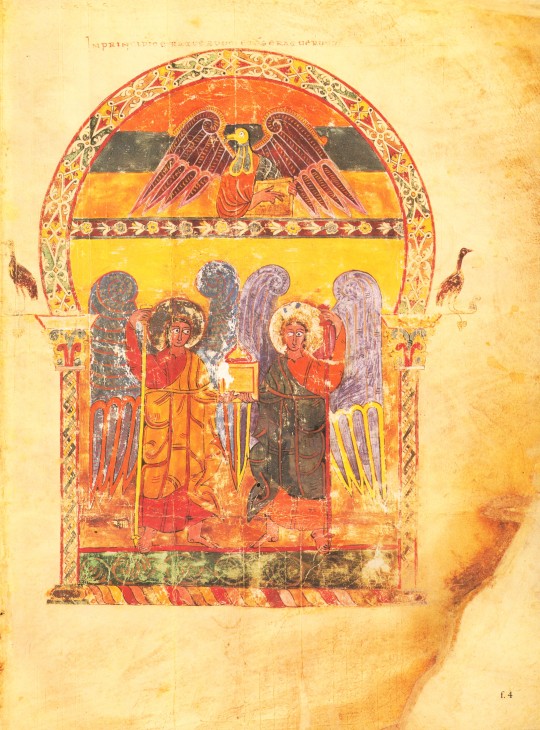

Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Lamb at the Foot of the Cross, Flanked by Two Angels; The Calling of Saint John with the Enthroned Christ flanked by Angels and a Man Holding a Book (Spain, c 1180 CE). Illustrated Beatus manuscripts bring to life an extraordinary vision of the end of the world, as recorded by Saint John in the Apocalypse (Book of Revelation) and filtered through the lens of Beatus of Liébana, an eighth-century Asturian monk. These manuscripts are unique to medieval Spain and a testament to the artistry and intellectual milieu of monastic culture there. The leaf shown here comes from a manuscript that was disassembled in the 1870s. This frontispiece image depicts a lamb (an image commonly associated with Christ) tormented by the spear and sponge used against Christ during the Passion. The alpha and omega symbols hanging from the cross refer to a passage from the Apocalypse: "Ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ, λέγει κύριος, ὁ θεός, ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐρχόμενος, ὁ παντοκράτωρ." (that is: "I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, saith the Lord God, who is, and who was, and who is to come, the Almighty") (Apoc. 1:8)

[Robert Scott Horton]

* * * * *

“To hear is to let the sound wander all the way through the labyrinth of your ear; to listen is to travel the other way to meet it. It’s not passive but active, this listening. It’s as though you retell each story, translate it into the language particular to you, fit it into your cosmology so you can understand and respond, and thereby it becomes part of you. To empathize is to reach out to meet the data that comes through the labyrinths of the senses, to embrace it and incorporate it. To enter into, we say, as though another person’s life was also a place you could travel to.”

― Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby

[via "alive on all channels"]

#Easter#the cross#Lamb#Beatus Manuscript#angels#apocalypse#eighth century#religious art#Rebecca Solnit#quotes#Alive on All Channels#The Faraway Nearby

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaven Faust in the style of Beatus of Liébana (Commentaria in Apocalypsin)

#art history#art challenge#art study#angel art#angel#oc#original character#art style challenge#forget me not county

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

the name of the rose enjoyers: free metropolitan museum of art pdf analyzing and contrasting the beatus of liébana apocalypse manuscripts including an analysis of pigment & production

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow Silence: Miniature from the Silos Apocalypse (ca. 1100)

A yellow field represents "silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” in this miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v)

As the seventh, final seal is opened during the Book of Revelation, unlocking the scroll that John of Patmos envisions in God’s right hand, a silence breaks out in heaven for half an hour. For centuries, artists have avoided depicting this apocalyptic caesura by focusing instead on the action-packed aftermath: thunder and lightning, the seven trumpets, hail and fire mingled with blood. From John Martin’s 1837 mezzotint of cataclysmic crags above turbulent seas back to Albrecht Dürer’s noisy 1511 woodcut of flames engulfing life like tinder, the “silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” is absent, implied only apophatically, as the converse of the chaos that now reigns over, and rains down upon, the earth.

John Martin - The Opening of the Seventh Seal - B1978.43.931 - Yale Center for British Art

This is not the case for a miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v), a codex copy of the Tractatus de Apocalipsin, eighth-century Spanish theologian Beatus of Liébana’s commentary on the Book of Revelation. Here sonic absence is visualized, and it is yellow. Just as silence blankets the ears, in this manuscript, a monochromatic rectangle “serves as an effective screen that blocks the beholder’s gaze”, writes art historian Elina Gertsman. Auditory interruption gets transposed onto the textual plane, as the rectangle veils the ruled lines it floats above. “It’s not that yellow as a color ‘stands for’ silence according to medieval symbolic logic”, argues scholar Vincent Debiais, “it’s that the colored area on the page opens a visual moment, a space of silence within the manuscript itself.” The effect becomes all the more palpable when we consider that the manuscript may have been read aloud.

Untitled Yellow Monochrome, Yves Klein

It can be tempting, despite scholarly reservations, to view this yellow silence as an early precursor to the color field abstractions and monochromatic paintings that preoccupied the mid-twentieth century. Rather than claiming that the Silos Apocalypse prefigures works like Mark Rothko’s Orange and Yellow (1956) or Yves Klein’s “Untitled Yellow Monochrome” (1956), it would be more productive (and interesting) to ask how those modern investigators of the chromosphere approached a type of representation that converged with medieval forms of contemplation. As Debiais writes, “It’s important to challenge the common idea of an almost evolutionary procession, where modernist abstract art is somehow the climax, a new and perfectly original approach to the visual world, absolutely different from all that preceded it.”

A yellow field represents "silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” in this miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

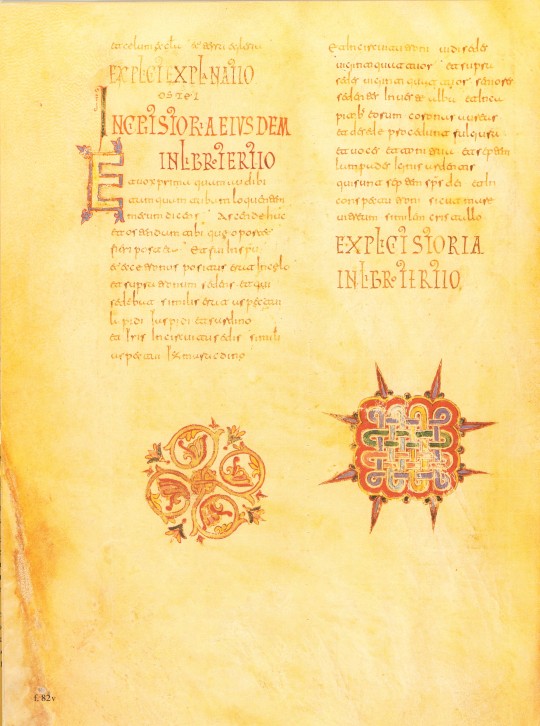

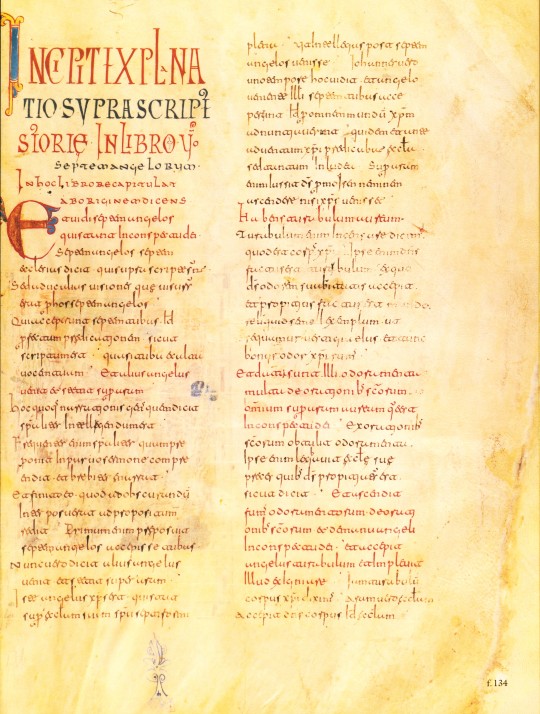

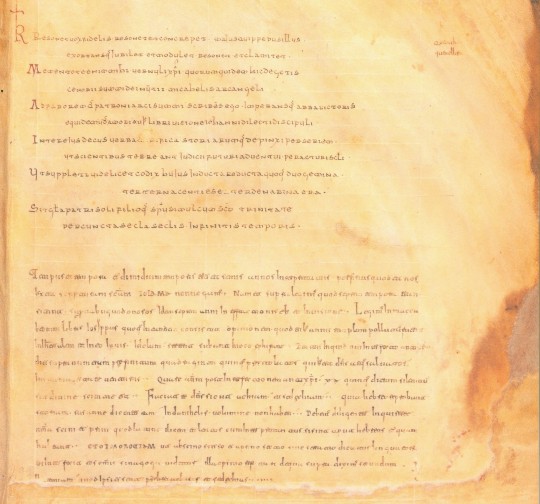

Beatus Super Apocalypsim

The Rylands Beatus , Latin MS.8

From the collection of the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester

A commentary on the Apocalypse of St John, The text was originally written in the eighth century by the Spanish monk and theologian Beatus of Liébana. This copy was created in Spain around the late 12th / early 13th Century

Source

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monopods

Monopods (also called sciapods, skiapods, skiapodes) were mythological dwarf-like creatures with a single, large foot extending from a leg centred in the middle of their bodies. The names monopod and skiapod (σκιάποδες) are both Greek, respectively meaning "one-foot" and "shadow-foot".

Monopods appear in Aristophanes' play The Birds, first performed in 414 BC. They are described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where he reports travelers' stories from encounters or sightings of Monopods in India. Pliny remarks that they are first mentioned by Ctesias in his book Indika, a record of the view of Persians of India which only remains in fragments. Pliny describes Monopods like this:

He [Ctesias] speaks also of another race of men, who are known as Monocoli, who have only one leg, but are able to leap with surprising agility. The same people are also called Sciapodae, because they are in the habit of lying on their backs, during the time of the extreme heat, and protect themselves from the sun by the shade of their feet.

Philostratus mentions Skiapodes in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana, which was cited by Eusebius in his Treatise Against Hierocles. Apollonius of Tyana believes the Skiapodes live in India and Ethiopia, and asks the Indian sage Iarkhas about their existence.

St. Augustine (354–430) mentions the "Skiopodes" in The City of God, Book 16, Chapter 8 entitled "Whether Certain Monstrous Races of Men Are Derived From the Stock of Adam or Noah's Sons", and mentions that it is uncertain whether such creatures exist.

Reference to the legend continued into the Middle Ages, for example with Isidore of Seville in his Etymologiae, where he writes:

The race of Sciopodes are said to live in Ethiopia; they have only one leg, and are wonderfully speedy. The Greeks call them σκιαπόδες ("shade-footed ones") because when it is hot they lie on their backs on the ground and are shaded by the great size of their foot.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi, drawn c. 1300, shows a sciapod on one side of the world, as does a world map drawn by Beatus of Liébana (c. 730 – c. 800).

A race of the "One-Legged",or the "Uniped" was allegedly encountered by Thorfinn Karlsefni and his group of Icelandic settlers in North America in the early 11th century, according to the Saga of Erik the Red. The presence of "unipedes maritimi" in Greenland was marked on Claudius Clavus's map dated 1427.

According to the saga, Karlsefni Thorvald Eiriksson and others assembled a search party for Thorhall, and sailed around Kjalarnes and then south. After sailing for a long time, while moored on the south side of a west-flowing river, they were shot at by a one-footed man (einfœtingr), and Thorvald died from an arrow wound.

The saga goes on to relate that the party went northward and approached what they guessed to be Einfœtingaland ("Land of the One-Legged" or "Country of the Unipeds").

According to Carl A. P. Ruck, the Monopods's cited existence in India refers to the Vedic Aja Ekapad ("Not-born Single-foot"), an epithet for Soma. Since Soma is a botanical deity the single foot would represent the stem of an entheogenic plant or fungus.

John of Marignolli (1338–1353) provides another explanation of these creatures. Quote from his travels from India:

The truth is that no such people do exist as nations, though there may be an individual monster here and there. Nor is there any people at all such as has been invented, who have but one foot which they use to shade themselves withal. But as all the Indians commonly go naked, they are in the habit of carrying a thing like a little tent-roof on a cane handle, which they open out at will as a protection against sun or rain. This they call a chatyr; I brought one to Florence with me. And this it is which the poets have converted into a foot.

—

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a bird killing a serpent as an allegory for christ destroying satan

in the "rylands beautus" (beatus of liébana's commentary on the apocalypse of st john), latin illuminated manuscript, spain, late 12th or early 13th c.

source: Manchester, John Rylands University Library, Latin MS 8, fol. 14r

#medieval art#12th century#13th century#rylands beautus#beatus of liébana#bird#serpent#satan#medieval illumination#illuminated manuscript#christian iconography

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

The flaming apocalypse

Saint Beatus of Liébana, Archangel Michael battles the red dragon, Commentary on the Apocalypse, Beatus of Santo Domingo de Silos, 1091-1109, British Library

#art history#art history memes#dad jokes#punny#puns#punsarelikeonions#art meme#museum nerd#medieval art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monastery of San Toribio de Liébana - en Cantabria / Here lived the Blessed, author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse (8th century).

These commentaries were copied and enlarged with illustrations. There are 31 Beatus / Beatus of Ferdinand I and Sancha or Beatus of Facundo (name of the copyist).

Umberto Eco, said that: "is the greatest iconographic event in the history of mankind".

0 notes

Text

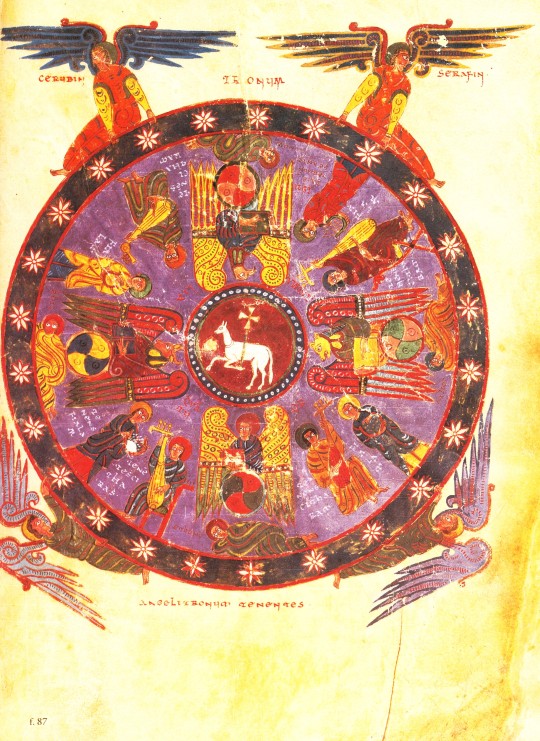

Christ in majesty surrounded by the Tetramorph, in a geometric interlock supported by two angels.

Beatus super Apocalypsim (The 'Rylands Beatus') Beatus de Liébana's commentary on the Apocalypse of Saint-John (written in 776 AD, revised around 784, c. 786). This manuscript was produced in Spain in the late 12th or early 13th century. Iconographically linked to the copies in the archives of the Cathedral of Gerona ("The Gerona Beatus", Núm. Inv. 7 (11)) and the National Bibliotheca in Turin ('The Turin Beatus', Sgn. I. II. 1). Date created: late 12th or early 13th century. Manuscript in Latin; Gothic writing by a single scribe. , lighted up on parchment. Format : ff. 254 (iii+249+ii) Leaf height: 454 mm, width: 326. The John Rylands Library. MS 8. Foilio 2r

1 note

·

View note

Text

Here Are 6 Of The World’s Coolest Dragon Myths

Discover How Ancient Tales of Serpents and Monsters Shaped the Dragons we Know Today, From the Biblical Red Dragon to Japan’s Ocean God Ryujin.

— By Cezary Strusiewicz | July 12, 2024

The seven-headed dragon from the Book of Revelation, pictured in this 19th-century fresco, embodies the struggle between good and evil in apocalyptic literature. Here’s how ancient tales of serpents and monstrous beings have shaped the dragons we know today. Photograph By NPL - Dea Picture Library/W. Buss, Bridgeman Images

Dragons appear in almost every culture on Earth. Some researchers suggest that dragons are born from our most primal fears—a terrifying blend of sharp claws, impenetrable scales, and pointy teeth—which were used by early humans to teach each other about the world’s dangers.

These mythical creatures have captivated human imagination for centuries, weaving their way into folklore, literature, and art across continents. But why do these ancient legends still hold such power over us today? Here are six epic legends that show why dragons continue to ignite our imagination.

Ngwhi—The Original Dragon of Mythology

Ngwhi, a serpent-like deity in various mythologies, inspired concepts like Valhalla and the Midgard Serpent, seen in this 16th-century painting. Photograph By ArniI Magnusson Institute, Bridgeman Images

Ngwhi—or “*H₂n̥gʷʰ in Proto-Indo-European—could be considered the original dragon. Dating back 4,000 to 6,000 years, PIE myths describe Ngwhi (“serpent”) as a three-headed beast that abducts cattle or, in some tales, women. This could be the origin of the familiar pop-culture trope of dragons kidnapping princesses. Ultimately, the multi-headed monster is defeated by a hero empowered by an intoxicating drink and assisted by a sky god.

Today, traces of this story can be found everywhere, from the Norse myth of the thunder god Thor capturing the giant serpent Jörmungandr using an ox head as bait to the Japanese tale of the storm god Susanoo slaying the eight-headed serpent-dragon Yamata-no-Orochi, which devoured young girls, after first getting it drunk on sake.

The Beast—The Most Powerful Representation of Evil

The Beatus of León, an 11th-century illuminated manuscript of Beatus of Liébana's Commentary on the Apocalypse, features stunning illustrations, including the iconic red dragon. Photograph By Pictures From History, Bridgeman Images

One of the most renowned dragons appears in the Book of Revelations. This “enormous red dragon” with seven heads and 10 horns brings about the Apocalypse. Stories of saints like St. George slaying dragons reinforced the idea of dragons as enemies of the righteous.

However, according to Jess Nevins, research librarian and author of Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana, “the roots of Western dragon mythology lie in ancient Mesopotamia.” These early dragon myths were likely influenced by the presence of dangerous wildlife, such as venomous snakes, which posed a real threat to ancient peoples, says Nevins.

Ancalagon The Black—The World’s Largest Dragon

Smaug, known as Smaug the Magnificent, is one of the last great dragons of Middle-earth and the primary antagonist in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit.” Fans estimate his size to be about 60 feet long, roughly the length of a big rig truck. In contrast, the cinematic version of Smaug in Peter Jackson’s film adaptation was significantly larger, 427 feet long, or about the size of two jumbo jets.

But even that version is dwarfed by Ancalagon the Black, described in “The Silmarillion,” as the largest and most powerful dragon ever to exist in Middle-earth. Some interpretations suggest he could have been up to 15 miles long, and his fall caused the destruction of three volcanoes.

Ancalagon was also feared for his fire breath, a classic dragon trope with a fascinating history. “The fiery breath of dragons was an innovation of The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle,” says Nevins. The fictional accounts of Alexander the Great’s adventures mention giant serpents with breath “like a burning torch.”

Ryujin—Supreme Dragon God of The Oceans

This 19th-century print shows Princess Tamatori, a pearl diver, being chased by Ryujin, the Japanese sea dragon. Photograph By Pictures From History, Bridgeman Images

One of the most powerful deities in Japanese mythology is Ryujin, the fearsome dragon god of the oceans, known for his ability to control storms and all sea life. Ryujin’s influence extends to various fictional characters and settings, notably inspiring the underwater Dragon Palace featured in the popular anime series “One Piece.”

Ryujin is a rare example of a Japanese dragon associated with fire, suggesting that his design elements may have influenced the iconic creature Godzilla.

Additionally, Ryujin is considered an ancestral figure of the Japanese Imperial Family, which traces its lineage back to Emperor Jimmu (711 – 585 B.C.), the legendary first ruler of Japan and a great-grandson of Ryujin.

Qijianglong—The Most Dragon-Like Dinosaur

The discovery of dinosaur bones, particularly in China, likely influenced the development of dragon myths. China is rich in fossils of mamenchisaurids, dinosaurs known for their incredibly long necks.

A notable example is the Qijianglong, or “dragon of Qijiang,” discovered in 2006. It had a 50-foot-long body, much of which was dedicated to supporting its massive head. Its neck vertebrae were filled with air, making them lightweight and potentially leading to detachment after death.

Ancient Chinese people may have encountered these enormous bones and envisioned the long, serpentine dragons characteristic of Asian mythology, contrasting with the bulkier dragons in Western folklore.

Apep—The Archetype of Ancient Dragons

Apep, also known as Apophis, was a god in ancient Egyptian religion, represented as a serpent or dragon. He embodied darkness and disorder, opposing the forces of order and light, personified by the goddess Ma'at and the sun god Ra. Apep, also known as Apophis, was a god in ancient Egyptian religion, represented as a serpent or dragon. He embodied darkness and disorder, opposing the forces of order and light, personified by the goddess Ma'at and the sun god Ra. Photograph By Pictures From History, Bridgeman Images

“Dragons...were more often associated with the gods,” says Nevins. In Ancient Egypt, the deity Apep embodies the archetype of a dragon, perhaps one of the most formidable in mythology.

Known also as Apophis, this colossal serpent represents an archetype of ancient dragons and demons, existing since the dawn of time. Apep, the “Lord of Chaos,” engages in an eternal struggle against Ra, the solar deity, in a relentless bid to cast the world into perpetual darkness.

Despite its repeated defeat, Apep never succumbs, returning daily with its hypnotic gaze, orchestrating earthquakes and thunderstorms to maintain its sinister dominion, all in pursuit of extinguishing the very source of light—the Sun itself.

#Mythology#Legends#Prehistoric Creatures#Ngwhi#The Beast#Ancalagon The Black#Ryujin#Qijianglong#Apep#World’s Coolest | Dragon Myths#Ancient Tales#Serpents | Monsters 👹#Biblical Red Dragon#Japan’s Ocean God Ryujin

1 note

·

View note