#aššurism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

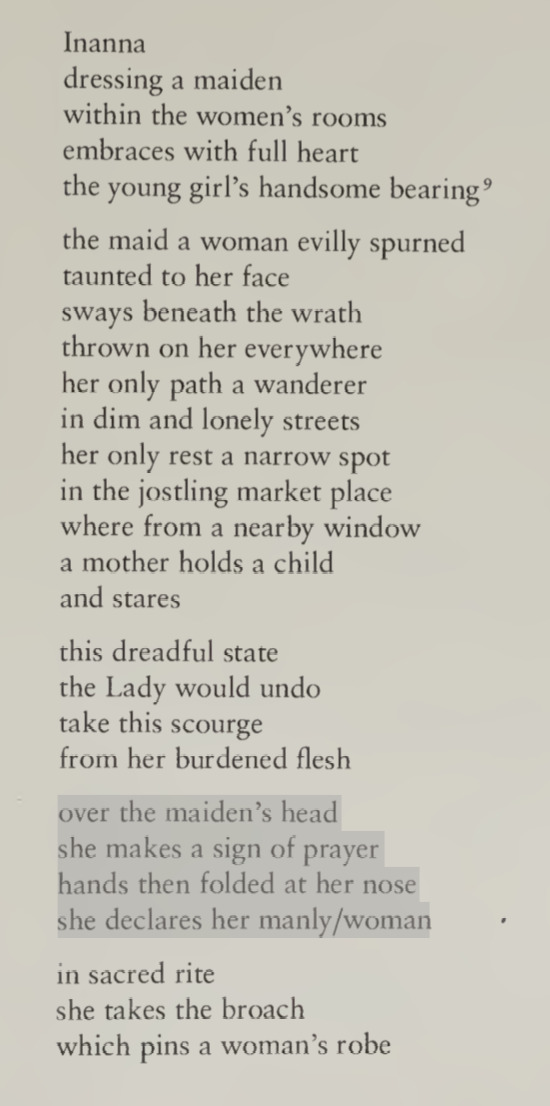

from Lady of the Largest Heart, a poem by High Priestess Enheduanna & translated by Betty De Shong Meador.

#m.#inanna#ishtar#enheduanna#aššurism#mesopotamian polytheism#trans theology#trans paganism#transmasc#transfem

801 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aššur, god of the city of Aššur ⛰️

Aššur iconography can be a little elusive. Some depictions alongside Neo-Assyrian kings show what looks like to me like a winged mountain god with a bow and arrow.

I chose osprey details out of pure vibes. Ospreys are native to the area and it makes sense that, if he’s a bird, he’s probably a bird that enjoys high places (large cliff I mean mountain!) and enjoys a good fish out of the river beside his cliff. Osprey markings look nice, too.

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#assur#aššur#assyrian#assyrian mythology#mesopotamia#mesopotamian mythology#mesopotamian gods#assyrian gods#ashur#when you and your city are named the same thing#which assur are we talking about? the city or the god? maybe it’s both

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great find!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Naqiʾa/Zakūtu

(Relief depicting Naqiʾa and her son Esarhaddon)

"Naqiʾa (c. 730– 668 BCE), wife of Sennacherib (705– 681), mother of the Neo- Assyrian king Esarhaddon (681– 669) and grandmother of Ashurbanipal (668– 627), is the best documented and in all probability most influential royal woman of the Neo- Assyrian period.

It was often suggested that Naqiʾa was the driving force behind Sennarcherib’s installment of Esarhaddon as crown prince. This was a truly exceptional case, as Esarhaddon was one of Sennacherib’s younger sons and most probably, even as a young man, suffered from an illness that would later kill him. Sickness was often interpreted as a sign of divine wrath in Mesopotamia; therefore, it was a severe obstacle for a claimant to the throne and any sickness of the king could be used to question his status as the darling of the gods. Maybe we will never know what the reasons for Esarhaddon’s promotion were, but we are sure about the results of Sennacherib’s decision.

Sennacherib was assassinated by his other sons and Esarhaddon had to fight his brothers in order to be enthroned. While the rebellion was going on, Naqiʾa explored the future of her son by asking for prophetic messages, something that was usually a privilege of the kings. The answer highlights the role of Ishtar, here called the Lady of Arbela, and the privileged position, of Naqiʾa:

I am the Lady of Arbela! To the king’s mother, since you implored me, saying: “The one on the right and the other on the left you have placed in your lap. My own offspring you expelled to roam the steppe!” No, king, fear not! Yours is the kingdom, yours is the power! By the mouth of Aḫat- abiša, a woman from Arbela.

Seemingly, the prophecy was right: it took Esarhaddon only two months to defeat his brothers and he was enthroned as Assyrian king. In this text Naqiʾa is already designated as queen mother; according to Melville this was “the highest rank a woman could achieve.”

In earlier research Naqiʾa was often seen as the strong woman behind a weak, sick, and superstitious king. Newer research has demonstrated that despite all of his problems, Esarhaddon was a capable ruler, who brought the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its maximal extension and pacified Babylonia, at least for a while.

During his reign Naqiʾa became really powerful and commissioned her own building inscription. To undertake large building projects and praise them in inscriptions is typical for kings, but extraordinary for a royal woman. The inscription introduces Naqiʾa in a bombastic tone, which is quite typical for inscriptions commissioned by kings:

I, Naqiʾa … wife of Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria, daughter- in- law of Sargon [II], king of the world, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of the world [and] king of Assyria; the gods Aššur, S.n, Šamaš, Nab., and Marduk, Ištar of Niniveh, [and] Ištar of Arbela … He [Essarhaddon] gave to me as my lordly share the inhabitants of conquered foes plundered by his bow. I made them carry hoe [and] basket and they made bricks. I … a cleared tract of land in the citadel of [the city of] Nineveh, behind the temple of the gods Sîn and Šamaš, for a royal residence of Esarhaddon, my beloved son …

We can clearly see that Naqiʾa held an extraordinarily powerful position during the reign of her son and this continued even after Esarhaddon’s death. She was eager to assure the enthronement of her grandson Assurbanipal. The loyalty treaty that was intended to secure his reign is called the treaty of Zakutu, another name of Naqiʾa. Its first lines read:

The treaty of Zakutu, the queen of Sannacherib, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, with Šamaš- šumu- ukin, his equal brother, with Šamaš- metu- uballiṭ and the rest of his brothers, with the royal seed, with the magnates and the governors, the bearded and the eunuchs, the royal entourage, with the exempts and all who enter the Palace, with Assyrians high and low: Anyone who (is included) in this treaty which Queen Zakutu has concluded with the whole nation concerning her favorite grandson Assurbanipal […]

That Naqiʾa was able to conclude a treaty with the most powerful persons throughout the empire and to establish her favorite grandson on the throne is clear evidence for her powerful position, even if she simply continued the plans she had made earlier with Esarhaddon. It seems that Naqiʾa died shortly after Assurbanipal was enthroned as king."

Fink Sebastian, “Invisible Mesopotamian royal women?”, in: The Routledge companion to women and monarchy in the ancient mediterranean world

#naqi'a#queens#ancient history#ancient world#history#women in history#mesopotamia#neo-assyrian empire#women's history#historical figures#8th century BC#7th century BC#assyria#middle-eastern history

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The destruction of Elam was not the Holocaust, just as the Rwandan Genocide wasn’t the Holocaust or the Cambodian Genocide. The destruction of Elam wasn’t the Rwandan Genocide. The destruction of Elam wasn’t even the Assyrian destruction of Israel a century or so beforehand. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, the anti-Huguenot pogrom that killed between 5,000 and 20,000 people in France in 1572, differed meaningfully from the many anti-Jewish pogroms in the later Russian Empire. The Holocaust wasn’t the same as the Herero and Namaqua Genocide, the mass murder of indigenous people in what is now Namibia by the German Empire between 1904 and 1907, despite the fact that both were carried out by German authorities just a generation apart. Each of those incidents and campaigns of mass violence stands on its own. Their logic was different. They proceeded in different ways, with death tolls ranging from the dozens to the millions. Some were straightforward land grabs in which killing was incidental. Others were ideologically motivated campaigns of murder for which the groundwork had been laid for decades or centuries. Still others were the result of sudden explosions of ethnic or religious hatred against a background of oppression or conflict. But what ties them together, aside from the mass violence, is the fact that utterly ordinary people participated in all of them. It doesn’t take all that much for a baker from Aššur or a truck-driver from Hamburg to turn into a willing enslaver and killer, even a mass murderer who pulled a lethal trigger hundreds of times, under the right circumstances. If those in positions of authority tell them that it’s acceptable or even admirable, if they’re given the tools and the opportunity to do so, then even the most average people can commit horrifying acts.

-Patrick Wyman, Ordinary People Do Terrible Things

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did ancient near east have any equivalent supernatural beings to nymphs

Overall not really, with small exceptions restricted pretty much just to Hittite Anatolia.

Jenniffer Larson in Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore (p. 33) suggests the notion of nymphs - or rather of minor female deities associated specifically with bodies of water and with trees - was probably an idea which originated among early speakers of Indo-European languages. While I often find claims about reconstructed “PIE deities” and whatnot dubious, I think this checks out and explains neatly why despite being a vital feature of Greek local cults nymphs have little in the way of equivalents once we start moving further east.

Mesopotamian religion wasn’t exactly strongly nature-oriented. Overall even objects were more likely to be deified than natural features; for an overview see Gebhard J. Selz’s ‘The Holy Drum, the Spear, and the Harp’. Towards an understanding of the problems of deification in Third Millennium Mesopotamia. It should be pointed out that in upper Mesopotamia mountains were personified quite frequently, but mountain deities (Ebih is by far the most famous) are almost invariably male (Wilfred G. Lambert’s The God Aššur remains a pretty good point of reference for this phenomenon) Rivers are a mixed bag but in Mesopotamia the most relevant river deity was the deified river ordeal (idlurugu referred to both the procedure and the god personifying it), who was also male, and ultimately an example of a judiciary deity rather than deified natural feature. Alhena Gadotti points out that there is basically no parallel to dryads, and supernatural beings were almost never portrayed as residing in trees in Mesopotamia (‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’ and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle, p. 256). You can find tree deities like Lugal-asal (“lord of the poplar”) but there’s a decent chance this reflects originating in an area named after poplars and we aren’t dealing with something akin to a male dryad (also, Lugal-asal specifically fairly consistently appears in available sources first and foremost as a local Nergal-like figure).

All around, it’s safe to say there’s basically no such a thing as a “Mesopotamian nymph”. Including Hurrian evidence won’t help much either - more firmly male deified mountains, at least one distinctly male river, but no minor nature goddesses in sight.

Probably the category of deities most similar to nymphs would be various minor Hittite goddesses representing springs - Volkert Haas in fact referred to them as Quellnymphen (“spring nymphs”). Ian Rutherford (Hittite Texts and Greek Religion: Contact, Interaction, and Comparison, pp. 199-200) points out that the descriptions of statues of deities belonging to this class indicate a degree of iconographic overlap with nymphs in Greek art. Notably, in both cases depictions with attributes such as shells, dishes or jugs are widespread. There’s even a case of possibly cognate names: Hittite Kuwannaniya (from kuwanna, “of lapis lazuli”) and Kuane (“blue”) worshiped in Syracuse. They aren’t necessarily directly related though, since arguably calling a water deity “the blue one” isn’t an idea so specific it couldn’t happen twice.

There is also one more case which is considerably more peculiar - s Bronze Age Anatolian goddess seemingly being reinterpreted as a nymph by Greek authors: it is generally accepted that Malis, a naiad mentioned by Theocrtius, is a derivative of Bronze Age Maliya, who started as a Hittite craftsmanship goddess (she appears in association with carpentry and leatherworking, to be specific). There is pretty extensive literature on her and especially her reception after the Bronze Age, I’ve included pretty much everything I could in the bibliography of her wiki article some time ago. Note that there is no evidence the Greek interpretation of Maliya/Malis as a nymph was accepted by any inhabitants of Anatolia themselves. While most Bronze Age Anatolian deities either disappeared or remained restricted to small areas in the far east of Anatolia in the first millennium BCE, in both Lycia and Lydia there is quite a lot of evidence for the worship of Maliya. In both cases there is direct evidence for local rulers considering her a counterpart of Athena (presumably due to shared civic role and connection to craftsmanship; or maybe they simply aimed to emulate Athens). There’s even at least one instance of Maliya appearing in place of Athena in a depiction of the judgment of Paris (or rather, appearing in the guise of Athena, since the iconography isn’t altered).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

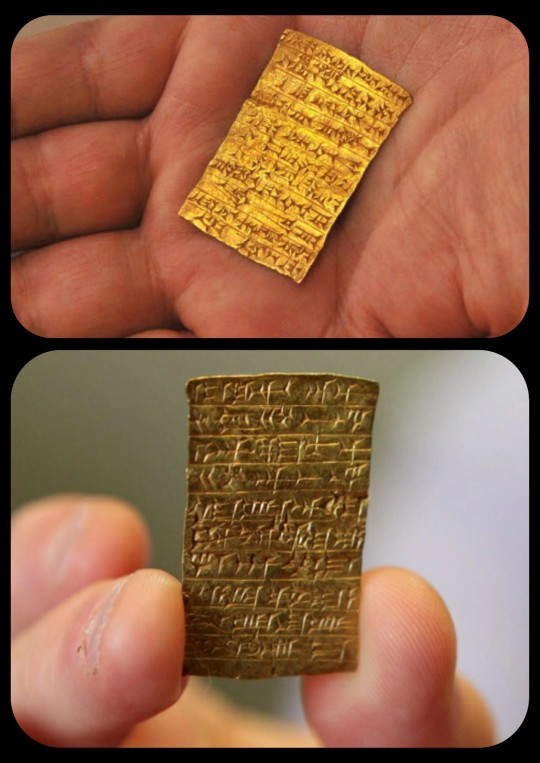

Gold Tablet from the Temple of Ištar in Aššur, Assyria (modern-day Iraq) c.1243-1207 BCE: this tablet was discovered within the foundations of the ancient temple; it measures just over 3cm (1in) in length

The cuneiform inscription honors King Tukulti-Ninurta I, who had ordered the construction of the temple, and describes how the building was constructed. This is just one of the many items that had been buried around the temple with similar inscriptions.

As this article explains:

Most of [the inscriptions installed in the temple] would not have been visible while the temple was still in use, as they were laid into the sanctuary’s foundations or walls. Tukulti-Ninurta commissioned a great number of objects carrying variations of the inscription commemorating his achievement of erecting the new temple.

The practice of depositing inscriptions directed at the gods as well as future generations had become a central element of the temple building process since the Early Dynastic Period, and was employed to immortalize the ruler by eternally associating his name with a monumental building such as the Ištar temple - a process that also transformed a sanctuary into a votive object dedicated to a deity.

It took several hours of searching (i.e. scouring through old artifact catalogs) for me to find a direct translation of the inscription on this particular tablet, and I could basically only find it in a PDF of an old bibliographic manuscript that isn't even in print anymore, but here it is:

Tukulti-Ninurta, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Shalmaneser, king of Assyria: at that time the temple of the goddess Ištar, my mistress, which Ilu-šumma, my forefather, the prince, had previously built — that temple had become dilapidated. I cleared away its debris down to the bottom of the foundation pit. I rebuilt from top to bottom and deposited my monumental inscription. May a later prince restore it and return my inscribed name to its place. Then Aššur will listen to his prayers.

This tablet was stolen from the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin back in 1945, during the chaotic final days of WWII. It was then lost for almost 60 years before it finally re-emerged in 2006, when a Holocaust survivor named Riven Flamenbaum passed away and the tablet was found among his belongings. According to his family, Flamenbaum had gotten the tablet from a Soviet soldier (in exchange for two packs of cigarettes) at the end of the war.

In 2013, following a lengthy legal battle between Riven Flamenbaum's family and the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Germany, a court in New York ordered the family to return the tablet back to the museum.

Sources & More Info:

Albert Kirk Grayson: Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia BC (to 1115 BC) (the translation appears on p.261)

Daniel Luckenbill: Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Volume 1 (PDF download; p.65 contains relevant info)

CTV News: 3,000-year-old Assyrian Gold Tablet Returned to German Museum

#archaeology#history#anthropology#ancient history#assyria#mesopotamia#golden tablet#cuneiform#artifact#ancient iraq#iraq#ancient near east#middle east#ishtar#pagan deities#polytheism#return the slab

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is sooooo funny. oh, you have something mean to say about poor ol' Israel? well what about Aššur-dān II, King of the Universe, who reigned in glory in the first millennium before christ?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashurnasirpal II and the Greatest Party Ever Thrown

By Anthony Huan - https://www.flickr.com/photos/anthonyhuan/44841858665/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91494202

Ashurnasipal II was the third king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, was born in 910 BCE, and reigned from 883-859 BCE. He was particularly know for his cruelty, as well as for building a new capital for Assyria at what is now known as Nimrud in 15 years. For the labor, he used enslaved captives from his campaigns to expand the boundaries of the Assyrian Empire. To maintain control over his empire, he installed Assyrian governors as opposed to allowing localities to just pay tribute which had been the standard practice before he ruled. He led campaigns along the Euphrates and into Lebanon and Phoenicia. Any revolts were harshly put down, preventing further revolts. In contrast to this violence, the artwork that Ashurnasipal left behind is rich and varied, including many reliefs and bronze bands that held up gates. He also created a zoo within his new capital as well as botanical gardens.

source: https://www.academia.edu/30872972/Merciful_messages_in_the_reliefs_of_Ashurnasirpal_II_the_land_of_Su%E1%B8%ABu

It was at the inauguration of his new palace that Ashurnasipal held a huge 10-day banquet in about 679 BCE. He inscribed on the walls of his palace about this feast. Invitations went out to the entire country, of whom 69,574 accepted. Among these were 16,000 citizens of the new capital and 5,000 dignitaries. To feed the guests required a lot of food, which included:

'1,000 oxen

1,000 domestic cattle and sheep

14,000 imported and fattened sheep

1,000 lambs

500 game birds

500 gazelles

10,000 fish

10,000 eggs

10,000 loaves of bread

10,000 measures of beer

10,000 containers of wine'

in addition to the spices and side dishes to go with these foods.

source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1849-0502-1

Exactly why Ashurnasipal decided to host such a gathering was not recorded or has not been found. What has been found is something called the Standard Inscription because it was posted many times through the palace, which traces Ashurnasipal's ancestors three generations as well as his military victories and the boundaries of his empire. It then recounts the founding of Kalhu (modern-day Nimrud). The text of the Standard Inscription begins

'Palace of Assurnasirpal, vice-regent of Aššur [national god of Assyria], chosen one of the gods Enlil and Ninurta beloved of the gods Anu and Dagan destructive weapon of the great gods, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta, great king, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Adad-Nirari great king, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria; valiant man who acts with the support of Aššur, his lord, and has no rival among the princes of the four quarters, marvelous shepherd, fearless in battle, unopposable mighty floodtide, king who subdues those insubordinate to him, he who rules all peoples, strong male who treads upon the necks of his foes, trampler of all enemies, he who smashes the forces of the rebellious, king who acts with the support of the great gods, his lords, and has conquered all lands, gained dominion over all the highlands and received their tribute, capturer of hostages, he who is victorious over all countries…'

and then describes his campaigns then the rebuilding of Kalhu. Exactly what the dignitaries thought of the party or of Kahlu hasn't been found, though the use of the title 'king of the universe' was contested by the kings of other nations.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The coronation of the king of Assyria by the gods

The Assyrian king receives the insignia of power from the gods Aššur (Ashur) and Ištar (Ishtar).

Ashur is in front of the Assyrian king and Ishtar is behind him and puts the king's hat on the king's head.

Read More:

What does ashurbanipal name mean (Text Post)

How does Ashurbanipal introduce himself (Text Post)

#archaeology#ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamia#ancient history#akkadian#ancient iraq#ancient assyria#assyrian#ancient empire#ancient assyrian king#history of mesopotamian kings#history of ancient assyrfia#god of ashur#god of ishtar#gods of mesopotamia

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AN ASSYRIAN INSCRIBED GYPSUM FRAGMENT REIGN OF ASHURNASIRPAL II, CIRCA 883-859 B.C.

7 3/4 in. (19.6 cm.) high.

Known as the "Slab Back Text" this cuneiform fragment preserves a section from the back of a larger relief once reading (the preserved portions highlighted): "Ashurnasirpal, great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta (II), great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria, son of Adad-narari (II) (who was) also great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria; valiant man who acts with the support of Aššur, his lord, and has no rival among the princes of the four quarters, marvelous shepherd, fearless in battle, mighty flood-tide which has no opponent, the king who subdued (the territory stretching) from the opposite bank of the Tigris to Mount Lebanon and the Great Sea, the entire land Laqû, (and) the land Su?u including the city Rapiqu. He conquered from the source of the River Subnat to the interior of the land Nirbu..."

As J.M. Russell informs (pp. 19-23 in The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions), the “Slab Back Text” was carved on the backs of every wall relief panel of Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace. These were among the first inscriptions discovered by Sir Austen Henry Layard in the mid-19th century during his excavations of the palace. Given the thickness and weight of these relief panels, most of the examples now in European and North American collections had their backs removed by local stonecutters in order to facilitate their transport abroad. In the process, many of the Slab Back Texts were discarded.

#AN ASSYRIAN INSCRIBED GYPSUM FRAGMENT#REIGN OF ASHURNASIRPAL II CIRCA 883-859 B.C.#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#assyrian history

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the oldest goddesses in the historical record is Inanna of Mesopotamia, who was referred to, among other honorifics, as “She who makes a woman into a man, she who makes a man into a woman.” The power to alter such fundamental categories was evidence of her divine power. Inanna was served by at least half a dozen different types of transgendered priests, and one of her festivals apparently included a public celebration in which men and women exchanged garments. The memory of a liminal third-gender status has been lost, not only in countries dominated by Christian ideology, but also in many circles dedicated to the modern revival of goddess worship. Images of the divine feminine tend to appear alone, in Dianic rites, surrounded only by other women, or the goddess is represented with a male consort, often one with horns and an erect phallus. But it is equally valid to see her as a fag hag and a tranny chaser, attended by men who have sex with other men and people who are, in modern terms, transgendered or intersexed.

— Speaking Sex to Power: The Politics of Queer Sex by Patrick Califia

#m.#ishtar#aššurism#inanna#trans spirituality#galli#trans history#paganism#trans devotees#purposefully trans#trans is divine

813 notes

·

View notes

Text

And just for fun, the Bronze Age equivalent of “do it for her.”

#my workspace#props if you can recognize all the archeological sites and various reconstructions#still love trading colony era Kaneš#wrote a few stories set in that time period#awkward Aššur trying to trade with the Hattic gods#he is just terrible at socialization

1 note

·

View note

Text

The group of ten men who profited from the sale of Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter in the city of Aššur were entirely ordinary. That group included a baker, a weaver, a cook, a shepherd, an ironsmith, and a goldsmith, some of whom worked for a local temple. The most likely explanation for how they came into the possession of Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter is that these ten men formed a kisru, or “knot,” the standard unit in which Assyrians performed their required services to the king. These ten ordinary men were thus part-time soldiers, called up for the campaign to Elam, and Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter were their payment for their service on that campaign. When they got back to Aššur, the ten-man kisru couldn’t easily divide up two captives, so they sold her and split the profits: about 50 grams of silver per man, which they then took back to their homes, families, and occupations as iron- and goldsmiths, bakers, and cooks. The two Elamite women were enslaved, and the ten Assyrian men benefited directly from their participation in that campaign.

Did the weaver and cook talk about it, we might wonder? Did they tell their wives and children about what they had seen during the vicious sack of the Elamite capital of Susa, the fire and the ransacked royal tombs and desecrated temples that the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal bragged about in his account of these events, the wanton killing and sexual assault, the enslaved who died on the march back to Aššur? Were they proud of what they’d done, did they feel shame, or did they even think about those events? Did they seem like the actions of other people in other lives, unconnected to the workaday existence of an ironmonger and a baker going about their lives in the spiritual home of the Assyrian Empire?

We simply don’t know the answers to those questions, and we never will. The source material that would allow us to formulate an answer doesn’t exist.

Patrick Wyman, Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future Substack, 2024

#the podcast ep talking about these two people was a particularly memorable one#tides of history#patrick wyman#history

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

÷

·

𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾 ANUNNAKI ·

·

šakkanakki Bābili · King of Babylon ·

·

· ·

Sumu-abum

Sumu-la-El Sabium

Apil-Sin

Sin-Muballit Hammurabi

Samsu-iluna

Abi-Eshuh Ammi-Ditana

Ammi-Saduqa Samsu-Ditana

Dynasty I · Amorite · 1894–1595 BC

. .

.

Ilum-ma-ili Itti-ili-nibi

Damqi-ilishu

Ishkibal Shushushi

Gulkishar

DIŠ-U-EN Peshgaldaramesh

Ayadaragalama

Akurduana Melamkurkurra

Ea-gamil

Dynasty II · 1st Sealand · 1725–1475 BC

·

· ·

· ·

Gandash

Agum I Kashtiliash I

Abi-Rattash Kashtiliash II

Urzigurumash

Agum II Harba-Shipak

Shipta'ulzi

Burnaburiash I Ulamburiash

Kashtiliash III

Agum III

Kadashman-Sah

Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I

Kurigalzu I

Kadashman-Enlil I Burnaburiash II

Kara-hardash

Nazi-Bugash Kurigalzu II

Nazi-Maruttash

Kadashman-Turgu Kadashman-Enlil II

Kudur-Enlil

Shagarakti-Shuriash Kashtiliash IV

Enlil-nadin-shumi

Kadashman-Harbe II Adad-shuma-iddina

Adad-shuma-usur

Meli-Shipak

Marduk-apla-iddina I

Zababa-shuma-iddin

Enlil-nadin-ahi

Dynasty III · Kassite · 1729–1155 BC

. .

.

·

· ·

Marduk-kabit-ahheshu

Itti-Marduk-balatu Ninurta-nadin-shumi

Nebuchadnezzar I

Enlil-nadin-apli Marduk-nadin-ahhe

Marduk-shapik-zeri Adad-apla-iddina

Marduk-ahhe-eriba Marduk-zer-X

Nabu-shum-libur

Dynasty IV · 2nd Isin · 1153–1022 BC

· ·

· ·

·

Simbar-shipak

Ea-mukin-zeri Kashshu-nadin-ahi

.

Dynasty V · 2nd Sealand · 1021–1001 BC

· ·

· ·

Eulmash-shakin-shumi Ninurta-kudurri-usur I

Shirikti-shuqamuna

Dynasty VI · Bazi · 1000–981 BC

·

· ·

·

Mar-biti-apla-usur

Dynasty VII · Elamite · 980–975 BC

·

· ·

·

· ·

Nabu-mukin-apli Ninurta-kudurri-usur II

Mar-biti-ahhe-iddina Shamash-mudammiq

Nabu-shuma-ukin I Nabu-apla-iddina

Marduk-zakir-shumi I Marduk-balassu-iqbi

Baba-aha-iddina

.

.

.

at least 4 years

Babylonian interregnum

Ninurta-apla-X Marduk-bel-zeri

Marduk-apla-usur Eriba-Marduk

Nabu-shuma-ishkun Nabonassar

Nabu-nadin-zeri Nabu-shuma-ukin II

Dynasty VIII · E · 974–732 BC

· ·

·

·

·

Nabu-mukin-zeri Tiglath-Pileser III

Shalmaneser V Marduk-apla-iddina II

Sargon II Sennacherib

Marduk-zakir-shumi II Marduk-apla-iddina II

Bel-ibni Aššur-nādin-šumi

Nergal-ushezib Mushezib-Marduk

Sennacherib aka Sîn-ahhe-erība

Esarhaddon aka Aššur-aḫa-iddina

Ashurbanipal

Šamaš-šuma-ukin

Aššur-bāni-apli Sîn-šumu-līšir

Sîn-šar-iškun

Dynasty IX · Assyrian · 732–626 BC

. .

.

.

Nabopolassar

Nabû-apla-uṣur

Nebuchadnezzar II Nabû-kudurri-uṣur

Amēl-Marduk

Neriglissar

Nergal-šar-uṣur

Lâbâši-Marduk

Nabonidus

Nabû-naʾid

Dynasty X · Chaldean · 626–539 BC

. ·

. ��

. ·

. ·

. ·

. ·

Cyrus II the Great · Kuraš · 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 Kūruš ·

Cambyses II · Kambuzīa ·

Bardiya · Barzia ·

Nebuchadnezzar III · Nabû-kudurri-uṣur ·

·

Darius I the Great · Dariamuš · 1st reign

·

Nebuchadnezzar IV · Nabû-kudurri-uṣur

Darius I the Great · Dariamuš · 2nd reign

·

Xerxes I the Great · Aḫšiaršu · 1st reign

·

Shamash-eriba · Šamaš-eriba

Bel-shimanni · Bêl-šimânni

·

Xerxes I the Great · Aḫšiaršu · 2nd reign

·

Artaxerxes I · Artakšatsu

Xerxes II

Sogdianus

Darius II

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes III

Artaxerxes IV

Nidin-Bel

Darius III

Babylon under foreign rule · 539 BC – AD 224

Dynasty XI · Achaemenid · 539–331 BC

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·.

Alexander III the Great · Aliksandar

Philip III Arrhidaeus · Pilipsu

Antigonus I Monophthalmus · Antigunusu

Alexander IV · Aliksandar

Dynasty XII · Argead · 331–305 BC

·.

·.

·.

·.

·.

Seleucus I Nicator · Siluku

Antiochus I Soter · Antiʾukusu

Seleucus · Siluku

Antiochus II Theos · Antiʾukusu

Seleucus II Callinicus · Siluku

Seleucus III Ceraunus ·

Antiochus III the Great · Antiʾukusu

Antiochus ·

Seleucus IV Philopator · Siluku

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ·

Antiochus

Antiochus V Eupator

Demetrius I Soter

Timarchus

Demetrius I Soter

Alexander Balas

Demetrius II Nicator

Dynasty XIII · Seleucid · 305–141 BC

· ·.

. · ·

. · ·

. · ·

· ·.

· ·.

Mithridates I

Phraates II

Rinnu

Antiochus VII Sidetes

Phraates II

Ubulna

Hyspaosines

Artabanus I

Mithridates II

Gotarzes I

Asi'abatar

Orodes I

Ispubarza

Sinatruces

Phraates III

Piriustana

Teleuniqe

Orodes II

Phraates IV

Phraates V

Orodes III

Vonones I

Artabanus II

Vardanes I

Gotarzes II

Vonones II

Vologases I

Pacorus II

Artabanus III

Osroes I

Vologases III

Parthamaspates

Vologases IV

Vologases V

Vologases VI

Artabanus IV

Dynasty XIV · Arsacid · 141 BC – AD 224

· 9 centuries of Persian Empires · until AD 650

Trajan in AD 116

mid-7th-century Muslim Empire

·.

·.

·.

1921 Iraqi State

·.

·.

1978 · 14th of February · Saddam Hussein

·.

·.

2009 · May · the provincial government of Babil

·.

·.

·.

·.

. ·

·.

·.

·.

·.

so many kings

and just one queen

semiramis

·· ·

· SEMIRAMIS ·

··

.

.

.

.

···· Βαβυλών ··· ΒΑΒΥΛΩΝ ····

Babylonia

Gate of the Gods

بابل Babil 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 · 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 · 𐡁𐡁𐡋 · ܒܒܠ · בָּבֶל

Iraq · 55 miles south of Baghdad

near the lower Euphrates river

.

.

.

.

.

#king#of#babylon#semiramis#assur#uruk#mar-biti-apla-usur#marduk-apla-usur#mesopotamia#annunaki#anunnaki

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Educational-Intellectual De-Westernization for Africa: Rejection of the Colonial, Elitist, Racist and Profane European Concepts of 'University' and 'Academy'

In a previous article published under the title "Beyond Afrocentrism: Prerequisites for Somalia to lead African de-colonization and de-Westernization", I expanded on the diverse misconceptions, oversights, errors and problems that existed in the early discourses of the African Afrocentric intellectuals who wanted to liberate Africa from the colonial yoke but did not assess correctly all the levels of colonial penetration and impact, namely spiritual, religious, intellectual, educational, academic, scientific, cultural, socio-behavioral, economic, military and governmental. You can find the article's contents and links to it at the end of the present, second part of the series.

What matters mostly is not the study and the publication of Assyrian cuneiform texts, but the reestablishment of the Ancient Mesopotamian conceptual approach to Medicine as a spiritual-material scientific discipline; "a large collection of texts from the Assyrian healer Kisir-Ashur's family library forms the basis for Assyriologist Troels Pank Arbøll's new book. In the book entitled Medicine in Ancient Assur - A Microhistorical Study of the Neo-Assyrian Healer Kiṣir-Aššur, Arbøll analyses the 73 texts that the healer, and later his apprentices, scratched into clay tablets around 658 BCE. These manuscripts provide an incredibly detailed picture of the elements, which constituted this specific Mesopotamian healer’s education and practice". https://humanities.ku.dk/news/2020/new-book-provides-rare-insights-into-a-mesopotamian-medical-practitioners-education-2700-years-ago/

Contents

Introduction

I. Centers of education, science and wisdom from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Constantinople and Baghdad: total absence of the Western concept of "university"

II. The Western European concept of "university": inextricably linked to the Crusades, colonialism and totalitarianism

III. De-colonization for Africa: rejection of the colonial, elitist and racist concepts of "university" and "academy"

Introduction

As I stated in my previous article, the most erroneous aspects of the African Afrocentric intellectuals' approach were the following:

a) their underestimation of the extremely profound impact that the colonization has had on all dimensions of life in Africa,

b) their failure to identify the compact nature of the colonial system as first implemented in Western Europe, then exported worldwide via multifaceted types of colonization, and finally imposed locally by the criminal traitors and stooges of their Western masters in a most tyrannical manner, and

c) their disregard of the fact that the multilayered colonization project was carried out indeed by the colonial countries in other continents (Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, etc.) as well, being thus not only an African affair.

To the above, I herewith add another, most crucial, element of the worldwide colonial regime that the African Afrocentric intellectuals failed to identify:

- its indivisibility.

In fact, you cannot possibly think that it is possible to reject even one part of the evil system (example: its Eurocentric pseudo-historical dogma, the promotion of incest and pedophilia, the sophisticated diffusion of homosexuality or another part) while accepting others, namely 'high technology', 'sustainable development', 'politics', 'democracy', 'economic stability', 'human rights', etc. Of course, this relates to the element described in the aforementioned aspect b, but it is certainly very important for all Africans not to make general dreams and not to harbor delusions as regards the Western colonial system that they have to reject as the most execrable and the most criminal occurrence that brought disaster to the Black Continent (and to the rest of the world) for several centuries.

In the present article, I will however stay close to the fundamental educational-academic-intellectual aspects of colonization that African academics, intellectuals, mystics, wise elders, erudite scholars, and spiritual masters have to take into account when considering how to reject and ban from their educational and research centers the colonially imposed pseudo-education and the associated historical forgeries, such as Eurocentrism, Hellenism, Greco-Roman world, Judeo-Christian civilization, etc. In part IV of my previous article, I explained why "Afrocentrism had to encompass severe criticism and total rejection of the so-called Western Civilization". Now, I will take this issue to the next stage.

I. Centers of education, science and wisdom from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Constantinople and Baghdad: total absence of the Western concept of "university"

You cannot possibly decolonize your land and de-Westernize your national education by tolerating the existence of 'universities' on African soil or anywhere else across the Earth. Certainly, this word is alien to all Africans, because it is part of the vocabulary or the barbarian invaders (université, university, etc.), who imposed it without revealing to the African students the racist connotation, which is inherent to this word.

Actually, the central measure taken and the principal practice performed by the inhuman Western colonial masters was the materialization of the evil concept of 'university' and the establishment of such unnecessary and heinous institutions in their colonies. This totalitarian notion was devised first in Western Europe in striking contrast to all the educational, academic, scientific systems that had existed in the rest of the world.

Since times immemorial, and noticeably in Mesopotamia and Egypt before the Flood (24th – 23rd c. BCE), institutions were created to record, archive, study, comprehend, represent, preserve and propagate the spiritual or material knowledge and wisdom in all of their aspects. From the Sumerian, Akkadian and Assyrian-Babylonian Eduba (lit. 'the house where the tablets are completed') and from the Ancient Egyptian Per-Ankh (lit. 'the house of life') to the highest sacerdotal institutions accommodated in the uniquely vast temples of Assyria, Babylonia and Egypt, an undividable method of learning, exploring, assessing, and representing the spiritual and material worlds (or universes) has been attested in numerous texts and documented in the archaeological record.

About Education, Wisdom, and Scientific Research in Ancient Mesopotamia:

About Education, Wisdom, and Scientific Research in Ancient Egypt:

There was no utilitarian approach to learning, studying, exploring, comprehending, representing and propagating knowledge and wisdom; in this regard, the human effort had to fit the destination of Mankind, which was -for all civilized nations- the epitome of all eschatological expectations: the ultimate reconstitution of the original perfection of the First Man.

Learning, studying, exploring, assessing or concluding on a topic, and representing it to others were parts of every man's moral tasks and duties to maintain the Good in their lives and to unveil the Wonders of the Creation. The only benefit to be extracted from these activities was of moral and spiritual order – not material. That is why the endless effort to learn, study, explore, assess, conclude and represent had to be all-encompassing.

The same approach, attitude and mentality was attested among Cushites, Hittites, Aramaeans, Iranians, Turanians, Indians, Chinese and many other Asiatic and African nations. It continued so all the way down to Judean, Manichaean, Mazdaean, Christian, and Islamic times as attested in

a) the Iranian schools, centers of learning, research centers, and libraries of Gundishapur (located in today's Khuzestan, SW Iran), Tesifun (Ctesiphon, also known as Mahoze in Syriac Aramaic and as Al-Mada'in in Arabic; located in Central Mesopotamia), and Ras al Ayn (the ancient Assyrian city Resh-ina, which is also known as Resh Aina in Syriac Aramaic; located in North Mesopotamia);

b) the Aramaean scientific centers and schools of Urhoy (today's Urfa in SE Turkey; which is also known as Edessa of Osrhoene), Nasibina (today's Nusaybin in SE Turkey; which is also known as Nisibis), Mahoze (also known as Seleucia-Ctesiphon), and Antioch;

c) the Ptolemaic Egyptian Library of Alexandria, the Coptic school of Alexandria, and the Deir Aba Maqar (Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great) in Wadi el Natrun (west of the Nile Delta);

d) the Imperial school of the Magnaura (lit. 'the Great Hall') at Constantinople (known in Eastern Roman as Πανδιδακτήριον τῆς Μαγναύρας, i.e. 'the all topics teaching center of Magnaura');

e) the Aramaean 'Workshop of Eloquence', which is also known as the 'Rhetorical school of Gaza' (earlier representing the Gentile tradition and later promoting Christian Monophysitism);

f) the Judean Rabbinic and Talmudic schools and Houses of Learning (בי מדרשא/Be Midrash) that flourished in Syria-Palestine (Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai) and in Mesopotamia (Nehardea, Pumbedita, Mahoze, etc.); and

g) the Islamic schools (madrasas), centers of learning, research centers, observatories, and libraries of Baghdad (known as House of Wisdom - Bayt al Hikmah/بيت الحكمة), Harran (in North Mesopotamia, today's SE Turkey), al-Qarawiyyin (جامعة القرويين; in Morocco), Kairouan (جامع القيروان الأكبر; in Tunisia), Sarouyeh (سارویه; near Isfahan in Iran), Maragheh (مراغه; in NW Iran), Samarqand (in Central Asia), and the numerous Nezamiyeh (النظامیة) schools in Iran, Caucasus region, and Central Asia, to name but a few.

About Iranian, Aramaean, Judean, and Christian schools, centers of learning, research centers, and libraries:

About Islamic schools (madrasas), centers of learning, research centers, observatories, and libraries:

All these centers of learning did not develop the absurd distinction between the spiritual and material worlds that characterizes the modern 'universities' which were incepted in Western Europe. Irrespective of land, origin, language, tradition, culture and state, all these temples, schools, madrasas, observatories, and libraries included well-diversified scientific methods, cosmogonies, world perceptions, approaches to life, interpretations of facts, and considerations of data. Sexagesimal and decimal number systems were accepted and used; lunar, solar and lunisolar calendars were studied and evaluated; astronomy and astrology (very different from their modern definition and meaning which is the result of the Western pseudo-scientific trickery) were inseparable, whereas chemistry and alchemy constituted one discipline. These true and human centers of knowledge and wisdom were void of sectarianism and utilitarianism.

Viewed as moral tasks, search, exploration and study, pretty much like learning and teaching constituted inextricably religious endeavors. Furthermore, there was absolute freedom of reflection, topic conceptualization, data contextualization, text interpretation, and conclusion, because there were no diktats of theological or governmental order.

In brief, throughout World History, there were centers of learning, houses of knowledge, libraries, centers of scientific exploration, all-inclusive schools, but no 'universities'.

II. The Western European concept of "university": inextricably linked to the Crusades, colonialism and totalitarianism

Western European and North American historians attempt to expand the use of the term 'university' and cover earlier periods; this fact may have already been attested in some of the links that I included in the previous unit. However, this attempt is entirely false and absolutely propagandistic.

The malefic character of the Western European universities is not revealed only in the deliberate, absurd and fallacious separation of the spiritual sciences from the material sciences and in the subsequently enforced elimination of the spiritual universe from every attempt of exploration undertaken within the material universe. Yet, the inseparability of the two universes was the predominant concept and the guiding principle for all ancient, Judean, Christian, Manichaean, Mazdaean, and Islamic schools of learning.

One has to admit that there appears to be an exception in this rule, which applies to Western universities as regards the distinction between the spiritual and the material research; this situation is attested only in the study of Christian theology in Western European universities. However, this sector is also deprived of every dimension of spiritual exercise, practice and research, as it involves a purely rationalist and nominalist approach, which would be denounced as entirely absurd, devious and heretic by all the Fathers of the Christian Church. As a matter of fact, rationalism, nominalism and materialism are forms of faithlessness.

All the same, the most repugnant trait of the Western European universities is their totalitarian and inhuman nature. In spite of tons of literature written about the so-called 'academic freedom', the word itself, its composition and etymology, fully demonstrate that there is not and there cannot be any freedom in the Western centers of pseudo-learning, which are called 'universities'. The Latin word 'universitas' did not exist at the times of the Roman Republic, the Roman Empire, and the Western Roman Empire. The nonsensical term was not created in the Eastern Roman Empire where the imperial center of education, learning, and scientific research was wisely named 'Pandidakterion', i.e. 'the all topics teaching center'.

The first 'universitas' was incepted long after the anti-Constantinopolitan heretics of Rome managed to get rid of the obligation to accept as pope of Rome the person designated by the Emperor at Constantinople, which was a practice of vital importance which lasted from 537 until 752 CE.

The first 'universitas' was incepted long after the beginning of the systematic opposition that the devious, pseudo-Christian priesthood of Rome launched against the Eastern Roman Empire, by fallaciously attributing the title of Roman Emperor to the incestuous barbarian thug Charlemagne (800 CE).

Last, the first 'universitas' was incepted long after the first (Photian) schism (867 CE) and, quite interestingly, several decades after the Great Schism (1054 CE) between the Eastern Roman Empire and the deviate and evil Roman papacy.

In fact, the University of Bologna ('Universitas Bononiensis'; in Central Italy) was established in 1088 CE, only eight (8) years before the First Crusade was launched in 1096 CE.

It is necessary for all Africans to come to know the historic motto of the terrorist organization that is masqueraded behind the deceitful title "University of Bologna': "Petrus ubique pater legum Bononia mater" (: St. Peter is everywhere the father of the law, Bologna is its mother). This makes clear that these evil institutions (universities) were geared to function worldwide as centers of propagation and imposition of the lawless laws and the inhuman dogmas of the Western European barbarians.

At this point, we have to analyze the real meaning and the repugnant nature of the monstrous word. Its Latin etymology points to the noun 'universus', which is formed from 'uni-' (root of the Genitive 'unius' of the numeral 'unus', which means 'one') and from 'versus' (past participle of the Latin verb 'verto', which in the infinitive form 'vertere' means 'to turn'). Consequently, 'universus' means forcibly 'turned into one'. It goes without saying that, if the intention is to mentally-intellectually turn all the students into one, there is not and there cannot be any freedom in those malefic institutions.

'Universitas' is therefore the inauspicious location whereby 'all are turned into one', inevitably losing their identity, integrity, originality, singularity and individuality. In other words, 'universitas' was conceived as the proper word for a monstrous factory of mental, intellectual, sentimental and educational uniformity that produces copies of dehumanized beings that happen to have the same, prefabricated world views, ideas, opinions, beliefs and systematized 'knowledge'. In fact, the first 'students' of the University of Bologna were the primary industrial products in the history of mankind. Speaking about 'academic freedom' and charters like the Constitutio Habita were then merely the ramifications of an unmatched hypocrisy.

To establish a useful parallel between medieval times in Western Europe and modern times in North America, while also bridging the malefic education with the malignant governance of the Western states, I would simply point out that the evil, perverse and tyrannical institution of 'universities' definitely suits best any state and any government that would dare invent an inhumane motto like 'E pluribus unum' ('out of many, one). This is actually one of the two main mottos of the United States, and it appears on the US Great Seal. It reflects always the same sickness and the same madness of diabolical uniformity that straightforwardly contradicts every concept of Creation.

One may still wonder why, at the very beginning of the previous unit, I referred to "the racist connotation, which is inherent to" the word 'universitas'; the answer is simple. By explicitly desiring to "turn all (the students) into one", the creators of these calamitous institutions and, subsequently, all the brainless idiots, who willingly accepted to eliminate themselves spiritually and intellectually in order to become uniformed members of those 'universities', denied and rejected the existence of the 'Other', i.e. of every other culture, civilization, world conceptualization, moral system of values, governance, education, and approach to learning, knowledge and wisdom.

The evil Western structures of tyrannical pseudo-learning did not accept even the 11th c. Western European Christians and their culture an faith; they accepted only those among them, who were ready (for the material benefits that they would get instead) to undergo the necessary process of irrevocable self-effacement in order to obtain a filthy piece of paper testifying to their uniformity with the rest. Western universities are the epitome of the most inhuman form of racism that has ever existed on Earth.

As a matter of fact, there is nothing African, Asiatic, Christian, Islamic or human in a 'university'. If this statement was difficult to comprehend a few centuries or decades ago, it is nowadays fully understandable.

III. De-colonization for Africa: rejection of the colonial, elitist and racist concepts of "university" and "academy"

It is therefore crystal clear that every new university, named after the Latin example and conceived after the Western concept, only worsens the conditions of colonial servility among African, Asiatic and Latin American nations. As a matter of fact, more Western-styled 'universities' and 'academies' mean for Africa more compact subordination to, and more comprehensive dependence on, the Western colonial criminals.

It is only the result of pure naivety or compact ignorance to imagine that the severe educational-academic-intellectual damage, which was caused to all African nations by the colonial powers, will or can be remedied with some changes of names, titles, mottos and headlines or due to peremptory modifications of scientific conclusions. If I expanded on the etymology and the hidden, real meaning of the term 'universitas', it is only because I wanted to reveal its perverse nature. But merely a name change would not suffice in an African nation's effort to achieve genuine decolonization and comprehensive de-Westernization.

Universities in all the Arabic-speaking countries have been called 'Jamaet' (or Gamaet; جامعة); the noun originates from the verb 'yajmaC ' (يجمع), which means collecting or gathering (people) together. At this point, it is to be reminded that the word has great affinity with the word 'mosque' (جامع; JamaC) in Arabic. However, one has to take into consideration the fact that the mere change of name did not cause any substantive differentiation in terms of nature, structure, approach to science, methods used, and moral character of the overall educational system.

Other vicious Western terms of educational nature that should be removed from Africa, Asia and Latin America are the word 'academy' and its derivatives; this word denoted initially in Western Europe 'a society of distinguished scholars and artists or scientists'. Later, in the 16th-17th c., those societies were entirely institutionalized. For this reason, since the beginning of the 20th c., the term 'academia' was coined to describe the overall academic environment or a specific independent community active in the different fields of research and education. More recently, 'academy' ended up signifying any simple place of study or training company.

As name, nature, contents, structure and function, 'academy' is definitely profane; in its origin, it had a markedly impious character, as it was used to designate the so-called 'school of philosophy' that was set up by Plato, who vulgarized knowledge and desecrated wisdom. In fact, this philosopher did not only fail to pertinently and comprehensively study in Ancient Egypt where he sojourned (in Iwnw; Heliopolis), but he also proved to be unable to grasp that there is no knowledge and no wisdom outside the temples, which were at the time the de facto high centers of spiritual and material study, learning, research, exploration and comprehension. He therefore thought it possible for him to 'teach' (or discuss with) others despite the fact that he had not proficiently studied and adequately learned the wisdom and the spiritual potency of the Ancient Egyptian Iwnw (Heliopolitan) hierophants and high priests.

Being absolutely incompetent to become a priest of the sanctuary of Athena at the suburb 'Academia' of Athens, he gathered his group of students at a location nearby, and for this reason his 'school' was named after that neighborhood. It is noteworthy that the said suburb's name was due to a legendary figure, Akademos (Ακάδημος; Academus), who was mythologized in relation with the Theseus legends of Ancient Athens. Using the term 'school' for Plato's group of friends and followers is really abusive, because it did not constitute an accredited priestly or public establishment.

In fact, all those, absurdly eulogized, 'Platonic seminars' were informal gatherings of presumptuous, arrogant, wealthy, parasitic and idiotic persons, who thought it possible to become spiritually knowledgeable and portentous by pompously, yet nonsensically, discussing about what they could not possibly know. It goes without saying that this disgusting congregation of immoral beasts found it quite normal to possess numerous slaves (more than their family members), consciously practiced pedophilia and homosexuality, and viewed their wives as 'things' in a deprecatory manner unmatched even by the Afghan Taliban. This nauseating and execrable environment is at the origin of vicious term 'academy'. And this environment is the target of today's Western elites.

Consequently, any use of the term 'academy' constitutes a straightforward rejection of the sacerdotal, religious and spiritual dimension of knowledge and wisdom, in direct opposition to what was worldwide accepted among civilized nations with great temples throughout the history of mankind. In fact, the appearance of what is now called 'Ancient Greek Philosophy' was an exception in World History, which was due to the peripheral and marginal location of Western Anatolia and South Balkans with respect to Egypt, Cush, Syria-Palestine, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Iran. In brief, the Ancient Greek philosophers (with the exception of very few who were true mystics and spiritual masters and therefore should not be categorized as 'philosophers') failed to understand that, by exploring the world only mentally and verbally (i.e. by just thinking and talking), no one can sense, describe, and represent (to others) the true nature of the worlds, namely the spiritual and the material universes.

Plato and his pupils (his 'school' or 'academy') were therefore ordinary individuals who attempted to 'prove' orally what cannot be contained in words and cannot be comprehended logically but contemplatively and transcendentally. All the Platonic concepts, notions, ideas, opinions and theories are maladroit and failed efforts to explain the Iwnw (Heliopolitan) religion of Ancient Egypt (also known among the Ancient Greeks as the 'Ennead'). But none of them was able to perform even a minor move of priestly potency or any transcendental act.

Furthermore, I have to point out that the absurd 'significance' that both, the so-called Plato's school and 'Ancient Greek Philosophy', have acquired in the West over the past few centuries is entirely due to the historical phenomenon of Renaissance that characterized 15th-16th c. Western Europe. But this is an exception even within the context of European History. Actually, the Roman ruler Sulla destroyed the Platonic Academy in 86 BCE; this was the end of the 'Academy'. Several centuries later, some intellectuals, who were indulging themselves in repetition, while calling themselves 'successors of Plato', opened (in Athens) another 'Academy', which was erroneously described by modern Western university professors as 'Neo-Platonic'. All the same, the Roman Emperor Justinian I the Great put an irrevocable end to that shame of profanity and nonsensical talking (529 CE).

The revival of the worthless institution that had remained unknown to all Christians started, quite noticeably, little time after the fall of Constantinople (1453); in 1462, the anti-Christian banker, statesman and intellectual Cosimo dei Medici established the Platonic Academy of Florence to propagate all the devilish and racist concepts of the Renaissance and praise the worthless institution that had been forgotten.

I recently explained why the Western European Renaissance and the colonial conquests are an indissoluble phenomenon of extremely racist nature; here you can find the links to my articles:

It becomes therefore crystal clear that Africa does not need any more Western-styled universities and academies; contrarily, there is an urgent need for university-level centers of knowledge and wisdom, which will overwhelmingly apply African moral concepts, values and virtues to the topics studied and explored. Learning was always an inextricably spiritual, religious, and cultural affair in Africa. No de-colonization will be effectuated prior to the reinstallation of African educational values across Africa' s schools.

Consequently, instead of uselessly spending money for the establishment of new 'universities' and 'academies', which only deepen and worsen Africa's colonization, what the Black Continent needs now is a new type of institution that will help prepare African students to study abroad in specifically selected sectors and with pre-arranged determination and approach, comprehend and reject the Western fallacy, and replace the Western-styled universities with new, genuinely African, educational institutions. Concerning this topic, I will offer few suggestions in my forthcoming article.

=======================

Beyond Afrocentrism: Prerequisites for Somalia to lead African de-colonization and de-Westernization

Introduction

I. Decolonization and the failure of the Afrocentric Intelligentsia

II. Afrocentric African scholars should have been taken Egyptology back from the Western Orientalists and Africanists

III. Western Usurpation of African Heritage must be canceled.

IV. Afrocentrism had to encompass severe criticism and total rejection of the so-called Western Civilization

V. Afrocentrism as a form of African Isolationism drawing a line of separation between colonized nations in Africa and Asia

VI. General estimation of the human resources, the time, and the cost needed

VII. Decolonization means above all De-Anglicization and De-Francization

================

Download the article in PDF:

#EDUCATION#university#universitas#academy#Platonic academy#Western world#Western Europe#colonization#racism#elitism#decolonization#de-Westernization#Judeo-Christian#Greco-Roman#Hellenism#white supremism

0 notes