#Beatus de Liébana

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vues sur l'Apocalypse

2361. Beatus de Saint-Sever, (Charlotte Denoël) ((Charlotte Denoël), Beatus de Saint-Sever, ~1060) (Bibliothèque nationale, Citadelles et Mazenod,2022)

⌘ BnF ⌘ Beatus Wiki

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Manuscript Monday!

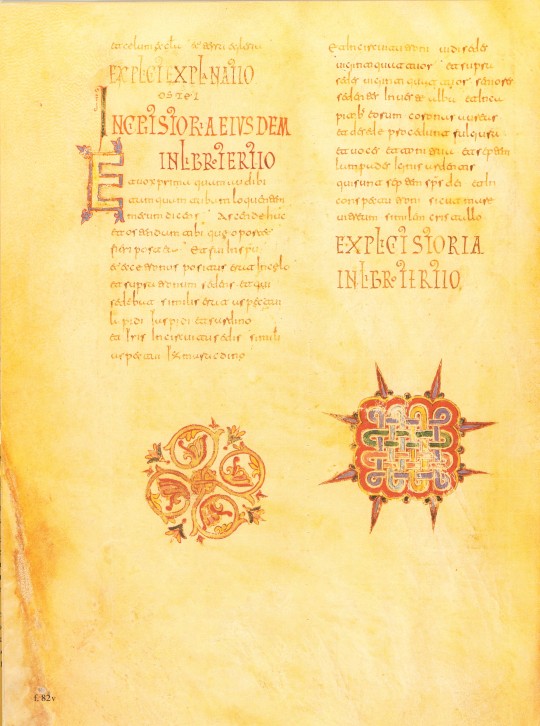

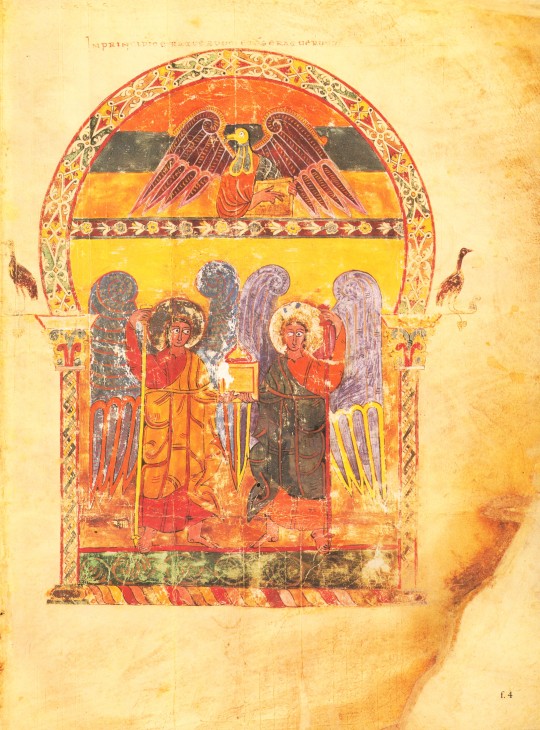

In this series we will periodically focus on selections from our manuscript facsimile collection. Today we present selections from the Morgan Beatus Manuscript, reproduced as A Spanish Apocalypse, The Morgan Beatus Manuscript in New York by George Braziller, Inc. in association with the Pierpont Morgan Library in 1991. The original manuscript, made around 10th century CE at the scriptorium of San Miguel de Escalada in Spain by a monk named Maius, is the earliest surviving illuminated version of the monk Beatus of Liébana's commentary on the biblical Book of Apocalypse (also known as the Book of Revelation). The text of the Book of Revelation makes up the first part of the manuscript, and Beatus’s commentary comprises the second part. The Book of Revelation tells of the end-times in Christianity, during the final judgement of humanity by God. The story within this Biblical book was also seen by those living during the Latin medieval era as representative of the beginning of something new: God’s celestial kingdom. Due to this view of the book, many artists incorporated imagery from this part of the Bible in their work.

Produced in Al-Andalus, or Muslim-ruled Spain, the artistic style of this work combines both Muslim and Christian visual traditions to create a beautifully illuminated manuscript that supplements the commentary by the monk. This artistic style is known as the Mozarabic, which comes from the Arabic mustaʿrib, meaning ‘Arabicized’. Interestingly, this style of art can only be seen in Christian religious art and architecture from Spain at the time, as non-religious artistic objects made by Christians look so similar to Islamic versions of the same works that they cannot be identified as intentionally Christian. Some key Islamic artistic elements within the manuscript include buildings with horseshoe arches, intricate geometric and vegetal patterns as borders for larger images, and the large, bulging eyes of the illustrated animals.

Another interesting aspect of this specific manuscript is the colophon at the end of the manuscript. It tells readers about the circumstances surrounding the creation of this book, including the maker, the patron, the year it was made, and an explanation about why Maius created the manuscript ("I write this . . . at the command of Abbot Victor, out of love for the book of the vision of John the beloved disciple. As part of its adornment I have painted a series of pictures . . . so that the wise may fear the coming of the future judgement of the world's end."). Colophons in medieval manuscripts are not usually as detailed, so the inclusion of all this information contributes greatly to the knowledge and history surrounding the Morgan Beatus Manuscript.

View more Manuscript Monday posts.

– Sarah S., Special Collections Graduate Intern

#manuscript monday#manuscripts#morgan library#morgan beatus manuscript#Beatus of Liébana#Spain#Christian art#Mozarabic#Islamic art style#facsimilies#Spanish art#Medieval art#Spanish medieval art#A Spanish Apocalypse#George Braziller#illuminated manuscripts#Sarah S.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow Silence: Miniature from the Silos Apocalypse (ca. 1100)

A yellow field represents "silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” in this miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v)

As the seventh, final seal is opened during the Book of Revelation, unlocking the scroll that John of Patmos envisions in God’s right hand, a silence breaks out in heaven for half an hour. For centuries, artists have avoided depicting this apocalyptic caesura by focusing instead on the action-packed aftermath: thunder and lightning, the seven trumpets, hail and fire mingled with blood. From John Martin’s 1837 mezzotint of cataclysmic crags above turbulent seas back to Albrecht Dürer’s noisy 1511 woodcut of flames engulfing life like tinder, the “silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” is absent, implied only apophatically, as the converse of the chaos that now reigns over, and rains down upon, the earth.

John Martin - The Opening of the Seventh Seal - B1978.43.931 - Yale Center for British Art

This is not the case for a miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v), a codex copy of the Tractatus de Apocalipsin, eighth-century Spanish theologian Beatus of Liébana’s commentary on the Book of Revelation. Here sonic absence is visualized, and it is yellow. Just as silence blankets the ears, in this manuscript, a monochromatic rectangle “serves as an effective screen that blocks the beholder’s gaze”, writes art historian Elina Gertsman. Auditory interruption gets transposed onto the textual plane, as the rectangle veils the ruled lines it floats above. “It’s not that yellow as a color ‘stands for’ silence according to medieval symbolic logic”, argues scholar Vincent Debiais, “it’s that the colored area on the page opens a visual moment, a space of silence within the manuscript itself.” The effect becomes all the more palpable when we consider that the manuscript may have been read aloud.

Untitled Yellow Monochrome, Yves Klein

It can be tempting, despite scholarly reservations, to view this yellow silence as an early precursor to the color field abstractions and monochromatic paintings that preoccupied the mid-twentieth century. Rather than claiming that the Silos Apocalypse prefigures works like Mark Rothko’s Orange and Yellow (1956) or Yves Klein’s “Untitled Yellow Monochrome” (1956), it would be more productive (and interesting) to ask how those modern investigators of the chromosphere approached a type of representation that converged with medieval forms of contemplation. As Debiais writes, “It’s important to challenge the common idea of an almost evolutionary procession, where modernist abstract art is somehow the climax, a new and perfectly original approach to the visual world, absolutely different from all that preceded it.”

A yellow field represents "silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” in this miniature from the twelfth-century Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add MS 11695, fol. 125v)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The flaming apocalypse

Saint Beatus of Liébana, Archangel Michael battles the red dragon, Commentary on the Apocalypse, Beatus of Santo Domingo de Silos, 1091-1109, British Library

#art history#art history memes#dad jokes#punny#puns#punsarelikeonions#art meme#museum nerd#medieval art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beatus of Liébana (Spanish: Beato; c. 750 – c. 800) was a monk, theologian, and author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse, an influential compendium of previous authorities' views on the Apocalypse. For him, the observation and reading of such works was a sacred action, akin to communion. Beatus treats the reading of the book as the same as the body, and so by reading the book, the reader is one with Christ.[2] He also led the opposition against a Spanish variant of Adoptionism, the heretical belief that Christ was the son of God by adoption, an idea first propounded in Spain by Elipandus, the bishop of Toledo.

Aside from his work, almost nothing is known about Beatus. He was a monk and probably an abbot at the monastery of Santo Toribio de Liébana in the Kingdom of Asturias, the only region of Spain remaining outside of Muslim control. Beatus appears to have been well known by his contemporaries. He was a correspondent with the notable Christian scholar, Alcuin, and a confidant of queen Adosinda, daughter of Alfonso I of Asturias and wife of Silo of Asturias.[3][4] A supposed biography, the Life of Beatus, has been identified as a 17th-century fraud with no historical value.[3][5]

False Prophet (Revelation 16:13)

Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the ‘Beatus of Saint-Sever’), Saint-Sever before 1072

BnF, Latin 8878, fol. 184v

#studyblr#history#christianity#catholicism#adoptionism#art#medieval art#kingdom of asturias#spain#beatus of liébana#elipandus#alcuin#adosinda#commentary on the apocalypse

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Monastery of San Toribio de Liébana - en Cantabria / Here lived the Blessed, author of the Commentary on the Apocalypse (8th century).

These commentaries were copied and enlarged with illustrations. There are 31 Beatus / Beatus of Ferdinand I and Sancha or Beatus of Facundo (name of the copyist).

Umberto Eco, said that: "is the greatest iconographic event in the history of mankind".

1 note

·

View note

Text

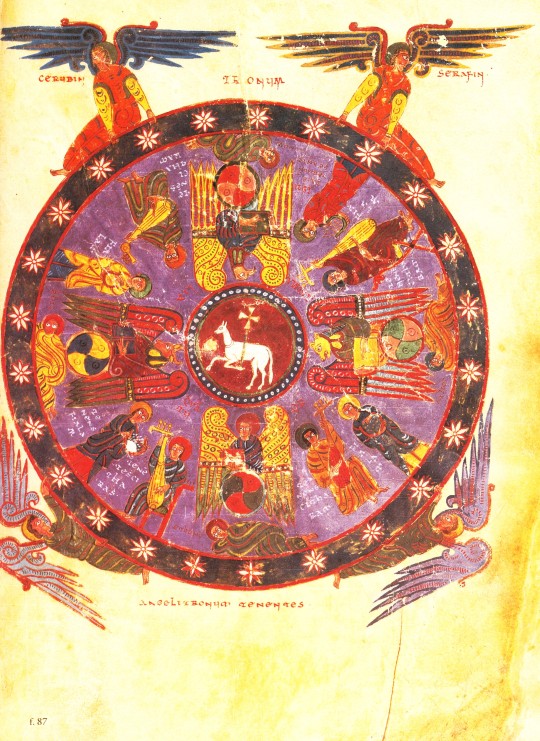

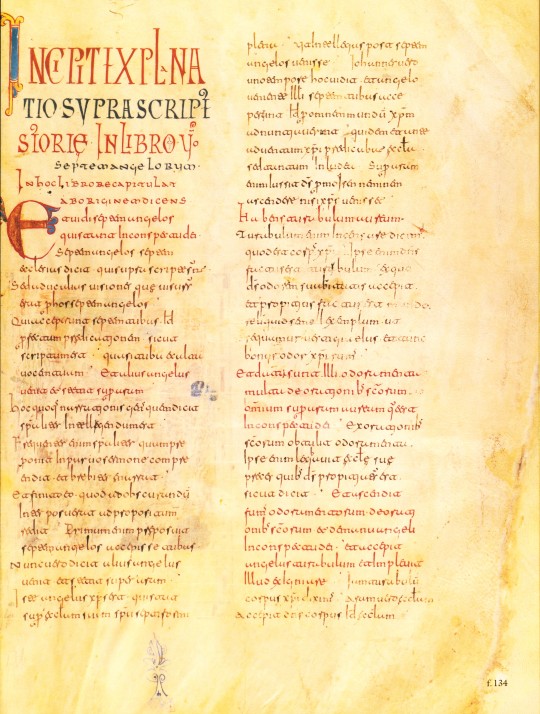

Christ in majesty surrounded by the Tetramorph, in a geometric interlock supported by two angels.

Beatus super Apocalypsim (The 'Rylands Beatus') Beatus de Liébana's commentary on the Apocalypse of Saint-John (written in 776 AD, revised around 784, c. 786). This manuscript was produced in Spain in the late 12th or early 13th century. Iconographically linked to the copies in the archives of the Cathedral of Gerona ("The Gerona Beatus", Núm. Inv. 7 (11)) and the National Bibliotheca in Turin ('The Turin Beatus', Sgn. I. II. 1). Date created: late 12th or early 13th century. Manuscript in Latin; Gothic writing by a single scribe. , lighted up on parchment. Format : ff. 254 (iii+249+ii) Leaf height: 454 mm, width: 326. The John Rylands Library. MS 8. Foilio 2r

1 note

·

View note

Text

Title??

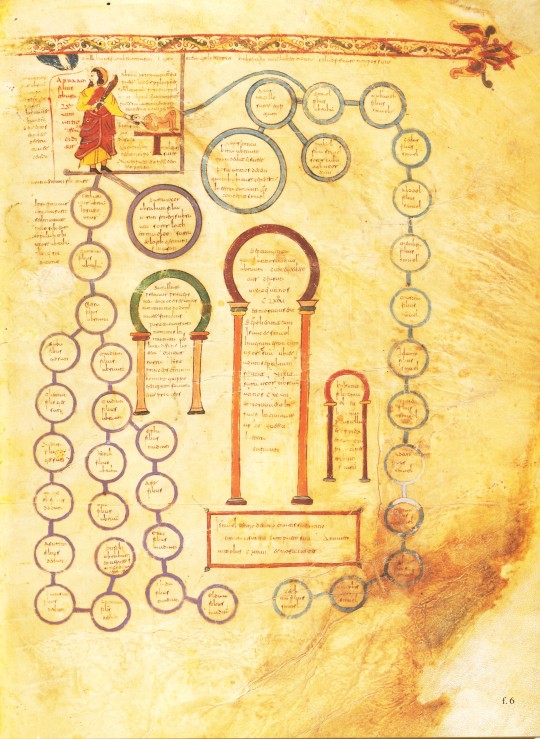

Artist: The Beatus of Facundus, 1047.

Source: The Public Domain Review.

In the 8th century, in a monastery in the mountains of northern Spain, 700 years after the Book of Revelation was written, a monk named Beatus set down to illustrate a collection of writings he had compiled about this most vivid and apocalyptic of the New Testament books. Throughout the next few centuries his depictions of multi-headed beasts, decapitated sinners, and trumpet blowing angels, would be copied over and over again in various versions of the manuscript. [Above] is a selection of images from one such manuscript known as the Beatus de Facundus (or Beatus de León), dating to 1047 and painted by a man called Facundus for Ferdinand I and Queen Sancha [of León ]. It is composed of 312 leaves and 98 miniatures.

John Williams, author of The Illustrated Beatus, explores more in his article for The Public Domain Review, "Beatus of Liébana".

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mapa Mundi de Beatus de Liébana, 780

La terre se présente comme un disque aplati entouré d'océans. La terre est divisée en trois continents : Asie, Afrique, Europe, qui correspondent respectivement aux territoires des descendants des trois fils de Noé : Sem, Cham et Japhet. les masses continentales sont séparées par des cours d'eau ou des mers intérieures comme la Mer Méditerranée, le Nil, le Bosphore. Au centre du monde se situait Jérusalem, la ville sacrée du judaïsme et du christianisme. Cette situation centrale de Jérusalem comme umbiculum mundi (nombril du monde) était usuelle dans la cosmogonie chrétienne médiévale.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers St. Alcuin of York, Deacon and Abbot of Tours.

Ora pro nobis.

Alcuin of York (c. 735 – 19 May 804 AD) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin or Alchoin – was an English scholar, clergyman, poet and teacher from York, Northumbria.

He was born around 735 AD and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s.

Alcuin wrote many theological and dogmatic treatises, as well as a few grammatical works and a number of poems. He was made Abbot of Tours in 796, where he remained until his death. "The most learned man anywhere to be found", according to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (ca. AD 817-833), he is considered among the most important architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

Alcuin was born in Northumbria, presumably sometime in the 730s. Virtually nothing is known of his parents, family background, or origin. In common hagiographical fashion, the Vita Alcuini asserts that Alcuin was 'of noble English stock,' and this statement has usually been accepted by scholars. Alcuin's own work only mentions such collateral kinsmen as Wilgils, father of the missionary saint Willibrord; and Beornrad (also spelled Beornred), abbot of Echternach and bishop of Sens. Willibrord, Alcuin and Beornrad were all related by blood.

In his Life of St Willibrord, Alcuin writes that Wilgils, called a paterfamilias, had founded an oratory and church at the mouth of the Humber, which had fallen into Alcuin's possession by inheritance. Because in early Anglo-Latin writing paterfamilias ("head of a family, householder") usually referred to a ceorl, Donald A. Bullough suggests that Alcuin's family was of cierlisc status: i.e., free but subordinate to a noble lord, and that Alcuin and other members of his family rose to prominence through beneficial connections with the aristocracy. If so, Alcuin's origins may lie in the southern part of what was formerly known as Deira.

The young Alcuin came to the cathedral church of York during the golden age of Archbishop Ecgbert and his brother, the Northumbrian King Eadberht. Ecgbert had been a disciple of the Venerable Bede, who urged him to raise York to an archbishopric. King Eadberht and Archbishop Ecgbert oversaw the re-energising and re-organisation of the English church, with an emphasis on reforming the clergy and on the tradition of learning that Bede had begun. Ecgbert was devoted to Alcuin, who thrived under his tutelage.

The York school was renowned as a centre of learning in the liberal arts, literature, and science, as well as in religious matters. It was from here that Alcuin drew inspiration for the school he would lead at the Frankish court. He revived the school with the trivium and quadrivium disciplines, writing a codex on the trivium, while his student Hraban wrote one on the quadrivium.

Alcuin graduated to become a teacher during the 750s. His ascendancy to the headship of the York school, the ancestor of St Peter's School, began after Aelbert became Archbishop of York in 767. Around the same time Alcuin became a deacon in the church. He was never ordained a priest. Though there is no real evidence that he took monastic vows, he lived as if he had.

In 781, King Elfwald sent Alcuin to Rome to petition the Pope for official confirmation of York's status as an archbishopric and to confirm the election of the new archbishop, Eanbald I. On his way home he met Charlemagne (whom he had met once before), this time in the Italian city of Parma.

Alcuin's intellectual curiosity allowed him to be reluctantly persuaded to join Charlemagne's court. He joined an illustrious group of scholars that Charlemagne had gathered around him, the mainsprings of the Carolingian Renaissance: Peter of Pisa, Paulinus of Aquileia, Rado, and Abbot Fulrad. Alcuin would later write that "the Lord was calling me to the service of King Charles."

Alcuin became Master of the Palace School of Charlemagne in Aachen (Urbs Regale) in 782. It had been founded by the king's ancestors as a place for the education of the royal children (mostly in manners and the ways of the court). However, Charlemagne wanted to include the liberal arts and, most importantly, the study of religion. From 782 to 790, Alcuin taught Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, as well as young men sent to be educated at court, and the young clerics attached to the palace chapel. Bringing with him from York his assistants Pyttel, Sigewulf, and Joseph, Alcuin revolutionised the educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the liberal arts and creating a personalised atmosphere of scholarship and learning, to the extent that the institution came to be known as the 'school of Master Albinus'.

In this role as adviser, he took issue with the emperor's policy of forcing pagans to be baptised on pain of death, arguing, "Faith is a free act of the will, not a forced act. We must appeal to the conscience, not compel it by violence. You can force people to be baptised, but you cannot force them to believe." His arguments seem to have prevailed – Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797.

Charlemagne gathered the best men of every land in his court, and became far more than just the king at the centre. It seems that he made many of these men his closest friends and counsellors. They referred to him as 'David', a reference to the Biblical king David. Alcuin soon found himself on intimate terms with Charlemagne and the other men at court, where pupils and masters were known by affectionate and jesting nicknames. Alcuin himself was known as 'Albinus' or 'Flaccus'. While at Aachen, Alcuin bestowed pet names upon his pupils – derived mainly from Virgil's Eclogues. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "He loved Charlemagne and enjoyed the king's esteem, but his letters reveal that his fear of him was as great as his love.

In 790 Alcuin returned from the court of Charlemagne to England, to which he had remained attached. He dwelt there for some time, but Charlemagne then invited him back to help in the fight against the Adoptionist heresy which was at that time making great progress in Toledo, the old capital of the Visigoths and still a major city for the Christians under Islamic rule in Spain. He is believed to have had contacts with Beatus of Liébana, from the Kingdom of Asturias, who fought against Adoptionism. At the Council of Frankfurt in 794, Alcuin upheld the orthodox doctrine against the views expressed by Felix of Urgel, an heresiarch according to the Catholic Encyclopaedia. Having failed during his stay in Northumbria to influence King Æthelred in the conduct of his reign, Alcuin never returned home.

He was back at Charlemagne's court by at least mid-792, writing a series of letters to Æthelred, to Hygbald, Bishop of Lindisfarne, and to Æthelhard, Archbishop of Canterbury in the succeeding months, dealing with the Viking attack on Lindisfarne in July 793. These letters and Alcuin's poem on the subject, De clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii, provide the only significant contemporary account of these events. In his description of the Viking attack, he wrote: "Never before has such terror appeared in Britain. Behold the church of St Cuthbert, splattered with the blood of God's priests, robbed of its ornaments."

In 796 Alcuin was in his sixties. He hoped to be free from court duties and upon the death of Abbot Itherius of Saint Martin at Tours, Charlemagne put Marmoutier Abbey into Alcuin's care, with the understanding that he should be available if the king ever needed his counsel. There he encouraged the work of the monks on the beautiful Carolingian minuscule script, ancestor of modern Roman typefaces.

Alcuin died on 19 May 804 AD, some ten years before the emperor, and was buried at St. Martin's Church under an epitaph that partly read:

Dust, worms, and ashes now ...

Alcuin my name, wisdom I always loved,

Pray, reader, for my soul.

The majority of details on Alcuin's life come from his letters and poems. There are also autobiographical sections in Alcuin's poem on York and in the Vita Alcuini, a Life written for him at Ferrières in the 820s, possibly based in part on the memories of Sigwulf, one of Alcuin's pupils.

Almighty God, in an age when Western Europe was filled with warfare and cultural disarray, you raised up your deacon Alcuin to rekindle the light of learning: Illumine our minds, we pray, that amid the uncertainties and confusions of our own time we may show forth your eternal truth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

Amen.

#christianity#jesus#god#saints#father troy beecham#troy beecham episcopal#father troy beecham episcopal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

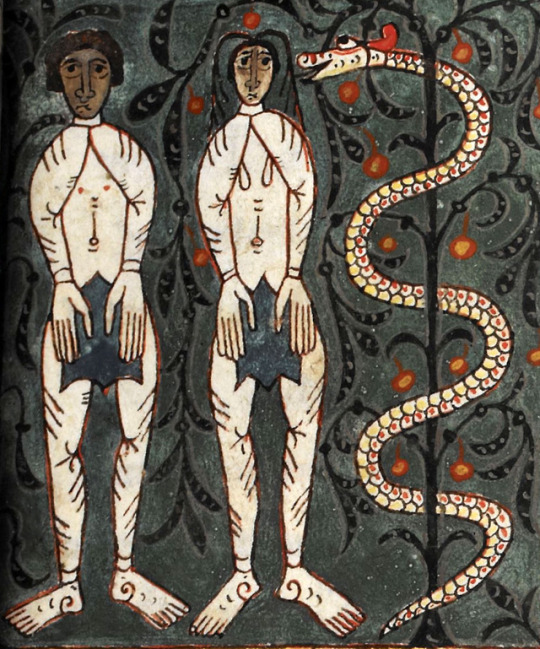

Adam & Eve ashamed after being tricked by the serpent. Mozarabic illumination in the so called Escorial Beatus, a commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus of Liébana. Kingdom of Asturias, circa 950-955. Currently part of the collection of the Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain.

#adam#eve#asturias#escorial#illumination#illuminated manuscript#apocalypse#beatus#liebana#spain#mozarabic#serpent#tree#tree of life

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Beast, the Dragon and the False Prophet

Revelation 16:13 ‘And I saw three unclean spirits like frogs come out of the mouth of the dragon, and out of the mouth of the beast, and out of the mouth of the false prophet’ ('Et vidi de ore draconis, et de ore bestiæ, et de ore pseudoprophetæ spiritus tres immundos in modum ranarum’)

Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the 'Beatus of Saint-Sever’), Saint-Sever before 1072 (BnF, Latin 8878, fol. 184v)

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Before the widely acclaimed ‘Les Demoiselles d'Avignon’ by Pablo Picasso (1907; originally titled ‘The Brothel of Avignon’), there was the amazing collection of the cubist, psychedelic Beatus of Liébana:

The Great Whore gets drunk with one of the Kings of the Earth. From the Facundus Beatus, Commentarium in Apocalypsin. 1047 AD. España. Bibliothèque Infernale on FB

“These miniaturists of the tenth century, who anticipated their millennium, had already practiced the glaze technique. Gauguin, preceded by Matisse in the countercurves, with their fluid contours, invented the realistic expressiveness of Picasso in the Señoritas de Avignon. And in fact, until the arrival of the art of cubist portraits we would not see again things like face and front profile, the animal disproportion of the painter of Guernica, anticipated by these apocalyptic illuminators.” —Jacques Fontaine, The Pre-Romanesque Hispanic Art

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unknown master from the Monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, Burgos Beatus of Liébana: Commentary on the Apocalypse 🇺🇦 c. 1180 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

🇪🇸 #spain 📕 #manuscript

#art#lol#medieval art#caption this#funny art#ugly medieval#classical art meme#Beatus of Liébana#spain#manuscript

0 notes

Photo

Adam, Eve and the Serpent

Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the 'Silos Apocalypse'), Santo Domingo de Silos 1091-1109

BL, Add. 11695, fol. 40r

#apocalypse#Bible#genesis#serpent#11th century#12th century#medieval art#book#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#medieval#art#middle ages

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

@red_loeb: Kiss a fish Sunday! 😉 #SundayMotivation Add MS 11695; 1091-1109; Beatus of Liébana, The 'Silos Apocalypse'; Spain, North (Santo Domingo de Silos); f.24v @BLMedieval https://t.co/74qgYNJ9sP

0 notes